Abstract

Background:

The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet lowered blood pressure (BP) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Objective:

To compare effects of diets rich in fruits and vegetables with a typical American diet on cardiovascular injury in middle-aged adults without known preexisting cardiovascular disease.

Design:

Observational study based on a three-arm, parallel-design, randomized trial conducted in the U.S. from 1994 to 1996. (ClinicalTrials.gov:NCT00000544)

Setting:

Three of the four original clinical trial centers.

Participants:

326 of the original 459 trial participants with available stored specimens.

Interventions:

Participants were randomized to 8 weeks of monitored feeding with: a control diet typical of what many Americans eat, a diet rich in fruit and vegetables but otherwise similar to control, or the DASH diet which was rich in fruit, vegetables, low-fat dairy, and fiber, and reduced in saturated fat and cholesterol. Weight was kept constant throughout feeding.

Measurements:

Biomarkers collected at baseline and 8-weeks: high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I (hs-cTnI), N-terminal b-type pro natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP).

Results:

The mean age of participants was 45.2 years, 48% were women, 49% were black, and mean baseline BP was 131/85 mmHg. Compared to control, the fruits and vegetables diet reduced hs-cTnI by 0.5 ng/L (95% CI: −0.9 to −0.2) and NT-proBNP by 0.3 pg/mL (95% CI: −0.5 to −0.1). Compared to control, DASH reduced hs-cTnI by 0.5 ng/L (95% CI: −0.9 to −0.1) and NT-proBNP by 0.3 pg/mL (95% CI: −0.5 to −0.04). Hs-CRP did not differ between diets. None of the markers differed between the fruits and vegetables and DASH diets.

Limitations:

Short duration, missing specimens, inability to isolate effects of specific foods or micronutrients.

Conclusion:

Diets rich in fruits and vegetables given over an 8-week period were associated with lower markers of subclinical cardiac damage and strain in adults without preexisting cardiovascular disease.

Keywords: Diet, cardiovascular disease, blood pressure, cholesterol, troponin, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I, N-terminal b-type pro natriuretic peptide, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, trial

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in the United States (1). Observational studies show that a healthy diet is linked with reduced risk for CVD events, leading many to advocate for stronger public policy to promote healthy food choices (2). Critics, however, point to a dearth of evidence to support the hypothesis that adopting a healthy diet directly reduces CVD injury (3–5), and there are few feeding studies of healthy diet that address primary prevention of CVD (6).

The DASH trial was an 8-week, parallel arm, feeding study in adults with systolic blood pressures of less than 160 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressures of 80 to 95 mm Hg (7). Participants were fed either a typical American diet, a fruits and vegetables diet, or the DASH diet, rich in fruit, vegetables, low-fat dairy, and fiber and reduced in saturated fat and cholesterol. The DASH diet, which lowered BP and low density lipoprotein-cholesterol compared to a typical American diet, was considered by many as a bedrock of dietary guidelines for CVD risk prevention (8). However, whether the observed improvements in CVD risk factors impacted cardiac injury has not been reported.

In this study, we examine three biomarkers in stored specimens from a subpopulation of participants of the DASH trial to determine the effects of diet on subclinical (1) cardiac damage (high sensitivity troponin I, hs-cTnI), (2) cardiac strain (N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, NT-proBNP), and (3) inflammation (high sensitivity C-reactive protein, hs-CRP).

Methods

The DASH trial was conducted between September 1994 and March 1996 at four clinical centers within the United States (Baltimore, Maryland; Boston, Massachusetts; Durham, North Carolina; Baton Rouge, Louisiana). The study was sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. A detailed description and the primary results of the study have been published (7). In brief, DASH compared the effects of three different diets on systolic BP (SBP). The 459 trial participants were randomized within each site to: a control diet typical of what many Americans eat, a fruits and vegetables diet, or the DASH diet. At the time of the study, all participants provided written, informed consent for specimen storage. The present study used specimens curated by the NHLBI BioLINCC repository to measure the biomarkers described above. Institutional Review Boards at each institution approved the original study protocol. Only 3 of the original 4 sites contributed specimens for this analysis.

Participants

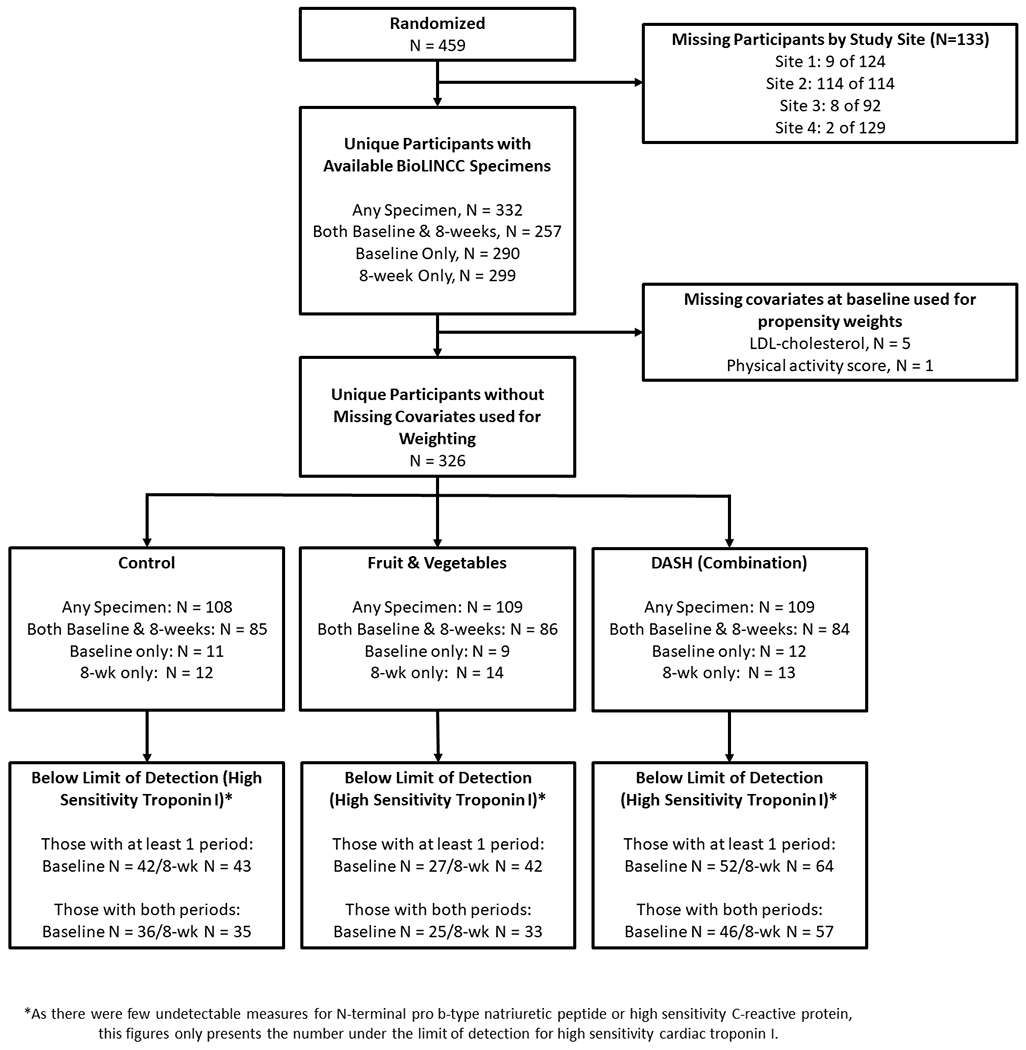

DASH participants were aged 22 years and older with average SBP between 120 to 159 mm Hg and average diastolic BP (DBP) between 80 to 95 mm Hg. Adults with diabetes mellitus, a cardiovascular event within the previous six months, a body-mass index >35 kg/m2, renal insufficiency, or a self-reported alcoholic beverage intake of more than 14 drinks per week were excluded as were those taking antihypertensive medications. Of the original 459 participants in the trial, 326 had stored specimens that were used for this analysis. Details regarding these participants, assignments, and specimen availability are in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram of Participants and Specimens

Dietary Interventions

Following a parallel design, each site randomized participants to one of three diets: a control diet, a fruits and vegetables diet, or the DASH diet (called “the combination diet” in the original publication; Supplement Table ST1). The control diet was designed to represent a typical American diet with potassium, magnesium, and calcium levels reflecting the 25th percentile of U.S. consumption, and macronutrient profiles and fiber reflecting the average U.S. consumption (7). The fruits and vegetables diet by contrast provided potassium and magnesium at the 75th percentile of U.S. consumption and provided higher amounts of fiber. This diet provided more fruits and vegetables with fewer snacks and sweets than the control diet, but in other ways was similar.

Like the fruits and vegetables diet, the DASH diet provided potassium and magnesium at levels reflecting the 75th percentile of U.S. consumption and was higher in fiber and protein (7). In addition, the DASH diet provided calcium at a level reflecting the 75th percentile of U.S. consumption, emphasized fat-free or low-fat dairy products, was reduced in saturated fat, total fat, cholesterol, sweets, and sugar-containing beverages, and included whole grains, poultry, fish, and nuts. All three diets were designed to provide a comparable amount of sodium (~3 g/day).

Isocaloric diets were administered as part of a seven-day menu cycle, which included 21 meals at four calorie levels (1600, 2100, 2600, and 3100 kcal). Each weekday, participants ate 1 principal meal (lunch or dinner) on site. The remaining meals (including weekend meals) were sent home in coolers to be consumed offsite. Feeding and participants’ weights were closely monitored. Participants recorded intake of beverages, salt, and non-study foods. Adherence was high, with participants attending over 95% of person-days at scheduled on-site meals and adhering to the study protocol offsite (all study foods and no non-study foods) over 93% of person-days.

Outcomes of Interest

Biomarker outcomes of interest for this analysis (hs-cTnI, NT-proBNP, and hs-CRP) were measured in 2019 from stored specimens. The biomarkers were selected based on their relationship with subclinical myocyte damage (hs-cTnI), cardiac strain (NT-proBNP), and inflammation (hs-CRP), which have been shown to predict CVD events in adults without known CVD (9–15). Serum specimens were collected in participants after a 12-hour fast at baseline prior to feeding (N=290) and at the conclusion of the 8-week feeding periods (N=299) for each of the three diets. All serum had been stored at −70°C and underwent at least 1 freeze-thaw cycle prior to the present measurements. All three markers were measured in all available specimens.

Assays and kits were donated by Siemens (Siemens Healthineers, Malvern, Pennsylvania) for the following markers: (1) ADVIA Centaur High-Sensitivity Troponin I (reported within-run CV of 4.8% for a mean of 13.11 ng/L [or pg/mL]), (2) Dimension Vista N-terminal Pro-brain Natriuretic Peptide (reported within-run CV of 1.4% for a mean of 120 pg/mL), and (3) Dimension Vista high sensitivity C-reactive protein (reported within-run CV of 5.2% for a mean of 2.39 mg/L). Lab inserts from the manufacturer with assay accuracy and precision performance are found in the Supplement. There were 332 participants with specimens at either baseline or the 8-week visit. Biomarker assays were restricted by the following limits of detection: <1.60 ng/L (hs-cTnI), <5 pg/mL (NT-proBNP), and <0.160 mg/L (hs-CRP). Given the larger number of hs-cTnI values below the limit of detection, we also examined an alternate measurement cut point based on the hs-cTnI assay’s the limit of blank (<0.5 ng/L) (Supplement Table ST2). The limit of detection is defined by the manufacturer as the lowest concentration of hs-cTnI that can be detected with 95% probability, while the limit of blank is defined as the highest measurement that might be observed for a blank sample. Note the following conversions for SI units: 1 ng/L high sensitivity cardiac troponin I equals 0.001 mg/L; 1 pg/mL of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide equals 1 ng/L and 0.1182 pmol/L; 1 mg/L high sensitivity C-reactive protein equals 9.5238 nmol/L.

Covariates

Other participant characteristics were determined via questionnaire, laboratory specimens, and physical examination. Race was examined in categories of black and non-black. Body mass index (BMI) was derived from measured height and weight; obesity was defined as a BMI ≥30 kg/m2. Seated SBP and DBP were measured with random-zero sphygmomanometers. BP at baseline was based on the average of three pairs of measurements during screening and four pairs during the run-in phase, while BP at follow-up was based on the average of four or five pairs of measurements during weeks 7 and 8 of the intervention phase. Hypertension was defined in DASH as SBP ≥140 mm Hg or DBP ≥90 mm Hg. Total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides were measured using enzymatic colorimetry and used to estimate low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c) (16). Number of alcoholic drinks per day were self-reported. Participants were also asked to quantify the time they spent on “moderate,” “hard,” or “very hard” tasks over the preceding 7-days to estimate their physical activity score (cal/kg/day).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were up-weighted (via the “pw” option) with inverse propensity score weights (18) to account for missing specimens and thus reflect the characteristics of the original randomized sample of the 3 sites included in this study (N=345). Propensity scores were determined via a logit function in which specimen variability was the dependent variable of the following participant characteristics (independent variables): age, female sex, black race, baseline systolic blood pressure, baseline diastolic blood pressure, baseline LDL-cholesterol, baseline body mass index, baseline hypertension status, baseline obesity, baseline alcohol use, and baseline physical activity score.

We described baseline population characteristics by diet assignment using weighted means (SD) and proportions. Individual change in biomarkers were examined via Spaghetti plots. The distribution of natural-log transformed cardiac biomarkers at baseline and 8-weeks, were examined using kernel density plots. Given data skew, we determined the geometric mean of serum concentrations (SD) of biomarkers at baseline and 8 weeks and used both the absolute difference (the difference in geometric means) and the percent change (derived by exponentiating the log-transformed difference) to compare change from baseline.

We compared log-transformed cardiac markers across dietary assignments, using the following contrasts: fruits and vegetables versus control, DASH versus control, and fruits and vegetables versus DASH. We report both the difference in exponentiated values (geometric means) to estimate change on the original marker scale as well as exponentiated differences to present %-difference between diets.

All comparisons (both baseline and between diets) were performed via mixed effects tobit regression models (metobit command) that were left-truncated for the limits of detection or blank described above. We used a tobit model to address informative left-censoring that occurs below the limit of detection (or blank) for each assay. The tobit model allows us to fit a linear regression model in the detectable range, while designating undetectable biomarkers as below the detectable range (17). The fixed effects portion of the tobit model included diet assignment, visit (baseline or follow-up), and the interaction of these terms. The random effects portion of the tobit model included participant id (introducing a random intercept). While we attempted mixed effects models with a random slope for study visit, these models would not converge. As a sensitivity analysis, we used marginal, longitudinal tobit models with the variance clustered by participant, assuming missing specimens occurred completely at random. These models yielded similar results.

Standardized mean difference E-values (using unclustered standard deviations) were calculated for each of the between diet contrasts to estimate the minimum strength of association an unmeasured confounder would need to explain away the dietary associations with each cardiac biomarker (19). These sensitivity analyses are needed in this observational follow-up study.

Note that for kernel density plots we imputed the undetectable range of the biomarkers as two-thirds the distance to 0, using 0.333 for hs-cTnI (limit of blank), 1.067 for hs-cTnI (limit of detection), 3.333 for NT-proBNP, and 0.1067 for hs-CRP.

All analyses were conducted using Stata version 15.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) (see Supplement Material SM4 for code details). Missing data were evenly distributed across dietary assignments.

Funding

The funding source had no role in the study design, conduct, analysis, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Weighted and unweighted baseline characteristics of the participants of the DASH trial are shown in Table 1 (for unweighted characteristics by diet see Supplement Table ST3). There were minimal differences across dietary assignments. There were 19 participants missing from the three sites that contributed specimens. These participants were more likely to be black, and have higher LDL-cholesterol. Nevertheless, weighted characteristics were balanced across dietary assignments.

Table 1.

Weighted baseline characteristics according to diet assignment, mean (SE) or %

| Control, N = 108 | Fruits & Vegetables, N = 109 | DASH (Combination), N = 109 | Unweighted overall characteristics of those included, N=326* | Unweighted characteristics of those not included, N=19† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 44.7 (1.1) | 45.9 (1.1) | 44.5 (1.0) | 45.2 (0.6) | 47.2 (2.2) |

| Female, % | 45.1 | 43.4 | 52.0 | 48.2 | 31.6 |

| Black, % | 49.1 | 46.3 | 52.6 | 49.4 | 63.2 |

| Body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2, % | 36.2 | 34.8 | 34.4 | 36.2 | 31.6 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.0 (0.4) | 27.8 (0.4) | 28.2 (0.4) | 28.1 (0.2) | 27.4 (0.7) |

| Hypertension, % | 26.0 | 26.3 | 25.1 | 25.8 | 36.8 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 130.5 (1.1) | 131.3 (1.1) | 130.8 (1.0) | 131.0 (0.6) | 129.6 (2.5) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 84.8 (0.4) | 84.3 (0.5) | 84.1 (0.4) | 84.5 (0.3) | 83.9 (0.8) |

| Low density lipoprotein cholesterol, mg/dL | 120.9 (2.9) | 127.9 (2.9) | 118.7 (3.3) | 121.7 (1.8) | 141.7 (6.7) |

| Low density lipoprotein cholesterol, mmol/L | 3.1 (0.1) | 3.3 (0.1) | 3.1 (0.1) | 3.1 (0.0) | 3.7 (0.2) |

| Alcohol consumption, drinks/day | 1.4 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.3) |

| Physical activity, cal/kg/day | 37.6 (0.6) | 37.7 (0.6) | 37.7 (0.6) | 37.8 (0.4) | 36.9 (1.5) |

DASH represents “Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension”

Of the 332 participants with cardiac biomarkers measured from at least one visit, 5 did not have a baseline LDL-cholesterol measurement and 1 did not have a baseline activity score. As a result our analytic sample included 326 participants.

This number is based on the 3 research sites that provided specimens. In the original DASH study there were 4 research sites. One with 114 participants did not provide any specimens. Of the 19 participants not included in our study from the 3 research sites with specimens, only 13 had a measured LDL-cholesterol at baseline and only 18 had a physical activity score measured at baseline. The vast majority (13 of 19) were excluded because they did not have specimens available to measure cardiac biomarkers.

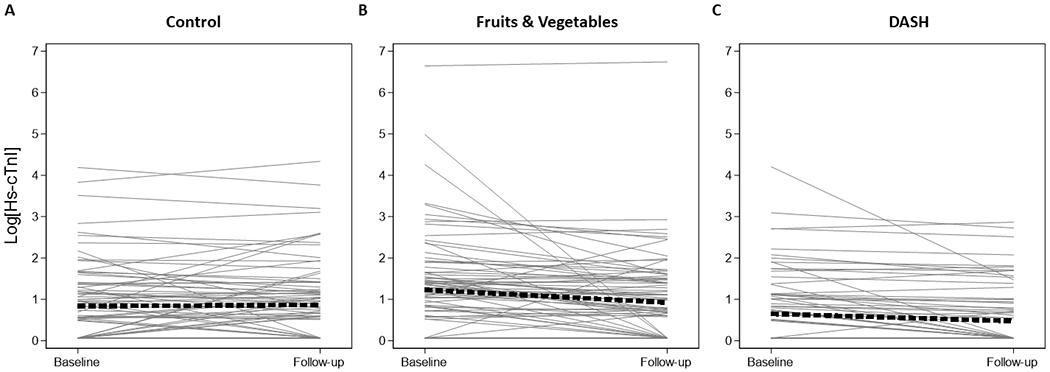

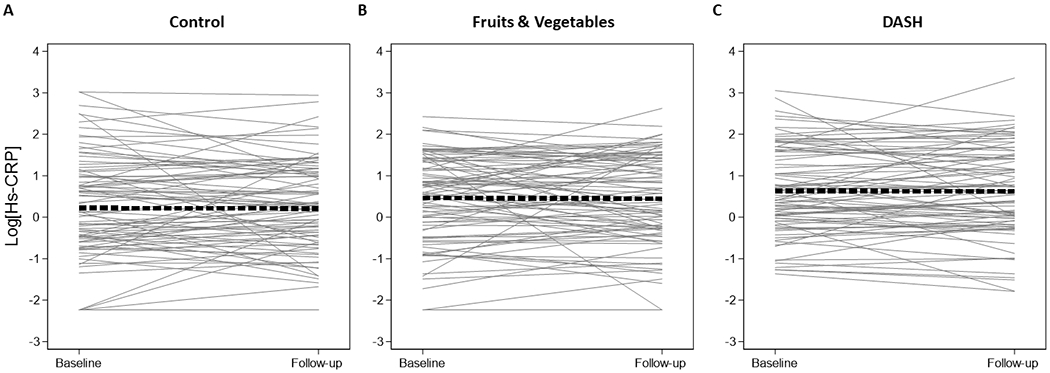

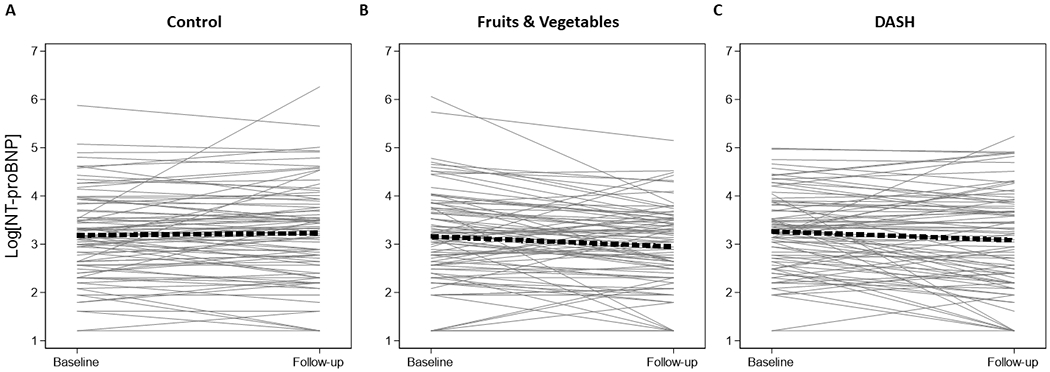

Change in Cardiac Biomarkers from Baseline

Individual change in biomarkers from baseline according to diet assignment are seen in Supplement Figures SF1 and Figures 2–4. Mean baseline concentrations of biomarkers were similar across diet assignments with the exception of hs-cTnI, which was higher in those assigned to the fruits and vegetables diet (Table 2 and Supplement Figures SF2–4). There were statistically significant changes in hs-cTnI (limit of detection) from baseline among those on the fruits and vegetables diet (−0.9; 95% CI: −1.5, −0.3 ng/L) and the DASH diet (−0.4; 95% CI: −0.6, −0.2 ng/L). There were also statistically significant changes in NT-proBNP from baseline observed among those assigned the fruits and vegetables diet (−4.6; 95% CI: −7.9, −1.2 pg/mL) and the DASH diet (−4.0; 95% CI: −7.3, −0.8 pg/mL). There was no change in baseline hs-CRP during any of the three diets.

Figure 2.

Spaghetti plots of high sensitivity cardiac troponin I (limit of detection, 1.6 ng/L)

Legend: Spaghetti plots of the within person change in natural log-transformed high sensitivity cardiac troponin I (ng/L), using the limit of detection (1.6 ng/L) at baseline and the follow-up visit after 8-weeks. These plots are limited to the 257 participants with both baseline and follow-up measurements. Panel A represents those assigned to the control diet (N=85), panel B represents those assigned to the fruits & vegetables diet (N=86), and panel C represents those assigned to the DASH diet (N=84). Values below the limit of blank were imputed as two-thirds the distance to zero (1.067 ng/L). The thick dashed line represents the average slope and intercept.

Figure 4.

Spaghetti plots of high sensitivity C-reactive protein

Legend: Spaghetti plots of the within person change in natural log-transformed high sensitivity C-reactive protein (mg/L) at baseline and the follow-up visit after 8-weeks. These plots are limited to the 257 participants with both baseline and follow-up measurements. Panel A represents those assigned to the control diet (N=85), panel B represents those assigned to the fruits & vegetables diet (N=86), and panel C represents those assigned to the DASH diet (N=84). The thick dashed line represents the average slope and intercept.

Table 2.

Mean baseline, 8-week, and difference in concentrations of cardiac biomarkers by diet assignment

| Baseline* | 8-week* | Absolute change from baseline† | %-Difference from Baseline‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High sensitivity cardiac troponin I (limit of blank: 0.5), ng/L | ||||

| Control | 1.4 (0.2) | 1.5 (0.2) | 0.1 (−0.2, 0.3) | 6.3 (−10.8, 26.5) |

| Fruits & Vegetables | 2.4 (0.4) | 1.5 (0.2) | −0.9 (−1.4, −0.4) | −37.2 (−49.5, −21.8) |

| DASH (Combination) | 1.2 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.1) | −0.3 (−0.6, −0.1) | −27.1 (−39.5, −12.3) |

| High sensitivity cardiac troponin I (limit of detection: 1.6), ng/L | ||||

| Control | 1.6 (0.2) | 1.7 (0.2) | 0.0 (−0.2, 0.3) | 2.8 (−13.5, 22.2) |

| Fruits & Vegetables | 2.7 (0.4) | 1.8 (0.2) | −0.9 (−1.5, −0.3) | −33.6 (−47.3, −16.4) |

| DASH (Combination) | 1.3 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.1) | −0.4 (−0.6, −0.2) | −30.4 (−42.0, −16.4) |

| N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, pg/mL | ||||

| Control | 23.1 (2.0) | 24.2 (2.3) | 1.0 (−1.7, 3.8) | 4.5 (−6.7, 17.0) |

| Fruits & Vegetables | 25.0 (2.3) | 20.4 (1.6) | −4.6 (−7.9, −1.2) | −18.3 (−29.0, −6.0) |

| DASH (Combination) | 24.6 (2.0) | 20.5 (2.0) | −4.0 (−7.3, −0.8) | −16.5 (−27.9, −3.2) |

| High sensitivity C-reactive protein, mg/L | ||||

| Control | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.1) | −0.0 (−0.2, 0.2) | −0.6 (−17.1, 19.1) |

| Fruits & Vegetables | 1.6 (0.2) | 1.5 (0.2) | −0.0 (−0.3, 0.2) | −2.8 (−19.2, 16.9) |

| DASH (Combination) | 1.7 (0.2) | 1.7 (0.2) | −0.0 (−0.3, 0.2) | −0.8 (−14.7, 15.2) |

DASH represents “Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension”

Note there were 108 participants assigned the control diet, 109 participants assigned the fruits & vegetables diet, and 109 participants assigned the DASH diet.

Estimates were derived via weighted mixed effects tobit models. Please reference main text for details.

Exponentiated log-transformed markers or the geometric mean

Difference in exponentiated log-transformed markers (i.e. difference in geometric means)

Exponentiated differences of the change on the log-scale

Conversions: 1 ng/L high sensitivity cardiac troponin I equals 0.001 mg/L; 1 pg/mL of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide equals 1 ng/L and 0.1182 pmol/L; 1 mg/L high sensitivity C-reactive protein equals 9.5238 nmol/L

Comparison between Randomized Dietary Assignments

Compared with the control diet, the fruits and vegetables diet reduced hs-cTnI (limit of detection) by 0.5 ng/L (95% CI: −0.9, −0.2 ng/L) and NT-proBNP by 0.3 pg/mL (95% CI: −0.5, −0.1) (Table 3 and Supplement Figures SF5–7). Compared with control, DASH reduced hs-cTnI by 0.5 ng/L (95% CI: −0.9, −0.1) and NT-proBNP by 0.3 pg/mL (95% CI: −0.5, −0.04). Hs-CRP did not differ between diets (Supplement Figure SF8), and none of the markers differed between DASH and fruits and vegetables diets.

Table 3.

Weighted differences in cardiac biomarkers between diets

| Absolute Difference | %-Difference | |

|---|---|---|

| High sensitivity cardiac troponin I (limit of blank: 0.5), ng/L | ||

| Fruits & Vegetables versus Control | −0.6 (−0.9, −0.3) | −40.8 (−55.3, −21.7) |

| DASH versus Control | −0.5 (−0.9, −0.1) | −31.4 (−46.9, −11.5) |

| Fruits & Vegetables versus DASH | −0.1 (−0.3, 0.1) | −13.7 (−35.1, 14.7) |

| High sensitivity cardiac troponin I (limit of detection: 1.6), ng/L | ||

| Fruits & Vegetables versus Control | −0.5 (−0.9, −0.2) | −35.4 (−51.5, −13.9) |

| DASH versus Control | −0.5 (−0.9, −0.1) | −32.3 (−47.4, −12.9) |

| Fruits & Vegetables versus DASH | −0.0 (−0.2, 0.2) | −4.6 (−27.8, 26.1) |

| N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, pg/mL | ||

| Fruits & Vegetables versus Control | −0.3 (−0.5, −0.1) | −21.8 (−34.7, −6.4) |

| DASH versus Control | −0.3 (−0.5, −0.0) | −20.1 (−33.7, −3.7) |

| Fruits & Vegetables versus DASH | −0.0 (−0.2, 0.1) | −2.2 (−20.2, 19.9) |

| High sensitivity C-reactive protein, mg/L | ||

| Fruits & Vegetables versus Control | −0.0 (−0.3, 0.2) | −2.2 (−24.5, 26.6) |

| DASH versus Control | −0.0 (−0.2, 0.2) | −0.2 (−21.2, 26.3) |

| Fruits & Vegetables versus DASH | −0.0 (−0.3, 0.2) | −2.0 (−22.8, 24.3) |

Conversions: 1 ng/L high sensitivity cardiac troponin I equals 0.001 mg/L; 1 pg/mL of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide equals 1 ng/L and 0.1182 pmol/L; 1 mg/L high sensitivity C-reactive protein equals 9.5238 nmol/L

E-values were greater for the fruits and vegetables versus control contrast with respect to hs-cTnI and NT-proBNP and for the DASH versus control contrast respect to hs-cTnI and NT-proBNP (Supplement Table ST4). This implies that only a strong confounder could explain away some of the estimated differences between diets in outcome, and shift the estimates toward the null enough so that the confidence bounds include zero.

Discussion

Both a diet rich in fruits and vegetables and the DASH diet were associated with lower subclinical cardiac damage and strain within an 8-week period. These associations did not differ between the DASH diet and the fruits and vegetables diet, and none of the diets affected hs-CRP, a marker of inflammation. We believe these findings strengthen recommendations for the DASH diet and more generally for increased consumption of fruits and vegetables as a means of optimizing cardiovascular health.

Observational evidence has consistently demonstrated that higher DASH diet consumption is associated with a lower risk of CVD events over time (20–22). Furthermore, we recently showed that 3 healthy DASH-like diets lowered hs-cTnI over a 6-week period irrespective of differences in their macronutrient content. However, the pre-post comparisons in our previous study were not controlled. In the present study, we demonstrated that compared to a typical American diet, two healthful diets rich in fruit and vegetables reduced subclinical cardiac damage and strain.

Our study demonstrated that both DASH and the fruits and vegetables diet reduced NT-proBNP, a marker of cardiac strain (23). Observational studies have shown that the DASH diet is associated with favorable left ventricular function (24) and a lower risk of heart failure (25–27) as well as greater exercise capacity (28) and a lower risk of mortality among those with heart failure (29). Our study suggests that dietary features common to both DASH and the fruits and vegetables diet, including but not limited to higher potassium, magnesium, and fiber, may be causative factors. Further research is needed to confirm whether similar diets can improve cardiac function in adults with established heart failure.

Multiple observational studies have described inverse relationships between DASH-patterned diets and CRP (32–34). Furthermore, several lifestyle interventions demonstrated CRP reduction in the setting of weight loss (35,36). In another trial, we demonstrated that three, isocaloric DASH-like diets reduced hs-CRP from baseline, but these comparisons lacked a temporal control (37). One controlled trial of an isocaloric, high fiber, DASH diet demonstrated CRP reduction only in a lean subpopulation (BMI <25 kg/m2) (38). The present study, with an average BMI of 28, did not observe any effect from diet on hs-CRP. We speculate that weight is a principal determinant of elevated hs-CRP among overweight and obese adults such that improvements in diet that do not reduce weight, may not influence hs-CRP concentrations.

In the original study, the DASH diet had greater effects on SBP, DBP, and LDL-c than the fruits and vegetables diet (7,16). However, these differences in CVD risk factors did not translate into significant differences in hs-cTnI and NT-proBNP between the fruits and vegetables diet and DASH at 8-weeks. While reductions in these markers reflect short-term improvements in subclinical CVD injury, their relationship with CVD events has been observed independent of pathways predicted by traditional risk factors (9–12). Thus, they do not necessarily capture, for example, long-term ischemic risk from atherosclerotic plaque burden and potential rupture (39). This distinction is important as the BP and cholesterol-reducing features of the DASH diet likely still play an important role in long-term CVD risk prevention. Further research is needed to study the longitudinal effects of the DASH diet on CVD events.

Our study had limitations. As specimens that had been collected in the DASH trial were not available for several of the original participants, findings are observational and susceptible to confounding. Nevertheless, E-values for hs-cTnI and NT-proBNP suggest that unmeasured confounding cannot explain the larger observed associations. The study duration of 8 weeks was short; effects of diet on clinical events could not be evaluated. Specimens were stored for at least 2 decades prior to measurement. While thought to be robust to freeze-thaw (40,41), hs-CRP measurements may have been affected by drift, contributing to its null relationship with the diets. Specific food groups or micronutrients that affected cardiac biomarker changes could not be isolated though the comparable changes seen with the DASH and fruits and vegetables diets suggest that micronutrients or food groups common to those two diets are likely involved. Of note, there were minor differences in sodium intake between diets, which we could not adjust for in our analyses. There was a large number of undetectable troponin concentrations, introducing model uncertainty. Nevertheless, findings were consistent even when we used the maximally reportable range. While protocol compliance was high, consumption of non-study foods could bias findings and increase imprecision. Variables used for weighting (e.g. self-reported alcohol use or physical activity) have measurement error and could also increase imprecision.

Our study also has several strengths. The dietary interventions were tightly controlled and administered in a randomized fashion. We examined highly sensitive cardiac markers in adults without established CVD. As a result, our study showed the short-term effects of diet on cardiac damage and strain, observations more proximal to actual CVD events. The use of isocaloric diets minimized the possibility of weight change and its effects on biomarkers, particularly hs-CRP. Higher E-values for the fruits and vegetables diet and the DASH diet versus control with respect to the hs-cTnI and NT-proBNP biomarkers suggest unmeasured confounding cannot explain the larger observed associations.

Our study has potential clinical implications. CVD is the leading cause of death in the United States (1). Large observational studies have consistently demonstrated that unhealthy food consumption is associated with greater risk of CVD events (20–22). As a result, many advocate for stronger government policies aimed at promoting healthier lifestyle behaviors (42). Meanwhile, critics point out the lack of causal evidence that a healthy diet prevents cardiovascular disease (43) and the lack of consensus over what defines a “heart-healthy” diet (44). Our study shows that what we eat impacts cardiac damage and strain in an 8-week time period. Moreover, it simplifies what is known about the minimum requirements for healthy eating for short-term cardiac benefits to this advice: consume more fruit, vegetables, nuts, seeds, and legumes and eat fewer snacks and sweets. This distilled list of food groups may be more easily targeted by public policy.

Supplementary Material

Figure 3.

Spaghetti plots of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide

Legend: Spaghetti plots of the within person change in natural log-transformed N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (pg/mL) at baseline and the follow-up visit after 8-weeks. These plots are limited to the 257 participants with both baseline and follow-up measurements. Panel A represents those assigned to the control diet (N=85), panel B represents those assigned to the fruits & vegetables diet (N=86), and panel C represents those assigned to the DASH diet (N=84). The thick dashed line represents the average slope and intercept.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the study participants for their sustained commitment to the DASH Trial.

We thank Siemens (Siemens Healthineers, Malvern, Pennsylvania) for donating test assays and kits for the three cardiac biomarkers measured in this study.

This trial is registered at clinicaltrials.gov, number: NCT00000544.

Sources of Funding

SPJ supported by a NIH/NHLBI K23HL135273. The measurement of cardiac biomarkers was supported by NIH/NHLBI R21HL144876. Siemens donated the assays used for this study.

The original DASH trial was supported by grants (HL50981, HL50968, HL50972, HL50977, HL50982, HL02642, RR02635, and RR00722) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the Office of Research on Minority Health, and the National Center for Research Resources of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations used:

- BMI

body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- DASH

Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension

- DBP

diastolic blood pressure

- LDL-c

low density lipoprotein cholesterol

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chang AR, Cheng S, Chiuve SE, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2018 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018. January 1;CIR.0000000000000558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mozaffarian D, Liu J, Sy S, Huang Y, Rehm C, Lee Y, et al. Cost-effectiveness of financial incentives and disincentives for improving food purchases and health through the US Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): A microsimulation study. PLOS Medicine. 2018. October 2;15(10):e1002661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacLeod SM, Cairns JA. Controversial sodium guidelines: scientific solution or perpetual debate? CMAJ. 2015. February 3;187(2):95–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alderman MH, Cohen HW. Dietary sodium intake and cardiovascular mortality: controversy resolved? Am J Hypertens. 2012. July;25(7):727–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Donnell M, Mann JFE, Schutte AE, Staessen JA, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Thomas M, et al. Dietary Sodium and Cardiovascular Disease Risk. N Engl J Med. 2016. 15;375(24):2404–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, Covas M-I, Corella D, Arós F, et al. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil or Nuts. N Engl J Med. 2018. June 21;378(25):e34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, Svetkey LP, Sacks FM, et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. DASH Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1997. April 17;336(16):1117–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DASH Diet: What To Know | US News Best Diets [Internet]. [cited 2018 Jan 25]. Available from: https://health.usnews.com/best-diet/dash-diet

- 9.Jia X, Sun W, Hoogeveen RC, Nambi V, Matsushita K, Folsom AR, et al. High-Sensitivity Troponin I and Incident Coronary Events, Stroke, Heart Failure Hospitalization, and Mortality in the ARIC Study. Circulation. 2019. June 4;139(23):2642–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samman Tahhan A, Sandesara P, Hayek SS, Hammadah M, Alkhoder A, Kelli HM, et al. High-Sensitivity Troponin I Levels and Coronary Artery Disease Severity, Progression, and Long-Term Outcomes. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018. 21;7(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Everett BM, Berger JS, Manson JE, Ridker PM, Cook NR. B-type Natriuretic Peptides Improve Cardiovascular Disease Risk Prediction in a Cohort of Women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014. October 28;64(17):1789–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zile MR, Claggett BL, Prescott MF, McMurray JJV, Packer M, Rouleau JL, et al. Prognostic Implications of Changes in N-Terminal Pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide in Patients With Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016. December 6;68(22):2425–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parrinello CM, Lutsey PL, Ballantyne CM, Folsom AR, Pankow JS, Selvin E. Six-year change in high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and mortality. Am Heart J. 2015. August;170(2):380–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bower JK, Lazo M, Matsushita K, Rubin J, Hoogeveen RC, Ballantyne CM, et al. N-Terminal Pro-Brain Natriuretic Peptide (NT-proBNP) and Risk of Hypertension in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am J Hypertens. 2015. October;28(10):1262–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rubin J, Matsushita K, Ballantyne CM, Hoogeveen R, Coresh J, Selvin E. Chronic hyperglycemia and subclinical myocardial injury. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012. January 31;59(5):484–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Obarzanek E, Sacks FM, Vollmer WM, Bray GA, Miller ER, Lin P-H, et al. Effects on blood lipids of a blood pressure–lowering diet: the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001. July 1;74(1):80–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sattar A, Weissfeld LA, Molenberghs G. Analysis of non-ignorable missing and left-censored longitudinal data using a weighted random effects tobit model. Stat Med. 2011. November 30;30(27):3167–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seaman SR, White IR. Review of inverse probability weighting for dealing with missing data. Stat Methods Med Res. 2013. June 1;22(3):278–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.VanderWeele TJ, Ding P. Sensitivity Analysis in Observational Research: Introducing the E-Value. Ann Intern Med. 2017. August 15;167(4):268–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fung TT, Chiuve SE, McCullough ML, Rexrode KM, Logroscino G, Hu FB. Adherence to a DASH-style diet and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in women. Arch Intern Med. 2008. April 14;168(7):713–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sotos-Prieto M, Bhupathiraju SN, Mattei J, Fung TT, Li Y, Pan A, et al. Association of Changes in Diet Quality with Total and Cause-Specific Mortality. N Engl J Med. 2017. 13;377(2):143–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Folsom AR, Parker ED, Harnack LJ. Degree of concordance with DASH diet guidelines and incidence of hypertension and fatal cardiovascular disease. Am J Hypertens. 2007. March;20(3):225–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKie PM, Burnett JC. NT-proBNP: The Gold Standard Biomarker in Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016. December 6;68(22):2437–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguyen HT, Bertoni AG, Nettleton JA, Bluemke DA, Levitan EB, Burke GL. DASH eating pattern is associated with favorable left ventricular function in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Nutr. 2012. December;31(6):401–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hummel SL, Seymour EM, Brook RD, Sheth SS, Ghosh E, Zhu S, et al. Low-sodium DASH diet improves diastolic function and ventricular-arterial coupling in hypertensive heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2013. November;6(6):1165–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campos CL, Wood A, Burke GL, Bahrami H, Bertoni AG. Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Diet Concordance and Incident Heart Failure: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am J Prev Med. 2019. June;56(6):819–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levitan EB, Wolk A, Mittleman MA. Consistency with the DASH diet and incidence of heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2009. May 11;169(9):851–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rifai L, Pisano C, Hayden J, Sulo S, Silver MA. Impact of the DASH diet on endothelial function, exercise capacity, and quality of life in patients with heart failure. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2015. April;28(2):151–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levitan EB, Lewis CE, Tinker LF, Eaton CB, Ahmed A, Manson JE, et al. Mediterranean and DASH diet scores and mortality in women with heart failure: The Women’s Health Initiative. Circ Heart Fail. 2013. November;6(6):1116–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McEvoy JW, Chen Y, Ndumele CE, Solomon SD, Nambi V, Ballantyne CM, et al. Six-Year Change in High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin T and Risk of Subsequent Coronary Heart Disease, Heart Failure, and Death. JAMA Cardiol. 2016. August 1;1(5):519–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ford I, Shah ASV, Zhang R, McAllister DA, Strachan FE, Caslake M, et al. High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin, Statin Therapy, and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016. December 27;68(25):2719–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brighenti F, Valtueña S, Pellegrini N, Ardigò D, Del Rio D, Salvatore S, et al. Total antioxidant capacity of the diet is inversely and independently related to plasma concentration of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in adult Italian subjects. Br J Nutr. 2005. May;93(5):619–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waldeyer C, Brunner FJ, Braetz J, Ruebsamen N, Zyriax B-C, Blaum C, et al. Adherence to Mediterranean diet, high-sensitive C-reactive protein, and severity of coronary artery disease: Contemporary data from the INTERCATH cohort. Atherosclerosis. 2018. August;275:256–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lahoz C, Castillo E, Mostaza JM, de Dios O, Salinero-Fort MA, González-Alegre T, et al. Relationship of the Adherence to a Mediterranean Diet and Its Main Components with CRP Levels in the Spanish Population. Nutrients. 2018. March 20;10(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Esposito K, Pontillo A, Di Palo C, Giugliano G, Masella M, Marfella R, et al. Effect of weight loss and lifestyle changes on vascular inflammatory markers in obese women: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003. April 9;289(14):1799–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Azadbakht L, Izadi V, Surkan PJ, Esmaillzadeh A. Effect of a High Protein Weight Loss Diet on Weight, High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein, and Cardiovascular Risk among Overweight and Obese Women: A Parallel Clinical Trial. Int J Endocrinol. 2013;2013:971724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kovell LC, Yeung EH, Miller ER, Appel LJ, Christenson RH, Rebuck H, et al. Healthy diet reduces markers of cardiac injury and inflammation regardless of macronutrients: Results from the OmniHeart trial. Int J Cardiol. 2019. August 2; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.King DE, Egan BM, Woolson RF, Mainous AG, Al-Solaiman Y, Jesri A. Effect of a high-fiber diet vs a fiber-supplemented diet on C-reactive protein level. Arch Intern Med. 2007. March 12;167(5):502–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ference BA, Ginsberg HN, Graham I, Ray KK, Packard CJ, Bruckert E, et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur Heart J. 2017. August 21;38(32):2459–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doumatey AP, Zhou J, Adeyemo A, Rotimi C. High sensitivity C-reactive protein (Hs-CRP) remains highly stable in long-term archived human serum. Clin Biochem. 2014. March;47(0):315–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kleeberger C, Shore D, Gunter E, Sandler DP, Weinberg CR. The Effects of Long-Term Storage on Commonly Measured Serum Analyte Levels. Epidemiology. 2018. May;29(3):448–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anderson CAM, Thorndike AN, Lichtenstein AH, Van Horn L, Kris-Etherton PM, Foraker R, et al. Innovation to Create a Healthy and Sustainable Food System: A Science Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019. June 4;139(23):e1025–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nissen SE. U.S. Dietary Guidelines: An Evidence-Free Zone. Ann Intern Med. 2016. April 19;164(8):558–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramsden CE, Domenichiello AF. PURE study challenges the definition of a healthy diet: but key questions remain. Lancet. 2017. 04;390(10107):2018–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.