Abstract

Introduction

In breast cancer, early identification of distant metastasis changes management. Current guidelines recommend radiological staging in patients with a preoperative positive axilla; no guidelines address a preoperative negative axilla with subsequent positive sentinel lymph node biopsy. This study investigates whether current guidelines adequately identify distant metastasis in a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy population that had radiological staging.

Materials and methods

Patients diagnosed with primary breast cancer between 1 January 2013 and 1 October 2017 with a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy and subsequent radiological staging from a single unit were included. A systematic search identified relevant guideline criteria, against which patients were audited.

Results

A total of 330 patients with positive sentinel lymph node biopsy were identified; 227 (69%) had radiological staging postoperatively with computed tomography (5.3%), bone scan (2.6%) and both (92%) which identified 8/227 (3.5%) patients had distant metastasis. Patients with distant metastasis (DMp) compared with those without distant metastasis (NDMp) were associated with poorly differentiated tumours (DMp 62% vs NDMp 28%; p = 0.037), high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DMp 75% vs NDMp 39%; p = 0.043) and increased mean invasive tumour size (DMp 37mm vs NDMp 24mm; p = 0.014). Binomial logistic regression did not identify any characteristics to predict distant metastasis in staged patients (chi-squared p = 0.162). Two guidelines used postoperative results to inform radiological staging decision; 68/227 (30%) of staged patients met these guideline criteria, five of eight patients with distant metastasis did not meet current guideline criteria for radiological staging.

Discussion

Over 50% of patients with distant metastasis did not meet current guideline criteria for radiological staging and would have remained undiagnosed if current guidelines were followed. This study had an acceptable detection rate of 3.5% for distant metastasis. We therefore recommend radiological staging in all patients with positive sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Keywords: Breast neoplasms, metastasis, Sentinel lymph node biopsy

Introduction

Breast cancer remains the most common cancer to affect women in the world, with a significant mortality, causing 6.6% of all cancer deaths.1 Around 5–9% of patients will present with distant metastasis,2 common sites being brain, bone, lung, liver and distant lymph nodes. Early identification of metastatic disease is crucial, as management of these patients is markedly different to those without distant metastatic disease, is likely to involve fewer invasive procedures and is necessary for prognostic information for the patient.3

The understanding of the tumour biology mediating distant metastasis in breast cancer is evolving, but there remains no reliable prognostic marker or investigation to predict a tumour’s propensity for metastatic spread,4 so there is no accurate method for predicting which patients either have distant metastasis at presentation or will go on to develop distant metastasis. Preoperative clinical staging based on the T(umour) N(ode) M(etastasis) system composed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) can be useful in determining those at risk, and pathological analysis to reveal tumour biology types associated with distant metastasis can inform decision making with regards to investigation.5–7 The Royal College of Radiologists suggests that radiological staging investigations should be carried out with computed tomography (CT) covering the supraclavicular fossa, chest and liver and/or bone scan and, less commonly, positron emission CT (PET-CT).8

Most guidelines are united in recommending radiological staging for any patients who have symptoms indicative of distant metastasis,8–10 but the recommendations for staging in asymptomatic patients is less clear. Staging for distant metastasis in all asymptomatic patients with breast cancer is unnecessary, with a low rate of detection in those with low-stage disease,11 and so is a poor use of resources and exposes patients to unnecessary investigations and radiation with no obvious survival benefit.8,12 However, the recent advances in imaging such as the ready availability of CT and treatments available for those with metastatic breast cancer such as biological therapies mean that previous studies investigating the risk or cost benefit analysis of radiological staging for distant metastasis may not be relevant in today’s practice.3 Determining the optimal detection rate for distant metastasis is unclear from the literature. In one study, a surveyed group of physicians considered that a detection rate of 1% in a staging group was necessary to recommend using modality of imaging routinely,13 whereas in another study a distant metastasis detection rate of 6% in a staging group was not high enough to warrant the authors recommending the group for routine radiological staging.11 This is likely to be one of the reasons for variations in recommendations between guidelines, and possibly a reason why none of the guidelines have been widely adopted; one UK study demonstrated a large variance in practice in recommending radiological staging for distant metastasis.14

A number of guidelines focus their recommendations of radiological staging on preoperative (clinical) staging. The American Society of Clinical Oncology and UK based National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends staging in symptomatic patients and those with clinical stage III or IV disease only.9,10 In the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines, it is recommended that all patients with a preoperative positive axilla have radiological staging.6 It is also common practice for those with a negative preoperative axilla undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy to have radiological staging prior to treatment initiation. There are few recommendations based on postoperative, pathological staging which may differ from the preoperative clinical staging, particularly with regards to axillary involvement. A preoperative negative axilla will undergo sentinel lymph node biopsy and, in around 25–30% of cases, there are metastasis within the axillary lymph nodes and the patient will be deemed to have a positive axilla.15–17 Axillary nodal positivity is a known risk factor for developing distant metastasis.18–20 One guideline that includes postoperative findings is the Clinical Advice to Cancer Alliances for the Provision of Breast Cancer Services, who recommend staging those with four or more positive lymph nodes or cancers greater than 50mm.21 No guidelines give recommendations on whether patients should have radiological staging based on having a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy.

There is a lack of guidance or evidence on whether patients with a preoperative negative axilla who have a postoperative positive sentinel lymph node biopsy should undergo radiological staging to investigate for distant metastasis. In our centre, like in many UK centres,14 there is not a strict staging protocol but these patients are considered for radiological staging. This retrospective study aimed to identify this subgroup of patients from a single centre and determine which of them were staged and the rate of distant metastasis detection. Current guidelines which offer advice applicable to this population of patients are identified, and guidance applied to our population to investigate whether these guidelines appropriately identify patients with distant metastasis.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

All patients diagnosed with breast cancer at the Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital from 1 January 2013 and 1 October 2017 were retrospectively identified from a local prospectively gathered database after local audit approval (reference number 17-3219). Patients who underwent sentinel lymph node biopsy were identified and those who did not complete treatment at the institution, had primary axillary node clearance, or preoperative radiological staging were excluded. After exclusions, information was collected from current clinical systems on postoperative pathology diagnosis, radiological investigations and relevant further management decisions.

All patients were discussed individually at the weekly multidisciplinary team meeting. Local protocol is that all patients with a preoperative negative axilla and positive sentinel lymph node biopsy are considered for staging, however the decision as to whether a patient is recommended radiological staging is made on an individual basis by the multidisciplinary team based on all clinical information. The local radiological staging protocol is for CT of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis, and a bone scan, in line with national recommendations.8

Sentinel lymph nodes containing either macro or micro metastasis were defined as positive sentinel lymph node biopsy in this study (definitions as per AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook),5 those containing only isolated tumour cells were defined as a negative sentinel lymph node biopsy. Follow-up was until 1 July 2019 or death, and was ascertained from lack of reattendance. Disease specific mortality was defined as patients dying with a diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer.

If metastatic disease was identified, a change in management plan was defined as a cancellation of a planned surgical operation, a change in chemotherapy regimen that had previously been planned, or establishing a chemotherapy regimen with palliative intent, with explicit reference to the radiological staging results as a reason in the clinical notes.

Identification of relevant guidelines

A search was performed on Google, Google scholar and MEDLINE using search terms: guideline AND breast cancer (title) AND radiol* (abstract). The Association of Breast Surgeons guidance platform, which highlights relevant guidelines, was also reviewed. From these sources titles and abstracts, articles identified as guidelines from recognised organisations were then reviewed and guidelines including advice on radiological staging for distant metastasis based explicitly on postoperative findings were selected. An audit was performed of the study population against these guidelines to determine if guideline recommendations were successful in picking up patients with distant metastasis.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected on Microsoft Excel spreadsheets. Continuous data are described as mean (plus or minus standard deviation). Statistical analysis was with SPSS version 25. Statistical analysis of individual patient characteristics was with Mann–Witney U test for non-parametric data, chi-square test for percentages and unpaired, two-tailed T-test for continuous, parametric data. Data of staged patients were used to perform binomial logistic regression to see if any characteristics could predict the outcome of distant metastasis. Statistical significance was assessed by chi-squared goodness of fit test, variance described by Nagelkerke R square and the cut value was set to 0.5, that is that the probability of a case being positive had to be greater than 0.5 to be classified as positive. Significance levels were set to p less than 0.05.

Results

Patient identification

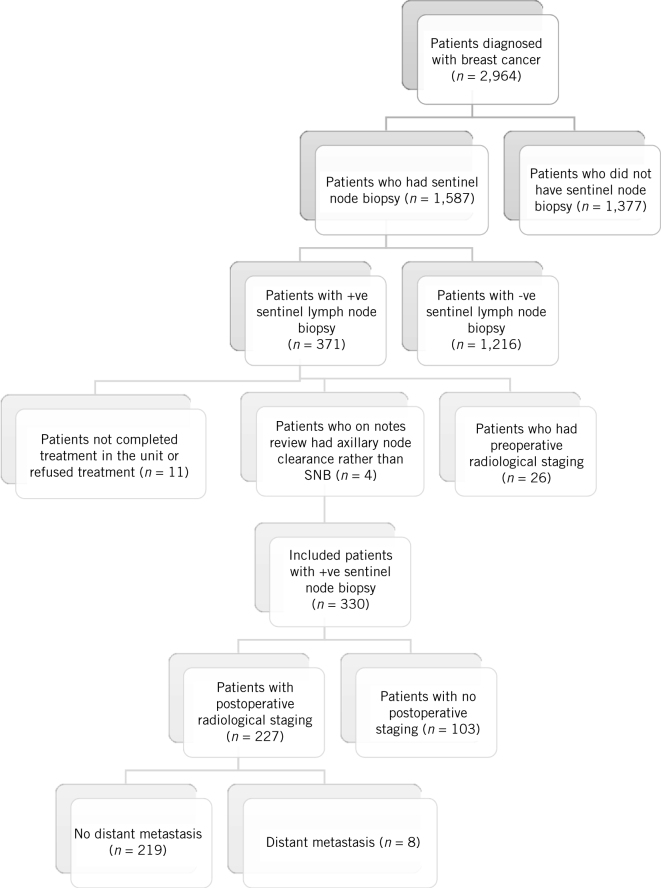

There were 2,964 patients diagnosed with breast cancer within the study period. A total of 1,587 of these patients had a sentinel lymph node biopsy, of whom 371 (23%) were positive. After exclusions (preoperative radiological staging n = 26, initial axillary node clearance n = 4, not completed treatment in the unit n = 11), the study population was 330. Figure 1 demonstrates the flow diagram of patient identification.

Figure 1.

Identification of the relevant population of patients of patients with a negative preoperative axilla who had a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy (SNB; n = 330), the number that had radiological staging (n = 227), and the number of patients with distant metastasis (n = 8)

Some 227 (69%) patients had postoperative radiological staging. 207 (92%) complied with the local guidelines for radiological staging and had both CT of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis and a bone scan, while 12 (5.3%) had CT only and 6 (2.6%) had a bone scan only. The reasons for noncompliance with local radiological guidelines were not documented by the multidisciplinary team.

Staging investigation outcomes

Of the total, 219 patients had radiological staging and were found not to have metastasis: 4.5% (10/219) had incidental findings (false positives) on radiological staging, with a total of 13 radiological abnormalities identified (5 lung nodules, 3 adrenal nodules, 2 skull bone abnormalities, 1 renal abnormality, 1 thyroid abnormality and 1 renal tumour), and had a total of 12 additional radiological investigations due to these abnormalities (4 CT, 2 magnetic resonance imaging, MRI, of the adrenal, 2 PET-CT, 2 skull plain x-ray, 1 ultrasound of the thyroid, 1 MRI of the brain) and 1 additional invasive biopsy (of renal tumour). Ultimately, none of these radiological abnormalities required immediate treatment and did not change patient management.

The metastatic detection rate in those with radiological staging was 3.5% (8/227). Metastases were to liver only (2/8), bone only (2/8), lung only (1/8), lung and liver mets (1/8), liver and bone (2/8). One patient with liver metastasis only had tissue biopsy confirmation, all other metastatic diagnoses were based on radiological staging findings and confirmed with subsequent PET-CT. All bone metastasis were identified on CT as abnormalities, but bone scan confirmed the metastatic nature of these abnormalities.

All eight patients with distant metastasis had a change in management plan due to the detection of distant metastasis. Five of the eight had a change in surgical management as a result of the diagnosis (either a further breast or axillary operation that had initially been planned was cancelled due to the findings of distant metastasis) and all eight had different chemotherapy regimens as a result of the diagnosis.

Patient tumour characteristics

Patient, tumour and axillary characteristics of patients who had radiological staging, those who did not, and those with distant metastasis are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient, tumour and axillary lymph node characteristics. Patients who had radiological staging (St) are compared with those that did not have radiological staging at presentation (NSt). Patients who had radiological staging and found to have distant metastasis at presentation (DMp) are compared with patients who had radiological staging and did not have distant metastasis (NDMp). Ordinal data described as number of patients with percentages in parentheses, continuous data as mean (± standard deviation, SD). Not significant (NS; p > 0.05). Significance set at p < 0.05%.

| St (n = 227) | NSt (N = 103) | p-value | DMp (n = 8) | NDMp (N = 219) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics: | ||||||

| Mean age (years) | 60 (± 13) | 66 (± 15) | 0.001 | 56 (± 12) | 60 (± 13) | NS |

| Female sex | 224 (99%) | 101 (98%) | NS | 8 (100%) | 216 (99%) | NS |

| Route of referral: | ||||||

| Symptomatic | 156 (68%) | 70 (68%) | NS | 6 (75%) | 150 (68%) | NS |

| Screening | 71 (32%) | 33 (32%) | NS | 2 (25%) | 69 (32%) | NS |

| Breast tumour characteristics: | ||||||

| Multifocal tumours | 61 (27%) | 19 (18%) | NS | 3 (38%) | 58 (27%) | NS |

| Invasive grade: | ||||||

| Well differentiated | 22 (10%) | 13 (12%) | NS | 0(0%) | 22 (10%) | NS |

| Moderately differentiated | 131 (58%) | 60 (58%) | NS | 3 (38%) | 128 (58%) | NS |

| Poorly differentiated | 67 (29%) | 25 (24%) | NS | 5(62%) | 62 (28%) | 0.037 |

| Associated with ductal carcinoma in situ | 169 (74.4%) | 75 (72%) | NS | 7 (87%) | 162 (74%) | NS |

| Low grade | 7 (3%) | 12 (11%) | NS | 0 (0%) | 7 (3%) | NS |

| Medium grade | 70 (30%) | 26 (25%) | NS | 1 (12%) | 69 (31%) | NS |

| High grade | 92 (40.5%) | 37 (35%) | NS | 6 (75%) | 86 (39%) | 0.043 |

| Receptor status: | ||||||

| ER/PR+, HER2– | 194 (85%) | 88 (85%) | NS | 7 (87.5%) | 187 (85%) | NS |

| ER/PR+, HER2+ | 18 (8%) | 10 (10%) | NS | 0 | 18 (8%) | NS |

| ER/PR–, HER2+ | 1 (0.4%) | 2 (2%) | NS | 0 | 1 (0.5%) | NS |

| ER/PR–, HER2– (triple negative) | 14 (6%) | 3 (3%) | NS | 1 (12.5%) | 13 (6%) | NS |

| Mean invasive tumour size (mm) | 24 (± 15) | 23 (± 14) | NS | 37.7 (± 19) | 23.9 (± 15) | 0.014 |

| Mean whole tumour size (mm) | 30 (± 18) | 27 (± 16) | NS | 42(± 16) | 29.6 (± 18) | NS |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 111 (48%) | 33 (32%) | 0.004 | 5 (62%) | 106 (48%) | NS |

| Axillary characteristics: | ||||||

| Macrometastasis | 210 (92%) | 27 (26%) | < 0.001 | 8 (100%) | 202 (92%) | NS |

| Micrometastasis | 17 (7%) | 75 (72%) | < 0.001 | 0 (0%) | 17 (8%) | NS |

| Mean number of +ve sentinel lymph node biopsies | 1.4 (± 0.8) | 1.08 (± 0.4) | < 0.001 | 1.8 (± 0.7) | 1.45 (± 0.8) | NS |

| Survival characteristics: | ||||||

| All-cause mortality | 13 (5.7%) | 13 (12.6%) | 0.031 | 3 (37%) | 10 (4.6%) | < 0.001 |

| Disease-specific mortality | 9 (3.9%) | 3 (2.9%) | NS | 3 (37%) | 6 (2.7%) | < 0.001 |

| Length of follow-up (months) | 58 (± 15) | 45 (± 18) | NS | 40 (± 20) | 48 (± 15) | NS |

Statistical comparison between patients who had staging (St; n = 227) and patients who did not (NSt; n = 103) revealed that patients who had staging were significantly younger (mean age St 60 years vs NSt 66 years, p = 0.001) and were more likely to have lymphovascular invasion (St 48% vs NSt 32%; p < 0.004), macrometastasis in the positive sentinel lymph node biopsy (St 92% vs NSt 26%, p < 0.001) and the mean number of positive sentinel lymph node biopsy was higher (St 1.4 vs NSt 1.08, p < 0.001). All-cause mortality was higher in the non-staged group (St 5.7% vs NSt 12.6%; p = 0.031) but disease specific mortality was not significantly different (St 3.9% vs NSt 3.2%, p > 0.05).

Statistical comparison was then performed between those that had distant metastasis diagnosed on radiological staging (dDMp); n = 8) compared with those patients who had radiological staging and did not have distant metastasis (NDMp; n = 219). Patients with distant metastasis were significantly more likely to have poorly differentiated invasive disease (DMp 62% vs NDMp 28%; p = 0.037), be associated with high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS; DMp 75% vs NDMp 39%; p = 0.043) and had increased mean invasive tumour size (DMp 37mm vs NDMp 24mm; p = 0.014). Patients with distant metastasis had higher all-cause mortality (DMp 37% vs NDMp 4.6%; p < 0.001) and disease specific mortality (DMp 37% vs NDMp 2.7%; p < 0.001).

Binomial logistic regression of all patient, tumour and axillary characteristics in those patients that were staged could not predict which patients had distant metastasis. It was not statistically significant (chi-squared goodness of fit test 17.8 (p = 0.162) and did not reveal any characteristics that reached statistical significance in the prediction model. The model explained 28.8% of variance (Nagelkereke R square test) in patients who were staged and achieved an overall accuracy of 96.9%. Although it achieved 100% specificity, it was poor at predicting distant metastasis with poor sensitivity of 12.5%, only correctly predicting one patient with distant metastasis, with seven patients with distant metastasis predicted incorrectly (Table 2).

Table 2.

Classification output of binomial logistic regression prediction model comparing those who had radiological staging with distant metastasis with those with radiological staging without distant metastasis. Cut value = 0.5.

| Observed | Predicted | |

|---|---|---|

| Distant metastasis | No distant metastasis | |

| Distant metastasis | 1 | 7 |

| No distant metastasis | 0 | 219 |

Identification of relevant guidelines

Only two guidelines were identified that provided specific advice on radiological staging based on postoperative pathological features; ESMO guidelines, advising radiological staging in patients with tumour greater than 50mm,6 and the Clinical Advice to Cancer Alliances for the Provision of Breast Cancer Services, advising radiological staging in patients with tumour greater than 50mm and four or more positive axillary lymph nodes.21 The study population was audited against these two parameters; 30% (68/227) of staged patients would have been recommended for radiological staging under the guideline criteria (Table 3). Of patients with distant metastasis, 63% (5/8) would not have been recommended radiological staging under guideline criteria (Fig 2). No patients with distant metastasis had symptoms indicative of distant metastasis at the time of detection.

Table 3.

Number and percentage of patients with a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy who had radiological staging that meet the current guideline criteria to recommend radiological staging

| Guideline parameters | Patients meeting the criteria (n) (n = 227) | Complying with guidelines for staging (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Tumour > 50mm | 28 | 12 |

| Lymph nodes ≥ 4 | 33 | 14 |

| Both | 7 | 3 |

| Total | 68 | 30 |

Figure 2.

Patients who had distant metastasis on radiological staging (n = 8) who would have been recommended radiological staging under guideline recommendations based on tumour greater than 50mm (dots) (2/8), four or more positive axillary lymph nodes (filled; 1/8) or did not meet the guideline recommendation (hatched; 5/8)

Discussion

There is a paucity of evidence or clinical guidelines on whether patients with a preoperative negative axilla who have a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy require radiological staging. We present a cohort of these patients, of whom the majority underwent postoperative radiological staging which detected distant metastasis in 3.5% of patients. Over 50% of these patients with distant metastasis would not have been recommended radiological staging under current relevant clinical guidelines, and so would not have had their metastatic disease diagnosed. Our data suggest that routine radiological staging of patients with a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy has an acceptable distant metastasis detection rate, and that the threshold for recommending staging in current clinical guidelines is too high.

Patients diagnosed with distant metastasis at presentation displayed some different characteristics compared with those without distant metastasis. Patients with distant metastasis had significantly more poorly differentiated tumours and were associated with higher-grade DCIS, which is unsurprising as these are markers of more aggressive tumour types that are more likely to metastasise. It should be noted that these pathological measures of disease severity are not included in the current guidelines for recommending radiological staging.

The group with distant metastasis also had a larger total invasive tumour size, but only two patients had a tumour size over 50mm, which is the size used for recommending radiological staging in some guidelines. It should also be noted that the invasive tumour size is a postoperatively, pathological measurement. The clinical total tumour size (which is what is referred to in most guidelines) was not significantly different between the group with distant metastasis and those without. This suggests that although a larger tumour size may be associated with distant metastasis, using the dimension of 50mm as an isolated marker to recommend radiological staging may not be adequately sensitive.

The binomial logistic regression model of those patients who had postoperative radiological staging to predict distant metastasis based on patient and tumour characteristics had poor sensitivity, only correctly predicting one true positive (one patient with distant metastasis). A prediction model that resulted in so many false negatives is not useful in the clinical setting. A possible reason why it did not reach statistical significance is because the number of patients with distant metastasis was small (n = 8), so the model may be statistically underpowered. This is an issue with many studies investigating distant metastasis in early breast cancer. However, the lack of differences between the groups with distant metastasis versus without distant metastasis and the performance of the prediction model demonstrates the difficulty in predicting patients who have distant metastasis, and that, based on our data set, these clinical details cannot accurately predict distant metastasis. It further strengthens the argument that all patients with a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy should have radiological staging as other characteristics cannot risk stratifying patients accurately.

The review of current guidelines and applying them to our population suggests current guideline thresholds for recommending radiological staging are too high. A number of guidelines suggest radiological staging in patients with symptoms indicative of distant metastasis;8–10,21,22 however in our study no patients with distant metastasis had symptoms at the time of detection, suggesting that using this criteria alone would miss patients with distant metastasis. Guidelines also recommend staging very judiciously in asymptomatic patients, generally in stage III or IV.

Staging very low risk breast cancers may cause unnecessary radiation exposure, detection of incidental findings only, unnecessary scans or investigations and a low detection rate of distant metastasis.11 However, in our population, only 4.5% of staged patients had further scans or investigations for incidental findings not requiring treatment and only one patient had an additional invasive biopsy performed for an incidental finding as a result of radiological staging. The low false positive rate in this study is much less than in a previous similar study that was performed outside the UK, perhaps reflecting differences in practice between countries,23 and suggests that the risk and potential harm of false positives are less than in the reported literature. It may be that the disadvantage of an increased rate of incidental findings with a lower threshold for recommending radiological staging is overestimated in current guidelines.

A commonly given reason for performing radiological staging in higher staged disease only could be because detecting bone and central nervous system metastasis early does not prolong survival.8

It may be that early detection of metastases to these sites does not prolong life; however, guidelines for the management of bone and brain metastases include bisphosphonates for symptom control, external beam radiotherapy, and possibly operative fixation (in long bones) and resection (for single brain metastases).3 This suggests that even in these indolent metastasis early detection allows active management of complications and improves patient care. In our study population with distant metastasis, only two patients had bone metastases alone, and the other six patients had visceral metastases which are associated with a poor prognosis,24 where patients benefit from an accurate diagnosis and supportive care services.25

Only two guidelines give explicit guidance on radiological staging with postoperative pathological information, two suggesting staging those with a tumour size greater than 50mm and one suggesting staging those with four or more positive axillary lymph nodes. Auditing our population against these criteria, less than one-third of patients who had radiological staging would have been recommended staging by the guideline criteria. Over 50% of patients with distant metastasis would not have been recommended radiological staging against these guidelines, suggesting the threshold for radiological staging in these guidelines are too high.

In this study population, all cases of distant metastasis detection resulted in a change to the patient management; there was a significant change in either operative management and/or change in chemotherapy regimen to optimise treatment for the disease stage. This demonstrates that early detection of distant metastasis is necessary for optimising patient care, and current guidelines may fail to detect patients with distant metastasis.

There are some limitations to this study. Patient information was retrospectively collected which introduces some selection bias. Not all patients with a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy in this cohort underwent radiological staging, and not all patients had radiological staging investigations according to local guidelines, the rationale for why some patients did not have staging investigations and why there was deviation from local radiological guidelines could not be elucidated retrospectively and may have informed our study.

The differences in patient and tumour characteristics between those staged and those not staged were assessed to identify trends in the multidisciplinary team decision to recommend radiological staging. This comparison showed that staged patients were younger and had an increased association with lymphovascular invasion. Although these may be markers of more aggressive tumour types, prompting the recommendation of radiological staging, it would be unlikely to prompt the recommendation of radiological staging in isolation. Some 92% of those who had radiological staging had macrometastasis, and only 26% of those not staged had macrometastasis (with the remainder being micrometastasis).

Axillary micrometastasis are treated differently to macrometastasis with regards to further axillary surgery and chemotherapy and are associated with a better prognosis than macrometastasis,10 which may explain why fewer had radiological staging. The reason why some patients with macrometastasis were not staged may be due to other tumour characteristics or patient choice. It is possible that risk of distant metastasis at presentation with axillary micrometastasis is low (no patients in this study with micrometastasis had distant metastasis). However, this conclusion cannot be firmly drawn, and previous studies suggest micrometastasis are associated with distant metastasis development.26,27 Further prospective studies are required to further elucidate the difference in risk of distant metastasis at presentation between those with micro- and macrometastasis after sentinel lymph node biopsy.

The assessment of whether there was a change in management due to a diagnosis of distant metastasis may be subject to interpretation bias, as it was performed retrospectively. However, in all cases the reason for changing management plan was documented explicitly as being in reference to the staging findings. The recommendations for further surgery and chemotherapy regimens differ according to whether treatment is with palliative or curative intent,3 so the findings that management plans were changed on the discovery of distant metastasis is likely to be a true finding.

This study takes place within a single unit, which is common to similar studies. If other centres contributed data this would increase sample size and provide external validation. However, as there is substantial variation in radiological staging practice within the same country,14 this would be logistically difficult to perform retrospectively. The literature search of this study highlights the lack of consensus on which patients should be radiologically staged and so performing a multicentre prospective study would be challenging.

We present the largest data set of patients with a preoperative negative axilla with subsequent positive sentinel lymph node biopsy with regards to investigating suitability of radiological staging. There is only one previous study investigating this group of patients, which had a smaller number of patients who underwent radiological staging (50 patients), and they detected no distant metastasis in their study group, suggesting that it may have been underpowered.23 No previous studies have audited current guidelines to assess their suitability in routine clinical practice, and by doing this we found that current guidelines appear inadequate for distant metastasis detection in the positive sentinel lymph node biopsy population.

Conclusion

In our population of preoperatively node-negative patients with positive sentinel lymph node biopsy who had radiological staging, there was a distant metastasis detection rate of 3.5% and all cases of distant metastasis detection altered the management plan. Patient and tumour characteristics cannot be reliably used to risk stratify or predict which patients should have radiological staging and current guideline criteria are inadequate. We propose that all patients with positive sentinel lymph node biopsy should have radiological staging investigations for distant metastasis.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018; : 394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeSantis CE, Ma J, Goding Sauer A et al. Breast cancer statistics, 2017, racial disparity in mortality by state. CA Cancer J Clin 2017; : 439–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Advanced Breast Cancer: Diagnosis and Treatment. Clinical Guideline CG81. London: NICE; 2009. (updated 2017). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weigelt B, Peterse JL, Van’t Veer LJ. Breast cancer metastasis: markers and models. Nat Rev Cancer 2005; : 591–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LH Sobin MG, CH Wittekind. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours, 7th ed Chichester: John Wiley and Sons; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Senkus E, Kyriakides S, Ohno S et al. Primary breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2015; : v8–v30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kennecke H, Yerushalmi R, Woods R et al. Metastatic behavior of breast cancer subtypes. J Clin Oncol 2010; : 3271–3277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barter S BP. Breast Cancer. London: The Royal College of Radiologists; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Society of Clinical Oncology Don’t perform PET, CT, and radionuclide bone scans in the staging of early breast cancer at low risk for metastasis. Choosing Wisely 4 April 2019. https://www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/american-society-clinical-oncology-pet-ct-radionuclide-bone-scans-in-staging-early-breast-cancer (cited March 2020).

- 10.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Early and Locally Advanced Breast Cancer: Diagnosis and Management. NICE Guideline NG101. London: NICE; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barrett T, Bowden D, Greenberg D et al. Radiological staging in breast cancer: which asymptomatic patients to image and how. Br J Cancer 2009; : 1522–1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Del Turco MR, Palli D, Cariddi A et al. Intensive diagnostic follow-up after treatment of primary breast cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA 1994; : 1593–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Myers RE, Johnston M, Pritchard K et al. Baseline staging tests in primary breast cancer: a practice guideline. CMAJ 2001; : 1439–1444. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chand N, Cutress R, Oeppen R et al. Staging investigations in breast cancer: collective opinion of UK breast surgeons. Int J Breast Cancer 2013; : 506172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veronesi U, Paganelli G, Viale G et al. A randomized comparison of sentinel-node biopsy with routine axillary dissection in breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2003; : 546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB et al. Technical outcomes of sentinel-lymph-node resection and conventional axillary-lymph-node dissection in patients with clinically node-negative breast cancer: results from the NSABP B-32 randomised phase III trial. Lancet Oncol 2007; : 881–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.POSNOC POsitive Sentinel NOde: adjuvant therapy alone versus adjuvant therapy plus Clearance or axillary radiotherapy. http://www.posnoc.co.uk/healthcare-professionals/protocol.aspx (cited March 2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Purushotham A, Shamil E, Cariati M et al. Age at diagnosis and distant metastasis in breast cancer–a surprising inverse relationship. Eur J Cancer 2014; : 1697–1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carter CL, Allen C, Henson DE. Relation of tumor size, lymph node status, and survival in 24,740 breast cancer cases. Cancer 1989; : 181–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosen PP, Groshen S, Saigo PE et al. Pathological prognostic factors in stage I (T1N0M0) and stage II (T1N1M0) breast carcinoma: a study of 644 patients with median follow-up of 18 years. J Clin Oncol 1989; : 1239–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breast Cancer Clinical Expert Group Clinical Advice to Cancer Alliances for the Provision of Breast Cancer Services. 2017. https://breastcancernow.org/get-involved/campaign-us/what-we-think/clinical-advice-cancer-alliances-provision-breast-cancer (cited March 2020).

- 22.Aebi S, Davidson T, Gruber G et al. Primary breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2011; : vi12–vi24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pellet AC, Erten MZ, James TA. Value analysis of postoperative staging imaging for asymptomatic, early-stage breast cancer: implications of clinical variation on utility and cost. Am J Surg 2016; : 1084–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solomayer E-F, Diel I, Meyberg G et al. Metastatic breast cancer: clinical course, prognosis and therapy related to the first site of metastasis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2000; : 271–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Improving Supportive and Palliative Care for Adults with Cancer. Cancer Service Guideline CSG 4. London: NICE; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salhab M, Patani N, Mokbel K. Sentinel lymph node micrometastasis in human breast cancer: an update. Surg Oncol 2011; : e195–e206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reed J, Rosman M, Verbanac KM et al. Prognostic implications of isolated tumor cells and micrometastases in sentinel nodes of patients with invasive breast cancer: 10-year analysis of patients enrolled in the prospective East Carolina University/Anne Arundel Medical Center Sentinel Node Multicenter Study. J Am Coll Surg 2009; : 333–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]