This systematic review and meta-analysis assesses the performance of commercially available gene expression profile tests for prognosis of cutaneous melanoma in patients with stage I or stage II melanoma

Key Points

Question

What is the performance of commercially available gene expression profile tests in predicting cutaneous melanoma outcomes in patients with stage I or stage II melanoma?

Findings

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of 7 studies including 1450 participants, gene expression profile test performance varied significantly by disease stage in external validation studies and was better at identifying recurrence in patients with stage II disease than in those with stage I disease. Studies were rated as having moderate to high risk of bias, and the quality of evidence was assessed as low to very low.

Meaning

In patients with clinically localized melanoma, there was variation in gene expression profile test performance by disease stage, suggesting limited potential for clinical utility for patients with stage I melanoma.

Abstract

Importance

The performance of prognostic gene expression profile (GEP) tests for cutaneous melanoma is poorly characterized.

Objective

To systematically assess the performance of commercially available GEP tests in patients with American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage I or stage II disease.

Data Sources

For this systematic review and meta-analysis, comprehensive searches of PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, and Web of Science were conducted on December 12, 2019, for English-language studies of humans without date restrictions.

Study Selection

Two reviewers identified GEP external validation studies of patients with localized melanoma. After exclusion criteria were applied, 7 studies (8%; 5 assessing DecisionDx-Melanoma and 2 assessing MelaGenix) were included.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data were extracted using an adaptation of the Checklist for Critical Appraisal and Data Extraction for Systematic Reviews of Prediction Modeling Studies (CHARMS-PF). When feasible, meta-analysis using random-effects models was performed. Risk of bias and level of evidence were assessed with the Quality in Prognosis Studies tool and an adaptation of Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Proportion of patients with or without melanoma recurrence correctly classified by the GEP test as being at high or low risk.

Results

In the 7 included studies, a total of 1450 study participants contributed data (age and sex unknown). The performance of both GEP tests varied by AJCC stage. Of patients tested with DecisionDx-Melanoma, 623 had stage I disease (6 true-positive [TP], 15 false-negative, 61 false-positive, and 541 true-negative [TN] results) and 212 had stage II disease (59 TP, 13 FN, 78 FP, and 62 TN results). Among patients with recurrence, DecisionDx-Melanoma correctly classified 29% with stage I disease and 82% with stage II disease. Among patients without recurrence, the test correctly classified 90% with stage I disease and 44% with stage II disease. Of patients tested with MelaGenix, 88 had stage I disease (7 TP, 15 FN, 15 FP, and 51 TN results) and 245 had stage II disease (59 TP, 19 FN, 95 FP, and 72 TN results). Among patients with recurrence, MelaGenix correctly classified 32% with stage I disease and 76% with stage II disease. Among patients without recurrence, the test correctly classified 77% with stage I disease and 43% with stage II disease.

Conclusions and Relevance

The prognostic ability of GEP tests among patients with localized melanoma varied by AJCC stage and appeared to be poor at correctly identifying recurrence in patients with stage I disease, suggesting limited potential for clinical utility in these patients.

Introduction

Prognostic gene expression profiles (GEPs) of primary cutaneous melanoma are commercially available in the US (DecisionDx-Melanoma, Castle Biosciences Inc) and Europe (MelaGenix, NeraCare GmbH).1,2 Both tests aim to improve on current prognostic estimates3 by classifying patients as being at high or low risk for recurrence or metastasis.1,2

Studies have reported that GEP results are associated with various survival outcomes in mixed cohorts of patients with melanoma.4,5,6,7,8,9 Preliminary evidence suggests that the performance of these tests varies across the risk spectrum of melanoma.10 Analyses have also included patients outside the intended-use population (ie, metastatic melanoma) or from test development and internal validation cohorts. Despite these methodologic concerns, health care professionals are using GEP tests to inform patient care decisions, but the settings in which they have clinical utility are not clear. In the US, at least 12 000 DecisionDx-Melanoma tests are ordered per year despite the absence of any guidelines recommending their routine use.11 The National Comprehensive Cancer Network, version 2.2020, melanoma guidelines state that GEP tests “may provide information on individual risk of recurrence, as an adjunct to standard AJCC [American Joint Committee on Cancer] staging. However, the currently available prognostic molecular techniques should not replace pathologic staging procedures, and the use of GEP testing according to specific melanoma stage (before or after sentinel lymph node biopsy) requires further prospective investigation in large, contemporary data sets of unselected patients.”12(p1) The purpose of this study was to assess the performance of commercially available GEP prognostic tests in predicting survival outcomes in patients diagnosed with localized melanoma stratified by disease stage.

Methods

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of commercially available GEP tests for patients with cutaneous melanoma. The systematic review was conducted in accordance with a guideline for systematic reviews of prognostic factor studies13 and reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline.14 The study protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; CRD42019146778)15 (eAppendix in the Supplement).

Data Sources

A systematic search of PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, and Web of Science was conducted on December 12, 2019, without date restrictions (eMethods and eTable 1 in the Supplement). Titles and abstracts of search results were screened independently (A.Y. and L.M.). The full texts of the remaining results were assessed independently by another 2 of us (M.A.M. and E.K.B.) for inclusion based on predetermined criteria.

Study Selection

Studies were considered to be eligible if they (1) reported the performance of a commercially available GEP test for prognosis of AJCC 7th or 8th edition stage I or stage II melanoma, (2) were external validation studies (ie, no patients from development or internal validation), and (3) provided prespecified primary or secondary survival outcomes data. Studies were excluded if they (1) were a case report, review article, or letter; (2) included patients from test development and/or internal validation; (3) exclusively reported different outcomes; (4) exclusively reported outcomes on patients with AJCC stage III/IV melanoma; (5) were duplicates (ie, the same study); (6) were abstracts later published as articles; or (7) included fewer than 50 participants.

Data Extraction

Data were extracted independently (M.A.M. and E.K.B.) using a piloted form adapted from the Checklist for Critical Appraisal and Data Extraction for Systematic Reviews of Prediction Modeling Studies (CHARMS-PF).13 After initial data extraction was completed, emails were sent to study authors for missing data, as needed. Study authors were also contacted to obtain unpublished stage-specific data.

Assessment of Individual Study Risk of Bias

Risk of bias was assessed independently as high, moderate, or low (M.A.M. and E.K.B.) using the Quality in Prognosis Studies (QUIPS) tool.16,17 A study16 that satisfied low risk of bias in all 6 domains was designated as having low overall risk of bias. A study18 with a high risk of bias in 1 or more domains was designated as having high overall risk of bias. The quality of individual study reporting was assessed using the Reporting Recommendations for Tumor Marker Prognostic Studies (REMARK) checklist and informed the QUIPS assessments (eMethods in the Supplement).19

Outcomes

Prognostic outcomes (time to event) are best analyzed using hazard ratios in meta-analyses. However, few studies have reported hazard ratios by stage of disease. Therefore, our primary outcome was the relative proportion of patients with or without melanoma recurrence correctly classified by the GEP test as high or low risk stratified by AJCC stage. Although our primary outcome was similar in concept to sensitivity and specificity, sensitivity and specificity are more appropriately reported at a particular time point in prognostic studies20 or using semiparametric models,21 and neither was feasible (eMethods in the Supplement). Study outcomes were identified and end point data were extracted while maintaining consistency of definitions as much as possible. We considered melanoma recurrence and melanoma relapse to be synonymous. We did not aim to compare the performance of different GEP tests using statistical measures because of the known heterogeneity in study designs.

Secondary outcomes were (1) the same proportions as the primary outcome but for prediction of distant metastasis, melanoma-specific death, and death from any cause; (2) survival rates among patients with low-risk and high-risk GEP test scores; and (3) univariate or multivariate multiplicative effect estimates, each stratified by stage and GEP test. We estimated stage-specific hazard ratios for melanoma recurrence if they were not directly reported by a study but could be generated from published data.22

Prognostic Factor Level of Evidence

The quality of evidence was assessed independently as high, moderate, low, or very low (M.A.M. and E.K.B.) using an adaptation of Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) proposed for systematic reviews of prognostic factor research (eMethods in the Supplement).17,23,24

Statistical Analysis

Individual studies were assessed for the relative proportion of patients with or without melanoma recurrence correctly classified by the GEP test as high or low risk. The proportion of patients with melanoma recurrence correctly classified by the GEP test as high risk was defined by dividing true-positive results by the sum of true-positive and false-negative results. The proportion of patients without melanoma recurrence correctly classified by the GEP test as low risk was defined by dividing true-negative results by the sum of true-negative and false-positive results. For the DecisionDx-Melanoma test, class 2 results were considered high risk and class 1 results were considered low risk. Estimates were stratified by AJCC stage within each study. Estimates of relative proportion, if not explicitly stated within the manuscript, were made if enough information was available to infer the proportion. Meta-analysis was performed using Stata, version 16.0 (StataCorp) for the DecisionDx-Melanoma test. Because only 1 study using MelaGenix contributed data for each stage of disease, meta-analysis was not feasible. Random-effects models were used to estimate summary effect sizes along with 95% CIs. Separate analyses were performed by disease stage. The degree of heterogeneity among studies was visually assessed by forest plots and by calculating the I2 statistic. Potential reporting bias was assessed by the Egger test for small study effects along with Egger plots of the standardized effect estimates by the precision of the estimate. The Fisher exact test was used for comparisons of categorical data. A 2-tailed P < .05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Study Search and Study Characteristics

The systematic search identified 1318 studies, from which 6 articles25,26,27,28,29,30 and 1 abstract31 were included (Table 1 and eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Five articles25,26,27,28,29 reported recurrence outcomes for 1117 patients (age and sex unknown) with localized melanoma tested with DecisionDx-Melanoma. One article30 and 1 abstract31 reported recurrence outcomes for 333 patients (age and sex unknown) tested with MelaGenix. All studies were observational: 3 prospective,25,26,28 3 retrospective,27,30,31 and 1 both prospective and retrospective.29 Four studies28,29,30,31 enrolled patients with localized melanoma only. In 4 studies,25,26,28,29 assessment of patient outcomes was not blinded to GEP test results. Only 2 studies26,30 had rule-based follow-up and/or imaging surveillance of patients based on stage of disease. Two DecisionDx-Melanoma studies25,26 had partially overlapping cohorts.

Table 1. Characteristics of Included Studies.

| Study | Index prognostic factor | Design, setting, and population | Sampling technique (dates of melanoma diagnosis) | Participants by AJCC stage, No. (%) | Male, No. (%) | Age, median, y (follow-up duration, median, y) | Breslow thickness, median, mm | Ulceration, No. (%) | Anatomical sites, No. (%) | Follow-up and imaging protocol | Outcomes blinded to GEP result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hsueh et al,25 2017 (US) | DecisionDx-Melanoma (Castle Biosciences Inc [which also provided funding]) | Observational, prospective registry, multicenter (n = 11); hospital and community based; patients with resected melanoma with a successful GEP resulta | Nonprobability, convenience (NR) | 209 (66) Stage I; 73 (23) stage II; 36 (11) stage III | 176 (55) | 58 (1.5 Without event and 1 with event) | 1.2 | Present: 58 (18); unknown: 26 (8) | Head/neck: 58 (18); trunk: 86 (27); extremity: 178 (55) | Nob | Nob |

| Greenhaw et al,29 2018 (US) | DecisionDx-Melanoma (Castle Biosciences Inc; funded by Zitelli and Brodland, PCc) | Observational, mixed retrospective and prospective cohorts; single center, community based; patients with resected melanoma with previous GEP testing performed as part of clinical care and patients with melanoma with known metastatic disease who subsequently underwent GEP testing | Nonprobability, convenience (NR) | 219 (86) Stage I; 37 (14) stage II | 160 (63) | 68 For class 1 and 72 for class 2 (1.9 [mean]) | 0.4 (Class 1); 2 (class 2) | Present: 26 (10); unknown: 2 (1) | NR | Retrospective cohort: non–rule based; prospective cohort: rule based by GEP test scorec | Noc |

| Zager et al,27 2018 (US) | DecisionDx-Melanoma (Castle Biosciences Inc [which also provided funding]) | Observational, retrospective cohort of archival specimens; multicenter (n = 16), hospital and community based; patients with resected stage I-III melanoma with minimum of 5 y of follow-up if no recurrence | Nonprobability, convenience (2000-2014) | 264 (50) Stage I; 93 (18) stage II; 166 (32) stage III | NR | 59 (7.5 Without event; 1.2 with event) | 1.2; Unknown in 4 (1%) | Present: 133 (26); unknown: 81 (15) | NR | No | Yes |

| Keller et al,26 2019 (US) | DecisionDx-Melanoma (Castle Biosciences Inc, funded by St. Louis University Cancer Center) | Observational, prospective cohort; single center, hospital based; patients with melanoma undergoing WLE and SLN biopsya | Nonprobability, convenience (2013-2015) | 96 (60) Stage I; 40 (25) stage II; 23 (15) stage III | 98 (62) | 59 (3.5) | 1.4 | Present: 38 (24) | Head/neck: 26 (16); trunk: 68 (43); extremity: 65 (41) | Rule based by stage of disease | No |

| Podlipnik et al,28 2019 (Spain) | DecisionDx-Melanoma (Castle Biosciences Inc [which also provided funding]) | Observational, prospective cohort; multicenter (n = 5), hospital based; patients with resected stage IB-II melanoma (85% underwent SLN biopsy)d | Nonprobability, convenience (2015-2016)d | 62 (72) Stage IB or IIA; 24 (28) stage IIB or C | 40 (47) | 59 (2.2) | 2.5 (Mean) | Present: 26 (30) | Head/neck: 11 (13); trunk: 37 (43); legs: 21 (24); arms: 12 (14); acral: 5 (6) | Nod | Nod |

| Koelblinger et al,31 2018 (Germany) | MelaGenix (NeraCare GmbH [funding not reported]) | Observational, case-control (retrospective); hospital based; patients with melanoma ≤1 mm with recurrence (cases) or disease free (controls) | NR (NR) | 88 (100) Stage I | NR | NR (3.7) | 0.8 (Cases); 0.6 (controls) | NR | NR | NR | Yes |

| Amaral et al,30 2020 (Germany) | MelaGenix (NeraCare GmbH [which also provided funding along with Eberhard-Karls University of Tuebingen])e | Observational, retrospective analysis of archival registry; single center, hospital based; patients with resected stage II melanoma with available tissue (80% underwent SLN biopsy) | Nonprobability, consecutive (2000-2016)e | 245 (100) Stage II | 134 (55) | 70 (3.4) | 3.0 | Present: 142 (58) | NR | Rule based by stage of diseasee | Yese |

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; GEP, gene expression profile; NR, not reported; SLN, sentinel lymph node; WLE, wide local excision.

There were partially overlapping patient populations (ie, a proportion of patients described by Keller et al26 are included in the study by Hsueh et al25).

Date of email communication with study author was December 11, 2019.

Date of email communication with study author was January 21, 2020.

Dates of email communication with study author were December 13, 2019; and January 22, 2020; and February 4, 2020.

Date of email communication with study author was January 22, 2020.

Individual Study Risk of Bias

No study had an overall low risk of bias, 1 study30 had a moderate risk of bias, and 6 studies25,26,27,28,29,31 had a high risk of bias (eFigure 2 and eTable 2 in the Supplement). The number of individual domains rated as high risk ranged from 0 to 4 (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

Primary Outcome (Melanoma Recurrence)

There was inconsistency across studies in the definition of melanoma recurrence. Hsueh et al25 defined recurrence as a regional or distant metastasis. Greenhaw et al29 defined recurrence as a satellite, in-transit, nodal, or distant metastasis. Zager et al27 defined recurrence as any local, regional, or distant metastasis. Podlipnik et al,28 Keller et al,26 and Koelblinger et al31 did not provide a clear definition of disease recurrence. Amaral et al30 defined recurrence as all melanoma-specific disease progressions. All these definitions were considered to represent melanoma recurrence in analyses.

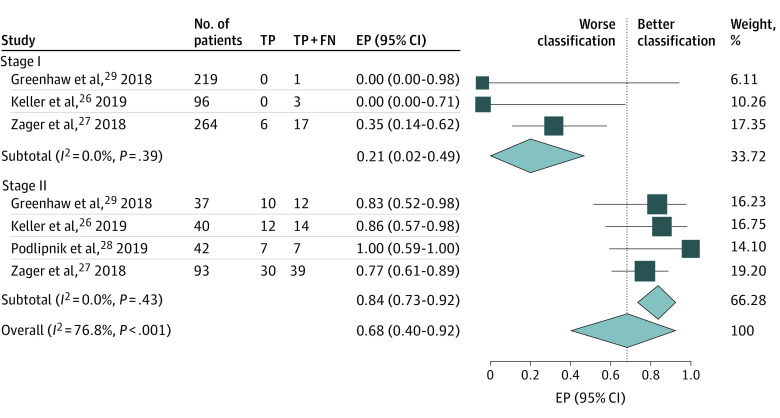

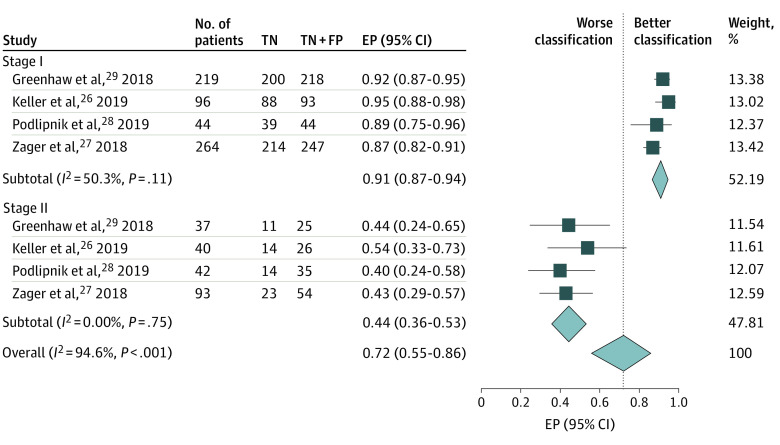

DecisionDx-Melanoma

Four studies26,27,28,29 contributed 623 patients with stage I disease; 6 had true-positive results, 15 had false-negative results, 61 had false-positive results, and 541 had true-negative results (Table 2 and Table 3). Of the 21 patients (3%) who developed recurrence, 6 (29%) had a high-risk GEP test score; the estimated proportion from meta-analysis was 21% (95% CI, 2%-49%) (Figure 1). Of 602 patients (97%) who did not develop recurrence, 541 (90%) had a low-risk score; the estimated proportion from meta-analysis was 91% (95% CI, 87%-94%) (Figure 2). No significant heterogeneity was identified.

Table 2. Performance of Index GEP Tests in Predicting Melanoma Recurrence by Study and Stage of Disease.

| Source | No. | Observed RFS rates, % (follow-up, y) | Association between GEP high score and event | Proportion, % | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Observed eventsa | GEP low score | GEP high score | HR (95% CI) | P value | Events classified as high risk (follow-up, y)b | Nonevents classified as low risk (follow-up, y)b | High-risk patients with event | Low-risk patients without event | |

| Stage I melanoma | ||||||||||

| DecisionDx | ||||||||||

| Hsueh et al,25 2017 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Greenhaw et al,29 2018 | 219 | 1 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0 | 92 | 0 | >99 |

| Zager et al,27 2018 | 264 | 17 | 96 (5) | 85 (5) | 4.01 (1.5-11.5)c | .007 | 35; 40 (5) | 87; 87 (5) | 15 | 95 |

| Keller et al,26 2019 | 96 | 3 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0 | 95 | 0 | 97 |

| Podlipnik et al,28 2019 | 44 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NA | 89 | 0 | 100 |

| MelaGenixd | ||||||||||

| Koelblinger et al,31 2018 | 88 | 22 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 32 | 77 | 32 | 77 |

| Amaral et al,30 2020 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Stage II melanoma | ||||||||||

| DecisionDx | ||||||||||

| Hsueh et al,25 2017 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Greenhaw et al,29 2018 | 37 | 12 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 83 | 44 | 42 | 85 |

| Zager et al,27 2018 | 93 | 39 | 74 (5) | 55 (5) | 2.5 (1.1-5.5)c | .02 | 77; 76 (5) | 43; 40 (5) | 49 | 72 |

| Keller et al,26 2019 | 40 | 14 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 86 | 54 | 50 | 88 |

| Podlipnik et al,28 2019 | 42 | 7 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 100 | 40 | 25 | 100 |

| MelaGenixd | ||||||||||

| Koelblinger et al,31 2018 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Amaral et al,30 2020 | 245 | 78 | 76 (5); 73 (10) | 58 (5); 46 (10) | NR | NR | 76 | 43 | 38 | 79 |

| Stage I-II melanoma | ||||||||||

| DecisionDx | ||||||||||

| Hsueh et al,25 2017 | 282 | 14 | 99 (1.5) | 85 (1.5) | NR | NR | 79 | 82 | 19 | 99 |

| Greenhaw et al,29 2018 | 256 | 13 | 98 (3); 93 (5) | 74 (3); 69 (5) | OR, 22.0 (5.7-84.2)e | .01 | 77; 78 (3); 73 (5) | 87; 79 (3); 70 (5) | 24 | 99 |

| Zager et al,27 2018 | 357 | 56 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 64 | 79 | 36 | 92 |

| Keller et al,26 2019 | 136 | 17 | NR | NR | NR | 71 | 86 | 41 | 95 | |

| Podlipnik et al,28 2019 | 86 | 7 | NR | NR | 18.8 (1.8-2549.8)f | .01 | 100 | 67 | 21 | 100 |

| MelaGenixd | ||||||||||

| Koelblinger et al,31 2018 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Amaral et al,30 2020 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: GEP, gene expression profile; HR, hazard ratio; NA, not applicable; NR, not reported; OR, odds ratio; RFS, recurrence-free survival.

Melanoma recurrence and melanoma relapse were considered synonymous. Hsueh et al25 defined recurrence as regional or distant metastasis. Greenhaw et al29 defined recurrence as satellite, in-transit, nodal, or distant metastasis. Zager et al27 defined recurrence as any local, regional, or distant metastasis. Podlipnik et al,28 Keller et al,26 and Koelblinger et al31 did not provide a clear definition of disease recurrence. Amaral et al30 defined recurrence as all melanoma-specific disease progressions.

Unless indicated by a particular cross-sectional follow-up time (ie, 3- or 5-year), reported proportions were calculated using the raw number of high-score GEP patients with an event, number of high-score GEP patients without an event, number of low-score GEP patients with an event, and number of low-score GEP patients without an event. If indicated by a cross-sectional follow-up time, these estimates represent the sensitivity and specificity of the test and were estimated from Kaplan-Meier curves and/or data (see Methods).

Not reported in study but estimated by reviewers by extracting data from published Kaplan-Meier curves; therefore, it is not adjusted for any confounding variables.

Univariate OR was not reported in the study at a particular cross-sectional follow-up time or by stage of disease. The reviewers calculated the univariate OR to be 3.6 (95% CI, 0.1-91.9; P = .44) for patients with stage I disease and 3.9 (95% CI, 0.7-21.7; P = .12) for patients with stage II disease.

Multivariate HR adjusted for American Joint Committee on Cancer stage (IIB-IIC) and age (>50 years).

Table 3. Observed Frequencies of DecisionDx-Melanoma Test Results in Patients With Localized Cutaneous Melanoma Stratified by American Joint Committee on Cancer Stage.

| Group | Patients, No. (%)a | |

|---|---|---|

| Recurrence | No recurrence | |

| Stage I melanoma (n = 623)26,27,28,29 | ||

| Class 1 | 15 (2) | 541 (87) |

| Class 2 | 6 (1) | 61 (10) |

| Stage II melanoma (n = 212)26,27,28,29 | ||

| Class 1 | 13 (6) | 62 (29) |

| Class 2 | 59 (28) | 78 (37) |

| Stage I-II melanoma (n = 1117)25,26,27,28,29 | ||

| Class 1 | 31 (3) | 824 (74) |

| Class 2 | 76 (7) | 186 (17) |

| Stage I-II melanoma with known stage of disease and melanoma recurrence outcome data (n = 835)26,27,28,29,b | ||

| Stage I | 21 (3) | 602 (72) |

| Stage II | 72 (9) | 140 (17) |

Percentages may not sum to 100 owing to rounding.

Data unavailable by stage for the patients in the study by Hsueh et al.25

Figure 1. Estimated Proportion (EP) of Patients With a Melanoma Recurrence Correctly Classified as High Risk by DecisionDx-Melanoma, Stratified by American Joint Committee on Cancer Stage.

The study by Podlipnik et al28 was excluded from stage I analysis because there were no melanoma recurrences. FN indicates false-negative results; TP, true-positive results.

Figure 2. Estimated Proportion (EP) of Patients Without a Melanoma Recurrence Correctly Classified as Low Risk by DecisionDx-Melanoma, Stratified by American Joint Committee on Cancer Stage.

FP indicates false-positive results; TN, true-negative results.

Four studies26,27,28,29 contributed 212 patients with stage II disease; 59 patients had true-positive results, 13 had false-negative results, 78 had false-positive results, and 62 had true-negative results (Table 2 and Table 3). Of the 72 patients (34%) who developed recurrence, 59 (82%) had a high-risk GEP test score; the estimated proportion from meta-analysis was 84% (95% CI, 73%-92%) (Figure 1). Of 140 patients (66%) who did not develop recurrence, 62 (44%) had a low-risk score; the estimated proportion from meta-analysis was 44% (95% CI, 36%-53%) (Figure 2). No significant heterogeneity was identified.

When the performance in patients with stage I vs stage II disease was compared, meta-analysis revealed significant interstage heterogeneity for the estimated proportions of patients with or without melanoma recurrence correctly classified by DecisionDx-Melanoma as measured by the I2 statistic (76.8% for patients with melanoma recurrence and 94.6% for patients without melanoma recurrence, P < .001 for both) (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Five studies25,26,27,28,29 contributed 1117 partially overlapping patients with stage I or stage II disease; 76 patients had true-positive results, 31 had false-negative results, 186 had false-positive results, and 824 had true-negative results (Table 3). Of the 107 patients (10%) who developed recurrence, 76 (71%) had a high-risk GEP test score; the estimated proportion from meta-analysis was 75% (95% CI, 63%-86%). Of 1010 patients (90%) who did not develop recurrence, 824 (82%) had a low-risk score; the estimated proportion from meta-analysis was 81% (95% CI, 76%-86%) (eFigures 3 and 4 in the Supplement).

We found reporting bias for the proportion of patients with stage I or stage II disease combined who had melanoma recurrence correctly identified as high risk (eFigure 5 in the Supplement). No other reporting bias was identified (eFigures 6-10 in the Supplement).

MelaGenix

One study31 reported 88 patients with stage I disease; 7 patients had true-positive results, 15 had false-negative results, 15 had false-positive results, and 51 had true-negative results. Of the 22 patients (25%) who developed recurrence, 7 (32%) had a high-risk GEP score. Of the 66 patients (75%) without recurrence, 51 (77%) had a low-risk GEP score (Table 2).

One study30 reported 245 patients with stage II disease; 59 patients had true-positive results, 19 had false-negative results, 95 had false-positive results, and 72 had true-negative results. Of the 78 patients (32%) who developed recurrence, 59 (76%) had a high-risk GEP test score. Of the 167 patients (68%) who did not develop recurrence, 72 (43%) had a low-risk GEP score (Table 2).

Secondary Outcomes and Level of Evidence

Secondary outcome data are shown in Table 2 and the eResults and eTables 3-5 in the Supplement. The overall quality of evidence for the outcome of melanoma recurrence was rated as very low for stage I disease and low for stage II disease for both tests (eTables 6-9 in the Supplement).

Discussion

We identified and analyzed all external validation studies to date reporting on the performance of 2 commercially available prognostic GEP tests for patients with localized melanoma. The analysis found that the performance of the GEP tests differed significantly by AJCC stage. In our assessment, reported studies had moderate to high risk of bias because of poor design standards, conduct, reporting, and analysis. These methodologic shortcomings are common to studies of prognostic factors and highlight the critical need for improvement.13,19

The prognostic ability of GEP tests and study quality of data were limited in patients with stage I disease, who are more commonly seen and followed up by dermatologists. Most patients with stage I disease with melanoma events were incorrectly classified as being at low risk for recurrence by GEP tests, suggesting that these tests are unlikely to alter management and/or reduce mortality at the population level. Unknown are the harms associated with a false-positive result, which were 10-fold more frequent than true-positive results in patients with stage I disease. The harms are determined by the intervention intended to be guided by the test result and must be weighed against the benefit of the reassurance provided by a true-negative result. Given the low absolute number of reported events, however, further research may better quantify test performance. Of note, no study reported prognostic effect estimates specifically for patients with stage I disease adjusted for known clinicopathologic confounding variables. This effort was further hampered by the relatively short follow-up of cohorts of patients with stage I disease, a patient population in whom recurrences are not only infrequent but also more often late, well beyond the reported median follow-up in these studies.32,33 In contrast, most patients with stage II melanoma events were correctly classified as being at high risk for recurrence by GEP tests; however, a significant proportion of patients without an event were incorrectly identified as being at high risk for recurrence compared with those with stage I disease. These data suggest the potential for greater clinical utility among patients with stage II disease, and additional research should be prioritized for this population.

The reasons for a difference in prognostic performance by disease stage are likely multifactorial. By intent, test development is performed in a cohort of patients enriched for events, which may lead to enhanced performance in a particular cohort. The GEP test results have also been associated with multiple well-established prognostic factors, such as age,25,26,29 sex,25,26 tumor thickness,25,27,28,29 mitotic rate,29 ulceration,28,29 AJCC stage,25,26,28 T stage,26 and nodal status,25,26 factors known to vary significantly with or be associated with disease stage. Heterogeneity in GEPs within or between tumors by stage may further contribute to stage-specific test performance. Given the variability in test performance by risk of event, when unadjusted for other factors, test performance was dependent on the study cohort. Studies combining patients with stage I or stage II disease have appeared to demonstrate favorable test characteristics because most events occurred in patients with stage II melanoma, for whom a high-risk GEP score was common, and most nonevents occurred in patients with stage I disease, for whom a low-risk GEP score is common. However, dichotomizing patients with stage I or stage II disease by stage alone was associated with similar performance to the DecisionDx-Melanoma test (Table 3); this analysis should be cautiously interpreted because it was dependent on the relative proportions of patients with stage I vs stage II disease in the cohort and may not be representative of the population with melanoma overall. However, the analysis found that although the DecisionDx-Melanoma test has significant prognostic value, further research is needed to define the incremental improvement in risk predictions provided by the test beyond those from readily available clinicopathologic data or multivariable risk prediction models. Therefore, as suggested by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, version 2.2020 melanoma guidelines section on the principles of molecular testing,12 it is important to assess GEP test performance in the context of all other known clinicopathologic factors (eg, patient sex, age, tumor location and thickness, ulceration, mitotic rate, lymphovascular invasion, microsatellites, and sentinel lymph node biopsy status). The aim of such an analysis would be to identify patients for whom the GEP test adds clinically significant prognostic information leading to a change in treatment. Furthermore, it must be demonstrated that such a change in treatment leads to an improvement in patient outcomes.

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, given the heterogeneity in study designs and data reporting, as well as the lack of availability of individual patient data, meta-analysis of hazard ratios was not feasible. The lack of individual patient data limited our combined stage I-II analysis because 2 studies25,26 had partially overlapping cohorts. This overlap, however, did not affect stage-specific analyses. Second, the primary outcome is problematic for time-to-event analyses, particularly if studies have short follow-up and significant censoring; indeed, the proportion of total melanoma recurrences in a mixed stage I to III cohort correctly classified as high risk by DecisionDx-Melanoma decreased from 80% at a median event-free follow-up of 1.5 years25 to 60% at a median event-free follow-up of 3.2 years (P = .11).34 Therefore, proportions reported herein should be viewed as surrogate measures of test performance and should not be interpreted as definitive measures, such as sensitivity and specificity. The variability in the definitions used for melanoma recurrence limit the validity of our primary and secondary outcomes. We did not analyze GEP performance using other cut points (ie, classes 1A, 1B, 2A, and 2B for DecisionDx-Melanoma). Third, risk of bias and level of evidence assessments are subjective, even when using structured tools. The interrater agreement (κ statistic) for QUIPS has been reported to range from 0.48 to 0.82.16,35 For transparency, we provided our key considerations by domain in the risk of bias assessment in eTable 2 in the Supplement but acknowledge that other raters may have weighted these considerations differently; we cannot exclude the possibility of bias or reverse bias.36

Conclusions

This study found that the prognostic ability of DecisionDx-Melanoma and MelaGenix to predict recurrence among patients with localized melanoma varied by AJCC stage and appeared to be poor for patients with stage I disease. Additional, more rigorously structured research appears to be needed to better quantify the association of GEP tests with melanoma outcomes and to demonstrate clinical utility.

eAppendix. Trial Protocol

eMethods. Supplementary Methods

eTable 1. Database Search Strategies

eTable 2. Key Considerations in Study Risk of Bias Assessment (QUIPS tool)

eTable 3. Performance of Index Gene Expression Profile Tests in Predicting Melanoma Distant Metastasis by Study and Stage of Disease

eTable 4. Performance of Index Gene Expression Profile Tests in Predicting Death From Melanoma by Study and Stage of Disease

eTable 5. Performance of Index Gene Expression Profile Tests in Predicting Death From Any Cause by Study and Stage of Disease

eTable 6. Adapted Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Table for Systematic Reviews of Prognostic Studies (Outcome: Melanoma Recurrence)

eTable7. Adapted Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Table for Systematic Reviews of Prognostic Studies (Outcome: Melanoma Distant Metastasis)

eTable 8. Adapted Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Table for Systematic Reviews of Prognostic Studies (Outcome: Death From Melanoma)

eTable 9. Adapted Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Table for Systematic Reviews of Prognostic Studies (Outcome: Death From Any Cause)

eFigure 1. Diagram of the Study Selection for the Systematic Review

eFigure 2. Risk of Bias Assessment Using the QUIPS Tool

eFigure 3. Forest Plot of the Proportion of Stage I-II Patients With a Melanoma Recurrence Correctly Classified as High Risk by DecisionDx-Melanoma

eFigure 4. Forest Plot of the Proportion of Stage I-II Patients Without a Melanoma Recurrence Correctly Classified as Low Risk by DecisionDx-Melanoma

eFigure 5. Egger’s Publication Bias Plot of the Standardized Effect Estimate for Stage I-II Disease by the Precision of the Estimate

eFigure 6. Egger’s Publication Bias Plot of the Standardized Effect Estimate for Stage I Disease by the Precision of the Estimate

eFigure 7. Egger’s Publication Bias Plot of the Standardized Effect Estimate for Stage II Disease by the Precision of the Estimate

eFigure 8. Egger’s Publication Bias Plot of the Standardized Effect Estimate for Stage I Disease by the Precision of the Estimate

eFigure 9. Egger’s Publication Bias Plot of the Standardized Effect Estimate for Stage II Disease by the Precision of the Estimate

eFigure 10. Egger’s Publication Bias Plot of the Standardized Effect Estimate for Stage I-II Disease by the Precision of the Estimate

eResults. Supplementary Results

eReferences

References

- 1.Castle Biosciences DecisionDx-Melanoma overview. 2019. Accessed March 18, 2020. https://castlebiosciences.com/products/decisiondx-melanoma/

- 2.NeraCare GmbH. MelaGenix 2019. Accessed June 19, 2020. https://www.melagenix.info/for-patients

- 3.Amin MB, Edge S, Greene F, et al. , eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed Springer; 2017. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-40618-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gastman BR, Gerami P, Kurley SJ, Cook RW, Leachman S, Vetto JT. Identification of patients at risk of metastasis using a prognostic 31-gene expression profile in subpopulations of melanoma patients with favorable outcomes by standard criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(1):149-157.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.07.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gastman BR, Zager JS, Messina JL, et al. Performance of a 31-gene expression profile test in cutaneous melanomas of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2019;41(4):871-879. doi: 10.1002/hed.25473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerami P, Cook RW, Russell MC, et al. Gene expression profiling for molecular staging of cutaneous melanoma in patients undergoing sentinel lymph node biopsy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(5):780-785.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerami P, Cook RW, Wilkinson J, et al. Development of a prognostic genetic signature to predict the metastatic risk associated with cutaneous melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(1):175-183. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brunner G, Heinecke A, Falk TM, et al. A prognostic gene signature expressed in primary cutaneous melanoma: synergism with conventional staging. J Natl Cancer Inst Cancer Spectr. 2018;2(3):pky032. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pky032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vetto JT, Hsueh EC, Gastman BR, et al. Guidance of sentinel lymph node biopsy decisions in patients with T1-T2 melanoma using gene expression profiling. Future Oncol. 2019;15(11):1207-1217. doi: 10.2217/fon-2018-0912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marchetti MA, Bartlett EK, Dusza SW, Bichakjian CK. Use of a prognostic gene expression profile test for T1 cutaneous melanoma: will it help or harm patients? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(6):e161-e162. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maetzold D. Castle Biosciences announces Medicare Coverage for the DecisionDx-Melanoma test in cutaneous melanoma. News release. Castle Biosciences Inc; October 18, 2018. Accessed May 18, 2020. https://skinmelanoma.com/castle-biosciences-announces-medicare-coverage-decisiondx-melanoma-test-cutaneous-melanoma/

- 12.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology—cutaneous melanoma. 2020. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cutaneous_melanoma.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Riley RD, Moons KGM, Snell KIE, et al. A guide to systematic review and meta-analysis of prognostic factor studies. BMJ. 2019;364:k4597. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k4597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151(4):264-269, w264. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Marchetti M, Bartlett E, Dusza S, Mclean L, Yu A, Matsoukas K Performance of gene expression profile-based tests for predicting clinical outcomes in localized cutaneous melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis: PROSPERO: CRD42019146778. Accessed November 20, 2019. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42019146778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Hayden JA, van der Windt DA, Cartwright JL, Côté P, Bombardier C. Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(4):280-286. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cochrane Prognosis Methods Group Tools. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2020. Accessed May 18, 2020. https://methods.cochrane.org/prognosis/tools

- 18.Cochrane Reviews Assessing risk of bias in included studies. 2020. Accessed April 17, 2020. https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/chapter_8/table_8_7_a_possible_approach_for_summary_assessments_of_the.htm

- 19.Altman DG, McShane LM, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE. Reporting Recommendations for Tumor Marker Prognostic Studies (REMARK): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2012;9(5):e1001216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rector TS, Taylor BC, Wilt TJ. Chapter 12: systematic review of prognostic tests. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(suppl 1):S94-S101. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1899-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai T, Pepe MS, Zheng Y, Lumley T, Jenny NS. The sensitivity and specificity of markers for event times. Biostatistics. 2006;7(2):182-197. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxi047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 2007;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huguet A, Hayden JA, Stinson J, et al. Judging the quality of evidence in reviews of prognostic factor research: adapting the GRADE framework. Syst Rev. 2013;2:71. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-2-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayden JA, Côté P, Steenstra IA, Bombardier C; QUIPS-LBP Working Group . Identifying phases of investigation helps planning, appraising, and applying the results of explanatory prognosis studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(6):552-560. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsueh EC, DeBloom JR, Lee J, et al. Interim analysis of survival in a prospective, multi-center registry cohort of cutaneous melanoma tested with a prognostic 31-gene expression profile test. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10(1):152. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0520-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keller J, Schwartz TL, Lizalek JM, et al. Prospective validation of the prognostic 31-gene expression profiling test in primary cutaneous melanoma. Cancer Med. 2019;8(5):2205-2212. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zager JS, Gastman BR, Leachman S, et al. Performance of a prognostic 31-gene expression profile in an independent cohort of 523 cutaneous melanoma patients. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):130. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4016-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Podlipnik S, Carrera C, Boada A, et al. Early outcome of a 31-gene expression profile test in 86 AJCC stage IB-II melanoma patients: a prospective multicentre cohort study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(5):857-862. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greenhaw BN, Zitelli JA, Brodland DG. Estimation of prognosis in invasive cutaneous melanoma: an independent study of the accuracy of a gene expression profile test. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44(12):1494-1500. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amaral TMS, Hoffmann MC, Sinnberg T, et al. Clinical validation of a prognostic 11-gene expression profiling score in prospectively collected FFPE tissue of patients with AJCC v8 stage II cutaneous melanoma. Eur J Cancer. 2020;125:38-45. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.10.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koelblinger P, Levesque MP, Kaufmann C, et al. A prognostic gene-signature based identification of high-risk thin melanomas. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(15)(suppl):e21575-e21575. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.e21575 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faries MB, Steen S, Ye X, Sim M, Morton DL. Late recurrence in melanoma: clinical implications of lost dormancy. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217(1):27-34. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Green AC, Baade P, Coory M, Aitken JF, Smithers M. Population-based 20-year survival among people diagnosed with thin melanomas in Queensland, Australia. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(13):1462-1467. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsueh EC, DeBloom JR, Cook RW, McMasters K. Three-year survival outcomes in a prospective cohort evaluating a prognostic 31-gene expression profile (31-GEP) test for cutaneous melanoma (CM). J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15)(suppl):9519. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.9519 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grooten WJA, Tseli E, Äng BO, et al. Elaborating on the assessment of the risk of bias in prognostic studies in pain rehabilitation using QUIPS-aspects of interrater agreement. Diagn Progn Res. 2019;3:5. doi: 10.1186/s41512-019-0050-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ioannidis JP. Why most discovered true associations are inflated. Epidemiology. 2008;19(5):640-648. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31818131e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Trial Protocol

eMethods. Supplementary Methods

eTable 1. Database Search Strategies

eTable 2. Key Considerations in Study Risk of Bias Assessment (QUIPS tool)

eTable 3. Performance of Index Gene Expression Profile Tests in Predicting Melanoma Distant Metastasis by Study and Stage of Disease

eTable 4. Performance of Index Gene Expression Profile Tests in Predicting Death From Melanoma by Study and Stage of Disease

eTable 5. Performance of Index Gene Expression Profile Tests in Predicting Death From Any Cause by Study and Stage of Disease

eTable 6. Adapted Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Table for Systematic Reviews of Prognostic Studies (Outcome: Melanoma Recurrence)

eTable7. Adapted Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Table for Systematic Reviews of Prognostic Studies (Outcome: Melanoma Distant Metastasis)

eTable 8. Adapted Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Table for Systematic Reviews of Prognostic Studies (Outcome: Death From Melanoma)

eTable 9. Adapted Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Table for Systematic Reviews of Prognostic Studies (Outcome: Death From Any Cause)

eFigure 1. Diagram of the Study Selection for the Systematic Review

eFigure 2. Risk of Bias Assessment Using the QUIPS Tool

eFigure 3. Forest Plot of the Proportion of Stage I-II Patients With a Melanoma Recurrence Correctly Classified as High Risk by DecisionDx-Melanoma

eFigure 4. Forest Plot of the Proportion of Stage I-II Patients Without a Melanoma Recurrence Correctly Classified as Low Risk by DecisionDx-Melanoma

eFigure 5. Egger’s Publication Bias Plot of the Standardized Effect Estimate for Stage I-II Disease by the Precision of the Estimate

eFigure 6. Egger’s Publication Bias Plot of the Standardized Effect Estimate for Stage I Disease by the Precision of the Estimate

eFigure 7. Egger’s Publication Bias Plot of the Standardized Effect Estimate for Stage II Disease by the Precision of the Estimate

eFigure 8. Egger’s Publication Bias Plot of the Standardized Effect Estimate for Stage I Disease by the Precision of the Estimate

eFigure 9. Egger’s Publication Bias Plot of the Standardized Effect Estimate for Stage II Disease by the Precision of the Estimate

eFigure 10. Egger’s Publication Bias Plot of the Standardized Effect Estimate for Stage I-II Disease by the Precision of the Estimate

eResults. Supplementary Results

eReferences