Abstract

Grb2 is an adaptor protein connecting the epidermal growth factor receptor and the downstream Son of sevenless 1 (SOS1), a Ras-specific guanine nucleotide exchange factor (RasGEF), which exchanges GDP by GTP. Grb2 contains three SH domains: N-terminal SH3 (nSH3), SH2, and C-terminal SH3 (cSH3). The C-terminal proline-rich (PR) domain of SOS1 regulates nSH3 open/closed conformations. Earlier, several nSH3 binding motifs were identified in the PR domain. More recently, we characterized by nuclear magnetic resonance and replica exchange simulations possible cSH3 binding regions. Among them, we discovered a cSH3-specific binding region. However, how PR binding at these sites regulates the nSH3/cSH3 conformation has been unclear. Here, we explore the nSH3/cSH3 interaction with linked and truncated PR segments using molecular dynamics simulations. Our 248 μs simulations include 620 distinct trajectories, each 400 ns. We construct the effective free energy landscape to validate the nSH3/cSH3 binding sites. The nSH3/cSH3–SOS1 peptide complex models indicate that strong peptide binders attract the flexible nSH3 n-Src loop, inducing a closed conformation of nSH3; by contrast, the cSH3 conformation remains unchanged. Inhibitors that disrupt the Ras–SOS1 interaction have been designed; the conformational details uncovered here may assist in the design of polypeptides inhibiting Grb2–SOS1 interaction, thus SOS1 recruitment to the membrane where Ras resides.

I. INTRODUCTION

Growth factor receptor bound protein 2 (Grb2) is an adaptor protein that modulates cell signaling by connecting the upstream receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) and the downstream Ras-specific guanine nucleotide exchange factors (RasGEFs).1–4 In response to a cell growth signal, the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), a family member of RTK, phosphorylates its kinase domain and associates with Grb2, releasing the autoinhibited Grb2 homodimer.5,6 Active monomeric Grb2 is capable of recruiting the RasGEF, Son of sevenless 1 (SOS1), to the cell membrane.7,8 Active SOS1 exchanges GDP by GTP, activating small GTPase Ras.9–11 Active Ras leads to cell proliferation through two main signaling pathways: mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK, Raf/MEK/ERK) and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/mTOR.12–15 Oncogenic mutations in three Ras isoforms, H-Ras, N-Ras, and K-Ras, result in one third of human somatic cancers. Since targeting oncogenic Ras remains extremely difficult, efforts focus on drugging Ras upstream, SOS1, Grb2, and EGFR or downstream Raf and PI3Kα.16–19 Grb2–SOS1 interaction has attracted considerable attention in the clinics, and recent peptide inhibitors interrupting Grb2–SOS1 interaction successfully suppressed cancer cells.20–25

Grb2 contains three Src homology (SH) domains: two SH3 domains connected by SH2. The N-terminal SH3 (nSH3, residues 1-58) and C-terminal SH3 (cSH3, residues 159-217) domains locate at both ends of the SH2 domain (residues 60-152). The SH2 domain recognizes the C-terminal phosphorylated motif (pYxxM, where pY represents phosphorylated tyrosine, and x is any natural amino acid) of EGFR, and both nSH3/cSH3 domains accommodate the SOS1 proline-rich (PR) domain (residues 1014-1333).26–28 While the SH2 domain contains seven β-strands flanked by two α-helices, nSH3/cSH3 conserve a β-barrel-like structure with five antiparallel β-strands, β1 to β5, a short 310 helix, α1, as well as three loops including RT, n-Src, and distal loops [Fig. 1(a)].29–31 The RT nomenclature reflects the observations that mutations of arginine and threonine residues within this SH3 loop in Src tyrosine kinase are important for transforming activity. The prominent RT and n-Src loops as well as β3, β4, and α1 are involved in the association of the nSH3/cSH3 with the peptides. Even though nSH3/cSH3 have high sequence identity (41%), they prefer distinct ligand motifs, e.g., PxxPxR for nSH3 and PxxxRxxKP for cSH3.32–34 nSH3/cSH3-binding partners typically form a polyproline type II (PPII) helix, followed by one or more positively charged residues, arginine or lysine.35,36 When searching for the typical nSH3/cSH3 binding motifs in the SOS1 PR region, we identified four PxxPxR motifs for nSH3, but none of the PxxxRxxKP motifs for cSH3.

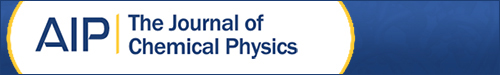

FIG. 1.

Grb2 nSH3/cSH3 domains and the sequence of the SOS1 proline-rich (PR) domain. (a) The available NMR/crystal structures of nSH3 (residues 1-58) and cSH3 (residues 159-217) are nSH3–SOS1 VPPPVPPRRR (PDB: 1AZE) and cSH3–Gab2 APPPRPPKP (PDB: 2W0Z). Both nSH3/cSH3 contain five β-strands (β1, β2, β3, β4, and β5) and three loop regions (RT, n-Src, and distal loops). The 310 helix, α1, is unfolded in the nSH3/cSH3 binding complexes. The polar, non-polar, positively charged, and negatively charged residues/atoms are colored by green, white, blue, and red, respectively. The backbone of nSH3/cSH3 binding ligands is indicated by the orange tube, and the side chains are shown as sticks. The critical residues D15, E16, and D33 of nSH3 and E174 of cSH3, involved in the interaction with the peptides are marked. (b) Sequence of the unstructured SOS1 PR domain (residues 1014-1333). The experimentally tested segments are labeled S1 to S10.

Experimental studies uncovered possible nSH3/cSH3 binding sites on the SOS1 PR domain.32,37 We and others tested ten PR segments, denoting them S1–S10 [Fig. 1(b)]. Sequence analysis indicated that S1, S2, and S10 contain the R/KxxK motif, and S4, S5, S6, and S9 involve the PxxPxR motif. The binding data for these ten segments indicated that nSH3 has binding affinity for S4, S5, S6, and S9 (KD < 200 µM), while cSH3 displays binding affinity for S4 and S10 (KD < 200 µM).37 The S4 peptide (PVPPPVPPRRRP) exhibits the highest affinity for both nSH3 (KD ∼ 40 µM) and cSH3 (KD ∼ 140 µM) due to a three consecutive arginines (“RRR”) sequence.32 The mutually exclusive nSH3/cSH3 binding to S4 suggested that cSH3 may use an alternative binding site in the PR region with the S10 segment.37 The SOS1 PR domain with deletion of S4, S5, S6, and S9 segments displays strong binding affinity for Grb2 in vitro.38 This suggests that nSH3 and cSH3 can have multiple binding motifs of the SOS1 PR domain beyond the PxxPxR motif of the S4, S5, S6, and S9 segments.

To comprehensively investigate the cryptic nSH3/cSH3 binding sites on the SOS1 PR domain, we construct computational models of nSH3/cSH3 associating with all possible truncated SOS1 PR segments. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are applied to validate the stability of each complex. The effective free energy landscape of nSH3/cSH3–SOS1 reveals the most probable nSH3/cSH3 binding sites. The structural details show that the SOS1 PR segments regulate the nSH3 open/closed conformation, albeit retaining the cSH3 conformation. Importantly, the simulated complexes also provide a structural view of the unsolved nSH3/cSH3–SOS1 interactions. By providing the conformational details of nSH3/cSH3 interacting with the various SOS1 PR segments, our results may help the development of peptide inhibitors to block Grb2–SOS1 interaction, thus SOS1 recruitment to the membrane, Ras GDP/GTP nucleotide exchange, and consequently activation.

II. RESULTS

A. Simulations of nSH3/cSH3–SOS1 complexes define the binding interfaces

During the MD simulations, we observed that conformations of nSH3/cSH3-favored SOS1 PR peptides fit into nSH3/cSH3 pockets and form stable nSH3/cSH3–SOS1 complexes. By contrast, unfavorable SOS1 peptides dissociated from nSH3/cSH3. Distributions of all simulated SOS1 PR peptides on the surfaces of nSH3/cSH3 clearly delineate highly populated binding interfaces [Fig. 2(a)]. To define interface residues, we calculated contact probability between nSH3/cSH3 and SOS1 PR peptides [Fig. 2(b)]. As indicated in the figure, residues of nSH3/cSH3 with contact probability greater than one standard deviation are defined as nSH3/cSH3 interface residues. The binding interfaces are mainly composed of three residue clusters: RT loop, n-Src loop to β3, and β4 to α1. For nSH3, Y7, T12, A13, D14, and D15 are in the RT loop; Q34, N35, and W36 are located in the n-Src loop and β3; F47, P49, K50, N51, and Y52 are in β4 and α1. Similarly, for cSH3, L164, F165, D166, F167, D168, Q170, and E171 are in the RT loop; D190, P191, N192, and W193 are in the n-Src loop and β3; M204, P206, R207, N208 and Y209 are in β4 and α1. Noticeably, cSH3 has 16 interface residues, which is greater than the 13 interface residues of nSH3. Even though the interface residues involved in the cSH3–SOS1 interaction show higher contact probabilities than those in the nSH3–SOS1 interaction, the larger number of cSH3 interface residues suggests that cSH3 has less specificity for binding to SOS1 PR peptides.

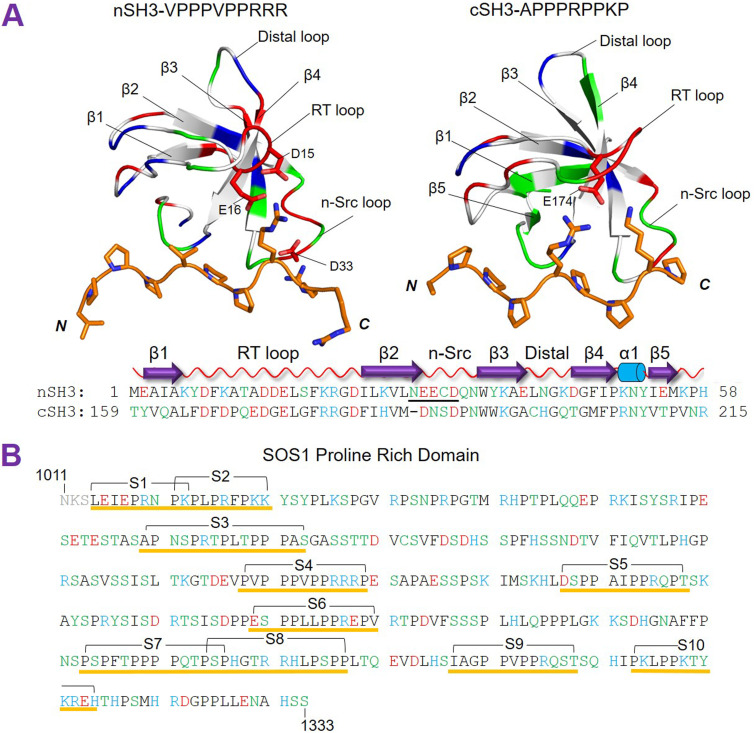

FIG. 2.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations elucidate the interface of nSH3/cSH3–SOS1. (a) During the simulation, the SOS1 PR peptides can fully bind the nSH3/cSH3, only partially bind, and dissociate. Superimposing all 309 average structures of the nSH3/cSH3–SOS1 complex indicates the most frequent contact regions. The surface of nSH3/cSH3 is colored from blue (0, low contact probability) to red (1, high contact probability). (b) Residues with one standard deviation above the average contact probability are viewed as surface residues and indicated for nSH3 and cSH3. (c) The contact probabilities of SOS1 PR residues are obtained from the interaction with the surface residues of nSH3/cSH3. The threshold of the average contact probability plus one standard deviation is shown by the red horizontal line, and the residues above the threshold are colored blue (positively charged residues, arginine or lysine) and red (non-positively charged residues). Segments with existing experimental data are labeled S1–S10.

To reveal the interface residues of the SOS1 PR domain, we projected the nSH3/cSH3 interface residues onto the PR region. In the projection, we considered the contact probabilities between the SOS1 residues and the nSH3/cSH3 interface residues [Fig. 2(c)]. The threshold (red horizontal line) was set as the average plus one standard deviation of the probability. The high contact probabilities suggest likely nSH3/cSH3 binding sites. On the probability distribution, we labeled the experimentally defined SOS1 PR peptides, S1 to S10, based on our previous work.37 Regions with high contact probability typically contain the PxxP motif followed by R/K, which facilitates the formation of the stable nSH3/cSH3–SOS1 complex (Fig. S1). Noticeably, some regions in the PR domain also exhibit high contact probability despite partial binding of the SOS1 peptide to nSH3/cSH3. These can be seen in the interactions of S1, S3, and S8 with nSH3/cSH3. In the absence of the non-polar interaction, a salt bridge interaction of R1019 (S1), R1084 (S3), and R1270/R1271 (S8) with D15 (nSH3) and E171 (cSH3), respectively, marginally prevents dissociation of the peptide (Fig. S2). However, without any R/K in S7, we observed complete dissociation of the peptide from nSH3/cSH3.

B. The effective free energy validates the multiple binding sites on SOS1 PR domain

Our simulations support the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) data that indicated that the interactions of the SOS1 peptides with the nSH3/cSH3 domains of Grb2 are stable. Furthermore, we observed that the peptides with sequences shifted by one or more residues from the experimental peptides adjust their nSH3/cSH3 binding sites, converging their conformations to the experimental peptides. For example, the cSH3–S5−1,+1 complex exhibits a final structure highly similar to cSH3–S5 (Fig. S3). Here, ±n represents the residue number shifts in the N-terminal (−) or the C-terminal (+) direction. Similarly, cSH3–S6−1,+1 converges to cSH3–S6, and cSH3–S9−3,+1 converges to cSH3–S9 (Figs. S4 and S5).

The specific atom–atom interactions were observed in multiple nSH3/cSH3–SOS1 systems. Based on these observations, we calculated contact probabilities and derived the effective free energy. In the calculations, the contact probabilities of the same atom–atom interaction in different systems were converted into the partition function, which can be applied to the effective free energy landscape. For the nSH3–SOS1 interaction, S4 exhibits the most negative value of the effective free energy, followed by S3, S6, S8, S5, S2, S9, S10, S1, and S7 [Fig. 3(a)]. The calculated effective free energy shows a good correlation with the experimental Gibbs free energy,37 extracted from the experimental KD values, with the correlation coefficient of 0.72. By contrast, cSH3 yields the distinct effective free energy landscape [Fig. 3(b)]. Unlike nSH3, cSH3 exhibits the most negative value of the effective free energy with S10, followed by S2, S4, S9, S5, S6, S3, S1, S8, and S7, with the correlation coefficient of 0.67.

FIG. 3.

The effective free energy landscape and the correlation with experimental affinities. (a) nSH3–SOS1 shows the most negative effective free energy for S4, followed by S3, S6, S8, S5, S2, S9, S10, S1, and S7. The calculated free energy has a correlation coefficient r = 0.72 with the available experimental affinity data. (b) cSH3–SOS1 exhibits a distinct pattern of the effective free energy landscape compared to nSH3–SOS1 with the most negative energy for S10, followed by S2, S4, S9, S5, S6, S3, S1, S8, and S7. The correlation coefficient to the experimental affinity is 0.67. Affinity data with poor statistics such as nSH3–S1/S3/S7 and cSH3–S8 are excluded, and cSH3 binding to S1, S3, and S7 was not detected.

The calculated free energy predicts the stability of complex formation. However, some conformations yield a low free energy value with unstable complex formation. For example, S3 has the second negative value of the effective free energy but exhibits partial binding, marginally attaching to nSH3 D15 through a single salt bridge with R1084 [Fig. S2(a)]. This prompted us to employ the average structures and the root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) of each system in order to define probable binding modes in the nSH3/cSH3–SOS1 interaction. Stable nSH3/cSH3–SOS1 complexes require hydrophobic matching and multiple salt bridge formations between nSH3/cSH3 and SOS1. Based on this, we can designate the most stable complexes as nSH3–S2−3/S4/S5/S6/S9/S10−3 and cSH3–S2/S4/S5/S6/S9/S10 (Fig. S6).

C. The nSH3 n-Src loop strengthens the interaction with SOS1, inducing closed nSH3 conformation

nSH3 forms a stable complex with S2−3, S4, S5, S6, S9, and S10−3. S4, S5, S6, and S9 contain the typical nSH3 binding PxxPxR motif. S2−3 and S10−3 have the PxPxPR and PxxPxK motifs, respectively. Within the PxxPxR motif, S4, S5, S6, and S9 use arginine to form salt bridges with nSH3 D15 and D16. However, the interaction details of individual complexes vary [Fig. 4(a)]. For example, only S5 and S9 fit well into the nSH3 hydrophobic pocket formed by Y7, W36, and Y52. S4 lacks the interaction with Y7 but forms an additional salt bridge with D33. S5 A1181 forms a hydrogen bond (H-bond) with nSH3 N51, and S6 loses the non-polar interaction with both Y7 and Y52. By contrast, S2−3 only has the non-polar interaction with Y52 and establishes a salt bridge between K1029 and nSH3 D14. S10−3 K1308 forms a salt bridge with nSH3 D15, and its PxxP motif fits into the nSH3 hydrophobic pocket formed by Y7, W36, and Y52 (Fig. S6). S10−3 Y1310 forms an H-bond with nSH3 D33, resulting in the n-Src loop approaching S10−3.

FIG. 4.

Structural details of nSH3–S4/S5/S6/S9 complexes and the nSH3 opened/closed conformations regulated by SOS1 PR peptides. (a) The average structures of nSH3 are colored white, and the peptides S4, S5, S6, and S9 are colored blue, cyan, yellow, and purple, respectively. The nSH3 residues with contact probability greater than 50% for SOS1 peptides are indicated. The critical nSH3 D15 and E16 form salt bridges with S4 R1156, S4 R1158, S5 R1185, S6 R1217, and S9 R1295. The additional salt bridge of nSH3 D33 with S4 R1157 results in nSH3 having stronger affinity for S4 than S5, S6, and S9. (b) By overlaying the average structures, the nSH3 open/closed conformations modulated by the n-Src loop are observed. The average structures of nSH3 are colored green, blue, cyan, yellow, purple, and pink when binding to S2−3, S4, S5, S6, S9, and S10−3, respectively, and apo-nSH3 is colored white. The color code applies to panels (c)-(e). While the apo-nSH3 has open conformation, the strongest binding of nSH3–S4 has a closed conformation. The critical residues D15 on the RT loop and D33 on the n-Src loop are indicated. (c) The histogram of distances r between D15 and D33 quantifies the magnitude of nSH3 open/closed conformations and shows that rS2* > rapo > rS6 > rS5 > rS9 > rS10* > rS4, where S2* and S10* denote S2−3 and S10−3, respectively. (d) The reciprocal of distance rD15–D33 against interaction energy shows a negative correlation, suggesting that the closed conformation induces a more negative interaction energy. (e) Principal component analysis (PCA) for nSH3–S2*/S4/S5/S6/S9/S10* shows that nSH3 has similar conformations when binding to S4, S5, and S9. nSH3 binding to PxxPxR (S4, S5, S6, and S9) is separated from binding to PxxPxK (S2−3 and S10−3). When bound to S6, the nSH3 structure is closer to apo-nSH3.

By superimposing the average structures of all nSH3–S2−3/S4/S5/S6/S9/S10−3 complexes, we observed that nSH3 exhibits open/closed conformations regulated by the n-Src loop [Fig. 4(b)]. The distance r between D15 of the RT loop and D33 of the n-Src loop can quantify the magnitude of nSH3 conformational changes. We found that rS2* > rapo > rS6 > rS5 > rS9 > rS10* > rS4 [Fig. 4(c)], where S2* and S10* denote S2−3 and S10−3, respectively. The reciprocal distance between D15 and D33 negatively correlates with the interaction energy of nSH3–SOS1, indicating that the closer conformation tends to have stronger interaction [Fig. 4(d)]. Although nSH3–S10−3 exhibits the closed conformation, the interaction is reduced due to replacement of arginine with lysine. Principal component analysis (PCA) suggests that nSH3 has similar conformations when binding to S4, S5, and S9 [Fig. 4(e)]. However, for S6 (ESPPLLPPREPV) with the PxxPxR motif, the glutamic acid following arginine induces a repulsive force with D33. As a result, the conformation of nSH3–S6 is more similar to that of apo-nSH3.

D. No conformational change of cSH3 upon binding to SOS1

In the cSH3–SOS1 interaction, we observed that cSH3 stably forms a complex with S2, S4, S5, S6, S9, and S10, even though none of these contains the typical cSH3 PxxxRxxKP binding motif. Among them, S2, S4, and S10 form a large number of salt bridges with cSH3 residues. cSH3 E171 and E174 form salt bridges with R1026/K1029 (S2), R1156/R1158 (S4), and K1308/K1311 (S10) [Fig. 5(a)]. For S5, S6, and S9, the arginine residue at the end of the sequence only interacts with cSH3 E174 (Fig. S6). The interfaces between cSH3 and SOS1 PR segments vary. S4, S5, S6, and S9 fit well into the cSH3 hydrophobic pocket formed by F165, W193, and Y206. However, S2 lacks the interaction with F165 and Y209, and similarly, S10 loses the interaction with F165. Noticeably, S4 R1157 and S10 R1312 form additional salt bridges with D190 and strengthen the interaction with cSH3.

FIG. 5.

The structural details of cSH3–S2/S4/S10 complexes and the cSH3 conformation. (a) The average structures of cSH3 are colored white, and the peptides S2, S4, and S10 are colored green, blue, and pink, respectively. The cSH3 residues with contact probability greater than 50% for SOS1 peptides are indicated. The cSH3 uses both E174 and E171 forming the two-to-two salt bridges with S2 R1026 and K1029, S4 R1156 and R1158, and S10 K1308 and K1311. S4 R1157 and S10 R1312 could form additional salt bridges with cSH3 D190, enhancing the interaction of cSH3–S4 and cSH3–S10. (b) The superposition of average structures shows little difference among cSH3–S2/S4/S5/S6/S9/S10, suggesting that cSH3 tends to retain its conformation. The critical E174 of the RT loop and D190 of the n-Src loop are indicated. The average structures of cSH3 are colored green, blue, cyan, yellow, purple, and pink when binding to S2, S4, S5, S6, S9, and S10, respectively, and apo-cSH3 is white. The color code applies to panels (c)–(e). (c) The distance between E174 and D190 is conserved among apo-cSH3 and all cSH3–SOS1 complexes. (d) The reciprocal of distance rE174–D190 is independent of the interaction energy. The interaction energy varies, but rE174–D190 remains similar, and nSH3–S2/S10 have the most negative interaction energy. (e) Due to the highly consistent conformation of cSH3, the principal component analysis (PCA) hardly clusters different groups of the cSH3–SOS1 complex. The higher affinity of cSH3–S4 and cSH3–S10 could be found at the edge of the diagram.

Superimposition of the average structures reveals that upon binding to S2, S4, S5, S6, S9, and S10, cSH3 retains the stable and consistent conformation [Fig. 5(b)]. To quantitatively measure the conformational change in cSH3, we calculated the distance between E174 in the RT loop and D190 in the n-Src loop. Our calculations show highly similar values of the distance among all cSH3–SOS1 systems including apo-cSH3 [Fig. 5(c)]. The distance between the RT and n-Src loops appears to be independent of the interaction energy between cSH3 and SOS1 PR segments [Fig. 5(d)]. PCA fails to separate the different clusters due to the highly consistent conformation of cSH3 [Fig. 5(e)]. Unlike nSH3 exhibiting open/closed conformations upon binding to the ligand, cSH3 shows limited conformational changes, regardless of ligands containing the PxxPxR or R/KxxK motifs.

III. DISCUSSION

The effective free energy exhibits higher correlation to experimental affinity data for nSH3–SOS1 than for cSH3–SOS1 interaction due to the better fitting nSH3–SOS1 interface. Through statistical analysis of the comprehensive simulations, we find that nSH3 has 13 interface residues (Y7, T12, A13, D14, D15, Q34, N35, W36, F47, P49, K50, N51, and Y52), and cSH3 has 16 interface residues (L164, F165, D166, F167, D168, Q170, E171, D190, P191, N192, W193, M204, P206, R207, N208, and Y209). The large number of the interface residues may result in less accurate energy estimation. Since the effective free energy is calculated by specific atom–atom interactions in the interface, the more interface residues cause more energy terms to be added. For example, when associating with S2, cSH3 has only three residues (E171, E174, and W193) with high contact probability (>0.5). The additional energy terms deviate from the fitted curve, reducing the correlation coefficient. Furthermore, some strong salt bridges are binding-site specific and are not reflected in the statistical analysis. For example, within the consensus PxxPxR motif, the arginine of S4, S5, S6, and S9 interacts with nSH3 E16 and cSH3 E174. However, the low contact frequency excludes nSH3 E16 and cSH3 E174 from the interface residues. Nevertheless, the non-empirical approach of the effective energy yields a fair correlation with the experimental affinity and could help explore the cryptic binding sites.

Structural convergence is only observed for the weak affinity interactions of cSH3–S5/S6/S9 (KD > 1000 µM). This implies that the energy landscape nearby S5, S6, and S9 may form a basin with shallow depth and large width. When binding to cSH3, the segments S5−1,+1, S6−1,+1, and S9−3,+1 could shift the local energy minimum and attain structures that are highly similar to cSH3–S5/S6/S9 (Figs. S3, S4, and S5). By contrast, complexes with stronger affinity such as nSH3–S4/S5/S6/S9 and cSH3–S2/S4/S10 may have deep and narrow local energy minimum, and thus, shifts by one or more residues of these SOS1 segments would result in partial association for nSH3/cSH3. S5, S6, and S9 are incapable of forming salt bridges with cSH3 E171, resulting in weak affinities. Similarly, S2 and S10 show weaker affinity for nSH3 due to the lack of salt bridges with nSH3 D15. nSH3/cSH3 binding ligands form salt bridges with both nSH3 D15 and E16 and both cSH3 E171 and E174, and the additional interaction with nSH3 D33 and cSH3 D190 could further enhance the affinity.

Upon binding to various SOS1 PR segments, nSH3 forms open/closed conformations, while cSH3 preserves its conformation. The nSH3 open/closed conformations are modulated by the n-Src loop. The fact that the nSH3 n-Src loop was not observed in the Grb2 homodimer crystal structure (PDB: 1GRI), but is present in the nSH3–VPPPVPPRRR complex (PDB: 1AZE) in solution, suggests that the nSH3 n-Src loop is flexible and could be stabilized by the nSH3 binding ligands [Figs. 1(a) and S7]. By contrast, the cSH3 n-Src loop does not regulate the closed conformation. However, the cSH3 n-Src loop participates in Grb2 homo-dimerization. Grb2 dimerizes by forming H-bonds between SH2 E87 and cSH3 Y160 as well as between cSH3 N188 and N214 (Fig. S7).5 Y160 and N214 are located in the cSH3 N- and C-termini, and N188 is in the n-Src loop. Notably, even though cSH3 has comparable strong affinity for S4 and S10, binding to S4 shows much higher fluctuation of N188 than binding to S10 (Fig. S8). The n-Src loops in nSH3 and cSH3 have different and critical roles: the nSH3 n-Src loop strengthens the interaction with nSH3 binding ligands and regulates the nSH3 open/closed conformation; the cSH3 n-Src loop participates in Grb2 homo-dimerization and could be partially affected by cSH3 binding ligands.

To conclude, here, we carried out comprehensive simulations to investigate the interaction between Grb2 nSH3/cSH3 domains and the SOS1 PR domain. We simulated nSH3/cSH3 with continuous and truncated SOS1 PR segments and calculated the effective free energy based on the specific atom–atom interactions at the interface of nSH3/cSH3–SOS1 segments. The effective energy landscape together with the structural analysis reveals the cryptic nSH3/cSH3 binding sites on SOS1 and provides a fair correlation with the experimental affinity data. Notably, the high affinity interaction requires that nSH3/cSH3 binding ligands form salt bridges with nSH3 D15 and E16 as well as cSH3 E171 and E174. The additional interaction of nSH3 binding ligands with nSH3 D33 could further enhance the affinity and result in the nSH3 closed conformation. Taken together, our results elucidate the structural mechanism for nSH3/cSH3 interaction with truncated SOS1 segments and help the peptide design to inhibit Grb2 interactions with SOS1, thereby hindering SOS1 recruitment to the plasma membrane and blocking Ras activation. In particular, the multiple energetically favorable SOS1 segments identified here provide essential detailed data of the multiple ways SOS1 can be recruited and can aid more promising designs of peptidimers for interrupting Grb2–SOS1 interaction, blocking the Ras signaling pathway.

IV. METHODS

A. Generating initial configurations of nSH3/cSH3–SOS1 PR segments

To comprehensively investigate the interactions between nSH3/cSH3 and SOS1 PR, nSH3/cSH3–SOS1 models were constructed by taking the entire sequence of the SOS1 PR domain. The nSH3/cSH3 structures were extracted from the crystal structure of Grb2 (PDB: 1GRI),5 and the bound SOS1 peptides were modeled by using the backbone conformation of SOS1 VPPPVPPRRR (PDB: 1AZE)30 for nSH3 and Gab2 APPPRPPKP (PDB: 2W0Z)31 for cSH3. The peptide structures were extended to 12 residues and sequentially mutated to SOS1 PR (residues 1014-1333). The missing Grb2 nSH3 n-Src loop (residues 28-33) and structure extension of the SOS1 peptide were modeled by Modeller,39 and the mutations were accomplished with the CHARMM program.40 In the modeled n-Src loop, the initial structure of nSH3 is in the open conformation. Sequentially mutating a 12-residue binding peptide from the entire SOS1 PR (320 residues) yielded 309 different peptides. Superimposing the extracted nSH3/cSH3 and the mutated peptides to 1AZE and 2W0Z created 618 models for all possible nSH3/cSH3-SOS1 complexes. Apo-nSH3/cSH3 were also simulated. All complexes were solvated by the TIP3P water model that constitutes the isometric unit cell box of 64 × 64 × 64 Å3. In addition, to neutralize the system, Na+ and Cl− were added to satisfy a total ion concentration near 100 mM.

B. Atomistic molecular dynamics simulations

To generate the set of starting points for a production-ready stage, we employed MD simulations using the updated CHARMM40 all-atom additive force field.41 Our simulations closely followed the protocol described in our previous studies.11,15,42–44 A series of minimization and dynamics cycles using the steepest decent ad adopted basis Newton–Raphson algorithms were performed for the solvents around the harmonically restrained protein backbone. The pre-equilibrium minimization and dynamics simulations under the same conditions were repeated until the solvent reached 310 K. At the final pre-equilibrium stage, the harmonic restraints on the backbone were gradually released with a force constant from k = 5 kcal/mol/Å2/atom to 0 kcal/mol/Å2/atom. Each cycle with a different k value was performed for 500 000 steps with the full particle mesh Ewald (PME) electrostatics calculation. Following the pre-equilibrium stages, each independent simulation was performed for 400 ns with the Langevin temperature control that maintains the constant temperature at 310 K and the Nosé–Hoover Langevin piston pressure control that sustains the pressure at 1 atm. With 620 independent systems (thus trajectories) and 400 ns each, the time scales of our simulations reached a total of 248 µs. For the production runs, the NAMD parallel computing code (version 2.12)45 with the CHARMM40 force field on a Biowulf cluster at the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD) was employed. The average structures were taken for the last 200 ns to ensure equilibration of the system.

C. Effective free energy calculations

The calculation of the effective free energy for each system is based on the atom–atom interaction between nSH3/cSH3 and SOS1 peptides. The same atom–atom interaction in different models has different interaction probabilities. For each model, the probability shows the number of contacts over the trajectory length, obtained over the last half of the trajectories. The discrete probabilities show unnormalized distribution. The total number of contacts, N, is the sum of the contacts of each model,

| (1) |

where N0 is the biggest number of contacts and may represent the most stable state among the various models. We use the probability to obtain the partition function (dividing N by N0) and denote it as the effective partition function, Zeff,

| (2) |

In terms of Zeff, the effective free energy, Aeff, can be deduced by

| (3) |

where kB is the Boltzmann constant and T is the simulation temperature. The total effective free energy for the i-th model is a sum of contributions from salt bridges, hydrogen bonds, and non-polar interactions,

| (4) |

where j denotes the specific atom–atom interaction and AE, AH, and AN represent the effective free energy of electrostatics, hydrogen bond, and non-polar interactions, respectively.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

See the supplementary material for details of additional structural information.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Health, under Contract No. HHSN261200800001E as well as from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) – University of Maryland (UMD) Partnership for Integrative Cancer Research. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products or organization imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. This Research was supported (in part) by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research and the Intramural Research Program of the NIH Clinical Center. All simulations had been performed using the high-performance computational facilities of the Biowulf PC/Linux cluster at the National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA (https://hpc.nih.gov/).

Note: This paper is part of the JCP Special Topic on Classical Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: Codes, Algorithms, Force fields, and Applications.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chardin P., Cussac D., Maignan S., and Ducruix A., FEBS Lett. 369(1), 47–51 (1995). 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00578-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamazaki T., Zaal K., Hailey D., Presley J., Lippincott-Schwartz J., and Samelson L. E., J. Cell Sci. 115(Part 9), 1791–1802 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayer B. J., Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16(11), 691–698 (2015). 10.1038/nrm4068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu S., Jang H., Muratcioglu S., Gursoy A., Keskin O., Nussinov R., and Zhang J., Chem. Rev. 116(11), 6607–6665 (2016). 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maignan S., Guilloteau J. P., Fromage N., Arnoux B., Becquart J., and Ducruix A., Science 268(5208), 291–293 (1995). 10.1126/science.7716522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmed Z., Timsah Z., Suen K. M., Cook N. P., Lee G. R. T., Lin C. C., Gagea M., Marti A. A., and Ladbury J. E., Nat. Commun. 6, 7354 (2015). 10.1038/ncomms8354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buday L., Egan S. E., Rodriguez Viciana P., Cantrell D. A., and Downward J., J. Biol. Chem. 269(12), 9019–9023 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Margolis B. and Skolnik E. Y., J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 5(6), 1288–1299 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chardin P., Camonis J. H., Gale N. W., van Aelst L., Schlessinger J., Wigler M. H., and Bar-Sagi D., Science 260(5112), 1338–1343 (1993). 10.1126/science.8493579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cherfils J. and Chardin P., Trends Biochem. Sci. 24(8), 306–311 (1999). 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01429-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liao T.-J., Jang H., Fushman D., and Nussinov R., Biophys. J. 115(4), 629–641 (2018). 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.07.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okkenhaug K. and Rottapel R., J. Biol. Chem. 273(33), 21194–21202 (1998). 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young A., Lou D., and McCormick F., Cancer Discovery 3(1), 112–123 (2013). 10.1158/2159-8290.cd-12-0231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samatar A. A. and Poulikakos P. I., Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 13(12), 928–942 (2014). 10.1038/nrd4281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang M. Z., Jang H., and Nussinov R., Chem. Sci. 10(12), 3671–3680 (2019). 10.1039/c8sc04498h [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris V. and Kopetz S., F1000Prime Rep. 5, 11 (2013). 10.12703/p5-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNamara C. R. and Degterev A., Future Med. Chem. 3(5), 549–565 (2011). 10.4155/fmc.11.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu S., Jang H., Zhang J., and Nussinov R., ChemMedChem 11(8), 814–821 (2016). 10.1002/cmdc.201500481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liao T.-J., Jang H., Tsai C.-J., Fushman D., and Nussinov R., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19(9), 6470–6480 (2017). 10.1039/c6cp08596b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cussac D., Vidal M., Leprince C., Liu W. Q., Cornille F., Tiraboschi G., Roques B. P., and Garbay C., FASEB J. 13(1), 31–38 (1999). 10.1096/fasebj.13.1.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ye Y.-B., Lin J.-Y., Chen Q., Liu F., Chen H.-J., Li J.-Y., Liu W.-Q., Garbay C., and Vidal M., Biochem. Pharmacol. 75(11), 2080–2091 (2008). 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu Y., Nie Y., Feng Q., Qu J., Wang R., Bian L., and Xia J., Mol. Pharm. 14(5), 1548–1557 (2017). 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b00952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oneyama C., Nakano H., and Sharma S. V., Oncogene 21(13), 2037–2050 (2002). 10.1038/sj.onc.1205271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguyen J. T., Turck C. W., Cohen F. E., Zuckermann R. N., and Lim W. A., Science 282(5396), 2088–2092 (1998). 10.1126/science.282.5396.2088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gril B., Vidal M., Assayag F., Poupon M.-F., Liu W.-Q., and Garbay C., Int. J. Cancer 121(2), 407–415 (2007). 10.1002/ijc.22674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kessels H. W., Ward A. C., and Schumacher T. N., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99(13), 8524–8529 (2002). 10.1073/pnas.142224499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ettmayer P., France D., Gounarides J., Jarosinski M., Martin M.-S., Rondeau J.-M., Sabio M., Topiol S., Weidmann B., Zurini M., and Bair K. W., J. Med. Chem. 42(6), 971–980 (1999). 10.1021/jm9811007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simon J. A. and Schreiber S. L., Chem. Biol. 2(1), 53–60 (1995). 10.1016/1074-5521(95)90080-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hosoe Y., Numoto N., Inaba S., Ogawa S., Morii H., Abe R., Ito N., and Oda M., Biophys. Physicobiol. 16, 80–88 (2019). 10.2142/biophysico.16.0_80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vidal M., Goudreau N., Cornille F., Cussac D., Gincel E., and Garbay C., J. Mol. Biol. 290(3), 717–730 (1999). 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harkiolaki M., Tsirka T., Lewitzky M., Simister P. C., Joshi D., Bird L. E., Jones E. Y., O’Reilly N., and Feller S. M., Structure 17(6), 809–822 (2009). 10.1016/j.str.2009.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDonald C. B., Seldeen K. L., Deegan B. J., and Farooq A., Biochemistry 48(19), 4074–4085 (2009). 10.1021/bi802291y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schaeper U., Gehring N. H., Fuchs K. P., Sachs M., Kempkes B., and Birchmeier W., J. Cell Biol. 149(7), 1419–1432 (2000). 10.1083/jcb.149.7.1419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McDonald C. B., Seldeen K. L., Deegan B. J., Bhat V., and Farooq A., J. Mol. Recognit. 24(4), 585–596 (2011). 10.1002/jmr.1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saksela K. and Permi P., FEBS Lett. 586(17), 2609–2614 (2012). 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.04.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Terasawa H., Kohda D., Hatanaka H., Tsuchiya S., Ogura K., Nagata K., Ishii S., Mandiyan V., Ullrich A., Schlessinger J. et al. , Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 1(12), 891–897 (1994). 10.1038/nsb1294-891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liao T.-J., Jang H., Nussinov R., and Fushman D., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142(7), 3401–3411 (2020). 10.1021/jacs.9b10710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bartelt R. R., Light J., Vacaflores A., Butcher A., Pandian M., Nash P., and Houtman J. C., Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Cell Res. 1853(10), 2560–2569 (2015). 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fiser A. and Šali A., Methods Enzymol. 374, 461–491 (2003). 10.1016/s0076-6879(03)74020-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brooks B. R., Brooks C. L., A. D. Mackerell, Jr., Nilsson L., Petrella R. J., Roux B., Won Y., Archontis G., Bartels C., Boresch S., Caflisch A., Caves L., Cui Q., Dinner A. R., Feig M., Fischer S., Gao J., Hodoscek M., Im W., Kuczera K., Lazaridis T., Ma J., Ovchinnikov V., Paci E., Pastor R. W., Post C. B., Pu J. Z., Schaefer M., Tidor B., Venable R. M., Woodcock H. L., Wu X., Yang W., York D. M., and Karplus M., J. Comput. Chem. 30(10), 1545–1614 (2009). 10.1002/jcc.21287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klauda J. B., Venable R. M., Freites J. A., O’Connor J. W., Tobias D. J., Mondragon-Ramirez C., Vorobyov I., A. D. MacKerell, Jr., and Pastor R. W., J. Phys. Chem. B 114(23), 7830–7843 (2010). 10.1021/jp101759q [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jang H., Muratcioglu S., Gursoy A., Keskin O., and Nussinov R., Biochem. J. 473(12), 1719–1732 (2016). 10.1042/bcj20160031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jang H., Banerjee A., Marcus K., Makowski L., Mattos C., Gaponenko V., and Nussinov R., Structure 27(11), 1647–1659.e4 (2019). 10.1016/j.str.2019.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jang H., Zhang M., and Nussinov R., Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 18, 737–748 (2020). 10.1016/j.csbj.2020.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Phillips J. C., Braun R., Wang W., Gumbart J., Tajkhorshid E., Villa E., Chipot C., Skeel R. D., Kalé L., and Schulten K., J. Comput. Chem. 26(16), 1781–1802 (2005). 10.1002/jcc.20289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

See the supplementary material for details of additional structural information.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.