Abstract

Background

Breast engorgement is a painful condition affecting large numbers of women in the early postpartum period. It may lead to premature weaning, cracked nipples, mastitis and breast abscess. Various forms of treatment for engorgement have been studied but so far little evidence has been found on an effective intervention.

Objectives

This is an update of a systematic review first published by Snowden et al. in 2001 and subsequently published in 2010. The objective of this update is to seek new information on the best forms of treatment for breast engorgement in lactating women.

Search methods

We identified studies for inclusion through the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (30 June 2015) and searched reference lists of retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trials for eligibility, extracted data and conducted 'Risk of bias' assessments. Where insufficient data were presented in trial reports, we attempted to contact study authors and obtain necessary information. We assessed the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach.

Main results

In total, we included 13 studies with 919 women. In 10 studies individual women were the unit of analysis and in three studies, individual breasts were the unit of analysis. Four out of 13 studies were funded by an agency with a commercial interest, two received charitable funding, and two were funded by government agencies.

Trials examined interventions including non‐medical treatments: cabbage leaves (three studies), acupuncture (two studies), ultrasound (one study), acupressure (one study), scraping therapy (Gua Sha) (one study), cold breast‐packs and electromechanical massage (one study), and medical treatments: serrapeptase (one study), protease (one study) and subcutaneous oxytocin (one study). The studies were small and used different comparisons with only single studies contributing data to outcomes of this review. We were unable to pool results in meta‐analysis and only seven studies provided outcome data that could be included in data and analysis.

Non‐medical

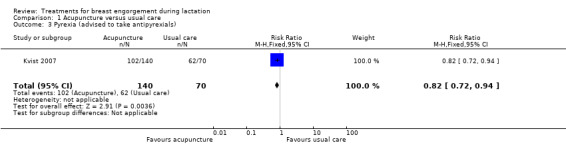

No differences were observed in the one study comparing acupuncture with usual care (advice and oxytocin spray) (risk ratio (RR) 0.50, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.13 to 1.92; one study; 140 women) in terms of cessation of breastfeeding. However, women in the acupuncture group were less likely to develop an abscess (RR 0.20, 95% CI 0.04 to 1.01; one study; 210 women), had less severe symptoms on day five (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.99), and had a lower rate of pyrexia (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.72 to 0.94) than women in the usual care group.

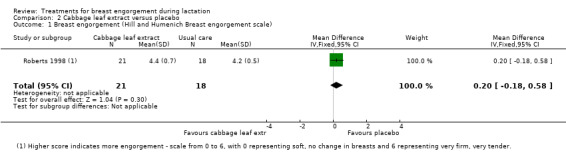

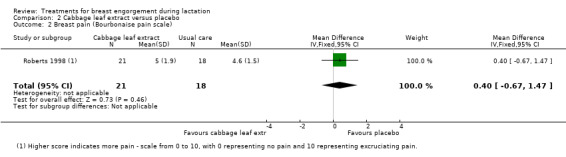

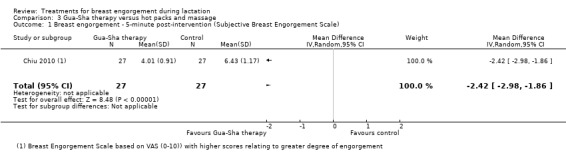

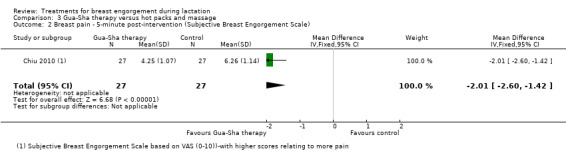

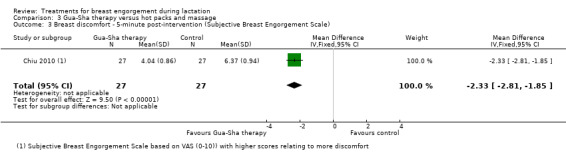

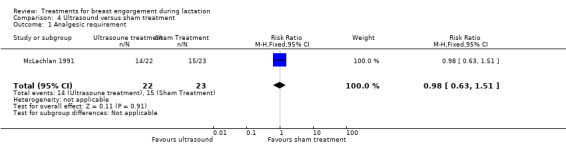

In another study with 39 women comparing cabbage leaf extract with placebo, no differences were observed in breast pain (mean difference (MD) 0.40, 95% CI ‐0.67 to 1.47; low‐quality evidence) or breast engorgement (MD 0.20, 95% CI ‐0.18 to 0.58; low‐quality evidence). There was no difference between ultrasound and sham treatment in analgesic requirement (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.51; one study; 45 women; low‐quality evidence). A study comparing Gua‐Sha therapy with hot packs and massage found a marked difference in breast engorgement (MD ‐2.42, 95% CI ‐2.98 to ‐1.86; one study; 54 women), breast pain (MD ‐2.01, 95% CI ‐2.60 to ‐1.42; one study; 54 women) and breast discomfort (MD ‐2.33, 95% CI ‐2.81 to ‐1.85; one study; 54 women) in favour of Gua‐Sha therapy five minutes post‐intervention, though both interventions significantly decreased breast temperature, engorgement, pain and discomfort at five and 30 minutes post‐treatment.

Results from individual trials that could not be included in data analysis suggested that there were no differences between room temperature and chilled cabbage leaves and between chilled cabbage leaves and gel packs, with all interventions producing some relief. Intermittent hot/cold packs applied for 20 minutes twice a day were found to be more effective than acupressure (P < 0.001). Acupuncture did not improve maternal satisfaction with breastfeeding. In another study, women who received breast‐shaped cold packs were more likely to experience a reduction in pain intensity than women who received usual care; however, the differences between groups at baseline, and the failure to observe randomisation, make this study at high risk of bias. One study found a decrease in breast temperature (P = 0.03) following electromechanical massage and pumping in comparison to manual methods; however, the high level of attrition and alternating method of sequence generation place this study at high risk of bias.

Medical

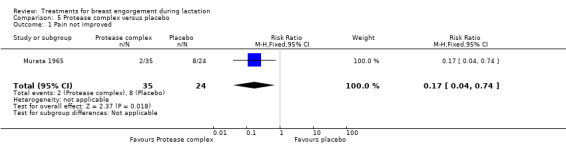

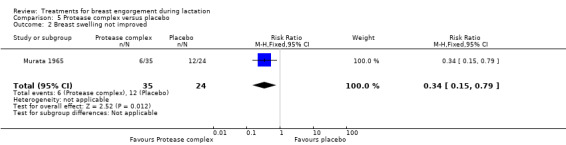

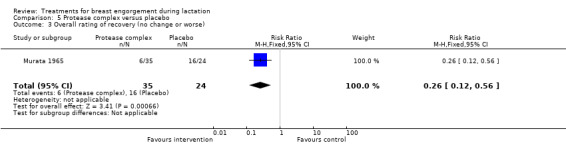

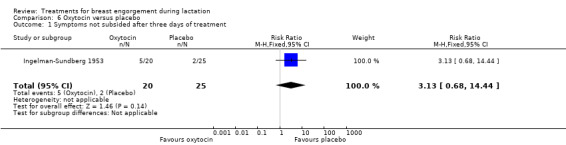

Women treated with protease complex were less likely to have no improvement in pain (RR 0.17, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.74; one study; 59 women) and swelling (RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.79; one study; 59 women) on the fourth day of treatment and less likely to experience no overall change in their symptoms or worsening of symptoms (RR 0.26, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.56). It should be noted that it is more than 40 years since the study was carried out, and we are not aware that this preparation is used in current practice. Subcutaneous oxytocin provided no relief at all in symptoms at three days (RR 3.13, 95% CI 0.68 to 14.44; one study; 45 women).

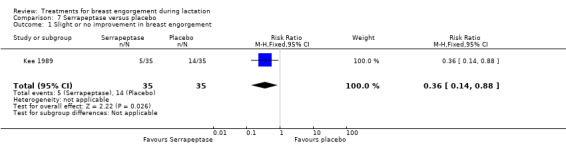

Serrapeptase was found to produce some relief in breast pain, induration and swelling, when compared to placebo, with a fewer number of women experiencing slight to no improvement in overall breast engorgement, swelling and breast pain.

Overall, the risk of bias of studies in the review is high. The overall quality as assessed using the GRADE approach was found to be low due to limitations in study design and the small number of women in the included studies, with only single studies providing data for analysis.

Authors' conclusions

Although some interventions such as hot/cold packs, Gua‐Sha (scraping therapy), acupuncture, cabbage leaves and proteolytic enzymes may be promising for the treatment of breast engorgement during lactation, there is insufficient evidence from published trials on any intervention to justify widespread implementation. More robust research is urgently needed on the treatment of breast engorgement.

Plain language summary

Treatment for breast engorgement (overfull, hard, painful breasts) in breastfeeding women

Review question

What are the best forms of treatment for engorged breasts in breastfeeding women?

Background

Breast engorgement is the overfilling of breasts with milk leading to swollen, hard and painful breasts. Many women experience this during the first few days after giving birth, although it can occur later. It is more common when the timing of breastfeeding is restricted or the baby has difficulty sucking or the mother is separated from her newborn. This leads to the breasts not being emptied properly. Breast engorgement may make it difficult for women to breastfeed. It may lead to complications such as inflammation of the breast, infection and sore/cracked nipples. So far, consistent evidence for effective forms of treatment is lacking.

Study characteristics

We searched for trials on any treatments for breast engorgement in breastfeeding women. We looked at 13 trials including 919 breastfeeding women who had engorged breasts. The trials looked at treatments including acupuncture, acupressure, cabbage leaves, cold packs, medication, massage and ultrasound. Four of the studies were funded by an agency with a commercial interest in the results of the studies, two received charitable funding and two were funded by government agencies. The other five did not declare the source of funding.

Results

One study comparing acupuncture with usual care (advice and oxytocin spray) found no difference in terms of stopping breastfeeding. However, women in the acupuncture group were less likely to develop an abscess, had less severe symptoms on day five and had a lower rate of fever than women in the usual care group. Three trials looking at cabbage leaves showed no difference between room temperature and chilled cabbage leaves, between chilled cabbage leaves and gel packs and between cabbage cream and the inactive cream; however, all forms of treatment provided some relief. Hot/cold packs were found to be more effective than acupressure. Gua Sha scraping therapy was found to be more effective than hot packs and massage in reducing symptoms of breast engorgement, though both forms of treatment decreased breast temperature, engorgement, pain and discomfort at five and 30 minutes after treatment. A study on ultrasound therapy had the same, minimal effect as the fake ultrasound, whereas oxytocin injections in another study provided no relief at all. When breast‐shaped cold gel packs were compared with routine care, women who used gel packs seemed to have less pain; however, the study was of very low quality making the results unreliable.

Quality of evidence

The quality of evidence was low due to the small number of participants in the included studies and limited number of studies looking at the same outcomes. More robust research is urgently needed on the treatment of breast engorgement.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Cabbage cream for breast engorgement during lactation.

| Cabbage cream for breast engorgement during lactation | ||||||

|

Patient or population: women with breast engorgement during lactation

Settings: Royal Darwin and Darwin Private Hospital, Australia

Intervention: cabbage cream Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Cabbage cream | |||||

| Breast pain Bourbonaise pain scale | The mean breast pain in the intervention groups was 0.4 higher (0.67 lower to 1.47 higher) | 39 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 |

Higher score indicates more pain ‐ Bourbonaise pain scale ranks pain on a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 representing no pain and 10 representing excruciating pain. | ||

| Breast induration/hardness | This outcome was not reported in the trial. | |||||

| Breast swelling | This outcome was not reported in the trial. | |||||

| Breast engorgement Hill and Humenich Breast engorgement scale Follow‐up: mean 4 days | The mean engorgement in the intervention groups was 0.2 higher (0.18 lower to 0.58 higher) | 39 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 |

Higher score indicates more engorgement ‐ Hill and Humenich Breast engorgement scale ranks engorgement on a scale from 0 to 6, with 0 representing soft, no change in breasts and 6 representing very firm, very tender. | ||

| Analgesic requirement | This outcome was not reported in the trial. | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 The number of participants was even smaller than the pre‐determined sample size. 2 Limitations in study design due to a significant imbalance in primiparas at baseline (high risk of bias for other bias).

Background

In recognition of the importance of breastfeeding for maternal and infant well‐being, and for society at large, the World Health Organization recommends that all babies should be exclusively breastfed for the first six months of life and then continue to receive breast milk, along with appropriate complementary foods, up to two years of age or beyond (WHO 2003). Despite this, less than 3% of women breastfeed their infants for 24 months (Carletti 2011; Hure 2013; Liu 2013). One of the most common factors associated with premature cessation of breastfeeding is difficulty with lactation (Odom 2013), including breast engorgement (Hauck 2011).

Description of the condition

Breast engorgement is the pathological overfilling of the breasts with milk, characterised by hard, painful, tight breasts and difficulty breastfeeding. It is usually due to compromised milk removal, either from restrictive feeding practices and/or ineffective sucking, or less commonly overproduction of milk. Augmentation mammoplasty (surgical enlargement of breasts) may also predispose to engorgement (Acarturk 2005). It should be differentiated from normal breast fullness, often called physiological breast engorgement (Nikodem 1993), occurring between day two to three postpartum, in which secretory activation of the breast is triggered by the delivery of the placenta (progesterone withdrawal) and subsequent rise in prolactin levels (Hale 2007). Increased milk production and interstitial tissue oedema ensue resulting in visibly larger, warmer and slightly uncomfortable breasts. In women with normal breast fullness, milk flow from the breast is not hindered and with frequent, efficient breastfeeding, discomfort resolves within a few days.

Breast engorgement, on the other hand, is a distressing and debilitating condition affecting between 15% and 50% of women (Hill 1994). Prevalence may be even higher depending on the definition used. Where engorgement was described as part of an inflammatory process (any mixture of erythema, pain, pyrexia, breast tension and resistance in breast tissue), 75% of women in a Swedish study experienced symptoms within eight weeks postpartum (Kvist 2004). Some level of breast tenderness during the first five days after birth was experienced by 72% of women in a study by Hill and Humenick. Engorgement symptoms occur most commonly between the second and fifth days postpartum (Hill 1994; Roberts 1995a), peaking at day five (Hill 1994), but may occur as late as day 14 (Humenick 1994), and are usually diffuse, bilateral and may be associated with a low‐grade fever. Complications are common and include sore/damaged nipples, mastitis, abscess formation, decreased milk supply (Giugliani 2004), premature introduction of breast milk substitutes, and premature cessation of breastfeeding (Mass 2004). Difficulty in feeding the baby occurs in up to 82% of mothers with breast engorgement (Roberts 1995a).

Description of the intervention

Many interventions for the treatment of breast engorgement have been suggested in the past. Some treatments have been abandoned, such as mechanical compression (binding) of the breast, complete manual emptying of the breast, fluid restriction, the use of diuretics, oestrogens and bromocriptine, due to safety concerns. Others, such as some anti‐inflammatory medications (bromelain, serrapeptase) have been tested on small sample sizes only, with no long‐term safety data, and hence have not been widely accepted. Oxytocin, due to its role in inducing the milk‐ejection reflex, has also been proposed as an efficacious agent for the relief of postpartum breast engorgement. Other modalities, such as ultrasound therapy, acupuncture and acupressure have also been explored. A popular form of treatment of breast engorgement is the application of cabbage leaves. Even though no active pharmacological substance in cabbage leaves has been identified in the literature, its convenient shape, low cost, wide availability and purportedly soothing effect make it a sought after treatment. Reverse pressure softening, a technique that uses gentle positive pressure with the finger‐tips to soften the areola, has been shown to improve attachment of the infant to the breast during engorgement (Cotterman 2004), hence making it a potential tool for the treatment of breast engorgement, but relevant outcomes have not been tested in a controlled setting.

Current recommendations for the treatment of breast engorgement include various measures aimed at emptying the breast sufficiently to alleviate discomfort, facilitate breastfeeding and prevent complications. These include applying moist heat to the breast prior to feeding to aid oxytocin uptake, frequent feeding, softening the areola prior to attachment, correct positioning and attachment of the baby to the breast during breastfeeding (Mass 2004), gentle massage during feeding, and applying cold compresses after feeding (Core Curriculum 2013), along with analgesics (e.g. paracetamol) and anti‐inflammatory medication (e.g. ibuprofen), if needed (ABM 2009). If breastfeeding is not possible, hand‐expressing or pumping milk to comfort is recommended, along with other symptomatic measures.

In some countries, such as Sweden, oxytocin spray is routinely used in an attempt to enhance drainage of engorged breasts. A postal survey of all 57 breastfeeding clinics in Sweden, revealed that oxytocin spray, unrefined cotton wool (as a comfort measure) and acupuncture were used by 87%, 72% and 56% of responding clinics, respectively, for the treatment of breast inflammatory conditions (Kvist 2004). In other countries, such as Taiwan, cold therapies for breast engorgement are discouraged during the month following delivery. Instead, milk expression after the application of hot packs is widely used, as are traditional Chinese therapies.

How the intervention might work

Ideally, treatment of breast engorgement should: 1) provide rapid relief of breast pain; 2) enable successful attachment of the baby to the breast; 3) facilitate efficient drainage of milk from the breasts; and 4) prevent known complications such as mastitis and breast abscess. Optimal treatment should rapidly result in relatively soft, non‐tender breasts from which the mother can easily and successfully feed her infant. Numerous treatments have been studied in an attempt to achieve these goals. The interventions studied in this review are based on the following assumptions:

administration of exogenous oxytocin: release of endogenous oxytocin, from the posterior pituitary gland, is known to cause contraction of the mammary myoepithelial cells, which surround milk‐producing alveoli, resulting in expulsion of milk towards the nipple, known as the milk‐ejection reflex. In engorgement, the milk‐ejection reflex may be inhibited due to vascular congestion in the breast preventing oxytocin from reaching the myoepithelial cells;

acupuncture: the stimulation of certain acupuncture points along the skin of the body with acupuncture needles is believed, according to traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), to relieve obstructions in the flow of energy, enabling the body to heal, leading to improved microcirculation and flow of milk;

scraping therapy (Gua‐Sha): the stimulation of acupoints, using a scraping motion on the skin, is believed, according to TCM, to improve circulation and metabolism by removing obstructions and revitalising meridians. In TCM, 14 channels of energy, known as meridians, are believed to run throughout the body. Meridians passing just under the skin surface present acupoints;

thermal (continuous) ultrasound therapy: it is thought treatment may facilitate the removal of milk from the engorged breast by facilitating milk let‐down, leading to less pain and hardness;

enzyme therapy: believed to be able to suppress inflammation, abate and alleviate pain and oedema and accelerate the circulation of blood and lymph;

anti‐inflammatory medication: known to reduce symptoms of inflammation, such as pain, redness and swelling, therefore assumed to relieve the symptoms of engorgement;

cabbage leaves: thought to possibly contain a chemical that the mother's skin absorbs, thus reducing oedema and increasing milk flow. Usually applied chilled which induces vasoconstriction and further decreases oedema;

cold packs: the application of cold is thought to be soothing and to decrease the blood flow to the skin by vasoconstriction, which in turn is believed to decrease engorgement;

massage: gentle breast massage is thought to induce the milk‐ejection reflex, mobilise the milk and hence reduce the symptoms of breast engorgement.

Why it is important to do this review

Breastfeeding is the normal way to feed infants, resulting in optimal growth and development. In addition, it provides a stimulus for the bonding process between a mother and her baby, as well as protecting them both from disease. A mother's choice to breastfeed is often hampered by breastfeeding difficulties. Breast engorgement is a common condition affecting up to half of all women who choose to breastfeed (Hill 1994). Apart from causing distressing symptoms for the mother, it can lead to serious complications for the breastfeeding dyad, including the premature cessation of breastfeeding. Earlier systematic reviews on this topic have found insufficient evidence on effective treatments for breast engorgement but in the interim, several new studies have been reported which may assist in finding an effective treatment for this troubling condition. Additionally, in the era of HIV, exclusive breastfeeding has received attention in an effort to prevent mother‐to‐child transmission. Failure to identify the best forms of treatment of breast engorgement may result in women mixing breast and formula feeding, thus increasing their risk of HIV transmission.

This Cochrane systematic review is an update of the one first published by Snowden 2001, and subsequently re‐published in 2010. The previous reviews called for robust research to address the lack of evidence for the treatment of breast engorgement. This review seeks to evaluate current evidence on the best forms of treatment available.

Objectives

To identify the best form of treatment for breast engorgement in breastfeeding women.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised and quasi‐randomised (method of allocating participants to a treatment that is not strictly random, e.g. by date of birth, hospital record number, alternation) controlled trials evaluating treatments for breast engorgement in breastfeeding women. Cluster‐randomised trials were eligible for inclusion. Cross‐over trials were not eligible for inclusion.

Studies reported in abstract form were eligible for inclusion, provided that there was sufficient information to allow assessment of eligibility and risk of bias; if information provided in abstracts was insufficient, we tried to contact study authors for more information, or failing that, studies were classified as 'awaiting assessment' until publication of the full trial report. In this version of the review we identified one study reported in abstract form only. It did not contain sufficient information so study authors were contacted and the full report was obtained.

Types of participants

All women receiving any treatment for breast engorgement during breastfeeding.

Types of interventions

Non‐medical forms of treatment (acupuncture, cabbage leaves)

Medical treatments (oxytocin, protease)

Medical and non‐medical forms of treatment combined

Information and advice on breastfeeding

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Breast pain (as described by trial authors) (not pre‐specified)

Breast induration/hardness (as described by trial authors) (not pre‐specified)

Breast swelling (as described by trial authors) (not pre‐specified)

Breast engorgement (as described by trial authors) (not pre‐specified)

Secondary outcomes

Pyrexia

Mastitis

Breast abscess

Maternal opinion of treatment

Maternal acceptance of treatment

Analgesic requirement

Hospital admission

Woman's confidence in continuing to breastfeed

Cessation of breastfeeding

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting their Information Specialist (30 June 2015)

The Register is a database containing over 21,000 reports of controlled trials in the field of pregnancy and childbirth. For full search methods used to populate the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register including the detailed search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL; the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service, please follow this link to the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group in The Cochrane Library and select the ‘Specialized Register ’ section from the options on the left side of the screen.

Briefly, the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by their Information Specialist and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE (Ovid);

weekly searches of Embase (Ovid);

monthly searches of CINAHL (EBSCO);

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Search results are screened by two people and the full text of all relevant trial reports identified through the searching activities described above is reviewed. Based on the intervention described, each trial report is assigned a number that corresponds to a specific Pregnancy and Childbirth Group review topic (or topics), and is then added to the Register. The Information Specialist searches the Register for each review using this topic number rather than keywords. This results in a more specific search set which has been fully accounted for in the relevant review sections (Included studies; Excluded studies).

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of retrieved studies.

We did not apply any language or date restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For methods used in the previous version of this review, seeMangesi 2010.

For this update, the following methods were used for assessing the reports that were identified as a result of the updated search.

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Selection of studies

Two review authors, one of whom is a content expert (IZG), independently assessed all the studies identified as a result of the search strategy to decide whether they met the inclusion criteria. We resolved any disagreements through discussion. We contacted trial authors for additional information where necessary.

Data extraction and management

We used the standard Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group data extraction template to extract data from the eligible studies. Both review authors independently extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion. We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2014) and cross‐checked them for accuracy.

Where information regarding any of the identified studies was unclear or incomplete, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details. We managed to establish contact with authors of three reports (Ahmadi 2011; Chiu 2010; Roberts 1998) resulting in all three studies being included in the final analysis. Through the assistance of the Campbell and Cochrane Equity and Methods Group, we managed to translate a report written in Farsi (Ahmadi 2011) and extract necessary data.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreement by discussion. The following domains were assessed.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding would be unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we re‐included missing data in the analyses which we undertook.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (less than 10% missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; `as treated` analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study's pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study's pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so could not be used; study failed to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

low risk of other bias;

high risk of other bias;

unclear whether there is risk of other bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it likely to impact on the findings. We planned to explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses, but were unable to do this due to too few studies included in any single analysis.

Assessment of the quality of the evidence using GRADE

For this update the quality of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach as outlined in the GRADE handbook. We looked at cabbage cream versus placebo since one included study addresses two of our primary outcomes.

We planned to report on the following outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' table:

Breast pain

Breast induration/hardness

Breast swelling

Breast engorgement

Analgesic requirement

However, there was no data available on breast induration/hardness, breast swelling or analgesic requirement.

We used GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool to import data from Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan 2014) in order to create a ’Summary of findings’ table. A summary of the intervention effect and a measure of quality for each of the above outcomes was produced using the GRADE approach. The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome. The evidence can be downgraded from 'high quality' by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments for risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates or potential publication bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we used the mean difference if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. In future updates, if necessary, we will use the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measure the same outcome, but use different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We had planned to include cluster‐randomised trials but we identified none. In future updates of this review, if we identify any eligible cluster‐randomised trials we will include them in the analyses along with individually‐randomised trials. We will adjust their sample sizes using the methods described in the Handbook [Section 16.3.4 or 16.3.6] using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Cross‐over trials

Cross‐over trials are not eligible for inclusion.

Other unit of analysis issues

Several of the studies included in the review used breasts rather than women as the unit of analysis (McLachlan 1991; Roberts 1995; Roberts 1995a). We are aware that a woman's breasts (engorged or not) are unlikely to be independent of each other and such non‐independent data require special methods of analysis (Kvist 2007). In this version of the review, data were not presented in a way that allowed us to include them in the data tables and so we have presented a brief narrative description of results. If usable data become available in the future we will seek statistical help with analysis.

Dealing with missing data

We obtained missing data from a number of study authors (see Characteristics of included studies for details).

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition.

For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and all participants were analysed in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

In this version of the review, as so few trials contributed data and each examined different interventions, we were unable to combine results in meta‐analyses. In future updates of the review if more data are added, we plan to assess heterogeneity among trials. We will assess statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I² and Chi² statistics. We will regard heterogeneity as substantial if an I² is greater than 30% and either a Tau² is greater than zero, or there is a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

In future updates, if there are 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis we will investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry is suggested by a visual assessment, we will perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using Review Manager (RevMan 2014). In this version of the review, we could not combine results from trials due to different interventions being evaluated. In future updates, if more data are available, we plan to use fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data in the absence of moderate or high levels of heterogeneity.

In future updates, if there is clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differ between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity is detected, we will use random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary, if an average treatment effect across trials is considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary will be treated as the average of the range of possible treatment effects and we will discuss the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect is not clinically meaningful, we will not combine trials. If we use random‐effects analyses, the results will be presented as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, and the estimates of Tau² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We were unable to combine any of the studies to allow us to do subgroup analysis because studies were few and they evaluated different interventions.

In future updates of this review, if data do become available, we will carry out subgroup analysis for primary outcomes and only those secondary outcomes which may be confounded by the condition of the woman such as whether the woman had caesarean section or delivered spontaneously. These secondary outcomes include pyrexia, analgesic requirement and hospital admission.

Women who delivered spontaneously and those who delivered by caesarean section

Primiparous and multiparous women

We will assess subgroup differences by interaction tests available within RevMan (RevMan 2014). We will report the results of subgroup analyses quoting the Chi² statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value.

Sensitivity analysis

In this version of the review we included too few studies (examining several different types of interventions) to allow meaningful sensitivity analysis. We will carry out sensitivity analysis in future updates if more studies are available.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

See: Figure 1

Using the search strategy, we identified 26 reports of 22 studies, examining treatments for breast engorgement in breastfeeding women. After assessing eligibility we included 13 studies (16 reports), one of which was in the form of an abstract (Ahmadi 2011). Additional information was sought from the authors who sent the full text, in Farsi. This was translated with the help of the Campbell and Cochrane Equity Methods Group.

Included studies

We have included 13 studies carried out over a period of more than 60 years (from Ingelman‐Sundberg 1953 to Batista 2014), during which attitudes towards breastfeeding and the types and availability of treatments for women with breast engorgement have changed considerably.

All of the included studies focused on women with signs and symptoms of breast engorgement. In most of the studies, women with swollen, hard, painful breasts (and sometimes with pyrexia) were generally recruited in the early postnatal period (two to 10 days postpartum). In the study by Kvist 2007 women were recruited at breastfeeding clinics rather than in hospital postnatal wards, and may have been breastfeeding for some time, although the majority were seen within two weeks of giving birth. In one study, the focus was specifically on women who had caesarean births (Robson 1990), and in another on women who sought care at a human milk bank.(Batista 2014).

The studies we have included in the review examined the effects of a broad range of interventions, and data were sometimes presented in a way that did not allow us to enter them into RevMan tables (Batista 2014; Kvist 2004; Murata 1965; Roberts 1995; Roberts 1995a; Robson 1990); for these studies we have presented a brief narrative summary of findings. Interventions included:

acupuncture versus usual care (Kvist 2004; Kvist 2007);

acupressure versus hot and cold compresses (Ahmadi 2011);

cabbage leaves (cold versus room temperature leaves (Roberts 1995)); chilled cabbage leaves versus chilled gel packs (Roberts 1995a); cabbage leaf extract versus placebo (Roberts 1998);

cold packs versus routine care (Robson 1990);

protease complex tablets versus placebo (Murata 1965);

ultrasound versus sham ultrasound (McLachlan 1991);

serrapeptase versus placebo (Kee 1989);

Gua‐Sha (scraping) therapy versus hot packs and massage (Chiu 2010);

subcutaneous oxytocin versus placebo (Ingelman‐Sundberg 1953);

electromechanical breast massage followed by mechanical pumping versus manual breast massage followed by manual pumping (Batista 2014).

The broad range of interventions studied meant that we were not able to pool data from more than one study in any of the analyses.

Further details on the women participating in the included studies and descriptions of the interventions can be found in the Characteristics of included studies tables.

Excluded studies

We excluded nine studies (10 reports) identified by the search strategy. The main reasons for exclusion were that studies examined the prevention of breast engorgement (Nikodem 1993) in women whose breasts were not yet engorged, or examined interventions to suppress lactation in women who did not intend to breastfeed, rather than examining interventions to treat the symptoms of engorgement in women who were breastfeeding their babies (Booker 1970; Filteau 1999; Garry 1956; King 1958; Phillips 1975; Roser 1966; Ryan 1962). Finally, we excluded one study that was otherwise eligible for inclusion, because not all of the women recruited were receiving an intervention to treat breast engorgement (Stenchever 1962).

Approximately half of the women recruited in the Nikodem 1993 study did not have symptoms of breast engorgement and the intervention aimed to prevent rather than treat symptoms in these women. Separate results were not available for women with engorged breasts seeking symptom relief. We have provided further information on these studies in the Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

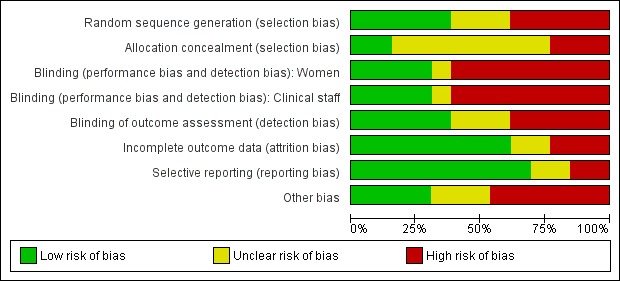

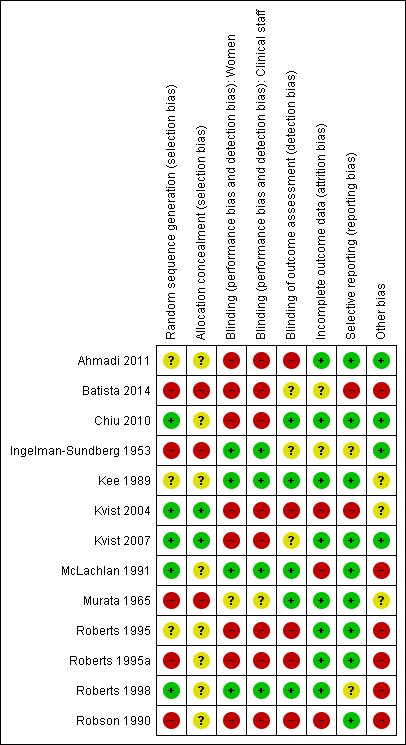

Risk of bias in included studies

We found it difficult to assess risk of bias in the included studies as the methods used in the trials were not generally well‐described. Most authors reported that the trial was a randomised controlled trial but did not describe how sequence generation or allocation concealment was performed. Unavailability of this information resulted in the risk of bias being categorised as unclear.

Please see Figure 1 and Figure 2 for a summary of 'Risk of bias' assessments.

1.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

In two studies we judged that the methods used to conceal group allocation at the point of randomisation were adequate; in these studies group assignments were concealed in sealed opaque sequentially numbered envelopes (Kvist 2004; Kvist 2007). In all of the remaining studies, we assessed that methods to conceal allocation were inadequate or unclear. Quasi‐randomisation was used in four trials; group allocation was by odd or even case‐note number in the Ingelman‐Sundberg 1953 trial, by day of the week in the Murata 1965 trial, and in the two studies by Roberts (Roberts 1995; Roberts 1995a), all women received both the experimental and control interventions, as breasts rather than women were randomised. In one study a "balanced block randomisation sequence" was used, but it was not clear what methods were used to conceal group allocation (McLachlan 1991). Similarly, a "computer‐generated block randomisation list" was produced by Chiu 2010, but the method of allocation concealment was not described. One of the study authors was contacted for clarification but information on sequence generation only was provided. Two studies (Ahmadi 2011; Kee 1989) were characterised as randomised controlled trials but neither sequence generation nor allocation concealment were reported; the Ahmadi paper only states that the women were randomly assigned to one intervention or the other in a way that would create two intervention groups of equal size. Even distribution of baseline characteristics (education level, career, number of births and type of birth) suggests that randomisation was adequate, but incomplete reporting resulted in the study being categorised as unclear. Attempts were made to contact the Kee study authors to clarify selection bias but neither the journal in which the paper was published, nor the affiliated institution knew of the authors whereabouts. Allocation concealment was classified as unclear in the Roberts 1998 study because even though group assignments were placed in sealed envelopes, it is not stated whether they were opaque or non‐opaque. Although coin toss was used for initial random sequence generation in the Batista 2014 study, intervention options were alternated thereafter, placing this study at high risk of selection bias. Finally, in the study by Robson 1990 there were serious problems with the way randomisation was carried out; a table of random numbers was used to decide the randomisation sequence but the allocation sequence was not necessarily observed, so, for example, women with the most distressing symptoms assigned to the control group were moved into the intervention group, and there was no intention‐to‐treat analysis.

Blinding

In studies where different types of interventions were compared, blinding participants and clinical staff would not be feasible and was not attempted (Ahmadi 2011; Batista 2014; Chiu 2010;Kvist 2004; Kvist 2007; Roberts 1995; Roberts 1995a; Robson 1990). The lack of blinding (of women, staff and outcome assessors) in these studies may represent a serious source of bias, as many of the outcomes measured (subjective views about treatment and assessment of symptoms) may have been influenced by knowledge of treatment assignment. In the study by McLachlan 1991 comparing ultrasound versus sham ultrasound, it was reported that women and staff were blind to which machine was which. However, in this study breasts rather than women were randomised and one breast may have been randomised to receive ultrasound and the other sham treatment. It was reported that the same machine was always used to treat the same breast. It is not clear how convincing to women and staff this attempt at blinding was, and it is difficult to imagine full compliance with this blinding procedure in the context of busy postnatal wards. Four other studies used placebo methods: in Murata 1965, protease complex tablets were compared with lactose‐containing placebo tablets; in the Ingelman‐Sundberg 1953, subcutaneous oxytocin was compared with physiological saline injections; in Kee 1989, oral serrapeptase was compared with specially made control tablets that were identical in appearance and given according to the same regimen; and in the Roberts 1998 trial a cream containing cabbage leaf extract was compared with a base/placebo cream, with rosewater added to both creams to camouflage the residual odour of cabbage. It is unclear from the Murata 1965 report whether the tablets used were identical, hence we have categorised this study as unclear, as opposed to the other studies which were judged to be at low risk of performance bias.

In terms of outcome assessment, there was no mention of blinding of outcome assessors in three studies (Batista 2014; Ingelman‐Sundberg 1953; Kvist 2007). Outcome assessment was clearly not blinded in five studies (Ahmadi 2011; Kvist 2004; Roberts 1995; Roberts 1995a; Robson 1990) and in the remaining five studies, there was evidence that outcome assessment had been carried out by assessors blinded to group assignment (Chiu 2010; Kee 1989; McLachlan 1991; Murata 1965; Roberts 1998).

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed that the level of attrition bias was unclear in one older study (Ingelman‐Sundberg 1953), which did not mention how incomplete outcome data were addressed, and in the study by Batista 2014, where the final sample size is more than 10‐fold smaller than the calculated sample size. Three studies were assessed as high risk of attrition bias (Kvist 2004; McLachlan 1991; Robson 1990) as information on loss to follow‐up, or denominators in the results section, may not have been explicit. No attrition was apparent in the studies by Roberts (Roberts 1995; Roberts 1995a; Roberts 1998), and there appeared to be low levels of attrition (less than 5%) in the studies by Ahmadi 2011, Chiu 2010, Kee 1989, Kvist 2007, and Murata 1965.

Selective reporting

We did not have study protocols to adequately assess within‐study selective reporting bias. We assessed selective reporting bias by comparing what was listed in the methods section of the study with what was reported in the results section. Most studies (Ahmadi 2011; Chiu 2010; Kee 1989; Kvist 2007; McLachlan 1991; Murata 1965; Roberts 1995a; Roberts 1995; Robson 1990) reported outcomes that were pre‐stated in the methods section and on outcomes of interest in this review. There is an unclear risk of bias in two studies: Roberts 1998 because whilst the authors have mentioned the outcomes they intended to assess, they presented the results with the two groups combined; in Ingelman‐Sundberg 1953, the authors report their outcomes in percentages, not in numbers out of the totals, which made it difficult to determine the denominators. Kvist 2004 carries a risk of bias as the authors mention that the study had to be stopped prematurely but no data are given. Also, they do not mention in the results one of the outcomes (resistance of breast tissue), which was listed in the methods' section. Other outcomes are mentioned, as non‐significant results, but are not reported adequately. In the study by Batista 2014, participants were evaluated based on clinical exam and thermography but only thermography is reported for both groups placing this study at high risk of reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

There was considerable baseline imbalance in the study by Robson 1990. Women in the control group had much lower pre‐test pain scores. There was also some deviation from protocol in this study: three women who were described as having "heightened distress levels" assigned to the intervention group were moved into the control group as this was perceived as being less demanding of their time, and one mother with severe discomfort asked to be assigned to the intervention group. In all, the randomisation schedule was not observed in eight cases. This represents a serious source of bias. There was no intention‐to‐treat analysis.

In another study (Roberts 1998), a significant baseline imbalance was found in the number of primiparas. Authors were contacted but no explanation was found. This may have been due to chance or a small sample size but may also have been due to possible problems with allocation concealment or compromised blinding, hence we made a judgement of possible high risk of bias.

There was considerable risk of bias in Batista 2014; no baseline characteristics were provided for included participants, although varying degrees of engorgement were alluded to, implying the possibility of baseline imbalance. Additionally, the study was severely underpowered, limiting its precision. No statement of conflict of interest or sponsorship was provided, raising the possibility of industry funding.

In three of the included studies, randomisation and analysis was at the level of breasts rather than women (McLachlan 1991; Roberts 1995; Roberts 1995a). McLachlan 1991 state that in their study, when the visual analogue scale was used, it was not always easy for women to make a clear distinction between the left and right breast. This may be an indication that having an individual breast as a unit of analysis is not ideal. In the studies there was no adjustment made for the non‐independence of breasts, and we found interpretation of results difficult. This difficulty was exacerbated in the study by Roberts 1995, because the pretest rating of symptoms was for both breasts together (an overall rating), whereas at post‐test, women provided ratings for separate breasts. It was therefore not possible for us to understand the possible differences between pre‐ and post‐test scores.

In one study (Kvist 2004), insufficient information was available, due to lack of clarity in reporting, to assess whether an important risk of bias exists. In the Murata 1965 and Kee 1989 studies the active tablets used in the trial were supplied by a pharmaceutical company, hence it was unclear whether a vested interest may have influenced study results. The remaining studies (Ahmadi 2011; Chiu 2010; Ingelman‐Sundberg 1953; Kvist 2007) appeared to be free of other sources of bias.

We were not able to examine possible publication bias using funnel plots because of the small number of studies included in the review.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Interventions to treat breast engorgement: 13 studies with 919 women

We included 13 studies with 919 breastfeeding women; 171 of whom were analysed at the individual breast level (Ahmadi 2011; McLachlan 1991; Roberts 1995; Roberts 1995a). We were unable to pool any results from studies in meta‐analysis because of the broad range of interventions examined, and the way in which outcomes were assessed and reported in these trials. We have set out separate comparisons for each type of intervention in the text below, and in the data tables; in some studies we were not able to include all outcome data in tables because of the form in which results were presented in research reports; for these outcomes we provide a brief description of findings as reported by the trial authors. Most of the studies did not provide usable information on the review's primary outcomes (pain, breast engorgement, breast swelling and breast induration), and so we have set out findings for both primary and secondary outcomes together.

Acupuncture to treat breast engorgement: two studies with 293 women

Primary and secondary outcomes

Two studies examined the effects of acupuncture on breast engorgement (Kvist 2004; Kvist 2007). In both studies there were three treatment groups: advice and usual care (which might include the use of oxytocin nasal spray at the discretion of the midwife); advice and acupuncture, excluding the SP6 acupoint; and advice and acupuncture, including the SP6 point. Advice consisted of information on breastfeeding frequency, duration and technique, breast emptying, and the application of unrefined cotton wool as needed. Results for resolution of symptoms were very similar for women in the two acupuncture groups in the Kvist 2007 study, so we have combined them in the data tables.

We were unable to include data from the Kvist 2004 study in analyses because results were not set out separately for the three randomised groups in the published report and were not available from the authors. The authors however report that there were no significant differences on day three of treatment between the three groups in the severity index (a sum score for breast tension, erythema and pain) or for maternal satisfaction with breastfeeding. The percentage of mothers in Group 1 who were prescribed oxytocin nasal spray by the midwives was 86%. The study by Kvist 2004 was discontinued prematurely because the authors felt it necessary to include cultivation of breast milk from all participants and follow‐up of the mothers after six weeks. In Kvist 2007, the two intervention groups were combined during data analysis as suggested in section 16.5 of the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011). There was no difference in cessation of breastfeeding where six women stopped breastfeeding in the group where oxytocin nasal spray was used (the midwives gave oxytocin nasal spray to 100% of the mothers in Group 1) compared to three women in the group where acupuncture (excluding SP‐6 acupoint) was used (risk ratio (RR) 0.50, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.13 to 1.92; one study; 140 women ‐ data not shown).

Both studies provided information on the review's primary outcomes in the form of a severity index (SI), which included breast tension and pain. Significantly more mothers in the acupuncture group had less severe breast symptoms on days three and four of treatment in comparison with the non‐acupuncture group. The mothers' expression of satisfaction with the breastfeeding experience did not differ significantly between the groups.The number of women prescribed antibiotics may represent a proxy measure of mastitis; results from Kvist 2007 show that there was no difference between acupuncture and control groups in prescription antibiotics (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.32 to 1.16; data not shown).

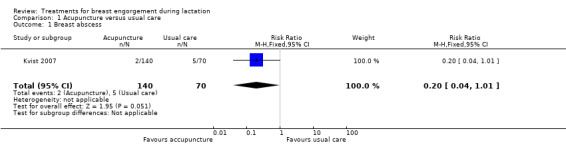

The number of women with breast abscess was reported in Kvist 2007; women in the acupuncture group were less likely to develop an abscess compared to women receiving routine care (RR 0.20, 95% CI 0.04 to 1.01; one study; 210 women), Analysis 1.1.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupuncture versus usual care, Outcome 1 Breast abscess.

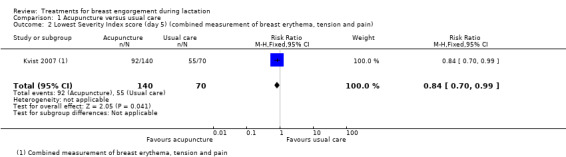

Findings in the Kvist 2007 study favoured the acupuncture group, with more women in the acupuncture group, having less severe symptoms on days four and five of contact, compared to women in the control group (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.99; one study; 210 women), Analysis 1.2.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupuncture versus usual care, Outcome 2 Lowest Severity Index score (day 5) (combined measurement of breast erythema, tension and pain).

A lower rate of pyrexia was observed in women who received acupuncture for breast engorgement compared to women receiving standard care (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.72 to 0.94; one study; 210 women), Analysis 1.3.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupuncture versus usual care, Outcome 3 Pyrexia (advised to take antipyrexials).

Acupressure versus hot and cold compresses: one study with 70 women

Primary and secondary outcomes

This study, comparing the effect of acupressure (intervention group) and intermittent hot and cold compresses (control group) (Ahmadi 2011), could not be analysed in RevMan 2014 because of the way data were presented (using individual breasts as the unit of analysis). Both treatments were found to be effective in decreasing breast engorgement in lactating mothers (P < 0.001), with hot and cold compresses being more effective than acupressure (P < 0.001).

Cabbage leaves to treat breast engorgement: three studies with 101 women

Primary and secondary outcomes

Three studies by the same first author examined cabbage leaves to reduce symptoms of breast engorgement, and collected information on pre‐ and post‐treatment pain scores in randomised trials. Two studies assessed the use of cabbage leaves: chilled versus room temperature cabbage leaves (Roberts 1995), and chilled cabbage leaves versus chilled gel packs (Roberts 1995a), whilst the third study evaluated the use of cabbage leaf extract, in the form of a cream, versus placebo (Roberts 1998). In two studies (Roberts 1995;Roberts 1995a), breasts rather than women were randomised, and results were not reported in a way that allowed us to enter data into RevMan 2014. In the study comparing chilled cabbage leaves and chilled gel packs (Roberts 1995a), it was reported that women in both groups had significant reductions in pain scores following treatment (30% for the cabbage leaves and 39% for the gel packs), but that there were no differences between groups (data not shown). While both treatments appeared to produce some alleviation of discomfort, it is likely that the subjective ratings on the pain ruler were susceptible to a placebo effect. Two‐thirds of women stated that they preferred the cabbage leaves because they gave a more immediate effect, while others felt that the chilled gel packs gave a more lasting effect. In the second study comparing chilled versus room temperature cabbage leaves, again authors reported that both groups had significantly less pain following treatment (37% reduction in pain with room temperature cabbage leaves and a 38% reduction with chilled cabbage leaves), but that there was no difference at all between the randomised groups (Roberts 1995) (data not shown). The lack of difference in the pain ratings suggests that chilling does not influence the purported effectiveness of cabbage leaves. Study authors felt that the drop in pain ratings could have been at least partially caused by a placebo effect. The attention of clinicians could have reduced anxiety in the new mothers and consequently reduced pain levels. Study authors concluded that it is not necessary to chill cabbage leaves before using them, since chilling has no effect on the efficacy of the treatment.

In Roberts 1998 there was no significant difference between the cabbage leaf extract group and the placebo group with regards to breast engorgement (mean difference (MD) 0.20, 95% CI ‐0.18 to 0.58; one study; 39 women; low‐quality evidence), Analysis 2.1. Both groups perceived the creams as having some efficacy but the lack of significant difference between the mean pain scores of the experimental and control groups (MD 0.40, 95% CI ‐0.67 to 1.47; one study; 39 women; low‐quality evidence), Analysis 2.2, on any of the indicators, suggests that any action of the cabbage leaf extract tested is likely to be a placebo effect. The perception of the control group mothers that the discomfort and hardness were decreasing supports this inference. Furthermore, the magnitude of this perceived relief was low and in the range of a placebo effect. Of note is that breastfeeding was observed to have significantly more effect than cabbage cream on the perception of hardness of breast tissue and discomfort (Roberts 1998).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Cabbage leaf extract versus placebo, Outcome 1 Breast engorgement (Hill and Humenich Breast engorgement scale).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Cabbage leaf extract versus placebo, Outcome 2 Breast pain (Bourbonaise pain scale).

Gua‐Sha (scraping) therapy versus hot packs and massage: one study with 54 women

Primary and secondary outcomes

In the study comparing Gua‐Sha (scraping) therapy with hot packs and massage (Chiu 2010), Gua‐Sha therapy, applied to acupoints ST16, ST18, SP17 and CV17, was more beneficial than hot packs and massage for the relief of breast engorgement, though both interventions significantly decreased breast temperature, engorgement, pain and discomfort at five and 30 minutes post‐treatment. There was marked difference in the intervention group at first five minutes post‐intervention: breast engorgement scale 4.01 (standard deviation (SD) 0.91) for the intervention group compared to 6.43 (SD: 1.17) for the hot packs and massage group (MD ‐2.42, 95% CI ‐2.98 to ‐1.86; one study; 54 women), Analysis 3.1. Breast pain was markedly improved at five minutes in the Gua‐Sha therapy group: 4.25 (SD: 1.07) compared to 6.26 (SD 1.14) in the control group (MD ‐2.01, 95% CI ‐2.60 to ‐1.42; one study; 54 women), Analysis 3.2. There was also marked improvement in the breast discomfort scales in the first five minutes in the Gua‐Sha therapy group (MD ‐2.33, 95% CI ‐2.81 to ‐1.85; one study; 54 women), Analysis 3.3.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Gua‐Sha therapy versus hot packs and massage, Outcome 1 Breast engorgement ‐ 5‐minute post‐intervention (Subjective Breast Engorgement Scale).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Gua‐Sha therapy versus hot packs and massage, Outcome 2 Breast pain ‐ 5‐minute post‐intervention (Subjective Breast Engorgement Scale).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Gua‐Sha therapy versus hot packs and massage, Outcome 3 Breast discomfort ‐ 5‐minute post‐intervention (Subjective Breast Engorgement Scale).

Ultrasound (thermal, continuous) treatment for breast engorgement: one study with 109 women

Primary and secondary outcomes

McLachlan 1991 examined ultrasound versus sham ultrasound in a study where breasts rather than women were randomised (women may have had active treatment on both breasts, sham treatment on both breasts, or one breast receiving active, and the other receiving sham ultrasound). No adjustment was made for the non‐independence of breasts and most of the results were difficult to interpret. When women who had the same treatment (either active or sham ultrasound) to both breasts were compared, the numbers requiring analgesia were very similar (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.51; one study; 45 women; low‐quality evidence), Analysis 4.1. Trial authors report that both sham and active treatment were associated with significant reductions in subjective ratings of pain and hardness, based on visual analogue scales comparing the paired pre‐treatment and post‐treatment ratings for each breast, but there were no differences between groups at the end of treatment. The effect of treatment on hardness, as measured by tonometry, was small and inconsistent providing further evidence of a placebo effect. It was also reported that there were no differences in the duration of breastfeeding (18 weeks) for women in the different treatment groups, but actual rates in each group were not reported. The therapeutic effect observed in both groups was attributed to the warmth, rest, massage, attention and emotional, practical and informational support provided by the physiotherapists in the course of treatment. In addition, the study authors thought that the perceived benefit of being the recipient of modern technology may have contributed to the observed placebo effect.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Ultrasound versus sham treatment, Outcome 1 Analgesic requirement.

Cold packs for breast engorgement: one study with 88 women

Primary and secondary outcomes

In a non‐blinded study women who had caesarean deliveries and who developed symptoms of breast engorgement were randomised to treatment and control groups (breast‐shaped cold packs worn in a halter versus routine care) (Robson 1990). Women in the intervention group seemed to experience a reduction in pain intensity post‐test. The author reported a decrease in mean pain intensity score from 1.84 (SD 0.65) to 1.23 (SD 0.68) compared with an increase in the control group from 1.50 (SD 0.71) to 1.79 (SD 0.72) (data not shown). However, the differences between groups at baseline, and the failure to observe randomisation (women with "heightened distress" were moved into the control group), make results difficult to interpret. It was not possible to include these results in the data and analyses.

Electromechancial massages and pumping: one study with 16 women

One study (Batista 2014) found a decrease in breast temperature (P = 0.0349) following electromechanical massage and pumping in comparison to manual methods; however, the alternating method of sequence generation, lack of blinding, and possible selective reporting, place this study at high risk of bias.

Protease complex to treat breast engorgement: one study with 59 women

Primary and secondary outcomes

A quasi‐randomised controlled trial by Murata 1965 examined the effects of protease complex (a plant enzyme) versus placebo in 59 women complaining of painful, swollen breasts, three to five days postpartum. Outcomes measured included improvements in pain and swelling, and overall rating of recovery. Additional observations recorded included size of breast and shape of nipple. Blood samples were taken before and after treatment to monitor coagulation factors (bleeding, coagulation and prothrombin time).

Women in the active treatment group were less likely to have no improvement in pain (RR 0.17, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.74; one study; 59 women), Analysis 5.1, and swelling (RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.79; one study; 59 women), Analysis 5.2, when symptoms were clinically assessed on the fourth day after commencement of treatment. Compared with controls, women receiving the active protease complex were also less likely to experience no overall change in their symptoms or worse symptoms (RR 0.26, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.56; one study; 59 women), Analysis 5.3.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Protease complex versus placebo, Outcome 1 Pain not improved.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Protease complex versus placebo, Outcome 2 Breast swelling not improved.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Protease complex versus placebo, Outcome 3 Overall rating of recovery (no change or worse).

It was not clear how many of the women participating in this trial were breastfeeding during the treatment period. No side effects were observed and coagulation factors were unchanged before and after treatment.

Oxytocin for the treatment of breast engorgement: one study with 45 women

Primary and secondary outcomes

A study carried out in the early 1950s examined the effectiveness of subcutaneous oxytocin, which was administered daily until symptoms resolved (Ingelman‐Sundberg 1953). Participants received either oxytocin or an injection of normal saline. The main outcome in this study was duration of treatment. Overall, seven of the 45 women included in the study still had symptoms three days after starting treatment; five of the 20 women in the oxytocin group and two of the 25 women in the placebo group. Although more women in the oxytocin group had no resolution of symptoms compared with controls, there was no difference between groups (RR 3.13, 95% CI 0.68 to 14.44; one study; 45 women), Analysis 6.1.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Oxytocin versus placebo, Outcome 1 Symptoms not subsided after three days of treatment.

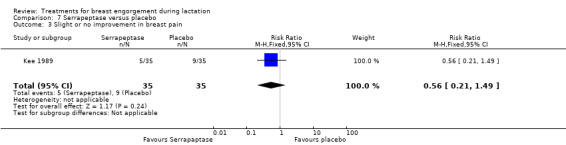

Serrapeptase versus placebo: one study with 70 women

Primary and secondary outcomes

A double‐blind randomised controlled trial by Kee 1989 examined the effects of oral serrapeptase, a proteolytic enzyme derived from the silk worm, on 70 women recruited from an urban hospital in Singapore diagnosed with breast engorgement. During the study breastfeeding was encouraged and concomitant breast massage and milk expression was allowed (Kee 1989).

A higher rate of improvement of breast engorgement was observed in the group receiving serrapeptase compared to placebo (RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.88; one study; 70 women), Analysis 7.1, however, there was no difference in the rate of improvement in breast swelling between groups (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.55; one study; 70 women), Analysis 7.2.

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Serrapeptase versus placebo, Outcome 1 Slight or no improvement in breast engorgement.

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Serrapeptase versus placebo, Outcome 2 Slight or no improvement in breast swelling.

Nor was any difference found in the rate of improvement of breast pain between the group of women receiving serrapeptase and the control group (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.21 to 1.49; one study; 70 women), Analysis 7.3.

7.3. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Serrapeptase versus placebo, Outcome 3 Slight or no improvement in breast pain.

Discussion

Summary of main results

In this review we have included data from 13 randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials, involving 919 breastfeeding women, looking at 10 different types of interventions for treating breast engorgement.

For several interventions with sham or placebo comparisons (ultrasound, cabbage leaf extract cream, and subcutaneous oxytocin), there was no evidence that interventions were associated with a more rapid or effective resolution of symptoms; in these studies women tended to have improvements in pain and other symptoms over time whether or not they received active treatment. The improvement in symptoms may be partly explained by the placebo effect or, it may be due to the fact that symptoms resolved spontaneously as women continued to breastfeed.

Non‐medical interventions

No differences were observed in the one study comparing acupuncture with usual care (advice and oxytocin spray) in terms of cessation of breastfeeding. In another study comparing cabbage leaf extract with placebo, no differences were observed in breast pain or breast engorgement. In one study comparing Gua‐Sha therapy with hot packs and massage, improvements were observed in both breast pain and breast engorgement. There was no difference between ultrasound and sham treatment in analgesic requirement.

Results from individual trials that could not be included in data analysis suggested that there were no differences between room temperature and chilled cabbage leaves and between chilled cabbage leaves and gel packs, with all interventions producing some relief. Intermittent hot/cold packs applied for 20 minutes twice a day were found to be significantly more effective than acupressure. Acupuncture did not improve maternal satisfaction with breastfeeding, but in one study women reported less severe symptoms and were less likely to develop a breast abscess. In another study, women who received breast‐shaped cold packs were more likely to experience a reduction in pain intensity than women who received usual care; however, the differences between groups at baseline, and the failure to observe randomisation, make this study at high risk of bias. One study found a decrease in breast temperature (P = 0.03) following electromechanical massage and pumping in comparison to manual methods; however, the alternating method of sequence generation, lack of blinding, and possible selective reporting, place this study at high risk of bias.

Medical interventions

Women treated with protease complex were less likely to have no improvement in pain and swelling on the fourth day of treatment and less likely to experience no overall change in their symptoms or worsening of symptoms. It should be noted that it is more than 40 years since the study was carried out, and we are not aware that this preparation is used in current practice. Subcutaneous oxytocin provided no relief at all in symptoms at three days. Serrapeptase was found to produce some relief in breast pain, induration and swelling, when compared to placebo, with a high number of participants given serrapeptase experiencing slight to no improvement in overall breast engorgement, swelling and breast pain, but differences were not significant.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

All available randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials investigating the treatment of breast engorgement in breastfeeding women were included in this review, with no language restrictions. We attempted to be as inclusive as possible by going to great lengths to contact authors of reports requiring clarification of methodology or results.

The studies included in this review were conducted in a variety of countries (Australia, Brazil, Iran, Japan, Singapore, Sweden, Taiwan, USA); however all but two were from high‐resource settings, hence limiting the applicability of the findings.