Abstract

Background

Perineal trauma, due to spontaneous tears, surgical incision (episiotomy), or in association with operative vaginal birth, is common after vaginal birth, and is often associated with postpartum perineal pain. Birth over an intact perineum may also lead to perineal pain. There are adverse health consequences associated with perineal pain for the women and their babies in the short‐ and long‐term, and the pain may interfere with newborn care and the establishment of breastfeeding. Aspirin has been used in the management of postpartum perineal pain, and its effectiveness and safety should be assessed. This is an update of the review, last published in 2017.

Objectives

To determine the effects of a single dose of aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid), including at different doses, in the relief of acute postpartum perineal pain.

Search methods

For this update, we searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth's Trials Register (4 October 2019), ClinicalTrials.gov, the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (4 October 2019) and screened reference lists of retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), assessing single dose aspirin compared with placebo, no treatment, a different dose of aspirin, or single dose paracetamol or acetaminophen, for women with perineal pain in the early postpartum period. We planned to include cluster‐RCTs, but none were identified. We excluded quasi‐RCTs and cross‐over studies.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed study eligibility, extracted data and assessed the risk of bias of the included RCTs. Data were checked for accuracy. The certainty of the evidence for the main comparison (aspirin versus placebo) was assessed using the GRADE approach.

Main results

We included 17 RCTs, 16 of which randomised 1132 women to aspirin or placebo; one RCT did not report numbers of women. Two RCTs (of 16) did not contribute data to meta‐analyses. All women had perineal pain post‐episiotomy, and were not breastfeeding. Studies were published between 1967 and 1997, and the risk of bias was often unclear, due to poor reporting.

We included four comparisons: aspirin versus placebo (15 RCTs); 300 mg versus 600 mg aspirin (1 RCT); 600 mg versus 1200 mg aspirin (2 RCTs); and 300 mg versus 1200 mg aspirin (1 RCT).

Aspirin versus placebo

Aspirin may result in more women reporting adequate pain relief four to eight hours after administration compared with placebo (risk ratio (RR) 2.03, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.69 to 2.42; 13 RCTs, 1001 women; low‐certainty evidence). It is uncertain whether aspirin compared with placebo has an effect on the need for additional pain relief (RR 0.25, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.37; 10 RCTs, 744 women; very low‐certainty evidence), or maternal adverse effects (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.57 to 2.06; 14 RCTs, 1067 women; very low‐certainty evidence), four to eight hours after administration. Analyses based on dose did not reveal any clear subgroup differences.

300 mg versus 600 mg aspirin

It is uncertain whether over four hours after administration, 300 mg compared with 600 mg aspirin has an effect on adequate pain relief (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.86; 1 RCT, 81 women) or the need for additional pain relief (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.12 to 3.88; 1 RCT, 81 women). There were no maternal adverse effects in either aspirin group.

600 mg versus 1200 mg aspirin

It is uncertain whether over four to eight hours after administration, 600 mg compared with 1200 mg aspirin has an effect on adequate pain relief (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.39; 2 RCTs, 121 women), the need for additional pain relief (RR 1.32, 95% CI 0.30 to 5.68; 2 RCTs, 121 women), or maternal adverse effects (RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.13 to 69.52; 2 RCTs, 121 women).

300 mg versus 1200 mg aspirin

It is uncertain whether over four hours after administration, 300 mg compared with 1200 mg aspirin has an effect on adequate pain relief (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.32; 1 RCT, 80 women) or need for additional pain relief (RR 2.00, 95% CI 0.19 to 21.18; 1 RCT, 80 women). There were no maternal adverse effects in either aspirin group.

None of the included RCTs reported on neonatal adverse effects.

No RCTs reported on secondary review outcomes of: prolonged hospitalisation due to perineal pain; re‐hospitalisation due to perineal pain; fully breastfeeding at discharge; mixed feeding at discharge; fully breastfeeding at six weeks; mixed feeding at six weeks; perineal pain at six weeks; maternal views; or maternal postpartum depression.

Authors' conclusions

Single dose aspirin may increase adequate pain relief in women with perineal pain post‐episiotomy compared with placebo. It is uncertain whether aspirin has an effect on the need for additional analgesia, or on maternal adverse effects, compared with placebo. We downgraded the certainty of the evidence because of study limitations (risk of bias), imprecision, and publication bias.

Aspirin may be considered for use in non‐breastfeeding women with post‐episiotomy perineal pain. Included RCTs excluded breastfeeding women, so there was no evidence to assess the effects of aspirin on neonatal adverse effects or breastfeeding.

Future RCTs should be designed to ensure low risk of bias, and address gaps in the evidence, such as the secondary outcomes established for this review. Current research has focused on women with post‐episiotomy pain; future RCTs could be extended to include women with perineal pain associated with spontaneous tears or operative birth.

Plain language summary

Aspirin (single dose) for relief of perineal pain after childbirth

What is the issue?

Can aspirin be given to women who experience perineal pain following childbirth to relieve the pain, without causing side effects for either the women or their babies?

Why is this important?

Many women experience pain in the perineum (the area between the vagina and anus) following childbirth. The perineum may be bruised or torn during childbirth, or have a cut made to help the baby to be born (an episiotomy). After childbirth, perineal pain can interfere with women's ability to care for their newborns and establish breastfeeding. If perineal pain is not relieved effectively, longer‐term problems for women may include painful sexual intercourse, pelvic floor problems resulting in incontinence, prolapse, or chronic perineal pain. Aspirin may be given to women who have perineal pain after childbirth, but its effectiveness and safety had not been assessed in a systematic review. This is an update of a review last published in 2017. This is part of a series of reviews looking at drugs to help relieve perineal pain in first few weeks after childbirth.

What evidence did we find?

We searched for evidence in October 2019, and included 17 randomised controlled studies, involving 1132 women, published between 1967 and 1997. All women had perineal pain following an episiotomy (usually within 48 hours after birth), and were not breastfeeding. The women received either aspirin (doses ranging from 300 mg to 1200 mg) or fake pills (placebo), by mouth. The methodological quality of the studies was often unclear. Two studies did not contribute any data for analyses.

Aspirin compared with placebo may increase adequate pain relief for mothers four to eight hours after administration (low‐certainty evidence). It is uncertain whether aspirin compared with placebo has an effect on the need for additional pain relief, or on adverse effects for mothers, in the four to eight hours after administration (both very low‐certainty evidence).

The effects of administering 300 mg versus 600 mg aspirin (1 study), 600 mg versus 1200 mg aspirin (2 studies), or 300 mg versus 1200 mg aspirin (1 study) are uncertain for adequate pain relief, the need for additional pain relief, or adverse effects for the mother.

No studies reported on adverse effects of aspirin for the baby, or other outcomes we planned to assess: prolonged hospital stay, or readmission to hospital due to perineal pain; perineal pain six weeks after childbirth, women's views, or postpartum depression.

What does this mean?

A single dose of aspirin may help with perineal pain following episiotomy for women who are not breastfeeding, when measured four to eight hours after administration.

We found no information to assess the effects of aspirin for women who are breastfeeding.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Aspirin compared with placebo for perineal pain in the early postpartum period.

| Aspirin compared with placebo for perineal pain in the early postpartum period | ||||||

|

Patient or population: women with perineal pain in the early postpartum period Settings: hospitals in USA, Venezuela, Belgium, Canada, India Intervention: aspirin (single dose) Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk for placebo | Corresponding risk for aspirin | |||||

|

Adequate pain relief as reported by the woman (4 to 8 hours) |

Study population | RR 2.03 (1.69 to 2.42) | 1001 (13 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | ||

| 253 per 1000 | 513 per 1000 (427 to 612) | |||||

|

Need for additional pain relief (4 to 8 hours) |

Study population | RR 0.25 (0.17 to 0.37) | 744 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b | ||

| 267 per 1000 | 67 per 1000 (45 to 99) | |||||

|

Maternal adverse effects (4 to 8 hours) |

Study population | RR 1.08 (0.57 to 2.06) | 1067 (14 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,c | ||

| 27 per 1000 | 29 per 1000 (15 to 55) | |||||

| Neonatal adverse effects | (0 RCTs) | Not reported by any of the included RCTs | ||||

| Perineal pain at six weeks postpartum | (0 RCTs) | Not reported by any of the included RCTs | ||||

| *The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect, and may change the estimate. Low certainty: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect, and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aWe downgraded 2 levels for very serious limitations in study design: most of the trials contributing data were at unclear risk of selection bias bWe downgraded 1 level for serious limitations in publication bias: visual inspection of funnel plot indicates likely publication bias cWe downgraded 1 level for serious limitations in imprecision: there were few events and wide 95% CI around the pooled estimate that includes no effect

Background

Description of the condition

Perineal trauma may result from naturally occurring tears, surgical incisions, such as episiotomy (cutting of the perineum to enlarge the vaginal opening during the second stage of labour), or in association with operative vaginal births (vacuum or forceps assisted births); and is frequently associated with acute perineal pain in the immediate postpartum period (Chou 2009). Birth over an intact perineum is also often associated with acute postpartum perineal pain. Perineal trauma is common, for example, in high‐income countries, such as Australia, only approximately one quarter (24%) of mothers have an intact perineum after vaginal birth, with over half of mothers having either a first or second degree laceration or vaginal graze (53%), and a smaller proportion having third or fourth degree lacerations (3%) or other types of lacerations (8%). Of the approximately one in five mothers (23%) having an episiotomy, approximately 42% have a laceration of some degree (AIHW 2019).

Short‐term morbidities for the mother arising from perineal trauma may include bleeding, infection, haematoma, and acute postpartum perineal pain, which may also interfere with newborn care and the establishment of breastfeeding (Chou 2009; East 2012a). In the longer‐term, women are at an increased risk of dyspareunia (painful sexual intercourse), pelvic floor problems, and chronic perineal pain (Chou 2009; East 2012a).

Various practices can impact on the extent of perineal trauma sustained during birth, and so can influence the degree of perineal pain experienced by the woman in the immediate postpartum period. Cochrane Reviews have shown antenatal digital perineal massage (Beckmann 2013), and the use of warm compresses on the perineum during the second stage of labour (Aasheim 2017), to be effective in preventing perineal trauma and associated pain (WHO 2018).

A variety of practices and agents have also been assessed for the relief of perineal pain in the immediate postpartum period. Cochrane Reviews have reported finding limited evidence to support routine use of local cooling (such as with ice packs or cold gel packs) of the perineum (East 2012b), or the application of topical local anaesthetics to the perineum for postpartum perineal pain relief (Hedayati 2005). Another Cochrane Review found some support for the use of paracetamol to reduce postpartum perineal pain, and decrease the need for additional pain relief. However, the overall quality of included studies was assessed as unclear, and adverse effects were not assessed (Chou 2013). Other practices and agents that have been systematically reviewed and shown to have varied effectiveness in relieving postpartum perineal pain include: methods and materials for suturing perineal tears or episiotomies, therapeutic ultrasound, and rectal analgesia (East 2012a; Hay‐Smith 1998; Hedayati 2003; Kettle 2012). For example, in regard to perineal suturing after childbirth, a Cochrane Review showed that continuous suturing techniques for perineal closure, compared with interrupted methods, are associated with less short‐term pain; if continuous suturing is used for all layers (vagina, perineal muscles and skin), the reduction of pain has been reported to be even greater (Kettle 2012).

Description of the intervention

The history of aspirin began thousands of years ago, with early uses of extracts from plants and herbs containing salicylates (Vane 2003). In the 1870s, it was demonstrated that salicin and salicylic acid from white willow bark could reduce fever, pain, and inflammation in people with rheumatic fever (Maclagan 1879). The success of salicylic acid prompted the German pharmaceutical manufacturer, Bayer, to search for a derivative that was equally, or more effective. Felix Hoffman, a young chemist at Bayer, motivated by his father's inability to take salicylic acid for his arthritis due to its adverse effects (particularly vomiting), found a way to acetylate the hydroxyl group on the benzene ring of salicylic acid to form acetylated salicylic acid (Vane 2003).

In the first decades of the 1900s, acetylsalicylic acid, or 'aspirin' was considered the supreme analgesic (pain reliever); for three quarters of the 20th century, its use was solely as an analgesic and antipyretic (fever reducing) agent (Vane 2003). In the 1970s and 1980s, as part of his Nobel Prize‐winning work, Sir John Vane demonstrated that aspirin could inhibit the formation of prostaglandins, associated with pain, fever, and inflammation, providing a physiological rationale for the effectiveness of one of the world's most widely used medication. As part of this work, Vane also discovered prostacyclin, an important prostaglandin that plays a vital role in the process of blood coagulation. The potential for aspirin to prevent a range of serious, life‐threatening conditions, including heart attacks and stroke, was recognised following this discovery (Smith 2014).

Aspirin is now considered to be one of the most effective and versatile medications in the world. It is commonly recommended to be taken in the lowest effective dose to avoid adverse effects secondary to higher doses. For example, low‐dose aspirin (75 mg to 150 mg daily) has been shown to provide substantial benefit for preventing serious cardiovascular events (heart attacks, stroke, and vascular death) in people with pre‐existing cardiovascular disease, or with a history of events (secondary prevention; ATT Collaboration 2002). In primary prevention, for people without a history of events or previous disease, the value of low‐ and high‐dose aspirin (75 mg to 500 mg daily) remains uncertain (ATT Collaboration 2009). There is increasing evidence that aspirin may reduce the risk of some cancers, and certain pregnancy complications. Long‐term low‐dose aspirin (at least 75 mg daily) has been shown to reduce colorectal cancer incidence and mortality (Rothwell 2010). Low‐dose aspirin is reported to have small‐to‐moderate benefits in preventing pre‐eclampsia and its consequences (Duley 2019): 75 mg daily is recommended for pregnant women at high risk of developing the condition (WHO 2011).

How the intervention might work

Perineal pain is transmitted primarily through the pudendal nerve, a somatic sensory and motor nerve that innervates the external genitalia, as well as the bladder and rectum sphincters (Cunningham 2005). Although a detailed description of the mechanism of action and pharmacology of aspirin is beyond the scope of this review, we have outlined the basic concepts.

The mechanisms by which aspirin exerts its analgesic, anti‐inflammatory, and antipyretic effects were discovered in the 1970s. Aspirin inhibits the activity of the cyclo‐oxygenase (COX) enzymes (irreversible inhibition of COX‐1 and modification of COX‐2), which play important roles in inflammation and nociceptive processes (the encoding and processing in the nervous system of noxious stimuli), such as through the formation of prostaglandins and thromboxanes (Vane 2003).

Through inhibiting these key enzymes, it has also been demonstrated that aspirin can prevent the production of physiologically important prostaglandins and thromboxanes, including those that protect the stomach mucosa from damage by hydrochloric acid, and those that aggregate platelets when required (Vane 2003). It is through these mechanisms that aspirin has been shown to cause adverse effects, such as gastrointestinal irritation and occult (hidden) blood loss (Derry 2012). The availability of alternative agents with improved tolerability has reduced the use of aspirin for pain relief over recent years, however, in many parts of the world, where alternatives are not available, or are more expensive, aspirin is still the most commonly used analgesic for many different pain conditions (Derry 2012; Vane 2003).

A Cochrane Review that included 67 trials (involving 5743 adults), which were assessed to be "overwhelmingly of adequate or good methodological quality", confirmed single‐dose aspirin (300 mg to 1200 mg) to be an effective analgesic for acute, postoperative, moderate to severe intensity pain (Derry 2012). Higher doses (900 mg to 1000 mg) were shown to be more effective, however, these doses were associated with increased adverse effects, including gastric irritation, nausea, vomiting, drowsiness, and dizziness. The pain relief achieved with aspirin was very similar to paracetamol given at the same dose (Derry 2012). Derry 2012 excluded trials in which pain was due to trauma, such as is often the case for women with acute perineal pain in the immediate postpartum period. It is considered plausible that aspirin may also be effective in relieving acute perineal pain in the early postpartum period after birth.

Why it is important to do this review

Perineal trauma is common after vaginal birth, and frequently associated with acute postpartum perineal pain; birth over an intact perineum is also often associated with perineal pain. Perineal pain may be associated with adverse health consequences for the mother and her baby in the short and long term, such as dyspareunia, pelvic floor problems, and chronic perineal pain, and may also interfere with newborn care, including the establishment of breastfeeding (Chou 2009; East 2012a).

There is currently a dearth of evidence on effective interventions to reduce acute perineal pain in the immediate postpartum period. Previous Cochrane Reviews have assessed practices and agents, including therapeutic ultrasound (Hay‐Smith 1998), rectal analgesia (Hedayati 2003), local cooling (East 2012b), topical anaesthetics (Hedayati 2005), paracetamol (Chou 2013), and most recently, non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory agents (Wuytack 2016), for the relief of perineal pain in the postpartum period. These reviews have reported mixed results. Therefore, it is important to establish if aspirin may be effective in relieving perineal pain and improving health outcomes for mothers and their babies. Because it is known that salicylate and salicylate metabolites, including aspirin, are excreted in breast milk, there is potential for effects on babies who are breast fed (NIH 2015). Therefore, adverse effects or harms for both mothers and their babies must be assessed.

We assessed the clinical effectiveness and adverse effects of aspirin given to relieve perineal pain in the early postpartum period. This review is one of a series of reviews of drugs for perineal pain in the early postpartum period, all based on the same generic protocol (Chou 2009). This protocol is published in the Cochrane Library, and describes the methods that shaped the production of all the reviews on drugs for perineal pain. It is available for consultation for prospective reviews undertaken on future drugs that may be introduced for this population and indication. This is an update of the review last published in 2017 (Molakatalla 2017).

Objectives

To determine the effects of a single dose of aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid), including at different doses, in the relief of acute postpartum perineal pain.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials, and had planned to include cluster‐randomised controlled trials. We excluded quasi‐randomised controlled trials and cross‐over trials. We planned to include studies published as abstracts only, as well as studies published in full‐text form.

Types of participants

All women with acute perineal pain in the early postpartum period; defined as the first four weeks after giving birth, or as defined by the authors of the studies.

Types of interventions

Single administration of aspirin, used to treat perineal pain due to spontaneous lacerations, episiotomy, or birth over an intact perineum, in the early postpartum period. We included studies in which aspirin was compared with a placebo or no treatment, and where different doses of aspirin (e.g. 75 mg, 300 mg, etc), administered as a single dose, were compared. We also planned to include studies where aspirin was compared with a single dose of paracetamol or acetaminophen for perineal pain in the early postpartum period.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Adequate pain relief, as reported by the woman*

Need for additional pain relief in the first 48 hours for perineal pain

Maternal adverse effects, composite of any of the following: nausea, vomiting, sedation, constipation, diarrhoea, drowsiness, sleepiness, gastric discomfort, psychological impact

Neonatal adverse effects, composite of any of the following: vomiting, sedation, constipation, diarrhoea, drowsiness, sleepiness

* Determined by more than 50% relief of pain, stated by the woman or calculated using a formula; see Data collection and analysis for details.

Secondary outcomes

Prolonged hospitalisation due to perineal pain

Rehospitalisation due to perineal pain

Fully breastfeeding at discharge

Mixed feeding at discharge

Fully breastfeeding at six weeks

Mixed feeding at six weeks

Perineal pain at six weeks

Maternal views (using a validated questionnaire)

Maternal postpartum depression

Search methods for identification of studies

The methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth.

Electronic searches

For this update, we searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register by contacting their Information Specialist (4 October 2019).

The Register is a database containing over 25,000 reports of controlled trials in the field of pregnancy and childbirth. It represents over 30 years of searching. For full current search methods used to populate Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register, including the detailed search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, and CINAHL; the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service, please follow this link.

Briefly, Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register is maintained by their Information Specialist, and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE Ovid;

weekly searches of Embase Ovid;

monthly searches of CINAHL EBSCO;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Two people screen the search results, and review the full text of all relevant trial reports, identified through the searching activities described above. Based on the intervention described, they assign each trial report a number that corresponds to a specific Pregnancy and Childbirth review topic (or topics), and then add it to the Register. The Information Specialist searches the Register for each review using this topic number, rather than keywords. This results in a more specific search set that has been fully accounted for in the relevant review sections (Included studies; Excluded studies; Studies awaiting classification).

We also searched ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP; 4 October 2019) for unpublished, planned, and ongoing trial reports, using the terms given in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We searched for further studies in the reference lists of the studies identified.

We did not apply language or date restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For methods used in the previous version of this review, seeMolakatalla 2017.

For this update, we used the following methods to assess the reports that were identified as a result of the updated search.

The following methods section is based on both the generic protocol (Chou 2009) and a standard template used by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth.

Assessment of pain

The number of women achieving adequate pain relief was defined as one of the following.

The number of women reporting 'good' or 'excellent' pain relief, when asked about their level of pain relief four to six hours after receiving their allocated treatment (the data were extracted as dichotomous data).

The number of women who reported 50% pain relief, or greater.

The number of women who achieved 50% pain relief, or greater, as calculated by using derived pain relief scores (TOTPAR (total pain relief), or SPID (summed pain intensity differences)) over four to six hours.

It is common to use categorical or visual analogue scales for pain intensity, and to calculate the results for each participant, over periods of four or six hours, as SPID or TOTPAR (Moore 1996). From these categorical scales, it was possible to convert results into dichotomous data (the proportion of participants achieving at least 50%, or greater, max TOTPAR) using standard formulae (Moore 1996; Moore 1997b). Converting data in this way enabled us to use these data in a meta‐analysis (Moore 1997a; Moore 1997b). We used the following equations to estimate the proportions of women who achieved at least 50% of maximum TOTPAR.

1. Proportion with greater than 50% maxTOTPAR = (1.33 x mean % maxTOTPAR – 11.5)

With % maxTOTPAR = mean TOTPAR x 100/(maximum score x number of hours)

2. Proportion with greater than 50% maxTOTPAR = (1.36 x mean % maxSPID – 2.3)

With % maxSPID = mean SPID x 100/(maximum score x number of hours)

We then calculated the number of participants achieving at least 50% maxTOTPAR, by multiplying the proportions of participants with at least 50% maxTOTPAR by the total number of participants in the treatment groups. We then used the number of participants with at least 50% maxTOTPAR to calculate the relative benefit and number needed to treat to benefit.

Where studies used more than one method of calculating adequate pain relief, preferences for analyses and reporting purposes, in order of decreasing preference, were: i) the proportion with at least 50% maxTOTPAR calculated using SPID; ii) the proportion with at least 50% maxTOTPAR calculated using TOTPAR; and iii) the number of participants reporting 'good' or 'excellent' pain relief/number of participants reporting at least 50% pain relief. We also assessed the number of participants who re‐medicated in four to eight hours, as well as the median time to re‐medication, if data were available.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion, all potential studies we identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion, or if required, we consulted a third review author.

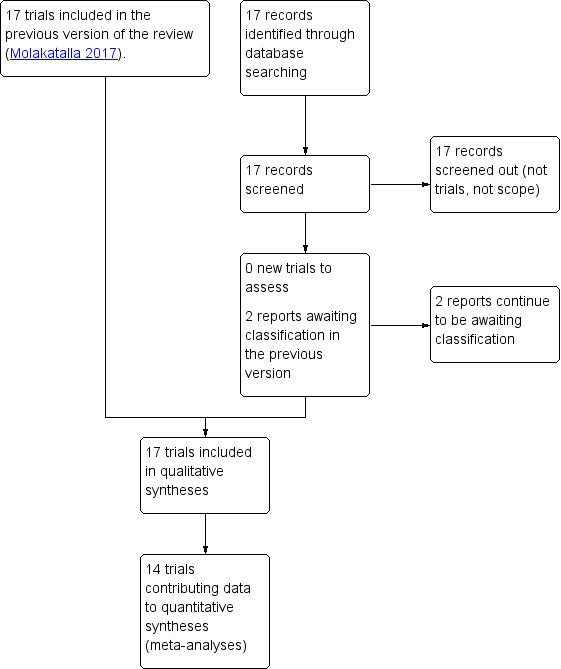

We created a study flow diagram to illustrate the number of records identified, included, and excluded (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. At least two review authors extracted data using the agreed form for eligible studies. We resolved discrepancies through discussion, or if required, consultation with another member of the review author team. We entered data into Review Manager 5 software and checked for accuracy (Review Manager 2014). When information regarding any steps was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreement by discussion, or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

For each included study, we described the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital, or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

For each included study, we described the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment, and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes; alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

For each included study, we described the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding would be unlikely to affect results.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high, or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high, or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

For each included study, we described the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high, or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

For each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, we described the completeness of data, including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported, and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion, where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we planned to re‐include missing data in the analyses.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received, from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

For each included study, we described how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it was clear that all of the study’s prespecified outcomes, and all expected outcomes of interest to the review were reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s prespecified outcomes were reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified; outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so could not be used; study failed to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by points (1) to (5)

For each included study, we described any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias, including: was the trial stopped early due to some data‐dependent process? Was there extreme baseline imbalance? Did someone claim the study was fraudulent?

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

low risk of other bias;

high risk of other bias;

unclear whether there was risk of other bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to points (1) to (6), we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias, and whether we considered them likely to impact the findings. We planned to assess the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

We presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals for dichotomous data.

Continuous data

We planned to use the mean difference if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We planned to use the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measured the same outcome, but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We planned to include cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with individually‐randomised trials. If we include cluster‐randomised trials in future updates, we will adjust their sample sizes using the methods described in the Handbook, using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial, or from a study of a similar population (Higgins 2011). If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this, and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs, and the interaction between the effect of the intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit, and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Cross‐over trials

We considered cross‐over trials to be inappropriate for this research question, and excluded them.

Multi‐armed trials

We included all the relevant intervention groups (aspirin) and control groups (placebo) from multi‐arm trials. We excluded other arms that were not relevant to this review.

Dealing with missing data

We noted levels of attrition for the included studies. We planned to explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect, by conducting sensitivity analyses.

We carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis for all outcomes. That is, we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and all participants were analysed in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome, in each trial, was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in meta‐analyses using the Tau², I², and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial, if an I² was greater than 30%, and either a T² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (P < 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

Because there were 10 or more studies included in the meta‐analyses for 'Adequate pain relief as reported by the woman', 'Need for additional pain relief', and 'Maternal adverse effects', we investigated reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We assessed funnel plot asymmetry visually.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using Review Manager 5 software (Review Manager 2014). We used fixed‐effect methods for combining data because we assumed that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect.

In future updates of this review, if there is clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or if we detect substantial statistical heterogeneity, we will use the random‐effects method to produce an overall summary. We will treat the random‐effects summary as the average of the range of possible treatment effects, and discuss the clinical implications of treatment effects differing among trials. If the average treatment effect is not clinically meaningful, we will not combine trials. If we use the random‐effects model in future updates, we will present the results as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, and the estimates of Tau² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If we had identified substantial heterogeneity, we planned to investigate possible sources, using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We planned to consider whether an overall summary was meaningful, and if it was, use the random‐effects model to produce the effect.

We planned to carry out the following subgroup analyses:

primiparous versus multiparous women;

women with perineal trauma versus women who gave birth over intact perineum; and

dose of aspirin (i.e. low‐dose versus high‐dose).

However, due to the absence of relevant data in the included trials, we were able to conduct analyses based on dose only.

Subgroup analyses were restricted to the review's primary outcomes with reported data.

We assessed subgroup differences by interaction tests available in Review Manager 2014. We reported the results of subgroup analyses quoting the Chi² statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to conduct sensitivity analyses to explore the effects of risk of bias on the outcomes. We planned to explore the effects of trial quality assessed by allocation concealment and random sequence generation (considering selection bias), by omitting studies rated at high or unclear risk of bias for these components. However, because we assessed all included trials at unclear bias for at least one of these two components, we did not conduct a sensitivity analysis.

We also planned to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit (individual versus cluster) on the outcomes, and the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data. We planned to explore the effects of fixed‐effect or random‐effects models for outcomes with statistical heterogeneity, and the effects of any assumptions made, such as the value of the ICC used for cluster‐randomised trials. However, because we did not include any cluster‐randomised trials, trials with high levels of missing data, or identify outcomes with substantial statistical heterogeneity, we did not conduct sensitivity analyses.

We planned to use only primary outcomes in sensitivity analyses.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We assessed the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach, as outlined in the GRADE Handbook, in order to assess the certainty of the body of evidence relating to the following outcomes, for the main comparison: aspirin versus placebo (GRADE Handbook).

Adequate pain relief as reported by the woman

Need for additional pain relief in the first 48 hours for perineal pain

Maternal adverse effects, composite of any of the following: nausea, vomiting, sedation, constipation, diarrhoea, drowsiness, sleepiness, gastric discomfort, psychological impact

Neonatal adverse effects, composite of any of the following: vomiting, sedation, constipation, diarrhoea, drowsiness, sleepiness

Perineal pain at six weeks postpartum

However, we could only assess the certainty of the evidence for the first three outcomes, as we had no data from the included trials for outcomes 4 and 5.

We used GRADEpro GDT to import data from Review Manager 5, in order to create ’Summary of findings’ tables (GRADEpro GDT; Review Manager 2014). We produced a summary of the intervention effect and a measure of certainty for each of the above outcomes, using the GRADE approach. The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) to assess the certainty of the body of evidence for each outcome. The evidence can be downgraded from 'high certainty' by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments for risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates, or potential publication bias.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

There were no new studies identified in the 2019 updated search (see Figure 1).

Two studies (two records) await classification: in both studies, the method of allocation was not clearly reported (Bhounsule 1990; Sunshine 1989).

Included studies

Settings and dates

We included 17 studies (22 reports) in this review. All were reported to be randomised controlled trials.

Most (11 trials) were conducted in the USA (Bloomfield 1967; Bloomfield 1970a; Bloomfield 1970b; Bloomfield 1974; Friedrich 1983; Jain 1978a; Jain 1978b; Jain 1985; London 1983a; London 1983b; Okun 1982), three in Venezuela (Olson 1997; Sunshine 1983a; Sunshine 1983b), and one each in Belgium (Devroey 1978), Canada (Trop 1983) and India (Mukherjee 1980).

Only two of the included trials reported their dates; Bloomfield 1967 was conducted between December 1965 and April 1966, and London 1983b was conducted between July and December 1980. Of the remaining 15 trials, six were published in the 1970s (Bloomfield 1970a; Bloomfield 1970b; Bloomfield 1974; Devroey 1978; Jain 1978a; Jain 1978b); eight in the 1980s (Friedrich 1983; Jain 1985; London 1983a; Mukherjee 1980; Okun 1982; Sunshine 1983a; Sunshine 1983b; Trop 1983); and one in the 1990s (Olson 1997).

Participants and sample sizes

In total, there were 1132 women in the aspirin and placebo arms of 16 of the 17 included trials, with 617 women randomised to receive aspirin, and 515 to a placebo. Three trials only reported the numbers analysed (not randomised; (Devroey 1978; London 1983a; London 1983b)), and one trial dot report the number of women at all (Trop 1983). The sample sizes of the trials (including only the relevant arms) ranged from 26 (Bloomfield 1970b), to 178 (Mukherjee 1980). We reported the number of women in arms of the trials not included in our analyses in the 'Characteristics of included studies' tables.

All included trials included women with perineal pain in the early postpartum period, post‐episiotomy. One trial recruited and randomised women on the first postoperative morning (Mukherjee 1980), two within 24 hours of birth (Bloomfield 1967; Bloomfield 1970b), one from 16 to 48 hours following induction of anaesthesia (Friedrich 1983), six within 48 hours of birth (Bloomfield 1970a; Bloomfield 1974; Devroey 1978; Jain 1978a; London 1983a; Okun 1982); and seven trials did not specify a time period following birth (Jain 1978a; Jain 1985; London 1983b; Olson 1997; Sunshine 1983a; Sunshine 1983b; Trop 1983). We did not identify any trials that assessed perineal pain associated with naturally occurring tears, or birth over an intact perineum. The intensity of women's pain following episiotomy varied among the included trials; eight trials included women with moderate or severe pain (Bloomfield 1967; Devroey 1978; Friedrich 1983; Jain 1978a; London 1983a; London 1983b; Mukherjee 1980; Sunshine 1983b); three included women with moderate to very severe pain (Bloomfield 1970a; Bloomfield 1974; Okun 1982); one included women with mild to severe pain (Bloomfield 1970b); one included women with at least moderate pain (Jain 1985); and three included women with severe pain (Jain 1978b; Olson 1997; Sunshine 1983a). One trial did not specify pain intensity (Trop 1983). Most trials clearly specified that breastfeeding was an exclusion criterion, and excluded women with known sensitivity or allergy to aspirin, and women who had recently received analgesia.

Interventions and comparisons

Only one trial had two trial arms, comparing aspirin and placebo (Bloomfield 1970b). Another trial compared only aspirin and placebo, but had four trial arms (London 1983b). The remaining 15 trials had between three and five trial arms, and in addition to aspirin, assessed a number of other agents for perineal pain in the early postpartum period. These agents included chlorphenesin 400 mg, 800 mg, and combination aspirin 300 mg and chlorphenesin 400 mg (Bloomfield 1967); flufenisal 300 mg and 600 mg (Bloomfield 1970a); ibuprofen 300 mg and 900 mg (Bloomfield 1974); diflunisal 125 mg, 250 mg, and 500 mg (Devroey 1978), etodolac 25 mg and 100 mg (Friedrich 1983), piroxicam 20 mg and 40 mg (Jain 1978a); combination aspirin 800 mg and caffeine 64 mg (Jain 1978b); indoprofen 50 mg and 100 mg (Jain 1985); fluproquazone 100 mg and 200 mg (London 1983a); dipyrone 500 mg (Mukherjee 1980); fendosal 100 mg, 200 mg, and 400 mg (Okun 1982); potassium 25 mg, 50 mg, and 100 mg (Olson 1997); zomepirac and ibuprofen (Sunshine 1983a); flurbiprofen 25 mg, 50 mg, and 100 mg (Sunshine 1983b); and tiaprofenic acid 200 mg and 400 mg (Trop 1983). For the purposes of the review, we analysed only the aspirin and placebo arms from the included trials.

Fifteen trials included comparisons of aspirin and placebo only; the single, oral doses of aspirin in these were 500 mg (Mukherjee 1980), 600 mg (Bloomfield 1967; Devroey 1978; Jain 1985; Sunshine 1983a; Sunshine 1983b), 648 mg (Jain 1978a), 650 mg (Friedrich 1983; Jain 1978b; London 1983a; Okun 1982; Olson 1997), 900 mg (Bloomfield 1974), and 1200 mg (Bloomfield 1970b). Three trials included two or more aspirin arms (in addition to a placebo arm); Bloomfield 1970a and Trop 1983 compared 600 mg and 1200 mg aspirin, and London 1983b compared 300 mg, 600 mg, and 1200 mg aspirin. The number of aspirin and placebo tablets (and dose of the tablets) taken varied across the trials.

Outcomes

We were a able to extract and meta‐analyse some measure of 'Adequate pain relief as reported by the woman' four to eight hours after drug administration from 13 trials. Data from four trials were not presented in a way that enabled us to include them in the meta‐analysis (Jain 1978a; Jain 1978b; Okun 1982; Trop 1983).

Three trials in the meta‐analysis provided data on adequate pain relief four hours after taking the medication (London 1983b; Olson 1997; Sunshine 1983a); two trials reported this outcome after five hours (Bloomfield 1970b; Jain 1985); seven trials after six hours (Bloomfield 1967; Bloomfield 1974; Devroey 1978; Friedrich 1983; London 1983a; Mukherjee 1980; Sunshine 1983b); and one trial after eight hours (Bloomfield 1970a). SPID scores were used to calculate the number of women with adequate pain relief for the meta‐analysis in 11 trials; (Bloomfield 1967; Bloomfield 1970a; Bloomfield 1970b; Bloomfield 1974; Devroey 1978; Friedrich 1983; Jain 1985; London 1983b; Olson 1997; Sunshine 1983a; Sunshine 1983b), one used total pain relief (TOTPAR) scores (Mukherjee 1980), and one used the number of women reporting pain relief to be good or excellent (London 1983a).

Five trials provided both summed pain intensity differences (SPID) and TOTPAR scores (Friedrich 1983; Jain 1985; Olson 1997; Sunshine 1983a; Sunshine 1983b); two trials provided both SPID scores, and the number of women reporting pain relief to be good or excellent (Friedrich 1983; Jain 1985); and five reported SPID scores and the number of women with at least 50% pain relief (or similar; (Bloomfield 1970a; Bloomfield 1970b; Bloomfield 1974; Devroey 1978; Mukherjee 1980)). In these cases, we used SPID data to calculate the number of women with adequate pain relief, and include in the meta‐analysis. In some cases, the number of women with adequate pain relief according to these different measures did not match, and the reasons for discrepancies were not entirely clear, particularly in numbers of women with adequate pain relief, calculated using the SPID versus TOTPAR scores.

Data on the need for additional analgesia, which could be included in a meta‐analysis, were available from 10 trials (Bloomfield 1970a; Bloomfield 1974; Devroey 1978; Jain 1978a; Jain 1985; London 1983a; London 1983b; Olson 1997; Sunshine 1983a; Sunshine 1983b); 14 trials reported data on any maternal adverse effects suitable for meta‐analysis (Bloomfield 1967; Bloomfield 1970a; Bloomfield 1974; Devroey 1978; Friedrich 1983; Jain 1978a; Jain 1978b; Jain 1985; London 1983a; London 1983b; Mukherjee 1980; Olson 1997; Sunshine 1983a; Sunshine 1983b).

Two trials did not provide any data that could be meta‐analysed (Okun 1982; Trop 1983).

None of the 17 included trials reported on any of the prespecified secondary outcomes.

Funding sources

Two of the trials reported support or funding solely from the National Institutes of Health (Bloomfield 1967), and the United Stated Public Health Service and National Heart Institute (Bloomfield 1970b). Ten of the trials reported at least partial support from pharmaceutical companies or commercial medical research organisations: Merck Sharp and Dohme Research Laboratories (Bloomfield 1970a; Devroey 1978); the Upjohn Company (Bloomfield 1974; Sunshine 1983b); American Home Products, Ives Laboratories and Wyeth Laboratories (Jain 1978b); Adria Laboratories (Jain 1985); Sandoz Inc. (London 1983a); the Ciba‐Geigy Corporation (Olson 1997); Boots Pharmaceuticals (Sunshine 1983b); and Roussel Canada Inc. (Trop 1983). Five of the trials did not report any sources of support or funding (Friedrich 1983; Jain 1978a; London 1983b; Mukherjee 1980; Okun 1982).

Declarations of interests

None of the 17 included trials provided specific declarations of interest for the manuscript authors. We noted that three of the trials had author(s) with affiliations to pharmaceutical companies or commercial medical research organisations: Merck Sharp and Dohme Research Laboratories (Devroey 1978); Analgesic Development Ltd. (Olson 1997); and Roussel Canada Inc. (Trop 1983).

Excluded studies

We excluded 10 studies (11 records) for the following reasons: five trials included mixed populations of women with postpartum pain (such as uterine cramping), and did not report results separately for women with perineal pain (Bruni 1965; Gruber 1979; Moggian 1972; Sunshine 1983c; Sunshine 1985); one was not randomised (Santiago 1959); three assessed combination agents (not aspirin alone; (Gindhart 1971; Prockop 1960; Rubin 1984)); and one assessed twice daily aspirin rather than single dose aspirin (Van der Pas 1984).

Risk of bias in included studies

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item presented as percentages across all included studies

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias" item for each included study

Allocation

We judged that only two trials applied adequate sequence generation methods; both used computer‐generated random sequences (Olson 1997; Sunshine 1983b). The remaining 15 trials did not report the methods used for random sequence generation, and simply reported that the women were randomised.

We judged all included trials at unclear risk of selection bias; none of them reported methods of allocation concealment.

Blinding

Of the 17 trials, we judged 14 at low risk of both performance and detection bias; women and study personnel (who were also the outcome assessors) were blinded by using identical placebos. We judged three trials at unclear risk of performance and detection bias, because although the trials were reported to be double‐blind, they provided no information on the nature of the placebos used, for us to determine if blinding was successfully achieved (Friedrich 1983; Jain 1978a; Jain 1978b).

Incomplete outcome data

We judged only three trials at low risk of attrition bias, with no losses, or exclusions (Bloomfield 1970b; Jain 1985; Mukherjee 1980).

We assessed five trials as unclear risk of attrition bias, largely due to unclear reporting regarding any losses and exclusions, reasons for missing data, or both (Friedrich 1983; Jain 1978a; Jain 1978b; London 1983a; Trop 1983).

We assessed nine trials at high risk of attrition bias (Bloomfield 1967; Bloomfield 1970a; Bloomfield 1974; Devroey 1978; London 1983b; Okun 1982; Olson 1997; Sunshine 1983a; Sunshine 1983b). In eight, the trial authors imputed data (i.e. for women requesting additional analgesia, trial authors either used women's pre‐treatment pain intensity or relief scores for all subsequent hours, or used the last observation carried forward method for subsequent hours), which may have introduced bias; in one trial, women who requested additional analgesia were excluded from the analyses, which may have similarly introduced bias (Bloomfield 1967).

Selective reporting

We assessed 12 trials as unclear risk of reporting bias, since we had no access to trial protocols or registrations to confidently assess the risk of selective reporting (Bloomfield 1967; Bloomfield 1970a; Bloomfield 1970b; Bloomfield 1974; Friedrich 1983; Jain 1985; London 1983a; London 1983b; Mukherjee 1980; Okun 1982; Olson 1997; Sunshine 1983b).

We assessed five trials at high risk of reporting bias (Devroey 1978; Jain 1978a; Jain 1978b; Sunshine 1983a; Trop 1983). In all five, some of outcome data and results were reported incompletely in the text, which meant, we were unable to extract these data for a meta‐analysis. For example: "The three drugs were much the same for mean onset, duration, and time to peak values. The hypothesis that there is no difference among treatments was rejected at the 0.05 level or better for all variables" (Sunshine 1983a).

The 17 trials reported very few outcome data.

Other potential sources of bias

We assessed nine trials at low risk of other potential sources of bias (Bloomfield 1967; Bloomfield 1970a; Jain 1978a; Jain 1985; Mukherjee 1980; Okun 1982; Olson 1997; Sunshine 1983a; Sunshine 1983b). We assessed eight trials as unclear risk of other bias (Bloomfield 1970b; Bloomfield 1974; Devroey 1978; Friedrich 1983; Jain 1978b; London 1983a; London 1983b; Trop 1983). These trials did not report baseline characteristics in a way that enabled us to assess comparability among groups (with no baseline characteristics reported, or lack of detail reported); one trial reported that most baseline characteristics were similar between groups "However, body weight was not similar in all treatment groups" (Bloomfield 1970a).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Comparison 1. Aspirin versus placebo for perineal pain

Fifteen of the 17 included trials contributed data to meta‐analyses in this comparison (Bloomfield 1967; Bloomfield 1970a; Bloomfield 1970b; Bloomfield 1974; Devroey 1978; Friedrich 1983; Jain 1978a; Jain 1978b; Jain 1985; London 1983a; London 1983b; Mukherjee 1980; Olson 1997; Sunshine 1983a; Sunshine 1983b). Two trials did not provide any data that could be meta‐analysed (Okun 1982; Trop 1983).

Primary outcomes

Adequate pain relief, as reported by the woman

Over four to eight hours after drug administration, aspirin compared with placebo may increase adequate pain relief (risk ratio (RR) 2.03, 95% confidence intervals (CI) 1.69 to 2.42; 13 trials, 1001 women; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.1). Visual inspection of the funnel plot for this outcome suggested no clear evidence of reporting bias (Figure 4).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Aspirin versus placebo for perineal pain, Outcome 1: Adequate pain relief as reported by the woman

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Aspirin versus placebo for perineal pain, outcome: 1.1 Adequate pain relief as reported by the women

Data from the trials not included in the meta‐analysis

Jain 1978a: "By all measurements of drug effect... aspirin 648 mg [was] significantly (P < 0.01) superior to placebo in [its] overall analgesic effect and also at second, third and fourth hours after dosing".

Jain 1978b: "In comparing 650 mg aspirin with placebo, we detected no significant difference at 1, 2, or 3 hr, but at the fourth hour we noted trends toward significant in favour of aspirin (P < 0.10) by each Kruskal‐Wallis analysis for pain analogue, pain intensity, and pain relief scores. The corresponding analysis of covariance at hour 4 showed differences in favour of aspirin for both pain analogue and pain intensity scores (P < 0.02)".

Okun 1982: "In patients with either uterine cramp or episiotomy pain, aspirin... provided greater pain relief (lower mean pain intensity scores) than did placebo from the 2nd through the 8th study hour".

Trop 1983: "When compared to placebo both patient's self‐rating scale and nurse's impression scale have shown a significant reduction in pain following treatment... with ASA".

Need for additional pain relief in the first 48 hours, for perineal pain

It is uncertain whether aspirin compared with placebo has an effect on the need for additional analgesia over four to eight hours after drug administration (RR 0.25, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.37; 10 trials, 744 women; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.2). Visual inspection of the funnel plot for this outcome indicated possible evidence of reporting bias, which could be due to some smaller trials producing exaggerated intervention effect estimates (Figure 5).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Aspirin versus placebo for perineal pain, Outcome 2: Need for additional pain relief

5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Aspirin versus placebo for perineal pain, outcome: 1.2 Need for additional pain relief

Data from the trials not included in the meta‐analysis

Bloomfield 1967: not reported; although one woman in the aspirin group was reported to have been "withdrawn owing to distressing pain unrelieved by the study drugs" compared with no women in the placebo group.

Okun 1982: "The proportion of patients requiring additional analgesic was significantly different... Approximately 71% of patients in the placebo group needed additional analgesic as compared with... 48% in the aspirin group" (these data related to women with uterine cramp or episiotomy pain).

Trop 1983 "None of the patients on… ASA required any additional analgesic during the 4‐hour observation period, but four patients in the placebo group required supplementary medication for pain" (the denominators for each group were not reported).

Maternal adverse effects

It is uncertain whether aspirin compared with placebo has an effect on overall maternal adverse effects over four to eight hours after administration (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.57 to 2.06; 14 trials, 1067 women; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.3). Visual inspection of the funnel plot for this outcome suggested no clear evidence of reporting bias (Figure 6).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Aspirin versus placebo for perineal pain, Outcome 3: Maternal adverse effects

6.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Aspirin versus placebo for perineal pain, outcome: 1.3 Maternal adverse effects

Data from the trials not included in the meta‐analysis

Okun 1982: "The incidence of side effects was not significantly different among the treatment groups... Three patients each in the placebo group... and 5 patients in the aspirin group reported side effects" (these data related to women with uterine cramp or episiotomy pain).

Trop 1983: one woman receiving 1200 mg aspirin (dizziness), no women receiving 600 mg aspirin and two women receiving placebo (nausea) experienced side effects (the denominators for each group were not reported).

Neonatal adverse effects

None of the included trials reported on the primary outcome: neonatal adverse effects.

Subgroup analyses based on dose

We integrated subgroup analyses based on dose, into the main analyses, comparing trials using 300 mg, 500 to 650 mg, 900 mg, and 1200 mg aspirin. We observed no clear subgroup differences based on dose of aspirin for 'Adequate pain relief as reported by the woman (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 0.75, P = 0.86, I² = 0%; Analysis 1.1); 'Need for additional pain relief' (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 0.63, P = 0.89, I² = 0%; Analysis 1.2); or 'Maternal adverse effects' (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 3.76, df = 2 (P = 0.15), I² = 46.8%; Analysis 1.3).

Secondary outcomes

None of the included trials reported on any of the secondary review outcomes: prolonged hospitalisation due to perineal pain; re‐hospitalisation due to perineal pain; fully breastfeeding at discharge; mixed feeding at discharge; fully breastfeeding at six weeks; mixed feeding at six weeks; perineal pain at six weeks; maternal views (using a validated questionnaire); maternal postpartum depression.

Comparison 2. 300 mg aspirin versus 600 mg aspirin for perineal pain

London 1983b contributed data to this comparison.

Primary outcomes

Adequate pain relief as reported by the woman

It is uncertain whether, over four hours after administration, 300 mg has an effect on adequate pain relief, compared with 600 mg aspirin (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.86; 1 trial, 81 women; Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: 300 mg aspirin versus 600 mg aspirin for perineal pain, Outcome 1: Adequate pain relief as reported by the woman

Need for additional pain relief in the first 48 hours for perineal pain

It is uncertain whether, over four hours after administration, 300 mg has an effect on the need for additional pain relief, compared with 600 mg aspirin (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.12 to 3.88; 1 trial, 81 women; Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: 300 mg aspirin versus 600 mg aspirin for perineal pain, Outcome 2: Need for additional pain relief

Maternal adverse effects

There were no adverse effects reported among women who received 300 mg or 600 mg aspirin (Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2: 300 mg aspirin versus 600 mg aspirin for perineal pain, Outcome 3: Maternal adverse effects

Neonatal adverse effects

London 1983b did not report on the primary outcome: neonatal adverse effects.

Secondary outcomes

London 1983b did not report on any of the secondary review outcomes.

Comparison 3. 600 mg aspirin versus 1200 mg aspirin for perineal pain

Bloomfield 1970a and London 1983b contributed data to this comparison.

Primary outcomes

Adequate pain relief as reported by the woman

It is uncertain whether, over four to eight hours after administration, 600 mg has an effect on adequate pain relief, compared with 1200 mg aspirin (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.39; 2 trials, 121 women; Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3: 600 mg aspirin versus 1200 mg aspirin for perineal pain, Outcome 1: Adequate pain relief as reported by the woman

Need for additional pain relief in the first 48 hours for perineal pain

It is uncertain whether, over four to eight hours after administration, 600 mg has an effect on the need for additional pain relief, compared with 1200 mg aspirin (RR 1.32, 95% CI 0.30 to 5.68; 2 trials, 121 women; Analysis 3.2).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3: 600 mg aspirin versus 1200 mg aspirin for perineal pain, Outcome 2: Need for additional pain relief

Maternal adverse effects

It is uncertain whether, over four to eight hours after administration, 600 mg has an effect on maternal adverse effects compared with 1200 mg aspirin (RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.13 to 69.52; 2 trials, 121 women; Analysis 3.3).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3: 600 mg aspirin versus 1200 mg aspirin for perineal pain, Outcome 3: Maternal adverse effects

Neonatal adverse effects

Bloomfield 1970a and London 1983b did not report on the primary outcome: neonatal adverse effects.

Secondary outcomes

Bloomfield 1970a and London 1983b did not report on any of the secondary review outcomes.

Comparison 4. 300 mg aspirin versus 1200 mg aspirin for perineal pain

London 1983b contributed data to this comparison.

Primary outcomes

Adequate pain relief as reported by the woman

It is uncertain whether, over four hours after administration, 300 mg has an effect on adequate pain relief, compared with 1200 mg aspirin (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.32; 1 trial, 80 women; Analysis 4.1).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4: 300 mg aspirin versus 1200 mg aspirin for perineal pain, Outcome 1: Adequate pain relief as reported by the woman

Need for additional pain relief in the first 48 hours for perineal pain

It is uncertain whether, over four hours after administration, 300 mg has an effect on the need for additional pain relief, compared with 1200 mg aspirin (RR 2.00, 95% CI 0.19 to 21.18; 1 trial, 80 women; Analysis 4.2).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4: 300 mg aspirin versus 1200 mg aspirin for perineal pain, Outcome 2: Need for additional pain relief

Maternal adverse effects

There were no adverse effects among women who received 300 mg or 1200 mg aspirin (Analysis 4.3).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4: 300 mg aspirin versus 1200 mg aspirin for perineal pain, Outcome 3: Maternal adverse effects

Neonatal adverse effects

London 1983b did not report on the primary outcome: neonatal adverse effects.

Secondary outcomes

London 1983b did not report on any of the secondary review outcomes.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We included 17 trials; of these, 16 randomised 1132 women to single dose aspirin or placebo for perineal pain in the early postpartum period. Fifteen trials contributed data to four comparisons (aspirin versus placebo; 300 mg versus 600 mg aspirin; 600 mg versus 1200 mg aspirin; 300 mg versus 1200 mg aspirin).

Low‐certainty evidence from 13 trials (1001 women) suggested that women receiving aspirin (doses ranging from 300 mg to 1200 mg) may have an increase in adequate pain relief at four to eight hours after administration compared with placebo (a 105% relative increase, from 25% in the placebo group to 47% in the aspirin group). We were unable to include data from four trials in our meta‐analysis for this outcome (Jain 1978a; Jain 1978b; Okun 1982; Trop 1983). Individual results indicated a benefit from aspirin when compared with placebo. The effects of different doses of aspirin on adequate pain relief, as reported by the women were uncertain (in comparisons of 300 mg and 600 mg (1 trial, 81 women), 600 mg and 1200 mg (2 trials, 121 women), and 300 mg and 1200 mg (1 trial, 80 women)).

Very low‐certainty evidence from 10 trials (744 women) suggested that the effect of aspirin (doses ranging from 300 mg to 1200 mg) compared with placebo was uncertain for reducing the need for additional analgesia for perineal pain over four to eight hours after administration. Individual effects of different doses of aspirin (300 mg and 600 mg (1 trial, 81 women), 600 mg and 1200 mg (2 trials, 121 women), and 300 mg and 1200 mg (1 trial, 80 women)) were also uncertain on the need for additional pain relief.

Very low‐certainty evidence from 14 trials (1067 women) also suggested that the effect of aspirin (doses ranging from 300 mg to 1200 mg) compared with placebo was uncertain for maternal adverse effects over four to eight hours after administration. Individual effects of different doses of aspirin (300 mg and 1200 mg aspirin (2 trials, 121 women)) on maternal adverse effects was also uncertain.

None of the included trials reported on the review primary outcome ‐ neonatal adverse effects, nor any of the secondary review outcomes: prolonged hospitalisation due to perineal pain; re‐hospitalisation due to perineal pain; fully breastfeeding at discharge; mixed feeding at discharge; fully breastfeeding at six weeks; mixed feeding at six weeks; perineal pain at six weeks; maternal views (using a validated questionnaire); and maternal postpartum depression.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The included trials enrolled women with perineal pain in the early postpartum period, post‐episiotomy. Accordingly, results may not be applicable to other women with perineal pain, such as those with pain following naturally occurring tears, or birth over an intact perineum. All included trials compared aspirin with placebo; we were unable to assess the comparative effects of aspirin versus paracetamol, as proposed in the protocol for this review.

Most trials recruited women from the USA (11 trials); three trials were conducted in Venezuela, and one each in Belgium, Canada, and India. Sixteen trials were published before the 1990s (one in the 1960s, six in the 1970s, and nine in the 1980s). Results may not be applicable to all settings or countries worldwide, nor to current clinical practice.

Although there were more than 1000 women and their babies in the included trials, individually, sample sizes were small, ranging from 26 to 178 women. Most trials reported on the review primary outcomes adequate pain relief as reported by the woman (N = 13), need for additional analgesia (N = 10), and maternal adverse effects (N = 14). The included trials only examined three (of 13) prespecified outcomes; there were no data reported for the primary outcome ⎯ neonatal adverse effects ⎯ or for any of the secondary review outcomes.

Breastfeeding was clearly stated as an exclusion criterion in most trials, and as a result, no data were available to determine any neonatal adverse effects or effects on breastfeeding. Guidance for the management of perineal pain, including in breastfeeding women, recommends that if oral analgesia is required, then paracetamol or acetaminophen should be used first, unless contraindicated; if paracetamol is not effective, an oral or rectal non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory (NSAID) agent, such as ibuprofen, should be considered in the absence of contraindications (NICE 2015; NIH 2015; Reece‐Stremtan 2017). Although some guidance indicates that low‐dose aspirin may be considered as an antiplatelet drug for use in breastfeeding women (Bell 2011), it is generally recommended it be used cautiously, or avoided during breastfeeding, because salicylate and salicylate metabolites are excreted in breast milk. Therefore, there is potential for adverse effects in infants. Longer‐term, high‐dose administration of maternal aspirin has been associated with a report of infant metabolic acidosis, and aspirin administration to infants with viral infections has been associated with Reye's syndrome (NIH 2015).

It is recognised that breastfeeding is an unequalled way to provide the ideal food for infants. International guidance, including from the World Health Organization, recommends (where possible) initiation of breastfeeding within the first hour after birth, and exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life, for optimal growth, development, and health, followed by age‐appropriate complementary feeding alongside breastfeeding, for two years or more (WHO 2001; WHO 2003). Therefore, the evidence in this review is not directly applicable to current globally recommended best practice.

Quality of the evidence

Many aspects relating to risk of bias were unclear for several of the included trials (Figure 2; Figure 3). Except for one included trial, all studies were published before the 1990s. We found a lack of methodological detail provided in published reports. Attempts to contact trial authors to obtain additional information were unsuccessful. Of the 17 included trials, we assessed 15 as unclear risk of selection bias, because study reports did not provide detailed methods for sequence generation. We judged all trials as unclear risk of selection bias; because study reports did not provide detailed methods for concealment of allocation. We assessed 14 trials at low risk of performance and detection bias; we judged the risk as unclear for three trials. We judged most trials as unclear or high risk of attrition bias (a number imputing data); and all as unclear or high risk of reporting bias, with many of them reporting very limited outcome data; none had available trial registration or protocols.

We assessed the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach, as outlined in the GRADE Handbook, for prespecified outcomes analysed in the main comparison (aspirin versus placebo; (GRADE Handbook). We assessed that the certainty of the evidence was low (adequate pain relief as reported by the women), or very low (need for additional pain relief; maternal adverse effects). Our judgements were based on design limitations in the included trials (all outcomes), possible publication bias (need for additional pain relief), and imprecision (maternal adverse effects). See Table 1.

Potential biases in the review process

We took steps to minimise the introduction of bias during the review process. At least two review authors independently assessed trials for inclusion, performed data extraction, and assessed risk of bias for each of the included trials.

The Information Specialist of Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth conducted a detailed, systematic search process, without language or publication status restrictions, to reduce the risk for potential publication bias. We also searched trial registries for unpublished, planned, or ongoing trials. It is possible that additional trials assessing aspirin for perineal pain in the early postpartum period have been published but not identified; and that further trials have been conducted but are not yet published; or both. Should any such studies be identified in the future, we will assess these for inclusion in future updates of this review.

We investigated reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots for our primary outcomes. Although we found no clear evidence of reporting bias for 'adequate pain relief as reported by the women', and 'maternal adverse effects', the funnel plot for 'need for additional pain relief' demonstrated some asymmetry. This could indicate possible reporting bias, with the smaller published trials reporting exaggerated intervention effect estimates, and the possibility of additional small trials (including those reporting smaller effect estimates) remaining unpublished.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews