Abstract

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are critical mediators of peripheral immune tolerance. Tregs suppress immune activation against self-antigens and are the focus of cell-based therapies for autoimmune diseases. However, Tregs circulate at a very low frequency in blood, limiting the number of cells that can be isolated by leukapheresis. To effectively expand Tregs ex vivo for cell therapy, we report the metabolic modulation of T cells using mono-(6-amino-6-deoxy)-β-cyclodextrin (βCD-NH2) encapsulated rapamycin (Rapa). We used a computational model to qualitatively describe the kinetics of Treg expansion. Encapsulating Rapa in β-cyclodextrin increased its aqueous solubility ~154-fold and maintained bioactivity for at least 30 days. βCD-NH2-Rapa complexes (CRCs) enriched the fraction of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ mouse T (mT) cells and human T (hT) cells up to 6-fold and up to 2-fold respectively and suppressed the overall expansion of effector T cells by 5-fold in both species. Combining CRCs and transforming growth factor beta-1 (TGF-β1) synergistically promoted the expansion of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ T cells. CRCs significantly reduced the fraction of pro-inflammatory interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) expressing CD4+ T cells, suppressing this Th1-associated cytokine while enhancing the fraction of IFN-γ− tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) expressing CD4+ T cells. The computational model describes the influence of the composition of the initial cell population on the enrichment of Tregs in vitro and reveals how differences in the expansion kinetics of mT and hT cells result in differences in their susceptibility to immunophenotypic modulation. CRCs may be an effective and potent means for phenotypic modulation of T cells and the enrichment of Tregs in vitro and our findings contribute to the development of experimental and analytical techniques for manufacturing Treg based immunotherapies.

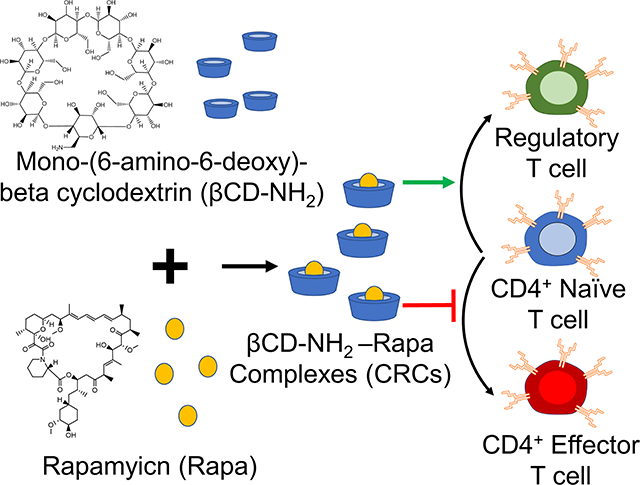

Graphical Abstract

Rapamycin encapsulated in mono-(6-amino-6-deoxy)-beta cyclodextrin efficiently expands regulatory T cells for cell-based immunotherapy.

Introduction

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are a subset of T cells that suppress aberrant activation of self-reactive effector lymphocytes and are widely regarded as the primary mediators of peripheral tolerance 1. Cell-based therapy using Tregs effectively treats autoimmune diseases such as arthritis and type 1 diabetes in animal models and at least one clinical trial (NCT02772679) is underway to evaluate efficacy in humans 2–5. However, sourcing Tregs from leukapheresis is inefficient as they circulate at a low frequency (3–5%) in the blood and therefore ex vivo expansion is required to enhance their numbers. Current expansion methods, which use natural or artificial antigen-presenting cells and interleukin-2 (IL-2), induce the activation of not only Tregs but also conventional T cells6, 7. Because Tregs divide more slowly than effector T cells, the latter may significantly outgrow Tregs 8. Therefore, Tregs must be highly purified and sorted to avoid transfusion of T effector cells, which can be challenging 9. Furthermore, Treg-mediated suppression could diminish after repetitive stimulation10. These requirements for expanding and isolating Tregs ex vivo limit their use for cell therapy.

One method to efficiently enhance Tregs is by expanding T cells in medium containing rapamycin (Rapa), a carboxylic lactone–lactam triene macrolide with antifungal, antitumor, anti-inflammatory properties 11. Rapa is administered orally or intravenously for systemic immunosuppression to prevent organ transplant rejection 12, 13. Rapa inhibits the serine/threonine protein kinase called mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), which is involved in a broad range of physiological processes linked to the control of cell cycle 14. Consistent with this mechanism, Rapa locks T cell-cycle progression from G1 to S phase after activation, enhances Treg number and maintains their function by preferentially reducing proliferation of effector T cells, while minimally affecting the regulatory T cell subset 15–18. Rapa induces operational tolerance and suppresses the proliferation of effector T cells and decreases the production of proinflammatory cytokines by T cells in vivo and in vitro 19–22. However, the poor aqueous solubility of Rapa, low stability in serum and short half-life (~10 hours at 37°C) limits bioavailability and uptake by T cells 23, 24.

Cyclodextrin monomers are well characterized cyclic oligosaccharides that form complexes with drug molecules via secondary hydrophobic interactions 25. The formation of inclusion complexes with small molecule drugs delays the rate of drug release beyond that of diffusion alone 26. The most common pharmaceutical applications of beta-cyclodextrin (βCD) derivatives are as excipients in clinical drug formulations to enhance the aqueous solubility of the complexed species, to improve the aqueous stability, photostability, and bioavailability of complexed drugs 27. In vivo, βCDs have been shown to enhance drug absorption and oral bioavailability as well as facilitate drug transport across physiologic barriers and biological membranes. Complexes of Rapa with βCD derivatives improve solubility and stability of Rapa, while preserving bioactivity 28, 29. Prior experiments have quantified a Kd between Rapa and βCD derivatives in the micromolar range30. The high supramolecular affinity prolongs its bioavailability and therefore is an attractive choice for formulations to promote enhancements of the half-life of Rapa in vitro. The extended half-life of Rapa could synergize with other potent inducers of regulatory T cells, including transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β1), which mediates the transition of naïve T cells toward a regulatory phenotype with potent immunosuppressive potential 31.

To promote the enrichment of Tregs in vitro, we encapsulated and characterized the function of Rapa encapsulated in mono-(6-amino-6-deoxy)-β-cyclodextrin (βCD-NH2) forming cyclodextrin-Rapa complexes (CRCs). CRCs enhanced the solubility of Rapa in water 154 -fold and maintained bioactivity of Rapa for at least 30 days in solution. CRCs enriched the fraction by 5-fold of Tregs in vitro from both PBMC-isolated human T (hT) cells and splenocyte-isolated mouse T (mT) cells. CRCs synergize with TGF-β1 to enhance the enrichment of murine Tregs. The combination also enhanced the fraction of human Tregs over single factor treatments. CRCs reduced interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) expression by T cells and increased the fraction of T cells that expressed tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) without IFN-γ. In hT cells, combining CRC and TGF-β1 further enhanced the enrichment of IFN-γ− TNF-α+ T cells, while in mT cells the addition of TGF-β1 increased the fraction of IFN-γ+ T cells, both alone and in combination with CRCs.

We developed a computational model to describe the expansion kinetics of Treg enrichment. The model recapitulated key features associated with CRCs and TGF-β1 individually and in combination on Treg expansion. A sensitivity analysis demonstrated that the initial fraction of naïve T cells is critical for ensuring a high fraction of Tregs. CRCs are a potent delivery system for Rapa to enhance the preferential expansion of Tregs and inhibiting inflammatory T cells, and the model may serve to guide Treg expansion for manufacturing cellular immunotherapies.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Basal T cell culture media was prepared from RPMI medium 1640 powder (Gibco) supplemented with 10% HI-FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol and 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids. Primary mT and hT cell media used for expansion was further supplemented with 50 IU/mL murine recombinant IL-2 (Peprotech) and 50 IU/mL human recombinant IL-2 (Biolegend), respectively. Rapa was purchased from LC Laboratories. Mono-(6-amino-6-deoxy)-β-cyclodextrin, with an upper solubility limit of 4.2 wt% in water, was purchased from Cavcon (CAS#: 29390–67-8). Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Generation and Characterization of CRCs

CRCs were prepared by first creating 0%, 1%, 2%, 3%, and 4% (wt/v) solutions of βCD-NH2 in DI water. 500 μL of each solution was added to 1 mg of Rapa and vortexed at 3200 rpm for 5 minutes, and then agitation was maintained at 1500 rpm until sampling. The inclusion complexes were equilibrated over 7 days as previously reported. Subsequently, the solution was spun down (21000 rcf, 5 min) and the supernatant was collected and analyzed on day 7. The amount of Rapa in the supernatant was analyzed using UV-vis spectrophotometry (λ = 278 nm) (Figure S1a).

Primary T cell Isolation

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at UC San Diego. Primary murine T cells were freshly isolated from C57BL/6J mice. A single cell suspension of splenocytes was created and T cells were isolated via magnetic depletion using CD4+ or pan-T cell isolation kits (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Murine T cells were not cryopreserved as the cells were found to be sensitive to DMSO at concentrations greater than 1 %(v/v) and reconstituted murine T cells expanded less than freshly isolated cells (data not shown).

Primary hT cells were isolated from anonymous donor blood concentrate enriched in the buffy coat (Stanford Blood Bank and San Diego Blood Bank). PBMCs were enriched from buffy coat within 24 hours of collection using density separation in a Ficoll gradient (Lymphopure). PBMCs were then transferred to serum-free cell freezing media (Bambanker) and frozen overnight at −80 °C. Aliquots were then stored in liquid nitrogen and used within 6 months. Pan T cells were isolated from thawed PBMC aliquots using magnetic depletion (Dynabeads Untouched Human T cells, Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

In vitro T cell expansion assays

Primary mT and hT cells were isolated as previously described and resuspended in T cell culture media without IL-2. Mouse or human αCD3/αCD28 activator Dynabeads (Invitrogen) were added to mT and hT cells, respectively, according to manufacturer recommendations and cells were plated in 96 well plates. After one day of culture, recombinant murine or human IL-2 was added to cultures at a concentration of 50 IU/mL along with any factors being tested. On the seventh day of culture cells were enumerated with cell counting using a hemocytometer and analyzed with flow cytometry. In cultures testing the suppressive effects of DMSO- or βCD-NH2-solubilized Rapa, Rapa was added at concentrations of 10, 100 or 1000 nM and TGF-β1 was used at 5 ng/mL. DMSO concentration was maintained across groups at a concentration of 0.1% (v/v). For CFSE analysis, cells were stained prior to activation with Dynabeads with CFSE (CFSE Cell Division Tracker Kit, Biolegend) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cells stained with CFSE were analyzed after 72 hours with flow cytometry.

Cytokine Assay

Primary mT and hT cells were cultured as previously detailed. 5 days post activation with Dynabeads, the cells were restimulated with PMA and ionomycin and blocked with Brefeldin A (Cell Activation Kit with Brefeldin A, Biolegend) for 5 hours according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were then washed, stained, and analyzed with flow cytometry.

Flow Cytometry

Antibodies for anti-mouse CD25 (PC61), CD8α (53–6.7), CD4 (GK1.5), CD45 (30-F11), TNF-α (MP6-XT22), IFN-γ (XMG1.2), and anti-human CD8α (RPA-T8), CD4 (SK3), CD25 (M-A251), CD45 (HI30), TNF-α (Mab11), and IFN-γ (B27) were purchased from Biolegend. Antibodies for anti-mouse FoxP3 (FJK-16s) and anti-human FoxP3 (236A/E7), were purchased from eBioscience. Samples analyzed for FoxP3 expression were fixed and permeabilized using the FoxP3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (eBioscience) according to manufacturer supplies protocols. Samples analyzed for TNF-α and IFN-γ expression but not FoxP3 were fixed using the IC Fixation Buffer (eBioscience) and permeabilized using Permeabilization Buffer (eBioscience) according to manufacturer supplied protocols. All cells were gated based on forward and side scatter characteristics to limit debris. Gating for surface markers, cytokines, and FoxP3 were determined using fluorescence-minus-one controls.

Computational Modeling and Parameter Analysis

To calculate the parameter values in the model we used data sets from our experiments. To determine the sensitivity of the model outputs to initial model regulatory T cell (Tr) fraction the model was initialized with 1%, 2%, and 3% Tr with a fixed model effector T cell (Te) (36.5%) fraction and variable model naïve T cell (Tn) (62.5%, 61.5% and 60.5%.The range of initial Tr values examined, as well as the starting Te and Tn values, were informed by analysis of T cell isolations and naïve T cell staining for CD62L and CD44. To determine the sensitivity of the model to initial Te fraction the model was initialized with 18.2%, 36.5% and 54.7% Te, with a fixed Tr (2%) and variable Tn (79.8%, 61.5%, 43.3%). An Excel sheet detailing parameter calculation and all code used to generate the model may be found at https://github.com/Shah-Lab-UCSD/Treg_Enrichement_Model_In_Vitro. All code was written to be compatible with Python 3.7.6.

Results

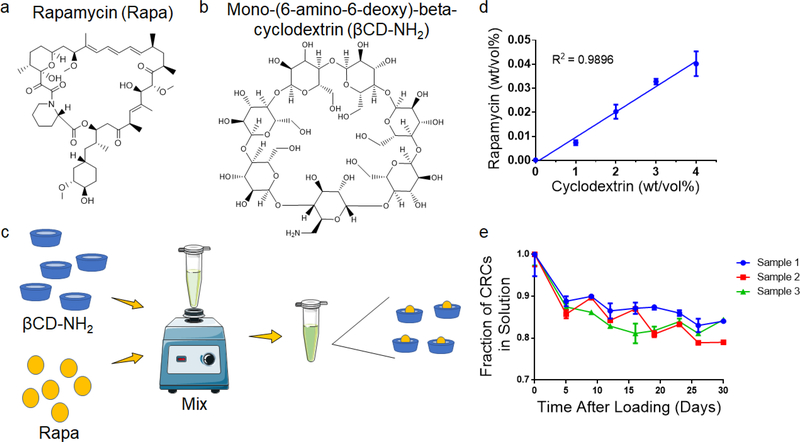

Mono-(6-amino-6-deoxy)-beta-cyclodextrin increases aqueous solubility of Rapa

To test the encapsulation of Rapa and improve the aqueous solubility, we used the βCD Mono-(6-amino-6-deoxy)-beta-cyclodextrin (βCD-NH2), forming βCD-NH2-Rapa inclusion complexes (Figure 1a, b). We first measured loading of Rapa in 0–4 % (w/v) βCD-NH2s in deionized water (Figure 1c). The loading of Rapa in the inclusion complexes was quantified using a standard curve (Figure S1a). The amount of Rapa in solution was proportional to the βCD-NH2 concentration and achieved a maximum loading of 4.02 ± 0.52 mg/mL in a 4 wt% solution of βCD-NH2 on day 7 (Figure 1d). The supernatant of the solution prepared without βCD-NH2 did not have a detectable amount of Rapa. To test the stability of the inclusion complex, CRC containing supernatant was transferred to new tubes that were incubated at room temperature over 30 days. In all samples, the amount of Rapa initially decreased and equilibrated after 7 days at 82.5% ± 1.7% of the initial concentration (Figure 1e).

Figure 1. Complexation with mono-(6-amino-6-deoxy)-beta-cyclodextrin enhances the aqueous solubility of rapamycin.

Chemical structure of (a) rapamycin (Rapa) and (b) Mono-(6-amino-deoxy)-beta-cyclodextrin (βCD-NH2) (c) Schematic for βCD-Rapa complexes (CRC). (d) Quantification of the Rapa loading in βCD-NH2. (e) Stability of CRC in solution over 30 days. Data in (d) represent the mean ± s.d. for n=3 independent experiments. Data in e represent the mean mean ± s.d. for n=3 technical replicates.

Rapa preferentially expands Tregs

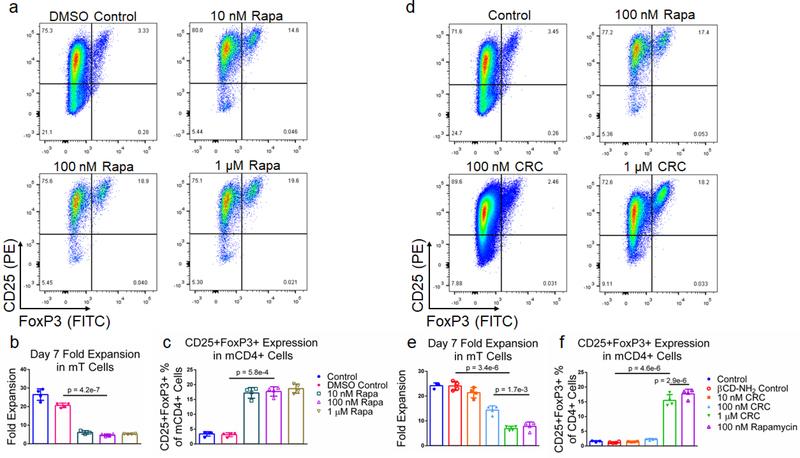

To test the suppressive activity of Rapa on T cell proliferation and enriching regulatory T cells (Tregs), we measured its dose-dependent effect in vitro. mT cells were isolated from splenocytes using magnetic bead-based depletion. Approximately 90% of the cells were either CD4+ or CD8+ T cells post-enrichment (Fig S1b.). We tested a broad range of Rapa concentrations (1 μM, 100 nM, 10 nM) (Figure 2a) and measured fold-expansion and the frequency of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ T cells relative to the total number of CD4+ T cells seven days post-activation. T cell expansion in 1 μM Rapa (5.26 ± 0.15) was comparable to 10 nM (6.13 ± 0.96) and 100 nM concentration (4.65 ± 0.63 -fold expansion) (Figure 2b), and were significantly lower compared to the Dynabead-only (25.8 ± 1.2) and DMSO controls (20.7 ± 1.2 -fold expansion). The fraction of CD4+ T cells that were also CD25+FoxP3+ was similar at 10 nM (10.3% ± 1.3%), 100 nM (10.3% ± 1.6%), and 1 μM (12.2% ± 0.7%) and significantly higher compared with the Dynabead-only (2.96% ± 1.51%) and DMSO controls (1.54% ± 0.78%) (Figure 2c). To examine the effects of DMSO-solubilized Rapa on expansion of CD25hi and CD25lo CD4+ T cell subsets, we conducted a proliferation assay using carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE). In the absence of Rapa, CD25lo T cells proliferated more than CD25hi T cells. When 100 nM Rapa was added, both CD25hi and CD25lo T cells proliferated a similar amount, with both groups expanding less than controls (Figure S2a).

Figure 2. Rapa and CRCs suppress mouse T cell expansion and enhance Tregs.

(a) Representative flow cytometry plots of CD25+FoxP3+ CD4+ mouse T (mT) cells. Quantification of the fold expansion of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (b) and the fraction of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ T cells (c) after 7 days of expansion at a range of Rapa concentrations. (d) Representative flow cytometry plots of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ T cells. Quantification of the fold expansion of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (e) and the fraction of CD25+FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells (f) after 7 days of expansion at a range of CRC concentrations. Data represents the mean ± s.d. (n=4). Experiments were repeated at least three times.

Cyclodextrin-Rapa complexes potently suppress T cell proliferation

To test the bioactivity of Rapa encapsulated in CRCs, we compared the phenotypic modulation of murine T cells mediated by CRCs and Rapa solubilized in a DMSO carrier (Figure 2d). In contrast to DMSO-solubilized Rapa, T cell expansion was strongly dependent on the concentration of CRCs, but unaffected by βCD-NH2 alone (Figure 2e). 10 nM CRCs did not substantially affect T cell expansion (21.4 ± 2.1-fold) compared to the Dynabead-only control (24.2 ± 1.2 -fold). T cell expansion with 100 nM CRCs (14.4 ± 1.7 -fold) and 1μM CRCs (6.93 ± 0.91 -fold) was significantly lower than the Dynabead-only and βCD-NH2 (24.1 ± 1.6-fold) controls. In addition, the suppression of T cell expansion mediated by 1μM CRCs was comparable to 100 nM DMSO-solubilized Rapa (7.81 ± 1.75 -fold expansion). Similarly, the enrichment of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ murine T cells was comparable between the 10 nM CRC (1.46% ± 0.10%), Dynabead-only control (1.57% ± 0.25%), and βCD-NH2 control (1.21% ± 0.21%) (Figure 2f). These cells were significantly enriched with 100 nM CRC (2.29% ± 0.26%) and 1 μM CRC (5.86% ± 0.28%).

TGF-β1 and CRCs promote Treg enrichment through distinct mechanisms

To test if combinations of immunomodulatory factors might further enrich CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs, we tested transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β1) in combination with Rapa. Murine T cells were cultured in media containing either 5 ng/mL TGF-β1, 1 μM CRCs or both factors and quantified the expansion of T cells as well as the fraction of CD25+FoxP3+CD4+ T cells (Figure 3a). TGF-β1 alone did not suppress the expansion of T cells (26.8 ± 3.2 -fold) relative to the Dynabead-only control (24.2 ± 1.2 -fold). However, TGF-β1 in combination with 1 μM CRCs suppressed T cell expansion (6.73 ± 0.82 -fold expansion) which was comparable to 1 μM CRCs alone (6.93 ± 0.91 -fold expansion) (Figure 3b). TGF-β1 in combination with 1 μM CRCs (21.1% ± 0.46%) increased the fraction of Tregs more than TGF-β1 (10.8% ± 0.46%) or 1 μM CRCs (5.86% ± 0.28%) alone (Figure 3c). Strikingly, this enrichment was greater than the sum of the enhancement mediated by either CRCs or TGF-β1 alone (Figure 3d). We compared CD4+FoxP3+ Treg and the CD4+FoxP3− T cell counts between the test groups (Figure 3e). 100 nM and 1 μM CRCs reduced the number of total CD4+FoxP3− cells compared with the Dynabead-only control but did not affect the number of Treg. In contrast, TGF-β1 increased the number of Treg relative to control but did not significantly affect proliferation of CD4+FoxP3− T cells. In combination, TGF-β1 and 1 μM CRC increased Treg and decreased CD4+FoxP3− T cells.

Figure 3. Mouse Tregs are enriched with combination of TGF-β1 and CRCs.

(a) Representative flow cytometry plots gated on CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ mT cells with TGF-β1, CRCs or both. Quantification of the fold expansion of splenic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (b) and the fraction of CD25+FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells (c) after 7 days of expansion. (d) Stacked columns representative of the additive enrichment in the fraction of CD25+FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells mediated with single-factor TGF-β1 (black) and CRCs (green) compared to the enrichment with combination TGF-β1 and CRCs (brown). (e) Quantification of CD4+FoxP3+ and CD4+FoxP3− T cells with CRCs and TGF-β1. In a-e, untreated, TGF-β1, CRCs, TGF-β1 and CRCs, and TGF-β1 and Rapa were compared. Data represents the mean ± s.d. (n=4). Experiments were repeated at least two times.

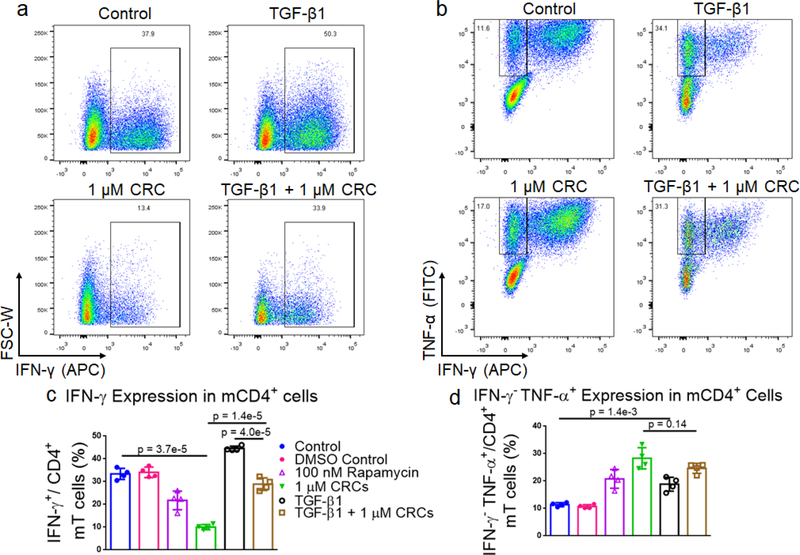

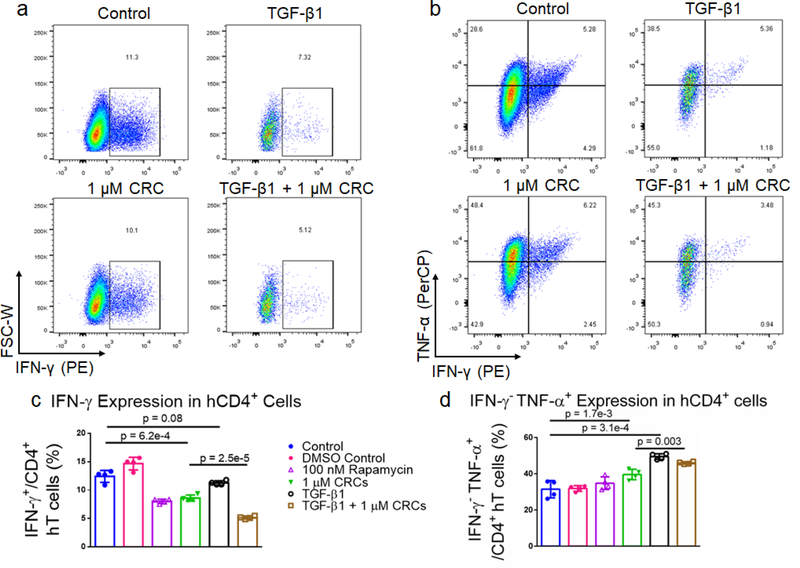

CRCs and TGF-β1 have opposing effects on IFNγ expression in murine T cells

As the immunophenotype of T cells is associated with its cytokine profile, we next measured the difference in production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in mT cells with combination of single factor CRCs and TGF-β1 (Figure 4a and 4b). The fraction of CD4+ IFN-γ+ T cells was significantly depleted in CRC-treated cells (10.0% ± 0.6%) relative to Dynabead-only control (30.6% ± 2.9%). CD4+ IFN-γ+ T cells were enriched in the presence of TGF-β1 alone (44.6% ± 1.0%) (Figure 4c). The combination of CRCs and TGF-β1 (28.9% ± 2.7%) was lower than TGF-β1 alone, but similar to the Dynabead-only and DMSO controls.

Figure 4. CRCs and TGF-β1 modulate cytokine expression in CD4+ murine T cells.

Representative flow cytometry plots showing the fraction of IFN-γ+ (a) and INF-γ−TNF-α+ (b) CD4+ mT cells when TGF-β1, CRCs or both are included in culture medium. Flow cytometry of IFN-γ+ (c) and INF-γ−TNF-α+ (d) CD4+ T cells after 7 days of expansion. In a-d, untreated cells, TGF-β1, CRCs, TGF-β1 and CRCs, and TGF-β1 and Rapa were compared. Data represents the mean ± s.d. (n=4). Experiments were repeated at least two times.

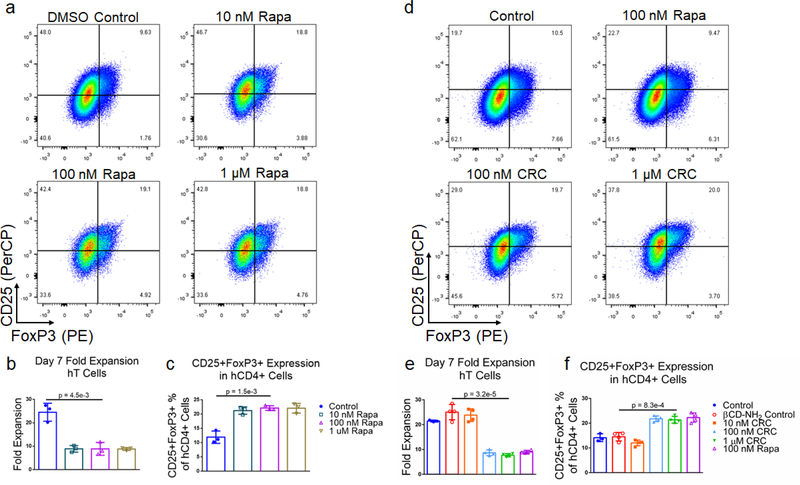

CRCs preferentially enrich CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ primary human T cells

We next tested the Rapa concentration-dependent enrichment of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ human Treg with DMSO-solubilized Rapa. T cells were enriched from donor derived PBMCs using magnetic depletion to a purity of approximately 85% CD8+ and CD4+ T cells (Figure S1c) and subsequently activated using Dynabeads. The suppression in hT cell expansion was similar at 1 μM (8.84 ± 0.62 -fold), 100 nM (8.88 ± 2.72 -fold), and 10 nM (8.92 ± 1.41 -fold) DMSO-solubilized Rapa, relative to the Dynabead-only control (24.5 ± 3.8 -fold) (Figure 5a and 5b). The enrichment in CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ human Treg at 1 μM (22.1% ± 1.7%), 100 nM (22.2% ± 0.81%), and 10 nM Rapa (21.3% ± 1.3%) was similar and greater than the Dynabead-only control (12.0% ± 2.2%) (Figure 5c).

Figure 5. Rapa and CRCs suppress human T cell expansion and enhances human Treg.

(a) Representative flow cytometry of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ human T (hT) cells when Rapa is include in the culture medium. Quantification of the fold expansion of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (b) and the fraction of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ T cells (c) after 7 days of expansion with varying concentrations of Rapa. (d) Representative flow cytometry of CD4+ CD25+FoxP3+ T cells when CRCs are included in culture medium. Quantification of the fold expansion of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (e) and the fraction of CD25+FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells (f) after 7 days of expansion with multiple concentrations of CRCs. Data represents the mean ± s.d. (n=4). Experiments were repeated at least three times.

To test the bioactivity of CRCs with hT cells, we measured CRC-mediated suppression on hT cell expansion with 1 μM, 100 nM, and 10 nM CRCs (Figure 5d). At 10 nM, T cell expansion was comparable to the Dynabead-only control (23.8 ± 2.5 -fold expansion) as well as the βCD-NH2 control (25.0 ± 2.7 -fold expansion). However, at 100 nM (8.7 ± 1.2 -fold) and 1 μM CRC (7.7 ± 0.6 -fold), suppression in T cell expansion was comparable to DMSO-solubilized 100 nM Rapa (9.0 ± 0.6 -fold) (Figure 5e). Similarly, the enrichment of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs at 10 nM CRCs (12.0% ± 1.2%) was comparable to the Dynabead-control (14.1% ± 1.6%) and βCD-NH2 control (14.5% ± 1.5%). Enrichment at 100 nM (21.8% ± 1.2%) and 1 μM (21.4% ± 1.4%) CRCs was higher than the Dynabead-control and comparable to 100 nM DMSO-solubilized Rapa (22.3% ± 1.9%) (Figure 5f).

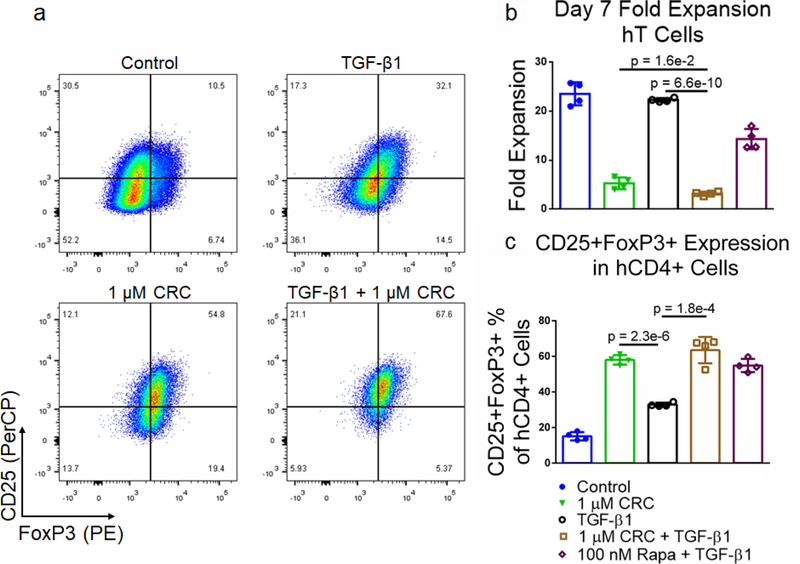

Expansion with TGF-β1 and CRCs results in high fraction of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ hT cells

To test the effect of TGF-β1 in combination with CRCs on Treg enrichment we cultured PBMC-derived hT cells with the same single-factor and combination treatments previously described for murine T cells (Figure 6a). CRCs in combination with TGF-β1 (3.2 ± 0.4 -fold expansion) suppressed hT cell proliferation more than CRCs (5.3 ± 1.2 -fold expansion) or TGF-β1 (22.3 ± 0.4 -fold expansion) alone (Figure 6b). The fraction of CD25+FoxP3+ T cells among CD4+ T cells was highest in the combination group (63.5% ± 7.4%), though the enrichment was not greater than the single treatment CRCs (58.1% ± 2.7%) and TGF-β1 (32.9% ± 0.6%) combined (Figure 6c).

Figure 6. Human Tregs are enriched with the combination of TGF-β1 and CRCs.

(a) Representative flow cytometry of CD25+FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells when TGF-β1, CRCs or both are included in culture media. Quantification of the fold expansion of splenic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (b) and the fraction of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ T cells (c) after 7 days of expansion. In a-c, untreated cells, TGF-β1, CRCs, TGF-β1 and CRCs, and TGF-β1 and Rapa were analyzed. Data represents the mean ± s.d. (n=4). Experiments were repeated at least two times.

TGF-β1 and CRCs reduce IFNγ expression, enrich IFNγ−TNFα+ human T cells

To characterize the effect of CRCs on cytokine expression in hT cells alone and in combination with TGF-β1, we expanded T cells as previously described. After 7 days of expansion, the cells were re-stimulated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and ionomycin and analyzed for interferon-γ (IFNγ) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) expression (Figure 7a and 7b). DMSO-solubilized 100 nM Rapa (8.1% ± 0.4%) and 1 μM CRCs (8.6% ± 0.5%) reduced IFNγ expression of CD4+ hT cells relative to a DMSO-treated control (14.7% ± 1.1%) and untreated control (12.4% ± 1.1%) (Figure 7c). TGF-β1 alone (11.3% ± 0.4%) did not reduce IFNγ relative to controls. However, TGF-β1 in combination with 1 μM CRCs (5.2% ± 0.3%) decreased IFNγ more than TGF-β1 or 1 μM CRCs alone. TGF-β1 (49.5% ± 1.6%) increased the fraction of IFNγ−TNFα+ more than the combination of 1 μM CRCs and TGF-β1 (46.0% ± 0.7%) relative to untreated control (31.5% ± 4.8%) (Figure 7d). DMSO-solubilized 100 nM Rapa (34.6% ± 4.3%) did not increase the IFNγ−TNFα+ fraction relative to DMSO containing controls (31.9% ± 1.5%), while 1 μM CRCs (39.6% ± 2.9%) enhanced the fraction relative to control.

Figure 7. CRCs and TGF-β1 modulate cytokine expression in CD4+ human T cells.

Representative flow cytometry of IFN-γ+ (a) and INF-γ−TNF-α+ (b) CD4+ T cells when TGF-β1, CRCs or both are included in culture media. Flow cytometry of IFN-γ+ (c) and INF-γ−TNF-α+ (d) CD4+ T cells after 7 days of expansion. In a-d, untreated cells, TGF-β1, CRCs, TGF-β1 and CRCs, and TGF-β1 and Rapa were compared. Data represents the mean ± s.d. (n=4). Experiments were repeated at least two times.

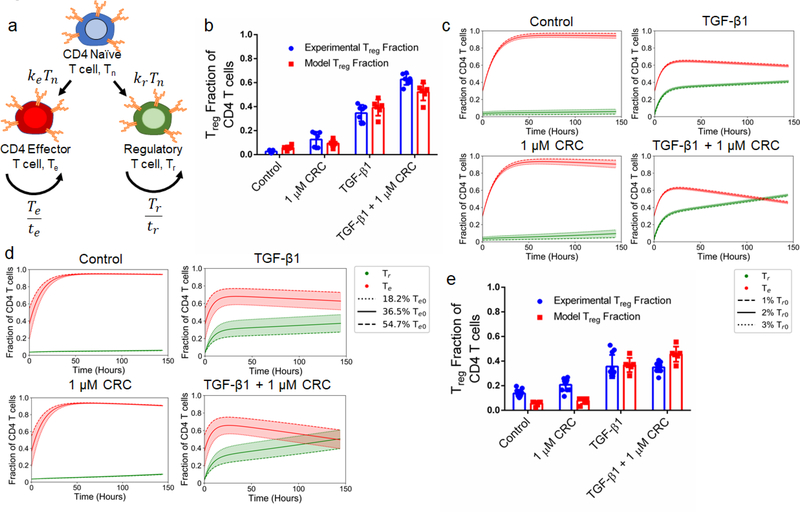

Computational model characterizes the dependence of Treg enrichment to initial cell population

To explain how culture conditions and starting cell populations contribute to experimental outcomes and variance, we developed and optimized a model describing the kinetics of differentiation and expansion of model naïve (Tn), regulatory (Tr) and effector (Te) CD4+ T cells (Figure 8a). Details of the model and parameter fitting may be found in the Supplementary Information. First, we looked at the sensitivity to the initial Tr population over a range of commonly reported Treg splenocyte fractions. We initialized the model with 1%, 2%, and 3% Tr with a fixed Te (36.5%) fraction and variable Tn (62.5%, 61.5% and 60.5%) fraction that correspond to the averages of values from isolated murine splenocytes analyzed via flow cytometry (Figure S1d). This revealed that the post-expansion Tr fraction was most sensitive to the initial Tr fraction in the 1 μM CRC condition with a range of 4.9% - 13.8%, while outcomes for control (3.0% - 8.7%), TGF-β1 (39.7% - 42.2%), and combination (53.1% - 55.6%) conditions are tightly grouped and independent of the initial Tr fraction (Figure 8b). The results from the model were consistent with experimental data for control (5.80% ± 1.66% vs 2.61% ± 1.03%), 1 μM CRC (9.38% ± 2.58% vs 12.6% ± 5.9%), and TGF-β1 (39.1% ± 6.1% vs 34.6% ± 6.3%), and slightly underestimated Tr enrichment by the combination of CRC/TGF-β1 (52.2% ± 6.5% vs 62.7% ± 4.2%), but still demonstrated a synergistic effect (Figure 8c). Due to the high variability in naïve T cell fraction in human peripheral blood samples, we next analyzed the sensitivity of final Tr fraction to the initial naïve-to-effector T cell ratio. We quantified the effect of changing the initial Te fraction between 18.2%, 36.5% and 54.7% while fixing the Tr fraction at 2%. The range of values for the initial Te fraction was chosen to cover the range of observed fractions of effector T cells seen in human and mouse samples. The impact of variance in initial Te fraction on the final Tr fraction was significantly higher with TGF-β1 (27.4% - 47.3%) and combination of CRC/TGF-β1 (39.4% - 60.5%), and minimal in the control (5.5% - 6.1%) and with CRCs only (9.0% - 9.7%) (Figure 8d). Finally, to characterize the role that the delay in hT cell expansion kinetics relative to mT cells plays in abrogating the synergistic effect of combination CRC/TGF-β1, a modified model was used in which expansion did not begin until 48 hours after differentiation. Results from the modified model revealed that the additive Treg enrichment observed with 1 μM CRCs (7.86% ± 2.35%) or TGF-β1 (36.8% ± 5.3%) alone was not significantly different than the combination of both factors (45.6% ± 5.6%) (Figure 8e).

Figure 8. Enrichment of Treg in vitro is enhanced with a high initial naïve-to-effector T cell ratio.

a,b. Schematic depicting the interactions between T cells in a model of T cell expansion (a) and side-by-side comparison of experimental data (red) and model predictions (blue) when of TGF-β1, CRCs, both, or neither (Control) are included in culture media (b). (c) Model predictions for the fraction of effector (red) and regulatory (green) T cells when simulations are initialized with 1%, 2% or 3% Treg in the starting population corresponding to the dashed, solid, and dotted lines respectively. (d) Model predictions for the fraction of effector (red) and regulatory (green) T cells when simulations are initialized with 54.7%, 36.5% or 18.2% effector T cells in the starting population corresponding to the dashed, solid, and dotted lines respectively. (e) Predictions for effector and regulatory T cell fractions when a two day delay is placed on T cell expansion to mimic hT cell expansion dynamics. In b, experimental data represents the mean ± s.d. (n=7) and model data represents the final values for the three simulations depicted in (c).

Discussion

Here we demonstrate Tregs are enriched up to 5-fold in vitro in which β-cyclodextrin encapsulated Rapa complex (CRC) plays a key role in the differential modulation of proliferating T cell subsets. The encapsulation of Rapa in the CRC enhanced its activity in vitro and delivery to T cells, synergizing with TGF-β1 to efficiently produce mouse and human Tregs. Encapsulation of Rapa in the CRC by equilibrium mixing was directly proportional to the concentration of the βCD-NH2 concentration, up to the limit of solubility of βCD-NH2. The CRC complex significantly improved the aqueous solubility of Rapa by over 2 orders of magnitude and was stable in solution for at least one month. The addition of CRCs in T cell growth medium selectively suppressed the expansion of CD4+FoxP3− T cells in a dose-dependent manner and enhanced the fraction of CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs with both mT and hT cells. The coadministration of the T cell modulating factor TGF-β1 and CRC enriched mouse and human Tregs through the expansion of CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs and suppression of CD4+FoxP3− T cells respectively, with evidence of synergism in mouse Treg expansion. The findings are consistent with the observations of CRC-mediated reduction in the expression of the inflammatory mediator, IFN-γ, in both mT and hT cells.

Mono-(6-amino-6-deoxy)-beta-cyclodextrin enhances the aqueous solubility of Rapa over 100-fold and is a stable carrier for Rapa. Mono-(6-amino-6-deoxy)-beta-cyclodextrin was chosen as it has significantly enhanced solubility compared to unmodified beta-cyclodextrin and previous reports found that hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin minimally improved Rapa solubility 32. The ~1:100 ratio of solubilized Rapa to βCD-NH2s is comparable to Rapa encapsulation with other βCD molecules. After an initial decrease in concentration βCD-NH2-Rapa complexes maintained a stable concentration in solution and retained their bioactivity for up to one month (Figure S3). The initial drop in concentration is likely due to the small fraction that dissociates to establish equilibrium.

The CRCs potently modulated both mT and hT cells, supporting the relevance of this delivery strategy for Rapa in generating Tregs in vitro. In prior work, particle systems composed of poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA), poly(d,l-lactide) (PDLLA), poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL), and poly(alkyl cyanoacrylates) (PACs) have been used to improve the bioavailability of Rapa in vivo and improved its delivery to target tissues before release 12, 33, 34. However, in contrast to in vivo delivery, particle-based Rapa delivery systems are unsuitable for in vitro expansion as their uptake by activated T cells is highly inefficient. Moreover, the high concentration of degradable synthetic polymers in vitro would likely be cytotoxic. The introduction of synthetic polymers would also increase the complexity of manufacturing in vitro generated Tregs.

The apparent effect of Rapa in the CRC was diminished by approximately 100-fold in mT cells and 10-fold in hT cells compared to DMSO-solubilized Rapa. In contrast to cyclodextrins, DMSO is a cell membrane permeabilizing agent that directly inserts and disrupts the cell membrane and thereby facilitates intracellular drug delivery. However, the use of DMSO for intracellular delivery is not a scalable strategy for T cell manufacturing in vitro. Consistent with prior results, we observe that CD4+ T cells are highly sensitive to the concentration of DMSO and even low doses potently suppresses their expansion 35. Moreover, DMSO are potentially toxic at the high concentrations that are often used to manufacture cells, which complicates direct use in patients, and its removal is a complex processes associated with a detrimental osmotic shock to the cells 36. In contrast, and consistent with prior reports, we observe that T cell growth, function and phenotype is not affected by βCD-NH2 alone.

The difference in the intracellular concentration of Rapa may have a considerable effect on the enrichment of Tregs because of the concentration-dependent effect on mTOR complex formation (mTORC1 and mTORC2). We observed that the suppression in mT cell expansion was dose dependent for 10 nm, 100 nm, and 1 μM CRC, while enrichment in Treg was observed for 1 μM CRC. These findings are consistent with previous reports, which have established that mTORC1 is more sensitive to Rapa-mediated inhibition than mTORC2 37. Inhibition of mTORC1 prevents the differentiation of T helper (Th) 1 CD4+ T cells, consistent with the reduction of IFN-γ expression of T cells expanded with CRCs, and is an important step for enriching Treg38 On the other hand, the inhibition of mTORC2 enhances the suppressive capacity of Treg39. Robust mTORC2 inhibition requires sustained exposure to higher concentrations of Rapa, and therefore CRCs are preferred over DMSO as they are an inert carrier and preserve bioactivity of Rapa, and thereby sustain presentation to T cells40.

The enhancement in murine Tregs with CRCs together with TGF-β1 was greater than the sum of Tregs when either factor was applied individually. CRCs increased the fraction Tregs primarily via suppression of CD4+CD25+FoxP3− T cell expansion whereas TGF-β1 increased the fraction of Tregs by increasing the absolute number of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ T cells. This observation is supported by prior observations of the synergistic effect of Rapa and TGF-β1 for the in vitro induction of Tregs from naïve CD4+ T cells. The in vitro enhancement of human Tregs from naïve T cells by TGF-β1 alone is consistent with prior reports. However, in contrast to splenocyte-isolated mT cells, naïve CD4+ T cells must be isolated from human blood and only make up 1–10% of leukocytes, with significant variation between donors. This variability supports the combined use of both Rapa and TGF-β1 to generate human Treg. Here, we confirmed that the immunomodulation by Rapa and TGF-β1 extends to polyclonal T cells, consisting of both mature and naïve T cells (Figure S1d). The enhancement of the Treg from heterogenous T cell subsets is clinically relevant as PBMC-isolated T cells are often a combination of memory T cells and recently activated naïve T cells.

The reduction in IFNγ expression and enrichment of IFNγ−TNFα+ mediated by CRCs was consistently observed in both mT and hT cells. In mT cells, TGF-β1 enhanced the expression of both IFNγ and TNFα. This is consistent with prior reports characterizing the inhibition of naïve murine T cell activation and enhancement of Th1 cells in a mixed T cell population by TGF-β1 41. Because the initially isolated T cells contained a mixed population of T cell subsets, the TGF-β1 likely enhanced activation of pre-existing Th1 T cells. In contrast, with hT cells, the combination of TGF-β1 and CRCs decreased the fraction of IFNγ+ T cells more than either factor individually. The difference in cytokine expression between mT and hT cells suggests that the source of T cells for Treg enrichment is important. Furthermore, TGF-β1 did not enhance IFN-γ expression in hT cells and supports the translation of this approach for Treg expansion in the clinic, where it will likely be difficult to enrich high numbers of naïve autologous T cells. CRCs enhanced the fraction of IFN-γ−TNF-α+ T cells. This observation is consistent with prior reports that have demonstrated that Treg priming via the TNFRII receptor enhances Treg function and TNFRII marks a highly immunosuppressive Tregs subset 42.

The kinetic growth model describing Treg expansion and differentiation supported the role of CRCs in mediating Treg enrichment primarily through suppression of effector T cell expansion, and that of TGF-β1 through the differentiation of naïve T cells into Tregs. Strikingly, the model accurately recapitulates the synergistic effect of CRCs and TGF-β1 in murine T cells, and the incorporation of a delay in T cell expansion abrogates this effect, providing a possible explanation for why synergism is not observed under the same conditions with hT cells. However, the model under-represents the fraction of Tregs in the murine combination condition, and in human control and CRC only conditions. CRCs inhibit IFN-γ, a key driver of Th1 differentiation. Thus, in the combination conditions the rate of differentiation into effector CD4 T cells is likely lower than predicted by the model, and a larger fraction differentiates into Tregs. The model is also useful for evaluating the distribution of final T cell subsets based on the initial fractions and suggests that a high naïve-to-effector ratio improves the enrichment of Treg, confirming the importance of pre-sorting for naïve T cells before expansion and phenotypic modulation in clinical applications 43. As quality control guidelines for ACT based Treg therapies are established, this model may serve as the basis for a tool to determine product sensitivity to key input parameters and apply process controls to minimize variance in Treg manufacturing, a necessary step in developing good manufacturing practice protocols 44.

Conclusions

Our findings collectively suggest that the βCD-NH2 encapsulated Rapa enhances Treg in vitro. CRCs increase the bioavailability of Rapa due to strong hydrophobic interactions with βCD-NH2, and the stability of the inclusion complex was confirmed via spectrophotometry. Compared with DMSO, the CRCs (i) improve the solubility of Rapa without inducing T cell toxicity, (ii) shield Rapa from degradation, thereby increasing half-life and uptake by T cells, (iii) synergize with TGF-β1 to enhance preferential expansion of Treg. Additionally, CRCs significantly decrease the production of IFN-γ by effector T cells and thereby reduces naïve T cells differentiation into a Th1 phenotype. The enhancement in TNF-α expression may act to prime the Tregs and enhance functionality. The kinetic model recapitulates the synergism between the CRCs and TGF-β1 in modulating the kinetics of Treg expansion in vitro and evaluates parameters for scalable manufacturing methods for immune cell therapies with Treg.

While the current study investigated enhancement of polyclonal Treg in vitro, further development of CRCs in combination with TGF-β1 for in vivo local delivery could enable the enhancement of Treg for a number of local and systemic autoimmune diseases. Given that Rapa and TGF-β1 are clinically used therapies, their application for immune cell manufacturing could enable safer administration of Treg as a means to treat autoimmune disease either alone or in combination with therapeutics currently utilized in the clinic. It may be a means of abrogating the significant side effects that limit clinical application of these pleiotropic drugs by restricting their potent immunomodulatory effects to T cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The work was supported in part by a grant from the National Psoriasis Foundation and the American Cancer Society (IRG-15–172-45-IRG) and the Microenvironment in Arthritis Resource Center (MARC) at UC San Diego, supported by the NIH (P30 AR073761). D.A.M. and M.D.K. were supported by NIH through grants T32 AR064194 and T32 CA153915 respectively. The UC San Diego Academic Enrichment Program supported Y.Y.Y. through a McNair Scholarship. D.A.O. was supported through a California Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation Scholarship and the UC San Diego Initiative for Maximizing Student Development (IMSD) program supported through a grant from NIH/NIGMS R25 GM083275. The authors acknowledge helpful discussions with Cheryl Kim at the Flow Cytometry Core in the La Jolla Institute for Immunology. The La Jolla Institute of Immunology’s FACSAria II cell sorter was acquired through the NIH Shared Instrumentation Grant Program S10 RR027366.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no relevant competing financial interests or relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Sakaguchi S, Setoguchi R, Yagi H and Nomura T, Current topics in microbiology and immunology, 2006, 305, 51–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bluestone JA and Tang Q, Science, 2018, 362, 154–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marek-Trzonkowska N, Mysliwiec M, Dobyszuk A, Grabowska M, Derkowska I, Juscinska J, Owczuk R, Szadkowska A, Witkowski P, Mlynarski W, Jarosz-Chobot P, Bossowski A, Siebert J and Trzonkowski P, Clin Immunol, 2014, 153, 23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright GP, Notley CA, Xue SA, Bendle GM, Holler A, Schumacher TN, Ehrenstein MR and Stauss HJ, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2009, 106, 19078–19083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah NJ, Mao AS, Shih TY, Kerr MD, Sharda A, Raimondo TM, Weaver JC, Vrbanac VD, Deruaz M, Tager AM, Mooney DJ and Scadden DT, Nature biotechnology, 2019, 37, 293–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olden BR, Perez CR, Wilson AL, Cardle II, Lin YS, Kaehr B, Gustafson JA, Jensen MC and Pun SH, Advanced healthcare materials, 2019, 8, e1801188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verbeke CS, Gordo S, Schubert DA, Lewin SA, Desai RM, Dobbins J, Wucherpfennig KW and Mooney DJ, Advanced healthcare materials, 2017, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang Q, Henriksen KJ, Bi M, Finger EB, Szot G, Ye J, Masteller EL, McDevitt H, Bonyhadi M and Bluestone JA, Journal of Experimental Medicine, 2004, 199, 1455–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Putnam AL, Brusko TM, Lee MR, Liu W, Szot GL, Ghosh T, Atkinson MA and Bluestone JA, Diabetes, 2009, 58, 652–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakaguchi S, Wing K, Onishi Y, Prieto-Martin P and Yamaguchi T, International immunology, 2009, 21, 1105–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li J, Kim SG and Blenis J, Cell metabolism, 2014, 19, 373–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haeri A, Osouli M, Bayat F, Alavi S and Dadashzadeh S, Artificial cells, nanomedicine, and biotechnology, 2018, 46, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saber-Moghaddam N, Nomani H, Sahebkar A, Johnston TP and Mohammadpour AH, International immunopharmacology, 2019, 69, 150–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dobashi Y, Watanabe Y, Miwa C, Suzuki S and Koyama S, International journal of clinical and experimental pathology, 2011, 4, 476. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Battaglia M, Stabilini A, Migliavacca B, Horejs-Hoeck J, Kaupper T and Roncarolo MG, J Immunol, 2006, 177, 8338–8347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monti P, Scirpoli M, Maffi P, Piemonti L, Secchi A, Bonifacio E, Roncarolo MG and Battaglia M, Diabetes, 2008, 57, 2341–2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niu HQ, Li ZH, Zhao WP, Zhao XC, Zhang C, Luo J, Lu XC, Gao C, Wang CH and Li XF, Clinical and experimental rheumatology, 2019, 38, 58–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt A, Eriksson M, Shang MM, Weyd H and Tegner J, PloS one, 2016, 11, e0148474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esposito M, Ruffini F, Bellone M, Gagliani N, Battaglia M, Martino G and Furlan R, Journal of neuroimmunology, 2010, 220, 52–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shin H-J, Baker J, Leveson-Gower DB, Smith AT, Sega EI and Negrin RS, Blood, 2011, 118, 2342–2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wieder K, Hancock W, Schmidbauer G, Corpier C, Wieder I, Kobzik L, Strom T and Kupiec-Weglinski J, The Journal of Immunology, 1993, 151, 1158–1166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Setoguchi R, Matsui Y and Mouri K, European journal of immunology, 2015, 45, 893–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahalati K and Kahan BD, Clinical pharmacokinetics, 2001, 40, 573–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simamora P, Alvarez JM and Yalkowsky SH, International journal of pharmaceutics, 2001, 213, 25–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis ME and Brewster ME, Nature reviews Drug discovery, 2004, 3, 1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirayama F and Uekama K, Advanced drug delivery reviews, 1999, 36, 125–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stella VJ and He Q, Toxicologic pathology, 2008, 36, 30–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rouf MA, Vural I, Bilensoy E, Hincal A and Erol DD, J Incl Phenom Macro, 2011, 70, 167–175. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dou Y, Guo JW, Chen Y, Han SL, Xu XQ, Shi Q, Jia Y, Liu Y, Deng YC, Wang RB, Li XH and Zhang JX, J Control Release, 2016, 235, 48–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rohner NA, Schomisch SJ, Marks JM and von Recum HA, Mol Pharmaceut, 2019, 16, 1766–1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamagiwa S, Gray JD, Hashimoto S and Horwitz DA, J Immunol, 2001, 166, 7282–7289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim M.-s., Kim J.-s., Park HJ, Cho WK, Cha K-H and Hwang S-J, International journal of nanomedicine, 2011, 6, 2997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao J, Mo Z, Guo F, Shi D, Han QQ and Liu Q, Journal of biomedical materials research. Part B, Applied biomaterials, 2018, 106, 88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jhunjhunwala S, Balmert SC, Raimondi G, Dons E, Nichols EE, Thomson AW and Little SR, Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society, 2012, 159, 78–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holthaus L, Lamp D, Gavrisan A, Sharma V, Ziegler A-G, Jastroch M and Bonifacio E, Journal of immunological methods, 2018, 463, 54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thirumala S, Goebel WS and Woods EJ, Organogenesis, 2009, 5, 143–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toschi A, Lee E, Xu L, Garcia A, Gadir N and Foster DA, Molecular and cellular biology, 2009, 29, 1411–1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delgoffe GM, Pollizzi KN, Waickman AT, Heikamp E, Meyers DJ, Horton MR, Xiao B, Worley PF and Powell JD, Nature immunology, 2011, 12, 295–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Charbonnier LM, Cui Y, Stephen-Victor E, Harb H, Lopez D, Bleesing JJ, Garcia-Lloret MI, Chen K, Ozen A, Carmeliet P, Li MO, Pellegrini M and Chatila TA, Nature immunology, 2019, 20, 1208–1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Sengupta S, Sheen JH, Hsu PP, Bagley AF, Markhard AL and Sabatini DM, Molecular cell, 2006, 22, 159–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huss DJ, Winger RC, Peng H, Yang Y, Racke MK and Lovett-Racke AE, The Journal of Immunology, 2010, 184, 5628–5636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen X, Subleski JJ, Kopf H, Howard OZ, Männel DN and Oppenheim JJ, The Journal of Immunology, 2008, 180, 6467–6471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marin Morales JM, Munch N, Peter K, Freund D, Oelschlagel U, Holig K, Bohm T, Flach AC, Kessler J, Bonifacio E, Bornhauser M and Fuchs A, Frontiers in immunology, 2019, 10, 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eaker S, Armant M, Brandwein H, Burger S, Campbell A, Carpenito C, Clarke D, Fong T, Karnieli O, Niss K, Van’t Hof W and Wagey R, Stem cells translational medicine, 2013, 2, 871–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mayer A, Zhang Y, Perelson AS and Wingreen NS, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2019, 116, 5914–5919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.