Abstract

Background

The prevalence of depression in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is high; one study has shown it to be four times that of women without PCOS. Therefore, systematic evaluation of the effectiveness and safety of antidepressants for women with PCOS is important.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of antidepressants in treating depression and other symptoms in women with PCOS.

Search methods

We searched the following databases from inception to June 2012: the Cochrane Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group Trials Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO and Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure, the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (controlled‐trials.com), the National Institute of Health Clinical Trials register (clinicaltrials.gov) and the World Health Organization International Trials Registry Platform search portal (www.who.int/trialsearch/Default.aspx).

Selection criteria

Only randomised controlled trials (RCTs) studying the effectiveness and safety of antidepressants for women with PCOS were included in this review.

Data collection and analysis

The methodological quality of the trials was assessed independently by two review authors, in parallel with data extraction. The risk of bias in the included study was assessed in six domains: 1. sequence generation; 2. allocation concealment; 3. blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors; 4. completeness of outcome data; 5. selective outcome reporting; 6. other potential sources of bias.

Main results

We found no studies reporting any of our primary review outcomes (depression and allied mood disorder scores, quality of life and adverse events). Only one study with 16 women was eligible for inclusion. This study compared sibutramine versus fluoxetine in women with PCOS, and reported only endocrine and metabolic outcomes. It was unclear whether the participants had psychological problems at baseline. No significant difference was found between the groups for any of the measured outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

There is no evidence on the effectiveness and safety of antidepressants in treating depression and other symptoms in women with PCOS.

Keywords: Female, Humans, Antidepressive Agents, Antidepressive Agents/therapeutic use, Cyclobutanes, Cyclobutanes/therapeutic use, Depression, Depression/drug therapy, Fluoxetine, Fluoxetine/therapeutic use, Polycystic Ovary Syndrome, Polycystic Ovary Syndrome/psychology, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

The effect of antidepressants for women with polycystic ovary syndrome

The prevalence of depression in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is high; a study has shown it to be four times that of women without PCOS. Therefore, systematic evaluation of the effectiveness and safety of antidepressants for women with PCOS is important. We found no evidence to support the use or non‐use of antidepressants in women with PCOS, with or without depression. Well‐designed and well‐conducted randomised controlled trials with double blinding should be conducted.

Background

Description of the condition

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), one of the most common female endocrine disorders, affects 5% to 10% of women of reproductive age (ESHRE/ASRM group 2008).The disorder is characterised by chronic anovulation (ongoing failure or absence of ovulation), clinical and biochemical hyperandrogenism (hirsutism, acne, elevated circulating androgens) and obesity (Chittenden 2009; Hart 2004; Mayer 2005). PCOS is a leading cause of subfertility (Boomsma 2008) and accounts for 90% of anovulatory subfertility (Balen 2007). Besides this, PCOS impairs endocrine and metabolic functions; 50% to 70% of women with PCOS have insulin resistance (IR) (Nestler 1997), which is far more than for women without PCOS. Women with PCOS are at greater risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome (including hypertension, dyslipidaemia, impaired fibrinolysis and vasodilation), cardiovascular disease and endometrial cancer (Chittenden 2009; Lobo 2001; Mayer 2005). The cause of PCOS is still unclear (Dasgupta 2008; ESHRE/ASRM group 2008; Padmanabhan 2009). At present, most researchers claim that PCOS is the result of both genetic and environmental factors, but how these factors interact is unknown (Dasgupta 2008; Diamanti‐Kandarakis 2005).

The quality of life (QoL) of women with PCOS is impaired. This is associated with specific features of PCOS (such as obesity, hirsutism, subfertility) and potential mental health problems including depression and allied disorders (McCook 2005). Depression may be an emotional obstacle to seeking medical advice for the PCOS, which may further worsen the syndrome (Herbert 2010). The prevalence of depression in women with PCOS is high; one study has shown it to be four times that of women without PCOS (Hollinrake 2007). Even without diagnosed depression or allied mood disorders, women with PCOS are more anxious and more likely to be in a depressive mood than women without PCOS (Barnard 2007; Benson 2009; Ching 2007; Jedel 2010). The cause of the high prevalence of depression in women with PCOS is not clear; possibly obesity and IR play a part (Himelein 2006; Kerchner 2009; Rasgon 2003).

Description of the intervention

Antidepressants are one of the most commonly used therapies for depression and allied mood disorders. According to their different mechanisms of action, antidepressants can be divided into five broad categories. These are: monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI); tricyclic antidepressants (TCA); tetracyclic antidepressants (TeCA); selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) and serotonin‐norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI). Common side effects of antidepressants include thirst, nausea, low blood pressure, drowsiness, sexual dysfunction and weight gain (Tong 2009). Amenorrhoea has been reported as another side effect (McElroy 2009; Peritogiannis 2007). Hepatonecrosis has been reported as a serious side effect of MAOIs and has limited the use of this type of antidepressant (Tong 2009).

The effect of some antidepressants on weight is relevant to this review because being overweight or obese is common in women with PCOS. This symptom can independently reduce women's QoL (McCook 2005) and is likely to play a part in the greater prevalence of depression in women with PCOS (Himelein 2006). Sibutramine, an SSRI, must be distinguished from the other antidepressants. It is no longer used as an antidepressant and has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as an antiobesity drug. Sibutramine inhibits the reuptake of 5‐hydroxytryptamine (5‐HT, also known as serotonin), resulting in a decrease in appetite, an increase in satiety (thereby naturally reducing calorie intake) and an increase in calorie expenditure that leads to a loss of weight (Halford 2005; Tziomalos 2009). Other SSRIs (fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline) have a similar effect of causing weight loss and have been approved for use in obese people (Epling 2003; Haddock 2002; Halford 2005; Halpern 2003). The weight loss effect of SSRIs might have an added beneficial effect on ameliorating the depressive symptoms of women with PCOS. However, this advantage cannot be found in other classes of antidepressants. The effect of MAOIs and SNRIs on weight is slight, and weight gain is an adverse effect of TCAs and TeCAs.

How the intervention might work

Ameliorating depressive symptoms might encourage women with PCOS with psychological problems to seek medical advice (Herbert 2010). Furthermore, it has been shown that weight loss is associated with beneficial effects on hormone levels, metabolism and the clinical features of PCOS (ESHRE/ASRM group 2008; Vrbikova 2009). So as well as improving depressive symptoms, antidepressants may have beneficial effects on endocrine, metabolic and reproductive functions in women with PCOS. All of these effects may lead to improvements in the QoL of women with PCOS.

In theory, antidepressants could benefit all women with PCOS. Women with PCOS are more likely to be anxious and in a depressive mood compared with women without PCOS, even without diagnosed depression or allied mood disorders (Jedel 2010). Metabolic problems are more common in obese women with PCOS but are also evident in lean women with PCOS (Bideci 2008; Shumak 2009; Veldhuis 2001; Zwirska‐Korczala 2008). Antidepressants may, therefore, be effective in women with PCOS who do not have depression or allied mood disorders and are not obese or overweight. This review sets out to evaluate systematically both the beneficial and side effects of antidepressants in women with PCOS and to identify whether their use is most applicable to any specific subgroups of women.

Why it is important to do this review

It is important to determine whether antidepressants are indicated for treatment of PCOS, whether all classes of antidepressants can be used and whether antidepressant therapy is applicable for all women with PCOS or just those with depression. This review sets out to answer these questions, and to determine whether antidepressants have any advantages compared with other treatments for PCOS.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of antidepressants in treating depression and other symptoms in women with PCOS.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Only randomised controlled trials (RCTs) studying the effectiveness of antidepressants for women with PCOS were included in this review. Quasi‐RCTs and pseudo‐RCTs were excluded. We planned to include cross‐over trials if the data from the first phase were available.

Types of participants

1. Women (including adolescents) of reproductive age (aged 13‐44 years) with PCOS were included.

2. PCOS was identified according to the Rotterdam Consensus (2003) (ESHRE/ASRM group 2004):

olio‐ovulation or anovulation;

clinical or biochemical signs of hyperandrogenism;

polycystic ovaries (determined by gynaecological ultrasound).

Two of the three features listed above must have been present and other aetiologies (congenital adrenal hyperplasia, androgen‐secreting tumours, Cushing's syndrome) excluded.

3. Participants with PCOS both with and without depression were included. Because of the lack of unified diagnostic criteria, depression was identified according to criteria including the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD‐10) (WHO 1992), the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM‐IV) (APA 1994) or the Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders (CCMD) (PICMA 1995); and according to participant scores on validated tools such as the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD), the Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), or the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD).

4. Both obese and non‐obese women with PCOS were included. Obesity was identified according to body mass index (BMI): for Europeans and Americans BMI less than 18.5 is defined as lean, BMI 18.5 or greater to less than 25 as normal, BMI 25 or greater as overweight and BMI 30 of greater as obese; for Asians BMI less than 18.5 is defined as lean, BMI 18.5 or greater to less than 23 as normal, BMI 23 or greater as overweight and BMI 25 or greater as obese (WHO 2000).

5. Women with PCOS with and without IR were included. IR was identified according to homeostasis model assessment‐insulin sensitivity index (HOMA‐ISI) (Tara 2004).

Types of interventions

1. Antidepressant medications versus placebo, no treatment, oral contraceptives, metformin, lifestyle changes, antiobesity drugs, or surgery; with and without co‐medications.

2. Antidepressant medication combined with other treatments versus other treatments

3. One antidepressant versus another antidepressant.

4. Comparison of different doses of the same antidepressant.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

(1) Depression and allied mood disorder scores

We planned to assess depression and allied mood disorders using the following hierarchy of tools (as reported by the included studies):

the BDI;

other validated generic scales;

condition‐specific scales.

(2) Quality of life

We planned to evaluate QoL using the following hierarchy of tools (as reported by the included studies):

the Short Form‐36 (SF‐36);

the Quality‐of‐Life Questionnaire for Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOSQ);

other validated generic scales;

other condition‐specific scales.

(3) Adverse events

Any adverse event: how many women had any adverse event.

Specific adverse events: how many women had a specific type of adverse event.

Secondary outcomes

(4) Reproductive factors

Live birth rate (excluding assisted conception), defined as the number of women giving birth to living baby divided by the total number of women seeking pregnancy.

Ovulation (number of ovulatory menstrual cycles).

Menstrual regularity.

(5) Endocrine factors

Levels of total testosterone (tT), free testosterone (fT), luteinising hormone (LH), follicle‐stimulating hormone (FSH), LH/FSH, sex hormone‐binding globulin (SHBG), dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate (DHEA‐S), oestrogens (E2) or progesterone (P).

(6) Metabolic factors

Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) (including fasting glucose, fasting insulin, glucose/insulin ratio, insulin sensitivity index (ISI), insulin resistance index (IRI) and homeostasis model assessment‐insulin resistance (HOMA‐IR)); and levels of total cholesterol (TC), high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL‐C), low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C), triglyceride (TG), apolipoprotein A (Apo A) and apolipoprotein B (Apo B).

(7) Anthropometric factors

Weight, BMI, waist‐to‐hip ratio and the Ferriman‐Gallwey score (for the evaluation of hirsutism).

Search methods for identification of studies

The literature search aimed to locate RCTs regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press or in progress).

Electronic searches

1. We searched the Cochrane Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group (MDSG) Trials Register (inception to 8 June 2012) using the search strategy as follows: Keywords CONTAINS "PCOS" or "polycystic ovary syndrome" or "polycystic ovary syndrome" or Title CONTAINS "PCOS" or "polycystic ovary syndrome" or "polycystic ovary syndrome" AND Keywords CONTAINS "anti‐depressants" or "antidepressants" or "selective serotonin re‐uptake inhibitor" or "SSRI" or "SSRIs" or "serotonin‐norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor" or "serotonin reuptake inhibitor" or "SNRI" or "TCA" or "monoamine" or "MOAI" or "TeCA" or "monoaminoxidase" or Title CONTAINS "anti‐depressants" or "antidepressants" or "selective serotonin re‐uptake inhibitor" or "SSRI" or "SSRIs" or "serotonin‐norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor" or "serotonin reuptake inhibitor" or "SNRI" or "TCA" or "monoamine" or "MOAI" or "TeCA" or "monoaminoxidase".

2. The following databases were also searched (inception to 8 June 2012): the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library), MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI).

The MEDLINE search was combined with the Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy for identifying randomised trials that appears in the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Version 5.1.0, Chapter 6, 6.4.11).The EMBASE search was combined with trial filters developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN).

Please see Appendix 1, Appendix 2, Appendix 3, Appendix 4 and Appendix 5 for search strategies for each database.

3. We searched for ongoing or registered RCTs in the following databases: meta Register of Controlled Trials (controlled‐trials.com), the National Institute of Health Clinical Trials register (clinicaltrials.gov) and the World Health Organization International Trials Registry Platform search portal (www.who.int/trialsearch/Default.aspx).

Searching other resources

1. Reference lists of relevant trials, reviews and textbooks were checked.

2. Experts and pharmaceutical companies in the field were contacted.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (ZJ, WX) independently performed the searches and scanned the titles and abstracts of every record retrieved. All potentially relevant articles were investigated as full text. The review authors (ZJ, WX and XL) then independently assessed whether studies met the inclusion criteria. We planned to resolve disagreements by discussion. If there was not enough information in an article to make this decision, we planned to contact the original trial authors for further information.

Data extraction and management

Data were independently extracted by two review authors (ZJ, WX) using forms designed to follow The Cochrane Collaboration guidelines. Data on study characteristics and results, including methods, participants, interventions, outcomes and adverse events, were extracted. We planned to resolve disagreements by discussion with a third review author (XL).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The methodological quality of the trials was assessed independently by two review authors (ZJ, WX). The risk of bias in the studies was assessed in six domains: 1. sequence generation; 2. allocation sequence concealment; 3. blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors; 4. completeness of outcome data; 5. selective outcome reporting; 6. other potential sources of bias.

We followed the detailed descriptions of these categories provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Version 5.1.0) (Higgins 2011).

Measures of treatment effect

We planned to analyse continuous data by using mean differences (MD), and dichotomous data by Peto odds ratios (OR), with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Ordinal data (for example, QoL scores) were to be treated as continuous data.

Unit of analysis issues

We planned that if any cross‐over trials were included, only the first‐phase data would be included.

Dealing with missing data

We planned to contact trial authors by telephone or email to ask for missing data. If suitable data were available, intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis was conducted. If suitable data were unobtainable, we planned to assume that participants with unreported outcomes had not had improvements for our primary outcome.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to assess statistical heterogeneity using the Chi2 test with a 10% level of statistical significance and the I2 statistic to estimate the total variation across studies that was due to heterogeneity rather than chance. We planned that an I2 statistic greater than 50% would be taken to indicate substantial heterogeneity (Higgins 2003). If substantial heterogeneity was detected, we planned to explore possible explanations in sensitivity analyses (see below).

Assessment of reporting biases

If there were 10 or more studies in an analysis, we planned to assess review‐wide reporting bias by constructing a funnel plot.

Data synthesis

We planned to pool data if studies were sufficiently similar, using Review Manager (Version 5.0.1) software (RevMan 2011). If pooling was not appropriate, we planned to perform only descriptive analysis. We planned to use a fixed‐effect model unless there was substantial heterogeneity, in which case a random‐effects model would be used.

We planned to combine the data from primary studies in the following comparisons.

-

Antidepressant versus placebo, no treatment, oral contraceptive or surgery (with or without co‐medications) stratified by dose of antidepressant:

low dose;

high dose.

-

Antidepressant versus lifestyle changes, stratified by:

antidepressant versus diet;

antidepressant versus exercise;

antidepressant versus diet combined with exercise.

-

Antidepressant versus metformin or antiobesity drug, stratified by dose of each:

low dose of antidepressant;

high dose of antidepressant;

low dose of metformin or antiobesity drug;

high dose of metformin or antiobesity drug.

-

Antidepressant combined with other treatment versus other treatment, such as oral contraceptive, metformin, lifestyle changes, surgery, stratified by dose of antidepressant:

low dose;

high dose.

-

One antidepressant versus another antidepressant, stratified by dose of both antidepressants.

low dose;

high dose.

An antidepressant in a low dose versus the same antidepressant in a high dose.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If substantial heterogeneity was detected, we planned to explore it, based on the characteristics of study participants:

women with PCOS having depression or allied mood disorders, or not;

women with PCOS who were overweight or obese, or not;

women with PCOS who had IR, or not;

women diagnosed using differing criteria for PCOS.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses in order to explore the influence of the following factors on review findings:

study quality (restricting analysis to studies which reported adequate methods of allocation concealment and blinding, and which used ITT analysis);

funding source: restricting analysis to studies without commercial funding.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

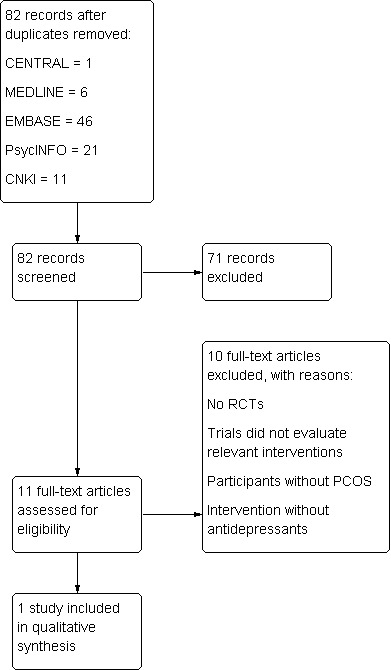

A total of 85 references (excluding duplications) were identified by the electronic searching in June 2012, 74 in English and 11 in Chinese. Eleven studies were potentially eligible and were retrieved in full text. One study met our inclusion criteria. Ten studies were excluded. See study tables: Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies. We prepared a PRISMA flow diagram to describe the articles found from our searches (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Study design

The included trial was a RCT conducted in Turkey (Karabacak 2004). This was a single centre two‐arm parallel arm study.

Participants

A total of 16 women were enrolled. It was unclear whether they had psychological problems at baseline. The PCOS diagnostic criteria were a combination of oligo‐ovulation or anovulation, clinical and biochemical signs of hyperandrogenism, and polycystic ovaries (determined by gynaecological ultrasound) (ESHRE/ASRM group 2004). The baseline characteristics among groups were comparable. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were listed in Characteristics of included studies. Dropouts and withdrawals had not been reported

Interventions

The included study compared fluoxetine with sibutramine. The dose of treatment is detailed in Characteristics of included studies. The treatment duration was 10 days (Karabacak 2004).

Outcomes

The included study did not report any of the primary outcomes of the review. It reported the following secondary outcomes:

endocrine outcomes: LH, FSH and LH/FSH were reported;

metabolic outcomes: OGTT were reported.

For abbreviations see Table 1.

1. Abbreviations used.

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| Apo A | Apolipoprotein A |

| Apo B | Apolipoprotein B |

| BDI | Beck Depression Inventory |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CCMD | Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CNKI | Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure |

| DHEA‐S | Dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate |

| DSM‐IV | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition |

| E2 | Oestrogens |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FSH | Follicle‐stimulating hormone |

| fT | Free testosterone |

| HAD | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| HDL‐C | High‐density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| HOMA‐IR | Homeostasis model assessment‐insulin resistance |

| HOMA‐ISI | Homeostasis model assessment‐insulin sensitivity index |

| HRSD | Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression |

| ICD‐10 | International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision |

| IR | Insulin resistance |

| IRI | Insulin resistance index |

| ISI | Insulin sensitivity index |

| ITT | Intention‐to‐treat |

| LDL‐C | Low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| LH | Luteinising hormone |

| MADRS | Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Rating Scale |

| MAOI | Monoamine oxidase inhibitors |

| MD | Mean difference |

| MDSG | Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group |

| NE | Norepinephrine |

| OGTT | Oral glucose tolerance test |

| OR | Odds ratios |

| P | Progesterone |

| PCOS | Polycystic ovary syndrome |

| PCOSQ | Quality‐of‐Life Questionnaire for Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome |

| QoL | Quality of life |

| RCT | Randomised controlled trial |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SF‐36 | Short Form‐36 |

| SHBG | Sex hormone‐binding globulin |

| SNRI | Serotonin‐norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors |

| SSRI | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors |

| T | Testosterone |

| tT | Total testosterone |

| TC | Total cholesterol |

| TCA | Tricyclic antidepressants |

| TeCA | Tetracyclic antidepressants |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| WHR | Waist‐to‐hip ratio |

| MD | Mean difference |

| 5‐HT | Serotonin |

Excluded studies

Ten studies were excluded for different reasons:

5/10 were not RCTs;

1/10 reported no comparisons of interest;

1/10 had participants without PCOS;

3/10 reported intervention without antidepressants.

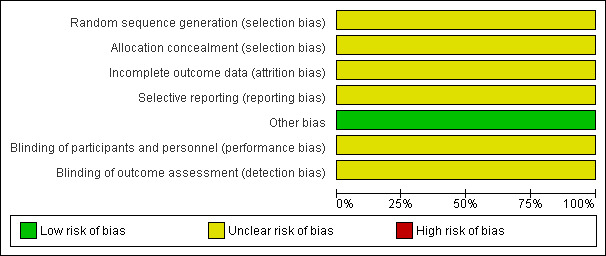

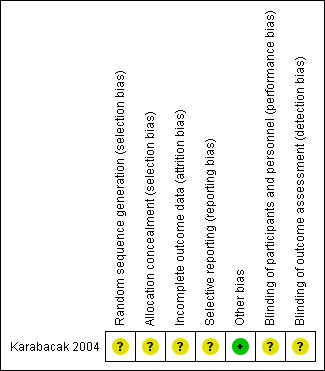

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation

The included study did not report what methods were used for sequence generation or allocation concealment, and it was rated as at unclear risk of bias for these domains.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Blinding

Blinding was not reported in the included study, so we judged it to be at unclear risk of performance and detection bias. See Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Incomplete outcome data

The included study did not state how many women were analysed and we rated it as at unclear risk of attrition bias (Karabacak 2004).

Selective reporting

No adverse events were reported in the included study and we rated it as at unclear risk of selective reporting bias. See Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Other potential sources of bias

No other potential source of bias was identified.

The risk of review‐wide reporting bias could not be assessed because there were insufficient studies to do a funnel plot.

Effects of interventions

Because there was only one study included, we described the results in narrative form.

1 Antidepressants plus other treatments versus other treatments

1.1 Sibutramine versus fluoxetine

1.1.1 Depression and allied mood disorder scores

Depression and allied mood disorder scores were not reported in the included study (Karabacak 2004).

1.1.2 Quality of life (QoL)

QoL was not reported in the included study (Karabacak 2004).

1.1.3 Adverse events

Adverse events were not reported in the included study (Karabacak 2004).

1.1.4 Reproductive factors

Reproductive factors were not reported in the included study (Karabacak 2004).

1.1.5 Endocrine factors

Luteinising hormone (U/L)

LH increased after treatment in the fluoxetine treatment group, but decreased in the sibutramine treatment group. However these differences were not statistically significant (baseline 8.53 ± 6.96 vs. 7.28 ± 5.37, after treatment 9.42 ± 11.85 vs. 5.24 ±3 .85, P value > 0.05, 16 women) (Karabacak 2004).

Follicle‐stimulating hormone (U/L)

The FSH level decreased slightly in both fluoxetine and sibutramine groups, but the differences in and between the groups were not statistically significant (baseline 4.44 ± 2.13 vs. 3.84 ± 1.64, after treatment 3.23 ± 1.74 vs. 3.68 ± 1.48, P value > 0.05, 16 women) (Karabacak 2004).

Luteinising hormone/follicle‐stimulating hormone

LH/FSH increased in fluoxetine group and decreased in sibutramine group, but the differences in and between the groups were not statistically significant (baseline 2.08 ± 1.44 vs. 1.78 ± 1.05, after treatment 2.32 ± 1.74 vs. 1.57 ± 1.12, P value > 0.05, 16 women) (Karabacak 2004).

1.1.6 Metabolic factors

Oral glucose tolerance test

No significant differences between pre‐treatment and post‐treatment were observed for OGTT (P value > 0.05). Detailed information could not be obtained from primary authors (Karabacak 2004).

1.1.7 Anthropometric factors

Anthropometric factors were not reported in the included study (Karabacak 2004).

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review did not find any studies that reported clinical outcomes in women with PCOS treated for depression. The single eligible study reported only laboratory test outcomes. No significant difference was found for any outcomes between sibutramine and fluoxetine.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The applicability of the included study was very limited because none of the primary outcomes of this review were reported and it addressed only secondary laboratory outcomes. Attempts were made to contact the study author for more details, but no reply was received. The limited evidence applies only to women with PCOS. It was unclear whether women in the included study were depressed at baseline. Because of the severe limitations of the current evidence, the clinical question of this review cannot be answered.

Quality of the evidence

Only one very small RCT with 16 women was included in the present review. It reported no clinically relevant outcomes, and it was of very limited quality, with inadequate reporting of study methods.

Potential biases in the review process

We did not identify any potential biases in the review process.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We found no other systematic review of antidepressants for women with PCOS.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is no evidence on the effectiveness and safety of antidepressants in treating depression and other symptoms in women with PCOS.

Implications for research.

Large and well‐designed RCTs with double blinding should be conducted on the use of antidepressants for women with PCOS, as there is currently no evidence to guide clinical practice. Study authors should report methodology in detail, such as randomisation and allocation concealment methods.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 31 May 2013 | Review declared as stable | As no studies are expected, this review will not be updated. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 7, 2010 Review first published: Issue 5, 2013

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 15 July 2012 | New search has been performed | Full review |

| 13 July 2010 | Amended | Edit made to author details |

Acknowledgements

We thank Jane Clarke (the ex‐Managing Editor), Helen Nagels (Managing Editor), Marian Showell (Trials Search Coordinator) and the Cochrane Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group for their valuable assistance in preparing this manuscript.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy (The Cochrane Library)

1 exp Polycystic Ovary Syndrome/ (617) 2 Polycystic Ovar$.tw. (893) 3 PCOS.tw. (599) 4 PCOD.tw. (22) 5 stein leventh$.tw. (3) 6 (ovar$ adj2 sclerocystic).tw. (0) 7 (ovar$ adj2 degeneration).tw. (1) 8 PCO.tw. (288) 9 or/1‐8 (1245) 10 exp antidepressive agents/ or exp antidepressive agents, second‐generation/ or exp antidepressive agents, tricyclic/ (8608) 11 antidepress$.tw. (5575) 12 TCA.tw. (145) 13 monoamine$.tw. (701) 14 MAOI$.tw. (93) 15 TeCA$.tw. (10) 16 selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor$.tw. (947) 17 SSRI$.tw. (945) 18 serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor$.tw. (77) 19 SNRI$.tw. (56) 20 monoaminoxidase$.tw. (3) 21 serotonin uptake inhibitor$.tw. (91) 22 or/10‐21 (12,020) 23 22 and 9 (1)

Appendix 2. MEDLINE search strategy (Ovid)

1 exp Polycystic Ovary Syndrome/ (8620) 2 Polycystic Ovar$.tw. (8437) 3 PCOS.tw. (4519) 4 PCOD.tw. (252) 5 stein leventh$.tw. (582) 6 (ovar$ adj2 sclerocystic).tw. (80) 7 (ovar$ adj2 degeneration).tw. (89) 8 PCO.tw. (3245) 9 or/1‐8 (13,266) 10 exp antidepressive agents/ or exp antidepressive agents, second‐generation/ or exp antidepressive agents, tricyclic/ (110,914) 11 antidepress$.tw. (40,676) 12 TCA.tw. (5824) 13 monoamine$.tw. (25,633) 14 MAOI$.tw. (897) 15 TeCA$.tw. (310) 16 selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor$.tw. (6664) 17 SSRI$.tw. (5749) 18 serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor$.tw. (356) 19 SNRI$.tw. (524) 20 monoaminoxidase$.tw. (141) 21 serotonin uptake inhibitor$.tw. (506) 22 or/10‐21 (151,085) 23 22 and 9 (29) 24 randomized controlled trial.pt. (315,458) 25 controlled clinical trial.pt. (83,272) 26 randomized.ab. (230,747) 27 placebo.tw. (135,547) 28 clinical trials as topic.sh. (157,457) 29 randomly.ab. (169,531) 30 trial.ti. (98,696) 31 (crossover or cross‐over or cross over).tw. (51,826) 32 or/24‐31 (772,305) 33 exp animals/ not humans.sh. (3,656,215) 34 32 not 33 (713,180) 35 23 and 34 (6)

Appendix 3. EMBASE search strategy (Ovid)

1 exp ovary polycystic disease/ (14,506) 2 Polycystic Ovar$.tw. (11,443) 3 PCOS.tw. (6734) 4 PCOD.tw. (304) 5 stein leventh$.tw. (538) 6 (ovar$ adj2 sclerocystic).tw. (81) 7 (ovar$ adj2 degeneration).tw. (96) 8 PCO.tw. (2779) 9 or/1‐8 (18,179) 10 exp antidepressant agent/ (273,673) 11 antidepress$.tw. (56,351) 12 TCA.tw. (7138) 13 monoamine$.tw. (27,950) 14 MAOI$.tw. (1145) 15 TeCA$.tw. (524) 16 selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor$.tw. (9189) 17 SSRI$.tw. (9272) 18 serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor$.tw. (561) 19 SNRI$.tw. (1058) 20 monoaminoxidase$.tw. (157) 21 serotonin uptake inhibitor$.tw. (582) 22 or/10‐21 (304,679) 23 22 and 9 (433) 24 Clinical Trial/ (865,899) 25 Randomized Controlled Trial/ (322,492) 26 exp randomisation/ (58,269) 27 Single Blind Procedure/ (15,924) 28 Double Blind Procedure/ (109,025) 29 Crossover Procedure/ (33,967) 30 Placebo/ (198,958) 31 Randomi?ed controlled trial$.tw. (74,924) 32 Rct.tw. (9244) 33 random allocation.tw. (1144) 34 randomly allocated.tw. (17,121) 35 allocated randomly.tw. (1806) 36 (allocated adj2 random).tw. (706) 37 Single blind$.tw. (12,161) 38 Double blind$.tw. (127,705) 39 ((treble or triple) adj blind$).tw. (268) 40 placebo$.tw. (174,566) 41 prospective study/ (204,466) 42 or/24‐41 (1,247,638) 43 case study/ (15,680) 44 case report.tw. (224,934) 45 abstract report/ or letter/ (832,694) 46 or/43‐45 (1,068,768) 47 42 not 46 (1,212,774) 48 23 and 47 (46)

Appendix 4. PsycINFO search strategy (Ovid)

1 Polycystic Ovar$.tw. (192) 2 PCOS.tw. (103) 3 PCOD.tw. (5) 4 stein leventh$.tw. (2) 5 (ovar$ adj2 sclerocystic).tw. (1) 6 (ovar$ adj2 degeneration).tw. (0) 7 PCO.tw. (36) 8 exp endocrine sexual disorders/ (757) 9 or/1‐8 (920) 10 exp antidepressant drugs/ or exp serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors/ or exp sertraline/ or exp monoamine oxidase inhibitors/ (29,143) 11 antidepress$.tw. (25,798) 12 TCA.tw. (437) 13 monoamine$.tw. (6375) 14 MAOI$.tw. (490) 15 TeCA$.tw. (6) 16 selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor$.tw. (4739) 17 SSRI$.tw. (3958) 18 serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor$.tw. (233) 19 SNRI$.tw. (330) 20 monoaminoxidase$.tw. (36) 21 serotonin uptake inhibitor$.tw. (184) 22 or/10‐21 (45,709) 23 9 and 22 (21)

Appendix 5. CNKI search strategy (Chinese database)

1 polycystic ovary syndrome (8560) 2 polycystic ovary (7682) 3 ovary polycystic disease (30) 4 or/1‐3 (9323) 5 antidepressant (12,765) 6 tricyclic antidepressant (1073) 7 monoamine oxidase inhibitor (2695) 8 serotonin uptake inhibitor (1052) 9 or/5‐8 (12,854) 10 random* (966,377) 11 4 and 9 and 10 (11)

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Karabacak 2004.

| Methods | RCT Setting: Turkey, single centre Number of participants randomised: 16 |

|

| Participants | Summary: PCOS PCOS diagnostic criteria: observance of polycystic ovaries by transvaginal ultrasound examination performed during the first days of menstruation; oligo/amenorrhoea (intermenstrual interval ≥ 36) and hirsutism (Ferriman‐Gallwey score ≥ 7); with or without raised serum testosterone level Inclusion criteria: PCOS Exclusion criteria: did not mention in the article. The authors had been contacted, but no reply Baseline characteristics: the sibutramine group and the fluoxetine group are comparable in age, BMI, FSH, LH, androstenedione, free testosterone, insulin Reasons for withdrawals: not applicable. All participants completed the study and were included in the analysis |

|

| Interventions | Treatment: sibutramine 10 mg/day Control: fluoxetine 20 mg/day Duration: 10 days Co‐interventions: no |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | ‐ | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Did not describe in the article. The authors had been contacted, but no reply |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Did not describe in the article. The authors had been contacted, but no reply |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Does not state how many women were analysed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Adverse events not reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | None detected |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Did not describe in the article. The authors had been contacted, but no reply |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Did not describe in the article. The authors had been contacted, but no reply |

BMI: body mass index; FSH: follicle‐stimulating hormone; LH: luteinising hormone; PCOS: polycystic ovary syndrome; RCT: randomised controlled trial.

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Amer 2009 | Intervention without antidepressants |

| Florakis 2008 | Intervention without antidepressants |

| Geddes 2010 | Participants without PCOS |

| Hirschberg 2009 | Review article |

| Lazurova 2004 | Participants with or without PCOS; non‐randomised controlled trial |

| Lindholm 2008 | Intervention without antidepressants |

| Mansson 2008 | Participants with or without PCOS; case control study |

| Sabuncu 2003 | Intervention without antidepressants |

| Shi 2008 | Participants with or without PCOS; case‐control study |

| Tziomalos 2010 | Participants with or without PCOS; review article |

PCOS: polycystic ovary syndrome.

Differences between protocol and review

The outcome of depression was moved from secondary to primary outcome.

The objectives were changed to include improving QoL and depression.

Contributions of authors

Jing Zhuang: drafting the protocol; literature searching; selection of trials for inclusion or exclusion; assessing methodological quality of studies; data extraction, analysis and presentation; co‐drafting of the review.

Xianding Wang: literature searching; selection of trials for inclusion or exclusion; assessing methodological quality of studies; data extraction, analysis and presentation; contacting primary authors; co‐drafting of the review.

Liangzhi Xu: resolving disagreements regarding study selection; assessing methodological quality of studies; assistance with statistics; review revision.

Taixiang Wu: data analysis and presentation; assistance with statistics; review revision.

Deying Kang: data analysis and presentation; assistance with statistics; review revision.

Sources of support

Internal sources

West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University, China.

Chinese Cochrane Center, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, China.

External sources

No sources of support supplied

Declarations of interest

The authors declared that no conflict of interest was involved in the analysis or interpretation of data, or in the writing of the systematic review.

Stable (no update expected for reasons given in 'What's new')

References

References to studies included in this review

Karabacak 2004 {published data only}

- Karabacak IY, Karabacak O, Toruner FB, Akdemir O, Arslan M. Treatment effect of sibutramine compared to fluoxetine on leptin levels in polycystic ovary disease. Gynecological Endocrinology 2004;19(4):196‐201. [DOI: 10.1080/09513590400012077] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Amer 2009 {published data only}

- Amer SA, Li TC, Metwally M, Emarh M, Ledger WL. Randomized controlled trial comparing laparoscopic ovarian diathermy with clomiphene citrate as a first‐line method of ovulation induction in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Human Reproduction 2009;24(1):219‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Florakis 2008 {published data only}

- Florakis D, Diamanti‐Kandarakis E, Katsikis I, Nassis GP, Karkanaki A, Georgopoulos N, et al. Effect of hypocaloric diet plus sibutramine treatment on hormonal and metabolic features in overweight and obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomized, 24‐week study. International Journal of Obesity 2008;32(4):692‐9. [DOI: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803777] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Geddes 2010 {published data only}

- Geddes JR, Goodwin GM, Rendell J, Azorin JM, Cipriani A, Ostacher MJ, et al. Lithium plus valproate combination therapy versus monotherapy for relapse prevention in bipolar I disorder (BALANCE): a randomised open‐label trial. Lancet 2010;375(9712):385‐95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hirschberg 2009 {published data only}

- Hirschberg A. Polycystic ovary syndrome, obesity and reproductive implications. Womens Health 2009;5(5):529‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lazurova 2004 {published data only}

- Lazurova I, Dravecka I, Kraus V, Petrovicova J. Metformin versus sibutramine in the treatment of hyperinsulinemia in chronically anovulating women. Bratisl Lek Listy 2004;105(5‐6):207‐10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lindholm 2008 {published data only}

- Lindholm A, Bixo M, Bjorn I, Wolner‐Hanssen P, Eliasson M, Larsson A, et al. Effect of sibutramine on weight reduction in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Fertility and Sterility 2008;89:1221‐8. [DOI: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.05.002] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mansson 2008 {published data only}

- Mansson M, Holte J, Landin‐Wilhelmsen K, Dahlgren E, Johansson A, Landen M. Women with polycystic ovary syndrome are often depressed or anxious ‐ a case control study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2008;33(8):1132‐8. [DOI: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.06.003] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sabuncu 2003 {published data only}

- Sabuncu T, Harma M, Harma M, Nazligul Y, Kilic F. Sibutramine has a positive effect on clinical and metabolic parameters in obese patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertility and Sterility 2003;80(5):1199‐204. [DOI: 10.1016/S0015-0282(03)02162-9] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shi 2008 {published data only}

- Shi X, Zhang L, Fu S. Psychiatric symptoms and monoamine neurotransmitter in serum of PCOS with infertility patients. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology 2008;16(3):294‐6. [Google Scholar]

Tziomalos 2010 {published data only}

- Tziomalos K, Dimitroula HV, Katsiki N, Savopoulos C, Hatzitolios AI. Effects of lifestyle measures, antiobesity agents, and bariatric surgery on serological markers of inflammation in obese patients. Mediators of inflammation 2010;2010:364957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

APA 1994

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐IV). 4th Edition. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994. [Google Scholar]

Balen 2007

- Balen AH, Rutherford AJ. Managing anovulatory infertility and polycystic ovary syndrome. BMJ 2007;335:663‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Barnard 2007

- Barnard L, Ferriday D, Guenther N, Strauss B, Balen AH, Dye L. Quality of life and psychological well being in polycystic ovary syndrome. Human Reproduction 2007;22(8):2279‐86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Benson 2009

- Benson S, Hahn S, Tan S, Mann K, Janssen OE, Schedlowski M, et al. Prevalence and implications of anxiety in polycystic ovary syndrome: results of an internet‐based survey in Germany. Human Reproduction 2009;24(6):1446‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bideci 2008

- Bideci A, Camurdan MO, Yesilkaya E, Demirel F, Cinaz P. Serum ghrelin, leptin and resistin levels in adolescent girls with polycystic ovary syndrome. The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research 2008;34:578‐84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Boomsma 2008

- Boomsma CM, Fauser BC, Macklon NS. Pregnancy complications in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine 2008;26:72‐84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ching 2007

- Ching HL, Burke V, Stuckey BG. Quality of life and psychological morbidity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: body mass index, age and the provision of patient information are significant modifiers. Clinical Endocrinology 2007;66(3):373‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chittenden 2009

- Chittenden BG, Fullerton G, Maheshwari A, Bhattacharya S. Polycystic ovary syndrome and the risk of gynaecological cancer: a systematic review. Reproductive Biomedicine Online 2009;19:398‐405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dasgupta 2008

- Dasgupta S, Reddy BM. Present status of understanding on the genetic etiology of polycystic ovary syndrome. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine 2008;54:115‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Diamanti‐Kandarakis 2005

- Diamanti‐Kandarakis E, Piperi C. Genetics of polycystic ovary syndrome: searching for the way out of the labyrinth. Human Reproduction Update 2005;11:631‐43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Epling 2003

- Epling J, Family Practice Inquiries Network. Is fluoxetine an effective therapy for weight loss in obese patients?. American Family Physician 2003;68(12):2437‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

ESHRE/ASRM group 2004

- The Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM‐sponsored PCOS consensus workshop group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long‐term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Human Reproduction 2004;19:41‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

ESHRE/ASRM group 2008

- The Thessaloniki ESHRE/ASRM‐Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Consensus on infertility treatment related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Human Reproduction 2008;23:462‐77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Haddock 2002

- Haddock CK, Poston WS, Dill PL, Foreyt JP, Ericsson M. Pharmacotherapy for obesity: a quantitative analysis of four decades of published randomized clinical trials. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders 2002;26(2):262‐73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Halford 2005

- Halford JC, Harrold JA, Lawton CL, Blundell JE. Serotonin (5‐HT) drugs: effects on appetite expression and use for the treatment of obesity. Current Drug Targets 2005;6(2):201‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Halpern 2003

- Halpern A, Mancini MC. Treatment of obesity: an update on anti‐obesity medications. Obesity Reviews 2003;4(1):25‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hart 2004

- Hart R, Hickey M, Franks S. Definitions, prevalence and symptoms of polycystic ovaries and polycystic ovary syndrome. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2004;18:671‐83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Herbert 2010

- Herbert D, Lucke J, Dobson A. Depression: an emotional obstacle to seeking medical advice for infertility. Fertility and Sterility 2010;94(5):1817‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2003

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analysis. BMJ 2003;327:557‐60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of interventions 5.1.0 [updated March 2011].. The Cochrane Collaboration 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Himelein 2006

- Himelein MJ, Thatcher SS. Polycystic ovary syndrome and mental health: a review. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey 2006;61(11):723‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hollinrake 2007

- Hollinrake E, Abreu A, Maifeld M, Voorhis BJ, Dokras A. Increased risk of depressive disorders in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertility and Sterility 2007;87(6):1369‐76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jedel 2010

- Jedel E, Waern M, Gustafson D, Landen M, Eriksson E, Holm G, et al. Anxiety and depression symptoms in women with polycystic ovary syndrome compared with controls matched for body mass index. Human Reproduction 2010;25(2):450‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kerchner 2009

- Kerchner A, Lester W, Stuart SP, Dokras A. Risk of depression and other mental health disorders in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a longitudinal study. Fertility and Sterility 2009;91(1):207‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lobo 2001

- Lobo RA. Priorities in polycystic ovary syndrome. The Medical Journal of Australia 2001;174:554‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mayer 2005

- Meyer C, McGrath BP, Teede HJ. Overweight women with polycystic ovary syndrome have evidence of subclinical cardiovascular disease. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2005;90:5711‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McCook 2005

- McCook JG, Reame NE, Thatcher SS. Health‐related quality of life issues in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing 2005;34(1):12‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McElroy 2009

- McElroy SL, Guerdjikova AI, Martens B, Keck PE Jr, Pope HG, Hudson JI. Role of antiepileptic drugs in the management of eating disorders. CNS Drugs 2009;23:139‐56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nestler 1997

- Nestler JE. Insulin regulation of human ovarian androgens. Human Reproduction 1997;12:53‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Padmanabhan 2009

- Padmanabhan V. Polycystic ovary syndrome "A riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2009;94:1883‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Peritogiannis 2007

- Peritogiannis V, Goulia P, Pappas D, Hyphantis T, Mavreas V. Amenorrhea after sertraline introduction in an amisulpride‐treated patient with undiagnosed polycystic ovary disease. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 2007;27:235‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

PICMA 1995

- Psychiatric Institute of the Chinese Medical Association. Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders. Nan Jing: Chinese Medical Association 1995; Vol. 3.

Rasgon 2003

- Rasgon NL, Rao RC, Hwang S, Altshuler LL, Elman S, Zuckerbrow‐Miller J, et al. Depression in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: clinical and biochemical correlates. Journal of Affective Disorders 2003;74(3):299‐304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2011 [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.1. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011.

Shumak 2009

- Shumak SL. Even lean women with PCOS are insulin resistant. BMJ 2009;338:b954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tara 2004

- Tara MW, Jonathan CL, David RM. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care 2004;27(6):1485‐95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tong 2009

- Tong X, Tong E. The history and development of antidepressants. Herald of Medicine 2009;28(2):135‐9. [Google Scholar]

Tziomalos 2009

- Tziomalos K, Krassas GE, Tzotzas T. The use of sibutramine in the management of obesity and related disorders: an update. Vascular Health & Risk Management 2009;5:441‐52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Veldhuis 2001

- Veldhuis JD, Pincus SM, Garcia‐Rudaz MC, Ropelato MG, Escobar ME, Barontini M. Disruption of the synchronous secretion of leptin, LH, and ovarian androgens in nonobese adolescents with the polycystic ovarian syndrome. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2001;86:3772‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vrbikova 2009

- Vrbikova J, Hainer V. Obesity and polycystic ovary syndrome. Obesity Facts 2009;2(1):26‐35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

WHO 1992

- World Health Organization. The ICD‐10 Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization 1992.

WHO 2000

- World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organization Technical Report Service 2000;894:i‐xii, 1‐253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zwirska‐Korczala 2008

- Zwirska‐Korczala K, Sodowski K, Konturek SJ, Kuka D, Kukla M, Brzozowski T, et al. Postprandial response of ghrelin and PYY and indices of low‐grade chronic inflammation in lean young women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology 2008;59:161‐78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]