Abstract

Objective:

To analyze the impact of adjuvant radiation therapy (RT) on overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) in patients with verrucous carcinoma (VC) as compared to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the oral cavity.

Study Design:

Cross-sectional population analysis.

Methods:

Cases of nonmetastatic VC/SCC of the oral cavity were extracted from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database (1988–2013). Kaplan-Meier survivals, stratified according to T stage, were compared between VC and SCC for treatment with or without adjuvant RT.

Results:

A total of 18,819 VC/SCC cases were identified. There were 581 (3.1%) VC (mean age 69.6 years, 48.9% female) versus 18,238 (97.0%) SCC (mean age, 65.3, 37.1% female) patients. Verrucous carcinoma patients receiving surgery alone (N = 539) demonstrated a trend toward improved OS versus VC patients receiving surgery and RT (N = 40) (117.0 vs.71.4 months, respectively, P = 0.119). There was a statistically significant improvement in DSS in VC patients receiving surgery alone (217.2 vs. 110.9 months, P = 0.05). Verrucous carcinoma patients treated with adjuvant RT demonstrated a trend toward a worse OS (71.4 vs. 93.0 months, P = 0.992) and DSS (110.9 vs. 162.3 months, P = 0.275) compared to SCC treated with adjuvant RT, suggesting a different biology and radiosensitivity between VC and SCC.

Conclusion:

Verrucous carcinoma treated with adjuvant RT had a worse OS and DSS compared to both VC treated with surgery alone and SCC treated with surgery and adjuvant RT. Consideration should be given to surgical re-section rather than adjuvant RT in patients with positive margins or local recurrence.

Keywords: Verrucous carcinoma, SEER, cancer, oral cavity, head and neck cancer, survival, T stage, radiation therapy

INTRODUCTION

In 1941, when U.S. military rations typically included tobacco products, Friedell and Rosenthal first reported on eight oral tumors with “papillary verrucoid character,” which they attributed to chewing tobacco.1 Later in 1948, Ackerman presented a larger series with a thorough pathologic description of oral verrucous carcinoma (VC), which defined the morphologic findings.2 Verrucous carcinoma is a rare, well-differentiated, indolent tumor that represents approximately 2% to 8% of all squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) in the head and neck region.3,4 A 2001 survey by the National Cancer Database reported the oral cavity as the most commonly involved site,5 followed by the larynx.6 Grossly, the tumor appears whitish to gray in color and can be wart-like and/or present as a fungating mass that locally invades surrounding tissue. The histologic appearance is described as hyperkeratotic with papillary fronds, lack of atypia, and a sharply demarcated deep margin.2,3 Diagnosis is problematic because biopsies can mistakenly be read as papilloma due to inadequate sample depth. By not capturing the junction between the tumor and basement membrane, the well-differentiated rete pegs at the base of the lesion with pushing epithelial nests can be missed, as well as the characteristic absence of true invasion of the basement membrane.2,4,7

True oral VC is rarely associated with regional or distant metastasis, which is a distinguishing feature from oral SCC. The exception to regional or distant metastasis is if there is a component of conventional SCC that arises within the VC.7 Wide local excision is the most effective treatment.2,4,7–11 The use of radiotherapy (RT) for VC has been controversial because there have been reports about the possibility of anaplastic transformation of VC after RT. Early reports of local recurrence after RT suggested this possibility; therefore, radiation was advocated only for select clinical situations.4,8,12,13 However, more recent work suggests that the observed local recurrence of VC after RT is most likely due to remnant foci of carcinoma.9 Reports on oral cavity VC have been limited to case series, and few studies have included robust survival analysis. Given the limited number of VC cases that can be evaluated and studied within a single institution, it has been difficult to conduct a population-based analysis to determine survival outcomes in VC patients, and furthermore, the impact of RT on survival.

A program of the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) database, collects and distributes cancer incidence and survival data from cancer registries across the United States, covering roughly one-quarter of the national population, and has been previously used to address survival analyses of many types of head and neck cancers. In this study, we queried the SEER database to evaluate the impact of adjuvant RT on clinical outcomes in VC patients, as well as compared the survival outcomes of VC patients to conventional SCC oral cavity patients treated with adjuvant RT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study population was extracted from the SEER database restricted to the calendar years of cancer diagnosis from 1988 to 2013, for which detailed staging would be available. This study was reviewed and received an exemption from institutional review board approval as research involving publicly available, de-identified data. Both VC and conventional SCC of the oral cavity site were extracted from the SEER database. Exclusion criteria included cases without a recorded T (tumor) stage, radiation treatment given in the nonadjuvant setting, and documentation of nodal (N+) or distant metastasis because such cases might have other indications for RT. For each case, sex, year of diagnosis, tumor histopathology, extent of disease, survival time, and vital status were extracted and tabulated. Data were individually verified to ensure correct histopathologic designation for VC and SCC. Standard demographic data for VC and SCC cases were computed. T stage was individually computed from the extent of disease SEER variables to correspond to the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system.

For VC and SCC of the oral cavity, the following comparative analyses were performed. In the first cohort comparison, differences in overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) between VC cases that received surgery alone and those treated with surgery and adjuvant RT, stratified according to T stage, were analyzed. Survival comparisons were conducted with the Kaplan-Meier method (KM) and compared using the log-rank test. In the second cohort comparison, differences in OS and DSS between cases of VC treated with adjuvant RT and conventional SCC treated with adjuvant RT, stratified according to T stage, was then performed. T-stage stratification was limited to subgroups with n > 5 for adequate sample sizing.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis was then conducted, including tumor histopathology type (VC vs. SCC), T stage, and adjuvant RT to compare overall and disease-specific survival between the two groups. Statistical significance was set at P <0.05.

RESULTS

For the time period under analysis, 40,239 cases of VC and conventional SCC of the oral cavity were identified. After selecting for those cases with known T stage, as well as the absence of both nodal and distant metastases (N0M0), 18,819 cases were identified. Of those, 581 (3.1%) were VC and 18,238 (96.9%) were conventional oral cavity SCC. Demographic data are shown in Table I. The mean age at diagnosis for VC was slightly higher than for conventional SCC (69.6 years vs. 65.3 years, P < 0.001), and there was a slight male predominance among VC patients (51.1%, P < 0.001).

TABLE I.

Demographics.

| VC | SCC | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 284 | 6773 | 7057 |

| Male | 297 | 11465 | 11762 |

| Mean age at diagnosis | 69.6 | 65.3 | – |

| T1 | 243 | 10261 | 10504 |

| T2 | 201 | 4794 | 4995 |

| T3 | 66 | 1094 | 1160 |

| T4 | 71 | 2089 | 2160 |

| Total | 581 | 18238 | 18819 |

SCC = squamous cell carcinoma; VC = verrucous carcinoma.

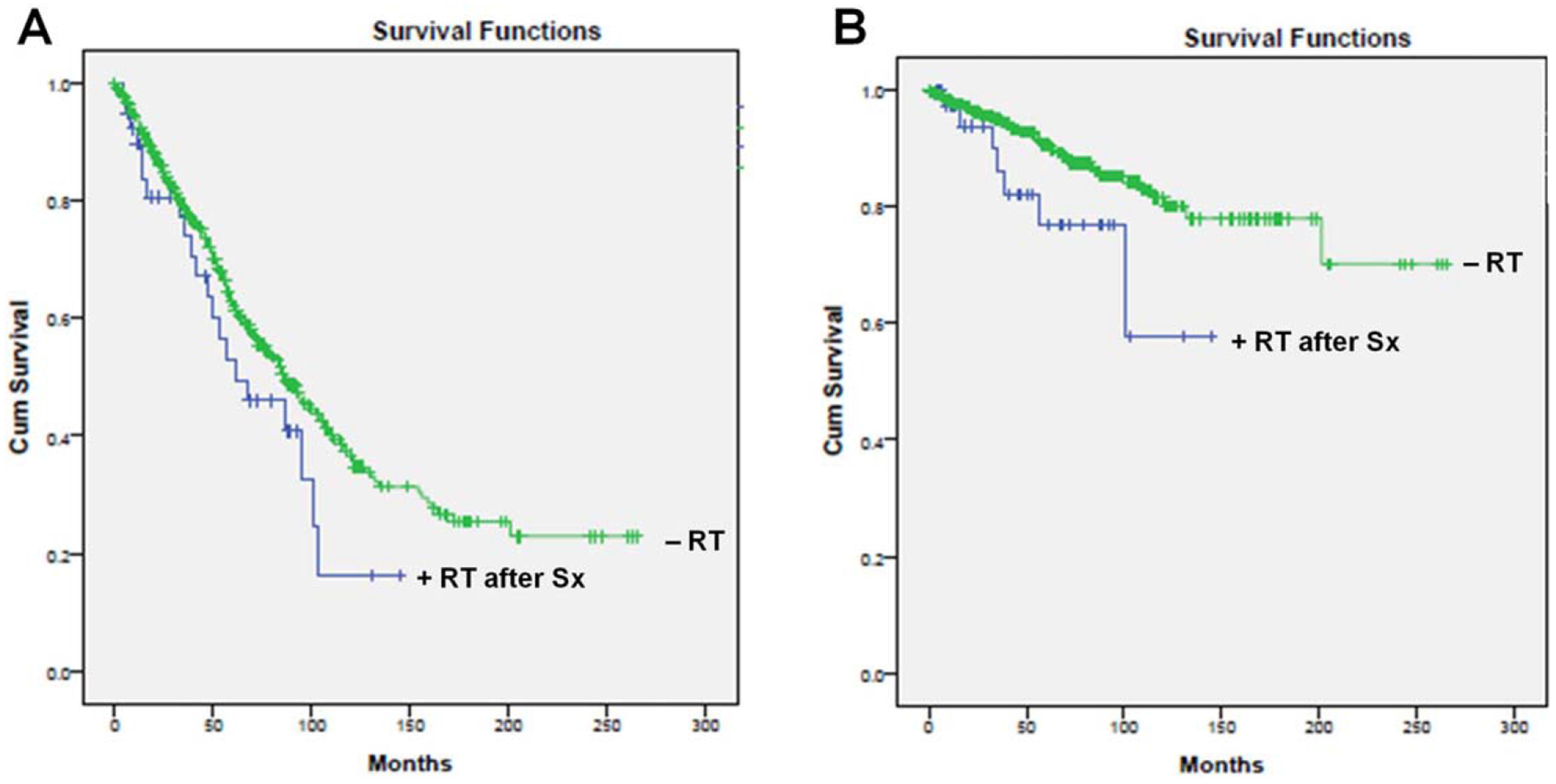

Verrucous carcinoma patients treated with surgery alone demonstrated a mean OS of 117.0 months as compared to 71.4 months for age- and sex-matched VC patients treated with surgery and adjuvant RT (P = .119). Figure 1A displays the KM OS curves for pooled VC patients treated with or without adjuvant RT. When stratified by T stage, patients who received adjuvant RT demonstrated poorer OS across all T stages, although this did not reach statistical significance according to T stage (T1, P = 0.431; T2, P = 0.948; T3, P = 0.736; T4, P = 0.438). The relatively low number of VC patients (N = 40) treated with adjuvant RT most likely contributed to the lack of statistical significance. The mean OS stratified by T stage are summarized in Table II.

Fig. 1.

(A) Overall survival (P = 0.119), B) Disease-specific survival (P = 0.05) based on overall pooled data for verrucous carcinoma patients treated with or without adjuvant radiation therapy. Cum = cumulative; RT = radiation therapy; Sx = surgery.

TABLE II.

OS in VC Patients Treated With or Without Adjuvant RT

| Mean* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% Confidence Interval | ||||||

| T Stage (AJCC 6th ed.) | Adjuvant RT | Estimate | SE | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | P Value |

| T1 | RT after surgery | 90.6 | 24.642 | 42.301 | 138.899 | |

| No RT | 135.518 | 10.928 | 114.099 | 156.936 | ||

| Overall | 135.964 | 10.801 | 114.795 | 157.133 | 0.431 | |

| T2 | RT after surgery | 78.31 | 14.615 | 49.665 | 106.954 | |

| No RT | 107.4 | 8.922 | 89.912 | 124.887 | ||

| Overall | 107.139 | 8.728 | 90.031 | 124.246 | 0.948 | |

| T3 | RT after surgery | 75.667 | 13.087 | 50.017 | 101.316 | |

| No RT | 81.353 | 9.802 | 62.141 | 100.564 | ||

| Overall | 80.887 | 9.295 | 62.67 | 99.104 | 0.736 | |

| T4 | RT after surgery | 59.714 | 9.936 | 40.241 | 79.188 | |

| No RT | 92.253 | 12.554 | 67.646 | 116.859 | ||

| Overall | 87.355 | 10.775 | 66.236 | 108.474 | 0.438 | |

| Overall | Overall | 115.05 | 5.755 | 103.77 | 126.33 | |

Estimation is limited to the largest survival time if it is censored.

OS = overall survival; RT radiation therapy; SE = standard error; T = tumor; VC = verrucous carcinoma.

Similarly, when evaluating DSS, VC patients treated with surgery alone had a mean DSS of 217.2 months as compared to 110.9 months for age- and sex-matched VC patients who received adjuvant RT (P = 0.05) (Fig. 1B). When stratified by T stage, VC patients treated with adjuvant RT had poorer mean DSS among T1, T2 and T4 disease, although again this did not reach statistical significance (T1, P = 0.096; T2, P = 0.216; T4, P = 0.604). Mean DSS stratification by T stage was unable to be performed due to an insufficient sample size. In summary, VC patients treated with adjuvant RT demonstrated a trend toward worse OS and DSS as compared to VC patients who were treated with surgery alone.

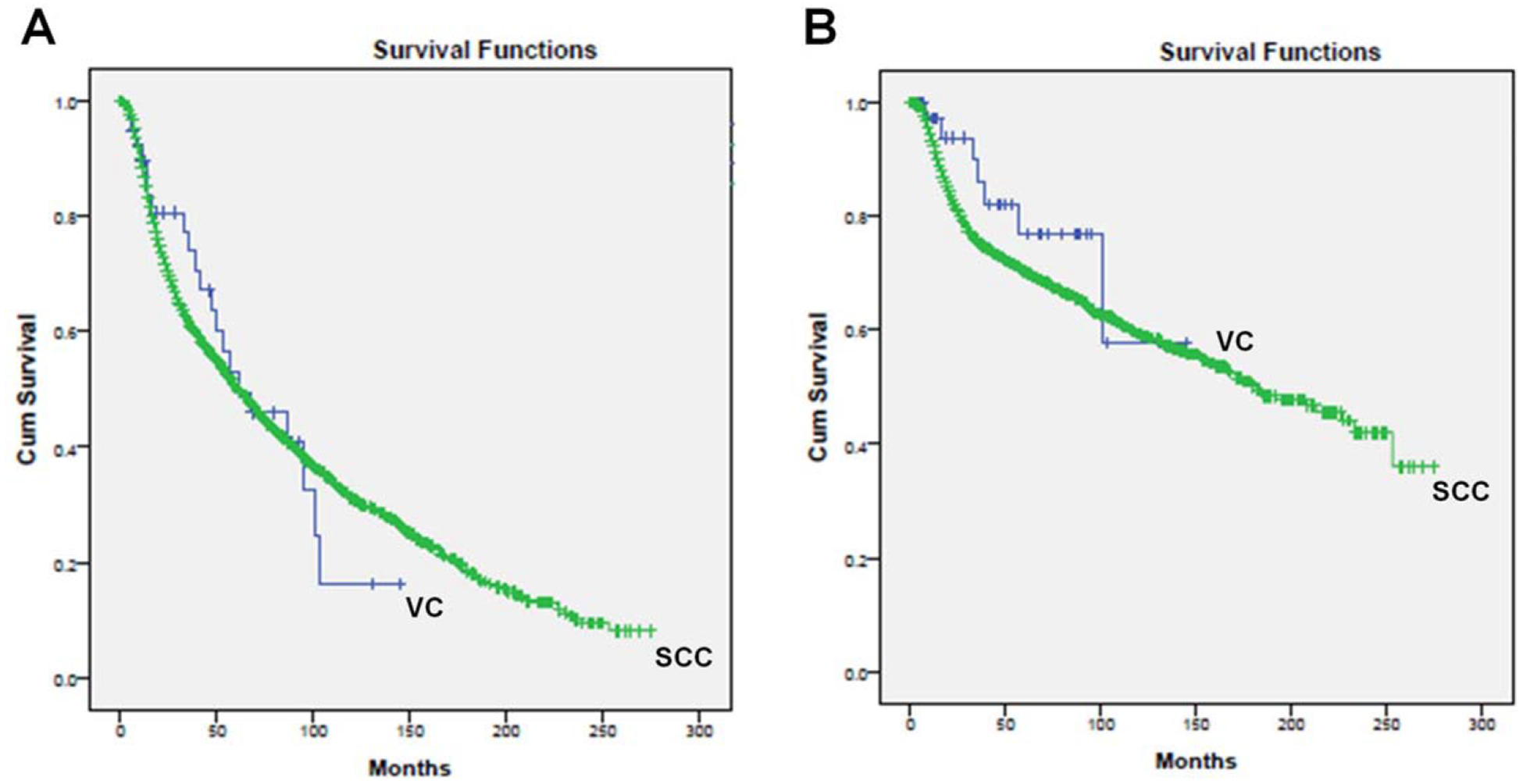

To determine whether patients selected for adjuvant RT may bias the results, we compared the OS and DSS between VC- and oral-cavity SCC patients both treated with adjuvant RT. Including only those patients with known T stage, N0M0 disease, and documented treatment with adjuvant RT, 3,256 cases were identified. Of those, 40 (1.2%) were VC, and 3,216 (98.8%) were SCC patients.

Figure 2A displays the KM OS curves based on pooled data. Verrucous carcinoma patients treated with adjuvant RT had a mean OS of 71.4 months as compared to 93.0 months in age- and sex-matched patients with conventional SCC treated with adjuvant RT (P = 0.992). When stratified by T stage, VC patients trended toward worse mean OS as compared to the conventional SCC patients across all T stages (T1, P = 0.845; T2, P = 0.563; T3, P = 0.520; T4, P = 0.789), as summarized in Table III. Similarly, DSS was 110.9 months for VC cases as compared to 162.3 months for SCC (P = 0.275) (Fig. 2B), and this trend remained when stratified by T stage for T1, T2, and T4 disease (T1, P = 0.943; T2, P = 0.454; T4, P = 0.463). The mean DSS stratified by T stage was not calculated due to insufficient sample size. Statistical significance was not reached in the OS and DSS analyses, most likely due to the relatively low numbers of VC patients (N = 40) as compared to the oral cavity SCC patients (N = 3,216).

Fig. 2.

(A) Overall survival (P = 0.992), (B) Disease-specific survival (P = 0.275) based on overall pooled data for verrucous carcinoma versus SCC patients treated with adjuvant radiation therapy. Cum = cumulative; SCC = squamous cell carcinoma; VC = verrucous carcinoma.

TABLE III.

OS in VC and SCC Patients Treated With Adjuvant RT.

| Mean* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% Confidence Interval | ||||||

| T Stage (AJCC 6th ed.) | Histology | Estimate | SE | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | P Value |

| T1 | Verrucous Carcinoma | 90.6 | 24.642 | 42.301 | 138.899 | |

| SCC | 109.532 | 3.967 | 101.757 | 117.307 | ||

| Overall | 109.607 | 3.964 | 101.838 | 117.376 | 0.845 | |

| T2 | Verrucous Carcinoma | 78.31 | 14.615 | 49.665 | 106.954 | |

| 8070 SCC | 88.803 | 3.293 | 82.35 | 95.257 | ||

| Overall | 88.882 | 3.281 | 82.451 | 95.312 | 0.563 | |

| T3 | Verrucous Carcinoma | 75.667 | 13.087 | 50.017 | 101.316 | |

| SCC | 79.233 | 5.667 | 68.125 | 90.341 | ||

| Overall | 79.321 | 5.627 | 68.293 | 90.349 | 0.52 | |

| T4 | Verrucous Carcinoma | 59.714 | 9.936 | 40.241 | 79.188 | |

| SCC | 79.385 | 3.344 | 72.83 | 85.941 | ||

| Overall | 79.091 | 3.295 | 72.632 | 85.549 | 0.789 | |

| Overall | Overall | 92.95 | 2.075 | 88.884 | 97.017 | |

Estimation is limited to the largest survival time if it is censored.

OS = overall survival; RT radiation therapy; SCCA = squamous cell carcinoma; SE = standard error; T = tumor; VC = verrucous carcinoma.

DISCUSSION

In general, oral VC has an excellent prognosis with surgical treatment, as reported in multiple case series,4,5,9,10,12,14 although there are a few reports of recurrence after surgery, likely due to inadequate margins or missed occult foci of SCC.9,15,16 The role of RT has been unclear with some groups and its use primarily limited to remnant microscopic disease after surgery, local and/or distant recurrence, lesions not amenable to surgical resection, or patients who may not be candidates for surgery. However, in accordance with the present study, data from multiple groups suggest that patients with oral VC who receive RT have worse outcomes than those treated with surgery alone.

Vidyasagar et al. reported an overall 5-year survival rate of 49% of 107 oral VC cases treated with primary RT.17 When stratifying tumors by T stage, they reported survival to be 100% in T1 (3 patients), 46% in T2 (27 patients), 34% in T3 (35 patients), and 16% in T4 (42 patients). Nair et al. reported a 44% 3-year survival rate in 52 cases of oral VC that received RT.18 In 1998, Tharp and Shidnia compared primary surgical and RT outcomes and reported that treatment with surgery alone achieved disease control in 75% to 85% of cases, and approached 95% when salvage procedures were included.9 In contrast, local disease control with primary RT was less than 50%. The rare incidence of this tumor has made large studies (> 500 patients) within a single institution difficult; thus, most studies in the literature report on smaller case series.

In 2001, Koch et al. published the results from a national survey on oral cavity and laryngeal VC management trends and outcomes using the National Cancer Database. The group identified 2,350 cases of VC diagnosed between 1985 and 1996. They reported that primary RT was associated with a worse survival compared to primary surgical treatment.5 The 5-year relative survival rate was 41.8% in VC treated with radiation alone, as compared to 85.7% for cases treated with surgery alone, and 68.4% when patients received both surgery and RT. They also reported that patients receiving upfront surgery had better survival than those treated with neoadjuvant RT, especially for cases originating in the oral cavity. In our study, we queried the SEER database from 1998 to 2013 and confirmed that VC patients treated with adjuvant RT had a worse OS and DSS, which was independent of T stage, as compared to VC patients treated with surgery alone. Furthermore, our results demonstrate that VC patients treated with adjuvant RT trended toward worse OS and DSS than SCC patients treated with adjuvant RT, which may imply a different biology and radiosensitivity between these two histopathologies. Radiation therapy targets rapidly dividing cells by causing DNA damage during tumor cell replication and, given the low mitotic activity associated with VC,19–21 the VC cells may not be as susceptible to radiation-induced tumor cell apoptosis. The indications for postoperative RT include pathologic features concerning for aggressive disease (e.g., local invasion, perineural, or perivascular invasion), as well as the presence of a positive tumor margin. Because VC is a disease that may be relatively resistant to adjuvant RT, any remnant microscopic disease within the surgical bed may best be treated with surgical reresection rather than adjuvant RT.

A limitation of our study is the overall sample size of VC cases available to include in our analysis. Despite using a large national cancer database that spans a 25-year period, the VC cases that met our criteria of documented T stage, node-negative disease treated with or without adjuvant RT, were still insufficient to reach statistical significance when evaluating OS, although trends were observed and significance only achieved with DSS in the pooled analysis. Node-positive VC patients were excluded to remove any possible confounding factors that may influence indications for adjuvant RT delivered to the primary site. Additional studies are needed to investigate the role of RT in (N+) VC patients.

CONCLUSION

Radiation therapy targets rapidly dividing cells by causing DNA damage during tumor cell replication and, given the low mitotic activity associated with VC, VC may not be sensitive to radiation-induced tumor cell apoptosis, leading to worse OS and DSS in VC patients receiving adjuvant RT. Consideration should be made for a surgical re-resection in those cases found to have a positive pathologic margin rather than adjuvant RT due to concerns of persistent local disease remaining after RT.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Friedell H, Rosenthal L. The etiologic role of chewing tobacco in cancer of the mouth: report of eight cases treated with radiation. J Am Med Assoc 1941;116:2130–2135. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ackerman LV. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Surgery 1948;23: 670–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batsakis JG, Hybels R, Crissman JD, Rice DH. The pathology of head and neck tumors: verrucous carcinoma, Part 15. Head Neck Surg 1982;5:29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kraus FT, Perezmesa C. Verrucous carcinoma. Clinical and pathologic study of 105 cases involving oral cavity, larynx and genitalia. Cancer 1966;19:26–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koch BB, Trask DK, Hoffman HT, et al. National survey of head and neck verrucous carcinoma: patterns of presentation, care, and outcome. Cancer 2001;92:110–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dubal PM, Svider PF, Kam D, Dutta R, Baredes S, Eloy JA. Laryngeal verrucous carcinoma a population-based analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2015;153:799–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel KR, Chernock RD, Sinha P, Muller S, El-Mofty SK, Lewis JS. Verrucous carcinoma with dysplasia or minimal invasion: a variant of verrucous carcinoma with extremely favorable prognosis. Head Neck Pathol 2015;9:65–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fonts EA, Greenlaw RH, Rush BF, Rovin S. Verrucous squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Cancer 1969;23:152–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tharp ME, Shidnia H. Radiotherapy in the treatment of verrucous carcinoma of the head and neck. Laryngoscope 1995;105:391–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walvekar RR, Chaukar DA, Deshpande MS, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity: a clinical and pathological study of 101 cases. Oral Oncol 2009;45:47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rajendran R, Varghese I, Sugathan CK, Vijayakumar T. Ackerman’s tumour (verrucous carcinoma) of the oral cavity: a clinico-epidemiologic study of 426 cases. Aust Dent J 1988;33:295–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perez CA, Kraus FT, Evans JC, Powers WE. Anaplastic transformation in verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity after radiation therapy. Radiology 1966;86:108–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferlito A, Rinaldo A, Mannara GM. Is primary radiotherapy an appropriate option for the treatment of verrucous carcinoma of the head and neck? J Laryngol Otol 1998;112:132–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medina JE, Dichtel W, Luna MA. Verrucous-squamous carcinomas of the oral cavity. A clinicopathologic study of 104 cases. Arch Otolaryngol Chic Ill 1960 1984;110:437–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demian SDE, Bushkin FL, Echevarria RA. Perineural invasion and anaplastic transformation of verrucous carcinoma. Cancer 1973;32:395–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDonald JS, Crissman JD, Gluckman JL. Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity. Head Neck Surg 1982;5:22–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vidyasagar MS, Fernandes DJ, Kasturi DP, et al. Radiotherapy and verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity. A study of 107 cases. Acta Oncol Stockh Swed 1992;31:43–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nair MK, Sankaranarayanan R, Padmanabhan TK, Madhu CS. Oral verrucous carcinoma: treatment with radiotherapy. Cancer 1988;61:458–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terada T Verrucous carcinoma of the oral cavity: a histopathologic study of 10 Japanese cases. J Maxillofac Oral Surg 2011;10:148–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rinker MH, Fenske NA, Scalf LA, Glass LF. Histologic variants of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Cancer Control J Moffitt Cancer Cent 2001;8:354–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.PathologyOutlines. Verrucous carcinoma. 2015. Available at: http://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/oralcavityverrucous.html. Accessed March 28, 2016.