Abstract

Objective

To describe characteristics of U.S. contraceptive non-users to inform tailored contraceptive access initiatives.

Study design

We used National Survey of Family Growth data from 2011 to 2017 to identify characteristics of contraceptive non-users compared to other women ages 15–44 at risk for unintended pregnancy. We also examined reasons for not using contraception by when non-users expected their next birth. We calculated unadjusted and adjusted prevalence ratios using two definitions of contraceptive non-use: (1) contraceptive non-use during the interview month, and (2) a more refined definition based on contraception use during the most recent month of sexual intercourse and expectation of timing of next birth. We considered p-values < 0.05 statistically significant.

Results

Approximately 20% (n = 2844) of 12,071 women at risk of unintended pregnancy were classified as standard contraceptive non-users. After adjusting for all other variables, non-users were more likely to be low-income, uninsured, never married, expect a birth within 2 years, and have zero or one parity. The top reasons for contraceptive non-use were not minding if they got pregnant (22.6%), worried about contraceptive side effects (21.0%), and not thinking they could get pregnant (17.6%). After applying the more refined non-user definition, we identified 5.7% (n = 721) of women as non-users; expecting a birth within 2–5 years and having a parity of one were associated with non-use after adjustment of all other factors.

Conclusion

Our more refined definition of non-users could be used in future studies examining the causes of unintended pregnancy and to inform programmatic interventions to reduce unintended pregnancy.

Implications

Describing contraceptive non-users and reasons for contraceptive non-use could help us better understand reasons for unintended pregnancy and inform tailored contraceptive access initiatives.

Keywords: Contraceptive non-use, Unintended pregnancy, Contraceptive access, National Survey of Family Growth

1. Introduction

The unintended pregnancy rate in the U.S. has hovered around 50% for the last 20 years, suggesting new efforts must be considered to reduce unintended pregnancy [1]. Pregnancies defined as unintended, which include mistimed or unwanted pregnancies, have long been considered to be associated with negative public health outcomes [2,3]. While an imperfect measure [4], unintended pregnancy prevention has been a primary goal of family planning efforts, in part, because of the adverse health and well-being outcomes for both the mother and child resulting from unintended pregnancies [[5], [6], [7]].

An effective way of preventing mistimed and unwanted pregnancies is providing adequate access to contraception. A number of initiatives, like the Contraceptive CHOICE Project and the Colorado Initiative to Reduce Unintended Pregnancy, have aimed to reduce barriers to long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) under the presumption that with greater access to these highly effective methods there will be fewer non-users and inconsistent users of contraception and, therefore, lower rates of unintended pregnancy [8,9]. In response to this enthusiasm for increasing LARC access and use, Thomas and Karpilow designed a simulation study based off the Contraceptive CHOICE Project to assess its impact on unintended pregnancy risk assuming an alternative scenario. Instead of contraceptive access increasing LARC use, as was observed, they assumed all non-users and condom users initiated use of shorter-acting, female-controlled methods like oral contraceptive pills [10]. They found more than 70% of the CHOICE Project's effect on reducing unintended pregnancy could have been achieved under this scenario, without any increase in LARC use. They also found that the total number of pregnancies would be reduced to a greater extent if non-users were to adopt condom use than if a comparable number of pill, patch, or ring users were to adopt LARC use [11]. These findings hinged on the percentage of women at risk of pregnancy who were considered non-users, and data characterizing contraceptive non-users on a national level is fairly limited [[12], [13], [14]]. There is also no consensus on how to define contraceptive non-users across studies.

Therefore, the objective of our study was to use the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) to describe the characteristics of the contraceptive non-user population in comparison to other reproductive age women at risk for unintended pregnancy. We have previously used the NSFG data to assess patterns and trends in contraceptive use in the US and reported that 9.8% of sexually active, low-income women at risk for unintended pregnancy who received contraceptive services in the past 12 months used no method in the month of the interview in 2013–2015 [15]. In this paper, we aim to provide a further examination of non-users at a broader level, including their reasons for not using contraception and expectations regarding the timing of future children.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study population

We analyzed data from female respondents in the 2011–2013, 2013–2015, and 2015–2017 NSFG public-use files [16]. The NSFG is conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Center for Health Statistics and funded by multiple federal agencies. The NSFG is a nationally representative survey of the noninstitutionalized, household population of the US including men and women ages 15–44 until 2015, then ages 15–49 in 2015 and later years. For our analysis, the study population was restricted to respondents ages 15–44 for consistency across the three survey periods. The survey collects information on sexual relationships, marriage, cohabitation, contraceptive use and pregnancy history through in-person interviews conducted in respondents' homes. Each survey period data release includes a female respondent file, a pregnancy history file and, as of 2002, a male respondent file. We analyzed data from the female respondent files and the pregnancy history files, which contain information on all reported pregnancies that occurred up to the time of interview, including timing of the last pregnancy. The female response rate was 73% in 2011–2013, 71% in 2013–2015, and 67% in 2015–2017; detailed information on fieldwork, questionnaires and analytic guidelines is available elsewhere [16]. The National Center for Health Statistics research ethics review board approved each data collection effort, and no additional review was required for this analysis, which the Institutional Review Board of the University of Southern Maine determined to not be human subjects research.

2.2. Current contraceptive method use

Female respondents were asked about contraception methods used during the month of the NSFG interview. Respondents were allowed to report up to four methods used that month, and the single most effective method reported, in terms of pregnancy prevention, was used for our analysis. In other parts of the interview, the NSFG also captures information on current pregnancy status, ever having had sexual intercourse, previous sterilization operations, and history of infecundity, which are used to determine a respondent's contraceptive use status. If a respondent reported non-use of contraception that month, her reason for non-method use is elicited from a list of response options.

2.3. At-risk of unintended pregnancy

For our analysis, female respondents were considered at risk of unintended pregnancy if they reported ever having had vaginal sex with a man, were not currently pregnant or seeking pregnancy, were not infecund for non-contraceptive reasons, and they reported their partner was not infecund for non-contraceptive reasons. This definition of at risk is the same as that used for the Healthy People 2020 Family Planning indicators 16.1 and 16.2 [17] and paralleled the at risk definition used for contraceptive care performance measures [18]. Postpartum women (< 2.5 months since birth) were considered at risk of unintended pregnancy because median return to ovulation can be as soon as 8 weeks' postpartum [19].

2.4. Non-users of contraception

Respondents were defined as standard non-users of contraception if they were at risk of unintended pregnancy (as defined above) and did not report using a contraceptive method during the month of interview. We compared demographic characteristics of non-users to women using any of the following contraceptive methods: sterilization (male or female), LARC methods, moderately effective methods, or less effective methods. Definitions used for method effectiveness categorization were consistent with the Office of Population Affairs' contraceptive care performance measure and Healthy People 2020 Family Planning indicators [17,20]. We calculated unadjusted prevalence ratios for demographic characteristics of these standard contraceptive non-users to determine what factors were associated with contraceptive non-use; referent groups were either the level with the lowest prevalence of non-use or the level with the greatest proportion of respondents. Demographic factors were selected based on previous associations with contraception non-use reported in the literature [12,13,15]. Prevalence ratios based on unweighted numerator counts > 10 and p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. We calculated adjusted prevalence ratios by including all of the variables in one statistical model with the standard contraceptive non-use definition as the outcome and all of the other variables as predictor variables.

We then examined non-users more closely, looking back at their sexual activity by month for the past year, which was reported in a part of the NSFG interview that captures information on any vaginal sex with a man (yes/no) by month for the past 3–4 years. Our “look back” approach was based on methodology used for previous studies examining sporadic contraceptive use patterns among NSFG female respondents [13,21]. Women defined as standard non-users who last had sex more than a year before the interview were no longer considered non-users in our refined definition because they had not been recently sexually active. We selected 12 months for the recall period to be consistent with previous studies [13].

For the remaining non-users who last had sex between 1 and 12 months prior to the interview, we determined pregnancy status and contraceptive method use at the time of last sex. In the NSFG, contraceptive method use was recorded by month for the past 3–4 years, and these months could be aligned with both the sexual activity record (described above) and pregnancy beginning and end months. Among women who were not pregnant at last sex (or had never even been pregnant), we aligned contraceptive and sex activity calendar months and determined whether they used any contraceptive method during the month of last sex. Consistent with our standard non-user categorization, we categorized method used for the month of last sexual activity according to the single most effective method used, in terms of pregnancy prevention (if more than one method was used) [22]. If sex occurred more than once in that month, it is possible that the reported contraceptive method was not used at all occasions; however, we used reported contraceptive method use in the month of last sex as an approximate measure of contraception use. For women who were pregnant at last sex or used contraception in the month at last sex, they were no longer considered non-users in our refined definition.

Finally, among women remaining as non-users after applying our more refined definition, we further classified them using their responses to a question in the NSFG regarding the expected timing of their next birth (“When do you [and your partner] expect your [next/first] child to be born [after this pregnancy]? Would you say within the next 2 years, 2-5 years from now, or more than 5 years from now?”). This question was re-introduced to the NSFG interview in 2011 following a period where it had been removed. This question is a key item used for calculating the revised Demographic and Health Survey measure of unmet need, a component measure of the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goal contraceptive use indicator [21,23]. Women who responded that they expected their next birth within the next 2 years were no longer considered non-users in our refined definition because we considered this group of women, who expected to become pregnant within the next 15 months, as distinct from other non-users of contraception who were not planning a pregnancy during this timeframe.

Therefore, the final group of contraceptive non-users included women who could more reliably be considered non-users at risk of unintended pregnancy because they: were not currently pregnant or seeking pregnancy, were not (or their partner was not) infecund for non-contraceptive reasons, did not expect a birth in the next 2 years, were not using contraception at the time of the interview, and either had sex that month or last had sex within the prior year while not pregnant and did not use contraception at that time. We calculated unadjusted prevalence ratios for demographic characteristics to determine what factors were associated with this refined definition of contraceptive non-use. We also calculated adjusted prevalence ratios by including all of the characteristics in one model with the refined definition of contraceptive non-use as the outcome and all of the other characteristics as predictors. Again, prevalence ratios based on unweighted numerator counts > 10 and p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

2.5. Reason for not using contraception

Finally, we examined the main reason for contraceptive non-use by the expected timing of next birth in order to understand what further factors might explain non-use among women at risk of unintended pregnancy, beyond expecting a birth within the next 2 years. Women who did not report using contraception, had sex in the month of the interview, were not surgically sterilized, and whose partner did not want her to become pregnant were asked about their reason(s) for not using birth control in the NSFG interview [24]. Therefore, this analysis pertained to a subset of the group of women defined as standard non-users. We excluded responses from women who volunteered that they were actually using a method, and from women who did not appear to be eligible for this series of questions.

All analyses were conducted with SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) and SUDAAN 11.0 (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina) and accounted for the complex sample design and sample weights of the NSFG.

3. Results

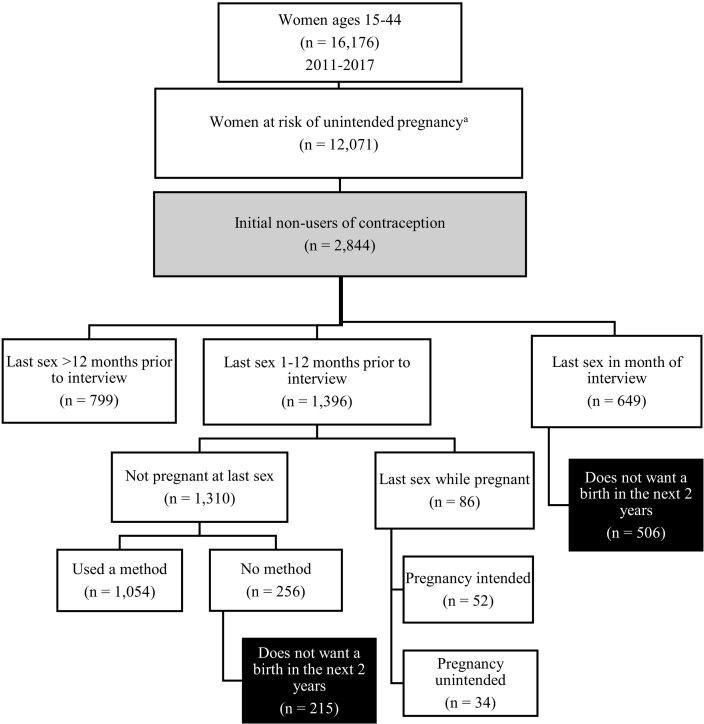

There were 16,176 female respondents ages 15–44 from the NSFG, 2011–2017, among whom 12,071 (76.2%) were considered at risk of unintended pregnancy at the time of the interview. Among these women, 2844 (20.5%) were defined as standard non-users of contraception (Fig. 1). These non-users of contraception were more likely to be teenagers, racial/ethnic minorities, low-income, use public insurance or be uninsured, speak a primary language other than English, never married, born outside the US, expecting a birth at some point in the future, and have parity of zero or one. The standard non-users were less likely to be currently affiliated with a Mainline Protestant religion vs. no religious affiliation. In the fully adjusted model, income 100–199% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL), being uninsured, never married, expecting a birth in the next 2 years, and being nulliparous or having a parity of one remained significant (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of female respondents ages 15–44 used to identify non-users of contraception, National Survey of Family Growth, 2011–2017.

Gray shaded box represents initial non-users of contraception and black boxes with white text represent refined non-users of contraception. aEver had vaginal sex with a man, not currently pregnant or seeking pregnancy, not infecund for non-contraceptive reasons, and their partner not infecund for non-contraceptive reasons.

Table 1.

Demographics of standard and refined definitions of non-users of contraception among women of reproductive age at risk for an unintended pregnancy a, NSFG 2011–2017 (n = 12,071)

| Standard non-users of contraception vs. contraceptive users |

Refined non-users of contraception vs. other women at risk of unintended pregnancy |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall col % |

Contraceptive users n = 9227 row % |

Standard non-users of contraception n = 2844 row % |

Prevalence ratio for non-user vs. user PR (95% CI) |

Adjusted prevalence ratio for non-user vs. user PR (95% CI)b |

Other women at risk of unintended pregnancy n = 11,350 row % |

Refined non-user of contraception n = 721 row % |

Prevalence ratio for non-user vs. other women PR (95% CI) |

Adjusted prevalence ratio for non-user vs. other women PR (95% CI)b |

|

| Overall | 79.5 | 20.5 | 94.3 | 5.7 | |||||

| Age | |||||||||

| 15–19 | 8.0 | 68.7 | 31.3 | 1.60 (1.40, 1.83) | 0.96 (0.81, 1.14) | 95.4 | 4.6 | 0.79 (0.56, 1.10) | 0.87 (0.66, 1.15) |

| 20–44 | 92.0 | 80.4 | 19.6 | Ref | Ref | 94.2 | 5.8 | Ref | Ref |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||||

| Hispanic | 20.2 | 76.6 | 23.4 | 1.34 (1.17, 1.52) | 1.07 (0.90, 1.27) | 93.9 | 6.1 | 1.14 (0.88, 1.48) | 1.08 (0.81, 1.44) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 56.2 | 82.5 | 17.5 | Ref | Ref | 94.7 | 5.3 | Ref | Ref |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 13.7 | 73.2 | 26.8 | 1.53 (1.36, 1.72) | 1.08 (0.95, 1.23) | 93.0 | 7.0 | 1.30 (0.99, 1.72) | 1.16 (0.93, 1.44) |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 9.9 | 77.1 | 22.9 | 1.31 (1.11, 1.55) | 1.03 (0.87, 1.23) | 94.7 | 5.3 | 1.00 (0.65, 1.54) | 1.00 (0.71, 1.39) |

| Income as a percentage of Federal Poverty Level | |||||||||

| < 100% | 26.0 | 75.1 | 24.9 | 1.48 (1.26, 1.74) | 1.18 (0.98, 1.41) | 93.0 | 7.0 | 1.56 (1.12, 2.18) | 1.18 (0.89, 1.56) |

| 100–199% | 21.6 | 76.5 | 23.5 | 1.40 (1.19, 1.64) | 1.22 (1.02, 1.45) | 93.4 | 6.6 | 1.45 (1.02, 2.07) | 1.14 (0.86, 1.52) |

| 200–399% | 28.1 | 82.7 | 17.3 | 1.03 (0.86, 1.22) | 1.00 (0.84, 1.19) | 95.2 | 4.8 | 1.07 (0.74, 1.55) | 1.01 (0.77, 1.32) |

| ≥ 400% | 24.3 | 83.2 | 16.8 | Ref | Ref | 95.5 | 4.5 | Ref | Ref |

| Insurance | |||||||||

| Private | 59.9 | 82.0 | 18.0 | Ref | Ref | 95.2 | 4.8 | Ref | Ref |

| Public | 22.4 | 75.8 | 24.2 | 1.35 (1.19, 1.53) | 1.13 (1.00, 1.28) | 92.5 | 7.5 | 1.58 (1.26, 1.99) | 1.20 (1.01, 1.43) |

| Uninsured | 17.7 | 75.7 | 24.3 | 1.35 (1.17, 1.56) | 1.18 (1.02, 1.37) | 93.5 | 6.5 | 1.37 (1.02, 1.86) | 1.11 (0.85, 1.44) |

| Primary language | |||||||||

| English | 89.7 | 80.8 | 20.0 | Ref | Ref | 93.8 | 6.2 | Ref | Ref |

| Spanish | 7.7 | 76.5 | 23.5 | 1.18 (1.00, 1.38) | 1.06 (0.85, 1.32) | 94.0 | 6.0 | 1.08 (0.72, 1.61) | 0.97 (0.62, 1.53) |

| Other | 2.6 | 70.7 | 29.3 | 1.47 (1.13, 1.90) | 1.32 (0.98, 1.77) | 94.9 | 5.1 | 1.19 (0.61, 2.32) | 1.15 (0.65, 2.03) |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Married | 41.4 | 88.6 | 11.4 | 1.03 (0.82, 1.30) | 1.20 (0.96, 1.49) | 94.4 | 5.6 | 1.03 (0.74, 1.43) | 1.19 (0.91, 1.54) |

| Cohabitating | 15.6 | 88.9 | 11.1 | Ref | Ref | 93.9 | 6.1 | Ref | Ref |

| Never married | 43.0 | 67.4 | 32.6 | 2.90 (2.39, 3.52) | 2.58 (2.28, 2.93) | 93.3 | 6.7 | 0.86 (0.63, 1.16) | 0.91 (0.72, 1.15) |

| Birth countryc | |||||||||

| US | 83.7 | 80.0 | 20.0 | Ref | Ref | 94.3 | 5.7 | Ref | Ref |

| Outside US | 16.3 | 76.9 | 23.1 | 1.15 (1.03, 1.30) | 1.11 (0.94, 1.32) | 94.2 | 5.8 | 1.01 (0.76, 1.35) | 0.98 (0.70, 1.33) |

| Current religious affiliationd | |||||||||

| No religion | 23.3 | 79.5 | 20.5 | Ref | Ref | 94.9 | 5.1 | Ref | Ref |

| Catholic | 21.2 | 79.4 | 20.6 | 1.01 (0.88, 1.15) | 0.97 (0.83, 1.14) | 94.1 | 5.9 | 1.15 (0.83, 1.59) | 1.01 (0.75, 1.36) |

| Baptist | 14.7 | 79.3 | 20.7 | 1.01 (0.86, 1.20) | 1.17 (0.92, 1.48) | 91.6 | 8.4 | 1.64 (1.19, 2.24) | 1.49 (0.96, 2.33) |

| Mainline Protestant | 7.7 | 85.0 | 15.0 | 0.73 (0.58, 0.93) | 0.87 (0.66, 1.14) | 96.2 | 3.8 | 0.75 (0.46, 1.23) | 0.98 (0.63, 1.53) |

| Fundamentalist | 5.1 | 79.7 | 20.3 | 0.99 (0.79, 1.25) | 1.08 (0.83, 1.41) | 94.7 | 5.3 | 1.03 (0.59, 1.79) | 1.01 (0.62, 1.65) |

| Other Protestant | 2.4 | 75.3 | 24.7 | 1.21 (0.86, 1.70) | 1.38 (0.90, 2.10) | 94.1 | 5.9 | 1.16 (0.58, 2.29) | 1.21 (0.50, 2.93) |

| Non-specific Protestant | 17.4 | 80.0 | 20.0 | 0.98 (0.83, 1.15) | 0.99 (0.81, 1.20) | 95.1 | 4.9 | 0.96 (0.70, 1.32) | 1.01 (0.71, 1.42) |

| Other religion | 7.8 | 75.5 | 24.5 | 1.20 (0.96, 1.50) | 1.07 (0.80, 1.44) | 94.5 | 5.5 | 1.07 (0.68, 1.69) | 1.02 (0.69, 1.51) |

| Expected timing of next birth | |||||||||

| Within 2 years | 10.7 | 76.0 | 24.0 | 1.46 (1.23, 1.74) | 1.24 (1.04, 1.47) | 100.0 | 0.0 | NA | NA |

| 2–5 years | 21.6 | 75.0 | 25.0 | 1.52 (1.33, 1.75) | 1.02 (0.89, 1.18) | 91.5 | 8.5 | 1.44 (1.12, 1.86) | 1.43 (1.02, 2.01) |

| 5 + years | 12.2 | 71.9 | 28.1 | 1.71 (1.46, 2.00) | 0.94 (0.78, 1.13) | 95.3 | 4.7 | 0.80 (0.57, 1.12) | 0.96 (0.63, 1.46) |

| Never/Do not know | 55.5 | 83.6 | 16.4 | Ref | Ref | 94.1 | 5.9 | Ref | Ref |

| Parity | |||||||||

| 0 | 36.7 | 73.4 | 26.6 | 1.99 (1.73, 2.28) | 1.52 (1.28, 1.81) | 95.1 | 4.9 | 0.88 (0.67, 1.15) | 1.13 (0.81, 1.57) |

| 1 | 17.9 | 74.0 | 26.0 | 1.94 (1.69, 2.23) | 1.69 (1.46, 1.96) | 92.1 | 7.9 | 1.42 (1.06, 1.90) | 1.34 (1.04, 1.72) |

| 2 or more | 45.4 | 86.6 | 13.4 | Ref | Ref | 94.5 | 5.5 | Ref | Ref |

| Ever had an abortion | |||||||||

| No | 87.6 | 79.2 | 20.8 | Ref | Ref | 94.3 | 5.7 | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 12.4 | 81.4 | 18.6 | 0.89 (0.76, 1.05) | 0.87 (0.75, 1.01) | 94.5 | 5.5 | 0.96 (0.70, 1.32) | 0.97 (0.75, 1.25) |

GED, General Education Development; CI, confidence interval; NHB, Non-Hispanic Black; NHO, Non-Hispanic Other; NHW, Non-Hispanic White; NSFG, National Survey of Family Growth; PR, prevalence ratio; SE, standard error.

At risk for unintended pregnancy included women who had ever had vaginal sex with a man, were not currently pregnant or seeking pregnancy, were not infecund for non-contraceptive reasons, and their partner was not infecund for non-contraceptive reasons. The standard definition of non-user included women who did not use contraception during the month of the NSFG interview. The refined definition of non-users included women who met the following criteria: non-users of contraception according to standard definition, had sexual intercourse in the past 12 months and during the last month of sexual intercourse were not pregnant and did not use any contraception, and did not expect their next birth within the next 2 years.

Adjusted for all other characteristics shown in the table as well as the following characteristics not shown in the table that were not significantly associated with either definition of contraceptive non-use: work status (working, not working), place of residency (principal city of metropolitan statistical area, other metropolitan statistical area, rural), had a mother who gave birth as a teenager, and religious affiliation as a child (same categories as current religious affiliation).

3/12,071 women were missing birth country.

Excludes refused (0.1%) and don't know (0.1%).

Of the 2844 women defined as standard non-users, there were 799 (27.6%) women who last had sex more than a year before the interview and were removed from the non-users of contraception group because they were not currently sexually active. There were an additional 649 (25.9%) non-users who had sex in the month of the interview; 506 of these women (20.3% of non-users, 4.2% of women at risk of unintended pregnancy overall) did not expect to have a birth in the next 2 years, so they remained non-users of contraception. Of the 1396 (46.5%) women who last had sex 1–12 months prior to the interview, 215 women (7.6% of non-users of contraception, 1.5% of overall) remained non-users because they were not pregnant at last sex (or had never been pregnant), did not use a method at last sex, and did not expect a birth in the next 2 years. These 215 women combined with the 506 women above resulted in 721 (27.8% of non-users, 5.7% of women overall) women who met our refined definition of non-users of contraception.

Among the women who last had sex 1–12 months prior to the interview and were considered standard non-users of contraception (n = 1396), when we looked back to see if they used a contraceptive method in the month of last sex, a large percentage of them reported using a method in the month of last sex, most commonly a coital dependent method like condoms (47.2%) or withdrawal (14.9%). Yet a quarter (24.5%) of women reported using no method in the month of last sex (Table 2).

Table 2.

Contraceptive method used and pregnancy status at last sex between 1 and 12 months prior to the interview month among women classified as non-users of contraception using the standard definitiona (N = 1396)

| Most effective contraceptive method used at month of last sex | Non-users who last had sex between 1 and 12 months prior to the month of interview % (SE) |

|---|---|

| Sterilization | 1.9 (0.5) |

| Long-acting reversible contraception | 0.7 (0.2) |

| Injectable | 1.0 (0.4) |

| Patch/ring | 1.0 (0.3) |

| Pill | 6.6 (1.0) |

| Diaphragm | 0.1 (0.1) |

| Condom | 47.2 (2.0) |

| Withdrawal | 14.9 (1.4) |

| Other less effective | 2.2 (0.6) |

| No method | 24.5 (1.9) |

| Not pregnant at last sex | 77.5 (3.8) |

| Last sex during last pregnancy | 22.5 (3.8) |

All standard non-users reported no contraceptive method use during the month of the interview, by definition. There were an additional 649 women who had sex during the month of the interview and reported no method use who are not shown in this table.

Among the group of standard non-users, the top reasons for not using birth control were “not minding if they got pregnant” (22.6%), “worried about contraceptive side effects” (21.0%), and “not thinking they could get pregnant” (17.6%) (Table 3). When we examined these reasons by when women expected their next child to be born, the top reasons varied by timing of expectation for next birth. For example, “not expecting to have sex” was more commonly reported among women who expected a birth in the next 2–5 years or 5 + years compared with expecting a birth sooner or don't know (p <.05). The response “didn't really mind if they got pregnant” was more common among women expecting a child in the next 2 years as compared to 5 + years or don't know (p <.05). Finally, “could not get a method” was more common among women expecting a child in the next 5 + years compared to the next 2 years or don't know (p <.05).

Table 3.

Main reason for not using birth control among women who are not currently pregnant, had sex in month of interview, are not sterilized nor sterile, and did not use a method in the month of the interview (n = 552) by expected timing of next birth

| Standard non-users of contraception |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main reason for not using birth control | Overalla n = 552 col % (SE) |

Within next 2 years n = 118 col % (SE) |

Refined non-users of contraception |

||

| 2–5 years from now n = 168 col % (SE) |

More than 5 years from now n = 56 col % (SE) |

Neverb n = 234 col % (SE) |

|||

| Do not expect to have sex | 13.8 (1.9) | 7.5 (2.4) | 20.2 (5.3) | 28.0 (5.8) | 10.6 (2.5) |

| Do not think you can get pregnant | 17.6 (2.5) | 12.6 (3.9) | 11.8 (3.9) | 13.0 (6.5)c | 24.1 (4.6) |

| Don't really mind if you get pregnant | 22.6 (2.2) | 41.4 (6.5) | 24.4 (4.7) | 10.0 (5.1)c | 14.8 (3.1) |

| Worried about the side effects of birth control | 21.0 (2.5) | 25.4 (6.8) | 23.1 (5.2) | 15.7 (5.5) | 18.4 (3.4) |

| Male partner does not want you to use a birth control method | 0.7 (0.3)c | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.7 (0.5) c | 0.6 (0.6) c | 1.0 (0.5) c |

| Male partner does not want to use a birth control method | 1.5 (0.7)c | 1.4 (1.2) c | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.5 (0.5) c | 2.6 (1.7) c |

| Could not get a method | 6.0 (1.6) | 0.9 (0.5) c | 9.5 (4.8) | 18.7 (6.7) c | 4.2 (1.4) |

| Not taking, or using, method consistently | 8.3 (1.8) | 6.7 (3.5) c | 8.0 (2.2) | 4.4 (2.3) c | 9.9 (3.5) |

| Refused | 0.4 (0.3)c | 0.2 (0.2) c | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.7 (0.6) c |

| Don't know | 3.8 (1.4) | 0.6 (0.6) c | 1.0 (0.7) c | 6.4 (4.1) c | 6.6 (2.9) |

| Total, row % | 552 (100) | 21.7 (2.4) | 25.3 (2.6) | 7.5 (1.2) | 45.6 (3.3) |

Of 649 eligible respondents, 73 did not provide a main reason for not using birth control, and 24 eligible respondents responded they were actually using a method; these 97 respondents were excluded from this table.

1 “Don't know” and 233 “Nevers”.

Percentage estimate may be unreliable because based on unweighted counts of < 10.

Comparing characteristics of women using our refined definition of contraceptive non-users to other women at risk of unintended pregnancy, contraceptive non-users were more likely to be living at < 200% of the FPL compared to ≥ 400% of the FPL, have public insurance coverage or be uninsured, currently affiliated with the Baptist church vs. no religious affiliation, expect a birth within 2–5 years, and have a parity of one (Table 1). In the fully adjusted model, only expecting a birth within 2–5 years and having parity of one remained significant.

4. Discussion

This is one of the first studies to examine a multitude of characteristics and their associations with contraceptive non-use among reproductive age women at a national level in the US. Although there has been a great deal of focus on trends in contraceptive method use and initiatives to increase contraceptive access to promote method use, there has been very little descriptive information on the characteristics of contraceptive non-users in the US. We found that only 5.7% of women at risk of unintended pregnancy could reliably be considered non-users, once we took into account their expectations for timing of their next birth, as well as method use and pregnancy status at their most recent month of sex. These non-users were more likely to be low-income, have public insurance or be uninsured, affiliated with the Baptist church, expect a birth within 2–5 years, and have a parity of one; however, after adjusting for all other factors, only expecting a birth within 2–5 years and having a parity of one remained significantly associated with our more refined definition of non-use.

We have previously used the NSFG data to assess patterns and trends in contraceptive use in the US and reported that 9.8% of sexually active, low-income women at risk for unintended pregnancy who reported receipt of any contraceptive services in the previous 12 months used no method in the month of the interview in 2013–2015 [15]. That estimate is not as low as our current refined estimate of non-use (5.7%) because in the present analysis we counted contraceptive method(s) use during the month of last sex in the past year as “use” and removed women from the non-user group if they expected a birth in the next 2 years; however, we also included all women at risk of unintended pregnancy (not just low-income women who received contraceptive services in the past year), which would have increased the percentage of non-users had we not applied the “look back” methodology.

Kavanaugh and Jerman (2018) also estimated current contraceptive method use using NSFG data (for years 2006–2015) and reported non-use percentages among all women and women at risk of unintended pregnancy. Among all women the percentages were 37.8% (2006–2010), 38.3% (2011–2013), and 38.6% (2013–2015) and among women at risk of an unintended pregnancy the percentages were 11.0% (2006–2010), 10.0% (2011–2013), and 10.5% (2013–2015). The percentages among women at risk of an unintended pregnancy were very similar to our previous NSFG estimate of 9.8%; however, Kavanaugh and Jerman's denominator did not require receipt of any contraceptive services in the previous 12 months, which likely led to their greater estimate of non-use. This demonstrates that the percentage estimates for non-users depends on how the numerator and “at risk” denominator are defined, which is inconsistent across studies and can lead to different estimates of contraceptive non-use even with the same data source.

Pazol et al. (2015) also looked at contraceptive non-use among women at risk for unintended pregnancy using earlier NSFG data (2006–2010) and identified 13% of women as contraceptive non-users [13]. Women were assessed for unintended pregnancy risk each month for the 12 months prior to their interview and defined as “at risk” for each month they had sexual intercourse and at the time were not pregnant or seeking pregnancy, sterile or had a partner who was sterile, including a tubal sterilizing operation or a vasectomy. Non-users were defined as women who did not use contraception during any month they were at risk. Women ages 15–19 (4.5% were non-users) and women ages 20–24 (9.2% were non-users) were less likely to be non-users than women ages 25–34 (13.9% were non-users). Our definition of non-users identified 4.6% of women ages 15–19 and 5.8% of women ages 20–44 as non-users; these estimates were similar to Pazol's estimate for teenagers but lower than her estimates for older women. Pazol et al. also found that having public versus private insurance was associated with increased odds of non-use among women in the youngest and oldest age groups, and intending to have children in the future was associated with contraceptive non-use in older women, which agreed with what we found.

Mosher et al. (2015) combined the 2002 and 2006–2010 NSFG data to look at contraceptive non-use among women at risk of unintended pregnancy [14]. They defined women at risk of unintended pregnancy as individuals who were sexually active and not using contraception during the month of the interview and found 16.5% of women to be non-users, which is close to our percentage of standard non-users. They found cohabitating women had higher odds of nonuse than married women, where we found these two groups to have similar non-use. They also found non-use was more common among women with higher education, where we did not find differences by education (data not shown, but ranged from 17.6% for less than high school degree to 20.4% for some college and prevalence ratios were not statistically significant). Mosher et al. looked at reasons for not using contraception among women who had a birth resulting from an unintended pregnancy in the 3 years before the survey and were not using any contraception at the time of the pregnancy. Similar to our study, they found the top reasons for contraceptive non-use were not thinking they could get pregnant, did not expect to have sex, and did not really mind if they got pregnant.

Although our findings regarding reasons for contraceptive non-use by future birth timing pertain to the standard non-users group rather than our refined definition, our findings are novel and warrant further consideration. One of the top reasons for contraceptive non-use among women who expected their next birth within the next 2 years, or 2–5 years was not really minding if they got pregnant. Some of these non-users of contraception could benefit from preconception care, including recommendations on supplementation with prenatal vitamins containing folic acid [25]. In an analysis of women who had a recent live birth in Maryland using the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System data, only 31.5% reported daily folic acid use in the month before they became pregnant [26]. The most common reasons for not taking folic acid were “not planning pregnancy” and “didn't think needed to take.” By having a conversation about individual's short- and long-term reproductive goals, medical staff can appropriately identify women that would benefit from starting to think about their pre-pregnancy health [27]. Women who want a birth within 2–5 years would also likely benefit from easier contraceptive access, such as over-the-counter oral contraception and other hormonal methods, as well as self-administration of injectable contraceptives [28].

The top reason for not using contraception among women who wanted their next birth more than 5 years from now was they did not expect to have sex. Women who are not regularly having sex may not desire to use a semi-permanent contraceptive method, such as LARCs, or a method that requires daily or monthly maintenance. Women not regularly having sex may also benefit from having ready access to coital dependent methods such as barrier methods (condoms) and/or a prescription for emergency contraception that they can use during or after a spontaneous sexual encounter [29,30].

Being worried about the side effects of birth control was one of the top concerns for every category of future birth timing, which may indicate that women are not receiving adequate client-centered counseling. High-quality family planning counseling should include discussing patient's attitudes towards side effects [31], and providing information about side effects and benefits for the broad range of contraceptive methods available. Studies have shown that provision of information about side effects is associated with improved outcomes, including user satisfaction and continuation rates [32,33]. It is also important to note that nearly 10% of women expecting their next child to be born in the next 2–5 years and nearly 20% of women expecting their next birth in 5 or more years reported not being able to get a contraceptive method. Strategies like prescribing a 1-year supply of oral contraceptive pills compared to a 1- to 3-month supply [34] and making hormonal methods of contraception available over the counter [35] may help women be able to obtain a method more easily and be able to switch methods more easily if they have concerns about the side effects of their contraceptive method.

Non-use of contraception in the U.S. varies by the characteristics and timing of birth expectations of women, and depends on the definitions of contraceptive use and population at risk for unintended pregnancy. Our findings suggest that barriers to use might vary in a similar fashion. However, when non-users are examined more closely, expecting a birth within 2–5 years and being parous remain associated with non-use after adjusting for all other factors. Therefore, it is important for women to have access to a broad array of contraception methods, including coital dependent methods and adequate pre-conception counseling if they want a pregnancy in the near future, but not immediately.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgements

Katherine Ahrens was supported by a faculty development award from the Maine Economic Improvement Fund.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Kost K., Zolna M. Challenging unintended pregnancy as an indicator of reproductive autonomy: a response. Contraception. 2019;100(1):5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2019.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aiken A.R., Borrero S., Callegari L.S., Dehlendorf C. Rethinking the pregnancy planning paradigm: unintended conceptions or unrepresentative concepts? Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2016;48(3):147–151. doi: 10.1363/48e10316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020 Objectives: Family Planning. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=13. Accessed October 17, 2013.

- 4.Potter J.E., Stevenson A.J., Coleman-Minahan K. Challenging unintended pregnancy as an indicator of reproductive autonomy. Contraception. 2019;100(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2019.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall J.A., Benton L., Copas A., Stephenson J. Pregnancy intention and pregnancy outcome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Maternal Child Health J. 2017;21(3):670–704. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-2237-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster D.G., Biggs M.A., Raifman S., Gipson J., Kimport K., Rocca C.H. Comparison of health, development, maternal bonding, and poverty among children born after denial of abortion vs after pregnancies subsequent to an abortion. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(11):1053–1060. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gipson J.D., Koenig M.A., Hindin M.J. The effects of unintended pregnancy on infant, child, and parental health: a review of the literature. Stud Fam Plann. 2008;39(1):18–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peipert J.F., Madden T., Allsworth J.E., Secura G.M. Preventing unintended pregnancies by providing no-cost contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(6):1291–1297. doi: 10.1097/aog.0b013e318273eb56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldthwaite L.M., Duca L., Johnson R.K., Ostendorf D., Sheeder J. Adverse birth outcomes in Colorado: assessing the impact of a statewide initiative to prevent unintended pregnancy. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):e60–e66. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karpilow QC, Thomas AT. Reassessing the importance of long-acting contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(2):148.e141–148.e114. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Thomas A., Karpilow Q. The intensive and extensive margins of contraceptive use: comparing the effects of method choice and method initiation. Contraception. 2016;94(2):160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kavanaugh M.L., Jerman J. Contraceptive method use in the United States: trends and characteristics between 2008, 2012 and 2014. Contraception. 2018;97(1):14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pazol K, Whiteman MK, Folger SG, Kourtis AP, Marchbanks PA, Jamieson DJ. Sporadic contraceptive use and nonuse: age-specific prevalence and associated factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(3):324.e321–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Mosher W., Jones J., Abma J. Nonuse of contraception among women at risk of unintended pregnancy in the United States. Contraception. 2015;92(2):170–176. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fowler C.I., Ahrens K.A., Decker E. Patterns and trends in contraceptive use among women attending title X clinics and a national sample of low-income women. Contraception: X. 2019;1:100004. doi: 10.1016/j.conx.2019.100004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National survey of family growth. Questionnaires, datasets and related documentation. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg/nsfg_questionnaires.htm Updated December 26, 2018. Accessed May, 2020.

- 17.Healthy People 2020 Family Planning Objectives. FP-16: Increase the percentage of women aged 15 to 44 years that adopt or continue use of the most effective or moderately effective methods of contraception Acccessed 2-6-2017 at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/family-planning/objectives.

- 18.Gavin L., Frederiksen B., Robbins C., Pazol K., Moskosky S. New clinical performance measures for contraceptive care: their importance to healthcare quality. Contraception. 2017;96(3):149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howie P.W., McNeilly A.S., Houston M.J., Cook A., Boyle H. Fertility after childbirth: post-partum ovulation and menstruation in bottle and breast feeding mothers. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1982;17(4):323–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1982.tb01597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Health People 2020. Maternal, Infant, Child Health Objective 16.6: Postpartum contraception. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/maternal-infant-and-child-health/objectives. Accessed.

- 21.Daniels K, Ahrens K, Pazol K. Refining Assessment of Contraceptive Use in the Past Year in Relation to Risk of Unintended Pregnancy. Contraception. 2020;S0010–7824(20):30112–30118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception. 2011;83(5):397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frederiksen B.N., Ahrens K.A., Moskosky S., Gavin L. Does contraceptive use in the United States meet global goals? Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2017;49(4):197–205. doi: 10.1363/psrh.12042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.NSFG Webdoc: online codebook documentation. Universe for "WHYNOUSING1": EH-2c. 2015-2017. https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsradmin/nsfg/variable/1083742?studyNumber=10001&vg=14070

- 25.Bibbins-Domingo K., Grossman D.C., Curry S.J. Folic acid supplementation for the prevention of neural tube defects: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2017;317(2):183–189. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.19438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bixenstine P.J., Cheng T.L., Cheng D., Connor K.A., Mistry K.B. Association between preconception counseling and folic acid supplementation before pregnancy and reasons for non-use. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(9):1974–1984. doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1705-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson K, Posner SF, Biermann J, et al. Recommendations to improve preconception health and health care--United States. A report of the CDC/ATSDR Preconception Care Work Group and the Select Panel on Preconception Care. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(Rr-6):1–23. [PubMed]

- 28.Lerma K., Goldthwaite L.M. Injectable contraception: emerging evidence on subcutaneous self-administration. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2019;31(6):464–470. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gavin L, Moskosky S, Carter M, et al. Providing quality family planning services: Recommendations of CDC and the US Office of Population Affairs. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63(Rr-04):1–54. [PubMed]

- 30.Curtis K.M., Jatlaoui T.C., Tepper N.K. U.S. selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(4):1–66. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6504a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dehlendorf C., Krajewski C., Borrero S. Contraceptive counseling: best practices to ensure quality communication and enable effective contraceptive use. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2014;57(4):659–673. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Backman T., Huhtala S., Luoto R., Tuominen J., Rauramo I., Koskenvuo M. Advance information improves user satisfaction with the levonorgestrel intrauterine system. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99(4):608–613. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01764-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cetina T.E.C.D., Canto P., Luna M.O. Effect of counseling to improve compliance in Mexican women receiving depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate. Contraception. 2001;63:143. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(01)00181-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grindlay K., Grossman D. Interest in over-the-counter access to a progestin-only pill among women in the United States. Womens Health Issues. 2018;28(2):144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Potter J.E., McKinnon S., Hopkins K. Continuation of prescribed compared with over-the-counter oral contraceptives. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(3):551–557. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820afc46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]