Abstract

Diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) place a significant burden on health care systems in the world and its aging populations. These diseases have long been regarded as separate entities; however, advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and the receptors for AGEs (RAGE) may be a link between diabetes and AD. In our study, mice injected with AGEs through stereotaxic surgery showed significant AD-like features: behavior showed decreased memory; immunofluorescence showed increased phosphorylated tau and APP. These results suggest links between diabetes and AD. Patients with diabetes are at a higher risk of developing AD, and the possible underlying molecular components of this association are now beginning to emerge.

Keywords: advanced glycation end products, RAGE, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, PI3K

Introduction

Accumulated evidence suggests that sporadic cases account for more than 95% of the total cases of Alzheimer’s disease (AD; Levin, 2019). AD is a neurodegenerative disease with progressive memory cognitive dysfunction as the main clinical manifestation. The hallmark lesions observed in the brain of patients with AD result from the formation of numerous neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) and senile plaques (SPs) composed of hyperphosphorylated tau and Aβ, respectively (Lane et al., 2018). Studies have implicated diabetes mellitus (DM) as a strong risk factor for the development of AD (Jayaraj et al., 2020). DM shares pathological features with AD, such as impaired insulin signaling, increased oxidative stress, increased amyloid-beta (Aβ) production, tauopathy, and cerebrovascular complications (Shinohara and Sato, 2017), and therefore appears to be closely related to AD.

Glycosylation is an important non-enzymatic reaction between reducing sugars and amines (Singh et al., 2018). Lysine or arginine residues of proteins and glucose, moving towards the Schiff-base, convert themselves to the more stable aminomethyl ketone by the Amadori rearrangement and finally result in the formation of advanced glycation end (AGE) products (Bunn and Higgins, 1981; Hartog et al., 2007; Rabbani and Ahn, 2019). The synthesis of AGEs is irreversible, and although the process of cell death is slow and insignificant, the non-enzymatic saccharification process accompanied by neuron metabolism seriously affects the normal functioning of the nervous system (Kamynina et al., 2018). Therefore, AGEs and the receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE) may play an important role in disease pathogenesis. Many studies have shown that the accumulation of AGEs is a major factor in the incidence and development of several diabetic complications and neuropathies (Hammes et al., 1999; Negre-Salvayre et al., 2009; Singh et al., 2014; Nowotny et al., 2015; Yamagishi et al., 2015; Hashimoto et al., 2016; Kumar Pasupulati et al., 2016), and the accumulation of AGEs under in vivo conditions is associated with secondary complications related to diabetes in hyperglycemic environments (Garay-Sevilla et al., 2005). Furthermore, AGEs are closely linked to amyloid-based neurodegenerative diseases (Vicente Miranda and Outeiro, 2010; Li et al., 2012; Simó et al., 2017). Salahuddin et al. (2014) showed that disrupting the AGE-RAGE interaction can effectively prevent the development of AD, and AGEs are therefore considered promising drug targets for AD. Studies also show that the formation of AGEs will pass through and interfered with H1, H2A, and H3 histones by causing structural changes. The normal functioning of serotonin affects chromatin structure and function, leading to secondary complications which in turn aggravates the diabetic condition (Ashraf et al., 2014, 2015a,b). The above evidence reveals that AGEs have a role in both diabetes and AD in humans as well as in disease models.

Studies also have found that AGEs induce oxidative stress in neurons, promoting the release of neuroinflammatory cytokines and Aβ (Yan et al., 1996; Baig et al., 2018). At the same time, extracellular AGEs can also affect neuronal function through RAGE. Studies have shown that RAGE also interacts with and mediates the cytotoxicity of Aβ (Wang et al., 2018). For example, the combination of RAGE and Aβ can activate the inflammatory signaling pathway, release ROS to produce oxidative stress, and cause neuroinflammation, cause mitochondrial and neuronal dysfunction (Deane et al., 2008), and affect the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway (Deane, 2012). RAGE also accelerates the absorption and transport of Aβ, which causes Aβ to pass through the blood-brain barrier and into the central nervous system by endocytosis (Deane et al., 2003), causing cerebrovascular dysfunction and eventually leading to neurovascular inflammation and subsequent increase in synaptic toxicity (Deane and Zlokovic, 2007), which in turn affects the normal functioning of the central nervous system (Zhang et al., 2011; Galasko et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014; Cai et al., 2016; Fang et al., 2018). The elevated expression of RAGE activates the nuclear transcription factor NF-κB, resulting in a positive feedback effect on inflammation (Wan et al., 2015; Fang et al., 2018). Aβ activation of RAGE increases the expression of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, interleukin-6, and macrophage colony-stimulating factor (Dukic-Stefanovic et al., 2003), which accelerates the occurrence and development of AD. The RAGE signaling pathway also plays an important role in AGE-induced tau phosphorylation and spatial memory impairment. In SK-N-SH cells, primary hippocampal neurons, and rats, AGEs induce tau hyperphosphorylation via the RAGE/GSK-3 pathway (Li et al., 2012; Son et al., 2012). AGEs also block the BDNF-TrkB signaling pathway in rat brain and N2A cells (Li et al., 2012), activate the GSK-3β kinase at Ser9, phosphorylate GSK-3, and induce tau hyperphosphorylation (Wu et al., 2019). Also, the deposition of AGEs activates microglia and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase, resulting in the release of ROS and the formation of peroxynitrite, which oxidizes proteins, lipids, and DNA (Nam et al., 2012), eventually causing neuronal death. Co-immunoprecipitation studies have found that almost all AGE-immunoreactive neurons contain phosphorylated tau protein (Qi et al., 2017), which indicates that AGEs play an important role in tau protein hyperphosphorylation. As compared to AD mice, the phosphorylation levels of tau were increased in the offspring mouse model of diabetes and AD hybridization (Pdx1+/–/APP/PS1); furthermore, the production of Aβ was increased and the clearance of Aβ was inhibited (Guo et al., 2016). More and more evidence shows that DM is also a causative factor of AD; therefore, AD is also called type III diabetes (Luchsinger et al., 2001; Huang et al., 2014; Ahmed et al., 2015; Sridhar et al., 2015). As the RAGE signaling pathway may be an important therapeutic target in AD, computer-aided drug design has especially emerged as an efficient means of developing candidate drugs for the treatment of AD. The above observations suggest that the signal pathways mediated by AGEs/RAGE are implicated in AD-like learning and memory impairment, trigger neuroinflammation, and promote Aβ deposition and tau hyperphosphorylation.

Immunohistochemical evidence also suggests that AGEs were co-located with NFTs and SPs, indicating that AGEs can induce AD symptoms (Takeda et al., 2011). AGEs are prooxidant factors that induce oxidative stress, causing neuronal dysfunction or death. It has been reported that GSK-3β is a potential link between diabetes and AD; the excessive activation of GSK-3β can cause hyperphosphorylation of tau (Zhang et al., 2018). LiCl is an inhibitor of GSK-3 (Kurgan et al., 2019), which has been reported to alleviate the hyperphosphorylation of tau proteins caused by AGEs to a certain extent. While AGEs may play an important role in the development of AD, the mechanism remains unclear.

In hyperglycemia and diabetes, the body produces large amounts of AGEs, which accelerate and aggravate the symptoms of diabetes and its complications, such as AD (Simó et al., 2017). AGEs are elevated in AD brains where they stimulate Aβ production and colocalize with NFTs and SPs, suggesting that AGEs play an important role in the pathogenesis of AD (Cai et al., 2016). Studies have found that diabetes can aggravate the decline of tau protein lesions and spatial learning memory in the AD model. Due to advances in clinical treatment, the lifespan of diabetic patients can be further extended, with a higher global incidence of diabetes-associated AD (Ahmed et al., 2015).

AGEs play a central role in the development of AD and link neurodegenerative disease and diabetes. The stage during which AGEs impact AD and how AGEs influence tau proteins and Aβ are still unclear. The effects of increased AGEs on spatial learning and memory, as well as the effects of early inhibition of AGEs production on the behavior and pathophysiology of the AD model, have not yet been reported. Therefore, elucidating the mechanism of AGEs is important to show the association between diabetes and AD.

In previous studies, the main focus was on the mechanism of AGE-RAGE signaling in neurodegenerative diseases (Juranek et al., 2015; Batkulwar et al., 2018). The purpose of our research is to study the common target (RAGE) between diabetes and AD, and then establish the links between diabetes and AD to RAGE, and further carry out the related mechanism research. We not only studied the mechanism of RAGE in AD, but it’s also more important to link diabetes to AD through RAGE.

To explore the role of AGEs in AD and diabetes, we injected AGEs in mice and found that they showed obvious symptoms of AD; behavioral studies showed that memory was impaired, immunofluorescence and western blot showed increased APP and p-Tau levels, and PET and qPCR confirmed this increase in Aβ and Tau levels. Immunofluorescence revealed elevated RAGE, Tau, and APP levels in ZDF rats as well. Therefore, through these experiments, we demonstrated that AGEs-RAGE may be a potential link between AD and diabetes.

Materials and Methods

Animals

C57BL/6 mice and ZDF rats were housed in specific pathogen-free (SPF) rooms with a 12-h light-dark cycle and sufficient water and food. All animal handling protocols were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Fudan University (No. 20171732A680).

Morris Water Maze

Three days before the experiment, we placed the mouse into the behavioral room to adapt to the environment. A water tank measuring 122 cm in diameter was placed into the water labyrinth and instrument collection area. The tank was filled with water and bleaching powder to make the water turbid. The camera software that measured water maze behavior was adjusted for clarity, light, and brightness using a graphic mark placed approximately 0.1 m from the bottom of the tank. On the first day, a platform was placed above the surface in a single position in the water tank. The mouse was released into the water from the east, west, south, and north directions, and the time until the mouse found the underwater platform and climbed onto it was recorded. On days 2–5, the platform was placed 1 cm below the level of the liquid. Similar to day 1, the mouse was placed in the water from four different orientations. The time until the mouse found the platform hidden under the water and climbed onto it was recorded. If the mouse did not locate the platform within 60 s, the time was recorded as 60 s. On day 6, the platform was removed and the mice were allowed to move freely in the tank for 10 min. The time spent in each quadrant was determined, with a focus on the time the mouse was in the quadrant where the platform was previously located, each quadrant was marked by a different shape on the wall.

Y-Maze

The mice were placed in a behavioral room to adapt to the environment 3 days before the experiment. Different geometric figures were attached to the three arms of the Y-maze as visual markers. The three arms of each Y-maze were randomly divided into new arms, starting arms, and other arms. The Y-maze device was placed in the behavioral camera capture area to adjust for camera clarity, light brightness, and to set up the software. Blocking the new arm, the starting arm and the other arm were opened, allowing the mice to explore for 5 min. Subsequently, all three arms were opened and the mice were allowed to explore freely for 5 min; the time the mice spent exploring the new arm was recorded.

Open Field

The mice were placed in a behavioral room to adapt to the environment 3 days before the experiment. A 120-cm long and wide-field camera equipment was set up in the behavioral acquisition area to adjust the camera sharpness, brightness, and set up the software. The mice were placed in the open field and allowed to move freely for 10 min. The time the mice spent in the central and surrounding areas was recorded.

Protein Extraction

The mice were anesthetized with 2% sodium pentobarbital, and the mouse brain was quickly excised and placed in ice-cold PBS. The mouse hippocampus was isolated in frozen PBS. The hippocampus was placed in a tissue lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors. The tissue was lysed by thorough grinding on ice, was kept on ice for 2 h, and then 500 μg of the hippocampal slurry was centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min. The supernatant was transferred to a new sterile 1.5-ml Eppendorf tube.

The sample was centrifuged again at 13,000 g for 20 min under the same conditions. The supernatant was aspirated into a new sterilized EP tube. Each sample received 5× SDS buffer mixed with β-mercaptoethanol and was heated at 99°C for 15 min, immediately followed by a 3 min incubation on ice. The samples were then centrifuged for 3 min and used immediately or stored at −80°C until use.

Western Blot Analysis

The percent SDS PAGE gels were determined according to the molecular weight of the target protein with a 5% separating gel. Protein ladder (1 μl) and protein samples (10 μl) were loaded onto the gel, and the gels were run at 80 V/30 min or 120 V/1.5 h. Afterward, the samples were transferred to a membrane by wet transfer. After the transfer, the membrane was blocked with 5% BSA (diluted in PBS) for 1 h, followed by incubation with the primary antibody (diluted in PBS) overnight at 4°C. The primary antibody was then aspirated off the membrane, which was washed five times with PBST for 5 min. The membrane was incubated with the fluorescent secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was then washed three times with PBST for 5 min each and then scanned with the Odessey system (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA).

Immunohistochemistry

The brain tissue of the mice treated with AGEs, BSA, and AGEs+LiCl was taken from the 80°C freezer, rinsed three times with 1× PBS for 5 min each time, and incubated in PBS+0.1% TritonX-100 for 30 min at room temperature to permeate the cell membrane. The sections were then rinsed three times with 1× PBS for 5 min before adding 5% BSA-PBS for 2 h at room temperature to block non-specific binding. The blocking solution was then aspirated, and the primary antibody diluted in 1% BSA-PBS was added [APP (1:1,000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), or P-TAU (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA)] to the sections, which were incubated at 4°C overnight. The following day, the sections were washed threee times in 1× PBS for 5 min each. A fluorescent secondary antibody (1:500) diluted in 1× PBS was added in the dark and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The secondary antibody was removed, and DAPI (1:1,000) diluted in 1× PBS was added to the sections for 5 min at room temperature. The DAPI was discarded, and the sections were washed three times in 1× PBS for 5 min each. The slides were photographed using a confocal microscope.

RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription and Real-Time Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

The hippocampus of the mice treated with AGEs, BSA, and AGEs + LiCl was extracted. Total RNA was extracted using Promega’s total RNA extraction kit following the manufacturer guidelines. The concentration of RNA was determined by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm, and 2 μg of RNA was used for first-strand cDNA synthesis using Takara’s reverse transcription kit. The mixture of cDNA samples and the indicated primers (Table 1) was subjected to at least three replicate qPCR amplification using YEASEN’s SYBR Green qPCR mix. Relative gene expression was calculated by comparing the CT value of the gene of interest with the CT value of the internal reference gene GAPDH.

Table 1.

List of the primers used for qPCR.

| Gene | Primer Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

| Tau | Forward Primer: TGGGGAACATTCCGTATGAGG |

| Reverse Primer: CAGAAGCCATAACCCTTGGG | |

| APP | Forward Primer: AACCGACTCCAGGATGACTATG |

| Reverse Primer: TCTGGGGTTCCATGTAAAAGC | |

| GAPDH | Forward Primer: TGGATTTGGACGCATTGGTC |

| Reverse Primer: TTTGCACTGGTACGTGTTGAT |

The qPCR primer sequences of the human genes (APP, TAU, GAPDH) required for the experiment were found in the Primer Bank, as shown in Table 1.

Immunofluorescence

Rat brain slices were washed three times with 1× PBS for 5 min each, treated with 0.2% Triton-X100 (diluted in PBS) for 30 min, and then blocked with 5% BSA for 1 h. Next, the sections were incubated with RAGE, tau, and APP primary antibodies (diluted in PBS) at 4°C overnight. The following day, the sections were washed three times with 1× PBS for 5 min each and then incubated with secondary antibodies for 1.5 h. Finally, DAPI was incubated for 10 min. After washing with PBS, the plate was mounted with a fluorescent mounting plate. The expression of RAGE, tau, and APP was observed on confocal microscopy.

Results

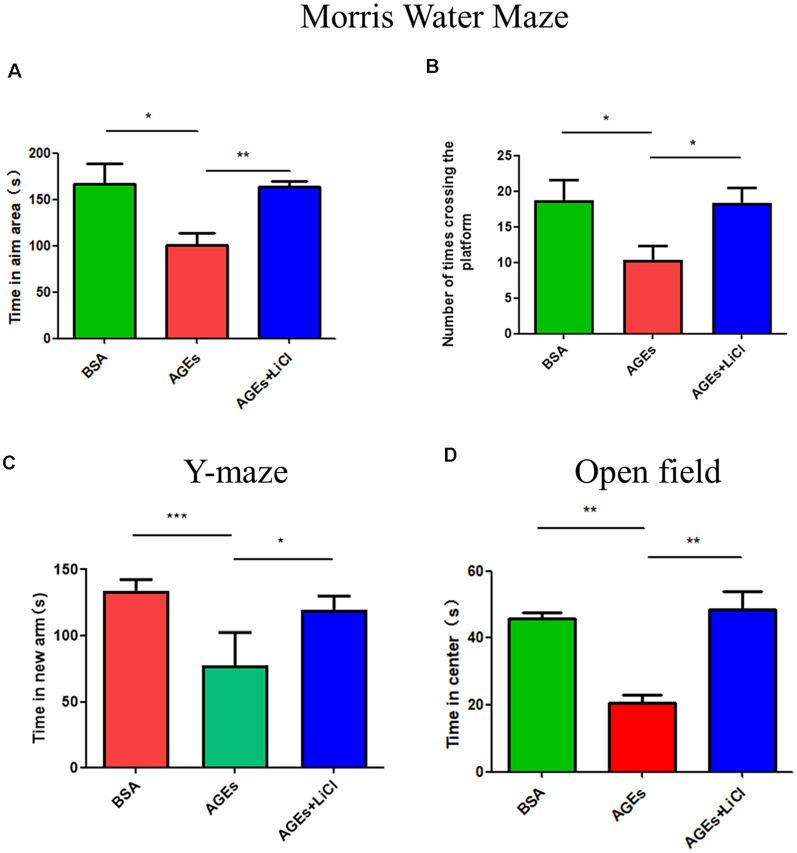

Behavioral Experiments Reveal Abnormal Behavior in AGE-Treated Mice

To investigate whether behavior changes develop in mice after the injection of AGEs, we studied the behavior of mice using the Morris Water Maze, Y-maze, and open field experiments. In the water maze test, compared with the control group, the AGE mice stayed in the target area for significantly lesser time, indicating that AGEs impair memory in mice. However, when treated with LiCl, the time spent in the target area significantly increased compared to that of AGE mice, indicating that LiCl can mitigate memory impairment (Figure 1A). Similarly, the number of times AGE mice crossed the platform decreased compared with that of the control group; however, when AGE mice were treated with LiCl, the number of times the mouse crossed the platform significantly increased compared to that of AGE mice (Figure 1B). This indicated that AGEs impair the memory of mice, while LiCl can alleviate the damage of AGEs.

Figure 1.

Mice injected with advanced glycation end products (AGEs) show dementia-like behavior. (A,B) Water maze experiment was performed on three groups of mice to observe the dementia-like behavior. (A) The time that the three groups of mice stayed in the target area was measured. (B) The number of times the three groups of mice crossed the platform. The criterion for judging the entry of the mouse into the target area was the entry point of the mouse torso center point. (C) Y-maze experiment measured the residence time of three groups of mice injected with BSA, AGEs, AGEs + LiCl in the brain in the new arm of the Y-maze. (D) Open-field experiment measured the length of stay of the three groups of mice in the central area time. For each group of mice, n = 5. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Y-maze is an effective way to assess short-term memory in mice (Kraeuter et al., 2019). In the Y-maze experiment, compared with the control group, AGE mice stayed in the new arm for significantly lesser time. However, treatment with LiCl increased the time spent in the new arm, indicating that AGEs damage the memory capacity of mice, while LiCl can alleviate the damage of AGEs (Figure 1C). In the open field experiment, compared with the control group, AGE mice stayed in the central area for a significantly shorter time. When AGE mice were treated with LiCl, however, the time spent in the central area significantly increased. This indicated that AGEs increased the anxiety behavior of mice, while the addition of LiCl eased the anxiety behavior (Figure 1D).

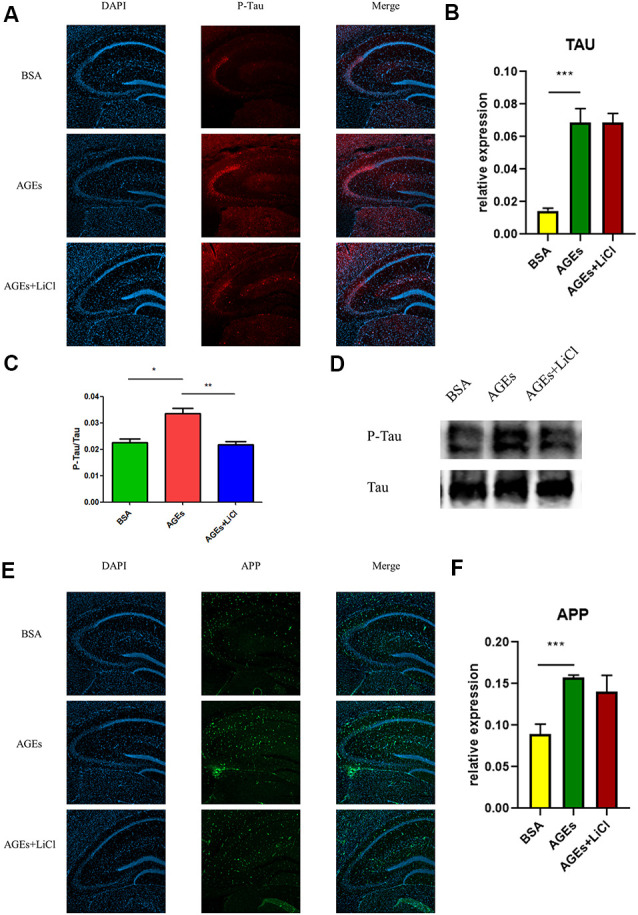

P-tau and APP Increased in the Hippocampus of AGE Mice

To investigate whether mice injected with AGEs develop AD symptoms, we analyzed the expression of P-tau (Phospho-Tau-S356 Rabbit pAb) and APP in the hippocampus of the mice by immunofluorescence, Western blot, and qPCR. The results showed that compared with the BSA control group, the expression of P-tau was significantly up-regulated in AGE mice, while it was not significantly changed in AGE mice treated with LiCl (Figure 2A). Compared with the control group, the mRNA expression of tau was significantly up-regulated in AGE mice, while it was not significantly changed in AGE mice treated with LiCl (Figure 2B). The same results were verified by immunoblotting (Figures 2C,D). Compared with the BSA control group, in AGE mice, the expression of APP protein was significantly up-regulated, while it was not changed in AGE mice treated with LiCl (Figure 2E). At the mRNA level, compared with the control group, the mRNA expression of APP in the AGE mice was significantly up-regulated, with no effect of LiCl (Figure 2F). This indicated that, compared with the control, the AGE mice successfully developed AD symptoms, which were mitigated when treated with LiCl.

Figure 2.

Upregulation of Alzheimer’s disease (AD)-related protein expression in advanced glycation end (AGE)-injected mice. (A–C) Expression of P-tau in the hippocampus of BSA, AGEs, AGEs + LiCl treated mice. (A) P-tau in the hippocampus of three groups of mice was stained with immunofluorescence (red), and nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). (B) qPCR was performed on the hippocampus of the three groups of mice, and the expression of tau-related proteins was measured. The expression level was normalized to the average expression level in the BSA injection group; (C,D) Western blotting was performed on the hippocampus of the three groups of mice, and the ratio of the expression levels of P-tau to tau protein in the three groups of mice was calculated and expressed as P -tau/tau value. The gray density was normalized to the average gray density of the tau protein. (E,F) APP protein expression in the hippocampus of three groups of mice. (E) APP proteins in the hippocampus of the three groups of mice were stained with immunofluorescence (green), and the nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). (F) qPCR was performed on the hippocampus of three groups of mice to measure the expression of APP-related proteins in the hippocampus. The expression level was normalized to the average expression level of the injected BSA group. For each group of mice, n = 3. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. One-way ANOVA. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

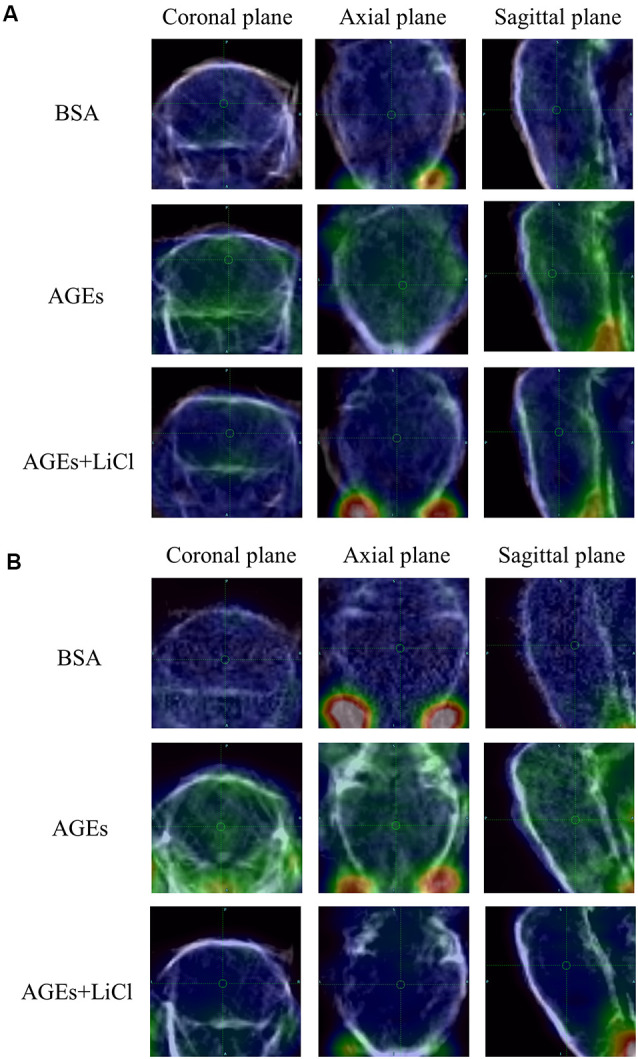

At the same time, the increase in tau and Aβ in living mice was further verified by PET (Figures 3A,B). AV45 and PBB3 injections, respectively, showed that tau and Aβ in AGE mice increased significantly, but were relieved when treating with LiCl. This result further demonstrates that AGEs can promote the occurrence of AD symptoms.

Figure 3.

AGE mouse PET image. (A) Mice injected with 18F-AV45. Green represents Aβ. (B) Mice injected with 18F-PBB3. Green represents tau.

AGEs Increase Tau Phosphorylation via the PI3K Signaling Pathway

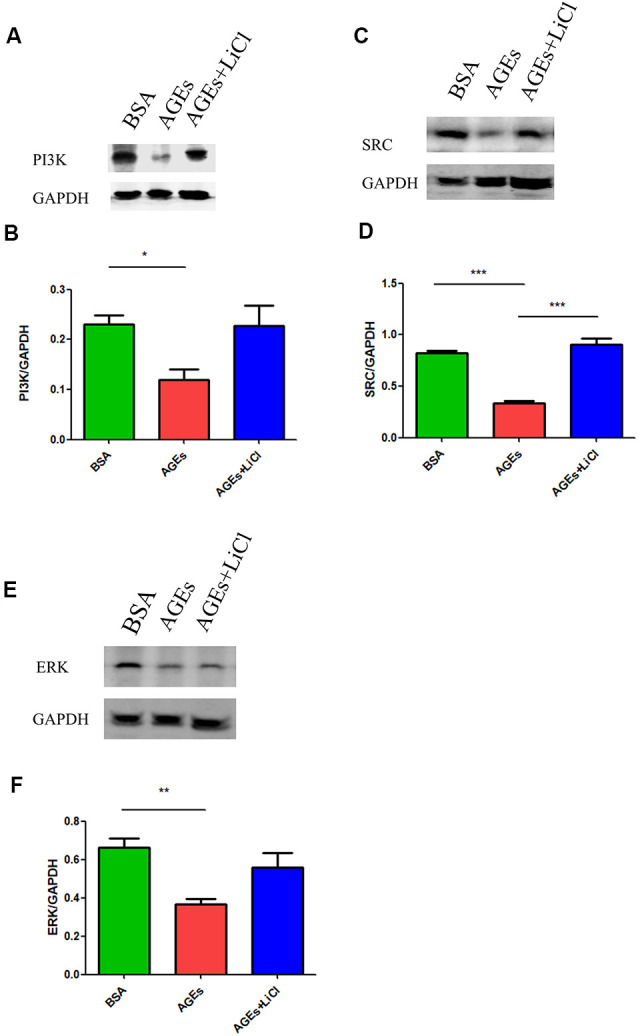

Many studies have shown that increased phosphorylation of tau is closely related to the PI3K signaling pathway (Wang et al., 2018, 2019; Wei et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2019). Activation of the PI3K signaling pathway can reduce the over-phosphorylation of tau (Xiong et al., 2020). Therefore, we speculated whether AGEs cause increased tau phosphorylation by affecting the PI3K signaling pathway. To verify our conjecture, we detected the changes in the expression of PI3K protein and its downstream SRC and ERK proteins in the hippocampus of AGE and AGE+LiCl mice. Compared with controls, AGEs significantly down-regulated the protein expression of PI3K in the hippocampus of mice. However, this was up-regulated again after treatment with LiCl, indicating that AGEs may affect the memory of mice through the PI3K signaling pathway and LiCl may alleviate the damage of AGEs to brain function to some extent (Figures 4A,B). Moreover, the protein expression of SRC in the hippocampus of AGE mice was significantly down-regulated, while it was significantly up-regulated again when treated with LiCl, indicating that the down-regulation of PI3K resulted in a decrease in SRC (Figures 4C,D). Furthermore, the expression of ERK protein in the hippocampus of AGE mice was significantly decreased. LiCl, however, had no significant effect on the expression of ERK. There was an upward trend of ERK, indicating that AGEs ultimately lead to a decrease in ERK protein through the PI3K signaling pathway, which may be the main signaling pathway leading to phosphorylation of tau protein, and the addition of LiCl can effectively inhibit the action of AGEs (Figures 4E,F).

Figure 4.

The upregulation of AGEs inhibits the PI3K/SRC/ERK signaling pathway. (A,B) Western blotting detection of PI3K protein in the hippocampus of three groups of mice, normalized gray density to the average gray density of GAPDH. (C,D) Western blotting detection of SRC protein in the hippocampus of three groups of mice. Gray density was normalized to the average gray density of GAPDH. (E,F) Western blotting was performed on ERK proteins in the hippocampus of the three groups of mice, and the gray density was normalized to the average gray density of GAPDH. For each group of mice, n = 3. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. One-way ANOVA. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

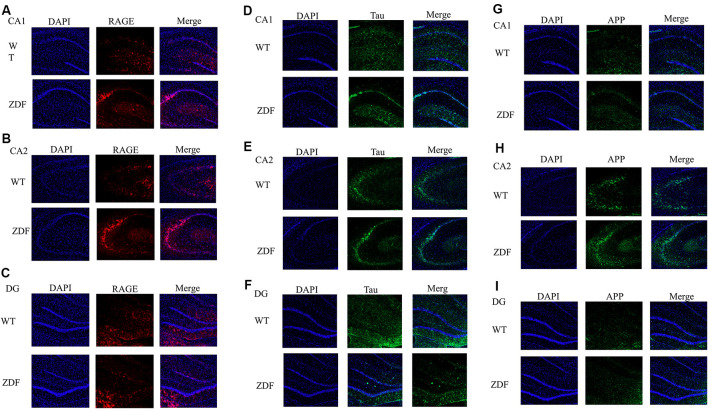

ZDF Rats Show Increased RAGE, APP, and Tau

To further verify the changes of RAGE in diabetes, we investigated whether there is a link between diabetes and AD by detecting changes in APP and tau in ZDF rats. Using immunofluorescence, we found that compared with normal wild rats, RAGE expression in the CA2–CA3 region significantly increased and was aggregated (Figures 5A,B). RAGE expression in the CA1 and DG regions was similar (Figure 5C). When comparing the expression of tau protein, we found that tau expression in wild SD rats was evenly distributed in the hippocampus, while tau expression in ZDF rats showed an aggregated state (Figures 5D–F). Similarly, we found that APP showed a clear upward regulation in the hippocampus of ZDF rats (Figures 5G–I). These results indicate that RAGE expression is up-regulated in diabetic rats and that AD-like symptoms (increased tau aggregation and APP expression) occur in the hippocampus of diabetic rats, confirming that there is indeed an association between diabetes and AD.

Figure 5.

ZDF rats show AD symptoms. (A–C) Staining rat hippocampus with RAGE antibody (red) and the nuclei with DAPI (blue). (D–F) Staining rat hippocampus with tau antibody (green) and the nuclei with DAPI (blue). (G–I) Staining rat hippocampus with APP antibody (green) and the nuclei with DAPI (blue).

Discussion

This study investigated the association between diabetes and AD through the treatment of mice with AGEs. First, memory dysfunction in AGE mice was verified by behavior (Figure 1). Next, immunofluorescence, qPCR, and Western blotting confirmed an increase in P-tau and APP in the hippocampus of AGE mice (Figures 2, 3). We then speculated that AGEs may cause tau protein hyperphosphorylation through the PI3K signaling pathway (Figure 4). At the same time, LiCl improved these symptoms caused by AGEs. Finally, it was confirmed by immunofluorescence experiments in ZDF rats that diabetic rats develop AD symptoms (Figure 5). Therefore, our data illustrate the close relationship between diabetes and AD.

When diabetic patients are in a state of hyperglycemia for a long time, glucose will form covalent compound AGEs with plasma. AGEs not only form intracellular and cellular diplomatic links with proteins but also form crosslinks with other endogenous key molecules including lipids and nucleic acids, thereby promoting the development of diabetic complications (Singh et al., 2014). Cognitive dysfunction has been documented as one of the complications of diabetes, suggesting a close link between diabetes and AD (Jash et al., 2020). One of the main symptoms of AD is impaired memory (Sharma et al., 2020); therefore, to test whether the memory is altered in mice after the injection of AGEs, we conducted the Morris Water Maze, Y-maze, and open field tests and found that the memory of AGE mice decreased significantly and anxiety behavior increased, which is consistent with previous AD research (Tian et al., 2019; Du et al., 2020). Subsequently, to further study whether the brain of AGE mice can develop AD symptoms, we assessed the expression of AD-related proteins such as P-tau and APP, which were significantly increased in the hippocampus of AGE mice. This indicates that AGEs promote the occurrence of AD symptoms.

Much research has been done on the relationship between diabetes and AD. Some researchers have proposed that insulin can affect the phosphorylation of tau protein through the GSK-3 signaling pathway (Jash et al., 2020) and that LiCl is an inhibitor of GSK-3 (Kurgan et al., 2019). Therefore, when treated with LiCl, AGEs were not able to phosphorylate tau in large amounts, thereby improving AD symptoms in AGE mice. However, our results did not show that AD symptoms in AGE mice were significantly improved after treatment with LiCl; therefore, we speculate that the GSK-3 signaling pathway is only one of the links between diabetes and AD and other mechanisms have not been studied. Therefore, through AGEs, we speculate that there is a complex relationship between diabetes and AD, and its specific molecular mechanism requires further study.

A previous study reported that AGEs/RAGE interactions can stimulate the activation of multiple signaling cascades, including PI3K, and reduce the mRNA expression of downstream proteins of PI3K signaling pathways, such as AKT2 (Abdelmageed et al., 2019). These data indicate that AGEs/RAGE interactions occur through the PI3K signaling pathway. Furthermore, studies have shown that normal activation of the PI3K signaling pathway can reduce tau hyperphosphorylation (Xiong et al., 2020). Our previous experimental results showed that the proportion of phosphorylated tau protein increased in the hippocampus of mice when AGEs were injected. We further explored whether this is caused by the PI3K signaling pathway. We found that when mice were injected with AGEs, the expression of PI3K, SRC, and ERK proteins in the hippocampus were decreased, and the expression of PI3K and SRC increased again after injection of its inhibitor LiCl (Figure 3). The class III PI3K/Beclin-1 pathway has certain autophagic activity to promote autophagy clearance of tau (Chen et al., 2020), suggesting that blocking of PI3K-related pathways will hinder tau clearance. AGEs can induce tau hyperphosphorylation in SK-N-SH cells, primary hippocampal neurons, and in SD rats through the RAGE/GSK-3 pathway (Li et al., 2012; Son et al., 2012). The deposits of AGEs will activate microglia and NADPH oxidase, affecting PI3K-related pathways, leading to ROS synthesis and release, and further leading to oxidative stress (Nam et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2020). In turn, this leads to the deposition of tau, suggesting that blocking the PI3K-related pathways will result in tau deposition. We speculate that AGEs promote the increase in tau phosphorylation by blocking the PI3K signaling pathway and down-regulating the expression of its downstream proteins, while LiCl has a certain relieving effect. However, its specific mechanism remains to be further studied.

Finally, we performed experiments on a diabetic rat model to verify whether symptoms similar to AD would occur in the diabetic model. We found that RAGE expression in the hippocampus of ZDF rats was increased significantly. At the same time, tau and APP expression were also increased, which is similar to the phenotype observed in the AD mouse model (Gallardo and Holtzman, 2019), further illustrating the relationship between diabetes and AD.

In conclusion, mice injected with AGEs showed significant AD-like features including decreased memory and increased phosphorylated tau and APP expression. These results suggest links between diabetes and AD. Patients with diabetes are at a higher risk of developing AD, and the possible underlying molecular components of this association are now beginning to emerge.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets presented in this study are included in the article.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by Animal Ethics Committee of Fudan University.

Author Contributions

YK and CZ designed the experiments. YK, FW, CL, YZ, and ZX conducted the experiments. BS and YG obtained funding and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Natalie Ward (Medical College of Wisconsin, Wauwatosa, WI, USA) for editing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. 81571345, 81701732), Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (No. 2018SHZDZX01), ZJLab, and Shanghai Municipal Key Clinical Specialty (shslczdzk03402).

References

- Abdelmageed M. E., Shehatou G. S., Abdelsalam R. A., Suddek G. M., Salem H. A. (2019). Cinnamaldehyde ameliorates STZ-induced rat diabetes through modulation of IRS1/PI3K/AKT2 pathway and AGEs/RAGE interaction. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 392, 243–258. 10.1007/s00210-018-1583-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S., Mahmood Z., Zahid S. (2015). Linking insulin with Alzheimer’s disease: emergence as type III diabetes. Neurol. Sci. 36, 1763–1769. 10.1007/s10072-015-2352-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf J. M., Ahmad S., Rabbani G., Hasan Q., Jan A. T., Lee E. J., et al. (2015a). 3-Deoxyglucosone: a potential glycating agent accountable for structural alteration in H3 histone protein through generation of different AGEs. PLoS One 10:e0116804. 10.1371/journal.pone.0116804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf J. M., Rabbani G., Ahmad S., Hasan Q., Khan R. H., Alam K., et al. (2015b). Glycation of H1 histone by 3-deoxyglucosone: effects on protein structure and generation of different advanced glycation end products. PLoS One 10:e0130630. 10.1371/journal.pone.0130630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf J. M., Ahmad S., Rabbani G., Jan A. T., Lee E. J., Khan R. H., et al. (2014). Physicochemical analysis of structural alteration and advanced glycation end products generation during glycation of H2A histone by 3-deoxyglucosone. IUBMB Life 66, 686–693. 10.1002/iub.1318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baig M. H., Ahmad K., Rabbani G., Choi I. (2018). Use of peptides for the management of Alzheimer’s disease: diagnosis and inhibition. Front. Aging Neurosci. 10:21. 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batkulwar K., Godbole R., Banarjee R., Kassaar O., Williams R. J., Kulkarni M. J. (2018). Advanced glycation end products modulate amyloidogenic APP processing and tau phosphorylation: a mechanistic link between glycation and the development of Alzheimer’s disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 9, 988–1000. 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunn H. F., Higgins P. J. (1981). Reaction of monosaccharides with proteins: possible evolutionary significance. Science 213, 222–224. 10.1126/science.12192669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z., Liu N., Wang C., Qin B., Zhou Y., Xiao M., et al. (2016). Role of RAGE in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 36, 483–495. 10.1007/s10571-015-0233-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Chen Y., Liang Y., Chen H., Ji X., Huang M. (2020). Berberine mitigates cognitive decline in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model by targeting both tau hyperphosphorylation and autophagic clearance. Biomed. Pharmacother. 121:109670. 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deane R. J. (2012). Is RAGE still a therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s disease? Future Med. Chem. 4, 915–925. 10.4155/fmc.12.51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deane R., Du Yan S., Submamaryan R. K., LaRue B., Jovanovic S., Hogg E., et al. (2003). RAGE mediates amyloid-β peptide transport across the blood-brain barrier and accumulation in brain. Nat. Med. 9, 907–913. 10.1038/nm890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deane R., Sagare A., Zlokovic B. V. (2008). The role of the cell surface LRP and soluble LRP in blood-brain barrier Aβ clearance in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 14, 1601–1605. 10.2174/138161208784705487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deane R., Zlokovic B. V. (2007). Role of the blood-brain barrier in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 4, 191–197. 10.2174/156720507780362245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y., Liu X., Zhu X., Liu Y., Wang X., Wu X. (2020). Activating transcription factor 6 reduces Aβ1–42 and restores memory in Alzheimer’s disease model mice. Int. J. Neurosci. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1080/00207454.2020.1715977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dukic-Stefanovic S., Gasic-Milenkovic J., Deuther-Conrad W., Munch G. (2003). Signal transduction pathways in mouse microglia N-11 cells activated by advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs). J. Neurochem. 87, 44–55. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01988.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang F., Yu Q., Arancio O., Chen D., Gore S. S., Yan S. S., et al. (2018). RAGE mediates Aβ accumulation in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease via modulation of β- and γ-secretase activity. Hum. Mol. Genet. 27, 1002–1014. 10.1093/hmg/ddy017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galasko D., Bell J., Mancuso J. Y., Kupiec J. W., Sabbagh M. N., van Dyck C., et al. (2014). Clinical trial of an inhibitor of RAGE-Aβ interactions in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 82, 1536–1542. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo G., Holtzman D. M. (2019). Amyloid-β and tau at the crossroads of Alzheimer’s disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1184, 187–203. 10.1007/978-981-32-9358-8_16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garay-Sevilla M. E., Regalado J. C., Malacara J. M., Nava L. E., Wrobel-Zasada K., Castro-Rivas A., et al. (2005). Advanced glycosylation end products in skin, serum, saliva and urine and its association with complications of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 28, 223–230. 10.1007/BF03345377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo C., Zhang S., Li J. Y., Ding C., Yang Z. H., Chai R., et al. (2016). Chronic hyperglycemia induced via the heterozygous knockout of Pdx1 worsens neuropathological lesion in an Alzheimer mouse model. Sci. Rep. 6:29396. 10.1038/srep29396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammes H. P., Alt A., Niwa T., Clausen J. T., Bretzel R. G., Brownlee M., et al. (1999). Differential accumulation of advanced glycation end products in the course of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetologia 42, 728–736. 10.1007/s001250051221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartog J. W., Voors A. A., Bakker S. J., Smit A. J., van Veldhuisen D. J. (2007). Advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) and heart failure: pathophysiology and clinical implications. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 9, 1146–1155. 10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K., Kunikata H., Yasuda M., Ito A., Aizawa N., Sawada S., et al. (2016). The relationship between advanced glycation end products and ocular circulation in type 2 diabetes. J. Diabetes Complications 30, 1371–1377. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2016.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C. C., Chung C. M., Leu H. B., Lin L. Y., Chiu C. C., Hsu C. Y., et al. (2014). Diabetes mellitus and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a nationwide population-based study. PLoS One 9:e87095. 10.1371/journal.pone.0087095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jash K., Gondaliya P., Kirave P., Kulkarni B., Sunkaria A., Kalia K. (2020). Cognitive dysfunction: a growing link between diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. Drug Dev. Res. 81, 144–164. 10.1002/ddr.21579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaraj R. L., Azimullah S., Beiram R. (2020). Diabetes as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease in the Middle East and its shared pathological mediators. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 27, 736–750. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2019.12.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juranek J., Ray R., Banach M., Rai V. (2015). Receptor for advanced glycation end-products in neurodegenerative diseases. Rev. Neurosci. 26, 691–698. 10.1515/revneuro-2015-0003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamynina A. V., Esteras N., Koroev D. O., Bobkova N. V., Balasanyants S. M., Simonyan R. A., et al. (2018). Synthetic fragments of receptor for advanced glycation end products bind β-amyloid 1–40 and protect primary brain cells from β-amyloid toxicity. Front. Neurosci. 12:681. 10.3389/fnins.2018.00681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraeuter A. K., Guest P. C., Sarnyai Z. (2019). The Y-Maze for assessment of spatial working and reference memory in mice. Methods Mol. Biol. 1916, 105–111. 10.1007/978-1-4939-8994-2_10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar Pasupulati A., Chitra P. S., Reddy G. B. (2016). Advanced glycation end products mediated cellular and molecular events in the pathology of diabetic nephropathy. Biomol. Concepts 7, 293–309. 10.1515/bmc-2016-0021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurgan N., Whitley K. C., Maddalena L. A., Moradi F., Stoikos J., Hamstra S. I., et al. (2019). A low-therapeutic dose of lithium inhibits GSK3 and enhances myoblast fusion in C2C12 cells. Cells 8:1340. 10.3390/cells8111340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane C. A., Hardy J., Schott J. M. (2018). Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 25, 59–70. 10.1111/ene.13439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin J. (2019). Parkinsonism in genetic and sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 149, 237–247. 10.1016/bs.irn.2019.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Liu D., Sun L., Lu Y., Zhang Z. (2012). Advanced glycation end products and neurodegenerative diseases: mechanisms and perspective. J. Neurol. Sci. 317, 1–5. 10.1016/j.jns.2012.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.-H., Lv B.-L., Xie J.-Z., Liu J., Zhou X.-W., Wang J.-Z. (2012). AGEs induce Alzheimer-like tau pathology and memory deficit via RAGE-mediated GSK-3 activation. Neurobiol. Aging 33, 1400–1410. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchsinger J. A., Tang M. X., Stern Y., Shea S., Mayeux R. (2001). Diabetes mellitus and risk of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with stroke in a multiethnic cohort. Am. J. Epidemiol. 154, 635–641. 10.1093/aje/154.7.635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam J. H., Park K. W., Park E. S., Lee Y. B., Lee H. G., Baik H. H., et al. (2012). Interleukin-13/-4-induced oxidative stress contributes to death of hippocampal neurons in aβ1–42-treated hippocampus in vivo. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 16, 1369–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negre-Salvayre A., Salvayre R., Auge N., Pamplona R., Portero-Otin M. (2009). Hyperglycemia and glycation in diabetic complications. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 11, 3071–3109. 10.1089/ars.2009.2484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowotny K., Jung T., Hohn A., Weber D., Grune T. (2015). Advanced glycation end products and oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biomolecules 5, 194–222. 10.3390/biom5010194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi L., Chen Z., Wang Y., Liu X., Liu X., Ke L., et al. (2017). Subcutaneous liraglutide ameliorates methylglyoxal-induced Alzheimer-like tau pathology and cognitive impairment by modulating tau hyperphosphorylation and glycogen synthase kinase-3β. Am. J. Transl. Res. 9, 247–260. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbani G., Ahn S. N. (2019). Structure, enzymatic activities, glycation and therapeutic potential of human serum albumin: a natural cargo. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 123, 979–990. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.11.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salahuddin P., Rabbani G., Khan R. H. (2014). The role of advanced glycation end products in various types of neurodegenerative disease: a therapeutic approach. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 19, 407–437. 10.2478/s11658-014-0205-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P., Sharma A., Fayaz F., Wakode S., Pottoo F. H. (2020). Biological signatures of Alzheimer disease. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 20, 770–781. 10.2174/1568026620666200228095553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara M., Sato N. (2017). Bidirectional interactions between diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem. Int. 108, 296–302. 10.1016/j.neuint.2017.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simó R., Ciudin A., Simo-Servat O., Hernandez C. (2017). Cognitive impairment and dementia: a new emerging complication of type 2 diabetes-The diabetologist’s perspective. Acta Diabetol. 54, 417–424. 10.1007/s00592-017-0970-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh V. P., Bali A., Singh N., Jaggi A. S. (2014). Advanced glycation end products and diabetic complications. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 18, 1–14. 10.4196/kjpp.2014.18.1.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh Y., Wang T., Geringer S. A., Stine K. J., Demchenko A. V. (2018). Regenerative glycosylation. J. Org. Chem. 83, 374–381. 10.1021/acs.joc.7b02768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son S. M., Jung E. S., Shin H. J., Byun J., Mook-Jung I. (2012). Aβ-induced formation of autophagosomes is mediated by RAGE-CaMKKβ-AMPK signaling. Neurobiol. Aging 33, 1006.e11–1006.e23. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.09.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridhar G. R., Lakshmi G., Nagamani G. (2015). Emerging links between type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. World J. Diabetes 6, 744–751. 10.4239/wjd.v6.i5.744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda S., Sato N., Rakugi H., Morishita R. (2011). Molecular mechanisms linking diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer disease: β-amyloid peptide, insulin signaling, and neuronal function. Mol. Biosyst. 7, 1822–1827. 10.1039/c0mb00302f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian H., Ding N., Guo M., Wang S., Wang Z., Liu H., et al. (2019). Analysis of learning and memory ability in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model using the morris water maze. J. Vis. Exp. 152:e60055. 10.3791/60055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicente Miranda H., Outeiro T. F. (2010). The sour side of neurodegenerative disorders: the effects of protein glycation. J. Pathol. 221, 13–25. 10.1002/path.2682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan W., Cao L., Liu L., Zhang C., Kalionis B., Tai X., et al. (2015). Aβ(1–42) oligomer-induced leakage in an in vitro blood-brain barrier model is associated with up-regulation of RAGE and metalloproteinases and down-regulation of tight junction scaffold proteins. J. Neurochem. 134, 382–393. 10.1111/jnc.13122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Chen F., Du Y. F., Long Y., Reed M. N., Hu M., et al. (2018). Targeted inhibition of RAGE reduces amyloid-β influx across the blood-brain barrier and improves cognitive deficits in db/db mice. Neuropharmacology 131, 143–153. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., He B., Hang W., Wu N., Xia L., Wang X., et al. (2018). Berberine alleviates tau hyperphosphorylation and axonopathy-associated with diabetic encephalopathy via restoring PI3K/Akt/GSK3β pathway. J. Alzheimers Dis. 65, 1385–1400. 10.3233/jad-180497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Li W., Zhou F., Feng R., Wang F., Zhang S., et al. (2019). ATP11B deficiency leads to impairment of hippocampal synaptic plasticity. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 688–702. 10.1093/jmcb/mjz042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Yu S., Hu J.-P., Wang C.-Y., Wang Y., Liu H.-X., et al. (2014). Streptozotocin-induced diabetes increases amyloid plaque deposition in AD transgenic mice through modulating AGEs/RAGE/NF-κB pathway. Int. J. Neurosci. 124, 601–608. 10.3109/00207454.2013.866110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei T., Wang Y., Xu W., Liu Y., Chen H., Yu Z. (2019). KCa3.1 deficiency attenuates neuroinflammation by regulating an astrocyte phenotype switch involving the PI3K/AKT/GSK3β pathway. Neurobiol. Dis. 132:104588. 10.1016/j.nbd.2019.104588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B., Wang Y., Shi C., Chen Y., Yu L., Li J., et al. (2019). Ribosylation-derived advanced glycation end products induce tau hyperphosphorylation through brain-derived neurotrophic factor reduction. J. Alzheimers Dis. 71, 291–305. 10.3233/jad-190158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong R., Wang X.-L., Wu J.-M., Tang Y., Qiu W.-Q., Shen X., et al. (2020). Polyphenols isolated from lychee seed inhibit Alzheimer’s disease-associated Tau through improving insulin resistance via the IRS-1/PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 251:112548. 10.1016/j.jep.2020.112548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi S., Nakamura N., Suematsu M., Kaseda K., Matsui T. (2015). Advanced glycation end products: a molecular target for vascular complications in diabetes. Mol. Med. 21, S32–S40. 10.2119/molmed.2015.00067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan S. D., Chen X., Fu J., Chen M., Zhu H., Roher A., et al. (1996). RAGE and amyloid-β peptide neurotoxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 382, 685–691. 10.1038/382685a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Huang N. Q., Yan F., Jin H., Zhou S. Y., Shi J. S., et al. (2018). Diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer’s disease: GSK-3β as a potential link. Behav. Brain Res. 339, 57–65. 10.1016/j.bbr.2017.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Liu S., Shi R., Zhao G. (2011). miR-27 promotes human gastric cancer cell metastasis by inducing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Genet. 204, 486–491. 10.1016/j.cancergen.2011.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z.-Y., Zhang Y.-Q., Zhang Y.-H., Wei X.-Z., Wang H., Zhang M., et al. (2019). The protective underlying mechanisms of Schisandrin on SH-SY5Y cell model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 82, 1019–1026. 10.1080/15287394.2019.1684007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L., Song H., Zhang Y., Ren Z., Li M., Fu Q. (2020). Polyphyllin VII attenuated RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation via inhibiting of TRAF6/c-Src/PI3K pathway and ROS production. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 21:112. 10.1186/s12891-020-3077-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets presented in this study are included in the article.