Abstract

Background

Apathy is a deficiency in overt behavioural, emotional and cognitive components of goal‐directed behaviour. It is a common occurrence after traumatic brain injury (TBI), with widespread impact. We have systematically reviewed studies examining the effectiveness of interventions for apathy in the TBI population.

Objectives

To investigate the effectiveness of interventions for apathy in adults who have sustained a TBI. This was evaluated by changes in behavioural, cognitive and emotional measures of apathy.

Search methods

We searched the following databases up to January 2008: CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library 2008, Issue 1), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, ACP Journal Club, MEDLINE (1950 to Jan 2008), EMBASE (1980 to Jan 2008), PsycINFO (1806 to Jan 2008), CINAHL (1982 Jan 2008), PsycBITE, AMED (1985 to Jan 2008), www.controlled‐trials.com, www.clinicaltrials.gov and www.actr.org.au.The Cochrane Injuries Group's Specialised Register was searched to Jan 2009. Additionally, we examined key conference proceedings and reference lists of included trials to identify further studies meeting the inclusion criteria.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of interventions specifically targeting apathy for people with TBI.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors (ALB and RLT) independently assessed studies for inclusion. We rated the methodological quality of included studies and extracted data.

Main results

We identified one trial that satisfied the inclusion criteria for this review. This trial (N = 21) showed that cranial electrotherapy stimulation (CES) decreased inertia, which is a component of apathy, while no changes were seen in the sham treatment or no treatment control groups. Given that no between‐group analysis was reported, it was not possible to determine if the CES treatment group improved significantly more than the control group.

Authors' conclusions

No evidence was provided to support the use of CES treatment for inertia, a component of apathy. Between‐group statistical analyses were not conducted and it was therefore not possible to determine the efficacy of the treatment relative to no treatment or sham treatment. Results regarding the effectiveness of treatment can only be inferred, and this evidence is based on only one trial with a small sample size. More randomised controlled trials evaluating different ways of treating apathy would be valuable. Trials should have larger sample sizes and use rigorous research designs and statistical analyses appropriate for examining between‐group differences.

Plain language summary

Treatment for apathy in people with traumatic brain injury

Many people who have a traumatic brain injury experience apathy. Apathy is a decrease in cognitive, behavioural and emotional components of goal‐directed activity due to reduced motivation. It is characterised by lessened activity, initiative and concern about working towards and achieving goals. This problem impacts on rehabilitation outcome, independence, work and family burden.

The review authors searched the literature for treatment studies of apathy, or a component of apathy, in people who have had a traumatic brain injury. One randomised controlled trial was found which examined the use of cranial electrotherapy stimulation for inertia, which is a component of apathy. Evidence for the effectiveness of this treatment is particularly restricted by the small number of participants and the lack of statistical analyses to demonstrate that the cranial electrotherapy stimulation treatment was more successful than sham or no treatment. More methodologically rigorous studies need to be conducted to investigate different methods of effectively treating apathy in people with traumatic brain injury.

Background

Description of the condition

Apathy is one of the disorders of diminished motivation (Marin 2005) and is defined as a deficiency in overt behavioural, emotional and cognitive components of goal‐directed behaviour (Marin 1996). This includes deficits in one or all components leading to a goal. Elements of goal‐directed behaviour include: a) creation of an intention, b) formation of a plan, c) organisation of behaviour, d) programme of action, including initiation and sustaining activity, e) inspection of performance, f) regulation of behaviour to match the plan, and g) verification of conscious activity and results (Luria 1973).

Clinically, the essential feature of apathy is a decrease in goal‐directed activity due to reduced motivation (Marin 1996). It sits on the continuum of disorders of decreased motivation, with apathy at the end of lesser severity, ranging through abulia (poverty of behaviour and speech) (Marin 2005b) to akinetic mutism (total absence of speech or movement in the presence of visual tracking) (American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine 1995) at the most severe end. Apathy is distinguished from abulia by degree of impairment. Apathy is characterised by impaired initiation, activity and diminished concern, generally with intact communication (Marin 2005). Abulia is characterised by lack of initiation, self‐regulation of purposeful behaviour and concern, in conjunction with severely impaired ability to communicate (Marin 1990). Apathy is also distinguished from other causes of decreases in goal‐directed activity, including diminished level of consciousness, severe intellectual impairment or emotional distress (Marin 1990) such as depression (Levy 1998). Apathy can be considered as a syndrome consisting of impaired goal‐directed behaviour, cognition and emotion, or divided into elements of apathy, such as diminished initiative, time spent in activities or flat affect.

Apathy is a common occurrence after neurological damage. Following traumatic brain injury (TBI) it is reported in 71% of individuals (Kant 1998). The impact of apathy is widespread, hampering physical rehabilitation, coping skills (Finset 2000), vocational outcome, independence in the home (Prigatano 1992), and increasing family burden (Marsh 1998).

Description of the intervention

Interventions utilised in the rehabilitation of apathy range from pharmacological to psychological therapy. Pharmacological interventions for apathy often involve treating participants with dopamine agonists (Kant 2002). There are reports suggesting that acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (Tenovuo 2005) and psychostimulants (Deb 2004; Newburn 2005) are also effective in the pharmacological treatment of apathy.

Psychological interventions generally incorporate behavioural or cognitive rehabilitation strategies, or both. They may utilise techniques found in problem solving therapy (for example, von Cramon 1991). Problem solving therapy incorporates strategies to assist with goal‐directed activity, such as planning of stages, and executing and monitoring of activity (Crepeau 1997). Cognitive interventions, such as external compensation via checklists and paging systems have been shown to increase initiation towards goal‐directed activity (Evans 1998).

Behavioural therapies have also been observed to reduce apathy. For example, activity therapy (Politis 2004), multisensory environments (Baker 2001) and music therapy (Purdie 1997) have been shown to reduce apathy in neurological populations. Goal‐setting therapy is another type of behavioural intervention that can assist in the rehabilitation of apathy. By definition this type of therapy aims to improve goal‐directed activity. This technique is commonly used in rehabilitation centres because it allows treatment to be targeted to individual needs and success to be easily measured (Wilson 2002). McMillan 1999 describes the process of goal‐setting in a neurological population where 78% of their sample achieved long‐term goals, indicating goal‐directed activity was successfully accomplished.

Why it is important to do this review

Given that apathy is so common following TBI, with widespread functional consequences, it is important to evaluate the effectiveness of the interventions available. To the best of our knowledge there is no published systematic review examining interventions for apathy after TBI.

Objectives

The primary objective of this review was to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions for apathy following TBI. Interventions for apathy were compared to no intervention. A secondary objective was to compare different types of interventions, such as pharmacological and psychological, to establish the most effective method for decreasing apathy. Additionally, the occurrence of adverse events was investigated to assist practitioners in making informed choices about interventions used.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) examining an intervention for apathy in patients with TBI.

Types of participants

This review included trials of participants of either sex who sustained a TBI after the age of five years. People who sustained a TBI before age five were excluded due to the confound of brain maturation issues.

A TBI is defined as a physiological disruption to normal brain function that has been caused by a traumatic event (such as a blow to the head or a sudden acceleration/deceleration movement). This disruption must result in at least one of the following: a) loss of consciousness, b) alteration of mental state at the time of the injury, c) loss of memory immediately before or after the impact, or d) focal neurological deficits that may or may not be transient (Kay 1993). All degrees of severity of injury were included, as defined by length of post‐traumatic amnesia, Glasgow Coma Scale score, medical imaging or other standard measure of severity.

This review included trials that investigated interventions targeting apathy. Trials were excluded if the deficit was not the result of the TBI, and thus apathy occurred because of depression, dementia, delirium, stroke or other health conditions were not included. If the trial consisted of a mixed brain injury population, it was included if data for the TBI group were reported separately.

Types of interventions

Any type of intervention aimed at treating apathy was included. Interventions may have included any psychological, pharmacological or physical therapy. There was no restriction on duration or frequency of intervention. Studies focusing on apathy or any element(s) of apathy were included (for example, cognitive, behavioural or emotional components). We included studies that included individuals who were concurrently taking medications for medical and psychological illnesses (for example, antidepressant or antiepileptic drugs). If and when more studies are identified in the future, types of interventions will be compared against each other and no intervention.

Types of outcome measures

Types of outcome measures included in this review were neuropsychological tests, psychological tests, behavioural observation, self or observer report, psychological rating scales and questionnaires.

Primary outcome measures

The primary outcome measures were measures of behavioural, emotional and cognitive components of apathy. Behavioural components of apathy refer to the person’s engagement and performance in activities. Measures assess the following: activity, activity level, responsiveness to stimuli, effort and level of engagement in a given activity, productivity, appropriate cessation of activity and social withdrawal. Cognitive components investigated for change include initiation, ability to sustain behaviour, ability to stay on task and ability to generate material. Emotional components that were investigated for change include indifference, lack of concern and flattened affect.

Secondary outcome measures

Outcome measures of everyday functioning, participation levels (in community settings, rehabilitation settings, activities of daily living and other activities such as hobbies), psychosocial functioning, general aspects of cognition, general aspects of mood and affect, treatment compliance and service usage.

Adverse outcomes

Adverse events were recorded and classified as increased psychological distress, physical adverse outcomes (such as side effects of medication and medical difficulties resulting from increased activity) and other.

Search methods for identification of studies

Searches were not restricted by date, language or publication status and were formulated to include the following concepts:

traumatic brain injuries;

apathy;

interventions;

randomised controlled trials

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic bibliographic databases:

Cochrane Injuries Group's Specialised Register (to Jan 2009);

CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library 2008, issue 1);

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (to Issue 1, 2008);

ACP Journal Club (to Issue 1, 2008);

MEDLINE (1950 to January (week 4) 2008);

EMBASE (1980 to January 2008 (Week 4));

PsycINFO (1806 to January 2008 (Week 5));

CINAHL (1982 to January 2008);

PsycBITE (to January 2008);

AMED (1985 to January 2008);

www.controlled‐trials.com (to January 2008);

www.clinicaltrials.gov (to January 2008);

www.actr.org.au (to January 2008).

The search strategies are listed in full in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We searched reference lists of included articles and proceedings of key conferences for any further studies that met the inclusion criteria. We searched the abstracts of the World Congress for NeuroRehabilitation and the Symposium on Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. We contacted researchers who have already conducted trials in this area to identify any published, unpublished or ongoing trials.

Trials that were reported only as abstracts were eligible if sufficient information was available from the report.

Data collection and analysis

ALB and RLT independently screened all identified search results for eligibility, assessed methodological quality and extracted data. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus discussion.

Selection of studies

We screened search results by reviewing titles and abstracts of all citations to assess whether they met the criteria for inclusion. If there was not enough information in the title and abstract, we obtained full text copies of the article. Where the trial was not written in English a colleague from our institute who is fluent in the language of publication assessed eligibility, rated the quality and extracted the data for the trial (where necessary). Where there was not a colleague fluent in the language, we obtained a translation through the Cochrane Collaboration. In case of doubt or disagreement, we held discussions to reach a consensus. We tracked all identified studies using an electronic reference management system (EndNote).

Data extraction and management

The two authors extracted data from trials and compared results. If there was doubt or disagreement, we held discussions to reach consensus. Extraction was assisted by a form designed for this review. In the case of missing information in trials, we made attempts to contact the original investigators.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Initially, the two authors assessed the studies independently for methodological quality using the PEDro rating scale (Maher 2003). This rating scale was developed specifically for the assessment of RCTs for physical therapy and has since been used to assess psychological interventions (Tate 2004). It comprises 11 items as follows:

participant eligibility criteria and source specified;

random allocation of participants to interventions;

allocation concealed;

intervention groups similar at baseline regarding key outcome measures and important prognostic indicators;

blinding of all subjects;

blinding of all therapists administering the intervention;

blinding of all assessors who measure at least one key outcome;

drop‐outs (attrition bias);

intention‐to‐treat analysis;

reporting between group statistical comparisons;

reporting of measures of variability.

Each item was evaluated and totaled to give a total score out of 10 (items 2 to 11).

We then translated these ratings into the Cochrane Collaboration's graphical representation of risk of bias (Higgins 2008).

Measures of treatment effect

As anticipated, outcome measures were continuous. Because of the small number of measures used it was not possible to calculate the weighted mean difference and the 95% confidence interval (CI), or the standardised mean difference and 95% CI.

Dealing with missing data

We made attempts to contact the trial investigators in the case of missing data. Had this not been possible, we would have performed variable case analysis if feasible.

Data synthesis

We would have performed a meta‐analysis had there been enough trials present that were clinically homogenous (for example, all pharmacological interventions). If the trials were statistically homogenous, we would have utilised the fixed‐effect method. If the trials were statistically heterogenous, we would have utilised the random‐effects method or not pooled results. Statistical analysis was to be performed using Review Manager 5. However, because the data were not suited to meta‐analysis, results were discussed in a descriptive format.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

It was anticipated that there would be considerable clinical heterogeneity, given that the type of interventions targeting apathy ranges from psychological to pharmacological. In the case of greater numbers of trials being found in the future, the authors will assess the type of intervention used and group the studies accordingly. In the case of a number of clinically homogenous trials, statistical heterogeneity will be assessed through the Chi2 test and the I2 statistic (Higgins 2002).

Had the data been more suited to meta‐analysis (including being clinically homogenous), we would have examined the data for statistical heterogeneity. Trials would be considered statistically heterogenous if the I2 statistic was over 50% (Higgins 2005).

Subgroup analysis will be performed in the case of a number of studies being located in the future that could be clustered according to one of the following groupings:

injury severity;

age (for example, adults versus children);

time post‐injury (for example, acute versus long‐term);

type of intervention (for example, pharmacological versus psychological).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

We conducted the most current search of electronic databases in January 2008. This search yielded a total of 1251 references. One trial was identified that met the inclusion criteria. Investigations into other identified sources of references yielded zero trials that met the inclusion criteria.

Included studies

The included study (Smith 1994) is a randomised controlled trial (RCT) examining cranial electrotherapy stimulation (CES) for males with traumatic closed head injuries living in a sheltered living facility. CES treatment (N = 10) was compared to a sham treatment control (N = 5) and a no treatment control (N = 6). The primary outcome measure was the Profile of Mood States (POMS). The five factors of the POMS were measured as follows: fatigue/inertia, tension/anxiety, depression/dejection, anger/hostility and confusion/bewilderment. This study met the criteria for inclusion because it measured the effect of treatment on inertia, a behavioural element of apathy. For further information see the 'Characteristics of included studies' table.

Excluded studies

An additional 20 trials addressing interventions for apathy were identified but were not included in this review because they were either not RCTs or were not conducted in a traumatic brain injury (TBI) population (see the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table). Of these, 15 investigated pharmacological interventions, 10 were conducted within the dementia population, three in the TBI population and two in mixed brain injury populations. Five studies investigated non‐pharmacological interventions alone.

Risk of bias in included studies

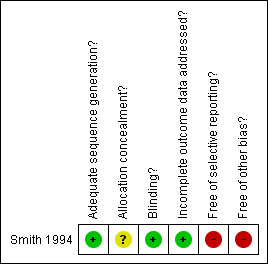

Two authors rated the methodological quality of the study independently using the PEDro scale (Maher 2003). The kappa coefficient between the two raters for the PEDro item scores was 0.79 (P < 0.01). Individual item scores can be found in Table 1. Overall, the Smith 1994 study received a total score of 6/10. Graphical representations of the risk of bias in the included study can be viewed in Figure 1.

1. Methodological quality of included studies on the PEDro scale.

| Criterion | Smith 1994 |

| 1. Eligibility criteria were specified | Yes |

| 2. Participants randomly allocated to interventions | Yes |

| 3. Allocation was concealed | No |

| 4. Intervention groups were similar at baseline regarding key outcome measure(s) and most important prognostic indicators | No |

| 5. There was blinding of all participants | Yes |

| 6. There was blinding of all therapists | Yes |

| 7. There was blinding of all assessors who measured at least 1 key outcome | Yes |

| 8. Measures of at least 1 key outcome were obtained from more than 85% of the participants initially allocated to groups | Yes |

| 9. All participants for whom outcome measures were available received the treatment of control condition as allocated or, where this was not the case, data for at least 1 key outcome was analysed by ‘intention‐to‐treat’ | No |

| 10. The results of between‐intervention group statistical comparisons are reported for at least 1 key outcome | No |

| 11. The study provides both point measures and measures of variability for at least 1 key outcome | Yes |

| TOTAL (Items 2‐11) | 6/10 |

1.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

There was no mention within the Smith 1994 article of allocation to group being concealed, indicating an area of potential bias.

Blinding

Blinding of participants, therapists and assessors measuring the key outcome measure was used in the Smith 1994 trial.

Incomplete outcome data

Reported outcome data for the Smith 1994 study were complete.

Selective reporting

No between‐intervention group statistical comparisons were reported within the Smith 1994 trial.

Other potential sources of bias

The Smith 1994 paper had two other potential sources of bias. There were no analyses reported which established that the intervention groups were similar at baseline. There was also no indication that participants received the treatment to which they were allocated or that any of the key outcomes were analysed by ‘intention‐to‐treat’.

Effects of interventions

Given that there was only one included study, a meta‐analysis was not possible. Between‐group statistical analysis was not reported in this study. We made attempts to contact the corresponding author, unfortunately without success.

This study sought an alternative to pharmacological treatment and therefore examined cranial electrotherapy stimulation (CES). CES was investigated as a method of intervention for closed‐head injury patients residing in a sheltered living facility. Participants were randomised into three groups: CES, a sham treatment control and a no treatment control. Statistical analysis to investigate similarity between groups at baseline was not reported. Post‐treatment results indicated that the CES group showed a statistically significant improvement in all five factors of the Profile of Mood States (POMS), including fatigue/inertia. The fatigue/inertia domain scale reported a mean decrease from 7.44 to 5.33 (see Table 2). No statistically significant changes were found in either the sham treatment or no treatment control groups. Given that between‐group statistical analysis was not reported, it was not possible to determine if the CES group improved significantly more than the control groups. A follow‐up assessment was not conducted, so evidence for maintenance of improvements is unknown. Number of seizures, a possible adverse event, was recorded during treatment. There was no increase in seizure numbers due to CES. No other adverse events were reported.

2. Characteristics of CES and control groups (Smith 1994).

| Group | CES | Sham treatment control | No treatment control |

| Number of participants | 10 | 5 | 6 |

| Sex | 10 males | 5 males | 6 males |

| Pre‐treatment POMS fatigue/inertia score ‐ mean (SD) | 7.44 (6.75) | 9.46 (7.83) | 8.17 (7.41) |

CES = cranial electrotherapy stimulation

Discussion

Summary of main results

The aim of this review was to identify and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions for apathy following a traumatic brain injury (TBI). Only one trial met the criteria for inclusion: the Smith 1994 trial, therefore data could not be pooled for further analysis or interpretation. The Smith 1994 article described results supporting decreases over time in inertia, an element of apathy, with cranial electrotherapy stimulation (CES) treatment. Sham treatment and no treatment control groups did not show improvements in inertia over time. Given that the study did not report results of between‐group statistical analyses, it was not possible to ascertain if the CES group improved significantly more than the control groups. Thus, whether CES treatment improves inertia more than the control treatments is unknown.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Given that only one trial met criteria for this review, there is not robust evidence on which to base practice. This strongly suggests a need for further methodologically rigorous investigations. In the meantime, additional ideas about treatment options could be gained from reviewing trials that investigated interventions for apathy, but did not meet the criteria for this review. A number of trials were found that reported treatments for apathy, or an element of apathy, in the human neurological population. However, they were excluded because they either considered neurological populations other than the TBI population or were not a randomised controlled trial (RCT). These 20 excluded studies are listed in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table. Half of these papers were studies of pharmacological interventions treating components of apathy in the dementia population. There were few studies that treated apathy as a syndrome, instead these trials treated an element of apathy. Only one non‐pharmacological randomised controlled trial treated the apathy syndrome (Politis 2004). This trial examined a kit‐based activity intervention compared to a time and attention control and found both therapies significantly decreased apathy in the dementia population. In the TBI population there was only one trial that treated the syndrome of apathy rather than a component of apathy (Newburn 2005). This series of case studies examined the effect of selegiline, a dopamine agent, on the apathy syndrome.

In order to review the applicability of the evidence included in this review, we considered the sample size and clinical characteristics of the participants. The sample size was small, with only 21 participants over three groups. This suggests that the study may not have adequate power. Although all participants were said to have sustained a closed head injury, the report indicated a number of additional injuries such as gas poisoning and cerebral carcinoma. Findings of this review must be viewed in light of, inter alia, the small size and heterogenous characteristics of the sample.

When assessing the evidence, variability within the literature about the term apathy should be considered. First, there is a lack of consistency in the use of terminology in the literature. Some papers use the term apathy (e.g. Politis 2004), whilst others describe motivational deficits (Powell 1996) or an amotivational syndrome (van Reekum 1995). Second, there is diversity in how apathy has been operationally defined in different trials. Marin 1991 defined an apathy syndrome that can be used to operationalise apathy. However, apathy is still described in a number of different ways. For example, it has been operationalised as engagement (Fitzsimmons 2003) or lack of self‐initiated action (Stuss 2000). In order to compare treatments and their applicability accurately, standardised terminology and one operational definition is required.

When considering trials of treatments of apathy, difficulties in assessment should be taken into account. Particular difficulties apply to differential diagnosis through assessment. For example, although efforts have been made to develop a psychometrically sound measurement instrument that differentiates apathy from depression (Marin 1991b), other authors argue that within the TBI population this distinction is not always possible (Glenn 2002). Assessment of apathy is further complicated by use of a number of omnibus measures that assess apathy along with a number of other physiological, cognitive and psychological factors, such as fatigue, disinhibition and depressed mood.

Quality of the evidence

The included trial (Smith 1994) is of moderate methodological quality, according to the PEDro scale. This indicates that the trial has taken measures to decrease bias. Furthermore, this trial was awarded PEDro points for items that are traditionally difficult to achieve for a non‐pharmacological study (Perdices 2006). Namely, both participants and therapists remained blind to treatment group.

However, notwithstanding the moderate PEDro score, there are problems with the interpretation of the results because between‐group statistical analyses were not reported. Thus, it is not possible to determine if the treatment group improved more than the control groups; it is only possible to ascertain whether the groups improved over time. Analyses were not undertaken to establish if the groups were similar at baseline, making it difficult to decipher whether changes after treatment were due to treatment effects, or if they were due to pre‐treatment group differences. Furthermore, the authors did not state if allocation was concealed or whether participants received the treatment as allocated. An additional potential confound was that inertia was measured in the same variable as fatigue. Thus, the findings of this review must be viewed in light of the potential areas of confound and bias.

Potential biases in the review process

To the best of the authors' knowledge, there are no potential biases in the review process.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

As far as the authors are aware, there is not another systematic review on interventions for apathy. However, there are non‐systematic reviews of treatment options available for apathy (e.g. Marin 2005b; Roth 2007). The use of CES treatment is not mentioned within this literature. Treatments described include both pharmacological and psychological methods. Pharmacological methods reported include dopamine agonists and acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. The psychological methods discussed encompass behavioural interventions, cognitive rehabilitation and the use of external compensation.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

This review does not provide support for the effectiveness of cranial electrotherapy stimulation (CES) in the treatment of inertia, which is an element of apathy. This conclusion is based on a single trial with a small sample size (N = 21), which did not report results of between‐group statistical analyses. More research is needed using larger sample sizes, and reporting between‐group statistical analyses, to confirm these findings.

Implications for research.

The limited number of trials included in this review indicates that more controlled trials are required in this area. To allow for meta‐analysis and pooling of data in the future, it is necessary for interventions to use either a standardised operational definition of apathy or treat comparable elements of apathy. This review indicates that this is an area of research which has not been examined with methodologically rigorous techniques. Despite the moderate number of trials examining treatments for apathy (see the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table) there were no randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in the traumatic brain injury (TBI) population examining treatment of the apathy syndrome, and only one trial investigating an element of apathy. Additional RCTs are needed, particularly considering the treatment of the apathy syndrome.

The included study must be viewed in the light of its small sample size. Future studies should aim to have larger numbers of participants. Finally, it would be useful to evaluate different types of treatment for the apathy syndrome.

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2007 Review first published: Issue 2, 2009

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 23 May 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

The Rehabilitation Studies Unit, University of Sydney and Royal Rehabilitation Centre Sydney supported this review. The Northern Medical Research Foundation, Northern Clinical School, University of Sydney and the Australian Government assisted in funding this review. We thank the Cochrane Injuries Group for their assistance throughout the review process.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy

Cochrane Injuries Group Specialised Register (searched 16 January 2009)

“Behavior Therapy” or “Occupational Therapy” or “Physical Therapy Modalities” or “art therapy” or “music therapy” or “Complementary Therapies” or “Drug Therapy” or “Dopamine Agents” or “Central Nervous System Stimulants” or “Central Nervous System Agents” or “cognitive behavior therapy” or “cognitive behaviour therapy” or CBT or "cognitive rehabilitation" or neurorehabilitation or "speech pathology" or psychostimulant* or "stimulant treatment" or “complementary medicine” or “complementary therapy” or “complementary treatment” or “alternative medicine or alternative therapy” or “alternative treatment*” or "problem solving" or Amphetamine or Bemegride or Benzphetamine or Caffeine or Dextroamphetamine or Doxapram, or Ephedrine or Harmaline or Mazindol or Methamphetamine or Methylphenidate or Nikethamide or Pemoline or Phenmetrazine or Phentermine or Picrotoxin or bromocriptine or selegiline or Amantadine or Amphetamine or Benserazide or Benzphetamine or Carbidopa or Dextroamphetamine or Dihydroxyphenylalanine or Dopamine or Fusaric Acid or Levodopa or Memantine or Methamphetamine or Methylphenidate

(((head or crani* or cerebr* or capitis or brain* or forebrain* or skull* or hemispher* or intra‐cran* or inter‐cran*) AND (injur* or trauma* or damag* or wound* or fracture* or contusion*)) OR ((head or crani* or cerebr* or brain* or intra‐cran* or inter‐cran*) AND (haematoma* or hematoma* or haemorrhag* or hemorrhag* or bleed* or pressure))) AND (attitude or initiation or persistence or generativity or apathy or motivation or goal* or intention or drive* or persever* or anergia or indifference or drive or inertia or “frontal lobe impairment”)

1 AND 2

AMED (searched 31st January, 2008)

1. Brain injuries/ 2. Head injuries/ 3. Brain concussion/ 4. Unconsciousness/ 5. Cerebral hemorrhage/ 6. "glascow coma scale$".ab,ti. 7. (unconscious$ or coma$ or concuss$ or 'persistent vegetative state').ab,ti. 8. "ranchos los amigos scale".ab,ti. 9. ((head or crani$ or cerebr$ or brain$ or intracran$ or intercran$) adj3 (h$ematoma$ or hemorrhag$ or bleed$ or pressure)).ab,ti. 10. or/1‐9 11. Motivation/ 12. Goals/ 13. Attitude/ 14. (initiation or persistence or generativity or apathy or motivation or goal$ or intention or persever$ or anergia or indifference or inertia or frontal lobe impairment).ab,ti. 15. or/11‐14 16. Cognitive therapy/ or Behavior therapy/ 17. Therapy/ 18. Rehabilitation/ 19. Program evaluation/ 20. Treatment outcome/ 21. Occupational therapy/ 22. Physiotherapy/ 23. Art therapy/ 24. Music therapy/ 25. Speech therapy/ 26. Language therapy/ 27. Complementary medicine/ 28. Complementary therapies/ 29. Drug therapy/ 30. (((cognitive or behavio$r) adj1 therapy) or CBT or "cognitive rehabilitation" or neurorehabilitation).ab,ti. 31. "speech pathology".ab,ti. 32. (central nervous system adj1 (agent$ or stimulant$)).ab,ti. 33. (psychostimulant$ or "stimulant treatment").ab,ti. 34. ((complementary or alternative) adj1 (medicine or therap$ or treatment$)).ab,ti. 35. ((physical or executive or physiotherapy or psychological or occupational or speech or "problem solving" or plan$ or music or art) adj1 (training or treatment or rehab$ or remed$ or program$ or intervention$ or therap$ or approach or technique$ or modification or strateg$ or manag$)).ab,ti. 36. (amphetamine or bemegride or benzphetamine or caffeine or dextramphetamine or doxapram or ephedrine or harmaline or mazindol or methamphetamine or methylphenidate or nikethamide or pemoline or phenmetrazine or phentermine or picrotoxin or bromocriptine or selegine or amantadine or amphetamine or benserazide or benzphetamine or carbidopa or dextramphetamine or dihydroxyphenylalanine or dopamine or fusaric acid or levodopa or memantine).ab,ti. 37. or/16‐36 38. 10 and 15 39. 37 and 38 40. Clinical trials/ 41. Randomized controlled trials/ 42. Placebos/ 43. Double blind method/ 44. random$.ab,ti. 45. ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj3 (blind$ or dummy or mask$)).ab,ti. 46. placebo$.ab,ti. 47. crossover.ab,ti. 48. assign$.ab,ti. 49. allocat$.ab,ti. 50. ((clin$ or control$ or compar$ or evaluat$ or prospectiv$) adj3 (trial$ or studi$ or study)).ab,ti. 51. trial.ab,ti. 52. or/40‐51 53. humans/ 54. Animals/ 55. 54 not (53 and 54) 56. 52 not 55 57. 39 and 56

CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library 2008, Issue 1)

#1MeSH descriptor Craniocerebral Trauma explode all trees #2 MeSH descriptor Cerebrovascular Trauma explode all trees #3 MeSH descriptor Brain Edema explode all trees #4 (head or crani* or cerebr* or capitis or brain* or forebrain* or skull* or hemispher* or intra‐cran* or inter‐cran*) near3 (injur* or trauma* or damag* or wound* or fracture* or contusion*):ti or (head or crani* or cerebr* or capitis or brain* or forebrain* or skull* or hemispher* or intra‐cran* or inter‐cran*) near3 (injur* or trauma* or damag* or wound* or fracture* or contusion*):ab #5 (Diffuse axonal injur*):ti or (Diffuse axonal injur*):ab #6 (head or crani* or cerebr* or brain* or intra‐cran* or inter‐cran*) near3 (haematoma* or hematoma* or haemorrhag* or hemorrhag* or bleed* or pressure):ti or (head or crani* or cerebr* or brain* or intra‐cran* or inter‐cran*) near3 (haematoma* or hematoma* or haemorrhag* or hemorrhag* or bleed* or pressure):ab #7 MeSH descriptor Glasgow Coma Scale explode all trees #8 MeSH descriptor Glasgow Outcome Scale explode all trees #9 MeSH descriptor Unconsciousness explode all trees #10 "Glasgow coma scale" or "Glasgow outcome scale" or "Glasgow outcome score":ti or "Glasgow coma scale" or "Glasgow outcome scale" or "Glasgow outcome score":ab #11 (Unconscious* or coma* or concuss* or 'persistent vegetative state'):ti or (Unconscious* or coma* or concuss* or 'persistent vegetative state'):ab #12 "Rancho Los Amigos Scale":ti or "Rancho Los Amigos Scale":ab #13 (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12) #14 MeSH descriptor Motivation explode all trees #15 MeSH descriptor Drive explode all trees #16 MeSH descriptor Goals explode all trees #17 MeSH descriptor Intention explode all trees #18 MeSH descriptor Attitude explode all trees #19 (initiation or persistence or generativity or apathy or motivation or goal* or intention or persever* or anergia or indifference or drive or inertia or "frontal lobe impairment"):ti or (initiation or persistence or generativity or apathy or motivation or goal* or intention or persever* or anergia or indifference or drive or inertia or "frontal lobe impairment"):ab #20 (#14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19) #21 (#13 AND #20) #22 MeSH descriptor Behavior Therapy explode all trees #23 MeSH descriptor Central Nervous System Stimulants explode all trees #24 MeSH descriptor Central Nervous System Agents explode all trees #25 MeSH descriptor Dopamine Agents explode all trees #26 MeSH descriptor Physical Therapy Modalities explode all trees #27 MeSH descriptor Art Therapy explode all trees #28 MeSH descriptor Music Therapy explode all trees #29 MeSH descriptor Complementary Therapies explode all trees #30 MeSH descriptor Drug Therapy explode all trees #31 MeSH descriptor Occupational Therapy explode all trees #32 "cognitive or behavior therapy" or "cognitive or behaviour therapy" or CBT or "cognitive rehabilitation" or neurorehabilitation:ti or "cognitive or behavior therapy" or "cognitive or behaviour therapy" or CBT or "cognitive rehabilitation" or neurorehabilitation:ab #33 "speech pathology":ti or "speech pathology":ab #34 "central nervous system" next (agent* or stimulant*):ti or "central nervous system" next (agent* or stimulant*):ab #35 (psychostimulant* or "stimulant treatment"):ti or (psychostimulant* or "stimulant treatment"):ab #36 (complementary or alternative) next (medicine or therap* or treatment*):ti or (complementary or alternative) next (medicine or therap* or treatment*):ab #37 (Physical or executive or physiotherapy or psychological or occupational or speech or "problem solving" or plan* or music or art) next (training or treatment or rehab* or remed* or program* or intervention* or therap* or approach or technique* or modification or strateg* or manag*):ti or (Physical or executive or physiotherapy or psychological or occupational or speech or "problem solving" or plan* or music or art) next (training or treatment or rehab* or remed* or program* or intervention* or therap* or approach or technique* or modification or strateg* or manag*):ab #38 Amphetamine or Bemegride or Benzphetamine or Caffeine or Dextroamphetamine or Doxapram or Ephedrine or Harmaline or Mazindol or Methamphetamine or Methylphenidate or Nikethamide or Pemoline or Phenmetrazine or Phentermine or Picrotoxin or bromocriptine or selegiline or Amantadine or Amphetamine or Benserazide or Benzphetamine or Carbidopa or Dextroamphetamine or Dihydroxyphenylalanine or Dopamine or Fusaric Acid or Levodopa or Memantine or Methamphetamine or Methylphenidate #39 (#22 OR #23 OR #24 OR #25 OR #26 OR #27 OR #28 OR #29 OR #30 OR #31 OR #32 OR #33 OR #34 OR #35 OR #36 OR #37 OR #38) #40 (#21 AND #39)

CINAHL (searched 31st January, 2008)

1. exp Brain Concussion/ or exp Brain Injuries/ 2. exp Head Injuries/ 3. exp Cerebral Hemorrhage/ or exp Subarachnoid Hemorrhage/ 4. exp Intracranial Hemorrhage/ 5. exp Brain Damage, Chronic/ 6. exp UNCONSCIOUSNESS/ 7. exp Glasgow Coma Scale/ 8. "glascow coma scale$".ab,ti. 9. (unconscious$ or coma$ or concuss$ or 'persistent vegetative state').ab,ti. 10. "Ranchos Los Amigos Scale".ab,ti. 11. ((head or crani$ or cerebr$ or brain$ or intracran$ or intercran$) adj3 (h$ematoma$ or h$emorrhag$ or bleed$ or pressure)).ab,ti. 12. or/1‐11 13. exp Motivation/ 14. exp Goal‐Setting/ 15. exp "Goals and Objectives"/ 16. exp DRIVE/ 17. exp INTENTION/ 18. exp ATTITUDE/ 19. (initiation or persistence or generativity or apathy or motivation or goal$ or intention or persever$ or anergia or indifference or inertia or frontal lobe impairment).ab,ti. 20. or/13‐19 21. exp Behavior Therapy/ 22. exp Cognitive Therapy/ 23. exp SPEECH THERAPY/ or exp RECREATIONAL THERAPY/ or exp PHYSICAL THERAPY/ or exp OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY/ or exp MUSIC THERAPY/ or exp DRUG THERAPY/ 24. exp REHABILITATION/ or exp REHABILITATION, COGNITIVE/ 25. exp Program Evaluation/ 26. exp Treatment Outcomes/ 27. exp Intervention Trials/ 28. exp Central Nervous System Stimulants/ 29. exp Central Nervous System Agents/ 30. exp Art Therapy/ 31. exp Alternative Therapies/ 32. (((cognitive or behavio$r) adj1 therapy) or CBT or "cognitive rehabilitation" or neurorehabilitation).ab,ti. 33. "speech pathology".ab,ti. 34. (central nervous system adj1 (agent$ or stimulant$)).ab,ti. 35. (psychostimulant$ or "stimulant treatment").ab,ti. 36. ((complementary or alternative) adj1 (medicine or therap$ or treatment$)).ab,ti. 37. ((physical or executive or physiotherapy or psychological or occupational or speech or "problem solving" or plan$ or music or art) adj1 (training or treatment or rehab$ or remed$ or program$ or intervention$ or therap$ or approach or technique$ or modification or strateg$ or manag$)).ab,ti. 38. (amphetamine or bemegride or benzphetamine or caffeine or dextramphetamine or doxapram or ephedrine or harmaline or mazindol or methamphetamine or methylphenidate or nikethamide or pemoline or phenmetrazine or phentermine or picrotoxin or bromocriptine or selegine or amantadine or amphetamine or benserazide or benzphetamine or carbidopa or dextramphetamine or dihydroxyphenylalanine or dopamine or fusaric acid or levodopa or memantine).ab,ti. 39. or/21‐38 40. 12 and 20 41. 39 and 40 42. clinical trial.pt. 43. randomized.ti,ab. 44. placebo.ti,ab. 45. drug therapy.fs. 46. randomly.ti,ab. 47. trial.ti,ab. 48. groups.ti,ab. 49. or/42‐48 50. 41 and 49

All databases (The Cochrane Library 2008, Issue 1)

1. "craniocerebral trauma".ab,ti. 2. "cerebrovascular trauma".ab,ti. 3. "brain edema".ab,ti. 4. "glasgow coma scale".ab,ti. 5. "glasgow outcome scale".ab,ti. 6. "Glasgow coma scale$".ab,ti. 7. (Unconscious$ or coma$ or concuss$ or 'persistent vegetative state').ab,ti. 8. "Rancho Los Amigos Scale".ab,ti. 9. ((head or crani$ or cerebr$ or capitis or brain$ or forebrain$ or skull$ or hemispher$ or intra‐cran$ or inter‐cran$) adj3 (injur$ or trauma$ or damag$ or wound$ or fracture$ or contusion$)).ab,ti. 10. "Diffuse axonal injur$".ab,ti. 11. ((head or crani$ or cerebr$ or brain$ or intra‐cran$ or inter‐cran$) adj3 (haematoma$ or hematoma$ or haemorrhag$ or hemorrhag$ or bleed$ or pressure)).ab,ti. 12. or/1‐11 13. (initiation or persistence or generativity or apathy or motivation or goal$ or intention or persever$ or anergia or indifference or drive or inertia or frontal lobe impairment).ab,ti. 14. 12 and 13 15. (((cognitive or behavio?r$) adj1 therapy) or CBT or "cognitive rehabilitation" or neurorehabilitation).ab,ti. 16. "speech pathology".ab,ti. 17. (central nervous system adj1 (agent$ or stimulant$)).ab,ti. 18. (psychostimulant$ or "stimulant treatment").ab,ti. 19. ((complementary or alternative) adj1 (medicine or therap$ or treatment$)).ab,ti. 20. ((physical or executive or physiotherapy or psychological or occupational or speech or "problem solving" or plan$ or music or art) adj1 (training or treatment or rehab$ or remed$ or program$ or intervention$ or therap$ or approach or technique$ or modification or strateg$ or manag$)).ab,ti. 21. (amphetamine or bemegride or benzphetamine or caffeine or dextramphetamine or doxapram or ephedrine or harmaline or mazindol or methamphetamine or methylphenidate or nikethamide or pemoline or phenmetrazine or phentermine or picrotoxin or bromocriptine or selegine or amantadine or amphetamine or benserazide or benzphetamine or carbidopa or dextramphetamine or dihydroxyphenylalanine or dopamine or fusaric acid or levodopa or memantine).ab,ti. 22. or/15‐21 23. 14 and 22

EMBASE (searched 31st January, 2008)

1. exp Head Injury/ 2. exp Cerebrovascular Accident/ 3. exp Brain Edema/ 4. exp glasgow coma scale/ or exp glasgow outcome scale/ or exp rancho los amigos scale/ 5. "Glasgow coma scale".ab,ti. 6. "Glasgow outcome scale".ab,ti. 7. "Glasgow outcome score".ab,ti. 8. "Rancho Los Amigos Scale".ab,ti. 9. exp unconsciousness/ or exp coma/ 10. (Unconscious$ or coma$ or concuss$ or 'persistent vegetative state').ab,ti. 11. ((head or crani$ or cerebr$ or capitis or brain$ or forebrain$ or skull$ or hemispher$ or intra‐cran$ or inter‐cran$) adj3 (injur$ or trauma$ or damag$ or wound$ or fracture$ or contusion$)).ab,ti. 12. "Diffuse axonal injur$".ab,ti. 13. ((head or crani$ or cerebr$ or brain$ or intra‐cran$ or inter‐cran$) adj3 (haematoma$ or hematoma$ or haemorrhag$ or hemorrhag$ or bleed$ or pressure)).ab,ti. 14. or/4‐10 15. or/11‐13 16. 14 and 15 17. 1 or 2 or 3 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 16 18. exp motivation/ 19. exp drive/ 20. exp attitude to life/ 21. (initiation or persistence or generativity or apathy or motivation or goal$ or intention or persever$ or anergia or indifference or drive or inertia or frontal lobe impairment).ab,ti. 22. or/18‐21 23. 17 and 22 24. exp behavior therapy/ 25. exp occupational therapy/ 26. exp art therapy/ 27. exp music therapy/ 28. exp alternative medicine/ 29. exp drug therapy/ 30. exp Dopamine Receptor Stimulating Agent/ 31. exp Central Nervous System Agents/ 32. (((cognitive or behavio?r$) adj1 therapy) or CBT or "cognitive rehabilitation" or neurorehabilitation).ab,ti. 33. "speech pathology".ab,ti. 34. ("central nervous system" adj1 (agent$ or stimulant$)).ab,ti. 35. (psychostimulant$ or "stimulant treatment").ab,ti. 36. ((complementary or alternative) adj1 (medicine or therap$ or treatment$)).ab,ti. 37. ((Physical or executive or physiotherapy or psychological or occupational or speech or "problem solving" or plan$ or music or art) adj1 (training or treatment or rehab$ or remed$ or program$ or intervention$ or therap$ or approach or technique$ or modification or strateg$ or manag$)).ab,ti. 38. (Amphetamine or Bemegride or Benzphetamine or Caffeine or Dextroamphetamine or Doxapram, or Ephedrine or Harmaline or Mazindol or Methamphetamine or Methylphenidate or Nikethamide or Pemoline or Phenmetrazine or Phentermine or Picrotoxin or bromocriptine or selegiline or Amantadine or Amphetamine or Benserazide or Benzphetamine or Carbidopa or Dextroamphetamine or Dihydroxyphenylalanine or Dopamine or Fusaric Acid or Levodopa or Memantine or Methamphetamine or Methylphenidate).ab,ti. 39. or/24‐38 40. 23 and 39 41. exp clinical study/ 42. exp Clinical Trial/ 43. randomized.ab,ti. 44. placebo.ti,ab. 45. randomly.ab,ti. 46. trial.ab,ti. 47. groups.ti,ab. 48. 41 or 42 or 43 or 44 or 45 or 46 or 47 49. exp animal/ 50. exp human/ 51. 49 not (49 and 50) 52. 48 not 51 53. 40 and 52

MEDLINE (searched 31st January, 2008)

1. exp craniocerebral trauma/ 2. exp cerebrovascular trauma/ 3. exp brain edema/ 4. exp glasgow coma scale/ 5. exp glasgow outcome scale/ 6. exp unconsciousness/ 7. "Glasgow coma scale$".ab,ti. 8. (Unconscious$ or coma$ or concuss$ or 'persistent vegetative state').ab,ti. 9. "Rancho Los Amigos Scale".ab,ti. 10. ((head or crani$ or cerebr$ or capitis or brain$ or forebrain$ or skull$ or hemispher$ or intra‐cran$ or inter‐cran$) adj3 (injur$ or trauma$ or damag$ or wound$ or fracture$ or contusion$)).ab,ti. 11. "Diffuse axonal injur$".ab,ti. 12. ((head or crani$ or cerebr$ or brain$ or intra‐cran$ or inter‐cran$) adj3 (haematoma$ or hematoma$ or haemorrhag$ or hemorrhag$ or bleed$ or pressure)).ab,ti. 13. or/5‐12 14. exp motivation/ 15. exp drive/ 16. exp goals/ 17. exp intention/ 18. exp attitude/ 19. (initiation or persistence or generativity or apathy or motivation or goal$ or intention or persever$ or anergia or indifference or drive or inertia or frontal lobe impairment).ab,ti. 20. or/14‐19 21. 13 and 20 22. exp behavior therapy/ 23. exp occupational therapy/ 24. exp physical therapy modalities/ 25. exp art therapy/ 26. exp music therapy/ 27. exp complementary therapies/ 28. exp drug therapy/ 29. exp dopamine agents/ 30. exp central nervous system stimulants/ 31. exp central nervous system agents/ 32. (((cognitive or behavio?r$) adj1 therapy) or CBT or "cognitive rehabilitation" or neurorehabilitation).ab,ti. 33. "speech pathology".ab,ti. 34. ("central nervous system" adj1 (agent$ or stimulant$)).ab,ti. 35. (psychostimulant$ or "stimulant treatment").ab,ti. 36. ((complementary or alternative) adj1 (medicine or therap$ or treatment$)).ab,ti. 37. ((Physical or executive or physiotherapy or psychological or occupational or speech or "problem solving" or plan$ or music or art) adj1 (training or treatment or rehab$ or remed$ or program$ or intervention$ or therap$ or approach or technique$ or modification or strateg$ or manag$)).ab,ti. 38. (Amphetamine or Bemegride or Benzphetamine or Caffeine or Dextroamphetamine or Doxapram or Ephedrine or Harmaline or Mazindol or Methamphetamine or Methylphenidate or Nikethamide or Pemoline or Phenmetrazine or Phentermine or Picrotoxin or bromocriptine or selegiline or Amantadine or Amphetamine or Benserazide or Benzphetamine or Carbidopa or Dextroamphetamine or Dihydroxyphenylalanine or Dopamine or Fusaric Acid or Levodopa or Memantine or Methamphetamine or Methylphenidate).ab,ti. 39. or/22‐38 40. 21 and 39 41. clinical trial.pt. 42. randomized.ti,ab. 43. placebo.ti,ab. 44. drug therapy.fs. 45. randomly.ti,ab. 46. trial.ti,ab. 47. groups.ti,ab. 48. or/41‐47 49. exp animals/ 50. exp humans/ 51. 49 not (49 and 50) 52. 48 not 51 53. 40 and 52

National Research Register 2008, Issue 1

#1. MOTIVATION explode all trees (MeSH) #2. DRIVE explode all trees (MeSH) #3. GOALS explode all trees (MeSH) #4. INTENTION explode all trees (MeSH) #5. ATTITUDE explode all trees (MeSH) #6. (apathy or initiation or persistence or generativity or apathy or motivation or goal* or intention or persever* or anergia or indifference or drive or inertia or (frontal next lobe next impairment)) #7. (#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #6) #8. CRANIOCEREBRAL TRAUMA explode all trees (MeSH) #9. BRAIN EDEMA explode all trees (MeSH) #10. CEREBROVASCULAR TRAUMA explode all trees (MeSH) #11. (glasgow next coma next scale) #12. GLASGOW COMA SCALE explode all trees (MeSH) #13. GLASGOW OUTCOME SCALE explode all trees (MeSH) #14. ((glasgow next coma next scale) or (glasgow next outcome next scale) or (glasgow next outcome next score)) #15. ((head or crani* or cerebr* or capitis or brain* or forebrain* or skull* or hemispher* or intra‐cran* or inter‐cran*) and (injur* or trauma* or damag* or wound* or fracture* or contusion*)) #16. (diffuse next axonal next injur*) #17. ((head or crani* or cerebr* or brain* or intra‐cran* or inter‐cran*) and (haematoma* or hematoma* or haemorrhag* or hemorrhag* or bleed* or pressure)) #18. (#8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17) #19. (#7 and #18)

PsycBITE (searched 31st January, 2008)

Search 1

| Target area | Executive functioning deficits |

| Intervention | Not selected |

| Neurological group | Traumatic brain injury |

| Method | RCT |

| Age | Not selected |

Search 2

| Target area | Behaviour problems |

| Intervention | Not selected |

| Neurological group | Traumatic brain injury |

| Method | RCT |

| Age | Not selected |

PSYCINFO (searched 31st January, 2008)

1. exp Traumatic Brain Injury/ 2. exp Head Injuries/ 3. exp Brain Disorders/ 4. exp Brain Concussion/ 5. exp Cerebral Hemorrhage/ 6. consciousness disturbances/ 7. "glascow coma scale$".ab,ti. 8. (unconscious$ or coma$ or concuss$ or 'persistent vegetative state').ab,ti. 9. "Ranchos Los Amigos Scale".ab,ti. 10. ((head or crani$ or cerebr$ or brain$ or intracran$ or intercran$) adj3 (h$ematoma$ or h$emorrhag$ or bleed$ or pressure)).ab,ti. 11. or/1‐10 12. exp Apathy/ 13. exp Motivation Training/ or exp Motivation/ 14. exp Goal Setting/ 15. exp Goal Orientation/ 16. exp Goals/ 17. exp Intention/ 18. exp Generativity/ 19. exp Persistence/ 20. (initiation or persistence or generativity or apathy or motivation or goal$ or intention or persever$ or anergia or indifference or inertia or frontal lobe impairment).ab,ti. 21. or/12‐20 22. exp Behavior Therapy/ 23. exp Cognitive Therapy/ 24. exp Treatment/ 25. exp Rehabilitation/ or exp Neuropsychological Rehabilitation/ or exp Cognitive Rehabilitation/ 26. exp Program Evaluation/ 27. exp Treatment Outcomes/ 28. exp Intervention/ 29. exp Cognitive Behavior Therapy/ 30. exp Treatment Effectiveness Evaluation/ 31. exp Occupational Therapy/ 32. exp Physical Therapy/ 33. exp Art Therapy/ 34. exp Music Therapy/ 35. exp Speech Therapy/ 36. exp Recreation Therapy/ 37. exp Alternative Medicine/ 38. exp Drug Therapy/ 39. exp CNS Stimulating Drugs/ 40. (((cognitive or behavio$r) adj1 therapy) or CBT or "cognitive rehabilitation" or neurorehabilitation).ab,ti. 41. "speech pathology".ab,ti. 42. (central nervous system adj1 (agent$ or stimulant$)).ab,ti. 43. (psychostimulant$ or "stimulant treatment").ab,ti. 44. ((complementary or alternative) adj1 (medicine or therap$ or treatment$)).ab,ti. 45. ((physical or executive or physiotherapy or psychological or occupational or speech or "problem solving" or plan$ or music or art) adj1 (training or treatment or rehab$ or remed$ or program$ or intervention$ or therap$ or approach or technique$ or modification or strateg$ or manag$)).ab,ti. 46. (amphetamine or bemegride or benzphetamine or caffeine or dextramphetamine or doxapram or ephedrine or harmaline or mazindol or methamphetamine or methylphenidate or nikethamide or pemoline or phenmetrazine or phentermine or picrotoxin or bromocriptine or selegine or amantadine or amphetamine or benserazide or benzphetamine or carbidopa or dextramphetamine or dihydroxyphenylalanine or dopamine or fusaric acid or levodopa or memantine).ab,ti. 47. or/22‐46 48. random$.ab,ti. 49. ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj3 (blind$ or dummy or mask$)).ab,ti. 50. placebo$.ab,ti. 51. crossover.ab,ti. 52. assign$.ab,ti. 53. allocat$.ab,ti. 54. ((clin$ or control$ or compar$ or evaluat$ or prospectiv$) adj3 (trial$ or studi$ or study)).ab,ti. 55. exp placebo/ 56. exp mental health program evaluation/ 57. exp experimental design/ 58. or/48‐57 59. 11 and 21 and 47 and 58

www.controlled‐trials.com (searched 31st January, 2008)

apathy AND (neuro% or brain)

www.clinicaltrials.gov (searched 31st January, 2008)

apathy

www.actr.org.au (searched 31st January, 2008)

1. apathy 2. traumatic brain injury

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Smith 1994.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. 3 groups: no treatment control, sham treatment control and experimental treatment. |

|

| Participants | Traumatic brain injury, closed head injury males residing in a sheltered living facility in the USA. N = 21 |

|

| Interventions | Experimental treatment: cranial electrotherapy stimulation given 45 minutes/day, 4 days/week for 3 weeks. Alternating current was used with no d.c. bias, pulsing 100 times/second on a 20% duty cycle, with a maximum of 1.5 mA output. | |

| Outcomes | Profile of Mood States ‐ fatigue/inertia factor. Measures taken pre‐ and post‐treatment. | |

| Notes | N = 14 had been treated for chemical dependency. N = 18 were known seizure patients. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | By drawing names from a hat, participants were assigned to 1 of the 3 groups. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | No mention within the report of allocation concealment. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | Blinding of participants, therapists and assessors measuring the key outcome measure (POMS) was conducted. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | Reported outcome data were complete. |

| Free of selective reporting? | High risk | No between‐intervention group statistical comparisons were reported within the Smith 1994 trial. |

| Free of other bias? | High risk | There were no analyses reported to establish that the intervention groups were similar at baseline. There was also no indication that participants received the treatment to which they were allocated or that any of the key outcomes were analysed by ‘intention‐to‐treat’. |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Chapman 2004 | Not traumatic brain injury. |

| Cummings 2001 | Not traumatic brain injury. |

| Danielczyk 1988 | Not traumatic brain injury. |

| Feldman 2003 | Not traumatic brain injury (same participants as Gauthier 2002). |

| Gauthier 2002 | Not traumatic brain injury (same participants as Feldman 2003). |

| Gelinas 2000 | Not traumatic brain injury. |

| Graff 2006 | Not traumatic brain injury, not randomised controlled trial. |

| Harris 2005 | Not traumatic brain injury. |

| Hozumi 1996 | Not traumatic brain injury. |

| Kaufer 1998 | Not traumatic brain injury. |

| Lanctot 2002 | Not traumatic brain injury. |

| Lebert 1998 | Not traumatic brain injury, not randomised controlled trial. |

| Newburn 2005 | Not randomised controlled trial. |

| Olazaran‐Rodriguez 2004 | Not traumatic brain injury, not randomised controlled trial. |

| Politis 2004 | Not traumatic brain injury. |

| Powell 1996 | Mixed population (traumatic brain injury data not separated), not randomised controlled trial. |

| Swanberg 2007 | Not traumatic brain injury, not randomised controlled trial. |

| Tenovuo 2005 | Not randomised controlled trial. |

| van Reekum 1995 | Not randomised controlled trial. |

| von Cramon 1991 | Mixed population (randomised controlled trial data not separated), not randomised controlled trial. |

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

Morikawa 2000.

| Methods | Case study. |

| Participants | N = 1, otherwise unknown. |

| Interventions | Low dose carbamazepine. |

| Outcomes | Unknown. |

| Notes | In Japanese ‐ currently sourcing translation. |

Timsit‐Berthier 1980.

| Methods | Unknown. |

| Participants | Unknown. |

| Interventions | Lysine‐vasopressin via nasal spray for 15 days (14 UI per day). |

| Outcomes | Unknown. |

| Notes | In French ‐ currently sourcing translation. |

Differences between protocol and review

There were five differences between this review and the protocol, as follows.

Data were not suited to meta‐analysis, therefore we discussed data in a descriptive format. This was not referred to as an option in the protocol.

In the protocol 'activity level' was listed as a secondary outcome measure. After careful reconsideration we instead listed it as a primary outcome measure. This change did not affect the results of this review.

In the protocol both RCTs and quasi‐RCTs were to be included. This review only included RCTs as they are considered the highest level of evidence. Including quasi‐RCTs could potentially introduce bias. This change did not affect the results of the review.

This review did not search www.trialscentral.org because this site currently does not list ongoing clinical trials.

This review included the Cochrane Collaboration 'Risk of bias' figures. These were not mentioned in the protocol as they were released subsequent to publication.

Contributions of authors

ALB and RLT conceived and wrote the review. They were jointly responsible for reviewing papers.

Sources of support

Internal sources

-

Rehabilitation Studies Unit, University of Sydney, Australia.

Infrastructure

External sources

-

Australian Postgraduate Award, Australia.

Funding, in part

-

Northern Medical Research Foundation, Northern Clinical School, University of Sydney, Australia.

Funding, in part

Declarations of interest

None known.

New

References

References to studies included in this review

Smith 1994 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Smith RB, Tiberi A, Marshall J. The use of cranial electrotherapy stimulation in the treatment of closed‐head‐injured patients. Brain Injury 1994;8(4):357‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Chapman 2004 {published data only}

- Chapman SB, Weiner MF, Rackley A, Hynan LS, Zientz J. Effects of cognitive‐communication stimulation for Alzheimer's disease patients treated with Donepezil. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 2004;47:1149‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cummings 2001 {published data only}

- Cummings JL, Nadel A, Masterman D, Cyrus, PA. Efficacy of Metrifonate in improving the psychiatric and behavioral disturbances of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology 2001;14:101‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Danielczyk 1988 {published data only}

- Danielczyk W, Simanyi B, Forette F, Orgogozo J, Pere J, Hugonot L, et al. CBM 36‐733 (2 methyl‐alpha‐ergokryptine) in primary degenerative dementia: Results of a European multicentre trial. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 1988;3:107‐14. [Google Scholar]

Feldman 2003 {published data only}

- Feldman H, Gauthier S, Hecker J, Vellas B, Emir B, Mastey V, et al. Efficacy of Donepezil on maintenance of activities of daily living in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease and the effect on caregiver burden. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2003;51:737‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gauthier 2002 {published data only}

- Gauthier S, Feldman H, Hecker J, Vellas B, Ames D, Subbiah P, et al. Efficacy of Donepezil on behavioral symptoms in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease. International Psychogeriatrics 2002;14(4):389‐404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gelinas 2000 {published data only}

- Gelinas I, Gauthier S, Cyrus P. Metrifonate enhances the ability of Alzheimer's disease patients to initiate, organize, and execute instrumental and basic activities of daily living. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology 2000;13(1):9‐16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Graff 2006 {published data only}

- Graff MJ, Vernooij‐Dassen MJM, Zajec J, Olde‐Rikkert MGM, Hoefnagels WH, Dekker J. How can occupational therapy improve the daily performance and communication of an older patient with dementia and his primary caregiver?. Dementia: The International Journal of Social Research and Practice 2006;5(4):503‐32. [Google Scholar]

Harris 2005 {published data only}

- Harris K, Reid D. The influence of virtual reality play on children's motivation. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy 2005;72(1):21‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hozumi 1996 {published data only}

- Hozumi S, Hori H, Okawa M, Hishikawa Y, Sato K. Favorable effect of transcranial electrostimulation on behavior disorders in elderly patients with dementia: a double‐blind study. International Journal of Neuroscience 1996;88(1‐2):1‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kaufer 1998 {published data only}

- Kaufer D. Beyond the cholinergic hypothesis: the effect of metrifonate and other cholinesterase inhibitors on neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders 1998;9(Suppl 2):8‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lanctot 2002 {published data only}

- Lanctot KL, Herrmann N, Reekum R, Eryavec G, Naranjo CA. Gender, aggression and serotonergic function are associated with response to sertraline for behavioral disturbances in Alzheimer's disease. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2002;17(6):531‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lebert 1998 {published data only}

- Lebert F, Pasquier F, Souliez L, Petit H. Tacrine efficacy in Lewy Body dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 1998;13(8):516‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Newburn 2005 {published data only}

- Newburn G, Newburn D. Selegiline in the management of apathy following traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury 2005;19(2):149‐54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Olazaran‐Rodriguez 2004 {published data only}

- Olazaran‐Rodriguez J, Cruz‐Orduna I, Jimenez‐Martin I. Donepezil therapy in patients with vascular and post‐traumatic cognitive impairment: some clinical observations [Tratamiento con donepecilo en pacientes con deterioro cognitivo vascular y postraumatico: observaciones clinicas]. Revista de Neurologia 2004;38(10):938‐43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Politis 2004 {published data only}

- Politis AM, Vozzella S, Mayer LS, Onyike CU, Baker AS, Lyketsos CG. A randomized, controlled, clinical trial of activity therapy for apathy in patients with dementia residing in long‐term care. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2004;19(11):1087‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Powell 1996 {published data only}

- Powell JH, Al‐Adawi S, Morgan J, Greenwood RJ. Motivational deficits after brain injury: effects of bromocriptine in 11 patients. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 1996;60:416‐21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Swanberg 2007 {published data only}

- Swanberg MM. Memantine for behavioral disturbances in frontotemporal dementia: a case series. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders 2007;21(2):164‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tenovuo 2005 {published data only}

- Tenovuo O. Central acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in the treatment of chronic traumatic brain injury ‐ clinical experience in 111 patients. Progress in Neuro‐Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry 2005;29(1):61‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

van Reekum 1995 {published data only}

- Reekum R, Bayley M, Garner S, Burke IM, Fawcett S, Hart A, et al. N of 1 study: amantadine for the amotivational syndrome in a patient with traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury 1995;9(1):49‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

von Cramon 1991 {published data only}

- Cramon D, Matthes‐von Cramon G, Mai N. Problem‐solving deficits in brain‐injured patients: a therapeutic approach. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation 1991;1(1):45‐64. [Google Scholar]

References to studies awaiting assessment

Morikawa 2000 {published data only}

- Morikawa, M. Successful treatment using low‐dose Carbamazepine for a patient of personality change after diffuse brain injury. Japanese Journal of Psychopharmacology 2000;20(4):149‐153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Timsit‐Berthier 1980 {published data only}

- Timsit‐Berthier M, Mantanus H, Jacques MC, Legros JJ. Use of lysine‐vasopressine in the treatment of post‐traumatic amnesia. Acta Psychiatrica Belgica 1980;80(5):728‐747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine 1995

- American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine. Recommendations for use of uniform nomenclature pertinent to patients with severe alterations in consciousness. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 1995;76:205‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Baker 2001

- Baker R, Bell S, Baker E, Gibson S, Holloway J, Pearce R, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the effects of multi‐sensory stimulation (MSS) for people with dementia. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 2001;40(1):81‐96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Crepeau 1997

- Crepeau F, Scherzer P, Belleville S, Desmarais G. A qualitative analysis of central executive disorders in a real‐life work situation. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation 1997;7:147‐65. [Google Scholar]

Deb 2004

- Deb S, Crownshaw T. The role of pharmacotherapy in the management of behaviour disorders in traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury 2004;18(1):1‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Evans 1998

- Evans JJ, Emslie H, Wilson B. External cueing systems in the rehabilitation of executive impairments of action. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 1998;4:399‐408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Finset 2000

- Finset A, Andersson S. Coping strategies in patients with acquired brain injury: relationships between coping, apathy, depression and lesion location. Brain Injury 2000;14(10):887‐905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fitzsimmons 2003

- Fitzsimmons S, Buettner LL. A therapeutic cooking program for older adults with dementia: effects on agitation and apathy. American Journal of Recreation Therapy 2;4:23‐33. [Google Scholar]

Glenn 2002

- Glenn MB, Burke DT, O'Neil‐Pirozzi T, Goldstein R, Jacob L, Kettell J. Cutoff score on the apathy evaluation scale in subjects with traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury 2002;16(6):509‐16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2002

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in meta‐analysis. Statistics in Medicine 2002;21:1539‐58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2005

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 4.2.5 [updated May 2005]. The Cochrane Library. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2005; Vol. Issue 3.

Higgins 2008

- Higgins JPT, Altman DG. Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S editor(s). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 5.0.0. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008. [Google Scholar]

Kant 1998

- Kant R, Duffy JD, Pivovarnik A. Prevalence of apathy following head injury. Brain Injury 1998;12(1):87‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kant 2002

- Kant R, Smith‐Seemiller L. Assessment and treatment of apathy syndrome following head injury. NeuroRehabilitation 2002;17:325‐31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kay 1993

- Kay T, Adams R, Anderson T, Berrol S, Cicerone K, Dahlberg C, et al. Definition of mild traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 1993;8(3):86‐7. [Google Scholar]

Levy 1998

- Levy M, Cummings J, Fairbanks L, Masterman D, Miller B, Craig A, et al. Apathy is not depression. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 1998;10(3):314‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Luria 1973

- Luria AR. The Working Brain. Middlesex: The Penguin Press, 1973. [Google Scholar]

Maher 2003

- Maher CG, Sherrington C, Herbert RD, Moseley AM, Elkins M. Reliability of the PEDro scale for rating quality of randomised controlled trials. Physical Therapy 2003;83(8):713‐21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marin 1990

- Marin R. Differential diagnosis and classification of apathy. American Journal of Psychiatry 1990;147(1):22‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marin 1991

- Marin R. Apathy: a neuropsychiatric syndrome. Journal of Neuropsychiatry 1991;3(3):243‐54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marin 1991b

- Marin R, Firiniciogullari S, Biedrzycki RC. Reliability and validity of the Apathy Evaluation Scale. Psychiatry Research 1991;38:143‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marin 1996

- Marin R. Apathy and related disorders of diminished motivation. In: Dickstein L, Riba M editor(s). Review of Psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1996:205‐42. [Google Scholar]

Marin 2005

- Marin R, Chakravorty M. Disorders of diminished motivation. In: Silver JM, McAllister TW, Yudofsky SC editor(s). Textbook of traumatic brain injury. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc, 2005:337‐52. [Google Scholar]

Marin 2005b

- Marin R, Wilkosz P. Disorders of diminished motivation. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 2005;20(4):377‐88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marsh 1998

- Marsh NV, Kersel DA, Havill JH, Sleigh JW. Caregiver burden at 1 year following severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury 1998;12(12):1045‐59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McMillan 1999

- McMillan T, Sparkes C. Goal planning and neurorehabilitation: The Wolfson Neurorehabilitation Centre approach. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation 1999;9(3/4):241‐51. [Google Scholar]

Perdices 2006

- Perdices M, Schultz R, Tate R, McDonald S, Togher L, Savage S, et al. The evidence base of neuropsychological rehabilitation in acquired brain impairment (ABI): how good is the research?. Brain Impairment 2006;7(2):119‐32. [Google Scholar]

Prigatano 1992

- Prigatano GP. Personality disturbances associated with traumatic brain injury. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 1992;3:360‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Purdie 1997

- Purdie H. Music therapy with adults who have traumatic brain injury and stroke. British Journal of Music Therapy 1997;11(2):45‐50. [Google Scholar]

Review Manager 5 [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre. Review Manager. Version 5.0. Copenhagen: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008.

Roth 2007

- Roth R, Flashman L, McAllister T. Apathy and its treatment. Current Treatment Options in Neurology 2007;9:363‐70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Stuss 2000

- Stuss DT, Reekum R, Murphy KJ. Differentiation of states and causes of apathy. In: Borod J editor(s). The Neuropsychology of Emotion. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000:340‐63. [Google Scholar]

Tate 2004

- Tate RL, Perdices M, McDonald S, Togher L, Moseley A, Winders K, et al. Development of a database of rehabilitation therapies for the psychological consequences of acquired brain impairment. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation 2004;14(5):517‐34. [Google Scholar]

Wilson 2002

- Wilson B, Evans J, Keohane C. Cognitive rehabilitation: a goal planning approach. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 2002;17(6):542‐55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]