Abstract

Background

Acetaminophen is frequently prescribed for treating patients with the common cold, but there is little evidence as to whether it is effective.

Objectives

To determine the efficacy and safety of acetaminophen in the treatment of the common cold in adults.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL 2013, Issue 1, Ovid MEDLINE (1950 to January week 5, 2013), EMBASE (1980 to February 2013), CINAHL (1982 to February 2013) and LILACS (1985 to February 2013).

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing acetaminophen to placebo or no treatment in adults with the common cold. Studies were included if the trials used acetaminophen as one ingredient of a combination therapy. We excluded studies in which the participants had complications. Primary outcomes included subjective symptom score and duration of common cold symptoms. Secondary outcomes were overall well being, adverse events and financial costs.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened studies for inclusion, assessed risk of bias and extracted data. We performed standard statistical analyses.

Main results

We included four RCTs involving 758 participants. We did not pool data because of heterogeneity in study designs, outcomes and time points. The studies provided sparse information about effects longer than a few hours, as three of four included studies were short trials of only four to six hours. Participants treated with acetaminophen had significant improvements in nasal obstruction in two of the four studies. One study showed that acetaminophen was superior to placebo in decreasing rhinorrhoea severity, but was not superior for treating sneezing and coughing. Acetaminophen did not improve sore throat or malaise in two of the four studies. Results were inconsistent for some symptoms. Two studies showed that headache and achiness improved more in the acetaminophen group than in the placebo group, while one study showed no difference between the acetaminophen and placebo group. None of the included studies reported the duration of common cold symptoms. Minor side effects (including gastrointestinal adverse events, dizziness, dry mouth, somnolence and increased sweating) in the acetaminophen group were reported in two of the four studies. One of them used a combination of pseudoephedrine and acetaminophen.

Authors' conclusions

Acetaminophen may help relieve nasal obstruction and rhinorrhoea but does not appear to improve some other cold symptoms (including sore throat, malaise, sneezing and cough). However, two of the four included studies in this review were small and allocation concealment was unclear in all four studies. The data in this review do not provide sufficient evidence to inform practice regarding the use of acetaminophen for the common cold in adults. Further large‐scale, well‐designed trials are needed to determine whether this intervention is beneficial in the treatment of adults with the common cold.

Plain language summary

Acetaminophen (also called paracetamol) for the common cold in adults

The common cold is the most frequent viral infection of the upper respiratory tract. Adults in the US experience two to four colds per year. The symptoms of the common cold usually include nasal obstruction, headache, sore throat, sneezing, cough, malaise and nasal discharge. There is no effective therapy for the common cold and most medications are symptomatic. Acetaminophen (also called paracetamol) is widely used as the major ingredient in combination medications for the common cold. However, there is little information about the effectiveness and safety of this treatment. We reviewed studies to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of acetaminophen in the treatment of the common cold in adults. The evidence is current to February 2013.

We identified four trials that included 758 participants. We excluded studies in which the participants had complications. Two of the four included studies in this review were small and the quality of the evidence was low to moderate. We do not know if acetaminophen is effective for reducing common cold symptoms or its adverse effects. We cannot either 'recommend' or 'not recommend' its use in common practice because we do not have enough well‐designed trials to reach a conclusion. There is a need for more high‐quality studies to determine the effectiveness of acetaminophen in relieving common cold symptoms.

Background

Description of the condition

The common cold is the most prevalent viral infection of the upper respiratory tract. Adults in the US experience two to four colds per year. It is estimated that USD 2.9 billion is spent annually on medications for patients with the common cold, yet the infection is self limiting (Fendrick 2003). There are at least 200 viral types and other infectious agents that can cause the common cold. The rhinoviruses are the most common and are responsible for 40% of cases: corona viruses causing 10%; respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza and influenza virus approximately 10% to 15%; and others 5% to 20% (Treanor 2000). The common cold usually occurs in early spring and autumn, with symptoms including sore throat, sneezing, nasal stuffiness and discharge, cough, mild fever, headache, hoarseness, lethargy and malaise, which resolve within seven to 10 days, although some symptoms persist for over three weeks. Despite the self limiting nature of the common cold, complications such as otitis media, bacterial sinusitis, and exacerbation of asthma and pneumonia can make it a significant and serious problem for part of the population. There is no effective therapy for the common cold and most medications are symptomatic (Heikkinen 2003).

Description of the intervention

As there is no cure for the common cold, current symptomatic treatments include antihistamines (De Sutter 2012), decongestants (De Sutter 2012), echinacea (Linde 2008), vitamin C (Hemilä 2013), zinc (Singh 2011b), heated humidified air (Singh 2011a), antivirals (Gwaltney 2002), antibiotics (Arroll 2010), Chinese medicinal herbs (Zhang 2009), non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory agents (Kim 2009) and garlic (Lissiman 2012). However, none of these medications have been proven to be effective for the common cold due to a lack of strong evidence.

Acetaminophen (also known as paracetamol) is widely used as the major ingredient in combination medications for the common cold. As a non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug (NSAID), acetaminophen has antipyretic and analgesic effects for mild to moderate pain or fever. However, the anti‐inflammatory action or platelet‐inhibiting properties are weak (Botting 2000). It is recommended as the first‐line drug for relieving pain associated with osteoarthritis, rheumatism (Shen 2006) and lower back pain (Reece 2008). Many studies have shown that liver damage due to acetaminophen overdose is the most common cause of acute liver failure in the United States (Bower 2007). With the recommended therapeutic dosage, the side effects of acetaminophen are few, without the gastric toxicity of most NSAIDs. One study found that asthma morbidity and rhinitis may be caused by frequent use of acetaminophen (Shaheen 2000).

How the intervention might work

The mechanism of action of acetaminophen is still unclear despite it having been widely used for more than a century. Various studies have concluded that acetaminophen has a central analgesic effect which is generally explained by the following two mechanisms. The first mechanism is its selective reduction of prostaglandins, which are mediators of fever, pain and inflammation, by blocking the cyclooxygenase (COX) pathway in the central nervous system. However, this theory is not well supported and it is suggested that acetaminophen reduces the active oxidised form of COX to an inactive form, instead of binding to the active site of COX (Lucas 2005). The second mechanism is that the analgesic effect of acetaminophen involves stimulation of the descending serotonergic pathways; this is supported by the study finding that administration of a 5‐hydroxytryptamine type 3 antagonist in humans blocks the analgesic action of acetaminophen (Pickering 2006).

Why it is important to do this review

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have found that acetaminophen is an effective (Burnett 2006; Mizoquchi 2007; Schachtel 1988) and safe (Graham 1990; Moore 2003) treatment for the common cold. A review article showed that acetaminophen in over‐the‐counter doses is safe and effective for colds and does not prolong the duration of colds or destroy the immune system (Eccles 2006b). Acetaminophen is used worldwide to treat the common cold despite there being little information about the effectiveness and safety of this treatment. We have performed a Cochrane systematic review of RCTs to determine the effectiveness and safety of acetaminophen for the common cold.

Objectives

To determine the efficacy and safety of acetaminophen in the treatment of the common cold in adults.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

RCTs which evaluated acetaminophen in the treatment of the common cold in adults. We included studies using acetaminophen as one ingredient of a combination therapy. We excluded studies if they did not compare acetaminophen with placebo but used active comparators in the control group. We also excluded studies in which the participants had complications such as otitis media, bacterial sinusitis and exacerbation of asthma or pneumonia.

Types of participants

Participants with the common cold, aged 12 years or older, of either gender.

Types of interventions

Acetaminophen at various doses or in combination with other ingredients versus placebo or no treatment for the common cold.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Subjective symptom score. Total scores are calculated by summing up all symptom scores. Each symptom score was graded on a severity visual analogue scale (VAS) of 0 to 3, 0 to 4, or 0 to 10 cm.

Duration of common cold symptoms.

Secondary outcomes

Overall well being.

Adverse events.

Financial costs.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) 2013, Issue 1, part of The Cochrane Library, www.thecochranelibrary.com (accessed 13 February 2013), which contains the Cochrane Acute Respiratory Infections Group's Specialised Register, MEDLINE (1950 to February 2013), EMBASE (1980 to February 2013), CINAHL (1982 to February 2013) and LILACS (1985 to February 2013).

We used the following search strategy to search MEDLINE and CENTRAL. We combined the MEDLINE search with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomised trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐ and precision‐maximising version (2008 revision); Ovid format (Lefebvre 2011). The search strategy was adapted to search EMBASE (see Appendix 1), CINAHL (see Appendix 2) and LILACS (see Appendix 3). There were no language or publication restrictions.

MEDLINE (Ovid)

1 Common Cold/ 2 common cold*.tw. 3 (upper adj5 respiratory infection*).tw. 4 upper respiratory tract infection*.tw. 5 (coryza or acute rhinit* or rhinosinusit* or nasosinusit*).tw. 6 Rhinovirus/ 7 Coronavirus/ 8 Coronavirus Infections/ 9 respiratory syncytial viruses/ or respiratory syncytial virus, human/ 10 Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infections/ 11 parainfluenza virus 1, human/ or parainfluenza virus 3, human/ 12 parainfluenza virus 2, human/ or parainfluenza virus 4, human/ 13 exp influenzavirus a/ or exp influenzavirus b/ 14 Adenoviridae/ 15 (infection* adj5 (rhinovirus* or coronavirus* or adenovir* or rsv or respiratory syncytial virus* or parainfluenza* or influenza*)).tw. 16 or/1‐15 17 Acetaminophen/ 18 (acetaminophen or acetominophen or panadol or paracetamol or tylenol).tw. 19 17 or 18 20 16 and 19

Searching other resources

The review authors contacted the pharmaceutical manufacturers for details of unpublished and ongoing trials. We also searched and identified the relevant trials or reviews in reference lists. There were no language or publication restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (LS, YJ) independently scanned the title, abstract and keywords of every record retrieved to determine which studies required further assessment.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (LS, YJ) independently extracted data regarding details of study population, intervention and outcomes using a standard data extraction form specifically adapted for this review. The data extraction form included the following items.

General information: published/unpublished, title, authors, country of study, contact address, year of study, language of publication, year of publication, sponsor/funding organisation, setting.

Methodological details: including criteria for 'Risk of bias' assessment (below).

Intervention: descriptions of acetaminophen (dose, route, timing), descriptions of co‐medication(s) (dose, route, timing).

Participants: inclusion and exclusion criteria, total number and number in comparison groups, sex, age, baseline characteristics, withdrawals/losses to follow‐up (reasons/description), subgroups.

Outcomes: subjective symptom score, days from the onset to resolution of symptoms, overall well being, adverse events, costs.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (LS, YJ) independently assessed each included study using The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing 'Risk of bias' (Higgins 2011). This tool addresses six specific domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other issues (for example, extreme baseline imbalance) (Appendix 4). We assessed blinding and completeness of outcome data for each outcome separately. We completed a 'Risk of bias' table for each eligible study. We resolved disagreements by discussion to reach a consensus and a third review author (DBR) adjudicated any persisting differences.

We used a 'Risk of bias' summary figure to present all of the judgements in a cross‐tabulation of study by entry. This display of internal validity indicates the weight the reader may give the results of each study.

Measures of treatment effect

We described the treatment effect according to the included studies.

Unit of analysis issues

All included studies were RCTs. The unit of analysis was the individual participant and the individual participants were randomised.

Dealing with missing data

If data are available in the future to pool, we will analyse data according to the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) principle; that is, we will analyse all participants included in the study at the point of randomisation according to their assigned treatment group, regardless of whether or not the treatment was completed.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We described the heterogeneity amongst the included studies. In the future, if the number and characteristics of studies suggest that meta‐analysis may be feasible, we will measure heterogeneity using the Chi2 test with significance being set at P < 0.1. We will use the Chi2 test to estimate the total variation due to heterogeneity across studies (Higgins 2003). We will also use the I2 statistic to quantify inconsistencies throughout the trials. We will consider a value less than 25% to represent low risk of heterogeneity, justifying the use of a fixed‐effect model for meta‐analysis. We will consider a value between 25% and 50% as indicative of a moderate level of heterogeneity and we would use a random‐effects model. We will consider a value higher than 75% a high level of heterogeneity and in this case meta‐analysis would not be appropriate.

Assessment of reporting biases

We did not assess publication bias as we only included four trials. Ten studies is a minimum to create a funnel plot (Higgins 2011). In future updates, if we identify more studies, we will conduct a funnel plot analysis to check for publication bias.

Data synthesis

Two review authors (LS, YJ) independently entered data into RevMan 2012. We summarised findings of individual studies in a narrative format. We did not pool data because of heterogeneity in study design, outcomes and time points. In the future, if there is sufficient homogeneity in populations, study design and outcome measures, we will pool results following the assessment for statistical heterogeneity as described above.

We did not perform a subgroup analysis in this review. In the future, if we identify suitable studies, we will consider subgroup analysis depending on numbers and characteristics of studies. A priori subgroups will include the following.

Baseline symptom severity.

Age.

Gender.

Time from symptom onset to enrolment in the study.

We did not conduct a sensitivity analysis. If a sufficient number of trials are found in future updates, we will carry out a sensitivity analysis to assess the robustness of the results as follows.

Exclusion of studies with inadequate allocation concealment.

Exclusion of studies in which the outcome evaluation was unblinded.

Results

Description of studies

The search retrieved 39 records from MEDLINE (Ovid), 59 records from CENTRAL, 243 records from Embase.com, 15 records from CINAHL and one record from LILACS. With duplicates removed this left a total of 269 search results. See the Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

Results of the search

Our primary search generated 269 results. After screening, we considered 10 trials to be potentially eligible and reviewed the full text. Seven trials met our inclusion criteria. The full texts of three trials have not been retrieved, so we listed them in the section Characteristics of studies awaiting classification. We excluded three trials due to lack of placebo control.

Included studies

Design

All included trials were randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, parallel‐group trials. Two studies were conducted in the US (Ryan 1987; Sperber 2000), one study in Ukraine and Russia (Bachert 2005) and one study in Australia (Graham 1990). Two studies took place in an out‐patient setting, one in a Medical University, and one did not specify the setting. One trial consisted of five treatment arms: two arms for different doses of acetaminophen, two arms for different doses of aspirin and one arm for placebo (Bachert 2005). One trial had four treatment arms: one arm for acetaminophen, one arm for aspirin, one arm for ibuprofen and one arm for placebo (Graham 1990). One trial had three treatment arms: one arm for acetaminophen, one arm for fenoprofen and one arm for placebo (Ryan 1987). One trial had two arms: 60 mg of pseudoephedrine plus 1000 mg of acetaminophen or placebo (Sperber 2000). Among these four studies, only one included participants with an experimental infection by rhinovirus type 2 (Graham 1990).

Participants

The ages of participants ranged from 17 to 65 years. The entry criteria in the trials were similar.

Intervention

For the intervention group, acetaminophen was used in various doses. In two studies (Bachert 2005; Ryan 1987) participants took only a single dose because the study period was four or six hours. One study (Bachert 2005) used a dose of 500 mg (one tablet) and 1000 mg (two tablets); the other study (Ryan 1987) used 650 mg. The dose in another study (Sperber 2000) was 1000 mg (one tablet containing pseudoephedrine 60 mg and acetaminophen 1000 mg) every six hours. The dose in another study was 1000 mg (two capsules) every six hours (Graham 1990).

Outcome measures

A number of different tools were used for determining subjective symptom scores in the included studies, which included ordinal scales from 0 to 3, 0 to 4, or 0 to 10. Most trials reported subjective symptom scores but each cold symptom included in the studies was different.

Excluded studies

We excluded three trials (Eccles 2006a; Koytchev 2003; Sedinkin 2004) due to lack of placebo control.

Risk of bias in included studies

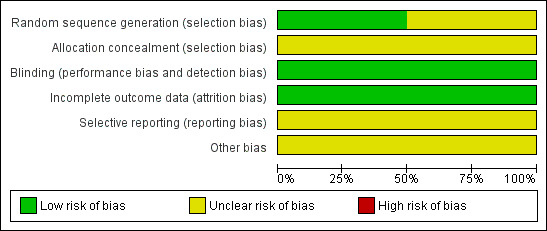

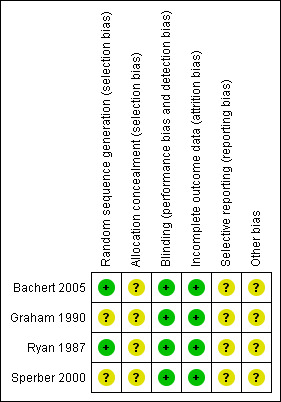

'Risk of bias' assessments are detailed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table and are represented by Figure 1 and Figure 2.

1.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Ryan 1987 states that computer‐generated randomisation was used and Bachert 2005 states that patients were allocated by permuted block randomisation (block size of five). The method of randomisation was not discussed in the other two studies (Graham 1990; Sperber 2000). The method of allocation concealment was unclear in the four studies.

Blinding

All four studies were blinded using identically appearing tablets or capsules.

Incomplete outcome data

One study had no missing data (Ryan 1987). The other three studies had incomplete data and ITT analyses were performed.

Selective reporting

For all studies, no information was available for participants who were not enrolled.

Other potential sources of bias

Two studies were supported by pharmaceutical companies (Bachert 2005; Ryan 1987).

Effects of interventions

Primary outcomes

1. Subjective symptom score

Different scales were used to report the primary outcomes. Therefore, we did not pool data.

Ryan 1987 estimated the intensity of pain on a four‐point scale ('none' = 0, 'mild' = 1, 'moderate' = 2, 'severe' = 3). There were 32 participants in both the acetaminophen group and the placebo group. The baseline mean for the pain scores was 2.34 for the acetaminophen group and 2.25 for the placebo group. The authors calculated the pain intensity difference (PID) by subtracting the pain intensity score at one, two, three and four hours from the scores at zero hour. There was a decrease in mean pain intensity score of 0.87 in the acetaminophen group and 0.66 in the placebo group. The difference in pain intensity scores between the two groups was not statistically significant.

Bachert 2005 used an ordinal scale (from 0 = none to 10 = severe) to rate the common cold symptoms. The symptoms were rated at baseline and again at two, four and six hours after treatment. The baseline intensity of the common cold symptoms was comparable between groups. Each symptom score was reported in Table III of their study. A significant decrease was seen in the mean intensity score for headache, achiness and feverish discomfort in the acetaminophen group at most time points (P < 0.001) compared to the placebo group. However, the study did not show a significant difference in sore throat between the two groups at ant time point.

Sperber 2000 assessed common cold symptoms using a zero to four‐point scale which represented "absent, mild, moderate, moderately severe, or severe". Symptoms were scored before and at two hours after the first and second doses. The mean scores for headache, nasal obstruction and rhinorrhoea were significantly decreased after the first or second dose in the pseudoephedrine and the acetaminophen group. There was no statistical difference in scores for sneezing, sore throat, cough and malaise between the acetaminophen group and the placebo group. The score values were reported in Table 2 of their study.

Graham 1990 used the same scale described in Ryan 1987. These scores were recorded daily for day 0 to 14. Scores for each cold symptom were totalled by adding scores from days one to 14 and subtracting the baseline score. Nasal obstruction was significantly increased in the acetaminophen group compare to the placebo group (P < 0.05). No significant differences were seen for headache, malaise and achiness between the acetaminophen group and the placebo group.

2. Duration of common cold symptoms

None of the included studies reported the duration of common cold symptoms.

Secondary outcomes

1. Overall well being

None of the included studies reported overall well being.

2. Adverse events

Two studies reported different side effects of acetaminophen. Sperber 2000 reported adverse events such as nervousness, nausea, dizziness, dry mouth and somnolence in the pseudoephedrine and the acetaminophen group. Bachert 2005 reported the two most frequently cited adverse events which were increased sweating and gastrointestinal disturbances.

3. Financial costs

None of the included studies reported financial costs.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The findings of four studies identified by this review were inconsistent. Two studies showed that acetaminophen was effective for relieving headache (Bachert 2005; Sperber 2000), but one study with a small number of participants found no significant change in headache intensity in either the intervention or placebo group (Graham 1990). Effectiveness of acetaminophen in improving nasal obstruction was found in the acetaminophen group in one of the two included studies and this was statistically significant (Sperber 2000). On the other hand, Graham 1990 showed an increased number of participants with nasal obstruction in the acetaminophen group compared to the placebo group. No correlation was found between subjective changes in achiness in three studies (Graham 1990; Ryan 1987; Sperber 2000). However, outcomes from another study were found to favour acetaminophen in improving achiness (Bachert 2005). Sore throat was shown to be similar in both the acetaminophen and placebo group, with no significant change.

For most studies, all acetaminophen‐related adverse effects were mild or moderate except for two cases of severe nausea reported in one study (Sperber 2000).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The time periods of the included studies were short. Three studies estimated the effect of acetaminophen in four to six hours. It is not known whether a prolonged study duration would alter the applicability of the results. Among the four included studies, one study compared a combination of acetaminophen and pseudoephedrine to placebo, so it is difficult to tell from which ingredient the effect and adverse events resulted.

Quality of the evidence

The method of allocation concealment was unclear in all the included studies. Two studies were supported by pharmaceutical companies. The study period was short for most studies. There were serious methodological limitations. Confidence intervals were not reported in all of the studies so it is difficult to evaluate the accuracy of the results. However, we found two studies including small numbers of participants which may affect the accuracy of the results. We did not perform a funnel plot analysis and so could not evaluate publication bias. Overall we consider the quality of the evidence to be low to moderate.

Potential biases in the review process

We undertook a complete, systematic search of the literature to identify all studies meeting the inclusion criteria for this review. However, the full texts of three trials have not been retrieved. We contacted the trial authors by e‐mail but did not receive any replies so we cannot confirm whether these three studies will meet the inclusion criteria.

In one included study (Graham 1990), 60 healthy volunteers were challenged with rhinovirus and randomised to one of four treatment arms: aspirin, acetaminophen, ibuprofen or placebo. Fourteen out of 15 volunteers were successfully infected in both the acetaminophen and placebo treatment arms. However, among those infected participants, only nine of the acetaminophen group experienced an upper respiratory illness, compared to 11 in the placebo group, so this could overestimate the effect in the acetaminophen group.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The results of this review are in agreement with Eccles' systematic review (Eccles 2006b). This review included one randomised controlled trial (Bachert 2005) and one placebo‐controlled study. The authors concluded that there was relatively little information on the use of acetaminophen in treating colds.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The data in this review do not provide sufficient evidence to inform practice regarding the use of acetaminophen for the common cold in adults.

Implications for research.

A large randomised controlled trial is needed to determine whether acetaminophen is effective when compared with placebo in treating the common cold. Randomised controlled trials should consider the following:

study methods which include allocation concealment;

a longer study period;

primary outcomes which include common cold symptom scores, each common cold symptom score and duration of an episode of the common cold;

acetaminophen on its own as one of the active treatments rather than in combination with another treatment;

use of a visual analogue scale to grade subjective symptom scores.

Feedback

Plain language summary title, 16 August 2013

Summary

I was wondering why the plain language summary uses Aceteminophen in the title instead of paracetemol.

I agree with the conflict of interest statement below: I certify that I have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with a financial interest in the subject matter of my feedback

Caroline Struthers Cochrane Collaboration, Training Coordinator.

Reply

The plain language summary title has been amended accordingly. Thank you for your comment.

Contributors

Birong Dong

'Acetaminophen (paracetamol) for the common cold in adults, 13 March 2015

Summary

Dear editors,

I am writing you for the first time. In this review, the main results of the abstract concluded that "Participants treated with acetaminophen had significant improvements in nasal obstruction in two of the four studies. " But this description might be misleading. One of these two studies (Graham 1990) showed, nasal obstruction was significantly "increased severity score" in the acetaminophen group compare to the placebo group. Another study (Sperber 2000) contained pseudo ephedrine in the acetaminophen group. So I don't think that the acetaminophen is effective for nasal obstruction. Please confirm the original articles and the conclusion. Thank you for your understanding and help.

I agree with the conflict of interest statement below: I certify that I have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with a financial interest in the subject matter of my feedback.

Motoharu Fukushi fukushimoto@gmail.com Affiliation: Musashikokubunji Park Clinic, Japan

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 14 October 2015 | Feedback has been incorporated | Feedback comment published |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 11, 2010 Review first published: Issue 7, 2013

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 16 August 2013 | Feedback has been incorporated | Feedback added and change made to the plain language summary title. |

Acknowledgements

We thank Elizabeth Dooley, Managing Editor of the Cochrane Acute Respiratory Infections Group. We thank the Chinese Cochrane Centre for help in completing the protocol. We also wish to thank the following people for commenting on the draft protocol: Chanpen Choprapawon, Ann Fonfa, Nicholas Moore, Andrew Pothecary, Mark Griffin and Hans van der Wouden; and we thank the following people for commenting on the draft review: Noha Usama, Nicholas Moore, Andrew Pothecary, Robert Ware and Hans van der Wouden.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Embase.com search strategy

| #22 | #18 AND #21 |

| #21 | #19 OR #20 |

| #20 | random*:ab,ti OR placebo*:ab,ti OR factorial*:ab,ti OR crossover*:ab,ti OR 'cross over':ab,ti OR 'cross‐over':ab,ti OR volunteer*:ab,ti OR assign*:ab,ti OR allocat*:ab,ti OR ((singl* OR doubl*) NEAR/2 (blind* OR mask*)):ab,ti AND [embase]/lim |

| #19 | 'randomized controlled trial'/exp OR 'single blind procedure'/exp OR 'double blind procedure'/exp OR 'crossover procedure'/exp AND [embase]/lim |

| #18 | #14 AND #17 |

| #17 | #15 OR #16 |

| #16 | acetaminophen:ab,ti OR acetominophen:ab,ti OR panadol:ab,ti OR paracetamol:ab,ti OR tylenol:ab,ti AND [embase]/lim |

| #15 | 'paracetamol'/de AND [embase]/lim |

| #14 | #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 |

| #13 | (infection* NEAR/5 (rhinovir* OR coronavir* OR adenovir* OR rsv OR parainfluenza* OR influenza*)):ab,ti AND [embase]/lim |

| #12 | 'human adenovirus infection'/de AND [embase]/lim |

| #11 | 'influenza virus a'/exp OR 'influenza virus b'/exp AND [embase]/lim |

| #10 | 'parainfluenza virus 1'/de OR 'parainfluenza virus 2'/de OR 'parainfluenza virus 3'/exp OR 'parainfluenza virus 4'/de AND [embase]/lim |

| #9 | 'respiratory syncytial pneumovirus'/de OR 'respiratory syncytial virus infection'/de AND [embase]/lim |

| #8 | 'coronavirus'/de OR 'coronavirus infection'/de AND [embase]/lim |

| #7 | 'human rhinovirus'/exp OR 'rhinovirus infection'/de AND [embase]/lim |

| #6 | coryza:ab,ti OR 'acute rhinitis':ab,ti OR rhinosinusitis:ab,ti OR nasosinusitis:ab,ti AND [embase]/lim |

| #5 | 'rhinosinusitis'/de AND [embase]/lim |

| #4 | 'upper respiratory infection':ab,ti OR 'upper respiratory infections':ab,ti OR 'upper respiratory tract infection':ab,ti OR 'upper respiratory tract infections':ab,ti AND [embase]/lim |

| #3 | 'upper respiratory tract infection'/de OR 'viral upper respiratory tract infection'/de AND [embase]/lim |

| #2 | 'common cold':ab,ti OR 'common colds':ab,ti AND [embase]/lim |

| #1 | 'common cold'/de OR 'common cold symptom'/de AND [embase]/lim |

Appendix 2. CINAHL (Ebsco) search strategy

S33 S24 or S25 or S26 or S27 or S28 or S29 or S30 or S31 or S32 S32 (MH "Quantitative Studies") S31 TI placebo* or AB placebo* S30 (MH "Placebos") S29 TI random* or AB random* S28 (MH "Random Assignment") S27 TI (singl* blind* or singl* mask* or doubl* blind* or doubl* mask* or trebl* blind* or trebl* mask* or tripl* blind* or tripl* mask*) or AB (singl* blind* or singl* mask* or doubl* blind* or doubl* mask* or trebl* blind* or trebl* mask* or tripl* blind* or tripl* mask* ) S26 TI clinic* N1 trial* or AB clinic* N1 trial* S25 PT clinical trial S24 (MH "Clinical Trials+") S23 S19 and S22 S22 S20 or S21 S21 TI (acetaminophen or acetominophen or panadol or paracetamol or tylenol) or AB (acetaminophen or acetominophen or panadol or paracetamol or tylenol) S20 (MH "Acetaminophen") S19 S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12 OR S13 OR S14 OR S15 OR S16 OR S17 OR S18 S18 TI infection* N5 respiratory syncytial virus* or AB infection* N5 respiratory syncytial virus* S17 TI respiratory syncytial virus infection* or AB respiratory syncytial virus infection* S16 TI infection* N5 rsv or AB infection* N5 rsv S15 TI infection* N5 influenza* or AB infection* N5 influenza* S14 TI infection* N5 parainfluenza* or AB infection* N5 parainfluenza* S13 TI infection* N5 adenovir* or AB infection* N5 adenovir* S12 TI infection* N5 coronavir* or AB infection* N5 coronavir* S11 TI infection* N5 rhinovir* or AB infection* N5 rhinovir* S10 (MH "Influenzavirus A+") OR (MH "Influenzavirus B+") OR (MH "Influenzavirus C") S9 (MH "Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infections") S8 (MH "Respiratory Syncytial Viruses") S7 (MH "Coronavirus Infections") S6 (MH "Coronavirus") S5 TI (coryza or acute rhinit* or rhinosinusit* or nasosinusit*) or AB (coryza or acute rhinit* or rhinosinusit* or nasosinusit*) S4 TI upper respiratory infection* or AB upper respiratory infection* S3 TI upper respiratory tract infection* or AB upper respiratory tract infection* S2 TI common cold* or AB common cold* S1 (MH "Common Cold")

Appendix 3. LILACS search strategy

(mh:"Common Cold" OR "common cold" OR "common colds" OR "Resfriado Común" OR "Resfriado Comum" OR coryza OR "Coriza Aguda" OR "upper respiratory tract infection" OR "upper respiratory tract infections" OR "upper respiratory infection" OR "upper respiratory infections" OR "Infecciones del Tracto Respiratorio Superior" OR "Infecciones de las Vías Respiratorias Superiores" OR "Infecções do Trato Respiratório Superior" OR "Infecções das Vias Respiratórias Superiores" OR "Infecções das Vias Aéreas Superiores" OR "Infecções do Sistema Respiratório Superior" OR "acute rhinitis" OR rhinosinusitis OR nasosinusitis OR rinit* OR mh:rhinovirus OR rhinovir* OR mh:coronavirus OR coronavir* OR mh:"Coronavirus Infections" OR mh:"Respiratory Syncytial Viruses" OR "respiratory syncytial virus" OR "respiratory syncytial viruses" OR rsv OR "Virus Sincitiales Respiratorios" OR "Vírus Sinciciais Respiratórios" OR mh:"Respiratory Syncytial Virus, Human" OR mh:"Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infections" OR mh:"Parainfluenza Virus 1, Human" OR mh:"Parainfluenza Virus 3, Human" OR mh:"Parainfluenza Virus 2, Human" OR mh:"parainfluenza virus 4, human" OR parainfluenza* OR mh:"Influenzavirus A" OR mh:b04.820.545.405* OR mh:b04.909.777.545.405* OR mh:"Influenzavirus B" OR mh:b04.820.545.407* OR mh:b04.909.777.545.407* OR influenza* OR mh:adenoviridae OR adenovir*) AND (mh:acetaminophen OR acetaminophen OR acetominophen OR acetaminofén OR acetaminofen OR acetamidophenol OR acetaminofeno OR acetamidofenol OR panadol OR paracetamol OR tylenol) AND db:("LILACS")

Appendix 4. Assessment of risk of bias

Criteria for a judgement of 'yes' for the sources of bias

1. Was the allocation sequence randomly generated?

Yes, low risk of bias

A random (unpredictable) assignment sequence. Examples of adequate methods of sequence generation are computer‐generated random sequence, pre‐ordered sealed envelopes, telephone call to a central office, coin toss (for studies with two groups), rolling a dice (for studies with two or more groups), drawing of balls of different colours.

No, high risk of bias

Quasi‐randomised approach: examples of inadequate methods are: alternation, birth date, social insurance/security number, date in which invited to participate in the study and hospital registration number.

Non‐random approaches: allocation by judgement of the clinician; by preference of the participant; based on the results of a laboratory test or a series of tests; by availability of the intervention.

Unclear

Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement.

2. Was the treatment allocation adequately concealed?

Yes, low risk of bias

Assignment must be generated independently by a person not responsible for determining the eligibility of the participants. This person has no information about the persons included in the trial and has no influence on the assignment sequence or on the decision about whether the person is eligible to enter the trial. Examples of adequate methods of allocation concealment are: central allocation, including telephone, web‐based and pharmacy‐controlled, randomisation; sequentially numbered drug containers of identical appearance; sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes.

No, high risk of bias

Examples of inadequate methods of allocation concealment are: alternate medical record numbers; unsealed envelopes; date of birth; case record number; alternation or rotation; an open list of random numbers; or any information in the study that indicated that investigators or participants could influence the intervention group.

Unclear

Randomisation stated but no information on method of allocation used is available.

3. Blinding ‐ was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

(a) Was the participant blinded to the intervention?

Yes, low risk of bias

The treatment and control groups are indistinguishable for the participants or if the participant was described as blinded and the method of blinding was described.

No, high risk of bias

Blinding of study participants attempted, but likely that the blinding could have been broken; participants were not blinded, and the non‐blinding of others is likely to introduce bias.

Unclear

(b) Was the care provider blinded to the intervention?

Yes, low risk of bias

The treatment and control groups are indistinguishable for the care/treatment providers or if the care provider was described as blinded and the method of blinding was described.

No, high risk of bias

Blinding of care/treatment providers attempted, but likely that the blinding could have been broken; care/treatment providers were not blinded, and the non‐blinding of others is likely to introduce bias.

Unclear

(c) Was the outcome assessor blinded to the intervention?

Yes, low risk of bias

Adequacy of blinding should be assessed for the primary outcomes. The outcome assessor was described as blinded and the method of blinding was described.

No, high risk of bias

No blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome or outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding

Unclear

4. Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed?

(a) Was the drop‐out rate described and acceptable? The number of participants who were included in the study but did not complete the observation period or were not included in the analysis must be described and reasons given.

Yes, low risk of bias

If the percentage of withdrawals and drop‐outs does not exceed 20% for short‐term follow‐up and 30% for long‐term follow‐up and does not lead to substantial bias. (N.B. these percentages are arbitrary, not supported by literature.)

No missing outcome data

Reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome (for survival data, censoring unlikely to be introducing bias). Missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups. Missing data have been imputed using appropriate methods.

No, high risk of bias

Reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups.

Unclear

(b) Were all randomised participants analysed in the group to which they were allocated? (intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis)

Yes, low risk of bias

Specifically reported by authors that ITT analysis was undertaken and this was confirmed on study assessment, or not stated but evident from study assessment that all randomised participants are reported/analysed in the group to which they were allocated for the most important time point of outcome measurement (minus missing values), irrespective of non‐compliance and co‐interventions.

No, high risk of bias

Lack of ITT analysis confirmed on study assessment (patients who were randomised were not included in the analysis because they did not receive the study intervention, they withdrew from the study or were not included because of protocol violation) regardless of whether ITT reported or not. 'As‐treated' analysis done with substantial departure from the intervention received compared to that assigned at randomisation; potentially inappropriate application of simple imputation.

Unclear

Described as ITT analysis, but unable to confirm on study assessment, or not reported and unable to confirm by study assessment.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Bachert 2005.

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, parallel‐group trial | |

| Participants | Setting: out‐patient, conducted in Ukraine and Russia Study period: 6 hours Age: mean age 37.4 years (range 18 to 65) Sex: male/female: 201/191 Diagnostic criteria: participants with an oral temperature between 38.5 and 40°C and other symptoms of URTI which have lasted for no more than 5 days Inclusion criteria: participants between 18 and 65 years with an acute, uncomplicated, febrile URTI of suspected viral origin Exclusion criteria: bacterial infection of the respiratory tract; current antibiotic treatment or taken the previous week; asthma or hypersensitivity to acetaminophen and aspirin; peptic ulceration; gastric bleeding, haemorrhagic diathesis, hepatic and/or renal dysfunction, Gilbert's disease; patients have participated in other studies during the previous 4 weeks |

|

| Interventions | Participants received a single dose of aspirin 500 or 1000 mg, acetaminophen 500 or 1000 mg, or placebo | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: the AUC for the change in orally measured body temperature from baseline to 4 hours after dosing Secondary outcomes: the maximum temperature difference between baseline and the lowest measured body temperature, the time to the maximum temperature difference, the temperature difference between baseline and each measured time point after dosing, the intensity of the URTI symptoms (from 0 = none to 10 = severe) at baseline and again at 2, 4 and 6 hours after treatment, adverse events |

|

| Notes | The researchers conducted the study on behalf of Bayer Company and received remuneration | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Permuted block randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient data |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Identical colour, size and shape of tablet blinded to participants and investigators or study nurses |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 6 excluded for incomplete data for the primary endpoint at 4 hours after dosing, ITT analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Details not reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | The researchers conducted the study on behalf of Bayer Company and received remuneration for participation |

Graham 1990.

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled clinical trial | |

| Participants | Age: mean age: 20.1 years (range 18 to 30) Sex: male/female: 34/26 Diagnostic criteria: if 2 of the 3 following criteria were met: a total symptom score ≥ 6 above the baseline level (day 0); increased nasal discharge for 3 consecutive days; and the subjective impression that after the first 6 days after the challenge that he or she had a common cold, similar to a previous naturally acquired illness Inclusion criteria: healthy young adult volunteers free of URTI (runny or blocked noses, sore throat or cough for 2 days) for 2 weeks before virus challenge Exclusion criteria: took aspirin, acetaminophen, ibuprofen or other related drugs 2 weeks before the virus challenge Conducted in Australia Aetiology: experimental cold |

|

| Interventions | After intranasal challenge with RV2, the volunteers received medication on the first day of upper respiratory symptoms or on day 3 if no symptoms had developed. Medications were 4 g of aspirin (4 doses of 2 capsules, 500 mg per capsule), 4 g of acetaminophen (4 doses of 2 capsules, 500 mg per capsule), 1.2 g of ibuprofen (3 doses of 2 capsules and 1 dose of 2 placebo capsules, 200 mg per capsule), or placebo for 7 days | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: the common cold symptom scores (0 to 3) for day 0 to 14 Secondary outcome: side effect symptom scores |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Sixty healthy volunteers were randomised within three strata based on their initial serum antibody titer to RV2" Common: insufficient information to judge |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient data |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Identical capsules |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 4 uninfected participants were excluded from further analysis. ITT analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient data |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Insufficient data |

Ryan 1987.

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled clinical trial | |

| Participants | Setting: out‐patient, conducted in USA Age: acetaminophen group range 17 to 62; fenoprofen group: range 18 to 60; placebo group: range 24 to 60 Sex: male/female: 25/71 Diagnostic criteria: participants with systemic symptoms of malaise/aches judged to produce moderate pain and an oral temperature of at least 100 Inclusion criteria: the criteria for subject enrolment include systemic symptoms of malaise/aches judged to produce moderate pain and an oral temperature of at least 100 Exclusion criteria: pregnant or had language or intellectual barriers; clinical symptoms indicative of bacterial infections such as pneumonia, meningitis, streptococcal pharyngitis or tonsillitis; blood dyscrasias, carcinoma, serious kidney, liver, cardiac, gastrointestinal or metabolic disease; recent major surgery, history of drug hypersensitivity to study drugs; anticoagulant therapy; had administered another analgesic‐antipyretic drug prior to study |

|

| Interventions | Each treatment group administered a single oral dose: acetaminophen 650 mg, fenoprofen 200 mg or placebo | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes: rectal temperatures and intensity of pain on a 0 to 3 scale at zero time and 1, 2, 3, 4 hours following administration of drug Secondary outcome: adverse medication experiences during and at the end of the 4‐hour study interval |

|

| Notes | Funding source: supported in part by the Dista Products Company | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Each patient was assigned a chronological study number. These study number had been previously assigned to one of three treatment groups via a computer‐generated random numbers tables" Comment: probably done |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient data |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Each dose of medication was dispensed in identically appearing capsules in a double‐blind (patient and assessors) method" Comment: probably done |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No missing data |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient data |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Quote: "This research was supported in part by the Dista Products Company" Comment: it is unclear if the funding source did or did not have any role in the results |

Sperber 2000.

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled clinical trial | |

| Participants | Setting: Medical University, conducted in the United States Study period: 6 hours Age: acetaminophen group: mean age 27.6 years; placebo group: mean age 28.6 years, range 18 to 65 years Sex: female/male: 285/145 Inclusion criteria: participants had cold symptoms of 48 hours or less, and reported at least moderate symptom severity in response to the question, "Overall, how would you rate the severity of your sinus symptoms? Absent, mild, moderate, moderately severe, or severe." Exclusion criteria: pregnant, diastolic blood pressure greater than 90 mmHg, participants with illnesses might be exacerbated by sympathomimetic drugs or affect the assessment of common cold symptoms, receiving drugs that might interact with sympathomimetic drugs |

|

| Interventions | Participants were assigned either 60 mg of pseudoephedrine plus 1000 mg of acetaminophen or placebo tablets. The second dose was self administered 6 hours after the first dose | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: common cold symptom scores (0 to 4) | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Details not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient data |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Identically appearing tablet |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 18 participants did not complete the study. ITT analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient data |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Insufficient data |

AUC = area under curve ITT = intention‐to‐treat RV2 = rhinovirus type 2 URTI = upper respiratory tract infection

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Eccles 2006a | No placebo comparison |

| Koytchev 2003 | No placebo comparison |

| Sedinkin 2004 | No placebo comparison |

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

Blanco de la Mora 2000.

| Methods | We cannot retrieve the abstract of the study |

| Participants | Not known |

| Interventions | Not known |

| Outcomes | Not known |

| Notes |

Mizoguchi 2007.

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, multi‐centre, parallel design clinical trial |

| Participants | Eligible participants had to have at least moderate nasal congestion and a runny nose, at least mild cough and at least mild pain with one or more of the following: sore throat, sore chest, headache or body pain/aches |

| Interventions | A single night‐time dose of a syrup containing 15 mg dextromethorphan hydrobromide, 7.5 mg doxylamine succinate, 600 mg paracetamol and 8 mg ephedrine sulfate |

| Outcomes | The primary endpoint (composite of nasal congestion/runny nose/cough/pain relief scores 3 hours post‐dosing) |

| Notes |

Schachtel 1999.

| Methods | We cannot retrieve the abstract of the study |

| Participants | Not known |

| Interventions | Not known |

| Outcomes | Not known |

| Notes |

Contributions of authors

Siyuan Li (SL), Jirong Yue (JY), Bi Rong Dong (BD), Xiufang Lin (FL), Taixiang Wu (TW) and Ming Yang (MY) were all involved in developing the protocol. SL, JY, BD, MY were involved in selection of studies, extracting data and writing up findings. TW provided statistical expertise.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Chinese Cochrane Centre, China.

External sources

No sources of support supplied

Declarations of interest

None known.

Edited (no change to conclusions), comment added to review

References

References to studies included in this review

Bachert 2005 {published data only}

- Bachert C, Chuchalin AG, Eisebitt R, Netayzhenko VZ, Voelker M. Aspirin compared with acetaminophen in the treatment of fever and other symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection in adults: a multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, double‐dummy, placebo‐controlled, parallel‐group, single‐dose, 6‐hour dose‐ranging study. Clinical Therapeutics 2005;27(7):993‐1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Graham 1990 {published data only}

- Graham NMH, Burrell CJ, Douglas RM, Debelle P, Davies L. Adverse effects of aspirin, acetaminophen, and ibuprofen on immune function,viral shedding, and clinical status in rhinovirus‐infected volunteers. Journal of Infectious Diseases 1990;162:1277‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ryan 1987 {published data only}

- Ryan PB, Rush DR, Nicholas TA, Graham DG. A double‐blind comparison of fenoprofen, acetaminophen, and placebo in the palliative treatment of common nonbacterial upper respiratory infections. Current Therapeutic Research 1987;41(1):17‐23. [Google Scholar]

Sperber 2000 {published data only}

- Sperber SJ, Turner RB, Sorrentino JV, Connor RR, Rogers J, Gwaltney JM. Effectiveness of pseudoephedrine plus acetaminophen for treatment of symptoms attributed to the paranasal sinuses associated with the common cold. Archives of Family Medicine 2000;9:979‐85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Eccles 2006a {published data only}

- Eccles R, Jawad M, Jawad S, Ridge D, North M, Jones E, et al. Efficacy of a paracetamol‐pseudoephedrine combination for treatment of nasal congestion and pain‐related symptoms in upper respiratory tract infection. Current Medical Research & Opinion 2006;22(12):2411‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Koytchev 2003 {published data only}

- Koytchev R, Vlahov V, Bacratcheva N, Giesel B, Gawronska‐szklarz B, Wojcicki J, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy of a combined formulation (Grippostad‐C) in the therapy of symptoms of common cold: a randomised, double‐blind, multicenter trial. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2003;41(3):114‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sedinkin 2004 {published data only}

- Sedinkin AA, Balandin AV, Dimova AD. Results of an open prospective controlled randomised comparative trial of flurbiprofen and paracetamol efficacy and tolerance in patients with throat pain. Vestnik Otorinolaringologii 2004;1(5):52‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies awaiting assessment

Blanco de la Mora 2000 {published data only}

- Blanco de la Mora E, Loose I. Efficacy and safety of loratadin, pseudoephedrine & acetaminophen new formulation design for the symptomatic treatment of common cold. Investigation Medical International 2000;27(1):14‐25. [Google Scholar]

Mizoguchi 2007 {published data only}

- Mizoguchi H, Wilson A, Jerdack GR, Hull JD, Goodale M, Grender JM, et al. Efficacy of a single evening dose of syrup containing paracetamol, dextromethorphan hydrobromide, doxylamine succinate and ephedrine sulfate in subjects with multiple common cold symptoms. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2007;45(4):230‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schachtel 1999 {published data only}

- Schachtel BP, Loose I. Gastrointestinal tolerability of single doses of acetylsalicylic acid, paracetamol, and placebo in adults with upper respiratory tract infection. Gut 1999;45(Suppl V):A95. [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Arroll 2010

- Arroll B, Kenealy T. Antibiotics for the common cold and acute purulent rhinitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000247.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Botting 2000

- Botting RM. Mechanism of actions of acetaminophen: is there a cyclooxygenase 3?. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2000;31(Suppl):202‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bower 2007

- Bower W, Johns M, Margolis H, Williams IT, Bell BP. Population based surveillance for acute liver failure. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2007;102:2459‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Burnett 2006

- Burnett I, Schachtel B, Sannerk Bey M, Grattan T, Littlejohn S. Onset of analgesia of a paracetamol tablet containing sodium bicarbonate: a double‐blind placebo‐controlled study in adult patients with sore throat. Clinical Therapeutics 2006;28:1273‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

De Sutter 2012

- Sutter AIM, Driel ML, Kumar AA, Lesslar O, Skrt A. Oral antihistamine‐decongestant‐analgesic combinations for the common cold. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004976.pub3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Eccles 2006b

- Eccles R. Efficacy and safety of over‐the‐counter analgesics in the treatment of common cold and flu. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 2006;31(4):309‐19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fendrick 2003

- Fendrick AM, Monto AS, Nightengale B, Sarnes M. The economic burden of non‐influenza‐related viral respiratory tract infection in the United States. Archives of Internal Medicine 2003;163:487‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gwaltney 2002

- Gwaltney JM, Winther B, Patrie JT, Hendley JO. Combined antiviral‐antimediator treatment for the common cold. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2002;186(2):147‐54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Heikkinen 2003

- Heikkinen T, Jarvinen A. The common cold. Lancet 2003;361:51‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hemilä 2013

- Hemilä H, Chalker E. Vitamin C for preventing and treating the common cold. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000980.pub4] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2003

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. BMJ 2003;327(7414):557‐60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC (editors). Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

Kim 2009

- Kim Sy, Cho HM, Hwang YW, Moon YS, Chang YJ. Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs for the common cold. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006362.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lefebvre 2011

- Lefebvre C, Manheimer E, Glanville J (editors). Chapter 6: Searching for studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011.

Linde 2008

- Linde K, Barrett B, Bauer R, Melchart D, Woelkart K. Echinacea for preventing and treating the common cold. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000530.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lissiman 2012

- Lissiman E, Bhasale AL, Cohen M. Garlic for the common cold. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006206.pub3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lucas 2005

- Lucas R, Warner TD, Vojnovic I, Mitchell JA. Cellular mechanisms of acetaminophen: role of cyclooxygenase. Journal of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 2005;19:625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mizoquchi 2007

- Mizoquchi H, Wilson Jerdack GR, Hull JD, Goodale M, Grender JM, Tyler BA. Efficacy of a single evening dose of syrup containing paracetamol, dextromethorphan, hydrobromide, doxylamine succinate and ephedrine sulfate in subjects with multiple common cold symptoms. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2007;45:230‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2003

- Moore N, LeParc JM, Ganse E, Wall R, Schneid H, Cairns R. Tolerability of ibuprofen,aspirin and paracetamol for the treatment of cold and flu symptoms and sore throat pain. International Journal of Clinical Practice 2002;56:732‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pickering 2006

- Pickering G, Loriot MA, Libert F, Eschalier A, Beaune P, Dubray C. Analgesic effect of acetaminophen in humans: first evidence of a central serotonergic mechanism. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2006;79:371‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Reece 2008

- Reece A, Davles CG, Maher M, Hancock J. A systematic review of paracetamol for non‐specific low back pain. European Spine Journal 2008;1423:1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2012 [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.2. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2012.

Schachtel 1988

- Schachtel BP, Fillingim JM, Thoden WR, Lane AC, Baybutt RI. Sore throat pain in the evaluation of mild analgesics. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 1988;44:704‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shaheen 2000

- Shaheen SO, Sterne JAC, Songhurst CE, Burnery PGJ. Frequent paracetamol use and asthma in adults. Thorax 2000;55:266‐70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shen 2006

- Shen H, Sprott H, Aeschlimann A, Gay RE, Michel BA, Gay S. Analgesic action of acetaminophen in symptomatic osteoarthritis of the knee. Rheumatology 2006;45:765‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Singh 2011a

- Singh M. Heated, humidified air for the common cold. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 5. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001728.pub3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Singh 2011b

- Singh M, Das RR. Zinc for the common cold. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001364.pub3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Treanor 2000

- Treanor JJ, Hayden FG. Viral infection. Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. Philadelphia, USA: WB Saunders, 2000. [Google Scholar]

Zhang 2009

- Zhang X, Wu T, Zhang J, Yan Q, Xie L, Liu GJ. Chinese medicinal herbs for the common cold. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004782.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]