Abstract

Background

Crohn's disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal tract, in which the pathogenesis is believed to be partly influenced by the gut microbiome. Probiotics can be used to manipulate the microbiome and have therefore been considered as a potential therapy for CD. There is some evidence that probiotics benefit other gastrointestinal conditions, such as irritable bowel syndrome and ulcerative colitis, but their efficacy in CD is unclear. This is the first update of a Cochrane Review previously published in 2008.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and safety of probiotics for the induction of remission in CD.

Search methods

The following electronic databases were searched: MEDLINE (from inception to 6 July 2020), Embase (from inception to 6 July 2020), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), The Cochrane IBD Review Group Specialised Trials Register, World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry, and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared probiotics with placebo or any other non‐probiotic intervention for the induction of remission in CD were eligible for inclusion.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data and assessed the methodological quality of included studies. The primary outcome was clinical remission. Risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for dichotomous outcomes.

Main results

There were two studies that met criteria for inclusion. One study from Germany had 11 adult participants with mild‐to‐moderate CD, who were treated with a one‐week course of corticosteroids and antibiotics (ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily and metronidazole 250 mg three times a day), followed by randomised assignment to Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain GG (two billion colony‐forming units per day) or corn starch placebo. The other study from the United Kingdom (UK) had 35 adult participants with active CD (CDAI score of 150 to 450) randomised to receive a synbiotic treatment (comprised of freeze‐dried Bifidobacterium longum and a commercial product) or placebo. The overall risk of bias was low in one study, whereas the other study had unclear risk of bias in relation to random sequence generation, allocation concealment, and blinding. There was no evidence of a difference between the use of probiotics and placebo for the induction of remission in CD (RR 1.06; 95% CI 0.65 to 1.71; 2 studies, 46 participants) after six months. There was no difference in adverse events between probiotics and placebo (RR 2.55; 95% CI 0.11 to 58.60; 2 studies, 46 participants). The evidence for both outcomes was of very low certainty due to risk of bias and imprecision.

Authors' conclusions

The available evidence is very uncertain about the efficacy or safety of probiotics, when compared with placebo, for induction of remission in Crohn's disease. There is a lack of well‐designed RCTs in this area and further research is needed.

Keywords: Adult, Humans, Anti-Bacterial Agents, Anti-Bacterial Agents/therapeutic use, Bifidobacterium longum, Ciprofloxacin, Ciprofloxacin/therapeutic use, Crohn Disease, Crohn Disease/microbiology, Crohn Disease/therapy, Gastrointestinal Microbiome, Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus, Metronidazole, Metronidazole/therapeutic use, Placebos, Placebos/adverse effects, Probiotics, Probiotics/adverse effects, Probiotics/therapeutic use, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Remission Induction

Plain language summary

Probiotics for the treatment of active Crohn's disease

What is the aim of this review?

The aim of this Cochrane Review was to find out whether probiotics can induce remission in people with Crohn's disease. We analysed information from two studies to answer this question.

Key messages

It is unclear whether probiotics are better than placebo (dummy pill). No serious adverse events occurred in either study.

What was studied in the review?

Crohn's disease is a medical condition that causes inflammation of the bowels and can lead to symptoms of ulcers in the mouth, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, obstruction, fistulisation (tunnels between the bowels and nearby organs), abscesses, malnutrition, low haemoglobin (blood) levels, and fatigue. There is some evidence to suggest that an imbalance in the bacteria of the gut is a cause of the disease. Probiotics, which are live microorganisms, could alter the bacteria of the gut and possibly reduce inflammation.

What are the main results of the review?

We searched for randomised controlled trials (RCTs; clinical studies where people are randomly placed into one of two or more treatment groups) comparing probiotics with placebo. There were two RCTs, with information on 46 people. The trials looked at adults. It is unclear whether probiotics are different to placebo for inducing remission of Crohn's disease. It is unclear whether probiotics lead to a difference in adverse events (minor and serious) when compared with placebo.

Conclusion

This review found two studies that examined and showed no benefit of probiotics for the treatment of active Crohn's disease. Since the studies were very small, no definite conclusions can be made at this time. Probiotics were generally well tolerated; there was just one side effect leading to the stopping of treatment with probiotics, but details of this were not given. With the evidence presented in these studies, we are unable to make conclusions as to the effectiveness of probiotics. Better designed studies, with more participants, are needed.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

This review is up‐to‐date as of 6 July 2020.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Probiotics compared to placebo for induction of remission in Crohn's disease.

| Probiotics compared to placebo for induction of remission in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: induction of remission in Crohn's disease Setting: medical centers in Germany and UK Intervention: probiotics Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with Probiotics | |||||

| Induction of remission | Study population | RR 1.06 (0.65 to 1.71) |

46 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW1,2 | ||

| 455 per 1000 | 482 per 1000 (295 to 777) | |||||

| Adverse events leading to withdrawal | Study population | RR 2.55 (0.11 to 58.60) | 35 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW1,2 | ||

| < 1 per 1,000 | < 1 per 1,000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded one level due to unclear risk of bias

2 Downgraded two levels due to serious imprecision (22 events and 57 participants)

Background

Description of the condition

Crohn's disease (CD) is a chronic relapsing, remitting inflammatory condition that can affect any segment along the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the anus. Symptoms of CD may include oral ulcers, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, obstruction, fistulisation to surrounding tissues, abscesses, malnutrition, and anaemia. The diagnosis and monitoring of CD is predominantly performed via endoscopic and histologic examination, although these can be complemented by use of imaging, serologic, and fecal data. There is no known cure for CD and treatment is largely focused on the induction and maintenance of remission (quiescent disease), correcting malnutrition, addressing complications, and improving the quality of life for patients. In children, a major additional goal is to facilitate normal growth and pubertal development, which are frequently impeded. The incidence of CD is approximately 20 per 100,000 person‐years in North America and 13 per 100,000 person‐years in Europe (Molodecky 2012). There has been a progressive increase in incidence and prevalence throughout the world, particularly in regions where CD was historically not common (e.g. Asia, the Middle East, South America). Although the aetiology of CD is still unknown, its pathogenesis is believed to involve the interaction between genetic and environmental factors. In particular, the gut microbiome may play a role in disease pathogenesis and activity, thus prompting great interest in the potential use of probiotics as a therapeutic strategy via microbiome manipulation (Shouval 2017).

Description of the intervention

Probiotics consist of live microorganisms that, by definition, should benefit health in humans. Common microorganisms that have been used as probiotics include Lactobacillus spp, Bifidobacterium spp, Streptococcus salivarius, Escherichia coli Nissle 1917, and yeasts (e.g. Saccharomyces boulardii) (Sartor 2005). There has been an increasing interest in the use of probiotics for gastrointestinal diseases, as they are considered safe and easily accessible.

How the intervention might work

Given the association between dysbiosis and CD, there is a hypothesised role for probiotics in restoring eubiosis and perhaps improving intestinal inflammation. Probiotics are believed to work through competitive action with commensal and pathogenic flora and by influencing the immune response (Shanahan 2000). Lactobacillus, one of the more popular constituents of probiotics, is thought to secrete bacteriocin and block the adherence of harmful bacteria (Corr 2007; Mukherjee 2015). As such, probiotics have been examined in diseases related to gut barrier dysfunction and immune‐mediated manifestations, such as childhood diarrhoea (Pochapin 2000; Lai 2019), atopic dermatitis (Isolauri 2000; Navarro‐López 2018), and eczema (Schmidt 2019). There is additionally limited evidence of efficacy of probiotics in ulcerative colitis (Kaur 2020; Iheozor‐Ejiofor 2020), pouchitis (Nguyen 2019), and CD (Guslandi 2000; Campieri 2000).

Why it is important to do this review

The primary mode of treatment for CD involves the use of immunosuppressants, including immunomodulators (e.g. azathioprine, 6‐mercaptopurine, methotrexate) and biologic therapies (e.g. infliximab, vedolizumab, ustekinumab). These drugs are not always effective (Colombel 2010; Limketkai 2017) and may expose patients to potentially increased risks, such as infection, bone marrow suppression, cutaneous and noncutaneous malignancy, and metabolic complications (Click 2019). Consequently, complementary and alternative treatments for CD have been sought. The previous version of this Cochrane Review found only found one eligible small study with 11 participants (Butterworth 2008). There was insufficient evidence to make any conclusions about whether probiotics were effective to treat CD. This review will update the prior review with any new studies that may have emerged over the past decade on the use of probiotics for the induction of remission in CD.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and safety of probiotic supplementation for the induction of remission in Chron's disease.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs)

Types of participants

All patients with active CD at the time of study entry, as defined by a recognised CD activity index, endoscopy, histopathology, or radiology.

Types of interventions

The intervention was probiotics, either alone or in combination with other therapies, administered orally in any form (e.g. drink, powder, capsule). The control was placebo, other non‐probiotic therapies, or no intervention.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Clinical remission, as defined by the primary studies

Secondary outcomes

Disease improvement (clinical response, corticosteroid withdrawal, endoscopic remission, histology scores, biochemical markers of inflammation, quality‐of‐life scores)

Escalation of therapy (addition of therapy, surgery)

Adverse events (number of adverse events, withdrawal due to adverse events)

Search methods for identification of studies

A comprehensive search for relevant RCTs was performed independently of the search from the previous review. The search strategy is outlined in Appendix 1.

Electronic searches

The following electronic databases were searched: MEDLINE (from inception to 6 July 2020), Embase (from inception to 6 July 2020), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), The Cochrane Gut Review Group Specialised Trials Register, World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry, and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Searching other resources

Handsearches were performed of conference proceedings from the Falk Symposium, Digestive Disease Week (DDW), American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Annual Scientific Meeting, Crohn's & Colitis Congress (CCC), European Crohn's & Colitis Organisation (ECCO) Congress, and the United European Gastroenterology Week (UEGW). Additional studies were identified by checking the references section of published trials and review articles on probiotics for treatment of CD. Communication via email, formal letter, or telephone was addressed to lead authors of relevant ongoing or unpublished studies.

Data collection and analysis

This review was performed according to the methods outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2017).

Selection of studies

Study selection was performed using Covidence. Two review authors examined all citations and abstracts derived from the electronic search strategy and independently selected trials meeting the inclusion criteria. After the initial screen, full‐text articles of the selected trials were obtained for further scrutiny. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion or by consulting a third author where necessary.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction was carried out independently by two review authors, using piloted forms. The data collected included information on the study design, participants, intervention, comparator, and outcomes. Discrepancies in data extraction were discussed and, if necessary, a third review author was consulted. Data were then entered into the review file by two authors.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The review authors independently carried out a 'Risk of bias' assessment of the included studies. The Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2017) was used to assess the following domains.

Random sequence generation

Allocation concealment

Blinding of participants and personnel

Blinding of outcome assessment

Incomplete outcome data

Selective outcome reporting

Other sources of bias

We considered subjective outcomes separately in our assessment of blinding and incompleteness of data. Studies were judged to be at high, low, or unclear risk of bias for each domain assessed. We judged the risk of bias across studies as follows.

Low risk of bias (plausible bias unlikely to seriously alter the results) if all domains are at low risk of bias

Unclear risk of bias (plausible bias that raises some doubt about the results) if one or more domains are at unclear risk of bias

High risk of bias (plausible bias that seriously weakens confidence in the results) if one or more domains are at high risk of bias

Measures of treatment effect

The treatment effects of dichotomous outcomes were expressed as risk ratios.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the participant. Studies involving multiple trial arms would have been handled according to methods proposed in Higgins 2017. Unit of analysis issues arising from the measurement of outcomes at different time points were considered.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted study authors for missing data. Where possible, intention‐to‐treat analysis was applied. Missing standard deviations were calculated from other reported data (such as P values, confidence intervals, and standard error) where possible. However, missing data did not have to be imputed. In reporting adverse events, we assumed the 'worst case' to avoid under‐reporting. For instance, we assumed that minor and serious adverse events were related to the intervention.

Assessment of heterogeneity

The decision to pool the results of individual studies depended on an assessment of clinical and methodological heterogeneity. If we considered studies sufficiently homogeneous for data pooling, we assessed statistical heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plots, and using the Chi2 test with a significance level at P value less than 0.1. We also used the I2 statistic, for which we based our interpretations on those suggested by Higgins 2017:

0% to 40%: might not be important;

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90%; may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity

Assessment of reporting biases

Various reporting biases were avoided by undertaking an extensive literature search without restrictions on publication date or language. Study protocols and trial registrations were used in assessing studies for selective reporting. We did not assess publication bias with a funnel plot due to there only being two included studies.

Data synthesis

Data were analysed using Review Manager 5.4. For dichotomous outcomes, risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals were derived for each study. The results of included studies were combined for each outcome, if appropriate. We used a random‐effects model for pooled data and considered not pooling data if we encountered considerable heterogeneity (I2 value of 75% or more) across studies. However, data not amenable to pooling would have been presented in a narrative summary.

We used the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of evidence based on the primary outcome of clinical remission (Schünemann 2011). The four levels of evidence certainty were "high", "moderate", "low", or "very low". "High certainty" suggests that we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. "Moderate certainty" suggests we are moderately confident in the effect estimate. "Low certainty" suggests that our confidence in the effect estimate is limited. "Very low certainty" suggests that we have very little confidence in the effect estimate. The level of certainty was downgraded based on risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness, or publication bias. Where there was sufficient evidence, we prepared 'Summary of findings' tables for our main comparisons. Two review authors independently produced Table 1.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

There were inadequate data to perform a subgroup analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

There were inadequate data to perform a sensitivity analysis.

Results

Description of studies

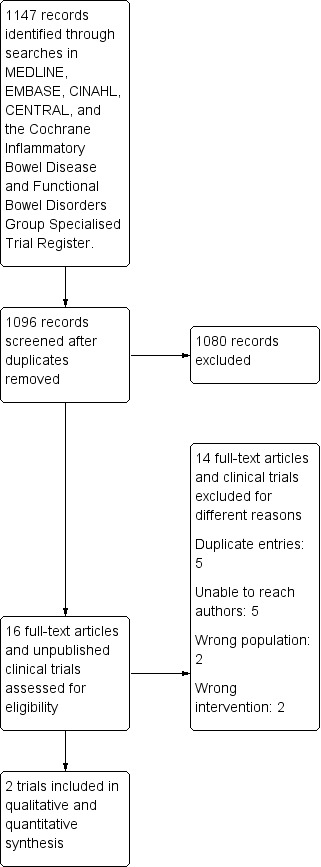

There were 16 potentially relevant published studies and clinical trials registrations identified for full‐text review after title and abstract screening (Figure 1). We excluded 14 studies. One study included patients with active and quiescent CD (Yılmaz 2019). One study did not differentiate between patients with CD and ulcerative colitis (Ye 2017). Two studies used the wrong intervention: all participants received probiotics in one study (Plein 1993), and in the other study, corticosteroids were provided in the intervention arm but not in the control arm (Su 2018). Another study did not have adequate data and we were unable to obtain more data from the trial authors (Day 2012). Four clinical trial registrations had an unclear status that we were unable to confirm with the authors (ACTRN12614000465651; NCT00367705; NCT00374374; NCT01548014). Five clinical trial registrations were considered duplicate entries.

1.

PRISMA study flow diagram.

After full‐text review, there were two studies that met the criteria for inclusion (Schultz 2004; Steed 2010). This adds one new study to the previous version of this review.

Schultz 2004 included 11 adult participants with active mild‐to‐moderate CD (Crohn's Disease Activity Index (CDAI) score of 150 to 300). Participants were treated with a one‐week course of corticosteroids and antibiotics (ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily and metronidazole 250 mg three times a day), followed by randomised assignment to Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain GG (two billion colony‐forming units per day) or corn starch placebo. Clinical remission was defined as a CDAI score of less than 150 within the six‐month follow‐up period. Sustained remission was defined as remission at six months.

Steed 2010 included 35 adult participants with active CD (CDAI score of 150 to 450), randomised to receive a synbiotic treatment or placebo. The synbiotic treatment was a formulation of pro‐ and prebiotics. This study used the combination of 2 x 1011 freeze‐dried Bifidobacterium longum and 6 g Synergy I (Orafti, Tienen, Belgium) twice daily. Clinical remission was defined as a CDAI score of less than 150 or a drop in CDAI score of more than 75 from baseline.

The two studies did not have evidence of statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 0%), although there was substantial methodological heterogeneity between them.

Risk of bias in included studies

Figure 2 outlines the 'Risk of bias' assessments for the included studies. Schultz 2004 was a randomised double‐blind trial, although there were no details provided on random sequence generation, allocation concealment, and blinding of participants and outcome assessors. This led to an unclear risk of bias in these domains. Steed 2010 provided details on random sequence generation (a random numbers table was used by an independent clinician otherwise not involved with the study) and blinding of participants and outcome assessors. There was no information in either study to suggest attrition or reporting bias; all outcome data for all participants was reported, and there was appropriate reporting of key outcomes specified in their methods, despite the lack of a protocol for both studies.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Clinical remission

There was no statistically significant difference between probiotics and placebo for the induction of remission in CD (risk ratio [RR] 1.06; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.65 to 1.71; 2 studies, 46 participants) (Figure 3). Due to the risk of bias and small sample size, the certainty of this evidence was very low (Table 1). In Steed 2010, the mean CDAI scores dropped significantly in the synbiotic group (219 ± 75 to 147 ± 74, P = 0.020) but did not change in the placebo group (249 ± 79 to 233 ± 155, P = 0.810).

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Probiotics versus placebo, outcome: 1.1 Induction of remission.

Escalation of therapy

The data were unavailable to assess this outcome.

Adverse events

In Steed 2010, two participants discontinued synbiotic use due to unreported side effects (one participant) and intolerance (one participant). There were no reported adverse effects in the placebo arm. In Schultz 2004, no adverse events were reported in the 11 participants who took part in the induction and maintenance phases of the study. There was no difference in adverse events between probiotics and placebo (RR 2.55; CI 0.11 to 58.60; 2 studies, 46 participants). The evidence is of very low certainty due to risk of bias and imprecision.

Discussion

Probiotics have previously been shown to be helpful in the treatment of ulcerative colitis and other gastrointestinal disorders, which would support the hypothesis that microbiome manipulation could benefit inflammatory bowel diseases. However, despite the theoretical potential of probiotics for the treatment of CD, the pooled analyses in this review did not find a benefit of probiotics for induction of remission. If true, the reason for the disparity of benefit from the use of probiotics in the two types of inflammatory bowel diseases would need clarification. One possible explanation may relate to the differing nature of inflammation between the two diseases: CD is generally characterised by transmural inflammation with potential to form strictures and fistulae, while ulcerative colitis is limited to superficial epithelial inflammation. Another possibility may relate to the choice of probiotics: the reviewed studies for CD only included Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain GG and Bifidobacterium longum. Other bacterial species or even multi‐strain probiotics could possibly instead be more effective. For ulcerative colitis, a meta‐analysis of single‐strain probiotics including Bifidobacterium strains or Escherichia coli were not found to be effective for inducing remission (Shen 2014). On the other hand, a multi‐strain probiotic that also included Bifidobacterium strains was demonstrated to be effective for induction of remission. Moreover, this review's findings are limited by the great paucity of data on the use of probiotics for CD. This review included only two studies and 57 participants, leading to a high risk of type II error of not being adequately powered to detect a significant difference. There was substantial methodologic heterogeneity between the two studies and the certainty of available evidence was graded as very low. In this setting, the benefit — or lack thereof — of probiotics for induction of remission in CD is still unknown and no conclusions can be drawn at this time.

There has been very little research progress over the past decade. This update to the original systematic review published in 2008 only adds one more study for inclusion. There are additionally several dated clinical trials registrations that have not yet been published (we could not reach the investigators for status updates). Probiotics have been studied in a number of areas of inflammatory bowel diseases, on which there are Cochrane Reviews pending publication at the time of writing. However, it is possible that the scientific community has already deemed probiotics as unsuitable for CD and has therefore abandoned further study in this area. This may nonetheless be a premature assessment, as further investigation is clearly needed to conclude whether probiotics do or do not help induce remission in CD.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The avaiable evidence was to uncertain to provide information on the efficacy or safety of probiotics for the induction of remission in Crohn's disease.

Implications for research.

This review highlights the need for good quality, adequately powered randomised controlled trials to investigate the efficacy and safety of probiotics for the induction of remission in Crohn's disease. Given that investigation in ulcerative colitis has found some evidence for the efficacy of probiotics, future research is warranted.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 6 July 2020 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | One study (Steed 2010) was added. Conclusions are unchanged. |

| 6 July 2020 | New search has been performed | New search performed on 6 July 2020. Risk of bias and GRADE assessments were performed. Summary of Findings table was added. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2007 Review first published: Issue 3, 2008

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 12 May 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format |

| 21 April 2008 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

Funding for MG was provided through a larger NIHR Cochrane Programme Grant in the UK.

We acknowledge the following peer referees who provided comment to updated review: Dr Siddharth Singh (peer referee), and Ms Sandra Zelinsky (consumer reviewer). We thank Jessica Sharp for copy‐editing the review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Electronic Search Strategy

Embase (Ovid database)

1. random$.tw.

2. factorial$.tw.

3. (crossover$ or cross over$ or cross‐over$).tw.

4. placebo$.tw.

5. single blind.mp.

6. double blind.mp.

7. triple blind.mp.

8. (singl$ adj blind$).tw.

9. (double$ adj blind$).tw.

10. (tripl$ adj blind$).tw.

11. assign$.tw.

12. allocat$.tw.

13. crossover procedure/

14. double blind procedure/

15. single blind procedure/

16. triple blind procedure/

17. randomized controlled trial/

18. Or/1‐17

19. Exp Crohn disease/

20. Crohn*.mp.

21. IBD.mp.

22. Inflammatory bowel disease*.mp.

23. Or/19‐22

24. exp Probiotics/

25. exp Synbiotics/

26. exp Lactobacillus/

27. lactobacilli*.tw.

28. bacill*.tw.

29. exp Bifidobacterium/

30. (bifidus or bifidobacter*).tw.

31. exp Streptococcus thermophilus/

32. streptococc*.tw.

33. exp Lactococcus/

34. exp Bacillus subtilis/

35. exp Enterococcus/

36. exp Enterococcus faecium/ or Enterococcus faecalis/

37. exp Saccharomyces/

38. leuconostoc*.tw.

39. pediococc*.tw.

40. bulgarian bacillus*.tw.

41. (beneficial adj3 bacter*).tw.

42. (Escherichia coli or "E. coli").tw.

43. Yeast.tw.

44. (fungus or fungi).tw.

45. (VSL# 3 or VSL 3).tw.

46. Or/24‐45

47. 18 and 23 and 46

Medline (Ovid database)

1. random$.tw.

2. factorial$.tw.

3. (crossover$ or cross over$ or cross‐over$).tw.

4. placebo$.tw.

5. single blind.mp.

6. double blind.mp.

7. triple blind.mp.

8. (singl$ adj blind$).tw.

9. (double$ adj blind$).tw.

10. (tripl$ adj blind$).tw.

11. assign$.tw.

12. allocat$.tw.

13. randomized controlled trial/

14. or/1‐13

15. Exp Crohn disease/

16. Crohn*.mp.

17. IBD.mp.

18. Inflammatory bowel disease*.mp.

19. Or/15‐18

20. exp Probiotics/

21. exp Synbiotics/

22. exp Lactobacillus/

23. lactobacilli*.tw.

24. bacill*.tw.

25. exp Bifidobacterium/

26. (bifidus or bifidobacter*).tw.

27. exp Streptococcus thermophilus/

28. streptococc*.tw.

29. exp Lactococcus/

30. exp Bacillus subtilis/

31. exp Enterococcus/

32. exp Enterococcus faecium/ or Enterococcus faecalis/

33. exp Saccharomyces/

34. leuconostoc*.tw.

35. pediococc*.tw.

36. bulgarian bacillus*.tw.

37. (beneficial adj3 bacter*).tw.

38. (Escherichia coli or "E. coli").tw.

39. Yeast.tw.

40. (fungus or fungi).tw.

41. (VSL# 3 or VSL 3).tw.

42. Or/20‐41

43. 14 and 19 and 42

Cochrane CENTRAL

#1 MeSH: [Crohn’s Disease] explode all trees

#2 Inflammatory bowel disease

#3 IBD

#4 #1 or #2 or #3

#5 MeSH descriptor: [Probiotics] explode all trees

#6 MeSH descriptor: [Synbiotics] explode all trees

#7 MeSH descriptor: [Lactobacillus] explode all trees

#8 Lactobacilli*

#9 Bacill*

#10 MeSH descriptor: [Bifidobacterium] explode all trees

#11 bifidus*

#12 bifidobacter*

#13 MeSH descriptor: [Streptococcus thermophilus] explode all trees

#14 streptococc*

#15 MeSH descriptor: [Lactococcus] explode all trees

#16 MeSH descriptor: [Bacillus subtilis] explode all trees

#17 MeSH descriptor: [Enterococcus] explode all trees

#18 MeSH descriptor: [Enterococcus faecium] explode all trees

#19 MeSH descriptor: [Enterococcus faecalis] explode all trees

#20 MeSH descriptor: [Saccharomyces] explode all trees

#21 leuconostoc*

#22 pediococc*

#23 bulgarian bacillus*

#24 beneficial adj3 bacter*

#25 Escherichia coli or "E. coli"

#26 Yeast

#27 fungus or fungi

#28 VSL# 3 or VSL 3

#29 #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #19 or #20 or #21 or #22 or #23 or #24 or #25 or #26 or #27 or #28

#30 #4 and #29

Cochrane CENTRAL

#1 MeSH: [Crohn’s Disease] explode all trees

#2 Inflammatory bowel disease

#3 IBD

#4 #1 or #2 or #3

#5 MeSH descriptor: [Probiotics] explode all trees

#6 MeSH descriptor: [Synbiotics] explode all trees

#7 MeSH descriptor: [Lactobacillus] explode all trees

#8 Lactobacilli*

#9 Bacill*

#10 MeSH descriptor: [Bifidobacterium] explode all trees

#11 bifidus*

#12 bifidobacter*

#13 MeSH descriptor: [Streptococcus thermophilus] explode all trees

#14 streptococc*

#15 MeSH descriptor: [Lactococcus] explode all trees

#16 MeSH descriptor: [Bacillus subtilis] explode all trees

#17 MeSH descriptor: [Enterococcus] explode all trees

#18 MeSH descriptor: [Enterococcus faecium] explode all trees

#19 MeSH descriptor: [Enterococcus faecalis] explode all trees

#20 MeSH descriptor: [Saccharomyces] explode all trees

#21 leuconostoc*

#22 pediococc*

#23 bulgarian bacillus*

#24 beneficial adj3 bacter*

#25 Escherichia coli or "E. coli"

#26 Yeast

#27 fungus or fungi

#28 VSL# 3 or VSL 3

#29 #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #19 or #20 or #21 or #22 or #23 or #24 or #25 or #26 or #27 or #28

#30 #4 and #29

Clinicaltrials.gov

1. Probiotics and Crohn’s Disease (19)

2. Probiotics and Inflammatory bowel disease (43)

WHO trials registry

1. Probiotics and Crohn’s Disease (14)

2. Probiotics and Inflammatory bowel disease (14)

IBD specialized register

1. Probiotics and Crohn’s Disease (3)

2. Probiotics and Inflammatory bowel disease (0)

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Probiotics versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Induction of remission | 2 | 46 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.65, 1.71] |

| 1.2 Adverse events leading to withdrawal | 2 | 46 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.55 [0.11, 58.60] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Probiotics versus placebo, Outcome 1: Induction of remission

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Probiotics versus placebo, Outcome 2: Adverse events leading to withdrawal

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Schultz 2004.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods |

Study design: randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial Setting: University of Regensburg (Regensburg, Germany) |

|

| Participants |

Inclusion: mild‐to‐moderate CD (CDAI 150‐300) Exclusion: none listed Age: not reported Sex: not reported Number randomised (n = 11): 5 (Group 1); 6 (Group 2) |

|

| Interventions |

Group 1: one week of corticosteroids and antibiotics (ciprofloxacin 500 mg bid, metronidazole 250 mg tid), followed by 2 x 109 CFU/day of Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain GG (CAG Functional Foods, Omaha, NE) Group 2: one week of corticosteroids and antibiotics, followed by placebo |

|

| Outcomes |

Duration of follow‐up: 24 weeks Primary outcome: sustained remission Secondary outcomes 1. Remission 2. Relapse 3. CDAI 4. CRP 5. Tolerability 5. SIde effects |

|

| Notes |

Funding source: partly funded by Deutsche Morbus Crohn und Colitis ulcerosa Vereinigung e.V. (DCCV) Conflicts of interest: none declared |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | There were no details on random sequence generation and no response to email enquiry. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | There were no details on allocation concealment and no response to email enquiry. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | There were no details on the methods of blinding and no response to email. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | There were no details on whether outcome assessment was blinded and no response to email. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Attrition rates appeared to be low, and balanced, and all attrition was reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The trial registration/protocol was not available, although the intended outcomes specified in the methods were reported and these were as expected. |

| Other bias | Low risk | The groups appeared to be balanced. |

Steed 2010.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods |

Study design: randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial Setting: Ninewells Hospital (Dundee, United Kingdom) |

|

| Participants |

Inclusion: adults aged between 18 and 79 with CD (CDAI 150‐450) Exclusion: pregnancy, alterations to medications within last 3 months, antibiotic treatment within last 3 months, indeterminate colitis, UC, short bowel syndrome, use of commercially available prebiotic or probiotic within the last 3 months Age: mean 46.3 years (Group 1); 49.0 years (Group 2) (analysis set) Sex: 13 male / 11 female (analysis set) Number randomised (n = 35): Group 2 (19); Group 2 (16) |

|

| Interventions |

Group 1: 2 x 1011 freeze‐dried Bifidobacterium longum and 6 g Synergy I (Orafti, Tienen, Belgium) bid Group 2: placebo |

|

| Outcomes |

Duration of follow‐up: 6 months Primary outcome: mucosal tumour necrosis factor‐alpha (TNF‐α) Secondary outcomes: 1. Remission (CDAI < 150 or drop in CDAI > 75 from baseline) 2. Clinical relapse (increase in CDAI ≥ 100, CDAI score > 450, steroid prescription, hospitalisation, surgery) 3. Histology score 4. IBD Questionnaire 5. Adverse events |

|

| Notes |

Funding source: Government Chief Scientist Office, Scotland, United Kingdom Conflicts of interest: none |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation was performed using a table of random digits by an independent party. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | There were no details on allocation concealment and no response to email enquiry. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "All study personnel and participants were blinded to treatment assignment" and "(t)he appearance of the synbiotic and placebo were identical". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "All study personnel and participants were blinded to treatment assignment" and "(t)he appearance of the synbiotic and placebo were identical". |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Attrition was balanced across groups, relatively low and all reasons reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The intended outcomes specified in the methods were reported and these were as expected. |

| Other bias | Low risk | The groups appeared to be balanced. |

bid: two times a day CD: Crohn's disease CDAI: Crohn's Disease Activity Index CFU: colony‐forming unit CRP: C‐reactive protein IBD: inflammatory bowel disease tid: three times a day UC: ulcerative colitis

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| ACTRN12614000465651 | Authors contacted on 30 May 2019, with no response |

| Day 2012 | Clinical response and remission rates not reported according to treatment arm. Authors contacted on 2 June 2019, with initial response but none thereafter |

| NCT00367705 | Authors contacted on 30 May 2019, without response |

| NCT00374374 | Authors contacted on 31 May 2019, without response |

| NCT01548014 | Authors contacted on 15 June 2019, without response |

| Plein 1993 | All patients received probiotics during the induction phase |

| Su 2018 | Probiotic arm received corticosteroids, which the control arm did not receive |

| Ye 2017 | Outcomes were not divided according to IBD type: CD and UC |

| Yılmaz 2019 | Study criteria included patients with active and quiescent CD |

CD: Crohn's disease IBD: inflammatory bowel disease UC: ulcerative colitis

Differences between protocol and review

There are several differences in the methods between the current update and the original review, as follows.

Manufacturers of probiotics were not contacted for data on any unpublished trials, as these were felt to have been adequately captured in the clinical trials registries.

A PRISMA flow diagram was added.

'Risk of bias' assessments were included.

The certainty of data was assessed using GRADE methodology.

A 'Summary of findings' table was added

Contributions of authors

Berkeley N Limketkai performed screening of abstracts and titles, screening of full‐text articles, 'Risk of bias' assessments, statistical analyses, GRADE analysis, data interpretation, manuscript preparation, critical revision of the manuscript, and approval of the final manuscript.

Anthony K Akobeng supported manuscript preparation, critical revision of the manuscript, and approval of the final manuscript.

Morris Gordon performed adjudication in the screening and data extraction phases, GRADE analysis, data interpretation, manuscript preparation, critical revision of the manuscript, and approval of the final manuscript.

Akinlolu Adedayo Adepoju performed screening of abstracts and titles, screening of full‐text articles, 'Risk of bias' assessments, data interpretation, manuscript preparation, critical revision of the manuscript, and approval of the final manuscript.

Sources of support

Internal sources

None, USA

None, UK

External sources

No sources of support supplied

Declarations of interest

Berkeley N Limketkai has no known declarations of interest to declare.

Anthony K Akobeng has no known declarations of interest to declare.

Morris Gordon Since August 2016, I have received travel fees to attend international scientific and training meetings from Pharma companies. These grants included no honoraria, inducement, advisory role or any other relationship and were restricted to the travel and meeting related costs of attending such meetings. These include: DDW (Digestive Disease Week) May 2017, World Congress of Gastroenterology October 2017, DDW May 2018, Advances in IBD December 2018, DDW May 2019. The companies include: Biogaia (2017‐19), Ferring (2018), Allergan (2017), synergy (bankrupt ‐ 2018) and Tillots (2017‐19).None of these companies have had any involvement in any works completed by me and I have never had any payments for any other activites for them, as confirmed below. From these date onwards, I have made a personal undertaking to take no further funds from any pharmaceutical or formula company in any form for travel or other related activities. This is to lift the limitations such funding has on my ability to act as a first and corresponding author on reviews, in line with the Cochrane policies on such matters and is reported in line with these policies. These current declarations will expire over the next 3 years and this statement updated regularly to reflect this.

Akinlolu Adedayo Adepoju has no known declarations of interest to declare.

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Schultz 2004 {published data only}

- Schultz M, Timmer A, Herfarth HH, Sartor RB, Vanderhoof JA, Rath HC. Lactobacillus GG in inducing and maintaining remission of Crohn's disease. BMC Gastroenterology 2004;4(5). [PMID: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Steed 2010 {published data only}

- Steed H, Macfarlane GT, Blackett KL, Bahrami B, Reynolds N, Walsh SV, et al. Clinical trial: the microbiological and immunological effects of synbiotic consumption - a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study in active Crohn's disease. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2010;32(7):872-83. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

ACTRN12614000465651 {published data only}

- ACTRN12614000465651. Single centre, open label Phase 1/Phase 2 study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of Dietzia C79793-74 in moderate to severe Crohn's disease. www.anzctr.org.au/Trial/Registration/TrialReview.aspx?id=366224 (first received 30 May 2019).

Day 2012 {published data only}

- Day AS, Leach ST, Lemberg DA, Judd TA, Baba K, Hill RJ. The probiotic VSL#3 in children with active Crohn disease. Gastroenterology 2012;142(5):S-378. [Google Scholar]

NCT00367705 {published data only}

- NCT00367705. Double-blind placebo controlled trial of VSL#3 in children with Crohn's disease. clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00367705 (first received 30 May 2019). [Google Scholar]

NCT00374374 {published data only}

- NCT00374374. Treatment with Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Lactobacillus acidophilus for patients with active colonic Crohn’s disease. clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00374374 (first received 30 May 2019). [Google Scholar]

NCT01548014 {published data only}

- NCT01548014. The effect of a probiotic preparation (VSL#3) plus infliximab in children with Crohn's disease. clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01548014 (first received 30 May 2019). [Google Scholar]

Plein 1993 {published data only}

- Plein K, Hotz J. Therapeutic effects if Saccharomyces boulardii on mild residual symptoms in a stable phase of Crohn's disease with special respect to chronic diarrhoea - a pilot study. Zeitschrift für Gastroenterologie 1993;31(2):129-34. [PMID: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Su 2018 {published data only}

- Su H, Kang Q, Wang H, Yin H, Duan L, Liu Y, et al. Effects of glucocorticoids combined with probiotics in treating Crohn's disease on inflammatory factors and intestinal microflora. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine 2018;16(4):2999-3003. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ye 2017 {published data only}

- Ye J, Wang W, Wu M, Zhang J. Suffasalarin combined with probiotics for treatment of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: effect on prognosis and inflammatory factors. World Chinese Journal of Digestology 2017;25(3):293-7. [Google Scholar]

Yılmaz 2019 {published data only}

- Yılmaz İ, Dolar ME, Özpınar H. Effect of administering kefir on the changes in fecal microbiota and symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease: a randomized controlled trial. Turkish Journal of Gastroenterology 2019;30(3):242-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Butterworth 2008

- Butterworth AD, Thomas AG, Akobeng AK. Probiotics for induction of remission in Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006634.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Campieri 2000

- Campieri M, Rizzello F, Venturi A, Poggioli G, Ugolini F, Helwig U, et al. Combination of antibiotic and probiotic treatment is efficacious in prophylaxis of post-operative recurrence of Crohn's disease: a randomized controlled study vs mesalamine. Gastroenterology 2000;118:A4179. [Google Scholar]

Click 2019

- Click B, Regueiro M. Managing risks with biologics. Current Gastroenterology Reports 2019;21:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Colombel 2010

- Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, Mantzaris GJ, Kornbluth A, Rachmilewitz D, et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn's disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2010;362:1383-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Corr 2007

- Corr SC, Li Y, Riedel CU, O'Toole PW, Hill C, Gahan CG. Bacteriocin production as a mechanism for the antiinfective activity of Lactobacillus salivarius UCC118. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2007;104:7617-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Covidence [Computer program]

- Covidence. Version Accessed 10 January 2019. Melbourne, Australia: Veritas Health Innovation.Available at covidence.org.

Guslandi 2000

- Guslandi M, Mezzi G, Sorghi M, Testoni PA. Saccharomyces boulardii in maintenance treatment of Crohn's disease. Digestive Diseases and Sciences 2000;45:1462-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2017

- Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 5.2.0 (updated June 2017). Cochrane, 2017. Available from training.cochrane.org/handbook.

Iheozor‐Ejiofor 2020

- Iheozor-Ejiofor Z, Kaur L, Gordon M, Baines PA, Sinopoulou V, Akobeng AK. Probiotics for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2020, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007443.pub3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Isolauri 2000

- Isolauri E, Arvola T, Sutas Y, Moilanen E, Salminen S. Probiotics in the management of atopic eczema. Clinical & Experimental Allergy 2000;30:1605-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kaur 2020

- Kaur L, Gordon M, Baines PA, Iheozor-Ejiofor Z, Sinopoulou V, Akobeng AK. Probiotics for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2020, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005573.pub3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lai 2019

- Lai HH, Chiu CH, Kong MS, Chang CJ, Chen CC. Probiotic Lactobacillus casei: effective for managing childhood diarrhea by altering gut microbiota and attenuating fecal inflammatory markers. Nutrients 2019;11(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Limketkai 2017

- Limketkai BN, Parian AM, Chen PH, Colombel JF. Treatment with biologic agents has not reduced surgeries among patients with Crohn's disease with short bowel syndrome. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2017;15:1908-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Molodecky 2012

- Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalenceof the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based onsystematic review. Gastroenterology 2012;142:46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mukherjee 2015

- Mukherjee S, Ramesh A. Bacteriocin-producing strains of Lactobacillus plantarum inhibit adhesion of Staphylococcus aureus to extracellular matrix: quantitative insight and implications in antibacterial therapy. Journal of Medical Microbiology 2015;64:1514-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Navarro‐López 2018

- Navarro-López V, Ramírez-Boscá A, Ramón-Vidal D, Ruzafa-Costas B, Genovés-Martínez S, Chenoll-Cuadros E, Carrión-Gutiérrez M, Horga de la Parte J, Prieto-Merino D, Codoñer-Cortés FM. Effect of oral administration of a mixture of probiotic strains on SCORAD Index and use of topical steroids in young patients with moderate atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial.. JAMA Dermatology 2018;154(1):37-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nguyen 2019

- Nguyen N, Zhang B, Holubar SD, Pardi DS, Singh S. Treatment and prevention of pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2019, Issue 11. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001176.pub5] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pochapin 2000

- Pochapin M. The effect of probiotics on Clostridium difficile diarrhea. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2000;95(1 Suppl):S11-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Review Manager [Computer program]

- Review Manager (RevMan 5). Version 5.4. Copenhagen, Denmark: Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020.

Sartor 2005

- Sartor RB. Probiotic therapy of intestinal inflammation and infections. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology 2005;21:44-50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schmidt 2019

- Schmidt RM, Pilmann Laursen R, Bruun S, Larnkjaer A, Mølgaard C, Michaelsen KF, Høst A. Probiotics in late infancy reduce the incidence of eczema: A randomized controlled trial.. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology 2019;30(3):335-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schünemann 2011

- Schünemann H, Hill S, Guyatt G, et al. The GRADE approach and Bradford Hill's criteria for causation. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 2011;65:392-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shanahan 2000

- Shanahan F. Probiotics and inflammatory bowel disease: is there a scientific rationale? Inflammatory Bowel Disease 2000;6:107-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shen 2014

- Shen J, Zuo ZX, Mao A. Effect of probiotics on inducing remission and maintaining therapy in ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease, and pouchitis: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Inflammatory Bowel Disease 2014;20:21-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shouval 2017

- Shouval DS, Rufo PA. The role of environmental factors in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel diseases: a review.. JAMA Pediatrics 2017;171(10):999-1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]