Abstract

Responses to the COVID-19 pandemic may leave many people behind through a variety of exclusion processes as basic information about the virus and its spread is shared with the public. We conduct a rapid virtual audit of pandemic related press briefings and press conferences issued by governments and international organizations in order to assess if responses have been inclusive to the hearing-impaired communities in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). We analyze COVID-19 press conferences and press briefings issued during Feb–May 2020, for over 123 LMICs and for international organizations (e.g. the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the World Health Organization (WHO)). Our virtual audit shows that only 65% of countries have a sign language interpreter (SLI) present in COVID-19 press briefings and conferences. This number is smaller in low-income countries (41%) and Sub-Saharan African countries (54%). Surprisingly, none of the international organizations including the WHO has a SLI present during COVID-19 press briefings. We recommend all countries and international organizations to reconsider ways to make press conferences accessible to a wide audience in general, and to the hearing impaired communities in particular by including a SLI during their COVID-19 briefings, a primary step towards upholding the sustainable development pledge of “no one gets left behind.”

Keywords: Disability, Audit, Information, Press briefings, COVID-19

1. Introduction

The novel coronavirus pandemic poses unique challenges for people with disabilities as this ongoing crisis heightens barriers to information, resources, and care. In particular, Deaf communities are uniquely impacted by lack of access to information regarding safety measures, such as hand washing, social distancing, facemask adherence, and lockdowns, enhancing their exposure to, and management of, embodied risk and vulnerability. These concerns are further exacerbated in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) where more than one in seven adults have some form of disability (World Health Organization (WHO) and World Bank, 2011, Mitra and Sambamoorthi, 2014).

There are several instruments that protect people with disabilities in situations of disaster and ensure information equity. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, ratified by 181 countries, carries specific protection for people with disabilities during humanitarian emergencies (Article 11) and for equal access to information (Article 21). However, it remains to be seen whether they are being upheld in the current moment. Our objective here is to conduct a preliminary investigation of informational access for people with hearing disabilities in LMICs during the COVID-19 health emergency. We provide urgent evidence on information barriers experienced by people with hearing disabilities, offering important recommendations on how information and communication systems can be made more accessible in the moment of disaster. By understanding how current processes of exclusion are unfolding, we can try to prevent collective suffering during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond.

We conducted a rapid virtual audit of pandemic-related press briefings and press conferences issued by governments in LMICs and international organizations to examine if pandemic-related information dissemination has been inclusive to the hearing-impaired communities. We examine government-issued publicly available press conferences and press briefings pertaining to COVID-19 in 123 LMICs as well as those issued by international organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO), the World Bank (WB), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the International Labor Organization (ILO).

We have two very important and striking results. First, only 65% of the LMICs have a sign language interpreter (SLI) in their COVID-19 press briefings and conferences, with less than 50% in Sub-Saharan African countries. Second, none of the international organizations, including the WHO, has a SLI present during COVID-19 press briefings. Hence, we recommend all countries and international organizations to include a SLI during COVID-19 press conferences and briefings, a low hanging fruit, which enables them to uphold the sustainable development pledge of “no one gets left behind.”

2. Data and methods

To conduct a rapid virtual audit of electronic content, similar to in-person audits conducted for monitoring teacher absenteeism in education in India (Muralidharan, Das, Holla, & Mohpal, 2017), we assess the format of press briefings for accessibility by the Deaf community. We examine government press conferences and press briefings for COVID-19 issued during February 28 to May 26, 2020, as the pandemic spread from Wuhan, China to other countries in Asia and Europe and essentially around the globe. These conferences and briefings were conducted by one of the following: head of state, head of government, and the health minister in all LMICs. This includes public health briefings, government measures implemented to contain the spread of the virus, as well as announcements regarding financial and economic measures related to the COVID-19 outbreak.1 In addition, we also consider interviews of government representatives by news outlets as a channel for information dissemination.2 Since nearly 90 percent of the populations with hearing disabilities live in LMICs (World Health Organization (WHO), 2018), which also tend to have fewer resources, we largely focus our analysis on LMICs

Our analysis on publicly available press conferences and press briefings pertaining to COVID-19 covers those that are posted on countries’ government websites, news media websites and widely used social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube.3 Governments and news outlets, along with using traditional avenues of communication such as radio and television broadcasts, have begun to utilize social media as an alternative channel for information dissemination as more people, both old and young, have been using social media in recent years (Bishop, Poushter, & Chwe, 2018).

In addition, we also examine COVID-19 press conferences and press briefings of large international organizations available on their websites. These organizations include the WHO, the World Bank, the IMF, the FAO, and the ILO.

We curate the full list of video content available and then carefully review each one to create a metric on accessibility where accessibility means the presence of a SLI, who is either physically present with the speaker or through an insert of the interpreter on the video. This study focuses on whether briefings were inclusive towards those who have severe hearing disabilities from February 28 to May 26, 2020, during the beginning of the pandemic outbreak in much of the world. Note that we are not able to examine how often the SLI were present in the series of press briefings in each country.

3. Results

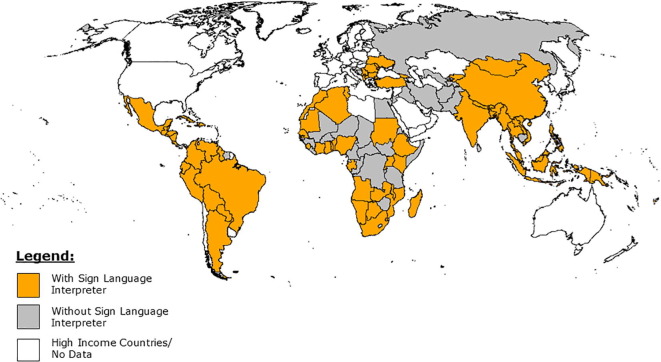

We analyzed COVID-19 press conferences and press briefings for over 123 out of 138 LMICs, or 28 low-income countries and 95 middle-income countries (Yap et al., 2020). Fig. 1 shows that only 79 of 123 countries, that is, only 64% of the LMICs had a SLI available during COVID-19 press conference and briefings.4

Fig. 1.

Presence of Sign Language Interpreters in COVID-19 Issued Press Briefings and Conferences in LMICs.

Table 1, Table 2 show disaggregated results by income classification and geographical region, respectively. As shown in Table 1, we find that 43% of low-income countries provide SLIs. The numbers are better for both lower and upper middle-income countries at 70%. In Table 2, we present disaggregated results by region. A majority of countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (88%), Europe and Central Asia (71%), and East Asia and Pacific (72%) make their COVID-19 press conferences and briefings to include a SLI. This rate is lower in Sub-Saharan Africa (54%), South Asia (50%), and Middle East & North Africa (33%)5 .

Table 1.

Distribution of sign language interpreters in COVID-19 press conferences and briefings by income classification.

| Income Classification | Number of Countries | Sign Language Interpreter present (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Low Income | 28 | 43% |

| Lower Middle Income | 44 | 70% |

| Upper Middle Income | 51 | 71% |

| Total | 123 | 64% |

Table 2.

Distribution of sign language interpreters in COVID-19 press conferences and briefings by geographical region.

| Region | Number of Countries | Sign Language Interpreter present (%) |

|---|---|---|

| East Asia & Pacific | 18 | 72% |

| Europe & Central Asia | 17 | 71% |

| Latin America & Caribbean | 25 | 88% |

| Middle East & North Africa | 9 | 33% |

| South Asia | 8 | 50% |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 46 | 54% |

| Total | 123 | 64% |

Next, we examine if the policy response to COVID-19 made by international organizations are inclusive or not. We examine COVID-19 press conferences and press briefings of large international organizations available on their websites including the WHO, the World Bank, the IMF, the FAO, and the ILO. We did not find SLIs in any of these publicly available press conferences and briefings.

4. Discussion and conclusion

We present findings from a rapid virtual audit of pandemic related press briefings and press conferences issued by governments and international organizations as to whether they have been inclusive to the hearing-impaired communities in LMICs. Our virtual audit of content issued by 123 LMICs and five major international organizations including the WHO, the World Bank and the IMF shows that only 65% of countries and that none of the international organizations including the WHO has a SLI present during COVID-19 press briefings and conferences. The World Federation of the Deaf (WFD) and the International Disability Alliance (IDA) have reached out to the WHO and the United Nations to ensure that their information is accessible to all (World Federation of the Deaf, 2020a, World Federation of the Deaf, 2020b). This oversight in making public health information “accessible to all” during the pandemic not only impacts persons with disabilities but also others by undermining the efforts to “flatten the curve” because COVID-19 can be spread even by asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic persons (Hoehl et al., 2020, Wei et al., 2020).

This analysis has several caveats. First, it is limited to copies of press conferences made available online on websites and social media platform. It is possible that press conferences were available on TV but not on the web. Second, we have only examined access to pandemic response as measured by the presence of SLIs without examining the quality of sign language interpretation available to people with disability. Finally, we have also not examined access to and quality of closed captioning that is made available to Deaf communities.

Nevertheless, this analysis provides an important insight regarding the accessibility of crises responses and contributes to the growing literature on disability-inclusive development and humanitarian responses (United Nations, 2019a, United Nations, 2019b, Oosterhoff and Kett, 2014). We recommend all countries and international organizations to include a SLI during press conferences and press briefings in general and related to COVID-19 in particular, to uphold the sustainable development pledge of “no one gets left behind.” This is a necessary first step that most countries and certainly international organizations can or should do. Our results also show that there is much work yet to be done for the United Nations to operationalize its recent disability inclusion strategy (United Nations, 2019a, United Nations, 2019b) and for countries to implement Articles 11 and 21 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities on humanitarian relief and information access. Lagging behind on putting policies into practice is likely to make the pandemic reinforce existing inequalities.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no relevant or material financial interests that relate to the research described in this paper.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to Samuel Blohowiak for excellent research assistance.

Footnotes

We examined several COVID-19-related press briefings for each country and as long as at least one of them (per country) had a SLI during the range of the dates mentioned above, we counted the country to have a SLI present. This effectively presents lower bound estimates on the presence of SLIs in LMICs.

The study does not include information campaign materials such as posters, information videos, and music videos.

For a subset of our sample (17 countries), we validated our sources with those available at the World Federation of the Deaf (World Federation of the Deaf, 2020a, World Federation of the Deaf, 2020b).

There is a small possibility that we could not find videos with sign language interpreter for a country when it exists. We are making the raw and processed data used in Fig. 1 and Table 1, Table 2 available at Mendeley data (https://doi.org/10.17632/7v6rzdst99.5).

It should be noted that more research needs to be conducted for Pacific Island countries and Middle Eastern countries as language proved to be a challenge.

References

- Bishop C., Poushter J., Chwe H. Pew Research Center; 2018. Social media use continues to rise in developing countries, but plateaus across developed ones. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2018/06/19/social-media-use-continues-to-rise-in-developing-countries-but-plateaus-across-developed-ones/ [Google Scholar]

- Hoehl S., Rabenau H., Berger A., Kortenbusch M., Cinatl J., Bojkova D.…Ciesek S. Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in returning travelers from Wuhan, China. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382(13):1278–1280. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra S., Sambamoorthi U. Disability prevalence among adults: Estimates for 54 countries and progress toward a global estimate. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2014;36(11):940–947. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2013.825333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muralidharan K., Das J., Holla A., Mohpal A. The fiscal cost of weak governance: Evidence from teacher absence in India. Journal of Public Economics. 2017;145:116–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosterhoff P., Kett M. IDS; Brighton: 2014. Including people with disabilities in emergency relief efforts, IDS rapid response briefing 8. https://www.ids.ac.uk/publications/including-people-with-disabilities-in-emergency-relief-efforts/ [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . United Nations; 2019. Disability and development report 2019. https://social.un.org/publications/UN-Flagship-Report-Disability-Final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (2019). United Nations disability inclusion strategy. https://www.un.org/en/content/disabilitystrategy/#:~:text=A%20STRATEGY%20FOR%20ACTION,inclusion%20of%20persons%20with%20disabilities.

- Wei W.E., Li Z., Chiew C.J., Yong S.E., Toh M.P., Lee V.J. Presymptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2—Singapore, January 23–March 16, 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2020;69(14):411–415. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6914e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Federation of the Deaf (2020). Examples of press conferences on COVID-19 with interpretation into national sign language. April 01 http://wfdeaf.org/news/resources/wfd-press-conferences-on-covid-19/.

- World Federation of the Deaf (2020). COVID-19 Access Now!. May 02 World Federation of the Deaf. http://wfdeaf.org/news/covid-19accessnow/.

- World Health Organization (2018). WHO global estimates on prevalence of hearing loss. https://www.who.int/deafness/Global-estimates-on-prevalence-of-hearing-loss-Jul2018.pptx?ua=1 (retrieved on July 18, 2020).

- World Health Organization (WHO) & World Bank (2011). World report on disability. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/report.pdf.

- Yap J., Chaudhry V., Jha C.K., Mani S., Mitra S. Are responses to the pandemic inclusive? A rapid virtual audit of COVID-19 press briefings in LMICs. Mendeley Data. 2020;V5 doi: 10.17632/7v6rzdst99.5. http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/7v6rzdst99.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]