Abstract

Arterial hypertension is one of the main contributors to cardiovascular diseases, including stroke, heart failure, and coronary heart disease. Salt plays a major role in the regulation of blood pressure and is one of the most critical factors for hypertension and stroke. At the individual level, effective salt reduction is difficult to achieve and available methods for managing sodium balance are lacking for many patients. As part of the ingested food, salt is absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract by the sodium proton exchanger subtype 3 (NHE3 also known as Slc9a3), influencing extracellular fluid volume and blood pressure.

In this review, we discuss the beneficial effects of pharmacological inhibition of NHE3-mediated sodium absorption in the gut and focus on the effect on blood pressure and end-organ damage.

Keywords: Hypertension, Blood pressure, Salt, Sodium-proton-exchanger, Gut

1. Introduction

Arterial hypertension is the leading cause of cardiovascular diseases and predominantly linked to stroke, heart failure and coronary heart disease [1]. There is a considerable body of evidence associating higher salt intake with higher blood pressure and increased cardiovascular risk, namely hypertension and stroke [2], [3], [4], [5]. Moreover, excess sodium intake impairs beneficial effects of different antihypertensive drugs, including blockers of the renin–angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), one of the key-point pharmacological interventions in cardiovascular and renal medicine [6].

In many countries, the usual sodium intake is between 3.5 and 5.5 g per day, which equals a salt consumption of 9–12 g/day [7]. A 3 g/day reduction in salt intake decreases on average systolic and diastolic pressure by 5 and 2 mmHg, respectively. The effect is more pronounced in hypertensive, black or elderly people and in individuals with diabetes, metabolic syndrome or chronic kidney disease (CKD). Here, salt restriction does not only lower blood pressure but may also reduce the number and doses of antihypertensive drugs [8]. Thus guidelines recommend a maximum daily intake of 5 g of salt (about 2 g (46 mmol) of sodium per day) for the general population [7].

Given the dilemma of a low-salt diet, which is notoriously difficult to achieve but yet bears fundamental benefits on cardiovascular health, this review discusses intestinal pharmacological sodium uptake inhibition as a novel cardiovascular treatment strategy.

1.1. Sodium homeostasis

Sodium homeostasis is closely linked to fluid balancing and blood pressure regulation. Aside from the kidney, muscle, skin and brain, the gut, as the organ to absorb ingested sodium, has been suggested to be involved in sodium homeostasis [9], [10], [11].

In the kidney, the renal proximal tubule is responsible for 65–70% of filtered sodium and water reabsorption under normal conditions [12]. Several studies have shown that human essential hypertension is associated with increased sodium transport in the renal proximal tubule [13]. The inappropriate sodium retention in hypertension results from an enhanced renal sodium transport per se, as well as a failure to respond appropriately to signals that decrease renal sodium transport in the face of increased sodium intake.

In addition to the kidney, the gastrointestinal tract plays along in maintaining salt and fluid balance [14]. Humans reabsorb about 7–9 L of gastrointestinal fluid a day. Most of the electrolytes and fluids are absorbed by the small (>95%) and large (>4%) intestines. The intestinal absorption of fluid by gastrointestinal epithelial cells, mainly located from the small intestine to the distal colon, occurs via active transport of sodium. Experiments on Dahl salt-sensitive and salt-resistant rats, which represent a model of salt-sensitive hypertension, have shown no difference in intestinal sodium absorption between hypertensive and healthy controls [15]. Thus, an augmented ability of the intestines to absorb sodium does not critically participate in the pathogenesis of most cases of hypertension.

1.2. Sodium-proton-exchangers in the gut and the gastrointestinal-renal axis

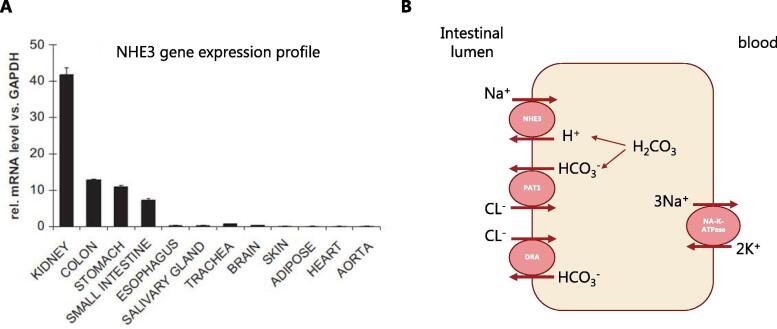

Intestinal salt (NaCl) and water absorption in the gut are largely driven by the sodium-dependent cotransporters and sodium reuptake, including the sodium-proton-exchangers NHE2, NHE3, and NHE8, of which NHE3 (SLC9A3) is of main importance [16]. NHE3 is highly expressed at the apical membrane of the small intestine and colon [17], [18] and NHE3 knock-out mice are mainly characterized by defects in intestinal sodium absorption [19], demonstrating that NHE3 is the major contributor to intestinal sodium uptake (Fig. 1). NHE3 exchanges sodium (Na+) for protons (H+), while the protons are provided by water and carbon dioxide, which is transformed to H2CO3 by the enzyme carbonic anhydrase. The initiator, which allows sodium to cross the cell border due to creating an electrochemical gradient is the basolateral Na-K-ATPase. Moreover, putative-anion-transporter-1 (PAT1) and down-regulated-in-adenoma (DRA) are both transporters involved in the absorption of chloride (Cl−) [20].

Fig. 1.

NHE3 gene expression profile (A) and mechanism of sodium absorption in the small intestine (B). Sodium hydrogen exchanger 3 (NHE3), putative anion transporter 1 (PAT1), down regulated in adenoma (DRA) [18], [20].

Not only are the gut and the kidneys both involved in maintaining sodium and fluid balance and thereby blood pressure, there is even evidence suggesting a hormonal communication between the two organs [21]. The gastrointestinal tract screens the food via taste receptors and sensors for electrolytes (eg. sodium, potassium, phosphate) [22]. Gastrointestinal tract–derived hormones and peptides have been shown to regulate autocrine function of renal hormones, including gastrin and glucagon-like-Peptide-1, affecting renal function and mediating sodium excretion [23]. This suggests the existence of a gastrointestinal–renal axis regulating blood pressure [21].

1.3. Salt intake and gut microbiome

The gut is the habitat of a large variety of bacteria, fungi, viruses and protozoa. Profound research, demonstrated that the gut microbiome contributes fundamentally to energy homeostasis, metabolism, immunology, cardiovascular health and even neurobehavioral development [24], [25]. Therefore, malnutrition, like excess in salt intake, may have wide ranging consequences.

In mice, high salt intake affects the gut microbiome, particularly by depleting Lactobacillus murinus [26]. Consequently, treatment of mice with Lactobacillus murinus prevented salt-induced aggravation of actively induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and salt-sensitive hypertension by modulating T-helper 17 (TH17) cells. In line with these findings, a moderate high-salt challenge in a pilot study in humans reduced intestinal survival of Lactobacillus, increased TH17 cells and increased blood pressure [26]. Moreover, high dietary sodium consumption also depletes bacteria from the order Clostridiales [26], which together with Lactobacillus species, are crucial for the secondary bile acid metabolism [10]. Deoxycholic and lithocholic acids are ligands for G-protein-coupled bile acid receptor 1, expressed along the gastrointestinal tract, which upon activation increase expression of cystathionine γ-lyase, an essential enzyme for generation of the vasodilator hydrogen sulfide [10]. This generally stresses the importance of the gut microbiome for cardiovascular physiology. Moreover though, microbiome composition is easily affected by changes of intestinal pH, which is modulated amongst others by intestinal NHE3 [27].

1.4. Intestinal inhibition of sodium uptake: a new antihypertensive concept?

Effective salt reduction is a recommended lifestyle change in order to treat hypertension, but at an individual level hard to achieve. Available methods for managing sodium and fluid balance, like a substantial and radical change in diet is not a possibility for many patients. Large renal trials demonstrated, that salt-ingestion of patients was clearly far above the recommended 5–6 g/day [6]. A novel treatment target in that area evolved recently: non-absorbable intestinal NHE3-inhibitors. Those inhibitors are meant to reduce intestinal sodium uptake and help with the otherwise hardly achievable lifestyle change of a low salt-diet. NHE3-inhibitors have special implications for patients with hypertension and heart failure. Especially, in heart failure patients, treatment of fluid overload by diuretics becomes rapidly inefficient as patients develop resistance to diuretics and/or develop concomitant renal failure and hypokalemia [28].

2. Pharmacological inhibition of intestinal sodium absorption

Generally, drugs are designed to be rapidly absorbed to achieve therapeutic plasma levels, and then be eliminated by multiple pathways. In contrast, oral administration of non-absorbable drugs is designed to minimize systemic exposure and to exert their therapeutic effects locally in the gastrointestinal tract. Due to these differences, the development of non-absorbable drugs is directed by its own set of pharmaceutical design principles. Non-absorbable and therefore non-systemic drugs display less off-target systemic effects and thereby less drug-drug interaction, toxicity, or side-effects (reviewed in [29]).

2.1. Non-absorbable NHE3-inhibitors

Oral administration of highly selective non-absorbable NHE3-inhibitors reduces the intestinal water and sodium absorption in the gut [18], [30]. These inhibitors specifically target the membrane-bound protein-fraction of the NHE3, expressed on the cell surface of the gut epithelia. Their non-systemic profile is characterized by drug metabolism pharmacokinetic methods, tracking parent drug and metabolites in blood, urine, and feces. Additionally, absorption experiments in vessel-perfused in situ preparations of the small intestine are helpful screening-tools [18].

2.1.1. SAR218034xxx

SAR218034 (SAR, (1-(β-D-glucopyranosyl)-3-{3-[(4S)-6,8-dichloro-2-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisochinolin-4-yl]phenyl}urea) is a novel, non-absorbable NHE3-inhibitor [18]. SAR demonstrated high potency and selectivity in rat studies and has approximately equivalent inhibitor action on rat and human NHE3. SAR did not interact with the physiological functions of other human NHE-isoforms, like NHE5 or NHE1. Amino acid sequence comparison revealed high homologies between orthologous NHE proteins in rats and humans ranging from 90% to 98% identity [18].

Bioavailability of SAR is very low as demonstrated in a permeability assay (Caco-2 in TC7 cells) and in oral bioavailability studies. An oral dose of 1 mg/kg as used in preclinical study corresponds to a maximal plasma concentration of ≈1 nmol/L. This is 13-fold below the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) for rat NHE3. Therefore, SAR is a functional non-absorbable compound. Additionally, in perfused in situ preparations of the small intestine, intraluminal SAR application increased sodium concentration and volume of the perfusate. This underlines the local effect of SAR at the luminal intestinal membrane.

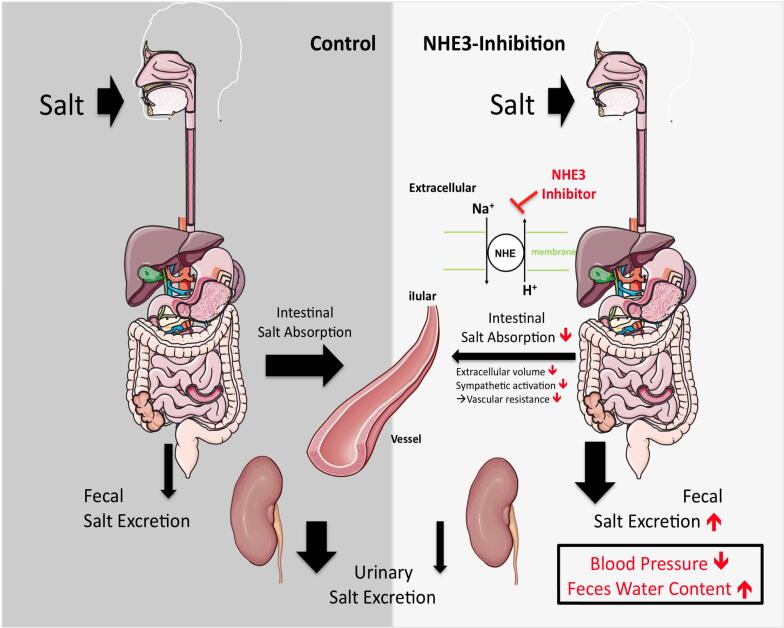

In both lean and obese spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR and SHR-ob), selective pharmacological inhibition of the NHE3 exchanger in the gut by SAR reduced intestinal sodium absorption and increased renal sodium reabsorption [18] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Effect of intestinal NHE3-inhibition on intestinal salt absorption and subsequent fecal and urinary salt excretion. Impact on blood pressure and feces water content.

2.1.2. Tenapanor

Effects comparable to SAR were also found by another selective NHE3-inhibitor, tenapanor (RDX5791,AZD1722, N,N’-(10,17-dioxo-3,6,21,24-tetraoxa-9,11,16,18-tetraazahexacosane-1,26-diyl)bis([(4S)-6,8-dichloro-2-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetra hydroisoquinolin-4-yl]benzenesulfonamide)) [31]. Tenapanor is up to now the only NHE3 inhibitor that has been evaluated in humans. After oral administration of tenapanor in rats and humans, maximal plasma concentrations were less than 1 ng/ml due to limited permeability across cell monolayers. Non-absorbance of tenapanor was also confirmed by mass balance and quantitative whole-body autoradiography studies with 14C-tenapanor in rats [30]. The pharmacological effects of tenapanor evaluated in rats and healthy human volunteers were found to be comparable and include reduced urinary sodium and increased fecal sodium, activities consistent with reduced intestinal sodium absorption and increased sodium reabsorption in the kidney [30] (Fig. 2). These data indicate that NHE3 blockade shifts sodium from urinary to fecal excretion. Moreover, in humans the response to tenapanor has been shown to be both dose-dependent and reversible [32], [33].

In addition to increased stool sodium excretion, tenapanor has also been found to increase the excretion of stool phosphate and as a result reduced serum phosphate concentrations which has beneficial implications for patients with CKD-related hyperphosphatemia [34], [35], [36]. In a randomized phase 3 trial in patients with CKD, tenapanor treatment for 8 weeks could reduce elevated serum phosphate levels while receiving maintenance hemodialysis [36]. Tenapanor however could in another CKD cohort not change interdialytic weigh gain despite of increased sodium stool content [37].

As tenapanor acts locally in the gastrointestinal tract it could potentially cause drug-drug interactions with drugs metabolized by the cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYPs) found in cells of the gut wall. Out of several CYPs tested in vitro, tenapanor was found to have the most potent inhibitory effect on CYP3A4. However, clinical studies have found that the effect on CYP3A4 is not clinically relevant as the pharmacokinetic characteristics of midazolam, a CYP3A4 metabolized drug, are comparable whether co-administrated with tenapanor or not. Therefore, tenapanor can be co-administrated with drugs metabolized by CYP3A4 without any expected clinically relevant drug-drug interactions [38].

Due to the low systematic availability tenapanor is in general reported to be well tolerated in humans with only mild to moderate adverse GI adverse effects such as abdominal pain and diarrhea [32], [33]. Tenapanor was evaluated and approved for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Moreover, tenapanor is being investigated for treatment of hyperphosphatemia in patients with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT03427125).

3. Antihypertensive effects of pharmacological intestinal NHE3-inhibition

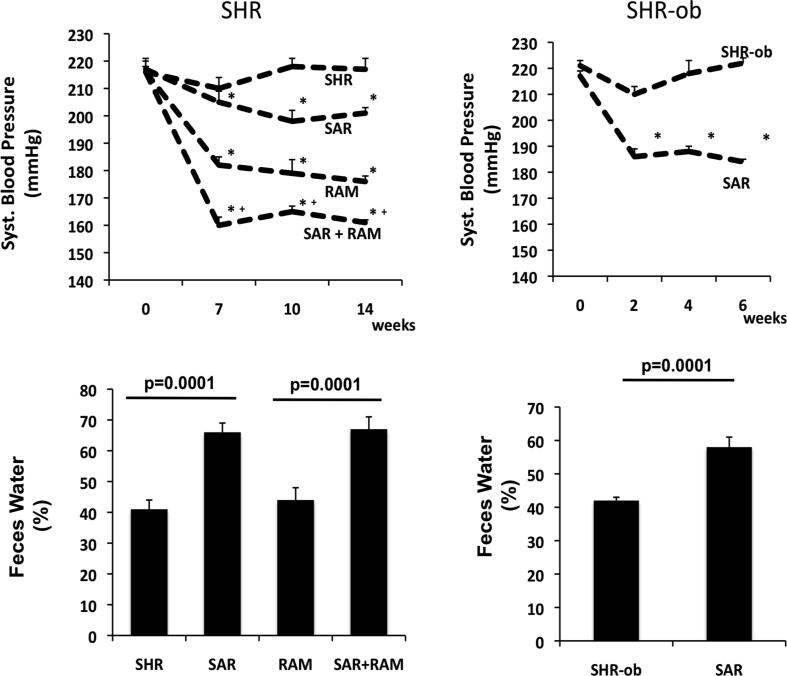

Reduced intestinal NHE3-mediated sodium absorption in SAR- [18] or tenapanor-treated animals [22] was associated with decreased blood pressure in SHR and obese SHR rats, which are models for spontaneous hypertension, as well as in 5/6 nephrectomized rats, a rat model for renal loss [18], [30]. Additionally, SAR or tenapanor administered in combination with an ACE-inhibitor, resulted in an additive reduction in blood pressure (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effect of NHE3-inhibitor SAR on systolic blood pressure (top) and feces water content (bottom) in SHR (left) and SHR-ob (right). In SHR (left) SAR was combined with the ACE-inhibitor ramipril (RAM) [18].

Underlying mechanisms of the NHE3-inhibition associated antihypertensive effect include a reduction in extracellular volume due to the laxative effect, potential changes in intestinal microbiome composition and a decreased sympathetic activation [18], [39] (7.; Fig. 2). Interestingly, not only does intestinal salt absorption influence sympathetic activation, also Angiotensin II itself, as a conventional result of a sympathetic activation, showed regulative effects on intestinal epithelial NHE3 expression in cells, indicating a close relationship between intestinal salt absorption and sympathetic drive [40].

These results underline the importance of NHE3 regulation in hypertension, but further randomized clinical trials of NHE3-inhibitors in hypertensive patients are warranted.

Antihypertensive effects of intestinal NHE3-inhibiton could be of special interest in CKD-patients, in which conventional medical treatment strategies which often have renal targets lack efficiency. Even though intestinal NHE3-inhibition increased sodium stool content and decreased phosphate uptake in CKD-patients under hemodialysis, blood pressure was not reported to be affected by the treatment [36], [37]. Nevertheless, blood pressure remains to be a difficult parameter to assess under hemodialysis and future clinical studies are warranted to investigate antihypertensive effects also in such special cohorts.

4. Laxative effects of pharmacological intestinal NHE3-inhibition

Increased sodium concentration in the feces in NHE3-inhibitor treated animals binds water in the gut. A stool water content of 60–70% in SAR-treated animals resulted in a softer but still solid stool consistency and did not cause diarrhea [18]. Consistently, tenapanor administration to normal rats loosened stool form [30]. Additionally, in humans tenapanor administrations softens stool consistency, increases stool frequency and weight and the frequency of bowl movements [32], [33]. In addition to these effects, patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation also reported relief of abdominal symptoms such as bloating, cramping and discomfort [41]. However, in humans, the most common side-effect of non-absorbable NHE3-inhibitors remains to be diarrhea [42].

5. Prevention of hypertensive cardiac and renal end-organ damage

To further validate its therapeutic use in the setting of hypertension in CKD, tenapanor was tested in 5/6 nephrectomized rats fed a high sodium diet. NHE3-inhibition reduced blood pressure, normalized albuminuria, and delayed heart and kidney damage [30]. Comparable effects were also shown for the NHE3-inhibitor SAR. Stable blood pressure reduction in NHE3-inhibitor treated animals was associated with an attenuation of cardiac and renal end-organ damage [43]. Furthermore, SAR also prevented atrial structural remodeling and reduced atrial arrhythmia susceptibility in a rat model for hypertension and metabolic syndrome [44], [45].

6. NHE3-inhibitors and heart failure

Up to now, salidiuretics are effectively used to improve congestion in congestive heart failure, but their use is often limited by constipation and renal failure [28]. In CKD, the ability of the kidneys to excrete potassium decreases proportionally to the loss of glomerular filtration. Besides this, diuretic treatment and associated dehydration provokes constipation [46]. Increase in intestinal water excretion is an alternative promising strategy to manage water load in heart failure. The modulation of intestinal sodium uptake by non-absorbable NHE3-inhibitors instead of modulation of sodium excretion in the kidney by diuretics did not result in the development of hypokalemia, diabetic condition or impaired lipid status [18]. Noteworthy, diuretics may affect intestinal NHE3-exchanger and result in its further upregulation [47]. This phenomenon may be particularly relevant in congestive heart failure patients receiving high-diuretic doses. NHE3-inhibitors may however prevent the functional effect of this increased NHE3 expression.

Although a direct comparison between the net effects on the sodium balance of the currently used diuretics and intestinal NHE3-inhibiting compounds are not available, diuretics might also induce sodium loss via the stool by the blockage of sodium transporters and exchangers, including NHE3, which are present in both the kidney and the intestines [48], [49]. However, the relative contribution of fecal sodium excretion to overall sodium excretion during oral or intravenous diuretic treatment remains uncertain. Interestingly, with very potent and orally highly bioavailable NHE3 inhibitors, no significant influence on renal function, for example, natriuresis could be observed previously (unpublished own data). This is the reason that no renal-specific NHE3 inhibitor was developed for clinical use.

7. Potential effect of NHE3-inhibition on microbiome composition

Changes in gut microbiome composition can either have beneficial or detrimental consequences for human physiology. Therefore, modulation of the gastrointestinal intraluminal milieu by selective pharmacological inhibition of intestinal absorption of dietary ions might offer an interesting approach to control the composition of the gut microbiome [50], [51].

Recent studies have demonstrated that NHE3-deficiency, resulting in alkaline gut luminal microenvironment, may alter the bacterial flora of the brush border in a way that is deleterious to both abundance of Firmicutes (particularly families Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae) as well as butyrate production, shifting instead to a peak production of propionate and an expansion of Bacteroidetes [27], [52]. Propionate is the strongest among short chain fatty acids (SCFA) ligand for both G protein coupled receptors 41 and 43 [53], reported to be associated with vasodilation and blood pressure reduction [54], [55]. Moreover, propionate stimulated the secretion of both peptide YY and glucagon-like peptide 1, which reduce NHE3 expression enhancing negative feedback loop [56]. In the intestine, continuous stimulation of intestinal T cells by excessive propionate leads to the spontaneous interleukin-10 production [57], which counteracts both the pressoric activity of angiotensin II as well as vascular dysfunction associated with hypertension [58]. Recently, propionate administered in drinking water to mice infused with angiotensin II reduced systolic and diastolic blood pressure, systemic inflammation, cardiac damage, and improved vascular function [59]. SCFA, especially butyrate, are positive regulators of NHE3 expression and activity [27]. Therefore, reduction in butyrate levels promote decreased activity of NHE3, which sustains alkaline mucosal milieu to maintain a competitive advantage to alkaliphilic bacteria.

Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae have been identified as the most metabolically active bacteria of the human microbiota and play a dominant role in the trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) production [60]. Several studies suggest an existence of a positive feedback mechanism between TMAO and NHE3 expression [55], [61] and found serum TMAO to be associated with chronic upregulation of blood pressure via prolonging the hypertensive effect of angiotensin II [62]. Hence, reduction in aforementioned bacteria species caused by NHE3-deficiency could have positive impact on blood pressure.

One exceptional Firmicutes is Clostridium difficile, which is adapted to replicate optimally at a slightly higher pH than other Clostridia species. Together with other enteropathogenic bacteria C. difficile inhibits intestinal NHE3 expression and function lowering blood pressure [63], [64]. This effect is enhanced by reduction in commensal Lactobacillus acidophilus, caused by alkaline microenvironment, that upregulates intestinal NHE3 function under conditions of reduced pH [65].

While these results indicate positive bacterial composition outcomes with NHE3 inhibition, other research reports that NHE3 deficiency induces irritable bowel disease-like symptoms, gut dysbiosis, and an inflammatory immune system response [66]. Hence, it still remains unclear whether NHE3 inhibition is a viable therapeutic intervention for those with hypertension.

Further studies are needed to investigate the feasibility and efficacy of altering the gut microbiome composition by oral treatment with non-absorbable drugs specifically targeting ion transporters such as NHE3 in the gut.

8. Conclusions

Pharmacological inhibition of intestinal NHE3-mediated sodium absorption is a novel alternative treatment strategy to reduce sodium and water load by selective NHE3-inhibition in the gut. Selective inhibition of NHE3-mediated sodium absorption in the gut has the potential to reduce high blood pressure and cardiac end-organ damage and can be safely combined with ACE inhibitor treatment. Intestinal NHE3-inhibition may provide an attractive option to clinicians managing sodium-fluid balance and hypertension, particularly in patients with preexisting kidney failure. The real potential of the NHE3-inhibitor is to help accomplish a truly low-salt intake from the gut, since it is notoriously difficult to sufficiently reduce salt in the human diet. Whether gastrointestinal NHE3-inhibition also results in a modulation of gut microbiome composition requires further investigation.

References

- 1.Ezzati M., Lopez A.D., Rodgers A., Vander Hoorn S., Murray C.J., G. Comparative Risk Assessment Collaborating Selected major risk factors and global and regional burden of disease. Lancet. 2002;360(9343):1347–1360. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sacks F.M., Svetkey L.P., Vollmer W.M., Appel L.J., Bray G.A., Harsha D., Obarzanek E., Conlin P.R., Miller E.R., 3rd, Simons-Morton D.G., Karanja N., Lin P.H., D.A.-S.C.R. Group Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. DASH-Sodium Collaborative Research Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;344(1):3–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101043440101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reuter S., Bussemaker E., Hausberg M., Pavenstadt H., Hillebrand U. Effect of excessive salt intake: role of plasma sodium. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2009;11(2):91–97. doi: 10.1007/s11906-009-0018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meneton P., Jeunemaitre X., de Wardener H.E., MacGregor G.A. Links between dietary salt intake, renal salt handling, blood pressure, and cardiovascular diseases. Physiol. Rev. 2005;85(2):679–715. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00056.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mishima R.S., Hohl M., Linz B., Sanders P., Linz D. Too fatty, too salty, too western. Hypertension. 2018;72(5):1078–1080. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lambers Heerspink H.J., Holtkamp F.A., Parving H.H., Navis G.J., Lewis J.B., Ritz E., de Graeff P.A., de Zeeuw D. Moderation of dietary sodium potentiates the renal and cardiovascular protective effects of angiotensin receptor blockers. Kidney Int. 2012;82(3):330–337. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams B., Mancia G., Spiering W., Agabiti-Rosei E., Azizi M., Burnier M., Clement D.L., Coca A., de Simone G., Dominiczak A., Kahan T., Mahfoud F., Redon J., Ruilope L., Zanchetti A., Kerins M., Kjeldsen S.E., Kreutz R., Laurent S., Lip G.Y.H., McManus R., Narkiewicz K., Ruschitzka F., Schmieder R.E., Shlyakhto E., Tsioufis C., Aboyans V., Desormais I., E.S.D. Group 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) Eur. Heart J. 2018;39(33):3021–3104. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickinson H.O., Mason J.M., Nicolson D.J., Campbell F., Beyer F.R., Cook J.V., Williams B., Ford G.A. Lifestyle interventions to reduce raised blood pressure: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J. Hypertens. 2006;24(2):215–233. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000199800.72563.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herrera M., Coffman T.M. The kidney and hypertension: novel insights from transgenic models. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2012;21(2):171–178. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3283503068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smiljanec K., Lennon S.L. Sodium, hypertension, and the gut: does the gut microbiota go salty? Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2019;317(6):H1173–H1182. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00312.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Titze J. Sodium balance is not just a renal affair. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2014;23(2):101–105. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000441151.55320.c3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wadei H.M., Textor S.C. The role of the kidney in regulating arterial blood pressure. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2012;8(10):602–609. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horita S., Seki G., Yamada H., Suzuki M., Koike K., Fujita T. Roles of renal proximal tubule transport in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Curr. Hypertens. Rev. 2013;9(2):148–155. doi: 10.2174/15734021113099990009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zachos N.C., Tse M., Donowitz M. Molecular physiology of intestinal Na+/H+ exchange. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2005;67:411–443. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.031103.153004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pacha J. Sodium balance and jejunal ion and water absorption in Dahl salt-sensitive and salt-resistant rats. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 1998;25(3–4):220–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1998.t01-9-.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jia Y., Jia G. Role of intestinal Na(+)/H(+) exchanger inhibition in the prevention of cardiovascular and kidney disease. Ann. Transl. Med. 2015;3(7):91. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.02.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Broere N., Chen M., Cinar A., Singh A.K., Hillesheim J., Riederer B., Lunnemann M., Rottinghaus I., Krabbenhoft A., Engelhardt R., Rausch B., Weinman E.J., Donowitz M., Hubbard A., Kocher O., de Jonge H.R., Hogema B.M., Seidler U. Defective jejunal and colonic salt absorption and alteredNa(+)/H (+) exchanger 3 (NHE3) activity in NHE regulatory factor 1 (NHERF1) adaptor protein-deficient mice. Pflugers Arch. 2009;457(5):1079–1091. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0579-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linz D., Wirth K., Linz W., Heuer H.O., Frick W., Hofmeister A., Heinelt U., Arndt P., Schwahn U., Bohm M., Ruetten H. Antihypertensive and laxative effects by pharmacological inhibition of sodium-proton-exchanger subtype 3-mediated sodium absorption in the gut. Hypertension. 2012;60(6):1560–1567. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.201590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schultheis P.J., Clarke L.L., Meneton P., Miller M.L., Soleimani M., Gawenis L.R., Riddle T.M., Duffy J.J., Doetschman T., Wang T., Giebisch G., Aronson P.S., Lorenz J.N., Shull G.E. Renal and intestinal absorptive defects in mice lacking the NHE3 Na+/H+ exchanger. Nat. Genet. 1998;19(3):282–285. doi: 10.1038/969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gurney M.A., Laubitz D., Ghishan F.K., Kiela P.R. Pathophysiology of intestinal Na(+)/H(+) exchange. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017;3(1):27–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2016.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang J., Jose P.A., Zeng C. Gastrointestinal-renal axis: role in the regulation of blood pressure. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017;6(3) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.005536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Furness J.B., Rivera L.R., Cho H.J., Bravo D.M., Callaghan B. The gut as a sensory organ. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013;10(12):729–740. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Y., Asico L.D., Zheng S., Villar V.A., He D., Zhou L., Zeng C., Jose P.A. Gastrin and D1 dopamine receptor interact to induce natriuresis and diuresis. Hypertension. 2013;62(5):927–933. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turnbaugh P.J., Ley R.E., Hamady M., Fraser-Liggett C.M., Knight R., Gordon J.I. The human microbiome project. Nature. 2007;449(7164):804–810. doi: 10.1038/nature06244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cho I., Blaser M.J. The human microbiome: at the interface of health and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012;13(4):260–270. doi: 10.1038/nrg3182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilck N., Matus M.G., Kearney S.M., Olesen S.W., Forslund K., Bartolomaeus H., Haase S., Mahler A., Balogh A., Marko L., Vvedenskaya O., Kleiner F.H., Tsvetkov D., Klug L., Costea P.I., Sunagawa S., Maier L., Rakova N., Schatz V., Neubert P., Fratzer C., Krannich A., Gollasch M., Grohme D.A., Corte-Real B.F., Gerlach R.G., Basic M., Typas A., Wu C., Titze J.M., Jantsch J., Boschmann M., Dechend R., Kleinewietfeld M., Kempa S., Bork P., Linker R.A., Alm E.J., Muller D.N. Salt-responsive gut commensal modulates TH17 axis and disease. Nature. 2017;551(7682):585–589. doi: 10.1038/nature24628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrison C.A., Laubitz D., Ohland C.L., Midura-Kiela M.T., Patil K., Besselsen D.G., Jamwal D.R., Jobin C., Ghishan F.K., Kiela P.R. Microbial dysbiosis associated with impaired intestinal Na(+)/H(+) exchange accelerates and exacerbates colitis in ex-germ free mice. Mucosal Immunol. 2018;11(5):1329–1341. doi: 10.1038/s41385-018-0035-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Felker G.M., O'Connor C.M., Braunwald E., Heart I. Failure Clinical Research Network, Loop diuretics in acute decompensated heart failure: necessary? Evil? A necessary evil? Circ. Heart Fail. 2009;2(1):56–62. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.821785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Charmot D. Non-systemic drugs: a critical review. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2012;18(10):1434–1445. doi: 10.2174/138161212799504858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spencer A.G., Labonte E.D., Rosenbaum D.P., Plato C.F., Carreras C.W., Leadbetter M.R., Kozuka K., Kohler J., Koo-McCoy S., He L., Bell N., Tabora J., Joly K.M., Navre M., Jacobs J.W., Charmot D. Intestinal inhibition of the Na+/H+ exchanger 3 prevents cardiorenal damage in rats and inhibits Na+ uptake in humans. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014;6(227):227–236. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zielinska M., Wasilewski A., Fichna J. Tenapanor hydrochloride for the treatment of constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs. 2015;24(8):1093–1099. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2015.1054480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenbaum D.P., Yan A., Jacobs J.W. Pharmacodynamics, safety, and tolerability of the NHE3 inhibitor tenapanor: two trials in healthy volunteers. Clin. Drug Invest. 2018;38(4):341–351. doi: 10.1007/s40261-017-0614-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johansson S., Rosenbaum D.P., Knutsson M., Leonsson-Zachrisson M. A phase 1 study of the safety, tolerability, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics of tenapanor in healthy Japanese volunteers. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2017;21(3):407–416. doi: 10.1007/s10157-016-1302-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Block G.A., Rosenbaum D.P., Leonsson-Zachrisson M., Astrand M., Johansson S., Knutsson M., Langkilde A.M., Chertow G.M. Effect of tenapanor on serum phosphate in patients receiving hemodialysis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.: JASN. 2017;28(6):1933–1942. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016080855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Labonte E.D., Carreras C.W., Leadbetter M.R., Kozuka K., Kohler J., Koo-McCoy S., He L., Dy E., Black D., Zhong Z., Langsetmo I., Spencer A.G., Bell N., Deshpande D., Navre M., Lewis J.G., Jacobs J.W., Charmot D. Gastrointestinal inhibition of sodium-hydrogen exchanger 3 reduces phosphorus absorption and protects against vascular calcification in CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.: JASN. 2015;26(5):1138–1149. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014030317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Block G.A., Rosenbaum D.P., Yan A., Chertow G.M. Efficacy and safety of tenapanor in patients with hyperphosphatemia receiving maintenance hemodialysis: a randomized phase 3 trial. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.: JASN. 2019;30(4):641–652. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2018080832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Block G.A., Rosenbaum D.P., Leonsson-Zachrisson M., Stefansson B.V., Ryden-Bergsten T., Greasley P.J., Johansson S.A., Knutsson M., Carlsson B.C. Effect of tenapanor on interdialytic weight gain in patients on hemodialysis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.: CJASN. 2016;11(9):1597–1605. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09050815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johansson S., Rosenbaum D.P., Ahlqvist M., Rollison H., Knutsson M., Stefansson B., Elebring M. Effects of tenapanor on cytochrome P450-mediated drug-drug interactions. Clin. Pharmacol. Drug Dev. 2017;6(5):466–475. doi: 10.1002/cpdd.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Graudal N.A., Galloe A.M., Garred P. Effects of sodium restriction on blood pressure, renin, aldosterone, catecholamines, cholesterols, and triglyceride: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 1998;279(17):1383–1391. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.17.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Musch M.W., Li Y.C., Chang E.B. Angiotensin II directly regulates intestinal epithelial NHE3 in Caco2BBE cells. BMC Physiol. 2009;9:5. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-9-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chey W.D., Lembo A.J., Rosenbaum D.P. Efficacy of tenapanor in treating patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation: a 12-week, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial (T3MPO-1) Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020;115(2):281–293. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chey W.D., Lembo A.J., Rosenbaum D.P. Tenapanor treatment of patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: a phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled efficacy and safety trial. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2017;112(5):763–774. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Linz B., Hohl M., Reil J.C., Bohm M., Linz D. Inhibition of NHE3-mediated sodium absorption in the gut reduced cardiac end-organ damage without deteriorating renal function in obese spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2016;67(3):225–231. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hohl M., Lau D.H., Muller A., Elliott A.D., Linz B., Mahajan R., Hendriks J.M.L., Bohm M., Schotten U., Sanders P., Linz D. Concomitant obesity and metabolic syndrome add to the atrial arrhythmogenic phenotype in male hypertensive rats. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017;6(9) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Linz B., Hohl M., Mishima R., Saljic A., Lau D.H., Jespersen T., Schotten U., Sanders P., Linz D. Pharmacological inhibition of sodium-proton-exchanger subtype 3-mediated sodium absorption in the gut reduces atrial fibrillation susceptibility in obese spontaneously hypertensive rats. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasculat. 2020;28 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2020.100534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sankar N.S., Donaldson D. Lessons to be learned: a case study approach diuretic therapy and a laxative causing electrolyte and water imbalance, loss of attention, a fall and subsequent fractures of the tibia and fibula in an elderly lady. J. R. Soc. Promot. Health. 1998;118(4):237–240. doi: 10.1177/146642409811800410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cho J.H., Musch M.W., Bookstein C.M., McSwine R.L., Rabenau K., Chang E.B. Aldosterone stimulates intestinal Na+ absorption in rats by increasing NHE3 expression of the proximal colon. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;274(3):C586–C594. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.3.C586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dominguez Rieg J.A., de la Mora Chavez S., Rieg T. Novel developments in differentiating the role of renal and intestinal sodium hydrogen exchanger 3. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2016;311(6):R1186–R1191. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00372.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alexander F. The effect of diuretics on the faecal excretion of water and electrolytes in horses. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1977;60(4):589–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1977.tb07539.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mishima R.S., Elliott A.D., Sanders P., Linz D. Microbiome and atrial fibrillation. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018;255:103–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.12.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mishima R.S., Elliott A.D., Sanders P., Linz D. Gastrointestinal sodium absorption, microbiome, and hypertension. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2017;14(11):693. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2017.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tanaka M., Itoh H. Hypertension as a metabolic disorder and the novel role of the gut. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2019;21(8):63. doi: 10.1007/s11906-019-0964-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pluznick J.L. Microbial short-chain fatty acids and blood pressure regulation. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2017;19(4):25. doi: 10.1007/s11906-017-0722-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pluznick J.L., Protzko R.J., Gevorgyan H., Peterlin Z., Sipos A., Han J., Brunet I., Wan L.X., Rey F., Wang T., Firestein S.J., Yanagisawa M., Gordon J.I., Eichmann A., Peti-Peterdi J., Caplan M.J. Olfactory receptor responding to gut microbiota-derived signals plays a role in renin secretion and blood pressure regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2013;110(11):4410–4415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215927110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Afsar B., Vaziri N.D., Aslan G., Tarim K., Kanbay M. Gut hormones and gut microbiota: implications for kidney function and hypertension. J. Am. Soc. Hypertens. 2016;10(12):954–961. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Psichas A., Sleeth M.L., Murphy K.G., Brooks L., Bewick G.A., Hanyaloglu A.C., Ghatei M.A., Bloom S.R., Frost G. The short chain fatty acid propionate stimulates GLP-1 and PYY secretion via free fatty acid receptor 2 in rodents. Int. J. Obes. (Lond) 2015;39(3):424–429. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2014.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shimizu J., Kubota T., Takada E., Takai K., Fujiwara N., Arimitsu N., Murayama M.A., Ueda Y., Wakisaka S., Suzuki T., Suzuki N. Propionate-producing bacteria in the intestine may associate with skewed responses of IL10-producing regulatory T cells in patients with relapsing polychondritis. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lima V.V., Zemse S.M., Chiao C.W., Bomfim G.F., Tostes R.C., Clinton Webb R., Giachini F.R. Interleukin-10 limits increased blood pressure and vascular RhoA/Rho-kinase signaling in angiotensin II-infused mice. Life Sci. 2016;145:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bartolomaeus H., Balogh A., Yakoub M., Homann S., Marko L., Hoges S., Tsvetkov D., Krannich A., Wundersitz S., Avery E.G., Haase N., Kraker K., Hering L., Maase M., Kusche-Vihrog K., Grandoch M., Fielitz J., Kempa S., Gollasch M., Zhumadilov Z., Kozhakhmetov S., Kushugulova A., Eckardt K.U., Dechend R., Rump L.C., Forslund S.K., Muller D.N., Stegbauer J., Wilck N. Short-chain fatty acid propionate protects from hypertensive cardiovascular damage. Circulation. 2019;139(11):1407–1421. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.036652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dalla Via A., Gargari G., Taverniti V., Rondini G., Velardi I., Gambaro V., Visconti G.L., De Vitis V., Gardana C., Ragg E., Pinto A., Riso P., Guglielmetti S. Urinary TMAO levels are associated with the taxonomic composition of the gut microbiota and with the choline TMA-Lyase Gene (cutC) harbored by enterobacteriaceae. Nutrients. 2019;12(1) doi: 10.3390/nu12010062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Polsinelli V.B., Marteau L., Shah S.J. The role of splanchnic congestion and the intestinal microenvironment in the pathogenesis of advanced heart failure. Curr. Opin. Support Palliat. Care. 2019;13(1):24–30. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Antza C., Stabouli S., Kotsis V. Gut microbiota in kidney disease and hypertension. Pharmacol. Res. 2018;130:198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hecht G., Hodges K., Gill R.K., Kear F., Tyagi S., Malakooti J., Ramaswamy K., Dudeja P.K. Differential regulation of Na+/H+ exchange isoform activities by enteropathogenic E. coli in human intestinal epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2004;287(2):G370–G378. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00432.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Engevik M.A., Engevik K.A., Yacyshyn M.B., Wang J., Hassett D.J., Darien B., Yacyshyn B.R., Worrell R.T. Human Clostridium difficile infection: inhibition of NHE3 and microbiota profile. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2015;308(6):G497–G509. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00090.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Singh V., Raheja G., Borthakur A., Kumar A., Gill R.K., Alakkam A., Malakooti J., Dudeja P.K. Lactobacillus acidophilus upregulates intestinal NHE3 expression and function. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2012;303(12):G1393–G1401. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00345.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Laubitz D., Harrison C.A., Midura-Kiela M.T., Ramalingam R., Larmonier C.B., Chase J.H., Caporaso J.G., Besselsen D.G., Ghishan F.K., Kiela P.R. Reduced epithelial Na+/H+ exchange drives gut microbial dysbiosis and promotes inflammatory response in T cell-mediated murine colitis. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]