Abstract

Background

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is a liver disorder that can develop in pregnancy. It occurs when there is a build‐up of bile acids in the maternal blood. It has been linked to adverse maternal and fetal/neonatal outcomes. As the pathophysiology is poorly understood, therapies have been largely empiric. As ICP is an uncommon condition (incidence less than 2% a year), many trials have been small. Synthesis, including recent larger trials, will provide more evidence to guide clinical practice. This review is an update of a review first published in 2001 and last updated in 2013.

Objectives

To assess the effects of pharmacological interventions to treat women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, on maternal, fetal and neonatal outcomes.

Search methods

For this update, we searched Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register, ClinicalTrials.gov, the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (13 December 2019), and reference lists of retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials, including cluster‐randomised trials and trials published in abstract form only, that compared any drug with placebo or no treatment, or two drug intervention strategies, for women with a clinical diagnosis of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy.

Data collection and analysis

The review authors independently assessed trials for eligibility and risks of bias. We independently extracted data and checked these for accuracy. We assessed the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach.

Main results

We included 26 trials involving 2007 women. They were mostly at unclear to high risk of bias. They assessed nine different pharmacological interventions, resulting in 14 different comparisons. We judged two placebo‐controlled trials of ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) in 715 women to be at low risk of bias.

The ten different pharmacological interventions were: agents believed to detoxify bile acids (UCDA) and S‐adenosylmethionine (SAMe); agents used to bind bile acids in the intestine (activated charcoal, guar gum, cholestyramine); Chinese herbal medicines (yinchenghao decoction (YCHD), salvia, Yiganling and Danxioling pill (DXLP)), and agents aimed to reduce bile acid production (dexamethasone)

Compared with placebo, UDCA probably results in a small improvement in pruritus score measured on a 100 mm visual analogue scale (VAS) (mean difference (MD) −7.64 points, 95% confidence interval (CI) −9.69 to −5.60 points; 2 trials, 715 women; GRADE moderate certainty), where a score of zero indicates no itch and a score of 100 indicates severe itching. The evidence for fetal distress and stillbirth were uncertain, due to serious limitations in study design and imprecision (risk ratio (RR) 0.70, 95% CI 0.35 to 1.40; 6 trials, 944 women; RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.08 to 1.37; 6 trials, 955 women; GRADE very low certainty).

We found very few differences for the other comparisons included in this review.

There is insufficient evidence to indicate if SAMe, guar gum, activated charcoal, dexamethasone, cholestyramine, Salvia, Yinchenghao decoction, Danxioling and Yiganling, or Yiganling alone or in combination are effective in treating women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy.

Authors' conclusions

When compared with placebo, UDCA administered to women with ICP probably shows a reduction in pruritus. However the size of the effect is small and for most pregnant women and clinicians, the reduction may fall below the minimum clinically worthwhile effect. The evidence was unclear for other adverse fetal outcomes, due to very low‐certainty evidence. There is insufficient evidence to indicate that SAMe, guar gum, activated charcoal, dexamethasone, cholestyramine, YCHD, DXLP, Salvia, Yiganling alone or in combination are effective in treating women with cholestasis of pregnancy. There are no trials of the efficacy of topical emollients.

Further high‐quality trials of other interventions are needed in order to identify effective treatments for maternal itching and preventing adverse perinatal outcomes. It would also be helpful to identify those women who are mostly likely to respond to UDCA (for example, whether bile acid concentrations affect how women with ICP respond to treatment with UDCA).

Plain language summary

Interventions for treating intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP)

What is the issue?

A liver disorder arising during pregnancy, most often in the last three months, commonly causes itching (pruritus), which can be extremely distressing to the pregnant woman. Bile acids accumulate within the liver and the blood concentration of bile acids is raised, although not always apparent with the symptoms. The signs and symptoms often resolve spontaneously within the first few days after birth, and usually within four to six weeks. Although the condition is poorly understood, there is an association with preterm birth and stillbirth among women with the severest forms of the disease. Many treatments have been suggested. This review is an update of a review first published in 2001 and last updated in 2013.

Why is this important?

The itching can be disabling. Stillbirth and preterm birth are serious adverse outcomes which are important to prevent.

What evidence did we find?

We searched for evidence in December 2019, and identified 26 trials involving 2007 women. The trials assessed nine different interventions, but for most of them the trials were small and had a high risk of bias; we were therefore unable to draw firm conclusions. However, the most widely‐used treatment, ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), for which we identified seven trials (1008 women), included two trials at low risk of bias (755 women). There is now evidence that UDCA probably reduces itching (moderate‐certainty evidence). However, the size of the effect is small and for many pregnant women may not be worthwhile. The evidence for an effect of UCDA on stillbirth or fetal distress is unclear, mainly due to limitations in study design and imprecise results (very low‐certainty evidence).

What does this mean?

Although UDCA has not been shown to prevent the adverse outcomes of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, there is no other effective treatment for this condition, and there is a small reduction in maternal itch.

More high‐quality trials of other treatments are needed in order to identify what is effective for maternal itching and to prevent adverse outcomes. It would also be helpful to identify those women who are mostly likely to respond to UDCA (for example, whether bile acid concentrations affect how women with ICP respond to treatment with UDCA).

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) versus placebo.

| Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA)compared with placebo | ||||||

|

Population: pregnant women with intrahepatic cholestasis Settings: UK (2 RCTs), Chile, China, Finland, Italy, Sweden (one RCT each) Intervention: UDCA Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | UDCA | |||||

| Pruritus score* (points out of 100 mm visual analogue scale) |

The mean of the worst pruritus score in the placebo group ranged from 56.9 to 61.9 | The mean of the worst pruritus score in the intervention groups was 7.64 lower (9.69 lower to 5.60 lower) | 715 (2) | moderatea | *worst score in previous 24 hours | |

| Stillbirth | 9/1000 | 3.51/1000 (0.72 to 17) | RR 0.33 (0.08 to 1.37) | 955 (6) | very lowb,c | There was a small number of events and a wide CI |

| Fetal distress/asphyxial events | 117/1000 | 82/1000 (41 to 164) | RR 0.70 (0.35 to 1.40) | 944 (6) | very lowb,d | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; MD: Mean difference; RR: Risk ratio; UDCA: ursodeoxycholic acid. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aWe downgraded one level for serious imprecision, due to there being only two trials, one relatively small. b We downgraded two levels for very serious limitations in study design, due to two RCTs not having adequate randomisation and a third RCT with high losses to follow‐up. cWe downgraded one level for serious imprecision, due to a small number of events and wide confidence intervals. dWe downgraded one level for serious imprecision, due to wide confidence intervals.

Background

Description of the condition

Introduction and definition

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP: also known as obstetric cholestasis) is a pregnancy‐specific liver condition appearing most often in the third trimester. It is a relatively benign but often very distressing condition for the woman, but it may adversely affect fetal outcome, as seen by associations with preterm labour, fetal distress and stillbirth, particularly in severe cases. The diagnosis of ICP is based on a combination of pruritus (itching), which classically affects palms and soles but may become generalised, but without a rash apart from excoriations, together with increased concentrations of serum bile acids (values usually at least 10 μmol/L, or above the upper limit of the normal range for the local laboratory). Increased concentrations of serum transaminases (e.g. alanine aminotransferase (ALT)) greater than 50 U/L are often seen. There is now movement towards an international consensus that the diagnosis should only be made if serum bile acids are increased, irrespective of whether serum transaminases are increased, either alone or in combination.

Clinical pruritus may precede the development of abnormal biochemistry (Kenyon 2001). Following birth, there is usually spontaneous relief of signs and symptoms within the first few days, although occasionally resolution may take several weeks (EASL guidelines 2009). Ongoing clinical symptoms and abnormal liver biochemical values for longer than six weeks after birth may not be consistent with a primary diagnosis of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, and other causes should be considered. Histopathology of the liver shows non‐specific mild intrahepatic cholestasis with accumulation of bile pigments in hepatocytes and bile duct swelling (Heikkinen 1981). Accumulation of bile acids within the liver increases serum bile acid concentrations, which may cause pruritus, perhaps due to increased availability of brain opiate receptors (Jones 1990), although the fact that pruritus may precede abnormal chemistry, including changes in serum bile acids, suggests that other mechanisms may be at work, potentially mediated through serum autotaxin activity (Kremer 2015) and progesterone sulphated metabolite concentrations (Abu‐Hayyeh 2016).

Epidemiology

The incidence may vary across ethnic groups. It has been reported in fewer than 1% of pregnancies in Central and Western Europe, North America and Australia, in 1% to 2% in Scandinavia and the Baltic states, but can be as high as 5% to 15% in Araucanian Indians in Chile and Bolivia (Lammert 2000).

Pathophysiology

The exact pathophysiology is unknown but genetic, endocrine and environmental factors have been implicated. The role of genetics remains unsubstantiated but in high‐prevalence areas a strong family history is often present (Berg 1986; Eloranta 2001; Qui 1983; Reyes 1976; Shaw 1982). It is thought that mutations of bile acid transporter genes may impair maternal excretion and affect transplacental passage of maternal serum bile acids (Dixon 2017; Milkiewicz 2002). Familial disorders such as progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis and benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis may be linked to intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy by alterations in the binding domains of liver receptors for DNA and oestrogens (Leevy 1997). A higher than anticipated incidence of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy has been found in the mothers of people with these two familial liver disorders (de Swiet 2002).

The precise role of oestrogens is unknown, but their causal role is suggested by the appearance of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy in the third trimester (when oestrogen concentrations are highest), the increased frequency in pregnancies with high oestrogen concentrations (e.g. multiple pregnancies) (Gonzalez 1989), and the resolution of symptoms following the cessation of pregnancy (Germain 2002). Women who develop intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy are at a higher risk of developing cholestasis with any oral contraceptive pill use. This also suggests that oestrogen may be an aetiological factor (de Swiet 2002).

Similarly, the role of progesterone in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy is unclear. While the total serum progesterone concentrations and the amount of progesterone excreted in urine are similar to normal pregnancies, large amounts of sulphated progesterone have been detected in the plasma and urine of women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (Meng 1997). In vitro animal studies suggest that high concentrations of progesterone metabolites induce trans‐inhibition of the bile salt export pump (BSEP), and consequently interfere with bile acid secretion into bile. This leads to intracellular accumulation of bile acids, which disrupt mitochondrial function, and which may explain the role of progesterone metabolites in the aetiopathogenesis of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (Vallejo 2006).

Seasonal variation in the prevalence of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy suggests that environmental factors may have a role (Reyes 1997). Pollutants in pesticides, erucic acid (a constituent of rape‐seed oil) and dietary deficiency of selenium have been suggested as possible environmental factors (Ribalta 1995).

Clinical features

Women present with pruritus without rash, characteristically after 30 weeks' gestation (Kenyon 2002; Reyes 1992). Pruritus often worsens as the pregnancy progresses. Steatorrhoea and dark urine may occur. Jaundice is a rare symptom (de Swiet 2002). Increased rates of postpartum haemorrhage have been postulated to be due to vitamin K deficiency (Johnston 1979; Reid 1976; Reyes 1992). One non‐randomised study reported a higher rate of postpartum haemorrhage in women who had not taken vitamin K compared with those who had (Kenyon 2002). Gallstones may be present more often in affected women (Kirkinen 1984; Ropponen 2006). Women with hepatitis C infection have a higher incidence of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (Locatelli 1999; Paternoster 2002). Pre‐eclampsia and gestational diabetes are seen more commonly in women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (Marathe 2017; Martineau 2014; Wikstrom 2013).

Investigations

The most specific laboratory test for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy is measurement of plasma or serum concentration of total bile acids, which will usually include cholic or chenodeoxycholic acid: values may be 10 to 100 times those found in healthy pregnant women (Bacq 1997; Heikkinen 1981). Increases in serum transaminases are also common (Reyes 1997). Unlike in other cholestatic diseases, increases in serum gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT) are less common (Walker 2002). If there is clinical uncertainty about the diagnosis of ICP, particularly with asymptomatic clinical presentation, then other investigations should be considered. Upper abdominal ultrasound can be performed to exclude gallbladder disease, duct dilatation and other liver pathology. Serology for hepatitis A, B, C, Epstein Barr virus (EBV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV) can help to exclude viral pathology, while an autoimmune screen including anti‐smooth muscle, liver‐kidney microsomal (LKM) and antimitochondrial antibodies can help to identify women with chronic active hepatitis or primary biliary cholangitis (Bacq 1997; Heinonen 1999; Kenyon 2005). There is no evidence that routine testing of all women who present with ICP is needed (Chappell 2019).

Fetal effects

The implication of excess circulating maternal serum bile acids for the fetus is not completely understood. Increased rates of fetal complications, perinatal mortality rates, stillbirths, low birthweight, preterm labour and birth, and fetal distress in labour have been linked with the condition (Alsulyman 1996; Davies 1995; Fisk 1988; Gaudet 2000; Jiang 1986; Johnston 1979; Laatikainen 1975; Ovadia 2019; Reid 1976; Rioseco 1994; Roszkowski 1968; Williamson 2004; Wilson 1979; Ylostalo 1975). There is evidence to suggest an increased incidence of meconium‐stained amniotic fluid in women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (RCOG 2011), and it is more common in those with serum bile acid concentrations greater than 40 µmol/L (Lee 2008). No specific fetal monitoring, such as cardiotocography (CTG), ultrasound or amniocentesis for meconium presence, has been found to be beneficial or accurate in predicting an adverse outcome in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (RCOG 2011). Possible mechanisms for fetal compromise that have been suggested include a toxic effect of bile acids on the fetal myocardium, leading to cardiac dysrhythmia and acute anoxia, as demonstrated in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (Williamson 2001). It has been hypothesised that high bile acid concentrations in the mother may cause bile acid pneumonia in the newborn (Zecca 2006; Zecca 2008).

Description of the intervention

All interventions considered in this review are classified as 'pharmacological interventions', i.e. treatments that use medicines or drugs, and include topical preparations and Chinese herbal medicines.

Topical emollients may provide temporary relief of pruritus for some women, and are widely used (RCOG 2011). Oral antihistamine medications are sometimes prescribed to provide symptom relief, although their role in reducing itching in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy has not been substantiated, and some of the impact may be related to the sedative side‐effects. In the UK, USA and Australia, chlorpheniramine, hydroxyzine, diphenhydramine, cetirizine and promethazine are commonly used as first‐line agents to treat pruritus in women with ICP. Other treatments, aimed at decreasing bile acid production (dexamethasone and phenobarbitone), are now rarely used in UK and Australian practice.

Some agents have been used that bind bile acids in the intestine, facilitating their elimination and preventing enterohepatic recirculation (activated charcoal, guar gum, cholestyramine). Agents binding bile acids in this way have the potential for adverse effects for mothers due to the depletion of vitamin K (Briggs 2001).

Other therapies such as ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) and S‐adenosylmethionine (SAMe) may detoxify bile acids, or change their solubility, thereby allowing increased choleresis and potentially reducing their adverse cellular effects.

Rifampicin has been used outside of pregnancy in the treatment of several cholestatic liver diseases. The mechanisms of its actions may be complementary to those of UDCA and include enhanced bile acid detoxification and elimination (Marschall 2005).

Yinchenghao decoction (YCHD), Salvia, Danxioling and Yiganling are used in Chinese medicine for their hepato‐protective properties. There is little information available on these products.

Side effects (as well as benefits) for the fetus potentially exist for dexamethasone, phenobarbitone, rifampicin, SAMe and UDCA, since they all cross the placenta.

How the intervention might work

The efficacy of topical emollients has not been tested in clinical trials but they seem to provide temporary relief from pruritus in some women and are safe in pregnancy (RCOG 2011). Calamine lotion contains zinc oxide (ZnO) and 0.5% iron oxide (Fe2O3) and has antipruritic and antiseptic properties. One to two per cent menthol in aqueous cream affects A delta sensory nerve fibres and suppresses histamine‐induced itching (Bernhard 1994; Bromma 1995). Diprobase contains liquid paraffin, white soft paraffin, cetomacrogol and cetostearyl alcohol. The principle behind its use is to provide symptomatic relief from itching due to its moisturising properties. Balneum Plus cream contains urea and lauromacrogols; the hydrophilic properties of urea hydrate the skin and the local anaesthetic properties of lauromacrogols cause a soothing effect.

Chlorpheniramine is a first‐generation alkylamine antihistamine. Its use, and that of other H1‐antagonist antihistamines, in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy has not been tested in a clinical trial but it seems to provide symptomatic relief from itching in some women. It can cause sedation but is otherwise safe in pregnancy.

Dexamethasone is a glucocorticoid which decreases the synthesis of fetal and maternal adrenocorticotrophin hormone (ACTH). It also reduces production and secretion of the oestrogen precursors, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and DHEA sulphate, from both maternal and fetal adrenal glands (Kauppila 1979; Simmer 1975). More than 50% of oestrogen in the maternal circulation is derived from the feto‐placental unit. Reduction of maternal oestrogen concentrations may be a mechanism by which it may improve cholestasis (Diac 2006).

The role of phenobarbitone in cholestasis was first demonstrated in 1968 (Cunningham 1968). Animal models suggest that phenobarbitone increases the excretion of bile salts into the biliary tree and enhances bile flow (Klaasen 1970; Robinson 1971).

Activated charcoal is a highly porous carbon compound. It is widely used to treat acute poisoning following oral ingestion, where it binds to the toxin and prevents its absorption from the stomach and intestine. It can effectively adsorb bile salts in vitro (Krasopoulos 1980).

Guar gum is a viscous polysaccharide obtained from guar beans, which helps to hold plant cells together. Its main use is in the food industry where it is used to thicken or add texture to foods and drinks (Insel 2010). It is also used to add thickness in lotions and creams, and to bind ingredients together in tablets, and was widely used as an appetite suppressor in weight loss formulations in the past. Guar gums bind the bile acids to the intestinal contents, which are then expelled from the body (Morgan 1993).

Cholestyramine is a resin that binds to bile acids in the intestine and prevents their reabsorption. Consequently, it may interfere with the absorption of fat‐soluble vitamins, including vitamin K, which is essential for blood coagulation. This may increase the risk of postpartum haemorrhage in the mother and intracranial haemorrhage in the fetus (Sadler 1995).

Rifampicin (RIF) is a semisynthetic antibiotic with a wide range of antimicrobial activity, including for treatment of tuberculosis, where it is a first‐line agent including for treatment of pregnant women (Loto 2012). It has also been shown to have the capacity to reduce serum bile acids in the management of cholestasis outside of pregnancy (Marschall 2005). A systematic review of pharmacological interventions for pruritus in palliative care showed that, in people with cholestatic pruritus, data favoured the use of RIF, with a low incidence of adverse events when compared with placebo (Siemens 2016). There have been no trials comparing UDCA and rifampicin in the treatment of cholestatic pruritus, nor have there been any completed trials in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, although there have been a small number of case reports and one small series (Geenes 2015).

S‐adenosylmethionine (SAMe) is produced from methionine and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in all mammalian cells. The liver is the principal site where it is produced and metabolised (Cantoni 1952). It is an important methyl group donor and plays a crucial role in the biosynthesis of phospholipids, which are important for maintaining the fluidity of hepatic cell membranes and excretion of oestrogen metabolites (Boelsterli 1983). Interference with hepatic SAMe biosynthesis may cause and predispose hepatocytes to injury. Experiments on rat models indicate that SAMe can reverse cholestasis (Stramentinoli 1981). The exact mechanism of action remains unclear.

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) is a naturally‐occurring hydrophilic bile acid. Studies suggest that UDCA displaces endogenous hydrophobic detergent‐like toxic bile acids in cholestatic disorders without disrupting the bile acid pool (Stiehl 1999). UDCA has been credited with cytoprotective and anti‐apoptotic properties (Mitsuyoshi 1999; Rodrigues 1998). Animal studies have shown that UDCA improves hepatocellular and cholangiocellular biliary secretion in cholestatic disorders by post‐transcriptional regulation of the apical transporters BSEP and multidrug resistance protein 2 (MRP2) (Beuers 2001). Women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy treated with UDCA have reduced cord‐blood bile acid concentrations (Brites 2002). This may be due to up‐regulation of the expression of placental MRP2 (Azzaroli 2007).

Yinchenghao decoction (YCHD) is extracted from three different herbs: Artemisia capillaries, Gardenia jasminoides Ellis and Rheum officinale Baill. It was invented two millennia ago and has been used in Chinese medicine to treat a wide range of liver disorders. Down‐regulation of the production of pro‐inflammatory cytokine tumour necrosis factor (TNF) by inhibition of NF‐kappaB activation (Cai 2006), an antifibrotic action, in part due to the inhibitory action on extracellular matrix (ECM) gene expression (Lee 2009), and decreased tumour growth factor 1 (TGF‐1) mRNA expression and inhibition of lipid peroxidation with reduced hepatic collagen accumulation (Lee 2007) have all been postulated as possible mechanisms for its hepato‐protective properties.

Salvia miltiorrhiza, also known as red sage or Danshen, a perennial plant in the genus Salvia of the mint family, is a traditional Chinese medicine. It has been used for more than 2000 years to improve blood circulation and for the treatment of chronic hepatitis and liver fibrosis (Oh 2002). Its hepato‐protective effects are believed to be a result of inhibition of hepatocellular apoptosis induced by bile salts (Oh 2002).

Why it is important to do this review

This is an update of a Cochrane Review first published in 2001 (Burrows 2001) and updated in 2013 (Gurung 2013), which concluded that there was insufficient evidence for any of the treatments for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy so far evaluated in randomised controlled trials. None was found to be consistently effective in resolving maternal pruritus. Since 2013 new trials have been published, including one comparing UDCA with placebo which is larger than all previous trials combined.

Objectives

To assess the effects of pharmacological interventions to treat women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, on maternal, fetal and neonatal outcomes.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials, including cluster‐randomised trials and trials published in abstract form only.

Types of participants

Women stated to have a diagnosis of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP).

Types of interventions

Pharmacological interventions used to treat intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy and its symptoms, compared with placebo or no treatment or another intervention. We include pharmacological interventions or treatments that use medicines or drugs in this review, and include topical preparations and Chinese herbal medicines.

Physical treatments, such as induction of labour, were in the last version of this review (Gurung 2013). We have removed them from this version, and may cover them in a separate review (Timed delivery for treating intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Maternal

Pruritus (scores, change in score, improvement)

Fetal/neonatal

Stillbirths or neonatal deaths

Fetal distress/asphyxial events

Secondary outcomes

Maternal

Liver function, as measured by serum bile acid and serum ALT

Caesarean section

Postpartum haemorrhage

Adverse effects of medication

Fetal/neonatal

Meconium‐stained liquor

Mean gestational age at birth

Spontaneous birth at less than 37 weeks

Total preterm birth at less than 37 weeks (spontaneous and iatrogenic)

Admission to neonatal intensive care unit

Search methods for identification of studies

The following Methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth.

Electronic searches

For this update, we searched Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register by contacting their Information Specialist (13 December 2019)..

The Register is a database containing over 25,000 reports of controlled trials in the field of pregnancy and childbirth. It represents over 30 years of searching. For full current search methods used to populate Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register including the detailed search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL; the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service, please follow this link.

Briefly, Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register is maintained by their Information Specialist and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE (Ovid);

weekly searches of Embase (Ovid);

monthly searches of CINAHL (EBSCO);

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Search results are screened by two people and the full text of all relevant trial reports identified through the searching activities described above is reviewed. Based on the intervention described, each trial report is assigned a number that corresponds to a specific Pregnancy and Childbirth review topic (or topics), and is then added to the Register. The Information Specialist searches the Register for each review using this topic number rather than keywords. This results in a more specific search set that has been fully accounted for in the relevant review sections (Included studies; Excluded studies; Studies awaiting classification; Ongoing studies).

In addition, we searched ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) for unpublished, planned and ongoing trial reports (13 December 2019), using the search methods detailed in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of retrieved studies.

We did not apply any language or date restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For the methods used when assessing the trials identified in the previous version of this review, seeGurung 2013. For this update we used the following methods when assessing the trials identified by the updated search.

Selection of studies

Two review authors (Kate Walker (KW) and Jim Thornton (JT)) independently assessed all the studies identified as a result of the search strategy for potential inclusion. There were no disagreements. We considered studies presented only as abstracts for inclusion on the same basis as studies published in full.

Data extraction and management

JT designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, KW and JT extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or by consulting the other review authors (Philippa Middleton (PM), William Hague (WH), Lucy Chappell (LC)). KW entered data into Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 2014) and JT checked for accuracy.

When information on any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

KW and JT independently assessed risks of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). The two trials for which JT and LC had a conflict of interest (Chappell 2012; Chappell 2019) were assessed by KW and PM. We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by consulting the other assessors.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We describe for each included study whether the method used to generate the allocation sequence was described in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it produced comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random‐number table; computer random‐number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We describe for each included study whether the method used to conceal the allocation sequence and determine whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of assignment, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively‐numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We describe for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and research personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered studies to be at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding could not have affected the results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for research personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We describe for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We describe for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We state whether attrition and exclusions were reported. We also mention the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we re‐included missing data in the analyses.

We assessed methods as having:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data unbalanced across groups; ‘as treated' analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting bias

We describe for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as having:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s prespecified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s prespecified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; the study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other sources of bias

We describe for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias, as having:

low risk of other bias;

high risk of other bias;

unclear risk of other bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether they were likely to impact on the findings. We explored the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we present results as a summary risk ratio (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI).

Continuous data

For continuous data, we have used the mean difference (MD) if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. In future updates, as appropriate, we plan to use the standardised mean difference (SMD) to combine trials that measure the same outcome, but use different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We found no cluster‐randomised trials for this review, although if cluster‐randomised trials had been available, we would have included them. In future updates, if identified and eligible, we will include cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with individually‐randomised trials. We will adjust either their sample sizes or standard errors using the methods described in the Handbook[Section 16.3.4 or 16.3.6] using an estimate of the intra cluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies we noted levels of attrition. We explored the impact of included studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, we analysed the data as far as possible on an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) basis, i.e. we made an attempt to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and all participants were analysed in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau2, I2 and Chi2 statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if the Tau2 is greater than zero and either I2 is greater than 30% or there is a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi2 test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

There were insufficient studies (i.e. less than 10) to investigate reporting biases with funnel plots.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using Review Manager 5 software (RevMan; RevMan 2014). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect, i.e. where trials were examining the same intervention, and we judged the trials’ populations and methods to be sufficiently similar. If there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or if we detected substantial statistical heterogeneity, we used random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary, if we considered an average treatment effect across trials was clinically meaningful. We treated the random‐effects summary as the average of the range of possible treatment effects and we discussed the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect was not clinically meaningful, we did not combine trials.

Where we have used random‐effects analyses, we present the results as the average treatment effect with its 95% confidence interval, and the estimates of Tau2 and I2.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We carried out the following subgroup analyses.

Total serum bile acid concentrations equal to or greater than 40 µmol/L versus total serum bile acid concentrations less than 40 µmol/L.

We used primary outcomes only for the subgroup analysis. In this update we also report a subgroup analysis of one of the secondary outcomes (spontaneous preterm birth) as this was reported by one of the trials (Chappell 2019).

We assessed subgroup differences by interaction tests available within RevMan (RevMan 2014). We report the results of subgroup analyses quoting the Chi2 statistic and P value, and the interaction test I2 value.

Sensitivity analysis

When appropriate, in future updates we will carry out sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of trial quality based on concealment of allocation, by excluding studies with unclear or high risk of bias for allocation concealment.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

For this update we have assessed the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach, as outlined in the GRADE handbook, in order to assess the certainty of the body of evidence relating to the following outcomes for the main comparison (UDCA versus placebo):

Maternal

Pruritus (scores, change in score, improvement)

Fetal/neonatal

Stillbirths or neonatal deaths

Fetal distress/asphyxial events

GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool has been used to import data from Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014) in order to create ’Summary of findings’ tables. We have produced a summary of the intervention effect and a measure of certainty for each of the above outcomes using the GRADE approach. This addresses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the certainty of the body of evidence for each outcome. The evidence can be downgraded from 'high certainty' by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments as per the criteria above.

Results

Description of studies

SeeCharacteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

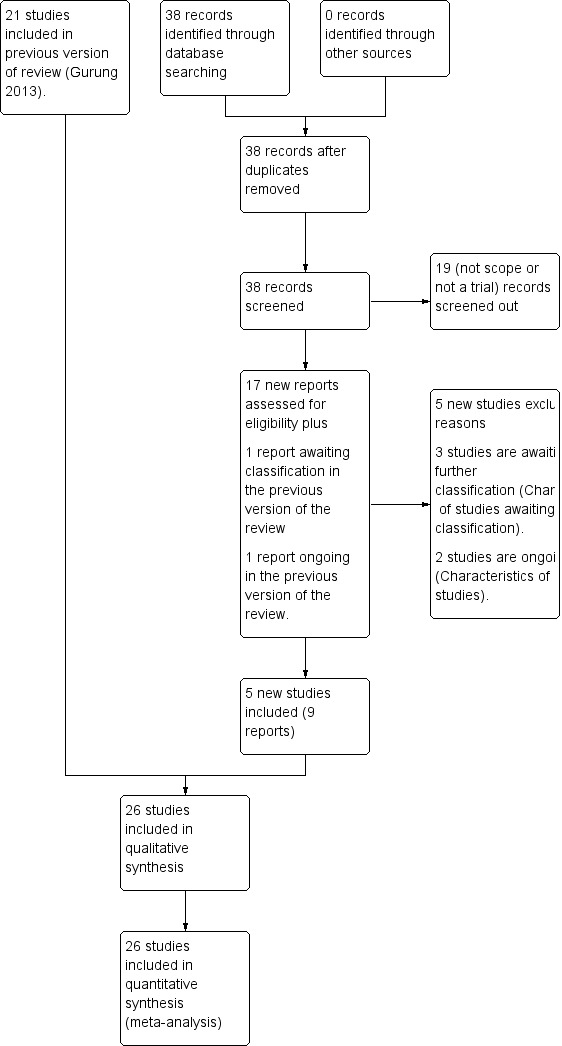

See: Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram

For this update, we retrieved 17 new trial reports to assess. We also reassessed Wang 2003 and Mazzella 2010 that were awaiting classification and ongoing in the previous version of the review. We included five new trials (nine reports) and excluded five. Three trials are awaiting further classification and two are ongoing.

Included studies

The original review (2001) included nine randomised controlled trials (Diaferia 1996; Floreani 1996; Frezza 1984; Frezza 1990; Kaaja 1994; Nicastri 1998; Palma 1997; Ribalta 1991; Riikonen 2000). The 2013 update included 11 new studies (Binder 2006; Fang 2009; Glantz 2005; Huang 2004; Kondrackiene 2005; Liu 2006; Luo 2008; Chappell 2012; Roncaglia 2004; Shi 2002; Zhang 2012). In addition, one study (Leino 1998) was a conference abstract and excluded from the original review (Burrows 2001). This was included in the update.

The updated search identified six new studies, five of which we judged to be eligible for inclusion (Chappell 2019; Joutsiniemi 2014; Sun 2014; Zhang 2015; Wang 2003).

Thus we now include 26 trials involving 2007 women in this review. See table of Characteristics of included studies for a full description.

Participants

All women had a diagnosis of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, based on the presence of pruritus in pregnancy and abnormalities of liver function. The onset of pruritus varied among the studies, occurring before week 19 (Frezza 1984), after week 20 (Chappell 2012; Chappell 2019), after week 28 (Nicastri 1998), after week 29 (Diaferia 1996), after week 32 (Ribalta 1991), after week 33 (Palma 1997), after week 35 (Zhang 2012; Wang 2003), in the second half of pregnancy (Huang 2004), the last trimester (Floreani 1996) or the second or third trimester (Binder 2006; Kondrackiene 2005; Roncaglia 2004; Zhang 2015). In one study (Chappell 2012), women were randomised after week 24, irrespective of the time of onset of gestational pruritus. Eleven studies did not specify a time for onset of pruritus (Frezza 1990; Fang 2009; Glantz 2005; Joutsiniemi 2014; Kaaja 1994; Leino 1998; Liu 2006; Luo 2008; Riikonen 2000; Shi 2002; Sun 2014). Generally, the inclusion criteria stipulated the severity and duration of pruritus, increased serum concentrations of bile acids/salts and/or other liver function assays, and consent to remain in hospital until the birth or to undergo extensive fetal monitoring, while the exclusion criteria stipulated absence of skin disease, chronic liver disease or other abnormalities unrelated to pregnancy. Riikonen 2000 reported that one woman was in the study twice, during successive pregnancies.

Interventions

Nine different pharmacological interventions were compared with placebo, with no treatment or with another intervention. However combination treatments were also evaluated, so we ended up with 14 comparisons (with some trials appearing in more than one comparison):

UDCA versus placebo or no treatment ‐ 10 studies (Chappell 2012; Chappell 2019; Diaferia 1996; Glantz 2005; Joutsiniemi 2014; Leino 1998; Liu 2006; Nicastri 1998; Palma 1997; Wang 2003);

SAMe versus placebo ‐ four studies (Frezza 1984; Frezza 1990; Nicastri 1998; Ribalta 1991);

Guar gum versus placebo ‐ one study (Riikonen 2000);

Activated charcoal versus no treatment ‐ one study (Kaaja 1994);

Dexamethasone versus placebo ‐ one study (Glantz 2005);

UDCA versus SAMe ‐ six studies (Binder 2006; Floreani 1996; Nicastri 1998; Roncaglia 2004; Zhang 2012; Zhang 2015);

UDCA versus dexamethasone ‐ one study (Glantz 2005);

UDCA versus cholestyramine ‐ one study (Kondrackiene 2005);

UDCA+SAMe versus placebo ‐ one study (Nicastri 1998);

UDCA+SAMe versus SAMe ‐ four studies (Binder 2006; Nicastri 1998; Zhang 2012; Zhang 2015);

UDCA+SAMe versus UDCA ‐ six studies (Binder 2006; Luo 2008; Nicastri 1998; Sun 2014; Zhang 2012; Zhang 2015);

UDCA+Salvia versus UDCA ‐ one study (Fang 2009);

Yinchenghao decoction (YCHD) versus SAMe ‐ one study (Huang 2004);

Danxioling Pill (DXLP) versus Yiganling ‐ one study (Shi 2002).

There were no studies identified which examined the use of topical emollients.

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) versus placebo

(Chappell 2012; Chappell 2019; Diaferia 1996; Glantz 2005; Joutsiniemi 2014; Leino 1998; Liu 2006; Nicastri 1998; Palma 1997; Wang 2003)

Participants in Leino 1998 received UDCA 450 mg/day in two doses for 14 days. The treatment and control interventions were identical in two studies (Diaferia 1996 and relevant arms of Nicastri 1998): 600 mg/day UDCA, or placebo (vitamin) given in two oral doses for 20 days (given after 30 weeks' gestation in Diaferia 1996). Participants in Glantz 2005 and Palma 1997 received a higher dose of UDCA or placebo over a longer period of time. UDCA 1000 mg/day or placebo was given as a single daily dose for three weeks in Glantz 2005 and as three divided doses or placebo (starch) in Palma 1997. In Liu 2006, women received UDCA (18 mg/kg body weight) three times a day for two weeks. The control group received a combination of 10% glucose, vitamin C and Inosine for two weeks. It is unclear whether the interventions were administered orally or by a parenteral route. Participants in Chappell 2012 received UDCA 1000 mg daily increased in increments of 500 mg daily every three to 14 days up to a maximum UDCA dose 2000 mg/day if no biochemical or clinical improvement was observed. Participants in Chappell 2019 received UDCA 1000 mg daily or a placebo increased in increments of 500 mg daily every three to 14 days up to a maximum of 2000 mg daily if no biochemical or clinical improvement was observed. Participants in Joutsiniemi 2014 received UDCA 450 mg daily or a placebo for 14 days. Participants in Wang 2003 received UDCA 1.5 g daily for seven days or nothing (i.e. an open‐label trial).

S‐adenosylmethionine (SAMe) versus placebo

(Frezza 1984; Frezza 1990; Nicastri 1998; Ribalta 1991)

In these studies, SAMe 800 mg dissolved in a 500 mL solution of saline (Frezza 1984), 5% dextrose (Frezza 1990; Nicastri 1998) or 5% glucose (Ribalta 1991) was administered as a daily dose intravenously (IV) over the course of three (Ribalta 1991) or four hours (Frezza 1984). The duration of administration was not reported in two studies (Frezza 1990; Nicastri 1998). A lower dose of SAMe 200 mg/day was also compared with placebo (Frezza 1984). The intervention was administered up to the day of delivery (Frezza 1984; Frezza 1990) or for a maximum of 20 days (Nicastri 1998; Ribalta 1991). Placebo treatment was either 5% dextrose solution (Frezza 1990), mannitol (800 mg) in a 5% glucose solution (Ribalta 1991), saline solution (Frezza 1984) or a vitamin solution (Nicastri 1998).

Guar gum versus placebo

Guar gum or placebo (wheat flour) at doses from 5 to 15 g/day (increases in dosage occurring at three‐day intervals) were given in three intermittent doses up until delivery. For the participants to be included in the intervention analysis, they had to take guar gum or placebo for at least 10 days.

Activated charcoal versus no treatment

Activated charcoal as a water suspension was given in a dose of 50 g three times a day for eight days.

Dexamethasone versus placebo

Dexamethasone 12 mg/day was administered as a single daily oral dose for a week, followed by placebo for two weeks. Women in the control group took a single dose of placebo every day for three weeks.

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) versus S‐adenosylmethionine (SAMe)

(Binder 2006; Floreani 1996; Nicastri 1998; Roncaglia 2004; Zhang 2012; Zhang 2015)

These studies differed by dose, administration and duration of intervention. Binder 2006 used the highest dose of UDCA (750 mg/day) and this was administered orally three times a day until birth. In Nicastri 1998 and Roncaglia 2004, 600 mg/day of UDCA was administered as two oral daily doses for 20 days or until delivery respectively. In Floreani 1996, UDCA was given as a single oral dose of 450 mg/day until delivery.

Binder 2006, Floreani 1996, and Roncaglia 2004 administered 1000 mg/day of SAMe but the routes of administration and duration of intervention were different. In Binder 2006, SAMe 500 mg was administered IV twice daily for 12 days and subsequently as 500 mg twice daily oral dose until delivery. In Floreani 1996, SAMe was administered as a single intramuscular (IM) injection daily until birth. In Roncaglia 2004, it was given in two doses by oral route until delivery. In Nicastri 1998, 800 mg/day of SAMe was administered daily in two doses as IV infusions. These were given for a maximum of 20 days.

In Zhang 2012 UDCA (250 mg given orally four times a day) was compared with SAMe (1000 mg IV four times daily) alone. In Zhang 2015 UDCA (250 mg given orally four times a day) was compared with SAMe (1 g IV daily).

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) versus dexamethasone

UDCA 1000 mg was administered as a daily single daily oral dose for three weeks. This was compared with dexamethasone 12 mg/day given as a single oral dose for one week and placebo during weeks two and three.

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) versus cholestyramine

UDCA (8 to 10 mg/kg body weight a day) was compared with cholestyramine (8 g/day). Both treatments were administered orally for two weeks.

Yinchenghao decoction (YCHD) versus S‐adenosylmethionine (SAMe)

YCHD given twice daily orally for three weeks was compared with SAMe IV infusion of 2 x 500 mg daily for three weeks.

Ursodeoxycholic acid and S‐adenosylmethionine (UDCA+SAMe) versus placebo

UDCA (600 mg/day, in two oral doses) plus SAMe (in the stable form of sulphate‐P‐toluenesulphonate diluted in 500 mL 5% dextrose and divided into two IV infusions (800 mg/day)) were compared with placebo (vitamin) administered for a maximum of 20 days.

Ursodeoxycholic acid and S‐adenosylmethionine (UDCA+SAMe) versus S‐adenosylmethionine (SAMe)

(Binder 2006; Nicastri 1998; Zhang 2012; Zhang 2015)

In Nicastri 1998, UDCA (600 mg/day, in two oral doses) plus SAMe ( in the stable form of sulphate‐P‐toluenesulphonate diluted in 500 mL 5% dextrose and divided into two IV infusions (800 mg/day)) were compared with SAMe (as sulphate‐P‐toluenesulphonate diluted in 500 mL 5% dextrose and divided into two IV infusions (800 mg/day) administered for a maximum of 20 days. In Binder 2006, UDCA (3 x 250 mg/day oral doses until delivery) plus SAMe (2 x 500 mg/day given by slow infusion for 14 days) was compared with SAMe (2 x 500 mg/day given by slow infusion for 14 days) alone. In Zhang 2012, UDCA plus SAMe (dose not stated) was compared with SAMe (1000 mg IV four times daily) alone. In Zhang 2015 UDCA (250 mg given orally four times a day) plus SAMe (1 g IV daily) was compared with SAMe (1 g IV daily).

Ursodeoxycholic acid and S‐adenosylmethionine (UDCA+SAMe) versus ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA)

(Binder 2006; Luo 2008; Nicastri 1998; Sun 2014; Zhang 2012; Zhang 2015)

In Binder 2006, UDCA (3 x 250 mg/day oral doses until delivery) plus SAMe (2 x 500 mg/day given by slow infusion for 14 days) was compared with UDCA (3 x 250 mg/day oral doses until delivery) alone. In Zhang 2012, UDCA plus SAMe (dose not stated) was compared with UDCA (250 mg given orally four times daily) alone. In Nicastri 1998, UDCA (600 mg/day, in two oral doses) plus SAMe (800 mg sulphate‐P‐toluenesulphatonate diluted in 500 mL 5% dextrose, in two IV infusions) was compared with UDCA (600 mg/day, in two oral doses) alone administered for a maximum of 20 days. In Luo 2008, SAMe (Transmetil 1 g added to 250 mL 5% glucose administered as an IV infusion once daily) plus UDCA (250 mg oral pill twice daily) were compared with UDCA pill alone (250 mg oral pill twice daily) for 10 days. Participants in both groups received dexamethasone (10 mg once a day orally) for three days before starting the study drugs. In Sun 2014 UDCA (250 mg twice a day orally) combined with SAMe (1 g daily IV) was compared with UDCA (250 mg twice a day orally). In Zhang 2015 UDCA (250 mg given orally four times a day) plus SAMe (1 g IV daily) was compared with UDCA (250 mg given orally four times a day).

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA)+Salvia versus ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA)

Salvia (10 mL in 10% 500 mL dextrose IV injection) and ursodeoxycholic acid (15 mg/kg/day divided into three oral doses a day) was compared with UDCA (same dose as above) only. Both were used for 14 days.

Danxioling pill (DXLP) versus Yiganling

(Shi 2002)

DXLP 9 g/day given three times a day orally for seven days was compared with Yiganling tablets given as four tablets three times a day for seven days.

Outcomes

The main outcomes in all studies included maternal, perinatal, and neonatal morbidity and mortality outcomes.

Study dates, funding and conflicts of interest

For Diaferia 1996; Fang 2009; Frezza 1990; Kaaja 1994; Leino 1998; Luo 2008; Shi 2002; Wang 2003 the dates the study was conducted, the funding source and conflicts of interest were not reported.

Binder 2006 was conducted between January 1999 and March 2004. The study was funded by IGA MZ CR (No. NH/7376‐3). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Chappell 2012 was conducted between October 2008 and April 2010. The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). LCC is funded by a Department of Health‐NHS clinical senior lecturer award, VG was funded by Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust and NIHR research for patient benefit programme, PTS is funded by Tommy’s Charity, and CW is funded by the Biomedical Research Centre at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust; JC is the founder of Obstetric Cholestasis Support UK, a support group for women and families affected by obstetric cholestasis; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Chappell 2019 was conducted between 23 December 2015, and 07 August 2018. The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Programme. The authors declared the following conflicts of interest: LCC, JLB, EJ, RH, and JD report grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), during the conduct of the study. JD also reports grants from NIHR and Nutrinia, outside the submitted work. JGT is a co‐author of the Cochrane Review of treatment for obstetric cholestasis and a co‐author of a previous trial of UDCA to treat ICP.

For Floreani 1996 the dates the study was conducted and conflicts of interest were not reported. The study was partially supported by a Ministerial grant (MURST 60%).

Frezza 1984 was conducted between 1979 and 1982. The funding source and conflicts of interest were not reported.

Glantz 2005 was conducted between February 1999 and January 2002. The study was funded by FoU, Västra Götaland. The following conflicts of interest were reported: Dr Falk Pharma, manufacturers of UDCA supplied UDCA and placebos.

Huang 2004 was conducted in a three‐week period, although the dates are not reported, and the funding source and conflicts of interest were not reported.

Joutsiniemi 2014 was conducted in a two‐year period, although the dates are not reported, and the funding source and conflicts of interest were not reported.

Kondrackiene 2005 was conducted between October 1999 and September 2002. The funding source and conflicts of interest were not reported.

Liu 2006 was conducted between June 2001 and July 2003. The funding source and conflicts of interest were not reported.

Nicastri 1998 was conducted between March 1995 and July 1996. The funding source and conflicts of interest were not reported.

Palma 1997 was conducted between July 1993 and June 1995. The study was funded by FONDECYT, Chile, Grants no. 191‐1107 and 194‐0420. Conflicts of interest were not reported.

Ribalta 1991 was conducted in a two‐year period, although the dates are not reported. The funding source was a Universidad de Chile (grant M‐15001) and FONDECYT (grant 0467/88). Conflicts of interest were not reported.

For Riikonen 2000 the dates the study was conducted were not reported. The study was funded by the Finnish Heart Foundation, Finnish Academy of Medical Sciences, the Paulo Foundation, the Juho Vainio Foundation and the Helsinki University Hospital. Conflicts of interest were that guar gum was received from Orion Company, Helsinki, Finland.

Roncaglia 2004 was conducted between June 1996 and December 2001. The funding source and conflicts of interest were not reported.

Sun 2014 was conducted between January 2012 and February 2014. The funding source and conflicts of interest were not reported.

Zhang 2012 was conducted between July 2009 and March 2011. The funding source and conflicts of interest were not reported.

Zhang 2015 was conducted between January 2012 and February 2014. The funding source and conflicts of interest were not reported.

Excluded studies

Seven studies were excluded. We excluded one study because we were unable to locate it (Elias 2001). Two studies were excluded because the intervention was not a pharmacological intervention (Gautam 2013; Jain 2013). Two studies were excluded because no data were available (Kohari 2013; Liu 1990). One study previously an ongoing study was excluded because it was withdrawn from the trial registry in 2016 (Mazzella 2010). One study was excluded due to a particularly complex pharmacological intervention (Shi 2006). For further details, seeCharacteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

A summary of the risks of bias for the included studies is provided in the following figures: Figure 2; Figure 3; Figure 1.

2.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Apart from four studies (Fang 2009; Glantz 2005; Palma 1997; Shi 2002) which were quasi‐randomised, all other studies were randomised controlled trials. Seven trials reported adequate methods for sequence generation (Chappell 2012; Chappell 2019; Huang 2004; Nicastri 1998; Ribalta 1991; Riikonen 2000; Roncaglia 2004). Three studies (Glantz 2005; Palma 1997; Shi 2002) used alternation by hospital admission in order to generate a random sequence. In Fang 2009, participants were divided into two groups based on the date of hospital admission. Floreani 1996 and Luo 2008 mentioned that the study participants were 'randomly assigned' to the two interventions, but it is unclear how this random sequence was generated. In Frezza 1990, participants were randomised according to a pre‐established code, but it is unclear how this code was derived. It is unclear whether the remaining studies had used a random sequence for intervention allocation.

Allocation concealment was adequate for three trials (Chappell 2012; Chappell 2019; Ribalta 1991). Chappell 2019 and Chappell 2012 used central allocation using a web‐based database. Ribalta 1991 used sequentially‐numbered drug containers of identical appearance.

There was a high risk of possible selection bias in three trials (Fang 2009; Glantz 2005; Shi 2002) and this was unclear in the 19 remaining trials.

Blinding

Blinding of participants or investigators or both was reported in eight studies. In Chappell 2019 participants, clinical care providers, outcome assessors and data analysts were all masked to allocation and it clearly describes how this was achieved. Identical UDCA tablets and placebo tablets were produced and shipped to site pharmacies. Packs were labelled with unique identifiers according to a randomly‐generated sequence known only to the manufacturing unit and the trial programmers. A research team member entered baseline data on a web‐based database at study enrolment and then allocated a pack number using the web‐based randomisation programme, which corresponded to a pack for dispensing by that site’s pharmacy.

In three studies participants and investigators were blinded to group allocation, but no details on blinding of outcome assessment are given (Chappell 2012; Glantz 2005; Palma 1997). For Chappell 2012 investigator, pharmacist and participant were all blinded to group allocation and it was conducted in the same way as described for Chappell 2019. Palma 1997 used identical UDCA and placebo capsules. Glantz 2005 used identical‐looking UDCA, placebo and empty capsules. The empty capsules were filled with dexamethasone at the hospital pharmacy.

Ribalta 1991 was unclear about how they blinded participants and investigators.

In three of these studies, although blinding of both participants or investigators or both was reported (Diaferia 1996; Leino 1998; Riikonen 2000) it is unclear how this was performed.

Two studies were single‐blinded, so that only the investigators were informed of which treatment participants were receiving (Frezza 1984; Frezza 1990) and we therefore judged them to be at high risk. Wang 2003 made no mention of a placebo, and we interpreted this to mean it was an open‐label trial and have therefore judged it to be at high risk.

In nine studies no blinding occurred, as the interventions were administered by different routes and it was therefore not possible to blind, so we have judged them to be high risk (Binder 2006; Fang 2009; Floreani 1996; Huang 2004; Kaaja 1994; Kondrackiene 2005; Luo 2008; Nicastri 1998; Roncaglia 2004). In the four remaining studies it is unclear whether the participants or investigators or both were blinded to trial allocation (Liu 2006; Shi 2002; Sun 2014; Zhang 2012).

Blinding of outcome assessors was reported in one study (Chappell 2019).

Blinding of outcome assessors was not reported in 24 studies and we therefore judged them to be at unclear risk of bias (Binder 2006; Chappell 2012; Diaferia 1996; Fang 2009; Floreani 1996; Frezza 1984; Frezza 1990; Glantz 2005; Huang 2004; Joutsiniemi 2014; Kaaja 1994; Kondrackiene 2005; Liu 2006; Luo 2008; Nicastri 1998; Palma 1997; Ribalta 1991; Riikonen 2000; Roncaglia 2004; Shi 2002; Sun 2014; Wang 2003; Zhang 2012; Zhang 2015).

Incomplete outcome data

Twelve of the 26 studies had a low risk of attrition bias as there were no losses to follow‐up (Binder 2006; Chappell 2012; Chappell 2019; Frezza 1984; Huang 2004; Kaaja 1994; Kondrackiene 2005; Luo 2008; Nicastri 1998; Roncaglia 2004; Shi 2002; Wang 2003).

In Shi 2002, outcomes were reported for 25 participants (86%) for serum alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST), for 27 participants (93%) for alkaline phosphatase (ALP), for 21 participants (72%) for serum bilirubin concentrations out of 29 participants receiving Danxioling, and for 16 of 29 participants (55%) for serum bilirubin concentrations in the Yiganling group.

Five of the 26 studies had a high risk of attrition bias as the losses to follow‐up were unreported (Fang 2009; Floreani 1996; Liu 2006; Palma 1997; Zhang 2015). Outcomes were reported in 15 of 25 participants randomised (63%) in Palma 1997. Palma 1997 excluded from the analysis nine women who delivered before completion of two weeks of treatment.

Nine of the 26 studies had an unclear risk of attrition bias due to a lack of information about losses to follow‐up (Diaferia 1996; Frezza 1990; Glantz 2005; Joutsiniemi 2014; Leino 1998; Ribalta 1991; Riikonen 2000; Sun 2014; Zhang 2012). Outcomes were reported for 39 of 48 participants randomised (81%) in Riikonen 2000, and for 18 of 20 (90%) in Ribalta 1991. The number of participants analysed in the results was unclear in Leino 1998. Zhang 2012 reported 20 cases to have been eliminated and not included in the analysis. However, It was unclear how many of these from each randomised group were lost to follow‐up (Zhang 2012), as only the total number of cases eliminated from the analysis was reported.

Selective reporting

Three of the 26 studies had a low risk of selective reporting (Chappell 2012; Chappell 2019; Huang 2004), as all the prespecified outcomes were reported. Ten of the 26 studies had an unclear risk of selective reporting (Binder 2006; Diaferia 1996; Glantz 2005; Kondrackiene 2005; Leino 1998; Luo 2008; Roncaglia 2004; Shi 2002; Sun 2014; Zhang 2012) as the trials were unregistered. Thirteen of the 26 studies had a high risk of selective reporting (Fang 2009; Floreani 1996; Frezza 1984; Frezza 1990; Joutsiniemi 2014; Kaaja 1994; Liu 2006; Nicastri 1998; Palma 1997; Ribalta 1991; Riikonen 2000; Wang 2003; Zhang 2015), as either one or more outcomes of interest were reported incompletely or there was a failure to report key outcomes such as perinatal mortality.

While most trials reported maternal pruritus after treatment, variable and incomplete reporting (together with variance in measurement parameter reported) precluded pooling of data for this outcome.

The other primary outcomes of perinatal mortality and fetal distress were not reported in any of the trials. In addition, several trials reported some outcomes only in graphical form.

Other potential sources of bias

Eleven of the 26 studies had a low risk of additional sources of bias (Binder 2006; Chappell 2012; Chappell 2019; Kaaja 1994; Kondrackiene 2005; Luo 2008; Nicastri 1998; Ribalta 1991; Riikonen 2000; Roncaglia 2004; Shi 2002) where no other additional sources of bias were identified by the authors.

Six of the 26 studies had an unclear risk of additional sources of bias (Diaferia 1996; Frezza 1990; Leino 1998; Liu 2006; Sun 2014; Zhang 2012), due to a lack of information.

Nine of the 26 studies had a high risk of other potential sources of bias (Fang 2009; Floreani 1996; Frezza 1984; Glantz 2005; Huang 2004; Joutsiniemi 2014; Palma 1997; Wang 2003; Zhang 2015). In Fang 2009 it is unclear why there are 72 women in the experimental group and 58 women in the control group, with insufficient detail given on randomisation to be sure that this imbalance is a result of randomisation. In Floreani 1996 there was some concern about the analyses chosen and reported. In Glantz 2005 the planned sample size reported in the paper was 240 (80 per group). No explanation was given for stopping after 130 participants had been recruited. In Huang 2004 there was an imbalance in the numbers of women randomised to each group. In Palma 1997 the sample size was data‐driven, and in Zhang 2015 we have concerns about the absence of any missing data. In Frezza 1984 there was some concern about the analyses chosen and reported. In Joutsiniemi 2014 no justification was given for the sample size of 20 women and there was inconsistent reporting of the recruitment duration.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

1. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) versus placebo

Nine trials (Chappell 2012; Chappell 2019; Diaferia 1996; Glantz 2005; Joutsiniemi 2014; Leino 1998; Liu 2006; Nicastri 1998; Palma 1997) involving 1037 women looked at this comparison. Wang 2003 reported on UDCA versus no treatment.

Primary outcomes (maternal)

Pruritus

All nine trials (1037 women) comparing UDCA and placebo reported this outcome. Four studies (830 women) used a 100 mm visual analogue scale (VAS), four studies (105 women) evaluated itching on a 0 ‐ 4 categorical scale, and one study (18 women) did not elaborate on the methods used to assess pruritus. Studies that used the 0 ‐ 4 scale (0 = absence of pruritus, 1 = occasional pruritus, 2 = discontinuous pruritus every day, with prevailing asymptomatic lapses, 3 = discontinuous pruritus with prevailing symptomatic lapses, and 4 = constant pruritus) analysed the data as a continuous outcome, which is not ideal as the assumption of normality on a short scale will not be met. We therefore planned to dichotomise the data by classifying a pruritus score of 0 ‐ 2 as mild pruritus, and 3 ‐ 4 as severe pruritus. We also planned to dichotomise pruritus outcomes after the end of the intervention as 'improvers' and 'non‐improvers'. Only Palma 1997 allowed dichotomisation of data. We could not pool dichotomous results from any of these trials, due to the differing methods of measuring and reporting pruritus.

We were only able to pool results from two studies (Chappell 2012; Chappell 2019) out of three reporting a pruritus score using a 100 mm VAS. Pooled results from the two studies (715 women) reported a small reduction in pruritus score (out of 100) for UDCA compared with placebo: mean difference (MD) −7.64, 95% confidence interval (CI) −9.69 to −5.60; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.1. It is worth noting that the 95% CI around the effect was only 9 mm, i.e. smaller than the minimum worthwhile treatment effect for most participants and doctors surveyed.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: UDCA versus placebo, Outcome 1: Mean of worst itching scores over preceding 24 hours between randomisation and delivery

Results that we were able to pool or present in forest plot or combine in meta‐analysis:

In Palma 1997, a weekly assessment of pruritus was performed in all the study participants by the same clinician using the 0 ‐ 4 scoring system. They reported a significant improvement in pruritus score after two weeks (P < 0.01; 15 women) and three weeks (P = 0.02; 15 women) of treatment with UDCA compared with placebo. Data for improvement in pruritus score were presented in a forest plot as a graph, although they represent findings from a single study. Similar numbers of women (seven of the eight women in the UDCA group and five of the seven women in the placebo group) showed a reduction in pruritus score after three weeks (risk ratio (RR) 1.23, 95% CI 0.72 to 2.10; Analysis 1.2); all seven 'improvers' in the UDCA group had low scores (under 1.5) compared with two of the five 'improvers' in the placebo group.

Chappell 2012 prespecified in their trial protocol, published before data unblinding, that their primary outcome was to be the mean of all worst itching scores in the preceding 24 hours (100 mm VAS) measured between randomisation and delivery. The authors of this trial surveyed participants and obstetricians: each group considered that the mean minimum worthwhile improvement would be a 30 mm difference, reported within the main trial publication.bChappell 2012 reported the mean of average itching scores over the preceding 24 hours between randomisation and delivery, and showed a small reduction in pruritus (MD −18.60, 95% CI −27.52 to −9.68; (Analysis 1.3)), but the 95% CI around the effect was still less than 30 mm.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: UDCA versus placebo, Outcome 2: Pruritus improvement

We were unable to pool the results or present the data in forest plots for the following trials, and have therefore summarised the findings as reported by the studies:

In Diaferia 1996, pruritus was assessed before treatment (day 0) and at five‐day intervals thereafter, on a 0 ‐ 4 scale. Pruritus score was reported as mean and standard deviation (SD) at day 0 and day 20, favouring UDCA over placebo.

In Glantz 2005, no difference in pruritus score (100 mm VAS) was seen between the UDCA and placebo groups after three weeks of treatment (94 women; no P value reported). However, in the 23 women with serum bile acids at least 40 μmol/L (subsequently defined as severe cholestasis), the pruritus score fell to a mean of about 15 in the UDCA group compared with a mean of about 52 in the placebo group.

In Joutsiniemi 2014 (20 women), the pruritus score fell to a mean of 2.5 in the UDCA group compared with a mean of 7.5 in the placebo group. No SDs were reported in the paper.

Leino 1998 reported a significant improvement in pruritus scores within two weeks in the UDCA group.

In Liu 2006, pruritus was evaluated on a 0 ‐ 4 scale. Results were reported as mean and SD at trial entry and two weeks later. After 14 days of treatment, a reduction in the pruritus scores was observed in the UDCA group compared with the placebo group.

In Nicastri 1998, pruritus was evaluated by the participant every three days up to 24 hours after delivery using the 0 ‐ 4 scoring system. The change in pruritus score after 20 days of treatment was analysed as a continuous outcome and reported as mean and SD. A significant reduction in pruritus score was observed with both the UDCA and placebo groups.

In Wang 2003, itching was reported on a four‐point scale (0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate not requiring drug treatment, 3 severe requiring drug treatment). The timing was not reported. Treatment with UDCA appeared to have a large effect. Distribution was from 'no treatment' 14 women with moderate and eight women severe itch versus 'UDCA' in which four women had moderate itch and none severe itch.

Primary outcomes (fetal/neonatal)

Stillbirth

Six studies (955 women) reported stillbirth, with zero events in both groups for two studies (Chappell 2012; Joutsiniemi 2014). The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of UDCA on stillbirth because of limitations in study design and very few events reported: four out of the six studies reported seven stillbirths in total, (1/480 versus 6/475; average RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.08 to 1.37; random‐effects analysis; 955 women; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: UDCA versus placebo, Outcome 4: Stillbirth

In Wang 2003, two women had "fetal death", classified by us as stillbirth, in the no‐treatment group. We rated the study as being at high risk of bias in most domains, with many expected data items missing, and a number of the other reported results deemed by us as implausible.

In Glantz 2005, a woman on clomipramine for long‐term depressive disorder experienced itching from 33 weeks' gestation. After going into spontaneous labour at week 38, intrauterine death was diagnosed. Her serum bile acid concentrations were 16 µmol/L, both at trial inclusion and two weeks later. It is unclear from the information provided in the report whether the stillbirth could be attributable to intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy.