Abstract

Cotton fibre provides a unicellular model system for studying cell expansion and secondary cell wall deposition. Mature cotton fibres are mainly composed of cellulose while the walls of developing fibre cells contain a variety of polysaccharides and proteoglycans required for cell expansion. This includes hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins (HRGPs) comprising the subgroup, extensins. In this study, extensin occurrence in cotton fibres was assessed using carbohydrate immunomicroarrays, mass spectrometry and monosaccharide profiling. Extensin amounts in three species appeared to correlate with fibre quality. Fibre cell expression profiling of the four cotton cultivars, combined with extensin arabinoside chain length measurements during fibre development, demonstrated that arabinoside side-chain length is modulated during development. Implications and mechanisms of extensin side-chain length dynamics during development are discussed.

Abbreviations: AGPs, arabinogalactan proteins; CoMPP, comprehensive microarray polymer profiling; CrRLK1L, Catharanthus roseus receptor-like1-like kinase; DPA, days post anthesis; EXTs, extensins; GH, glycoside hydrolase; HRGPs, hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins; Hyp-Aran, extensin side-chain of length n; LRX, leucine-rich repeat extensins; PCW, primary cell wall; SCW, secondary cell wall; SGT, serine galactosyltransferase; HPAT, hydroxyproline arabinosyltransferase; RRA, arabinosyltransferase named after the mutant Reduced Residual Arabinose; XEG113, arabinosyltransferase named after the mutant Xyloglucan Endo-Glucanase resistant mutant 113; ExAD, arabinosyltransferase named after the mutant Extensin Arabinose Deficient

Keywords: Cotton fibre, HRGP, Extensin arabinoside metabolism, Cotton fibre quality, Transcriptomics, CoMPP

1. Introduction

Plant cell walls are constructed primarily of polysaccharides but glycoproteins can account for up to about 10% of the dry weight (Albersheim et al., 2011) and have diverse functions in development and stress responses (Nguema-Ona et al., 2014). The hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins (HRGPs) superfamily consists of highly glycosylated arabinogalactan proteins (AGPs), moderately glycosylated extensins (EXTs) and lightly glycosylated proline-rich proteins (PRPs) (Kieliszewski et al., 2010, Showalter et al., 2010). Extensins feature a characteristic repetitive Ser-Hyp4 motif in which hydroxyproline (Hyp) and Ser residues are O-glycosylated with one to four (and occasionally five) arabinosyl residues and a single galactose residue, respectively (Lamport, 1963). Gene and protein names in the literature mostly relate to Arabidopsis but this type of O-linked protein glycosylation is as old as the green plant lineage (Domozych et al., 2012).

The precise structures vary significantly across the plant kingdom with notable differences between grasses and other flowering plants (Carpita, 1996). Extensins make up a relatively minor proportion of the cell wall while not challenged by biotic or abiotic stress and under these conditions they are assumed to serve as a scaffold for proper wall assembly (Cannon et al., 2008, Hijazi et al., 2014). Insight into extensin functionality has increased significantly since extensins were first described in 1960s (Lamport et al., 2011). At cell wall pH, positively charged extensins pair with negatively charged pectin, which together with their ability to align and form peroxidase mediated covalent crosslinks, define and confer their structural functionality within the cell wall (Brady et al., 1996, Lamport et al., 2011, Nuñez et al., 2009, Valentin et al., 2010). The Arabidopsis root-shoot-hypocotyl defective, rsh, mutant of the cell wall hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein RSH is lethal suggesting that extensins are essential for embryogenesis (Hall and Cannon, 2002). Co-expression analysis has demonstrated that a group of peroxidases under control of the RSL4 transcription factor, cluster with a group of extensins (Marzol et al., 2018). Furthermore, Arabidopsis phenotypes generated by biochemical inhibition or genetic disruption of extensin proline hydroxylation and Hyp-glycosylation confer aberrant hypocotyl and root morphogenesis, indicating the importance of extensins in cell differentiation and expansion (Gille et al., 2009, Ogawa-Ohnishi et al., 2013, Velasquez et al., 2011) and previous studies found correlation between expression of extensin-like proteins and tip growth in tomato (Bucher et al., 2002).

Leucine-rich repeat extensins (LRXs) are also involved in maintaining cell wall integrity during pollen tube growth in Arabidopsis, as knock out mutants showed irregular deposition of callose and pectin. A complex of LRX, several CrRLK1Ls and the Rapid Alkaline Factors 4 and 19 was shown to act as an autocrine mechanism monitoring cell wall integrity during pollen growth in Arabidopsis (Ge et al., 2017, Mecchia et al., 2017). The importance of extensin O-glycosylation for protein conformation is well established (Stafstrom and Staehelin, 1986), and the significance the fourth Araf residue for cross-linking has been substantiated by in vitro studies (Chen et al., 2015, Møller et al., 2017). Chen et al. (2015) showed that initial rate of cross-linking was primarily determined by the presence of Hyp-Ara4, and the number of cross-linking motifs in the protein backbone. Molecular dynamics simulations have indicated that O-glycosylation stabilizes the helical conformation, whereas incomplete glycosylation leads to a flexible conformation, and high levels of O-glycosylation was also shown to restrict the lateral alignments of EXTs (Velasquez et al., 2015). Extensins were early on shown to be deposited as cell wall repair following pathogen attack and also to attribute to wound and stress responses (Esquerré-Tugayé et al., 1979, Merkouropoulos and Shirsat, 2003).

Cotton fibre is the most important natural textile fibre and the high industrial value drives the research to understand the correlation between cotton fibre quality and composition (Chen et al., 2007). Cotton fibre is a unique unicellular model for the study of cell elongation and cellulose deposition, which eliminates the complication of cell division and multicellular differentiation (Haigler et al., 2012, Kim and Triplett, 2001). Cellulose makes up more than 94% of the cotton seed trichome dry weight in mature cotton fibres (Yang et al., 2008). However, in developing cotton fibre, cellulose constitutes only 35–50% of the primary cell wall (PCW) on a dry weight basis (Tokumoto et al., 2002). Various ‘omics studies have provided insight into the molecular and biochemical events regulating cotton fibre development (Gou et al., 2007, Lee et al., 2007, Shi et al., 2006, Tuttle et al., 2015, Wang et al., 2016, Xu et al., 2007). The majority of transcripts expressed at early stage of cotton fibre development are maintained at similar expression levels until the onset of secondary cell wall (SCW) deposition. SCW cellulose starts to be deposited within a transiently-synthesized winding layer (analogous to the S1 layer in wood xylem) and SCW begins to thicken rapidly when the transition stage from PCW elongation to SCW deposition ends (Kerr, 1946, Waterkeyn, 1981). PCW is remodelled through the action of transcriptionally upregulated sets of glycoside hydrolases (GHs) and carbohydrate esterases resulting in decrease of pectin and xyloglucan during SCW deposition (Haigler et al., 2009, Meinert and Delmer, 1977, Shao et al., 2011, Shimizu et al., 1997, Tokumoto et al., 2002, Tuttle et al., 2015).

Correlations between amounts of xyloglucan, homogalacturonan, and callose in mature cotton fibre and cotton fibre characteristics have been investigated (Haigler et al., 2009, Rajasundaram et al., 2014, Singh et al., 2009). In a study by Hernandez-Gomez et al. (2015), the dynamics of xylan and mannan during cotton fibre development were shown to be determinants of fibre quality, and a comparison of low and high fibre quality Gossypium species, revealed a correlation between expression of a pectin methylesterase gene and fibre quality (Al-Ghazi et al., 2009). Involvement of HRGPs in fibre synthesis has been shown by RNAi silencing of the fasciclin-like arabinogalactan protein GhAGP4 which led to inhibition of fibre initiation and elongation in G. hirsutum (Li et al., 2010).

The extensin repertoire has been classified in several species (Johnson et al., 2017, Liu et al., 2016) but not in cotton. With the recent identification of ExAD (Møller et al., 2017), the arabinosyltransferase that adds the fourth residue to extensin arabinoside side-chains, all GTs involved in extensin glycosylation have been identified with the exception of the enzyme responsible for transfer of the rare fifth residue. All identifications were carried out in Arabidopsis. Predicted corresponding cotton genes are annotated on the basis of high similarity to the Arabidopsis orthologues. Transcripts of genes encoding extensin proteins have been identified in transcriptomics studies to be highly enriched both at 10 and 20 days post anthesis (DPA), further suggesting involvement in the fibre development (Islam et al., 2016, Miao et al., 2017). Also, in one of the three regression models a correlation between extensin content and fibre length and strength was indicated (Rajasundaram et al., 2014). It thus appears that cotton fibre quality is influenced by processing of the cell wall matrix in general.

In this study we examined extensins during cotton seed trichome development from three cotton species which contribute to most of the world cotton production, allopolyploid G. barbadense and G. hirsutum, and diploid G. arboreum (Wendel et al., 2009). To study extensin dynamics in cotton fibre development, 11 time points were analysed using carbohydrate immunomicroarrays to perform comprehensive microarray polymer profiling (CoMPP) (Moller et al., 2007) and expression profiling of genes involved in glycosylation in developing cotton fibre, combined with characterization of Hyp-arabinoside chain lengths. Whereas extensin side chain length ratios are commonly thought of as species specific characteristics (Lamport and Miller, 1971), we here report that these ratios appear to be subject to developmental control as well. Furthermore, the content of extensins during development is speculated to be indicative to the mature fibre characteristics on the basis of correlations reported here between loosely bound extensin content at transition stage and mature cotton fibre mechanical properties.

2. Results

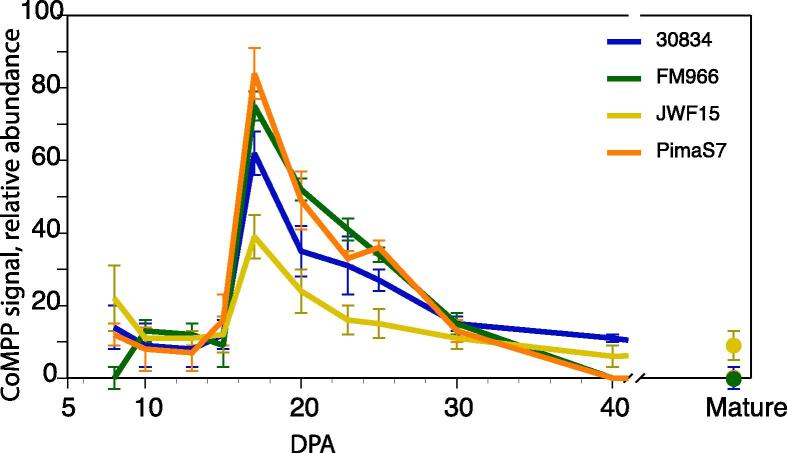

2.1. JIM20 epitope dynamics during cotton fibre development identified by CoMPP

The content of CDTA and NaOH extractable extensins in developing cotton seed trichomes was investigated in four cultivars representing three Gossypium species. Extensin content in initial CDTA extractions, sampled from 8 DPA to mature fibre, was assessed through probing with mAb JIM20, which is predicted to bind to an epitope containing arabinoside chains typical of extensins (Smallwood et al., 1994). Ongoing investigation using extensin glycosylation mutants have shown that JIM20 has a strict requirement for the β-arabinosides for binding while binding is unaffected by the presence or absence of the fourth, α-linked Araf residue (Cora MacAlister, Michigan Univ., personal communication) making JIM20 particularly suitable for the present purpose.

Based on the profile of extractable callose, we recently estimated the transition from primary to secondary cell wall deposition occurs approximately at 17 DPA (Guo et al., 2019). CDTA-extractable extensins displayed a peak coinciding with onset of secondary wall deposition. We hypothesize that CDTA extractable JIM20 signal represents recently synthesized and thus not yet cross-linked extensin molecules as well as extensins lacking cross-linking motifs. Cross-linked extensins are highly resistant to extraction without cleavage of the covalent bonds and the inconsistent measurements of NaOH extractable extensins (supplementary Fig. 1) are interpreted to be the results of covalent cross-links impairing extraction (Fry, 2000) and proper quantitation.

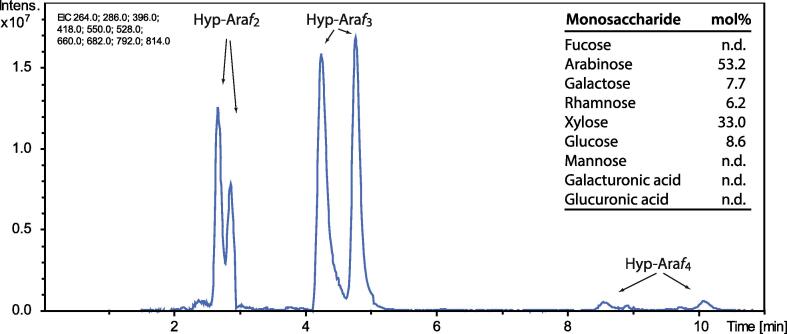

3. Hyp-Araf1-4 verification by mass spectrometry and monosaccharide profiling

To ascertain correct interpretation of the CDTA extraction data presented in Fig. 1 we selected one of the cultivars, FM966 (G. hirsutum), and prepared Ba(OH)2 hydrolysates of the fibres. The appropriate size range of a 20 DPA hydrolysate was isolated using gel permeation chromatography. The presence of extensin arabinosides was evident by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis where the doublet peaks in the selected ion traces, resulting from hydroxyproline (Hyp) isomerization during Ba(OH)2 hydrolysis, are diagnostic of Hyp-Arafn species (Møller et al., 2017, Fig. 2). The presence of extensins in cotton fibres from 20 DPA was thus confirmed and corroborates the detection of extensin by CoMPP. The monosaccharide profile suggests that xylan, rhamnogalacturonan-I and possibly callose are extracted and partially degraded by saturated Ba(OH)2 at 108 °C. The xylose content could be from 4-O-Methyl-d-glucurono-d-xylan derived oligos, as 4-O-Methyl-d-Glucuronic acid was not analysed for and the xylans in cotton has a high degree of methylation of the Glucuronic acid on xylans (Kim and Ralph, 2014). We found that purification by gel permeation chromatography was not required to obtain clear spectra by mass spectrometry so the analyses presented below were obtained on the Ba(OH)2 hydrolysates directly.

Fig. 1.

CDTA extracted extensins as measured with mAb JIM20 in developing cotton fibre. All four cotton cultivars exhibited similar content dynamics during development. PimaS7 and JWF15 represent diploid cotton and PimaS7 and FM966 represent allopolyploid cotton. Very low amount of extensin was detected in mature fibre. Error bars represent standard deviation of three biological replicates.

Fig. 2.

Liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry of a Ba(OH)2 hydrolysate of FM966 fibres sampled 20 DPA. Diagnostic ion traces of Hyp-Araf2-4 (extracted ion traces of [M + H+|Na+]+ 396/418 (Hyp-Araf2), 528/550 (Hyp-Araf3) and 660/682 (Hyp-Araf4 each eluting as twin peaks due to the C-4 R/S stereochemistry of hydroxyproline (Hyp)), were monitored by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry of a Ba(OH)2 hydrolysate of FM966 fibres sampled 20 DPA. Three technical replicates were analysed. The table insert shows a monosaccharide profile of a fraction enriched in Hyp-arabinosides and arabinose isolated by size exclusion chromatography using a BioRad P2 column.

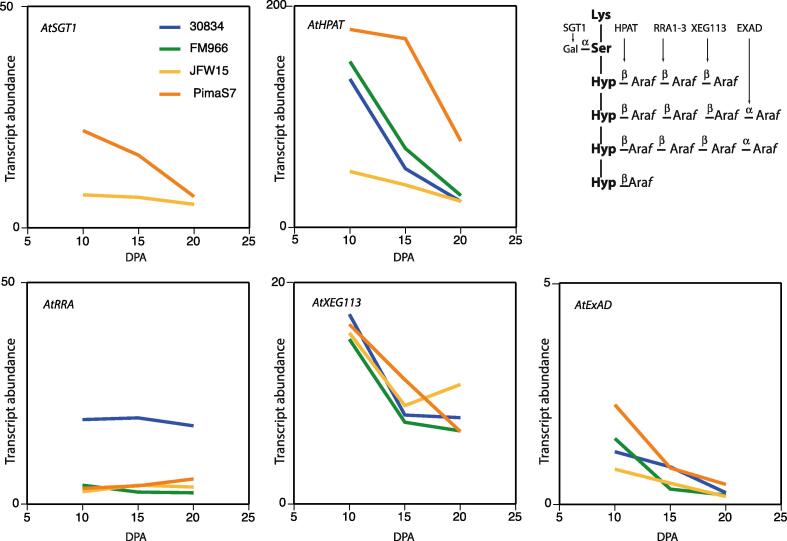

4. Expression profiling of GTs involved in extensin glycosylation

The transcriptome dataset previously analyzed for mannan and xylan synthesis-related genes (Hernandez-Gomez et al., 2015) were analyzed for expression of glycosytransferase (GT) genes involved in extensin O-glycosylation. Four cotton lines were analysed, two diploids and two allopolyploids, in order to cover variation in fibre length and strength. Table 1 shows G. raimondii sequences mapped to the CAZy database (Lombard et al., 2013) and annotated as described by Harholt et al. (2012). Transcripts were in turn mapped to the G. raimondii sequences to identify orthologs, see Table 1 in Materials and Methods.

Table 1.

Arabidopsis thaliana: Gossypium raimondii orthologies of genes encoding glycosyltransferases that galactosylate extensin or build extensin arabino-sides. Activities are given in the inset in Fig. 3.

|

Arabidopsis gene name |

Arabidopsis locus |

G. raimondii locus |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SGT | At3g01720 | Gorai.006G037200 |

| 2 | HPAT1-3 | At5g25265 At2g25260 At5g13500 |

Gorai.001G035500 Gorai.006G124300 Gorai.010G216000 Gorai.011G215700 |

| 3 | RRA1-3 | At1g75120 At1g75110 At1g19360 |

Gorai.010G011500 Gorai.012G146400 |

| 4 | XEG113 | At2g35610 | Gorai.004G177500 Gorai.008G219000 |

| 5 | ExAD | At3g57630 | Gorai.006G138400 |

Fig. 3 shows expression profiles of GTs involved in extensin O-glycosylation. None of the GTs displayed a peak at the transition to SCW deposition. This was expected given the observations that expression profiles of genes involved in extensin O-glycosylation constitute a biosynthetic module (Møller et al., 2017), which, however, does not comprise their substrates, i.e. the genes encoding the extensin proteins. Also, the signal in Fig. 1 represents the easily extractable sub-fraction of extensins.

Fig. 3.

Relative expression levels of GTs tentatively involved in extensin O-glycosylation. Relative abundances of transcripts mapping to G. raimondii genes that are predicted orthologs of the Arabidopsis genes are indicated in each panel. Relative transcript abundances are given on the Y-axis using an arbitrary scale (see Materials and Methods).

It is noteworthy that cotton orthologs of AtXEG113 and AtExAD are expressed at particularly low levels. The GTs encoded by these genes add the third and the fourth arabinose onto extensin arabinosides, respectively, (inset in Fig. 3) and hence comparatively short extensin side-chains may be expected in the cotton fibres. Moreover, the expression of ExAD dropped to zero before extensin arabinosylation as a whole terminated. This finding prompted us to investigate the modulation of arabinoside chain-length during fibre development. SGT1 expression was only above the detection threshold for two of the cotton cultivars.

5. Extensin arabinoside chain length changes during cotton fibre development

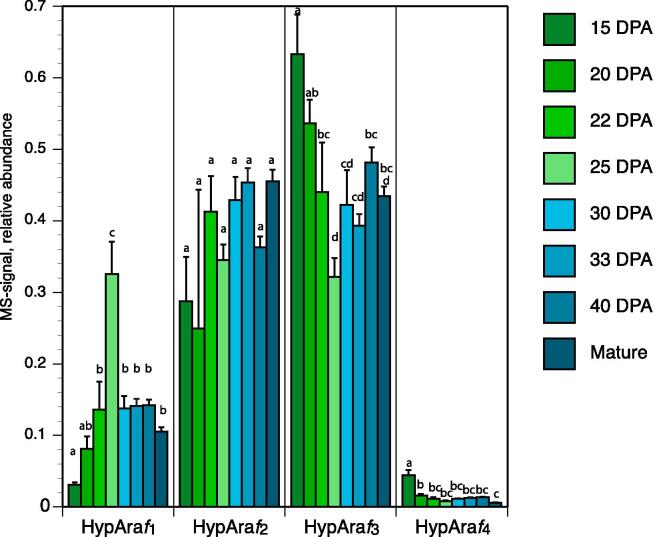

The Hyp-Araf side-chain of total (not only the recently deposited) extensins in cotton fibre of FM966 are relatively short and are further shortened as the fibres mature (Fig. 4). This may be a direct consequence of the expression profiles of the extensin glycosyltransferases (Fig. 3). But there are at least two other possibilities to consider: Firstly, as the fibre elongates and grows substantially, extensins previously deposited are diluted and more recently secreted extensins may not be products of the same genes. Secondly, extensin side-chains may be subject to metabolism. Plants are not known to be able to cleave β-1,2-linkages between arabinofuranose residues, but α-linked arabinoses may be released by arabinofuranosidases of family GH51 or dual function hydrolases of family GH3 (Bouraoui et al., 2016, Macdonald et al., 2015).

Fig. 4.

Relative abundance of extensin side-chains (Hyp-Araf1-4) in fibres of FM966 as determined by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry at different cotton fibre developmental stages as indicated by DPA and mature. Error bars represent standard deviation. Shared group letters within each side-chain length indicate no significant difference at p < 0.05. Araf1 + Araf2 + Araf3 + Araf4 = 1.0.

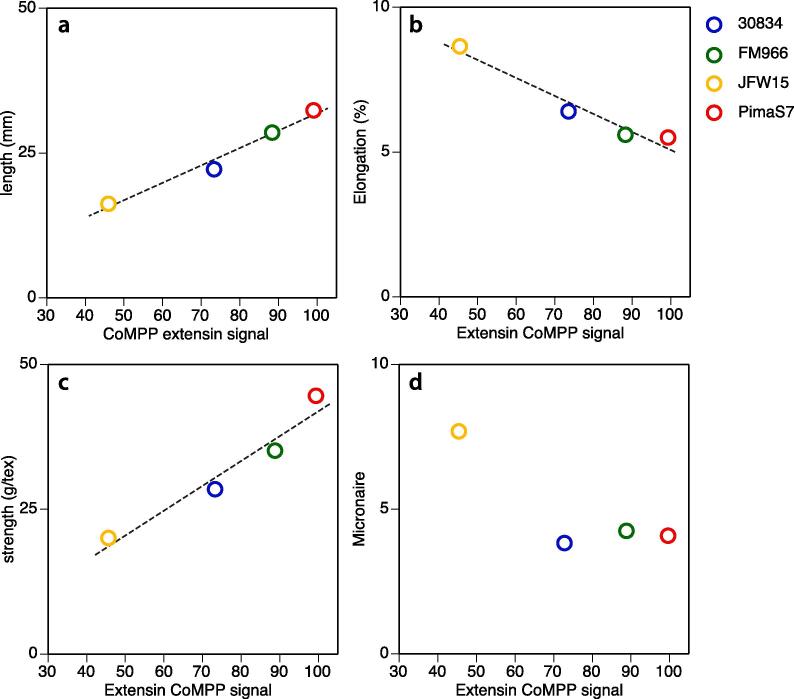

6. Developing cotton fibre extensin content correlated to mature cotton fibre properties

Extensin time course profiles, as extracted by CDTA, during development were generally comparable across the four cultivars but the peak value at 17 DPA differed across the cotton cultivars (Fig. 1). By plotting the CoMPP value at 17 DPA with various mature cotton fibre characteristics previously published (Rajasundaram et al., 2014), see Fig. 5, we observed that fibre strength (measured as load (g) required to break 1000 m weight equivalent of fibre (tex)) and length were positively correlated with extractable extensin peak content, while elongation was negatively correlated; no correlation between micronaire and extensin content was found. Micronaire is a measure of fibre fineness (larger numbers mean coarser fibres) and all but one line, JWF15, fall in the premium quality range.

Fig. 5.

Mechanical properties of cotton fibre as functions of the extensin CoMPP signal. A. Mechanical properties were determined with the High Volume Instrument (HVI) by CIRAD (France) from 5 g of mature cotton of each line. A sampled fibre is held at a random point and two ends are aligned to measure the length. B. Strength is measured physically by clamping a fibre bundle at known distance and then pulled away at a constant speed until the fibre bundle breaks; the distance it travelled before breakage, shown in percentage to the set distance, was defined as elongation (C). D. The fineness of cotton fibre is evaluated by the Micronaire value. The underlying data and statistical treatment of the physical properties of which the means are used here were published by Rajasundaram et al. (2014).

7. Discussion

Monoclonal antibody JIM20 was used to profile an extensin epitope during cotton fibre development. Extensins are generally insolubilised with time by oxidative cross-linking of Tyr residues in particular cross-linking motifs, cross-links that require chlorite to be cleaved (Fry, 2000). Cross-linking is not restricted to inter- and intra-chain extensin cross-linking as evidence has been presented that cross-links to pectin for example exists in cotton (Qi et al., 1995). Extensin abundance as detected with mAb JIM 20 displays a remarkable profile in which non-cross-linked, CDTA-extractable extensins increase transiently at the time of transition to SCW deposition. This is consistent with what has been observed for callose and furthermore suggests that distinct extensins are deposited at different developmental stages.

In this study, extensin arabinosides in cotton seed trichome were found to be significantly shorter than in Arabidopsis which has an Hyp-Araf3:Hyp-Araf4 ratio of 4/1 in alcohol insoluble residues of 6 weeks old mature bolting plants (Møller et al., 2017). In cotton suspension cultures the ratio is ~0.6/1 (Qi et al., 1995) while in fibres at 20 DPA this ratio is >10/1 and the ratio increases with time (see Fig. 4). Ba(OH)2 extraction is not impaired by cross-linking or limited extractability so the reported ratios represent total extensins. Very early on in development, where material availability was too scarce for analysis the ratio may, however, be closer to that of Arabidopsis or the ratio observed in cotton suspension cultures. It is significant that chain length distribution appears to be stable in Arabidopsis across tissues and developmental stages (Møller et al., 2017) while it appears to be much more dynamic in cotton fibre. There are at least three not mutually exclusive possible contributions to this: 1) Extensin side-chain length is a direct reflection of the expression levels of the relevant GTs and how their expression changes during development. 2) Extensins, i.e. extensin gene products, deposited at different developmental stages may differ. Sample preparation for Hyp-Araf analysis is not selective for classical extensins (secreted extensins featuring the motif shown in the Fig. 3 inset and often also cross-linking motifs). And 3) the side-chains might be degraded by appropriate hydrolases. Expressed arabinofuranosidase candidates of GH3 and GH51 have been reported and biochemical evidence for arabinofuranosidase activity in crude fibre extracts provided (Guo et al., 2019). The activities were implied in pectic arabinan metabolism, which accompany cotton fibre middle lamella degradation. Removal of the fourth α-linked Araf-residue could either be the result of side-activities of the hydrolases responsible for pectic arabinan degradation in which case the shortening of extensin arabinosides may be without biological significance. Alternatively, extensin-specific α-arabinofuranosidase activity may be at play. Further shortening of the arabinosides by hydrolysis will require β-arabinofuranosidase activity and developmentally regulated modulation of arabinoside length during fibre development therefore hinges on the existence in plants of β-arabinofuranosidases. The only known enzymes with this activity belong to families GH121 and GH127 (Fujita et al., 2014, Fujita et al., 2011) none of which, however, comprise plant genes.

Expression profiles of genes encoding arabinosyltransferases are compatible with either hypothesis. The pronounced disappearance of the fourth arabinosyl residue between day 15 and 20, i.e. during rapid deposition of CDTA-extractable extensin may either point to a particular extensin being deposited, or towards the presence of extensin specific α-arabinofuranosidase activity. Easily extractable extensins may either be classical extensins not yet cross-linked, bona fide extensins without cross-linking motifs, or may be extensin domains in other HRGPs. Detection with JIM20 does not discriminate between these possibilities. Which HRGPs are expressed during fibre development becomes a pertinent question since the JIM20 signal appears to correlate with mechanical fibre properties. This, however, does not imply that extensins are load-bearing structures in the wall, but rather that extensins may function as templates during wall assembly and thus influence cell wall architecture.

8. Material and methods

8.1. Plant materials

Four cotton cultivars from three different Gossypium species provided by Bayer CropScience were analysed in this study: G. hirsutum (cv FM966), G. barbadense (cv PimaS7), G. arboreum (cv 30834 and cv JFW15). Cv. 30834 and JWF15 are diploid cotton and PimaS7 and FM966 are allopolyploid cotton cultivars. The transcriptomic dataset analysed for transcripts of genes encoding extensin glycosyltransferases are identical to the one analysed previously for transcripts of relevance to the cotton fibre middle lamella metabolism and so is the material analysed by CoMPP (Guo et al., 2019).

8.2. Comprehensive microarray polymer profiling

CoMPP analysis was carried out as previously described (Moller et al., 2007). Cotton fibres from at least three different plants at each time point for each cultivar were collected for CoMPP analysis. For each three technical replicates of 10 mg of grounded fine cotton fibre powder was extracted in two 300 μL solvents sequentially, 50 mM CDTA and 4 M NaOH with 1% (v/v) NaBH4 for pectic polysaccharides epitope extraction and hemicellulose and more tightly bonded polymers extraction, respectively. Three independent prints and three independent probings of each print, giving total nine replicates, were applied in the data analysis. CoMPP result was presented by individual scaling in which maximum signal observed in probing was assigned as 100 and the other signals scale to the highest value. Line chart was generated by plotting individual scaled carbohydrate immunomicroarray data. The CoMPP technique is a semi-quantitative method, which only provides information of relative amount of solvent extractable epitopes.

8.3. Transcriptomic analysis

Transcriptomic profiles were derived from the same dataset that formed the basis for the analysis of cellulose, mannan, and xylan biosynthesis by Hernandez-Gomez et al. (2015). Cotton fibres from five cotton bolls at each time point were collected and the RNA preparations pooled for transcriptomic analysis. Annotation of transcripts in this dataset was carried out by mapping contigs to the Gossypium raimondii proteome. Levels of expressions were normalized to the total number of transcripts in the dataset for each cultivar. Transcript abundance of interest to the present study varied over ~2 orders of magnitude and is displayed on the same arbitrary Y-axis. A number at the top of each Y-axis indicates how they are scaled relative to one another. Expression of a xyloglucan fucosyltransferase was displayed with a Y-axis of 1 in (Guo et al., 2019) and these authors regarded this the lowest expression level that could reliably be measured; and this scaling is used also here. Some transcripts that might have been of interest, like SGT1, fell below this threshold.

Orthology was established on the basis of sequence similarities between the G. raimondii protein sequences and annotated proteins from Arabidopsis thaliana. A conservative approach has been adopted, i.e. sequences where annotations may be questioned have been left out. Sums of transcripts abundancies of orthologs are given

8.4. Analysis of Hyp-Arabinosides

Solid Ba(OH)2 was added to fibre samples, three replicates, suspended in water to 0.22 M and the vials were closed under N2 and incubated overnight at 108 °C. Following neutralization with H2SO4 and centrifugation, the hydrolysate was analyzed directly by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry for determination of chain-length; or applied to a BioRad Bio-Gel P2 column (1.6 × 60 cm, 1 mL/min) equilibrated with 50 mM ammonium formate pH 5.0. Pooled fractions were lyophilized twice, checked by mass spectrometry and analyzed for monosaccharide profile, see below.

Analysis was carried out using an Agilent 1100 Series LC (www.agilent.com) coupled to a Bruker HCT-Ultra ion trap mass spectrometer (www.bruker.com). A Luna C8(2) column (www.phenomenex.com; 3 M, 100 A, 150 × 2.0 mm) preceded by a Gemini C18 SecurityGuard (Phenomenex; 4 × 2 mm) was used at a flow rate of 0.2 mL min−1. The oven temperature was maintained at 35 °C. The mobile phases were: A, water with 0.1% formic acid; B, acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid. The gradient program was: 0–2 min, isocratic 1% B; 2–8.5 min, linear gradient 1–3% B; 8.6–9.6 min, isocratic 99% B; 9.7–17 min, isocratic 1% B. The mass spectrometer was run in positive ESI mode and the recorded mass range was m/z 100–1000. Chain-length distributions across developmental stages were analysed using the aov function in R and post-hoc tests were carried out using the HSD function in the R-package agricolae.

8.5. Monosaccharide composition analysis

Monosaccharide composition analysis was carried out as previously described in (Øbro et al., 2004). In brief triplicate samples were hydrolysed at 120 °C in 2 M trifluoroacetic acid, followed by evaporation under vacuum, re-suspended in water and monosaccharides analysed by high-performance anionic chromatography with amperometric detection.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

Jean-Luc Runavot, Stéphane Bourot and Frank Meulewaeter of Bayer CropScience are acknowledged for valuable advice and for making the mechanical test results and the transcriptomic data set available for this study.

Funding

This work was supported by Villum Foundation project PLANET (grant no. 00009283), the European Union Seventh Framework Programme under the WallTraC project (grant agreement No. 263916), the Danish Councils for Strategic and Independent Research (12-125709), and the Copenhagen University Excellence Program for Interdisciplinary Research (CDO2016). This paper reflects the authors’ views only. The European Community is not liable for any use that may be made of the information contained herein. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author contribution

XG prepared samples for transcriptomic analysis, and carried out CoMPP analysis supervised by JM and WGTW. PU and BØH determined orthology of the transcripts and performed transcript analysis; SRM and BLP did the mass spectrometric analysis, and JH provided the monosaccharide profile; PU, BØH and BLP wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcsw.2019.100033.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Albersheim P., Darvill A., Roberts K., Sederoff R., Staehelin A. Garland Science; New York, NY: 2011. Plant Cell Walls: from Chemistry to Biology. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ghazi Y., Bourot S., Arioli T., Dennis E.S., Llewellyn D.J. Transcript profiling during fiber development identifies pathways in secondary metabolism and cell wall structure that may contribute to cotton fiber quality. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009;50:1364–1381. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouraoui H., Desrousseaux M.-L., Ioannou E., Alvira P., Manaï M., Rémond C., Dumon C., Fernandez-Fuentes N., O’Donohue M.J. The GH51 α-L-arabinofuranosidase from Paenibacillus sp. THS1 is multifunctional, hydrolyzing main-chain and side-chain glycosidic bonds in heteroxylans. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 2016;9:140. doi: 10.1186/s13068-016-0550-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady J.D., Sadler I.H. Di-isodityrosine, a novel tetrametric derivative of tyrosine in plant cell wall proteins: a new potential cross-link. Biochem. J. 1996;315:323–327. doi: 10.1042/bj3150323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucher M., Brunner S., Zimmermann P., Zardi G.I., Amrhein N., Willmitzer L., Riesmeier J.W. The expression of an extensin-like protein correlates with cellular tip growth in tomato. Plant Physiol. 2002;128:911–923. doi: 10.1104/pp.010998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon M.C., Terneus K., Hall Q., Tan L., Wang Y., Wegenhart B.L., Chen L., Lamport D.T.A., Chen Y., Kieliszewski M.J. Self-assembly of the plant cell wall requires an extensin scaffold. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008;105:2226–2231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711980105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpita N.C. Structure and biogenesis of the cell walls of grasses. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 1996;47:445–476. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Dong W., Tan L., Held M.A., Kieliszewski M.J. Arabinosylation plays a crucial role in extensin cross-linking in vitro. Biochem. Insights. 2015;8(S2):1–13. doi: 10.4137/BCI.S31353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.J., Scheffler B.E., Dennis E., Triplett B.A., Zhang T., Guo W., Chen X., Stelly D.M., Rabinowicz P.D., Town C.D. Toward sequencing cotton (Gossypium) genomes. Plant Physiol. 2007;145:1303–1310. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.107672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domozych D., Ciancia M., Fangel J.U., Mikkelsen M.D., Ulvskov P., Willats W.G.T. The cell walls of green algae: a journey through evolution and diversity. Front. Plant Sci. 2012;3:82. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esquerré-Tugayé M.-T., Lafitte C., Mazau D., Toppan A., Touzé A. Cell surfaces in plant-microorganism interactions: II. Evidence for the accumulation of hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins in the cell wall of diseased plants as a defense mechanism. Plant Physiol. 1979;64:320–326. doi: 10.1104/pp.64.2.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry, S.C., 2000. The growing plant cell wall: chemical and metabolic analysis, Org 1988. ed. Longman Group Limited.

- Fujita K., Sakamoto S., Ono Y., Wakao M., Suda Y., Kitahara K., Suganuma T. Molecular cloning and characterization of a β-L-arabinobiosidase in Bifidobacterium longum that belongs to a novel glycoside hydrolase family. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:5143–5150. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.190512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita K., Takashi Y., Obuchi E., Kitahara K., Suganuma T. Characterization of a Novel β-l-Arabinofuranosidase in Bifidobacterium longum functional elucidation of a DUF1680 protein family member. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:5240–5249. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.528711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Z., Bergonci T., Zhao Y., Zou Y., Du S., Liu M.-C., Luo X., Ruan H., García-Valencia L.E., Zhong S. Arabidopsis pollen tube integrity and sperm release are regulated by RALF-mediated signaling. Science (80-) 2017;358:1596–1600. doi: 10.1126/science.aao3642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gille S., Hänsel U., Ziemann M., Pauly M. Identification of plant cell wall mutants by means of a forward chemical genetic approach using hydrolases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009;106:14699–14704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905434106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou J.-Y., Wang L.-J., Chen S.-P., Hu W.-L., Chen X.-Y. Gene expression and metabolite profiles of cotton fiber during cell elongation and secondary cell wall synthesis. Cell Res. 2007;17:422. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X., Runavot J.-L., Bourot S., Meulewaeter F., Hernandez-Gomez M., Holland C., Harholt J., Willats W.G.T., Mravec J., Knox P. Metabolism of polysaccharides in dynamic middle lamellae during cotton fibre development. Planta. 2019;249:1–17. doi: 10.1007/s00425-019-03107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haigler C.H., Singh B., Wang G., Zhang D. Genetics and Genomics of Cotton. Springer; 2009. Genomics of cotton fiber secondary wall deposition and cellulose biogenesis; pp. 385–417. [Google Scholar]

- Haigler C.H., Betancur L., Stiff M.R., Tuttle J.R. Cotton fiber: a powerful single-cell model for cell wall and cellulose research. Front. Plant Sci. 2012;3:104. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall Q., Cannon M.C. The cell wall hydroxyproline-rich glycoprotein RSH is essential for normal embryo development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2002;14:1161–1172. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harholt J., Sørensen I., Fangel J., Roberts A., Willats W.G.T., Scheller H.V., Petersen B.L., Banks J.A., Ulvskov P. The glycosyltransferase repertoire of the spikemoss Selaginella moellendorffii and a comparative study of its cell wall. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Gomez M.C., Runavot J.-L., Guo X., Bourot S., Benians T.A.S., Willats W.G.T., Meulewaeter F., Knox J.P. Heteromannan and heteroxylan cell wall polysaccharides display different dynamics during the elongation and secondary cell wall deposition phases of cotton fiber cell development. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015;56:1786–1797. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcv101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hijazi M., Velasquez S.M., Jamet E., Estevez J.M., Albenne C. An update on post-translational modifications of hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins: toward a model highlighting their contribution to plant cell wall architecture. Front. Plant Sci. 2014;5:395. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam M.S., Fang D.D., Thyssen G.N., Delhom C.D., Liu Y., Kim H.J. Comparative fiber property and transcriptome analyses reveal key genes potentially related to high fiber strength in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) line MD52ne. BMC Plant Biol. 2016;16:36. doi: 10.1186/s12870-016-0727-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K.L., Cassin A.M., Lonsdale A., Wong G.K.-S., Soltis D.E., Miles N.W., Melkonian M., Melkonian B., Deyholos M.K., Leebens-Mack J. Insights into the evolution of hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins from 1000 plant transcriptomes. Plant Physiol. 2017;174:904–921. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.00295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T. The outer wall of the cotton fiber and its influence on fiber properties. Text. Res. J. 1946;16:249–254. [Google Scholar]

- Kieliszewski M.J., Lamport D.T.A., Tan L., Cannon M.C. Hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins: form and function. Annu. Plant Rev. Plant polysaccharides Biosynth. Bioeng. 2010;41:321–342. [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Ralph J. A gel-state 2D-NMR method for plant cell wall profiling and analysis: a model study with the amorphous cellulose and xylan from ball-milled cotton linters. RSC Adv. 2014;4:7549–7560. [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.J., Triplett B.A. Cotton fiber growth in planta and in vitro. Models for plant cell elongation and cell wall biogenesis. Plant Physiol. 2001;127:1361–1366. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamport D.T.A. Oxygen fixation into hydroxyproline of plant cell wall protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1963;238:1438–1440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamport D.T.A., Kieliszewski M.J., Chen Y., Cannon M.C. Role of the extensin superfamily in primary cell wall architecture. Plant Physiol. 2011;156:11–19. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.169011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamport D.T.A., Miller D.H. Hydroxyproline arabinosides in the plant kingdom. Plant Physiol. 1971;48:454. doi: 10.1104/pp.48.4.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.J., Woodward A.W., Chen Z.J. Gene expression changes and early events in cotton fibre development. Ann. Bot. 2007;100:1391–1401. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Liu D., Tu L., Zhang X., Wang L., Zhu L., Tan J., Deng F. Suppression of GhAGP4 gene expression repressed the initiation and elongation of cotton fiber. Plant Cell Rep. 2010;29:193–202. doi: 10.1007/s00299-009-0812-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Wolfe R., Welch L.R., Domozych D.S., Popper Z.A., Showalter A.M. Bioinformatic identification and analysis of extensins in the plant kingdom. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombard V., Golaconda Ramulu H., Drula E., Coutinho P.M., Henrissat B. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;42:D490–D495. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald S.S., Blaukopf M., Withers S.G. N-acetylglucosaminidases from CAZy family GH3 are really glycoside phosphorylases, thereby explaining their use of histidine as an acid/base catalyst in place of glutamic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:4887–4895. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.621110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzol E., Borassi C., Bringas M., Sede A., Garcia D.R.R., Capece L., Estevez J.M. Filling the gaps to solve the extensin puzzle. Mol. Plant. 2018;11:645–658. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mecchia M.A., Santos-Fernandez G., Duss N.N., Somoza S.C., Boisson-Dernier A., Gagliardini V., Martínez-Bernardini A., Fabrice T.N., Ringli C., Muschietti J.P. RALF4/19 peptides interact with LRX proteins to control pollen tube growth in Arabidopsis. Science (80-) 2017;358:1600–1603. doi: 10.1126/science.aao5467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinert M.C., Delmer D.P. Changes in biochemical composition of the cell wall of the cotton fiber during development. Plant Physiol. 1977;59:1088–1097. doi: 10.1104/pp.59.6.1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkouropoulos G., Shirsat A.H. The unusual Arabidopsis extensin gene atExt1 is expressed throughout plant development and is induced by a variety of biotic and abiotic stresses. Planta. 2003;217:356–366. doi: 10.1007/s00425-003-1002-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Q., Deng P., Saha S., Jenkins J.N., Hsu C.-Y., Abdurakhmonov I.Y., Buriev Z.T., Pepper A., Ma D.-P. Transcriptome analysis of ten-DPA fiber in an upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) line with improved fiber traits from phytochrome A1 RNAi plants. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2017;8:2530. [Google Scholar]

- Moller I., Sørensen I., Bernal A.J., Blaukopf C., Lee K., Øbro J., Pettolino F., Roberts A., Mikkelsen J.D., Knox J.P. High-throughput mapping of cell-wall polymers within and between plants using novel microarrays. Plant J. 2007;50:1118–1128. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller S.R., Yi X., Velásquez S.M., Gille S., Hansen P.L.M., Poulsen C.P., Olsen C.E., Rejzek M., Parsons H., Yang Z. Identification and evolution of a plant cell wall specific glycoprotein glycosyl transferase. ExAD. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:45341. doi: 10.1038/srep45341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguema-Ona E., Vicré-Gibouin M., Gotté M., Plancot B., Lerouge P., Bardor M., Driouich A. Cell wall O-glycoproteins and N-glycoproteins: aspects of biosynthesis and function. Front. Plant Sci. 2014;5:499. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuñez A., Fishman M.L., Fortis L.L., Cooke P.H., Hotchkiss A.T., Jr Identification of extensin protein associated with sugar beet pectin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009;57:10951–10958. doi: 10.1021/jf902162t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Øbro J., Harholt J., Scheller H.V., Orfila C. Rhamnogalacturonan I in Solanum tuberosum tubers contains complex arabinogalactan structures. Phytochemistry. 2004;65:1429–1438. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa-Ohnishi M., Matsushita W., Matsubayashi Y. Identification of three hydroxyproline O-arabinosyltransferases in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013;9:726. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi X., Behrens B.X., West P.R., Mort A.J. Solubilization and partial characterization of extensin fragments from cell walls of cotton suspension cultures (evidence for a covalent cross-link between extensin and pectin) Plant Physiol. 1995;108:1691–1701. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.4.1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasundaram D., Runavot J.-L., Guo X., Willats W.G.T., Meulewaeter F., Selbig J. Understanding the relationship between cotton fiber properties and non-cellulosic cell wall polysaccharides. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao M.Y., Wang X.D., Ni M., Bibi N., Yuan S.N., Malik W., Zhang H.P., Liu Y.X., Hua S.J. Regulation of cotton fiber elongation by xyloglucan endotransglycosylase/hydrolase genes. Genet. Mol. Res. 2011;10:3771–3782. doi: 10.4238/2011.October.27.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y.-H., Zhu S.-W., Mao X.-Z., Feng J.-X., Qin Y.-M., Zhang L., Cheng J., Wei L.-P., Wang Z.-Y., Zhu Y.-X. Transcriptome profiling, molecular biological, and physiological studies reveal a major role for ethylene in cotton fiber cell elongation. Plant Cell. 2006;18:651–664. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.040303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu Y., Aotsuka S., Hasegawa O., Kawada T., Sakuno T., Sakai F., Hayashi T. Changes in levels of mRNAs for cell wall-related enzymes in growing cotton fiber cells. Plant Cell Physiol. 1997;38:375–378. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Showalter A.M., Keppler B., Lichtenberg J., Gu D., Welch L.R. A bioinformatics approach to the identification, classification, and analysis of hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins. Plant Physiol. 2010;153:485–513. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.156554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh B., Avci U., Inwood S.E.E., Grimson M.J., Landgraf J., Mohnen D., Sørensen I., Wilkerson C.G., Willats W.G.T., Haigler C.H. A specialized outer layer of the primary cell wall joins elongating cotton fibers into tissue-like bundles. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:684–699. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.135459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smallwood M., Beven A., Donovan N., Neill S.J., Peart J., Roberts K., Knox J.P. Localization of cell wall proteins in relation to the developmental anatomy of the carrot root apex. Plant J. 1994;5:237–246. [Google Scholar]

- Stafstrom J.P., Staehelin L.A. The role of carbohydrate in maintaining extensin in an extended conformation. Plant Physiol. 1986;81:242–246. doi: 10.1104/pp.81.1.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokumoto H., Wakabayashi K., Kamisaka S., Hoson T. Changes in the sugar composition and molecular mass distribution of matrix polysaccharides during cotton fiber development. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002;43:411–418. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcf048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuttle J.R., Nah G., Duke M.V., Alexander D.C., Guan X., Song Q., Chen Z.J., Scheffler B.E., Haigler C.H. Metabolomic and transcriptomic insights into how cotton fiber transitions to secondary wall synthesis, represses lignification, and prolongs elongation. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:477. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1708-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentin R., Cerclier C., Geneix N., Aguié-Béghin V., Gaillard C., Ralet M.-C., Cathala B. Elaboration of extensin-pectin thin film model of primary plant cell wall. Langmuir. 2010;26:9891–9898. doi: 10.1021/la100265d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasquez S.M., Ricardi M.M., Dorosz J.G., Fernandez P.V., Nadra A.D., Pol-Fachin L., Egelund J., Gille S., Harholt J., Ciancia M. O-glycosylated cell wall proteins are essential in root hair growth. Science (80-) 2011;332:1401–1403. doi: 10.1126/science.1206657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasquez S.M., Marzol E., Borassi C., Pol-Fachin L., Ricardi M.M., Mangano S., Juarez S.P.D., Salter J.D.S., Dorosz J.G., Marcus S.E. Low sugar is not always good: impact of specific O-glycan defects on tip growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2015;168:808–813. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.255521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Wang P., Tu L., Zhu S., Zhang L., Li Z., Zhang Q., Yuan D., Zhang X. Multi-omics maps of cotton fibre reveal epigenetic basis for staged single-cell differentiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:4067–4079. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterkeyn L. Cytochemical localization and function of the 3-linked glucan callose in the developing cotton fibre cell wall. Protoplasma. 1981;106:49–67. [Google Scholar]

- Wendel J.F., Brubaker C., Alvarez I., Cronn R., Stewart J.M. Genetics and Genomics of Cotton. Springer; 2009. Evolution and natural history of the cotton genus; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Li H.-B., Zhu Y.-X. Molecular biological and biochemical studies reveal new pathways important for cotton fiber development. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2007;49:69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.-W., Bian S.-M., Yao Y., Liu J.-Y. Comparative proteomic analysis provides new insights into the fiber elongating process in cotton. J. Proteome Res. 2008;7:4623–4637. doi: 10.1021/pr800550q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.