Abstract

Background

Researchers have criticised epilepsy care for adults for its lack of impact, stimulating the development of various service models and strategies to respond to perceived inadequacies.

Objectives

To assess the effects of any specialised or dedicated intervention beyond that of usual care in adults with epilepsy.

Search methods

For the latest update of this review, we searched the Cochrane Epilepsy Group Specialized Register (9 December 2013), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2013, Issue 11), MEDLINE (1946 to June 2013), EMBASE (1988 to June 2013), PsycINFO (1887 to December 2013) and CINAHL (1937 to December 2013). In addition, we contacted experts in the field to seek information on unpublished and ongoing studies, checked the websites of epilepsy organisations and checked the reference lists of included studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials, controlled or matched trials, cohort studies or other prospective studies with a control group, and time series studies.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected studies, extracted all data, and assessed the quality of all included studies.

Main results

Our review included 18 different studies of 16 separate interventions, which we classified into seven distinct groups. Most of the studies have methodological weaknesses, and many results from other analyses within studies need to be interpreted with caution because of study limitations. Consequently, there is currently limited evidence for the effectiveness of interventions to improve the health and quality of life in people with epilepsy. It was not possible to combine study results in a meta‐analysis because of the heterogeneity of outcomes, study populations, interventions and time scales across the studies.

Authors' conclusions

Two intervention types, the specialist epilepsy nurse and self management education, have some evidence of benefit. However, we did not find clear evidence that other service models substantially improve outcomes for adults with epilepsy. It is also possible that benefits are situation specific and may not apply to other settings. These studies included only a small number of service providers whose individual competence or expertise may have had a significant impact on outcomes. At present it is not possible to advocate any single model of service provision.

Keywords: Adult; Humans; Delivery of Health Care; Delivery of Health Care/methods; Epilepsy; Epilepsy/nursing; Epilepsy/therapy; Neurology; Outcome and Process Assessment, Health Care; Patient Education as Topic; Patient Education as Topic/methods; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Self Care; Self Care/methods

Plain language summary

Care delivery and self management strategies for adults with epilepsy

Evidence for the effectiveness of care interventions for adults with epilepsy is still unclear.

This review compared the effectiveness of a range of interventions, including specialist nurses and management strategies, in improving outcomes for adults with epilepsy. We identified seven distinct intervention types, with varying amounts of evidence to support them. While included studies did show some benefit from specialist epilepsy nurses and self management education, other intervention types lack evidence of effectiveness. This is compounded by the poor quality methods of some studies and by the complex nature of the interventions, whose impact may vary according to where they take place. Based on this evidence, it is not possible to advocate any specific intervention type in the care of adults with epilepsy.

Background

Description of the condition

Epilepsy is spectrum of disorders in which an individual may experience seizures that are unpredictable in frequency (England 2012). Researchers have identified at least 40 different seizure types (Berg 2010). While most people can control seizures well with medications and other treatment options, epilepsy can pose challenges to autonomy and in social, school and work situations. Not only do people with seizures tend to have more physical problems (ranging from fractures and bruising to—rarely—an increased risk of sudden death) but people with epilepsy face significant challenges in how others perceive (or misperceive) their condition, which can lead to the stigmatisation of people with epilepsy (Bandstra 2008). As a result, they may experience a lack of social support, social isolation, embarrassment, fear and discrimination (England 2012). Epilepsy affects around 50 million people worldwide, with around 80% of all cases in developing countries (WHO 2012). Epilepsy is most common in children and older adults (Betts 1992; Sander 1990).

Description of the intervention

The self management of epilepsy refers to a wide range of health behaviours and activities that an individual can learn and adapt in order to promote seizure control and enhance well‐being (Austin 1997). Self management of any condition typically entails a partnership between users and service providers (Clark 2008). Various dedicated models of service provision exist to improve care networks and self education (Clark 2010; Fitzsimons 2012; SIGN 2003; SIGN 2005). Services may include specialist epilepsy outpatient clinics, nurse‐based liaison services between primary (GP) and secondary/tertiary (hospital‐based) care and specialist epilepsy multidisciplinary community teams (Clark 2010; Fitzsimons 2012; SIGN 2003; SIGN 2005). Services may also include input from social care or the voluntary sector (Clark 2010; SIGN 2003; SIGN 2005) and target specific groups, such as people with learning disabilities.

How the intervention might work

Specialist or dedicated models of care, care networks, or self education and self management may improve the quality of care, promote more systematic multidisciplinary follow‐up of individuals and enhance communication among professionals, patients and other services (Fitzsimons 2012). Importantly, care should enable people with epilepsy to cope with all aspects of the disease through improved self education and self management skills (Clark 2008; Fitzsimons 2012).

Why it is important to do this review

Different researchers have criticised epilepsy care as having limited impact by not fully addressing all the health and social needs of people suffering from it (Betts 1992; Chappell 1992; Elwyn 2003; Thapar 1996). In order to improve the quality of care for adults with epilepsy, the aim of this review is to systematically update the evidence from studies investigating the effectiveness of these service models compared to non‐specialist services. This systematic review is an update of the Cochrane Review previously published in 2009 (Bradley 2008).

Objectives

To assess the effects of any specialised or dedicated intervention beyond that of usual care in adults with epilepsy.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included several study types in the review, as the interventions considered were highly variable and complex. We based our inclusion criteria for studies on those used by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Review Group (EPOC). We included all randomised controlled, controlled or matched trials, cohort or other prospective studies with a control group, and time series studies.

Types of participants

We considered studies that included anyone aged over 16 years with any diagnosis of new or recurrent epilepsy eligible for this review. We included studies incorporating epilepsy with other long‐term conditions if they reported results separately for each condition.

Types of interventions

We included any intervention, including a specialised or dedicated team or individual for the care of epilepsy patients, whether based:

in hospital (e.g. a specialist epilepsy clinic);

in the community (e.g. a dedicated team focusing on epilepsy treatment);

in general practice (e.g. a specialist epilepsy nurse);

elsewhere (e.g. social worker, the voluntary sector);

on education or counselling with content specific to epilepsy for improved self management;

as a care network combining any of these elements.

Types of outcome measures

The outcomes we considered are:

seizure frequency and severity;

appropriateness and volume of medication prescribed (including evidence of drug toxicity);

participants' reported knowledge of information and advice received from professionals;

participants' reports of health and quality of life;

objective measures of general health status;

objective measures of social or psychological functioning (including the number of days spent on sick leave/absence from school or work, and employment status);

costs of care or treatment.

We assessed all outcome measures for reliability and validity (i.e. for clinical relevance and whether validated tools were used for outcome measurement). If trials misused measures (e.g. children's scales used on adults), we planned to investigate their effect on study results by a sensitivity analysis.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the following databases.

Cochrane Epilepsy Group Specialized Register (9 December 2013). See Appendix 1 for details of search strategy for the latest update.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2013, Issue 11). See Appendix 2 for details of search strategy for the latest update.

MEDLINE (Ovid) (1946 to June 2013). See Appendix 3 for details of search strategy.

EMBASE (1988 to June 2013). See Appendix 4 for details of search strategy.

PsycINFO (EBSCOhost 1887 to December 2013). See Appendix 5 for details of search strategy.

CINAHL (EBSCOhost 1937 to December 2013). See Appendix 6 for details of search strategy.

Finally we contacted experts in the field to seek information on unpublished and ongoing studies, checked the websites of epilepsy organisations and checked the reference lists of included studies.

We should note that we undertook this review at the same time as another Cochrane review update of care delivery and self management strategies for children with epilepsy (Lindsay 2015), and we used the same search strategy for both reviews.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We screened papers in two stages. At stage 1, two review authors (PM and BL in the original review, PM and NF in the updated review), independently screened all titles and abstracts identified by the searches for relevance. We only excluded papers that were clearly irrelevant at this stage. At stage 2, two review authors (PM and BL in the original review, PM and NF in the updated review) independently screened the full text, identified relevant studies and assessed eligibility of studies for inclusion, resolving any disagreements by discussion.

Data extraction and management

The same review authors extracted the following types of data.

Study characteristics, including place of publication, date of publication, population characteristics, setting, and detailed nature of intervention, comparator and outcomes. A key purpose of these data is to define unexpected clinical heterogeneity in included studies independently from analysis of results.

Results of included studies with respect to each of the main outcomes indicated in the review question, including data on outcomes not considered and assessing the possibility of selective reporting of results for particular outcomes.

For the original systematic review, we based our judgement regarding the quality of included studies on explicit criteria used by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Review Group (EPOC) (http://epoc.cochrane.org/sites/epoc.cochrane.org/files/uploads/datacollectionchecklist.pdf). For the update, we assessed the risk of bias (see below). We resolved any disagreements when extracting data or assessing their quality by discussion. If reports provided inadequate information, we contacted authors for further information.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two authors (PB and NF) independently assessed every trial using a simple form following the domain‐based evaluation described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), as all included studies prospectively compared interventions with control populations. In view of this, we assessed the following domains as having a high, low or unclear risk of bias.

Sequence generation.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding (of participants, personnel and outcome assessors).

Incomplete outcome data.

Selective outcome reporting.

Other sources of bias.

In addition, we conducted an overall 'Risk of bias' assessment based on the information required to assess the above.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity between studies by reviewing the differences across trials. There was considerable clinical heterogeneity in the trials, so we did not consider it appropriate to run any meta‐analyses. Had we combined the results of any trials in a meta‐analysis, we would have investigated heterogeneity with an I2 test. If the results had shown heterogeneity, we would have investigated the cause.

Data synthesis

If studies had been of a suitable quality and sufficiently homogeneous to combine in a meta‐analysis, we would have used (standardised) mean differences for continuous variables and relative risks (including Mantel Haenzsel analysis) for dichotomous variables, using either a random‐effects or fixed‐effect model. For future updates of this review, if the data allows, we will consider sensitivity analyses based on the risk of bias.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

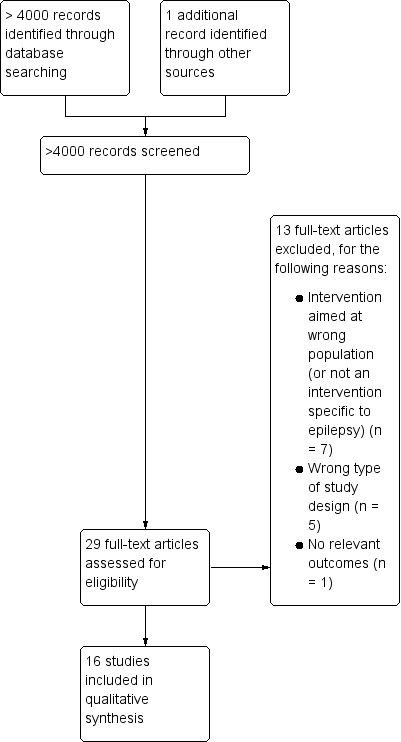

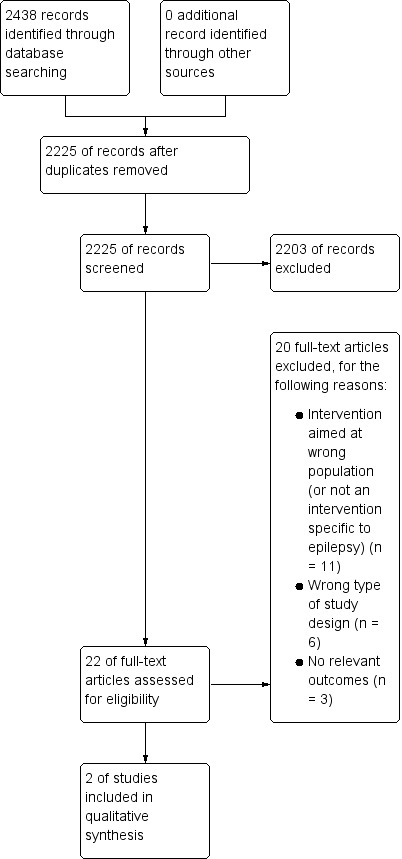

In the original review, initial searches identified over 4000 papers, including duplicates. Of 29 potentially eligible studies, we finally included 16 trials that evaluated 14 different interventions (Adamolekun 1999; Davis 2004; Gilliam 2004; Helde 2005; Helgeson 1990; May 2002; McAuley 2001; Mills 1999a; Mills 1999b; Morrow 1990; Peterson 1984; Ridsdale 1997; Ridsdale 1999; Ridsdale 2000; Thapar 2002; Warren 1998) (Figure 1). The updated searches yielded 2438 additional papers including duplicates, two of which we included (Aliasgharpour 2013; DiIorio 2011) (Figure 2). Hence, the updated review includes 18 different studies of 16 separate interventions.

1.

Study flow diagram (original searches).

2.

Study flow diagram (updated searches).

Included studies

While all the included studies investigated specialist care, the exact nature of this care varied between the studies. We therefore found it helpful to classify the included studies according to the type of specialist care under investigation. This produced a classification of seven intervention types.

Self management education.

Strategies to improve patient compliance.

Self management through screening.

Alternative models of outpatient care delivery.

Specialist nurse practitioners.

Behavioural interventions.

Guideline implementation and patient intervention.

We summarise information about each individual intervention in Appendix 7.

Self management education

Four trials evaluated the effect of self management education in adults with epilepsy (Aliasgharpour 2013; DiIorio 2011; Helgeson 1990; May 2002). Helgeson 1990 recruited participants from among those insured by Kaiser Permanente in California. May 2002 took place in 22 epilepsy centres across Germany, Austria and Switzerland. DiIorio 2011 was an online epilepsy self management programme to assist people with taking medication, managing stress and improving sleep quality in Atlanta, USA. Finally, Aliasgharpour 2013 evaluated an educational programme to improve self management in Zanjan, Iran.

Helgeson 1990 evaluated a two‐day psycho‐educational treatment programme (Sepulveda Epilepsy Education, also known as the Seizures and Epilepsy Education programme, or SEE) in 38 adults with epilepsy who were also prescribed antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). Participants were randomly assigned to either the SEE programme (n = 20) or to a waiting list control group (n = 23). Participants completed questionnaires before the programme and four months after completion. Investigators then invited waiting list control group members to attend the programme at four months. Questionnaires included questions about anxiety and depression, seizures, coping with epilepsy and self efficacy.

May 2002 evaluated a two‐day educational programme (the Modular Service Package Epilepsy, or MOSES) in adults with epilepsy. Two hundred forty‐two participants were randomly assigned to the MOSES programme (n = 113) or to a waiting list control group (n = 129). Participants completed questionnaires before the programme and six months after completion of the programme. Investigators then invited waiting list control group members to attend the MOSES programme at six months. Questionnaires included measures of knowledge, coping with epilepsy, seizure frequency, contentedness with AED therapy, depressive mood and an evaluation of MOSES.

DiIorio 2011 evaluated a six‐week WebEase programme, in 192 participants who voluntarily enrolled to participate after obtaining information about the study, either from healthcare professionals, online clinical research matching services, family, friends or online epilepsy and research sites. Following completion of a baseline assessment, only the first participant who enrolled to the programme was randomly assigned. Thereafter participants were allocated alternatively to either the intervention (WebEase) (n = 96) or a waiting list control group (n = 96). After six weeks (when the intervention group had completed WebEase), those in the waiting list control began the programme as well. Participants completed three questionnaire assessments, at baseline, 6 weeks (when only the intervention group had completed WebEase), and 12 weeks (when both groups had completed WebEase). At each assessment, investigators assessed measures of medication adherence, stress, sleep quality, self management, self efficacy, knowledge, and quality of life. All participants received a gift voucher for an online retailer at the end of their participation in the study.

Aliasgharpour 2013 evaluated an educational programme with the aim of increasing patient self management. The programme consisted of four sessions over one month to groups of four to six participants. In total, 66 participants were randomised to either the educational programme (n = 33) or to a control group (n = 33) who received the usual epilepsy care and support offered by the clinic. The control group also received two brief courtesy telephone calls as a control for attention. Investigators carried out assessments via questionnaire at baseline and at one month. Questionnaires included general measures of demographic details and of disease (i.e. type of convulsions, seizure frequency, time since the last seizure and the number of antiepileptic drugs taken). Trialists measured self management using the Epilepsy Self Management Scale (ESMS).

Strategies to improve patient compliance

Three trials evaluated the effect of strategies to improve patient compliance (Adamolekun 1999; Peterson 1984; Thapar 2002). One recruited participants from general practices in the United Kingdom (Thapar 2002), another from outpatients attending an Australian hospital clinic (Peterson 1984) and the third from the population of the Zvimba health district in rural Zimbabwe (Adamolekun 1999).

A three‐arm cluster‐randomised trial based in general practices in Greater Manchester, England, Thapar 2002 studied the impact of a 'prompt and reminder card' on the care of people with epilepsy. The study included 1275 participants from 82 practices, stratified according to size then allocated to one of three groups using a random number table. Intervention group 1 (n = 368) gave participants the responsibility of keeping the cards (patient‐held card group), and intervention group 2 (n = 515) had the cards placed into patients' records at the practice (doctor‐held card group), while the control group (n = 392) did not use cards.

In their study of outpatients attending a hospital clinic in Hobart, Australia, Peterson 1984 used a range of strategies to improve patient compliance with anticonvulsant therapy. Fifty‐three adults aged between 18 and 74 years entered the trial. Subjects were allocated by coin toss to the control group receiving usual care (n = 26) or the intervention group receiving a package of strategies to improve compliance (n = 27). Outcome measures focused on patient compliance as measured by plasma anticonvulsant levels, prescription refill frequency and appointment keeping.

Adamolekun 1999 evaluated the impact of healthcare worker and patient education on care in their study of epilepsy in rural Zimbabwe. As the team did not establish a control group for the first part of the study on health worker education, we excluded this part from this review. We included the second part of the project: studying the impact of information pamphlets on patient management in 400 participants. Health facilities (a district hospital, a mine hospital, 3 rural hospitals and 20 rural health centres) were randomised to one of two groups. The intervention group received patient information pamphlets for distribution to patients with epilepsy and their relatives at clinic visits. Control facilities did not receive the pamphlets. Impact was measured at six months after receipt of the information, by between‐group comparisons of clinic attendance, seizure frequency and mean serum drug levels.

Self management through screening

One trial based in a university hospital in the USA evaluated the effect of physicians' use of a risk profile (the Adverse Effects Profile, or AEP) on adverse effects of antiepilepsy drugs and on participants' reported subjective health status (Gilliam 2004). Trialists recruited participants attending an epilepsy clinic if their scores on the AEP were 45 or more. In total, 62 adults with epilepsy participated. The AEPs of participants randomised to the intervention group (n = 32) were available to their physicians, while the control group's (n = 30) physicians did not have access. At the end of the four‐month trial, investigators re‐assessed participants' AEPs as well as the changes in seizure rates, and each subject completed the Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory (QOLIE‐89) questionnaire.

Alternative care delivery in outpatient clinics

Prior to 1984, there was no specialist unit for epilepsy patients in Cardiff and South Wales, UK so epilepsy patients would most likely be referred to neurology. Morrow 1990 therefore undertook a randomised controlled trial to evaluate the outpatient activities of a specialist epilepsy unit. Individuals referred to hospital with confirmed or suspected epilepsy were submitted for randomisation to the Epilepsy Unit or to a standard neurology clinic. Because the referring physician did not always grant permission for randomisation, the study recruited 64 non‐randomised and 232 randomised individuals. We have therefore treated the study as a controlled before‐and‐after study (intervention, n = 130; control, n = 102) rather than a randomised trial. Outcome assessors evaluated participants at 3, 6 and 12 months. Outcome measures were seizure control, antiepileptic medication, use of other health resources (such as GP consultations), receipt of advice and counselling, patient satisfaction and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD).

Specialist nurse practitioners

Seven studies reporting on five mutually exclusive study populations evaluated the effects of specialist nurse practitioners (Helde 2005; Mills 1999a; Mills 1999b; Ridsdale 1997; Ridsdale 1999; Ridsdale 2000; Warren 1998). Six studies took place in the UK, four in patients of general practices in southeast England (Mills 1999a; Mills 1999b; Ridsdale 1997; Ridsdale 1999), one in hospitals based in the same region (Ridsdale 2000) and one in a regional epilepsy clinic in northern England (Warren 1998). The remaining study took place in a neurology clinic in Norway (Helde 2005).

Mills 1999a studied the effect of a primary care‐based epilepsy nurse from the perspective of patients in 14 general practices in southeast England. Practices were allocated to either intervention or control to ensure similar distributions of size, doctor:patient ratio, socioeconomic status and mean distance from the local general hospital. The study had 574 participants aged 16 years or over with epilepsy (intervention, n = 278; control, n = 296). Intervention group members received information, advice and support from the epilepsy nurse, who also liaised with other professionals and provided education for staff. Participants filled in a self completion questionnaire based on the Living With Epilepsy survey instrument at baseline and after one year. Outcome measures included seizure frequency, AED use, information provision and attitudes to care. Secondary measures included patient preferences and the effect of epilepsy and treatment on everyday life.

Following the completion of the Mills 1999a study, during the second year, the specialist epilepsy nurse worked with participants who had been in the original control group of seven GP practices. Mills 1999b reported on follow‐up of 394 participants after two years, comparing participants who had accessed the specialist epilepsy nurse (n = 195) with those who had not (n = 194), regardless of their original group allocation. The same self completion questionnaire used at the end of year one was sent out again at the end of year two. Two hundred forty participants responded to both baseline and year two questionnaires: 60.9% of baseline respondents and 40.3% of the 595 participants with epilepsy in the 14 practices at the start of the trial.

Two papers from the UK based Epilepsy Care Evaluation Group reported outcomes from a trial based in six general practices in southern England (Ridsdale 1997;Ridsdale 1999). Two hundred fifty‐one adults with epilepsy (aged 17 to 90) were randomised either to specialist nurse based in general practice (n = 127) or usual care (n = 124). Criteria for exclusion were other severe illness (e.g. terminal cancer), severe psychological illness (e.g. active psychosis or severe depression) and low IQ (i.e. associated with learning disability or dementia). Ridsdale 1997 reported on knowledge of epilepsy, depression and anxiety scores at six months, which they assessed using validated questionnaires before and after the intervention. Ridsdale 1999 reported on patient attendance rate, nurse perception of appropriateness of medical management, and patients' perceptions of level of advice they had received on epilepsy at six months.

A third paper by Ridsdale 2000 reported on nurse specialists in the hospital‐based care of people with newly diagnosed epilepsy. This trial recruited individuals aged 17 or over from the neurology clinics of five hospitals in southeast England. The intervention matched that of the earlier trials (Ridsdale 1997; Ridsdale 1999), but the study was in the hospital setting, with a specialist epilepsy nurse giving two consultations, three months apart. People with learning disability were again excluded. One hundred two participants were randomised to the intervention (n = 54) or usual care (n = 48). Like Ridsdale 1997, the 2000 study measured knowledge of epilepsy, depression and anxiety scores at six months, assessed by validated questionnaires before and after the intervention.

Warren 1998 evaluated an epilepsy nurse specialist case manager who worked in a regional epilepsy clinic in northern England. The nurse complemented the work of the clinic doctors and replaced them in some aspects of care. Warren 1998 recruited 322 people with epilepsy, aged 16 or over, and then randomised them to the intervention (n = 154) or standard care (n = 168). The sample of participants included patients with learning disabilities, and the study authors stated that they excluded 20 for being unable to complete questionnaires; however, in 19 of these instances, their caregiver completed the questionnaire instead. The caregivers of 248 other participants with epilepsy also completed questionnaires. Warren 1998 reported on a wide range of outcomes, including: seizure frequency; anxiety and depression; impact of epilepsy (functioning); knowledge of epilepsy scores; impact on medical management; psychosocial outcomes for patients and caregivers; patient and general practitioner satisfaction with clinic care; use of other hospital services at six months; and costs of treatment.

Helde 2005 recruited 114 adults with epilepsy who attended a neurology clinic at a hospital in Trondheim, Norway into their randomised controlled trial. Using computer‐generated block randomisation, the trial allocated participants to either the intervention group (n = 58), which received counselling and teaching from a specialist epilepsy nurse, or to the control group (n = 56), which continued to receive standard care. Investigators measured primary outcomes using the QOLIE‐89, which they administered two years after recruitment to the trial. In addition, three months after this, each participant gave the clinic a general satisfaction rating by completing a Visual Analogue Scale.

Behavioural interventions

McAuley 2001 evaluated the impact of a structured exercise programme on behavioural and clinical outcomes in a group of adults with epilepsy in Ohio, USA. Twenty‐eight participants aged 16 to 60 years participated in the study, but authors did not describe the source of these participants or recruitment methods. Subjects were randomised to the intervention group (n = 17) or to a control group (n = 11), which received no additional exercise. Trialists conducted baseline physiological evaluations prior to the commencement of the exercise programme, including body composition, maximum oxygen consumption, strength and cardiovascular endurance. They also assessed seizure frequency over the previous four weeks, and monthly after baseline up to 12 weeks, by review of the patients' seizure calendars. All participants also provided AED concentrations (via blood test) and completed the QOLIE‐89 at baseline and 12 weeks.

Guideline implementation and patient information

In primary care settings in Tayside, Scotland, UK, Davis 2004 carried out a three‐arm randomised controlled trial of the use of epilepsy guidelines by general practitioners. General practitioners from 68 general practices were randomised to an intensive intervention (24 practices), an intermediate intervention (22 practices) or control (22 practices). A copy of a nationally developed clinical guideline was posted in all practices. The intermediate intervention group also received interactive, accredited workshops, and dedicated, structured protocol documents. The intensive intervention group received all the elements of the other two arms with the addition of a nurse specialist who supported and educated practices in the establishment of epilepsy review clinics. The primary patient outcome measure was the 36‐item Short Form Health Survey (SF‐36), a general quality of life instrument. Secondary patient outcome measures were epilepsy specific, including the nature and perceived severity of seizures, perceived adverse drug effects, the impact of epilepsy on participants' lives, and their sense of mastery. The study also used the Epilepsy Surgery Inventory 55 Survey (ESI‐55), a cognitive function test. Investigators measured all patient outcomes from completed questionnaires. In total, 3284 participants received a questionnaire, and 1133 entered the study by completing a baseline questionnaire, a response rate of 56%. Of these 1133, 399 participants were in the intensive intervention group, 364 in the intermediate intervention group and 370 in the control group.

Excluded studies

We summarise the characteristics of excluded studies in Characteristics of excluded studies. Three studies assessed interventions that were not specific to epilepsy but were rather generic psychological or mindfulness techniques applied to the epilepsy population (Lundgren 2006; Lundgren 2008; Pramuka 2007). DiIorio 2009 was a feasibility study of an epilepsy self management intervention by telephone, and we excluded it primarily because, as noted by the authors of this study, "the design of the study was not developed to test the efficacy of the intervention". However, the authors later adapted the programme for the Internet (WebEase), and we included the report on that study in the review (DiIorio 2011).

Risk of bias in included studies

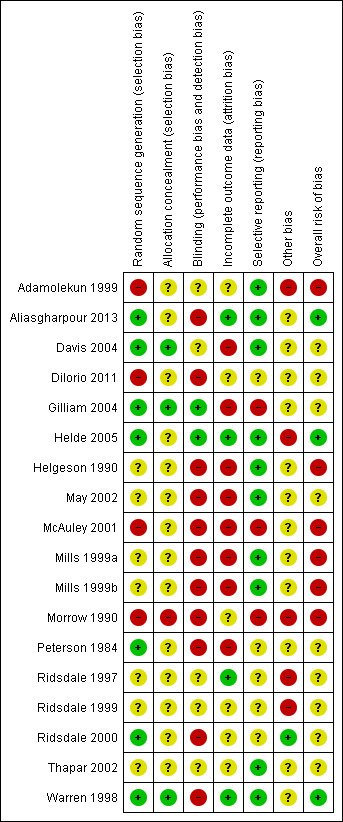

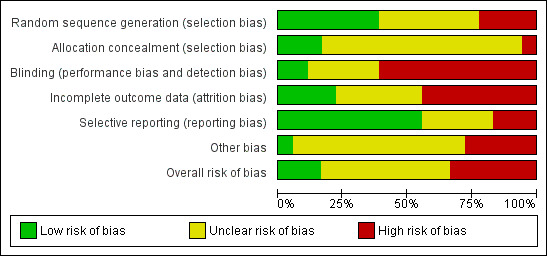

We only judged three studies to be at low overall risk of bias: two studies of specialist nurse practitioners (Aliasgharpour 2013; Helde 2005), and one study of self management education (Warren 1998). We considered six studies to be at high risk of bias: one of the four studies of self management education (Helgeson 1990); one of the three studies to improve patient compliance (Adamolekun 1999); two of the seven studies of specialist nurse practitioners (Mills 1999a; Mills 1999b); the sole study of behavioural interventions (McAuley 2001); and the study of alternative care delivery in outpatient clinics (Morrow 1990). We deemed the remaining nine studies to be have an unclear risk overall: two of the four studies of self management education (DiIorio 2011;May 2002); two studies of strategies to improve patient compliance (Peterson 1984; Thapar 2002); the only study of self management through screening (Gilliam 2004); three of the seven studies of specialist nurse practitioners (Ridsdale 1997;Ridsdale 1999; Ridsdale 2000); and the only study of guideline implementation and patient information (Davis 2004). We detail the assessments for each study in the Characteristics of included studies section and summarise them in Figure 3 and Figure 4 .

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

4.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

We considered the risk of bias for random sequence generation to be unclear for six studies due to a lack of information (Helgeson 1990, May 2002, Mills 1999a, Mills 1999b, Ridsdale 1997, Ridsdale 1999). We also considered Thapar 2002 to have an unclear risk because on the one hand, there were a much higher number of participants in the doctor‐held card group (n = 515) than either the patient‐held card group (n = 368) or the control group (n = 392), which could indicate that the randomisation failed (and carried a high risk of bias). On the other hand, given the cluster‐randomisation design, the imbalance could equally have indicated that there were a greater number of larger sized general practices (in terms of patient numbers as opposed to numbers of general practitioners) in this group, making the overall risk unclear.

We considered the risk of bias for random sequence generation to be low in seven studies because the process appeared to be methodologically sound (Aliasgharpour 2013, Davis 2004, Gilliam 2004, Helde 2005, Peterson 1984, Ridsdale 2000, Warren 1998). We judged the other four studies to be at high risk of bias: Adamolekun 1999 because it was unclear if the intervention and control sites were determined by randomisation or convenience; DiIorio 2011 because it consecutively assigned participants to intervention and control groups; McAuley 2001 because it did not provide details of randomisation, and the numbers of participants between arms were imbalanced (17 in exercise group and 11 in control), suggesting randomisation may have failed; and Morrow 1990 because only 78% of participants were successfully randomised, since both the referring physician and the consultant to whom the subject was referred had to agree that the arm to which the subject was randomised was appropriate.

Allocation concealment

There was a lack of information about treatment allocation in 14 studies (Adamolekun 1999;Aliasgharpour 2013;DiIorio 2011;Helde 2005;Helgeson 1990;May 2002;McAuley 2001;Mills 1999a;Mills 1999b;Peterson 1984;Ridsdale 1997;Ridsdale 1999;Ridsdale 2000;Thapar 2002), so we judged these studies to carry an unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment. We considered the majority of the studies where there was adequate information (n = 3) to be at low risk of bias (Davis 2004;Gilliam 2004;Warren 1998), with only one study considered to be at high risk of bias because there was considerable variation in the size of the intervention and comparison arms and because this was clearly caused by failed randomisation (Morrow 1990). Two other studies (McAuley 2001; Thapar 2002) with unclear risk of bias also had imbalances in the size of treatment arms, which may have been due to a lack of randomisation.

Blinding

Blinding was rare across the studies. Only Gilliam 2004 was double blind in that clinicians and participants were both blinded. Helde 2005 blinded neither clinicians nor participants, but independent research assistants, blinded to treatment allocation, conducted (and presumably analysed) the interviews. Thus, we considered these two studies to be at low risk of bias. We judged 11 studies to be at high risk of bias because of a lack of blinding (Aliasgharpour 2013;DiIorio 2011;Helgeson 1990;May 2002;McAuley 2001;Mills 1999a;Mills 1999b;Morrow 1990;Peterson 1984; Ridsdale 2000;Warren 1998), and 5 studies to be at unclear risk due to a lack of information (Adamolekun 1999;Davis 2004;Ridsdale 1997;Ridsdale 1999;Thapar 2002).

Incomplete outcome data

Overall, dropout rates across the studies were high, and we considered eight studies to be at high risk of attrition bias (Davis 2004;Gilliam 2004;Helgeson 1990;May 2002;McAuley 2001;Mills 1999a;Mills 1999b;Peterson 1984). We considered the risk of bias to be low in four studies (Aliasgharpour 2013;Helde 2005;Ridsdale 1997;Warren 1998) and unclear in a further six studies (Adamolekun 1999; DiIorio 2011; Morrow 1990; Ridsdale 1999; Ridsdale 2000; Thapar 2002). In Ridsdale 1999 22% of participants did not respond at the end of the study. While those who responded did not differ to the non‐responders with respect to key baseline characteristics, it is still unclear if bias could have been introduced. In Ridsdale 2000 dropout was relatively low, but participants lost to follow‐up were significantly younger and at baseline reported not having had a recent epileptic attack, so it was unclear as to the extent, if any, of the risk of bias. In DiIorio 2011 we judged the risk of bias to be unclear because whereas the dropout rate was 24%, investigators did conduct a completer versus non‐completer analysis and an intention‐to‐treat analysis. In Thapar 2002, we considered the risk of bias to be unclear because data from medical records were available for almost all of the enrolled participants (92%), but questionnaires were available for fewer of them (74%). There was a lack of relevant information about dropout rates in Adamolekun 1999 and Morrow 1990, so we assessed the risk of bias to be unclear.

Selective reporting

The majority of studies appeared to report all of the outcomes they planned to. Hence for ten studies (Adamolekun 1999;Aliasgharpour 2013; Davis 2004;Helde 2005;Helgeson 1990;May 2002;Mills 1999a;Mills 1999b;Thapar 2002;Warren 1998), the risk of bias was low. We considered the risk of bias to be high for three studies (Gilliam 2004;McAuley 2001;Morrow 1990). This was because certain outcomes referred to in the Methods were not reported by Adamolekun 1999 and Morrow 1990; in Gilliam 2004 the opposite was the case—outcomes not referred to in the Methods were reported in the Results. In McAuley 2001, although authors stated the study lasted 12 weeks, they reported the outcome measuring physical self concept and self esteem at 16 weeks with no explanation as to why this was the case. Information about selective reporting was insufficient for four studies (Peterson 1984;Ridsdale 1997;Ridsdale 1999;Ridsdale 2000) and hence the risk of bias in these studies was considered to be unclear. The risk of bias was also deemed to be unclear for DiIorio 2011 because while all outcomes detailed in the methods were referred to in the results, not all values were presented for these analyses.

Other potential sources of bias

Most of the studies had other potential risks of bias. The most common reason resulting in high or unclear risk of bias was lack of reporting on power calculations and required sample size. This occurred in 12 studies (Adamolekun 1999;DiIorio 2011;Gilliam 2004;Helde 2005;Helgeson 1990;May 2002;McAuley 2001;Mills 1999b;Morrow 1990;Peterson 1984;Ridsdale 1997;Ridsdale 1999). Davis 2004 and Thapar 2002 did report power calculations and the required sample size, although the numbers of participants in each group fell short of that target. On the other hand, Warren 1998 reported a required sample size, but it was not clear if this was the result of a power calculation. For the most part, where reported, no differences in baseline characteristics were apparent, exceptions being between treatment arms in four studies (Aliasgharpour 2013, Helde 2005, Mills 1999a, Mills 1999b) and between randomised and non‐randomised participants in Morrow 1990. Nevertheless, the potential risk of bias was deemed unclear due to these uncertainties. Other potential biases that resulted in studies being deemed at high risk of bias were present in Adamolekun 1999;Helgeson 1990;Morrow 1990;Ridsdale 1997 and Ridsdale 1999. In Adamolekun 1999 it was unclear if pre and postintervention periods for study and control sites were the same and if control sites were comparable with respect to health system, level of care, setting of care and educational level among participants. Statistical methods did not account for outcomes that may have varied according to the individual clinics. We also considered that there was a possibility of contamination in this study, as patient information could easily have been distributed to control sites. Helgeson 1990 reported no details of power calculations or required sample size. Furthermore, the intervention group completed the pre‐assessment questionnaire immediately before participating in the programme, whereas the control group participants were sent the questionnaire by post one week earlier. Similarly, Morrow 1990, did not report the power calculations or the required sample size, and there were also significant differences at baseline between participants who were randomised and not randomised. Ridsdale 1997 and Ridsdale 1999 also failed to report power calculations and sample size, and in addition, participants in the intervention group were told that they would attend a 'neurology clinic', which they may have interpreted as specialist care. This belief may have potentially improved participant outcomes over and above the effects of the intervention from the epilepsy nurse specialist.

Effects of interventions

The presentation of results varied considerably between trials and we have been unable to report statistics in an optimal way because of the limitations of the data presented. We considered reporting all continuous outcomes as mean difference (MD), but several trials had baseline measures which would require imputing pre‐post correlation. Moreover, given that the populations, interventions, study design, treatment settings and outcome measures differed for each trial, we concluded that meta‐analysis of the results, even within the same type of outcome, would be inappropriate. We have therefore presented the results of the trials narratively. Thus, all results are presented as originally reported, with standard errors transformed to standard deviations. We have only presented the findings reported that could be considered to match the pre‐defined outcomes of our review. A simple descriptive summary of the results, highlighting where there were significant differences between groups over time, are presented in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3,Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7.

1. Seizure frequency and severity.

| Study | Intervention type | Outcome(s) measured | Outcome time | Findings |

| Adamolekun 1999 | Patient compliance – information pamphlets | Seizure frequency per month | 6 months | No statistically significant difference between groups |

| Gilliam 2004 | Self management through screening ‐ Adverse Effects Profile | Seizure frequency per month | 4 months | No statistically significant difference between groups although seizure frequency decreased in intervention group and increased in control group |

| Helgeson 1990 | Self management education ‐ Sepulveda Epilepsy Education | Seizure frequency per month | 4 months | No statistically significant difference between groups |

| May 2002 | Self management education ‐ MOSES | Seizure frequency (as measured on a scale of 0 to 5, i.e. no seizures in past six months to one or more seizure per day) | 6 months | Statistically significant reduction in seizure frequency (improvements ≥2 points on seizure frequency scale) in favour of intervention vs control |

| McAuley 2001 | Behavioural intervention ‐ structured exercise programme | Seizure frequency from previous 4 weeks | 12 weeks | No apparent difference between groups; however, no formal statistical tests are reported |

| Mills 1999a | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | One or more seizure attacks in last year | 1 year | No statistically significant difference between groups |

| Mills 1999a | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | One or more seizure attacks per month in last year | 1 year | No statistically significant difference between groups |

| Mills 1999b | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | One or more seizure attacks in last year | 2 years | No statistically significant difference between groups |

| Mills 1999b | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | One or more seizure attacks per month in last year | 2 years | No statistically significant difference between groups |

| Morrow 1990 | Alternative care delivery in outpatient clinics – specialist epilepsy unit | Seizure frequency in the last three months | 3, 6, 12 months | Seizure frequency reduced to zero in intervention group by 12 months (statistically significant over time) and to one in control group (not statistically significant over time) |

| Morrow 1990 | Alternative care delivery in outpatient clinics – specialist epilepsy unit | Proportion of participants who were seizure free | 3, 6, 12 months | Differences between groups but were not statistically significant at 12 months (but favoured intervention at 3 and 6 months) |

| Morrow 1990 | Alternative care delivery in outpatient clinics – specialist epilepsy unit | Proportion of participants who experienced a 50% reduction in seizure activity from baseline | 3, 6, 12 months | Differences between groups but were not statistically significant at 12 months (but favoured intervention at 3 and 6 months) |

| Peterson 1984 | Patient compliance ‐ combination of compliance‐improving strategies | Median number of seizures in preceding 6 months | 6 months | Seizure frequency reduced significantly in the intervention group but not in the control group; not reported if differences between groups |

| Ridsdale 2000 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ hospital | Number of months since last seizure | 6 months | No statistically significant difference between groups |

| Thapar 2002 | Patient compliance ‐ prompt and reminder card | Recording of seizure frequency | 1 year | No statistically significant difference between the control and the doctor‐held groups and the control and the patient‐held groups |

| Thapar 2002 | Patient compliance ‐ prompt and reminder card | Self‐reported seizure frequency | 1 year | No statistically significant difference between the control and the doctor‐held groups and the control and the patient‐held groups |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | Seizure frequency (more than one seizure per month, one or fewer seizures per month, or seizure‐free) | 6 months | No statistically significant difference between groups |

Note: presented findings only include studies reporting on outcome of interest. All numerical data (including P values), where available, reported in text of report

2. Appropriateness and volume of medication prescribed (including evidence of drug toxicity).

| Study | Intervention type | Outcome(s) measured | Outcome time | Findings |

| Adamolekun 1999 | Patient compliance – information pamphlets | Drug compliance | 6 months | No statistically significant difference between groups |

| DiIorio 2011 | Self management education ‐ WebEase | Self reported medication adherence | 12 weeks | Statistically significant improvement in favour of intervention group |

| Gilliam 2004 | Self management through screening ‐ Adverse Effects Profile | AED dose changes | 4 months | Statistically significantly greater number of dose changes in intervention group compared with control group |

| Gilliam 2004 | Self management through screening ‐ Adverse Effects Profile | Adverse events profile relative improvement | 4 months | Mean improvement in adverse events profile scores was statistically significantly greater in intervention group vs control |

| Helgeson 1990 | Self management education ‐ Sepulveda Epilepsy Education | Hazardous medical self management practices subscale | 4 months | Statistically significant group‐time interaction effects in favour of intervention vs control |

| Helgeson 1990 | Self management education ‐ Sepulveda Epilepsy Education | Compliance (as measured by blood antiepileptic drug levels) | 4 months | In a subset of the study population, statistically significant increase in compliance in favour of intervention group |

| May 2002 | Self management education ‐ MOSES | Tolerability of antiepileptic drug treatment | 6 months | Statistically significant improvement in tolerability in favour of intervention group over time |

| McAuley 2001 | Behavioural intervention ‐ structured exercise programme | Variation in AED concentrations (measured by serum carbamazepine, phenytoin, and valproic acid concentrations, as applicable) | 12 weeks | No apparent differences between intervention and control groups; however, no formal statistical tests are reported |

| Mills 1999a | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Taking one type of antiepileptic drug | 1 year | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Mills 1999a | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Feel very well controlled by drug | 1 year | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Mills 1999a | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Report very important to take tablets exactly as prescribed | 1 year | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Mills 1999a | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Report never missing taking their antiepileptic drugs | 1 year | Statistically significantly in favour of intervention group |

| Mills 1999a | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Side effects from drugs (in past month) | 1 year | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Mills 1999b | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Taking one type of antiepileptic drug | 2 years | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Mills 1999b | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Feel very well controlled by drug | 2 years | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Mills 1999b | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Report very important to take tablets exactly as prescribed | 2 years | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Mills 1999b | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Report never miss taking antiepileptic drugs | 2 years | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Mills 1999b | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Side effects from drugs (in past month) | 2 years | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Morrow 1990 | Alternative care delivery in outpatient clinics – specialist epilepsy unit | Number and type of antiepileptic drugs or the number of drugs prescribed per patient | During study period | No statistically significant difference between groups |

| Morrow 1990 | Alternative care delivery in outpatient clinics – specialist epilepsy unit | Reduction in the percentage of drug concentrations outside the reference range | 6 and 12 months | Statistically significant reduction in the percentage of drug concentrations outside the reference range in intervention vs control at both time points |

| Morrow 1990 | Alternative care delivery in outpatient clinics – specialist epilepsy unit | Adverse drug effects (ADRs) | 3, 6, 12 months | Statistically significant reduction in the percentage of ADRs in the intervention group at 6 and 12 months |

| Peterson 1984 | Patient compliance ‐ combination of compliance‐improving strategies | Compliance in terms of plasma level of antiepileptic drugs | 6 months | Statistically significant differences in mean plasma levels/dose for phenytoin and carbamazepine but not sodium valproate. Plasma levels of phenytoin, carbamazepine, and sodium valproate substantially increased within the intervention but not control group |

| Peterson 1984 | Patient compliance ‐ combination of compliance‐improving strategies | Prescription refill frequency | 6 months | Statistically significant in favour of intervention; over time, compliance increased in intervention group but not control group |

| Peterson 1984 | Patient compliance ‐ combination of compliance‐improving strategies | Clinic attendance | 6 months | No statistically significant difference between groups |

| Ridsdale 1997 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Appropriateness of medication supplied | 6 months | 11.1% of intervention patients required changes; no data reported for control |

| Ridsdale 1997 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Increase serum concentration monitoring | 6 months | Statistically significant increase in serum monitoring over time in intervention group compared with control group |

| Thapar 2002 | Patient compliance ‐ prompt and reminder cards | Proportion of patients taking only one antiepileptic drug (monotherapy) | 1 year | No statistically significant difference between either intervention group and control |

| Thapar 2002 | Patient compliance ‐ prompt and reminder cards | Checking of phenytoin levels | 1 year | No statistically significant difference between either intervention group and control |

| Thapar 2002 | Patient compliance ‐ prompt and reminder card | Side effects from medication | 1 year | Statistically significantly higher levels of side effects in doctor‐held card group vs control and patient‐held card group vs control group |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | Self reported non‐compliance with medication | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | Attendance at epilepsy clinic | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

Note: presented findings only include studies reporting on outcome of interest. All numerical data (including P values), where available, reported in text of report

AED: antiepileptic drug.

3. Patients’ reported knowledge of information and advice received from professionals.

| Study | Intervention type | Outcome(s) measured | Outcome time | Findings |

| Study | Intervention type | Outcome(s) measured | Outcome time | Findings |

| DiIorio 2011 | Self management education ‐ WebEase | Knowledge about epilepsy | 12 weeks | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Helgeson 1990 | Self management education ‐ Sepulveda Epilepsy Education | Fear of death and brain damage due to seizures | 4 months | Statistically significant decrease in level of fear in favour of intervention vs control |

| Helgeson 1990 | Self management education ‐ Sepulveda Epilepsy Education | Extent of overall misinformation and misconceptions regarding epilepsy | 4 months | Statistically significant decrease in overall level of misinformation and misconceptions regarding epilepsy in favour of intervention vs control |

| May 2002 | Self management education ‐ MOSES | Epilepsy knowledge | 6 months | Statistically significant increase in level of knowledge in favour of intervention vs control over time |

| Mills 1999a | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Discussed epilepsy topics with GP | 1 year | Of 11 topics, patients in the intervention group were statistically significantly more likely to have discussed 4 topics with primary care staff and 2 topics with hospital staff |

| Mills 1999b | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Discussed epilepsy topics with GP | 2 years | Of 11 topics, patients in the intervention group were statistically significantly more likely to have discussed 8 topics with primary care staff and 2 topics with hospital doctors |

| Morrow 1990 | Alternative care delivery in outpatient clinics – specialist epilepsy unit | Number of information items offered to participants | 1 year | Groups were not compared with each other but there was an increase in number of items offered over time in intervention group but not control group |

| Ridsdale 1999 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Knowledge of epilepsy | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Ridsdale 2000 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Knowledge of epilepsy | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups although improved over time in intervention group |

| Ridsdale 2000 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ hospital | Advice provided on epilepsy‐related topics | 6 months | Of 9 topics, patients in the intervention group were statistically significantly more likely to have received enough advice on 8 topics with primary care staff |

| Thapar 2002 | Patient compliance ‐ prompt and reminder card | Information provision from professionals | 1 year | Participants in doctor‐held card group were statistically significantly less satisfied with information provision about epilepsy Compared with the control group but not in the patient‐held card group where there were no differences between groups |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | Medical knowledge of epilepsy | 6 months | Statistically significant difference in level of knowledge in favour of intervention |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | Social knowledge of epilepsy | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

Note: presented findings only include studies reporting on outcome of interest. All numerical data (including P values), where available, reported in text of report

4. Patients’ reports of health and quality of life.

| Study | Intervention type | Outcome type | Outcome time | Findings |

| Study | Intervention type | Outcome type | Outcome time | Findings |

| Aliasgharpour 2013 | Self management education | Self management levels | 1 month | Statistically significantly higher levels of self management in intervention group vs control group; there were statistically significant differences over time in the intervention group but not control group |

| Davis 2004 | Guideline implementation and patient information | General quality of life (SF‐36) | 6 months to 1 year | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Davis 2004 | Guideline implementation and patient information | Epilepsy specific quality of life | 6 months to 1 year | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| DiIorio 2011 | Self management education ‐ WebEase | Perceived stress | 12 weeks | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| DiIorio 2011 | Self management education ‐ WebEase | Sleep quality | 12 weeks | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| DiIorio 2011 | Self management education ‐ WebEase | Self management | 12 weeks | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| DiIorio 2011 | Self management education ‐ WebEase | Self efficacy | 12 weeks | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| DiIorio 2011 | Self management education ‐ WebEase | Quality of life | 12 weeks | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Gilliam 2004 | Self management through screening ‐ Adverse Effects Profile | Quality of life in Epilepsy (QOLIE‐89) | 4 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Helde 2005 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ neurology | Quality of life in Epilepsy (QOLIE‐89) | 2 years | No statistically significant differences between groups overall but some statistically significant improvements reported for individual domains over time in both groups |

| Helgeson 1990 | Self management education ‐ Sepulveda Epilepsy Education | Acceptance of disability | 4 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Helgeson 1990 | Self management education ‐ Sepulveda Epilepsy Education | Depression | 4 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Helgeson 1990 | Self management education ‐ Sepulveda Epilepsy Education | Anxiety | 4 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Helgeson 1990 | Self management education ‐ Sepulveda Epilepsy Education | Self efficacy ‐ general | 4 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Helgeson 1990 | Self management education ‐ Sepulveda Epilepsy Education | Self efficacy ‐ social | 4 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Helgeson 1990 | Self management education ‐ Sepulveda Epilepsy Education | Overall psychosocial functioning | 4 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| May 2002 | Self management education ‐ Sepulveda Epilepsy Education | Coping with epilepsy | 6 months | Statistically significant increase in coping with epilepsy in intervention group vs control group over time |

| May 2002 | Self management education ‐ Sepulveda Epilepsy Education | Restriction in daily living | 6 months | Statistically significant decrease in restriction in daily living intervention group over time but no statistically significant differences between groups |

| May 2002 | Self management education ‐ Sepulveda Epilepsy Education | Mobility and leisure behaviour | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups but statistically significant improvement over time in intervention group |

| May 2002 | Self management education ‐ Sepulveda Epilepsy Education | Epilepsy‐related fear | 6 months | Statistically significant decrease in epilepsy related fear in intervention group over time but no statistically significant differences between groups |

| May 2002 | Self management education ‐ Sepulveda Epilepsy Education | Stigma | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups or over time |

| May 2002 | Self management education ‐ Sepulveda Epilepsy Education | SF‐36 physical functioning | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups or over time |

| May 2002 | Self management education ‐ Sepulveda Epilepsy Education | SF‐36 mental functioning | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups or over time |

| May 2002 | Self management education ‐ Sepulveda Epilepsy Education | Self esteem | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups or over time |

| May 2002 | Self management education ‐ Sepulveda Epilepsy Education | Depression | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups or over time |

| McAuley 2001 | Behavioural intervention ‐ structured exercise programme | Quality of life in Epilepsy (QOLIE‐89) | 12 weeks | Statistically significant improvement over time (overall) in intervention group and statistically significant improvements reported for individual domains over time in both groups; no formal statistical tests between groups are reported |

| McAuley 2001 | Behavioural intervention ‐ structured exercise programme | Mood State including tension, depression, anger, vigour and confusion | 12 weeks | Statistically significant improvement over time for vigour; no formal statistical tests between groups are reported at end of study but it is noted that there were statistically significant differences between groups at baseline |

| McAuley 2001 | behavioural intervention ‐ structured exercise programme | Self esteem | 12 weeks | No statistically significant differences over time in either group; no formal statistical tests between groups are reported |

| McAuley 2001 | Behavioural intervention ‐ structured exercise programme | Physical self concept and vigour | 12 and 16 weeks | Statistically significant difference over time in intervention group overall and for the following domains: physical activity, coordination, endurance and strength; no formal statistical tests between groups are reported |

| Mills 1999a | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | 10 questions about quality of life | 1 year | Intervention group statistically significantly more likely to report an effect for three items: Epilepsy affects future plans and ambitions, Epilepsy affects overall health, Epilepsy affects standard of living |

| Mills 1999a | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Feel stigmatised due to epilepsy | 1 year | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Mills 1999a | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Feel unhappy about life as a whole | 1 year | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Mills 1999b | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | 10 questions about quality of life | 2 years | Intervention group statistically significantly more likely to report an effect for three items: Epilepsy impacts on overall health, the way individuals feel about themselves and the impact of epilepsy on their social life/activities |

| Mills 1999b | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Feel stigmatised due to epilepsy | 2 years | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Mills 1999b | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Feel unhappy about life as a whole | 2 years | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Morrow 1990 | Alternative care delivery in outpatient clinics – specialist epilepsy unit | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale | 12 months | Groups were not compared but no statistically significant change over time in either group was reported |

| Ridsdale 1999 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Depression | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups in patients who had had a seizure but statistically significantly reduced risk of depression in patients reporting no seizures |

| Ridsdale 2000 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ hospital | Anxiety | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Ridsdale 2000 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ hospital | Depression | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | Self rated health status (quality of life) as measured by EuroQoL | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | Weighted health status (quality of life) as measured by EuroQoL | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | Social functioning | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | Social outcomes | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | Anxiety | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | Depression | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

Note: presented findings only include studies reporting on outcome of interest. All numerical data (including P values), where available, reported in text of report

SF‐36: 36‐item Short Form Health Survey; QOLIE‐89: Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory.

5. Objective measures of general health status.

| Study | Intervention type | Outcome type | Outcome time | Findings |

| Mills 1999a | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Long‐term health problems | 1 year | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Mills 1999a | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Injury as a result of epilepsy attack (in past year) | 1 year | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Mills 1999b | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Injury as a result of epilepsy attack (in past year) | 2 years | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | Injuries from seizures | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

Note: Presented findings only include studies reporting on outcome of interest. All numerical data (including P values), where available, reported in text of report

6. Objective measures of social or psychological functioning (including the number of days spent on sick leave/absent from school and work, and employment status).

| Study | Intervention type | Outcome type | Outcome time | Findings |

| Morrow 1990 | Alternative care delivery in outpatient clinics – specialist epilepsy unit | Social activities | 1 year | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Morrow 1990 | Alternative care delivery in outpatient clinics – specialist epilepsy unit | Employment status | 1 year | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | Number of days absent from work | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

Note: presented findings only include studies reporting on outcome of interest. All numerical data (including P values), where available, reported in text of report

7. Costs of care or treatment.

| Study | Intervention type | Outcome type | Outcome time | Findings |

| Adamolekun 1999 | Patient compliance – information pamphlets | Patient non‐attendance at clinic | 6 months | No statistically significant difference between groups in magnitude of the change in attendance |

| Gilliam 2004 | Self management through screening ‐ Adverse Effects Profile | Mean number of clinic visits | 4 months | Significantly greater number of clinic visits were recorded by intervention group vs control group |

| Mills 1999a | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Seen GP for any reason | 1 year | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Mills 1999a | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Seen GP for epilepsy | 1 year | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Mills 1999a | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Seen hospital doctor for epilepsy | 1 year | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Mills 1999a | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Admitted to hospital for epilepsy | 1 year | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Mills 1999a | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Attended A&E department for epilepsy | 1 year | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Mills 1999a | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Regular arrangement to see GP for epilepsy | 1 year | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Mills 1999b | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Seen GP for any reason | 1 year | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Mills 1999b | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Seen GP for epilepsy | 1 year | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Mills 1999b | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Seen hospital doctor for epilepsy | 1 year | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Mills 1999b | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Admitted to hospital for epilepsy | 1 year | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Mills 1999b | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Attended A&E department for epilepsy | 1 year | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Mills 1999b | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ general practice | Regular arrangement to see GP for epilepsy | 1 year | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Morrow 1990 | Alternative care delivery in outpatient clinics – specialist epilepsy unit | Number of outpatient clinic visits | 1 year | Numerically there were a greater number of visits to the epilepsy clinic than to the neurology clinic, but groups were not formally compared with each other |

| Morrow 1990 | Alternative care delivery in outpatient clinics – specialist epilepsy unit | Visits to outpatient clinic doctor | 1 year | Numerically there were a greater number of visits to the clinic doctor in the specialist unit than in the neurology clinic, but groups were not formally compared with each other |

| Morrow 1990 | Alternative care delivery in outpatient clinics – specialist epilepsy unit | GP consultations | 1 year | Numerically the number of GP consultations by the neurology clinic patients was higher than the epilepsy clinic patients, but groups were not formally compared with each other |

| Morrow 1990 | Alternative care delivery in outpatient clinics – specialist epilepsy unit | Inpatient days | 1 year | Numerically the number of inpatients days by the neurology clinic patients was higher than the epilepsy clinic patients, but groups were not formally compared with each other |

| Peterson 1984 | Patient compliance ‐ combination of compliance‐improving strategies | Clinic appointment keeping | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | ≥ 1 GP consultations | 6 months | A smaller proportion of intervention patients saw their GP once or more than did control patients but this difference was not statistically significant; |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | Number of GP consultations | 6 months | Intervention patients had statistically significantly fewer consultations than the control group |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | Visits to general practice nurse | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | Visits made by district nurse | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | Visits made by health visitor | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | Visits made by CPN | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | Visits to outpatient clinic doctor | 6 months | Intervention patients made statistically significantly fewer visits to the outpatient clinic doctor than did control patients |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | Specialist outpatient clinic psychiatrist consultation | 6 months | Numerically intervention patients made more visits to outpatients clinics than did patients to the control group but groups were not formally compared with each other |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | Specialist outpatient clinical psychologist consultation | 6 months | Numerically intervention patients made more visits to outpatients clinics than did patients to the control group but groups were not formally compared with each other |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | Specialist inpatient admission | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | EEG | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | CT scan | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | MR scan | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | Other outpatient consultation | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |

| Warren 1998 | Specialist nurse practitioner ‐ regional epilepsy clinic | Other inpatient admission | 6 months | No statistically significant differences between groups |