Abstract

Background

The mainstay of treatment of IgE‐mediated cow milk allergy (IMCMA) is an avoidance diet, which is especially difficult with a ubiquitous food like milk. Milk oral immunotherapy (MOIT) may be an alternative treatment, through desensitization or induction of tolerance.

Objectives

We aim to assess the clinical efficacy and safety of MOIT in children and adults with IMCMA as compared to a placebo treatment or avoidance strategy.

Search methods

We searched 13 databases for journal articles, conference proceedings, theses and unpublished trials, without language or date restrictions, using a combination of subject headings and text words. The search is up‐to‐date as of October 1, 2012.

Selection criteria

Only randomised controlled trials (RCT) were considered for inclusion. Blinded and open trial designs were included. Children and adults with IMCMA were included. MOIT administered by any protocol were included.

Data collection and analysis

A total of 2111 unique records were identified and screened for potential inclusion. Studies were selected, data extracted and methodological quality assessed independently by two reviewers. We attempted to contact the study investigators to inquire about data not published that was required for the analysis. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the I² test. We estimated a pooled risk ratio (RR) for each outcome using a Mantel‐Haenzel fixed‐effect model if statistical heterogeneity was low as evaluated by an I² value less than 50%.

Main results

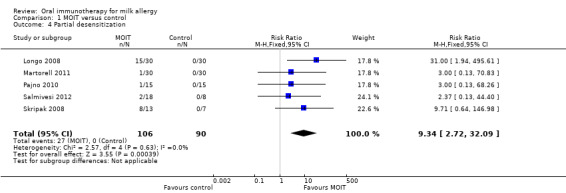

Of 157 records reviewed, 16 were included, representing five trials. In general, the studies were small and had inconsistent methodological rigor. Overall, the quality of evidence was rated as low. Each study used a different MOIT protocol. A total of 196 patients were studied (106 MOIT, 90 control) and all were children. Three studies were blinded and two used an avoidance diet control. Sixty‐six patients (62%) in the MOIT group were able to tolerate a full serving of milk (about 200 mL) compared to seven (8%) of the control group (RR 6.61, 95% CI 3.51 to 12.44). In addition, 27 (25%) in the MOIT group could ingest a partial serving of milk (10 to 184 mL) while none could in the control group (RR 9.34, 95% CI 2.72 to 32.09). None of the studies assessed the patients following a period off immunotherapy. Adverse reactions were common (97 of 106 MOIT patients had at least one symptom), although most were local and mild. Because of variability in reporting methods, adverse effects could not be combined quantitatively. For every 11 patients receiving MOIT, one required intramuscular epinephrine. One patient required it on two occasions.

Authors' conclusions

Studies to date have involved small numbers of patients and the quality of evidence is generally low. The current evidence shows that MOIT can lead to desensitization in the majority of individuals with IMCMA although the development of long‐term tolerance has not been established. A major drawback of MOIT is the frequency of adverse effects, although most are mild and self‐limited. The use of parenteral epinephrine is not infrequent. Because there are no standardized protocols, guidelines would be required prior to incorporating desensitization into clinical practice.

Keywords: Adult; Animals; Child; Humans; Administration, Oral; Desensitization, Immunologic; Desensitization, Immunologic/adverse effects; Desensitization, Immunologic/methods; Milk; Milk/adverse effects; Milk/immunology; Milk Hypersensitivity; Milk Hypersensitivity/immunology; Milk Hypersensitivity/therapy; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Repetitive, increasing doses of daily milk for treatment of milk allergy

To date, the only option to treat food allergy is strict avoidance of the food and carrying an epinephrine injector (Epipen/Twinject) in case of an allergic reaction. For a food like cow's milk, avoidance is very difficult because it is found in many foods. The constant fear of accidentally eating or drinking cow's milk and anxiety related to carrying an injector has negative effects on quality of life. Accidentally having milk can cause life‐threatening reactions. Oral immunotherapy involves initially taking a very small amount of the allergen, in the case of milk allergy, cow's milk, and slowly increasing the amount each day until a full serving is reached. This may change the way the body's immune system sees the allergen, thereby increasing the amount of milk that can be eaten or drunk with no reaction.

We identified randomized controlled trials that compared oral immunotherapy to placebo or continued avoidance diet in children and adults with cow's milk allergy. Five studies satisfied our inclusion criteria. In total there were 196 participants (106 in the treatment group and 90 in the control), all of whom were children. In general, the quality of the studies was low.

Because the trials involved small numbers and there were problems with the way they were done, further research is needed. The current evidence shows that oral immunotherapy can help a majority of allergic children tolerate a full serving of milk, as long as they continue drinking this amount each day. However, it is not known if this protection is continued if the immunotherapy is stopped for some time. Side effects during oral immunotherapy are frequent and most patients will have at least some mild symptoms. In the studies we included, for every 11 patients who received oral immunotherapy, one needed to be treated with epinephrine injection at some point for a serious allergic reaction to the therapy.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Oral immunotherapy for milk allergy.

| Oral immunotherapy for milk allergy | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with milk allergy Settings: healthcare institutions Intervention: oral immunotherapy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Oral immunotherapy | |||||

| Full desensitization to milk Follow‐up: 18 to 52 weeks | 78 per 10001 | 514 per 1000 (273 to 968) | RR 6.61 (3.51 to 12.44) | 196 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Baseline risk calculated as mean risk in control group 2 All studies at high or unclear risk of bias in at least one domain 3 Small number of studies and included participants, in total 73 participants acheived desensitisation (>300 events in total)

Background

Description of the condition

An immunoglobulin E (IgE)‐mediated cow milk allergy (IMCMA) causes the immediate onset of a constellation of symptoms following exposure to often a small quantity. Physical manifestations can range from mild local pruritus, urticaria and abdominal discomfort to respiratory distress and cardiovascular collapse (Boyce 2010). Those affected are required to diligently avoid milk in the diet and are expected to have a reaction on subsequent exposures. There are also non‐IgE mediated reactions to milk that typically cause, among other symptoms, a delayed or insidious onset of gastrointestinal symptoms or worsening of atopic dermatitis (Boyce 2010). Carefully distinguishing between the two mechanisms is important and has major implications on management and prognosis. Non‐IgE mediated reactions are not the focus of this review.

Due to differences in diagnostic and follow‐up methods, it is difficult to know true prevalence rates and natural history of IMCMA with certainty. In two systematic reviews, the self‐reported milk allergy rate of 1.2 to 17 percent is much higher than the rates confirmed by sensitization tests or challenge confirmed allergy, which are 0.6 to 3 percent (Chafen 2010; Rona 2007). A birth cohort in Denmark followed for development of IMCMA and found an incidence of 1.2% (Host 2002). In the past, the prognosis of IMCMA was thought to be excellent, with resolution reported in 80% or more patients by six years of age (Bishop 1990; Host 1990). However, more recent studies have shown less reassuring results, not achieving these high rates of recovery until later childhood (Host 2002; Saarinen 2005). Skripak 2007 found that only 19% of IMCMA affected children outgrew their allergy by age four, although tolerance continued to be gradually achieved into adolescence, with 79% tolerant at 16 years.

Description of the intervention

Oral immunotherapy has been explored as a therapeutic alternative to the traditional elimination diet (Bauer 1999; Patriarca 1998; Patriarca 2003). It involves the introduction of a very small amount of cow’s milk protein and gradual increases of the dose at predetermined intervals. Generally, the target dose is chosen to approximate an age‐appropriate portion in a normal diet.

How the intervention might work

The complexities of immunotherapy are not completely understood. In animal models, induction of oral tolerance seems to result from suppression of both Th1 and Th2 responses (Mizumachi 2002), induction of anergy of responsible cells, and activation of regulatory T cells (Smith 2000). In human studies, it has been observed that specific IgE decreases, and specific IgG4 (immunoglobulin G4) increases with immunotherapy (Patriarca 2003); although whether this is mechanistically relevant, or solely an epiphenomenon, has not been fully resolved.

It is unclear whether oral immunotherapy enables a state of true tolerance or mere desensitization, as defined by The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases‐sponsored Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Food Allergy (Boyce 2010). Desensitization refers to symptom‐free consumption of the food with the requirement that regular ingestion be continued. Tolerance is achieved if the patient can still safely consume the food following cessation of treatment and a period without ingestion, namely weeks to months. Many experts currently recommend continued daily ingestion of the full portion because of this uncertainty (Meglio 2008; Niggemann 2006; Rolinck‐Werninghaus 2005; Zapatero 2008).

Why it is important to do this review

Currently, the mainstay of treatment for CMA is an avoidance diet. However, because milk is ubiquitous in store‐bought foods, and in home and restaurant recipes, it is especially difficult to avoid (Taylor 2010). Despite efforts to comply with this diet, accidental exposures leading to adverse reactions are frequent (Boyano‐Martinez 2009). A US registry of fatalities caused by food‐induced anaphylaxis over five years reported four cases where milk was the culprit (Bock 2007). Of note, these were all outside early childhood and three cases occurred at home. A similar report from the UK described milk responsible in six of 48 deaths over seven years (Pumphrey 2007). It appeared that most of these deaths occurred in people with known food allergy.

Milk elimination also carries with it nutritional consequences. Alternatives, such as hydrolyzed formulas and soy substitutes can be expensive and are less readily available. Most children are also recommended to carry an epinephrine auto‐injector at all times (Allen 2009). This responsibility, in combination with dietary avoidance, has a deleterious effect on quality of life for both the child and the caregiver (MacKenzie 2010; Springston 2010).

Oral immunotherapy has the potential to greatly increase the safety margin and to eliminate the fear of accidental ingestion.

A meta‐analysis on specific oral tolerance induction in children identified three randomised controlled trials on milk oral immunotherapy (MOIT) up until July 2009 (Fisher 2011). There was a lower risk ratio of allergy following immunotherapy, but this was not statistically significant. More recently, a systematic review of MOIT showed a benefit, but adverse reactions were frequent (Brozek 2012). Because of the increasing interest on this topic and emerging studies, it is important to provide an up‐to‐date systematic review with ongoing updates. In addition, broader review of the available data, including grey literature and studies published in other languages, may retrieve a greater number of relevant studies and minimize publication bias.

Objectives

To assess the clinical efficacy and safety of MOIT in children and adults with IMCMA as compared to a placebo treatment or avoidance.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Only randomized controlled trials (RCT) were considered for inclusion. Blinded and open trial designs were included.

Studies were not limited by language or date of publication.

Types of participants

Children and adults who have been diagnosed with an IMCMA were included. IMCMA should be diagnosed by either: 1) a history and one of a positive skin‐prick test (SPT) or specific IgE, or 2) a positive open challenge or double‐blind, placebo‐controlled food challenge (DBPCFC). The positive reaction, either on history or following challenge, should be immediate‐onset with symptoms suggestive of an IgE‐mediated mechanism, such as urticaria, angioedema, vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, lightheadedness and/or syncope.

Ideally, investigators would perform a pre‐treatment DBPCFC to confirm the diagnosis. However, studies that rely on previous diagnoses made using the aforementioned criteria were also included.

Types of interventions

MOIT administered by any protocol were included. MOIT entails introduction of milk allergen by incremental doses at defined intervals, over a period of time. Study comparators included placebo and continued avoidance diet with or without carriage of an epinephrine auto‐injector. Studies with co‐interventions, such as nutritional education and pharmacological treatment, were considered for inclusion. Where studies involved a pharmacological co‐intervention, a subgroup analysis was conducted to assess their impact on the primary outcome. Studies of sublingual immunotherapy were also considered for inclusion, although (if found) the results would be analysed separately.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome was successful desensitization: the ability to ingest a serving of cow’s milk (200 mL) without adverse reactions while on therapy or continued daily ingestion. Studies using a slightly smaller volume as their endpoint were also considered.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes included:

1. Tolerance achieved: ability to ingest a serving of cow's milk without adverse reactions after four weeks, or more, of stopping treatment

2. Ability to ingest a partial serving of cow’s milk without adverse reactions (10 to 199 mL). Ingestion of higher quantities would lead to an adverse reaction

3. Severe allergic reactions (respiratory compromise or circulatory collapse)

4. Mild to moderate adverse reactions (rash, gastrointestinal symptoms)

5. Change in skin‐prick test size, specific IgE level, specific IgG4 level

Data was analysed on an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) basis whenever possible.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Several biomedical databases indexing journal articles (MEDLINE, EMBASE, BIOSIS Previews, LILACS) were searched. In addition, conference papers (Conference Papers Index, Conference Proceedings Citation Index Science), Master’s and doctoral theses (ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, Foreign Doctoral Dissertations), the Cochrane Central Registry of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and the U.S. National Library of Medicine’s registry, ClinicalTrials.gov, were searched to identify unpublished or incomplete studies. A complete list of databases searched is included in Appendix 1. The search is up‐to‐date as of October 1, 2012.

The computerized bibliographic database search retrieved all publications which contain terms corresponding to the two main concepts of this review: cow’s milk allergy (CMA) and oral immunotherapy (OIT). Search terms were generated through discussions with team members, reference to published systematic reviews, and in consultation of subject thesauri (e.g. Medical Subject Headings [MeSH], EMTREE). The MEDLINE search strategy has undergone peer review (Sampson 2009). Search terms were adapted for databases other than MEDLINE and corresponding subject headings were used whenever possible. To restrict the results to randomised controlled trials, the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for MEDLINE (Glanville 2006) and a similar strategy for EMBASE (Wong 2006) were used. The complete MEDLINE search strategy appears in Appendix 2. We adapted the strategy for each database. The precise search strategies used in other databases are available from the authors.

Searching other resources

Grey literature was searched through Google Scholar (http://www.scholar.google.ca) and the New York Academy of Medicine’s Grey Literature Report (http://www.nyam.org/library/pages/grey_literature_report). The proceedings of conferences important to allergy and immunology, and not included in the electronic databases, were also searched. Key articles retrieved from the electronic database searches (including seminal research studies and review articles) were used to conduct citation searches in Web of Science and Scopus. Key authors on the topic of oral immunotherapy for cow's milk allergy, identified by the research team, were identified and contacted for information about current research and in‐press manuscripts for potential inclusion in the systematic review.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Titles and abstracts of records retrieved were screened by one author and irrelevant records excluded. Full text reports of potentially relevant studies were retrieved. Multiple reports from the same study were identified and grouped under a single study identifier. Examination of these studies and selection based on the eligibility criteria were undertaken by two authors, independently. When required, study investigators were contacted to clarify eligibility. When the two authors did not agree on inclusion of a study even following discussion, a third author acted as an arbiter.

Data extraction and management

A data collection form was created and included the following items: trial characteristics (setting, MOIT regimen, eligibility criteria); methodological quality (randomization, blinding, selective reporting); patient characteristics; results and outcomes. It was piloted using two sample studies. Data extraction was undertaken by two authors independently. Correspondence with study investigators was required when not all information was available from reports. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved with discussion and arbitration by a third author was not necessary.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias was used by two authors, independently, to evaluate each included study. We considered the following types of potential bias: selection bias (adequacy of randomisation and allocation concealment); performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel); detection bias (blinding of outcome assessors) and attrition bias (loss to follow‐up). Sensitivity analyses were planned to determine the influence of the studies with a high risk of bias on the meta‐analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

The outcomes were collected and analysed as dichotomous data, e.g., presence or absence of tolerance, partial tolerance, adverse effects. The effect measure of choice was the risk ratio.

Unit of analysis issues

We did not anticipate that with this particular intervention we would likely come across unit of analysis issues. For example, cross‐over trials would not be a rational approach to assessing immunotherapy as the goal of treatment is to induce tolerance, and a patient would not be able to serve as his own control if his immune responses has been altered. We also did not expect large numbers of milk‐allergic patients to arise from various cohorts, and so cluster‐randomisation was unlikely to be encountered.

Dealing with missing data

We attempted to contact study investigators and request missing data. When possible, missing data was classified as random and non‐random. If it had been necessary, for the non‐random missing data, we planned to input replacement data based on reasonable clinical assumptions. However, this was not required as there was no data missing needed for the meta‐analysis. Data was analysed on an intention‐to‐treat basis whenever possible.

Where participants were lost to follow‐up, we used a conservative approach, assuming the dropouts assigned to the treatment group had no events (outcomes) and the dropouts assigned to the placebo group had the event. We conducted a sensitivity analysis to check if assumptions regarding participants lost to follow‐up changed the results.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We anticipated that there would be clinical heterogeneity in the studies, including different ages of the study population and differences in immunotherapy protocol. However, we felt that these studies could be analysed together despite these differences to examine the principle of whether oral immunotherapy is efficacious. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the I² test with a value greater than 50% considered to imply substantial heterogeneity. The I² test is chosen instead of Chi² because it tends to be more reliable, especially with fewer studies.

Assessment of reporting biases

We had planned to create a funnel plot to assess whether asymmetry was indicative of possible publication or other types of bias. However, as we included less than ten studies, we were unable to do so.

Data synthesis

We estimated a pooled risk ratio for each outcome, where possible, using a Mantel‐Haenzel fixed‐effect model if statistical heterogeneity was low as evaluated by an I² value less than 50%. If heterogeneity was higher and there was no obvious source of clinical heterogeneity we would consider reporting a random effects estimate, but this would be interpreted with caution, especially if the estimated effect was larger using a random effects model (Higgins 2011; Cochrane Handbook Section 9.5.4).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Depending on the data available, we planned to undertake subgroup analyses for presence of asthma, other food allergies, and history of previous anaphylaxis. We conducted a subgroup analysis based on age (patients four years and older).

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were performed for studies reviewed that are deemed at high risk of bias.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The electronic databases searches resulted in 2386 records retrieved (Figure 1). An additional five records were located by hand searching. After removing duplications, 2111 records remained. These were screened by a review author and 1954 records were excluded based on title and abstract information. Full‐text articles for the remaining 157 records were then retrieved. For conference abstracts and trial registries, all available information was included in a citation database along with full‐text articles. These records were then assessed for eligibility by two authors independently. If there was insufficient information with which to assess eligibility, the authors were contacted. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

1.

Results from searching for studies for inclusion in the review

Included studies

Five RCTs published in 16 records between 2008 and 2012 were identified which satisfied the inclusion criteria. The methods, participants, interventions and outcomes of included studies are listed in the Characteristics of included studies table. A total of 196 patients were involved (106 MOIT, 90 controls). All patients were children, with ages ranging from 2 to 17 years. Three studies used a placebo control (Pajno 2010; Salmivesi 2012; Skripak 2008), whereas two use a continued avoidance diet as the control (Longo 2008; Martorell 2011). One trial studied young children between 24 to 36 months specifically (Martorell 2011), whereas the rest excluded this group of patients, and chose a minimum age of 4 to 6 years. One trial included only children with a history of anaphylaxis to milk (Longo 2008), while two excluded patients with a history of severe anaphylaxis (Martorell 2011; Skripak 2008), and two studies included patients with any degree of reaction (Pajno 2010; Salmivesi 2012). Finally, one trial (Longo 2008) administered a co‐intervention, an antihistamine, while the other studies had no pharmacological co‐intervention.

Although milk oral immunotherapy (MOIT) protocols differed between each study, which was anticipated, all but one of them (Salmivesi 2012) involved a build‐up phase in an institution (hospital, clinic, or research centre) followed by periodic up‐dosing (either in clinic or at home) and maintenance at home. The Salmivesi 2012 protocol involved daily up‐dosing with observation in the clinic on the first day, then periodically on 9 days over 78 days. Otherwise, up‐dosing occurred at home with telephone support 24 hours a day. The term "rush protocol" has been used to refer to a rapid build‐up phase with frequent dosing, but there is no set criteria or definition. Therefore, it is difficult to describe which studies used a "rush protocol". The time to reach about 2 mL of cow milk can be used to compare the rate of build‐up: two days in one study (Martorell 2011), by seven days in two studies (Longo 2008; Skripak 2008), by six weeks in one study (Salmivesi 2012), and by 11 weeks in the last (Pajno 2010). Target maintenance dose was the desired full serving (150 to 200 mL) in all studies except one, which used a maintenance dose of 15 mL for 13 weeks (Skripak 2008).

Although the Salmivesi 2012 trial used a placebo control and double‐blinding, the primary outcome measure was not assessed in the placebo group following treatment. Rather than performing a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled food challenge (DBPCFC) or open food challenge at the end of treatment, it was assumed by the study authors that there was no change from baseline in the amount of milk tolerated by those in the placebo group. Although we included this study in the meta‐analysis initially with some reservation, a sensitivity analysis showed its inclusion did not affect the overall result and conclusions.

The follow‐up period varied for each study, ranging from 18 ( Pajno 2010), 21 (Skripak 2008), and 25 ( Salmivesi 2012) weeks from the start of study, to one year (Longo 2008, Martorell 2011). All patients were on daily maintenance at the time of follow‐up.

There was one other record that met inclusion criteria, a registered clinical trial that is currently ongoing (Katsunuma 2012). This study will be reassessed for eligibility once completed as part of future updates.

Excluded studies

Following screening, we excluded a further 140 records representing 120 unique reports and two exact duplicates. Thirty‐nine records were in fact not original research (e.g. editorials, reviews). Of the 81 studies that remained, the reasons for exclusion were: not randomized controlled trials (71), comparison not placebo or continued avoidance diet (4), not enough information to assess eligibility (1), an abstract book that was indexed in the Conferences Papers index and searched (1), not human research (1), not oral immunotherapy (1), not IMCMA (1), and combined data for egg and CM allergy (separate data not available) (1). Further details can be found in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

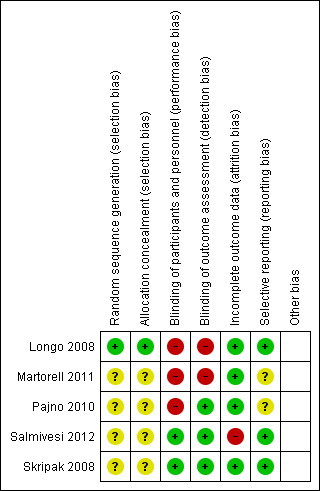

Risk of bias in included studies

Judgements are summarized in Figure 2. Although some studies had a high risk of bias in one or more domains, sensitivity analyses did not show that any one of the studies had a major influence on the estimate of treatment effect.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Allocation

A description of an adequately generated allocation sequence and adequately concealed allocation was provided in only one of the studies (Longo 2008). The other four studies did not provide this information in the text. Further information was sought from the authors, but none was provided.

Blinding

Blinding of the participants and investigators was attempted in three of the studies (Pajno 2010, Salmivesi 2012, Skripak 2008). Unfortunately, the blinding was likely broken in the Pajno 2010 study because the patients recognized the taste of the soy milk placebo, as reported by the authors (unpublished information). Thus, there is a risk of performance bias, but the outcome assessors remained blinded. The other two studies (Longo 2008; Martorell 2011) used continued dietary avoidance as the control, to which clearly the patients could not be blinded.

Incomplete outcome data

The greatest strength in quality across the board was that only one of the studies (Salmivesi 2012) had missing data. All dropouts were accounted for and the reasons for MOIT discontinuation were clearly described. As described above, the Salmivesi 2012 study did not assess the ability to ingest milk in the placebo group following therapy.

Selective reporting

Pre‐specified outcomes were available for three of the studies; two in the form of protocols (Skripak 2008; Salmivesi 2012) and the other stated within the text of the study report (Longo 2008). All three reported results on all their pre‐specified outcomes. Pre‐specified outcomes were sought from the authors of the other two studies, but no additional information was provided.

Other potential sources of bias

The studies appear free of other sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Desensitization

Each study conducted a DBPCFC at baseline to confirm a diagnosis of immunoglobulin E‐mediated cow milk allergy (IMCMA) in every patient, except Salmivesi 2012, which required that the patient have a positive open challenge or convincing reaction following an accidental exposure in the last six months. All five studies set out to assess the ability to tolerate a full portion of milk following MOIT and while still on daily therapy. The final volumes chosen by each study were 150 mL (Longo 2008), 200 mL (Martorell 2011; Pajno 2010; Salmivesi 2012), and 243 mL (equivalent to 8140 mg milk powder, Skripak 2008). For ease of comparison, the units of measurement used by Salmivesi 2012 and Skripak 2008 (mg of milk) have been converted to mL of milk for the remainder of the paper, given that 6400 mg is equivalent to 200 mL, and 500 mg is equivalent to 15 mL, respectively, as provided by the authors.

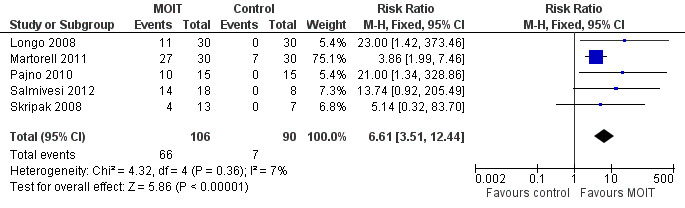

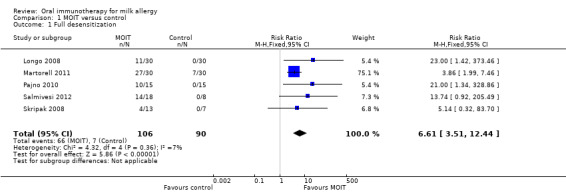

A total of 196 patients were quantitatively analysed (106 MOIT, 90 control). Sixty‐six (62%) of the patients receiving MOIT were able to tolerate a full serving of milk compared to seven (8%) of the control group, with a pooled relative risk (RR) of 6.61 (95% CI 3.51, 12.44, Figure 3, Analysis 1.1 ). In fact, all seven patients in the control group were from one study (Martorell 2011), which included only two‐year old children. Because we performed a conservative intention‐to‐treat analysis, the composition of these seven patients actually included three who passed the DBPCFC, three whose parents refused a re‐challenge, and one drop out. Because Salmivesi 2012 did not explicitly assess their placebo group for this outcome, we performed a sensitivity analysis to ensure that its inclusion did not affect the overall results (Table 2).

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 MOIT versus control, outcome: 1.1 Full desensitization.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 MOIT versus control, Outcome 1 Full desensitization.

1. Sensitivity analyses.

| Full desensitization | Partial desensitization | |

| All 5 studies | 6.61 [3.51, 12.44] | 9.34 [2.72, 32.09] |

| Excluding Salmivesi 2012 | 6.05 [3.20, 11.44] | 11.55 [2.85, 46.87] |

| Excluding Longo 2008 |

5.68 [2.98, 10.85] | 4.66 [1.08, 20.06] |

| Excluding Martorell 2011 |

14.94 [3.86, 57.90] | 10.71 [2.76, 41.49] |

| Excluding Pajno 2010 |

5.80 [3.03, 11.09] | 10.71 [2.76, 41.54] |

| Excluding Skripak 2008 |

6.72 [3.51, 12.85] | 9.23 [2.32, 36.78] |

| Excluding patients lost to follow‐up, studies before 20121 | 10.70 [4.41, 25.97] | 11.72 [2.90, 47.45] |

1To serve as a comparison to the methods for analysis used by Brozek 2012 (see Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews for details).

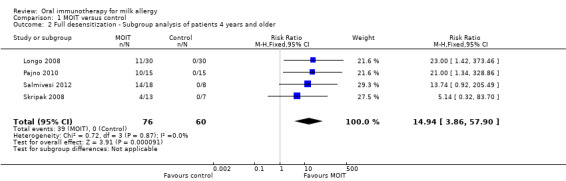

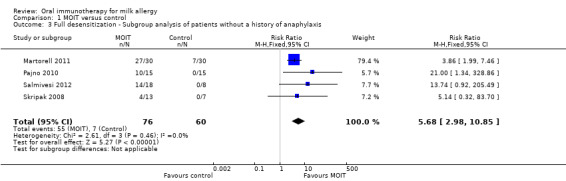

To evaluate the effect that the young patients had on the pooled analysis, a subgroup analysis including only studies with patients four years and older (Longo 2008; Pajno 2010; Salmivesi 2012, Skripak 2008) resulted in a pooled RR of 14.94 (95% CI 3.86 to 57.90, Analysis 1.2). Similarly, the pooled RR of a subgroup analysis that excluded the Longo 2008 study on patients with a history of anaphylaxis was 5.68 (95% CI 2.98 to 10.85, Analysis 1.3). Because Longo 2008 also was the only study that administered an antihistamine throughout MOIT, this analysis served as a subgroup analysis of studies that did not use pharmacological co‐intervention. Therefore regardless of age, history of anaphylaxis, or antihistamine co‐intervention, there was still a significant effect favouring MOIT. There was not enough information reported to perform subgroup analyses on comorbidities such as asthma and multiple food allergies.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 MOIT versus control, Outcome 2 Full desensitization ‐ Subgroup analysis of patients 4 years and older.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 MOIT versus control, Outcome 3 Full desensitization ‐ Subgroup analysis of patients without a history of anaphylaxis.

Tolerance

We defined tolerance as the ability to ingest a serving of milk after a period off MOIT or daily ingestion of milk for at least four weeks. None of the studies challenged the patients following a period off immunotherapy and, therefore, this outcome was not assessed.

Partial Desensitization

In all studies but one (Salmivesi 2012), a DBPCFC was performed on all patients in the control group at the end of the study. None could ingest 10 mL or greater, the threshold defined for partial desensitization, without symptoms. Twenty‐seven (25%) patients in the MOIT group could ingest a partial serving of milk (10 to 184 mL), resulting in a pooled RR of 9.34 (95% CI 2.72 to 32.09, Analysis 1.4). In the Pajno 2010 study, two of the patients in the placebo group did tolerate 30 mL of milk at the end of the study, but this quantity was also tolerated at study entry, hence we did not include them as partially desensitised.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 MOIT versus control, Outcome 4 Partial desensitization.

Again, a sensitivity analysis showed that the Salmivesi 2012 study did not significantly affect the pooled risk ratio (Table 2).

Adverse effects

While all studies provided somewhat detailed reports of adverse effects (AEs), there was much heterogeneity in the method of reporting. Therefore, it was not possible to quantitatively pool data. Furthermore, attempts to retrieve data for individual patients and events from authors was incompletely successful.

In the Pajno 2010 study, of the 15 patients in the MOIT group, three (20%) had no AEs, three (20%) had severe reactions requiring discontinuation of MOIT, and the rest had mild to moderate AEs. Two of the three with severe reactions required epinephrine, in both instances administered in the hospital during the build‐up phase. None of the patients receiving placebo had AEs.

In the Skripak 2008 study, the median frequency of AEs in each patient was 35% of the total doses in the MOIT group and 1% in the placebo group. Ninety percent of the AEs were transient and did not require treatment. Lower respiratory symptoms and multisystem symptoms occurred after 8.1% and 1.2% of the MOIT doses and 2.3% and 0% of the placebo doses, respectively. Only one patient in the MOIT group had no AEs at all. One patient receiving MOIT withdrew because of an eczema flare. In total, four patients received one dose of epinephrine each, two in the hospital, two in the home, three during build‐up and one during maintenance.

The Martorell 2011 study reported that 24 of the 30 patients in the MOIT group had AEs, but in 17 of these patients an AE only occurred in one to four doses. In 10 of these patients the AEs were mild and in 14 moderate. Half (15) of the MOIT patients had respiratory symptoms at one point (most often cough) and 11 (37%) had multisystem symptoms. Epinephrine administration was required in two patients, once each, but details around these episodes were not available.

Longo 2008 reported that all patients had at least one AE, most often local and mild. Of the 30 MOIT patients, mild laryngospasm and mild bronchospasm occurred in 14 and 12 in hospital, and three and eight at home, respectively. These episodes were most often managed with inhaled epinephrine. Four patients required parenteral epinephrine, one patient requiring it on two occasions. Of these five doses of epinephrine, four were given in hospital, and one at home. As mentioned above, this study included only patients who had a history of anaphylaxis.

Finally, the Salmivesi 2012 study reported that all 16 MOIT patients that completed the study had symptoms at one point (frequency not assessed), mostly intestinal and oral. Two patients withdrew because of "abdominal complaints." Wheezing was reported in five cases, but no emergency room visits were required. There were no cases of anaphylaxis and intramuscular epinephrine was not given. Of note, five of the eight placebo patients also reported milk symptoms. One patient in the placebo group withdrew because of accidental exposure to milk causing anaphylaxis.

Based on the data available, we cannot comment on whether over‐ or under‐reporting of AEs is a concern, although this is always a possibility.

In total, 12 (9%) of the 106 patients receiving MOIT required epinephrine, including one patient who received it on two occasions. Eight episodes occurred in hospital, three at home, and in two the details were unavailable. Of note, one episode occurred during the maintenance phase.

Skin prick testing

None of the studies reported on the change of skin prick test size before and after MOIT. Two studies assessed end‐point skin prick test titration (Martorell 2011; Skripak 2008) but we did not include this outcome in our protocol because it is not used in clinical practice and is not uniformly used in the research setting.

Serologic testing

Specific IgE at baseline and after intervention was investigated in each study, except one (Salmivesi 2012), using the same laboratory method (Phadia CAP‐System FEIA, Phadia Diagnostics). The Salmivesi 2012 trial only measured this at baseline. Because of the differences in the upper limit of measurement (one study restricted the measurement of levels up to 100 kU/L [Longo 2008], one study did not have this limit [Skripak 2008], and two were unclear) and differences in the details reported (mean, median, or individual values), we were unable to combine the data. Where there were only means reported of the baseline and post‐intervention IgE, we have presented the percent change of these means. Skripak 2008 reported a median change of 8% (range ‐50 to 64%) in the MOIT group and ‐5% (range ‐13 to 71%) in the placebo group, which was not statistically significantly different. Pajno 2010 also reported no change in the specific IgE in either groups, with a ‐13% and ‐7% change in the means of the MOIT and placebo groups, respectively (unpublished data). The majority of the patients in the Longo 2008 study had a high baseline level of milk specific IgE of over 100kU/L (23 in the MOIT group, 24 in the control group, unpublished data). Therefore, it was difficult to detect a change in these patients. However, there were eight MOIT patients who had a decrease of at least 50 kU/L compared to only one in the control group. Finally, Martorell 2011 found a significant decrease in specific IgE of 60% in MOIT compared to 9% in the control group.

Only two studies reported the change in specific IgG4 between baseline and end of treatment. In the Skripak 2008 study, there was a median change of 767% (range 29 to 1321%) in the MOIT group and 14% (range ‐14 to 157%) in the placebo group, which was a striking difference. Pajno 2010 also observed similar significant difference, with a change of 427% compared to 40% in the means of the MOIT and placebo groups, respectively.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Clearly, milk oral immunotherapy (MOIT) is an effective method to induce desensitization in patients with immunoglobulin E‐mediated cow milk allergy (IMCMA). In addition, it is also effective in partially desensitising an additional percentage of patients, increasing the safety margin in the event of an accidental exposure. The long‐term effect on tolerance is unclear at this point. Therefore, it is important to emphasize that maintaining successful desensitization requires regular consumption of the highest tolerated dose of milk. There have been concerns that unpreventable interruptions, such as illness, might jeopardize the benefit achieved. Nonetheless, MOIT provides an alternative to the current mainstay of therapy of an avoidance diet, and may potentially decrease patient and caregiver anxiety, eliminate adverse reactions, and have positive nutritional consequences.

Adverse effects were frequent with MOIT. Most patients experienced adverse effects at least once, and many experienced them with a number of doses. The majority of the symptoms were mild and self‐limited, including oral pruritis and abdominal pain. However, respiratory symptoms, ranging from cough to laryngospasm, occurred in up to half of the MOIT patients, although most were manageable with inhaled treatment. Interestingly, in the Longo 2008 study, inhaled epinephrine was often used to treat milk laryngospasm or bronchospasm. In most other countries, this therapy is not the recommended treatment for such respiratory symptoms. Therefore, this study may have underestimated the number of patients requiring intramuscular epinephrine based on treatment standards elsewhere. Despite this, overall in our included studies, for every 11 patients treated with MOIT, one required parenteral epinephrine. Hence, physician and patient acceptance of these risks should be assessed prior to intervention.

These risks should be compared to the "real life" risks of standard care, i.e. avoidance. Although it is difficult to accurately estimate the true rate of accidental allergic reactions, a questionnaire about accidental exposures in the last year used in 88 children found that 40% had at least one allergic reaction and 12% had two or more (Boyano‐Martinez 2009). Eight percent of reactions were regarded as severe and treated with epinephrine. This is, in fact, similar to the estimated rate of epinephrine administration with the above MOIT protocols (approximately 3% versus approximately 9% in MOIT arms). Furthermore, although small, the risk of death from anaphylaxis to milk remains a reality, as reported in the US and UK (Bock 2007; Pumphrey 2007).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

All of the studies addressed the primary outcome of desensitization. Although only five studies were assessed, these included several specific patient groups and interventions allowing us to determine the effect of various factors on the success of desensitization. While selection bias in recruitment is always a possibility, the diversity of study population characteristics suggests that these studies may actually be generalizable. For example, MOIT appears to be effective both in young children and later childhood, although none of the studies included adults. As expected, because Martorell 2011 treated only two‐year olds, there were more control patients who "out‐grew" their IMCMA. In fact, of all the control patients, all seven who could pass the milk double‐blind, placebo‐controlled food challenge (DBPCFC) at the end of study were from this trial. Therefore, although MOIT is effective in this age group, the treatment effect appears to be smaller. Another factor that may affect the development of desensitization is the presence of anaphylaxis. MOIT appeared to be effective regardless of the history of anaphylaxis. Although the numbers were small, the study that exclusively included patients with a history of severe allergic reactions (Longo 2008) did not appear over‐represented in the number of episodes requiring epinephrine injection. However, as discussed above, the rate of epinephrine administration may have been underestimated. MOIT with and without co‐intervention with an antihistamine was included, and it did not seem to impact the treatment effect. There is an ongoing trial assessing the added benefit of omalizumab (Xolair®) combined with MOIT compared to MOIT alone (Sampson 2010).

To date, there has not been a controlled trial examining the ability of MOIT to induce true tolerance. In the real world, this outcome would likely be most applicable. Tolerance would allow a patient who had IMCMA to truly normalize their diet. Without the need to continue daily ingestion of a serving of milk, the concerns about compliance and interruption due to sickness would be addressed. Despite a follow‐up period of up to one year, none of the studies reported increased reactions to maintenance MOIT during illness or exercise, nor were there comments on inability to continue MOIT during times of illness.

The issue of adverse effects is likely one of the most important factors to be considered when applying this evidence to practice. The vastly different reporting methods for symptoms during MOIT make them difficult to quantify. As with most interventional studies, there is a risk of under‐reporting by the patient. The frequent need for parenteral epinephrine relative to other forms of immunotherapy, for example, allergen and venom immunotherapy (Lockey 1990; Radulovic 2010), is a major concern. In addition, the frequent, milder symptoms may impact the patients' quality of life and compliance, and inquiring about the study participants' acceptance of this therapy would be insightful. If applied to practice, the physician would have to cautiously consider, and discuss with the patient at length, whether these are acceptable risks.

Although reported in other desensitization protocols (Narisety 2012; Sánchez‐García 2012), none of the studies specifically reported symptoms of eosinophilic oesophagitis secondary to MOIT.

The different MOIT protocols ranged from requiring 10 days of hospital admission to frequent, lengthy visits to the clinic or research centre. There was also close follow‐up and individualized guidance given by phone. Whether these time and personnel commitments are feasible in practice will depend on each institution.

Quality of the evidence

According to the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), the overall judgement of the quality of a body of evidence contributing to the results of the review is low. The reasons for double‐downgrading from high are 1.) high likelihood of bias and 2.) imprecision of results (small number of studies with a small number of participants). High likelihood of bias is suspected because of methodological limitations of the studies resulting in possible selection, performance, and detection bias. The confidence intervals were wide because of small sample size and variability in the estimated treatment effect. These judgments are summarized in the Table 1. We did not find sufficient studies to create a funnel plot as a means to assess publication bias. Given the small number of included studies, the majority of which detected statistically significant results, we cannot rule out the presence of reporting bias.

One strength of the evidence was that, despite clinical heterogeneity in patient characteristics and MOIT protocols, there was a consistently positive treatment effect. Furthermore, a low I2 value suggests that statistical heterogeneity is not substantial.

Potential biases in the review process

A major strength of this review is a thorough search strategy, including searching several databases as well as conference papers and ongoing trial registries to minimize missing studies. The fact that several iterations of the same studies were retrieved supports this. Furthermore, another systematic review published on the same topic (Brozek 2012) found the same randomized controlled trials, with the exception of the most recent study, as discussed in the next section.

One possible source of bias relates to the exclusion of potentially relevant studies when requests to the authors for additional information went unanswered. For example, one study (Staden 2007) fulfilled eligibility criteria, but results for both egg and milk immunotherapy were combined in the published article. A request for the data specific to milk was sent to the authors, but no response was received. It is possible that the inclusion of such data would have altered the results of the meta‐analysis.

The ongoing eligible study emphasizes the need for frequent updates of this review, as oral immunotherapy for milk allergy (MOIT) continues to be a topic of active research. Ongoing and future studies could potentially affect the conclusions that we have made.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

There have been two systematic reviews done in the past on MOIT. Fisher 2011 identified three randomized controlled trials up until 2009, two of which are included in the present review (Longo 2008, Skripak 2008) and one of which was identified in our search, but excluded because it combined results of egg and milk allergic patients (Staden 2007). The pooled data favoured MOIT, but the difference between groups was not significant. There was variability in treatment effect between the included studies and significant statistical heterogeneity. The other systematic review by Brozek 2012 included only MOIT, as we have. It identified four out of the five studies in this review, with the exception of the recently published study (Salmivesi 2012), which validates our search strategy. There are, however, differences in the treatment effects of their meta‐analyses compared to ours. Their treatment effects are larger for full desensitization (RR 9.98 [95% CI 4.11 to 24.24] versus 6.05 [95% CI 3.20 to 11.44]) and smaller for partial desensitization (RR 5.31 [95% CI 1.16 to 24.45] versus 11.55 [(95% CI 2.85 to 46.87]). These differences are likely because they have excluded patients lost to follow‐up and a patient who withdrew due to a severe eczema flare in their analysis, whereas we have included them. Also, the volumes used to define full and partial tolerance differed (they used > 150 mL and 5 to149 mL, respectively, whereas we used 200 mL and 10 to 199 mL, respectively). We performed a sensitivity analysis to assess the affect of excluding patients lost to follow‐up on final results and found that there was no significant difference (Table 2).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Studies to date have involved small numbers of patients and quality of evidence is generally low. Despite this, the current evidence shows that MOIT can clearly desensitise a majority of milk allergic children, although this has not been studied in adults. There is currently no evidence that MOIT can induce tolerance. A major drawback of MOIT is the frequency of adverse effects, although most are mild and self‐limited. The use of parenteral epinephrine is not infrequent, and physicians, along with their patients, need to assess if these risks are worthwhile. Because there are no standardized protocols, guidelines would be required prior to incorporating desensitization into clinical practice.

Implications for research.

The quality of evidence is limited by small sample size and lack of methodological rigor. A larger randomized controlled trial that attempts to eliminate selection, performance and detection bias would provide a more precise estimate of the treatment effect (in other words, a narrower confidence interval). Comparison of different protocols in order to create a standardized protocol would help facilitate transition into practice. In this review, adverse effects were difficult to quantify because of the variability in reporting. Future studies should attempt to report them in a standardized fashion and the development of a consensus severity scale of adverse effects will likely facilitate this. Co‐interventions to try to decrease the rate of adverse effects may be key, and have already begun to be explored.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Bibliographic databases searched

EMBASE

MEDLINE

MEDLINE In Process

ProQuest Dissertations and Theses

BIOSIS Previews

Cochrane Central Registry of Controlled Clinical Trials (CENTRAL)

ClinicalTrials.gov

International Clinical Trials Registry Platform

Conference Papers Index

Conference Proceedings Citation Index Science (CPCI‐S)

NLM Gateway Meeting Abstracts

LILACS

Foreign Doctoral Dissertations

Appendix 2. MEDLINE search strategy

1. Milk/

2. exp Milk Proteins/

3. Milk Hypersensitivity/

4. milk.tw.

5. dairy.tw.

6. CMA.tw.

7. or/1‐6

8. Desensitization, Immunologic/

9. Immunotherapy/

10. exp Administration, Oral/

11. "Dose‐Response Relationship, Immunologic"/

12. Allergens/ad [Administration & Dosage]

13. Immune Tolerance/

14. Mouth/im [Immunology]

15. Immunotherap*.tw.

16. OIT.tw.

17. desensiti*tw.

18. oral tolerance.tw.

19. oral induction.tw.

20. up dosing.tw.

21. sublingual.tw.

22. Dose‐Response Relationship, Drug/

23. SOTI.tw.

24. (dose adj escalat*).tw.

25. SLIT.tw.

26. or/8‐25

27. 7 and 26

28. clinical trial.pt.

29. randomized.ab.

30. placebo.ab.

31. exp Clinical Trial/

32. randomly.ab.

33. trial.ti.

34. or/28‐32

35. Animals/

36. Humans/

37. 35 not (35 and 36)

38. 34 not 37

39. 27 and 38

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. MOIT versus control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Full desensitization | 5 | 196 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 6.61 [3.51, 12.44] |

| 2 Full desensitization ‐ Subgroup analysis of patients 4 years and older | 4 | 136 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 14.94 [3.86, 57.90] |

| 3 Full desensitization ‐ Subgroup analysis of patients without a history of anaphylaxis | 4 | 136 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.68 [2.98, 10.85] |

| 4 Partial desensitization | 5 | 196 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 9.34 [2.72, 32.09] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Longo 2008.

| Methods | RCT, not blinded Control: milk‐free diet |

|

| Participants | 60 patients with IgE‐mediated cow's milk allergy and a history of a severe reaction, aged 5‐17 years | |

| Interventions | Admitted for 10 days: hourly up‐dosing on day 1, then 2‐hourly up‐dosing on days 2‐10 with 3‐6 doses per day, up to 20 mL Updosing every other day, as tolerated, at home up to 150 mL plus other forms of cow's milk in diet Maintenance of 150 mL plus other forms of cow's milk until end of study and beyond |

|

| Outcomes | Ability to tolerate full serving (desensitization) (assessed at 1 year from start of study) Abilit to tolerate partial serving (partial desensitization) (assessed at 1 year from start of study) Severe adverse effects All adverse effects Change in specific IgE (assessed at 1 year from start of study) |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Simple computerized randomisation was performed |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Allocation was by sequentially numbered, opaque sealed envelopes |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | There was no blinding |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | There was no blinding |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No missing outcome data |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Pre‐specified outcomes were reported |

Martorell 2011.

| Methods | RCT, not blinded Control: milk‐free diet |

|

| Participants | 60 patients with IgE‐mediated cow's milk allergy, without a history of anaphylactic shock, aged 24‐36 months | |

| Interventions | In institution, hourly up‐dosing over 2 days up to 2.5 mL Weekly up‐dosing in institution with daily doses at home up to 200 mL Maintenance of 200 mL daily continued until end of study and beyond Outcomes assessed at 1 year from start of study |

|

| Outcomes | Ability to tolerate full serving (desensitization) (assessed at 1 year from start of study) Abilit to tolerate partial serving (partial desensitization) (assessed at 1 year from start of study) Severe adverse effects All adverse effects Change in specific IgE (assessed at 1 year from start of study) |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Sequence generation process was not fully described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Allocation concealment was not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | There was no blinding |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | There was no blinding |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No missing outcome data |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Pre‐specified outcomes were not clear |

Pajno 2010.

| Methods | RCT, double‐blinded Control: soy milk placebo |

|

| Participants | 30 patients with IgE‐mediated cow's milk allergy aged 4‐13 years | |

| Interventions | Weekly up‐dosing in institution with daily doses at home Up to 200 mL in 18 weeks No maintenance phase |

|

| Outcomes | Ability to tolerate full serving (desensitization) (assessed at week 18) Abilit to tolerate partial serving (partial desensitization) (assessed at week 18) Severe adverse effects All adverse effects Change in specific IgE (assessed at week 18) Change in specific IgG4 (assessed at week 18) |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Sequence generation process was not fully described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Allocation concealment was not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Masking of the patients and investigators was attempted, but some of the patients recognized the taste of the soy milk placebo |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Investigators remained blinded to the treatment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No missing outcome data |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Pre‐specified outcomes were not clear |

Salmivesi 2012.

| Methods | RCT, double‐blinded Control: oat milk, rice milk, or soy milk placebo |

|

| Participants | 28 patients with IgE‐mediated cow's milk allergy aged 7‐14 years | |

| Interventions | Daily up‐dosing with observation in the clinic periodically on 9 days over 78 days Otherwise, up‐dosing at home 6400 mg reached on day 162 |

|

| Outcomes | Ability to tolerate full serving (desensitization)* (assessed within two weeks of day 162 (about 25 weeks from start of study)) Abilit to tolerate partial serving (partial desensitization)* (assessed within two weeks of day 162 (about 25 weeks from start of study)) Severe adverse effects All adverse effects |

|

| Notes | *Not assessed in placebo group 6400 mg milk equivalent to 200 mL |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Sequence generation process was not fully described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of concealment was not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Participants and investigators were blinded and it was unlikely that the blinding was broken |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Participants and investigators were only unblinded after the study outcomes were assessed |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Ability to ingest milk was not assessed in the placebo group following treatment |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Study protocol was available and all pre‐specified outcomes were reported |

Skripak 2008.

| Methods | RCT, double‐blinded Contro: placebo powder |

|

| Participants | 20 patients with IgE‐mediated cow's milk allergy, without a history of anaphylaxis requiring hospitalisation, aged 6‐21 years | |

| Interventions | Oral immunotherapy using dry powdered milk in a vehicle In institution, up‐dosing every 30 minutes to minimum 12 mg Weeky up‐dosing in institution up to 500 mg with daily dosing at home (about 7 weeks) Maintenance of 500 mg daily for 13 weeks |

|

| Outcomes | Ability to tolerate full serving (desensitization) (assessed after 13 weeks of maintenance (21 weeks from the start of study)) Abilit to tolerate partial serving (partial desensitization) (assessed after 13 weeks of maintenance (21 weeks from the start of study)) Severe adverse effects All adverse effects Change in specific IgE (assessed after 13 weeks of maintenance (21 weeks from the start of study)) Change in specific IgG4 (assessed after 13 weeks of maintenance (21 weeks from the start of study)) |

|

| Notes | MOIT was only up to 500 mg (equivalent to 15 mL milk) but post‐immunotherapy DBPCFC was up to 8140 mg (equivalent to 243 mL) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Sequence generation process was not fully described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of concealment was not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Participants and investigators were blinded and it was unlikely that the blinding was broken |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Participants and investigators were only unblinded after the study outcomes were assessed |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No missing outcome data |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Study protocol was available and all pre‐specified outcomes were reported |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| 28th Congress | Indexed in the Conferences Papers index, which was searched; therefore, contained records were individually assessed |

| Alonso 2008 | Abstract only; not enough information to assess; authors contacted but no response received |

| Alvaro 2012 | Not RCT |

| Anonymous 2009 | Not original research |

| Aruanno 2009 | Not RCT |

| Bahna 1996 | Not original research |

| Barbi 2012 | Not RCT |

| Bauer 1999 | Not RCT |

| Bedoret 2012 | Not RCT |

| Belli 2003 | Not RCT |

| Berin 2011 | Not original research |

| Berti 2008 | Not original research |

| Bonito‐Vitor 2009 | Not RCT |

| Borel 1992 | Not human research |

| Burks 2008 | Not original research |

| Calvani 2010 | Not RCT |

| Calvani 2012 | Not RCT |

| Canani 2012 | Not RCT |

| Chafen 2010 | Not RCT |

| Chhabra 2009 | Not original research |

| Couto 2011 | Not RCT |

| Couto 2012 | Not RCT |

| Crisafulli 2012 | Not original research |

| de Boissieu 2006 | Not RCT |

| Dona Diaz 2007 | Not RCT |

| Du Toit 2011 | Not original research |

| Dupont 2010 | Intervention not oral immunotherapy |

| Farmakas 2009 | Not RCT |

| Fiocchi 2010 | Not original research |

| Firszt 2011 | Not original research |

| Fisher 2011 | Not RCT |

| Frischmeyer‐Guerrerio 2011 | Not RCT |

| Frutos 2012 | Not RCT |

| Gallucci 2011 | Not RCT |

| García‐Ara 2012 | Not RCT |

| Hague 2012 | Not RCT |

| Haynes 2010 | Not RCT |

| Hourihane 2002 | Not original research |

| Hulshof 2011 | Not original research |

| Isolauri 1995 | Not original research |

| Kaneko 2009 | Not RCT |

| Kaneko 2010 | Not RCT |

| Katz 2011 | Not RCT |

| Keet 2008 | Not original research |

| Keet 2010 | Comparison not placebo, instead sublingual immunotherapy |

| Keet 2012 | Comparison not placebo |

| Kleine‐Tebbe 2005 | Not original research |

| Kloepfer 2008 | Not original research |

| Lachaux 2006 | Not RCT |

| LeBovidge 2012 | Not RCT |

| Levy 2011 | Not RCT |

| Levy 2012 | Not RCT |

| Longo 2012 | Not RCT |

| Luyt 2009 | Not RCT |

| Mansouri 2007 | Not RCT |

| Marino 2009 | Not original research |

| Mazer 2009 | Not original research |

| Meglio 2004 | Not RCT |

| Meglio 2011 | Not RCT |

| Mondoulet 2011 | Not original research |

| Mori 2008 | Not RCT |

| Morisset 2007 | Not IgE‐mediated cow milk allergy |

| Mousallem 2012 | Not original research |

| Nadeau 2011 | Not RCT |

| Nadeau 2012 | Not original research |

| Nadeau 2012a | Not original research |

| Narisety 2009 | Not RCT |

| Nieto 2010 | Not RCT |

| Niggemann 2006a | Not original research |

| Noh 2009 | Not RCT |

| Nowak‐Wegrzyn 2007 | Not RCT |

| Nowak‐Wegrzyn 2008 | Not RCT |

| Nowak‐Wegrzyn 2010 | Not original research |

| Nowak‐Wegrzyn 2011 | Not original research |

| Nowak‐Wgrzyn 2011 | Not original research |

| Nucera 2000 | Not RCT |

| Nucera 2008 | Not RCT |

| Ojeda Fernandez 2007 | Not RCT |

| Oppenheimer 2010 | Not original research |

| Paiva 2009 | Not RCT |

| Pajno 2011 | Not original research |

| Pajno 2011a | Not RCT |

| Passalacqua 2012 | Not original research |

| Patriarca 2003 | Not RCT |

| Patriarca 2007 | Not RCT |

| Pecora 2009 | Not RCT |

| Poisson 1988 | Not RCT |

| Rancitelli 2011 | Not original research |

| Rapp 1978 | Not RCT |

| Reche 2009 | Not RCT |

| Reche 2011 | Not RCT |

| Rodriguez‐Alvarez 2007 | Not RCT |

| Rolinck‐Werninghaus 2005a | Not RCT |

| Rosenwasser 2011 | Not original research |

| Saltzman 2012 | Not RCT |

| Sampson 1997 | Not original research |

| Sampson 2003 | Not original research |

| Sampson 2010 | Compares MOIT plus omalizumab versus MOIT without omalizumab; control not placebo or avoidance |

| Sanchez‐Garcia 2011 | Not RCT |

| Saretta 2012 | Not RCT |

| Schiavino 2001 | Not RCT |

| Schmidt 2007 | Not RCT |

| Scurlock 2009 | Not original research |

| Seopaul 2012 | Comparison not placebo |

| Sicherer 2003 | Not original research |

| Sicherer 2009 | Not original research |

| Simons 2010 | Not RCT |

| Skripak 2009 | Not original research |

| Staden 2007 | Meets inclusion criteria, but results combined egg and milk allergic patients. Contacted author for separate data on cow's milk allergic patients with no response. |

| Staden 2008 | Not RCT |

| Stein 2011 | Not RCT |

| Steinman 2008 | Not RCT |

| Strobel 2006 | Not original research |

| Tunis 2010 | Not RCT |

| Vickery 2010 | Not original research |

| Wasserman 2010 | Not RCT |

| Wuethrich 1996 | Not RCT |

| Yanagida 2010 | Not RCT |

| Zapatero 2008 | Not RCT |

| Zein 2011 | Not RCT |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

Katsunuma 2012.

| Trial name or title | Effect of oral immunotherapy in preschool children with milk allergy; trial for the detection of prospective markers for the effectiveness |

| Methods | RCT, observation controlled |

| Participants | 3 to 6 year old patients with IMCMA confirmed by a positive DBPCFC and elevated specific IgE, excluding those with a history of anaphylaxis |

| Interventions | MOIT versus observation |

| Outcomes | 1. Ability to tolerate 100mL of milk on provocation testing after 1 year of intervention 2. Ability to tolerate any portion of milk on provocation testing after 1 year of intervention 3. Change in skin prick test result 4. Change in milk specific IgE, IgG, IgG4 levels |

| Starting date | July 2011 |

| Contact information | Toshio Katsunuma 4‐11‐1, Izumi‐Honcho, Komae City, Tokyo Japan tkatsunuma@jikei.ac.jp |

| Notes | Study in recruitment stage |

Differences between protocol and review

The protocol stated that studies that included a pharmacological co‐treatment would be considered separately. Instead we elected to include the one study that had this and perform a subgroup analysis excluding this study instead. We added in a subgroup analysis of patients four years and older in the presence of a study in very young children.

Contributions of authors

Joanne Yeung: drafted the protocol, trial screening and selection, data extraction, risk of bias assessment, data entry into RevMan, data analysis, analysis interpretation, drafted the final review

Lorie Kloda: search strategy development, performed search for trials, obtained copies of trials, drafted the methods section of the final review

Jason McDevitt: trial selection, data extraction, risk of bias assessment, edited final review

Moshe Ben‐Shoshan: data analysis, analysis interpretation, edited final review

Reza Alizadehfar: edited the protocol, analysis interpretation, edited final review

Declarations of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

New

References

References to studies included in this review

Longo 2008 {published and unpublished data}

- Longo G, Barbi E, Berti I, Meneghetti R, Pittalis A, Ronfani L, et al. Specific oral tolerance induction in children with very severe cow's milk‐induced reactions. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2008;121:343‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Martorell 2011 {published and unpublished data}

- Martorell A. Specific oral tolerance induction to cow's milk allergy. http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01199484. [Google Scholar]

- Martorell A, Hoz B, Ibaez M, Bone J, Michavila A, Plaza A, et al. Specific oral tolerance induction (SOTI) as an useful treatment to cow milk proteins (CMPs) allergy. Allergy: European Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2010;65:371. [Google Scholar]

- Martorell A, Hoz B, Ibanez M D, Bone J, Terrados MS, et al. Oral desensitization as a useful treatment in 2‐year‐old children with cow's milk allergy. Clinical and Experimental Allergy 2011;41:1297‐1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pajno 2010 {published and unpublished data}

- Caminiti L, Passalacqua G, Barberi S, Vita D, Barberio G, Luca R, et al. A new protocol for specific oral tolerance induction in children with IgE‐mediated cow's milk allergy. Allergy and Asthma Proceedings 2009;30:443‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caminiti L, Passalacqua G, Barberi S, Vita D, Barberio G, Pajno G. A new protocol for specific oral tolerance induction in children with IgE‐mediated cow's milk allergy. Abstract from 28th Congress of the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Warsaw, Poland. Allergy 2009;64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajno CB, Caminiti L, Barberi S, Vita D, Bacna‐Cagnani CE, Barberio G, et al. Specific oral tolerance induction with a weekly updosing schedule in children with Ige mediated cow's milk allergy. Journal of Allergy & Clinical Immunology 2009;123:S32. [Google Scholar]

- Pajno G, Caminiti L, Ruggeri P, Luca R, Vita D, Rosa M, et al. Oral immunotherapy for cow's milk allergy with a weekly updosing regimen: A randomised double blind controlled study. Allergy 2010;65(Suppl. 92):370. [Google Scholar]

- Pajno G, Caminiti L, Vita D. A double‐blind placebo‐controlled study of oral milk immunotherapy with the weekly incremental dose. Abstract from 28th Congress of the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Warsaw, Poland. Allergy 2009; Vol. 64.

- Pajno GB, Caminiti L, Ruggeri P, Luca R, Vita D, Rosa M, et al. Oral immunotherapy for cow's milk allergy with a weekly up‐dosing regimen: a randomized single‐blind controlled study. Annals of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology 2010;105:376‐81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Salmivesi 2012 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Paassilta M. Safety of Oral Immunotherapy for Cow's Milk Allergy in School‐aged Children. http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01361347. [Google Scholar]

- Paassilta M, Salmivesi S, Korppi M, Makela M. Milk oral immunotherapy in school‐aged children with immunoglobulin E‐mediated cow's milk allergy. Allergy: European Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2010;65:370. [Google Scholar]

- Salmivesi S, Korppi M, Mäkelä MJ, Paassilta M. Milk oral immunotherapy is effective in school‐aged children. Acta Paediatrica 2012;epub ahead of print. [DOI: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2012.02815.x] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Skripak 2008 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Skripak JM, Nash SD, Brereton NH, Rowley H, Oh S, Hamilton RG, et al. A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled (DBPC) study of milk oral immunotherapy (MOIT) for cow's milk allergy (CMA). Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2008;121:S137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skripak JM, Nash SD, Rowley H, Brereton NH, Oh S, Hamilton RG, et al. A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study of milk oral immunotherapy for cow's milk allergy. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2008;122:1154‐60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood RA. A Randomized, Double‐Blind, Placebo‐Controlled Study of Oral Milk Immunotherapy for Cow's Milk Allergy. http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00465569. [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

28th Congress {published data only}

- 28th Congress of the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology Abstract Book. Allergy: European Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. Conference: 28th Congress of the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology Abstract Book Warszawa Poland. Conference Start 2009;20090606. [Google Scholar]

Alonso 2008 {published data only}

- Alonso E, Zapatero L, Fuentes V, Barranco R, Davila G, Martinez M. Specific Oral Tolerance Induction in 39 Children with IgE Mediated Persistent Cows Milk Allergy. 2008 Annual meeting of the Americal Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology 2008. [Google Scholar]

Alvaro 2012 {published data only}

- Alvaro M, Giner MT, Vazquez M, Lozano J, Dominguez O, Piquer M, et al. Specific oral desensitization in children with IgE‐mediated cow's milk allergy. Evolution in one year. European Journal of Pediatrics 2012;171:1389‐95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Anonymous 2009 {published data only}

- Anonymous. ...And a promising treatment for cow's milk allergy. Child Health Alert 2009;27:1‐2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Aruanno 2009 {published data only}

- Aruanno A, Nucera E, Pecora V, Buonomo A, Pasquale T, Lombardo C, et al. Oral specific desensitisation in food allergy and loss of tolerance after interruption of the maintenance phase: five case reports. Abstract from 28th Congress of the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Warsaw, Poland. Allergy 2009; Vol. 64.

Bahna 1996 {published data only}

- Bahna SL. Oral desensitization with cow's milk in IgE‐mediated cow's milk allergy: Contra. In: Wuethrich B, Ortolani C editor(s). Highlights in Food Allergy: 6th International Symposium on Immunological and Clinical Problems of Food Allergy, Lugano, September, 1995. Basel, Switzerland: S. Karger AG, 1996:233‐5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Barbi 2012 {published data only}

- Barbi E, Longo G, Berti I, Matarazzo L, Rubert L, Saccari A, et al. Adverse effects during specific oral tolerance induction: in home phase. Allergologia et Immunopathologia 2012;40:41‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bauer 1999 {published data only}