Abstract

The rodlet structure present on the Aspergillus fumigatus conidial surface hides conidia from immune recognition. In spite of the essential biological role of the rodlets, the molecular basis for their self-assembly and disaggregation is not known. Analysis of the soluble forms of conidia-extracted and recombinant RodA by NMR spectroscopy has indicated the importance of disulfide bonds and identified two dynamic regions as likely candidates for conformational change and intermolecular interactions during conversion of RodA into the amyloid rodlet structure. Point mutations introduced into the RODA sequence confirmed that (1) mutation of a single cysteine was sufficient to block rodlet formation on the conidial surface and (2) both presumed amyloidogenic regions were needed for proper rodlet assembly. Mutations in the two putative amyloidogenic regions retarded and disturbed, but did not completely inhibit, the formation of the rodlets in vitro and on the conidial surface. Even in a disturbed form, the presence of rodlets on the surface of the conidia was sufficient to immunosilence the conidium. However, in contrast to the parental conidia, long exposure of mutant conidia lacking disulfide bridges within RodA or expressing RodA carrying the double (I115S/I146G) mutation activated dendritic cells with the subsequent secretion of proinflammatory cytokines. The immune reactivity of the RodA mutant conidia was not due to a modification in the RodA structure, but to the exposure of different pathogen-associated molecular patterns on the surface as a result of the modification of the rodlet surface layer. The full degradation of the rodlet layer, which occurs during early germination, is due to a complex array of cell wall bound proteases. As reported earlier, this loss of the rodlet layer lead to a strong anti-fumigatus host immune response in mouse lungs.

Keywords: Aspergillus fumigatus, Hydrophobins, Rodlets, RodA, Amyloids

1. Introduction

Aerial conidia of Ascomycetes and Basidiomycetes are coated with a layer of hydrophobin proteins organized in fibrillar structures known as rodlets. The rodlet layer is amphipathic, and the outward facing hydrophobic surface renders the conidial surface resistant to wetting, thus facilitating effective dispersal of conidia in the air (Gebbink et al., 2005, Sunde et al., 2008). Fungal hydrophobins are small secreted proteins with eight cysteine residues ordered in a distinct way and with characteristic hydropathy patterns, which define two well-characterized classes I and II and a third intermediate class named III (Gandier et al., 2017, Kershaw and Talbot, 1998, Littlejohn et al., 2012, Pedersen et al., 2011, Wessels, 1994). Class I hydrophobin assemblies are generally water- and detergent-insoluble, have an amyloid structure and form the patterned rodlet layer observed in conidia (Butko et al., 2001, de Vocht et al., 2000, Mackay et al., 2001). Class II hydrophobin sequences are generally shorter than class I hydrophobin sequences and are soluble in aqueous ethanol mixtures and SDS. The intermediate class III has the same cysteine pattern but lacks a consistent hydropathy profile characteristic of either class I or class II hydrophobins (Jensen et al., 2010, Littlejohn et al., 2012).

In addition to the role of the rodlet layer in fungal life during conidiogenesis and conidial dispersal in the air, it has been shown that rodlets have a role in fungal–host interactions and favor the pathogenic behaviour of fungal pathogens in mammals, plant and insect hosts (Aimanianda et al., 2009, Talbot et al., 1996, Zhang et al., 2011) or play a positive role during plant symbiosis (Whiteford and Spanu, 2002). Moreover, due to their specific physicochemical properties, hydrophobins have potential for numerous biotechnological applications (Piscitelli et al., 2017, Wösten and Scholtmeijer, 2015, Zhao et al., 2009). Their coating properties could be used to functionalize metals and plastic or carbon nanotubes in order to prevent the formation of bacterial biofilms or to immobilize enzymes on surface (Tanaka et al., 2017) or to stabilize pharmaceutical emulsions and facilitate drug delivery (Artini et al., 2017).

Our current study is focused on the RodA hydrophobin of A. fumigatus, the major airborne opportunistic fungal pathogen of humans. This hydrophobin forms rodlets on the surface of A. fumigatus conidia (Paris et al., 2003, Thau et al., 1994). This surface rodlet coat masks the conidium from host detection and its removal from the conidial surface initiates the antifungal host immune response (Aimanianda et al., 2009). Despite their prominent morphological and biological role, the molecular basis for rodlet self-assembly and disaggregation in this fungal species has not yet been understood. By analysing the structure of the soluble form of RodA and by creating point mutations in the RODA gene, we report here on the mechanism that drives RodA to assemble into highly ordered structures anchored to the conidial surface. Moreover, we have also investigated the biochemical events responsible for the lysis of the rodlet layer, a key step in the recognition and mounting of an immune response to this airborne pathogen by host cells.

2. Results

2.1. Solution structure and dynamics of RodA

The structure of RodA was studied by NMR spectroscopy. Comparison of the 1H-15N HSQC spectra of recombinant RodA (rRodA) and the HPLC purified hydrofluoric acid-extracted RodA from conidia indicated that both proteins have the same structure, the same cysteine redox state and potential disulfide pairing (Supplementary Material Fig. S1). Additionally, the native protein did not contain any post-translational modification such as an O- or N-glycosylation. This was confirmed by mass spectrometry (MS) of proteolysis fragments of the full-length conidia-extracted protein before or after chemical treatment with the N- and O-deglycosylating agent trifluoromethanesulfonic acid (data not shown). We thus performed further work using the recombinant protein expressed in E. coli that could be purified in greater amounts than the native conidial RodA. Analysis of the cysteine redox state as proposed by Sharma Rajarathnam (Sharma and Rajarathnam, 2000) indicated that the Cys residues of rRodA were oxidized and hence, involved in disulfide bridges. Distance (nOe) data and topology of rRodA allowed us to unambiguously establish the disulfide pairing of rRodA, which corresponded to the one observed in all other studied hydrophobins (C1-C6: 56-133; C2-C5: 64-127; C3-C4: 65-105; C7-C8: 134-152) (Fig. 1). Cysteines are numbered according to their order of appearance in the sequence from C1 to C8 or by their sequence number throughout the manuscript.

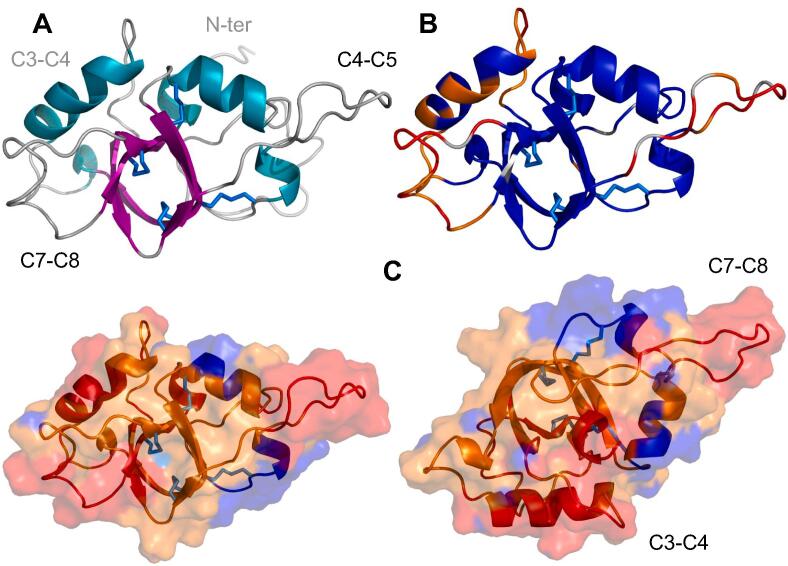

Fig. 1.

Structure (A), internal dynamics (B) and hydrophobicity (C) of monomeric RodA (best energy conformer). A: Strands are shown in magenta, helices in cyan and disulfide bridges in marine blue. The inter cysteine regions on the front (grey) and back (light grey) as well as the N-terminal region are indicated. Cysteines are numbered by their order in the sequence throughout this paper. B: Backbone amide 1H-15N heteronuclear nOe values are shown on the cartoon representation of the structure: highly flexible (nOe < 0.45), flexible (0.45 ≤ nOe ≤ 0.65), rigid (nOe > 0.65) and missing-value backbone residues are shown in red, orange, blue and grey, respectively. The structure is shown in a different orientation on the right. C: The hydropathy profile calculated with the Eisenberg hydrophobicity scale (http://web.expasy.org/protscale) is color coded on the surface and cartoon representations of the structure: blue = hydrophilic (Φ ≤ −0.3), orange (−0.3 < Φ < 0.3), red = hydrophobic (Φ ≥ 0.3). The N-terminal disordered region (residues 18–38) is not displayed in B and C. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article).

The structure of RodA (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table S1) is organized around the four-disulfide bonds. It consists of a central β-barrel composed of two curved antiparallel β-sheets (sheet S1: strands 60–65, 104–107, 130–135 and 150–154; sheet S2: strands 65–70, 99–104 and 150–154), two relatively long α-helices (helix H1: 49–56; H2: 79–90), one short α-helix (H4: 123–126) and two short 310- (H3: 96–98; H5: 155–157) helices. Two long and kinked β-strands (60–70 and 99–107) participate in both β-sheets of the β-barrel. Two S-S bonds link together strands of the β-barrel and the other two connect the external face of the β-barrel with the regions of helices H1 and H4. The long α-helix H2 in the C3-C4 region packs against the β-barrel. The structures showed good convergence within the regions with secondary structure, but were more variable for residues 19–39, 109–121 and 137–149 located in the N-terminal, C4-C5 (106–132) and C7-C8 (135–151) inter-cysteine regions, respectively (Fig. S2).

The internal motions of rRodA on the nanosecond-picosecond time scale were analyzed using the backbone amide 1H-15N nOes (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Fig. S3). Low nOe values are indicative of high amplitude internal motions while high nOe values reflect rigidity of the backbone at the fast timescale (ns-ps). The nOe data showed that the secondary structure elements of RodA in the vicinity of disulfide bridges, namely the central β-barrel and α-helices H1 and H4 that are tethered to the β-barrel by S-S bonds are rigid with nOe values higher than 0.71. Helix H2, located in the region between cysteine residues C3 and C4, showed somewhat lower 1H-15N nOe values (0.56 to 0.85) suggestive of low amplitude motions. In contrast, the N-terminal region (19–39) showed negative or very low nOes that indicated that this region was disordered. Residues 109–121 (C4-C5 region), 137–149 (C7-C8 region) and to a lesser extent the flanking regions (74–79 and 90–96) of α-helices H2 and H3 in the C3-C4 region also display low nOe values.

The charge distribution and hydrophobicity of the surface of hydrophobins is important for the recruitment and self-assembly of hydrophobins at a hydrophobic/hydrophilic interface such as the air/water interface (Fig. 1C). The surface of RodA contains a hydrophobic region between C3 and C4 and two highly hydrophobic patches (114–120 and 136–148) in the inter-cysteine regions C4-C5 and C7-C8. A relatively hydrophobic belt joins the hydrophobic and flexible C4-C5 and C7-C8 loops. The belt is lined by charged residues with two pairs of charged residues (E54-K50; K107-D109) that establish salt bridges and compensate their charges. An opposite face of the molecule shows many charged residues with two clusters of negative residues (D73, D76, D78 and E79 in the C3-C4 region and D45 and D46 close to the disordered N-terminal tail) and isolated positive residues (K67, K128 and K55 and K87). Hence, in solution, monomeric RodA shows an amphiphilic character with a hydrophobic face with hydrophobic residues and compensated charges and a more hydrophilic surface with clusters of net charges on the opposite face.

2.2. Molecular identification of the amyloidogenic regions within RodA protein and the amino acids essential for the formation of the rodlets in vitro

Analysis of the RodA sequence by the consensus method Amylpred2 (Tsolis et al., 2013) indicated that stretches of residues (112–117 and 143–147) within the C4-C5 and C7-C8 inter-cysteine regions are predicted as amyloidogenic and could potentially participate in the cross β-sheets at the core of amyloid fibres. To investigate the role of these sequences in the context of the intact protein and interface-driven self-assembly, a number of mutations were introduced into rRodA. Individual or multiple glycine and serine substitutions of isoleucine and leucine residues were used to reduce side chain hydrophobicity and size and to introduce flexibility or polarity at sites within the protein structure. The kinetics of self-assembly of rRodA from the monomeric form into the amyloid rodlet form were monitored by changes in fluorescence of the amyloid binding dye Thioflavin T (ThT) during in vitro self-assembly assays (Fig. 2).

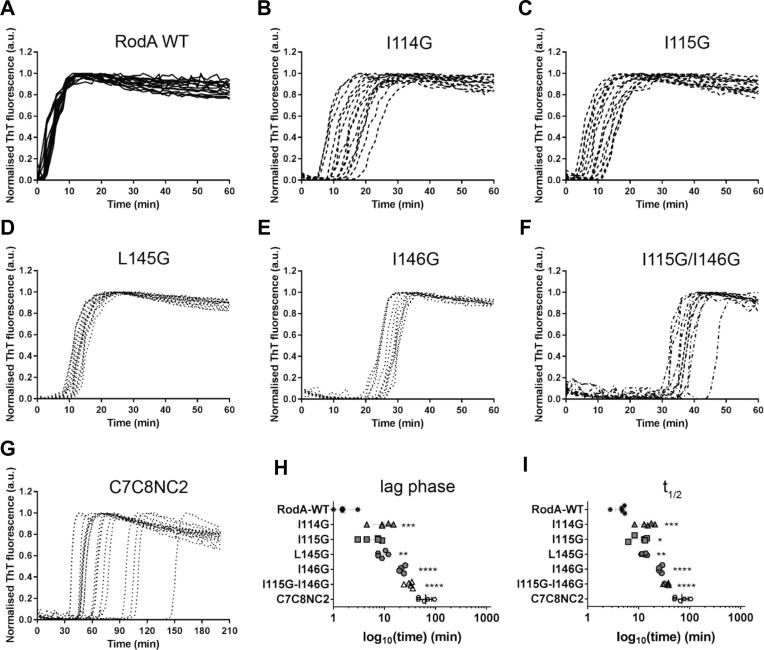

Fig. 2.

The effect of mutation(s) on the kinetics of RodA rodlet self-assembly assessed by Thioflavin T fluorescence at 50 °C. Amyloid assembly profiles for (A) RodA WT; single point mutants (B) RodA I114G, (C) RodA I115G, (D) RodA L145G and (E) RodA I146G; (F) double point mutant RodA I115G/I146G and (G) C7C8NC2 chimera. (H) Lag time and (I) time taken to reach half maximum ThT fluorescence. (See the material and methods section for calculation of lag time and time to reach half maximum).

Only mutations to the rRodA sequence in the C4-C5 loop or in the C7-C8 loop resulted in a delay in self-assembly of rRodA mutants, relative to wild-type (WT) rRodA. Single-residue mutations introduced a significant lag phase of 10–20 min into the self-assembly profile, whereas no lag phase was detected for WT rRodA under these conditions (Fig. 2). The effect of double mutations in the C4–C5 and C7–C8 loops was additive since a rRodA carrying the double slowing mutations I115G/I146G displayed a longer lag phase than rRodA I115G and rRodA I146G (Fig. 2). Mutations introduced in other regions of rRodA outside of the C4–C5 and C7–C8 loops did not have an effect on RodA self-assembly (data not shown). Strikingly, a chimeric protein rRodA C7C8NC2, which has the central sequence of the rRodA C7–C8 loop replaced with the C7–C8 loop from the non-amyloidogenic class II hydrophobin NC2, was able to assemble into ThT-positive structures (Fig. 2). A similar chimera in which the NC2 region was inserted into the hydrophobin EAS did not produce ThT-positive rodlets. These data show that in contrast to the hydrophobin EAS where only the C7–C8 loop is required for rodlet formation (Macindoe et al., 2012), RodA rodlet assembly involves the C4–C5 and the C7–C8 loops.

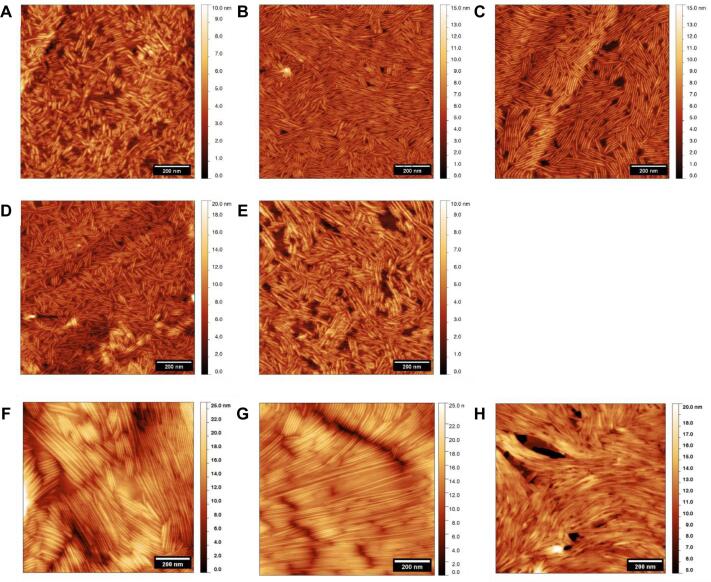

As revealed by atomic force microscopy (AFM) images in Fig. 3A, WT rRodA rodlets have comparable dimensions to those reported for other class I hydrophobins: width of 10.1 ± 1.8 nm and height of 2.0 ± 0.5 nm (Table S2). Introduction of the single mutations between cysteines 4 and 5 (Fig. 3 B,C) and cysteines seven and eight (Fig. 3 D,E) that slowed assembly kinetics did not grossly alter the morphology of the final assembled rodlet structure on a hydrophobic graphite surface (HOPG), as probed by AFM. In contrast, the rRodA protein carrying the double mutation and the rRodA C7C8NC2 chimera did not spontaneously form rodlets when dried onto HOPG at room temperature. However, when rRodA I115G/I146G protein was incubated at 50 °C for 2 h on the graphite surface, it formed a film composed of very long rodlets, as did WT rRodA assembled at this temperature (Fig. 3F, G). The rRodA C7C8NC2 chimera also formed rodlets only when prepared at 50 °C. However, the surface details and lateral packing of the rodlets formed by the chimera were less distinct than observed with WT rRodA rodlets (Fig. 3H).

Fig. 3.

Assembly of RodA WT and mutant proteins on highly oriented pyrolytic graphite. Atomic force micrographs showing the surface morphology of rodlets formed by (A) RodA WT, (B) RodA I114G, (C) RodA I115G, (D) RodA L145G and (E) RodA I146G after incubation at room temperature on graphite surfaces. Surface layers containing rodlets formed by (F) RodA WT, (G) double mutant RodA I115G/I146G and (H) C7C8NC2 chimera after incubation at 50 °C for 2 h. (See the Material and Methods section for the AFM experimental conditions).

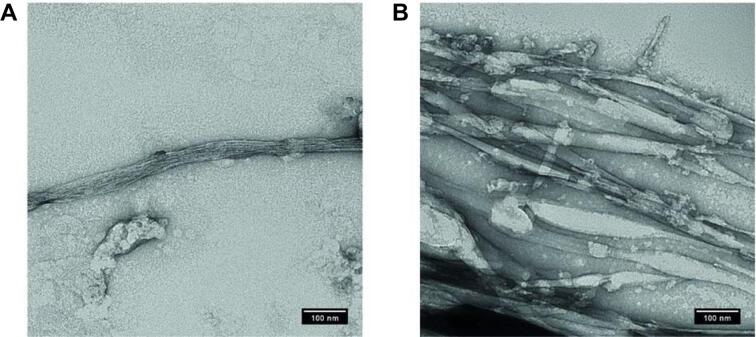

The results obtained with the different point mutated rRodA proteins suggest that while a single amyloidogenic region can support the incorporation of monomers into a fibrillar structure albeit with slower kinetics, the absence of a second interaction within the rodlets causes a morphological disturbance, with consequences for the organization and lateral interactions between rodlets within the film. The self-assembling nature of the sequences between the 4-5th and 7-8th cysteine residues was confirmed by analysis of peptides containing these sequences. Transmission electron microscopy showed that both the peptide PIIGIPIQDL (Fig. 4A) that originates from the C4-C5 region and SLIGL (Fig. 4B) found in the C7-C8 region can form fibrillar structures. In PIIGIPIQDL, fibrillar aggregation occurs at a concentration of 200 µg/ml, with many smaller fibrils bundling together to form a single fibril. The SLIGL peptide formed thicker single fibrils with a crystalline nature at 200 µg/ml.

Fig. 4.

Transmission electron micrographs of fibrillar material formed by (A) PIIGIPIQDL, a peptide derived from the C4-C5 region of RodA and (B) SLIGL, a peptide with predicted amyloidogenic sequence from the C7-C8 region.

2.3. Assembly of the rodlet structure on the conidium

In order to determine the effect of RodA mutations on conidial rodlet assembly, different mutations were also introduced into the RODA gene (Figs. S4 and S5). The effect of these mutations on the rodlet structure on the conidial surface was investigated with AFM (Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7). Incubation of parental strain conidia with hydrofluoric acid (HF) or formic acid (FA) to isolate native RodA always results in the isolation of two protein bands (Aimanianda et al., 2009). MS, N-terminal sequencing and NMR data led to the identification of both molecular species. The higher Mr band corresponds to the full-length protein without the signal peptide with an N-terminal pyroglutamic acid (PCA) arising from a spontaneous deamidation of the N-terminal Gln residue at position 21 (PCA21-L159). The lower Mr species corresponds to the F41-L159 peptide, missing 40 amino acids from the N-terminus. The mutant with a RodA protein corresponding to the band with lower Mr seen in conidial extracts did not show any alteration in rodlet formation on the surface of the conidium (Fig. S4). This result indicates that the N-terminal region, which is unstructured in the monomer, does not play a role in the assembly of the rodlet layer.

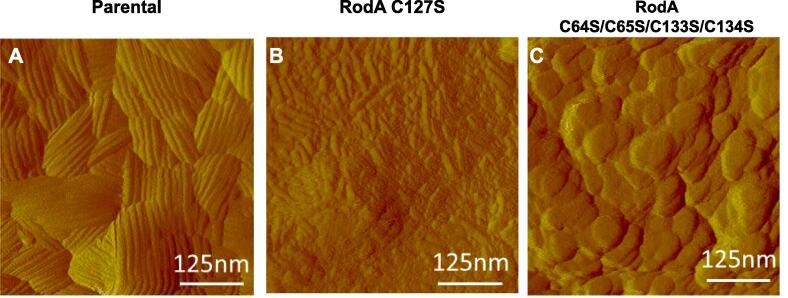

Fig. 5.

Cysteine mutations impair the presence of rodlets at the conidial surface. AFM deflection images showing the structure of conidial surface imaged in liquid conditions for: (A) the parental, (B) one cysteine (C127S) and (C) four cysteine (C64S/C65S/C133S/C134S) mutants.

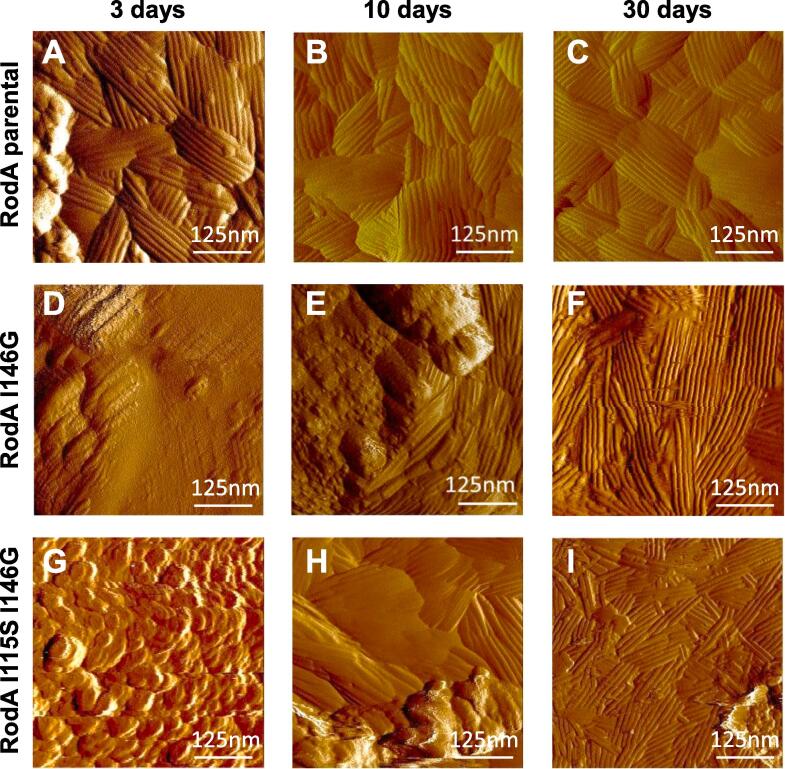

Fig. 6.

Delay in rodlets appearance on the surface of conidia imaged in liquid conditions. AFM deflection images of the rodlets layer for (A-C) the parental, (D-F) I146G and (G-I) I115S/I146G mutants after 3 (A, D, G), 10 (B, E, H) and 30 (C, F, I) days of growth.

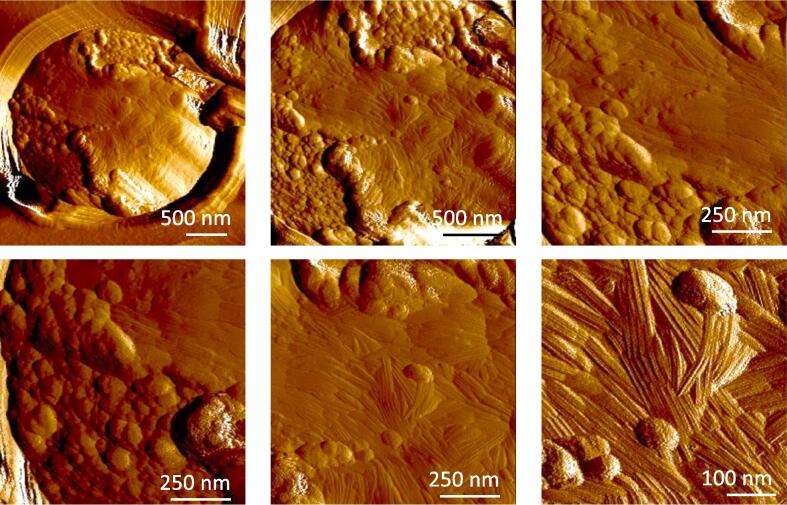

Fig. 7.

The surface of the RodA I115S/I146G double mutant is only partially covered by rodlets. AFM deflections images (at different magnification) representative of the conidium surface of the RodA I115S/I146G double mutant after 30 days of culture with different magnifications.

The role of cysteine bridges in rodlet formation has been characterized earlier in S. commune and M. grisea (de Vocht et al., 2000, Kershaw et al., 2005). Herein, we evaluated the necessity for intact disulfide bridges within RodA for correct rodlet assembly in A. fumigatus by the construction and characterization of mutants with the RODA gene mutated in one cysteine (C127S) or in four of them (C64S/C65S/C133S/C134S) to disrupt one or the four RodA disulfide bridges. None of these mutants produced rodlets on the conidial surface as shown by AFM (Fig. 5). Moreover, negative Western blots of the formic acid extracts of these cysteine mutants with an anti-RodA antibody demonstrated that RodA was not secreted to the conidial surface (Fig. S6).

A. fumigatus mutants harboring the same RodA point mutations as the ones undertaken with the recombinant protein (I114G, I115S, L145S, I146G and I115S/I146G) were generated. Like in the parental strain, RodA could be detected on SDS-PAGE as doublets after HF or FA extraction from all these RodA loop region mutants (Fig. S7). The surface organization of mutants resulting from the point mutations I114G, I115S, L145S, I146G and I115S/I146G was investigated by AFM. The hydrophobicity of the rodlet structure of the RodA I114G, RodA I115S and RodA L145S mutants was not affected, as seen by the adhesion force histograms obtained using chemical force microscopy with hydrophobic AFM tips (Dague et al., 2008b, Dague et al., 2007), data not shown]. In agreement with the ThT data obtained with mutated rRodA in in vitro assays (Fig. 2), the single-point mutation I146G and the double mutation I115S/I146G, which both led to a longer lag phase, affected the assembly of the rodlet layer on the surface of the conidium (Fig. 6). The appearance of the rodlets on the surface of the conidium was dependent on the conidial age. At 3-days of growth, conidia of these two mutants did not show any rodlets on their surface unlike parental conidia; however, the number of rodlets increased with the age of the conidia. The maximal rodlet formation was seen after 30-days of culture without further evolution of the rodlet morphology afterwards. Interestingly, two modifications of the rodlet structure were seen on the mutant conidia: (1) the length of the rodlets significantly increased from 147 nm observed for the parental to 270 and 234 nm for the I146G and I115S/I146G mutants, respectively (Fig. S8); (2) while parental rodlets coated the entire conidium, the coverage of the conidium surface by the mutated rodlets was incomplete, with a coverage ranging from 20 to 50% of the conidial surface for the I115S/I146G mutant (Fig. 7).

In addition, the surfaces of the conidia of the I146G and I115S/I146G mutants were covered at least partially by an amorphous material. MS analysis of the extract obtained after incubation of the conidia in formic acid for 2 h indicated that over 1200 proteins were quantified in the I115S/I146G mutant conidia and this number greatly exceed the number of proteins detected with its parental strain, demonstrating the presence of a much higher concentration of proteins in the mutant cell wall (Data are available via ProteomeXchange with the identifier PXD008503). In spite of differences seen with AFM, a comparable number of proteins were extracted from 10-days or 30-day old I115S/I146G mutant conidia (1399 and 1278 respectively). The identification of the mutated and wild type RodA protein in the extracts from the mutant and parental strains validated the MS experiment. Analysis of proteins with a signal peptide, which are specifically targeted to be secreted to the cell wall, showed that 56 and 68 proteins were present in the cell wall of the 10 and 30-days old conidia, respectively (Table 1). Among the 31 proteins extracted from both 10- and 30-days mutant conidia, some of them such as disulfide isomerases, carboxypeptidases or phiA (Melin et al., 2003, Monod et al., 2002) could be specifically involved in the maturation of RodA. Others such as glucanases, chitinases, transglycosidases or GPI proteins are known to be involved in cell wall modifications (Latgé et al., 2017). Among these proteins, several (Sun1, Crf1, MP1, ChiB1, Aspf4, DPPV) are also known as antigens/allergens in agreement with their cell wall surface localization (Beauvais et al., 1997, Gastebois et al., 2013, Latgé, 1999). The coating of the outer conidial layer by an amorphous material was confirmed by the positive labelling of the conidia of these two mutants with the wheat germ agglutinin and concanavalin A lectins, in contrast with the parental strain (Fig. S9). The hydrophilicity of the I115S/I146G double mutant conidia seen by AFM was due to an incomplete coverage of the conidial surface by the rodlets and to the presence of amorphous (glyco)proteins on the surface of the mutant cell wall. Accordingly, the I115S/I146G mutant conidial colonies appeared black and hydrophilic like the ΔrodA mutant, as did (but to a lesser extent) the conidia from the single I146G mutant (Fig. S10). Complementation of the mutated RODA gene with the wild type gene led to the production of normal hydrophobic conidia displaying the characteristic green color of the parental strain instead of the black color of the mutant conidia (Fig. S10).

Table 1.

Signal-peptide-containing proteins extracted with 2 h incubation in formic acid. Only proteins that are specific of the double mutant conidia RodA I115S/I146G (and absent from the Ku80 parental strain) are listed. (A) 30 days old conidia and (B) 10 days old conidia. The most abundant proteins present in both 30 and 10 days old conidia are listed in (C). Proteins are ranked in decreasing order of abundancy based on iBAQ (intensity Based Absolute Quantification) values. The mean iBAQ is calculated from the three biological replicates. Over 1000 proteins were identified and quantified in the formic acid extracts from each strain and were deposited in the PRIDE data base PXD008503 (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org/cgi/GetDataset).

| A | Signal-peptide-containing proteins extracted with 2h in formic acid from 30d old conidia, present in I115S/I146G and absent in parental strain |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene ID | BLAST Af293 | UniProt | Description | Present in I115S/I146G, absent in parental, 10d | Score of SignalP | Unique sequence coverage (%) | Protein length | MW (kDa) | Mean iBAQ I115S/I146G 30d | Mean Unique Peptides I115S/I146G 30d |

| AFUB_086950 | AFUA_7G00370 | B0YBK6 | Uncharacterized protein | Yes | 0.78 | 29.30 | 198 | 21.384 | 17579000 | 4.0 |

| AFUB_097339 | AFUA_6G00180 | B0YDZ8 | Putative uncharacterized protein | No | 0.74 | 38.50 | 109 | 12.053 | 17425867 | 2.7 |

| AFUB_096860 | AFUA_6G00610 | B0YDU9 | Putative uncharacterized protein | No | 0.85 | 21.40 | 98 | 10.853 | 8641800 | 1.0 |

| AFUB_060890 | AFUA_5G13180 | B0Y1U6 | Agmatinase, putative | Yes | 0.68 | 28.40 | 391 | 42.179 | 7932333 | 6.0 |

| AFUB_059890 | AFUA_5G12260 | B0Y1D4 | Disulfide isomerase (TigA), putative | Yes | 0.87 | 54.60 | 368 | 40.253 | 5965500 | 14.3 |

| AFUB_064740 | AFUA_4G07650 | B0Y5V8 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase | No | 0.92 | 45.00 | 209 | 22.961 | 4038867 | 6.0 |

| AFUB_072730 | AFUA_6G06800 | B0Y766 | Probable carboxypeptidase | Yes | 0.58 | 25.90 | 440 | 46.377 | 3466967 | 5.7 |

| AFUB_083440 | AFUA_8G04120 | B0YA52 | Carboxypeptidase | No | 0.56 | 28.90 | 551 | 61.278 | 2966367 | 8.7 |

| AFUB_059210 | AFUA_5G11640 | B0Y110 | Secretory pathway protein Ssp120, putative | Yes | 0.64 | 36.00 | 203 | 23.277 | 2893100 | 3.7 |

| AFUB_070080 | AFUA_4G13190 | B0Y4S2 | Endosomal cargo receptor (Erv25), putative | Yes | 0.93 | 33.80 | 266 | 30.039 | 2381567 | 4.3 |

| AFUB_091030 | AFUA_7G05450 | B0YCQ5 | SUN domain protein (Uth1), putative | Yes | 0.50 | 23.20 | 414 | 43.504 | 2110200 | 5.3 |

| AFUB_064480 | AFUA_4G07390 | B0Y5T1 | Endosomal cargo receptor (Erp5), putative | No | 0.90 | 20.80 | 231 | 25.863 | 1582933 | 3.0 |

| AFUB_066060 | AFUA_4G08960 | B0Y688 | GPI anchored cell wall protein, putative | No | 0.51 | 11.90 | 386 | 39.611 | 1522767 | 2.3 |

| AFUB_076030 | AFUA_6G09980 | B0Y842 | Patched sphingolipid transporter (Ncr1), putative | Yes | 0.66 | 4.60 | 1273 | 140.400 | 1482511 | 2.3 |

| AFUB_038670 | AFUA_3G10490 | B0XXV2 | DNA damage response protein (Dap1), putative | Yes | 0.69 | 37.40 | 155 | 17.221 | 1454907 | 3.0 |

| AFUB_015530 | AFUA_1G16190 | B0XNL0 | Extracellular cell wall glucanase Crf1/allergen Asp F9 | Yes | 0.77 | 22.50 | 395 | 40.269 | 1212400 | 4.0 |

| AFUB_031800 | AFUA_2G16120 | B0XUX8 | Translocon-associated protein, alpha subunit, putative | Yes | 0.84 | 42.10 | 261 | 28.158 | 1169660 | 2.3 |

| AFUB_010690 | AFUA_1G11260 | B0XQP5 | Uncharacterized protein | No | 0.91 | 56.70 | 97 | 10.186 | 1167077 | 1.0 |

| AFUB_002360 | AFUA_1G01980 | B0XRG2 | IgE binding protein, putative | Yes | 0.51 | 12.30 | 179 | 18.514 | 1161590 | 1.7 |

| AFUB_047560 | AFUA_3G00840 | B0XX33 | FAD-dependent oxygenase, putative | No | 0.59 | 17.60 | 507 | 55.026 | 921023 | 5.7 |

| AFUB_045140 | AFUA_3G03080 | B0Y002 | Endo-1,3(4)-beta-glucanase, putative | No | 0.90 | 21.40 | 285 | 31.087 | 869887 | 3.0 |

| AFUB_043810 | AFUA_3G04160 | B0XZB5 | Ser/Thr protein phosphatase family | Yes | 0.51 | 14.40 | 626 | 71.262 | 860230 | 4.3 |

| AFUB_010920 | AFUA_1G11490 | B0XQR8 | Endopolyphosphatase | Yes | 0.78 | 3.40 | 668 | 76.206 | 846930 | 2.7 |

| AFUB_020900 | AFUA_2G03830 | B0XUQ5 | Allergen Asp F4 | Yes | 0.50 | 25.20 | 322 | 34.093 | 784443 | 2.7 |

| AFUB_090580 | AFUA_7G05015 | B0YCL1 | Glyoxylase family protein, putative | Yes | 0.56 | 14.70 | 225 | 25.273 | 746237 | 2.7 |

| AFUB_061840 | AFUA_5G14150 | B0Y2H6 | Lipase, putative | No | 0.63 | 4.00 | 470 | 51.907 | 731363 | 1.0 |

| AFUB_083670 | AFUA_8G03905 | B0YA75 | Uncharacterized protein | Yes | 0.57 | 9.60 | 415 | 45.097 | 689597 | 1.7 |

| AFUB_019400 | AFUA_2G02310 | B0XTX2 | Cortical patch protein SUR7, putative | Yes | 0.82 | 6.70 | 239 | 26.609 | 670723 | 1.0 |

| AFUB_051770 | AFUA_5G03260 | B0Y2S3 | Endosomal cargo receptor (Erp3), putative | No | 0.81 | 31.50 | 241 | 27.159 | 641977 | 2.7 |

| AFUB_009000 | AFUA_1G09550 | B0XQ77 | Dynein light chain (Tctex1), putative | Yes | 0.53 | 21.70 | 143 | 15.325 | 639187 | 2.0 |

| AFUB_010900 | AFUA_1G11470 | B0XQR6 | Endosomal cargo receptor (P24), putative | Yes | 0.78 | 27.10 | 218 | 25.056 | 590885 | 2.0 |

| AFUB_069760 | AFUA_4G12850 | B0Y4P0 | Calnexin | No | 0.54 | 25.00 | 563 | 61.853 | 576790 | 4.7 |

| AFUB_097340 | AFUA_6G00160 | B0YDZ9 | Ser/Thr protein phosphatase family protein | Yes | 0.73 | 23.90 | 666 | 75.547 | 565267 | 4.7 |

| AFUB_038220 | AFUA_3G10910 | B0XXQ4 | Glutaminase, putative | Yes | 0.65 | 17.90 | 834 | 92.757 | 548343 | 6.0 |

| AFUB_080680 | AFUA_8G07120 | B0Y9D8 | Beta-1,6-glucanase, putative | No | 0.55 | 23.60 | 488 | 51.430 | 533200 | 2.7 |

| AFUB_024700 | AFUA_2G08790 | B0XRS8 | Putative metallocarboxypeptidase ecm14 | Yes | 0.95 | 6.70 | 586 | 66.068 | 528503 | 2.3 |

| AFUB_034540 | AFUA_3G14680 | B0XZV8 | Lysophospholipase 3 | No | 0.81 | 14.00 | 630 | 67.416 | 525853 | 4.3 |

| AFUB_028320 | AFUA_2G12680 | B0XSZ4 | Uncharacterized protein | No | 0.84 | 14.10 | 185 | 19.585 | 504547 | 2.0 |

| AFUB_017890 | AFUA_2G00810 | B0XT37 | Purine nucleoside permease, putative | No | 0.83 | 9.90 | 403 | 43.329 | 465497 | 1.7 |

| AFUB_015760 | AFUA_1G16420 | B0XNV1 | GPI anchored protein, putative | No | 0.58 | 3.10 | 523 | 58.528 | 379147 | 1.0 |

| AFUB_092390 | AFUA_7G06810 | B0YBD2 | L-amino acid oxidase LaoA | No | 0.65 | 10.20 | 697 | 78.612 | 352340 | 3.0 |

| AFUB_056510 | AFUA_5G08970 | B0Y449 | Oligosaccharyl transferase subunit (beta), putative | Yes | 0.94 | 16.90 | 462 | 51.642 | 331680 | 2.3 |

| AFUB_061470 | AFUA_5G13730 | B0Y269 | NlpC/P60-like cell-wall peptidase, putative | Yes | 0.81 | 12.30 | 359 | 38.763 | 323073 | 2.3 |

| AFUB_100370 | AFUA_4G02780 | B0YEU1 | Toxin biosynthesis peroxidase, putative | No | 0.83 | 11.10 | 324 | 36.980 | 311520 | 0.7 |

| AFUB_014800 | AFUA_1G15250 | B0XN71 | Autophagy protein Atg27, putative | Yes | 0.76 | 8.40 | 333 | 37.377 | 307030 | 1.0 |

| AFUB_101570 | AFUA_4G01070 | B0YF50 | Acid phosphatase, putative | No | 0.74 | 11.90 | 293 | 30.459 | 304120 | 1.7 |

| AFUB_021510 | AFUA_2G04480 | B0XV35 | Xylosidase/arabinosidase, putative | No | 0.81 | 19.10 | 371 | 40.803 | 289893 | 2.0 |

| AFUB_030040 | AFUA_2G14420 | B0XU21 | Cutinase | No | 0.66 | 7.90 | 366 | 35.677 | 269740 | 0.7 |

| lap1 | lap1 | B0YED6 | Leucine aminopeptidase 1 | No | 0.84 | 13.90 | 388 | 43.127 | 267110 | 2.0 |

| AFUB_085200 | AFUA_8G01410 | B0YAM7 | Class V chitinase ChiB1 | Yes | 0.76 | 9.00 | 433 | 47.622 | 245500 | 0.7 |

| AFUB_027870 | AFUA_2G12180 | B0XSP1 | Lectin family integral membrane protein, putative | No | 0.72 | 16.20 | 327 | 36.197 | 244833 | 2.0 |

| AFUB_052800 | AFUA_5G04280 | B0Y335 | Uncharacterized protein | Yes | 0.83 | 16.70 | 245 | 26.115 | 229443 | 2.3 |

| AFUB_034660 | AFUA_3G14570 | B0XZX0 | Histidine acid phosphatase, putative | No | 0.74 | 7.10 | 462 | 51.295 | 213797 | 2.0 |

| btgE | btgE | B0Y9Q9 | Probable beta-glucosidase btgE | No | 0.49 | 5.80 | 565 | 58.147 | 200803 | 1.3 |

| AFUB_052440 | AFUA_5G03940 | B0Y2Z9 | Mutanase | No | 0.89 | 15.00 | 446 | 49.981 | 190812 | 1.3 |

| AFUB_045510 | 0 | B0Y037 | Uncharacterized protein | No | 0.68 | 23.60 | 229 | 23.817 | 186013 | 1.0 |

| AFUB_089550 | AFUA_7G04020 | B0YCB0 | Lipase, putative | No | 0.64 | 5.00 | 463 | 49.258 | 182750 | 0.7 |

| AFUB_003170 | AFUA_1G02780 | B0XML5 | L-asparaginase | No | 0.79 | 4.70 | 379 | 39.784 | 181210 | 1.0 |

| AFUB_065820 | AFUA_4G08720 | B0Y665 | Lysophospholipase 1 | No | 0.78 | 4.60 | 633 | 68.143 | 179210 | 2.0 |

| AFUB_032470 | AFUA_2G16800 | B0XVA9 | Lectin family integral membrane protein, putative | Yes | 0.69 | 17.40 | 328 | 36.070 | 167933 | 2.0 |

| AFUB_036000 | AFUA_3G13200 | B0XWI1 | 1,3-beta-glucanosyltransferase | No | 0.72 | 4.10 | 460 | 49.933 | 135095 | 1.0 |

| AFUB_039870 | AFUA_3G09250 | B0XY72 | Cell wall glucanase, putative | Yes | 0.93 | 6.30 | 363 | 40.590 | 107533 | 1.0 |

| AFUB_100920 | AFUA_4G00390 | B0YEY4 | Glycosyl hydrolase, putative | No | 0.66 | 7.80 | 883 | 98.929 | 93101 | 3.3 |

| AFUB_020340 | AFUA_2G03270 | B0XUD4 | Glycosyl hydrolase, putative | No | 0.80 | 2.10 | 620 | 69.305 | 84869 | 1.0 |

| AFUB_052020 | AFUA_5G03500 | B0Y2U6 | Alpha glucosidase II, alpha subunit, putative | No | 0.77 | 10.50 | 967 | 109.650 | 80189 | 2.0 |

| AFUB_030100 | AFUA_2G14480 | B0XU27 | Oxidoreductase, FAD-binding, putative | No | 0.89 | 4.20 | 473 | 50.494 | 68197 | 0.7 |

| AFUB_067180 | AFUA_4G10070 | B0Y6J5 | Alpha-1,2-Mannosidase | Yes | 0.64 | 1.60 | 641 | 73.606 | 39384 | 1.0 |

| AFUB_046050 | AFUA_3G02280 | B0Y0F9 | Alpha,alpha-trehalose glucohydrolase TreA/Ath1 | No | 0.81 | 1.20 | 1072 | 117.000 | 29926 | 0.7 |

| B | Signal-peptide-containing proteins extracted with 2h in formic acid from 10d old conidia, present in I115S/I146G and absent in parental strain |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene ID | BLAST Af293 | UniProt | Description | Present in I115S/I146G, absent in parental 30d | Score of SignalP | Unique sequence coverage (%) | Protein length | MW (kDa) | Mean iBAQ I115S/I146G 10d | Mean Unique Peptides I115S/I146G 10d |

| AFUB_046180 | AFUA_3G02190 | B0Y0H2 | Uncharacterized protein | No | 0.87 | 30.30 | 297 | 33.610 | 7462267 | 8.7 |

| AFUB_059890 | AFUA_5G12260 | B0Y1D4 | Disulfide isomerase (TigA), putative | Yes | 0.87 | 54.60 | 368 | 40.253 | 4837900 | 14.0 |

| AFUB_031800 | AFUA_2G16120 | B0XUX8 | Translocon-associated protein, alpha subunit, putative | Yes | 0.84 | 42.10 | 261 | 28.158 | 4398400 | 4.0 |

| AFUB_070080 | AFUA_4G13190 | B0Y4S2 | Endosomal cargo receptor (Erv25), putative | Yes | 0.93 | 33.80 | 266 | 30.039 | 3296267 | 5.3 |

| AFUB_038670 | AFUA_3G10490 | B0XXV2 | DNA damage response protein (Dap1), putative | Yes | 0.69 | 37.40 | 155 | 17.221 | 3025733 | 4.7 |

| AFUB_059210 | AFUA_5G11640 | B0Y110 | Secretory pathway protein Ssp120, putative | Yes | 0.64 | 36.00 | 203 | 23.277 | 2806833 | 4.7 |

| AFUB_045170 | AFUA_3G03060 | B0Y004 | Cell wall protein phiA | No | 0.58 | 37.80 | 185 | 19.380 | 2437133 | 3.0 |

| AFUB_038220 | AFUA_3G10910 | B0XXQ4 | Glutaminase, putative | Yes | 0.65 | 17.90 | 834 | 92.757 | 2213600 | 12.3 |

| AFUB_087640 | AFUA_7G01060 | B0YBS2 | Cysteine-rich secreted protein | No | 0.81 | 22.40 | 343 | 36.860 | 2169400 | 3.7 |

| AFUB_072730 | AFUA_6G06800 | B0Y766 | Probable carboxypeptidase | Yes | 0.58 | 25.90 | 440 | 46.377 | 1894433 | 3.7 |

| AFUB_071360 | AFUA_4G14205 | B0Y546 | Uncharacterized protein | No | 0.88 | 8.00 | 138 | 14.405 | 1737567 | 1.0 |

| AFUB_046170 | AFUA_3G02200 | B0Y0H1 | Uncharacterized protein | No | 0.89 | 17.20 | 192 | 20.681 | 1636300 | 2.7 |

| AFUB_060890 | AFUA_5G13180 | B0Y1U6 | Agmatinase, putative | Yes | 0.68 | 28.40 | 391 | 42.179 | 1631667 | 3.3 |

| AFUB_010900 | AFUA_1G11470 | B0XQR6 | Endosomal cargo receptor (P24), putative | Yes | 0.78 | 27.10 | 218 | 25.056 | 1595133 | 4.7 |

| AFUB_097340 | AFUA_6G00160 | B0YDZ9 | Ser/Thr protein phosphatase family protein | Yes | 0.73 | 23.90 | 666 | 75.547 | 1560833 | 10.0 |

| AFUB_091030 | AFUA_7G05450 | B0YCQ5 | SUN domain protein (Uth1), putative | Yes | 0.50 | 23.20 | 414 | 43.504 | 1474467 | 5.7 |

| AFUB_099880 | AFUA_4G03240 | B0YEP2 | Cell wall serine-threonine-rich galactomannoprotein Mp1 | No | 0.83 | 33.50 | 284 | 27.361 | 1119097 | 3.7 |

| AFUB_056510 | AFUA_5G08970 | B0Y449 | Oligosaccharyl transferase subunit (beta), putative | Yes | 0.94 | 16.90 | 462 | 51.642 | 994130 | 4.3 |

| AFUB_009000 | AFUA_1G09550 | B0XQ77 | Dynein light chain (Tctex1), putative | Yes | 0.53 | 21.70 | 143 | 15.325 | 865887 | 2.0 |

| AFUB_086950 | AFUA_7G00370 | B0YBK6 | Uncharacterized protein | Yes | 0.78 | 29.30 | 198 | 21.384 | 790777 | 1.0 |

| AFUB_020580 | AFUA_2G03510 | B0XUM7 | Carboxypeptidase | No | 0.84 | 23.00 | 534 | 59.725 | 774907 | 2.7 |

| bglF | bglF | B0Y7Q8 | Probable beta-glucosidase F | No | 0.79 | 42.70 | 869 | 93.059 | 764553 | 7.3 |

| AFUB_083670 | AFUA_8G03905 | B0YA75 | Uncharacterized protein | Yes | 0.57 | 9.60 | 415 | 45.097 | 761603 | 3.0 |

| AFUB_022820 | AFUA_2G05790 | B0XVU7 | Oligosaccharyl transferase subunit (alpha), putative | No | 0.78 | 20.80 | 504 | 56.149 | 717993 | 4.3 |

| AFUB_090580 | AFUA_7G05015 | B0YCL1 | Glyoxylase family protein, putative | Yes | 0.56 | 14.70 | 225 | 25.273 | 676803 | 1.7 |

| AFUB_024920 | AFUA_2G09030 | B0XRV0 | Dipeptidyl-peptidase 5 | No | 0.74 | 16.00 | 721 | 79.742 | 589393 | 7.3 |

| AFUB_032470 | AFUA_2G16800 | B0XVA9 | Lectin family integral membrane protein, putative | Yes | 0.69 | 17.40 | 328 | 36.070 | 540273 | 3.7 |

| AFUB_002360 | AFUA_1G01980 | B0XRG2 | IgE binding protein, putative | Yes | 0.51 | 12.30 | 179 | 18.514 | 538723 | 1.3 |

| AFUB_019400 | AFUA_2G02310 | B0XTX2 | Cortical patch protein SUR7, putative | Yes | 0.82 | 6.70 | 239 | 26.609 | 516630 | 1.0 |

| AFUB_039870 | AFUA_3G09250 | B0XY72 | Cell wall glucanase, putative | Yes | 0.93 | 6.30 | 363 | 40.590 | 514650 | 2.0 |

| AFUB_063770 | AFUA_4G06700 | B0Y5L1 | GPI anchored cell wall protein, putative | No | 0.81 | 5.90 | 221 | 22.620 | 485620 | 1.7 |

| AFUB_043810 | AFUA_3G04160 | B0XZB5 | Ser/Thr protein phosphatase family | Yes | 0.51 | 14.40 | 626 | 71.262 | 377700 | 1.3 |

| AFUB_029830 | AFUA_2G14210 | B0XTT1 | Mitochondrial dihydroxy acid dehydratase, putative | No | 0.51 | 12.60 | 642 | 68.256 | 371027 | 5.0 |

| AFUB_098310 | AFUA_4G04690 | B0YE87 | Uncharacterized protein | No | 0.73 | 18.70 | 209 | 22.594 | 333057 | 1.0 |

| AFUB_025060 | AFUA_2G09180 | B0XRW4 | Coatomer subunit zeta, putativ | No | 0.48 | 13.90 | 201 | 21.929 | 332405 | 0.7 |

| AFUB_024700 | AFUA_2G08790 | B0XRS8 | Putative metallocarboxypeptidase ecm14 | Yes | 0.95 | 6.70 | 586 | 66.068 | 308810 | 0.7 |

| AFUB_014610 | AFUA_1G15050 | B0XN52 | Hsp70 family chaperone Lhs1/Orp150, putative | No | 0.58 | 10.00 | 997 | 108.750 | 300040 | 5.3 |

| AFUB_010920 | AFUA_1G11490 | B0XQR8 | Endopolyphosphatase | Yes | 0.78 | 3.40 | 668 | 76.206 | 295473 | 2.0 |

| AFUB_052800 | AFUA_5G04280 | B0Y335 | Uncharacterized protein | Yes | 0.83 | 16.70 | 245 | 26.115 | 293027 | 2.3 |

| AFUB_023360 | AFUA_2G06280 | B0XW28 | Oligosaccharyl transferase subunit (Gamma), putative | No | 0.69 | 7.10 | 325 | 35.939 | 260640 | 0.7 |

| AFUB_056810 | AFUA_5G09270 | B0Y479 | Uncharacterized protein | No | 0.87 | 6.20 | 952 | 103.550 | 223923 | 4.0 |

| AFUB_070260 | AFUA_4G13340 | B0Y4T7 | DUF907 domain protein | No | 0.93 | 3.90 | 721 | 78.538 | 178277 | 2.0 |

| AFUB_061470 | AFUA_5G13730 | B0Y269 | NlpC/P60-like cell-wall peptidase, putative | Yes | 0.81 | 12.30 | 359 | 38.763 | 169897 | 1.3 |

| AFUB_085200 | AFUA_8G01410 | B0YAM7 | Class V chitinase ChiB1 | Yes | 0.76 | 9.00 | 433 | 47.622 | 159987 | 1.0 |

| AFUB_074470 | AFUA_6G08510 | B0Y7N9 | Cell wall glucanase, putative | No | 0.79 | 10.30 | 436 | 45.674 | 152803 | 1.0 |

| AFUB_005670 | AFUA_1G05320 | B0XP24 | Disulfide isomerase, putative | No | 0.87 | 7.50 | 478 | 51.299 | 146322 | 2.3 |

| AFUB_020900 | AFUA_2G03830 | B0XUQ5 | Allergen Asp F4 | Yes | 0.50 | 25.20 | 322 | 34.093 | 138837 | 1.3 |

| AFUB_061010 | AFUA_5G13300 | B0Y1V8 | Aspartic protease pep1 | No | 0.69 | 33.20 | 395 | 41.613 | 133245 | 0.7 |

| AFUB_014800 | AFUA_1G15250 | B0XN71 | Autophagy protein Atg27, putative | Yes | 0.76 | 8.40 | 333 | 37.377 | 121900 | 1.3 |

| AFUB_079260 | AFUA_1G01540 | B0Y912 | Endonuclease/exonuclease/phosphatase family protein | No | 0.59 | 9.30 | 439 | 47.788 | 100628 | 1.0 |

| AFUB_015530 | AFUA_1G16190 | B0XNL0 | Extracellular cell wall glucanase Crf1/allergen Asp F9 | Yes | 0.77 | 22.50 | 395 | 40.269 | 84105 | 1.0 |

| AFUB_076030 | AFUA_6G09980 | B0Y842 | Patched sphingolipid transporter (Ncr1), putative | Yes | 0.66 | 4.60 | 1273 | 140.400 | 81393 | 2.0 |

| AFUB_035150 | AFUA_3G14060 | B0Y088 | Palmitoyl-protein thioesterase | No | 0.59 | 5.40 | 333 | 37.495 | 80447 | 1.0 |

| AFUB_024270 | AFUA_2G08300 | B0XWB9 | DnaJ domain protein, putative | No | 0.94 | 4.20 | 427 | 48.528 | 75414 | 0.7 |

| AFUB_026370 | AFUA_2G10590 | B0XS92 | Disulfide isomerase, putative | No | 0.88 | 4.70 | 737 | 82.846 | 58610 | 0.7 |

| AFUB_067180 | AFUA_4G10070 | B0Y6J5 | Alpha-1,2-Mannosidase | Yes | 0.64 | 1.60 | 641 | 73.606 | 57328 | 1.0 |

| C | Signal-peptide-containing proteins extracted with 2h in formic acid from 10d and 30d old conidia, present in I115S/I146G and absent in parental strain |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene ID | Blast Af293 | UniProt | Description | Present in 115146, absent in parental of 30d | Score of SignalP | Unique sequene coverage (%) | Protein length | MW (kDa) | Mean iBAQ I115S/I146G 10d | Mean Unique Peptides I115S/I146G 10d |

| AFUB_059890 | AFUA_5G12260 | B0Y1D4 | Disulfide isomerase (TigA), putative | Yes | 0.87 | 54.60 | 368 | 40.253 | 4837900 | 14.0 |

| AFUB_031800 | AFUA_2G16120 | B0XUX8 | Translocon-associated protein, alpha subunit, putative | Yes | 0.84 | 42.10 | 261 | 28.158 | 4398400 | 4.0 |

| AFUB_070080 | AFUA_4G13190 | B0Y4S2 | Endosomal cargo receptor (Erv25), putative | Yes | 0.93 | 33.80 | 266 | 30.039 | 3296267 | 5.3 |

| AFUB_038670 | AFUA_3G10490 | B0XXV2 | DNA damage response protein (Dap1), putative | Yes | 0.69 | 37.40 | 155 | 17.221 | 3025733 | 4.7 |

| AFUB_059210 | AFUA_5G11640 | B0Y110 | Secretory pathway protein Ssp120, putative | Yes | 0.64 | 36.00 | 203 | 23.277 | 2806833 | 4.7 |

| AFUB_038220 | AFUA_3G10910 | B0XXQ4 | Glutaminase, putative | Yes | 0.65 | 17.90 | 834 | 92.757 | 2213600 | 12.3 |

| AFUB_072730 | AFUA_6G06800 | B0Y766 | Probable carboxypeptidase | Yes | 0.58 | 25.90 | 440 | 46.377 | 1894433 | 3.7 |

| AFUB_060890 | AFUA_5G13180 | B0Y1U6 | Agmatinase, putative | Yes | 0.68 | 28.40 | 391 | 42.179 | 1631667 | 3.3 |

| AFUB_010900 | AFUA_1G11470 | B0XQR6 | Endosomal cargo receptor (P24), putative | Yes | 0.78 | 27.10 | 218 | 25.056 | 1595133 | 4.7 |

| AFUB_097340 | AFUA_6G00160 | B0YDZ9 | Ser/Thr protein phosphatase family protein | Yes | 0.73 | 23.90 | 666 | 75.547 | 1560833 | 10.0 |

| AFUB_091030 | AFUA_7G05450 | B0YCQ5 | SUN domain protein (Uth1), putative | Yes | 0.50 | 23.20 | 414 | 43.504 | 1474467 | 5.7 |

| AFUB_056510 | AFUA_5G08970 | B0Y449 | Oligosaccharyl transferase subunit (beta), putative | Yes | 0.94 | 16.90 | 462 | 51.642 | 994130 | 4.3 |

| AFUB_009000 | AFUA_1G09550 | B0XQ77 | Dynein light chain (Tctex1), putative | Yes | 0.53 | 21.70 | 143 | 15.325 | 865887 | 2.0 |

| AFUB_086950 | AFUA_7G00370 | B0YBK6 | Uncharacterized protein | Yes | 0.78 | 29.30 | 198 | 21.384 | 790777 | 1.0 |

| AFUB_083670 | AFUA_8G03905 | B0YA75 | Uncharacterized protein | Yes | 0.57 | 9.60 | 415 | 45.097 | 761603 | 3.0 |

| AFUB_090580 | AFUA_7G05015 | B0YCL1 | Glyoxylase family protein, putative | Yes | 0.56 | 14.70 | 225 | 25.273 | 676803 | 1.7 |

| AFUB_032470 | AFUA_2G16800 | B0XVA9 | Lectin family integral membrane protein, putative | Yes | 0.69 | 17.40 | 328 | 36.070 | 540273 | 3.7 |

| AFUB_002360 | AFUA_1G01980 | B0XRG2 | IgE binding protein, putative | Yes | 0.51 | 12.30 | 179 | 18.514 | 538723 | 1.3 |

| AFUB_019400 | AFUA_2G02310 | B0XTX2 | Cortical patch protein SUR7, putative | Yes | 0.82 | 6.70 | 239 | 26.609 | 516630 | 1.0 |

| AFUB_039870 | AFUA_3G09250 | B0XY72 | Cell wall glucanase, putative | Yes | 0.93 | 6.30 | 363 | 40.590 | 514650 | 2.0 |

| AFUB_043810 | AFUA_3G04160 | B0XZB5 | Ser/Thr protein phosphatase family | Yes | 0.51 | 14.40 | 626 | 71.262 | 377700 | 1.3 |

| AFUB_024700 | AFUA_2G08790 | B0XRS8 | Putative metallocarboxypeptidase ecm14 | Yes | 0.95 | 6.70 | 586 | 66.068 | 308810 | 0.7 |

| AFUB_010920 | AFUA_1G11490 | B0XQR8 | Endopolyphosphatase | Yes | 0.78 | 3.40 | 668 | 76.206 | 295473 | 2.0 |

| AFUB_052800 | AFUA_5G04280 | B0Y335 | Uncharacterized protein | Yes | 0.83 | 16.70 | 245 | 26.115 | 293027 | 2.3 |

| AFUB_061470 | AFUA_5G13730 | B0Y269 | NlpC/P60-like cell-wall peptidase, putative | Yes | 0.81 | 12.30 | 359 | 38.763 | 169897 | 1.3 |

| AFUB_085200 | AFUA_8G01410 | B0YAM7 | Class V chitinase ChiB1 | Yes | 0.76 | 9.00 | 433 | 47.622 | 159987 | 1.0 |

| AFUB_020900 | AFUA_2G03830 | B0XUQ5 | Allergen Asp F4 | Yes | 0.50 | 25.20 | 322 | 34.093 | 138837 | 1.3 |

| AFUB_014800 | AFUA_1G15250 | B0XN71 | Autophagy protein Atg27, putative | Yes | 0.76 | 8.40 | 333 | 37.377 | 121900 | 1.3 |

| AFUB_015530 | AFUA_1G16190 | B0XNL0 | Extracellular cell wall glucanase Crf1/allergen Asp F9 | Yes | 0.77 | 22.50 | 395 | 40.269 | 84105 | 1.0 |

| AFUB_076030 | AFUA_6G09980 | B0Y842 | Patched sphingolipid transporter (Ncr1), putative | Yes | 0.66 | 4.60 | 1273 | 140.400 | 81393 | 2.0 |

| AFUB_067180 | AFUA_4G10070 | B0Y6J5 | Alpha-1,2-Mannosidase | Yes | 0.64 | 1.60 | 641 | 73.606 | 57328 | 1.0 |

In conclusion, the results obtained with the conidial mutants were very reminiscent of the ones obtained in vitro with mutated recombinant RodA analyzed by ThT fluorescence assays in solution and AFM on a solid support. The rodlets of the mutants were organized differently when amino acids from both amyloidogenic regions were simultaneously mutated and/or when the protein carried a mutation that significantly extended the lag phase for rodlet formation. Although rodlets were still formed, their structural maturation required a longer time and was incomplete, leaving the conidia hydrophilic and with amorphous materials covering their surfaces.

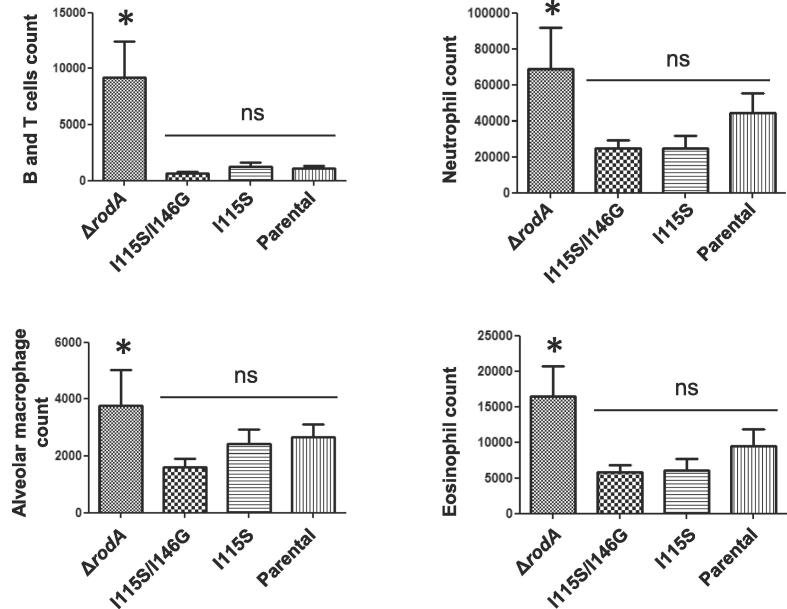

2.4. Impact of point mutations on the immune response towards hydrophobins

We have reported earlier that the surface rodlet layer masks A. fumigatus conidial recognition by the host immune cells, whereas the conidial morphotypes devoid of a rodlet layer (i.e., ΔrodA mutant conidia or conidia after HF treatment) activate innate as well as adaptive immune responses (Aimanianda et al., 2009). These results prompted us to investigate if the disorganization of the rodlet structure on the conidial surface as a consequence of point mutations in the RODA gene would lead to the activation of immune cells by mutant conidia. Short and long term exposures of conidia from the RodA mutants and their parental strain were investigated. Intracheal inoculation of 5x107 conidia into 57/Bl6 mice resulted in the immediate recruitment of cells (neutrophils, B and T cells and eosinophils), 6 h after the inoculation (Fig. 8). The most important recruitment was observed with the ΔrodA mutant and was similar in mice infected with the ΔrodA and the quadruple cysteine mutants (Fig. S11). Interestingly, the cellular recruitment with the RodA I115S/I146G mutant was similar to the parental strain, suggesting that the presence of disorganized rodlets on the conidial surface is sufficient to immunosilence the conidia. After 24 h, no difference in the GM concentration was found between all RodA mutants and the parental strain in mice lungs (data not shown). This result was in agreement with previous results (Thau et al., 1994. Valsecchi et al., 2017) indicating that rodlets are not a virulence factor for A. fumigatus.

Fig. 8.

Recruitment of cells in the lungs of C57/Bl6 mice after inhalation of conidia of the single RodA I115S, double RodA I115S/I146G, ΔrodA mutant and the parental strain Ku80. Total number of cells were counted in the BALs (counts from >6 mice per experiment, 2 experiments) 6 h after conidial inoculation and were expressed as average with SEM. No significative differences were observed between the two mutants and the parental strain, while more cells were significantly recruited in the lungs of mice infected with the ΔrodA mutant.

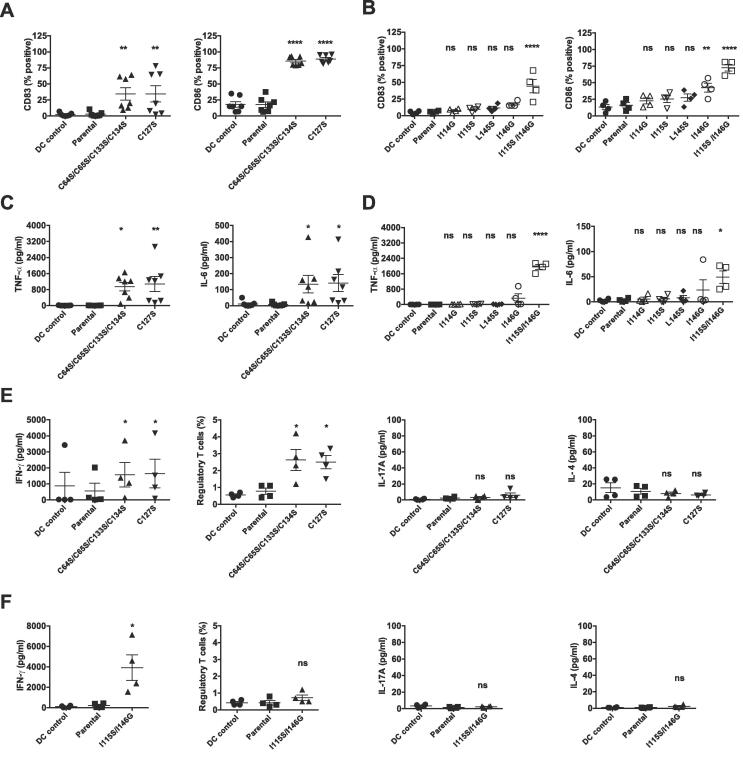

Long-term exposure was investigated with fixed conidia and human dendritic cells (DC) for 2 reasons: (i) DCs are major players in deciding the fate of the immune response and (ii) the use of fixed conidia was necessary since unfixed conidia would germinate and thus interfere with the specific immune response towards intact conidia of the parental and mutant strains. A. fumigatus conidia bearing mutations in the cysteine residue(s) [both single C127S or quadruple (C64S/C65S/C133S/C134S)] or the double I115S/I146G mutant conidia were indeed immunogenic in our experimental conditions. A significantly higher expression of CD83, a terminal maturation marker of DC, and of the co-stimulatory molecule CD86 was seen when DCs were exposed to cysteine (both single and quadruple) or I115S/I146G mutant conidia (Fig. 9A). Other DC maturation markers such as CD40, CD86 and HLA-DR were also enhanced by these mutant conidia (data not shown). In contrast, conidia with single mutations in the C4-C5 or C7-C8 loop regions (i.e., I114G, I115S, L145S, I146G point-mutant conidia) did not induce a DC response (Fig. 9B). Moreover, conidia with a cysteine mutation (both single or quadruple) or the double I115S/I146G mutation induced significantly higher quantities of the DC cytokines TNFα and IL6 (Fig. 9C,D). Untreated immature DCs produced only minimal quantities of cytokines like the parental or the single point mutated I114G, I115S or L145S conidia, while the I146G mutant conidia induced moderate amounts of these cytokines.

Fig. 9.

Conidia of single and quadruple cysteine mutants and the double RodA I115S/I146G mutant activate the human immune response. A-B: Induction of the dendritic cells (DC) maturation. C-D: Production of cytokines by DC. E-F: Polarization of T cell response. As other single point mutants did not alter either DC phenotype or cytokines, they were not tested for T cell response. Note that (i) the cysteine mutants also polarize the Treg response and that (ii) the I146G mutant slightly activates the DC response.

CD4+ T cell polarization mediated by A. fumigatus RODA point-mutant conidia matured DCs was also investigated. Quantification of secretion of T cell cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-17A) or intracellular staining of the transcription factor FoxP3 revealed that cysteine mutant conidia [i.e., both C127S and C64S/C65S/C133S/C134S)] or harboring the double mutation (I115S/I146G) promoted distinct T cell responses. Single and quadruple cysteine mutant conidia-matured-DCs polarized predominantly CD4+CD25+CD127- FoxP3+ Treg and IFN-γ (Th1) responses (Fig. 9E), whereas Th2 (IL-4) and Th17 (IL-17A) cytokines remained at basal levels (Fig. 9E). On the contrary, I115S/I146G double mutant conidia matured-DCs promoted only Th1 responses, while other T cell subsets, including Tregs, were not altered (Fig. 9F). Hence, A. fumigatus conidia that lack disulfide bridges in RodA or with the double mutation (I115S/I146G) in the amyloidogenic regions are both immunogenic but promoted distinct T cell responses.

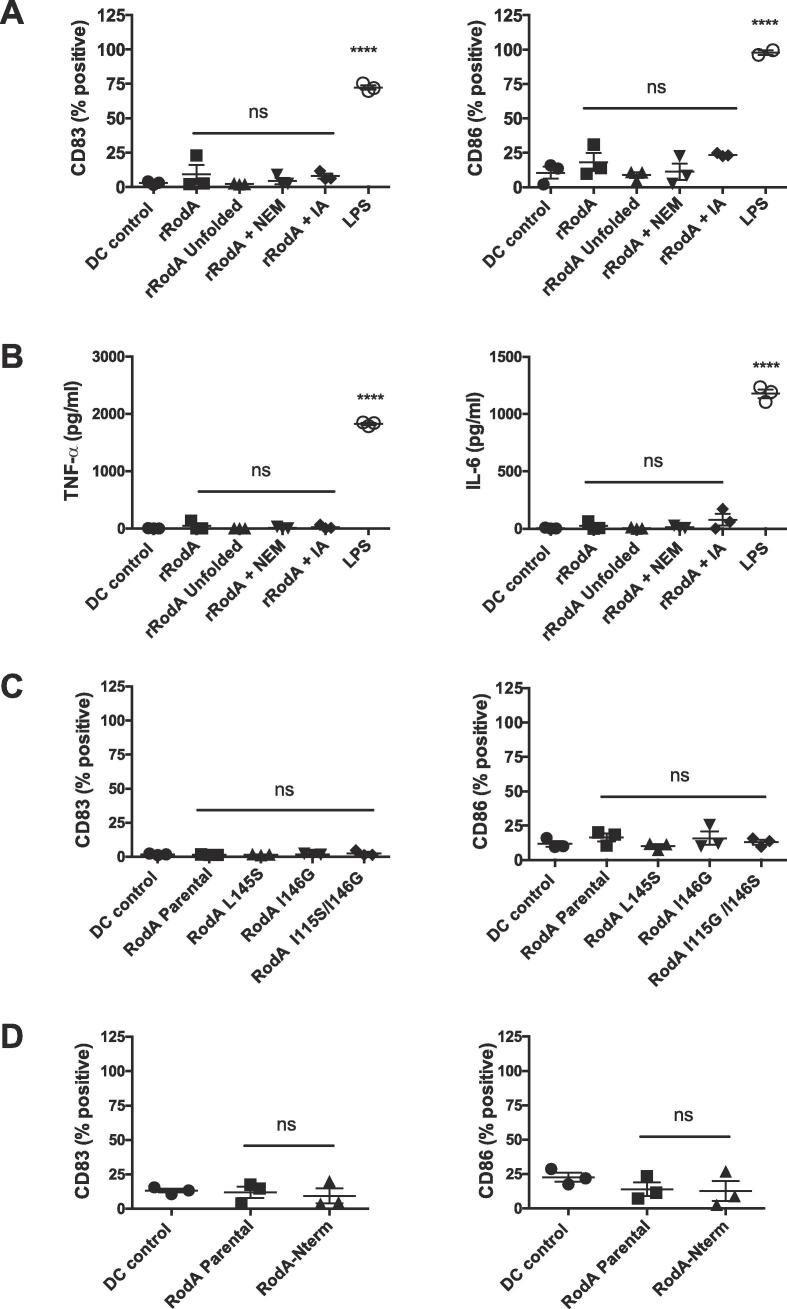

Earlier, we had shown that RodA extracted from the conidial surface did not stimulate an immune response of the host (Aimanianda et al., 2009). Recombinant RodA, whether folded or unfolded, with non-reduced or reduced and blocked cysteines with N-ethyl maleimide (NEM) or iodoacetamide (IA), did not modify either the DC phenotype or the production of cytokines (Fig. 10A,B). Similar results were obtained for conidia-extracted RodA harboring single or double mutations in their C4-C5 or C7-C8 regions or lacking the forty N-terminal amino acids (Fig. 10C,D). These observations clearly indicated that the DC activation and maturation induced by the double I115S/I146G mutant conidia was only due to the emergence of different pathogen-associated molecular patterns on the surface of conidia, concomitant with the delayed formation of the rodlets and hence with the disorganization of the outer cell wall layer.

Fig. 10.

Lack of DC activation by the reduced (A,B) or mutated RodA protein (C,D). A-B: Unfolded rRodA, with or without reduced and blocked Cys residues with N-ethyl maleimide (NEM) or iodoacetamide (IA) do not activate dendritic cells (A) and do not induce cytokine production (B). C-D: RodA extracted from conidia of mutants L145S, I146G, I115G/I146S (C) or lacking the N terminal region (RodA-Nterm) (D), are immunologically inert as parental RodA. LPS is used as a control.

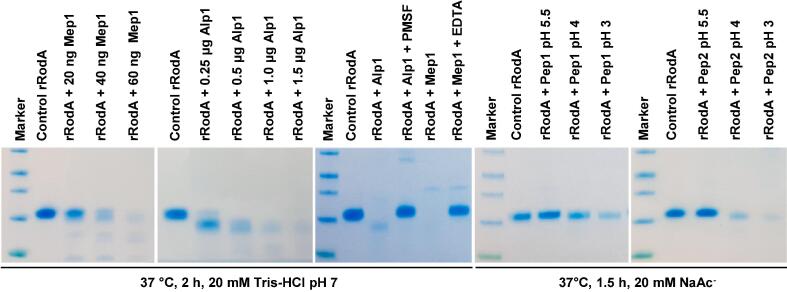

2.5. Disassembly of the rodlet structure during germination

In nature, the activation of the immune response is associated with the loss of the rodlet layer, which occurs during conidial germination (Aimanianda et al., 2009). However, the mechanism of disintegration of the rodlet layer during germination has not been previously investigated. Disassembly of the rodlet structure is a progressive event during conidial swelling. Complete removal of the rodlet structure from the conidial surface occurs in about 5–6 h from the commencement of the germination process (data not shown).When recombinant or native RodA proteins were incubated with the ethanol precipitated protein mixture from the supernatant of germinating conidia, RodA was degraded (Fig. S12). RodA degradation was blocked by heat inactivation (data not shown), suggesting that degradation was due to proteases. Incubation of the native or recombinant RodA with the major proteases identified in A. fumigatus (Jaton-Ogay et al., 1994, Reichard et al., 1997, Sriranganadane et al., 2010) showed that the later proteases were able to degrade rRodA (Fig. 11). This lack of specificity and the redundancy of the proteases able to degrade rRodA explained why neither the degradation of RodA nor conidial germination were affected in the double Δalp1/Δmep1(Jaton-Ogay et al., 1994) or quadruple Δpep1/Δpep2 /ΔctsD/ΔopsB mutants that was constructed in this work (data not shown).

Fig. 11.

Degradation of rRodA by the major proteases identified in A. fumigatus, Alp1, Mep1, Pep1 and Pep2. rRodA (4 µg) was mixed with different proteases (1 µg or less as indicated) in 30 µl of 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7 for Alp1 and Melp1 or sodium acetate pH 5.5, 4 or 3 for Pep1 and Pep2. Samples were taken after 1.5 h or 2 h of incubation at 37 °C. PMSF, EDTA or slightly acidic pH were used as inhibitors of Alp1Mep1 Pep1 and Pep2 respectively.

3. Discussion

3.1. The structure and assembly of A. fumigatus RodA into rodlets

Analysis of rRodA and conidial native RodA for understanding of the assembly of the rodlets has suggested that rodlet formation in A. fumigatus may be unusual in that the two amyloidogenic regions are likely to be involved in the formation of intermolecular β-sheet structures. In contrast in other fungi, only single amyloidogenic regions have been identified (Macindoe et al., 2012, Niu et al., 2017, Wang et al., 2004). Here, like earlier studies with the Neurospora crassa hydrophobin EAS (Kwan et al., 2006), we used solution NMR spectroscopy to determine the structure of the monomeric form. The RodA monomer in solution displays the β-barrel structure typical of hydrophobins and the surface of RodA exhibits a separation of charged and hydrophobic amino acid residues, which renders the protein amphipathic. Also, as for other hydrophobins, the amphiphilic nature of the RodA monomer likely plays an important role in localizing the protein at an interface and the flexibility of the amyloidogenic regions may be necessary to accommodate the structural changes required for multimerization and uniform covering of substrates. In the absence of crystals of hydrophobins in the assembled form, solid state NMR (ssNMR) has been used to probe the 3D structure of the EAS rodlets and confirmed that hydrophobin rodlets are composed of a β-sheet-rich structure with an altered protein fold compared to the monomer in solution (Morris et al., 2012). Similar ssNMR studies of RodA will likely reveal how the two amyloidogenic regions in the RodA rodlets contribute to the structure and packing of rodlets within the robust protein film.

Earlier studies have shown that an increase in pH, the presence of Ca2+, a low ionic strength, the polarity of the solvent, the high temperature, the presence or absence of an air:water interface, the presence of detergents, the protein concentration, specific nutriments and the physic-chemical nature of the surface are all environmental factors which can influence rodlet formation (Aimanianda et al., 2009, Cicatiello et al., 2017, Longobardi et al., 2012, Morris et al., 2011, Niu et al., 2017, Pham et al., 2016, Pham et al., 2018, Talbot et al., 1996, Talbot et al., 1993, Tanaka et al., 2017, Wang et al., 2004, Zykwinska et al., 2014a). The comparison of rodlet formation at the surface of the conidia of A. fumigatus and on an artificial hydrophobic surface like HOPG of wild-type or rRodA mutated proteins, has indicated that the environment influences the formation of the rodlet structure. For example, even though rRodA carrying mutations form rodlets that are similar to the wild type protein on the HOPG substrate, the rodlet structure and coverage on the conidial surface of the mutant looked altered on the more complex surface of the conidial cell wall. Similar observations have been reported for other hydrophobins like SC3 from Schizophyllum commune and Vmh2 from Pleurotus ostreatus that can also spontaneously self-assemble in aqueous solutions (Longobardi et al., 2012, Wosten et al., 1993, Zykwinska et al., 2014a). The presence of oligosaccharides facilitates the self-assembly in water of P. ostreatus Vmh2 and the width of the rodlet is influenced by the addition of cyclic 1,4-glucans (Armenante et al., 2010). The transition of Schizophyllum commune SC3 from a helical configuration to the stable β-rich amyloid conformation is promoted by the presence of soluble glucans (Scholtmeijer et al., 2009). In A. fumigatus, the role of the inner components of the conidial cell wall, which are located below the rodlet layer, such as α- and β-1,3-glucans, galactomannan or melanin, on the structure and anchoring of rodlets has not been investigated to date. An accurate definition of the events controlling the structural conversion of the A. fumigatus RodA protein into rodlets remains to be generated and should take into account the natural environment of the conidium. Moreover, the observation that there are different triggers for rodlet assembly in different hydrophobins likely reflects the fact that apart from the pattern of conserved disulfide bonds, which constrains the β-barrel core, the sequences and structures of the proteins are highly diverse (Ren et al., 2013).

In vitro studies, while very useful, can be limited by the homogeneous nature of the substrate and the inability to effectively probe the three-dimensional organization of the rodlet-containing layer. Moreover, the role of the cellular environment used in the heterologous host for the production of recombinant RodA protein has not been investigated. Even though A. fumigatus RodA protein has been produced for our study in E. coli and folded in vitro to obtain a protein that is folded like conidial RodA and is able to form rodlets, it has been previously shown that A. fumigatus RodA protein can be also produced in Pichia pastoris (Pedersen et al., 2011). The amount produced in P. pastoris was 200 to 300 mg/L to be compared with E. coli (∼2 mg/L). However, although it was verified that the recombinant RodA of A. fumigatus produced in Pichia was able to convert a hydrophilic substrate into a hydrophobic surface, the disulfide pairings, the ability of the recombinant proteins produced in P. pastoris to make rodlets and their glycosylation were not tested.

On conidia the rodlets are packed into distinct nanodomains, with a width of 60 to 100 nm while the height of the layer is estimated to be around 5 nm [this study and (Zykwinska et al., 2014b)], suggesting that the nanodomains are organized in multilayers on the surface of the conidium. The parallel organization of rodlets could arise from the assembly of the oligomers directly on the conidium surface or from the adhesion of rodlets aggregated in the medium prior to binding to the cell wall. The growth of one rodlet may provide a surface that favours nucleation and elongation of an adjacent rodlet, a process of secondary nucleation that has been shown to be important in the formation of some pathogenic amyloids (Gebbink et al., 2005, Pham et al., 2016). The observation that rodlets in adjacent nanodomains are oriented at angles of up to 90° may be consistent with repulsion between the outer hydrophobic components of different layers but could also be a consequence of the termination of nucleation and/or elongation when coverage of the conidium surface by rodlets removes the available surface. Interestingly, eventhough acid extraction leads to full-length RodA and a truncated version of the protein lacking 40 aminoacids (Fig. S7), incubation with hydrofluoric or formic acid did not degrade recombinant RodA into a truncated form lacking the N-terminal 40-amino acids. This fragment of RodA was only induced in vitro by the incubation of rRodA with the serine protease Alp1. These results indicate that aminoacids 40 or 41 are a sensitive exposed point in the rodlets that may be accessible to proteases from the inner cell wall.

While RodA clearly contributes to conidial hydrophobicity, an additional element to take into account is the role of other members of the hydrophobin family in controlling the hydrophobic properties of the conidium. In A. nidulans, all six hydrophobins contributed to hydrophobicity of the spore surface and were able to self-assemble (Grünbacher et al., 2014). However, only the deletion of RODA led to a mutant without rodlet on the surface even though DewA was able to form rodlets in vitro. When DewA and DewB were placed under the control of the RODA promoter in a ΔrodA mutant, both hydrophobins were able to produce rodlets, albeit with a different structure than the classical parental strain. Similarly, when the hydrophobins of S. commune (SC1 and 4) or RodA and Dew A of A. nidulans, or EAS of N. crassa were expressed from the MPG1 promoter of M. oryzae, they were also able to complement, although only partially, the MPG1 mutation, showing at the same time the lack of specificity of the hydrophobin aggregation but the need to recognize specific fungal features to induce the proper formation of rodlets on the conidial surface (Scholtmeijer et al., 2009, Kershaw et al., 1998). In Beauvaria bassiana, the single hydrophobin Hyd1 is able to form rodlets although the rodlets are truncated and incomplete suggesting that the two hydrophobins Hyd1 and 2 of this species act together to form the rodlets. In contrast in A. fumigatus, although eight hydrophobin genes (RODA to G) were identified (Jensen et al., 2010), only RodA was responsible for the formation of rodlets since a septuple RODB/C/D/E/F/G mutant with all these genes deleted but with wild-type RodA appeared like the parental strain (Valsecchi et al., 2017). The function of the other hydrophobins in A. fumigatus remains unknown.

3.2. Role of rodlets in A. fumigatus pathogenicity

Several biological facts suggest a putative role of rodlets in the pathogenicity of A. fumigatus, although pros and cons arguments have been published. First, the RodA protein itself, even in drastically different conformations or with point mutations is immunologically inert. The reasons for this lack of immune activation remain unknown and unlike other functional and disease-associated β-amyloids, which stimulate the innate cells via TLR and inflammasome activation (Halle et al., 2008, Tükel et al., 2009), the structure of of RodA does not dictate immune inertness. Our data on RodA and recent unpublished data (Heddergott and Latgé) on other cysteine-rich proteins of low Mr suggests that the amino acid sequence is responsible for the lack of immunogenicity against RodA. Second, by masking inner cell wall PAMPs like β-glucans and mannans, the rodlets are responsible for the lack of immediate recognition of conidia by the immune cell pattern recognition receptors (Bayry et al., 2014, Beauvais et al., 2013). In a murine model of corneal infection, the ΔrodA mutant is less pathogenic because of an increase in cytokine production, which boosts the anti-fungal immune response (Carrion et al., 2013). However, in our current animal experiment with intra tracheal inoculation of C57/Bl6 mice or in earlier assays with OF1 using intranasal inoculations and severe corticosteroid/cyclophospahmide immunosuppressions (Thau et al., 1994, Valsecchi et al., 2017), no difference in pathogenicity of the RodA mutants and parental strain was observed. Third, conidial rodlets have a negative impact on the innate immune mechanisms: they reduce NET formation when neutrophils come into contact with conidia and the addition of RodA to ΔrodA mutant conidia reduces the formation of NET (Bruns et al., 2010) and decrease macrophage efficacy (Dagenais et al., 2010). Fourth, the rodlet layer makes the conidium less permeable to the external antifungal molecules. The loss of rodlets and change in hydrophobicity that occurs during germination is indeed associated with an increased sensitivity to antifungal drugs (Dague et al., 2008a). Finally, hydrophobins favour the binding of enzymes to their substrate and stimulate their enzymatic activity (Pham et al., 2016, Ribitsch et al., 2015, Takahashi et al., 2005, Tanaka et al., 2017). This has been especially shown with MPG1 and two orthologs of RodA, namely A. oryzae RolA and A. nidulans RodA that have been shown to interact via ionic interaction with enzymes such as cutinases. It remains to be investigated whether fungal enzymes involved in pulmonary matrix degradation and host collectins and antimicrobial peptides bind to hydrophobin rodlets and play a role during lung infection by A. fumigatus.

4. Conclusions

The hydrophobin, RodA, forms functional amyloids with a rodlet morphology that coat A. fumigatus conidia. Assembly of parental and point mutated RodA proteins in vitro and on the conidial surface was analyzed with multiple technical approaches. Proper rodlet secretion and assembly requires the presence of intact cysteine bridges and two amyloidogenic regions. Even when disorganized, the rodlet layer is able to immunosilence the conidium. Complete degradation of the rodlet layer during germination by cell wall proteases activates immune cells. These studies have shown that rodlets are a dynamic structure that continuously evolves from conidial formation to germination and play a role during the early establishment of aspergillosis. Progress in understanding the mechanisms of self-assembly and the rodlet structure may also lead to advances towards solving medical problems associated with amyloid aggregation.

5. Material and methods

5.1. Extraction of the native RodA from conidia of A. fumigatus

RodA was extracted from dry conidia of A. fumigatus by a 2 h incubation on ice with formic acid. The material extracted was similar to the one extracted with a 48% hydrofluoric acid extraction for 72 h at 4 °C shown before to isolate rodlets from conidia (Aimanianda et al., 2009). The presence of rodlets was analyzed by SDS-PAGE using a 15% polyacrylamide gel and by Western blotting with an anti-RodA antibody (Valsecchi et al., 2017).

5.2. Production of the recombinant RodA protein for NMR analysis

The sequence used to prepare the recombinant RodA protein for solution NMR corresponds to residues 19-159 of A. fumigatus A1163 RodA (AFUB_057130) without the predicted N-terminal secretion peptide and containing an extra serine N-terminal residue that arises from cloning. The protein was obtained in lyophilized form as described (Pille et al., 2015) with a slight modification. Briefly, the HisTag-ubiquitin-rRodA fusion protein was encoded on a pET-28b(+) plasmid (Proteogenix) conserving the C-terminal ubiquitin GG recognition motif for deubiquitinases. The proteolysis step to separate RodA from the hexa-histidine-tagged ubiquitin was performed with His-tagged-deubiquitinase UBP41. Uniformly 15N and 15N/13C doubly labeled rRodA was expressed in minimal media containing 15NH4Cl and U-13C6 glucose (Euriso-top, Saclay) as sole sources of nitrogen and carbon, respectively. The rRodA was obtained after in vitro oxidative refolding. Integrity, label and sequence of the protein were analyzed by mass spectrometry. Protein samples were typically prepared at 0.36–0.69 mM concentrations in 20 mM CD3COONa pH 4.3 10% D2O. No dependence of line width or chemical shifts, and no signal intensity variation over time were observed in 1H-15N HSQC between 0.10 and 0.69 mM concentrations, indicating that the soluble form does not self-assemble in this concentration range and that samples were stable.

Doubly labeled conidial RodA was extracted from A. fumigatus conidia grown in minimal media supplemented with 15NH4Cl and U-13C6 glucose. Mature conidia were harvested and washed extensively in Tween 20 0.05%. To recover RodA protein, lyophilized conidia were incubated with 100% formic acid on ice (10 min to 2 h). After removal of the conidia by centrifugation, the supernatant was flushed with gaseous nitrogen to remove formic acid and the protein was then dissolved in water. NMR samples were prepared at 50–60 µM concentrations in the same buffer that was used for recombinant RodA.

5.3. NMR and structure calculation methods

Experiments were performed on a 14.7 T Direct Drive 600 NMR System spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara) equipped with a triple resonance cryogenic probe. Spectra were recorded at 25 °C using VnmrJ 3.2A (Agilent). Processing and analysis were performed with NMRPipe and CCPNMR Analysis, respectively. Proton, carbon and nitrogen resonances were assigned to backbone and side-chains atoms following a standard strategy with 2- (2D) and 3-dimensional (3D) heteronuclear experiments as described by Pille and co-workers (Pille et al., 2015). Assignment of RodA extracted from conidia was performed by comparing 1H-15N and 1H–13C HSQC, HNCO, HNCA experiments with the corresponding spectra of rRodA. Backbone amide 15N heteronuclear 1H-15N nOe (nuclear Overhauser enhancement) spectra were recorded to analyze the internal dynamics of rRodA, with a saturation/no-saturation delay of 3 s and a total recovery delay of 3.07 s. To obtain distance constraints, 3D 15N and 13C (aliphatic and aromatic regions) edited HSQC-nOesy were recorded with a 120 ms mixing time for nOe build-up (Kay et al., 1993, Muhandiram and Kay, 1994). Dihedral Phi and Psi angle constraints were calculated with Talos-N (Shen et al., 2009). An HNHA spectrum was used to validate Talos-N Phi angle constraints. Assignment of nOes and structure calculations were performed using ARIA 2.3.2 (Rieping et al., 2007) coupled to CNS 1.2.1 (Brunger et al., 1998). ARIA was run with a log-harmonic potential and automatic weighting of constraints spin diffusion correction, network anchoring and explicit water refinement using standard protocols. The ten lowest total-energy conformers were selected out of the 500 structures calculated in the final run. Structures were calculated with the disulfide bridge pairing determined experimentally for native EAS (Kwan et al., 2006) and observed in other recombinant hydrophobins [C1-C5 (56–133), C2-C6 (64–127), C3-C4 (65–105), C7-C8 (134–152)]. Herein, the cysteines are noted by their order of appearance in the sequence (C1 to C8) or by their sequence position. A careful analysis of the topology of the molecule (antiparallel β-sheets involving cysteines), of the network of nOes supporting the topology and the unambiguous assignment of several nOes between cysteines and involving neighbouring residues clearly demonstrated that rRodA showed the topology determined for native EAS. Structures were visualized and analyzed with PYMOL (Schrödinger LLC). Secondary structure content of RodA was determined according to DSSP. The quality of the structures was assessed with PROCHECK 3.5.4 (Laskowski et al., 1993), WHATCHECK (Hooft et al., 1996), MOLPROBITY (Chen et al., 2010) and PROSA (Sippl, 1993). The coordinates have been deposited to the pdb under the accession code 6GCJ.

5.4. Production of the rRodA and mutant proteins for Thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence and AFM imaging

Production of rRodA proteins, wild type and mutants, was achieved as previously described for the hydrophobin MPG1(Pham et al., 2016) apart from the following three changes. Fusion proteins were expressed using a modified version of the pHUE plasmid, encoding a version of ubiquitin with the C-terminal GG residues of ubiquitin replaced by a TEV protease recognition sequence. Oxidative refolding was achieved by dialysis against 10 mM reduced glutathione, 1 mM oxidized glutathione, 50 mM sodium acetate, 100 mM sodium chloride, pH 5.0) with two changes of redox buffer (6 h each at 4 °C; protein:buffer 1:25 (v/v)). Cleavage of hydrophobin from His6-ubiquitin occurred by addition of TEV enzyme. After reverse phase HPLC, the correct folding of rRodA and variants was confirmed by 1D 1H nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy.

5.5. Thioflavin T (ThT) rodlet self-assembly assay

Lyophilized rRodA and mutant proteins were first solubilized in deionized H2O. The stock protein solutions were diluted in ThT buffer (40 µM Thioflavin T in 20 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.0) to a final protein concentration of 25 µg/mL (1.73 µM). Samples were prepared to 100 µl in a black, clear-bottom 96-well microplate (Greiner Bio-One). The microplate was incubated at 50 °C and fluorescence recorded with 440/480 nm excitation/emission filters following every 90 s of double orbital shaking at 700 rpm in a BMG Labtech POLARstar Omega multi-mode microplate reader BMG Labtech Australia, VIC, Australia. All protein samples in each independent experiment were analyzed in triplicate. Each sample triplicate was normalized and graphed individually. Lag phase and time to reach half of the maximum fluorescence (t1/2) was interpreted from mean of triplicates. Lag phase and t1/2 were determined by the last time point before the normalized ThT fluorescence reached a value of 0.1 and the time at which normalized 0.5 ThT fluorescence reached 0.5, respectively. Statistical analysis was performed on GraphPad Prism (version 6.04 for Windows, GraphPad Software, CA, USA, www.graphpad.com). Data was evaluated using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test.

5.6. Surface structure of in vitro produced recombinant proteins and peptides seen with atomic force microscopy or transmission electron microscopy

Protein samples were diluted to 5 µg/mL (0.35 µM) in deionized H2O. For rRodA-WT and point mutations, a 50 µl drop of protein was deposited onto a freshly-cleaved highly-ordered pyrolytic graphite (HOPG) surface (Holgate Scientific, NSW, Australia) and allowed to dry down in a covered, ambient chamber overnight at room temperature. rRodA mutant proteins containing multiple mutations were prepared similarly, but were incubated at 50 °C in a humid environment for 2 h, followed by overnight drying in the ambient chamber. The HOPG surfaces were then further dried in a 70 °C oven for 2 h to remove any excess moisture.

The morphology of the assembled protein layers on the HOPG surface was imaged at ambient temperature using a Multimode Nanoscope® III atomic force microscopy (Veeco, CA, USA). The HOPG surfaces were scanned with tapping mode using a silicon scanning probe with tip radius <10 nm, force constant of 40 N/m and resonance frequency of 300 kHz (Tap300AI-G, BudgetSensors™, Bulgaria). The images were further processed with Gwyddion software (version 2.38, http://gwyddion.net).

For TEM, a 20-µL droplet of peptide (200 µg/mL) was placed on a formvar/carbon coated copper TEM grid (200-mesh, ProSciTech), and incubated for 2 min at room temperature. Excess solution was removed with filter paper and grids were washed twice by floating the grids on water droplets and wicking away the excess solution. Samples were stained with 2% uranyl acetate and imaged on a JEOL 1400 JEOL TEM equipped with a Morada G3 16 megapixel side camera. All images were analyzed with ImageJ.

5.7. Construction of the RodA point mutated and N-terminus minus ΔrodA mutants

5.7.1. Construction of the template plasmid for mutagenesis

The template for directed mutagenesis reactions was constructed with the pUC19 plasmid containing the RodA upstream region (1486 bp), the RodA open reading frame (583 bp), the hygromycin cassette beta recombinase (4767 bp) (Hartmann et al., 2010) and the RodA downstream region (853 bp). The pUC19 plasmid was digested with SacI and PstI and the hygromycin cassette was excised with FspI from plasmid pSK529 (Hartmann et al., 2010) and the corresponding band was purified from an agarose-gel. The RodA upstream region, open reading frame and downstream region were amplified by PCR using as template the gDNA of the CEA17_ΔakuBKU80 strain (da Silva Ferreira et al., 2006) and primers 1, 2, 3, 4 (see Supplementary Table 3). The final template plasmid was assembled with the GeneArt Seamless Cloning and Assembly kit (Thermo Fisher).

5.7.2. Construction of the point mutated RodA and N terminus minus strains