Abstract

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) is associated with an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events, impaired lower extremity blood flow and microvascular perfusion abnormalities in the calf muscles which can be determined with contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (CE-MRI). We developed a computational model of the microvascular perfusion in the calf muscles. We included 20 patients (10 PAD, 10 controls) and utilized the geometry, mean signal intensity and arterial input functions from CE-MRI calf muscle perfusion scans. The model included the microvascular pressure (pv), outflow filtration coefficient (OFC), transfer rate constant (kt), porosity (φ), and the interstitial permeability (Ktissue). Parameters were fitted and the simulations were compared across PAD patients and controls. Intra-observer reproducibility of the simulated mean signal intensities was excellent (intraclass correlation coefficients >0.995). kt and Ktissue were higher in PAD patients compared with controls (4.72 interquartile range (IQR) 3.33, 5.56 vs. 2.47 IQR 2.10, 2.85; p=0.003; and 3.68 IQR 3.18, 4.41 vs. 1.81 IQR 1.81, 1.81; p<0.001). Conversely, porosity (φ) was lower in PAD patients compared with controls (0.52 IQR 0.49, 0.54 vs. 0.61 IQR 0.58, 0.64; p=0.016). Porosity (φ) was correlated with the ankle brachial index (r= 0.64, p=0.011). The proposed computational microvascular model is robust and reproducible, and essential model parameters differ significantly between PAD patients and controls.

Keywords: Modeling, Computational Fluid Dynamics, Microvascular Circulation, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Peripheral Artery Disease

1. Introduction

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) is a vascular disease represented by the formation of atherosclerotic lesions in the lower limbs (Fowkes et al. 2013, Gardner and Afaq 2008, Lim 2013, Brunner et al. 2013, Brunner et al. 2016, Kamran et al. 2016). PAD is associated with higher risk of coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, and cardiovascular death (Gardner and Afaq 2008, Newman et al. 1991). Approximately 27 million people suffer from PAD in Europe and North America (Criqui and Aboyans 2015). PAD patients can experience leg pain, reduced exercise capacity, and the tissue loss. Improving small vessel blood flow at the level of the leg muscles is a challenge in PAD patients, however, tissue revascularization and therapeutic drugs that increase tissue perfusion show limited success (Silva et al. 2004, Stoner et al. 2008, Phelps and Garcia 2009). Skeletal leg muscle perfusion using contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (CE-MRI) is of interest to study microvascular muscle perfusion in PAD patients (Brunner et al. 2016, Kramer 2008, Thompson et al. 2005). Previous work (Brunner et al. 2016) suggests that muscle perfusion is heterogeneous across calf muscle compartments and reduced in PAD compared with controls. A computational model capable of measuring tissue transport properties based on CE-MRI perfusion data could be of clinical interest for assessing the severity of PAD and monitoring the response to novel drug treatment designed to enhance muscle perfusion and improve claudication pain.

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) has good agreement with CE-MRI measurements in cardiovascular disease applications (Cibis et al. 2016, Singh et al. 2018, Hossain et al. 2015). Numerical models are an important tool to study tissue perfusion on different scales including from large vessels to the microcirculation (Debbaut et al. 2011, van der Plaats et al. 2004, Rani et al. 2006). The microvasculature can be modeled as a porous medium with permeability and porosity. Debbaut et al. developed a model of the blood flow in the human sinusoidal microcirculation using CFD methods. Blood was modeled as an incompressible and Newtonian fluid with a constant density and dynamic viscosity.

This study presents the simulation of CE-MRI signal intensities in five distinct calf tissue regions including the anterior muscle (AM), lateral muscle (LM), deep posterior muscle (DM), soleus muscle (SM) and gastrocnemius muscle (GM). The aim of this work was to (i) estimate and model microvascular transport properties in the calf muscles, and (ii) compare the tissue transport properties between PAD patients and controls. The coupled equations of convection-diffusion and reaction terms were solved using Finite Element Methods (FEM). Simulated signal intensities were compared with CE-MRI signal intensities that permit the estimation of the best model parameters.

2. Materials and Methods

PAD patients with life-style limiting intermittent claudication (IC) and controls were recruited at the Houston Methodist Hospital and the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC), as described previously (Brunner et al. 2016, Holbrook et al. 2016). Matched controls and healthy controls without PAD were also recruited at the same sites. This study obtained approval from the local institutional review board (IRB) and all participants provided informed consent.

2.1. CE-MRI and Image analysis

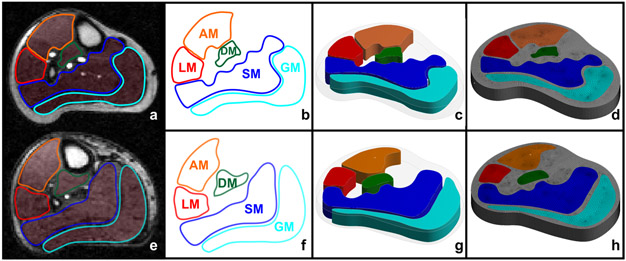

The acquired structural CE-MRI datasets were saved in DICOM format. The high-resolution saturation recovery gradient echo (GRE) pulse sequence had a slice thickness of 10 mm and a temporal resolution of 409 ms, as detailed previously (Brunner et al. 2016). We selected CE-MRI scans from 10 PAD patients, 5 matched controls and 5 healthy controls. Five distinct leg muscle domains (Fig. 1a, e) including the AM, LM, DM, SM, and GM were semi-automatically segmented using an in-house graphical user interface developed in MATLAB (MathWorks 2012), as reported before (Brunner et al. 2016). The full model algorithm is available in Fig. 2.

Figure 1 –

(a, e): CE-MR images of a control and PAD patient; (b, f): for semi-automatically segmented leg muscle regions of a control and a PAD patient; (c, g): 3D models a control and a PAD patient; and (d, h): meshed domains of AM: anterior muscle, LM: lateral muscle, DM: deep posterior muscle, SM: soleus muscle, and GM: gastrocnemius muscle.

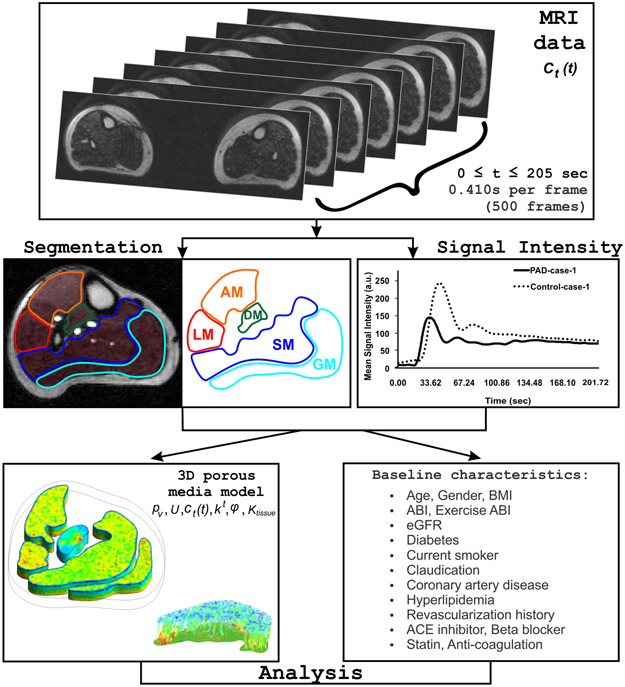

Figure 2 –

Algorithm depicting the various steps involved in the computational microvascular model, including MRI data acquisition, segmentation, arterial input function (AIF) of a healthy control (dotted line) and a PAD patient (solid line) described in terms of mean signal intensity, model, and analysis.

2.2. Geometry Reconstruction

For the 3D tissue computational domain, distinct leg muscle domains and leg contours (Fig. 1b, f) were imported in the ANSYS SpaceClaim application within the ANSYS Workbench (v. 18.2) software to create 3D volumes (Fig. 1c, g). Leg segments were modeled with a thickness of 10 mm to maintain continuity and clinical relevance (same as slice-thickness of CE-MRI perfusion scans).

2.3. Mathematical Modeling

Tofts-Kermode two-compartment model.

We based our computational microvascular model on the two-compartment Tofts-Kermode (TK) model (Tofts and Kermode 1991) of plasma and tissue to describe the CE-MR signal enhancement with a gadolinium based contrast agent as a reaction term in the tissue regions

| (1) |

where cp represents the concentration of the contrast agent in the blood; ct is the concentration of the contrast agent in the tissue; kt is the transfer rate constant for a given tissue; Ri is the reaction term in the ith tissue region. φ is a computational approximation of the fraction of extracellular space or tissue porosity whereas (1 – φ)*100 is an approximation of the percentage of fibrosis in the muscle domains in the computational model.

A convection-diffusion and reaction model was adopted to simulate 3D convection-enhanced delivery (CED) in the tissue regions. The tracer transport during CED was modeled using the convection-diffusion equation (Pishko et al. 2011, Pishko et al. 2012) as,

| (2) |

where ct is the concentration of contrast agent in the tissue; Di is the diffusion of contrast agent; OFC is defined as the outflow filtration coefficient (OFC); and pi = 1066 Pa is the interstitial fluid pressure (IFP) (Heldin et al. 2004). We utilized colloid osmotic pressures in the normal healthy capillaries as 8 mm Hg (1066.6 Pa) and therefore the IFP was set to pi = 1066 Pa for the boundary condition on the cut ends of the leg surface (Heldin et al. 2004). This surface was not far away from the region of interest and hence a normal tissue pressure on the outlet surface was not utilized (pi = 0 Pa). Pishko et al. (Pishko et al. 2011) defined IFP in the range of 0.86 – 1.4 KPa. The average value of the parameter (close to IFP of capillaries) allowed the estimation of the pressure in the region of interest.

Porous Media Model.

The muscle tissue was modeled as a porous media (Pishko et al. 2011, Pishko et al. 2012). The muscle domains were based on CE-MRI data of the user-defined model of elastic solid tissue with a porosity of 20-80% (Table 1). In tissues, the continuity equation and Darcy’s law were used to solve the interstitial fluid pressure IFP (pi) and tissue averaged interstitial fluid velocity IFV (Ui) as,

| (3) |

| (4) |

kavg is the average value of kt; the second term on the right of equation 3. is the capillary filtration coefficient (CFC), where, Ktissue is the tissue permeability; is the microvascular surface area per unit volume; pv is the microvascular pressure (MVP); pi is the IFP, σ is the average osmotic reflection for plasma protein, πv is the osmotic pressure of plasma in the microvasculature, and πi is the osmotic pressure in the interstitial space; the parameter Ktissue represents the interstitial permeability to fluid flow and is reflective of the composition of the extracellular matrix (Pishko et al. 2011). Next, Ktissue/μ was scaled by porosity which describes heterogeneity or porosity dependent hydraulic conductivity in the muscle tissue in the computational model. The ratio in equation 4 describes an approximation of the degree of flow versus non-flow (fibrosis). The ratio in equation 3 accounts for plasma leakiness heterogeneities in the muscle tissue (Pishko et al. 2011); (pv – pi) is the difference between the MVP and IFP; μ is the blood viscosity. More details on the porous media model are listed in Appendix A (Porous Media Model).

Table 1 –

Fixed and fitted parameters of the simulations.

| Parameters | Variable | Tissue | Type | Bounds\Value | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| πv | Osmotic pressure in microvasculature | Calf Muscle | Fixed | 2670 Pa or 20 mmHg | (Pishko et al. 2011) |

| πi | Osmotic pressure in tissue | Calf Muscle | Fixed | 200 Pa | (Debbaut et al. 2012, Brunner et al. 2016, Pishko et al. 2011) |

| pi | Interstitial fluid pressure | Calf Muscle | Fixed | 1066 Pa | (Heldin et al. 2004) |

| σ | Average osmotic reflection coefficient | Calf Muscle | Fixed | 0.82 | (Rippe et al. 1985) |

| μ | Blood viscosity | Blood | Fixed | 3.5·10−3 Pa s | (Leong et al. 2013) |

| Di | Self-diffusion coefficient of contrast agent | Calf Muscle | Fixed | 1.83·10−9 m2/s | (Dietrich et al. 2010) |

| ρ | Density | Calf Muscle | Fixed | 1060 kg/m3 | (Bouillard et al. 2011, Davidson et al. 2014, Johnston et al. 2006) |

| Y | Elasticity Module | Calf Muscle | Fixed | 0.4 MPa | (Frauziols et al. 2013, Grishina et al. 2016) |

| T | Temperature | Calf Muscle/Blood | Fixed | 37 °C | (Dubuis et al. 2012, Kenner 1989) |

| ζ | Resistance of blood | Calf Muscle | Fixed | 2.5·109 mmHg/m3 | (Siggers et al. 2014) |

| pv | Microvascular pressure | Calf Muscle | Free | 6666.7 Pa (or 50 mmHg) * 50 to 170 mmHg | Estimated from curve fitting and literature (Stylianopoulos and Jain 2013, Thompson et al. 2005, Yang et al. 2013) |

| CFC | Capillary filtration coefficient | Calf Muscle | Free | 7.216·10−6 (1/Pa s)* 1·10−7 (1/Pa s) | Estimated from curve fitting and literature (Pishko et al. 2011) |

| OFC | Outflow filtration coefficient | Calf Muscle | Free | 6·10−7 to 15·10−7 (1/Pa s)* | Estimated from curve fitting |

| kt | Transfer rate constant | Calf Muscle | Free | 0.6·10−3 to 1·10−2* 1/s 4·10−2 1/s | Estimated from curve fitting and literature (Ren 2015) |

| φ | Porosity | Calf Muscle | Free | 0 to 1* 0.12 | Estimated from curve fitting and literature (Smye et al. 2007) |

| Ktissue | Interstitial permeability to fluid flow | Calf Muscle | Free | 1.27·10−9 to 2.98·10−5 m2 * 1.56·10−9 to 3.64·10−14 m2 | Estimated from curve fitting and literature (Debbaut et al. 2012) |

Estimated from curve fitting

The transient value of the flow properties such as blood perfusion velocity and pressure were determined in each muscle domain. Blood perfusion was assumed to be transient, incompressible flow. Mass sources were used for introducing additional fluid into the simulation. The amount of fluid introduced was specified as fluid mass flux (on boundaries).

The arterial input function obtained from the CE-MRI scans (Brunner et al. 2016) specific to each muscle group were applied for the simulation (Fig. 2) and corresponded to the mean signal intensity of the contrast agent in the blood plasma. The full information about the model parameters is available in Table 1. We have modeled changes in signal intensities based on the administration of a gadolinium-based contrast agent rather than actual blood flow velocities. Signal intensities for the boundary conditions were obtained from CE-MRI scans of PAD patients and controls. However, the equations remain expressed in velocities rather than in changes of arbitrary signal intensities from CE-MRI scans.

2.3.1. Mathematical Modeling With A Non-Newtonian Fluid

Several studies have previously reported on the use of a Newtonian fluid approximation for similar types of models (Javadzadegan et al. 2019, Vankan et al. 1998, Bouillot et al. 2015, Zhao et al. 2018, Bonfiglio et al. 2010, Boyd, Buick and Green 2007, Zhang et al. 2015). However, we have also performed the same models with a non-Newtonian fluid for 10 out of the 20 cases (5 PAD patients and 5 controls) in order to compare with the Newtonian fluid approach. The dynamic viscosity of human blood in dependency of the shear rate was set up as variations of shear rates from 0.1 s−1 to 1000 s−1 at a constant temperature of 37°C. We used the Carreau-Yasuda model as done in Boyd et al. (Boyd et al. 2007), which is a more generalized Carreau model. Then, blood was modeled as a non-Newtonian fluid using Carreau-Yasuda model to determine blood viscosity, as described by Zhang et al. (Zhang et al. 2015). The relationship between shear rate and viscosity was expressed as

| (5) |

where η∞ and η0 are the infinite and zero shear rate viscosities, and λ is the relaxation time constant. The model has been found to fit to the experimental data with the following parameters: , , n = 0.3568 and λ = 3.313 s.

2.4. Mesh

For the computational domain, each segmented 3D muscle region of the controls and PAD patients was meshed using Ansys Mesh (Fig. 1d, h). The cell size of each muscle region was setup based on the grid mesh and the transient time step sensitivity tests.

2.4.1. Grid test

The grid independence test was performed to assess mesh quality by varying the number of control volumes in the computational domain. A final element mesh was selected to resolve the velocity vectors and capture the hemodynamics at various regions in different muscle groups.

The leg geometry was discretized into three different mesh categories: hexahedral mesh, tetrahedral mesh with and without boundary layer (hybrid mesh) using ANSYS Workbench (v.18.2). The modelling results were evaluated in three different planes taken in the AM, LM, DM, SM and GM separately with fixed porous materials parameters and boundary conditions. The variation of less than 5% was observed for maximum simulated signal intensity, and average pressure for grid size ranging from 200,000 to 250,000 elements. Therefore, the optimum size of 237,917 tetrahedral elements consisting of 13 layers by model thickness was used.

Tetrahedral hybrid mesh and hexahedral elements showed close agreement with the simulated signal intensity and pressure variation unlike the tetrahedral mesh toward as higher mesh size in the range of 150,000 to 180,000 elements. The variation was less than 0.7% between the tetrahedral hybrid and hexahedral mesh while in the tetrahedral mesh it was greater than 3%. Hence, a hexahedral mesh in the range of 85,000 to 100,000 elements per muscle volume was used over tetrahedral mesh for further evaluation purposes due to similar variation and fewer complications in the grid generation.

The global mesh size was set to 0.001 m. To ensure an accurate analysis of the muscles, a finer mesh was applied to the muscle sites (0.0008 m for AM, LM, SM, 0.0005 m for DM, GM). Model sizes ranging from 57,000 to 95,000 hexahedral elements consisting of 13 layers by model thickness were used with the unstructured mesh.

2.4.2. Transient time step sensitivity test

A time step sensitivity test was done to select the appropriate time step for the transient analysis. CE-MRI was measured on average over 205s and the optimum time step was obtained through time step sensitivity test during transient analysis. The FEM (CFX ANSYS v.18.2) of the control group was used to perform the sensitivity test. The transient analysis was performed with 0.051s (4000 steps), 0.103s (2000 steps), 0.410s (500 steps) and 1.025s (200 steps). A common plane taken at mid-section of the FEM was used to analyze the maximum simulated signal intensity and average pressure for different time steps.

2.5. Curve fitting and error analysis

The resulting solution was integrated over the muscle tissue domain to get the mean signal intensity as a function of time. Mean square error (MSE) and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) were calculated as a measure of estimating the best agreement between simulated and CE-MRI signal intensities. The MSE was computed as,

| (6) |

where, represents the vector of predicted values and yi represents the experimental values; and n is the number of time steps. MAPE was computed as,

| (7) |

2.6. Model Analysis

For model robustness, we analyzed the AM of a PAD patient (Fig. 1e) with the parameter values in Table 1 which were selected from the literature (Bouillard, Nordez and Hug 2011, Brunner et al. 2016, Dubuis et al. 2012, Frauziols et al. 2013, Grishina, Kirillova and Glukhova 2016, Hinghofer-Szalkay and Greenleaf 1987, Johnston et al. 2006, Kenner 1989, Leong et al. 2013, Stylianopoulos and Jain 2013, Thompson et al. 2005, Yang et al. 2013). We have varied each parameter by decreasing and increasing them over a range from 50%-200%, respectively. Variation of the diffusion coefficient (Di) of the contrast agent did not influence the mean signal intensity over time. A similar observation has been reported previously by Pishko et al (Pishko et al. 2011). Variations in the interstitial permeability to fluid flow (Ktissue) in the muscle tissue, osmotic pressures (πv, πi) and osmotic reflection coefficient (σ) did not influence the mean signal intensity over time.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Variables were expressed as median (interquartile range [IQR]), percentages or frequencies. The nonparametric Mann-Whitney test was used to assess the difference between unpaired group data. Categorical group data were analyzed with the Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. The strength of correlations was described as weak (r <0.3), medium (0.3 ≤ r < 0.5), or strong (r ≥0.5) (Cohen 1988). Reproducibility analyses were performed using intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) with a 2-way random-effects model (Shrout and Fleiss 1979). The agreement of the reproducibility analysis is considered poor for an ICC <0.30, moderate-to-good for an ICC of 0.30–0.70, and excellent for an ICC>0.70 (Shrout and Fleiss 1979, Carod-Artal et al. 2009).

All analyses were performed using StatalC 13. Statistical significance is indicated as * (p < 0.05), ** (p < 0.01), and *** (p < 0.001).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Baseline characteristics

A total of 20 individuals (10 PAD patients, 5 matched-controls, 5 healthy controls) were included in this study. There was no difference in age, gender, body mass index (BMI), and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) between PAD patients and matched controls (Table 2). PAD patients had a lower ankle brachial index (ABI) and were more likely diabetic and hypertensive compared with controls.

Table 2 –

Baseline characteristics.

|

Variable |

PAD (n = 10) |

Matched Controls (n = 5) |

P-value (PAD vs Matched Controls) |

Healthy Controls (n = 5) |

P-value (Matched Controls vs Healthy Controls) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 67.6 (7.6) | 65.6 (7.1) | 0.63 | 34.6 (4.8) | 0.001 |

| Gender male, no (%) | 6 (60) | 4 (80) | 0.44 | 5 (100) | 0.29 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.0 (6.4) | 26.9 (5.2) | 0.36 | 27.1 (4.0) | 0.94 |

| ABI | 0.7 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.1) | 0.003 | N/A | N/A |

| Exercise ABI | 0.6 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.1) | 0.006 | N/A | N/A |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 79.3 (24.0) | 81.3 (12.4) | 0.86 | N/A | N/A |

| Diabetes, no (%) | 6 (60) | 0 (0) | 0.025 | 0 (0) | - |

| Hypertension, no (%) | 9 (90) | 2 (40) | 0.039 | 0 (0) | 0.11 |

| Current smoker, no (%) | 3 (30) | 0 (0) | 0.20 | 0 (0) | - |

| Claudication, no (%) | 8 (80) | 0 (0) | 0.003 | 0 (0) | - |

| Coronary artery disease, no (%) | 6 (60) | 1 (20) | 0.14 | 0 (0) | 0.29 |

| Hyperlipidemia, no (%) | 8 (80) | 2 (40) | 0.12 | 0 (0) | 0.11 |

| Revascularization history, no (%) | 4 (40) | 0 (0) | 0.099 | 0 (0) | - |

| ACE inhibitor, no (%) | 3 (30) | 0 (0) | 0.17 | 0 (0) | - |

| Beta blocker, no (%) | 3 (30) | 0 (0) | 0.17 | 0 (0) | - |

| Statin, no (%) | 7 (70) | 2 (40) | 0.54 | 0 (0) | 0.11 |

| Anti-coagulation, no (%) | 3 (30) | 1 (20) | 0.49 | 0 (0) | 0.29 |

Values are reported as mean (standard deviation) or as number (percentage). N/A not applicable (not measured).

ABIs are listed for the more symptomatic side. Exercise ABI (n=7).

ABI: Ankle brachial index, ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme, BMI: body mass index, eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate.

3.2. Computational microvascular model

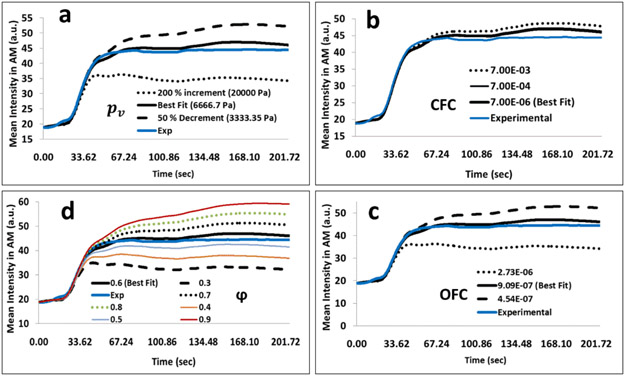

Electronic Supplementary Material Fig. 1 shows the simulated and experimental mean signal intensities of a control (Electronic Supplementary Material Fig. 1a) and PAD (Electronic Supplementary Material Fig. 1b) patient for muscle domains AM, LM, DM, SM, and GM, respectively. We have varied the microvascular pressure (pυ), CFC, OFC and porosity over a range of −50% to 200%. The mean signal intensity profile was sensitive to MVP (Fig. 3a), OFC (Fig. 3c) and tissue porosity (Fig. 3d). The CFC was sensitive in the order of magnitude from the optimal value (Fig. 3b). MSE and MAPE for training the models were less than 5% (Fig. 3). Electronic Supplementary Material Table 1 shows the parameter values for PAD and control cases.

Figure 3 –

Representative plot of the mean signal intensity with respect to change in (a) microvascular pressure (pv) (b) the capillary filtration coefficient (CFC) (c) the outflow filtration coefficient (OFC) and, (d) the fraction of extracellular space (φ). The solid lines represent the optimal parameter (best fit) whereas dashed lines represent a decrease of 50% and the dotted lines represent an increase by 200 % except in (d), whereas the mean signal intensity was simulated for a range of ± 8.33 %.

3.3. Computational microvascular model reproducibility

Intra-rater reproducibility for simulated mean signal intensity of a PAD patient over all time steps was excellent for the AM (intra-class correlation [ICC]: 0.999 confidence interval [CI]: 0.978, 1.0) and similar for the other muscle groups (Table 3a). Transient time step sensitivity test showed that the maximum simulated signal intensity and average pressure during 500 and 2000 time steps were almost identical (less than 0.02%) without any considerable difference with quite less at 4000 time step (less than 0.07%); however, there was a difference for 125 time steps (more than 6%). Inter-rater reproducibility for simulated mean signal intensity of 3 PAD patients and 5 controls over all time steps was excellent for the AM (PAD: 0.984 CI: 0.982, 0.985; Controls: 0.988 CI: 0.987, 0.989) and of a similar agreement for the LM, DM, SM, and GM, respectively (Table 3b, c).

Table 3 –

Intra-observer (a) and inter-reader variability of simulated mean signal intensity of a PAD patient (b) and a control (c) for each muscle region (AM, LM, DM, SM, GM) determined by intra-class correlation (ICC) coefficient using a two-way model.

| a) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intra-observer ICC for AM |

Intra-observer ICC for LM |

Intra-observer ICC for DM |

Intra-observer ICC for SM |

Intra-observer ICC for GM |

|

| Individual ICC | .999 | .998 | .998 | .995 | .999 |

| (95% CI) | .978-1 | .966-.999 | .964-.999 | .922-.999 | .995-1 |

| Average ICC | 1 | .999 | .999 | .998 | 1 |

| (95% CI) | .993-1 | .989-1 | .988-1 | .972-1 | .998-1 |

| ICC was calculated for each time step, 1 PAD patient (number of targets 500) and for 3 independent calculations with different mesh size in range 0.0005 to 0.0008 m. | |||||

| b) | |||||

| Inter-observer ICC for AM |

Inter-observer ICC for LM |

Inter-observer ICC for DM |

Inter-observer ICC for SM |

Inter-observer ICC for GM |

|

| Individual ICC | .984 | .978 | .855 | .881 | .98 |

| (95% CI) | .982-.985 | .976-.979 | .844-.865 | .872-.89 | .979-.982 |

| Average ICC | .992 | .989 | .922 | .937 | .99 |

| (95% CI) | .991-.992 | .988-.99 | .915-.928 | .932-.942 | .989-.991 |

| ICC was calculated for each time step, 5 cases (number of targets 2479) and for 2 independent raters. | |||||

| c) | |||||

| Inter-observer ICC for AM |

Inter-observer ICC for LM |

Inter-observer ICC for DM |

Inter-observer ICC for SM |

Inter-observer ICC for GM |

|

| Individual ICC | .988 | .972 | .915 | .873 | .927 |

| (95% CI) | .987-.989 | .969-.975 | .907-.923 | .86-.884 | .92-.934 |

| Average ICC | .994 | .986 | .956 | .932 | .962 |

| (95% CI) | .993-.995 | .984-.987 | .951-.96 | .925-.939 | .958-.966 |

| ICC was calculated for each time step, 3 cases (number of targets 1498) and for 2 independent raters. ICC: intra-class correlation; CI: confidence interval. | |||||

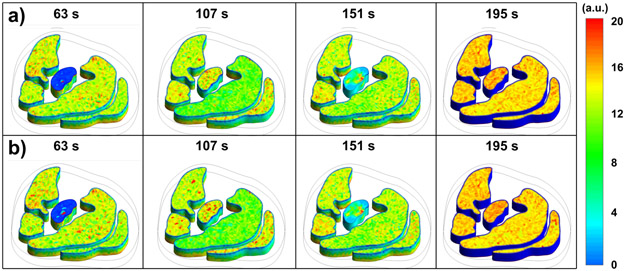

3.4. Computational microvascular model: Comparison between a Newtonian and Non-Newtonian fluid

Reproducibility analysis for simulated mean signal intensity of 5 PAD patients over all time steps was excellent between Newtonian and Non-Newtonian models (Fig. 4) for the AM (intra-class correlation [ICC]: 0.945 confidence interval [CI]: 0.941, 0.950), LM ([ICC]: 0.993, [CI]: 0.992, 0.993), DM ([ICC]: 0.969, [CI]: 0.967, 0.972), SM ([ICC]: 0.963, [CI]: 0.960, 0.966), and GM ([ICC]: 0.992, [CI]: 0.992, 0.993) (Table 4a).

Figure 4 –

Simulated signal intensities of contrast-enhanced MRI calf muscle perfusion (AM, LM, DM, SM, GM) for a PAD patient at different time points (seconds): a) Newtonian model, b) Non-Newtonian model.

Table 4.

Reproducibility analysis of the simulated mean signal intensity of controls and PAD patients for each muscle region (AM, LM, DM, SM, GM), as determined by intra-class correlation (ICC) using a two-way model for non-Newtonian and Newtonian models.

| a) PAD Patients (n=5) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inter-observer ICC for AM |

Inter-observer ICC for LM |

Inter-observer ICC for DM |

Inter-observer ICC for SM |

Inter-observer ICC for GM |

|

| Individual ICC | 0.945 | 0.993 | 0.969 | 0.963 | 0.992 |

| (95% CI) | 0.941–0.950 | 0.992–0.993 | 0.967–0.972 | 0.960–0.966 | 0.992–0.993 |

| Average ICC | 0.972 | 0.996 | 0.984 | 0.981 | 0.996 |

| (95% CI) | 0.970–0.974 | 0.996–0.997 | 0.983–0.986 | 0.980–0.983 | 0.996–0.996 |

| ICC: intra-class correlation; CI: confidence interval. ICC was calculated for each time step, 5 cases (Number of targets 2479) and for 2 observations. | |||||

| b) Controls (n=5) | |||||

| Inter-observer ICC for AM |

Inter-observer ICC for LM |

Inter-observer ICC for DM |

Inter-observer ICC for SM |

Inter-observer ICC for GM |

|

| Individual ICC | 0.987 | 0.993 | 0.880 | 0.992 | 0.980 |

| (95% CI) | 0.986–0.988 | 0.992–0.993 | 0.871–0.888 | 0.991–0.993 | 0.978–0.982 |

| Average ICC | 0.994 | 0.996 | 0.936 | 0.996 | 0.990 |

| (95% CI) | 0.993–0.994 | 0.996–0.997 | 0.931–0.941 | 0.996–0.996 | 0.989–0.991 |

| ICC: intra-class correlation; CI: confidence interval. ICC was calculated for each time step, 5 cases (Number of targets 2498) and for 2 observations. | |||||

Reproducibility analysis for simulated mean signal intensity of 5 controls over all time steps was excellent for the DM ([ICC]: 0.880, [CI]: 0.871, 0.888), AM ([ICC]: 0.987, [CI]: 0.986, 0.988), LM ([ICC]: 0.993, [CI]: 0.992, 0.993), SM ([ICC]: 0.992, [CI]: 0.991, 0.993), and GM ([ICC]: 0.980, [CI]: 0.978, 0.982) (Table 4b).

3.4. Computational microvascular model parameters

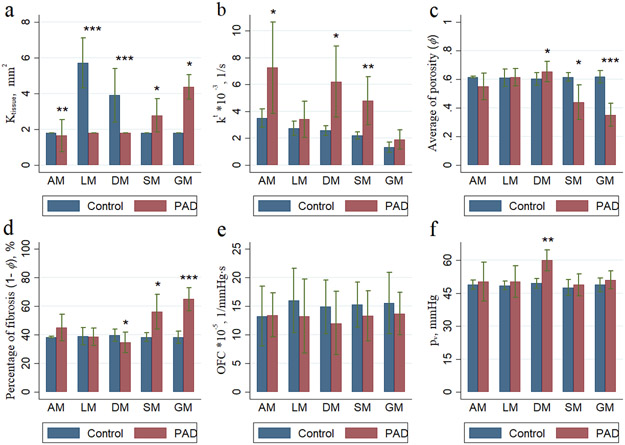

The simulated signal intensity of the contrast agent is shown in Fig. 5 at different time points (seconds). Averaged over all muscle groups, kt and Ktissue were higher in PAD patients compared with controls (4.72 IQR: 3.33, 5.56 vs. 2.47 IQR 2.10, 2.85; p=0.003; and 3.68 IQR 3.18, 4.41 vs. 1.81 IQR 1.81, 1.81; p<0.001, Table 5). Conversely, porosity (φ) averaged over all muscle groups was lower in PAD patients compared with controls (0.52 IQR 0.49, 0.54 vs. 0.61 IQR 0.58, 0.64; p=0.016) (Electronic Supplementary Material Fig. 2). Modeling parameters were heterogeneous across individual calf muscle groups (Electronic Supplementary Material Table 2). In PAD patients, compared to controls, Ktissue was significantly higher in all five muscle groups, whereas kt was significantly increased in the AM, DM, and SM but not in the LM and GM (Fig. 6). Similarly, pυ was significantly higher in the DM (p=0.003) for PAD patients as compared to controls but was not different for the other muscles. Porosity (φ) was significantly lower in PAD patients compared with controls in the SM and GM but higher for the DM. There was no group difference for the OFC.

Figure 5 –

Simulated signal intensities of contrast-enhanced MRI calf muscle perfusion (AM, LM, DM, SM, GM) for a PAD patient at different time points (seconds).

Table 5 –

Analyse of baseline patient characteristics and modeling parameters.

| Variable | Control | PAD | Total | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kt | 2.47 (2.10, 2.85) | 4.72 (3.33, 5.56) | 3.59 (2.39, 4.74) | 0.003 |

| Ktissue | 1.81 (1.81, 1.81) | 3.68 (3.18, 4.41) | 2.75 (1.81, 3.49) | 0.001 |

| φ | 0.61 (0.58, 0.64) | 0.52 (0.49, 0.54) | 0.5663 (0.508, 0.63) | 0.016 |

| OFC | 15.03 (11.96, 18.02) | 13.17 (9.07, 12.46) | 14.1 (9.79, 17.49) | 0.08 |

| pυ | 48.59 (47.76, 50.31) | 52.02 (49.48, 56.48) | 50.31 (47.85, 53.51) | 0.06 |

All values are medians and interquartile range (IQR). P-values were calculated with the Kruskal-Wallis rank test. Control group: n=10; PAD group: n=10.

Figure 6 –

Plot of (a) intersititial permeability to fluid flow (Ktissue), (b) average transfer rate constant (kt), (c) average of porosity (φ) and (d) percentage of fibrosis (1-φ), (e) outflow filtration coefficient (OFC) and (f) average vascular pressure (pv) between PAD patients (n=10) and controls (n=10) for each muscle region.

3.5. Correlation of model parameters with patient characteristics

The ABI was significantly correlated with φ when averaged over controls and PAD patients (r = 0.64, p = 0.011). kt was significantly correlated with the ABI for controls (r = 0.94, p = 0.017) but not for PAD patients (r = −0.05, p = 0.88). kt was inversely correlated with hypertension (r = −0.89, p = 0.042) among controls but not for PAD patients (r = −0.1, p = 0.79). There was a trend for a positive correlation of Ktissue with age for controls and PAD patients (r = 0.41, p = 0.07) and also a trend with the ABI among controls (r = 0.86, p = 0.06). There was a trend for the correlation of pυ with the ABI among controls (r = 0.26, p = 0.67). All other correlations were not significant (Table 6).

Table 6 –

Correlation analyses for baseline characteristics and modeling parameters.

| Variable | Group | Obs | kt | Ktissue | φ | OFC | pv | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Control | r | 10 | 0.52 | −0.24 | 0.36 | 0.27 | 0.18 |

| p-value | 0.12 | 0.51 | 0.31 | 0.44 | 0.62 | |||

| PAD | r | 10 | −0.05 | −0.29 | −0.26 | 0.12 | −0.08 | |

| p-value | 0.89 | 0.43 | 0.46 | 0.74 | 0.83 | |||

| Average | r | 20 | 0.42 | 0.41 | −0.3 | 0.04 | 0.24 | |

| p-value | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.21 | 0.86 | 0.31 | |||

| Body mass index | Control | r | 10 | 0.06 | −0.16 | 0.03 | 0.18 | −0.03 |

| p-value | 0.86 | 0.67 | 0.95 | 0.62 | 0.93 | |||

| PAD | r | 10 | −0.14 | −0.13 | −0.15 | 0.12 | −0.02 | |

| p-value | 0.70 | 0.72 | 0.68 | 0.74 | 0.95 | |||

| Average | r | 20 | 0.10 | 0.17 | −0.24 | 0.09 | 0.08 | |

| p-value | 0.67 | 0.47 | 0.30 | 0.72 | 0.75 | |||

| Ankle brachial index (rest) | Control | r | 5 | 0.94 | 0.86 | 0.72 | 0.17 | 0.26 |

| p-value | 0.017 | 0.06 | 0.17 | 0.78 | 0.67 | |||

| PAD | r | 10 | −0.05 | 0.27 | 0.45 | −0.18 | −0.01 | |

| p-value | 0.88 | 0.45 | 0.19 | 0.61 | 0.97 | |||

| Average | r | 15 | −0.39 | −0.42 | 0.64 | 0.04 | −0.22 | |

| p-value | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.011 | 0.88 | 0.42 | |||

| Ankle brachial index (exercise) | Control | r | 5 | 0.33 | −0.28 | −0.31 | 0.82 | −0.69 |

| p-value | 0.58 | 0.64 | 0.61 | 0.09 | 0.19 | |||

| PAD | r | 7 | 0.22 | 0.72 | 0.57 | −0.44 | 0.15 | |

| p-value | 0.63 | 0.07 | 0.18 | 0.32 | 0.75 | |||

| Average | r | 12 | −0.3 | −0.36 | 0.72 | −0.18 | −0.28 | |

| p-value | 0.34 | 0.25 | 0.008 | 0.57 | 0.38 | |||

| Δ of Ankle brachial index | Control | r | 5 | −0.49 | −0.86 | −0.77 | 0.44 | −0.69 |

| p-value | 0.40 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.46 | 0.2 | |||

| PAD | r | 10 | 0.30 | 0.29 | −0.02 | 0.08 | 0.46 | |

| p-value | 0.40 | 0.42 | 0.95 | 0.82 | 0.18 | |||

| Average | r | 15 | −0.04 | −0.2 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.20 | |

| p-value | 0.89 | 0.48 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.48 | |||

| eGFR | Control | r | 5 | 0.13 | −0.04 | −0.07 | 0.20 | −0.09 |

| p-value | 0.84 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.75 | 0.89 | |||

| PAD | r | 10 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 0.39 | −0.15 | 0.45 | |

| p-value | 0.34 | 0.14 | 0.26 | 0.68 | 0.19 | |||

| Average | r | 15 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.33 | −0.11 | 0.38 | |

| p-value | 0.38 | 0.33 | 0.24 | 0.70 | 0.17 | |||

| Hypertension | Control | r | 5 | −0.89 | −0.65 | −0.44 | −0.35 | 0.02 |

| p-value | 0.042 | 0.23 | 0.46 | 0.56 | 0.97 | |||

| PAD | r | 10 | −0.10 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.16 | −0.02 | |

| p-value | 0.79 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.65 | 0.95 | |||

| Average | r | 15 | 0.15 | 0.43 | −0.32 | −0.08 | 0.16 | |

| p-value | 0.58 | 0.11 | 0.25 | 0.77 | 0.57 |

kt is the transfer rate constant; Ktissue is the interstitial permeability; φ is the porosity; OFC is the outflow filtration coefficient; pv is microvascular pressure.

eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate.

4. DISCUSSION

This study presents the simulation of CE-MRI signal intensity in five distinct calf muscle regions including the anterior, lateral, deep posterior, soleus and gastrocnemius muscles. This work (i) estimated and modelled transport properties in the calf muscles and (ii) compared tissue transport properties between PAD patients and controls. In this study kt was significantly higher in PAD patients compared to controls when analyzed over five calf muscles regions and across distinct muscle domains. The transfer rate could be higher in tissues with damaged cells and could have a higher accumulation of contrast agent due to ruptured cell membranes allowing the contrast agent to diffuse into the extracellular compartments (Maestrini et al. 2014). Tissue permeability was significantly higher in PAD patients compared to controls when analyzed over all muscles regions and across distinct muscle domains. On the other hand, the fraction of extracellular space (φ) was significantly lower in PAD patients compared to controls. Our results indicate that the fraction of extracellular space (φ) was heterogeneous across muscle groups for DM, SM and GM which could be due to differences in muscle fiber composition across leg muscles and an increase in connective tissue. Wu et al. (Wu et al. 2008) reported similar findings in a study of 24 controls indicating that heterogeneity of calf muscle perfusion could be attributed to differences in muscle fiber composition across leg compartments.

The differences in muscle fiber types may explain the differences of kt and Ktissue across muscle groups, as PAD is associated with muscle atrophy, a complex process that results in denervation and a decrease in type II (glycolytic) muscle fiber area (Regensteiner et al. 1993). Robbins et al. (Robbins et al. 2011) found an association of leg muscle capillary density and peak hyperemic blood flow in patients with lower extremity ischemia. These findings indicate that alterations in the microcirculation may contribute to functional impairment in PAD patients, which is in agreement with our results.

The average vascular pressure was higher and OFC was lower in PAD patients compared to controls when analyzed over all the muscles regions. Our results indicate that MVP and OFC were heterogeneous across muscle regions, while the CFC was not sensitive with respect to different muscle regions. Bentzer et. al (Bentzer, Kongstad and Grande 2001) reported similar findings suggesting that the CFC is independent of perfused capillaries in skeletal muscle of a feline model.

Our work is among the first to report on a compuational microvascular model in peripheral artery disease and cardiovascular diseases. This study indicates the potential of numerical CFD simulations which exhibit significant differences between controls and PAD patients and to model blood flow parameters in the leg muscles with different degrees of ischemia and tissue fibrosis.

Limitations:

We assumed a finite element model of muscle blood perfusion to describe the exchange between blood plasma and interstitial space. In our simulation, we did not include nonlinear reaction. Blood was assumed as a Newtonian fluid. In addition, physical interactions and leaks between muscle groups were ignored. The proposed micovascular perfusion model could be modified by including interaction terms between the various calf muscle groups. The complexity of muscle blood perfusion was reduced to a selected set of parameters including the geometry of muscle domains, density, dynamic viscosity and tissue porosity, permeability to fluid flow, outflow filtration coefficient, microvascular and osmotic pressure.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated blood perfusion through porous muscles using computational fluid dynamics. The simulation data are in excellent agreement and yield a result with a minimal average deviation from the experimental data, suggesting a reasonable validity and reproducibility of the proposed computational microvascular model in PAD patients and controls. Calf muscle transport properties including kt, φ, Ktissue, pv and OFC exhibit significant differences between PAD patients and controls.

Supplementary Material

Appendix A. Porous Media Model

Supplementary Figure 2 – Plot of (a) intersititial permeability to fluid flow (Ktissue), (b) average transfer rate constant (kt), (c) average of porosity (φ) and (d) percentage of fibrosis (1-φ), (e) outflow filtration coefficient (OFC) and (f) average vascular pressure (pv) between PAD patients (n=10) and controls (n=10).

Supplementary Figure 1 – Plot of simulated (sim): dashed lines and experimental (exp, obtained from CE-MRI scans): solid lines mean signal intensity of a control patient (a) and a PAD patient (b) for each muscle region (AM, LM, DM, SM, GM). Mean square error (MSE) and mean abosolute percentage error (MAPE) were less than 5 %.

Supplementary Table 1 – Estimated parameters from the training data (Control group: n=10; PAD group: n=10).

Supplementary Table 2 – Modelling parameters.

Acknowledgments

Funding: We thank all study participants. This work was supported by American Heart Association (AHA) Beginning Grant-in-Aid award (13BGIA16720014, to GB), the Methodist DeBakey Heart Research Award (to DJS), and National Institutes of Health (NIH) awards R01HL137763 (to GB) and K25HL121149 (to GB).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: None (OG), none (JS), none (GB), none (DS).

Reference

- Bentzer P, Kongstad L & Grande PO (2001) Capillary filtration coefficient is independent of number of perfused capillaries in cat skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 280, H2697–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfiglio A, Leungchavaphongse K, Repetto R & Siggers JH (2010) Mathematical modeling of the circulation in the liver lobule. J Biomech Eng, 132, 111011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouillard K, Nordez A & Hug F (2011) Estimation of individual muscle force using elastography. PLoS One, 6, e29261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouillot P, Brina O, Ouared R, Lovblad KO, Farhat M & Pereira VM (2015) Hemodynamic transition driven by stent porosity in sidewall aneurysms. J Biomech, 48, 1300–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd J, Buick JM & Green S (2007) Analysis of the Casson and Carreau-Yasuda Non-Newtonian Blood Models in Steady and Oscillatory Flows Using the Lattice Boltzmann Method. Physics of Fluids, 19, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner G, Bismuth J, Nambi V, Ballantyne CM, Taylor AA, Lumsden AB, Morrisett JD & Shah DJ (2016) Calf muscle perfusion as measured with magnetic resonance imaging to assess peripheral arterial disease. Med Biol Eng Comput, 54, 1667–1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner G, Yang EY, Kumar A, Sun W, Virani SS, Negi SI, Murray T, Lin PH, Hoogeveen RC, Chen C, Dong J-F, Kougias P, Taylor A, Lumsden AB, Nambi V, Ballantyne CM & Morrisett JD (2013) The Effect of Lipid Modification on Peripheral Artery Disease after Endovascular Intervention Trial (ELIMIT). Atherosclerosis, 231, 371–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carod-Artal FJ, Ferreira Coral L, Stieven Trizotto D & Menezes Moreira C (2009) Self- and proxy-report agreement on the Stroke Impact Scale. Stroke, 40, 3308–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cibis M, Potters WV, Selwaness M, Gijsen FJ, Franco OH, Arias Lorza AM, de Bruijne M, Hofman A, van der Lugt A, Nederveen AJ & Wentzel JJ (2016) Relation between wall shear stress and carotid artery wall thickening MRI versus CFD. J Biomech, 49, 735–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J 1988. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Criqui MH & Aboyans V (2015) Epidemiology of peripheral artery disease. Circ Res, 116, 1509–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson LE, Kelley DE, Heshka S, Thornton J, Pi-Sunyer FX, Boxt L, Balasubramanyam A, Gallagher D & M. R. I. A. S. S. o. t. L. A. R. Group (2014) Skeletal muscle and organ masses differ in overweight adults with type 2 diabetes. J Appl Physiol (1985), 117, 377–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debbaut C, Monbaliu D, Casteleyn C, Cornillie P, Van Loo D, Masschaele B, Pirenne J, Simoens P, Van Hoorebeke L & Segers P (2011) From vascular corrosion cast to electrical analog model for the study of human liver hemodynamics and perfusion. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng, 58, 25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debbaut C, Vierendeels J, Casteleyn C, Cornillie P, Van Loo D, Simoens P, Van Hoorebeke L, Monbaliu D & Segers P (2012) Perfusion characteristics of the human hepatic microcirculation based on three-dimensional reconstructions and computational fluid dynamic analysis. J Biomech Eng, 134, 011003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich O, Biffar A, Baur-Melnyk A & Reiser MF (2010) Technical aspects of MR diffusion imaging of the body. Eur J Radiol, 76, 314–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubuis L, Avril S, Debayle J & Badel P (2012) Identification of the material parameters of soft tissues in the compressed leg. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin, 15, 3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowkes FG, Rudan D, Rudan I, Aboyans V, Denenberg JO, McDermott MM, Norman PE, Sampson UK, Williams LJ, Mensah GA & Criqui MH (2013) Comparison of global estimates of prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2000 and 2010: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet, 382, 1329–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frauziols F, Rohan PY, Badel P, Avril S, Molimard J & Navarro L (2013) Patient-specific modelling of the calf muscle under elastic compression using magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound elastography. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin, 16 Suppl 1, 332–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner AW & Afaq A (2008) Management of lower extremity peripheral arterial disease. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev, 28, 349–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grishina OA, Kirillova IV & Glukhova OE (2016) Biomechanical rationale of coronary artery bypass grafting of multivessel disease. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin, 19, 297–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldin CH, Rubin K, Pietras K & Ostman A (2004) High interstitial fluid pressure - an obstacle in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer, 4, 806–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinghofer-Szalkay H & Greenleaf JE (1987) Continuous monitoring of blood volume changes in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985), 63, 1003–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook J, Belousova T, Short CM, Taylor AA, Nambi V, Morrisett JD, Ballantyne CM, Bismuth J, Shah DJ & Brunner G (2016) Magnetic Resonance Imaging Based Arterial Signal Enhancement is Associated with Markers of Peripheral Artery Disease. Circulation, 134, A16715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain SS, Zhang Y, Fu X, Brunner G, Singh J, Hughes TJ, Shah D & Decuzzi P (2015) Magnetic resonance imaging-based computational modelling of blood flow and nanomedicine deposition in patients with peripheral arterial disease. J R Soc Interface, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javadzadegan A, Moshfegh A, Qian Y, Kritharides L & Yong ASC (2019) Myocardial bridging and endothelial dysfunction - Computational fluid dynamics study. J Biomech, 85, 92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston BM, Johnston PR, Corney S & Kilpatrick D (2006) Non-Newtonian blood flow in human right coronary arteries: transient simulations. J Biomech, 39, 1116–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamran H, Nambi V, Negi S, Yang EY, Chen C, Virani SS, Kougias P, Lumsden AB, Morrisett JD, Ballantyne CM & Brunner G (2016) Magnetic Resonance Venous Volume Measurements in Peripheral Artery Disease (from ELIMIT). Am J Cardiol, 118, 1399–1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenner T (1989) The measurement of blood density and its meaning. Basic Res Cardiol, 84, 111–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer CM (2008) Skeletal muscle perfusion in peripheral arterial disease a novel end point for cardiovascular imaging. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging, 1, 351–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong HT, Ng GY, Leung VY & Fu SN (2013) Quantitative estimation of muscle shear elastic modulus of the upper trapezius with supersonic shear imaging during arm positioning. PLoS One, 8, e67199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim GB (2013) Vascular disease: Peripheral artery disease pandemic. Nat Rev Cardiol, 10, 552–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestrini V, Treibel TA, White SK, Fontana M & Moon JC (2014) T1 Mapping for Characterization of Intracellular and Extracellular Myocardial Diseases in Heart Failure. Curr Cardiovasc Imaging Rep, 7, 9287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MathWorks T 2012. MATLAB, and Statistics Toolbox 2012b Natick. Massachusetts, United States. [Google Scholar]

- Newman AB, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Rutan GH, Locher J & Kuller LH (1991) Lower extremity arterial disease in elderly subjects with systolic hypertension. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 44, 15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps EA & Garcia AJ (2009) Update on therapeutic vascularization strategies. Regen Med, 4, 65–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pishko GL, Astary GW, Mareci TH & Sarntinoranont M (2011) Sensitivity Analysis of an Image-Based Solid Tumor Computational Model with Heterogeneous Vasculature and Porosity. Annals of Biomedical Engineering, 39, 2360–2373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pishko GL, Astary GW, Zhang J, Mareci TH & Sarntinoranont M (2012) Role of convection and diffusion on DCE-MRI parameters in low leakiness KHT sarcomas. Microvascular Research, 84, 306–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rani HP, Sheu TW, Chang TM & Liang PC (2006) Numerical investigation of non-Newtonian microcirculatory blood flow in hepatic lobule. J Biomech, 39, 551–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regensteiner JG, Wolfel EE, Brass EP, Carry MR, Ringel SP, Hargarten ME, Stamm ER & Hiatt WR (1993) Chronic changes in skeletal muscle histology and function in peripheral arterial disease. Circulation, 87, 413–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren J, Sherry AD, Malloy CR (2015) A simple approach to evaluate the kinetic rate constant for ATP synthesis in resting human skeletal muscle at 7 T. NMR Biomed, 29, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rippe B, Townsley M, Parker JC & Taylor AE (1985) Osmotic reflection coefficient for total plasma protein in lung microvessels. J Appl Physiol (1985), 58, 436–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins JL, Jones WS, Duscha BD, Allen JD, Kraus WE, Regensteiner JG, Hiatt WR & Annex BH (2011) Relationship between leg muscle capillary density and peak hyperemic blood flow with endurance capacity in peripheral artery disease. J Appl Physiol, 111, 81–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE & Fleiss JL (1979) Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull, 86, 420–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siggers JH, Leungchavaphongse K, Ho CH & Repetto R (2014) Mathematical model of blood and interstitial flow and lymph production in the liver. Biomech Model Mechanobiol, 13, 363–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva JA, White CJ, Quintana H, Collins TJ, Jenkins JS & Ramee SR (2004) Percutaneous revascularization of the common femoral artery for limb ischemia. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv, 62, 230–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh J, Brunner G, Morrisett JD, Ballantyne CM, Lumsden AB, Shah DJ & Decuzzi P (2018) Patient-Specific Flow Descriptors and Normalized wall index in Peripheral Artery Disease: a Preliminary Study. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Eng Imaging Vis, 6, 119–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smye SW, Evans CJ, Robinson MP & Sleeman BD (2007) Modelling the electrical properties of tissue as a porous medium. Phys Med Biol, 52, 7007–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoner M, Defreitas D, Manwaring M & et al. (2008) Cost per day of patency: understanding the impact of patency and reintervention in a sustainable model of healthcare. J Vasc Surg., 48(6), 1489–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stylianopoulos T & Jain RK (2013) Combining two strategies to improve perfusion and drug delivery in solid tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 110, 18632–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RB, Aviles RJ, Faranesh AZ, Raman VK, Wright V, Balaban RS, McVeigh ER & Lederman RJ (2005) Measurement of skeletal muscle perfusion during postischemic reactive hyperemia using contrast-enhanced MRI with a step-input function. Magn Reson Med, 54, 289–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofts PS & Kermode AG (1991) Measurement of the blood-brain barrier permeability and leakage space using dynamic MR imaging. 1. Fundamental concepts. Magn Reson Med, 17, 357–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Plaats A, t Hart NA, Verkerke GJ, Leuvenink HG, Verdonck P, Ploeg RJ & Rakhorst G (2004) Numerical simulation of the hepatic circulation. Int J Artif Organs, 27, 222–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vankan WJ, Huyghe JM, van Donkelaar CC, Drost MR, Janssen JD & Huson A (1998) Mechanical blood-tissue interaction in contracting muscles: a model study. J Biomech, 31, 401–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu WC, Wang J, Detre JA, Wehrli FW, Mohler E 3rd, Ratcliffe SJ & Floyd TF (2008) Hyperemic flow heterogeneity within the calf, foot, and forearm measured with continuous arterial spin labeling MRI. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 294, H2129–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang EY, Brunner G, Dokainish H, Hartley CJ, Taffet G, Lakkis N, Taylor AA, Misra A, McCulloch ML, Morrisett JD, Virani SS, Ballantyne CM, Nagueh SF & Nambi V (2013) Application of speckle-tracking in the evaluation of carotid artery function in subjects with hypertension and diabetes. J Am Soc Echocardiogr, 26, 901–909 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Liu X, Sun A, Fan Y & Deng X (2015) Hemodynamic insight into overlapping bare-metal stents strategy in the treatment of aortic aneurysm. J Biomech, 48, 2041–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao F, van Rietbergen B, Ito K & Hofmann S (2018) Flow rates in perfusion bioreactors to maximise mineralisation in bone tissue engineering in vitro. J Biomech, 79, 232–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix A. Porous Media Model

Supplementary Figure 2 – Plot of (a) intersititial permeability to fluid flow (Ktissue), (b) average transfer rate constant (kt), (c) average of porosity (φ) and (d) percentage of fibrosis (1-φ), (e) outflow filtration coefficient (OFC) and (f) average vascular pressure (pv) between PAD patients (n=10) and controls (n=10).

Supplementary Figure 1 – Plot of simulated (sim): dashed lines and experimental (exp, obtained from CE-MRI scans): solid lines mean signal intensity of a control patient (a) and a PAD patient (b) for each muscle region (AM, LM, DM, SM, GM). Mean square error (MSE) and mean abosolute percentage error (MAPE) were less than 5 %.

Supplementary Table 1 – Estimated parameters from the training data (Control group: n=10; PAD group: n=10).

Supplementary Table 2 – Modelling parameters.