Key Points

Question

Is stress cardiac magnetic resonance imaging able to reclassify risk in patients with suspected coronary artery disease, across American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guideline–based risk categories?

Findings

In a multicenter cohort study of 1698 consecutive patients (median follow-up, 5.4 years) without a history of coronary artery disease, stress cardiac magnetic resonance imaging was performed for evaluation of suspected coronary artery disease. Stress cardiac magnetic resonance imaging significantly reclassified patient risk for cardiovascular death and myocardial infarction across American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guideline–based risk categories.

Meaning

The findings of this study suggest that, in patients with suspected coronary artery disease, stress cardiac magnetic resonance imaging may provide incremental prognostic value for cardiovascular death and myocardial infarction and aid in clinical decision-making by reclassifying a substantial proportion of patients at intermediate risk.

Abstract

Importance

The role of stress cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging in clinical decision-making by reclassification of risk across American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guideline–recommended categories has not been established.

Objective

To examine the utility of stress CMR imaging for risk reclassification in patients without a history of coronary artery disease (CAD) who presented with suspected myocardial ischemia.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A retrospective, multicenter cohort study with median follow-up of 5.4 years (interquartile range, 4.6-6.9) was conducted at 13 centers across 11 US states. Participants included 1698 consecutive patients aged 35 to 85 years with 2 or more coronary risk factors but no history of CAD who presented with suspected myocardial ischemia to undergo stress CMR imaging. The study was conducted from February 18, 2019, to March 1, 2020.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Cardiovascular (CV) death and nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI). Major adverse CV events (MACE) including CV death, nonfatal MI, hospitalization for heart failure or unstable angina, and late, unplanned coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

Results

Of the 1698 patients, 873 were men (51.4%); mean (SD) age was 62 (11) years, accounting for 67 CV death/nonfatal MIs and 190 MACE. Clinical models of pretest risk were constructed and patients were categorized using guideline-based categories of low (<1% per year), intermediate (1%-3% per year), and high (>3% year) risk. Stress CMR imaging provided risk reclassification across all baseline models. For CV death/nonfatal MI, adding stress CMR-assessed left ventricular ejection fraction, presence of ischemia, and late gadolinium enhancement to a model incorporating the validated CAD Consortium score, hypertension, smoking, and diabetes provided significant net reclassification improvement of 0.266 (95% CI, 0.091-0.441) and C statistic improvement of 0.086 (95% CI, 0.022-0.149). Stress CMR imaging reclassified 60.3% of patients in the intermediate pretest risk category (52.4% reclassified as low risk and 7.9% as high risk) with corresponding changes in the observed event rates of 0.6% per year for low posttest risk and 4.9% per year for high posttest risk. For MACE, stress CMR imaging further provided significant net reclassification improvement (0.361; 95% CI, 0.255-0.468) and C statistic improvement (0.092; 95% CI, 0.054-0.131), and reclassified 59.9% of patients in the intermediate pretest risk group (48.7% reclassified as low risk and 11.2% as high risk).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this multicenter cohort of patients with no history of CAD presenting with suspected myocardial ischemia, stress CMR imaging reclassified patient risk across guideline-based risk categories, beyond clinical risk factors. The findings of this study support the value of stress CMR imaging for clinical decision-making, especially in patients at intermediate risk for CV death and nonfatal MI.

This cohort study examines the use of stress cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in reclassification of risk for cardiovascular death and nonfatal myocardial infarction in patients with suspected myocardial ischemia.

Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is the leading cause of death and disability worldwide. In the US alone, more than 700 000 patients develop a new myocardial infarction (MI) each year, leading to a high burden of heart failure and mortality.1 Furthermore, between 2015 and 2030, health care costs associated with CAD are projected to double, making the evaluation of the clinical use and performance of diagnostic strategies more relevant.1 Stress cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging has been reported in numerous studies to be valuable and cost-effective in CAD diagnosis and risk stratification of cardiac events.2,3,4,5,6 Nevertheless, stress CMR imaging is underused in the US, representing less than 0.1% of all imaging tests used in 2018.7 In addition, to our knowledge, the role of stress CMR imaging in clinical decision-making by appropriate reclassification of cardiac risk across guideline-recommended categories has so far not been established in a multicenter setting in the US.

The Stress CMR Perfusion Imaging in the United States study of the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Registry is a multicenter study, specifically designed to evaluate the long-term performance of stress CMR imaging in risk stratification of patients presenting with suspicion of myocardial ischemia.8 In the present study, using validated risk reclassification methods,9,10 we sought to investigate whether stress CMR imaging provides net reclassification improvement (NRI) across cardiac risk categories recommended by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines11,12 in a multicenter cohort of patients with no history of CAD.

Methods

Population and Design

The patient population, design, and rationale of the retrospective, multicenter Stress CMR Perfusion Imaging in the United States study have been described previously.8 Stress CMR Perfusion Imaging in the United States aimed to evaluate the long-term prognostic value of stress CMR perfusion imaging in consecutive patients with suspected myocardial ischemia, who are at intermediate pretest likelihood of CAD. Inclusion criteria were (1) age between 35 and 85 years at the time of stress CMR imaging; (2) referral for evaluation of chest pain, dyspnea, abnormal electrocardiographic findings, or other clinical presentation that raised a suspicion of myocardial ischemia as determined by the treating clinician; and (3) presence of 2 or more coronary risk factors including age older than 50 years for men or older than 60 years for women, diabetes requiring treatment, chronic hypertension requiring treatment, hypercholesterolemia requiring treatment, family history of premature CAD (first-degree male relative aged ≤55 years or first-degree female relative aged ≤65 years), body mass index greater than or equal to 30 (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), and peripheral vascular disease.

Exclusion criteria in the present analysis were history of CAD (including percutaneous coronary intervention, MI, or coronary artery bypass graft), severe-grade valvular heart disease, nonischemic cardiomyopathy with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) less than 40%, infiltrative or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, constrictive pericarditis, active pregnancy, competing medical illnesses with expected survival less than 2 years, and known inability to follow-up. Vasodilator stress agents included intravenous infusion of adenosine, dipyridamole, or a bolus dose of regadenoson.

At each participating site, local institutional review board approval was obtained to conduct the study with a waiver of written informed consent. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cohort studies.

An enrolling center was required to (1) have a clinical vasodilator stress CMR perfusion imaging program ongoing for at least 10 years; (2) contribute between 100 and 500 consecutive patients who underwent a stress CMR imaging study between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2013, so that at least 4 years of clinical follow-up could be achieved at study conclusion for each patient; (3) have access to electronic medical records; (4) have all stress CMR imaging scans interpreted by a level II/III reader, with at least a level III supervising reader; and (5) have performed stress CMR imaging studies using either a 1.5-T or 3-T scanner and pulse sequences for stress perfusion, cine, and late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) imaging.

Data Collection and Outcomes

Collected clinical variables included patient demographic and clinical characteristics. The stress CMR imaging parameters included left ventricular volumes and dimensions, stress perfusion, and LGE using the AHA 17 segment model. A stress perfusion defect was considered present if it was densest in the endocardium with a transmural gradient across the wall thickness, persisted beyond peak myocardial enhancement for several R-R intervals on electrocardiogram, and conformed to a coronary arterial distribution. Inducible ischemia was defined as the presence of a stress perfusion defect in the absence of matching LGE in 1 or more segments. Myocardial infarction was defined as the presence of LGE conforming to infarction in 1 or more segments. For quality assurance, each center randomly selected 10% of its stress CMR imaging studies and submitted the images for blinded interpretation by the stress CMR imaging core laboratory at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, to evaluate core laboratory vs center agreement.

All centers were instructed to obtain clinical follow-up data on patients for at least 4 years after the index stress CMR imaging. Clinical follow-up used both electronic medical records and direct patient contact with either a standardized checklist questionnaire or scripted telephone interview. The outcome of interest was cardiovascular (CV) death or nonfatal MI. The prespecified secondary outcome was major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), defined as a composite of CV death, nonfatal MI, hospitalization for unstable angina or congestive heart failure, and late (>6 months after the index stress CMR imaging) unplanned coronary artery bypass graft. Postprocedural MI13 after coronary revascularization was not included as an outcome, given its limited association with downstream hard cardiac events14 and its propensity to create a bias escalating an unfavorable outcome pattern in patients referred for invasive coronary revascularization after stress CMR imaging. For either CV death/nonfatal MI or MACE, only the first event was counted when multiple events occurred in the same patient. Successful follow-up was defined as achieving an assessment of all outcome events for 4 years or longer after the index CMR.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed from February 18, 2019, to March 1, 2020. Baseline demographic and clinical variables were compared using the χ2 test for categorical variables and the t test or Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables, depending on the distribution. Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess the association between CMR-assessed ischemia and LGE with outcomes. Kaplan-Meier curves were generated by plotting cumulative incidence of CV death/nonfatal MI and MACE by years of follow-up and compared using a log-rank test.

To assess patients’ baseline (pretest) risk, we constructed 2 multivariable clinical risk models for the study outcomes. Model 1 included the validated CAD Consortium score (range, 0%-100%), which assesses the pretest probability for presence of hemodynamically obstructive CAD based on age, sex, and type of chest pain (typical, atypical, or nonspecific).15,16 This model is supported in the current ACC/AHA and European guidelines on CAD11,12,17 and was considered to reflect a common clinical decision pathway where downstream noninvasive diagnostic tests are ordered at the time of the first visit on the basis of medical history alone.16,18 Model 2 used a stepwise forward Cox regression strategy to select the strongest parsimonious set of clinical covariates for CV death/nonfatal MI, considering all clinical covariates with greater than 90% nonmissing data and a P value <.10 on univariable screening. Model 2 included the CAD Consortium score, history of hypertension, significant smoking (>10 pack-years), and diabetes. Then, adding CMR-assessed LVEF, presence of LGE, and ischemia to those models allowed us to assess posttest risk. The discriminative capacity of each model was determined according to the Harrell C statistic at baseline and after addition of CMR-assessed LVEF, presence of LGE, and ischemia.

According to ACC/AHA guidelines in stable CAD, “patients with a predicted annual CV death or nonfatal MI rate of less than 1%, 1% to 3%, and more than 3% per year are considered to be at low, intermediate, and high risk with implications to treatment planning.”11(p389)12(p2222) After assessing baseline (pretest) risk categories for all patients, we derived the magnitude of risk reclassification by adding CMR-assessed LVEF, presence of LGE, and ischemia (posttest) into each of the 2 baseline models. Since the ratio of observed MACE to CV death/nonfatal MI in the cohort was close to 2:1, we used a conversion factor of ×2, as previously proposed,19 to derive risk categories for MACE at less than 2%, 2% to 6%, and greater than 6% annually. Along with the original NRI,20 we further calculated (1) the NRI at event rate21; (2) the weighted NRI,22 which accounts for reclassifications across 2 or more categories; (3) the clinical NRI,23 referring to the NRI in the intermediate risk category; and (4) the category-free integrated discrimination improvement.20,24 All statistical analyses were performed with the use of SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc). A 2-tailed P value <.05 was considered significant.

Results

Of the total 2349 patients in the Stress CMR Perfusion Imaging in the United States study, 1698 patients had no history of CAD and formed the present study cohort. Of these, 873 patients were men (51.4%); mean (SD) age was 62 (11) years. A total of 1663 patients (97.9%) achieved the prespecified target follow-up of at least 4 years; the median follow-up was 5.4 years (interquartile range [IQR], 4.6-6.9). Cardiovascular death/nonfatal MI occurred in 67 of 1698 patients (3.9%), and MACE occurred in 190 patients (11.2%). Baseline clinical and stress CMR imaging characteristics according to the presence of CMR-assessed LGE or ischemia are presented in Table 1. Patients with vs without CMR-assessed LGE or ischemia had a higher prevalence of CV risk factors (median, 3; IQR, 2-4 vs 3; IQR, 2-3; P < .01), higher rates of CV treatment (eg, aspirin, 221 [56.0%] vs 577 [44.6%]; P<.01), lower LVEF (57.5%; IQR, 45.3%-66.7% vs 64.7%; IQR, 57.0%-70.9%; P < .01), higher left-ventricular end-diastolic volume indexed (71.1 mL/m2; IQR, 58.0-87.8 vs 60.9 mL/m2; IQR, 48.4-74.6 mL/m2; P < .01), and higher left-ventricular end-systolic volume indexed (27.5 mL/m2; IQR, 20.2-43.0 vs 20.8 mL/m2; IQR, 15.1-28.7; P < .01). Among 1698 patients, 227 (13.4%) tested positive for ischemia on stress CMR imaging. Among the 126 of 227 patients (55.5%) with 2 or more ischemic segments, 82 patients (65.1%) had a coronary angiogram and 59 of 82 of those patients (72.0%) underwent revascularization.

Table 1. Baseline Clinical and Stress CMR Characteristics .

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 1698) | Ischemia or LGE | |||

| No (n = 1299) | Yes (n = 399) | |||

| Clinical parameters | ||||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 62.4 (16.5) | 62.2 (16.6) | 63.3 (15.8) | .048 |

| Men | 873 (51.4) | 707 (54.4) | 166 (41.6) | <.01 |

| Hypertension | 1306 (76.9) | 963 (74.1) | 343 (86) | <.01 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 1096 (64.5) | 814 (62.7) | 282 (70.7) | <.01 |

| Diabetes | 446 (26.3) | 321 (24.7) | 125 (31.3) | <.01 |

| Smoking | 522 (30.9) | 372 (28.8) | 150 (37.8) | <.01 |

| CV risk factors, median (IQR) | 3 (2) | 3 (1) | 3 (2) | <.01 |

| CAD Consortium score, median (IQR)a | 10.4 (14.3) | 9.9 (13.1) | 14.4 (17.3) | <.01 |

| CV medications | ||||

| Aspirin | 798 (47) | 577 (44.6) | 221 (56.0) | <.01 |

| Statin | 883 (52) | 653 (50.3) | 230 (57.6) | .01 |

| β-Blocker | 732 (43.1) | 511 (39.3) | 221 (55.4) | <.01 |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB | 802 (47.3) | 574 (44.2) | 228 (57.1) | <.01 |

| Diuretic | 506 (29.8) | 349 (26.9) | 157 (39.3) | <.01 |

| Stress CMR imaging | ||||

| LVEF, median (IQR), % | 63.4 (15.2) | 64.7 (13.9) | 57.5 (21.4) | <.01 |

| LVEDVi, median (IQR), mL/m2 | 63.1 (27.3) | 60.9 (26.2) | 71.1 (29.8) | <.01 |

| LVESVi, median (IQR), mL/m2 | 22.0 (15.4) | 20.8 (13.6) | 27.5 (22.8) | <.01 |

| Presence of ischemia | 227 (13.4) | 0 (0) | 227 (13.4) | <.01 |

| Presence of LGE | 259 (15.3) | 0 (0) | 259 (15.3) | <.01 |

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; CAD, coronary artery disease; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; CV, cardiovascular; IQR, interquartile range; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LVEDVi, left ventricular end-diastolic volume indexed; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESVi, left ventricular end-systolic volume indexed.

The CAD Consortium score assesses the pretest probability for presence of hemodynamically obstructive CAD based on age, sex, and type of chest pain (typical, atypical, or nonspecific). Possible score range is 0% to 100%.

Univariate and multivariate associations of clinical and stress CMR imaging parameters with CV death/nonfatal MI are summarized in Table 2. In both univariate and multivariate analyses, CMR-assessed LVEF and presence of ischemia were significant estimators of outcomes (Table 2; eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Associations of Clinical and Stress CMR Parameters With CV Death and Nonfatal MIa.

| CV death and nonfatal MI | Univariate analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | Model 1b | Model 2c | Model 1 + CMRb | Model 2 + CMRc | ||||||||

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | ||||||

| CAD Consortium scored | 1.02 (1.01-1.04) | <.01 | 1.02 (1.01-1.04) | <.01 | 1.02 (1.01-1.04) | <.01 | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) | .02 | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) | .02 | |||

| Hypertension | 2.54 (1.16-5.56) | .02 | NA | NA | 2.30 (1.05-5.06) | .04 | NA | NA | 2.04 (0.93-4.55) | .07 | |||

| Diabetes | 1.69 (1.03-2.76) | .04 | NA | NA | 1.58 (0.96-2.59) | .07 | NA | NA | 1.55 (0.92-2.60) | .10 | |||

| Smoking | 1.92 (1.18-3.12) | <.01 | NA | NA | 1.83 (1.12-2.97) | .02 | NA | NA | 1.91 (1.16-3.16) | .01 | |||

| LVEF, per 5% | 0.81 (0.76-0.87) | <.01 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.84 (0.78-0.91) | <.01 | 0.84 (0.77-0.91) | <.01 | |||

| Presence of LGE | 3.49 (2.13-5.73) | <.01 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.45 (0.73-2.48) | .22 | 1.34 (0.74-2.42) | .33 | |||

| Presence of ischemia | 3.80 (2.31-6.27) | <.01 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2.45 (1.40-4.29) | <.01 | 2.21 (1.25-3.92) | <.01 | |||

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; CV, cardiovascular; HR, hazard ratio: LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; NA, not applicable.

Statistical analysis by Cox proportional hazards.

Adjusted for CAD Consortium score.

Adjusted for CAD Consortium score, hypertension, diabetes, and smoking.

The CAD Consortium score assesses the pretest probability for presence of hemodynamically obstructive CAD based on age, sex, and type of chest pain (typical, atypical, or nonspecific). Possible score range is 0% to 100%.

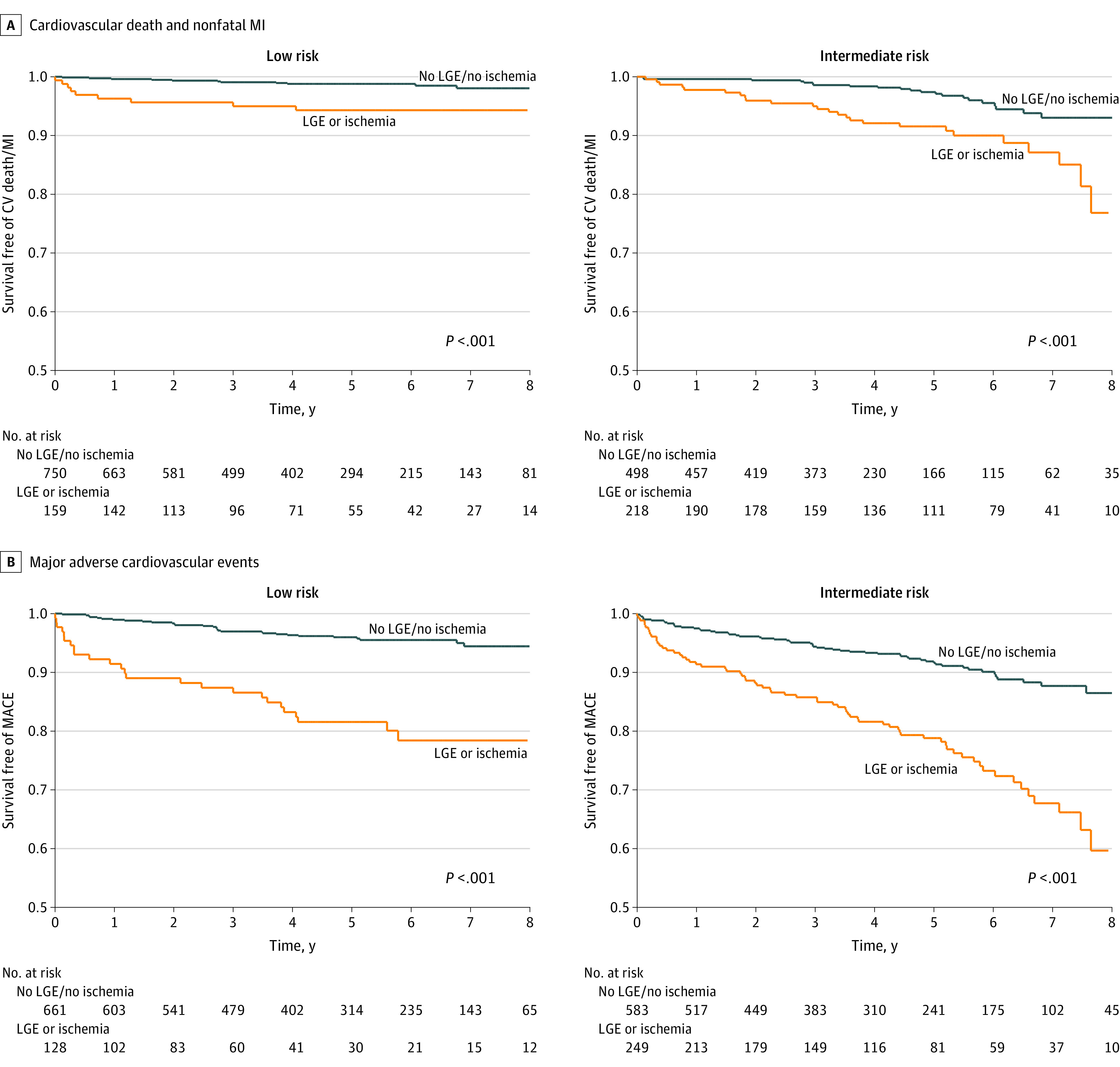

Based on the ACC/AHA guideline–recommended annualized risk categories for CV death/nonfatal MI, patients were categorized according to model 2 as having low (n = 909), intermediate (n = 716), or high (n = 12) baseline (pretest) risk. In Kaplan-Meier analysis, patients at low or intermediate baseline risk with the presence of either ischemia or LGE experienced a substantial decrease in event-free survival compared with patients with absence of both ischemia and LGE, both for CV death/nonfatal MI and MACE (Figure 1). Patients with absence of both ischemia and LGE experienced low annual rates of CV death/nonfatal MI compared with patients with ischemia, LGE, or both in the whole cohort (0.4% vs 1.7% per year, P < .01), the low (0.2% vs 1.0% per year, P < .01), and the intermediate (0.7% vs 2.1% per year, P < .01) pretest risk group. Similarly, MACE rates for patients with absence of both ischemia and LGE vs MACE rates in patients with ischemia, LGE, or both were 1.3% vs 5.0% per year in the whole cohort, 0.8% vs 3.9% per year in the low pretest risk cohort, and 1.9% vs 5.4% per year in the intermediate pretest risk group (P < .01 for all).

Figure 1. Time-to-Event Curves.

A, Time-to-event curves for cardiovascular (CV) death and nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) stratified by the absence of late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) and ischemia vs the presence of LGE or ischemia in patients with low and intermediate pretest probability for CV death and nonfatal MI. B, Time-to-event curves for major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) stratified by the absence of LGE and ischemia vs the presence of LGE or ischemia in patients with low and intermediate pretest probability for MACE.

We further determined the discriminative capacity of the prediction models as assessed by the C statistic. For CV death/nonfatal MI, we observed baseline C statistic values of 0.622 (95% CI, 0.553-0.690) for model 1 and 0.659 (95% CI, 0.585-0.734) for model 2. Addition of CMR–assessed LVEF, presence of LGE, and ischemia significantly improved the C statistic to 0.731 (95% CI, 0.661-0.801; C statistic improvement for model 1: 0.109; 95% CI, 0.035-0.211) and 0.745 (95% CI, 0.676-0.813; C statistic improvement for model 2: 0.086; 95% CI, 0.022-0.149). Regarding MACE, the addition of stress CMR imaging parameters significantly increased the C statistic from 0.595 (95% CI, 0.550-0.639) to 0.705 (95% CI, 0.664-0.746) for model 1 (C statistic improvement: 0.11; 95% CI, 0.06-0.16) and from 0.647 (95% CI, 0.605-0.689) to 0.739 (95% CI, 0.700-0.777) for model 2 (C statistic improvement: 0.092; 95% CI, 0.054-0.131) (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

The addition of stress CMR imaging parameters to each baseline model significantly improved reclassification metrics for both CV death/nonfatal MI and MACE (Table 3). Regarding CV death/nonfatal MI, we observed consistent improvements in reclassification metrics across both models 1 and 2. The addition of stress CMR–assessed LVEF, LGE, and ischemia to model 2 yielded an NRI of 0.266 (95% CI, 0.091-0.441), an NRI at event rate of 0.146 (95% CI, 0.035-0.257), and an integrated discrimination improvement of 0.042 (95% CI, 0.023-0.061). Similar results were obtained for MACE. Detailed reclassification tables for events and nonevents, together with assessment of the weighted NRI and positive and negative predictive values of each model at the event rate, are presented in eTables 2-6 in the Supplement.

Table 3. Reclassification for CV Death/Nonfatal MI and MACE, After Addition of CMR-Assessed LVEF, Late Gadolinium Enhancement, and Ischemia.

| Reclassification metric | CV death and nonfatal MI (95% CI) | MACE (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 vs model 1 with CMRa | Model 2 vs model 2 with CMRb | Model 1 vs model 1 with CMRa | Model 2 vs model 2 with CMRb | |

| NRI | 0.234 (0.061-0.407) | 0.266 (0.091-0.441) | 0.355 (0.247-0.463) | 0.361 (0.255-0.468) |

| Clinical NRI | 0.448 (0.381-0.515) | 0.521 (0.452-0.590) | 0.554 (0.491-0.617) | 0.517 (0.466-0.568) |

| NRI at event rate | 0.185 (0.044-0.326) | 0.146 (0.035-0.257) | 0.198 (0.112-0.284) | 0.144 (0.063-0.225) |

| IDI | 0.044 (0.025-0.063) | 0.042 (0.023-0.061) | 0.082 (0.061-0.104) | 0.076 (0.055-0.097) |

Abbreviations: CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; CV, cardiovascular; IDI, integrated discrimination improvement; LVEF, left-ventricular ejection fraction; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; NRI, net reclassification improvement.

Adjusted for CAD Consortium score, which assesses the pretest probability for presence of hemodynamically obstructive CAD based on age, sex, and type of chest pain (typical, atypical, or nonspecific). Possible score range is 0% to 100%.

Adjusted for CAD Consortium score, hypertension, diabetes, smoking.

Overall, stress CMR reclassified 33.5% (568 of 1698) of the overall cohort to a more appropriate posttest risk group for CV death and nonfatal MI. Risk reclassification showed the most substantial changes in patients at intermediate pretest risk. For CV death/nonfatal MI, stress CMR imaging reclassified 60.3% (432 of 716) of patients at intermediate pretest risk (52.4% reclassified to low risk, 7.9% to high risk) with corresponding changes in the observed event rates of 0.6% per year for low posttest risk and 4.9% per year for high posttest risk (Figure 2). Regarding MACE, stress CMR imaging reclassified 59.9% (498 of 832) of patients at intermediate pretest risk (48.7% reclassified to low risk, 11.2% to high risk), with corresponding changes in the observed event rates of 1.4% per year for low posttest risk and 9.5% per year for high posttest risk (eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Risk Reclassification Improvement for Cardiovascular (CV) Death and Nonfatal Myocardial Infarction (MI).

Stress cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) parameters were added to the multivariate baseline clinical risk model and risk reclassification was assessed across American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guideline categories of less than 1%, 1% to 3%, and greater than 3% annual event rates (A). Bar graphs depict the proportion of patients reclassified by the addition of CMR-assessed left ventricular ejection fraction, late gadolinium enhancement, and ischemia across pretest risk categories (B). Observed annualized rates of CV death and nonfatal MI for reclassified patients are displayed in bar graphs (C).

Comparable results were obtained for reclassification at the event rate. Overall, stress CMR similarly reclassified 30.9% (525 of 1698) of the study population to a more appropriate posttest risk category for CV death and nonfatal MI, across the event rate. For CV death/nonfatal MI, stress CMR imaging reclassified 14.4% of patients at below event rate pretest risk to above event rate posttest risk, with an observed event rate of 1.1% per year. In addition, stress CMR imaging reclassified 39.8% of patients at above event rate to below event rate posttest risk (observed event rate, 0.4% per year) (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). For MACE, stress CMR imaging reclassified 14.1% of patients at below event rate to above event rate posttest risk (observed event rate, 3.8% per year) and 45.5% of patients at above event rate to below event rate posttest risk (observed event rate, 1.3% per year) (eFigure 3 in the Supplement).

Discussion

The main finding of this study suggests that, in a multicenter cohort of patients without previous CAD who had suspected myocardial ischemia and at least 4 years of follow-up, stress CMR imaging can provide risk reclassification for CV death and nonfatal MI, incremental to established risk factors, across current ACC/AHA-recommended risk categories, especially for patients considered at intermediate risk. Those findings expand on previous work and support the value of stress CMR imaging for clinical decision-making in a current practice setting in the US.

In a large, diverse population of patients with known or suspected CAD, Heitner et al6 reported that stress CMR imaging was associated with all-cause mortality over a median follow-up of 5 years and improved risk reclassification for all-cause mortality with an NRI of 0.11 (95% CI, 0.07-0.14). Their findings are congruent with ours as well as with previous single-center studies.25,26 When considering the study event rate as threshold, stress CMR imaging also appeared to accurately shift patients into a more appropriate risk category, suggesting that reclassification of patients with suspected CAD is possible across different thresholds of risk, including at the event rate.

Despite considerable equipoise around the optimal management of CAD, there is general consensus that choice of treatment should be guided according to clinical likelihood of adverse outcomes.11,12,17 While care for patients deemed to be at low risk may be initially managed with guideline-based medical treatment alone, invasive coronary angiography with early revascularization should be reserved for high-risk patients.27 The second main finding of this study highlights the importance of appropriate reclassification of patients initially categorized in the intermediate-risk group where clinical uncertainty about optimal management is highest. In our study, stress CMR imaging appeared to show the highest NRI in intermediate-risk patients, reclassifying up to 60% of them to a different posttest risk category. This risk restratification was accompanied by meaningful changes in event rates with patients at low posttest CV risk presenting with 0.6% annual rates compared with those at high posttest risk experiencing 4.9% annual rates, substantially higher than the ACC/AHA proposed threshold of 3%. Reclassification of a significant portion of patients as low risk following stress CMR imaging entails clinical implications for prognosis, as well as for downstream procedures. Reclassification of patients as low risk may translate into less unnecessary invasive testing, especially in the US, where the diagnostic yield of coronary angiography for obstructive CAD remains as low as 41%.28

Third, with the exclusion of patients with previous CAD, our study population was at low-to-intermediate pretest risk for CV death and nonfatal MI, with an observed annual hard event rate of 0.7% (2.1% for MACE). Those observed rates for hard events resulted in classification of a large proportion of the study population as low risk (<1% per year) and are typical of contemporary cohorts of patients with suspected CAD. For comparison, in the landmark PROMISE29 and SCOT-HEART30 studies, which evaluated the use of coronary computed tomographic angiography in patients with chest pain, the annual rates for CV death and nonfatal MI were slightly lower, at 0.58% and 0.65%, respectively. In this patient population, stress CMR imaging reclassified one-third of the overall cohort to a more appropriate posttest risk category for CV death and nonfatal MI. Accounting for the event rate, stress CMR imaging similarly reclassified 31% of the cohort, suggesting robust patient risk stratification across different thresholds and, potentially, event rates.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, owing to its retrospective design, the study could not capture all of the confounding factors regarding the association between management decisions after the stress CMR imaging study and patient risks. Thus, our study could not quantify the outcomes of coronary revascularization incremental to medical therapy in patients with significant CMR-assessed ischemia. Second, we did not have data on stress CMR imaging segmental wall motion abnormality to investigate its incremental prognostic value in ischemia and infarction. However, we believe that this specific limitation for the key study findings involving CMR-assessed ischemia and LGE is minor, since perfusion defects during pharmacologic vasodilating stress are a more sensitive marker for ischemia than segmental wall motion31 and LGE imaging is a more accurate marker for subendocardial infarction.

Our study offers further evidence that stress CMR imaging may be well poised to assume the role of a gate-keeping noninvasive test, especially in patients in the low-to-intermediate pretest risk category for CV death and nonfatal MI. However, with only approximately 1% of our study cohort in the high pretest risk category for CV death and nonfatal MI, we lacked statistical power to assess risk reclassification by stress CMR imaging in the high-risk group; this outcome needs to be assessed in a future study. Yet, in patients with moderate-to-high pretest risk, the recent randomized clinical MR-INFORM trial demonstrated favorable guidance toward the use of coronary revascularization and noninferior prognosis for CV death and nonfatal MI when management was guided by stress CMR imaging compared with an invasive fractional flow reserve–based strategy.5

Conclusions

In a multicenter cohort of patients with no history of CAD presenting with suspected myocardial ischemia, stress CMR reclassified patient risk beyond clinical risk factors across established ACC/AHA risk categories. This reclassification was noted most in patients considered at intermediate pretest risk for CV death and nonfatal MI who experienced low event rates (0.6% per year) when reclassified by stress CMR imaging to a low posttest risk category, and relatively high event rates (4.9% per year) when reclassified to a high posttest risk category.

eTable 1. Univariate and Multivariate Associations of Clinical and Stress CMR Parameters With MACE and Model Discrimination Improvement

eTable 2. Net Reclassification Improvement From the Multivariate Baseline Clinical Risk Model (Pre-Test Risk) by Adding CMR-Assessed LVEF, Ischemia and Late Gadolinium Enhancement (Post-Test Risk) for CV Death and Nonfatal MI

eTable 3. Net Reclassification Improvement From the Multivariate Baseline Clinical Risk Model (Pre-Test Risk) by Adding CMR-Assessed LVEF, Ischemia and Late Gadolinium Enhancement (Post-Test Risk) for MACE

eTable 4. Positive and Negative Predictive Values for CV Death/Nonfatal MI and MACE at the Event Rate, Before and After the Addition of CMR-Assessed LVEF, Ischemia and Late Gadolinium Enhancement to the Baseline Models

eTable 5. Net Reclassification Improvement at the Event Rate, From the Multivariate Baseline Clinical Risk Model (Pre-Test Risk) by Adding CMR-Assessed LVEF, Ischemia and Late Gadolinium Enhancement (Post-Test Risk), for CV Death and Nonfatal MI

eTable 6. Net Reclassification Improvement at the Event Rate, From the Multivariate Baseline Clinical Risk Model (Pre-Test Risk) by Adding CMR-Assessed LVEF, Ischemia and Late Gadolinium Enhancement (Post-Test Risk), for MACE

eFigure 1. Risk Reclassification Improvement for MACE: CMR Parameters Were Added to the Multivariate Baseline Clinical Risk Model and Risk Reclassification Was Assessed Across Risk Categories of <2%, 2%-6%, >6% Annual Event Rates

eFigure 2. Risk Reclassification Improvement for CV Death and Nonfatal MI: CMR Parameters Were Added to the Multivariate Baseline Clinical Risk Model and Risk Reclassification Was Assessed at the Event Rate

eFigure 3. Risk Reclassification Improvement for MACE: CMR Parameters Were Added to the Multivariate Baseline Clinical Risk Model and Risk Reclassification Was Assessed at the Event Rate

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, et al. ; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart disease and stroke statistics—2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139(10):e56-e528. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenwood JP, Maredia N, Younger JF, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance and single-photon emission computed tomography for diagnosis of coronary heart disease (CE-MARC): a prospective trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9814):453-460. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61335-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah R, Heydari B, Coelho-Filho O, et al. Stress cardiac magnetic resonance imaging provides effective cardiac risk reclassification in patients with known or suspected stable coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2013;128(6):605-614. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vincenti G, Masci PG, Monney P, et al. Stress perfusion CMR in patients with known and suspected CAD: prognostic value and optimal ischemic threshold for revascularization. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(5):526-537. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagel E, Greenwood JP, McCann GP, et al. ; MR-INFORM Investigators . Magnetic resonance perfusion or fractional flow reserve in coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(25):2418-2428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heitner JF, Kim RJ, Kim HW, et al. Prognostic value of vasodilator stress cardiac magnetic resonance imaging: a multicenter study with 48 000 patient-years of follow-up. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(3):256-264. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.0035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Medicare provider utilization and payment data. Updated November 19, 2019. Accessed June 19, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Provider-Charge-Data/Physician-and-Other-Supplier

- 8.Kwong RY, Ge Y, Steel K, et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance stress perfusion imaging for evaluation of patients with chest pain. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(14):1741-1755. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.07.074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steyerberg EW, Vickers AJ, Cook NR, et al. Assessing the performance of prediction models: a framework for traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology. 2010;21(1):128-138. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c30fb2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB Sr, Demler OV. Novel metrics for evaluating improvement in discrimination: net reclassification and integrated discrimination improvement for normal variables and nested models. Stat Med. 2012;31(2):101-113. doi: 10.1002/sim.4348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, et al. ; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force . 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2012;126(25):e354-e471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel MR, Calhoon JH, Dehmer GJ, et al. ACC/AATS/AHA/ASE/ASNC/SCAI/SCCT/STS 2017 appropriate use criteria for coronary revascularization in patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(17):2212-2241. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. ; Executive Group on behalf of the Joint European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)/World Heart Federation (WHF) Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction . Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction 2018. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(18):2231-2264. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker NC, Lipinski MJ, Escarcega RO, et al. Definitions of periprocedural myocardial infarction as surrogates for catheterization laboratory quality or clinical trial end points. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113(8):1326-1330. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.01.408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Genders TS, Steyerberg EW, Hunink MG, et al. Prediction model to estimate presence of coronary artery disease: retrospective pooled analysis of existing cohorts. BMJ. 2012;344:e3485. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Genders TS, Steyerberg EW, Alkadhi H, et al. ; CAD Consortium . A clinical prediction rule for the diagnosis of coronary artery disease: validation, updating, and extension. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(11):1316-1330. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J.2020;41(3)407-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Jong MC, Genders TS, van Geuns RJ, Moelker A, Hunink MG. Diagnostic performance of stress myocardial perfusion imaging for coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. 2012;22(9):1881-1895. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2434-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leening MJ, Vedder MM, Witteman JC, Pencina MJ, Steyerberg EW. Net reclassification improvement: computation, interpretation, and controversies: a literature review and clinician’s guide. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(2):122-131. doi: 10.7326/M13-1522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Pencina KM, Janssens AC, Greenland P. Interpreting incremental value of markers added to risk prediction models. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176(6):473-481. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pencina MJ, Steyerberg EW, D’Agostino RB Sr. Net reclassification index at event rate: properties and relationships. Stat Med. 2017;36(28):4455-4467. doi: 10.1002/sim.7041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pencina KM, Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB Sr. What to expect from net reclassification improvement with three categories. Stat Med. 2014;33(28):4975-4987. doi: 10.1002/sim.6286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook NR. Comments on ‘Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: From area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond’ by M. J. Pencina et al., Statistics in Medicine (DOI: 10.1002/sim.2929). Stat Med. 2008;27(2):191-195. doi: 10.1002/sim.2987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cook NR. Quantifying the added value of new biomarkers: how and how not. Diagn Progn Res. 2018;2:14. doi: 10.1186/s41512-018-0037-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah RV, Heydari B, Coelho-Filho O, et al. Vasodilator stress perfusion CMR imaging is feasible and prognostic in obese patients. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7(5):462-472. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abbasi SA, Heydari B, Shah RV, et al. Risk stratification by regadenoson stress magnetic resonance imaging in patients with known or suspected coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114(8):1198-1203. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.07.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patel KK, Spertus JA, Chan PS, et al. Extent of myocardial ischemia on positron emission tomography and survival benefit with early revascularization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(13):1645-1654. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.07.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patel MR, Peterson ED, Dai D, et al. Low diagnostic yield of elective coronary angiography. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(10):886-895. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Douglas PS, Hoffmann U, Patel MR, et al. ; PROMISE Investigators . Outcomes of anatomical versus functional testing for coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(14):1291-1300. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1415516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newby DE, Adamson PD, Berry C, et al. ; SCOT-HEART Investigators . Coronary CT angiography and 5-year risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(10):924-933. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leong-Poi H, Rim SJ, Le DE, Fisher NG, Wei K, Kaul S. Perfusion versus function: the ischemic cascade in demand ischemia: implications of single-vessel versus multivessel stenosis. Circulation. 2002;105(8):987-992. doi: 10.1161/hc0802.104326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Univariate and Multivariate Associations of Clinical and Stress CMR Parameters With MACE and Model Discrimination Improvement

eTable 2. Net Reclassification Improvement From the Multivariate Baseline Clinical Risk Model (Pre-Test Risk) by Adding CMR-Assessed LVEF, Ischemia and Late Gadolinium Enhancement (Post-Test Risk) for CV Death and Nonfatal MI

eTable 3. Net Reclassification Improvement From the Multivariate Baseline Clinical Risk Model (Pre-Test Risk) by Adding CMR-Assessed LVEF, Ischemia and Late Gadolinium Enhancement (Post-Test Risk) for MACE

eTable 4. Positive and Negative Predictive Values for CV Death/Nonfatal MI and MACE at the Event Rate, Before and After the Addition of CMR-Assessed LVEF, Ischemia and Late Gadolinium Enhancement to the Baseline Models

eTable 5. Net Reclassification Improvement at the Event Rate, From the Multivariate Baseline Clinical Risk Model (Pre-Test Risk) by Adding CMR-Assessed LVEF, Ischemia and Late Gadolinium Enhancement (Post-Test Risk), for CV Death and Nonfatal MI

eTable 6. Net Reclassification Improvement at the Event Rate, From the Multivariate Baseline Clinical Risk Model (Pre-Test Risk) by Adding CMR-Assessed LVEF, Ischemia and Late Gadolinium Enhancement (Post-Test Risk), for MACE

eFigure 1. Risk Reclassification Improvement for MACE: CMR Parameters Were Added to the Multivariate Baseline Clinical Risk Model and Risk Reclassification Was Assessed Across Risk Categories of <2%, 2%-6%, >6% Annual Event Rates

eFigure 2. Risk Reclassification Improvement for CV Death and Nonfatal MI: CMR Parameters Were Added to the Multivariate Baseline Clinical Risk Model and Risk Reclassification Was Assessed at the Event Rate

eFigure 3. Risk Reclassification Improvement for MACE: CMR Parameters Were Added to the Multivariate Baseline Clinical Risk Model and Risk Reclassification Was Assessed at the Event Rate