Abstract

目的

了解2017年天津地区急性胃肠炎患儿诺如病毒(NoV)分子流行病学特征。

方法

收集2017年1~12月天津市儿童医院疑似由病毒感染引起的急性胃肠炎患儿的粪便标本758份,采用荧光定量RT-PCR方法对NoV进行初筛,运用传统RT-PCR方法对阳性标本的衣壳蛋白VP1区进行基因扩增、基因测序和鉴定基因型别。

结果

758份粪便标本中检出GⅡ型NoV 241份,阳性率为31.8%。对阳性标本进行衣壳蛋白VP1区测序,发现GⅡ型标本中以GⅡ.4亚型为主,占28.6%(69/241);其次为GⅡ.3亚型,占21.2%(51/241);GⅡ.2亚型占10.0%(24/241);其他亚型占7.5%(18/241)。不同年龄组间NoV检出率差异有统计学意义(P=0.018),其中1~ < 4岁组阳性检出率最高(37.3%)。不同季节的NoV检出率差异具有统计学意义(P < 0.001),其中冬季为高发季节(48.1%)。27份(3.6%)标本存在NoV和轮状病毒(RtV)的混合感染。

结论

NoV是2017年天津地区该组急性胃肠炎患儿的主要病原体之一;GⅡ基因型特别是GⅡ.4亚型是流行优势毒株;NoV感染在4岁内儿童更为常见;冬季为流行高峰;存在与RtV混合感染的情况。

Keywords: 急性胃肠炎, 诺如病毒, 基因型, 儿童

Abstract

Objective

To investigate the molecular epidemiological characteristics of norovirus (NoV) among children with acute gastroenteritis in Tianjin in 2017.

Methods

A total of 758 stool specimens were collected from the children with acute gastroenteritis possibly caused by viral infection in Tianjin Children's Hospital between January and December, 2017. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was used for primary screening of NoV, and conventional RTPCR was used for gene amplification, sequencing and genotype identification of the VP1 region of capsid protein in positive specimens.

Results

Among the 758 specimens, 241 (31.8%) were found to have GⅡ NoV. Sequencing of the VP1 region of capsid protein in positive specimens showed that among the 241 specimens with GⅡ NoV, 69 (28.6%) had GⅡ.4 subtype, 51 (21.2%) had GⅡ.3 subtype, 24 (10.0%) had GⅡ.2 subtype, and 18 (7.5%) had other subtypes. There was a significant difference in NoV detection rate between different age groups (P=0.018), and the 1- < 4 years group had the highest NoV detection rate (37.3%). There was also a significant difference in NoV detection rate across seasons (P < 0.001), and there was a highest NoV detection rate in winter (48.1%). Twenty-seven children (3.6%) had co-infections with NoV and rotavirus.

Conclusions

NoV is one of the major pathogens of the children with acute gastroenteritis from Tianjin in 2017. GⅡ genotype, especially GⅡ.4 subtype, is the prevalent strain. NoV infection is commonly seen in children less than 4 years and reaches the peak in winter. Some children are found to have co-infections with rotavirus.

Keywords: Acute gastroenteritis, Norovirus, Genotype, Child

诺如病毒(norovirus, NoV)是引起暴发性和散发性非细菌性胃肠炎的重要病原体,全世界约有20%急性胃肠炎病例是由NoV引起[1]。NoV属于杯状病毒科诺如病毒属,其基因组全长约7.5 bp。NoV分为5个基因组(GI~V),可感染人类的有GI、GII和GIV组毒株[2],其中以GII型感染最为常见,且每组病毒又包含多种基因型。人类NoV基因组由3个开放阅读框(open reading frames, ORFs)组成,ORF1编码6个非结构蛋白,其中包括RNA聚合酶(RNA dependent RAN polymerase, RdRp),ORF2和ORF3分别编码主要衣壳蛋白VP1及小衣壳蛋白VP2[3]。研究表明NoV通常可导致轻微和自限性疾病,典型临床表现为急性腹泻、发热和呕吐等症状,严重者可导致死亡[4]。NoV具有高度的变异性,持续监测NoV感染性急性胃肠炎的病原学特征及基因型的演化情况有助于NoV感染的预防和控制。本研究对天津地区住院急性胃肠炎患儿中NoV的分子流行病学特征进行分析。

1. 资料与方法

1.1. 研究对象

收集2017年1~12月期间就诊于天津市儿童医院疑似由病毒感染引起的急性胃肠炎患儿的粪便标本758份,其中男469例,女289例,年龄1个月至12岁。纳入标准:(1)24 h排便≥3次,且大便性状有改变(呈稀便、水样便等),大便常规镜检白细胞 < 15个,未见红细胞;(2)24 h排便 < 3次,但伴有大便性状改变和呕吐症状或以呕吐为主要症状[5]。

1.2. 样本的采集和病毒RNA提取

采集患儿入院3 d内的粪便标本于专用无菌便盒中,取约500 μL大便标本,加生理盐水至1 L,配置50%的混悬液,充分震荡混匀后,离心10 min(12 000 r/min),严格按照QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit的操作说明进行病毒RNA提取。

1.3. 病毒初筛

应用湖北朗德医疗科技有限公司生产的NoV核酸检测试剂盒(PCR-荧光探针法)对临床样本进行NoV的初筛,所用仪器为ABI7500。反应体系:反应液35.8 μL,酶4.2 μL,待测样本RNA 10 μL,总体系50 μL。扩增条件:42℃ 30 min,95℃ 3 min,95℃ 10 s,60℃ 1 min,40个循环。结果判断:如果扩增曲线呈S型且Ct值≤36,则结果为阳性;如果扩增曲线不呈明显S型或36 < Ct值< 40,则对样本进行复检,若复检结果仍为36 < Ct值< 40,则结果为阴性;如果扩增曲线不呈S型、Ct值显示为“undet”或无Ct值,则结果为阴性。采用金标法检测轮状病毒(rotavirus, RtV)和腺病毒(adenovirus, ADV)(艾博生物医药杭州有限公司)。

1.4. VP1区序列扩增及测序

首先将样本RNA用随机六聚体引物逆转录合成cDNA(Quant cDNA第一链合成试剂盒,天根生化科技有限公司),保存-20℃备用。随后应用试剂盒(TaKaRa Premix Taq,大连宝生物有限公司)对NoV初筛为阳性的标本进行VP1区的扩增,扩增引物参照文献[6]。反应体系:10 × Ex Taq buffer 2.5 μL,dNTPs(2.5 mM)2 μL,上下游引物(10 pmol/μL)1 μL,Ex Taq hot start酶0.25 μL(5 U/μL),模板5 μL,去离子水补至25 μL。反应条件:94℃预变性3 min;94℃变性30 s,50℃退火30 s,72℃延伸1 min,40个循环;最后72℃延伸7 min。PCR产物用1.5%琼脂糖凝胶电泳进行鉴定,将阳性扩增产物送至苏州金唯智生物科技有限公司测序,并在GenBank上比对。

1.5. 生物信息学分析

采用DNAStar软件对测定的序列进行同源性分析;运用MEGA 5.05软件进行多序列比对,使用邻近法(neighbor-joining)、Kimura2-parameter模型构建亲缘进化树,通过Bootstrap值评估建树的可靠性。

1.6. 统计学分析

使用SPSS 19.0软件进行统计学处理与分析。计数资料用频数和百分率(%)表示,组间比较采用χ2检验,P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2. 结果

2.1. 病原学检测结果

荧光定量PCR定性检测显示,在758份急性胃肠炎患儿的粪便标本中检测出NoV阳性241份,阳性率为31.8%,均为GII型,未检测出GI型。对NoV初筛为阳性标本的VP1区进行测序分析,发现GII.4亚型的阳性率最高,占28.6%(69/241);其次为GII.3亚型,占21.2%(51/241);GII.2亚型占10.0 %(24/241);其他亚型占7.5%(18/241)。尚有78份阳性标本未成功测序分型。

金标法检测粪便标本显示,RtV的阳性率为15.6%(118/758),ADV阳性率为1.3%(10/758)。其中NoV和RtV混合感染27例,混合感染率为3.6%(27/758);NoV和ADV混合感染1例,混合感染率为0.1%(1/758)。

2.2. 临床资料分析

经NoV或RtV检测为阳性的患儿临床上均主要表现为发热(> 38℃)、呕吐、腹泻、腹痛和脱水等症状。241例NoV检测阳性的患儿中147例(61.0%)出现发热;呕吐126例(52.3%);腹泻149例(61.8%);腹痛22例(9.1%);脱水10例(4.1%)。而118例RtV检测阳性的患儿中,发热93例(78.8%);呕吐84例(71.2%);腹泻92例(78.0%);腹痛5例(4.2%);脱水8例(6.8%)。与RtV感染的患儿相比,NoV感染的患儿较少出现发热、呕吐和腹泻等症状(P < 0.05)。27例NoV和RtV混合感染患儿的性别、年龄及病情严重程度与NoV或RtV单独感染的患儿相比,差异均无统计学意义。

2.3. NoV感染患儿的性别和年龄分布

241例NoV阳性患儿中,4岁以内占87.6%(211/241)。不同年龄组的NoV检出率差异有统计学意义(χ2=10.083,P=0.018),其中1~ < 4岁组检出率最高(37.3%),见表 1。男女患儿的NoV检出率差异无统计学意义[30.9%(145/469)vs 33.2%(96/289);χ2=0.437,P=0.509]。

1.

各年龄组患儿粪便标本中NoV检出情况[n(%)]

| 年龄分组(岁) | n | 阳性检出 |

| < 1 | 277 | 75(27.1) |

| 1~ | 365 | 136(37.3) |

| 4~ | 68 | 19(27.9) |

| 8~12 | 48 | 11(22.9) |

| χ2值 | 10.083 | |

| P值 | 0.018 |

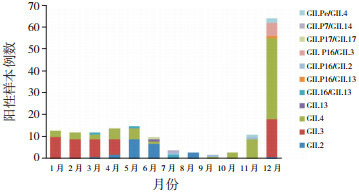

2.4. NoV的季节分布

不同季节NoV阳性检出率差异具有统计学意义(χ2=68.837,P < 0.001),其中冬季检出率最高,12月为检出高峰,见表 2和图 1。如图 1所示,1~4月主要以GII.3为主,占66.7%(34/51);5~8月以GII.2为主,占62.5%(20/32);9~12月以GII.4为主,占62.5%(50/80)。此外,发现18例重组株,其中GII.P16/GII.3占6例,且均分布在12月;其次GII.P16/GII.2、GII.Pe/GII.4、GII.16/GII.13各3例,散发在不同月份。

2.

NoV检出的季节分布[n(%)]

| 季节 | n | 阳性检出率 |

| 春季(3~5月) | 210 | 45(21.4) |

| 夏季(6~8月) | 148 | 22(14.9) |

| 秋季(9~11月) | 136 | 47(34.6) |

| 冬季(1月、2月、12月) | 264 | 127(48.1) |

| χ2值 | 68.837 | |

| P值 | < 0.001 |

1.

2017年NoV检出的时间分布

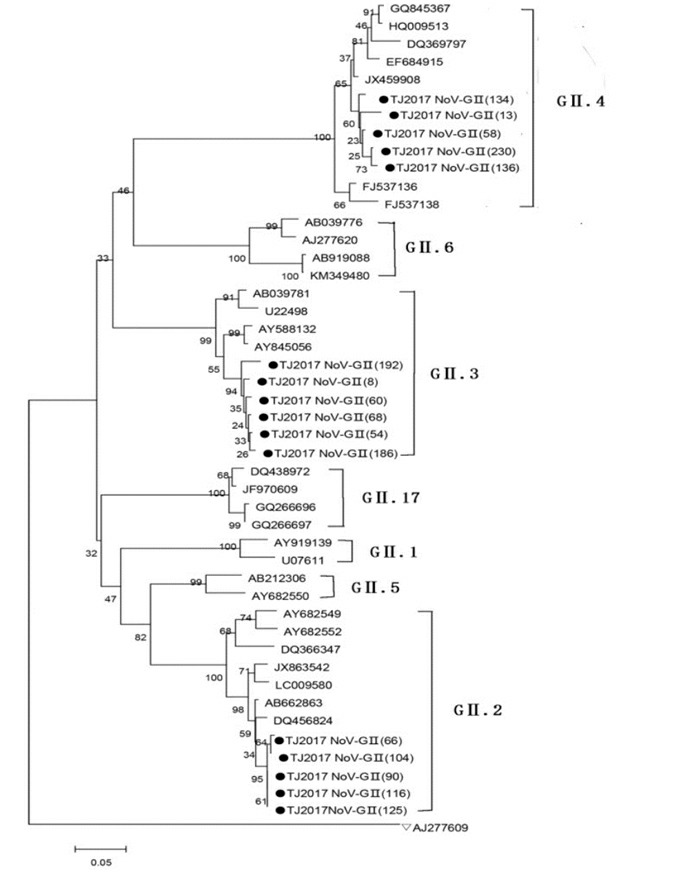

2.5. 进化树分析

本研究随机选取16株测序成功的NoV,与GenBank数据库中参考株构建分子遗传进化树。结果显示,本次调查的毒株衣壳蛋白VP1区核苷酸序列高度同源且聚集成簇,分别分布在GII.2型、GII.3型和GII.4型的分枝上,见图 2。其中5株为NoV GII.2型,核苷酸序列的同源性为97.7%~99%,与参考株DQ456824核苷酸序列的同源性为94.7%~98.7%;6株为NoV GII.3型,核苷酸序列的同源性为91.9%~98.4%,与参考株AY845056核苷酸序列的同源性为91.1%~98.4%;5株为NoV GII.4型,核苷酸序列的同源性为92.5%~96.5%,与参考株JX459908核苷酸序列的同源性为93.7%~99.3%。

2.

NoV衣壳蛋白区系统进化树

该图采用临近法制作NoV衣壳蛋白VP1区的基因进化树。●表示本研究测序的16株NoV序列,▽表示GI参考株作为外群,其他参考株均来自GenBank。

3. 讨论

NoV感染是引发急性胃肠道疾病最常见的病原体,是全世界公认所有年龄段急性胃肠炎散发和暴发的主要病因[7-8]。变异和同源重组是导致NoV基因和抗原性具有多样性的主要原因,以致于不同地区之间可存在相同或不同的优势流行毒株,因此NoV分子流行病学监测对于疾病的预防与控制至关重要。

自1995年首次在婴幼儿腹泻患儿粪便中检测到NoV以来,全世界各地陆续报道了儿童NoV感染的情况。如近年文献显示,南京地区腹泻婴幼儿NoV检出率为15.2%[5],苏州地区急性胃肠炎患儿NoV检出率为26.9%[9],美国亚特兰大地区急性胃肠炎患儿中也检出了NoV [10]。本研究收集2017年1~12月因疑似病毒感染所致急性胃肠炎住院患儿粪便标本758份,荧光定量PCR检测显示NoV阳性率为31.8%(241/758),提示该病毒感染可能是造成儿童急性胃肠炎的主要原因之一。本研究中,NoV阳性患儿主要集中在4岁以内患儿,占比87.6%(211/241),其原因可能与患儿年龄小,免疫力低有关,这与以往研究结果相符[11]。尚未发现NoV检出率在不同性别间存在差异,这与以往研究结果一致[12]。NoV散发感染虽然常年均可发生,但相关文献报道台湾地区NoV流行季节是冬季或寒冷季节[13];韩国其流行季节在晚秋到春季[14]。本研究显示冬季NoV的检出率高于其他季节。这说明NoV感染存在明显的季节性,其原因可能是干冷的气候有利于NoV的活动[15]。

相关研究表明,NoV GII型比GI型的传播更为广泛[16-17]。虽然GII和GI型均存在多种亚型,但GII.4型是造成全球急性胃肠炎暴发的优势流行株[18],其可能与GII.4的基因型抗原漂移和基因重组导致进化速度快有关[19]。有研究显示,NoV GII.P16/GII.2重组株是引起2016~2017年湖州地区急性胃肠炎暴发的主要原因[20]。随着NoV的不断进化,出现了多种GII.P16的重组株,目前发现的有GII.P16/GII.16, GII.P16/GII.2, GII.P16/GII.3, GII.P16/GII.13以及GII.P16/GII.4等。本组病例以GII.4型为主,占28.6%(69/241)。此外在本组病例中,还检测到了NoV 7种重组株,其中以GII.P16/GII.3为主。在孟加拉[21]、巴西[22]和西班牙[23]等地也曾检出过GII.P16/GII.3重组株。由此可见,GII.4基因型是导致天津地区该组病例NoV感染的主要流行株,与既往研究结果一致[24-25],而既往天津地区从未在散发或暴发病例中检测到重组株GII.P16/GII.3,提示本地区除了要对GII.4进行重点检测外,也要关注NoV重组株的流行情况。

综上所述,本研究通过对来自天津地区的急性胃肠炎患儿的粪便标本进行检测,发现NoV的阳性率为31.8%,且NoV感染具有明显的季节性,这一发现有利于以后根据其季节流行特点进行重点监测。随后通过对阳性标本进行测序发现,主要以GII.4为主,其次为GII.2、GII.3,此外还检测到7种重组毒株。通过对NoV VP1区基因进行进化树分析显示,本研究中GII.2、GII.3、GII.4与参考株具有较高的同源性,说明NoV在全球范围流行暴发的过程中存在着不同基因型持续共同进化和循环,进一步发生重组分布到各地区。因此,加强对NoV感染情况的检测和对其开展分子病原学研究,以及完善NoV感染性急性胃肠炎监测网络对于疾病的预防和控制具有十分重要的意义。

Biography

方玉莲, 女, 硕士研究生, 研究实习员

Funding Statement

天津市卫生局科技基金(2011KZ33;2015KZ038)

References

- 1.Ahmed SM, Hall AJ, Robinson AE, et al. Global prevalence of norovirus in cases of gastroenteritis:a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(8):725–730. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70767-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karst SM, Zhu S, Goodfellow IG. The molecular pathology of noroviruses. J Pathol. 2015;235(2):206–216. doi: 10.1002/path.4463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hernandez JM, Silva LD, Junior ECS, et al. Molecular epidemiology and temporal evolution of norovirus associated with acute gastroenteritis in Amazonas state, Brazil. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):147. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3068-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall AJ, Wikswo ME, Manikonda K, et al. Acute gastroenteritis surveillance through the National Outbreak Reporting System, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(8):1305–1309. doi: 10.3201/eid1908.130482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.蒋 翠莲, 叶 莉莉, 许 烨, et al. 南京地区腹泻婴幼儿新型诺如病毒GⅡ.17变异株的检出及基因分析. http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-ZHYY201620051.htm 中华医院感染学杂志. 2016;26(20):4717–4720. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kojima S, Kageyama T, Fukushi S, et al. Genogroup-specific PCR primers for detection of Norwalk-like viruses. J Virol Methods. 2002;100(1-2):107–114. doi: 10.1016/S0166-0934(01)00404-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain S, Thakur N, Grover N, et al. Prevalence of rotavirus, norovirus and enterovirus in diarrheal diseases in Himachal Pradesh, India. Virusdisease. 2016;27(1):77–83. doi: 10.1007/s13337-016-0303-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andrade JSR, Fumian TM, Leite JPG, et al. Detection and molecular characterization of emergent GⅡ.P17/GⅡ.17 Norovirus in Brazil, 2015. Infect Genet Evol. 2017;51:28–32. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fu JG, Ai J, Zhang J, et al. Molecular epidemiology of genogroup Ⅱ norovirus infection among hospitalized children with acute gastroenteritis in Suzhou (Jiangsu, China) from 2010 to 2013. J Med Virol. 2016;88(6):954–960. doi: 10.1002/jmv.v88.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yi J, Wahl K, Sederdahl BK, et al. Molecular epidemiology of norovirus in children and the elderly in Atlanta, Georgia, United States. J Med Virol. 2016;88(6):961–970. doi: 10.1002/jmv.v88.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahman M, Rahman R, Nahar S, et al. Norovirus diarrhea in Bangladesh, 2010-2014:prevalence, clinical features, and genotypes. J Med Virol. 2016;88(10):1742–1750. doi: 10.1002/jmv.v88.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan MC, Leung TF, Chung TW, et al. Virus genotype distribution and virus burden in children and adults hospitalized for norovirus gastroenteritis, 2012-2014, Hong Kong. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11507. doi: 10.1038/srep11507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang SY, Hwang KP, Wu FT, et al. Epidemiology and clinical peculiarities of norovirus and rotavirus infection in hospitalized young children with acute diarrhea in Taiwan, 2009. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2010;43(6):506–514. doi: 10.1016/S1684-1182(10)60078-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park K, Yeo S, Jeong H, et al. Updates on the genetic variations of norovirus in sporadic gastroenteritis in Chungnam Korea, 2009-2010. http://d.old.wanfangdata.com.cn/OAPaper/oai_pubmedcentral.nih.gov_3312829. Viro1 J. 2012;9:29. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopman B, Armstrong B, Atchison C, et al. Host, weather and virological factors drive norovirus epidemiology:time-series analysis of laboratory surveillance data in England and Wales. PLoS One. 2009;4(8):e6671. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rohayem J. Norovirus seasonality and the potential impact of climate change. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15(6):524–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel MM, Widdowson MA, Glass RI, et al. Systematic literature review of role of noroviruses in sporadic gastroenteritis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(8):1224–1231. doi: 10.3201/eid1408.071114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoa Tran TN, Trainor E, Nakagomi T, et al. Molecular epidemiology of noroviruses associated with acute sporadic gastroenteritis in children:global distribution of genogroups, genotypes, and GⅡ.4 variants. http://med.wanfangdata.com.cn/Paper/Detail/PeriodicalPaper_PM23218993. J Clin Virol. 2013;56(3):185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White PA. Evolution of norovirus. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(8):741–745. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han J, Wu X, Chen L, et al. Emergence of norovirus GⅡ.P16-GⅡ.2 strains in patients with acute gastroenteritis in Huzhou, China, 2016-2017. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):342. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3259-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nahar S, Afrad MH, Matthijnssens J, et al. Novel intergenotype human norovirus recombinant GⅡ.P16/GⅡ.3 in Bangladesh. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;20:325–329. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fumian TM, da Silva Ribeiro de Andrade J, Leite JP, et al. Norovirus recombinant strains isolated from gastroenteritis outbreak in Southern Brazil, 2004-2011. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0145391. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arana A, Cilla G, Montes M, et al. Genotypes, recombinant forms, and variants of norovirus GⅡ. http://cn.bing.com/academic/profile?id=d555ed3f78ffc24d7e1d53c11b763589&encoded=0&v=paper_preview&mkt=zh-cn. 4 in Gipuzkoa (Basque Country, Spain) 2009;9(6):e98875. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Y, Li Z, Han D, et al. Viral agents associated with acute diarrhea among outpatient children in southeastern China. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(7):e285–e290. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31828c3de4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zou W, Cui D, Wang X, et al. Clinical characteristics and molecular epidemiology of noroviruses in outpatient children with acute gastroenteritis in Huzhou of China. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0127596. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]