Abstract

This cohort study investigates mood homeostasis in Dutch students before and during the coronavirus disease 2019 lockdown.

The impact of lockdowns implemented in response to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on mental health has raised concerns.1,2 Understanding the mechanisms underlying this impact to mitigate it is a research priority.3 We hypothesized that one mechanism involves impaired mood homeostasis (ie, failure to stabilize mood via mood-modifying activities).4

Methods

Participants gave written informed consent. The study was approved by the ethics board of Leiden University. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

In this cohort study, Dutch students reported their mood and activities via ecological momentary assessment 4 times every day between March 16 and 29, 2020.5 On March 23, the government announced new and immediate lockdown measures. The average change in mood associated with each activity (ie, the activity’s pleasantness) was recorded for each individual. Mood homeostasis was defined as the extent to which participants preferentially engaged in pleasant activities at time t +1 when their mood was low at time t, thereby stabilizing their mood. At study onset, participants’ history of mental illness was assessed with a 1-item screener. Linear regressions were used to assess the change in mood homeostasis from before to during lockdown and whether this change was associated with mood changes or changes in the range of undertaken activities and whether this change was moderated by mental illness history. Using simulations, we estimated the potential association of changes in mood homeostasis with the risk of depression (eMethods in the Supplement). Statistical significance was tested using t tests except for the presence of nonzero 3-way interactions (tested using analysis of variance and corresponding F test) and the mediation analysis (tested using a z test). Statistical significance was set at a 2-sided P value less than .05. Analyses were performed using R version 3.4.3 (The R Foundation). The eMethods in the Supplement provides methodological details.

Results

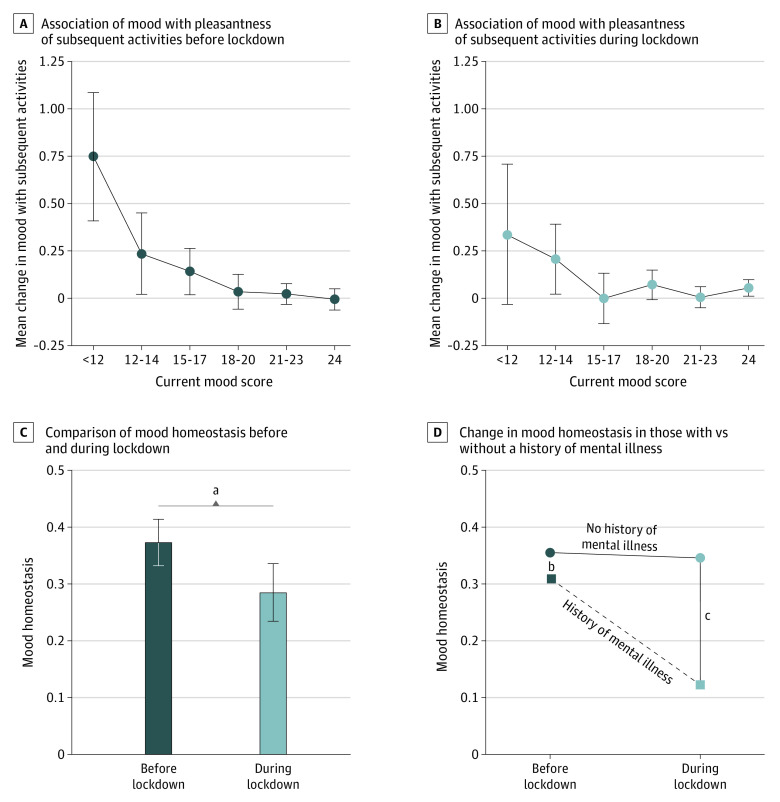

A total of 78 students were included in this study. Of these, 59 (76%) were female, and the mean (SD) age was 20.4 (3.7) years (Table). Mean (SE) mood homeostasis was significantly higher before than during lockdown (0.37 [0.02] vs 0.28 [0.03]; mean difference, 0.09; 95% CI, 0.03 to 0.15; P = .003) (Figure, A-C). Before lockdown, participants’ mood score was inversely proportional to the pleasantness of activities that they later engaged in (Figure, A). When participants’ mood was particularly low, they tended to later engage in activities that consistently increased their mood by a mean (SD) score of 0.75 (1.59). By contrast, during lockdown, if mood was particularly low, participants engaged in activities that increased their mood by a mean (SD) score of 0.34 (1.08) but could also further decrease their mood (Figure, B).

Table. Sample Demographic Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Total, No. | 78 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 18 (23) |

| Female | 59 (76) |

| Other | 1 (1) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 20.4 (3.7) |

| Mental illness | |

| Reported a history of mental illness | 16 (21) |

| Depression | 10 (13) |

| Bipolar disorder | 1 (1) |

| Anxiety | 8 (10) |

| Antidepressant medication use | 8 (10) |

| Attention-deficit disorder | 1 (1) |

| Reported no history of mental illness | 58 (74) |

| Preferred not to answer | 4 (5) |

| Pairs of observations (compliance), No./total No. (%)a | |

| Before lockdown | 1427/1638 (87.1) |

| During lockdown | 1423/1638 (86.9) |

Because participants provided up to 4 records every day for 7 days before and 7 days during lockdown, a maximum of 3 pairs of observations acquired consecutively on the same day were available for each participant for each day.

Figure. Mood Homeostasis Before and During Lockdown.

Association between mood at one time point and the pleasantness of the activities at the next time point (ie, how much participants engaged in activities that tended to increase their mood at the next time point) before (A) and during (B) the lockdown due to coronavirus disease 2019. C, Mood homeostasis was significantly lower during compared with before the lockdown. D, The change in mood homeostasis was significantly larger among participants with a history of mental illness compared with those without. Mood scores were collected using ecological momentary assessment 4 times every day over 14 days. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

aP = .003.

bP = .37.

cP < .001.

For every 0.1-point decrease in mood homeostasis, average mood decreased by 1.9 points (95% CI, 1.3 to 3.6; P < .001)—enough to change someone’s mean mood score from the population’s average to its bottom quartile. The change in mood homeostasis from before to during lockdown was associated with a reduction in the range of activities (proportion of mediation, 11.9%; indirect path, −0.012; 95% CI, −0.018 to −0.005; P < .001).

Mean (SE) mood homeostasis decreased significantly more among people with vs without a history of mental illness (F2,2636 = 8.15; P < .001), changing from similar values before lockdown (history of mental illness, 0.31 [0.05]; no history of mental illness, 0.36 [0.02]; mean difference, 0.05, 95% CI, −0.05 to 0.14; P = .37) to significantly different values during lockdown (history of mental illness, 0.13 [0.05]; no history of mental illness, 0.35 [0.03]; mean difference, 0.22; 95% CI, 0.11 to 0.33; P < .001). Dynamic simulations revealed that lower mood homeostasis associated with the lockdown could increase the risk of depressed mood episodes compared with participants’ baseline incidence (before lockdown: mean yearly incidence, 9.0%; 95% CI, 6.6-11.4; during lockdown: mean yearly incidence, 28.2%; 95% CI, 23.6-32.6).

Discussion

In this study, mood homeostasis appeared to decrease during lockdown due to COVID-19, and larger decreases were associated with larger decreases in mood. The association was larger for vulnerable people with a history of mental illness. The lack of a control condition (due to the nationwide implementation of the lockdown), the retrospective assessment of mood (over 3 hours), and the lack of positive affect measurements are the main limitations of our study. Nevertheless, because the same participants were monitored throughout, the lockdown itself seems to be the most likely explanation for the observed difference. How mood homeostasis changes with interventions could provide a fruitful avenue to mitigate the impact of the pandemic on mental health.

eMethods.

References

- 1.Reger MA, Stanley IH, Joiner TE. Suicide mortality and coronavirus disease 2019—a perfect storm? JAMA Psychiatry. Published online April 10, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak. Accessed May 6, 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331490/WHO-2019-nCoV-MentalHealth-2020.1-eng.pdf

- 3.Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VH, et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6):547-560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taquet M, Quoidbach J, Gross JJ, Saunders KEA, Goodwin GM. Mood homeostasis, low mood, and history of depression in 2 large population samples. JAMA Psychiatry. Published online April 22, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fried EI, Papanikolaou F, Epskamp S. Mental health and social contact during the COVID-19 pandemic: an ecological momentary assessment study. PsyArXiv. Preprint posted online April 24, 2020. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/36xkp [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods.