Abstract

Introduction

Diabetes and its complications are a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the Philippines. The prevalence of diabetes in the Philippines has increased from 3.4 million in 2010 to 3.7 million in 2017. The government has formulated strategies to control this increase, for example, through its non-communicable disease prevention and control plan. However, there is scarce research on the financial burden of diabetes. Filling this gap may further help policymakers to make informed decisions while developing and implementing resource planning for relevant interventions. The primary objective of the current study is to estimate the direct medical costs associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

Methods and analysis

This is a 1-year retrospective cohort study of patients with T2DM in 2016. Data will be collected from: (1) hospital databases from public institutions to estimate the cost of diabetes treatment and (2) physician interviews to estimate the cost of management of diabetes in outpatient care. We will perform descriptive and comparative analyses on direct medical costs and healthcare resource utilisation, stratified by the presence of diabetes-associated complications.

Ethics and dissemination

Research ethics board approval has been obtained from the Department of Health Single Joint Research Ethics Board and Cardinal Santos Medical Center Research Ethics Review Committee. Findings from the study will be reported in peer-reviewed scientific journals and local researcher meetings.

Keywords: diabetes & endocrinology, primary care, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

First comprehensive study on the direct medical costs of type 2 diabetes in the Philippines.

Triangulation of multiple data sources, including both databases and physician interviews.

Selection of hospitals is not representative of all hospitals in the Philippines.

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes has become one of the most challenging public health issues globally. The prevalence of diabetes quadrupled from 108 million persons in 1980 to 422 million persons in 2014.1 Rising prevalence of complications was also observed.2 In the Philippines, the number of people with diabetes has increased from 3.4 million in 20103 to 3.7 million in 2017.4 Each day, there are at least 100 deaths due to diabetes-related acute or chronic complications.5 According to a survey conducted in 2008, among 770 Filipinos with diabetes who were recruited from general hospitals, diabetes clinics and referral clinics, 85% of the patients had uncontrolled diabetes6 with haemoglobin A1c >7.0%.7 Almost all patients (99%) had cardiovascular complications. Other common complications included foot complications (82%), nephropathy (81%), neuropathy (67%) and eye complications (62%).

The cost burden of diabetes particularly affects patients in low-income and middle-income countries.8 The presence of complications could also potentially increase the medical expenditure, which has a profound impact on the direct health system costs of diabetes.9 10 The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) reported that the mean overall diabetes-related expenditure per person with diabetes in the Philippines has increased from US$61 in 20103 to US$234 in 2017, indicating a growing financial burden.4 However, detailed and comprehensive cost data for diabetes and its complications remain scant and fragmented.3 4 11 12 Average costs of a few direct medical and indirect cost components were reported in a study conducted among 359 respondents recruited from different levels of healthcare settings in 2008. Oral medications, insulin and transportation cost per visit were reported to be US$13/month, US$20/month and US$1/visit, respectively.12 Other components of direct medical costs, such as laboratory tests and procedures, were not part of the research scope.

Healthcare and financing in the Philippines are fragmented and varied.13 Estimating the burden of chronic diseases could be challenged by the presence of multiple morbidities and the lack of reliable and publicly available data sources. The current arsenal of costing methodologies is also limited to infectious diseases,14 15 or inpatient costing16 from the use of the PhilHealth database, and may not be suitable for estimating the burden of chronic diseases. Therefore, this study methodology aims to detail the methodology for estimating the direct medical costs of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in the Philippines.

Methods and analysis

A prevalence-based approach using the healthcare system perspective will be used to estimate the annual direct medical costs of diabetes management in the Philippines in 2016.17 Data will be collected from hospital electronic health records (EHR) and physician interviews. Results will be reported according to the REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected Data statement.18

Patient and public involvement

No patients are involved throughout the study.

Description of data sources

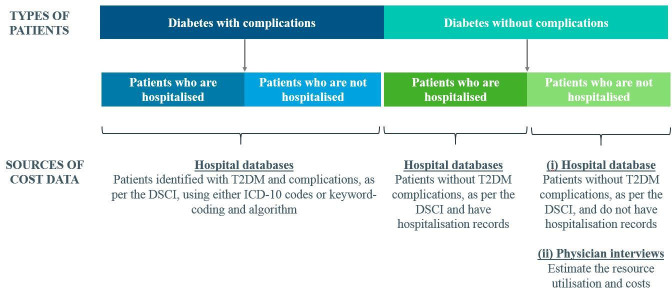

Data will be extracted by the respective institutions, excluding patients’ identifiable details such as names, identification numbers, addresses and dates of birth, as per Data Privacy Act of 2012.19 Methodology on the estimation of the annual cost per capita for patients with and without complications is summarised in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Sources of cost data for each group of patients with T2DM. DSCI, Diabetes Severity Complications Index; ICD, International Statistical Classification of Diseases; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Hospital databases will be used to estimate the prevalence and cost of diabetes and its complications. Data will be obtained from the Ospital ng Makati (ONM; 300-bed, tertiary or level 3 public hospital) in Makati City, Metro Manila and the National Kidney and Transplant Institute (NKTI; 400-bed, level 3 referral public hospital which also provides private healthcare services) in Quezon City, Metro Manila. General hospitals in the Philippines are categorised into different levels based on functional capacity. Level 3 hospitals have the most advanced technology and are concentrated in Metro Manila and Central Luzon. Level 1 hospitals are well-distributed throughout the country but have more limited resources.13 These two hospitals were selected because of their good availability and quality of data due to their EHR systems. These databases were also assessed based on the 3×3 data quality assessment. The profile of eligible patients will include those who are national citizens, aged 18 or above, and are diagnosed with T2DM. Patients with T2DM will be identified by the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) code E11 from the database of NKTI. Specific keywords from the list of diagnoses in the Diabetes Severity Complications Index (DSCI) and algorithms are used to search for patients with T2DM and its complications from the free-text diagnosis in the database of ONM. This data extraction is conducted by two independent coders using different algorithms. A reviewer will then reconcile the differences in coding. Table 1 outlines the variables to be extracted from all hospital databases.

Physician interviews will be used to estimate the resource utilisation of patients seeking diabetes care in outpatient settings. It is more important to provide validity and insights on outpatient diabetes care instead of being representative of all physicians in the Philippines. Therefore, the study will use a purposive sampling of 50 physicians to achieve the diversity of institutions/clinics in Metro Manila. In the Philippines, patients receive diabetes care mainly from endocrinologists, diabetologists, internal medicine doctors or family medicine doctors. Interviews will be conducted with endocrinologists, diabetologists, internal medicine doctors and family medicine doctors in Makati City and Quezon City within Metro Manila to capture the cost of diabetes care comparable to the data collected from ONM and NKTI, respectively. Survey questions will include typical resource utilisation of patients seeking diabetes consultations, such as frequency of visits and monitoring tests. Table 2 shows the distribution of 24 physicians who will be recruited from Makati City and 26 physicians from Quezon City. Physicians will be recruited from IQVIA’s master list of physicians via telephone calls. The eligibility criteria for participation in the survey include the following: at least 8 years of experience in the speciality or 15 years in family medicine; at least 5 years of practice in private outpatient hospital or clinic and treating at least a hundred individuals with diabetes per month. Physicians will be explained the purpose and procedures of the study, and those who agree will provide written informed consent. Interviews will be conducted face-to-face and are expected to last 30 to 45 minutes each.

Table 1.

Variables to be extracted from hospital databases

| Variable | Scale | Unit | Records to extract during study time period |

| Patient (pseudo)identifier | Categorical | Unique patient ID as recorded in database | Record at the index |

| Age at index | Numerical | years | Record at or closest to the index |

| Gender | Categorical | 0=female, 1=male | Record at or closest to the index |

| Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) | Continuous | % | All records during the study period |

| Blood glucose levels | Continuous | mmol/L | All records during the study period |

| Triglyceride levels | Continuous | mg/dL | All records during the study period |

| LDL/HDL | Continuous | No units | All records during the study period |

| Serum creatinine | Continuous | µmol/L | All records during the study period |

| UACR | Continuous | mg | All records during the study period |

| Dyslipidaemia | Character | ICD-10 codes | All records from the database |

| Hypertension | Character | ICD-10 codes | All records from the database |

| Name of drugs prescribed | Character | Name of pre-specified drug in database | All records during the study period |

| Date of drugs prescribed | Date | dd/mm/yyyy | All records during the study period |

| Quantity of drug prescribed | Continuous | As noted | All records during the study period |

| Strength of drug prescribed (dose) | Continuous | As noted mg | All records during the study period |

| Costs of drug prescribed | Continuous | PHP | All records during the study period |

| Date and type of healthcare resource use (eg, GP visits, hospitalisation/ICU/discharge/ER) | Continuous | dd/mm/yyyy | All records during the study period |

| Procedures | Categorical | ICD-9-CM | All records during the study period |

| Laboratory tests | Categorical | As noted | All records during the study period |

| Costs of healthcare resource use (eg, GP visits, hospitalisation, medical supplies) | Continuous | PHP | All records during the study period (medications, outpatient services, emergency visits and inpatient hospitalisations) |

| Professional fees | Continuous | PHP | All records in the database |

| Diagnosis of complications, as per DSCI | Categorical | ICD-10 codes | All records during the study period |

DSCI, Diabetes Severity Complications Index; ER, emergency room; GP, General Practice; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; ICD, International Statistical Classification of Diseases; ICU, Intensive Care Unit; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; PHP, Philippine Peso; UACR, urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio.

Table 2.

Sample distribution for physician interviews

| Endocrinology | Diabetology | Family medicine | Internal medicine | Total | |

| Makati city | |||||

| Public facilities | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Private facilities | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 16 |

| Total | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 24 |

| Quezon city | |||||

| Public facilities | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Private facilities | 8 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 18 |

| Total | 10 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 26 |

| Overall total | 18 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 50 |

Outcomes

The outcome of interest is the mean direct medical costs in patients with diabetes complications and those without complications.

Direct medical costs of patients with and without complications will be estimated.

Diabetes with complications. Annual health expenditure per patient would be calculated from patients identified with complications, as outlined in the DSCI. This group of patients will be further categorised into patients with and without hospitalisation records in the year 2016.

Diabetes without complications. The annual cost of each patient without complications is determined from the hospital databases and the physician interviews. In the latter, physicians will estimate the resources needed to manage patients with diabetes and comorbidities, namely hypertension and dyslipidaemia. Resource utilisation will be multiplied by average unit costs to estimate the per capita cost for each patient group: (a) diabetes only, (b) diabetes and hypertension, (c) diabetes and dyslipidaemia and (d) diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidaemia. Unit costs of treatment and tests will be obtained from the administrator or fee schedule of each physician’s affiliated institution/clinic.

Data management

The dataset from each institution will be managed independently. Resource utilisation will be standardised across each institution and categorised into the following: drugs, procedures, dialysis, surgery, supplies and others.

Strengths and limitations

Although this study is fortified with data from the leading hospitals in the Philippines, with complete electronically captured data, it is not without limitations. Generalisability of this study could be limited by the selection of hospitals, as they may not be representative of all hospitals in the Philippines. These hospitals provide tertiary care and are mainly serving as referral centres in Manila. Hence, these institutions are more likely to see patients with more severe conditions. Another limitation could be the possibility of missing out T2DM patients whose diagnoses did not include T2DM. However, this is unlikely to affect the average cost, as the absence of the T2DM diagnosis is not related to any outcome. Future studies should include more hospitals to improve the generalisability of the study findings.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval has been obtained from the Department of Health Single Joint Research Ethics Board and Cardinal Santos Medical Center Research Ethics Review Committee. On study completion and finalisation of the study report, the results of this non-interventional study will be submitted for publication in a scientific journal. Results could also be presented to policymakers or local researchers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to recognise valuable input from Dr Praful Chakkarwar, Mr Henrik Bendix Dahl, Dr Ahsan Shoeb, Dr Ma Teresa Dioko, Dr Chritopher Cipriano, Dr Francisco Soria, Miss Sirinthip Petcharapiruch and Miss Thuy Thanh Nguyen in the initial conceptualisation of this study. We would also like to thank Miss Evanthia Achilla for her constructive criticism of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: The study steering committee consists of the principal investigator (CJ), author (JYSN), statistician (IJC), three additional site investigators (RAS, RM and PDLP), four co-investigators (AP, RT, MS and DB) and two representatives from the funder (one clinician, Dr Praful Chakkarwar, and one study advisor, EW). JYSN is the main content author and collaborates with the local academic on the overall study approach. IJC is the content expert for the modelling approach and will be carrying out the analysis. He also helped write the manuscript. CJ leads the study, provides guidance to the study approach and commented on the drafts of the manuscript. RAS, RM, PDLP are the site principal Investigators, with equal contribution. They are responsible for the data collection from hospitals, and are involved in all aspects of the study. The rest of the authors (AP, RT, MS and DB) have equal contribution, oversee the study conduct and are involved in all related discussions. All authors have access to the de-identified raw and final study data, and will be responsible for data interpretation, preparation of the report and the decision to submit for publication. EW provides guidance to the study and critically reviewed and commented on the report.

Funding: This study is funded by Novo Nordisk to support the investigators and data collection. This study is conducted by IQVIA Singapore.

Competing interests: JYSN and IJC served as consultants to Novo Nordisk and CJ, RAS, RM, PDLP, AP, RT and DB receive research support from Novo Nordisk. EW is an employee of Novo Nordisk.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.NCDRF Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: a pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4.4 million participants. Lancet 2016;387:1513–30. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00618-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harding JL, Pavkov ME, Magliano DJ, et al. Global trends in diabetes complications: a review of current evidence. Diabetologia 2019;62:3–16. 10.1007/s00125-018-4711-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.IDF Diabetes atlas. 4th edn Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.IDF Diabetes atlas. 8th edn Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO Noncommunicable Diseases (NCD) country profiles, 2014. WHO Document Production Services, Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jimeno CA, Sobrepeña LM, DiabCare MRC. DiabCare 2008: survey on glycaemic control and the status of diabetes care and complications among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Philippines. Philipp J Intern Med 2012;50:15–22. [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Diabetes Association Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2017. Diabetes Care 2018;41:917–28. 10.2337/dci18-0007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seuring T, Archangelidi O, Suhrcke M. The economic costs of type 2 diabetes: a global systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics 2015;33:811–31. 10.1007/s40273-015-0268-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kähm K, Laxy M, Schneider U, et al. Health care costs associated with incident complications in patients with type 2 diabetes in Germany. Diabetes Care 2018;41:971–8. 10.2337/dc17-1763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhuo X, Zhang P, Barker L, et al. The lifetime cost of diabetes and its implications for diabetes prevention. Diabetes Care 2014;37:2557–64. 10.2337/dc13-2484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beran D, Higuchi M. Delivering diabetes care in the Philippines and Vietnam: policy and practice issues. Asia Pac J Public Health 2013;25:92–101. 10.1177/1010539511412177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higuchi M. Access to diabetes care and medicines in the Philippines. Asia Pac J Public Health 2010;22:96S–102. 10.1177/1010539510373005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Health Policy Development and Planning Bureau (HPDPB) Health sector reform agenda Monographs : National objectives for health 2011-2016. Manila, the Philippines, 2012: 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edillo FE, Halasa YA, Largo FM, et al. Economic cost and burden of dengue in the Philippines. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2015;92:360–6. 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tumanan-Mendoza BA, Mendoza VL, Frias MVG, et al. Economic burden of community-acquired pneumonia among pediatric patients (aged 3 months to < 19 years) in the Philippines. Value Health Reg Issues 2017;12:115–22. 10.1016/j.vhri.2017.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner AK, Valera M, Graves AJ, et al. Costs of hospital care for hypertension in an insured population without an outpatient medicines benefit: an observational study in the Philippines. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:161. 10.1186/1472-6963-8-161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larg A, Moss JR, studies C-of-illness. Cost-of-illness studies: a guide to critical evaluation. Pharmacoeconomics 2011;29:653–71. 10.2165/11588380-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al. The reporting of studies conducted using observational Routinely-collected health data (record) statement. PLoS Med 2015;12:e1001885. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Data Privacy Act of 2012 Metro manila. The Philippines, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.