ABSTRACT

Cell death is an important facet of animal development. In some developing tissues, death is the ultimate fate of over 80% of generated cells. Although recent studies have delineated a bewildering number of cell death mechanisms, most have only been observed in pathological contexts, and only a small number drive normal development. This Primer outlines the important roles, different types and molecular players regulating developmental cell death, and discusses recent findings with which the field currently grapples. We also clarify terminology, to distinguish between developmental cell death mechanisms, for which there is evidence for evolutionary selection, and cell death that follows genetic, chemical or physical injury. Finally, we suggest how advances in understanding developmental cell death may provide insights into the molecular basis of developmental abnormalities and pathological cell death in disease.

KEY WORDS: Cell death, Apoptosis, Caspase, Non-apoptotic cell death, Linker cell-type death, LCD, Pathological cell death, Cell compartment elimination

Summary: This Primer outlines the important roles, different types and molecular players regulating developmental cell death, discusses recent findings, clarifies terminology and suggests links to developmental abnormalities and disease.

Introduction

Cell death is prevalent in and crucial for animal development (Fuchs and Steller, 2011). The notion that cell death is regulated during animal growth first emerged from studies of motoneuron development in the chick embryo. These studies led to the discovery of nerve growth factor (NGF), the first described regulator of cell survival (Hamburger and Levi-Montalcini, 1949). Research on amphibian and insect metamorphosis revealed that developmental cell death is commonplace and predictable (Glücksmann, 1965; Kerr et al., 1972; Lockshin and Williams, 1965); the term programmed cell death (PCD) was coined to acknowledge this reproducibility. Cell death plays many roles in development, from tissue sculpting, to controlling cell numbers, to quality control (Box 1). It is not surprising, therefore, that blocking cell death has severe consequences. PCD-defective mutants of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans develop to adulthood, but produce fewer progeny, grow more slowly, and exhibit nervous-system and behavior defects (Avery and Horvitz, 1987; Ellis et al., 1991; White et al., 1991). In Drosophila melanogaster and vertebrates, PCD appears to be important for viability (White et al., 1994), and vertebrate PCD defects result in developmental abnormalities and pathologies including cancer and neurodegeneration (Fuchs and Steller, 2011).

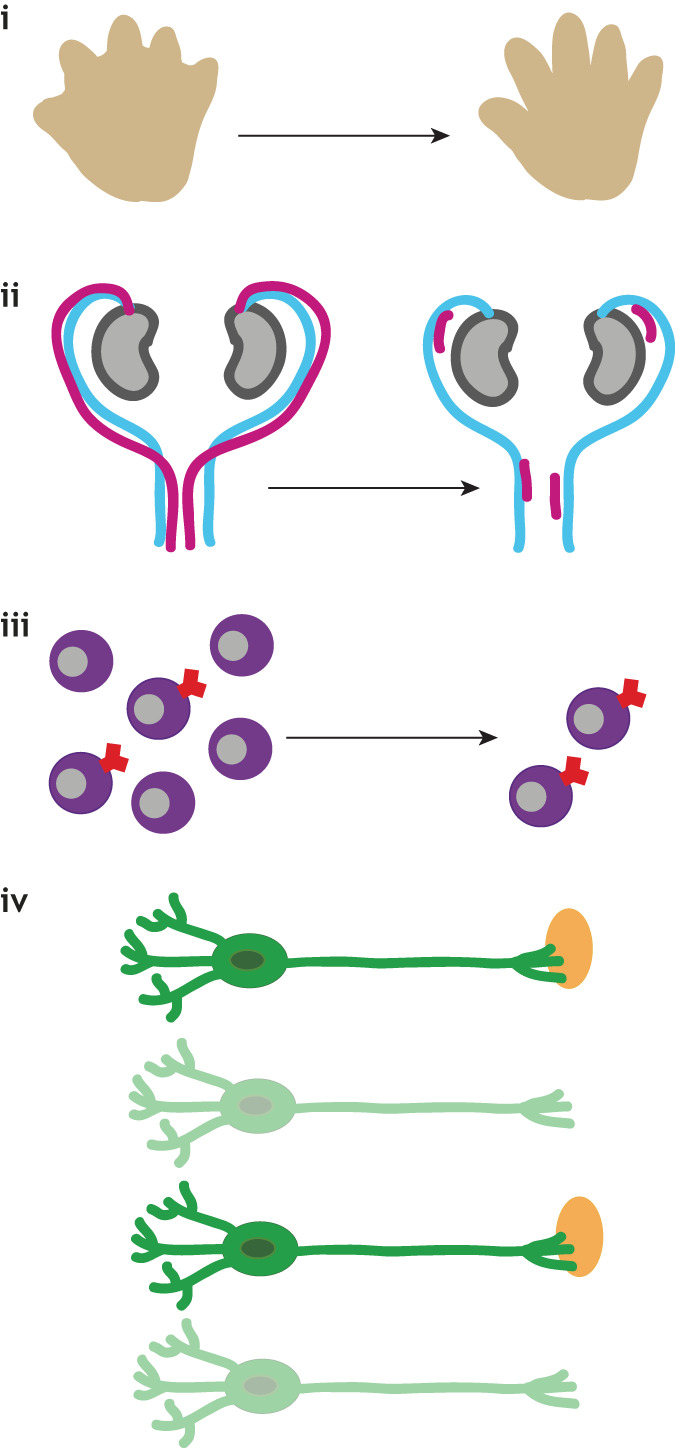

Box 1. Important roles for cell death in development.

Morphogenesis

Cell death drives morphogenesis and tissue sculpting, as during removal of inter-digital webbing [see figure (i)] (Lindsten et al., 2000), or tube hollowing, as in pro-amniotic cavity (Coucouvanis and Martin, 1995), neural tube and lens formation (Glücksmann, 1951).

Deleting structures

Vestigial or transient structures are removed by cell death. During mammalian embryogenesis, pronephric tubules (Baehrecke, 2002) and subplate neurons (Jacobson et al., 1997) die. The tadpole tail and insect larval tissues are removed during metamorphosis (Baehrecke, 2002). In mammals, Müllerian [see figure (ii)] and Wolffian ducts degrade sex-specifically in males and females, respectively (Jacobson et al., 1997).

Regulating cell number

Cell numbers are maintained through a balance between cell division and death. In developing tissues, cells are often overproduced and then removed. More than 50% of generated mammalian CNS neurons die [see figure (iii)] (Oppenheim, 1991), and 80% of oocytes in human females succumb before birth (Reynaud and Driancourt, 2000).

Quality control

Cell death also exerts protective roles, removing damaged or dangerous cells. In the immune system, auto-reactive B- and T-lymphocytes recognizing self or lacking functional receptors are eliminated [see figure (iv)] (Opferman and Korsmeyer, 2003).

Evolutionary origins

In prokaryotes, cell death may have arisen in single-cell aggregates (Shub, 1994; Yu and Snyder, 1994). In the slime mold Dictyostelium, stalk cells die during starvation-induced differentiation, to facilitate dissemination (Cornillon et al., 1994; Loomis and Smith, 1995). Cell death also occurs in plant development, driving xylem, ovule and flower formation (Greenberg, 1996). Somatic cell death early in development promotes reproduction of the green algae Volvox.

Although developmental cell death was originally imagined as a passive withering process, studies in C. elegans identified conserved cell-autonomous machinery driving cell elimination (Conradt and Horvitz, 1998; Ellis and Horvitz, 1986; Hengartner and Horvitz, 1994b; Yuan and Horvitz, 1992; Yuan et al., 1993). Thus, in development, cells fated to die activate an evolutionarily-selected self-culling cascade to cause their own demise. To date, most studies of developmental cell death use C. elegans and D. melanogaster as model systems.

In this Primer, we summarize mechanisms underlying developmental cell death and describe their control, focusing on apoptotic and non-apoptotic pathways. Next, we discuss the different ways cell death is initiated in the context of embryonic development. We also contrast developmental cell death with pathological cell death (Box 2, Table 1) and discuss repurposing of cell death pathways for eliminating subcellular compartments. We do not review dying-cell phagocytosis (efferocytosis), although rapid and efficient clearance is essential for cell elimination, and readers are directed to excellent reviews on the subject, e.g. Arandjelovic and Ravichandran (2015). Finally, although cell death has been studied for nearly a century, we highlight fascinating remaining problems that fuel current excitement.

Box 2. Pathological cell death.

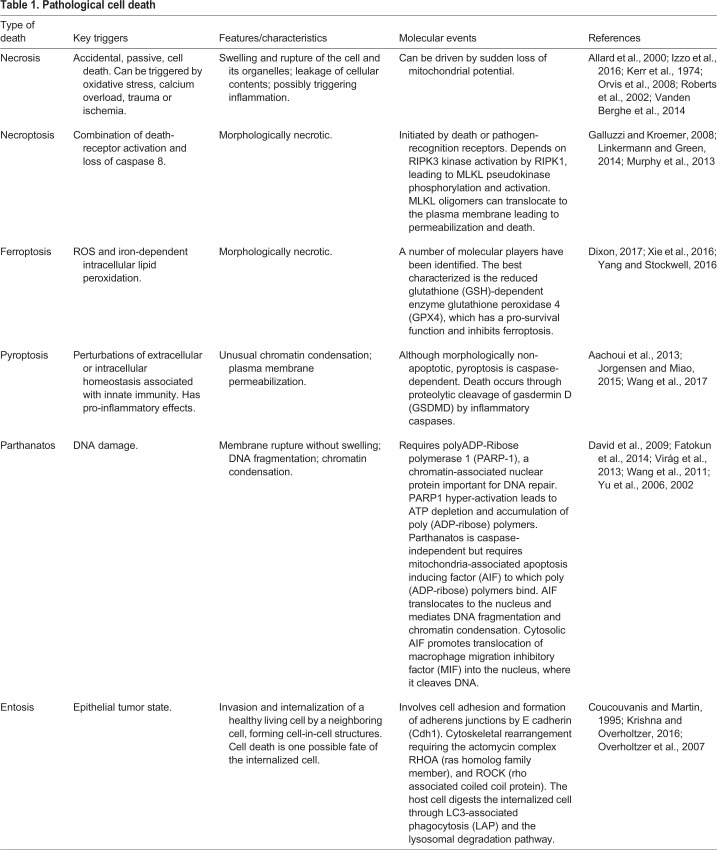

Many cell death forms occur under non-physiological conditions, including necroptosis, ferroptosis and others. In these, an essential cellular function is disrupted, leading to cell loss. The term ‘regulated cell death’ is used to group these cell death forms with apoptosis (Galluzzi et al., 2014; Tang et al., 2019). However, this is misleading, as it implies that, like apoptosis, these death forms have been evolutionarily selected for their cell-lethal functions, a claim that is unsupported. Although apoptosis can also occur in pathology, and apoptotic proteins can have non-cell-death roles, mutations in apoptotic components clearly disrupt developmental cell death. Proteins implicated in non-physiological cell death forms generally have key functions entirely unrelated to cell death, and loss of these regulators has no effect on physiological cell death. A more apt term for these cell death events is, therefore, pathological cell death, which also emphasizes their possible relevance in clinical settings.

Recognizing this issue, an attempt to link entosis, pathological death of healthy tumor cells through engulfment by neighboring tumor cells, to physiological LCD in C. elegans, revealed similarities in cell adhesion and actin localization (Lee et al., 2019). Yet, other results argue strongly against a link. Adhesion and cytoskeletal proteins are not unique markers of entosis, and mutants lacking these proteins were never shown to exhibit linker cell survival. Many LCD genes act within the linker cell and not in the engulfing cell (Abraham et al., 2007; Blum et al., 2012; Kinet et al., 2016; Malin et al., 2016), contradicting the definition of entosis as death by engulfment (Overholtzer et al., 2007). Nuclear crenellations, an early sign of cell death, precede linker cell engulfment (Keil et al., 2017), also contradicting the definition of entosis. In fact, the linker cell can die in the complete absence of engulfment (Abraham et al., 2007; Keil et al., 2017). Furthermore, linker cell engulfment is mediated by RAB-35 and ARF-6 GTPases (Kutscher et al., 2018), not implicated in entosis. Nonetheless, such efforts to link pathological cell death types to developmental processes are important, as they may uncover novel modes of developmental cell death.

Table 1.

Pathological cell death

Apoptosis

Apoptosis (Greek: ‘falling off’) is a type of PCD with a distinct ultrastructure, characterized by cytoplasm compaction, condensed chromatin and, occasionally, plasma membrane blebbing. Intracellular organelles remain morphologically intact until late in the dying process (Clarke, 1990; Kerr et al., 1972). Apoptotic cell death is prevalent during development: in C. elegans hermaphrodites, 131 of 1090 of somatic cells generated, and half of germ-line cells, die apoptotically (Sulston et al., 1983). In Drosophila, apoptosis begins at 7 h of embryogenesis (Abrams et al., 1993), and in vertebrates apoptosis is evident in early developing tissues (Bedzhov and Zernicka-Goetz, 2015). Apoptosis is regulated by a conserved caspase-dependent molecular program (Fuchs and Steller, 2011; Yuan et al., 1993).

The apoptotic machinery

Caspases

Insights into the roles of caspases in the apoptotic program came initially from C. elegans (Horvitz, 2003). Cloning of the cell-death gene ced-3, and recognition that it encodes a protein similar to mammalian IL-1β converting enzyme (caspase 1), catapulted the caspase family to recognition as apoptotic executioners (Yuan et al., 1993). Caspases (cysteine-aspartic acid proteases), a group of aspartate-directed cysteine proteases, are activated following cleavage of an inactive precursor at specific aspartates (Thornberry et al., 1992). Such activation can be either self-catalytic or via other caspases (Slee et al., 1999; Thornberry et al., 1992). In C. elegans, the caspase CED-3 promotes apoptosis (Yuan et al., 1993). Three additional caspases, CSP-1, -2 and -3, are encoded by the genome (Shaham, 1998). CSP-1 may have pro-apoptotic functions, whereas CSP-2 and CSP-3 curtail CED-3 auto-activation. Unlike loss of CED-3, mutations in these caspases only weakly influence apoptosis progression (Geng et al., 2009).

Drosophila also has several caspase genes, with three of the seven having key cell-death roles (Cooper et al., 2009). The caspase Dronc cleaves, and functions upstream of caspases Drice and Dcp-1 (Hawkins et al., 2000; Xu et al., 2006). This hierarchy, which also appears in vertebrates (Inoue et al., 2009; Slee et al., 1999), suggests subdivision of caspases to initiators, such as Dronc, or effectors, such as Drice. The assignment relies, in part, on presence or absence of a large N-terminal prodomain found in initiators but absent in effectors (Sakamaki and Satou, 2009). Nonetheless, this classification is almost certainly an oversimplification, because initiator caspases such as Dronc can promote cell death even in the absence of effector caspases (Gorelick-Ashkenazi et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2006).

The caspase family expands further in vertebrates. The human genome, for example, encodes 14 caspases (Pop and Salvesen, 2009), with initiators (caspase 2, 8, 9 and 10) and effectors (caspase 3, 6 and 7) controlling apoptosis. The remaining seven caspases do not direct cell death, having specialized functions in inflammation (Labbé and Saleh, 2008) and differentiation (Hoste et al., 2013).

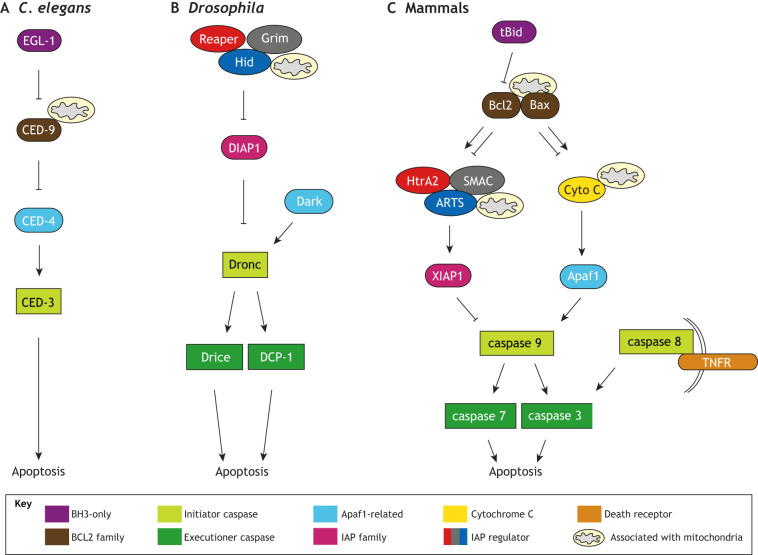

Activation of initiator caspases, and of CED-3 in C. elegans, is mediated by binding to adapter proteins, forming a super-structure called the apoptosome. The apoptosome is thought to bring pro-caspases into proximity for cross activation (Zou et al., 1999). The C. elegans apoptosome contains eight CED-4 adapter moieties, as determined by X-ray diffraction, which bind only two CED-3 caspase molecules (Qi et al., 2010) (Fig. 1A). Cryo-electron-microscope structures of the Drosophila apoptosome suggest eight copies of CED-4-like Dark (also known as dApaf-1 or HAC-1) and of Dronc (Yuan et al., 2011) (Fig. 1B). In humans, CED-4-like APAF1 assembles as a heptamer, binding three or four pro-caspase 9 proteins (Acehan et al., 2002) (Fig. 1C). Why stoichiometry of these complexes differs is not understood, nor are consequences of these differences.

Fig. 1.

Conserved apoptotic pathways. (A-C) Apoptotic cascades are initiated at the mitochondrion in C. elegans (A) and Drosophila (B) and also at the cell surface in mammals (C), resulting in caspase activation. Based on Fuchs and Steller (2011).

Regulation of the apoptosome

The apoptosome is regulated by mitochondrial outer membrane proteins of the BCL2 family. In C. elegans, loss-of-function mutations in the Bcl2-related gene ced-9 activate apoptosis in developing cells that normally live (Hengartner et al., 1992). In these cells, CED-9 protein normally binds CED-4, preventing apoptosome activation (Chinnaiyan et al., 1997; Spector et al., 1997; Wu et al., 1997) (Fig. 1A). Nonetheless, CED-9 may also have pro-apoptotic functions (Hengartner and Horvitz, 1994a; Shaham and Horvitz, 1996), and these could, in part, be a consequence of its effects on mitochondrial morphology (Jagasia et al., 2005). In vertebrates, pro/anti-apoptotic roles are divided among BCL2 family proteins. Some BCL2 family proteins, including BCL2, the first pro-survival protein to be discovered in any species (Vaux et al., 1988), inhibit apoptosis, whereas others, such as Bax, Bak (Bak1) and Bok, promote it (Youle and Strasser, 2008) (Fig. 1C). Binding of BCL2 family members to Apaf1 is likely not an important regulatory mechanism in vertebrates. Instead, these proteins govern the release of mitochondrial Apaf1-binding factors, chief among them, cytochrome C, which activates Apaf1 (Zou et al., 1997) (Fig. 1C). Drosophila BCL2-related proteins appear not to have apoptotic developmental functions, but influence DNA-damage induced apoptosis (Brachmann et al., 2000; Igaki et al., 2000; Monserrate et al., 2012). Although a role for cytochrome C in Drosophila apoptosis is not known, testes-specific cytochrome C activates caspases during spermatogenesis (Arama et al., 2003), suggesting conserved roles. BCL2 family protein activities are controlled through binding of small BCL2 homology domain 3 (BH3)-only proteins (Conradt and Horvitz, 1998; Youle and Strasser, 2008) (Fig. 1B).

Although BCL2-related proteins play more prominent roles in C. elegans development than in Drosophila, the opposite is true for Inhibitor-of-Apoptosis (IAP) proteins. Drosophila DIAP1 and mammalian XIAP are E3 ubiquitin ligases that target caspases for inhibition and/or degradation (Ryoo et al., 2002; Schile et al., 2008; Vaux and Silke, 2005). Drosophila proteins Reaper, Hid and Grim (White et al., 1994), and mammalian mitochondrial proteins Smac (Diablo), ARTS (Septin4) and HtrA2 (Omi; a mitochondrial serine protease) (Larisch et al., 2000; Suzuki et al., 2001; Verhagen et al., 2000) regulate IAPs and cell death induction (Fig. 1B,C).

Alternative mechanisms of caspase activation

In addition to the intrinsic, mitochondrial-release pathway, mammals also activate apoptosis through extrinsic pathways, involving cell-surface receptor engagement by ligands, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF). This promotes formation of death-induced signaling complexes (DISCs), which contain receptors, linking proteins and an initiator caspase, caspase 8. Like apoptosomes, DISCs facilitate self-cross-activation of pro-caspase 8 moieties, which in turn activate effector caspases (Mace and Riedl, 2010; Yu and Shi, 2008) (Fig. 1C).

Targets of the apoptotic machinery

Although apoptotic roles of caspases were discovered three decades ago, we only have limited understanding of how caspases bring about cell death. Whether caspases cleave a few crucial substrates to effect cell demise or whether wholesale protein degradation is required remains unknown. Hundreds of proteins can be cleaved by caspases (Julien and Wells, 2017); however, functional roles for cleavage are only documented in a few cases.

In vertebrates, for example, DNA degradation accompanies apoptosis and is initiated by caspase-activated DNAse (CAD; DFFB) (Halenbeck et al., 1998). CAD associates with an inhibitor, ICAD (DFFA), which is cleaved during apoptosis, releasing CAD and allowing it to generate blunt-end double-strand DNA breaks (Sakahira et al., 1998). CAD-dependent DNA cleavage is not required for apoptosis, but DNA fragmentation/elimination is delayed in CAD mutants (Kawane et al., 2003).

Cleavage substrates also promote dying-cell phagocytosis. In C. elegans and the mouse, caspases cleave Xk family proteins, which regulate plasma-membrane lipid asymmetry (Stanfield and Horvitz, 2000; Suzuki et al., 2013). Xk protein processing leads to phosphatidyl-serine exposure on plasma membrane outer leaflets, attracting phagocytes that engulf the cell. As with CAD, neither C. elegans CED-8 nor mouse Xkr8 Xk proteins are required for apoptosis, but their loss alters elimination kinetics.

Non-apoptotic cell death

Murine Casp3, Casp9 or Apaf1 gene knockouts cause perinatal lethality (Kuida et al., 1998, 1996; Yoshida et al., 1998). These mutants have cranial disruption, suggesting excess neuron survival, and persistence of inter-digital webbing, which initially pointed to key developmental roles for apoptosis. Nonetheless, subsequent studies have questioned these interpretations. For one, cell death during early embryo cavitation proceeds unabated in these mutants (Coucouvanis and Martin, 1995). Furthermore, although perinatal lethality is common, even triple-mutant mice lacking Bax, Bak and Bok, in which no apoptosis occurs, can develop to adulthood (Ke et al., 2018). Furthermore, although inter-digital webbing persists for a while, it is eventually eliminated (Chautan et al., 1999). Thus, other developmental cell death forms must exist. Linker cell-type death (LCD) has emerged as a leading candidate, along with other, less well characterized, pathways.

Linker cell-type death

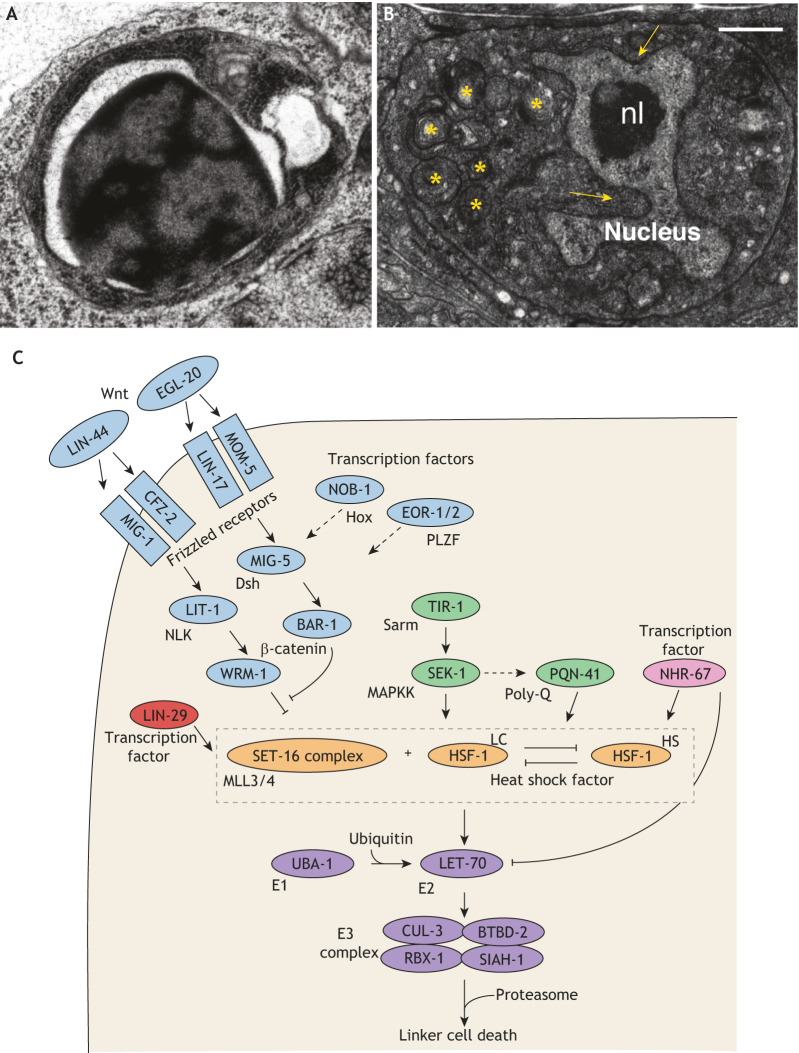

Studies of the C. elegans linker cell provided the first direct evidence that caspase-independent non-apoptotic cell death operates during animal development (Fig. 2). The linker cell, a male-specific leader cell that guides gonad elongation, dies to facilitate vas deferens and cloacal fusion (Kimble and Hirsh, 1979). Mutants in which linker cell death does not occur retain sperm and are likely infertile (Abraham et al., 2007). Importantly, linker cell death still occurs in animals lacking all four C. elegans caspase-related genes (Abraham et al., 2007; Denning et al., 2013). Similarly, other apoptosis genes are not required, nor are genes implicated in autophagy or necrosis. Consistent with these observations, dying linker cell ultra-structure differs from apoptotic morphology (Fig. 2A,B) and is characterized by lack of chromatin condensation, a crenellated nucleus and organelle swelling (Abraham et al., 2007). Thus, LCD represents a novel cell death program.

Fig. 2.

Regulation of linker cell-type death in C. elegans. (A) Electron micrograph of a C. elegans apoptotic cell. (B) Electron micrograph of a C. elegans linker cell dying by LCD. nl, nucleolus. Arrows, nuclear invaginations/crenellations. Asterisks, swollen organelles. (C) Pathway for LCD in C. elegans. LCD in worms is subject to both cell-autonomous transcriptional control and non-autonomous control through multiple control pathways. Death onset is controlled by two opposing Wnt pathways (blue). The Wnt ligand LIN-44 acts non-autonomously in conjunction with the Frizzled receptors MIG-1 and CFZ-2, the Nemo-like kinase LIT-1 and the β-catenin WRM-1 in the linker cell to possibly prevent premature death. A second Wnt pathway inhibits the LIN-44/Wnt pathway. Here, EGL-20/Wnt acts non-autonomously, and LIN-17/Frizzled and MOM-5/Frizzled act in the linker cell with MIG-5/Disheveled and BAR-1/β-catenin, promoting death. This second pathway is likely controlled by two additional transcription factors, NOB-1/Hox and the EOR-1/-2/PLZF complex. In a parallel pathway (green), death is promoted by TIR-1, the C. elegans ortholog of mammalian Sarm, which activates the MAPKK protein SEK-1, which in turn may promote expression of the polyglutamine-repeat protein PQN-41 in the linker cell. The zinc-finger protein LIN-29 (red), which regulates developmental timing, and the nuclear hormone receptor NHR-67 (pink) appear to act independently of and in parallel with the Wnt and MAPKK pathways to promote death. In addition, HSF-1 may transcriptionally activate components of the ubiquitin proteasome system (purple).The pro-death function of HSF-1 (LC) competes with the pro-survival function (HS). Adapted from Kutscher and Shaham (2017). Scale bars: 0.5 μm.

A central LCD regulator in C. elegans is HSF-1, a conserved transcription factor, which adopts death-promoting roles that are distinct from its well-described protective functions in heat-shock response. let-70 (encoding a conserved E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme) is a key HSF-1 target. LET-70 (E2), ubiquitin and proteasome component expression increases preceding LCD. CUL-3 (cullin-3), RBX-1, BTBD-2 and SIAH-1 E3 ligase components function with LET-70 for C. elegans LCD (Kinet et al., 2016) (Fig. 2C).

Ultra-structural similarities to C. elegans LCD abound in developing vertebrates. For example, murine embryonic stem cells lacking caspase 9 undergo normal culling, but with LCD morphology (Hakem et al., 1998). Spinal cord motoneuron death occurs unabated in caspase or Apaf-1 mutants (Kuida et al., 1998, 1996; Yoshida et al., 1998); and although some extra motoneurons accumulate in Bax mutants, these fail to make synapses, have short axons and exhibit crenellated nuclei (Sun et al., 2003). LCD morphology is also observed in normally dying chick ciliary ganglion neurons (Chu-Wang and Oppenheim, 1978; O'Connor and Wyttenbach, 1974). In the reproductive system, dying Müllerian or Wolffian duct cells also exhibit LCD hallmarks (Djehiche et al., 1994; Dyche, 1979; Price et al., 1977). Vertebrate homologs of some C. elegans LCD genes have been implicated in cell degenerative processes (see below). LCD, therefore, appears to be a prevalent non-apoptotic program operating across animals (Kutscher and Shaham, 2017).

Autophagy-associated cell death

Autophagy, bulk degradation of cytoplasm and organelles by the lysosome, accompanies cell death in some developmental contexts (Allen and Baehrecke, 2020). Whether autophagy drives cell death, or is a protective cellular response, remains hotly debated. Nonetheless, the occurrence of autophagy morphologically distinguishes autophagic death from standard apoptosis. Autophagic death has been studied extensively in Drosophila salivary glands, larval structures degraded after pupa formation (Berry and Baehrecke, 2007; Jiang et al., 1997). Although expression of caspase genes is induced in this structure (Lee et al., 2003), mutations in caspase genes, or in Dark, do not block salivary gland elimination (Berry and Baehrecke, 2007; Muro et al., 2006). Instead, cell fragments persist inappropriately. Autophagy genes are also induced early during salivary gland elimination, and in atg18a mutants glands are not fully degraded. Combined autophagy and caspase inhibition blocks degradation further, but not cell death initiation. Cell death is inhibited by overexpression of the PI3K active subunit Dp110 (PI3K92E), suggesting that a PI3K target drives death (Berry and Baehrecke, 2007). Cell death in the Drosophila midgut is also autophagic, with similar characteristics to salivary gland death (Denton et al., 2009).

Cell death by extrusion

Dying epithelial cells lose contact with neighbors and are shed in a process termed anoikis (Frisch and Francis, 1994). Although caspase activation accompanies anoikis, cell elimination by shedding is still observed in caspase mutants. Thus, contact loss may be an independent cell-elimination program. In C. elegans lacking CED-3 caspase, a few cells slated to die are extruded into the embryonic fluid. Shedding requires the PIG-1 AMP-activated serine/threonine kinase (Denning et al., 2012), which also promotes apoptotic death of neuroblast daughter cells (Cordes et al., 2006). PIG-1 may prevent expression of cell adhesion molecules of cells destined to die. A complex containing PAR-4, the homolog of the mammalian tumor-suppressor kinase LKB1 (STK11), may target PIG-1 to facilitate cell extrusion. In Drosophila, wing imaginal disc cells harboring homozygous mutations in the cell-growth gene apterous are removed by apoptosis and basal extrusion. When apoptosis is blocked, extrusion eliminates all dying cells (Klipa and Hamaratoglu, 2019). Shedding also occurs in vertebrate epithelia: in zebrafish, dying cells express the cell-surface lipid sphingosine 1-phosphate, allowing binding to neighboring cells. These initiate intercellular actomyosin ring contraction that ejects cells from the epithelium (Gu et al., 2011). In the mouse intestine, physiological enterocyte shedding involves redistribution of the tight-junction protein ZO-1 (TJP1; Guan et al., 2011).

Cell death with non-canonical lysosome or mitochondria involvement

Perhaps the strongest evidence that lysosomes promote developmental cell death comes from studies of Drosophila germ cells. Here, the initiator caspase Dronc is required, independently of Dark or effector caspases, to promote lysosome membrane permeabilization. Germ-cell death is reduced in lysosome biogenesis mutants and in mutants of the lysosomal protease-encoding gene Cathepsin D (Yacobi-Sharon et al., 2013). Lysosomes also promote the death of nurse cells, which provide developing Drosophila oocytes with mRNA, proteins and organelles (Jenkins et al., 2013). Here, loss of lysosomal DNaseII Deep orange (Vps18; a lysosomal trafficking protein), Spinster (a lysosomal fusion protein) or Cathepsin D results in nurse cell nuclei persistence. Deep orange functions in the engulfing follicle cells, whereas DNaseII and Spinster act cell autonomously (Bass et al., 2009; Peterson and McCall, 2013).

Although release of mitochondrial proteins can lead to caspase activation and apoptosis, mitochondria may also direct alternative cell dismantling. Mitochondrial HtrA2 can promote germ-cell death in Drosophila independently of caspases (Yacobi-Sharon et al., 2013). In mammalian cells, HtrA2 overexpression also promotes caspase-independent cell death, accompanied by morphological changes resembling dying Drosophila germ cells (Suzuki et al., 2001).

Developmental regulation of cell death

Transcription

Cell death is activated in developing tissues in a myriad of ways. Apoptosis in C. elegans is usually induced by transcriptional activation of egl-1/BH3-only (Malin and Shaham, 2015) (Fig. 1A). For example, the sex-determination protein TRA-1A (TRA-1) represses egl-1 transcription in HSNs of hermaphrodites, but not males, driving sexually-dimorphic survival of this cell (Conradt and Horvitz, 1999). The Hox gene lin-39 suppresses egl-1 transcription in VCs, preventing apoptosis (Potts et al., 2009). Transcription of ced-3 caspase also controls apoptosis onset (Malin and Shaham, 2015). In the tail-spike cell, which dies independently of EGL-1, apoptosis initiation follows ced-3 caspase gene transcription by PAL-1, a caudal-type homeodomain protein (Maurer et al., 2007). In Drosophila, the Hox genes Deformed and Abd-B promote apoptosis at intersegmental boundaries by regulating reaper expression (Aachoui et al., 2013; Lohmann et al., 2002; Miguel-Aliaga and Thor, 2004; Suska et al., 2011).

RNA inhibition

Post-transcriptional mechanisms also control apoptosis. In the C. elegans germ-line, for example, ced-3 caspase mRNA is repressed by four conserved RNA-binding proteins (Subasic et al., 2016). Likewise, the Drosophila microRNA bantam is a potent inhibitor of apoptotic cell death during development (Brennecke et al., 2003). C. elegans bantam-related microRNAs mir-35 and mir-58 also inhibit apoptosis by inhibiting egl-1 mRNA accumulation (Sherrard et al., 2017).

Signaling

Cell-cell signaling pathways in Drosophila and vertebrates often initiate apoptosis. In Drosophila, Notch signaling promotes apoptosis of neuronal hemilineages in the post-embryonic ventral nerve cord (Truman et al., 2010). The Hippo signaling pathway also regulates cell death through the transcriptional co-activator Yorkie, which inhibits hid, leading to DIAP1 activation and cell survival (Huang et al., 2005). In the murine skin and nervous system, loss of Ras pathway components promotes apoptosis (Satoh et al., 2011; Scholl et al., 2007), suggesting this developmental pathway normally blocks death.

External signals also regulate LCD (Fig. 2C). In C. elegans, linker cell LCD is controlled by the EGL-30 pro-death and LIN-44 pro-survival Wnt signals that together function redundantly with developmental timing (LIN-29, Zn-finger) and SEK-1/MAPKK pathways. These pathways control non-canonical HSF-1 activity (Kinet et al., 2016). In vertebrates, Müllerian duct degeneration, which appears to proceed by LCD, is initiated by a TGF-β-related anti-Müllerian hormone (Cate et al., 1986) and by Wnts (Allard et al., 2000; Orvis et al., 2008; Roberts et al., 2002).

Engulfment assistance

Signaling from engulfing cells has emerged as an important mechanism for guaranteeing apoptosis fidelity. For example, neighboring engulfing cells non-autonomously assist killing of C. elegans B.al/rapaav cells (Johnsen and Horvitz, 2016), and engulfment gene mutations enhance cell survival in animals homozygous for weak ced-3 caspase mutations (Hoeppner et al., 2001; Reddien et al., 2001). Engulfing cells may promote polarized CED-3 caspase distribution in precursor cells, resulting in death of one daughter cell and survival of the other (Chakraborty et al., 2015). Similar non-autonomous requirements for engulfment genes regulate Drosophila nurse cell death. Loss of the engulfment receptor Draper, homologous to C. elegans CED-1 and vertebrate MEGF10, from surrounding follicle cells blocks nurse cell genome fragmentation and death (Timmons et al., 2017).

Cell compartment elimination

Subcellular compartments are often selectively eliminated during development, a process that has been termed ‘pruning’. In the nervous system, axon or dendrite fragmentation removes exuberant connections to refine and sculpt activity (Box 1; Fig. 3A). Such remodeling occurs in Drosophila mushroom body gamma neurons (Technau and Heisenberg, 1982; Watts et al., 2003) and dendritic arborization (da) neurons (Williams and Truman, 2005), as well as in murine L5 cortical neurons (Bagri et al., 2003). Neuronal pruning can also be achieved by process retraction, or ‘dying back’, without fragmentation (Fig. 3B), as in mammalian hippocampal infrapyramidal neurons. Receptors for axon guidance, TGF-β and so-called death receptors initiate pruning (Bagri et al., 2003; Low et al., 2008; Nikolaev et al., 2009; Yan et al., 2005; Yu and Schuldiner, 2014; Zheng et al., 2003). Downstream players include ubiquitin proteasome system components, calcium-activated calpains, kinases and cytoskeletal regulators (Chen et al., 2012; Ghosh et al., 2011; Watts et al., 2003; Williams and Truman, 2005; Zhai et al., 2003).

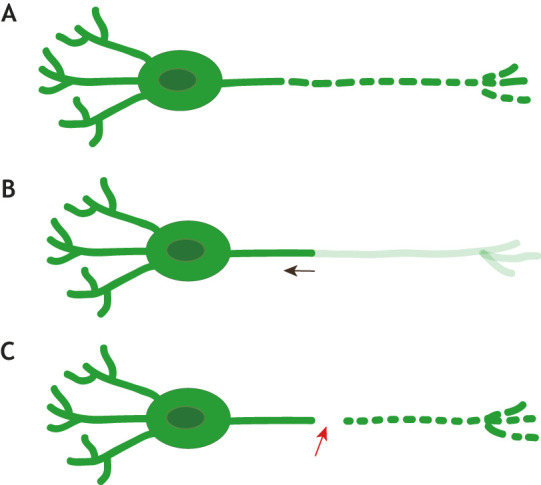

Fig. 3.

Neurite-specific elimination. (A) Cell process fragmentation. (B) Cell process retraction, or ‘dying back’. (C) Wallerian degeneration: following axon severing (red arrow) the cell body remains intact while the axon fragments.

Caspases are important for developmental pruning. In Drosophila, Dronc, Drice and DCP-1 are essential for da neuron dendrite culling (Kuo et al., 2006; Schoenmann et al., 2010; Williams et al., 2006). In mammals, caspase 3 and caspase 6 promote developmental pruning of retinocollicular axons (Simon et al., 2012). Caspase-dependent axon degeneration can also occur following NGF deprivation. Here, a retrograde signal from the axon induces a transcriptional response that feeds back into the axon to effect its destruction. Thus, pruning can be a cell-wide phenomenon, and requires communication between cell compartments (Simon et al., 2016).

Caspase-dependent cell compartment-specific elimination is also found during Drosophila spermatogenesis. Here, before individualization, 64 spermatids remain interconnected by cytoplasmic bridges. An actin-based complex traverses the length of the spermatid axonemes away from the nuclei, resolves the cytoplasmic bridges and extrudes the cytoplasm between the spermatid tails, leaving behind individualized spermatids. Caspase mutants retain cytoplasm-filled cystic bulges (Tokuyasu et al., 1972; Fabrizio et al., 1998; Arama et al., 2003).

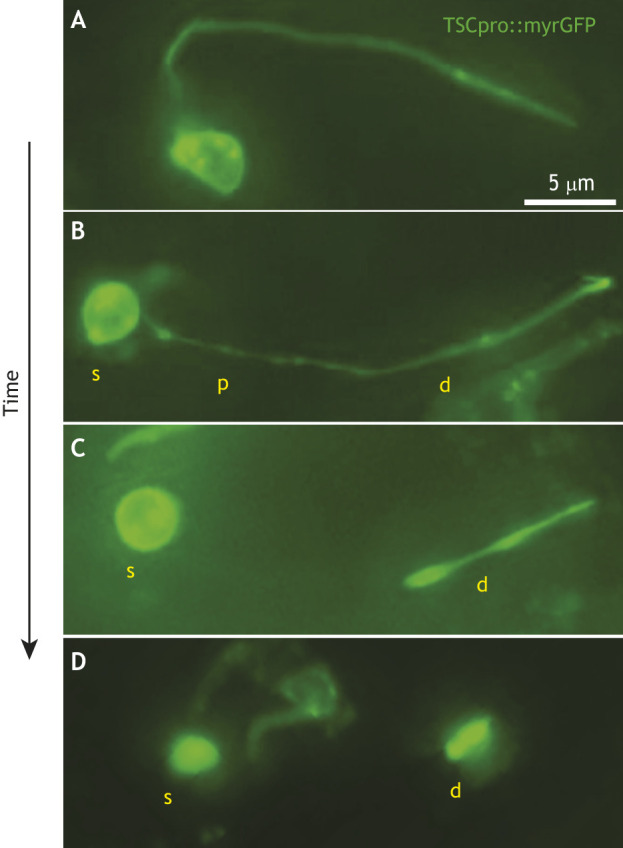

Even when an entire morphologically complex cell is eliminated in development, different parts of the cell can die by different mechanisms, as with the C. elegans tail-spike cell, a morphologically complex cell with a long microtubule-rich process that shapes and extends to the tip of the tail. The tail-spike cell dies after guiding tail formation in the late-stage embryo through a non-canonical apoptotic pathway that depends on CED-3 caspase and CED-4/Apaf1, but not EGL-1/BH3-only (Maurer et al., 2007). Initiation of cell death depends on transcriptional activation of ced-3 by PAL-1, a homolog of mammalian Cdx homeodomain protein. The tail-spike cell is relatively long-lived, dying after differentiation, lending itself to a more detailed examination than most cells fated to die in the nematode. The tail-spike cell dies through three compartment-specific programs, in which the proximal process fragments and clears first, the cell body then rounds, and the distal process retracts (Ghose et al., 2018) (Fig. 4). This multi-faceted degeneration program, which we have termed compartmentalized cell elimination (CCE), also promotes removal of C. elegans CEM neurons, which die sex-specifically in the hermaphrodite embryo (Ghose et al., 2018). This suggests existence of a conserved mode of complex cell elimination. Nonetheless, our understanding of pruning mechanisms is rudimentary, and elucidation of compartment-specific dismantling mechanisms remains an important goal for the field.

Fig. 4.

Compartmentalized cell elimination. (A-D) Images of a dying C. elegans tail-spike cell at different stages of death. (A) An intact tail-spike cell with a soma and long process. The proximal process segment (p) undergoes localized beading and fragmentation (B) and is eliminated before the soma (s) and distal process (d) (C). The soma rounds (B,C). The distal segment undergoes bidirectional retraction into a compact structure (C,D) and is eventually engulfed and removed. The entire cell is eliminated in ∼150 min. The caspase CED-3 acts independently in each compartment. Adapted from Ghose et al. (2018). TSCpro, tail-spike cell promoter; myrGFP, myristoylated green fluorescent protein (GFP).

Cell death and disease

The 2002 Nobel Prize was awarded, in part, for discovering genes controlling cell death in animal development. These studies, initiated when C. elegans was still an obscure model system, provided a blueprint for identifying cell death pathways in other animals, revealing broad conservation of the apoptotic program. Apoptosis research quickly gained traction once roles in human disease became apparent, with the discovery of mutations in regulators such as BCL2 and the death receptor Fas in lymphoproliferative disease and in cancer. Nonetheless, rather than the end of the story, the Nobel recognition coincided with the realization that much more needs to be investigated before cell death is declared understood. The identification of non-apoptotic programs in development reflects this current momentum, and association of these programs with human diseases (Box 3) once again drives wide interest.

Box 3. Linking developmental cell death to human disease.

A number of developmental cell death genes have been associated with disease states. Homologs of several C. elegans LCD pathway components, for example, promote cell-degenerative processes or tumorigenesis in vertebrates. C. elegans pqn-41, which encodes a self-aggregating glutamine-rich protein, is reminiscent of polyQ proteins that cause neurodegeneration (Blum et al., 2012), and polyQ-associated death is characterized by nuclear crenellations like those seen in LCD (Davies et al., 1997). tir1/Sarm, which functions with PQN-41/Q-rich, promotes distal axon degeneration following axotomy in mice and Drosophila (Osterloh et al., 2012). The LCD regulators let-7/microRNA and HSF-1 are often altered in tumors (Jiang et al., 2015; Nguyen and Zhu, 2015). Homologs of the transcriptional regulators SET-16/MLL, NHR-67/TLX, and EOR-1/PLZF, which also regulate C. elegans LCD, are altered in – and causal for – some tumors (Chen et al., 1994; Jackson et al., 1998; Ruault et al., 2002). HTRA2 lesions in humans are associated with Parkinson's disease, and Pink1, a Parkinson's disease and mitochondria-associated protein, promotes Drosophila germ-cell death (Strauss et al., 2005).

Studies of cell compartment elimination in development may also shed light on related human pathologies. Perhaps the most well-studied example of pathological neurite degeneration is Wallerian degeneration (Fig. 3C; Coleman and Freeman, 2010). Here, distal axons, severed from the cell body, fragment. In Wallerian degeneration slow (Wlds) mice, expressing an abnormal protein fusion between a NAD+ synthesis protein, NMNAT, and the ubiquitin factor E4B (Ube4b), axons persist after severing, indicating that axon degeneration is not passive (Mack et al., 2001). That the gene Sarm is required for Wallerian degeneration in mammals and Drosophila (Hoopfer et al., 2006; Osterloh et al., 2012; Xiong et al., 2012), and for developmental LCD in C. elegans (Blum et al., 2012), suggests that developmental cell death components may underlie pathological cell or process elimination.

Future perspectives

Many questions about the basic mechanisms of cell death in development remain. Perhaps most important is an understanding of what it means for a cell to die. Are specific cellular pathways targeted, disruption of which is the point of no return? Do all cell death pathways converge on these same targets? Is the end of metabolism the end of life for a cell, or is cell death only truly effected through phagocytic degradation? Touching on the realm of philosophy, it is possible that delving deeper into cell death mechanisms will reveal meaningful responses to these metaphysical inquiries.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jennifer Malin for comments on the manuscript. We apologize to those colleagues whose work we could not cite owing to space constraints.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Funding

P.G. is a Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) Scholar in Cancer Research (RR190091). S.S. is supported by National Institutes of Health grant R35NS105094. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

References

- Aachoui Y., Sagulenko V., Miao E. A. and Stacey K. J. (2013). Inflammasome-mediated pyroptotic and apoptotic cell death, and defense against infection. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 16, 319-326. 10.1016/j.mib.2013.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham M. C., Lu Y. and Shaham S. (2007). A morphologically conserved nonapoptotic program promotes linker cell death in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Cell 12, 73-86. 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrams J. M., White K., Fessler L. I. and Steller H (1993). Programmed cell death during Drosophila embryogenesis. Development 117, 29-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acehan D., Jiang X., Morgan D. G., Heuser J. E., Wang X. and Akey C. W. (2002). Three-dimensional structure of the apoptosome: implications for assembly, procaspase-9 binding, and activation. Mol. Cell 9, 423-432. 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00442-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allard S., Adin P., Gouedard L., di Clemente N., Josso N., Orgebin-Crist M. C., Picard J. Y. and Xavier F (2000). Molecular mechanisms of hormone-mediated Mullerian duct regression: involvement of beta-catenin. Development 127, 3349-3360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen E. A. and Baehrecke E. H. (2020). Autophagy in animal development. Cell Death Differ. 27, 903-918. 10.1038/s41418-020-0497-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arama E., Agapite J. and Steller H. (2003). Caspase activity and a specific cytochrome C are required for sperm differentiation in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 4, 687-697. 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00120-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arandjelovic S. and Ravichandran K. S. (2015). Phagocytosis of apoptotic cells in homeostasis. Nat. Immunol. 16, 907-917. 10.1038/ni.3253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery L. and Horvitz H. R. (1987). A cell that dies during wild-type C. elegans development can function as a neuron in a ced-3 mutant. Cell 51, 1071-1078. 0092-8674(87)90593-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baehrecke E. H. (2002). How death shapes life during development. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 779-787. 10.1038/nrm931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagri A., Cheng H.-J., Yaron A., Pleasure S. J. and Tessier-Lavigne M. (2003). Stereotyped pruning of long hippocampal axon branches triggered by retraction inducers of the semaphorin family. Cell 113, 285-299. 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00267-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass B. P., Tanner E. A., Mateos San Martin D., Blute T., Kinser R. D., Dolph P. J. and McCall K. (2009). Cell-autonomous requirement for DNaseII in nonapoptotic cell death. Cell Death Differ. 16, 1362-1371. 10.1038/cdd.2009.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedzhov I. and Zernicka-Goetz M. (2015). Cell death and morphogenesis during early mouse development: are they interconnected? BioEssays 37, 372-378. 10.1002/bies.201400147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry D. L. and Baehrecke E. H. (2007). Growth arrest and autophagy are required for salivary gland cell degradation in Drosophila. Cell 131, 1137-1148. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum E. S., Abraham M. C., Yoshimura S., Lu Y. and Shaham S. (2012). Control of nonapoptotic developmental cell death in Caenorhabditis elegans by a polyglutamine-repeat protein. Science 335, 970-973. 10.1126/science.1215156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachmann C. B., Jassim O. W., Wachsmuth B. D. and Cagan R. L. (2000). The Drosophila bcl-2 family member dBorg-1 functions in the apoptotic response to UV-irradiation. Curr. Biol. 10, 547-550. 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00474-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennecke J., Hipfner D. R., Stark A., Russell R. B. and Cohen S. M. (2003). bantam encodes a developmentally regulated microRNA that controls cell proliferation and regulates the proapoptotic gene hid in Drosophila. Cell 113, 25-36. 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00231-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cate R. L., Mattaliano R. J., Hession C., Tizard R., Farber N. M., Cheung A., Ninfa E. G., Frey A. Z., Gash D. J., Chow E. P. et al. (1986). Isolation of the bovine and human genes for Müllerian inhibiting substance and expression of the human gene in animal cells. Cell 45, 685-698. 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90783-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty S., Lambie E. J., Bindu S., Mikeladze-Dvali T. and Conradt B. (2015). Engulfment pathways promote programmed cell death by enhancing the unequal segregation of apoptotic potential. Nat. Commun. 6, 10126 10.1038/ncomms10126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chautan M., Chazal G., Cecconi F., Gruss P. and Golstein P. (1999). Interdigital cell death can occur through a necrotic and caspase-independent pathway. Curr. Biol. 9, 967-970. 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80425-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Guidez F., Rousselot P., Agadir A., Chen S. J., Wang Z. Y., Degos L., Zelent A., Waxman S. and Chomienne C. (1994). PLZF-RAR alpha fusion proteins generated from the variant t(11;17)(q23;q21) translocation in acute promyelocytic leukemia inhibit ligand-dependent transactivation of wild-type retinoic acid receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 1178-1182. 10.1073/pnas.91.3.1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Maloney J. A., Kallop D. Y., Atwal J. K., Tam S. J., Baer K., Kissel H., Kaminker J. S., Lewcock J. W., Weimer R. M. et al. (2012). Spatially coordinated kinase signaling regulates local axon degeneration. J. Neurosci. 32, 13439-13453. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2039-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnaiyan A. M., O'Rourke K., Lane B. R. and Dixit V. M. (1997). Interaction of CED-4 with CED-3 and CED-9: a molecular framework for cell death. Science 275, 1122-1126 10.1126/science.275.5303.1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu-Wang I.-W. and Oppenheim R. W. (1978). Cell death of motoneurons in the chick embryo spinal cord. I. A light and electron microscopic study of naturally occurring and induced cell loss during development. J. Comp. Neurol. 177, 33-57. 10.1002/cne.901770105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke P. G. H. (1990). Developmental cell death: morphological diversity and multiple mechanisms. Anat. Embryol. 181, 195-213. 10.1007/bf00174615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman M. P. and Freeman M. R. (2010). Wallerian degeneration, wld(s), and nmnat. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 33, 245-267. 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conradt B. and Horvitz H. R. (1998). The C. elegans protein EGL-1 is required for programmed cell death and interacts with the Bcl-2-like protein CED-9. Cell 93, 519-529. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81182-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conradt B. and Horvitz H. R. (1999). The TRA-1A sex determination protein of C. elegans regulates sexually dimorphic cell deaths by repressing the egl-1 cell death activator gene. Cell 98, 317-327. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81961-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper D. M., Granville D. J. and Lowenberger C. (2009). The insect caspases. Apoptosis 14, 247-256. 10.1007/s10495-009-0322-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordes S., Frank C. A. and Garriga G. (2006). The C. elegans MELK ortholog PIG-1 regulates cell size asymmetry and daughter cell fate in asymmetric neuroblast divisions. Development 133, 2747-2756. 10.1242/dev.02447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornillon S., Foa C., Davoust J., Buonavista N., Gross J. D. and Golstein P (1994). Programmed cell death in Dictyostelium. J. Cell Sci. 107, 2691-2704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coucouvanis E. and Martin G. R. (1995). Signals for death and survival: a two-step mechanism for cavitation in the vertebrate embryo. Cell 83, 279-287. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90169-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David K. K., Andrabi S. A., Dawson T. M. and Dawson V. L. (2009). Parthanatos, a messenger of death. Front. Biosci. 14, 1116-1128. 10.2741/3297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies S. W., Turmaine M., Cozens B. A., DiFiglia M., Sharp A. H., Ross C. A., Scherzinger E., Wanker E. E., Mangiarini L. and Bates G. P. (1997). Formation of neuronal intranuclear inclusions underlies the neurological dysfunction in mice transgenic for the HD mutation. Cell 90, 537-548. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80513-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denning D. P., Hatch V. and Horvitz H. R. (2012). Programmed elimination of cells by caspase-independent cell extrusion in C. elegans. Nature 488, 226-230. 10.1038/nature11240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denning D. P., Hatch V. and Horvitz H. R. (2013). Both the caspase CSP-1 and a caspase-independent pathway promote programmed cell death in parallel to the canonical pathway for apoptosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003341 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton D., Shravage B., Simin R., Mills K., Berry D. L., Baehrecke E. H. and Kumar S. (2009). Autophagy, not apoptosis, is essential for midgut cell death in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 19, 1741-1746. 10.1016/j.cub.2009.08.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon S. J. (2017). Ferroptosis: bug or feature? Immunol. Rev. 277, 150-157. 10.1111/imr.12533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djehiche B., Segalen J. and Chambon Y. (1994). Ultrastructure of mullerian and wolffian ducts of fetal rabbit in vivo and in organ culture. Tissue Cell 26, 323-332. 10.1016/0040-8166(94)90018-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyche W. J. (1979). A comparative study of the differentiation and involution of the Mullerian duct and Wolffian duct in the male and female fetal mouse. J. Morphol. 162, 175-209. 10.1002/jmor.1051620203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis H. M. and Horvitz H. R. (1986). Genetic control of programmed cell death in the nematode C. elegans. Cell 44, 817-829. 0092-8674(86)90004-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis R. E., Yuan J. Y. and Horvitz H. R. (1991). Mechanisms and functions of cell death. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 7, 663-698. 10.1146/annurev.cb.07.110191.003311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrizio J. J., Hime G., Lemmon S. K. and Bazinet C. (1998). Genetic dissection of sperm individualization in Drosophila melanogaster. Development 125, 1833-1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatokun A. A., Dawson V. L. and Dawson T. M. (2014). Parthanatos: mitochondrial-linked mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Br. J. Pharmacol. 171, 2000-2016. 10.1111/bph.12416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch S. M. and Francis H. (1994). Disruption of epithelial cell-matrix interactions induces apoptosis. J. Cell Biol. 124, 619-626. 10.1083/jcb.124.4.619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs Y. and Steller H. (2011). Programmed cell death in animal development and disease. Cell 147, 742-758. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galluzzi L. and Kroemer G. (2008). Necroptosis: a specialized pathway of programmed necrosis. Cell 135, 1161-1163. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galluzzi L., Kepp O., Krautwald S., Kroemer G. and Linkermann A. (2014). Molecular mechanisms of regulated necrosis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 35, 24-32. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng X., Zhou Q. H., Kage-Nakadai E., Shi Y., Yan N., Mitani S. and Xue D. (2009). Caenorhabditis elegans caspase homolog CSP-2 inhibits CED-3 autoactivation and apoptosis in germ cells. Cell Death Differ. 16, 1385-1394. 10.1038/cdd.2009.88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghose P., Rashid A., Insley P., Trivedi M., Shah P., Singhal A., Lu Y., Bao Z. and Shaham S. (2018). EFF-1 fusogen promotes phagosome sealing during cell process clearance in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Cell Biol. 20, 393-399. 10.1038/s41556-018-0068-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A. S., Wang B., Pozniak C. D., Chen M., Watts R. J. and Lewcock J. W. (2011). DLK induces developmental neuronal degeneration via selective regulation of proapoptotic JNK activity. J. Cell Biol. 194, 751-764. 10.1083/jcb.201103153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glücksmann A. (1951). Cell deaths in normal vertebrate ontogeny. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 26, 59-86. 10.1111/j.1469-185x.1951.tb00774.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glücksmann A. (1965). Cell death in normal development. Arch. Biol. 76, 419-437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick-Ashkenazi A., Weiss R., Sapozhnikov L., Florentin A., Tarayrah-Ibraheim L., Dweik D., Yacobi-Sharon K. and Arama E. (2018). Caspases maintain tissue integrity by an apoptosis-independent inhibition of cell migration and invasion. Nat. Commun. 9, 2806 10.1038/s41467-018-05204-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg J. T. (1996). Programmed cell death: a way of life for plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 12094-12097. 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y., Forostyan T., Sabbadini R. and Rosenblatt J. (2011). Epithelial cell extrusion requires the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2 pathway. J. Cell Biol. 193, 667-676. 10.1083/jcb.201010075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y., Watson A. J. M., Marchiando A. M., Bradford E., Shen L., Turner J. R. and Montrose M. H. (2011). Redistribution of the tight junction protein ZO-1 during physiological shedding of mouse intestinal epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 300, C1404-C1414. 10.1152/ajpcell.00270.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakem R., Hakem A., Duncan G. S., Henderson J. T., Woo M., Soengas M. S., Elia A., de la Pompa J. L., Kagi D., Khoo W. et al. (1998). Differential requirement for caspase 9 in apoptotic pathways in vivo. Cell 94, 339-352. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81477-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halenbeck R., MacDonald H., Roulston A., Chen T. T., Conroy L. and Williams L. T. (1998). CPAN, a human nuclease regulated by the caspase-sensitive inhibitor DFF45. Curr. Biol. 8, 537-540. 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)79298-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger V. and Levi-Montalcini R (1949). Proliferation, differentiation and degeneration in the spinal ganglia of the chick embryo under normal and experimental conditions. J. Exp. Zool. 111, 457-501 10.1002/jez.1401110308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins C. J., Yoo S. J., Peterson E. P., Wang S. L., Vernooy S. Y. and Hay B. A. (2000). The Drosophila caspase DRONC is a glutamate/aspartate protease whose activity is regulated by DIAP1, HID and GRIM. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 27084-27093. 10.1074/jbc.M000869200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengartner M. O., Ellis R. E. and Horvitz H. R. (1992). Caenorhabditis elegans gene ced-9 protects cells from programmed cell death. Nature 356, 494-499 10.1038/356494a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengartner M. O. and Horvitz H. R. (1994a). Activation of C. elegans cell death protein CED-9 by an amino-acid substitution in a domain conserved in Bcl-2. Nature 369, 318-320. 10.1038/369318a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengartner M. O. and Horvitz H. R. (1994b). C. elegans cell survival gene ced-9 encodes a functional homolog of the mammalian proto-oncogene bcl-2. Cell 76, 665-676. 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90506-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeppner D. J., Hengartner M. O. and Schnabel R. (2001). Engulfment genes cooperate with ced-3 to promote cell death in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 412, 202-206. 10.1038/35084103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoopfer E. D., McLaughlin T., Watts R. J., Schuldiner O., O'Leary D. D. M. and Luo L. (2006). Wlds protection distinguishes axon degeneration following injury from naturally occurring developmental pruning. Neuron 50, 883-895. 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvitz H. R. (2003). Nobel lecture. Worms, life and death. Biosci. Rep. 23, 239-303. 10.1023/B:BIRE.0000019187.19019.e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoste E., Denecker G., Gilbert B., Van Nieuwerburgh F., van der Fits L., Asselbergh B., De Rycke R., Hachem J.-P., Deforce D., Prens E. P. et al. (2013). Caspase-14-deficient mice are more prone to the development of parakeratosis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 133, 742-750. 10.1038/jid.2012.350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Wu S., Barrera J., Matthews K. and Pan D. (2005). The Hippo signaling pathway coordinately regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis by inactivating Yorkie, the Drosophila Homolog of YAP. Cell 122, 421-434. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igaki T., Kanuka H., Inohara N., Sawamoto K., Nunez G., Okano H. and Miura M. (2000). Drob-1, a Drosophila member of the Bcl-2/CED-9 family that promotes cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 662-667. 10.1073/pnas.97.2.662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue S., Browne G., Melino G. and Cohen G. M. (2009). Ordering of caspases in cells undergoing apoptosis by the intrinsic pathway. Cell Death Differ. 16, 1053-1061. 10.1038/cdd.2009.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izzo V., Bravo-San Pedro J. M., Sica V., Kroemer G. and Galluzzi L. (2016). Mitochondrial permeability transition: new findings and persisting uncertainties. Trends Cell Biol. 26, 655-667. 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A., Panayiotidis P. and Foroni L. (1998). The human homologue of the Drosophila tailless gene (TLX): characterization and mapping to a region of common deletion in human lymphoid leukemia on chromosome 6q21. Genomics 50, 34-43. 10.1006/geno.1998.5270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson M. D., Weil M. and Raff M. C. (1997). Programmed cell death in animal development. Cell 88, 347-354. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81873-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagasia R., Grote P., Westermann B. and Conradt B. (2005). DRP-1-mediated mitochondrial fragmentation during EGL-1-induced cell death in C. elegans. Nature 433, 754-760. 10.1038/nature03316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins V. K., Timmons A. K. and McCall K. (2013). Diversity of cell death pathways: insight from the fly ovary. Trends Cell Biol. 23, 567-574. 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C., Baehrecke E. H. and Thummel C. S. (1997). Steroid regulated programmed cell death during Drosophila metamorphosis. Development 124, 4673-4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S., Tu K., Fu Q., Schmitt D. C., Zhou L., Lu N. and Zhao Y. (2015). Multifaceted roles of HSF1 in cancer. Tumour Biol. 36, 4923-4931. 10.1007/s13277-015-3674-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen H. L. and Horvitz H. R. (2016). Both the apoptotic suicide pathway and phagocytosis are required for a programmed cell death in Caenorhabditis elegans. BMC Biol. 14, 39 10.1186/s12915-016-0262-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen I. and Miao E. A. (2015). Pyroptotic cell death defends against intracellular pathogens. Immunol. Rev. 265, 130-142. 10.1111/imr.12287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julien O. and Wells J. A. (2017). Caspases and their substrates. Cell Death Differ. 24, 1380-1389. 10.1038/cdd.2017.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawane K., Fukuyama H., Yoshida H., Nagase H., Ohsawa Y., Uchiyama Y., Okada K., Iida T. and Nagata S. (2003). Impaired thymic development in mouse embryos deficient in apoptotic DNA degradation. Nat. Immunol. 4, 138-144. 10.1038/ni881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke F. F. S., Vanyai H. K., Cowan A. D., Delbridge A. R. D., Whitehead L., Grabow S., Czabotar P. E., Voss A. K. and Strasser A. (2018). Embryogenesis and adult life in the absence of intrinsic apoptosis effectors BAX, BAK, and BOK. Cell 173, 1217-1230.e1217. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.04.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keil W., Kutscher L. M., Shaham S. and Siggia E. D. (2017). Long-term high-resolution imaging of developing C. elegans larvae with microfluidics. Dev. Cell 40, 202-214. 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.11.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr J. F. R., Wyllie A. H. and Currie A. R. (1972). Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in tissue kinetics. Br. J. Cancer 26, 239-257 10.1038/bjc.1972.33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr J. F., Harmon B. and Searle J (1974). An electron-microscope study of cell deletion in the anuran tadpole tail during spontaneous metamorphosis with special reference to apoptosis of striated muscle fibers. J. Cell Sci. 14, 571-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimble J. and Hirsh D. (1979). The postembryonic cell lineages of the hermaphrodite and male gonads in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 70, 396-417. 0012-1606(79)90035-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinet M. J., Malin J. A., Abraham M. C., Blum E. S., Silverman M. R., Lu Y. and Shaham S. (2016). HSF-1 activates the ubiquitin proteasome system to promote non-apoptotic developmental cell death in C. elegans. eLife 5, e12821 10.7554/eLife.12821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klipa O. and Hamaratoglu F. (2019). Cell elimination strategies upon identity switch via modulation of apterous in Drosophila wing disc. PLoS Genet. 15, e1008573 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna S. and Overholtzer M. (2016). Mechanisms and consequences of entosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 73, 2379-2386. 10.1007/s00018-016-2207-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuida K., Zheng T. S., Na S., Kuan C.-Y., Yang D., Karasuyama H., Rakic P. and Flavell R. A. (1996). Decreased apoptosis in the brain and premature lethality in CPP32-deficient mice. Nature 384, 368-372. 10.1038/384368a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuida K., Haydar T. F., Kuan C.-Y., Gu Y., Taya C., Karasuyama H., Su M. S.-S., Rakic P. and Flavell R. A. (1998). Reduced apoptosis and cytochrome c-mediated caspase activation in mice lacking caspase 9. Cell 94, 325-337. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81476-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo C. T., Zhu S., Younger S., Jan L. Y. and Jan Y. N. (2006). Identification of E2/E3 ubiquitinating enzymes and caspase activity regulating Drosophila sensory neuron dendrite pruning. Neuron 51, 283-290. 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutscher L. M. and Shaham S. (2017). Non-apoptotic cell death in animal development. Cell Death Differ. 24, 1326-1336. 10.1038/cdd.2017.20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutscher L. M., Keil W. and Shaham S. (2018). RAB-35 and ARF-6 GTPases mediate engulfment and clearance following linker cell-type death. Dev. Cell 47, 222-238.e226. 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbé K. and Saleh M. (2008). Cell death in the host response to infection. Cell Death Differ. 15, 1339-1349. 10.1038/cdd.2008.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larisch S., Yi Y., Lotan R., Kerner H., Eimerl S., Tony Parks W., Gottfried Y., Birkey Reffey S., de Caestecker M. P., Danielpour D. et al. (2000). A novel mitochondrial septin-like protein, ARTS, mediates apoptosis dependent on its P-loop motif. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 915-921. 10.1038/35046566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.-Y., Clough E. A., Yellon P., Teslovich T. M., Stephan D. A. and Baehrecke E. H. (2003). Genome-wide analyses of steroid- and radiation-triggered programmed cell death in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 13, 350-357. 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00085-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y., Hamann J. C., Pellegrino M., Durgan J., Domart M.-C., Collinson L. M., Haynes C. M., Florey O. and Overholtzer M. (2019). Entosis controls a developmental cell clearance in C. elegans. Cell Rep. 26, 3212-3220.e3214. 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.02.073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsten T., Ross A. J., King A., Zong W. X., Rathmell J. C., Shiels H. A., Ulrich E., Waymire K. G., Mahar P., Frauwirth K. et al. (2000). The combined functions of proapoptotic Bcl-2 family members bak and bax are essential for normal development of multiple tissues. Mol. Cell 6, 1389-1399. S1097-2765(00)00136-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linkermann A. and Green D. R. (2014). Necroptosis. N Engl. J. Med. 370, 455-465. 10.1056/NEJMra1310050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockshin R. A. and Williams C. M. (1965). Programmed cell death--I. Cytology of degeneration in the intersegmental muscles of the Pernyi Silkmoth. J. Insect Physiol. 11, 123-133. 10.1016/0022-1910(65)90099-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann I., McGinnis N., Bodmer M. and McGinnis W (2002). The Drosophila Hox gene deformed sculpts head morphology via direct regulation of the apoptosis activator reaper. Cell 110, 457-466 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00871-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomis W. F. and Smith D. W. (1995). Consensus phylogeny of Dictyostelium. Experientia 51, 1110-1115. 10.1007/bf01944728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low L. K., Liu X.-B., Faulkner R. L., Coble J. and Cheng H.-J. (2008). Plexin signaling selectively regulates the stereotyped pruning of corticospinal axons from visual cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 8136-8141. 10.1073/pnas.0803849105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace P. D. and Riedl S. J. (2010). Molecular cell death platforms and assemblies. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 22, 828-836. 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack T. G. A., Reiner M., Beirowski B., Mi W., Emanuelli M., Wagner D., Thomson D., Gillingwater T., Court F., Conforti L. et al. (2001). Wallerian degeneration of injured axons and synapses is delayed by a Ube4b/Nmnat chimeric gene. Nat. Neurosci. 4, 1199-1206 10.1038/nn770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malin J. Z. and Shaham S. (2015). Cell death in C. elegans development. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 114, 1-42. 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2015.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malin J. A., Kinet M. J., Abraham M. C., Blum E. S. and Shaham S. (2016). Transcriptional control of non-apoptotic developmental cell death in C. elegans. Cell Death Differ. 23, 1985-1994. 10.1038/cdd.2016.77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer C. W., Chiorazzi M. and Shaham S. (2007). Timing of the onset of a developmental cell death is controlled by transcriptional induction of the C. elegans ced-3 caspase-encoding gene. Development 134, 1357-1368. 10.1242/dev.02818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel-Aliaga I. and Thor S. (2004). Segment-specific prevention of pioneer neuron apoptosis by cell-autonomous, postmitotic Hox gene activity. Development 131, 6093-6105. 10.1242/dev.01521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monserrate J. P., Chen M. Y.-Y. and Brachmann C. B. (2012). Drosophila larvae lacking the bcl-2 gene, buffy, are sensitive to nutrient stress, maintain increased basal target of rapamycin (Tor) signaling and exhibit characteristics of altered basal energy metabolism. BMC Biol. 10, 63 10.1186/1741-7007-10-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muro I., Berry D. L., Huh J. R., Chen C. H., Huang H., Yoo S. J., Guo M., Baehrecke E. H. and Hay B. A. (2006). The Drosophila caspase Ice is important for many apoptotic cell deaths and for spermatid individualization, a nonapoptotic process. Development 133, 3305-3315. 10.1242/dev.02495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy J. M., Czabotar P. E., Hildebrand J. M., Lucet I. S., Zhang J.-G., Alvarez-Diaz S., Lewis R., Lalaoui N., Metcalf D., Webb A. I. et al. (2013). The pseudokinase MLKL mediates necroptosis via a molecular switch mechanism. Immunity 39, 443-453. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen L. H. and Zhu H. (2015). Lin28 and let-7 in cell metabolism and cancer. Transl. Pediatr. 4, 4-11. 10.3978/j.issn.2224-4336.2015.01.05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaev A., McLaughlin T., O'Leary D. D. M. and Tessier-Lavigne M. (2009). APP binds DR6 to trigger axon pruning and neuron death via distinct caspases. Nature 457, 981-989. 10.1038/nature07767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- O'Connor T. M. and Wyttenbach C. R. (1974). Cell death in the embryonic chick spinal cord. J. Cell Biol. 60, 448-459. 10.1083/jcb.60.2.448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opferman J. T. and Korsmeyer S. J. (2003). Apoptosis in the development and maintenance of the immune system. Nat. Immunol. 4, 410-415. 10.1038/ni0503-410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim R. W. (1991). Cell death during development of the nervous system. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 453-501. 10.1146/annurev.ne.14.030191.002321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orvis G. D., Jamin S. P., Kwan K. M., Mishina Y., Kaartinen V. M., Huang S., Roberts A. B., Umans L., Huylebroeck D., Zwijsen A. et al. (2008). Functional redundancy of TGF-beta family type I receptors and receptor-Smads in mediating anti-Müllerian hormone-induced Müllerian duct regression in the mouse. Biol. Reprod. 78, 994-1001. 10.1095/biolreprod.107.066605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterloh J. M., Yang J., Rooney T. M., Fox A. N., Adalbert R., Powell E. H., Sheehan A. E., Avery M. A., Hackett R., Logan M. A. et al. (2012). dSarm/Sarm1 is required for activation of an injury-induced axon death pathway. Science 337, 481-484. 10.1126/science.1223899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overholtzer M., Mailleux A. A., Mouneimne G., Normand G., Schnitt S. J., King R. W., Cibas E. S. and Brugge J. S. (2007). A nonapoptotic cell death process, entosis, that occurs by cell-in-cell invasion. Cell 131, 966-979. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson J. S. and McCall K. (2013). Combined inhibition of autophagy and caspases fails to prevent developmental nurse cell death in the Drosophila melanogaster ovary. PLoS ONE 8, e76046 10.1371/journal.pone.0076046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pop C. and Salvesen G. S. (2009). Human caspases: activation, specificity, and regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 21777-21781. 10.1074/jbc.R800084200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts M. B., Wang D. P. and Cameron S. (2009). Trithorax, Hox, and TALE-class homeodomain proteins ensure cell survival through repression of the BH3-only gene egl-1. Dev. Biol. 329, 374-385. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price J. M., Donahoe P. K., Ito Y. and Hendren W. H. III (1977). Programmed cell death in the Müllerian duct induced by Müllerian inhibiting substance. Am. J. Anat. 149, 353-375. 10.1002/aja.1001490304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi S., Pang Y., Hu Q., Liu Q., Li H., Zhou Y., He T., Liang Q., Liu Y., Yuan X. et al. (2010). Crystal structure of the Caenorhabditis elegans apoptosome reveals an octameric assembly of CED-4. Cell 141, 446-457. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddien P. W., Cameron S. and Horvitz H. R. (2001). Phagocytosis promotes programmed cell death in C. elegans. Nature 412, 198-202. 10.1038/35084096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynaud K. and Driancourt M. A. (2000). Oocyte attrition. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 163, 101-108. 10.1016/s0303-7207(99)00246-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts L. M., Visser J. A. and Ingraham H. A. (2002). Involvement of a matrix metalloproteinase in MIS-induced cell death during urogenital development. Development 129, 1487-1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruault M., Brun M. E., Ventura M., Roizès G. and De Sario A. (2002). MLL3, a new human member of the TRX/MLL gene family, maps to 7q36, a chromosome region frequently deleted in myeloid leukaemia. Gene 284, 73-81. 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00392-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryoo H. D., Bergmann A., Gonen H., Ciechanover A. and Steller H. (2002). Regulation of Drosophila IAP1 degradation and apoptosis by reaper and ubcD1. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 432-438. 10.1038/ncb795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakahira H., Enari M. and Nagata S. (1998). Cleavage of CAD inhibitor in CAD activation and DNA degradation during apoptosis. Nature 391, 96-99. 10.1038/34214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamaki K. and Satou Y. (2009). Caspases: evolutionary aspects of their functions in vertebrates. J. Fish Biol. 74, 727-753. 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2009.02184.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh Y., Kobayashi Y., Takeuchi A., Pages G., Pouyssegur J. and Kazama T. (2011). Deletion of ERK1 and ERK2 in the CNS causes cortical abnormalities and neonatal lethality: Erk1 deficiency enhances the impairment of neurogenesis in Erk2-deficient mice. J. Neurosci. 31, 1149-1155. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2243-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schile A. J., Garcia-Fernandez M. and Steller H. (2008). Regulation of apoptosis by XIAP ubiquitin-ligase activity. Genes Dev. 22, 2256-2266. 10.1101/gad.1663108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenmann Z., Assa-Kunik E., Tiomny S., Minis A., Haklai-Topper L., Arama E. and Yaron A. (2010). Axonal degeneration is regulated by the apoptotic machinery or a NAD+-sensitive pathway in insects and mammals. J. Neurosci. 30, 6375-6386. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0922-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholl F. A., Dumesic P. A., Barragan D. I., Harada K., Bissonauth V., Charron J. and Khavari P. A. (2007). Mek1/2 MAPK kinases are essential for Mammalian development, homeostasis, and Raf-induced hyperplasia. Dev. Cell 12, 615-629. 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham S. (1998). Identification of multiple Caenorhabditis elegans caspases and their potential roles in proteolytic cascades. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 35109-35117 10.1074/jbc.273.52.35109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham S. and Horvitz H. R. (1996). An alternatively spliced C. elegans ced-4 RNA encodes a novel cell death inhibitor. Cell 86, 201-208. S0092-8674(00)80092-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrard R., Luehr S., Holzkamp H., McJunkin K., Memar N. and Conradt B. (2017). miRNAs cooperate in apoptosis regulation during C. elegans development. Genes Dev. 31, 209-222. 10.1101/gad.288555.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shub D. A. (1994). Bacterial viruses: bacterial altruism? Curr. Biol. 4, 555-556. 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00124-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon D. J., Weimer R. M., McLaughlin T., Kallop D., Stanger K., Yang J., O'Leary D. D. M., Hannoush R. N. and Tessier-Lavigne M. (2012). A caspase cascade regulating developmental axon degeneration. J. Neurosci. 32, 17540-17553. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3012-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon D. J., Pitts J., Hertz N. T., Yang J., Yamagishi Y., Olsen O., Tešić Mark M., Molina H. and Tessier-Lavigne M. (2016). Axon degeneration gated by retrograde activation of somatic pro-apoptotic signaling. Cell 164, 1031-1045. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slee E. A., Harte M. T., Kluck R. M., Wolf B. B., Casiano C. A., Newmeyer D. D., Wang H.-G., Reed J. C., Nicholson D. W., Alnemri E. S. et al. (1999). Ordering the cytochrome c-initiated caspase cascade: hierarchical activation of caspases-2, -3, -6, -7, -8, and -10 in a caspase-9-dependent manner. J. Cell Biol. 144, 281-292. 10.1083/jcb.144.2.281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector M. S., Desnoyers S., Hoeppner D. J. and Hengartner M. O. (1997). Interaction between the C. elegans cell-death regulators CED-9 and CED-4. Nature 385, 653-656. 10.1038/385653a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanfield G. M. and Horvitz H. R. (2000). The ced-8 gene controls the timing of programmed cell deaths in C. elegans. Mol. Cell 5, 423-433. 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80437-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss K. M., Martins L. M., Plun-Favreau H., Marx F. P., Kautzmann S., Berg D., Gasser T., Wszolek Z., Müller T., Bornemann A. et al. (2005). Loss of function mutations in the gene encoding Omi/HtrA2 in Parkinson's disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14, 2099-2111. 10.1093/hmg/ddi215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subasic D., Stoeger T., Eisenring S., Matia-González A. M., Imig J., Zheng X., Xiong L., Gisler P., Eberhard R., Holtackers R. et al. (2016). Post-transcriptional control of executioner caspases by RNA-binding proteins. Genes Dev. 30, 2213-2225. 10.1101/gad.285726.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston J. E., Schierenberg E., White J. G. and Thomson J. N. (1983). The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 100, 64-119. 0012-1606(83)90201-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W., Gould T. W., Vinsant S., Prevette D. and Oppenheim R. W. (2003). Neuromuscular development after the prevention of naturally occurring neuronal death by Bax deletion. J. Neurosci. 23, 7298-7310. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-19-07298.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suska A., Miguel-Aliaga I. and Thor S. (2011). Segment-specific generation of Drosophila Capability neuropeptide neurons by multi-faceted Hox cues. Dev. Biol. 353, 72-80. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.02.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y., Imai Y., Nakayama H., Takahashi K., Takio K. and Takahashi R. (2001). A serine protease, HtrA2, is released from the mitochondria and interacts with XIAP, inducing cell death. Mol. Cell 8, 613-621. 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00341-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki J., Denning D. P., Imanishi E., Horvitz H. R. and Nagata S. (2013). Xk-related protein 8 and CED-8 promote phosphatidylserine exposure in apoptotic cells. Science 341, 403-406. 10.1126/science.1236758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang D., Kang R., Berghe T. V., Vandenabeele P. and Kroemer G. (2019). The molecular machinery of regulated cell death. Cell Res. 29, 347-364. 10.1038/s41422-019-0164-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Technau G. and Heisenberg M. (1982). Neural reorganization during metamorphosis of the corpora pedunculata in Drosophila melanogaster. Nature 295, 405-407. 10.1038/295405a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry N. A., Bull H. G., Calaycay J. R., Chapman K. T., Howard A. D., Kostura M. J., Miller D. K., Molineaux S. M., Weidner J. R., Aunins J. et al. (1992). A novel heterodimeric cysteine protease is required for interleukin-1β processing in monocytes. Nature 356, 768-774. 10.1038/356768a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmons A. K., Mondragon A. A., Meehan T. L. and McCall K. (2017). Control of non-apoptotic nurse cell death by engulfment genes in Drosophila. Fly (Austin) 11, 104-111. 10.1080/19336934.2016.1238993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokuyasu K. T., Peacock W. J., and Hardy R. W. (1972). Dynamics of spermiogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster. I. Individualization process. Z. Zellforsch. Mikrosk. Anat. 124, 479-506. 10.1007/BF00335253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]