Abstract

目的

系统评价孕期及婴幼儿期补充益生菌预防儿童特应性皮炎的效果。

方法

运用RevMan5.3软件,对2008年1月至2018年5月国内外发表的有关孕期及婴幼儿期使用益生菌预防儿童特应性皮炎的随机对照试验研究进行Meta分析,并按干预菌株、随访时间、补充益生菌时间、研究地区进行亚组分析。

结果

最终纳入22篇文献,干预组和对照组病例分别为3280例和3 281例。合并效应量结果显示,孕期和/或婴幼儿期使用益生菌可减少儿童特应性皮炎的发生(RR=0.81,95% CI:0.70~0.93,P < 0.05)。亚组分析结果显示,使用乳酸杆菌和双歧杆菌混合菌株干预效果显著(RR=0.68,95% CI:0.52~0.90,P < 0.05);孕期及婴幼儿期均补充益生菌效果显著(RR=0.77,95% CI:0.66~0.90,P < 0.05);孕期和/或婴幼儿期补充益生菌预防特应性皮炎对≤ 2岁儿童效果较显著(RR=0.74,95% CI:0.61~0.90),而对2岁以上儿童效果不显著;研究地区为澳洲或欧洲/美国的效果显著(P < 0.05),合并RR及95% CI分别为0.83(95% CI:0.73~0.96)、0.74(95% CI:0.61~0.91)。异质性主要源于不同随访时间(I2=62.7%)和补充益生菌时间(I2=53.5%)。

结论

孕期及婴幼儿期补充益生菌有利于预防儿童特应性皮炎的发生,其中使用乳酸杆菌和双歧杆菌混合菌株干预效果显著。

Keywords: 特应性皮炎, 益生菌, 随机对照试验, Meta分析, 儿童

Abstract

Objective

To systematically review the effect of probiotic supplementation during pregnancy and infancy in preventing atopic dermatitis in children.

Methods

RevMan5.3 was used to perform a Meta analysis of randomized controlled trials on the effect of probiotic supplementation during pregnancy and infancy in preventing atopic dermatitis in children published between January 2008 and May 2018 across the world. A subgroup analysis was conducted according to the type of probiotics for intervention, follow-up time, time of probiotic supplementation, and study areas.

Results

A total of 22 articles were selected, with 3 280 cases in the intervention group and 3 281 cases in the control group. The results of pooled effect size showed that probiotic supplementation during pregnancy and/or infancy significantly reduced the incidence rate of atopic dermatitis (RR=0.81, 95% CI:0.70-0.93, P < 0.05). According to the subgroup analysis, the intervention with Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium had a significant effect (RR=0.68, 95% CI:0.52-0.90, P < 0.05); probiotic supplementation during both pregnancy and infancy also had a significant effect (RR=0.77, 95% CI:0.66-0.90, P < 0.05); probiotic supplementation during pregnancy and/or infancy had a better effect in preventing atopic dermatitis in children aged ≤ 2 years than in those aged > 2 years (RR=0.74, 95% CI:0.61-0.90, P < 0.05); probiotic supplementation had a significant effect in Australia (RR=0.83, 95% CI:0.73-0.96, P < 0.05) and Europe/the United States (RR=0.74, 95% CI:0.61-0.91, P < 0.05). Heterogeneity was mainly due to follow-up time (I2=62.7%) and time of probiotic supplementation (I2=53.5%).

Conclusions

Probiotic supplementation during pregnancy and infancy helps to prevent atopic dermatitis in children, and mixed Lactobacillus-Bifidobacterium intervention has a better effect.

Keywords: Atopic dermatitis, Probiotics, Randomized controlled trial, Meta analysis, Child

过敏性疾病(allergic diseases)又称变态反应性疾病,包括了过敏性哮喘、过敏性鼻炎、特应性皮炎、食物过敏等。近年来,儿童过敏性疾病的发病率增加,加剧了家庭和社会的经济和心理负担[1-2]。特应性皮炎是儿童主要过敏性疾病之一,有关益生菌预防儿童特应性皮炎的研究也越来越多,但这些研究的结果不尽一致[3-5]。此外,由于这些研究大多样本量较小,难以说明益生菌预防特应性皮炎的效果。近年来,国外陆续有学者开展了有关孕期及婴幼儿期补充益生菌预防儿童过敏性疾病方面的系统评价[6-7],但缺乏系统评价益生菌预防特应性皮炎方面的报道,尤其是国内缺乏这方面的研究。因此,有必要开展孕期及婴幼儿期补充益生菌预防儿童特应性皮炎效果研究的系统分析。本研究选取公认已知益生菌中研究相对集中的双歧杆菌、乳酸杆菌两种菌株,综合国内外近年来有关益生菌预防儿童特应性皮炎的随机对照试验研究,评价孕期及婴幼儿期补充益生菌预防儿童特应性皮炎的效果,为下一步的临床应用提供理论依据。

1. 资料与方法

1.1. 资料来源

分别在万方数据库、中国学术期刊全文数据库(CNKI)、中国生物医学期刊文献数据库(CBM)、PubMed、Embase数据库,检索2008年1月1日至2018年5月31日有关益生菌预防儿童特应性皮炎的相关文献。检索词英文为“Bifidovacteria, Lactobacilli, atopic dermatitis, allergic diseases, infant, children, probiotic”等,中文为“益生菌、双歧杆菌、乳酸杆菌、特应性皮炎、过敏性疾病、婴幼儿”等。

1.2. 文献纳入标准

(1)研究类型为双盲随机对照试验;(2)文献发表于2008年1月1日至2018年5月31日期间;(3)仅限于孕期和/或婴幼儿期使用益生菌预防儿童特应性皮炎的研究;(4)研究对象未患其他类型疾病。

1.3. 文献质量评价

采用Jadad量表对纳入文献进行质量评价,从随机方案及隐匿、盲法、退出与失访病例的原因及例数3个方面进行评价,采用0~5分记分法,≤2分为低质量研究,≥3分为较高质量研究[6]。

1.4. 统计学分析

按Meta分析要求整理入选文献,数据分析采用RevMan5.3软件,以RR值及其95%CI值作为观察指标[8]。进行异质性检验,若各研究间异质性不显著,则采用固定效应模型;若各研究间异质性显著,则采用随机效应模型。并按干预菌株、随访时间、补充益生菌时间、研究地区进行亚组分析;为降低异质性,当各亚组研究数量 < 5项时,均采用随机效应模型合并效应量[7]。运用漏斗图判断纳入文献是否存在发表偏倚;采用不同模型做敏感性分析。P < 0.05表示有统计学意义。

2. 结果

2.1. 纳入文献基本情况

共检索到相关文献186篇,其中中文文献56篇,英文文献130篇。通过阅读文题及摘要,排除137篇文献;通过阅读全文排除27篇文献,最后纳入22篇随机对照试验研究[3, 9-29]。

所纳入文献的研究范围涵盖全球12个国家,干预组和对照组累计纳入分别为3 280例、3 281例。Jadad量表评价显示所纳入文献均为质量较高的研究。纳入文献的基本情况见表 1。

1.

入选文献的基本情况

| 文献 | 样本量(干预组/对照组) | 补充益生菌时间 | 干预用菌株 | 随访时点 | 研究类型 | 对照组处理 | 研究地区 | Jadad评分 |

| Ou 2012[3] | 201/198 | 孕24周至6月龄 | 乳酸杆菌 | 6、18、36月龄 | 双盲随机对照试验 | 安慰剂 | 中国 | 5 |

| Abrahamsson 2013[9] | 94/90 | 孕36周至12月龄 | 乳酸杆菌 | 2、7岁 | 双盲随机对照试验 | 安慰剂 | 瑞典 | 4 |

| B?ttcher 2008[10] | 51/53 | 孕36周至12月龄 | 乳酸杆菌 | 1、3、6、12、24月龄 | 双盲随机对照试验 | 安慰剂 | 英国 | 5 |

| Boyle 2011[11] | 230/222 | 孕36周至分娩 | 乳酸杆菌 | 3、6、12月龄 | 双盲随机对照试验 | 安慰剂 | 英国 | 5 |

| Huurre 2008[12] | 72/68 | 妊娠前3个月至母乳喂养结束 | 乳酸杆菌双歧杆菌 | 1、6、12月龄 | 双盲随机对照试验 | 安慰剂 | 芬兰 | 4 |

| Kim 2010[13] | 111/123 | 预产期前8周至6月龄 | 乳酸杆菌双歧杆菌 | 3、6、12月龄 | 双盲随机对照试验 | 安慰剂 | 韩国 | 4 |

| Kopp 2008[14] | 50/44 | 预产期前6周至6月龄 | 乳酸杆菌 | 12、24月龄 | 双盲随机对照试验 | 安慰剂 | 德国 | 5 |

| Niers 2009[15] | 150/148 | 预产期前6周至12月龄 | 乳酸杆菌双歧杆菌 | 3、12、24月龄 | 双盲随机对照试验 | 安慰剂 | 荷兰 | 5 |

| Prescott 2008[16] | 74/76 | 出生至6月龄 | 乳酸杆菌 | 2.5岁 | 双盲随机对照试验 | 安慰剂 | 澳大利亚 | 5 |

| Rautava 2012[17] | 143/124 | 预产期前2个月至母乳喂养2个月 | 乳酸杆菌双歧杆菌 | 1、3、6、12、24月龄 | 双盲随机对照试验 | 安慰剂 | 芬兰 | 5 |

| Wickens 2012[18] | 282/286 | 孕35周至2岁 | 乳酸杆菌双歧杆菌 | 2、4岁 | 双盲随机对照试验 | 安慰剂 | 新西兰 | 4 |

| Wickens 2008[19] | 315/318 | 孕35周至2岁 | 乳酸杆菌双歧杆菌 | 3、6、12、18月龄 | 双盲随机对照试验 | 安慰剂 | 新西兰 | 4 |

| Wickens 2013[20] | 245/258 | 孕35周至2岁 | 乳酸杆菌双歧杆菌 | 2、4、6岁 | 双盲随机对照试验 | 安慰剂 | 新西兰 | 5 |

| 吴福玲2010[21] | 34/36 | 孕36周至母乳喂养结束 | 双歧杆菌 | 24月龄 | 双盲随机对照试验 | 安慰剂 | 中国 | 5 |

| Allen 2014[22] | 214/222 | 孕36周至6月龄 | 乳酸杆菌双歧杆菌 | 24月龄 | 双盲随机对照试验 | 安慰剂 | 英国 | 5 |

| Cabana 2017[23] | 92/92 | 出生后至6月龄 | 乳酸杆菌 | 24月龄 | 双盲随机对照试验 | 安慰剂 | 美国 | 5 |

| Dotterud 2010[24] | 131/133 | 孕36周至3月龄 | 乳酸杆菌双歧杆菌 | 2岁 | 双盲随机对照试验 | 安慰剂 | 挪威 | 4 |

| Jensen 2012[25] | 60/54 | 出生后至6月龄 | 乳酸杆菌 | 5岁 | 双盲随机对照试验 | 安慰剂 | 澳大利亚 | 5 |

| Soh 2009[26] | 124/121 | 出生至6月龄 | 乳酸杆菌双歧杆菌 | 1、3、6、12月龄 | 双盲随机对照试验 | 安慰剂 | 新加坡 | 5 |

| Kuitunen 2009[27] | 459/463 | 预产期前1月至6月龄 | 乳酸杆菌双歧杆菌丙酸杆菌 | 5岁 | 双盲随机对照试验 | 安慰剂 | 芬兰 | 5 |

| West 2013[28] | 59/62 | 4~13月龄 | 乳酸杆菌 | 8、9岁 | 双盲随机对照试验 | 安慰剂 | 瑞典 | 5 |

| West 2009[29] | 89/90 | 4~13月龄 | 乳酸杆菌 | 13月龄 | 双盲随机对照试验 | 安慰剂 | 瑞典 | 5 |

2.2. 益生菌预防特应性皮炎的Meta分析结果

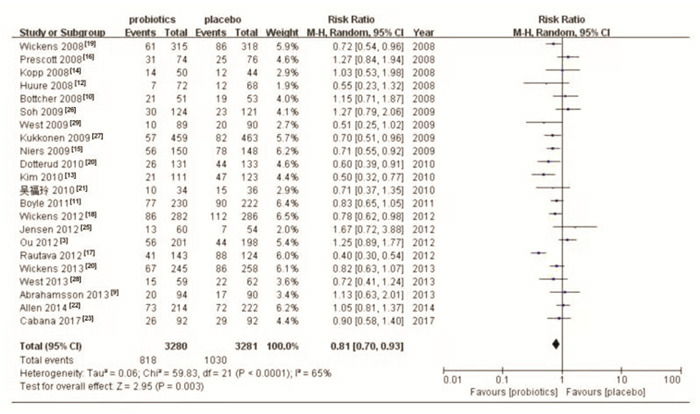

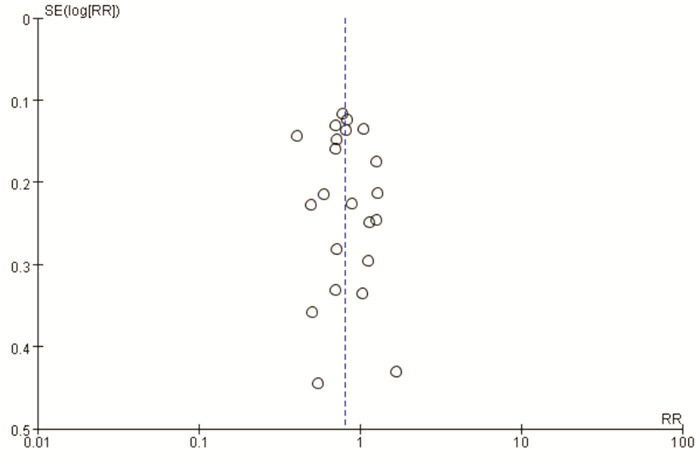

异质性检验结果显示各研究间存在显著异质性(χ2=59.83,P < 0.001,I2=65%),因此采用随机效应模型。合并效应量结果显示,孕期和/或婴幼儿期补充益生菌可减少特应性皮炎的发生,合并的RR为0.81(95%CI:0.70~0.93,P < 0.05),见图 1。漏斗图结果显示不存在发表偏倚,见图 2。采用随机效应模型和固定效应模型进行敏感性分析,所得结果相近(RR=0.79,95%CI:0.73~0.86,P < 0.05),提示稳定性较好。

1.

益生菌预防特应性皮炎的Meta分析森林图

2.

益生菌预防特应性皮炎的Meta分析漏斗图

2.3. 亚组分析结果

按干预菌株不同(单独补充乳酸杆菌、双歧杆菌,或二者混合)进行亚组分析,结果显示,干预组仅使用乳酸杆菌或仅使用双歧杆菌预防儿童特应性皮炎效果不显著(P > 0.05),使用二者混合菌株干预效果显著(RR=0.68,95%CI:0.52~0.90,P < 0.05)。

按随访结束时间不同(≤2岁、 > 2岁)进行亚组分析,结果表明随访结束时间≤2岁时效果显著(RR=0.74,95%CI:0.61~0.90,P < 0.05)。

按补充益生菌时间(仅婴幼儿期补充或孕期及婴幼儿期均补充)进行亚组分析,结果表明孕期及婴幼儿期均补充益生菌效果显著(RR=0.77,95%CI:0.66~0.90,P < 0.05)。

按不同研究地区进行亚组分析,结果表明研究地区为澳洲或欧洲/美国效果显著(P < 0.05),合并的RR分别为0.83(95%CI:0.73~0.96)、0.74(95%CI:0.61~0.91)。

亚组间差异比较结果显示不同随访时间(I2=62.7%)和补充益生菌时间(I2=53.5%)异质性较大,见表 2。

2.

亚组分析

| 分类 | 异质性检验 | 模型 | 合并效应量 | Z | P | 亚组间差异比较 | |||||

| χ2 | P | I2(%) | RR | 95%CI | χ2 | P | I2(%) | ||||

| 菌株 | |||||||||||

| 混合菌株 | 32.56 | < 0.001 | 78 | 随机 | 0.68 | 0.52~0.90 | 2.71 | 0.007 | 2.46 | 0.29 | 18.6 |

| 乳酸杆菌 | 23.88 | 0.02 | 50 | 随机 | 0.87 | 0.73~1.04 | 1.48 | 0.14 | |||

| 双歧杆菌 | 0.54 | 0.910 | 0 | 随机 | 0.87 | 0.72~1.05 | 1.45 | 0.15 | |||

| 随访时间 | |||||||||||

| ≤2岁 | 40.70 | < 0.001 | 68 | 随机 | 0.74 | 0.61~0.90 | 3.11 | 0.002 | 2.68 | 0.10 | 62.7 |

| > 2岁 | 13.95 | 0.05 | 50 | 随机 | 0.93 | 0.77~1.12 | 0.78 | 0.43 | |||

| 补充益生菌时间 | |||||||||||

| 婴幼儿期 | 8.97 | 0.11 | 44 | 固定 | 0.99 | 0.80~1.23 | 0.06 | 0.95 | 2.15 | 0.14 | 53.5 |

| 孕期及婴幼儿期 | 45.41 | < 0.001 | 67 | 随机 | 0.77 | 0.66~0.90 | 3.37 | < 0.001 | |||

| 研究地区 | |||||||||||

| 亚洲地区 | 12.92 | 0.005 | 77 | 随机 | 0.88 | 0.54~1.42 | 0.53 | 0.60 | 1.31 | 0.52 | 0 |

| 澳洲地区 | 7.98 | 0.09 | 50 | 随机 | 0.83 | 0.73~0.96 | 2.60 | 0.009 | |||

| 欧洲及美国 | 34.07 | < 0.001 | 68 | 随机 | 0.74 | 0.61~0.91 | 2.90 | 0.004 | |||

3. 讨论

针对儿童过敏性疾病,近年来学者提出了卫生学假说,现代社会由于抗生素的应用、无菌食品的出现,以及其他环境因素的改变,导致婴幼儿出生后暴露于微生物环境的机会减少,婴幼儿过敏性疾病的发病率上升[23, 30]。已有诸多研究证实在过敏性疾病发生之前肠道菌群会发生改变[1, 31],当肠道菌群紊乱时,肠道内共生菌阻止致病菌入侵、抑制炎症反应等作用减弱,打破了肠道共生菌所诱导的免疫耐受,导致异常免疫应答,从而加重变态反应性疾病的发展过程[32]。研究发现,早期暴露微生物环境,尤其是围产期的微生物暴露,能够显著预防过敏性疾病的发生[33]。

本Meta分析显示,孕期和/或婴幼儿期补充益生菌可减少儿童特应性皮炎的发生,合并的RR为0.81(95%CI:0.70~0.93),与其他研究结果相似[6, 20]。通过亚组间差异比较发现,异质性主要来源于不同随访时间(I2=62.7%)和补充益生菌时间(I2=53.5%)。既往研究表明,母亲孕期补充益生菌,能够在分娩时或通过母乳喂养将益生菌转移给新生儿,帮助新生儿建立肠道微生物环境[34]。近期有研究在羊水、胎盘、胎膜、脐带血和胎粪中均发现了微生物DNA,证实妊娠期间母亲体内微生物能够转移至胎儿[4]。肠道是新生儿产后最主要的微生物暴露源和免疫刺激的关键来源,生命早期补充益生菌能够帮助新生儿建立成熟的免疫应答;婴幼儿期肠道菌群促进黏膜免疫系统和肠道相关淋巴组织的正常发育,并在维持肠道微生态平衡和调节肠道黏膜免疫功能等方面起关键作用[4]。此外,肠道相关淋巴组织在变态反应中发挥着重要的免疫调节作用,同时也受到肠道菌群结构的影响[31]。因此,孕期及婴儿早期补充益生菌能够促进婴幼儿健康肠道菌群的形成,塑造成熟的免疫应答系统,从而预防儿童特应性皮炎的发生。

本Meta分析表明,干预组仅使用乳酸杆菌或仅使用双歧杆菌预防儿童特应性皮炎效果不显著,使用二者混合菌株干预效果显著(RR=0.68,95%CI:0.52~0.90),这与其他研究结果相似[7]。研究表明,正常儿童肠道菌群以乳酸杆菌和双歧杆菌为主,而过敏患儿体内梭状杆菌含量明显增加,双歧杆菌含量明显减少;特应性皮炎患儿肠道中大肠杆菌、金黄色葡萄球菌数量增多,而双歧杆菌和乳酸杆菌数量减少[33]。这可能可解释使用乳酸杆菌和双歧杆菌混合菌株预防儿童特应性皮炎效果较好的现象。此外,国际上也推荐使用乳酸杆菌和双歧杆菌治疗特应性皮炎患儿[35]。

本Meta分析显示,益生菌预防特应性皮炎对≤2岁儿童效果较显著(RR=0.74,95%CI:0.61~0.90),而对2岁以上儿童效果不显著,与国外一些研究结果相符[6, 36]。Wickens等[20]研究表明,益生菌对2岁以内儿童特应性皮炎的预防作用效果更明显。原因可能是婴幼儿过敏性疾病多发生在3岁以内,尤其是1岁以内的发病率最高,且随着婴幼儿年龄的增长,其免疫系统逐步完善,过敏性疾病大多可自愈[23]。这也有可能与本Meta分析纳入文献的益生菌补充时间均在2岁以前有关。

本Meta分析显示,仅婴儿期补充益生菌预防特应性皮炎的效果不佳,孕期及婴幼儿期均补充益生菌预防特应性皮炎效果显著。Cabana等[23]开展益生菌预防特应性皮炎的随机对照试验研究,干预组(n=92)于0~6个月补充益生菌,对照组(n=92)使用安慰剂,随访至2岁时结果表明,特应性皮炎的累计发病率在两组间没有显著性差异。Zhang等[6]所做的益生菌预防食物过敏的Meta分析结果显示,母亲在妊娠后期1个月使用及出生后新生儿使用益生菌能显著降低儿童早期发生过敏的风险,而仅在妊娠期或仅在出生后使用益生菌效果不明显。世界过敏组织(WAO)过敏性疾病预防指南推荐,针对过敏性疾病高风险的婴儿,母亲应在妊娠后期、哺乳期及婴儿出生后均补充益生菌[36]。

本Meta分析显示,研究地区为澳洲或欧洲/美国的干预效果显著,亚洲地区研究的干预效果不显著。一方面,亚洲地区有关益生菌预防特应性皮炎的随机对照试验研究较少,研究样本量较小;另一方面,亚洲地区的研究干预时段多为婴儿期,孕期和婴儿期均进行干预的研究较少。

本Meta分析存在以下不足之处:(1)未对益生菌使用剂量、干预持续时间等做进一步的亚组分析;(2)纳入研究的观察终点时间不一致,最长的至7岁,最短的至6月龄,可能造成原始研究不具有可比性;(3)纳入文献来自于不同国家,而不同人种、不同环境下的儿童对同等剂量同种益生菌的反应可能不同,从而影响最终结果。

综上所述,孕期及婴幼儿期补充益生菌有利于预防儿童特应性皮炎的发生,其中使用乳酸杆菌和双歧杆菌混合菌株干预效果显著,且这种预防作用只在2岁以内儿童中效果显著,而对2岁以上儿童效果不显著。因此,为预防儿童特应性皮炎,应提倡孕期及婴幼儿期均补充益生菌,推荐使用乳酸杆菌和双歧杆菌混合菌株,尤其是有家族过敏史的婴幼儿,应早期补充益生菌以预防儿童特应性皮炎的发生。

Biography

殷道根, 男, 硕士研究生

References

- 1.Koet LBM, Brand PLP. Increase in atopic sensitization rate among Dutch children with symptoms of allergic disease between 1994 and 2014. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2018;29(1):78–83. doi: 10.1111/pai.2018.29.issue-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.王 雪梅, 王 玲. 2005-2014年中国儿童哮喘与过敏体质、家族史、被动吸烟病例对照研究的Meta分析. http://d.old.wanfangdata.com.cn/Periodical/zgfybj201706079 中国妇幼保健. 2017;32(6):1351–1354. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ou CY, Kuo HC, Wang L, et al. Prenatal and postnatal probiotics reduces maternal but not childhood allergic diseases:a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42(9):1386–1396. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2012.04037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.West CE, Jenmalm MC, Prescott SL. The gut microbiota and its role in the development of allergic disease:a wider perspective. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45(1):43–53. doi: 10.1111/cea.2014.45.issue-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.曾 燕, 刘 小芸, 邓 全敏. 饮食干预对高过敏风险婴儿过敏预防的疗效观察. http://d.old.wanfangdata.com.cn/Periodical/zgetbjzz201507026 中国儿童保健杂志. 2015;23(7):756–759. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang GQ, Liu CY, Zhang Q, et al. Probiotics for prevention of atopy and food hypersensitivity in early childhood:a PRISMAcompliant systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(8):e2562. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zuccotti G, Meneghin F, Aceti A, et al. Probiotics for prevention of atopic diseases in infants:systematic review and metaanalysis. Allergy. 2015;70(11):1356–1371. doi: 10.1111/all.2015.70.issue-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.曾 宪涛, 包 翠萍, 曹 世义, et al. Meta分析系列之三:随机对照试验的质量评价工具. 中国循证心血管医学杂志. 2012;4(3):183–185. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-4055.2012.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abrahamsson TR, Jakobsson T, Bjorksten B, et al. No effect of probiotics on respiratory allergies:a seven-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial in infancy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2013;24(6):556–561. doi: 10.1111/pai.2013.24.issue-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Böttcher MF, Abrahamsson TR, Fredriksson M, et al. Low breast milk TGF-beta2 is induced by Lactobacillus reuteri supplementation and associates with reduced risk of sensitization during infancy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008;19(6):497–504. doi: 10.1111/pai.2008.19.issue-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyle RJ, Ismail IH, Kivivuori S, et al. Lactobacillus GG treatment during pregnancy for the prevention of eczema:a randomized controlled trial. Allergy. 2011;66(4):509–516. doi: 10.1111/all.2011.66.issue-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huurre A, Laitinen K, Rautava S, et al. Impact of maternal atopy and probiotic supplementation during pregnancy on infant sensitization:a double blind placebo-controlled study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38(8):1342–1348. doi: 10.1111/cea.2008.38.issue-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim JY, Kwon JH, Ahn SH, et al. Effect of probiotic mix (Bifidobacterium bifidum, Bifidobacterium lactis, Lactobacillus acidophilus) in the primary prevention of eczema:a doubleblind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21:e386–e393. doi: 10.1111/pai.2010.21.issue-2p2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kopp MV, Hennemuth I, Heinzmann A, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of probiotics for primary prevention:no clinical effects of Lactobacillus GG supplementation. Pediatrics. 2008;121(4):e850–e856. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niers L, Martin R, Rijkers G, et al. The effects of selected probiotic strains on the development of eczema (the PandA study) Allergy. 2009;64(9):1349–1358. doi: 10.1111/all.2009.64.issue-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prescott SL, Wiltschut J, Taylor A, et al. Early markers of allergic disease in a primary prevention study using probiotics:2.5-year follow-up phase. Allergy. 2008;63(11):1481–1490. doi: 10.1111/all.2008.63.issue-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rautava S, Kainonen E, Salminen S, et al. Maternal probiotic supplementation during pregnancy and breast-feeding reduces the risk of eczema in the infant. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(6):1355–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wickens K, Black P, Stanley TV, et al. A protective effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 against eczema in the first 2 years of life persists to age 4 years. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42(7):1071–1079. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2012.03975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wickens K, Black PN, Stanley TV, et al. A differential effect of 2 probiotics in the prevention of eczema and atopy:a doubleblind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122(4):788–794. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wickens K, Stanley TV, Mitchell EA, et al. Early supplementation with Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 reduces eczema prevalence to 6 years:does it also reduce atopic sensitization? Clin Exp Allergy. 2013;43(9):1048–1057. doi: 10.1111/cea.2013.43.issue-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.吴 福玲, 冯 学斌, 刘 秀香, et al. 双歧杆菌对母乳成分的影响及其与婴儿过敏性疾病的关系. 临床儿科杂志. 2010;28(3):260–263. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-3606.2010.03.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allen SJ, Jordan S, Storey M, et al. Probiotics in the prevention of eczema:a randomised controlled trial. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99(11):1014–1019. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-305799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cabana MD, Mckean M, Caughey AB, et al. Early probiotic supplementation for eczema and asthma prevention:a randomized controlled trial. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28784701. Pediatircs. 2017;140(3):e20163000. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dotterud CK, Storrø O, Johnsen R, et al. Probiotics in pregnant women to prevent allergic disease:a randomized, double-blind trial. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(3):616–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jensen MP, Meldrum S, Taylor AL, et al. Early probiotic supplementation for allergy prevention:long-term outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:1209–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soh SE, Aw M, Gerez I, et al. Probiotic supplementation in the first 6 months of life in at risk Asian infants-effects on eczema and atopic sensitization at the age of 1 year. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39(4):571–578. doi: 10.1111/cea.2009.39.issue-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuitunen M, Kukkonen K, Juntunen-Backman K, et al. Probiotics prevent IgE-associated allergy until age 5 years in cesarean-delivered children but not in the total cohort. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(2):335–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.West CE, Hammarström ML, Hernell O, et al. Probiotics in primary prevention of allergic disease-follow-up at 8-9 years of age. Allergy. 2013;68(8):1015–1020. doi: 10.1111/all.2013.68.issue-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.West CE, Hammarström ML, Hernell O. Probiotics during weaning reduce the incidence of eczema. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2009;20(5):430–437. doi: 10.1111/pai.2009.20.issue-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.罗 宇阳, 吴 薇岚, 吴 葆宁, et al. 南宁市0~24个月婴幼儿过敏性疾病的临床特征及相关影响因素分析. http://d.old.wanfangdata.com.cn/Periodical/zgfybj201801047 中国妇幼保健. 2018;33(1):132–135. [Google Scholar]

- 31.夏 利平, 姜 毅. 益生菌在儿童变态反应性疾病中的防治作用. http://www.zgddek.com/CN/abstract/abstract13849.shtml. 中国当代儿科杂志. 2016;18(2):189–194. doi: 10.7499/j.issn.1008-8830.2016.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.单 延春, 冯 雪英, 衣 明纪, et al. 食物过敏儿童的生长状况与营养管理. 中国儿童保健杂志. 2016;24(10):1055–1058. doi: 10.11852/zgetbjzz2016-24-10-13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.陈 小丽, 吴 佳音. 闽南地区3196例儿童过敏原检测结果分析. http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-ZFYB201623057.htm 中国妇幼保健. 2016;31(23):5053–5055. [Google Scholar]

- 34.周 佳, 许 正浩, 赵 华伟. 益生菌预防婴幼儿湿疹复发作用的Meta分析. 海峡药学. 2016;28(6):152–154. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-3765.2016.06.071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Floch MH, Walker WA, Sanders ME, et al. Recommendations for probiotic use -2015 update:proceedings and consensus opinion. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49(Suppl 1):S69–S73. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fiocchi A, Pawankar R, Cuello-Garcia C, et al. World Allergy Organization-McMaster University Guidelines for Allergic Disease Prevention (GLAD-P):Probiotics. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25628773. World Allergy Organ J. 2015;8(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s40413-015-0055-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]