Abstract

In this study, CuS@PDA nanoparticles were synthesized and used to create a novel tumor-targeting nanocomposite platform composed of copper sulfide@polydopamine–folic acid/doxorubicin (CuS@ PDA–FA/DOX) for performing both photothermal and chemotherapeutic cancer treatment. The nanocomposite platform has ultrahigh loading levels (4.2 ± 0.2 mg mg−1) and a greater photothermal conversion efficiency (η = 42.7%) than CuS/PDA alone. The uptake of CuS@PDA–FA/DOX nanocomposites is much higher in MCF-7 cells than in A549 cells because MCF-7 cells have much higher folic acid receptors than A549. Under near infrared (NIR) irradiation, the CuS@PDA–FA/DOX system using a synergistic combination of photothermal therapy and chemotherapy yields a better therapeutic effect than either photothermal therapy or chemotherapy alone. The treatment is very effective with the cell viability is only 5.6 ± 1.4%.

Introduction

Nowadays, our increasing knowledge of cancer has gradually directed us toward developing ever more nuanced treatments particular to the type of cancers which we wish to treat. Modern techniques commonly used are effective treatment methods,1-4 but they alone might not always be sufficient for achieving remission. Therefore, there is still a pressing need for more precise strategies with high therapeutic efficacies and low toxicities that can be used independently of, or in conjunction with, conventional treatments. Among them, the combination of chemotherapy and thermotherapy shows promising therapeutic effects.

Doxorubicin (DOX) is a commonly used drug in chemotherapy. DOX can induce apoptosis in tumor cells by damaging their DNA.5 However, the use of DOX is usually restricted by its high toxicity to normal cells.6,7 With the development of nanomaterials, the connection of functional nanomaterials have provided new ways to solve some problems of DOX restrictions.8-12 Nanomaterials commonly used for targeted drug delivery include inorganic nanomaterials (gold,13 silicon nanoparticles,14 transition metal sulfides15), carbon-based materials (mesoporous carbon,16 graphene17), lipid materials (liposomes,18 lipid nanoparticles19) and polymeric nanoparticles (micelles,20 dendrimers,21 hydrogels22), etc. For example, Wang et al. synthesized Se@SiO2–FA–CuS nanocomposites, which targeted the delivery of DOX by folic acid (FA). When the concentration of Se@SiO2–FA–CuS/DOX is 200 μg mL−1, almost all the HeLa cells were killed under laser irradiation. The treatment also exhibited remarkable suppression to mice and had no appreciable damage within the organs of mice.23 Chen et al. reported the fabrication of HA-MSNs-AuNBs loading DOX, which could specifically target toward CD-44 overexpressing cells due to the targeting property of HA.22 Cao et al. designed a peptide (Nap-FFGPLGLARKRK) for cancer-targeted DOX delivery.24 These fibrils can target to the cancer cells overexpressed MMP7. The cell viability for the three cancer cell lines (HeLa, HepG2, and A549 cells) decreased to less than 30%, when the concentration of the nanocomposite is 2.0 μM. In the case of treatment with the nanocomposite in vivo, the tumor growth was also successfully suppressed and the body weight of mice showed no significant variation. Thus, loading DOX to a suitable nanomaterial to build a targeting drug delivery vehicle is advantageous not only due to reducing the toxicity of DOX, but also because of the controlled release at the tumor site.

The loading level is defined as the mass ratio of the drug loaded on the materials to the nanomaterials. The DOX loading level of nanomaterials is generally low, which is another concern. For example, Chen et al. synthesized flower-like MoS2@BSA nanoparticles to load DOX due to electrostatic interactions and a 2D flower-like structure with a maximum loading level of only 0.34 (mg mg−1),25 and the loading levels for other nanomaterials can be found in the Table S1 (ESI†). If the loading level is low, the amount of DOX into the cells would be less, which would reduce the chemotherapeutic effect. So, it is necessary to synthesize a carrier with a high loading capacity or a drug with a good biocompatibility which can compensate for the lack of drug loading by using more materials in vivo.

Copper sulfide (CuS) has been shown to be one of the most promising photothermal materials for cancer treatment.26-28 CuS is advantageous not only due to its low cost and high photo-stability, but also because of its broad absorption in the near-infrared region. CuS nanoparticles have also previously been used to fabricate multifunctional drug-delivery platforms.29-32 However, CuS alone is not very sufficient for biomedical use in this context and requires the ligation with some materials to make it more effective and more biocompatible. Polydopamine (PDA), which has a chemical structure similar to that of melanin, can also convert light into heat due to its wide absorption in the near infrared region.33 The advantages of ultra-low toxicity and good biocompatibility34 make PDA an ideal choice to coat CuS for biomedical applications. In this work, we tried to combine CuS with PDA by synthesizing novel CuS@PDA–FA nanoparticles and used them to load DOX on cancer treatment. The combination of PDA with CuS nanoparticles may enhance the biocompatibility of CuS and improve its photothermal capability. We used the CuS@PDA–FA nanocomposites as a dual-stimuli responsive targeting nanoplatform to deliver DOX to combine PTT and chemotherapy for breast cancer treatment.

Experimental section

Materials

Trisodium citrate dehydrate (Na3C6H5O7·2H2O), copper(ii) chloride dehydrate (CuCl2·2H2O), N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC), N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd (Shenyang, China). Dopamine hydrochloride (C8H11NO2·HCl, DA), sodium sulfide nonahydrate (Na2S·9H2O), polyethyleneimine (PEI, Mw 1800) and folic acid (FA) were purchased from Aladdin (Shanghai, China). All reagents were applied as received with no further purification.

Characterization. The morphology and size of the as-prepared nanoparticles were observed on a JEM-2100 HR transmission electron microscope (TEM, JEOL Ltd, Japan), dimension icon atomic force microscope (AFM, Bruker Ltd, German) and a SU8010 field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM, Hitachi Ltd, Japan). The surface charge properties of related nanoparticles were gained using a Zetasizer Nano ZS90 instrument (Malvern Ltd, England). FT-IR spectra were obtained by using a VERTEX70 FT-IR spectrophotometer (Bruker Ltd, German) within a range of 800–4000 cm−1. UV-vis absorption spectra were recorded with a UH5300 spectrophotometer (Hitachi Ltd, Japan) with a 1.0 cm quartz cell. The XRD spectrum was shown by Empyrean X-ray Diffractometer (Panalytical Ltd, Netherlands). XPS Characterization was performed with Escalab 250Xi X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (Thermo Fisher Ltd, USA). The photothermal performance of the nanoparticles was measured on a thermalmeter (IKA Ltd, Germany). The fluorescence of the MCF-7 cells was observed with a FV1200 confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus Corporation, Japan).

Preparation of PEIylated CuS@PDA

The CuS@PDA nanoparticles were synthesized as found in the literature.3,23 In brief, 14 mg of CuCl2·2H2O was dissolved in 100 mL of deionized (DI) water and stirred in an ice-water bath. Then, 8 mg of Na3C6H5O7·2H2O and 20 mg of DA were added into the CuCl2 solution to form a clear solution. 24 mg of Na2S·9H2O predissolved in 1 mL DI water was added into the previous solution under sonication for 30 min. The solution gradually changed from light blue to brownish yellow. After being heated at 90 °C for 1 h, the CuS@PDA nanoparticles were collected by washing with DI water in triplicate and centrifuged at 20 000 rpm for 15 min. PDA and citrate-coated CuS nanoparticles were used as controls for comparisons.

For PEIylation, 10 mg of as-prepared CuS@PDA was dispersed in 10 mL of DI water by ultrasonication and mixed with 0.25 mL of PEI solution (20 mg mL−1) for 12 h under stirring. PEI was adsorbed onto the surface of CuS@PDA nanoparticles via electrostatic interactions. The PEIylated CuS@PDA nanoparticles were collected and purified by washing with DI water for 3 times by centrifugation.

Preparation of CuS@PDA–FA.

FA was covalently conjugated to PEI following an approach from the literature.32 125 μL of FA (20 mg mL−1) in DMSO was dispersed in 5 mL phosphate buffer (PBS, 10 mM, pH 5.5), mixed with 2.5 mg of EDC and reacted for 10 min. 2.5 mg of NHS was then added to react for 30 min. Subsequently, the pH was adjusted from 5.5 to 7.4. The above solution was mixed with 2.5 mL of CuS@PDA–PEI solution (2 mg mL−1). After stirring for 12 h, the CuS@PDA–FA nanoconjugates were obtained, and then the product was washed several times with DI water.

Photothermal performance of CuS@PDA–FA.

To test the photothermal effects of CuS@PDA–FA, 0.3 mL of CuS, PDA, CuS@PDA and CuS@PDA–FA solution (400 μg mL−1) were irradiated by an 808 nm laser for 10 min and the solution temperature was measured by a thermometer for different laser power densities (0.6, 0.8, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0 W cm−1). The same laser power (1.5 W cm−1) was used to irradiate different concentrations of CuS@PDA–FA (100, 200 and 400 μg mL−1) to compare their heating effects.

For the photothermal stability of CuS@PDA–FA nanocomposites, the solution (200 μg mL−1) was irradiated and cooled for 5 cycles while the temperature variations were recorded.

Loading DOX on CuS@PDA–FA (CuS@PDA–FA/DOX).

For loading of DOX, 100 μL of DOX solution (0.25, 0.50, 0.75, 1.00, 1.25, 2.50, 5.00, 10.00, 18.75 mg mL−1) was mixed with 25 μL of CuS@PDA–FA (5 mg mL−1) in PBS (10 mM, pH 8.5), and then PBS was added into the mixture solution to 1.0 mL. After shaking for 24 h in the dark at room temperature, the mixture was centrifuged and washed three times with DI water to remove the free DOX in the supernatant and obtain the nanocomposites (CuS@PDA–FA/DOX). To estimate the DOX loading capability, the concentration of unloaded DOX in the supernatant was determined by a UH5300 spectrophotometer to deprive the loading levels as following:

where m0 (μg) and m1 (μg) are the masses of initial and unloaded DOX, respectively, and mCuS (μg) is the mass of the CuS@PDA–FA nanocomposite. Besides, 60 μL DOX solution (5 mg mL−1) was mixed with 500 μg of CuS@PDA–FA in 10 mM PBS (pH 5.5, 6.2, 7.4 and 8.5) with different pH values to explore the effect of pH on drug loading.

In vitro pH-triggered and NIR-triggered drug release

The pH-triggered drug released experiments were carried out at different pH values. Typically, 0.5 mg of DOX-loaded material was dispersed in 1 mL PBS with different pH values (5.5, 6.2 and 7.4). The above solutions were incubated in a 37 °C water bath shock for 72 h. At certain time points (1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 48 and 72 h), the mixture was centrifuged to gain the supernatant, and the supernatant was measured to calculate the amount of released DOX. Then, the precipitate was redispersed in the corresponding volume of fresh buffer.

For the NIR-triggered DOX release, an 808 nm laser was used to irradiate the solution of CuS@PDA–FA/DOX. The CuS@PDA–FA/DOX was suspended in PBS (pH 5.5) at 37 °C bath for 12 h and irradiated by the laser (1.5 W cm−2, 5 min) at specific time points (1, 3, 5, 7, 9 and 12 h). Subsequently, the solution was centrifuged to collect the supernatant and estimate the concentration of released DOX by measuring the absorbance of 501 nm. Afterward, the precipitate was resuspended in fresh buffer for continuous release.

In vitro biocompatibility assay and targeting assay.

The biocompatibility was studied by an MTT assay. First, the MCF-7 cells, cultured in DMEM (HyClone, China) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin and 1% streptomycin, were firstly seeded in 96-well plates (1.0 × 104 cells per well) and incubated for 24 h in a humidified incubator (5% CO2, 37 °C). Then, the cells were incubated with different concentrations of CuS@PDA–FA (10, 20, 50, 100 and 200 μg mL−1). After incubation for 20 h, an MTT solution (5.0 mg mL−1) was added in each well and the cells were cultured at 37 °C for another 4 h. When the purple precipitate was clearly visible, 100 μL DMSO was added to dissolve the generated formazan crystals and was swirled gently. Thereafter, absorbance of each well was measured at 490 nm by a microplate reader (BIO-TEK, USA).

In addition, non-metabolic assay was also did by using acridine orange (AO) and propidium iodide (PI) staining. Briefly, the cells were seeded in glass-bottom cell culture dishes and grown for 24 h. Then, the cells were incubated with the fresh medium including CuS@PDA–FA (0, 20, 80, 200 μg mL−1) for 20 h and washed with 10 mM PBS buffer. After staining with the AO and PI solution for 15 min, the cells were observed by a confocal microscope. The software ImageJ was used to count viable cells in 5 fields of a sample, and calculate the cell viability of MCF-7 cells. The cell viability was defined as the ratio of the viable cell count N in the material groups to the viable cell count N0 in the control group.

To investigate the targeting effect of CuS@PDA–FA/DOX toward cancer cells, a confocal microscope was used to observe the MCF-7 cells co-cultured for 0.5 and 4 h with medium containing CuS@PDA–FA/DOX or CuS@PDA–PEI/DOX (100 μg mL−1). A549 cells were used as contrast cells.

The MTT assay was used for analyzing the cytotoxic effects of CuS@PDA–FA/DOX and CuS@PDA–PEI/DOX against MCF-7 cells to demonstrate the targeting performance after folate receptor anchoring. The procedure was the same as previously mentioned for the biocompatibility assay.

In vitro chemotherapy and photothermal therapy.

For chemo-photothermal therapy assays, MCF-7 cells were seeded in 96-well plates for 24 h. Different concentrations of CuS@PDA–FA, free DOX and CuS@PDA–FA/DOX were added into the wells. Among them, the amount of free DOX was consistent with the amount of DOX releasing from CuS@PDA–FA/DOX. The mixture was cultured at 37 °C for another 20 h. There were two parallel groups. Group 1 received a five-minute exposure to the 808 nm laser (0.8 W cm−2) during incubation time, while group 2 received no exposure. Afterwards, the MTT assay was implemented to measure the viability of cells by a microplate reader. GraphPad Prism 6 was used to perform a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) on data of synergy therapy. If the P value is less than 0.05, the difference is statistically significant.

Results and discussion

Preparation and characterization of CuS@PDA–FA

Tiny CuS@PDA nanoparticles were successfully synthesized via a convenient hydrothermal method. When Na2S was dispersed in a CuCl2 aqueous solution, the S2− would react with the Cu2+ to generate CuS. DA would grow with CuS together to gain CuS@PDA nanoparticles. Then, the nanoparticles were functionalized with PEI to introduce amino groups on their surface. The gained nanoparticles were conjugated with FA by the formation of amide bonds. The synthesis procedure and the application in tumor therapy are displayed in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration of strategy to fabricate CuS@PDA–FA/DOX nanoparticle as a multifunctional antitumor nanoplatform for targeted synergetic chemo-photothermal combined cancer therapy.

The size and morphology of CuS@PDA were observed by TEM and AFM. As observed in Fig. 1a and b, the CuS@PDA nanoparticles are ~ 15 nm. The connection of PEI and FA change the size of nanoparticles to 20 nm (Fig. S1, ESI†). Additionally, the images also indicate that the CuS@PDA and CuS@PDA–FA nanocomposite are synthesized successfully with uniform size. The tiny size makes the nanoparticles easier to penetrate the cancer cells. We also studied the DLS size distribution of CuS@PDA and CuS@PDA–FA. As shown in Fig. S1c and d (ESI†), the size of the nanocomposite we measured was larger than that of the electron microscope images. This could be caused by two reasons: (1) DLS measures the hydrodynamic diameter of the nanoparticles in the solution, (2) the possible aggregation of nanomaterials themselves can cause larger dimensional changes. Thus, in order to avoid aggregation, ultrasonication is performed before subsequent operations.

Fig. 1.

(a) TEM image of CuS@PDA. (b) AFM image of CuS@PDA. (c) XRD pattern of CuS, PDA and CuS@PDA. (d) XPS survey spectrum of CuS@PDA nanocomposites. Inset: Comparison of XPS survey spectra from 250 eV to 560 eV for CuS and CuS@PDA.

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern shows that CuS@PDA nanoparticles can be indexed into CuS (JCPDS No. 06-0464). The diffraction peaks (2θ 27.68°, 29.27°, 31.78°, 47.94°, 52.71°, 59.34°) are attributed to (101), (102), (103), (110), (108) and (116) planes, respectively (Fig. 1c). It implies the presence of CuS in the synthetic nanomaterials. The XPS spectrum of the CuS@PDA nanostructure in Fig. 1d reveals the presence of Cu, S, C, O and N. The XPS spectrum of CuS@PDA shows that there is a new peak at 400 eV attributed to N 1s compared with CuS, which proves PDA is indeed on the surface of nanomaterials. As illustrated in Fig. S2a (ESI†), the Cu 2p1/2 peak can be deconvolved into two peaks at 952.5 and 954.5 eV, and the Cu 2p3/2 peak can be fitted with three peaks at 932.6, 933.3 and 934.7 eV. The peaks of 952.5 eV and 932.6 eV are typical values for Cu2+ in CuS. The peaks at 954.5 and 933.3 eV can be CuS─CuSO4. The binding energy of 934.7 eV would be Cu─O, which proves Cu2+ could coordinate with PDA. The S 2p3/2 (162.3 eV) and S 2p1/2 (164.6 eV) are CuS, and the peak of 163.7 eV can be S─S. The peak of 168.6 eV can be formed by the oxidation of CuS during self-polymerization of DA (Fig. S2b, ESI†).35,36

In order to further confirm the composition of CuS@PDA, the FTIR of CuS@PDA, CuS and PDA were measured (Fig. S2c, ESI†). The spectra show N─H scissoring at 1510 cm−1, C═C stretching at 1600 cm−1, and the stretching vibration of phenolic O─H and N─H at 3420 cm−1, which are the signatures of the PDA.37,38 The peaks appearing at 1120 cm−1 and 617 cm−1 are attributed to the C─O stretching and Cu─S vibration of CuS, respectively.3,39 It indicates that CuS@PDA was prepared successfully.

Moreover, CuS@PDA has an absorption peak at 850 nm as observed by UV-vis-NIR spectroscopy (Fig. 2a) similar to that of CuS nanoparticles.23,26,27 Both CuS@PDA and PDA have a wide absorption from 700 to 1000 nm. It proves that CuS@PDA successfully combines CuS and PDA. Furthermore, the absorbance of CuS@PDA is stronger than PDA at the same concentration (200 μg mL−1), suggesting that the CuS@PDA nanoparticles are superior to PDA for photothermal therapy.

Fig. 2.

(a) UV-vis-NIR absorbance spectrum of CuS, PDA and CuS@PDA (200 μg mL−1). (b) Zeta potential of CuS@PDA, CuS@PDA–PEI, CuS@PDA–FA water solution. (c) Time–temperature curves of CuS, PDA, CuS@PDA and CuS@PDA–FA nanocomposites (400 μg mL−1) under 808 nm laser irradiation (1.5 W cm−2). (d) Time–temperature curves of CuS@PDA–FA (200 μg mL−1) with various laser power densities.

We also explored how PEI and FA modified CuS@PDA. As shown in Fig. 2b, the zeta potential of CuS@PDA is negative (−31.1 ± 0.8 mV) due to the existence of ─OH groups on the surface, and it becomes positive (12.4 ± 0.3 mV) due to the introduction of the amino group when PEI is connected with the nanoparticles. The zeta potential of CuS@PDA–FA becomes decreased (4.5 ± 0.3 mV), because the formation of amide bonds consume positively charged amino groups on the surface of the nanoparticles. The positive zeta potential of CuS@PDA–FA enables the nanocomposites to more readily associate with the cancer cells, since they held strong electrostatic attraction for negatively charged cell membranes.

The FTIR spectra of CuS@PDA, CuS@PDA–PEI, CuS@PDA–FA were also shown in Fig. S2d (ESI†). After coating PEI, the characteristic peaks at 3420 cm−1 of N─H are enhanced, owing to the introduction of ─NH2 groups. The peak at 1620 cm−1 is attributed to N─H bending vibration.40 After binding FA, a weak peak observed at 847 cm−1 is attributed to the aromatic bending of FA.41 Moreover, the peak observed at 1631 cm−1 corresponds to the C═O stretching vibration of amide.42 The FTIR spectrum of CuS@PDA–FA indicates that FA is successfully connected the surface of the CuS@PDA–PEI nanocomposites.

Photothermal properties of CuS@PDA–FA

To study the photothermal performance of CuS@PDA–FA, a series of factors were considered, e.g., concentration and laser power density. The photothermal capacity of CuS@PDA NPs was compared with the capacity of citrate coated CuS NPs and PDA NPs, respectively. Fig. 2c shows that the CuS@PDA had a better photothermal effect than CuS or PDA. After 10 min of irradiation (1.5 W cm−2), the temperature of CuS@PDA solution at the concentration of 400 μg mL−1 increased up to 44 °C. By contrast, the CuS solution increased to 29 °C and the PDA solution increased to 22 °C at the same experimental conditions. Although the near-infrared absorption of CuS is greater than that of CuS@PDA, CuS is less dispersed in water than CuS@PDA (Fig. S3, ESI†). We also calculated the photothermal conversion efficiency of CuS, PDA, CuS@PDA and CuS@PDA–FA. As shown in Fig. S4 (ESI†), the photothermal conversion efficiency of CuS@PDA is 48.2%. In contrast, CuS is 41.9%, and the PDA NPs we prepared is 12.5%. This result confirms that the photothermal effect of this nanocomposite is significantly improved by the combination of CuS and PDA. It was also found that the photothermal efficacy of CuS@PDA–FA is decreased (η = 42.7%) under the same conditions due to the attachment of PEI and FA on the surfaces of CuS@PDA. In this case, their photothermal efficacy is still better than that of CuS nanoparticles or PDA alone. The reasons are likely that polydopamine coating makes CuS and PDA synergistically absorb more lights and generate more heats, resulting in a higher photothermal conversion efficiency compared to CuS or PDA alone. When FA is conjugated to the nanomaterials, it might absorb some lights that could reduce the efficacy a little bit. The conjugation of folic acid molecules makes CuS@PDA–FA nanocomposites easier to enter and accumulate in breast cancer cells, which are over expressing folate receptor. With the incrementation of power density (from 0.6 to 2 W cm−2), the temperature change of CuS@PDA–FA (200 μg mL−1) increased from 13 °C to 33 °C (Fig. 2d). Moreover, Fig. S5a (ESI†) reveals that the photothermal effect of CuS@PDA–FA depends on its concentration. As expected, it is enhanced when the concentration changes from 100 to 400 μg ml−1. Meanwhile, the temperature curve of CuS@PDA–FA displays no distinct change after undergoing five cycles of laser irradiation (0.8 W cm−2, 10 min, Fig. S5b, ESI†), suggesting excellent photothermal stability of CuS@PDA–FA. Therefore, it is expected that CuS@PDA–FA would significantly enhance the PTT effects on cancer cells due to the improved photothermal performance.

DOX loading on CuS@PDA–FA and its subsequent release

In addition to its photothermal effects, CuS@PDA–FA can also be used to load chemotherapeutics (DOX) to enable the combination of chemotherapy and photothermal therapy. We loaded DOX on the surface of CuS@PDA–FA by oscillation. As illustrated in Fig. 3a, there is no absorption for CuS@PDA–FA from 450 nm to 550 nm. A characteristic absorption peak is observed at 480 nm for free DOX, while the absorption peak of CuS@PDA–FA/DOX appears at 501 nm. The red shift of the peak position implies that there is a π–π stacking interaction between DOX and CuS@PDA–FA.43 We also explored the impact of pH on loading. As shown in Fig. S5c (ESI†), the loading level is highest at pH 8.5. This could be due to the fact that CuS@PDA–FA is negatively charged when the pH of the solution is 8.5. Due to the positive charge of DOX molecules, DOX could be further loaded on the surface of CuS@PDA–FA by the electrostatic interaction between them (Fig. S5d, ESI†). All the results indicate that DOX molecules have been successfully loaded onto the CuS@PDA–FA nanocomposites. The stability of CuS@PDA–FA/DOX was also studied. As shown in Fig. S3c (ESI†), CuS@PDA–FA/DOX can be uniformly dispersed within 1 h, and then gradually settled with the increase of the standing time. After sonication treatment, the material can be redispersed uniformly (Fig. S3b, ESI†). So, we firstly ultrasonicate CuS@PDA–FA/DOX before the subsequent experiment.

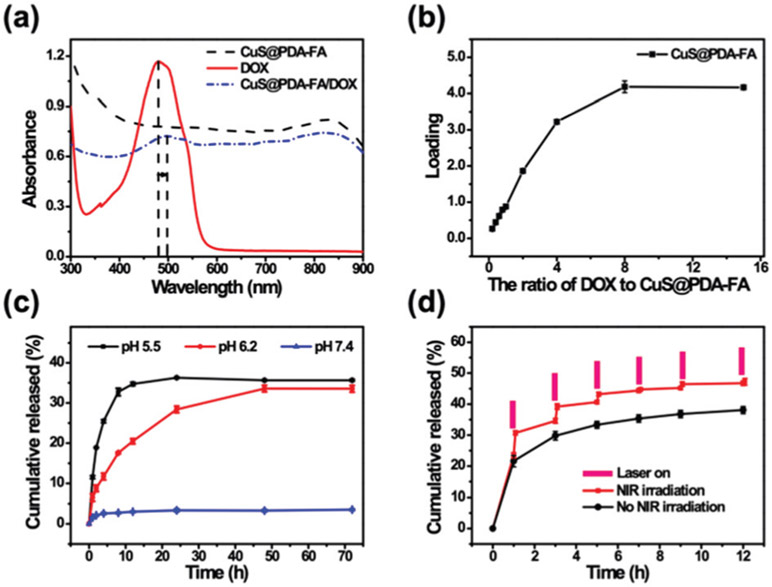

Fig. 3.

(a) UV-vis spectra of the aqueous solutions of CuS@PDA–FA, DOX, and CuS@PDA–FA/DOX. (b) DOX loading on CuS@PDA–FA in PBS buffer (pH 8.5) at various ratios of DOX to CuS@PDA–FA. (c) Cumulative DOX release of CuS@PDA–FA/DOX in PBS at pH 5.5, 6.2 and 7.4. (d) Cumulative DOX release profiles from CuS@PDA–FA/DOX nanocomposites at pH 5.5 within 12 h. The red line was obtained by NIR laser irradiation (1.5 W cm−2, 5 min).

As shown in Fig. 3b, it is observed that the loading level of DOX gradually increases with increasing DOX concentrations, and it finally reached a maximum, while the ratio of DOX to CuS@PDA–FA was 8. The maximum loading of DOX is derived to be 4.2 ± 0.2 (mg mg−1). Compared with several previously reported materials, the CuS@PDA–FA nanoparticles have a higher drug loading level (Table S1, ESI†). This is mainly due to the following three reasons: (1) there are strong electrostatic attractions between the negatively charged CuS@PDA–FA and the positively charge DOX molecules under alkaline conditions; (2) six-membered rings in the PDA structure allow for easier connections to DOX (containing benzene rings) through π–π stacking interaction; (3) the small size makes CuS@PDA–FA a large specific surface area to provide more reaction sites for DOX molecules. Moreover, these interactions do not change the performance of the drugs, but rather, they can improve the synergistic treatment efficiency. The results indicate that CuS@PDA–FA has an excellent loading capacity, which is an effective drug carrier for chemotherapy.

Meanwhile, we also explored the release of DOX in different pH conditions (Fig. 3c). Notably, the CuS@PDA–FA/DOX nanoplatforms had very low drug cumulative release at neutral conditions. The cumulative release of DOX at pH 7.4 was 3.6 ± 0.25%, while it was 36 ± 0.15% at pH 5.5. It illustrates an obvious pH-dependent increase for the release of DOX from CuS@PDA–FA/DOX, with a change of pH from 7.4 to 5.5. Under the neutral condition, CuS@PDA–FA/DOX hardly releases DOX. It can be explained that ─NH2 groups of the CuS@PDA–FA surface get protonated under acidic conditions resulting in a weakening of the electrostatic interaction between CuS@PDA–FA and DOX; hence the amount of released DOX is much higher at pH 5.5.44 These observations suggest that CuS@PDA–FA/DOX can effectively reduce the DOX release in the physiological environment (pH 7.4) and therefore reduce damage to the normal cells. As we all know, the microenvironment in the tumor is acidic (pH 5.8–7.6),45 and even more so in the intracellular environment (pH 5.0).46 The pH condition for DOX release is consistent with the pH of the cancer cell microenvironment. So, it is expected that CuS@PDA–FA could be a good pH-triggered drug-delivery nanoplatform.

Furthermore, we also studied the effect of laser irradiation on drug release. It can be up to be 47 ± 1.1% by irradiation with an 808 nm-laser (Fig. 3d), because the irradiation increases the temperature of the nanomaterials to promote the release of DOX. These results indicate that the weakly acidic environment and the laser irradiation can promote an effective and controlled drug release. Thus, CuS@PDA–FA/DOX nanocomposites could act as an actively controllable dual-stimuli response drug release nanoplatform for the chemotherapy of tumors.

In vitro biocompatibility assay

Biocompatibility of CuS@PDA–FA was evaluated before therapy experiments via the MTT assay in MCF-7 cells (breast cancer). Using citrate coated CuS and PDA for controls; we firstly investigated the cell toxicity of CuS@PDA at three concentration levels. As depicted in Fig. 4a, the cell viability decreased as the material concentration increased. The cellular viability was estimated to be 79 ± 6.6% after 20 h of incubation in the presence of 500 μg mL−1 of CuS@PDA. As a comparison, the same amount of citrate coated CuS and PDA make the cellular viability 33 ± 3.7% and 85 ± 3.3%, respectively. This suggests that the cell viability has been greatly improved due to the introduction of PDA in CuS@PDA. Subsequently, a series of concentrations of CuS@PDA–FA were used for the MTT assays. We found that CuS@PDA–FA still had good biocompatibility and low cytotoxicity after modification. The cell viability of MCF-7 cells was maintained at about 84 ± 5.7% with a high concentration of CuS@PDA–FA at 200 μg mL−1 (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Cell viability of MCF-7 cells (a) incubated with CuS, PDA and CuS@PDA and (b) incubated with CuS@PDA–FA at different concentrations.

However, the MTT results may be affected by a cell line, a time point of viability measurement and other experimental parameters. In order to verify the accuracy of the results, we also performed non-metabolic assays47 on the MCF-7 cells. As shown in Fig. 5a, the number of apoptotic cells gradually increased with the increase of nanomaterial concentration. After AO/PI staining, the cell viability data that we obtained were consistent with the MTT assay (Fig. 5b) It is expected that CuS@PDA–FA becomes a novel PTT agent and drug delivery vehicle with good biocompatibility. We also evaluated the effect of laser irradiation of different power densities on cells. Fig. S6a (ESI†) shows that no significant cytotoxicity is observed with laser irradiation (0.6, 0.8, 1.0, 1.5 and 2.7 W cm−2) for 5 min. It illustrates the brief laser exposure with low power density is safe for the cells.

Fig. 5.

(a) CLSM images of MCF-7 cells incubated with CuS@PDA–FA nanocomposites (0, 20, 80, 200 μg mL−1) for 20 h, respectively (scale bar: 100 μm). (b) Table of cell viability incubated with CuS@PDA–FA nanocomposites at various concentrations.

Cellular uptake of CuS@PDA–FA/DOX and targeting assay in vitro

The cellular uptake and targeting behavior of CuS@PDA–FA/DOX were observed by confocal fluorescence microscopy. As revealed in Fig. S7 (ESI†), fluorescence signaling of DOX in MCF–7 cells increases gradually with the increase of incubation time, which illustrates the time-dependent cellular uptake of CuS@PDA–FA/DOX by MCF-7 cells. Additionally, the cellular uptake of CuS@PDA–FA/DOX with or without NIR irradiation was explored. Fig. S8 (ESI†) reveals that the red fluorescence signal is much stronger in the laser-irradiation group compared to the nonirradiation group, demonstrating that the content of DOX in MCF-7 cells increased. This is mainly due to increased drug release and improved membrane permeability under irradiation.23 By extension, it indicates that NIR laser irradiation can improve the efficiency of chemotherapy by increasing the cellular uptake of CuS@PDA–FA/DOX.

Folic acid is a commonly used molecule for targeting cancer cells.48,49 It has many advantages, including a low molecular weight, high thermal stability, a lack of immunogenicity and a high affinity for the receptors. Together, these properties of folic acid can allow for selectivity.50,51 We compared MCF-7 cells (breast cells) with A549 cells (lung cells) to demonstrate the targeting properties of CuS@PDA–FA/DOX. It is showed in Fig. 6 that A549 cells (lung cancer) also exhibit time-dependent cellular uptake of CuS@PDA–FA/DOX, but the MCF-7 cells,52 with overexpressed folate receptors, exhibit stronger red fluorescence signals at certain incubation times than cells with low folate receptor expression (A549 cells53). The fluorescence signal of the CuS@PDA–FA/DOX group is stronger than that of the CuS@PDA–PEI/DOX group in both MCF-7 cells and A549 cells. This demonstrates that the uptake of the CuS@PDA–FA/DOX nanoconjugates by the MCF-7 cells is high, while the uptake of the MCF-7 cells to the CuS@PDA–PEI/DOX is very low. In addition, CuS@PDA–PEI/DOX and CuS@PDA–FA/DOX nanoconjugates are rarely uptaken by the A549 cells. We also compared the cell viability of MCF-7 cells with the same concentration of CuS@PDA–PEI/DOX and CuS@PDA–FA/DOX. As shown in Fig. S6b (ESI†), the cell viability is 51 ± 3.6% in the presence of 200 μg mL−1 CuS@PDA–FA/DOX, while the cell viability is 75 ± 1.5% with the same concentration of CuS@PDA–PEI/DOX. FA receptor-mediated endocytosis is the main reason of these phenomena.54 These results reveal the selectivity of folic acid as a targeting ligand. FA conjugation increases the efficiency of intracellular drug delivery55 and provides obvious accumulation of DOX in MCF-7 cells.

Fig. 6.

CLSM images of MCF-7 cells and A549 cells incubated with CuS@PDA–PEI/DOX and CuS@PDA–FA/DOX for 0.5 h and 4 h, respectively.

In vitro anticancer efficiency

As illustrated in Fig. 7, the cellular viability reached 93 ± 2.7% upon exposure to 100 μg mL−1 CuS@PDA–FA without irradiation, while the viability dropped to 49 ± 5.4% under irradiation with a power density at 0.8 W cm−2 for 5 min. It confirms that the photothermal therapy of CuS@PDA–FA is effective in MCF-7 cells. DOX molecules exhibit dose-dependent cytotoxicity in MCF-7 cells. The free DOX shows a high toxicity with 41 ± 2.9% of cellular viability at a DOX concentration of 5 μg mL−1. As a comparison, 73 ± 1.9% of cells are alive by incubating with CuS@PDA–FA/DOX containing corresponding amounts of DOX. These results indicate that the loading of DOX on CuS@PDA–FA reduces the toxicity of DOX to cells. This can be explained due to the fact that the DOX on the surface of CuS@PDA–FA is encased by PEI.54 The cells incubated with CuS@PDA–FA/DOX (200 μg mL−1) without irradiation have a higher survival rate than those incubated with free DOX (10 μg mL−1), which could be attributed to a lesser amount of DOX being released from CuS@PDA–FA/DOX and low cell cytotoxicity of CuS@PDA–FA. However, after NIR laser irradiation, the cell viability of CuS@PDA–FA/DOX drops from 52 ± 5.1% to 5.6 ± 1.4%, while the cytotoxicity of free DOX has no significant change under NIR irradiation. As one would expect to see, the combination of the photothermal effect and drug response release results in the highest cytotoxicity of CuS@PDA–FA/DOX upon laser irradiation, implying the superior therapeutic efficiency of drug-delivery by photothermal nanomaterials. Thus, the CuS@PDA–FA/DOX nanocomposites may have tremendous potential to be a nanoplatform for combining PTT and chemotherapy for the treatment of breast cancer.

Fig. 7.

Cell viability of MCF-7 cells incubated with DOX, CuS@PDA and CuS@PDA–FA/DOX nanocomposites at various concentrations with or without NIR laser irradiation (808 nm, 0.8 W cm−2). Data are displayed as a mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 5). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Conclusions

A therapeutic nanoplatform (CuS@PDA–FA/DOX) was fabricated to target and destroy cancer cells that expressed an abundance of FR on their cellular membrane by using photo thermal therapy and DOX. Combining CuS and PDA together improved the photothermal conversion efficiency (η = 48.2%) and biocompatibility of the overall material (cell viability 93 ± 2.7%, 100 μg mL−1). The nanocomposites exhibited an ultrahigh loading capacity for DOX (4.2 ± 0.2 mg mg−1). DOX release from CuS@PDA–FA/DOX was able to be triggered by laser irradiation and pH. Furthermore, owing to the synergistic effect of chemotherapy (DOX) and photothermal therapy (CuS@PDA), the CuS@PDA–FA/DOX nanocomposites could kill breast cancer cells more effectively (cell viability, 5.6 ± 1.4%) than either treatment alone. Overall, this CuS@PDA–FA/DOX therapeutic platform allows for a new potential alternative to specifically kill cancer cells rich in folate receptors through a combination of chemotherapy and photothermotherapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate financial support from National Natural Science Foundation of China (21675019, 21874014 and 21727811). WC would like to acknowledge the partial support from NIH/NCI 1R15CA199020-01A1.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/c9tb02440a

References

- 1.Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, Margolese RG, Deutsch M, Fisher ER, Jeong J-H and Wolmark N, N. Engl. J. Med, 2002, 347, 1233–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Q, Wang X, Wang C, Feng L, Li Y and Liu Z, ACS Nano, 2015, 9, 5223–5233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yi X, Chen L, Chen J, Maiti D, Chai Z, Liu Z and Yang K, Adv. Funct. Mater, 2018, 28, 1705161. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu F, Zhang Y, Chen G, Li C and Wang Q, Small, 2015, 11, 985–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minotti G, Menna P, Salvatorelli E, Cairo G and Gianni L, Pharmacol. Rev, 2004, 56, 185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song G, Wang Q, Wang Y, Lv G, Li C, Zou R, Chen Z, Qin Z, Huo K, Hu R and Hu J, Adv. Funct. Mater, 2013, 23, 4281–4292. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Teh C, Li M, Ang CY, Tan SY, Qu Q, Korzh V and Zhao Y, Chem. Mater, 2016, 28, 7039–7050. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeng C, Shang W, Liang X, Liang X, Chen Q, Chi C, Du Y, Fang C and Tian J, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2016, 8, 29232–29241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Y, He K, Chen G, Leow WR and Chen X, Chem. Rev, 2017, 117, 12893–12941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pang X, Wang J, Tan X, Guo F, Lei M, Ma M, Yu M, Tan F and Li N, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2016, 8, 13819–13829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qi D, Liu Z, Liu Y, Jiang Y, Leow WR, Pal M, Pan S, Yang H Wang Y, Zhang X, Yu J, Li B, Yu Z, Wang W and Chen X, Adv. Mater, 2017, 29, 1702800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai P, Leow WR, Wang X, Wu Y-L and Chen X, Adv. Mater, 2017, 29, 1605529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh N, Nayak J, Sahoo SK and Kumar R, Mater. Sci. Eng., C, 2019, 100, 453–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu X, Wu M and Zhao JX, Nanomedicine, 2014, 10, 297–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu T, Wang C, Gu X, Gong H, Cheng L, Shi X, Feng L, Sun B and Liu Z, Adv. Mater, 2014, 26, 3433–3440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Han L, Hu L-L, Chang Y-Q, He R-H, Chen M-L, Shu Y and Wang J-H, J. Mater. Chem. B, 2016, 4, 5178–5184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iannazzo D, Pistone A, Celesti C, Triolo C, Patané S, Giofré VS, Romeo R, Ziccarelli I, Mancuso R, Gabriele B, Visalli G Facciolà A and Di Pietro A, Nanomaterials, 2019, 9, 282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bratovš A, Kramer L, Mikhaylov G, Vasiljeva O and Turk B, Biochimie, 2019, 166, 94–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdelaziz HM, Freag MS and Elzoghby AO, in Nanotechnology-Based Targeted Drug Delivery Systems for Lung Cancer, ed. Kesharwani P, Academic Press, 2019, pp. 95–121, DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-12-815720-6.00005-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen G, Ma B, Wang Y, Xie R, Li C, Dou K and Gong S, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2017, 9, 41700–41711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurtoglu YE, Navath RS, Wang B, Kannan S, Romero R and Kannan RM, Biomaterials, 2009, 30, 2112–2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen X, Liu Z, Parker SG, Zhang X, Gooding JJ, Ru Y, Liu Y and Zhou Y, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2016, 8, 15857–15863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y, Liu X, Deng G, Sun J, Yuan H, Li Q, Wang Q and Lu J, Nanoscale, 2018, 10, 2866–2875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cao M, Lu S, Wang N, Xu H, Cox H, Li R, Waigh T, Han Y, Wang Y and Lu JR, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2019, 11, 16357–16366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen L, Feng W, Zhou X, Qiu K, Miao Y, Zhang Q, Qin M, Li L, Zhang Y and He C, RSC Adv., 2016, 6, 13040–13049. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y, Lu W, Huang Q, Li C and Chen W, Nanomedicine, 2010, 5, 1161–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lakshmanan SB, Zou X, Hossu M, Ma L, Yang C and Chen W, J. Biomed. Nanotechnol, 2012, 8, 883–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Z, Macharia DK, Chen W, Yu N, Yang C, Hu J and Chen Z, Rev. Nanosci. Nanotechnol, 2016, 5, 93–118. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han L, Hao Y-N, Wei X, Chen X-W, Shu Y and Wang J-H, ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng, 2017, 3, 3230–3235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo L, Yan DD, Yang D, Li Y, Wang X, Zalewski O, Yan B and Lu W, ACS Nano, 2014, 8, 5670–5681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu F, Wang J, Yang L and Zhu J-J, Chem. Commun, 2015, 51, 9447–9450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Han L, Zhang Y, Chen X-W, Shu Y and Wang J-H, J. Mater. Chem. B, 2016, 4, 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ding X, Liu J, Liu D, Li J, Wang F, Li L, Wang Y, Song S and Zhang H, Nano Res., 2017, 10, 3434–3446. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Y, Ai K, Liu J, Deng M, He Y and Lu L, Adv. Mater, 2013, 25, 1353–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song X, Li X, Wei D, Feng R, Yan T, Wang Y, Ren X, Du B, Ma H and Wei Q, Biosens. Bioelectron, 2019, 126, 222–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ge R, Lin M, Li X, Liu S, Wang W, Li S, Zhang X, Liu Y, Liu L, Shi F, Sun H, Zhang H and Yang B, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2017, 9, 19706–19716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fu J, Chen Z, Wang M, Liu S, Zhang J, Zhang J, Han R and Xu Q, Chem. Eng. J, 2015, 259, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang J, Zhu L, Zhu L, Zhu B and Xu Y, Langmuir, 2011, 27, 14180–14187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pal M, Mathews NR, Sanchez-Mora E, Pal U, Paraguay-Delgado F and Mathew X, J. Nanopart. Res, 2015, 17, 301. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hernaez M, Acevedo B, Mayes AG and Melendi-Espina S, Sens. Actuators, B, 2019, 286, 408–414. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park J, Park SS, Jo N-J and Ha C-S, J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol, 2019, 19, 6217–6224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Depan D, Shah J and Misra RDK, Mater. Sci. Eng., C, 2011, 31, 1305–1312. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang C, Bai J, Liu Y, Jia X and Jiang X, ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng, 2016, 2, 2011–2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Y, Chang Y-Q, Han L, Zhang Y, Chen M-L, Shu Y and Wang J-H, J. Mater. Chem. B, 2017, 5, 6882–6889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mashima T, Sato S, Sugimoto Y, Tsuruo T and Seimiya H, Oncogene, 2008, 28, 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Padilla-Parra S, Matos PM, Kondo N, Marin M, Santos NC and Melikyan GB, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 2012. 109, 17627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stepanenko AA and Dmitrenko VV, Gene, 2015, 574, 193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Suriamoorthy P, Zhang X, Hao G, Joly AG, Singh S, Hossu M, Sun X and Chen W, Cancer Nanotechnol., 2010, 1, 19–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Low PS, Henne WA and Doorneweerd DD, Acc. Chem. Res, 2008, 41, 120–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lin L, Xiong L, Wen Y, Lei S, Deng X, Liu Z, Chen W and Miao J Biomed. Nanotechnol, 2015, 11, 531–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang L, He J, Wen Y, Yi W, Li Q, Lin L, Miao X, Chen W and Xiong L, J. Biomed. Nanotechnol, 2016, 12, 1348–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li K, Jiang Y, Ding D, Zhang X, Liu Y, Hua J, Feng SS and Liu B, Chem. Commun, 2011, 47, 7323–7325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hwa Kim S, Hoon Jeong J, Chul Cho K, Wan Kim S and Gwan Park T, J. Controlled Release, 2005, 104, 223–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Y, Liu X, Deng G, Wang Q, Zhang L, Wang Q and Lu J, J. Mater. Chem. B, 2017, 5, 4221–4232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Poudel BK, Hwang J, Ku SK, Kim JO and Byeon JH, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2019, 11, 17193–17203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.