Abstract

Schinzel-Giedion综合征(SGS)是非常罕见的一种常染色体显性遗传病。主要临床特征为严重的发育迟缓、特殊面容以及多发畸形。本文报道1例14个月男性患儿,主要表现为发育落后、特殊面容:前额凸,面中部回缩,眼距宽,耳位低,鼻孔上翻,小下颌;同时伴有多发畸形:脑发育不良、髋关节脱位、隐睾等。染色体核型分析及拷贝数变异均提示无明显异常,全外显子基因测序显示患儿携带SETBP1基因c.2602G > A(p.D868N)新生杂合错义突变,因此确诊为SGS。该患儿的肌阵挛发作经过丙戊酸钠治疗得到较好控制,其语言发育在康复治疗后也得到轻度改善。临床医师应提高对SGS这一类罕见病的识别能力,对于特殊面容伴发育障碍及多发畸形的患者要考虑到该病,基因检测可提高诊断能力。

Keywords: Schinzel-Giedion综合征, SETBP1, 特殊面容, 发育落后, 儿童

Abstract

Schinzel-Giedion syndrome is a rare autosomal dominant genetic disease and has the clinical features of severe delayed development, unusual facies, and multiple congenital malformations. In this case report, a 14-month-old boy had the clinical manifestations of delayed development, unusual facies (prominent forehead, midface retraction, hypertelorism, low-set ears, upturned nose, and micrognathia), and multiple congenital malformations (including cerebral dysplasia, dislocation of the hip joint, and cryptorchidism). The karyotype analysis and copy number variations showed no abnormalities, and whole exon sequencing showed a de novo heterozygous missense mutation, c.2602G > A (p. D868N), in SETBP1 gene. Therefore, the boy was diagnosed with Schinzel-Giedion syndrome. Myoclonic seizures in this boy were well controlled by sodium valproate treatment, and his language development was also improved after rehabilitation treatment. Clinical physicians should improve their ability to recognize such rare diseases, and Schinzel-Giedion syndrome should be considered for children with unusual facies, delayed development, and multiple malformations. Gene detection may help with the diagnosis of this disease.

Keywords: Schinzel-Giedion syndrome, SETBP1, Unusual facies, Delayed development, Child

1. 病例介绍

患儿,男,14月龄,因发育落后12个月就诊。患儿2月龄被发现吸奶无力,肌张力低;4月龄时俯卧抬头不能,扶立时双下肢不支撑,眼睛不追物,手不主动抓物,眼球水平震颤;8月龄时不能独坐,无大笑;14月龄仍不能发单音,不能竖头,不能独站,不认识爸妈。

患儿生后29 h因呼吸暂停住院。查头颅B超提示左侧脑室下角增宽;心脏彩超示动脉导管未闭、卵圆孔未闭(复查心脏彩超示动脉导管于7天龄闭合,卵圆孔于4月龄闭合);阴囊B超显示双侧附睾与睾丸过小;甲状腺功能:TSH 9.45 IU/mL(参考值:0.25~7.31 IU/mL),TT3 56.5 ng/dL(参考值:70~220 ng/dL);直接胆红素17.2 µmol/L(参考值:0~6 µmol/L),总胆红素245.9 µmol/L(参考值:5.1~17.1 µmol/L);血氨、血乳酸、血糖未见异常;血、尿串联质谱分析未见异常;染色体核型分析:46 XY。诊断“早产儿、新生儿呼吸暂停、新生儿高胆红素血症、新生儿暂时性甲状腺功能减退症、动脉导管未闭、卵圆孔未闭”,口服甲状腺素片(每次25 μg、每日1次),2周后复查甲状腺功能正常。1月龄时头颅MRI显示双侧大脑白质长T1、长T2信号,内囊后肢髓鞘化不明显,左侧侧脑室扩张。2月龄复查关节B超提示先天性髋关节脱位。3月龄复查头部MRI提示胼胝体薄,侧脑室扩大、不规则,脑室旁白质少,左侧额叶脑沟向内深达脑实质旁,左外侧裂增宽。

患儿系第一胎第一产,36+3周顺产出生,出生体重1 750 g,出生时无窒息。患儿母亲妊娠中期有胎动减少、脐带水肿。家族史无特殊。

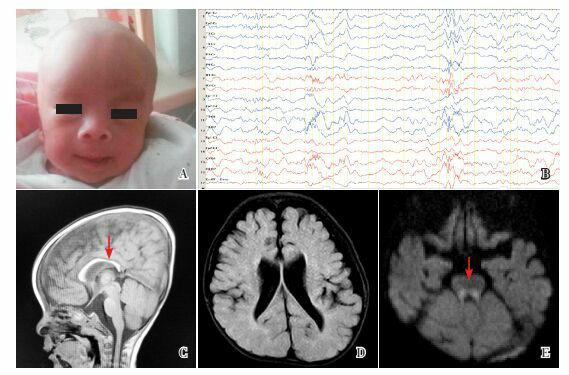

体格检查:神清,反应欠佳,双眼球水平震颤。头围41.5 cm(-3 SD),前囟已闭,特殊面容(图 1A):前额凸,眼距宽,鼻孔上翻,面中部回缩,腭弓高,耳位低,小下颌。脊柱后凸。四肢肌力Ⅲ级,肌张力不高,小手足,右手通贯手。双侧睾丸未降。

1.

A:患儿的特殊面容 前额凸,眼距宽,鼻孔上翻,面中部回缩,耳位低,小下颌。B:患儿的睡眠脑电图 两侧有较多尖慢波、棘慢波、多棘慢波发放伴阵发,两后部明显。C~E:患儿头部磁共振 胼胝体偏薄,如图C(T1序列)箭头所示;侧脑室增宽(图D,T2序列);脑干背侧异常信号,如图E(弥散序列)箭头所示。

辅助检查:睡眠脑电图(图 1B)示较多尖慢波、棘慢波、多棘慢波发放伴阵发,两后部明显;头部磁共振(图 1C~E)显示胼胝体薄,脑发育不良,侧脑室增宽,脑干背侧局灶性异常信号。腹部B超显示双侧睾丸分别位于双侧腹股沟管近内环处;肌电图提示肌源性损害,累及上下肢;基因芯片未见异常。

2. 诊断思维

患儿14月龄,主要特征为语言、运动发育落后,特殊面容及多发畸形。宫内感染可导致面部畸形与发育落后,但患儿出生史及母孕史无特殊,TORCH检测阴性,无宫内感染和出生窒息缺氧等依据。患儿起病年龄早,应注意代谢性疾病导致的发育落后,但患儿新生儿期血尿串联质谱未见异常,毛发无异常,小便无异味,血氨、血乳酸、血糖未见异常,无代谢性疾病的线索。特殊面容伴多系统畸形也需注意21三体综合征、18三体综合征等染色体疾病,但患儿的高分辨率染色体核型分析结果为阴性。染色体的结构异常如微缺失或重复综合征,如4p-(Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome)等可导致特殊的面部畸形以及先天性心脏病和泌尿系统畸形,但患儿无特征性的“希腊盔甲”面容,且患儿的基因芯片结果也提示无明显异常。另外,与印记基因相关的疾病如Prader-Willi综合征(PWS)和Angelman综合征(AS)也可导致特殊面容与发育落后,但是患儿无肥胖,不符合PWS的诊断,也未观察到AS特征性的微笑或爆发性大笑,无大嘴和大下颌,不符合AS诊断标准。男性患儿还应注意脆性X综合征可能,但此病睾丸增大,与本例特点不符。本例患儿起病年龄小,表型复杂,不能排除与遗传有关的疾病,需进一步行全外显子基因测序。

3. 进一步检查

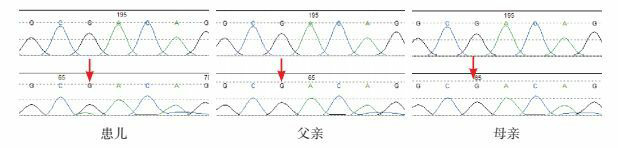

经家长知情同意,对先证者及其父母进行全外显子测序(复旦大学附属儿科医院与明码生物科技联合实验室检测),显示患儿SETBP1基因存在c.2602G > A(p.D868N)杂合错义突变。经Sanger验证,确定该突变为新发变异(图 2)。

2.

患儿家系SETBP1基因测序结果

患儿SETBP1基因存在c.2602G > A(p.D868N)突变(突变位点如箭头所示)。患儿父母该位点未见异常。

4. 确诊依据

根据患儿临床特征及基因检测结果,确诊为Schinzel-Giedion综合征(Schinzel-Giedion syndrome, SGS)。诊断依据:(1)发育落后伴特殊面容:前额凸,面中部回缩,眼距宽;(2)先天性髋关节脱位;(3)基因检测发现明确的SETBP1基因c.2602G > A(p.D868N)杂合错义突变。

5. 临床经过

Schinzel-Giedion综合征尚缺乏有效的治疗手段。患儿16月龄首次出现惊厥发作(表现为全身肌阵挛),予丙戊酸钠(3 mL Bid)口服,1周后发作好转;22月龄时因惊厥控制不佳,调整剂量(4 mL Bid),至今无发作;22月龄复查头围43.8 cm(-3 SD),查全身骨扫描未见异常;24月龄行双侧睾丸固定,复查甲状腺功能正常,停用甲状腺素片。目前康复训练中,语言能力有进步,全身肌张力仍然较低。

6. 讨论

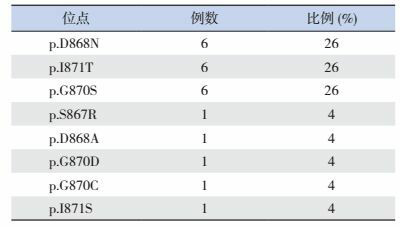

Schinzel-Giedion综合征(OMIM #269150)是一种非常罕见的常染色显性遗传病,主要临床特征为严重发育迟缓,特殊面容以及多种先天畸形。特殊面容包括前额凸,眼距增宽,鼻梁塌,鼻孔上翻,颈部短小。该疾病于1978年由Schinzel和Giedion首次报道[1]。Hoischen等[2]在2010年首次报道在已行基因诊断的SGS患者中,SETBP1检出阳性率为95.8%(23/24)。目前已报道的SGS患儿SETBP1突变全部为错义突变,见表 1[2-9]。本例患儿的突变c.2602G > A(p.D868N)国外已报道5例,可能为该疾病的热点突变[2, 8]。

1.

已报道的23例Schinzel-Giedion综合征患儿的SETBP1突变位点

|

SETBP1位于18q21,编码1 542个氨基酸,大小为170 kb,该基因在全身广泛表达[10]。目前该基因突变的分子机制仍然不清楚。Hoischen等[2]运用Sanger测序在8例患儿中检测到SETBP1突变,这些变异都发生在高度保守的区域,而且指出SETBP1基因突变的致病原因是其功能增强。Filges等[11]报道2例包含SETBP1基因的18q12.3微缺失综合征患儿,发现SETBP1蛋白表达下降的病人主要表现为语言发育落后,与典型的SGS患者不同,这也进一步证实了Hoischen等的假说,但具体发病机制仍需更深入的探究。

惊厥发作也是SGS的重要表型,而且一般为药物难治性癫痫。日本学者曾报道2例SGS伴婴儿痉挛患者采用ACTH治疗,均无明显效果[12-13]。而文献报道,丙戊酸合联合拉莫三嗪,或左乙拉西坦联合苯巴比妥对SETBP1突变患儿的癫痫控制效果较好[6, 12]。本例患儿的肌阵挛经过丙戊酸钠治疗得到较好控制。

Lehman等[14]指出特殊面容合并肾盂积水或骨骼异常可以作为SGS的重要诊断依据。肾盂积水的发生率为79.2%(62/77)[6-8, 12],而骨骼异常的比例为85.7%(66/77)[8]。Carvalho等[8] 2015年报道的1例SGS患儿除特殊面容、神经系统受累之外,无肾脏与骨骼受累表现,但SETBP1基因Sanger测序为阳性,提示对于具有特殊面容伴神经系统受累的患者,应进行基因诊断排除SGS。

本例患儿新生儿期发现甲状腺功能减低,经过左旋甲状腺素治疗,甲状腺功能2岁恢复正常。目前SGS患儿中甲状腺功能异常的仅4例报道[4, 8, 12],因此尚不能确定与SGS的关系。Suphapeetiporn等[4]指出,尽管合并甲状腺功能减低的SGS患儿甲状腺功能可恢复正常,但发育障碍并不能得到改善。因此,SGS患儿的甲减是否为自限性或需治疗值得商榷。

近来的研究也揭示了SETBP1突变患儿中恶性肿瘤的发生率明显增高,包括畸胎瘤、生殖细胞、神经外胚层肿瘤等,大部分发生在骶尾部,对于化疗不敏感[7]。Matsumoto等[15] 2005年报道1例8岁SGS患者合并Wilms瘤。因此,对于SGS患儿应注意随访是否合并肿瘤性疾病。

SGS尚缺乏有效的治疗手段,预后较差,大部分患儿可能死于呼吸衰竭。Herenger等[3] 2015年报道的1例随访时间最长的15岁SGS患儿,其发育落后非常明显,长期卧床并且伴有脊柱侧凸、胸廓变性以及关节挛缩、肾脏结石,但其惊厥症状使用苯巴比妥联合拉莫三嗪得到了良好的控制。另外,López-González等[6]报道,物理治疗可以使SGS患儿的社交行为与运动能力得到改善。

7. 结语

Schinzel-Giedion综合征非常罕见,国内尚无相关报道,容易漏诊、误诊。本例是国内首报的经过分子诊断确诊的SGS患者。对于存在特殊面容伴发育迟缓及多系统畸形的患者要考虑到此病,必要时进行基因诊断。随着对该疾病认识的深入,SGS基因型与表型之间的关系以及发病机制也将被揭示,为患者提供遗传咨询和有效的治疗手段。

Biography

路通, 男, 硕士研究生

Funding Statement

科技部重大专项基金(2016YFC0904400)

References

- 1.Schinzel A, Giedion A. A syndrome of severe midface retraction, multiple skull anomalies, clubfeet, and cardiac and renal malformations in sibs. Am J Med Genet. 1978;1(4):361–375. doi: 10.1002/(ISSN)1096-8628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoischen A, van Bon BW, Gilissen C, et al. De novo mutations of SETBP1 cause Schinzel-Giedion syndrome. Nat Genet. 2010;42(6):483–485. doi: 10.1038/ng.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herenger Y, Stoetzel C, Schaefer E, et al. Long term follow up of two independent patients with Schinzel-Giedion carrying SETBP1 mutations. Eur J Med Genet. 2015;58(9):479–487. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suphapeetiporn K, Srichomthong C, Shotelersuk V. SETBP1 mutations in two Thai patients with Schinzel-Giedion syndrome. Clin Genet. 2011;79(4):391–393. doi: 10.1111/cge.2011.79.issue-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ko JM, Lim BC, Kim KJ, et al. Distinct neurological features in a patient with Schinzel-Giedion syndrome caused by a recurrent SETBP1 mutation. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29(4):525–529. doi: 10.1007/s00381-013-2047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.López-González V, Domingo-Jiménez MR, Burglen L, et al. Schinzel-Giedion syndrome: a new mutation in SETBP1. An Pediatr (Barc) 2015;82(1):e12–e16. doi: 10.1016/j.anpedi.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kishimoto K, Kobayashi R, Yonemaru N, et al. Refractory sacrococcygeal germ cell tumor in Schinzel-Giedion syndrome. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2015;37(4):e238–e241. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carvalho E, Honjo R, Magalhães M, et al. Schinzel-Giedion syndrome in two Brazilian patients: Report of a novel mutation in SETBP1 and literature review of the clinical features. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272097818_Schinzel-Giedion_Syndrome_in_Two_Brazilian_Patients_Report_of_a_Novel_Mutation_in_SETBP1_and_Literature_Review_of_the_Clinical_Features. Am J Med Genet A. 2015;167A(5):1039–1046. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takeuchi A, Okamoto N, Fujinaga S, et al. Progressive brain atrophy in Schinzel-Giedion syndrome with a SETBP1 mutation. Eur J Med Genet. 2015;58(8):369–371. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2015.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minakuchi M, Kakazu N, Gorrin-Rivas MJ, et al. Identification and characterization of SEB, a novel protein that binds to the acute undifferentiated leukemia-associated protein SET. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268(5):1340–1351. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Filges I, Shimojima K, Okamoto N, et al. Reduced expression by SETBP1 haploinsufficiency causes developmental and expressive language delay indicating a phenotype distinct from Schinzel-Giedion syndrome. J Med Genet. 2011;48(2):117–122. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.084582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyake F, Kuroda Y, Naruto T, et al. West syndrome in a patient with Schinzel-Giedion syndrome. J Child Neurol. 2015;30(7):932–936. doi: 10.1177/0883073814541468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grosso S, Pagano C, Cioni M, et al. Schinzel-Giedion syndrome: a further cause of West syndrome. Brain Dev. 2003;25(4):294–298. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(02)00232-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lehman.AM, McFadden D, Pugash D, et al. Schinzel-Giedion syndrome: report of splenopancreatic fusion and proposed diagnostic criteria. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A(10):1299–1306. doi: 10.1002/(ISSN)1552-4833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsumoto F, Tohda A, Shimada K, et al. Malignant retroperitoneal tumor arising in a multicystic dysplastic kidney of a girl with Schinzel-Giedion syndrome. Int J Urol. 2005;12(12):1061–1062. doi: 10.1111/iju.2005.12.issue-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]