Abstract

Background

The proportion of total healthcare expenditures spent on drugs has continued to grow in countries of all income categories. Policy‐makers are under pressure to control pharmaceutical expenditures without adversely affecting quality of care. Financial incentives seeking to influence prescribers' behaviour include budgetary arrangements at primary care and hospital settings (pharmaceutical budget caps or targets), financial rewards for target behaviours or outcomes (pay for performance interventions) and reduced benefit margin for prescribers based on medicine sales and prescriptions (pharmaceutical reimbursement rate reduction policies). This is the first update of the original version of this review.

Objectives

To determine the effects of pharmaceutical policies using financial incentives to influence prescribers' practices on drug use, healthcare utilisation, health outcomes and costs (expenditures).

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (searched 29/01/2015); MEDLINE, Ovid SP (searched 29/01/2015); EMBASE, Ovid SP (searched 29/01/2015); International Network for Rational Use of Drugs (INRUD) Bibliography (searched 29/01/2015); National Health Service (NHS) Economic Evaluation Database (searched 29/01/2015); EconLit ‐ ProQuest (searched 02/02/2015); and Science Citation Index and Social Sciences Citation Index, Institute for Scientific Information (ISI) Web of Knowledge (citation search for included studies searched 10/02/2015). We screened the reference lists of relevant reports and contacted study authors and organisations to identify additional studies.

Selection criteria

We included policies that intend to affect prescribing by means of financial incentives for prescribers. Included in this category are pharmaceutical budget caps or targets, pay for performance and drug reimbursement rate reductions and other financial policies, if they were specifically targeted at prescribing or drug utilisation. Policies in this review were defined as laws, rules, regulations and financial and administrative orders made or implemented by payers such as national or local governments, non‐government organisations, private or social insurers and insurance‐like organisations. One of the following outcomes had to be reported: drug use, healthcare utilisation, health outcomes or costs. The study had to be a randomised or non‐randomised trial, an interrupted time series (ITS) analysis, a repeated measures study or a controlled before‐after (CBA) study.

Data collection and analysis

At least two review authors independently assessed eligibility for inclusion of studies and risks of bias using Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) criteria and extracted data from the included studies. For CBA studies, we reported relative effects (e.g. adjusted relative change). The review team re‐analysed all ITS results. When possible, the review team also re‐analysed CBA data as ITS data.

Main results

Eighteen evaluations (six new studies) of pharmaceutical policies from six high‐income countries met our inclusion criteria. Fourteen studies evaluated pharmaceutical budget policies in the UK (nine studies), two in Germany and Ireland and one each in Sweden and Taiwan. Three studies assessed pay for performance policies in the UK (two) and the Netherlands (one). One study from Taiwan assessed a reimbursement rate reduction policy. ITS analyses had some limitations. All CBA studies had serious limitations. No study from low‐income or middle‐income countries met the inclusion criteria.

Pharmaceutical budgets may lead to a modest reduction in drug use (median relative change ‐2.8%; low‐certainty evidence). We are uncertain of the effects of the policy on drug costs or healthcare utilisation, as the certainty of such evidence has been assessed as very low. Effects of this policy on health outcomes were not reported. Effects of pay for performance policies on drug use and health outcomes are uncertain, as the certainty of such evidence has been assessed as very low. Effects of this policy on drug costs and healthcare utilisation have not been measured. Effects of the reimbursement rate reduction policy on drug use and drug costs are uncertain, as the certainty of such evidence has been assessed as very low. No included study assessed the effects of this policy on healthcare utilisation or health outcomes. Administration costs of the policies were not reported in any of the included studies.

Authors' conclusions

Although financial incentives are considered an important element in strategies to change prescribing patterns, limited evidence of their effects can be found. Effects of policies, including pay for performance policies, in improving quality of care and health outcomes remain uncertain. Because pharmaceutical policies have uncertain effects, and because they might cause harm as well as benefit, proper evaluation of these policies is needed. Future studies should consider the impact of these policies on health outcomes, drug use and overall healthcare expenditures, as well as on drug expenditures.

Plain language summary

The effects of financial incentives for prescribers

This review is the first update of the Cochrane review of the effects of different financial policies seeking to influence prescriber behaviour. Researchers at The Cochrane Collaboration searched for all studies that could answer this question and found 18 studies. Their findings are summarised below.

What are financial incentives for prescribers?

Large amounts of healthcare funds are spent on medicines, and these amounts are increasing. Increased spending on medicines could mean less money for other healthcare or non‐healthcare services. Health insurers and policy‐makers are therefore looking for ways to ensure better use of medicines and to control the costs of medicines while still ensuring that patients get the medicines they need.

One way to try to control medicine spending is to influence the people who prescribe medicines, for instance, through financial incentives. One way of doing this involves introducing a budget cap or a budget target. Here, doctors and healthcare organisations are given a budget and the responsibility of staying within this budget. Another approach is to enforce a pay for performance policy, whereby doctors or their organisations are financially rewarded or punished for their prescribing behaviour. A third approach is to apply a reimbursement rate policy. Here, the amount of money doctors are reimbursed for medicine prescriptions is reduced, making the prescription of medicines less financially attractive to doctors.

These policies may lead doctors to prescribe fewer or cheaper medicines. This may reduce the use of unnecessary medicines but may also lead to poorer health outcomes.

What happens when financial incentives for prescribers are introduced?

Pharmaceutical budget caps or targets:

‐ This policy may lead to a modest reduction in overall drug use per patient (low‐certainty evidence).

‐ We are uncertain of the effects of this policy on drug costs or on healthcare utilisation, as the certainty of the evidence has been assessed as very low.

‐ The effects of this policy on health outcomes have not been measured.

Pay for performance policies:

‐ We are uncertain of the effects of these policies on drug use or health outcomes, as the certainty of the evidence has been assessed as very low.

‐ The effects of this policy on drug costs or on healthcare utilisation have not been measured.

Reimbursement rate policies:

‐ We are uncertain about the effects of reimbursement rate policies because the quality of the evidence has been assessed as very low.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

The review authors searched for studies that had been published up to January 2015.

Summary of findings

Background

This is the first update of the original review (Sturm 2007).

Description of the condition

The proportion of total healthcare expenditures spent on drugs has continued to grow in numerous countries over past decades (Reinhardt 2002; Granlund 2006; Okunade 2006; Martens 2007), and it has increased about 50% from 1995 to 2006 (Lu 2011). For instance in the UK and Spain, drug costs in primary care consumed over 50% of total primary care expenditures (Bradlow 1993; Antonanzas 2003). Although the growth rate has slowed in recent years, growth in pharmaceutical expenditures continues at a considerably faster rate than the general economy (Doloresco 2011). Middle‐income countries have observed a faster pace of pharmaceutical expenditure growth than low‐ or high‐income countries (Lu 2011). This is particularly the case for the high‐growth pharmaceutical markets of 17 low‐ and middle‐income 'pharmerging' countries as defined by IMS Health (Campbell 2013) and a few others not covered by IMS analyses.

In many low‐ and middle‐income countries, prescribing costs represent a major portion of total healthcare expenditures (Lu 2011). In low‐ and lower‐middle‐income countries, an even bigger proportion of the total health expenditures is spent on medicines (on average about 27% to 30% of total health expenditures), and affordability barriers hinder access to medicines, as many households are not supported by reliable financial mechanisms to secure such access (Steinbrook 2007; Lu 2011). Recent studies in different regions of the world have highlighted important concerns about access to and use of medicines in low‐ and middle‐income countries (Bigdeli 2013; Zaidi 2013; Sarayani 2014), and limited research evidence is available to guide the decisions of policy‐makers (Rashidian 2013; Emmerick 2013). It has been demonstrated that evidence on financing and health systems‐related decisions in low‐ and middle‐income countries is meagre (Rashidian 2013).

Thus, policy‐makers are under pressure to control pharmaceutical expenditures without adversely affecting the quality of care. Unexplained variations in prescribing between individual physicians, differences among settings and countries (Sturm 2005) and the fact that evidence and prescribing recommendations reflected in clinical practice guidelines often are not adequately put into practice (Feely 1999; Rashidian 2008) are reasons for implementing regulatory measures, including financial policies, targeted at prescribers to improve the quality of prescribing. Policy‐makers’ need for evidence continues to grow, but rigorous evaluations of regulatory measures are sparse.

Description of the intervention

Financial incentives for influencing prescribers' behaviour can be categorised into the following groups: budgetary arrangements at primary care and hospital settings (pharmaceutical budget caps or targets), financial rewards for target behaviours or outcomes (pay for performance interventions) and reduced benefit margins for prescribers based on medicine sales and prescriptions (pharmaceutical reimbursement rate reduction policies).

Budgetary arrangements for pharmaceuticals may be included in global budget decisions, whereby a proportion of a global budget is earmarked for prescribing pharmaceuticals, or they may be enacted as stand‐alone budgetary decisions for prescribing. For example, in the UK, a Primary Care Trust was "responsible for setting a prescribing budget against each practice" within its catchment area, and in Taiwan, global budgets were used to influence prescribers' behaviour in hospitals (Chou 2010). Financial rewards or incentives for target behaviours and outcomes constitute another type of financial incentive that is used with increasing frequency around the world (Giuffrida 2000; Rosenthal 2006; Rowe 2006; Trude 2006). Other interventions, including interventions that target the margin of benefit from medicine sales for dispensing physicians, may impact prescribing behaviours. For example, in 2004, Medicare changed the way it pays for injectable medicines administered in the office, to reduce physicians' margins of financial benefit derived from certain prescriptions (Painter 2005).

Other monetary regulations, such as remuneration for physicians, can also influence prescribing. However, these do not specifically target prescribing and generally are not considered pharmaceutical policies. Restriction of reimbursement for patients might also affect prescribing by physicians (Austvoll‐Dahlgren 2008), as might other pharmaceutical policies such as reference pricing. These policies are not intended as financial incentives for prescribers and are covered in other systematic reviews (Aaserud 2006a; Acosta 2014). Pharmaceutical policies that use financial incentives for prescribers, which are included in this review, are therefore limited to the three categories of interventions explained below.

How the intervention might work

Pharmaceutical budget caps or targets

Budgets are funds allocated by payers to an individual physician or a group of physicians, thereby giving physicians financial responsibility for management of their own budget (Wilton 1998). Budgets therefore encourage economic behaviours and offer incentives for savings. Drug budgets in particular seek to decrease prescribing costs. Budgets vary with respect to the level at which they are set (individual practice or collective budgets), the range of services covered and the intensity of the incentives (rewards or risks).

In general, individual providers or institutions or physician representatives and the payer negotiate a budget, depending on whether the budget is prepared on a practice, group or regional/national level. Payers are represented by a (regional) health authority (e.g. in the UK and Ireland), a social health insurance scheme (e.g. in Germany) or a managed care organisation (e.g. in the USA). Budgets usually are based on previous spending, adjusted to patient mix or a defined target (e.g. average spending on comparable practices; reduction in overall health care spending, as in Italy). Most budgetary interventions were introduced in the early to mid 1990s and have been adapted or abolished over time. Budgets provide incentives to prescribe fewer and less expensive drugs. Physicians can modify drug volume by changing the dosage or duration of treatment. Costs per item can be limited by increasing the use of generics or other less expensive drugs with equivalent effects. Theoretically this approach can slow the uptake of expensive new drugs with marginal benefits.

The intensity of the incentive is modified by several factors, such as the magnitude of the financial risk involved. Incentives can take the form of potential fines (Germany, France) (Mossialos 2005), savings to be used for improvement of medical services as in the UK (Coulter 1993) or Ireland (Walley 2000) or salary bonuses as in Spain or the USA (Antonanzas 2003; Conrad 2004). Incentives seems to be more direct and stronger if applied at an individual level rather than at a group level. Also the effect of incentives may depend on how much the budget level (target) is adapted to provider‐specific circumstances. For instance, in the UK high‐cost patients and in Germany specific drug classes are exempt (Wilton 1998). The amount, type and timing of prescribing information available to budget holders are important for enabling prescribers to react (Schreyögg 2005). Lack of useful information can be an impediment to effective contracting (Wilton 1998). Low perceived financial risk will decrease the strength of the incentive and will vary according to the likelihood that fines are actually executed or whether the results are derived through personal behaviour versus behaviours of a whole group.

Pay for performance interventions

Quality‐based payment systems may take a variety of forms. Most often they are directed at all physician services ‐ not just at prescribing. Targets for these policies include administrative goals, waiting time, patient satisfaction and diagnostic and treatment goals. Prescribing policies include pay for performance and the potential for bonuses or penalties to encourage improvement in prescribing. On the basis of set performance standards, physicians are rewarded or punished for their prescribing (McNamara 2005). Interventions vary greatly in terms of implementation approaches, magnitude of the 'incentives' (e.g. from 2% to 25% of physician total earnings) and whether accompanying interventions are included (O'Malley 2006; Chung 2010a; Serumaga 2011). Pay for performance interventions can include prescribing targets as part of a wider set of performance objectives (e.g. in the UK general practice (Serumaga 2011) and in the Iran rural family physician programme (Takian 2011)) or can be focused on prescribing targets only (Chung 2010a).

Pharmaceutical reimbursement rate reduction

In certain countries (e.g. in East Asia), physicians can directly benefit from prescribing medicines. This is the case when the physician can purchase medicines from wholesalers, prescribe and dispense medicines for patients and then charge payers a higher price (Chu 2008). This practice has been reported in other countries as well, for example, among oncologists in the USA, where 'chemotherapy concessions' were applied (Chu 2008; Chang 2009). Oncologists could profit from prescribing medicines used to treat patients covered under Medicaid. In Taiwan, hospitals have traditionally benefited from using medicines they bought at a lower price from pharmaceutical companies and wholesalers. The tendency has been to transfer part of this benefit to the physicians who contributed to the hospitals' earnings, hence providing a direct financial incentive for overprescribing of medicines with the potential for increasing physician earnings (Chu 2008). Pharmaceutical reimbursement rate reduction policies involve reducing reimbursement rates for physicians, hence reducing the financial benefit they derive from prescribing medicines.

Why it is important to do this review

This review is part of a series of Cochrane reviews of pharmaceutical policies, undertaken to investigate the effects of different categories of pharmaceutical policies on drug and healthcare utilisation, costs and health outcomes. This review focuses on financial policies targeted at prescribers. It updates a previous Cochrane review (Sturm 2007). The conduct of this update was supported by the World Health Organization (WHO) Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research. The previous version of this Cochrane review included 13 studies of limited quality originating from three high‐income European countries (the UK, Ireland and Germany). No other studies published at that time met the inclusion criteria. Despite limitations, existing evidence suggested that appropriately designed financial incentives may have a positive influence on prescribers' behaviour.

Previously published reviews have focused on individual financial policies, such as fund‐holding and the indicative prescribing scheme in the UK and Ireland (Coulter 1995; Walley 1995; Griffin 1996; Harrison 1996; Schwartz 1996; Gosden 1997; Smith 1998; Garrison 2003) and have included broad reviews of pharmaceutical policies (Soumerai 1993; Bloor 1996; Narine 1997; Armour 2001; Ess 2003; Maynard 2003; Mossialos 2004; Lu 2008; Ostini 2009) and financial incentives (Flodgren 2012). Most of these reviews are not systematic reviews of evidence. Other identified reviews focusing on effects of various financial incentives on general medical practice only occasionally have addressed prescribing or reported drug‐related outcomes (Chaix‐Couturier 2000). Reviews investigating the effects of different remuneration systems for physicians (Bloor 1996; Gosden 1997; Chaix‐Couturier 2000; Giuffrida 2000; Gosden 2001; Maynard 2003) included only one study out of a total of 25 that reported effects on drug utilisation or related costs (excluding immunisation) for renewal of prescriptions. Pay for performance interventions are a relatively new approach, and evaluations are scarce (Giuffrida 2000; Roland 2004; Rosenthal 2004; McNamara 2005; Witter 2012). Although in some countries physicians have gained financial benefits for years from prescribing certain medicines, the impact of reimbursement rate reduction policies on prescribing has not been assessed in previous reviews of pharmaceutical policies.

In recent years, financial incentives have been used more frequently to affect prescriber behaviour, including prescribers in low‐ and middle‐income countries. More robust evaluation studies have assessed such interventions in high‐income countries. This updated review is intended to improve our understanding of interventions and their wanted (and potentially unwanted) consequences. The aims of this review are to support informed decisions about pharmaceutical policies and to guide future evaluations by presenting an up‐to‐date, comprehensive summary of what is known from well‐designed research about the effects on drug use, healthcare utilisation, health outcomes and cost (expenditures) of financial incentives targeted at prescribing.

Objectives

To determine the effects of pharmaceutical policies using financial incentives to influence prescribers' practices on drug use, healthcare utilisation, health outcomes and costs (expenditures).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), non‐randomised controlled trials (NRCTs), repeated ‐measures (RM) studies, interrupted time series (ITS) analyses and controlled before‐after (CBA) studies.

We used the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) definition of RCT, NRCT, CBA and ITS studies (EPOC 2013a). An ITS study is defined as follows: “The study must have a clearly defined time of intervention and must have at least three data points before and three data points after the intervention.” We also considered designs that include a control ITS group. Controlled ITS (CITS) designs are conceptually similar to CBA designs, but the addition of multiple time points before and after the intervention decreases the likelihood of secular change bias.

Types of participants

Healthcare consumers and providers within a large jurisdiction or system of care. Jurisdictions could be regional, national or international. Studies within organisations, such as health maintenance organisations, were included if the organisation was multi‐sited and served a wide population.

Types of interventions

Prescribing policies (financial incentives): policies that intend to affect prescribing by means of financial incentives for prescribers. Included in this category are pharmaceutical budget caps or targets, pay for performance and drug reimbursement rate reductions and other financial policies specifically targeted at prescribing or drug utilisation.

Policies in this review are defined as laws, rules, regulations and financial and administrative orders made or implemented by payers such as national or local governments, non‐government organisations, private or social insurers and insurance‐like organisations.

Types of outcome measures

To be included, a study had to use an objective measure from at least one of the following outcome categories.

Primary outcomes

Drug use (prescribed, dispensed or actually used).

Health outcomes.

Secondary outcomes

Drug costs.

Healthcare utilisation.

Other healthcare costs and policy administration costs.

We used Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) worksheets in preparing 'Summary of findings' tables to identify the list of all reported relevant outcomes (within the above four categories of outcomes) (EPOC 2013b). Three review authors (A‐HO, YV and AR) independently assessed the relative importance of each outcome for inclusion in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases with no language restrictions (Table 3).

1. Databases and websites searched for the first version of this review.

| Databases |

|

| Websites |

|

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2014, Issue 12) (including the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group Specialised Register) (searched 29/01/2015).

MEDLINE In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, MEDLINE Daily, MEDLINE and Ovid, OLDMEDLINE, 1946 to present, Ovid SP (searched 29/01/2015).

EMBASE, 1980 to 2015 Week 4, Ovid SP (searched 29/01/2015).

International Network for Rational Use of Drugs (INRUD) Bibliography (searched 29/01/2015).

National Health Service (NHS) Economic Evaluation Database (2014, Issue 4) (searched 29/01/2015).

EconLit, 1969 to present, ProQuest (searched 02/02/2015).

See Appendix 1 for all search strategies run in 2015. Search strategies for the previous version of this review (Sturm 2007) can be found in Appendix 2.

Searching other resources

We also did the following.

Conducted cited reference searches for all included studies in Science Citation Index 1975 to present and Social Sciences Citation Index 1975 to present, Institute for Scientific Information (ISI) Web of Knowledge (searched 10/02/2015).

Screened the reference lists of all relevant reports that we retrieved.

Contacted authors of relevant papers, relevant organisations and authors of discussion lists to identify additional studies, including unpublished and ongoing studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently reviewed all search results, abstracts and reference lists of relevant reports. The full text of potentially relevant reports was retrieved, and two review authors independently assessed the relevance of those studies and the limitations of included studies. One author (A‐HO, YV or HS) extracted data from the included studies in collaboration with one other review author. For all steps in the above process, we resolved disagreements by discussion, if necessary including another review author (AR or ADO).

Data extraction and management

We extracted the following information for each included study:

First author, year of publication, language of publication and study title.

Study design (randomised trial, non‐randomised trial, repeated‐measures study, interrupted time series, controlled before‐after).

Study setting (country, key features of the healthcare system, concurrent pharmaceutical policies).

Characteristics of policies and interventions.

Study duration and period (preintervention, intervention, postintervention).

Characteristics of study participants (consumers, physicians, practices, hospitals, etc.).

Main outcome measures.

Results for main outcome measures.

Sources of data and data collection approaches (routine data, databases, surveys, etc.).

Analytical methods and sample sizes.

We attempted to identify important factors that might be taken into consideration by anyone contemplating implementing any of the policy alternatives, including possible trade‐offs (of expected benefits vs harms and costs), different effects of varying policy conditions and background situations, short‐term versus long‐term effects, limitations of available evidence and other important factors that might affect the translation of available evidence into practice in specific settings. When included studies did not provide detailed information about the implemented policy and interventions, we noted further details of the intervention from excluded studies or from other published literature that gave a more detailed account of the policies and interventions.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

At least two review authors (from AR, A‐HO, YV) assessed risk of bias for included studies. We accepted risk of bias assessments of the studies included in the previous version of this review (Sturm 2007). Risk of bias assessments followed the approaches recommended by the EPOC Review Group (GRADE 2004; EPOC 2015; Ramsay 2003) (Appendix 3). Since the time of publication of the previous version of this review, two new criteria had been added to the EPOC risk of bias assessment criteria. Hence two review authors (AR, A‐HO) assessed all previously included studies, and resulting judgements were added to the tables. We recorded potential sources of bias in the included studies and expounded the implication of those biases for reported outcomes.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We noted substantial differences between policies and interventions and the settings of included studies. Even for interventions within a similar category (e.g. budget caps, pay for performance), we observed that the specifications of policies and interventions had major differences, as did measured outcomes. We discerned substantial differences in health system characteristics (e.g. financing mechanisms) that could influence the effects of policies and interventions. Therefore, we did not calculate average effects across studies and did not assess statistical heterogeneity.

Data synthesis

We followed the recommendations of EPOC regarding reanalyses of individual studies and data synthesis. For CBA studies, we reported relative effects. For continuous variables, we reported, when possible, the relative change, adjusted for baseline differences, in outcome measures. For this, we calculated absolute difference‐in‐differences, which we adjusted for the postintervention level in the control group, that is, [(the absolute postintervention difference between intervention and control groups ‐ the absolute preintervention difference between intervention and control groups)/the postintervention level in control groups].

We considered CBA studies for CITS or ITS analyses if adequate data were presented in the paper. If such analyses were conducted, we presented the results as CITS analyses. For CITS, we assessed the time series part of the studies independently from the control part, using the above described criteria for ITS. We assessed the control series part of the study using the CBA criteria above. If the control part had serious limitations, we did not include the study but classified it as an ITS; otherwise we used the control data as a control in the review.

The preferred analysis method for ITS studies was a regression analysis with time trends before and after the intervention, which adjusted for autocorrelation and periodic changes, or ARIMA analysis. We agreed that the results of outcomes should be presented as changes along two dimensions: change in level and change in slope. Change in level is the immediate effect of the policy and is measured as the difference between fitted values for the first postintervention data point (one month after the intervention) minus the predicted outcome one month after the intervention based on the preintervention slope only. We calculated the relative change in level by dividing the change in level by the predicted outcome one month after the intervention based on the preintervention slope only, and then multiplying by 100%.

Change in slope is the change in the trend from preintervention to postintervention that reflects the "long"‐term effect of the intervention. As interpretation of change in slope could be difficult, we chose to calculate and present long‐term effects and relative immediate effects in a similar way. We presented the effects after half a year by determining the difference between the fitted value for the sixth month postintervention data point (half a year after the intervention) and the predicted outcome six months after the intervention based on the preintervention slope only, and then dividing by the predicted outcome six months after the intervention based on the preintervention slope only, and multiplying by 100%. We measured the effects after one year and after two years in a similar way.

Given that policy changes are often announced some months before official implementation, a transition phase is often defined as the six months after the official announcement. If applied, all results excluded data from the transition phase. However, if studies provided only a few data points, if the data itself did not suggest a transition phase and, most important, if study authors did not state a transition phase, we did not apply it. Transition phase was used in two studies included in this review (Harris 1996; Doran 2011).

If papers with ITS design did not provide appropriate analysis or reporting of results, but presented the data points in a scannable graph or in a table, we reanalysed the data using methods described in EPOC 2013c. The following segmented time series regression model was specified: Y(t) = B0 + B1*Pre‐slope + B2*Post‐slope + B3*intervention + e(t) where Y(t) is the outcome in month t. Pre‐slope is a continuous variable indicating time from the start of the study to the last point in the preintervention phase and coded constant thereafter. Post‐slope is coded 0 up to and including the first point post intervention and is coded sequentially from 1 thereafter. Intervention is coded 0 for preintervention time points and 1 for postintervention time points. In this model, B1 estimates the slope of the preintervention data, B2 estimates the slope of the postintervention data and B3 estimates the change in level of outcome as the difference between the estimated first point post intervention and the extrapolated first point post intervention if the preintervention line was continued into the postintervention phase. The difference in slope is calculated by B2 ‐ B1. The error term e(t) was assumed to be first order autoregressive. For CITS studies, we have presented differences between relative changes in the intervention and control groups. We calculated confidence intervals (95%) for all effect measures. If possible, we calculated the effects at three, six, nine, 12 and 24 months after the intervention.

As in the previous version of the review (Sturm 2007), we did not conduct a meta‐analysis, as this was not deemed appropriate. We conducted a structured analysis and presented the findings for each policy. We calculated median effects across policies for similar outcomes when more than two ITS or CITS comparisons were available, and we reported these in the 'Summary of findings' tables. The structured analysis and 'Summary of findings' tables focus mainly on outcomes at 12 months after the intervention.

We used GRADE worksheets to assess the certainty of evidence across studies for each selected outcome. We populated the worksheet for each selected outcome to document study designs of included primary studies; risks of bias of the primary studies; inconsistency, indirectness and imprecision in the findings; and other factors that might influence risks of bias across the included studies for each outcome.We assessed the certainty of evidence for each outcome as high, moderate, low or very low in keeping with GRADE recommendations (EPOC 2013d).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We prepared tables for each subcategory of policy interventions and included the following information: study identification, characteristics of the intervention, results of drug use, healthcare utilisation, health outcomes and costs. These tables form the basis for the structured synthesis that we conducted. In Table 4, we described potential mechanisms through which the policies were intended to affect drug use and costs, and we postulated mechanisms for other effects, both intended and unintended. In addition, in Table 5 we briefly listed and described other important policy options for which we included no evaluations.

2. Description of financial incentive policies of the included studies.

| Country | Policy/Time period | Motivation | Setting of budget | Physician incentives | Physician disincentives | Theoretical effects |

| Taiwan | Drug reimbursement rate reduction, starting in 2000 | Reducing prescription costs | Physicians earn a share of the revenue that hospitals gain from selling medicines | Reducing reimbursement rate reduces physicians' tendency to overprescribe | Fincianal incentives from drug sales affect physician prescribing. Removing this incentive will help to rationalise physician prescribing | |

| Taiwan | National Health Insurance Drug Budget Programme, starting in 2002 | Reducing prescription costs | Global budget based on an individual expenditure cap | Maximum expenditure cap | ||

| UK | Pay for performance (quality and outcome framework), starting in 2004 | improving quality of care | NHS committed 1.8 GBP for funding the programme | Up to 25% increase in physician income (maximum of 31,000 GBP) | Direct financial incentives may result in improved quality of care, including prescribing | |

| Sweden | Fixed pharmaceutical budget, 2000 to 2003 | Controlling prescription drug costs | Previous year budget and demographic characteristics of patients | Remaining pharmaceutical budget was given to the health centre and can be used as bonus payment | Health centre had to repay any extra pharmaceutical expenditures | Making the health centres 'residual claimants' (i.e. responsible for deficits or surpluses) will directly affect the physicians prescribing. This may happen via reducing the number of prescriptions, reducing DDD per prescription or selecting cheaper alternative pharmaceuticals |

| Netherlands | Behaviour‐independent financial incentive, 2000 to 2002 | Controlling prescription drug costs | On‐off bonus payment by the insurance company (paid before‐hand, irrespective of physician performance) | The decision to follow the regional formulary was made democratically in the presence of physician representatives and opinion leaders | Ownership of the decision via participation in development of the formulary and the decision to adopt the formulary via the insurance organisation is likely to improve physician performance towards the target behaviour | |

| Germany | Collective drug budget "spending caps" (Health Care Reform Act), 1993 to 2002 (formally abolished in 2001) | Controlling prescription drug costs | Based on previous regional spending. From 1998: regional net budget = gross budget minus co‐payments and rebates from industry nationally set in 1993, then regionally Negotiated between physician associations and statutory health insurances | None (savings will not be available to physicians) | Regional physician associations are responsible for overspending (maximum 5% of total budget). Can decline to pay for excess spending and can request it from individual practice | Reduction in drugs with disputed effect, savings can facilitate use of more expensive drugs, improve quality of prescribing or increase referrals to save (drug budget is independent of other care) |

| Ireland | IDTSS (Indicative Drug Target Savings Scheme), starting in 1993 | Controlling prescription drug costs | Individual practice budget based on previous spending and national average Negotiated by local medical advisor and practice | Savings were divided between GP and health authority | None | Decrease in prescribed drug volume and cost per item; improvement in quality of prescribing |

| UK | Fund‐holding in Great Britain and Scotland: April/1991 to 1997 (announced in 1990) in Wales and Northern Ireland 1993 to 1997 | Controlling prescription drug costs | Based on previous spending of practice adjusted for patient mix and spending of comparators Negotiated by local health authority and practice | Savings can be invested by each fund‐holder to improve services in other budgets, or in the year following the year's drug budget | Responsible for overspending up to a limit of 5000£. Overspending can be covered by other budgets | Decrease in prescribed drug volume and cost per item; improvement in quality of prescribing. Referrals are postponed, as these are also part of a budget |

3. Description of other identified financial incentive policies that did not meet the inclusion criteria.

| Country | Policy | Motivation | Setting of budget | Incentives | Disincentives | Theoretical effects |

| New Zealand | Independent practice associations (IPAs): umbrella organisation of general practitioners (GPs), specialists and other healthcare (HC) providers with different budgets for provided care (1993) | Budgets: to improve quality of care (IPAs: increase power of GPs towards health reforms) | IPA can choose to take a budget for pharmaceutical expenditures. Historical expenditures (changes from fee‐for‐service to Integrated capitation based budgets) Regional health authority (or other payers) and IPA |

Savings can be kept by associations to improve quality of care. Savings can be shifted between budgets | IPA is responsible for overspends, but physicians have refused to take financial responsibility | GPs within association compete for patients |

| USA | Managed care withholdings | Capitation minus, e.g. 20% Primary care group and HMO |

Bonus if practice balance is positive | Only partial withholding is paid in cases of deficit | Keep within the budget | |

| USA | Pharmaceutical capitation | To have health plans control the growth of their own spending by controlling capitation levels | Target drug spending amount for a set of patients (per member per month) based on a base rate, adjusted for case mix; providers negotiate with health pan | Later: Savings will be shared by prescribers | A percentage of the difference between target and actual spending (around 70%) has to be paid by the physician | Prescribe fewer and less expensive drugs, irrespective of the capitation rate |

| UK | Unified budgets for new primary care groups, starting in 1999 | To ensure that accountability of GPs will help solve problems | Budget for hospital care, community health services, prescribing, infrastructure costs; funds allocated by health authority. Compulsory for all GPs | For staff premises and computer costs. GP salary not involved | Increased monitoring needed. As GP budget grows slower than overall budget, incentive to limit spending | |

| Sweden | Regionalisation: responsibility for drug expenditure moved from federal to regional level, starting in 1998 | To increase cost awareness of county councils | Government and county council | Generate savings | 2002 to 2004: Exceeding costs are covered by the government, which compensates county council for up to 75% of overspent costs (ca 9% of budget) | Development of local initiatives promoting economical prescribing (generic prescribing, drug lists. etc.) |

| Italy | Benchmarking 1980; virtual targets ("budget agreements") 1992; guidelines | To contain costs, decrease growth of drug expenditures | Local agreement (local health enterprises responsible for drug budget); GP association and local health enterprises | Regional savings will be distributed in terms of money or other rewards | None applied | Drugs versus overall |

| Spain | Regional target budgets for primary care centres and hospitals, starting in 2000 | To improve efficiency of care | Regional | About 2% of salary is dependent on prescribing targets (Antononaz 2002) | None (national drug budgets are always covered by industry; physicians are paid by salary) | No abuse because of constant monitoring |

| Switzerland | Budget cap plus gate‐keeping | To slow growth of healthcare expenditures | Per capita expenditure caps | Physician manager responsible for keeping the budget within limits by supervising physicians | The insurer is to retain financial responsibility, but penalties would be applied for those exceeding budgets | Efficient provision of care |

| USA/Michigan | Pay for performance 2000 to 2003 | To reduce prescription drug costs | Regional | Small financial incentive of $250 to $500 every 6 months | None | Financial incentive improves targeted behaviours |

| USA/One locality | Physician‐specific pay for performance on top of fee‐for‐service payments, 2005 to 2007 | To improve quality of care | Local | Small financial incentive, maximum of $5000 per year (about 2% of annual salary) | None | Physician designed pay for performance is more likely to improve behaviour than P4Ps designed without the input of physicians |

| UK | Indicative prescribing scheme, 1991 to 1997 | To control prescription drug costs | Based on previous spending practice, negotiated by local medical advisors and statutory health insurances | Savings to be used within health authority and divided by all GPs | None | Decrease in prescribed drug volume and cost per item. Improvement in quality of prescribing |

| USA | Medicare Prescription Drug Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003 | To apply reimbursement rate reduction policy | National | Physicians earn a share of the revenue that hospitals gain by selling medicines | Reducing reimbursement rate reduces physicians' tendency to overprescribe | Fincianal incentives from drug sales affect physician prescribing. Removing this incentive will help to rationalise physician prescribing |

| Literature: New Zealand (Malcolm 1999; Malcolm 2001); USA (Weiner 1990; Jacobson 2006; O'Malley 2006; Rosenthal 2006; Rowe 2006; Trude 2006; Chang 2009; Chung 2010a; Doshi 2010; Elliott 2010; ); UK (Bateman 1996; Whynes 1997b; Ashworth 2004; Klein 2004); Sweden (Calltorp 1996; Calltorp 1999; Lundkvist 2002; Ohlsson 2007; Andersson 2009); Italy (Fattore 1998; Atella 2000; Mapelli 2003); Spain (Lopez Bastida 2000; Antonanzas 2003); Switzerland (Etter 1998) | ||||||

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

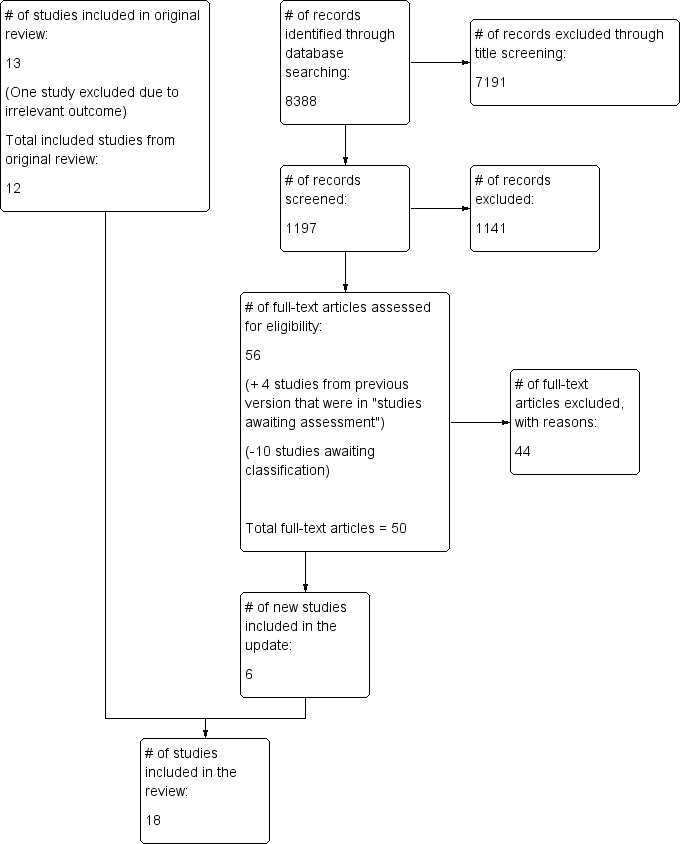

The search in 2015 yielded 8388 records. We excluded 7191 records upon review of the titles. We screened the remaining 1197 records by reviewing abstracts, assessed 56 full‐text papers and included six studies. Thirteen studies were previously included (Sturm 2007), one of which was excluded for this update because outcomes were irrelevant. Studies included in the review now total 18. See Figure 1 for additional details.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

In total, we included 18 studies in this review, consisting of studies on pharmaceutical budget, pay for performance and drug reimbursement rate reduction policies. Thirteen studies (16 papers) had been included in the previous version of the review (Sturm 2005), of which one study was excluded from the current review. We excluded the Kammerling 1996 study, as it did not include specific prescribing outcome measures, and because it was difficult to argue that changes in reported outcomes were the result of financial incentives for prescribing.

Nine included studies assessed the effects of British fund‐holding (Burr 1992; Bradlow 1993; Wilson 1995; Harris 1996; Baines 1997c; Corney 1997; Rafferty 1997; Whynes 1997; Wilson 1999), one study analysed the effects of the indicative prescribing scheme in Ireland (Walley 2000) and two studies reported on drug expenditure budgets in Germany (Guether 1995; Schöffski 1997). Three studies were reported in more than one paper (Bradlow 1993; Wilson 1995; Schöffski 1997). The update resulted in the inclusion of six additional studies. Three studies assessed pay for performance and target payments in the UK and the Netherlands (Martens 2007; Doran 2011; Serumaga 2011), two studies assessed different forms of pharmaceutical budgets in Sweden and Taiwan (Granlund 2006; Chou 2008) and one study assessed the effects of changing providers' benefit margin for dispensing of medicines in Taiwan (Chu 2008). None of the included studies were RCTs, CCTs or RM studies. We included three CITS analyses (Wilson 1995; Harris 1996; Rafferty 1997), six ITS studies (Guether 1995; Schöffski 1997; Walley 2000; Chou 2008; Doran 2011; Serumaga 2011) and nine CBA studies (Burr 1992; Bradlow 1993; Baines 1997c; Corney 1997; Whynes 1997; Wilson 1999; Granlund 2006; Martens 2007; Chu 2008; ). See Characteristics of included studies table for further details.

Excluded studies

The Characteristics of excluded studies table provides reasons for exclusion of studies for which it is plausible to expect that a reader would question why the study was not included. The main reason for excluding these studies was the study design (37 studies), for example, lack of a control group (in a before‐after study). Other reasons for exclusion include an intervention that did not provide financial incentives for prescribers (13 studies), confounding (five studies), lack of reporting of a relevant outcome (four studies), lack of reporting of a primary study (three studies) and insufficient data (two studies).

Risk of bias in included studies

See Characteristics of included studies, Table 6, Table 7, Appendix 3, Appendix 4 and Appendix 5.

4. Risk of bias in CBA studies.

| Bias/Study |

Bradlow 1993 |

Burr 1992 |

Whynes 1997 |

Wilson 1999 |

Baines 1997 |

Corney 1997 |

Martens 2007 |

Granlund 2006 |

Chu 2008 |

| Was the allocation sequence adequately generated? | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Was the allocation adequately concealed? | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Were baseline outcome measurements similar? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Were baseline characteristics similar? | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed? | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes |

| Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

| Was the study adequately protected against contamination? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was the study free of selective outcome reporting? | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was the study free of other risks of bias? | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No |

5. Risk of bias in interrupted time series (ITS) studies.

| Bias/Study |

Walley 2000 |

Gouether 1995 |

Schoffski 1997 |

Harris 1996 |

Wilson 1995 |

Raferty 1997 |

Doran 2011 |

Serumaga 2011 |

Chou 2008 |

| Was the intervention independent of other changes? | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

| Was the shape of the intervention effect prespecified? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | No |

| Was the intervention unlikely to affect data collection? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

| Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed? | Unclear | Unclear | No | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | No | Unclear | No |

| Was the study free of selective outcome reporting? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes |

| Was the study free of other risks of bias? | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | No | No | No | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

We assessed all CBA studies as having serious limitations due to marked differences between experimental and control groups (selection bias). More important, it must be noted that for CBA studies that assessed the British fund‐holding policy, intervention group members had voluntarily joined the policy. We assessed three studies (Wilson 1995; Harris 1996; Rafferty 1997) as having some limitations, as they were CBA studies that had been reanalysed as CITS studies.

One ITS study assessed a pharmaceutical budget policy in Ireland (Walley 2000). We rated the quality as having some limitations. We included two ITS studies that evaluated German drug budgets. Drug volume was assessed by one (Guether 1995), and referrals by two (Guether 1995; Schöffski 1997). These findings had some limitations, as data were presented quarterly rather than monthly, time series included too few data points (Guether 1995) or limitations were the result of incomplete data (Schöffski 1997). In Guether 1995, data were reported with a "quasi control group" (prescriptions for privately insured patients not subject to budgets as opposed to socially insured), but investigators found the groups to be too different to be used as reliable comparators; therefore only ITS data of the intervention group were used in the analysis. Two ITS studies assessed the pay for performance policy in the UK (Doran 2011; Serumaga 2011). We determined that Doran 2011 had some limitations, as it provided few data points for analysis. Another ITS study (Chou 2008) assessed a pharmaceutical budget policy in Taiwan and provided quarterly data points; we assessed this study as having some limitations.

Most of the included studies did not provide adequate information about simultaneous confounding interventions that might have been introduced during the study period, or about important economic or other changes that might have affected the findings (e.g. see Healey 1994 as an example of how self selection among fund‐holding practices in the UK might have affected observed outcomes of the policy).

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings: drug budget policies.

|

People: Physicians/General practitioners/Patients Settings (interventions): Germany (collective drug budget "spending caps"), Ireland (Indicative Drug Target Savings Scheme), Sweden (fixed pharmaceutical budget), Taiwan (National Health Insurance Drug Budget Programme), UK (fund‐holding) Designs: ITS and CITS Comparison: no prescribing policies | |||||

|

Outcomes 12‐month follow‐up |

Impacts ‐ relative changes, Median (range)a |

Number of studies (comparisons) |

Settings |

Certainty of the evidenceb (GRADE)c |

Comments |

| Drug use (item per patient or prescription) | ‐2.8% (‐28.9 to 1.5) | 6 (14) | Germany, Ireland, Taiwand, UK | Low | It is possible that the intervention results in modest improvements (reductions in items per patient). Findings were relatively consistent in different countries despite differences between interventions |

| Drug use (generic percentage) | 15% (‐43.7 to 190.5) | 2 (6) | UK | Very low | |

| Costs per item | ‐25.6% (‐49.2 to 0.6) |

3 (6) | Ireland, UK | Very low | |

| Costs per patient or prescription | ‐2.5% (‐79.7 to 66.8) |

4 (11) | Taiwand, UK | Very low | |

| Total costs | ‐38.9% (‐69.6 to ‐1.8) |

2 (4) | Ireland, UK | Very low | Although the findings from 2 countries are consistent, both studies suffer from too few data points |

| Healthcare utilisation (referral to outpatient specialists) | ‐1.1% (‐15.4 to 13.2) |

2 (2) | Germany | Very low | |

| Health outcomes | ‐ | 0 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

|

aNote: Presented results are medians (ranges) of results of individual studies; no meta‐analyses were performed. bAll included ITS studies suffer from too few data points. | |||||

|

cGRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High: It is very likely that the effect will be close to what was found in the research. Moderate: It is likely that the effect will be close to what was found in the research, but it may be substantially different. Low: It is likely that the effect will be substantially different from what was found in the research, but the research provides an indication of what might be expected. Very low: The anticipated effect is very uncertain, and the research does not provide a reliable indication of what might be expected. | |||||

| dFrom Taiwan, only 1 estimate was used in calculating the median, as 2 available estimates were based on 1 intervention assessed in the study. | |||||

CITS: controlled interrupted time series; ITS: interrupted time series.

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings: pay for performance policies.

|

People: Physicians/General practitioners/Patients Settings (interventions): UK (pay for performance) Designs: ITS and CITS Comparison: no prescribing policies | |||||

|

Outcomes 12‐month follow‐up |

Impacts ‐ relative changes |

Number of studies (comparisons) |

Setting |

Certainty of the evidence (GRADE)a |

Comments |

| Drug use | Range 2.5 to 2.6 | 1 (2) | UK | Very low | Some negative impact was reported on non‐incentivised non‐prescribing outcomes |

| Costs | ‐ | 0 | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Healthcare utilisation | ‐ | 0 | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Health outcomes | Mean ‐1.49% (95% CI ‐6.32 to 3.34) | 1 (1) | UK | Very low | 1 comparison (percentage of patients with controlled blood pressure) from 1 setting |

|

aGRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High: It is very likely that the effect will be close to what was found in the research. Moderate: It is likely that the effect will be close to what was found in the research, but it may be substantially different. Low: It is likely that the effect will be substantially different from what was found in the research, but the research provides an indication of what might be expected. Very low: The anticipated effect is very uncertain, and the research does not provide a reliable indication of what might be expected. | |||||

We described in Table 4 the settings and policies of the included studies. Here we described in further detail the pharmaceutical policies assessed in the included studies together with the main findings.

Characteristics of pharmaceutical budget policies

Although budgetary policies were applied in at least 10 countries (see Table 5; see also Garrison 2003 and Mossalios 2005 for further examples in Europe), we could include evaluation studies from only five countries (Germany, Ireland, Sweden, Taiwan and the UK).

UK fundholding

Fund‐holding for general practitioners (GPs) in the UK was introduced with the first wave of voluntary practices in the early 1990s. Each year, practices with at least 11,000 registered patients could join the fund‐holding scheme in "waves", until in 1997, healthcare trusts were introduced. With each wave, regulations on requisites for joining practices were relaxed. The aim of fund‐holding was to increase efficiency of care by giving GPs financial control over some of their provided services (Weiner 1990; Glynn 1992; Wilson 1995; Audit Comm. 1996). Besides costs of prescribed drugs, separate budgets covered practice staff and a range of secondary care services such as specialist services and elective surgical services, with the drug budget offering the greatest savings potential (Harris 1996). Overspending in one budget had to be covered by funds from another budget, and savings could be used in other areas of patient care (Coulter 1993). Budgets were set on the basis of previous expenditures and at the discretion of the local health authority medical advisor. Therefore budgets varied substantially from practice to practice (Day 1991). Concurrently all practices, fund‐holders and non‐fund‐holders alike were exposed to practice level feedback on their own performance in comparison with others (benchmarking), as well as to regular visits of independent pharmaceutical advisors from the local health authority. Initiatives to reduce costs of individual prescriptions such as use of limited lists and promotion of generics were launched (Baines 1997c).

Irish indicative drug budget

In 1993 in Ireland, a comparable scheme called the Indicative Drug Targeting Savings Scheme (IDTSS) was introduced (Walley 2000). Individual indicative or hypothetical budgets of GPs covered prescribing and associated costs and were calculated on the basis of previous spending and the national average. Savings were split between the GP and the local health authority for use in the development of services. No penalties were imposed for overspending.

German drug budget

Collective budgets for drug expenditures for physicians in private practice in Germany were in use from 1993 to 2002 with the stated goal to maximise effectiveness by using less costly and more effective drugs. It was expected that although generic use would increase, use of drugs with disputed effects would decrease (Gross 1994; Busse 1996; Schwartz 1996; Schwermann 2003; Schreyögg 2005). Although spending caps were regionally negotiated or nationally set each year and made all physicians in private practice in one region collectively liable, target volumes for each individual practice were only theoretically established. From 2002, budgets were abolished and were replaced by practice level target volumes (negotiated between the physician association and insurers). Parallel to initiation of budgets, reference pricing, changing levels of co‐payment and price cuts for pharmaceuticals were introduced.

Taiwan pharmaceutical budget

Before 2002, Taiwan's National Health Insurance paid providers on a fee‐for‐service basis, and patients were free to choose among providers. Concerns surrounded increases in costs and subsequent increases in insurance premiums. The global budget was implemented by hospitals in 2002, and it involved an expenditure cap. The cap was determined before each fiscal year. As a result, if providers delivered more services, their profit would be reduced. The global budget was later expanded to include hospital‐specific targets such as prescription caps (Chou 2008).

Sweden pharmaceutical budget

Since 1998, the county councils in Sweden have been responsible for pharmaceutical costs not covered by patient co‐payments. Hence they have been investigating routes to contain pharmaceutical costs. The approach involved a local county council's policy of imposing a fixed pharmaceutical budget on the health centres, which were expected to cover any pharmaceutical budget deficits and were allowed to keep any surplus generated each fiscal year (Granlund 2006).

Effects of pharmaceutical budget policies

Drug use

Twelve studies (six ITS or CITS studies and six CBA studies) assessed the effects of pharmaceutical budget interventions on drug use in five countries (Table 8).

6. Effect of drug budgetary policies on drug use.

| Intervention | Outcome | Study ID | Setting | Type of Study | |||||

| UK fund ‐holding | Items per patient | Adjusted absolute change | Adjusted relative change 3 months | Adjusted relative change 6 months | Adjusted relative change 12 months | Adjusted relative change 24 months | |||

| Burr 1992 | Wave 1 | CBA | 18 | ‐ | ‐ | 0.8 | ‐ | ||

| Bradlow 1993 | Wave 1 | CBA | 40 | ‐ | ‐ | 1.8 | ‐ | ||

| Bradlow 1993 | Wave 1 | CBA | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 3.6**/**** | ||

| Wilson 1999 | Wave 3/4 | CBA | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 39.2*** | ||

| Whynes 1997 | Wave 4 | CBA | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐1.2 | ‐ | ||

| Items per patient | Absolute level effect (95% CI) | Relative change 3 months (95% CI) | Relative change 6 months (95% CI) | Relative change 12 months (95% CI) | Relative change 24 months (95% CI) | ||||

| Rafferty 1997 | Wave 1 | CITS | ‐63.6 (‐249.3 to 122.1) | ‐2.5 (‐9.8 to 4.9) | ‐1 (‐8.8 to 6.8) | ‐2.8 (‐11.5 to 5.9) | 0.2 (‐10.3 to 10.7) | ||

| Harris 1996 | Wave 1 | CITS | 0.4 (‐1.1 to 1.8) | 0.4 (‐1.2 to 2) | 0.7 (‐1.3 to 2.7) | 1.4 (‐1.5 to 4.2) | 2.6 (‐2.1 to 7.2) | ||

| Wilson 1995 | Wave 1 | CITS | 1.4 (‐6.6 to 9.4) | 1.9 (‐9.3 to 13.1) | ‐4.1 (4.3 to ‐4) | ‐10.2 (‐10.4 to ‐10) | ‐ | ||

| Rafferty 1997 | Wave 2 | CITS | ‐43.6 (‐257 to 169.8) | ‐1.6 (‐9.2 to 6) | ‐2.4 (‐10.3 to 5.5) | ‐3.6 (‐12.1 to 4.8) | ‐4.2 (‐13.7 to 5.4) | ||

| Rafferty 1997 | Wave 3 | CITS | ‐44.3 (‐280.1 to 191.4) | ‐1.4 (‐9.9 to 7) | 1.5 (‐7.2 to 10.1) | 1.5 (‐7.5 to 10.5) | ‐ | ||

| Wilson 1995 | Wave 2 | CITS | 2.7 (‐9.5 to 14.9) | 7.1 (‐25.1 to 39.2) | ‐15.8 (‐16.1 to ‐15.5) | ‐14.5 (‐15.2 to ‐13.9) | ‐ | ||

| Wilson 1995 | Wave 3 | CITS | 4.8 (‐4.8 to 14.4) | 16.8 (‐17.1 to 50.8) | ‐21.3 (‐21.6 to ‐20.9) | ‐28.9 (‐29.4 to ‐28.3) | ‐ | ||

| Harris 1996 | Wave 2 | CITS | ‐0.5 (‐1.3 to 0.3) | ‐0.5 (‐1.3 to 0.3) | ‐0.4 (‐1.3 to 0.5) | ‐0.3 (‐1.4 to 0.8) | ‐0.1 (‐1.7 to 1.5) | ||

| Harris 1996 | Wave 3 | CITS | 0.0 (‐0.7 to 0.7) | 0.0 (‐0.8 to 0.8) | 0.0 (‐0.8 to 0.9) | 0.2 (‐0.7 to 1.2) | 0.4 (‐0.7 to 1.6) | ||

| Harris 1996 | Wave 4 | CITS | 0.3 (‐0.4 to 1) | 0.3 (‐0.4 to 1.1) | 0.1 (‐0.6 to 0.9) | ‐0.4 (‐1.2 to 0.5) | ‐ | ||

| Harris 1996 | Wave 5 | CITS | ‐0.2 (‐1 to 0.5) | ‐0.2 (‐1 to 0.5) | ‐0.2 (‐1 to 0.6) | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Generic percentage | Adjusted absolute change | Adjusted relative change 3 months | Adjusted relative change 6 months | Adjusted relative change 12 months | Adjusted relative change 24 months | ||||

| Bradlow 1993 | Wave 1 | CBA | 4.1 | ‐ | ‐ | 8.8 | ‐ | ||

| Bradlow 1993 | Wave 1 | CBA | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 17.2**/**** | ||

| Baines 1997 | Waves 1 to 3, Lincolns | CBA | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 10.7** | ||

| Baines 1997 | Waves 1 to 3, Devon | CBA | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 9.5** | ||

| Whynes 1997 | Wave 4 | CBA | 3.5 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Wilson 1999* | Wave 3/4 | CBA | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 4*** | ||

| Generic percentage | Absolute level effect (95% CI) | Relative change 3 months (95% CI) | Relative change 6 months (95% CI) | Relative change 12 months (95% CI) | Relative change 24 months (95% CI) | ||||

| Rafferty 1997 | Wave 1 | CITS | 2.8 (1.5 to 4.1) | 10.8 (5.6 to 16) | 12.7 (7.1 to 18.2) | 15.8 (9.4 to 22.2) | 23 (15 to 31) | ||

| Wilson 1995 | Wave 1 | CITS | 1.7 (0.8 to 2.7) | 345.7 (151.8 to 539.6) | 342.7 (341.1 to 344.4) | 190.5 (189 to 192) | ‐ | ||

| Rafferty 1997 | Wave 2 | CITS | 1.3 (‐0.2 to 2.9) | 5.1 (‐0.9 to 11.1) | 5.9 (‐0.4 to 12.2) | 8.5 (1.6 to 15.5) | 13.6 (5.4 to 21.7) | ||

| Rafferty 1997 | Wave 3 | CITS | 0.5 (‐1 to 1.9) | 1.8 (‐3.9 to 7.4) | 5.7 (‐0.1 to 11.5) | 14.2 (8.1 to 20.4) | ‐ | ||

| Wilson 1995 | Wave 2 | CITS | 1.0 (‐0.1 to 2.1) | 45.4 (‐2.4 to 93.2) | 66.5 (66.1 to 66.8) | 68.1 (67.6 to 68.7) | ‐ | ||

| Wilson 1995 | Wave 3 | CITS | 1.9 (0.8 to 3) | 35.5 (15.1 to 55.9) | ‐12.2 (‐12.4 to ‐12.1) | ‐43.7 (‐43.5 to ‐44.0) | ‐ | ||

| All antiulcer drugs (DDD) | Adjusted absolute change | Adjusted relative change 3 months | Adjusted relative change 6 months | Adjusted relative change 12 months | Adjusted relative change 24 months | ||||

| Wilson 1999 | Wave 3/4 | CBA | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐6.7*** | ||

| Percentage PPI of all antiulcer drugs (DDD) | Adjusted absolute change | Adjusted relative change 3 months | Adjusted relative change 6 months | Adjusted relative change 12 months | Adjusted relative change 24 months | ||||

| Wilson 1999 | Wave 3/4 | CBA | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐7.9*** | ||

| All antidepressant drugs (DDD) | Adjusted absolute change | Adjusted relative change 3 months | Adjusted relative change 6 months | Adjusted relative change 12 months | Adjusted relative change 24 months | ||||

| Wilson 1999 | Wave 3/4 | CBA | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐7.9*** | ||

| Percentage SSRIs of all antidepressant drugs (DDD) | Adjusted absolute change | Adjusted relative change 3 months | Adjusted relative change 6 months | Adjusted relative change 12 months | Adjusted relative change 24 months | ||||

| Wilson 1999 | Wave 3/4 | CBA | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐0.8*** | ||

| Ireland indicative drug budgets | Items per patient | Absolute level effect (95% CI) | Relative change 3 months (95% CI) | Relative change 6 months (95% CI) | Relative change 12 months (95% CI) | Relative change 24 months (95% CI) | |||

| Walley 2000 | IDTSS | ITS | ‐0.8 (‐1.4 to ‐0.2) |

‐ | ‐ | ‐8.2 (‐14.4 to ‐2.0) |

‐10.1 (‐17.5 to ‐2.7) |

||

| German drug budget | Items per patient | Absolute level effect (95% CI) | Relative change 3 months (95% CI) | Relative change 6 months (95% CI) | Relative change 12 months (95% CI) | Relative change 24 months (95% CI) | |||

| Guether 1995 | Social insurance | ITS | ‐34,552 (‐99,896 to 30,791) | ‐11.2 (‐32.3 to 10.0) | ‐12.1 (‐37.8 to 13.7) | ‐13.4 (‐48.9 to 22.1) | ‐ | ||

| Taiwan National Health Insurance (NHI) Drug Budget Programme | Items per prescription | Absolute level effect (95% CI) | Relative change 3 months (95% CI) | Relative change 6 months (95% CI) | Relative change 12 months (95% CI) | Relative change 24 months (95% CI) | |||

| Chou 2008 (for hypertension) |

NHI | ITS | 0.000 (‐0.001 to 0.014) | ‐0.01 (‐0.05 to 0.03)º | ‐ 0.01 (‐0.06 to 0.03) º | ‐0.01 (‐0.06 to 0.04) | ‐0.01 (‐0.08 to 0.06) | ||

| Chou 2008 (for diabetes) | NHI | ITS | ‐0.01 (‐0.02 to ‐0.005) | ‐0.02 (‐0.04 to 0.04) º º | ‐0.01 (‐0.05 to 0.03) º º | ‐0.02 (‐0.05 to 0.03) | ‐0.06 (‐0.13 to 0.006) | ||

| Sweden fixed budgets for pharmaceutical expenditures | Prescription per patient | Adjusted absolute change | Adjusted relative change 3 months | Adjusted relative change 6 months | Adjusted relative change 12 months | Adjusted relative change 24 months | |||

| Granlund 2006 | Sweden, Burtrask | CBA | ‐0.03 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐0.05 º º º | ||

| Granlund 2006 | Sweden, Morobacke | CBA | 0.39 | ‐ | ‐ | 0.70 | ‐ | ||

| DDDs per prescription | Adjusted absolute change | Adjusted relative change 3 months | Adjusted relative change 6 months | Adjusted relative change 12 months | Adjusted relative change 24 months | ||||

| Granlund 2006 | Sweden, Burtrask | CBA | ‐2.35 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐0.055 º º º | ||

| Granlund 2006 | Sweden, Morobacke | CBA | 2.12 | ‐ | ‐ | 0.05 | ‐ | ||

| *Median. **3‐year f/u. ***Combined wave 4: 1‐year f/u; wave 3: 2‐year f/u. ****Data from Stewart‐Brown 1995. º Data were available for 4 months after the intervention. º º Data were available for 8 months after the intervention. º º º Data were available for 20 months after the intervention. CBA: controlled before‐after; CITS: controlled interrupted time series; DDD: defined daily doses; IDTSS: Indicative Drug Target Savings Scheme; ITS: interrupted time series. | |||||||||

Drug use per patient or prescription

Seven studies reported effects of different waves of British fund‐holding in the UK (Burr 1992; Bradlow 1993; Wilson 1995; Harris 1996; Rafferty 1997; Whynes 1997; Wilson 1999). In CITS studies (median effect at 12 months ‐1.5%, range ‐28.9% to +1.5%) and in CBA studies (median effect at 12 months 0.8%, range ‐1.2% to +1.8%), a relative reduction in prescribed drugs among fund‐holders compared with controls was observed. The effect seemed to decrease with later waves of fund‐holding. One ITS study of the Irish Indicative Drug Target Savings Scheme observed a relative reduction in the number of prescribed items over follow‐up periods of one year (‐8.2%) and two years (‐10.1%) (Walley 2000). Another ITS study of the German drug budget (Guether 1995) observed that the overall number of prescriptions decreased from ‐11.2% at three months to ‐13.4% at 12 months. A further ITS study assessed the effects of the Taiwan National Health Insurance drug budget programme (Chou 2008), and found negligible reductions in drug use. Similarly, a CBA study of Sweden fixed budgets for pharmaceutical expenditures observed small reductions or increases in overall prescriptions (Granlund 2006).

Findings of six ITS and CITS studies suggest that pharmaceutical budgets might result in a modest reduction in overall drug use (median relative change ‐2.8%), although the effect is uncertain, given the limitations of the included studies (Table 1).

Generic percentage

Six studies reported on the effects of UK fund‐holding on generic prescribing. The effect on generic drug use was most consistent across waves and follow‐up periods: All results reported in the studies almost uniformly showed a greater increase in use of generic drugs among fund‐holders. CITS studies suggest a median of +15.0% (range ‐43.7% to 190.5%) at 12 months and +18.3% (13.6% to 23.0%) at 24 months (Rafferty 1997; Wilson 1995). Effects of CBA studies ranged between 4.0% and 17.2% (median 10.1%) at 24 months (Bradlow 1993; Baines 1997c; Wilson 1999).

Drug cost

Twelve studies (five ITS or CITS studies and seven CBA studies) assessed the effects of pharmaceutical budget interventions on drug expenditures in four countries (Table 9).

7. Effect of drug budgetary policies on drug expenditures.

| Intervention | Outcome | Study ID | Setting | Type of study | |||||

| UK fund‐holding | Costs per item | Adjusted absolute change | Adjusted relative change 3 months | Adjusted relative change 6 months | Adjusted relative change 12 months | Adjusted relative change 24 months | |||

| Bradlow 1993 | Wave 1 | CBA | ‐0.5 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐6.3 | |||

| Bradlow 1993 | Wave 1 | CBA | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐5.2*/*** | ||

| Rafferty 1997 | Wave 3 | CBA | ‐0.5 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐5.3 | n.a. | ||

| Wilson 1999 | Wave 3/4 | CBA | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐2.8** | ||

| Costs per item | Absolute level effect (95% CI) | Relative change 3 months (95% CI) | Relative change 6 months (95% CI) | Relative change 12 months (95% CI) | Relative change 24 months (95% CI) | ||||

| Rafferty 1997 | Wave 1 | CITS | ‐0.4 (‐0.8 to 0) | ‐4.9 (‐10.1 to 0.4) | ‐5.8 (‐11,3 to ‐0,3) | ‐7 (‐13 to ‐1) | ‐9.2 (‐16.1 to ‐2.3) | ||

| Wilson 1995 | Wave 1 | CITS | ‐0.2 (‐0.3 to ‐0.1) | ‐31.4 (‐50 to ‐13.1) | ‐41.6 (‐41.8 to ‐41.4) | ‐47.8 (‐48.2 to ‐47.5) | ‐ | ||

| Rafferty 1997 | Wave 2 | CITS | ‐0.3 (‐0.8 to 0.2) | ‐3.5 (‐9.2 to 2.2) | ‐4.2 (‐10.1 to 1.6) | ‐6.2 (‐12.4 to 0) | ‐9.8 (‐16.7 to ‐3) | ||

| Wilson 1995 | Wave 2 | CITS | ‐0.2 (‐0.4 to ‐0) | ‐36.9 (‐71.1 to ‐2.7) | ‐45.1 (‐45.5 to ‐44.7) | ‐49.2 (‐49.9 to 48.5) | ‐ | ||

| Wilson 1995 | Wave 3 | CITS | ‐0.3 (‐0.5 to ‐0.1) | ‐99.6 (‐157.4 to ‐41.8) | ‐85.3 (‐86 to ‐84.6) | ‐44.3 (‐45.7 to 42.9) | ‐ | ||

| Costs per item (PPIs) | Adjusted relative change 24 months | Adjusted absolute change | Adjusted relative change 3 months | Adjusted relative change 6 months | Adjusted relative change 12 months | Adjusted relative change 24 months | |||

| Wilson 1999 | Wave 3/4 | CBA | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐1** | ||

| Costs per item (SSRIs) | Adjusted relative change 24 months | Adjusted absolute change | Adjusted relative change 3 months | Adjusted relative change 6 months | Adjusted relative change 12 months | Adjusted relative change 24 months | |||

| Wilson 1999 | Wave 3/4 | CBA | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐1.9 | ‐2.7** | ||

| Costs per patient | Adjusted relative change 24 months | Adjusted absolute change | Adjusted relative change 3 months | Adjusted relative change 6 months | Adjusted relative change 12 months | Adjusted relative change 24 months | |||

| Burr 1992 | Wave 1 | CBA | ‐0.6 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐4.5 | ‐ | ||

| Bradlow 1993 | Wave 1 | CBA | ‐0.8 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐4.6 | ‐ | ||

| Bradlow 1993 | Wave 1 | CBA | ‐1.1 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐6.2 | 0.4*/*** | ||

| Baines 1997 | Wave 1‐3, Lincolns | CBA | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐18.5* | ||

| Baines 1997 | Wave 1‐3, Devon | CBA | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐16.4* | ||

| Whynes 1997 | Wave 4 | CBA | ‐0.7 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Corney 1997 | Wave 2 | CBA | 0.2 | ‐ | ‐ | 0.5 | ‐4.8 | ||

| Costs per patient | Absolute level effect (95% CI) | Relative change 3 months (95% CI) | Relative change 6 months (95% CI) | Relative change 12 months (95% CI) | Relative change 24 months (95% CI) | ||||

| Rafferty 1997 | Wave 1 | CITS | ‐922.7 (‐2045.8 to 200.4) | ‐4.9 (‐10.8 to 1.1) | ‐4 (‐10.2 to 2.3) | ‐7.3 (‐14.2 to ‐0.4) | ‐9.1 (‐17.1 to ‐1.1) | ||

| Wilson 1995 | Wave 1 | CITS | ‐0 (‐0.1 to 0.1) | ‐6 (‐26.5 to 14.6) | 6.7 (6.5 to 6.9) | 1 (0.6 to 1.3) | ‐ | ||

| Harris 1996 | Wave 1 | CITS | ‐1.2 (‐3 to 0.7) | ‐1.2 (‐3.1 to 0.7) | ‐0.8 (‐3.3 to 1.7) | 0.1 (‐4 to 4.2) | 2 (‐5.9 to 10) | ||

| Rafferty 1997 | Wave 2 | CITS | ‐566.6 (‐1594.6 to 461.4) | ‐2.6 (‐7.3 to 2) | ‐3.4 (‐8.2 to 1.4) | ‐6.7 (‐11.7 to ‐1.6) | ‐11 (‐16.5 to ‐5.5) | ||

| Rafferty 1997 | Wave 3 | CITS | ‐192.6 (‐1482.6 to 1097.5) | ‐0.6 (‐6 to 4.9) | ‐2.3 (‐7.9 to 3.3) | ‐5.6 (‐11.3 to 0.2) | ‐ | ||

| Wilson 1995 | Wave 2 | CITS | ‐0.1 (‐0.2 to ‐0) | ‐166.8 (‐306.9 to ‐26.5) | 128.6 (127.9 to 129.4) | 66.8 (65.6 to 67.9) | ‐ | ||

| Wilson 1995 | Wave 3 | CITS | ‐0 (‐0.1 to 0.1) | ‐1.2 (‐42.4 to 39.9) | ‐61.5 (‐61.8 to ‐61.2) | ‐79.7 (‐80.2 to ‐79.3) | ‐ | ||

| Harris 1996 | Wave 2 | CITS | ‐2.9 (‐4.1 to ‐1.7) | ‐2.9 (‐4.1 to ‐1.7) | ‐2.8 (‐4.1 to ‐1.4) | ‐2.5 (‐4.1 to ‐0.9) | ‐2 (‐4.3 to 0.3) | ||

| Harris 1996 | Wave 3 | CITS | ‐0.6 (‐2 to 0.7) | ‐0.6 (‐2 to 0.7) | ‐0.6 (‐2 to 0.9) | ‐0.5 (‐2.3 to 1.4) | ‐0.3 (‐3.4 to 2.8) | ||

| Harris 1996 | Wave 4 | CITS | ‐1.5 (‐2.9 to 0) | ‐1.5 (‐3 to 0) | ‐1.9 (‐3.4 to ‐0.5) | ‐2.8 (‐4.5 to ‐1.2) | ‐ | ||

| Harris 1996 | Wave 5 | CITS | ‐1.2 (‐2.3 to ‐0) | ‐1.2 (‐2.4 to ‐0) | ‐2.1 (‐3.1 to ‐1) | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Costs per patient (antiulcer drugs) | Adjusted absolute change | Adjusted relative change 3 months | Adjusted relative change 6 months | Adjusted relative change 12 months | Adjusted relative change 24 months | ||||

| Wilson 1999 | Wave 3/4 | CBA | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐10.6** | ||

| Costs per patient (antidepressants) | Adjusted absolute change | Adjusted relative change 3 months | Adjusted relative change 6 months | Adjusted relative change 12 months | Adjusted relative change 24 months | ||||

| Wilson 1999 | Wave 3/4 | CBA | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐1.9** | ||

| Total prescribing costs | Absolute level effect (95% CI) | Relative change 3 months (95% CI) | Relative change 6 months (95% CI) | Relative change 12 months (95% CI) | Relative change 24 months (95% CI) | ||||

| Harris 1996 | Wave 2 | CITS | ‐1.4 (‐3.6 to 0.9) | 37.6 (‐24.1 to 99.3) | 13.4 (‐57.2 to 84.1) | ‐27.3 (‐109.4 to 54.9) | ‐89.6 (‐183.6 to 4.4) | ||

| Harris 1996 | Wave 3 | CITS | 1 (‐1.5 to 3.4) | ‐18.8 (‐65.6 to 28.4) | ‐35.9 (‐87.6 to 15.8) | ‐69.6 (‐127.4 to ‐11.9) | ‐97 (‐160.7 to ‐33.3) | ||

| Harris 1996 | Wave 4 | CITS | ‐0.3 (‐3.7 to 3) | 10.3 (‐90.6 to 111.2 ) | ‐14.2 (‐121.6 to 93.3) | ‐50.6 (‐166.2 to 65.1) | ‐ | ||

| Harris 1996 | Wave 5 | CITS | ‐0.9 (‐3 to 1.2) | 38.7 (‐50.5 to 127.9) | 21.2 (‐63.9 to 106.2) | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Ireland Indicative drug budgets | Costs per item | Absolute level effect (95% CI) | Relative change 3 months (95% CI) | Relative change 6 months (95% CI) | Relative change 12 months (95% CI) | Relative change 24 months (95% CI) | |||

| Walley 2000 | IDTSS | ITS | 0.1 (‐2.5 to 2.8) | ‐ | ‐ | 0.6 (‐10.1 to 11.7) | 1.2 (‐12.9 to 15.3) | ||

| Total prescribing costs | Absolute level effect (95% CI) | Relative change 3 months (95% CI) | Relative change 6 months (95% CI) | Relative change 12 months (95% CI) | Relative change 24 months (95% CI) | ||||