Abstract

Background

Infectious keratitis is an infection of the cornea that can be caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi, protozoa, or parasites. It may be associated with ocular surgery, trauma, contact lens wear, or conditions that cause deficiency or loss of corneal sensation, or suppression of the immune system, such as diabetes, chronic use of topical steroids, or immunomodulatory therapies. Photoactivated chromophore for collagen cross‐linking (PACK‐CXL) of the cornea is a therapy that has been successful in treating eye conditions such as keratoconus and corneal ectasia. More recently, PACK‐CXL has been explored as a treatment option for infectious keratitis.

Objectives

To determine the comparative effectiveness and safety of PACK‐CXL with standard therapy versus standard therapy alone for the treatment of bacterial keratitis.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Trials Register) (2019, Issue 7); Ovid MEDLINE; Embase.com; PubMed; Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information database (LILACS); ClinicalTrials.gov; and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP). We did not use any date or language restrictions in the electronic search for trials. We last searched the electronic databases on 8 July 2019.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi‐RCTs, and controlled clinical trials (CCTs) of PACK‐CXL for bacterial keratitis. We included quasi‐RCTs and CCTs as we anticipated that there would not be many RCTs eligible for inclusion.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors working independently selected studies for inclusion in the review, assessed trials for risk of bias, and extracted data. The primary outcome was proportion of participants with complete healing at four to eight weeks. Secondary outcomes included visual acuity, morphology, adverse events, and treatment failure at four to eight weeks.

Main results

We included three trials (two RCTs and one quasi‐RCT) in this review for a total of 59 participants (59 eyes) with bacterial keratitis. Trials were all single‐center and were conducted in Egypt, Iran, and Thailand between 2010 and 2014. It is very uncertain whether PACK‐CXL with standard antibiotic therapy is more effective than standard antibiotic therapy alone for re‐epithelialization and complete healing (risk ratio (RR) 1.53, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.88 to 2.66; participants = 15). We judged the certainty of the evidence to be very low due to the small sample size and high risk of selection and performance bias. The high risk of selection bias reflects the overall review. Masking of participants was not possible for the surgical arm. No participant had a best‐corrected visual acuity of 20/100 or better at eight weeks (very low certainty evidence). There is also no evidence that use of PACK‐CXL with standard therapy results in fewer instances of treatment failure than standard therapy alone (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.05 to 4.98; participants = 32). We judged the certainty of evidence to be low due to the small sample size and high risk of selection bias. There were no adverse events reported at 14 days (low certainty evidence). Data on other outcomes, such as visual acuity and morphological characteristics, could not be compared because of variable time points and specific metrics.

Authors' conclusions

The current evidence on the effectiveness of PACK‐CXL for bacterial keratitis is of low certainty and clinically heterogenous in regard to outcomes. There are five ongoing RCTs enrolling 1136 participants that may provide better answers in the next update of this review. Any future research should include subgroup analyses based on etiology. A core outcomes set would benefit healthcare decision‐makers in comparing and understanding study data.

Plain language summary

Corneal collagen cross‐linking for infectious keratitis

What is the aim of this review? The aim of this Cochrane Review was to find out the effect of photoactivated chromophore for collagen cross‐linking (PACK‐CXL), a potential treatment for people with bacterial infectious keratitis. Infectious keratitis is an infection of the cornea, which is the clear, dome‐shaped tissue on the front of the eye. We collected and analyzed all relevant studies to answer this question and found three relevant studies.

Key messages There is no evidence that PACK‐CXL combined with standard antibiotics (medications that treat bacterial infection) is more or less effective than standard antibiotics alone in regard to complete healing and treatment failure. Five ongoing trials (1136 participants) may provide better answers in the next update of this review.

What was studied in this review? PACK‐CXL uses ultraviolet light from a special machine to strengthen the cornea. This treatment is called 'cross‐linking' because it promotes the binding of collagen fibers in the eye. The collagen fibers work like support beams to keep the cornea stable.

What are the main results of this review? We included three studies in this review that compared PACK‐CXL combined with standard antibiotics versus standard antibiotics alone. The studies had a total of 59 participants with bacterial keratitis (59 eyes). Follow‐up was conducted between 14 to 120 days after treatment. The studies were conducted in Egypt, Iran, and Thailand between 2010 and 2014.

There is no evidence that PACK‐CXL with standard antibiotics is more effective than standard antibiotics alone for complete healing. We have very low confidence in this finding because of the low number of participants and high risk of bias. There is also no evidence of a different treatment failure rate between PACK‐CXL with standard antibiotics versus standard antibiotics alone. We have low confidence in this finding because of the low number of participants and high risk of bias. One trial involving 32 participants reported no adverse events from PACK‐CXL at 14 days.

How up‐to‐date is this review? The review authors searched for studies that had been published up to 8 July 2019.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. PACK‐CXL with standard therapy compared with standard therapy alone for bacterial keratitis.

| PACK‐CXL with standard therapy compared with standard therapy alone for bacterial keratitis | ||||

|

Patient or population: participants of any age with confirmed cases of bacterial keratitis Settings: outpatient or inpatient Intervention: PACK‐CXL with standard therapy Comparison: standard therapy alone | ||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

|

Proportion of participants with re‐epithelialization and complete healing with or without scar formation at 4 to 8 weeks Assessed by slit‐lamp biomicroscopy |

(RR 1.53, 95% CI 0.88 to 2.66) | 15 (1 quasi‐RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | Data were reported at 8 weeks. |

|

Proportion of participants with BCVA of 20/100 or better at 4 to 8 weeks Assessed using a logMAR chart |

Not estimable | 12 (1 quasi‐RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | Data were reported at 8 weeks. RR is not available because there were no participants with a BCVA of 20/100 or better at 8 weeks. |

|

Mean change from baseline in BCVA at 4 to 8 weeks Assessed using a logMAR chart |

None | 0 | None | No data were reported. |

|

Proportion of participants with a reduction in corneal infiltrate at 4 to 8 weeks Assessed by outcome assessors |

None | 0 | None | No data were reported. |

|

Proportion of participants with reduction in intraocular inflammation at 4 to 8 weeks Assessed by corneal keratic precipitates, anterior chamber cellular reaction, or other appropriate measure |

None | 0 | None | No data were reported. |

|

Proportion of participants with treatment failure at 4 to 8 weeks Assessed by outcome assessors |

(RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.05 to 4.98) | 32 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | Data were reported at 14 days. |

|

Proportion of participants with adverse events at 4 to 8 weeks Assessed by outcome assessors |

Not estimable | 32 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | Data were reported at 14 days. RR is not available because there were no participants with adverse events at 14 days. |

| BCVA: best‐corrected visual acuity; CI: confidence interval; logMAR: logarithm of the minimal angle of resolution; PACK‐CXL: photoactivated chromophore for collagen cross‐linking; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: risk ratio | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||

1Downgraded for imprecision (‐1) due to low sample size. 2Downgraded for risk of bias (‐1) as the study was at high risk of selection bias. The high risk of selection bias reflects the overall review, since masking of participants was not possible for the surgical arm. 3Downgraded for risk of bias (‐1) as the review is at high risk of performance bias.

Background

Description of the condition

Infectious keratitis is an infection of the cornea that can be caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi, protozoa, or parasites (Bourcier 2003). It may be associated with ocular surgery, trauma, contact lens wear, or conditions that cause deficiency or loss of corneal sensation, or suppression of the immune system, such as diabetes, chronic use of topical steroids, or immunomodulatory therapies (Green 2008). The cornea is the clear, curved surface that covers the front of the eye. It is composed of five layers; from outermost, they are the epithelium, Bowman's membrane, the stroma, Descemet’s membrane, and the endothelium. Infectious keratitis first affects the outermost epithelium and can progress to damage all five layers and perforate the cornea. Untreated infectious keratitis can lead to permanent visual impairment.

Clinically, patients often present with a rapid onset of pain accompanied by conjunctival injection (red eye), photophobia (light sensitivity), and decreased vision. A corneal ulcer is an epithelial defect with surrounding and underlying inflammation caused by an influx of white blood cells. Generally, this results in necrosis of the surrounding tissue. For the purpose of this systematic review, the terms 'infectious keratitis' and 'corneal ulcer' are used interchangeably. Bacterial corneal ulcers display a sharp epithelial demarcation with underlying dense, suppurative stromal inflammation and edema (AAO 2013). Corneal ulcers are typically treated with topical antimicrobials/antibiotics; however, the widespread use of topical antibiotics may increase the incidence of multidrug‐resistant bacteria (Neu 1992). The high cost of developing new antimicrobial drugs and the rapid emergence of drug resistance make the development of alternative treatment approaches desirable (Bertino 2009; Wollensak 2006).

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the overall burden and epidemiology of keratitis in the United States is estimated to include 930,000 doctor office and outpatient clinic visits and 58,000 emergency department visits annually; 76.5% of keratitis visits resulted in antimicrobial prescriptions with an overall cost of about USD 175 million in direct healthcare expenditures, including USD 58 million for Medicare patients and USD 12 million for Medicaid patients, each year (Collier 2014). Outpatient clinic visits resulted in over 250,000 hours of clinician time annually. The disease burden of keratitis in low‐income countries is not well established, but is speculated to be high enough to warrant neglected tropical disease classification (Ung 2019).

Description of the intervention

Photoactivated chromophore for collagen cross‐linking (PACK‐CXL) of the cornea uses ultraviolet (UV)‐A rays in combination with riboflavin (vitamin B2, a photosensitizer) to increase the biomechanical strength of the cornea and halt exacerbation of ectatic conditions of the cornea (Wollensak 2006). The resulting reaction involves reactive oxygen species and leads to stiffening/stabilization of the corneal stroma via the formation of covalent bonds (cross‐links) between the corneal stromal fibers (Wollensak 2003). Riboflavin has previously been shown to be activated by UV light to inactivate pathogens by damaging their ribonucleic acid (RNA) and DNA by oxidation (Goodrich 2000; Tsugita 1965).

How the intervention might work

In a number of research studies PACK‐CXL has been shown to improve healing in bacterial keratitis and block the progression of corneal melting (enzymatic degradation by bacteria) (Iseli 2008; Makdoumi 2010; Makdoumi 2012; Morén 2010). When activated by UV light, riboflavin induces a change in collagen properties, and has a hardening and strengthening effect on corneal stroma. As a result, a compromised cornea treated with activated riboflavin can become more resistant to corneal melting (Schilde 2008; Spoerl 2004). However, an intact cornea is protective in that it allows less than 10% of UV light to penetrate the eye. In individuals with corneal ulcers, there is greater penetration of UV light, which could cause endothelial cell loss, consequently compromising the integrity of the cornea and corneal function and potentially resulting in decreased vision.

Why it is important to do this review

Observations have shown that corneal PACK‐CXL could be a novel treatment for infectious keratitis. PACK‐CXL has been shown to be effective in halting corneal melting, but the absence of control groups in past studies and previous reviews has meant that it has not been possible to confirm whether it is less, as, or more effective than antimicrobial treatments. Two systematic reviews of PACK‐CXL have been published, which together included two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (Alio 2013; Papaioannou 2016). Since these systematic reviews were published, however, other RCTs of PACK‐CXL have been conducted. It is imperative to review and re‐evaluate these trials in order to provide up‐to‐date information to use in evidence‐based recommendations.

Objectives

To determine the comparative effectiveness and safety of PACK‐CXL with standard therapy versus standard therapy alone for the treatment of bacterial keratitis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included RCTs or quasi‐RCTs that evaluated PACK‐CXL for infectious keratitis. We considered quasi‐RCTs as we anticipated that few RCTs would be available for inclusion.

Types of participants

We included studies that enrolled participants who had a diagnosis of bacterial keratitis. Where possible, we documented studies that enrolled participants with polymicrobial etiology (mixed infections) and cases involving bacterial, viral, fungal, protozoal, or parasitic infiltration, as well as cases with complications such as corneal perforations that warranted surgical intervention. However, for the purposes of this review, we focused on microbiologically proven cases of bacterial keratitis. We excluded studies in which keratitis was not clearly diagnosed as having an infectious etiology.

Types of interventions

We included studies comparing PACK‐CXL with standard therapy for the management of bacterial keratitis. Standard therapy typically includes topical antibiotic treatments. Studies that examined PACK‐CXL in combination with antimicrobial/antibiotic treatment versus standard therapy alone were eligible.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The proportion of participants with re‐epithelization and complete healing with or without scar formation at four to eight weeks. Complete healing was defined as: absence of infiltrate, epithelial healing, and no sign of inflammation or epithelial defect.

Secondary outcomes

Proportion of participants with best‐corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 20/100 or better at four to eight weeks based on measurements made on a logMAR chart. We planned to analyze BCVA data from measurements made using any type of correction of refractive error (e.g. spectacles, rigid gas‐permeable contact lens). For participants whose premorbid BCVA was worse than 20/100, we planned to consider those who regained their premorbid BCVA.

Mean change from baseline in BCVA at four to eight weeks, as measured on a logMAR chart.

Proportion of participants with a reduction in corneal infiltrate, as defined by study investigators, at four to eight weeks.

Proportion of participants with reduction in intraocular inflammation including, but not limited to, corneal keratic precipitates or anterior chamber cellular reaction, at four to eight weeks.

Proportion of participants with treatment failure, including, but not limited to, persistence or worsening of existing infectious keratitis, anterior chamber cellular reaction, corneal infiltrate, or epithelial defect, at four to eight weeks.

In the event that a trial reported an outcome for more than one time point within the range of four to eight weeks (e.g. at four weeks' and at six weeks' follow‐up), we used the longest time point for analysis. When the follow‐up time was shorter than four weeks, we used the time point at the longest follow‐up.

Adverse effects

We documented and compared the proportion of participants with adverse events at four to eight weeks in each group. Specific adverse events of interest included:

increased infiltrate size;

increased thinning or melting of the cornea, or need for corneal transplant;

development or worsening of corneal edema;

endophthalmitis; and

recurrence of corneal ulcer.

We summarized and reported other adverse effects related to PACK‐CXL therapy reported in all included studies; however, it is challenging to separate adverse outcomes of PACK‐CXL from worsening infectious keratitis.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Eyes and Vision Information Specialist searched the following electronic databases for RCTs and controlled clinical trials. There were no restrictions on language or year of publication. The electronic databases were last searched on 8 July 2019.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2019, Issue 7) (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Trials Register) in the Cochrane Library (searched 8 July 2019) (Appendix 1).

MEDLINE Ovid (January 1946 to 8 July 2019) (Appendix 2).

Embase.com (January 1947 to 8 July 2019) (Appendix 3).

PubMed (1948 to 8 July 2019) (Appendix 4).

Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information database (LILACS) (January 1982 to 8 July 2019) (Appendix 5).

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; searched 8 July 2019) (Appendix 6).

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp; searched 8 July 2019) (Appendix 7).

Searching other resources

We did not handsearch any journals or conference proceedings for this review.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (SD and RB) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts obtained from the literature searches and classified each record according to inclusion criteria eligibility as 'yes, relevant,' 'maybe,' or 'no, not relevant.' We used the web application Covidence to manage the screening process (Covidence). We obtained the full‐text reports of records classified as 'yes' or 'maybe' relevant. Two review authors evaluated these full‐text reports and categorized them as 'include,' 'awaiting assessment,' or 'exclude.' For future studies that are categorized as awaiting assessment, we plan to contact the primary investigators to obtain more information and clarification. All disagreements regarding the inclusion of a trial were resolved through discussion at each stage of the screening process.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (RB and GH) independently recorded data from study reports related to study methods, participants, interventions, and outcomes. Any disagreements or inconsistencies were resolved through discussion. We contacted the corresponding author of the study for information on missing data or to obtain clarification about unclear data. For all but one study, we did not receive responses after two weeks, therefore we used the data as reported in those study reports.

We used data extraction forms developed by Cochrane Eyes and Vision, and administered by Covidence (Covidence), to record data for individual studies. One review author entered data into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) (Review Manager 2014), and a second review author verified the data entry.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently examined each included study for risk of bias according to the methods described in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2017). We examined the studies for the following types of bias: (a) random sequence generation and allocation concealment before randomization (selection bias); (b) masking of study personnel (performance bias); (c) masking of outcome assessors (detection bias); (d) completeness of outcome data/follow‐up and intention‐to‐treat analysis (attrition bias); and (e) selective outcome reporting (reporting bias). Since masking of participants is uncommon, and often impossible, in surgical studies, we considered this a measure of risk of bias for the overall review rather than for individual studies.

Measures of treatment effect

We evaluated the data according to the guidelines in Chapter 9 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2017). We planned to calculate mean differences with 95% confidence intervals for continuous outcomes, such as mean change in BCVA from baseline, and risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals for dichotomous outcomes, including the proportion of participants with re‐epithelialization and complete healing and the proportion of participants with BCVA of 20/100 or better.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the individual in all included studies (one study eye per participant).

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the corresponding author of the study for information on missing data or to obtain clarification about unclear data; however, for all but one study, we did not receive a response. We did not impute data for the purposes of this review.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed methodological and clinical heterogeneity by examining the study methods, population, interventions, and outcomes among studies. We did not assess statistical heterogeneity since only one study provided outcome data in four to eight weeks.

When future RCTs become eligible for inclusion, we will assess statistical heterogeneity using an I² value of more than 50% as indicative of substantial statistical heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed selective outcome reporting for each study by comparing the outcomes specified in a protocol, research plan, or clinical trial registry with the reported results. In future updates of this review, if outcome data from 10 or more studies are included in a meta‐analysis we will assess the symmetry of the funnel plot as a method of examining small‐study effects (Deeks 2017). We assessed risk of selective outcome reporting as part of our assessment of risk of bias in the included studies.

Data synthesis

We did not combine study results since none of the prespecified review outcomes were reported by more than one study. We provided a description and summarized the findings of each study.

In future review updates, meta‐analysis may be possible if data for one or more outcomes are reported in additional included studies. If there is no clinical or methodological heterogeneity and no substantial statistical heterogeneity, we will combine the data for each outcome in a meta‐analysis using a random‐effects model; if the number of included studies is less than three, we will use a fixed‐effect model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

In future updates of this review, we will conduct a subgroup analysis to assess whether type of infection (bacterial, viral, fungal, protozoal, or parasitic) has an effect on response to PACK‐CXL.

Sensitivity analysis

In future review updates, when sufficient data are available, we will perform sensitivity analyses to determine the consistency of effect estimates when excluding studies at high risk of bias, unpublished trials, and studies funded by industry.

Summary of findings

We examined the overall certainty of evidence via the GRADE approach using the domains of risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness, and publication bias (Schünemann 2011). We presented our findings in a 'Summary of findings' table for the following outcomes.

The proportion of participants with re‐epithelization and complete healing with or without scar formation at four to eight weeks.

The proportion of participants with BCVA of 20/100 or better at four to eight weeks. For participants whose premorbid BCVA was worse than 20/100, we considered those who regained their premorbid BCVA.

The proportion of participants with a reduction in corneal infiltrate at four to eight weeks.

The proportion of participants with a reduction in intraocular inflammation at four to eight weeks.

The proportion of participants with treatment failure at four to eight weeks.

The proportion of participants with adverse events at four to eight weeks.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

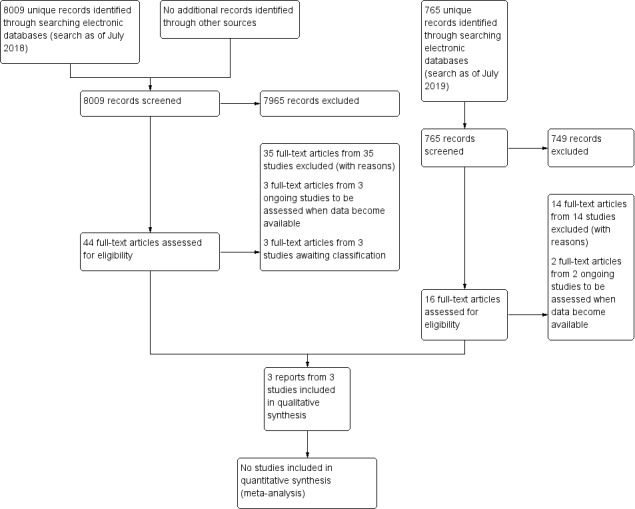

The electronic search yielded 8019 records (Figure 1). After removing 10 duplicates, we screened the remaining 8009 records and excluded a further 7965 records based on information in the title and abstract. We obtained the full‐text reports of 44 records for further investigation. At full‐text screening, we included three reports of three studies (see Characteristics of included studies), three ongoing studies that potentially met our inclusion criteria (see Characteristics of ongoing studies), and three studies awaiting classification (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification). We identified and excluded 35 reports of 35 studies (see Characteristics of excluded studies).

1.

Study flow diagram.

We conducted a top‐up search in July 2019 that yielded 766 records (Figure 1). We removed one duplicate and performed title and abstract screening of the remaining 765 records. We excluded 749 records, and assessed the full texts of 16 records. We excluded 14 full‐text records (see Characteristics of excluded studies) and identified two ongoing studies that will be assessed when data become available (see Characteristics of ongoing studies).

We identified a total of three included studies, five ongoing studies, and three studies awaiting classification.

Included studies

For further details on included studies, see Characteristics of included studies.

Type of studies

We included two RCTs, Bamdad 2015; Kasetsuwan 2016, and one quasi‐RCT, Said 2014. Two studies were conducted in the Middle East: Said 2014 (Egypt) and Bamdad 2015 (Iran), while the third study was conducted in Thailand (Kasetsuwan 2016). All studies were single‐center. Study participants were recruited between 2010 to 2014. One study reported participant‐level outcomes data (Said 2014), whereas the other two studies reported summary outcomes data (Bamdad 2015; Kasetsuwan 2016).

Type of participants

The three studies randomized a total of 82 participants (82 eyes, range per study: 21 to 32), 59 of whom were diagnosed with bacterial keratitis. The studies were of comparable sizes, although the number of participants with bacterial keratitis varied from 12 to 32 per study. One study included only participants with bacterial keratitis (Bamdad 2015), while the remaining two studies included participants who were heterogenous with regard to causative organism (Kasetsuwan 2016; Said 2014).

Demographic and baseline characteristics of participants with bacterial keratitis were inconsistently reported in the three studies. While Bamdad 2015 reported all characteristics, Said 2014 reported only baseline characteristics of participants with bacterial keratitis, and Kasetsuwan 2016 did not report any characteristics. Communication with study investigators yielded no additional information.

The average age of randomized participants was comparable across the three studies despite different inclusion criteria: Kasetsuwan 2016 included children older than six years of age, and Said 2014 included adults 18 years of age or older. Randomized participants were on average middle‐aged (mean age of 43 years), which is consistent with findings from retrospective analyses (Bourcier 2003; Mun 2019). Participants also had variable baseline levels of corneal ulcer severity, which was determined based on size and infiltration: Kasetsuwan 2016 included participants with moderate (defined as being 2 to 6 mm in size and involving the superficial two‐thirds of the cornea) to severe ulcers (defined as being over 6 mm in size and involving the posterior one‐third of the cornea, or presence of hypopyon), and Bamdad 2015 only included participants with moderate ulcers (defined as being 2 to 6 mm in size and involving the superficial two‐thirds of the cornea). Said 2014 did not use standardized ulcer grading in their inclusion criteria. All participants in Said 2014 had advanced keratitis due to presence of corneal melting and received treatment for infectious keratitis prior to enrollment.

Type of interventions

The three studies compared photoactivated chromophore for collagen cross‐linking (PACK‐CXL) with standard therapy versus standard therapy alone for the treatment of infectious keratitis.

PACK‐CXL with standard therapy versus standard therapy alone

Sixty participants were assigned to one of two intervention arms: PACK‐CXL with standard therapy or standard therapy alone. Participants who were assigned to the PACK‐CXL arm received riboflavin (MedioCross 0.1% riboflavin/20% dextran solution; Peschke Meditrade) before and during 30‐minute UVA illumination (365 nm with 3.0 mW/cm²) with a UV‐X lamp (Peschke Meditrade). Riboflavin administration took place for an initial 30 minutes and then another 30 minutes while irradiating with UVA. The respective frequency of riboflavin administration varied across studies: every 2 minutes and then every 5 minutes (Kasetsuwan 2016); every 2 minutes and then every 2 minutes (Said 2014); and every 3 minutes and then every 5 minutes (Bamdad 2015). After PACK‐CXL, participants received standard antibiotic therapy.

Standard therapy for cases of bacterial keratitis consisted of antibiotic therapy; studies varied in the type and number of antibiotics given, but all antibiotics were given hourly. Kasetsuwan 2016 used fortified cefazolin (50 mg/mL) and fortified amikacin (20 mg/mL); Said 2014 used vancomycin eye drops (50 mg/mL), fortified ceftazidime eye drops (50 mg/mL hourly), and itraconazole (100 mg orally twice daily); and Bamdad 2015 used fortified cefazolin (50 mg/mL hourly), gentamicin (15 mg/mL hourly), and systemic doxycycline (every 12 hours). These antibiotics are typical of usual practice (AAO 2019). Loading doses, which are a high initial dose to rapidly achieve desired levels in a patient, were used in Bamdad 2015 (fortified cefazolin and gentamicin every 5 minutes for 30 minutes).

Type of outcomes

Follow‐up

Bamdad 2015 conducted follow‐up at 14 days, and Kasetsuwan 2016 conducted follow‐up at 30 days. Said 2014 conducted follow‐up examinations until healing as defined by study authors; the longest time until healing was 120 days.

Morphology

One study reported information with which we could assess our primary outcome (proportion of participants with re‐epithelialization and complete healing with or without scar formation) (Said 2014). Although both Bamdad 2015 and Said 2014 reported participants' time to complete healing, only Said 2014 reported sufficient data to determine the proportion of participants with complete healing. Bamdad 2015 and Kasetsuwan 2016 reported mean area of epithelial defects at day 14 and median area of epithelial defects at day 30, respectively.

We were also interested in the proportion of participants with a reduction in corneal infiltrate. All included studies measured the final corneal infiltration using slit‐lamp biomicroscopy, but reported infiltrate morphology in various ways.

Bamdad 2015 graded the ulcer at day 14 (grading considered the severity of anterior segment infiltrates). Kasetsuwan 2016 reported the median infiltrate area at day 30; however, the study authors did not report sufficient participant‐level data to determine the proportion of participants with a reduction in corneal infiltrate. Said 2014 considered clearing of stromal infiltrate as part of their definition of complete healing.

No studies reported sufficient information to assess the proportion of participants with reduction in intraocular inflammation (e.g. hypopyon). The authors of Bamdad 2015 and Said 2014 reported the number of participants who reached complete healing, which was defined as the disappearance of hypopyon, among other requirements (e.g. no anterior chamber activity, re‐epithelialization). However, data were insufficient to assess only the proportion of participants with disappearance of hypopyon.

Bamdad 2015 reported the proportion with treatment failure at day 14.

Visual acuity

Two studies reported visual acuity outcomes using measurements made on a logMAR chart (Kasetsuwan 2016; Said 2014). The two studies reported baseline and final visual acuity: Said 2014 reported BCVA, and Kasetsuwan 2016 reported BPVA (best pinhole‐corrected visual acuity). Measuring BPVA eliminates the effect of ocular opacity that corneal ulcers would have on visual acuity, potentially equalizing the visual acuity results of PACK‐CXL and control groups. Said 2014 reported individual‐level baseline and final BCVA measurements at time of healing, which ranged from 14 to 120 days, from which we calculated the proportion of participants with BCVA of 20/100 or better and mean change from baseline in BCVA. We were unable to extract visual acuity data on bacterial keratitis cases in Kasetsuwan 2016 because only summary‐level visual acuity data (i.e. proportion with improved BPVA, mean BPVA) were reported.

Bamdad 2015 reported that an examiner assessed baseline visual acuity, but the authors did not report the measurements nor specify whether visual acuity measured as BCVA or BPVA. Moreover, authors did not measure final visual acuity.

Adverse events

Bamdad 2015 reported adverse events at day 14. Although Kasetsuwan 2016 and Said 2014 reported adverse events, we were not able to determine whether participants with bacterial keratitis were affected. Kasetsuwan 2016 reported two cases of uncontrolled infection in the PACK‐CXL with standard therapy group at day 30, and three cases of uncontrolled infection and one case of endophthalmitis in the standard therapy‐alone group. Said 2014 reported no complications in the PACK‐CXL with standard therapy group at time of healing (range: 14 to 120 days), whereas there were three cases of corneal perforation and one case of recurrent infection in the standard therapy‐alone group.

Ongoing studies

We identified five ongoing studies (n = 1136). All studies are described as RCTs. They are geographically diverse, taking place or proposing to take place in Australia, India, the United States, and Switzerland. One study compares PACK‐CXL with standard therapy versus placebo surgery with standard therapy (CTRI/2019/02/017601). Four studies compare PACK‐CXL with standard therapy versus standard therapy (ACTRN12611000189921; CTRI/2019/01/017136; NCT02570321; NCT02717871).

Studies awaiting classification

We identified three RCTs (n = 380) awaiting classification. One study compares PACK‐CXL with standard therapy versus placebo surgery with standard therapy (NCT02865876), and two studies compare PACK‐CXL with standard therapy versus standard therapy (NCT02088970; PACTR201701001843366). NCT02865876 was discontinued due to difficulty recruiting participants. We contacted the authors of NCT02865876 and NCT02865876 with a data request; however, we did not receive a response. PACTR201701001843366 (n = 78) was published recently and will be included in a future update of this review.

Excluded studies

We excluded 20 studies at full‐text assessment because they were not RCTs or quasi‐RCTs. We additionally excluded eight studies with ineligible patient population and seven studies with ineligible interventions. There were a total of 35 excluded studies.

For further details on excluded studies, see Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

We summarized the risk of bias in all included studies in Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

All studies reported methods of randomization: two RCTs used simple randomization (Bamdad 2015; Kasetsuwan 2016), and one quasi‐RCT used alternate allocation (Said 2014). Randomization in Said 2014 was inadequately generated, and may have introduced selection bias.

Allocation concealment

One study reported allocation concealment using sealed envelopes (Kasetsuwan 2016). The quasi‐RCT used alternate allocation and was therefore at high risk of bias (Said 2014). One study did not report method of allocation concealment (Bamdad 2015). Overall, allocation concealment was poorly conducted or reported.

Blinding

Two studies reported masking outcome assessors (Bamdad 2015; Kasetsuwan 2016). However, masking of outcome assessors failed in Bamdad 2015 due to participants informing the assessor of their treatment group.

As reported in the review protocol, the nature of surgical studies means that masking of participants is impossible. We therefore considered the overall review as at high risk of bias for this domain (see Table 1).

Incomplete outcome data

None of the studies reported missing data from attrition. We considered studies to have complete outcome data.

Selective reporting

Two studies reported prespecified outcomes in the protocols (Bamdad 2015; Kasetsuwan 2016). Insufficient information was available to assess reporting bias for Said 2014.

Other potential sources of bias

A study author in Said 2014 co‐invented an ultraviolet light source; an ultraviolet light source is used for PACK‐CXL, but it is unclear if the invention was used in the study. This was the only reported conflict of interest in the included studies.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

See Table 1.

Comparison 1: Collagen cross‐linking with standard therapy versus standard therapy alone

We did not conduct a meta‐analysis for any outcome since none of the prespecified review outcomes were reported by more than one study.

Proportion of participants with re‐epithelialization and complete healing with or without scar formation at 8 weeks (1 study; 15 participants)

In Said 2014, participants were followed until complete healing was achieved. We analyzed outcome data at our time point of interest (longest time point between four and eight weeks) using the participant‐level data provided. There were seven participants in the PACK‐CXL with standard therapy arm and eight participants in the standard therapy‐alone arm. Participants in the PACK‐CXL group fared slightly better than those in the only standard therapy‐alone arm: at 8 weeks, 7/7 participants in the PACK‐CXL with standard therapy arm achieved complete healing, compared to 5/8 participants in the standard therapy‐alone arm (risk ratio (RR) 1.53, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.88 to 2.66).

We judged the evidence for complete healing to be of very low certainty due to the small sample size and high risk of selection and performance bias. The high risk of selection bias reflects the overall review, since masking of participants was not possible for the surgical arm.

Proportion of participants with BCVA of 20/100 or better at 8 weeks (1 study; 12 participants)

In Said 2014, no participants in either arm achieved a BCVA of 20/100 or better. Only 12 participants were included because BCVA was assessed at the time of complete healing, which occurred after 8 weeks for 3 participants.

We judged the evidence for visual acuity to be of very low certainty due to the small sample size and high risk of selection and performance bias. The high risk of selection bias reflects the overall review, since masking of participants was not possible for the surgical arm.

Mean change from baseline in BCVA

Not reported.

Proportion of participants with a reduction in corneal infiltrate

Not reported.

Proportion of participants with reduction in intraocular inflammation

Not reported.

Proportion of participants with treatment failure at day 14 (1 study, 32 participants)

Bamdad 2015 reported treatment failure in 1/16 participants in the PACK‐CXL with standard therapy arm, compared to 2/16 participants in the standard therapy‐alone arm (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.05 to 4.98). Participants with treatment failure were treated with amniotic membrane transplantation; if this failed, a conjunctival flap was performed.

We judged the evidence for treatment failure to be of low certainty due to the small sample size and high risk of selection bias. The high risk of selection bias reflects the overall review, since masking of participants was not possible for the surgical arm.

Proportion of participants with adverse events at day 14 (1 study, 32 participants)

Bamdad 2015 reported no adverse events in either arm.

We judged the evidence for adverse events to be of low certainty due to the small sample size and high risk of selection bias. The high risk of selection bias reflects the overall review, since masking of participants was not possible for the surgical arm.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This systematic review included three studies that compared PACK‐CXL with standard antibiotic therapy to standard antibiotic therapy alone for the treatment of bacterial keratitis (59 participants). Two studies were RCTs, and one study used a quasi‐randomization method based on alternate allocation. The primary outcome for our review was proportion of participants with complete healing. Secondary outcomes included visual acuity and morphology measures, as well as adverse events and treatment failure. All three included studies had comparable intervention groups and protocols for PACK‐CXL with standard therapy.

The included studies were highly variable with regard to outcome reporting and follow‐up times. The clinical heterogeneity in reported outcomes made it difficult to compare data across RCTs. Moreover, there was a wide range of follow‐up times: 14 days (prespecified) to 120 days (time until healing). The methodological rigor of the studies varied. Although there were no missing data reported in the included studies, one study was quasi‐randomized, thereby introducing selection bias. There was high risk of bias overall due to performance bias, since it is impossible to mask participants to surgical interventions.

The most significant limitation we faced was that studies provided insufficient information to assess cases of bacterial keratitis. Two of the three included studies included keratitis of any etiology, but did not report outcomes based on etiology completely or at all. In addition, there were low numbers of participants with bacterial keratitis enrolled in the included studies (range 12 to 32); while one study conducted a sample size calculation, the calculation was designed to detect significance in participants with keratitis of any etiology.

It is very uncertain whether PACK‐CXL with standard antibiotic therapy is safer and more effective than standard antibiotic therapy alone for re‐epithelialization and complete healing. We have very low confidence in this evidence due to the small sample size and high risk of selection and performance bias.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The overall certainty of the evidence is very low. We identified three small studies for inclusion in the review, and only one study reported sufficient information to assess outcomes for cases of bacterial keratitis. We judged all three studies as at high or unclear risk of bias for most domains.

Quality of the evidence

The evidence in this review is very limited because we were unable to assess the data on cases of bacterial keratitis for two of the three included studies. Moreover, the number of bacterial keratitis cases per study was very low (range: 12 to 32). Given these small sample sizes, we are not confident in the available evidence.

Overall, this review was at high risk of performance bias because the intervention arm involved a surgical procedure which thus made masking participants and personnel impossible. Other 'Risk of bias' domains were generally low or unclear (see Characteristics of included studies).

Potential biases in the review process

No changes were made to the review protocol published in 2018. Two review authors independently completed all steps in the Methods section to minimize errors and conferred upon disagreement.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Papaioannou 2016 analyzed two of the three studies included in our systematic review, assessing a total of 25 studies (13 case series, 10 case reports). The review authors found that PACK‐CXL was most effective in cases of bacterial keratitis (87.2% healed, total of 167 eyes), but the certainty of evidence was low due to the number of non‐randomized studies that were included. Another systematic review supported PACK‐CXL for infectious keratitis (Alio 2013); however, that review did not identify any RCTs for inclusion.

We are in agreement with published systematic reviews that recommend further rigorous examination of the effectiveness of PACK‐CXL in individuals with infectious keratitis, and more specifically infectious keratitis by etiology.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Despite the success of corneal collagen cross‐linking for other eyes and vision conditions (e.g. keratoconus), there is insufficient evidence to establish whether photoactivated chromophore for collagen cross‐linking (PACK‐CXL) in combination with standard antibiotic therapy is safe and effective for bacterial keratitis.

Implications for research.

Given the preponderance of non‐randomized studies exploring PACK‐CXL as a treatment for bacterial keratitis, the five ongoing RCTs may provide better answers in the next update of this review. It is important that future RCTs conduct subgroup analyses based on etiology, given the differences that exist between bacterial keratitis and other types, such as fungal (Wong 1997). Researchers would benefit from developing a core outcome set for infectious keratitis, with a focus on which time points and patient‐centered outcomes should be studied. Further review updates will be necessary as more studies become eligible for inclusion.

History

Protocol first published: Issue 5, 2018 Review first published: Issue 6, 2020

Acknowledgements

Lori Rosman, Information Specialist for Cochrane Eyes and Vision, created and executed the electronic search strategies. We thank Tianjing Li and Henry Jampel for providing comments on the review. We also thank the following peer reviewers for their comments: Lindsay Sicks, OD, FAAO (Illinois College of Optometry) and Vishal Jhanji, MD (University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine).

We are grateful to Dr Robert A Copeland Jr, who passed in April 2016. Dr Copeland conceived, designed, and drafted the first version of the protocol. The authors have made edits to the protocol beyond his contribution, although the main components (population, interventions, comparisons, and outcomes) are consistent with his initial draft.

This review was managed by CEV@US and was signed off for publication by Tianjing Li and Richard Wormald.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Keratitis] explode all trees #2 (cornea* AND (melt* or infection* or microbial or ulcer* or inflammat*)) #3 (Keratiti* or Keratoconjunctiviti* or Kerato conjunctiviti*) #4 #1 or #2 or #3 #5 MeSH descriptor: [Cross‐Linking Reagents] explode all trees #6 (cross link* or crosslink* or CXL) #7 MeSH descriptor: [Collagen] explode all trees and with qualifier(s): [Radiation effects ‐ RE] #8 Collagen #9 MeSH descriptor: [Anti‐Infective Agents] explode all trees #10 ("Anti Infective" or Antiinfective or Antimicrobial or "Anti Microbial" or Microbicid*) #11 MeSH descriptor: [Riboflavin] explode all trees #12 (Riboflavin* or "Vitamin G" or "Vitamin B2" or "Vitamin B 2" or Beflavin or beflavine or flavaxin or hyrye or lactoflavin or lactoflavine or ovoflavin or pabriflan or riboflavine or ribovel or "83‐88‐5") #13 MeSH descriptor: [Ultraviolet Therapy] explode all trees #14 MeSH descriptor: [Ultraviolet Rays] explode all trees #15 (Ultraviolet* or "Ultra Violet" or UV Ray* or UV light* or "UV‐A" or UVA or Actinotherap* or Actinic Ray*) #16 MeSH descriptor: [Photosensitizing Agents] explode all trees #17 Photosensitiz* #18 MeSH descriptor: [Photochemotherapy] explode all trees #19 (Photochemotherap* or Photodynamic*) #20 MeSH descriptor: [Cornea] explode all trees and with qualifier(s): [Drug effects ‐ DE] #21 MeSH descriptor: [Cornea] explode all trees and with qualifier(s): [Radiation effects ‐ RE] #22 {or #5‐#21} #23 #4 and #22

Appendix 2. MEDLINE Ovid search strategy

1. Randomized Controlled Trial.pt. 2. Controlled Clinical Trial.pt. 3. (randomized or randomised).ab,ti. 4. placebo.ab,ti. 5. drug therapy.fs. 6. randomly.ab,ti. 7. trial.ab,ti. 8. groups.ab,ti. 9. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 10. exp animals/ not humans.sh. 11. 9 not 10 12. exp Keratitis/ 13. (cornea* AND (melt* or infection* or microbial or ulcer* or inflammat*)).tw. 14. (Keratiti* or Keratoconjunctiviti* or Kerato conjunctiviti*).tw. 15. 12 or 13 or 14 16. exp Cross‐Linking Reagents/ 17. (cross link* or crosslink* or CXL).tw. 18. exp Collagen/re [Radiation Effects] 19. Collagen.tw. 20. exp Anti‐Infective Agents/ 21. ("Anti Infective" or Antiinfective or Antimicrobial or "Anti Microbial" or Microbicid*).tw. 22. exp Riboflavin/ 23. (Riboflavin* or "Vitamin G" or "Vitamin B2" or "Vitamin B 2" or Beflavin or beflavine or flavaxin or hyrye or lactoflavin or lactoflavine or ovoflavin or pabriflan or riboflavine or ribovel or "83‐88‐5").tw. 24. exp Ultraviolet Therapy/ 25. exp Ultraviolet Rays/ 26. (Ultraviolet* or Ultra‐Violet or UV Ray* or UV light* or "UV‐A" or UVA or Actinotherap* or Actinic Ray*).tw. 27. exp Photosensitizing Agents/ 28. Photosensitiz*.tw. 29. exp Photochemotherapy/ 30. (Photochemotherap* or Photodynamic*).tw. 31. exp Cornea/de, re [Drug Effects, Radiation Effects] 32. or/16‐31 33. 11 and 15 and 32

The search filter for trials at the beginning of the MEDLINE strategy is from the published paper by Glanville 2006.

Appendix 3. Embase.com search strategy

#1 'randomized controlled trial'/exp #2 'randomization'/exp #3 'double blind procedure'/exp #4 'single blind procedure'/exp #5 random*:ab,ti #6 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 #7 'animal'/exp OR 'animal experiment'/exp #8 'human'/exp #9 #7 AND #8 #10 #7 NOT #9 #11 #6 NOT #10 #12 'clinical trial'/exp #13 (clin* NEAR/3 trial*):ab,ti #14 ((singl* OR doubl* OR trebl* OR tripl*) NEAR/3 (blind* OR mask*)):ab,ti #15 'placebo'/exp #16 placebo*:ab,ti #17 random*:ab,ti #18 'experimental design'/exp #19 'crossover procedure'/exp #20 'control group'/exp #21 'latin square design'/exp #22 #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 #23 #22 NOT #10 #24 #23 NOT #11 #25 'comparative study'/exp #26 'evaluation'/exp #27 'prospective study'/exp #28 control*:ab,ti OR prospectiv*:ab,ti OR volunteer*:ab,ti #29 #25 OR #26 OR #27 OR #28 #30 #29 NOT #10 #31 #30 NOT (#11 OR #23) #32 #11 OR #24 OR #31 #33 'keratitis'/exp #34 (cornea* AND (melt* OR infection* OR microbial OR ulcer* OR inflammat*))):ab,ti #35 keratiti*:ab,ti OR keratoconjunctiviti*:ab,ti OR 'kerato conjunctiviti*':ab,ti #36 #33 OR #34 OR #35 #37 'cross linking reagent'/exp #38 'cross link*':ab,ti OR crosslink*:ab,ti OR cxl:ab,ti #39 'collagen'/exp #40 collagen:ab,ti #41 'antiinfective agent'/exp #42 'anti infective':ab,ti OR antiinfective:ab,ti OR antimicrobial:ab,ti OR 'anti microbial':ab,ti OR microbicid*:ab,ti #43 'riboflavin'/exp #44 riboflavin*:ab,ti,tn OR 'vitamin g':ab,ti,tn OR 'vitamin b2':ab,ti,tn OR 'vitamin b 2':ab,ti,tn OR beflavin:ab,ti,tn OR beflavine:ab,ti,tn OR flavaxin:ab,ti,tn OR hyrye:ab,ti,tn OR lactoflavin:ab,ti,tn OR lactoflavine:ab,ti,tn OR ovoflavin:ab,ti,tn OR pabriflan:ab,ti,tn OR riboflavine:ab,ti,tn OR ribovel:ab,ti,tn OR '83‐88‐5':ab,ti,tn #45 'ultraviolet phototherapy'/exp #46 'ultraviolet radiation'/exp #47 ultraviolet*:ab,ti OR 'ultra violet':ab,ti OR 'uv ray*':ab,ti OR 'uv light*':ab,ti OR 'uv‐a':ab,ti OR uva:ab,ti OR actinotherap*:ab,ti OR 'actinic ray*':ab,ti #48 'photosensitizing agent'/exp #49 photosensitiz*:ab,ti #50 'photochemotherapy'/exp #51 photochemotherap*:ab,ti OR photodynamic*:ab,ti #52 'cornea'/exp/dd_ae,dd_an,dd_cm,dd_it,dd_dt,dd_to #53 #37 OR #38 OR #39 OR #40 OR #41 OR #42 OR #43 OR #44 OR #45 OR #46 OR #47 OR #48 OR #49 OR #50 OR #51 OR #52 #53 #32 AND #36 AND #53

Appendix 4. PubMed search strategy

#1 ((randomized controlled trial[pt]) OR (controlled clinical trial[pt]) OR (randomised[tiab] OR randomized[tiab]) OR (placebo[tiab]) OR (drug therapy[sh]) OR (randomly[tiab]) OR (trial[tiab]) OR (groups[tiab])) NOT (animals[mh] NOT humans[mh]) #2 (cornea*[tw] AND (melt*[tw] OR infection*[tw] OR microbial[tw] OR ulcer*[tw] OR inflammat*[tw])) NOT Medline[sb] #3 (Keratiti*[tw] OR Keratoconjunctiviti*[tw] OR Kerato conjunctiviti*[tw]) NOT Medline[sb] #4 #2 OR #3 #5 (cross link*[tw] OR crosslink*[tw] OR CXL[tw]) NOT Medline[sb] #6 Collagen[tw] NOT Medline[sb] #7 ("Anti Infective"[tw] OR Antiinfective[tw] OR Antimicrobial[tw] OR "Anti Microbial"[tw] OR Microbicid*[tw]) NOT Medline[sb] #8 (Riboflavin*[tw] OR "Vitamin G"[tw] OR "Vitamin B2"[tw] OR "Vitamin B 2"[tw] OR Beflavin[tw] OR beflavine[tw] OR flavaxin[tw] OR hyrye[tw] OR lactoflavin[tw] OR lactoflavine[tw] OR ovoflavin[tw] OR pabriflan[tw] OR riboflavin[tw] OR ribovel[tw] OR "83‐88‐5"[tw]) NOT Medline[sb] #9 (Ultraviolet*[tw] OR "Ultra Violet"[tw] OR UV Ray*[tw] OR UV light*[tw] OR "UV‐A"[tw] OR UVA[tw] OR Actinotherap*[tw] OR Actinic Ray*[tw]) NOT Medline[sb] #10 Photosensitiz*[tw] NOT Medline[sb] #11 (Photochemotherap*[tw] OR Photodynamic*[tw]) NOT Medline[sb] #12 (#5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11) #13 #4 AND #12 #14 #1 AND #13

Appendix 5. LILACS search strategy

(MH:C11.204.564$ OR Keratiti$ OR Queratiti$ OR Ceratit$ OR MH:C11.187.183.394 OR Keratoconjunctiviti$ OR Queratoconjuntiviti$ OR Ceratoconjuntivit$ OR (cornea$ AND (melt$ OR infection$ OR microbial OR ulcer$ OR inflammation))) AND (MH: D27.720.470.410.210$ OR (cross link$) OR crosslink$ OR CXL OR MH:D05.750.078.280$ OR MH:D12.776.860.300.250$ OR Collagen OR D27.505.954.122$ OR "Anti Infective" OR Antiinfective OR Antimicrobial OR "Anti Microbial" OR Microbicid$ OR Antiinfecciosos OR "Anti‐Infecciosos" OR MH:D03.438.733.315.650$ OR MH:D03.494.507.650$ OR MH:D08.211.474.650$ OR MH:D23.767.405.650$ OR Riboflavin$ OR "Vitamin G" OR "Vitamin B2" OR "Vitamin B 2" OR Beflavin OR beflavine OR flavaxin OR hyrye OR lactoflavin OR lactoflavine OR ovoflavin OR pabriflan OR riboflavine OR ribovel OR "83‐88‐5" OR MH:E02.774.945$ OR MH:G01.358.500.505.650.891$ OR MH:G01.590.540.891$ OR MH:G01.750.250.650.891$ OR MH:G01.750.750.659$ OR MH:G01.750.770.578.891$ OR MH:G16.500.275.063.725.525.600$ OR MH:G16.500.750.775.525.600$ OR MH:N06.230.300.100.725.525.600$ OR MH:SP4.011.087.698.384.075.166.032$ OR MH:SP4.021.202.133.789$ OR Ultraviolet$ OR (Ultra Violet$) OR (UV Ray$) OR (UV light$) OR "UV‐A" OR UVA OR Actinotherap$ OR (Actinic Ray$) OR MH:D27.505.954.444.600$ OR MH:D27.505.954.600.710$ OR Photosensitiz$ OR Fotosensibilizante$ OR Fotossensibilizante$ OR Photochemotherap$ OR Photodynamic$ OR MH:E02.186.500$ OR MH:E02.319.685$ OR MH:E02.774.722$ OR Fotoquimioterap$ OR mh:"Cornea/DE" OR mh:"Cornea/RE")

Appendix 6. ClinicalTrials.gov search strategy

Keratitis OR Keratoconjunctivitis OR ((cornea OR corneal) AND (melt OR infection OR microbial OR ulcer OR inflammation))

Appendix 7. ICTRP search strategy

Keratitis OR Keratoconjunctivitis OR cornea AND melt OR cornea AND infection OR cornea AND microbial OR cornea AND ulcer OR cornea AND inflammation OR corneal AND melt OR corneal AND infection OR corneal AND microbial OR corneal AND ulcer OR corneal AND inflammation

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Bamdad 2015.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods |

Study design: randomized controlled trial, parallel group Study center: Khalili Hospital Country: Iran Number randomized: 32 total, 16 per group Follow‐up period: 14 days Exclusions and losses to follow‐up: none Sample size calculation: not reported |

|

| Participants |

PACK‐CXL:

Standard therapy (control):

Overall:

Group differences: none Inclusion criteria: moderate bacterial corneal ulcers, referred to Khalili Eye Hospital Exclusion criteria: any kind of corneal perforation, corneal descemetocele, collagen vascular disease or immunocompromising diseases, and those who needed any kind of emergency keratoplasty |

|

| Interventions |

PACK‐CXL: 0.1% riboflavin in dextran 500 20% drops were applied every 3 minutes for 30 minutes. Corneas were irradiated with UVA rays (365 nm) in an optical zone of 8 mm for 30 minutes with an irradiance of 3 mW/cm². During irradiation, the cornea received 0.1% riboflavin every 5 minutes. After treatment, the eyes were given a therapeutic soft contact lens (T‐lens). Standard medical treatment followed (see comparator group). Standard therapy: standard medical therapy included lubrication, fortified cefazolin (50 mg/mL) every 1 hour, fortified gentamicin (15 mg/mL) every 1 hour, and systematic doxycycline every 12 hours after loading doses of fortified cefazolin and gentamicin (every 5 minutes for 30 minutes) |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome: not reported Secondary outcome: not reported Measured outcomes:

Time points measured:

Adverse effects related to PACK‐CXL for bacterial keratitis: none Unit of analysis: participant |

|

| Notes |

Enrollment period: 2013 to 2014 Funding source: "This article has been derived from the thesis by Hossein Malekhosseini ‐ Grant No: 5685" Conflicts of interest: no conflicts of interest to disclose Trial registration: IRCT2014101919581N1 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Simple randomization with a numerical randomization table |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | As reported in the review protocol, the nature of surgical studies means that masking of participants is impossible. We therefore considered the overall review at high risk of bias in this domain. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Outcome assessors were blinded, but some participants informed the assessor of their operation; this is listed as a potential study limitation. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Outcomes are completely reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Protocol predefined outcomes. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No conflicts of interest reported. |

Kasetsuwan 2016.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods |

Study design: randomized controlled trial, parallel group Study center: Department of Ophthalmology, King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital Country: Thailand Number randomized: 30 total, 15 per group Follow‐up period: 30 days Exclusions and losses to follow‐up: none Sample size calculation: superiority design formula with power of 0.8 and a 2‐tailed significance level of.05 was used to detect 7 mm² difference in areas of stromal infiltration with standard deviation of 6; this provided a sample size of 15 participants per group |

|

| Participants |

PACK‐CXL:

Standard therapy (control):

Overall:

Group differences: baseline characteristics were comparable in both groups Inclusion criteria: evidence of corneal ulcer grade II or III (bacteria or fungal, or presumed bacterial or fungal), aged 6 years or older, patients can understand and can follow the study protocol Exclusion criteria: pregnant patients or patients with a history or evidence of herpetic keratitis, parasitic keratitis, corneal perforation, autoimmune diseases, endophthalmitis, known allergy to study medication, or corneal thickness less than 400 micrometers by ultrasound pachymetry |

|

| Interventions |

PACK‐CXL: riboflavin (0.1% riboflavin/20% dextran solution) was administered to the cornea every 2 minutes for an initial period of 30 minutes and then every 5 minutes for a further 30 minutes during UVA illumination. The UV‐X lamp was used to deliver UVA (365 nm with 3.0 mW/cm²) for 30 minutes. After the PACK‐CXL treatment, participants received standard medical treatment (see comparator group). Standard therapy: standard medical treatment: for bacterial keratitis, hourly instillation of fortified cefazolin (50 mg/mL) and fortified amikacin (20 mg/mL); for fungal keratitis: hourly topical application of emphotericin B (1.0 mg/mL) and topical natamycin (50 mg/mL) |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome: size of stromal infiltrates measured on slit‐lamp photographs 30 days after treatment Secondary outcomes:

Time points measured:

Adverse effects related to PACK‐CXL for bacterial keratitis: although the study reported adverse effects, authors did not specify the etiology of the relevant keratitis cases. Uncontrolled infection with corneal perforation was reported in 2 cases, and endophthalmitis was reported in 1 case. Unit of analysis: participant |

|

| Notes |

Enrollment period: 2013 to 2014 Funding source: no funding or grant support Conflicts of interest: no financial disclosures Notes: subgroup analysis in the bacterial and fungal keratitis samples showed no significant differences Trial registration: NCT01831206 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | After enrollment, participants were randomized to receive standard treatment with or without PACK‐CXL using simple randomization. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sealed envelopes, used to conceal the randomization, were opened after enrollment of each participant. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | As reported in the review protocol, the nature of surgical studies means that masking of participants is impossible. We therefore considered the overall review as at high risk of bias in this domain. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Outcome assessor was masked, according to protocol. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Outcomes are completely reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Outcomes were prespecified in protocol. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No financial conflicts of interest. |

Said 2014.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods |

Study design: quasi‐randomized controlled trial, parallel group Study center: Cornea Clinic of the Research Institute of Ophthalmology Country: Egypt Number randomized: 40 total, 21 in PACK‐CXL group, 19 in control group Follow‐up period: daily follow‐up until complete healing Exclusions and losses to follow‐up: none Sample size calculation: not reported |

|

| Participants |

PACK‐CXL:

Standard therapy (control):

Overall:

Group differences: mean size of the ulcer was larger in the PACK‐CXL group than in the control group Inclusion criteria: aged > 18 years, seeking treatment at the Cornea Clinic of the Research Institute of Ophthalmology, infective corneal ulcer with a possible bacterial, fungal, Acanthamoeba, or mixed origin, evident corneal melting Exclusion criteria: aged 18 years or younger, corneal ulceration in proximity (1 mm) to the corneal limbus, underlying autoimmune disease, history of herpetic eye disease, corneal thickness less than 400 micrometers with epithelium, or pregnancy or nursing |

|

| Interventions |

PACK‐CXL: initial antimicrobial therapy was done for both groups (see comparator group). Corneas thicker than 500 micrometers were deswelled using 70% glycerol drops applied topically at intervals of 2 to 3 seconds for 5 minutes. Iso‐osmolar riboflavin drops were instilled topically on the cornea every 2 minutes for over 30 minutes. Cornea was illuminated using UVX lamp at 365 nm ultraviolet A with an irradiance of 3 mW/cm² for 30 minutes and a total dose of 5.4 J/cm², during which riboflavin was instilled every 2 minutes and corneal pachymetry performed every 5 minutes. Antimicrobial treatment was continued as before and daily follow‐up examination was performed until healing was complete. Standard therapy: initial antimicrobial therapy for both groups consisted of fortified vancomycin eye drops 50 mg/mL, fortified ceftazidime eye drops 50 mg/mL hourly, and the antifungal agent itraconazole 100 mg orally twice daily. Daily follow‐up examination was performed until healing was complete. |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome:

Secondary outcome: not reported Time points measured:

Adverse effects related to PACK‐CXL for bacterial keratitis: "no severe complications occurred in the PACK‐CXL group" Unit of analysis: eyes |

|

| Notes |

Enrollment period: 2010 to 2013 Funding source: not reported Conflicts of interest: FH is co‐inventor of the PCT/CH 2012/000090 application (ultraviolet light source) Trial registration: not reported |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Randomized using alternate allocation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Randomized using alternate allocation |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | As reported in the review protocol, the nature of surgical studies means that masking of participants is impossible. We therefore considered the overall review as at high risk of bias in this domain. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All outcome data available. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The Research Institute of Ophthalmology Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | 1 of the study authors is a co‐inventor of an ultraviolet light source. |

PACK‐CXL: Photoactivated chromophore for collagen cross‐linking; SD: Standard deviation; NR: Not reported; BCVA: Best corrected visual acuity; IQR: Interquartile range; UVA: Ultraviolet A; BPVA: Best pinhole‐corrected visual acuity

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Abbouda 2016 | Ineligible study design |

| Abbouda 2018 | Ineligible study design |

| Choi 2014 | Ineligible patient population |

| CTRI/2015/07/006000 | Ineligible intervention |

| Ferrari 2013 | Ineligible study design |

| Hafezi 2012 | Ineligible study design |

| Hafezi 2014 | Ineligible study design |

| Hafezi 2016 | Ineligible study design |

| IRCT2016112231028N1 | Ineligible intervention |

| ISRCTN21432643 | Ineligible study design |

| Letko 2011 | Ineligible study design |

| Letsch 2015 | Ineligible study design |

| Li 2013 | Ineligible study design |

| Martinez 2018 | Ineligible study design |

| NCT01464268 | Ineligible intervention |

| NCT02349165 | Ineligible patient population |

| NCT02863809 | Ineligible intervention |

| NCT03041883 | Ineligible patient population |

| NCT03138785 | Ineligible patient population |

| NCT03801590 | Ineligible study design |

| NCT03918408 | Ineligible intervention |

| Poli 2013 | Ineligible study design |

| Price 2013 | Ineligible intervention |

| Rapuano 2017 | Ineligible patient population |

| Stulting 2012 | Ineligible study design |

| Titiyal 2018 | Ineligible patient population |

| Tzamalis 2019 | Ineligible intervention |

| Uddaraju 2015 | Ineligible patient population |

| UMIN000006530 | Ineligible study design |

| UMIN000011350 | Ineligible study design |

| UMIN000023530 | Ineligible study design |

| UMIN000029466 | Ineligible study design |

| Vinciguerra 2013 | Ineligible study design |

| Wei 2019 | Ineligible patient population |

| Zhang 2013 | Ineligible study design |

Characteristics of studies awaiting classification [ordered by study ID]

NCT02088970.

| Methods |

Study design: randomized controlled trial, parallel group Planned enrollment: 38 Length of follow‐up: 3 months |

| Participants |

Inclusion criteria: corneal ulcer size between 2 mm and 6 mm, smear and culture positive for bacteria and fungus Exclusion criteria: suspected viral keratitis, suspected Acanthamoeba keratitis, corneal thinning of more than 50%, pregnancy, history of previous collagen cross‐linking |

| Interventions |

PACK‐CXL: UVA collagen cross‐linking at 3 mW/cm² for 30 minutes, followed by antibiotic treatment Standard therapy: antibiotic treatment alone |

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome:

Secondary outcomes:

Time points measured: 1 week, 1 month, 3 months |

| Notes |

Funding source: not reported Note: study was discontinued due to difficulty recruiting participants. |

NCT02865876.

| Methods |

Study design: randomized controlled trial, parallel group Planned enrollment: 264 Length of follow‐up: 3 months |

| Participants |

Inclusion criteria: infectious keratitis including bacterial or mycotic keratitis with size larger than 3 mm, aged 18 years or older Exclusion criteria: herpetic keratitis, Acanthamoeba keratitis, pregnancy, endophthalmitic, systemic immunosuppression |

| Interventions |

Accelerated PACK‐CXL: conventional therapy (moxifloxacin 0.5% for bacterial keratitis or natamycin for mycotic keratitis) plus accelerated cross‐linking (Avedro Inc, Waltham, USA) under topical anesthesia using 0.1% riboflavin (Vibex, Avedro Inc, Waltham, USA) for 10 minutes and irradiation 30 mW/cm² during 3 minutes. Followed by conventional treatment Standard therapy with placebo surgery: placebo surgery. Followed by conventional treatment |

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome:

Secondary outcome:

|

| Notes | Funding source: Instituto de Oftalmología Fundación Conde de Valenciana |

PACTR201701001843366.

| Methods |

Study design: randomized controlled trial, parallel group Planned enrollment: 78 Length of follow‐up: 3 months |

| Participants |

Inclusion criteria: diagnosis of infectious keratitis, central corneal thickness of more than 400 microns with epithelium, infiltrates involving less than 250 microns depth of corneal thickness, ≥ 18 years of age Exclusion criteria: perforated corneal ulcers, scleral involvement, total corneal involvement, endophthalmitis, viral keratitis, pregnancy |

| Interventions |

PACK‐CXL: PACK‐CXL with medical treatment for infectious keratitis Standard therapy: medical treatment alone |

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome: healing rate Secondary outcome: uncorrected and best‐corrected visual acuity Time points measured: 3 months |

| Notes | Funding source: "Main contributor" |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

ACTRN12611000189921.

| Study name | Corneal collagen cross‐linking (CXL) as an adjunct in the treatment of microbial keratitis |

| Methods |

Study design: randomized controlled trial, parallel group Planned enrollment: 298 Length of follow‐up: 1 month |

| Participants |

Inclusion criteria: presumed or confirmed microbial keratitis of moderate severity or worse Exclusion criteria: pregnancy, impending or actual corneal perforation |

| Interventions |

PACK‐CXL: riboflavin 0.1% in dextran solution is applied to the cornea every 2 minutes for 30 minutes, and then ultraviolet A light at 365 nm and 3 watts/cm² exposure is applied for a further 30 minutes Standard therapy: conventional topical antibiotic therapy, commencing with broad‐spectrum antibiotics such as ofloxacin 0.3%, 1 drop every hour for 24 hours and then modification of dosage according to clinical response |

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome:

Secondary outcome:

|

| Starting date | 2011; primary completion date not reported |

| Contact information |

Primary contact: Laurence Sullivan Address: Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital, 32 Gisborne Street, East Melbourne, Vic 3002, Australia Email: laurence.sullivan@gmail.com |

| Notes | Funding source: Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital |

CTRI/2019/01/017136.

| Study name | Steroids and Cross‐linking for Ulcer Treatment (SCUT II) |

| Methods |

Study design: randomized controlled trial, parallel group Planned enrollment: 270 Length of follow‐up: 3 months |

| Participants |

Inclusion criteria: corneal ulcer that is smear positive for typical bacteria, moderate to severe vision loss (20/40 or worse), corneal thickness < 300 micrometers, aged 18 to 90 years Exclusion criteria: evidence of concomitant infection, impending perforation at recruitment, involvement of sclera, non‐infectious or autoimmune keratitis, history of corneal transplantation or recent intraocular surgery, pinhole visual acuity worse than 20/200 in the unaffected eye |

| Interventions |

PACK‐CXL: collagen cross‐linking with UVA 1 time at presentation and riboflavin with difluprednate 0.05% 4t/d for 1 week followed by tapering doses, decreased by 1 drop weekly for a total of 4 weeks of steroid therapy with moxifloxacin Standard therapy with difluprednate: difluprednate 0.05% 4t/d for 1 week followed by tapering doses, decreased by 1 drop weekly for a total of 4 weeks of steroid therapy with moxifloxacin Standard therapy: moxifloxacin 0.5% eye drops hourly till ulcer heals |

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome:

Secondary outcome:

|

| Starting date | January 2019 |

| Contact information |

Primary contact: N Venkatesh Prajna Address: Aravind Eye Hospital, 1, Anna Nagar, Madurai, Tamil Nadu Email: prajna@aravind.org |

| Notes | Funding source: National Eye Institute |

CTRI/2019/02/017601.

| Study name | Collagen cross linking as adjunctive treatment for corneal ulcer |

| Methods |

Study design: randomized controlled trial, parallel group Planned enrollment: 50 Length of follow‐up: weekly review until healing of epithelial defect |

| Participants |

Inclusion criteria: aged 20 to 80 years, male, corneal ulcer size between 2 mm and 6 mm, smear and culture positive for bacteria and fungus Exclusion criteria: suspected viral keratitis, suspected Acanthamoeba keratitis, corneal thinning of more than 50%, pregnancy, history of previous collagen cross‐linking |

| Interventions |

PACK‐CXL: collagen cross‐linking for 30 minutes with UVA (365 nm) and riboflavin drops Standard therapy with placebo surgery: artificial blue light with lubricant tear drops for 30 minutes |

| Outcomes |

Primary outcomes:

Secondary outcome:

|

| Starting date | January 2018 |

| Contact information |

Primary contact: N Venkatesh Prajna Address: Aravind Eye Hospital, 1, Anna Nagar, Madurai, Tamil Nadu Email: prajna@aravind.org |

| Notes | Funding source: Christian Medical College |

NCT02570321.

| Study name | Cross‐linking for corneal ulcers treatment trial |

| Methods |

Study design: randomized controlled trial, parallel group Planned enrollment: 266 Length of follow‐up: 12 months |

| Participants |

Inclusion criteria: corneal ulcer that is smear positive for either bacteria or filamentous fungus, pinhole acuity worse than 20/70 in the affected eye, not treated already with antimicrobial medications at presentation, aged 18 years or older, basic understanding of the study, commitment to return for follow‐up visits Exclusion criteria: evidence of concomitant infection on exam or Gram stain, impending or frank perforation at recruitment, involvement of sclera at presentation, non‐infectious or autoimmune keratitis, history of corneal transplantation or recent intraocular surgery, no light perception in the affected eye, pinhole visual acuity worse than 20/100 in the unaffected eye, decisionally or cognitively impaired |

| Interventions |