Abstract

Background

An outbreak of Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) has spread rapidly reaching over 3 million of confirmed cases worldwide. The association of respiratory diseases and smoking, both highly prevalent globally, with COVID-19 severity has not been elucidated. Given the gap in the evidence and the growing prevalence of COVID-19, the objective of this study was to explore the association of underlying respiratory diseases and smoking with severe outcomes in patients with COVID-19 infection.

Methods

A systematic search was performed to identify studies reporting prevalence of respiratory diseases and/or smoking in relation with disease severity in patients with confirm COVID-19, published between January 1 to April 15, 2020 in English language. Pooled odds-ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated.

Findings

Twenty two studies met the inclusion criteria. All the studies presented data of 13,184 COVID-19 patients (55% males). Patients with severe outcomes were older and a larger percentage were males compared with the non-severe. Pooled analysis showed that prevalence of respiratory diseases (OR 4.21; 95% CI, 2.9–6.0) and smoking (current smoking OR 1.98; 95% CI, 1.16–3.39 and former smoking OR 3.46; 95% CI, 2.46–4.85) were significantly associated with severe COVID-19 outcomes.

Interpretation

Results suggested that underlying respiratory diseases, specifically COPD, and smoking were associated with severe COVID-19 outcomes. These findings may support the planning of preventive interventions and could contribute to improvements in the assessment and management of patient risk factors in clinical practice, leading to the mitigation of severe outcomes in patients with COVID-19 infection.

1. Introduction

An outbreak of Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection was identified in Wuhan, China in December 2019. Currently, the disease has spread rapidly worldwide reaching over 3 million of confirmed cases, including 208,516 deaths as of April 27, 2020 [1].

Unique clinical features identified within the confirmed cases included a higher proportion of males, older adults and people with underlying comorbidities [[2], [3], [4], [5]]. Preliminary studies reported severe COVID-19 outcomes in patients with underlying cardiovascular diseases, arterial hypertension and diabetes [2,6]. It was also suggested that presence of underlying respiratory diseases in general may contribute to severe COVID-19 outcomes [7], however, this association has not been elucidated and specific respiratory diseases have not been explored. In addition, emerging literature indicates that smokers may have more severe COVID-19 infections than non-smokers [8]. However, a recently meta-analysis did not find a significant association between active smoking and severe COVID-19 [9].

Respiratory diseases and smoking are highly prevalent worldwide. More specifically, reports indicate that about 65 million people suffer from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), 334 million people suffer from asthma, and over 10 million people developed tuberculosis in 2015 [10]. It was estimated that one-in-five (20%) adults in the world smoke tobacco [11], which is also a recognized risk factor for respiratory diseases.

The association of respiratory diseases and smoking, both highly prevalent globally, with severe COVID-19 outcomes has not been elucidated. Given the gap in the evidence and the growing prevalence of COVID-19, the objective of this article was to explore the association of underlying respiratory diseases and smoking with severe outcomes in patients with COVID-19 infection. Results of this study may support the development of preventive and clinical interventions leading to mitigate severe outcomes in patients with COVID-19.

2. Methods

2.1. Search and selection criteria

We incorporated PRIMA guidelines through our review. A systematic search was conducted in the electronic bibliographic databases of PubMed, Web of Sciences, and Ovid MEDLINE. The key words and strategy used were: ((‘COVID-19’ OR ‘COVID 19’ OR ‘Novel coronavirus’ OR ‘SARS-CoV-2’ OR ‘coronavirus 2019’ OR ‘2019-nCoV’ OR ‘coronavirus disease 2019’) AND ((‘comorbidities’ OR ‘clinical characteristics’ OR ‘characteristics’ OR epidemiology) OR (‘smoking’ OR ‘tobacco’ OR ‘risk factors’ OR ‘smoker’))). The search was limited to journal articles published in 2020 (January 1 to April 15). We examined the reference lists of articles to identify additional studies.

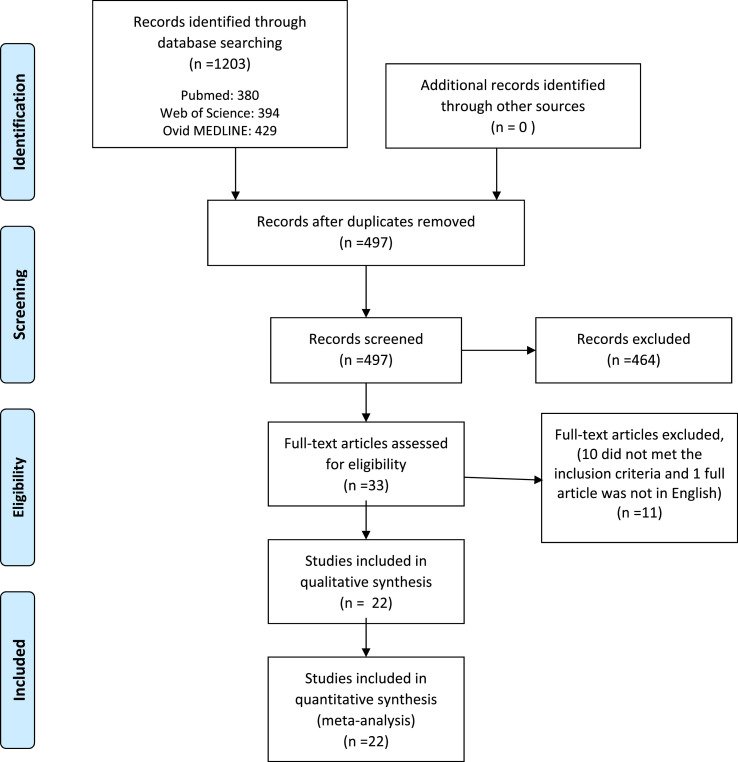

The systematic search retrieved 1203 references. After removing duplicates, two researchers (DS and DM) screened 497 titles and abstracts and 33 read full text articles. Both researchers independently reviewed the articles, before coming to a consensus opinion, to include 22 publications that met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1 ). The main reasons for study exclusion included: 1) the study did not provide prevalence of comorbidities or smoking in patients with COVID-19; 2) prevalence of comorbidities in patients with COVID-19 was grouped in one variable and specific information on respiratory diseases was not available, and history of smoking was not included; 3) COVID-19 disease severity in relation with the prevalence of chronic respiratory diseases or smoking was not presented; and 4) the full text of the study was not in the English language. A total of 22 publications met the inclusion criteria of: 1) describe COVID-19 severity in relation with prevalence of chronic respiratory diseases and/or smoking; 2) the publication was not a meta-analysis or systematic review; and 3) full text of the study was available in English language.

Fig. 1.

Diagram flow of studies screened and included in the review and meta-analysis.

2.2. Data extraction and analysis

The information of the 22 articles was synthesized in Table 1 , which presented: 1) author(s)’ name and title of the study; 2) country of the study; 3) number of cases included and setting of data collection; 4) definition of the study for severe and non-severe COVID-19 outcomes and number of patients in each group. Severe COVID-19 outcomes included cases admitted to the ICU, reported as death or non-survivors, worsened during hospitalization, or identified as severe or critical using guidelines by the National Health Commission, the American Thoracic Society or the Chinese National Health Committee. Non-severe outcomes included cases who presented mild to moderated symptoms, were not hospitalized or hospitalized but non-ICU, survived, recovered, remained stable during hospitalization, or identified as non-severe based on guidelines by the National Health Commission, the American Thoracic Society or the Chinese National Health Committee; 5) age and gender of the patients studied; 6) number of underlying respiratory diseases among patients with severe and non-severe outcomes; and 7) number of smokers (current and/or former) with severe and non-severe COVID-19 outcomes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

| Study | Country | Population/Data | Outcome of the study (grouped as severe and non-severe in this review) |

Participants of the study |

Underlying Respiratory Diseases by outcome, number (%) |

Smoking by outcome, number (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Male Gender Number (%) | Current smoker | Former smoker | |||||

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) COVID-19 Response Team (2020)24 “Preliminary Estimates of the Prevalence of Selected Underlying Health Conditions Among Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 - United States, February 12-March 28, 2020” | United States China | 7,162 patients with laboratory confirmed COVID-19 and data on underlying health conditions and other risk factors. Data was gathered from report forms from 50 state, four U.S. territories and affiliated islands, the District of Columbia, and New York City submitted to CDC with February 12-March onset dates. 102 adult patients with COVID-19 admitted to Wuhan University Zhongnan Hospital in Wuhan between January 3 and February 1, 2020 | Severe: ICU admission (n=457), Non-severe: not hospitalized and hospitalized non-ICU (n=6180) Patients with hospitalization status unknown were not included (n=525) | N/A | N/A | Chronic lung disease Severe: n=94(21), Non-Severe: n= 515(8) | Severe: n = 5 (1) | Severe: n = 33 (7) |

| Cao J et al. (2020)12 “Clinical Features and Short-term Outcomes of 102 Patients with Corona Virus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China” | Severe: non-survivors (n=17), Non-severe: survivors (n=85) | Median (IQR) Severe : 72(63-81), Non-severe:53(47-66) | Severe: 13(76), Non-severe: 40(53) | Respiratory diseases Severe: n=4(24), Non-Severe: n=6(7) | Non-severe: n = 83 (1) | Non-severe: n = 125 (2) | ||

| Chen T et al. (a)(2020)14 “Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study” | China | 274 moderately to severely ill or critically ill patients with confirmed COVID-19 transferred to Tongji Hospital between January 13 and February12, 2020 | Severe: deaths (n=113), Non-severe: recovered patients (n=161) | Median (Q1, Q3) Severe: 68(62-77), Non-severe: 51(37-66) | Severe: 83(73), Non-severe: 88(55) | Chronic lung diseases Severe: n=11(10), Non-Severe: n=7(4) | - | |

| Chen T et al. (b)(2020)13 “Clinical characteristics and outcomes of older patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective study” | China | 55 adults ≥65 years with confirmed COVID-19 hospitalized at Zhognan Hospital of Wuhan University from January 1, 2020 to February 10, 2020., For which disease severity in relation with underlying respiratory conditions was presented | Severe: adults ≥65 who died (n=19), Non-severe: adults ≥65 who survived (n=36) | Median Severe: 77, Non-severe: 72 | Severe: 16(84), Non-severe: 18(50) | COPD Severe: n=1(5), Non-severe: n=6(17) | - | |

| Deng et al (2020)15 “Clinical characteristics of fatal and recovered cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China: a retrospective study” | China | 225 patients with confirmed COVID-19 hospitalized in two tertiary hospital in Wuhan (Hankou and Cai dian branch of Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science & Technology, and Hankou Branch of Central Hospital of Wuhan) from January 1, 2020 to February 21, 2020 | Severe: death group (n=109), Non-severe: recovered group (n=116) | Median (Q1, Q3) Severe: 69(62, 74), Non-severe: 40(33, 57) | Severe: 73(67), Non-severe: 51(44) | Lung disease Severe: n=22(20), Non-Severe: n=3(3) | Severe: n=7(6) | Severe: n=5(4) |

| Feng Y et al. (2020)16 “COVID-19 with Different Severity: A multi-center Study of Clinical Features.” | China | 476 patients with COVID-19 recruited from Jan 1 to Feb 15, 2020 at three hospitals in Wuhan (Jinyintan Hospital in Wuhan, Shanghai Public Health Clinical in Shanghai and Tongling People’s Hospital in Anhui Province, China) | Severe (n=124): included severe (n=54) and critical (n=70) cases classified using the fifth version of the guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of COVID-19 by the National Health Commission of, COVID-19 severity, Non-severe: moderate disease (n=352) (fever, cough and other symptoms are present with pneumonia on chest computer tomography) | Median (IQR) Severe: Severe 58(48-67), Critical 61(49-68), Non-severe: 51(37-63) | Severe (61) Critical(69), Non-severe: 190(54) | COPD Severe: n=14(11), Non-severe: n=8(2) | Non-severe: n=2(1) | Non-severe: n=5(3) |

| Guan WJ et al. (a)(2020)18 “Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China” | China | Data of 1099 patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 from 552 hospitals in 30 provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities in mainland China from December 11, 2019 to January 29, 2020 | Severe: severe disease at admission (n=173) defined using the American Thoracic Society guidelines for community-acquired pneumonia, Non-severe: non-severe disease at admission (926) | Median (IQR) Severe: 52(40-65), Non-severe:45(34-57) | Severe: 100(58), Non-severe: 537(58) | COPD Severe: n=6(3), Non-Severe: n=6(1) | - | |

| Guan WJ et al. (b)(2020)1 “Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with Covid-19 in China: A Nationwide Analysis” | China | 1590 patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 from 575 hospitals in 31 province/autonomous region/provincial municipalities across mainland China between Dec 11th and January 31st, 2020 | Severe: severe COVID-19 (n=254) based on the 2007 American Thoracic Society/Infections Disease Society of America Guidelines.Non-severe: non-severe COVID-19 (1336) | Mean (SD) 48.9 (16) | 904 (57) | COPD Severe: n=15(6), Non-Severe: n=9(1) | - | |

| Huang C et al. (2020)19 “Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China.” | China | 41 patients with confirmed COVID-19 admitted to a hospital from De 16, 2019 to January 2, 2020 (local health authority) | Severe: ICU care (n=13, Non-severe: no ICU care (n=28) | Mean (IQR) Severe: 49(41-61), Non-severe:49(41-58) | Severe: 11(85), Non-severe:19(68) | COPD Severe: n=1(8), Non-Severe: n=0 | - | |

| Ji D et al. (2020)20 “Prediction for Progression Risk in Patients with COVID-19 Pneumonia: the CALL score” | China | 208 patients with COVID-19 admitted to Fuyang second people’s hospital or the fifth medical center of Chines PLA general hospital between January 20 and February 22, 2020 | Based on whether their conditions worsened during the hospitalization. Severe: progressive group (n=40), Non-severe: stable group (n=168) | Mean (SD) Severe: 58(16), Non-severe: 41(15) | Severe: 28(70), Non-severe: 89(53) | N/A | - | |

| Li K et al. (2020)21 “The clinical and chest CT features associated with severe and critical COVID-19 pneumonia” | China | 83 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia admitted to “our” [Chinese] hospitals from January 2020 to February 2020 | Severe: the severe/critical patients (n=25) met any of the following conditions: 1) respiratory rate ≥30 breaths per minute; 2) finger of oxygen saturation ≤93% in a resting state; 3) arteria oxygen tension (PaO2)/inspiratory, oxygen fraction (FiO2) ≤300 mmHG; 4) respiratory failure occurred and mechanical ventilation required; 5) shock occurred; 6) patient with other organ failure needed ICU. Non-severe: the ordinary patients (n=58) all had fever or other respiratory symptoms with CT manifestations of pneumonia | Mean (SD) Severe: 54(12), Non-severe:42(11) | Severe: 15(60), Non-severe:29(50) | COPD Severe: n=4(16), Non-severe: n=1(2) | - | |

| Li YK et al. (2020)22 “Clinical and Transmission Characteristics of Covid-19 - A Retrospective Study of 25 Cases from a Single Thoracic Surgery Department” | China | 25 cases (12 health care staff and 13 hospitalized patients) identified in the Department of Thoracic Surgery of Tongji Hospital affiliated to Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology, between January 1, 2020 and February 20, 2020 | Severe: severe disease (n=9) according to the “diagnosis and treatment guidelines of COVID-19 (version 7.0)” from the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Non-severe: non-severe disease (n=16) | All median 51 | Severe: 6(67), Non-severe 6(38) | COPD Severe: n=4(44), Non-severe: n=1(6) | - | |

| Lui W et al. (2020)23 “Analysis of factors associated with disease outcomes in hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus disease” | China | 78 patients with COVID-19 admitted to three tertiary hospitals in Wuhan between December 30, 2019 and January 15, 2020 | Severe: progression group (n=11), common-type changed to severe- or critical-type, or death; severe-type changed to critical-type or death; critical-type progressed to death. Non-severe: improvement/stabilization group (n=67), common-, severe-, and critical-types remained unchanged; severe-type changed to common-type; critical-type changed to severe- or common-type | Median (Q1-Q3), Severe: 66(51,70), Non-severe: 37(32,41) | Severe: 7(64), Non-severe: 32(48) | COPD Severe: n=1(9), Non-Severe: n=1(1) | - | |

| Wan D et al. (2020)2 “Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China” | China | 138 patients hospitalized at Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University in Wuhan, China, from January 1 to January 28, 2020; final data of follow-up was Feb 3, 2020 | Severe: ICU (n=36), Non-severe: non-ICU (n=102) | Median (IQR) Severe : 66(57-78), Non-severe:51(37-62) | Severe: 22(61), Non-severe: 53(52) | COPD Severe: n=3(8), Non-Severe: n=1(1) | - | |

| Wang L et al. (2020)26 “Coronavirus Disease 2019 in elderly patients: characteristics and prognostic factors based on 4-week follow-up” | China | 339 patients over 60 years old with COVID-19 admitted to Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University from Jan 1 to Feb 6, 2020 | Severe: dead (n=65), Non-severe: survival (n=274) | Median (IQR) Severe: 76(70-83), Non-severe: 68(64-74) | Severe: 26(60), Non-severe: 127(46) | COPD Severe: n=11(17), Non-Severe: n=10(4) | - | |

| Wan S et al. (2020)25 “Clinical features and treatment of COVID-19 patients in northeast Chongqing” | China | 135 patients with COVID-19 hospitalized in the Chongqing University Three Gorges Hospital from 23 January to 8 February, 2020 | Severe: severe cases (n=40)(including severe and critical). The severe group had respiratory distress, RR≥30 beats/minute in a resting state, a mean oxygen saturation of ≤93% , and an arterial blood oxygen partial pressure (PaO2)/oxygen concentration (Fio2)≤300 mm Hg. The critical group had respiratory failure and required mechanical ventilation, the occurrence of shock, and the combined failures of other organs that required ICU monitoring and treatment, Non-severe: mild cases (n=95) (including normal and mild). The mild group has mild clinical symptoms and no pneumonia on imaging. The normal group had symptoms of fever, respiratory tract symptoms, and imaging showed pneumonia | Median (IQR) Severe : 56(52-73), Non-severe: 44(33-49) | Severe: 21(53), Non-severe: 52(55) | COPD and pulmonary disease Severe: n=5(13), Non-Severe: n=0 | - | |

| Wang X et al. (2020)27 “Clinical characteristics of non-critically ill patients with novel coronavirus infection (COVID-19) in a Fangcang Hospital” | China | 1012 non-critical ill patients with positive SARS-CoV-2 admitted to Dongxihu “Fangcang” Hospital between February 7th and 12th; clinical course through February 22nd was recorded | Severe: patients with aggravation of illness during follow up (n=100). Identified as: (i) symptoms persisted to worsened for more than 7 days; (ii) Respiratory rate≥30 or blood oxygen saturation ≤93%, at rest; (iii) Pulmonary imaging showed that the lesions progressed more than 50% within 48 hours. Non-severe: patients without aggravation of illness during follow up (n=912) | Median (IQR) Severe : 56(47-62), Non-severe:50(38-58) | Severe: 62(62), Non-severe:462(51) | Respiratory system disease Severe: n=2(2), Non-Severe: n=18(2) | - | |

| Yang X et al. (2020)28 “Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study” | China | 52 critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) of Wuhan Jin Yin-tan hospital between late December, 2019 and Jan 26, 2020 | Severe: non-survivors (n=32), Non-severe: survivors (n=20) | Mean(SD) Severe: 65(11), Non-severe:52(13) | Severe: 21(66), Non-severe: 14(70) | Chronic pulmonary disease Severe: n=2(6), Non-Severe: n=2(10) | - | |

| Zhang JJ et al. (2020)29 “Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy” | China | 140 patients diagnosed as COVID-19 hospitalized in No. 7 Hospital of Wuhan (admission from January 16 to February 3, 2020) were included in the study | Severe: severe patients (n=58) were defined according to the diagnostic and treatment guideline for SARS-CoV-2 issue by Chinese National Health Committee (Version 3-5). The severe group had one of the following criteria: a) respiratory distress with respiratory frequency≥30/minute; (b) pulse oximeter oxygen saturation of ≤93% at rest; and (c) oxygenation index (arterial blood oxygen/inspired oxygen fraction, PaO2/Fio2)≤300 mm Hg, Non-severe: nonsevere patients (n=82) | Mean (range) Severe : 64(25-87), Non-severe:52(26-78) | Severe: 33(57), Non-severe:38(46) | COPD, secondary pulmonary tuberculosis and Asthma, Severe: n=4(3), Non-Severe: n=0 | - | |

| Zhang R et al. (2020)30 “CT features of SARS-CoV2 pneumonia according to clinical presentation: a retrospective analysis of 120 consecutive patients from Wuhan city” | China | 120 patients with confirmed SARS-CoV2 infection from January 1 to February 10, 2020, at the Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University were included | Severe: severe type according with the National Guidelines of China (n=30), Non-severe: common type (n=90) | Mean(SD) Severe: 61(12), Non-severe:40(13) | Severe: 13(43), Non-severe: 30(33) | COPD Severe: n=3(10), Non-severe: n=1(1) | - | |

| Zhen F et al. (2020)31 “Clinical characteristics of 161 cases of corona virus disease 2019(COVID-19) in Changsha” | China | 161 patients with conformed COVID-19 admitted to the North Hospital of Changsha first Hospital from January 17 to Feb 7, 2020 | According to the COVID-19 diagnosis and treatment plan issue by the National Health Commission (trial version), all cases were divided into severe (n=30) and non-severe (n=131) | Median (range) Severe: 57(47,66), Non-severe:40(31,51) | Severe: 14(47), Non-severe: 66(50) | COPD Severe: n=2(7), Non-severe: n=4(3) | - | |

| Zhou F et al. (2020)32 “Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study” | China | 191 patients with laboratory- confirmed COVID-19 (135 from Jinyintan Hospital and 56 from Wuhan Pulmonary Hospital) who died or were discharged between Dec 29, 2019 and Jan 31, 2020 | Severe: non-survivor (n=54), Non-severe: survivor (n=137) | Median (IQR) Severe : 69(63-76), Non-severe:52(45-58) | Severe: 38(70), Non-severe: 81(59) | Chronic obstructive lung disease Severe: n=4(7), Non-Severe: n=2(1) | - | |

ICU= Intensive Care Unit. SD = standard deviation. COPD=Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. N/A = No information is presented in the article, or the information presented is not directly related with the clinical severity of the patients.

The Review Manager (RevMan; version 5.3; Copenhagen, Denmark) software was used to pool the individual included studies. The analysis is presented as ORs based on the likelihood of severe COVID-19 outcome in patients with underlying respiratory diseases and history of smoking compared with patients without those potential risk factors using random-effects methods. To investigate heterogeneity between studies, the authors used the I2 index which describes the percentage of variation across the studies in the pooled analysis that is due to inconsistency rather than by chance. A value of 0% indicates no observed heterogeneity, and larger values show increasing heterogeneity.

3. Results

This review included 22 publications that described severe COVID-19 outcomes in relation with the prevalence of chronic respiratory diseases and/or smoking (Table 1) [2,[12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32]]. The majority of those studies were completed in China (95%). The studies presented data of 13,184 patients with confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19, 55% of which were males. Patients with COVID-19 were included in the group of severe outcomes if they exhibited worsening of their clinical symptoms presented at admission or met various criteria compiled in existing clinical guidelines [[16], [17], [18],[20], [21], [22], [23],25,27,[29], [30], [31]], required ICU care [2,19,24] or died [[12], [13], [14], [15],26,28,32]. Compared with the non-severe outcome group, patients in the severe outcome group were older and a larger percentage of them were males (63% vs 51%).

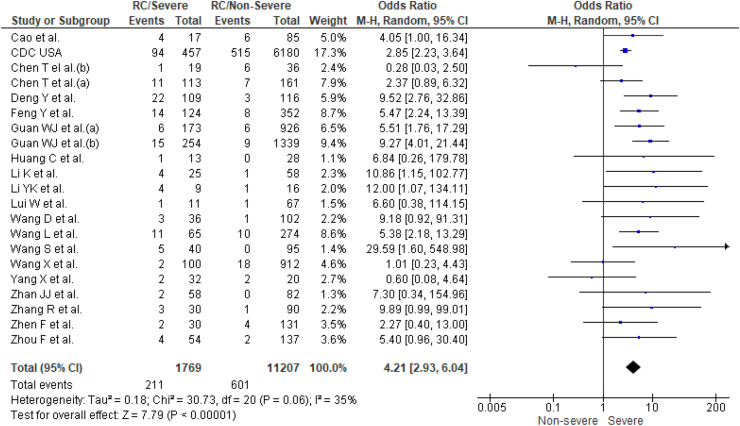

3.1. Prevalence of chronic respiratory diseases

Twenty one studies [2,[12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19],[21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32]] reported prevalence of respiratory diseases in patients with COVID-19 (n = 12,976). COPD was the main respiratory disease documented in the studies [2,13,[16], [17], [18], [19],[21], [22], [23],25,26,[29], [30], [31]], one study also reported pulmonary tuberculosis and asthma [29], and others reported respiratory comorbidities using terms such as respiratory system diseases, chronic lung diseases, lung disease, or pulmonary diseases. A higher prevalence of respiratory diseases (12%) was found in patients with severe COVID-19 outcomes compared with the non-severe outcomes group (4%). The results of the meta-analysis (Fig. 2 ) showed that patients with underlying respiratory diseases had a significantly higher odds of severe COVID-19 outcomes when data from the individual studies were pooled (OR 4.21; 95% CI, 2.9–6.0). No significant study heterogeneity (I2, 35%, p = 0.06) was evident. A separate sensitivity analysis showed that patients with underlying COPD had higher odds of having severe-19 outcomes (OR 5.8; 95% CI, 3.9–8.5).

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of underlying respiratory conditions (RC) in severe patients compared to non-severe patients with COVID-19.

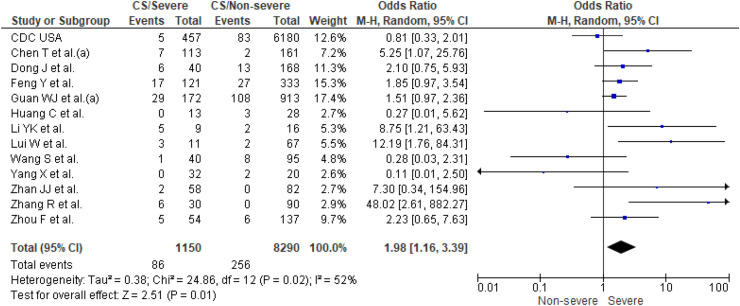

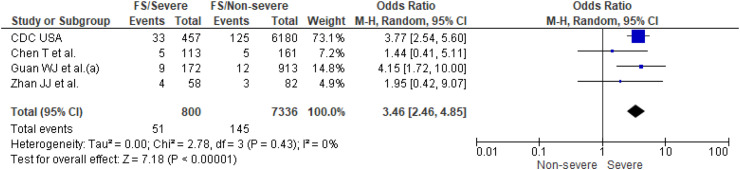

3.2. Prevalence of smoking

Thirteen studies [14,16,[18], [19], [20],[22], [23], [24], [25],[28], [29], [30],32] reported prevalence of current smoking (n = 9440 patients) and four of them [14,18,24,29] also reported prevalence of former smoking (n = 8136 patients). Prevalence of current and former smoking was higher in patients with severe COVID-19 outcomes (13% and 6%) than in non-severe outcomes (6% and 3%). Individual and pooled results for prevalence of current and former smoking are presented in Fig. 3, Fig. 4 , respectively. The results of the meta-analysis showed that smokers (current smokers OR 1.98; 95% CI, 1.16–3.39 and former smokers OR 3.46; 95% CI, 2.46–4.85) had significantly higher odds of severe COVID-19 outcomes. The analysis showed high heterogeneity for estimates of current smoking (I2, 52%, p = 0.02), but no significant study heterogeneity (I2, 0%, p = 0.43) was evident for estimates of former smoking.

Fig. 3.

Current smoking (CS) in severe patients compared to non-severe patients with COVID-19.

Fig. 4.

Former smoking (FS) in severe patients compared to non-severe patients with COVID-19.

4. Discussion

This literature review and meta-analysis compiles evidence from 22 studies that provide information on patients’ underlying respiratory diseases and smoking in relation to COVID-19 severity. Results of the pooled analysis show that prevalence of underlying respiratory diseases was a significant predictor for severe COVID-19 outcomes. Results of this study align with a previous smaller meta-analysis (four studies) which reported significant respiratory system diseases in severe COVID-19 patients compared with non-severe (OR 2.46, 95% CI: 1.76–3.44) (7). However, our review gathered a larger number of recent publications relevant to the topic and showed a stronger association (OR 4.21, 95% CI: 2.9–6.0).

Respiratory diseases were reported using a general variable which may potentially group various conditions or specifically refer to COPD. Information on other respiratory diseases was lacking except for one study that reported prevalence of COPD, asthma and secondary pulmonary TB [29]. Consequently, questions arise around the reasons leading to a lack of information on prevalence of respiratory diseases, other than COPD, and COVID-19 severity in the literature. It has been found that COPD is not infrequently misclassified due to underutilization of confirmatory spirometry and to the healthcare professional performing the diagnostic assessment [33,34]. However, it is also possible that other respiratory diseases were underdiagnosed or not appropriately documented in the databases, which is unlikely because this information was missing across most of the studies including the report from the Center for Disease Control (CDC) in the United States [24]. Another possibility may be that prevalence of other respiratory diseases may not be associated with severe COVID-19 outcomes due to their specific immune response and/or undergoing pharmacological treatment [35]. For example, asthma treatment usually involves the use of bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids which have shown to suppress coronavirus replication and cytokine production in in-vitro models [36,37]. Overall, the relationship of COVID-19 severity with specific respiratory diseases, besides COPD, (e.g. asthma, pulmonary TB pulmonary fibrosis, etc.) and their causal mechanisms require further investigation.

Severe COVID-19 outcomes were significantly associated with current and former smoking. It is suggested that smoking may play a role in angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) modulation [38], which is the reported host receptor of the virus responsible for COVID-19 [39,40]. A dose-dependent increase in ACE2 expression according to smoke exposure was found in rodent and human lungs [41]. Although incidence of COVID-19 appear to be lower in patients with smoking history [18,29], smoking seems to be associated with worse outcomes. A recent publication suggested that smokers susceptibility to severe SARS-CoV-2 infections could be at least partially explained by the response of ACE2 expression to inflammatory signaling, which can be upregulated by viral infections [41]. Furthermore, increased ACE2 expression has been observed in COPD which is a respiratory disease strongly associated with prior cigarette exposure and severe COVID-19 outcomes [41]. However, additional studies will be required to clarify the association of smoking, COPD and ACE2 levels on the clinical course of COVID-19. Results of this study differed from a previous meta-analysis concluding that active smoking does not apparently seem to be significantly associated with enhanced risk of progression towards severe disease outcomes in COVID-19 [9]. Discrepancy in the conclusions of the meta-analyses could be due to the large number of studies identified (5 vs 13) in this review, some of them with larger sample sizes.

It is important to note that in this study former and current smoking were associated with severe COVID-19 outcomes. This aligns with existing evidence suggesting that all levels of smoking including the exposure of former smokers and low-intensity current smokers are likely to be associated with lasting and progressive lung damage [42]. Pooled analysis showed higher odds of severe COVID-19 outcomes in former smokers compared with current smokers. It is possible that differences in the strength of association may be explained by: 1) the characteristics of the studies such as data collected (e.g. variables definition and time elapsed since the person quitted smoking); 2) the number of studies (4 vs 13) and sample sizes included; 3) specific immune responses in former and current smokers, and/or 4) the group of former smokers could be comprised of patients with more advanced COPD than the current smokers.

4.1. Implications and considerations

Results suggested that underlying respiratory diseases, specifically COPD, and smoking increase the odds of having severe COVID-19 outcomes. This is an important finding considering the high prevalence of COPD and smoking worldwide and the rapid spread of SARS-CoV-2. Results of this study may support the development of preventive interventions including patients and healthcare providers education, and contribute to improvements in the assessment and management of patient risk factors in clinical practice, all leading to the mitigation of severe outcomes in patients with COVID-19 infection. From the public health perspective, these findings may have implications on policy development and potential resourcing for respiratory diseases such as COPD. Furthermore, smoking cessation programming and efforts should be augmented given the association between severe COVID-19 outcomes and smoking. Future studies should assess the association of severe COVID-19 outcomes with the prevalence of respiratory diseases, other than COPD, as well as to explore the potential influence of their immune responses and undergoing pharmacological treatments. In addition, the association of severe COVID-19 outcomes with all level of smoking statuses and the causal mechanisms should be researched.

There are multiple factors to consider when interpreting these findings. First, there is limited information on respiratory diseases and smoking presented in the identified studies which prevents us from drawing further conclusions regarding the specific role of each risk factor in the development of severe COVID-19 outcomes. Evidence suggests that there is a close relationship between COPD, cigarette exposure and ACE2 modulation that could enhance the risk for developing severe COVID-19 outcomes, however, more research is needed to clarify this association. Second, the studies identified in this review were mostly conducted in China (95%). It is possible that factors such as prevalence of respiratory diseases and their treatment, among others, may be specific to the context. Therefore, the results of this study should be considered with caution and be re-evaluated as emerging literature from other countries become available. Third, there is a lack of information regarding variable definition during data collection which may influence the associations studied. Fourth, a high statistics heterogeneity was found in the pooled meta-analysis of current smokers and severe vs non-severe COVID-19 outcomes. This may be related to differences in data collection and sample size (25–6637) across the studies included in this part of the analysis. Statistics heterogeneity was not found in the other two pooled analyses (severe vs non-severe COVID-19 outcomes in respiratory disease and former smokers).

5. Conclusions

Results suggested that underlying respiratory diseases, specifically COPD, and smoking are associated with severe COVID-19 outcomes. These findings contribute to a better understanding of patient risk factors for severe COVID-19 which are valuable to support the development of preventive interventions and can help to improve the assessment and management of patient risk factors in clinical practice. Future studies should assess the association of severe COVID-19 outcomes with prevalence of other underlying respiratory diseases, other than COPD, as well as to explore the potential influence of their immune responses and undergoing pharmacological treatments. In addition, the association of severe COVID-19 with all level of smoking and the causal mechanisms should be the subject of future research.

Funding

None.

Contributions

DS conceived the idea for this paper and conducted the meta-analysis. DS and DM participated in the search and selection of literature, extracted key information from the studies identified, wrote and approved the final manuscript.

Financial support

N/A.

Declaration of competing interest

Authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Jhons Hopkins University of Medicine . Coronavirus Resource Center; 2020. COVID-19 Case Tracker.https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J., et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in wuhan, China. Jama. 2020;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu J., Ji P., Pang J., Zhong Z., Li H., He C., et al. Clinical characteristics of 3,062 COVID-19 patients: a meta-analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emami A., Javanmardi F., Pirbonyeh N., Akbari A. Prevalence of underlying diseases in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2020;8(1):e35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guan W.-J., Ni Z.-Y., Hu Y., Liang W.-H., Ou C.-Q., He J.-X., et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang J., Zheng Y., Gou X., Pu K., Chen Z., Guo Q., et al. Prevalence of comorbidities in the novel Wuhan coronavirus (COVID-19) infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;94:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vardavas C.I., Nikitara K. COVID-19 and smoking: a systematic review of the evidence. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2020;18:20. doi: 10.18332/tid/119324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lippi G., Henry B.M. Active smoking is not associated with severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2020;75:107–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forum of International Respiratory Societies . European Respiratory Society; Sheffield: 2017. The Global Impact of Respiratory Disease.https://www.who.int/gard/publications/The_Global_Impact_of_Respiratory_Disease.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Bank World Development Indicators (age-standardized prevalence of smoking) 2016. https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=2&series=SH.PRV.SMOK Available from:

- 12.Cao J., Tu W.-J., Cheng W., Yu L., Liu Y.-K., Hu X., et al. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America; 2020. Clinical Features and Short-Term Outcomes of 102 Patients with Corona Virus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen T., Dai Z., Mo P., Li X., Ma Z., Song S., et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of older patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China (2019): a single-centered, retrospective study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1093/gerona/glaa089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen T., Wu D., Chen H., Yan W., Yang D., Chen G., et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. Bmj. 2020;368:m1091. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng Y., Liu W., Liu K., Fang Y.Y., Shang J., Zhou L., et al. Clinical characteristics of fatal and recovered cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China: a retrospective study. Chin. Med. J. (Engl). 2020;133(11):1261–1267. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng Y., Ling Y., Bai T., Xie Y., Huang J., Li J., et al. COVID-19 with different severity: a multi-center study of clinical features. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020;201(11):1380–1388. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202002-0445OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guan W.-J., Liang W.-H., Zhao Y., Liang H.-R., Chen Z.-S., Li Y.-M., et al. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with covid-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Eur. Respir. J. 2020;55(5) doi: 10.1183/13993003.00547-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., Liang W.H., Ou C.Q., He J.X., et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet.395(10223):497-506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Ji D., Zhang D., Xu J., Chen Z., Yang T., Zhao P., et al. Prediction for progression risk in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia: the CALL score. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li K., Wu J., Wu F., Guo D., Chen L., Fang Z., et al. The clinical and chest CT features associated with severe and critical COVID-19 pneumonia. Invest. Radiol. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s41999-020-00356-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y.-K., Peng S., Li L.-Q., Wang Q., Ping W., Zhang N., et al. Clinical and transmission characteristics of covid-19 - a retrospective study of 25 cases from a single thoracic surgery department. Current medical science. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s11596-020-2176-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu W., Tao Z.W., Lei W., Ming-Li Y., Kui L., Ling Z., et al. Analysis of factors associated with disease outcomes in hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus disease. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020;133(9):1032–1038. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) COVID-19 Response Team. Preliminary estimates of the prevalence of selected underlying health conditions among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 - United States, february 12-march 28, 2020. MMWR–Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report.69(13):382-386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Wan S., Xiang Y., Fang W., Zheng Y., Li B., Hu Y., et al. Clinical features and treatment of COVID-19 patients in northeast Chongqing. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92(7):797–806. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang L., He W., Yu X., Hu D., Bao M., Liu H., et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 in elderly patients: characteristics and prognostic factors based on 4-week follow-up. J. Infect. 2020;80(6):639–645. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang X., Fang J., Zhu Y., Chen L., Ding F., Zhou R., et al. Clinical characteristics of non-critically ill patients with novel coronavirus infection (COVID-19) in a Fangcang Hospital. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020;26(8):1063–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang X., Yu Y., Xu J., Shu H., Xia J., Liu H., et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(5):475–481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang J.J., Dong X., Cao Y.Y., Yuan Y.D., Yang Y.B., Yan Y.Q., et al. 7th. Vol. 75. Allergy; 2020. pp. 1730–1741. (Clinical Characteristics of 140 Patients Infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang R., Ouyang H., Fu L., Wang S., Han J., Huang K., et al. CT features of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia according to clinical presentation: a retrospective analysis of 120 consecutive patients from Wuhan city. Eur. Radiol. 2020;30(8):4417–4426. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06854-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng F., Tang W., Li H., Huang Y.X., Xie Y.L., Zhou Z.G. Clinical characteristics of 161 cases of corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Changsha. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020;24(6):3404–3410. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202003_20711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z., et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diab N., Gershon A.S., Sin D.D., Tan W.C., Bourbeau J., Boulet L.P., et al. Underdiagnosis and overdiagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018;198(9):1130–1139. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201804-0621CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hangaard S., Helle T., Nielsen C., Hejlesen O.K. Causes of misdiagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic scoping review. Respir. Med. 2017;129:63–84. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2017.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halpin D.M.G., Faner R., Sibila O., Badia J.R., Agusti A. Do chronic respiratory diseases or their treatment affect the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection? Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(5):436–438. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30167-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsuyama S., Kawase M., Nao N., Shirato K., Ujike M., Kamitani W., et al. The inhaled corticosteroid ciclesonide blocks coronavirus RNA replication by targeting viral NSP15. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01648-20. 2020. 03.11.987016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamaya M., Nishimura H., Deng X., Sugawara M., Watanabe O., Nomura K., et al. Inhibitory effects of glycopyrronium, formoterol, and budesonide on coronavirus HCoV-229E replication and cytokine production by primary cultures of human nasal and tracheal epithelial cells. Respir Investig. 2020;58(3):155–168. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2019.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yilin Z., Yandong N., Faguang J. Role of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and ACE2 in a rat model of smoke inhalation induced acute respiratory distress syndrome. Burns. 2015;41(7):1468–1477. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang H., Penninger J.M., Li Y., Zhong N., Slutsky A.S. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as a SARS-CoV-2 receptor: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic target. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(4):586–590. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05985-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perrotta F., Matera M.G., Cazzola M., Bianco A. Severe respiratory SARS-CoV2 infection: does ACE2 receptor matter? Respir. Med. 2020;168:105996. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2020.105996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith J.C., Sausville E.L., Girish V., Yuan M.L., Vasudevan A., John K.M., et al. Cigarette smoke exposure and inflammatory signaling increase the expression of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 in the respiratory tract. Dev. Cell. 2020;53(5):514–529. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2020.05.012. e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oelsner E.C., Balte P.P., Bhatt S.P., Cassano P.A., Couper D., Folsom A.R., et al. Lung function decline in former smokers and low-intensity current smokers: a secondary data analysis of the NHLBI Pooled Cohorts Study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(1):34–44. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30276-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]