Abstract

Despite significant interest in developing extracellular matrix (ECM)-inspired biomaterials to recreate native cell-instructive microenvironments, the major challenge in the biomaterial field is to recapitulate the complex structural and biophysical features of native ECM. These biophysical features include multiscale hierarchy, electrical conductivity, optimum wettability, and mechanical properties. These features are critical to the design of cell-instructive biomaterials for bioengineering applications such as skeletal muscle tissue engineering. In this study, we used a custom-designed film fabrication assembly, which consists of a microfluidic chamber to allow electrostatic charge-based self-assembly of oppositely charged polymer solutions forming a hydrogel fiber and eventually, a nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel film. The film recapitulates unidirectional hierarchical fibrous structure along with the conductive properties to guide initial alignment and myotube formation from cultured myoblasts. We combined high conductivity, and charge carrier mobility of graphene with biocompatibility of polysaccharides to develop graphene–polysaccharide nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films. The incorporation of graphene in fibrous hydrogel films enhanced their wettability, electrical conductivity, tensile strength, and toughness without significantly altering their elastic properties (Young’s modulus). In a proof-of-concept study, the mouse myoblast cells (C2C12) seeded on these nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films showed improved spreading and enhanced myogenesis as evident by the formation of multinucleated myotubes, an early indicator of myogenesis. Overall, graphene–polysaccharide nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films provide a potential biomaterial to promote skeletal muscle tissue regeneration.

Keywords: bioinspired, C2C12, graphene nanocomposite, hydrogel, self-assembly, skeletal muscle

1 |. INTRODUCTION

In response to skeletal muscle injury, resident multipotent satellite cells proliferate and differentiate eventually into multinucleated myotubes, which then fuse with the existing damaged myofibrils or form new myofibrils to restore the function (Schultz, Jaryszak, & Valliere, 1985). However, larger volumetric muscle loss is beyond the regeneration potential of these cells; therefore, several therapeutic strategies have been developed. Delivery of satellite cells at the site of injury could not fully achieve the regenerative outcome since the cells require suitable microenvironment to proliferate, orient, and differentiate (Fuoco, Petrilli, Cannata, & Gargioli, 2016; Rozario & DeSimone, 2010). To support these functions of local host or donor cells, several biomaterial-based grafts are being developed for skeletal muscle tissue engineering (Kwee & Mooney, 2017).

Extracellular matrix (ECM) of the skeletal muscle plays an active role in the repair of skeletal muscle injuries. It is mainly composed of macromolecules arranged in a complex form to guide and support the cells in the local microenvironment by promoting cell–matrix interactions. Hence, ECM-mimetic biomaterials are gaining importance as a central theme for tissue engineering-based approaches (S. Sant, Hancock, Donnelly, Iyer, & Khademhosseini, 2010). Indeed, several studies have identified key biophysical features to be considered for the design of cell-instructive biomaterials for skeletal muscle regeneration. Some of these critical features include multiscale hierarchical structures (Guven et al., 2015; Yeong et al., 2010), favorable wettability profile for adhesion and cell–matrix interactions (Tamada & Ikada, 1993), alignment cues for contact guidance (Bae et al., 2014; Kerativitayanan, Carrow, & Gaharwar, 2015), electrical conductivity to facilitate communication between myoblasts (Ahadian, Ostrovidon et al., 2013; Ahadian, Ramón-Azcón, Chang et al., 2014) and mechanical properties (Corona et al., 2012; Feng et al., 2010). While biophysical stimuli such as wettability and nanoroughness may be sensed by cells almost immediately after coming in contact with the material, the other stimuli such as electrical conductivity and alignment are sensed following the adhesion and spreading of myoblasts on the materials (Ahadian, Ostrovidon et al., 2013). The electrical conductivity of the material promotes myoblast differentiation into myotubes (Ahadian, Ramalingam et al., 2013; Ahadian, Ramón-Azcón, Chang et al., 2014). Thus, ideal skeletal muscle graft materials must go beyond the basic goals of providing a substrate for cell adhesion and focus on recreating the complex biophysical microenvironments.

In the last few years, carbon-based materials such as carbon nanotubes and various forms of graphene have been explored for engineering regenerative skeletal muscle ECM (Ahadian, Ramón-Azcón, Chang et al., 2014; Chaudhuri, Bhadra, Moroni, & Pramanik, 2015; Montesano et al., 2013). Among all carbon-based materials, graphene possesses unique properties such as strong mechanical properties, easy processability to create complex architectures, high conductivity, and charge carrier mobility, mostly due to its two-dimensional (2D) structure (Goenka, Sant, & Sant, 2014; Novoselov et al., 2004; V. Sant, Goenka, & Sant, 2015). Most importantly, incorporation of graphene increases conductivity of biomaterials, which has been used to the advantage of tissue engineering of neural and cardiac tissues with or without external electrical stimulus (Chaudhuri et al., 2015; Heidari, Bahrami, & Ranjbar-Mohammadi, 2017; Lin, Marchant, Zhu, & Kottke-Marchant, 2014; Qiu et al., 2014; Wan et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2017). It is widely acknowledged that these conductive materials hold great promise for restoring the cell-interactive microenvironment for the injured tissues. However, different forms of 2D graphene, are limited by themselves in recreating the soft and flexible three-dimensional (3D) tissue microenvironment conducive for myoblast proliferation and differentiation and warrants further processing into 3D structures. Several studies have fabricated highly interconnected and porous graphene aerogels (Qiu et al., 2014), and other nanocomposites such as graphene with PLGA (Ahadian, Ostrovidon et al., 2013; Ahadian, Ramalingam et al., 2013; Jun, Jeong, & Shin, 2009; Shin et al., 2015). However, most of the nanocomposite approaches involve bulk mixing of polymer with graphene and the resulting architecture is limited in recapitulating essential biophysical features of ECM (Chaudhuri et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2014; Qiu et al., 2014; Wan et al., 2015). In a previous study, we have shown myoblast-instructive potential of graphene–polycaprolactone (PCL) electrospun nanocomposites (Patel, Xue et al., 2016). However, these electrospun nanocomposites did not possess multiscale hierarchy and aligned architecture for contact guidance. In another study, we have demonstrated synergistic effect of nanoroughness, multiscale hierarchy, and aligned fibrous architecture engineered into carbon nanotube-based hierarchical scaffolds to promote myogenesis (Patel, Mukundan et al., 2016). These studies from our group have established influence of various biophysical features on myogenesis separately.

With the ability to precisely control their physicochemical properties and ease of integration of nanomaterials, hydrogels have emerged as a key platform in soft tissue engineering applications such as skeletal muscle (Zhang & Khademhosseini, 2017). They are popular biomaterials for providing ideal microenvironment for initial cell survival and proliferation. Hydrogels can be engineered to incorporate biophysical factors without compromising their soft and elastic mechanical properties. This potentially enables to overcome the major limitations of other scaffold-based approaches in skeletal muscle tissue engineering. However, novel strategies are required to achieve a combination of biophysical factors and complex hierarchical architectures simultaneously (Slaughter, Khurshid, Fisher, Khademhosseini, & Peppas, 2009).

In this study, we set out to combine individual advantages of polysaccharide hydrogels and graphene to develop conductive nanocomposite hydrogel films with hierarchical and aligned fibrous structure. The resulting biomaterial exhibited biomimetic biophysical features, specifically, aligned fibrous structure for contact guidance, compliant mechanical properties, and superior electrical conductivity. We selected chitosan (CHT) and gellan gum (GG) as polysaccharides of choice due to their cytocompatibility (Duarte, Correlo, Oliveira, & Reis, 2016; Naderi-Meshkin et al., 2014; Stevens, Gilmore, Wallace, & in het Panhuis, 2016) and widespread applicability in tissue engineering applications (Coutinho et al., 2012, 2010; Rabanel, Bertrand, Sant, Louati, & Hildgen, 2006). Recently, we have demonstrated that when combined in a microfluidic channel, these two polysaccharides self-assemble at the molecular level forming multiscale hierarchical fiber bundles. Importantly, these fiber bundles mimic nano- to microscale features of native collagen (S. Sant et al., 2017) such as light/dark bands, fibrils and fibers. In the current study, we incorporated electrically conductive graphene into these fiber bundles to generate nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films. We hypothesized that the incorporation of graphene will enhance the electrical conductivity of CHT–GG hydrogel films and preserve already compliant mechanical as well as multiscale hierarchical properties. Further, the aligned fibrous film structure along with enhanced conductivity will guide differentiation of myoblast to form multinucleated myotubes.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Materials

Graphene (AO-2 nanopowder) was obtained from Graphene Super-market (Calverton, NY). CHT (C3646), GG (G1910), and acetic acid were all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO). Cell culture supplies including Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Mediatech Inc. (Manassas, VA) or Corning Inc. (Corning, NY) unless otherwise specified.

2.2 |. Particle size and zeta potential measurements for graphene–CHT dispersions

Graphene (0.01%, 0.05%, and 0.1% w/v) was dispersed in CHT solution (1% w/v) in aqueous acetic acid solution (1% v/v). The particle size (hydrodynamic diameter) of graphene–CHT dispersion was measured by dynamic light scattering using a Malvern Zetasizer 3000 purchased from Malvern Panalytical (Malvern, UK). Before measurement, graphene–CHT dispersions were freshly prepared and sonicated at 10% amplitude for 10 min using Sonic Dismembrator (Model 500; Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH). The surface charge of all dispersions (with or without graphene) in deionized water was determined by Malvern Zetasizer 3000.

2.3 |. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Morphology of graphene and graphene–CHT dispersions were confirmed using TEM (Jeol 1011; Jeol, Tokyo, Japan) operated at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV. The particle dispersion was imaged without any staining.

2.4 |. Fabrication of nanocomposite fibrous films

Graphene–CHT dispersions with different graphene concentrations (0.01%, 0.05%, and 0.1%w/v) were allowed to self-assemble with GG solution (1%w/v) in deionized water in a custom-designed microfluidic chamber. Programmable syringe pumps (BS8000; Braintree Scientific Inc., Braintree, MA) were used to program the flow rates at 50 mL/h at room temperature. Ninety hydrogel fibers were collected to prepare a bilayer nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel film. These fibrous hydrogel films were allowed to air dry in a desiccator for 2 days and stored at room temperature until further use. Control films were fabricated using CHT and GG solutions without graphene following the same procedure except addition of graphene and sonication. In the following sections, CHT–GG hydrogel films without graphene are referred to as “control CHT–GG films” while graphene-containing CHT–GG films are referred to as “nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films.”

2.5 |. Contact angle measurement

The wettability of fibrous hydrogel films with different concentrations of graphene was determined by contact angle measurements. The contact angles were measured using VCA 2000 video contact angle goniometer (AST Products, Billerica, MA). A droplet of deionized water was deposited on the fibrous hydrogel film using a 21-G needle. The contact angles were determined by VCA Software (VCA Technology Ltd, Surrey, UK) (n = 4).

2.6 |. Electrochemical Characterization

Electrical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was used to study the electrical impedance of graphene-containing nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films (n = 2). The experiment was carried out in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) with a Potentiostat (FAS2/Femtostat) equipped with Gamry Framework Software (Gamry Instruments, Warminster, PA). A three-electrode system consisting of the hydrated nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel (4 h in DPBS) as working electrode, a platinum wire counter electrode, and a silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) reference electrode was used for the measurement.

2.7 |. Light microscopy

Light microscopy of dry fibrous hydrogel films and C2C12 cell-seeded fibrous hydrogel films was performed using Zeiss Primo Vert microscope and images were acquired using Zen software (Zen 2012; Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Oberkochen, Germany).

2.8 |. Mechanical testing

The mechanical properties of hydrated nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films were evaluated using uniaxial tensile testing with a mechanical testing system (ADMET, MTEST, Quattro, Norwood, MA) as described earlier (n = 3; Patel, Xue et al., 2016). Nanocomposite fibrous films (20×5 mm) were stretched until they break at a constant jogging rate of 10 mm/min. The stress (MPa) was obtained by dividing the applied force (N) with cross-section area (mm2) and the percentage elongation (% strain) was obtained by using ((L – L0)/L0× 100), in which L0 was considered as initial gauge length and L0 was considered as instantaneous gauge length. Ultimate tensile strength (UTS) was recorded as the maximum stress at the sample failure. Similarly, toughness was calculated as the maximum energy (kJ/m3) required to break the sample. Toughness was calculated from stress–strain curves using OriginPro 6 software (OriginLab, Northampton, MA). Young’s modulus was calculated from the linear stress–strain curve between 5% and 15% strain.

2.9 |. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Surface characterization of fractured hydrogel films was carried out using SEM (Jeol 9335 Field Emission SEM; JEOL, Peabody, MA; Patel, Mukundan et al., 2016). Fractured hydrogel films were air dried after mechanical testing before SEM imaging. Dried samples were sputter-coated using 5 nm of gold–palladium using Cressington 108 auto sputter coater (Cressington Scientific Instruments, Wat-ford, UK). Images were obtained using accelerated voltage of 3 kV and a working distance of 8 mm.

2.10 |. C2C12 mouse myoblast culture

The C2C12 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% v/v of heat inactivated FBS and 1% v/v antibiotic (Penicillin and Streptomycin). This media is referred as “growth media.” Differentiation media was prepared by supplementing DMEM with 2% v/v horse serum (HyClone™, GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Marlborough, MA) and 1% v/v antibiotic (Penicillin and Streptomycin). The cells were cultured in T75 or T175 flasks in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2. Fresh media was replaced every 2 days and cells were split 1:3 at 70% confluence.

2.11 |. Cell seeding on fibrous hydrogel films

Fibrous hydrogel films with an area of 0.25 cm2 were sterilized for an hour in isopropanol under ultraviolet light. The fibrous hydrogel films were seeded with C2C12 cells at a seeding density of 90,000 cells/film in 24-well plate. Each fibrous hydrogel film was transferred into a new well after 1-day incubation to remove nonadherent cells. Myoblasts were cultured in growth media for 6 days for cell aggregate area study. Myoblasts were cultured in growth media for 14 days for metabolic activity study while they were cultured for 3 days in growth media followed by additional 11 days in differentiation media for differentiation study.

2.12 |. Metabolic activity of cells

The metabolic activity of cells seeded on fibrous hydrogel films was measured using the alamarBlue® assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) over 14 days. AlamarBlue solution (10% v/v) was prepared in complete growth media and incubated (500 μl) with cell-seeded fibrous hydrogel films and for 4 h at 37°C. The fluorescence intensity was measured at excitation/emission wavelength of 530/590 nm using the microplate reader (Synergy HT; BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT). The wells without cells containing only alamarBlue solution in media were used as process controls for background fluorescence correction.

2.13 |. Immunofluorescence staining

Cell-seeded fibrous hydrogel films were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min and washed three times with DPBS followed by the permeabilization with DPBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and blocking in DPBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and 5% BSA for 1 h at room temperature. The fibrous hydrogel films were then incubated with the primary antibody against myosin heavy chain (MHC; MF-20, 1:50; DSHB, Iowa City, IA) overnight at 4°C and washed three times with DPBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100. The fibrous hydrogel films were then stained with secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG, A-11059, 1:200; Molecular Probes® Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 1 h at room temperature followed by three times washing with DPBS. The cell nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

2.14 |. Confocal microscopy

Confocal images were obtained using inverted confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus Fluoview 1000; Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Lasers of 488- and 633-nm wavelength were used. Objective lens of ×20 was used to acquire the z-stack images with 5 μm thickness of each z-slice. Data are presented as maximum intensity projection of the z-stack.

2.15 |. Image analysis

ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD) was used for quantification of light microscopy images. Images were first converted into 8 bits and then the threshold was set such that only aggregate areas showed the contrasting color. ROI manager was used to pick the areas for measurement of aggregate areas. Ratio of total cell aggregate area to the total area of the fibrous hydrogel films in each image (4× objective) was taken, which is considered as the percentage cell aggregate area. For quantification, n = 3 replicates of each type of films with at least two images per replicate were considered.

2.16 |. Statistical analysis

The data are represented as mean ± standard deviation (n is noted under each method and figure legends). The statistical significance between multiple groups was analyzed using one- or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the multiple comparisons were carried out using Tukey’s post hoc analysis (GraphPad Prism 6, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3 |. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 |. Characterization of graphene and graphene–CHT dispersions

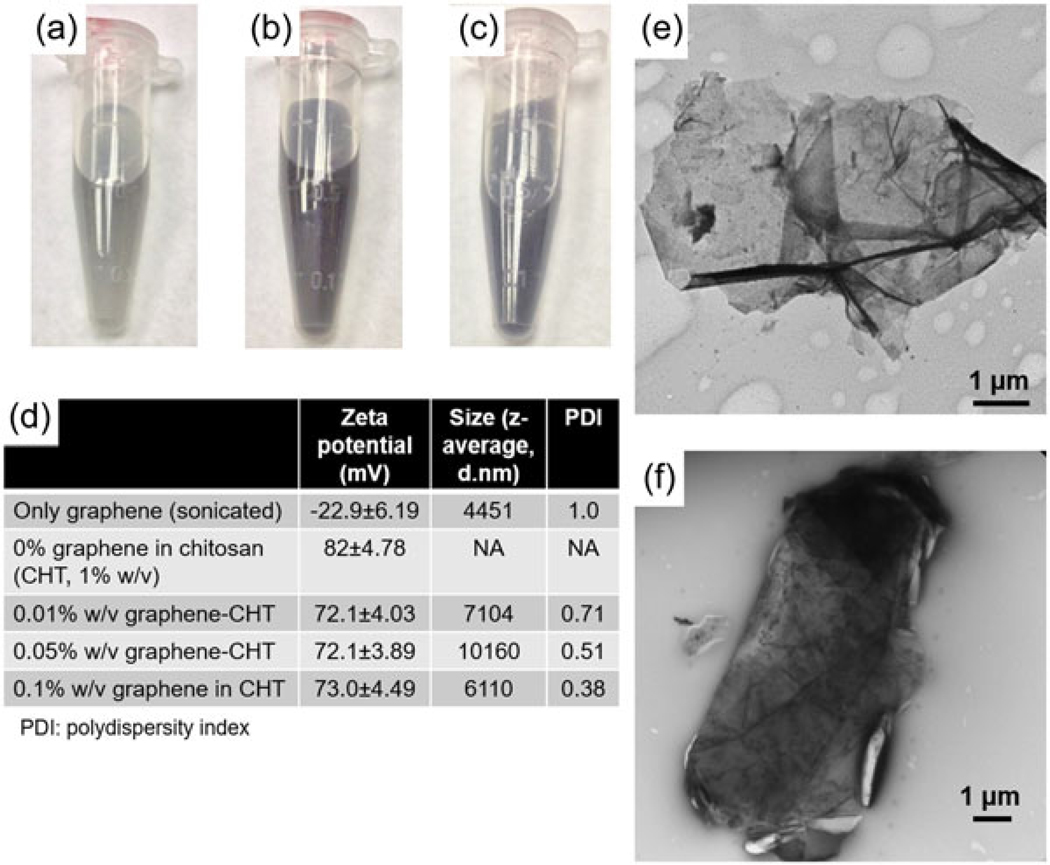

Various concentrations of graphene (0.01%, 0.05%, and 0.1% w/v) were uniformly dispersed in 1% w/v CHT solution by sonication as shown in Figure 1a–c. The 0.05% and 0.1% graphene dispersions were darker in color as compared with 0.01% graphene dispersion. The slightly darker color of 0.05% dispersion as compared with 0.1% dispersion could be attributed to more aggregation of graphene particles in 0.05% solution evident from larger particle size of 0.05% graphene dispersion (Figure 1d). Indeed, the particle size of graphene dispersed in CHT solution increased as compared to the graphene dispersed in water possibly due to formation of nonuniform sized loose aggregates in viscous CHT solution. This is also evident from high polydispersity indices (PDI) of these dispersions. Another reason for high PDI could be that the observed aggregate sizes are close to the upper detection limits of the Zetasizer. Graphene suspension in deionized water revealed negative zeta potential while CHT solution alone had positive zeta potential (Figure 1d). Because of the presence of opposite charges, graphene was mixed with 1% w/v solution of CHT to facilitate uniform dispersion due to the electrostatic interaction. As expected, dispersion of different concentration of graphene in CHT resulted in reduced zeta potential of the dispersion (Figure 1d). TEM of the graphene–CHT dispersion was performed to assess the morphological changes in graphene sheets due to the presence of CHT. All three concentrations of graphene–CHT dispersion showed similar morphology of graphene. A representative image of 0.05% graphene–CHT is shown in Figure 1f, which did not show irregular edges as seen in suspension of (graphene alone) in ethanol (Figure 1e).

FIGURE 1.

Characterization of graphene nanosheets and graphene–chitosan (CHT) dispersion. Photographic pictures of graphene–CHT dispersion of 0.01% w/v (a), 0.05% w/v (b), and 0.1% w/v (c) dispersion. (d) Values of zeta potential, average hydrodynamic diameter, and polydispersity index (PDI). (e) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of graphene sheet, showing morphology of the graphene sheets in the original form. (f) TEM image of 0.05% w/v graphene in 1% w/v CHT solution. Scale bars represent 2 μm

3.2 |. Characterization of nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films

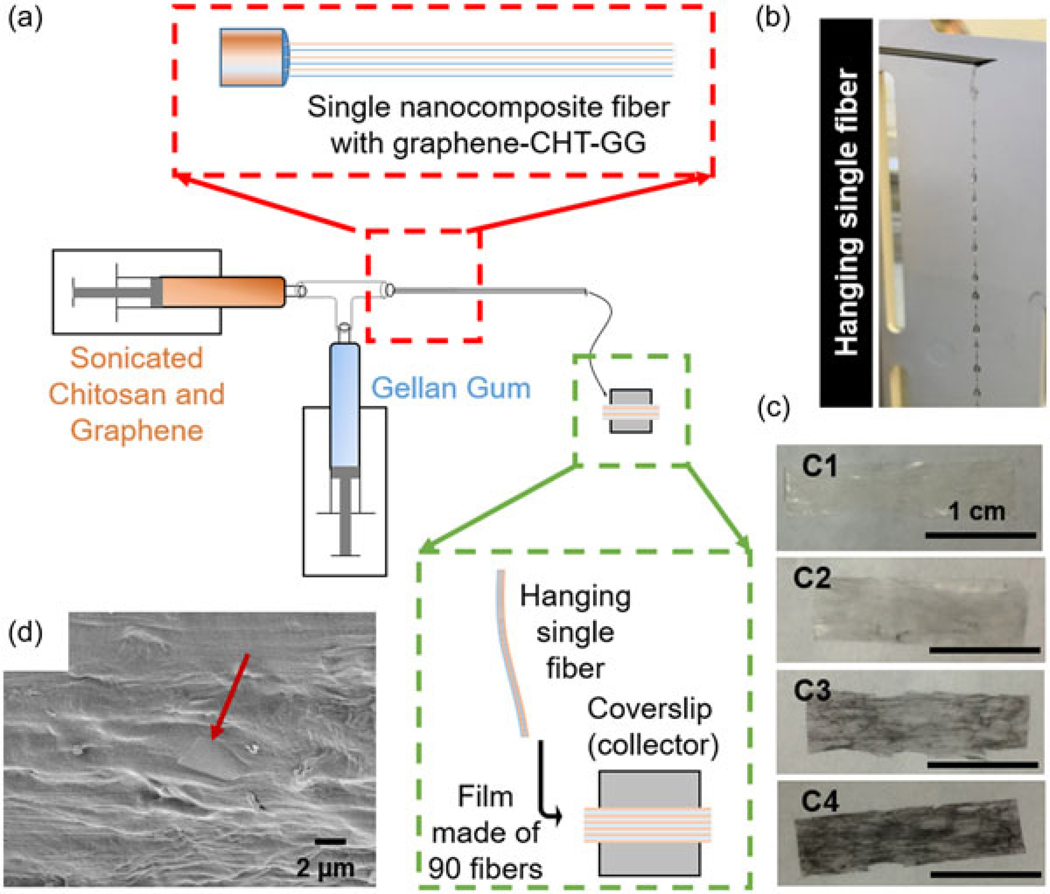

When graphene–CHT dispersions were allowed to react with GG in a microfluidic chamber, they self-assembled forming fiber bundles as reported earlier (S. Sant et al., 2017). In our previously reported work, we have reported and characterized the self-assembly of CHT and GG into a single fiber with multiscale hierarchy from nano- to microscale. In this study, we report collection of multiple such fibers to obtain a bilayer film, with graphene as an added filler. The schematic in Figure 2a depicts a modified method of preparing fibers in which two programmable pumps infuse sonicated graphene–CHT and GG solutions at 60°C. The red box in Figure 2a shows that the long needle helps to align self-assembled nanofibrils that make up a single fiber. The green box shows the manual collection and alignment of individual fibers (approximately 90 fibers) to form a film. Figure 2b shows a single fiber, made of aligned fibrils, hanging at the tip of the needle. Thus, each hydrogel film is composed of several nanocomposite hierarchical fibers as building blocks. Fiber formation was not observed for graphene concentration >0.1% w/v. For graphene–CHT dispersions (0–0.1% w/v), multiple fibers were collected forming fibrous hydrogel film containing graphene. Hence-forth, these nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films are abbreviated based on the concentration of graphene used during the fabrication. For example, fibrous hydrogel films made with 0.01% graphene are described as 0.01% graphene films hereafter. Figure 2c1–c4 shows macroscopic appearances of fibrous hydrogel films. Moreover, graphene sheets can be seen on the surface of the nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel film (Figure 2d) in a SEM image, indicating that the graphene sheets are not just embedded inside the hydrogel films but are also present on the film surface.

FIGURE 2.

Fabrication of fibrous nanocomposite films. (a) Schematic of the film fabrication assembly with programmable syringe pumps, a custom-designed microfluidic chamber and a long needle. The red box shows magnified area at the junction of the microfluidic chamber and long needle while the green box shows magnified area at the fiber collection. (b) Single nanocomposite fiber hanging at the tip of the long needle before collection. (c1–c4) Photographic picture of control CHT–GG film, 0.01%, 0.05%, and 0.1% graphene–CHT–GG film, respectively. Scale bars represent 1 cm. (d) Scanning electron microscopy image of graphene sheet (indicated with red arrow) oriented in horizontal direction near the surface of the film. CHT: chitosan; GG: gellan gum

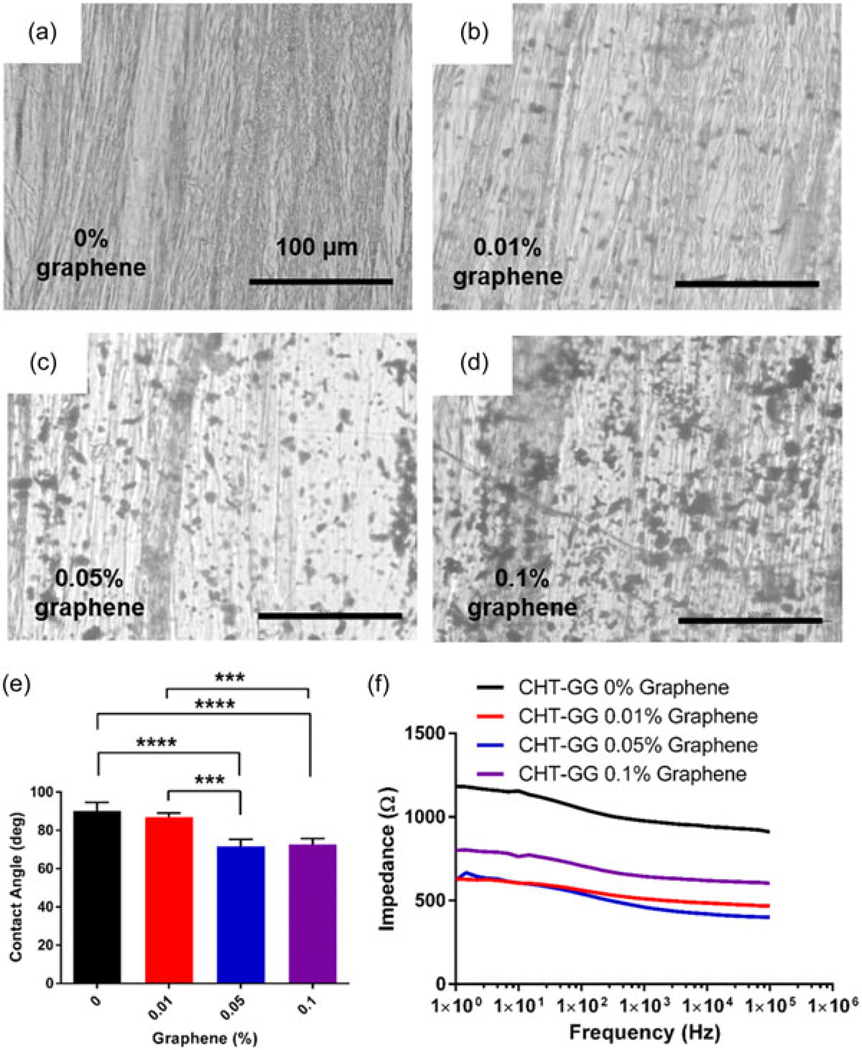

Control CHT–GG films without graphene showed presence of aligned fibers (Figure 3a). Graphene nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films showed even distribution of graphene throughout the film in addition to aligned fibers (Figure 3b–d). These observations showed minimal influence of concentration of graphene up to 0.1% on the bottom-up self-assembly of fibers and thus, formation of nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films. Thus, this self-assembly-based fabrication method yielded reproducible fibrous hydrogel films with uniform distribution of graphene. Presence of graphene sheets on the surface (Figure 2d) may enhance the surface nanoroughness of the nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films, leading to change in contact angle as well as cell adhesion and spreading. These properties along with fiber alignment at multiple length-scale could provide contact guidance for the myoblasts to differentiate into myotubes and further, into functional muscle bundles (Patel, Mukundan et al., 2016). In our previous study, graphene–PCL electrospun scaffolds were shown to stimulate myoblast differentiation, however, these electrospun scaffolds lack multiscale hierarchy and aligned unidirectional fibers (Patel, Xue et al., 2016). In this study, use of oppositely charged polysaccharides and graphene enabled bottom-up self-assembly in a microfluidic chamber, leading to nano- to microscale structural hierarchy as well as unidirectional fibrous architecture with uniform distribution of graphene. Moreover, the self-assembly process based on electrostatic interactions between positively charged CHT and negatively charged GG and graphene obviated the need for toxic cross-linking agents such as glutaraldehyde (Olde Damink et al., 1995), providing a key biocompatibility advantage over hydrogels prepared by traditional chemical cross-linking (Edwards, Di, & Dye, 2007).

FIGURE 3.

Characterization of nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films. Light microscopy images for (a) control CHT–GG film, (b) 0.01% graphene film, (c) 0.05% graphene film, and (d) 0.1% graphene film showing uniform distribution of graphene throughout the films, scale bars represent 100 μm, (e) contact angle measurements of different concentration of graphene nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films and control CHT–GG films (n = at least 4), (f) electrical impedance spectroscopy from 1 to 100,000 Hz. It shows lower impedance for all nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films relative to control CHT–GG films. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way analysis of variance and Tukey’s post hoc test. ***p < 0.005, ****p < 0.0001. CHT: chitosan; GG: gellan gum

Wettability of the surface plays an important role in modulation of initial cell–material interaction. Hence, surface wettability of the films was characterized by the contact angle measurement. Interestingly, incorporation of graphene in CHT–GG significantly reduced the contact angle (Figure 3e) of control CHT–GG films from about 90° to about 70° for 0.01% and 0.05% graphene films, respectively. However, further increase in graphene concentration from 0.05% to 0.1% did not change the contact angle significantly. The observed reduction in contact angle is in line with our observations with graphene–PCL scaffolds (Patel, Xue et al., 2016), which showed reduced contact angle as compared to electrospun PCL scaffolds without graphene. According to the published reports, contact angle around 70° is considered optimum to facilitate cell–material adhesion (Nuttelman, Mortisen, Henry, & Anseth, 2001; Tamada & Ikada, 1993).

Electrical conductivity is another important factor that can affect myoblast growth, differentiation, and formation of contractile muscle tissue (Ahadian, Ramón-Azcón, Chang et al., 2014; Ahadian, Ramón-Azcón, Estili et al., 2014). Uniform graphene distribution within the material has been shown to improve the electrical conductivity of nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films (Annabi et al., 2016; Heidari et al., 2017; Patel, Xue et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2017). In our study, EIS spectra (Figure 3f) showed that within the frequency range measured, the impedance magnitude is relatively insensitive to frequency. In this region, majority of the impedance comes from resistance of the circuit (inversely related to the conductivity of the electrode and electrolytes). Reduction in impedance magnitude was observed across all nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films relative to control CHT–GG film. This indicated that the graphene addition improves conductivity of the hydrogel up to 0.05% graphene concentration in nanocomposite films. The 0.1% graphene solution increased the formation of aggregates in CHT–GG fibers, which could be responsible of increase in the impedance. In a similar study, Jo et al. (2017) observed decrease in impedance values with reduced graphene oxide and polyacrylamide hydrogels as compared to the hydrogel without reduced graphene oxide.

3.3 |. Uniaxial mechanical characterization of the nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films

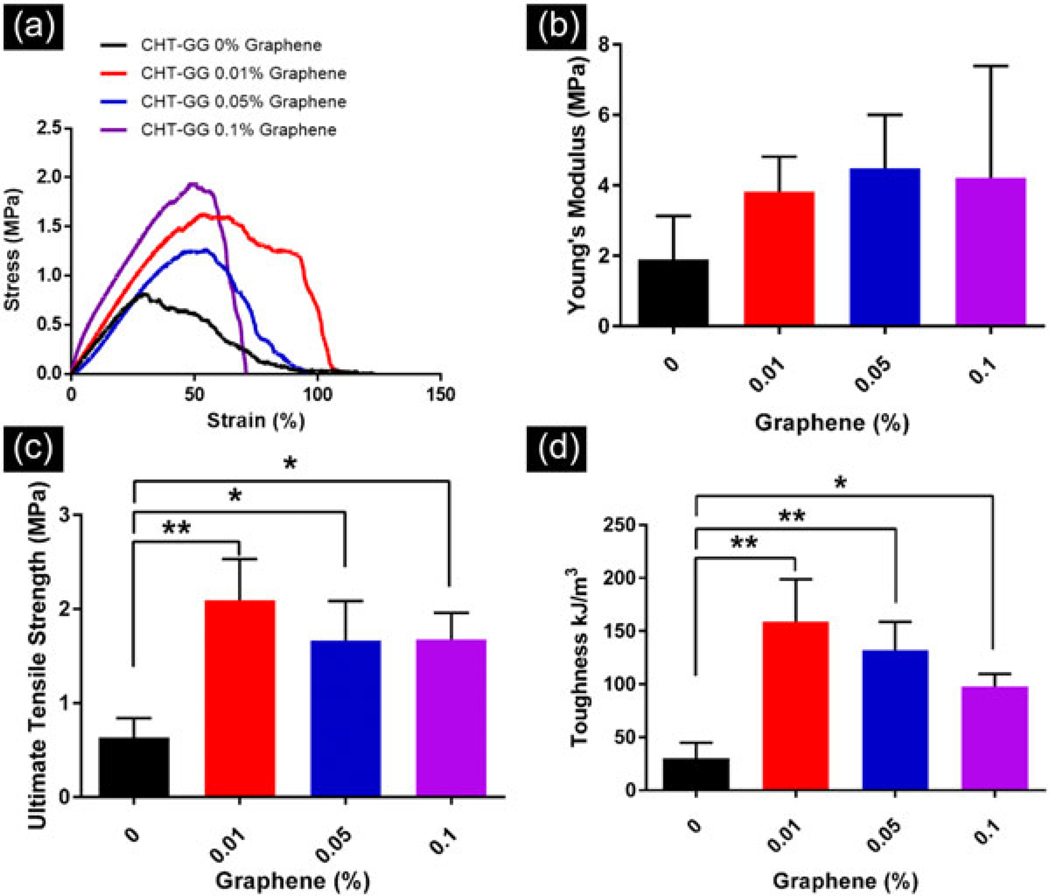

Conventional hydrogels often lack suitable mechanical strength to sustain dynamic in vivo microenvironment. Therefore, it is desirable to improve tensile property of hydrogels for bearing the load at the damaged tissue area for application as a skeletal muscle graft material. Therefore, we measured the effect of graphene incorporation on the mechanical properties of aligned CHT–GG hydrogels. Representative stress versus strain curves for control CHT–GG films and three nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films are shown in Figure 4a. Except for 0.1% graphene films, other nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films showed similar elongation (80–120%) suggesting their comparable ductility.

FIGURE 4.

Uniaxial mechanical characterization of the fibrous hydrogel films. (a) Representative stress–strain curves for different concentration of graphene in the nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films and control films; (b) average Young’s modulus values for n = 3 films per film type; (c) average ultimate tensile strength values for n = 3 films per film type; (d) average toughness values for n = 3 films per film type. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way analysis of variance and Tukey’s post hoc test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005. CHT: chitosan; GG: gellan gum

Young’s moduli (Figure 4b) of all hydrogel films were found to be similar without any statistically significant differences among nanocomposites and control CHT–GG films (p > 0.05, one-way ANOVA). This indicates that incorporation of graphene nanosheets does not impact the elastic properties of CHT–GG hydrogel films. Moreover, these Young’s moduli values are in the similar range of decellularized matrices obtained from different skeletal muscles such as small intestine submucosa (Feng et al., 2010) and bladder (Corona et al., 2012).

Nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films showed significantly higher UTS as compared to control CHT–GG films (Figure 4c). This could be due to the addition of graphene nanosheets, which may act as a filler to reinforce the overall mechanical strength (Annabi et al., 2016; Eslami et al., 2014). Previously reported graphene–PCL electrospun scaffold from our group showed opposite trend as compared to nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films reported in this study. Incorporation of graphene within PCL decreased its tensile properties as compared to PCL electrospun scaffolds, whereas in this study, incorporation of graphene during the electrostatic cross-linking of CHT, GG, and graphene reinforced tensile properties of the hydrogel films without significantly changing the elasticity. This can be attributed to the characteristic electrostatic self-assembly of the three materials in a microfluidic chamber unlike electrospinning of the physical blends of graphene and PCL.

To study the resistance of fibrous hydrogel films to the fracture under tensile stress, toughness values were calculated from stress versus strain curves. All nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films showed significantly higher toughness than control CHT–GG films. The overall trend among all films was similar to that observed for UTS. Together, uniaxial mechanical testing indicated improved stress bearing property in all nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films compared to control CHT–GG films.

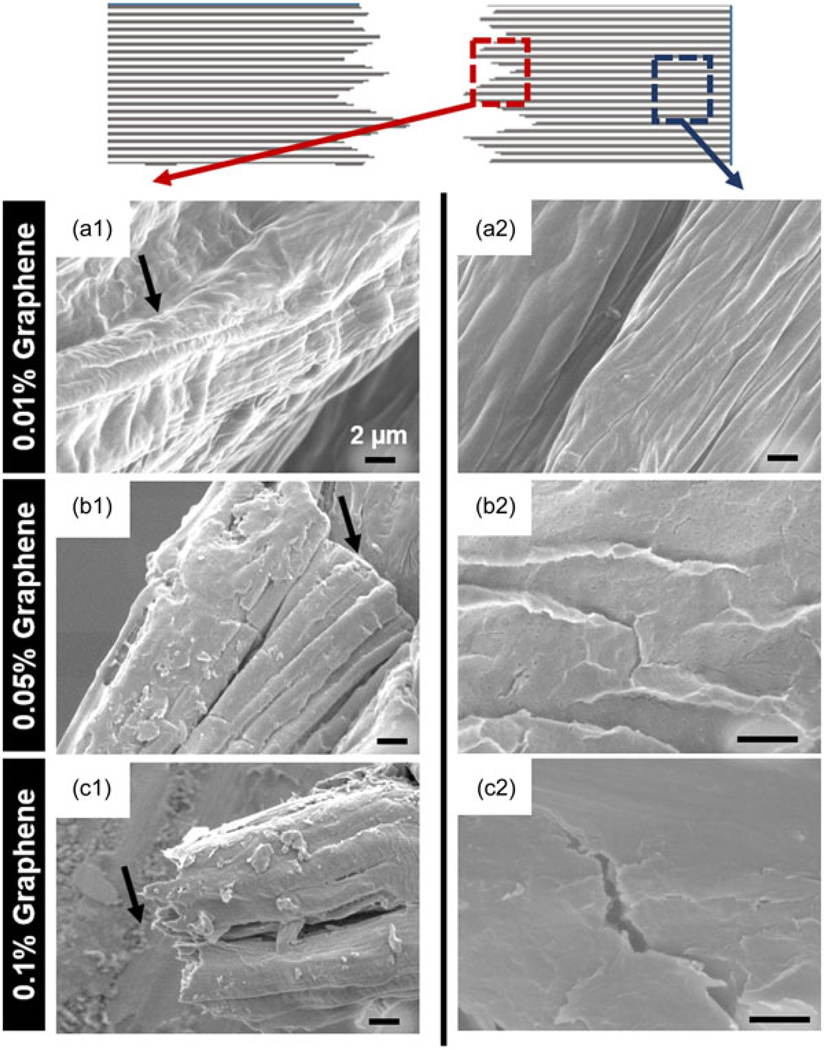

Following uniaxial tensile testing, fractured nanocomposite hydrogel films were imaged with SEM. As shown in the schematic in Figure 5, SEM images of the fractured fibrous hydrogel films were acquired from two different areas namely, near the fracture point and away from the fracture point to analyze the stress distribution and the effect of strain on the structure of the fibrous hydrogel films. As shown in Figure 5a1, 0.01% graphene film showed formation of wavy wrinkles near fracture point as indicated by a black arrow. However, as the concentration of graphene increased to 0.05%, the fibrous hydrogel films showed smooth, surfaces without wrinkles (black arrow in Figure 5b1). On the other hand, 0.1% graphene films showed splintered fracture with sharp edges (black arrow in Figure 5c1). When the film area away from the fracture (marked with blue dotted box in the schematic) was imaged, 0.01% graphene films showed no crack formation and fibrous structure of the nanocomposite films was found to be intact following fracture (Figure 5a2). However, 0.05% graphene films showed different response to the application of strain. These films showed multiple small cracks in the area farther to the fracture point and formation of flakes near these tiny cracks (Figure 5b2). Interestingly, 0.1% graphene films revealed larger, splintered, and brittle cracks (Figure 5c2). Our observation of different fracture behaviors could be due to the effect of differential interaction between crystalline graphene phase and soft hydrogel phase as recently reported by Ford and colleagues (Ford et al., 2018). In accordance with this recent study, our results suggest that at lower graphene concentrations, the soft hydrogel phase aligns in the direction of applied stress, whereas at higher graphene concentrations, hard phase of graphene dominates, resulting in brittle fracture as well as crack formation in the area farther from the fracture. Mechanical properties of target muscle site vary depending on the specific anatomical sites. For example, Morrow, Haut Donahue, Odegard, and Kaufman (2010) characterized skeletal muscles from various anatomical sites of New Zealand white rabbits and reported Young’s modulus values ranging from 447 to 767 kPa for two different muscle sites tested with same protocol at 0.5% strain/s. Thus, to be versatile in its application, ideal graft material should account for such differences. In addition, to maintain the mechanical stability of the graft material during surgical procedures and during in vivo degradation after implantation, it is desirable to have initial mechanical properties of the tissue graft superior than those of the native tissues. In the current study, the moduli of nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films were greater than the values recorded from various muscle sites and may be beneficial in handling these hydrogel films during implantation as well as for withstanding the dynamic in vivo degradation process.

FIGURE 5.

Scanning electron micrographs following fracture during uniaxial mechanical properties testing (top view). Schematic on the top indicates the areas near fracture point with red dotted boxes which corresponds to the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images numbered with 1 (a1, b1, c1), blue dotted box indicates farther to fracture area which corresponds to the SEM images numbered with 2 (a2, b2, c2); (a) 0.01% graphene films; (b) 0.05% graphene films; (c) 0.1% graphene films. Scale bars represent 2 μm

3.4 |. Spreading and metabolic activity of C2C12 cells on the nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films

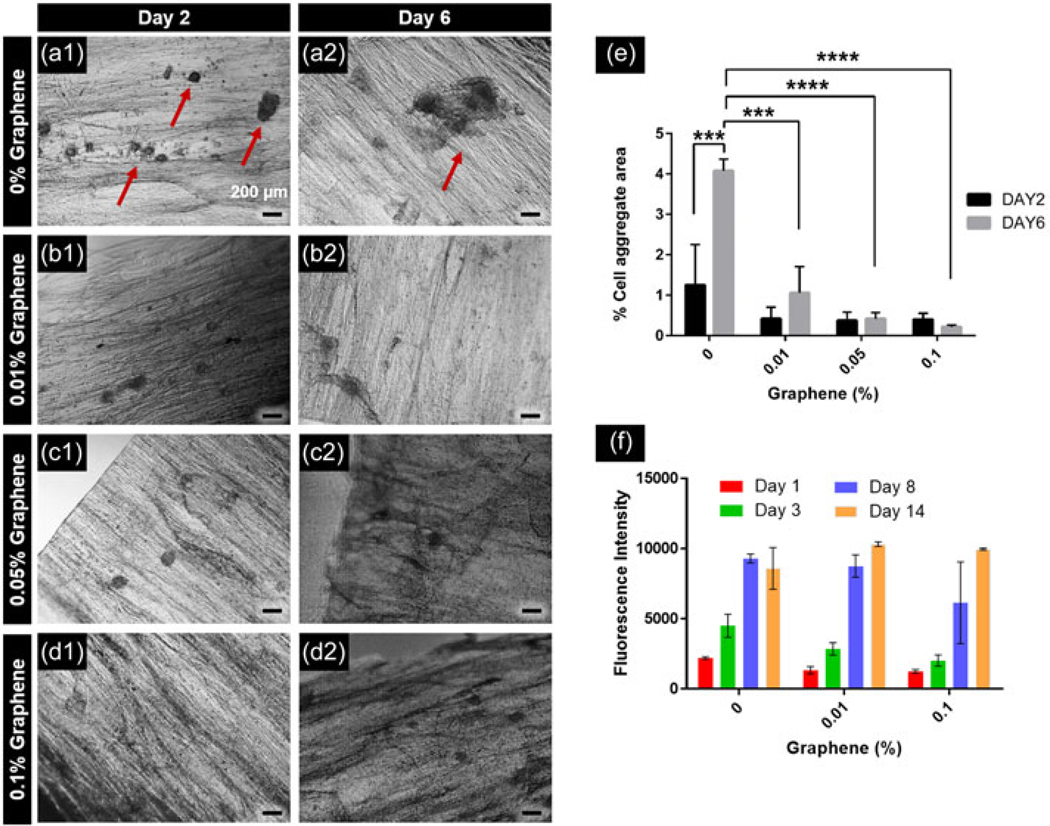

Ability of graphene to enhance myoblast spreading was assessed by measuring percentage of cell aggregate area to total film area as a function of time and graphene concentrations by image analysis (Figure 6a–e). Control CHT–GG films showed multiple aggregates occupying larger area of the films on Day 2 (Figure 6a1) compared to the nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films (Figure 6b1–d1). On Day 6, control CHT–GG films showed formation of larger aggregates (Figure 6a2) while nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films showed minimal change in the aggregate area over time and overall, lower aggregate area (Figure 6b2–d2) suggesting better spreading of myoblasts. As shown in Figure 6e, control CHT–GG films showed about four-fold increase (p < 0.0005) in cell aggregate area by Day 6 compared to the nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films. While CHT and GG are reported in literature as nonadherent materials for cells, our self-assembled CHT–GG hydrogel films improved myoblast retention on the films as evident from aggregates seen in Figure 6. However, consistent with the literature reports, CHT–GG films without graphene showed significantly more cell aggregation area than 0.01%, 0.05%, and 0.1% graphene–CHT–GG films. This suggests weak cell–matrix interaction while promoting cell–cell interaction and aggregate formation in control CH–GG films without graphene. Enhanced spreading observed with the addition of graphene can be attributed to reduction in contact angle (closer to 70°; Figure 3e), and increased electrical conductivity (Figure 3f), thereby possibly enhancing myoblast adhesion and spreading. Dong, Zhao, Guo, and Ma (2017) reported variant of materials with contact angle of 65°, 34°, and 12°, out of which material with 65° contact angle showed maximum myoblast attachment. Moreover, our previous study reported C2C12 attachment, spreading and differentiation on conductive electrospun scaffolds (Patel, Xue et al., 2016). Together, these results suggest that improved myoblast adhesion and spreading observed on nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films could be possibly due to improved wettability and electrical conductivity.

FIGURE 6.

Spreading and metabolic activity of cells on the nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films. (a1–d1) Cell aggregate formation in control CHT–GG film, 0.01%, 0.05%, and 0.1% graphene films, respectively, on Day 2 after C2C12 cell seeding; (a2–d2) cell aggregate formation in control CHT–GG film, 0.01%, 0.05%, and 0.1% graphene films, respectively, on Day 6 after C2C12 cell seeding, scale bars represent 200 μm, red arrows indicate cell aggregates; (e) quantification of images acquired from n = 3 samples of each type of films with at least two images; (f) the metabolic activity of C2C12 cells over a period of 14 days. Statistical significance was tested by two-way analysis of variance and Tukey’s post hoc test for the multiple comparison. ***p < 0.0005, ****p < 0.0001. CHT: chitosan; GG: gellan gum

The observed reduction of myoblast aggregation could also be due to the effect of graphene on myoblast growth and proliferation. Hence, we performed alamarBlue assay on 1, 3, 7, and 14 days to assess the viability and proliferation of myoblasts seeded on nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films. All the fibrous hydrogel films (0%, 0.01%, and 0.1% w/v graphene) showed increase in metabolic activity with time over 14 days (Figure 6f). There were no significant differences in the metabolic activity among control CHT–GG films and nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films. These results further confirm the cytocompatibility of graphene immobilized in the nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films. Taken together, these results show successful nanocomposite formation with graphene masking the reported cytotoxicity of the graphene alone (Goenka et al., 2014).

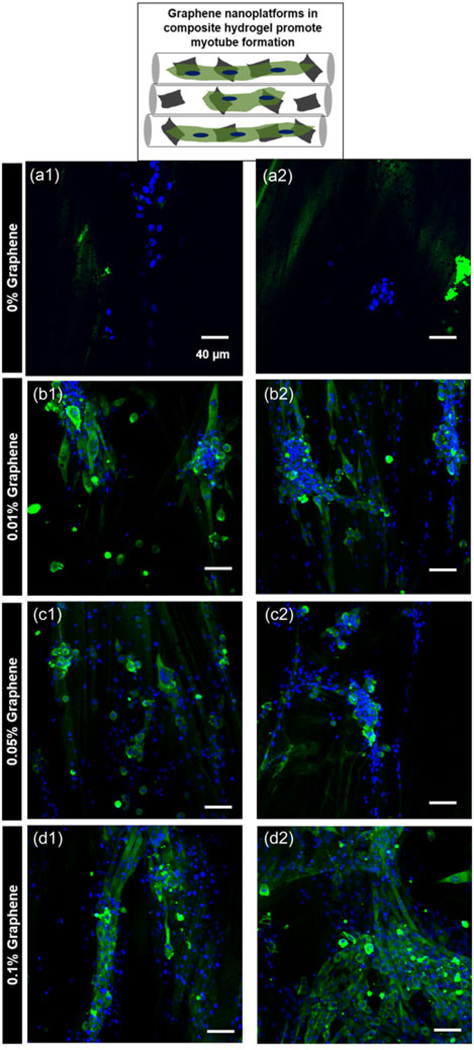

3.5 |. Differentiation of C2C12 myoblast into myotubes

Cell therapies intended for skeletal muscle regeneration are promising, however, poor survival of the implanted cells at the site of injury remains a significant challenge (Meregalli, Farini, Parolini, Maciotta, & Torrente, 2010; Vilquin, 2005). Biomaterial-based strategies can mitigate this challenge by improving the retention and survival of the cells at the injury site. Bioactivity of skeletal muscle graft biomaterial can be evaluated by its ability to promote the formation of multinucleated myotubes from myoblasts (Mukundan et al., 2015; Ostrovidov et al., 2014). To assess the potential of nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films for ex vivo functional maturation of myoblasts to myotubes, C2C12 myoblasts were cultured on the fibrous hydrogel films in growth media for the first 3 days, after which the culture media was switched to the differentiation media. Myoblasts seeded on all the fibrous hydrogel films showed positive immunofluorescence staining for MHC, which is a key marker for differentiation of myoblasts into multinucleated myotubes (Figure 7). Nanocomposite films with 0.01% (Figure 7b1, b2) and 0.05% graphene (Figure 7c1, c2) showed several areas with aggregated cell structures with positive staining for MHC. Interestingly, 0.1% graphene films showed relatively smaller aggregate areas and formation of elongated, multinucleated myotubes oriented parallel to each other and along the fiber alignment of the films (Figure 7d1, d2). Additionally, as shown in Figure 7, myoblast aggregation behavior was found to be consistent with our observation from aggregate area study shown in Figure 6e. These observations point to the likely role of bioactivity of graphene to facilitate differentiation of myoblasts to multinucleated myotubes. This could be attributed to the collective effect of nanoroughness, increased electrical conductivity, and optimum wettability of nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films.

FIGURE 7.

Differentiation of C2C12 myoblast into myotubes. C2C12 cells were seeded on the films and were allowed to proliferate for 3 days before switching to differentiation media culturing for 11 more days. Schematic on the top shows the role of graphene nanoplatforms in facilitating myotube formation. Merged confocal microscopy images of nuclei (Hoechst; blue) and myosin heavy chain (MHC; green) staining shows aggregated MHC-positive cells on (a1, a2) 0% graphene film; (b1, b2) 0.01% graphene film; (c1, c2) 0.05% graphene film; while (d1, d2) shows aligned myotubes on 0.1% graphene film

Recent research in skeletal muscle graft materials is shifting toward decellularized ECM (Fuoco et al., 2016; Rizzi et al., 2012) with the rationale to preserve and exploit the site-specific protein footprints for skeletal muscle regeneration (Porzionato et al., 2015). Although highly important, these approaches rely on uncharacterized mixture of cocktail of growth factors. The versatility of our fabrication approach offers flexibility to include defined mixture of bioactive factors, thus offering more control over the multiscale hierarchical structure as well as the material composition. In summary, the bottom-up self-assembly of the oppositely charged polysaccharides (CHT and GG) along with carbon nanomaterial (graphene) yielded nanocomposite hydrogel films with hierarchical aligned fibrous structure and highly conductive surfaces to guide initial alignment and myotube formation of cultured myoblasts.

4 |. CONCLUSIONS

Self-assembled graphene nanocomposite fibrous hydrogel films showed multiscale hierarchy and uniform distribution of graphene sheets inside the films. Addition of graphene significantly improved the UTS and toughness of the hydrogels without compromising their elastic modulus. Incorporation of graphene resulted in contact angles favorable for cell adhesion, and led to higher nanoroughness and electrical conductivity. These properties facilitated myoblast spreading, and led to unidirectional aligned myotube formation. Overall, synergistic influence of fiber alignment, wettability profile, enhanced electrical conductivity, and strong yet elastic mechanical properties facilitated differentiation of myoblasts into multinucleated myotubes along the direction of fibers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study is supported by funding support (S. S.) and Graduate Research Fellowship (A. P. and Y. X.) from the University of Pittsburgh, School of Pharmacy. The authors thank Shilpaa Mukundan and Vibishan Balasubramanian for their help with mechanical testing. Authors also thank Dr. Adam Feinberg, Carnegie Mellon University for providing C2C12 cells. The authors thank Mara Sullivan, Center for Biologic Imaging, University of Pittsburgh for help with TEM imaging.

Funding information

University of Pittsburgh, Grant/Award Number: Start-up funds

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Ahadian S, Ostrovidov S, Hosseini V, Kaji H, Ramalingam M, Bae H, & Khademhosseini A (2013). Electrical stimulation as a biomimicry tool for regulating muscle cell behavior. Organogenesis, 9(2), 87–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahadian S, Ramalingam M, & Khademhosseini A (2013). The emerging applications of graphene oxide and graphene in tissue engineering. In Ramalingam MWX, Chen G, Ma P, & Cui FZ (Eds.), Biomimetics (pp. 279–299. [Google Scholar]

- Ahadian S, Ramón-Azcón J, Chang H, Liang X, Kaji H, Shiku H, … Khademhosseini A (2014). Electrically regulated differentiation of skeletal muscle cells on ultrathin graphene-based films. RSC Advances, 4(19), 9534–9541. [Google Scholar]

- Ahadian S, Ramón-Azcón J, Estili M, Liang X, Ostrovidov S, Shiku H, … Khademhosseini A (2014). Hybrid hydrogels containing vertically aligned carbon nanotubes with anisotropic electrical conductivity for muscle myofiber fabrication. Scientific Reports, 4, 4271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annabi N, Shin SR, Tamayol A, Miscuglio M, Bakooshli MA, Assmann A, … Khademhosseini A (2016). Highly elastic and conductive human-based protein hybrid hydrogels. Advanced Materi- als, 28(1), 40–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae H, Chu H, Edalat F, Cha JM, Sant S, Kashyap A, … Khademhosseini A (2014). Development of functional biomaterials with micro- and nanoscale technologies for tissue engineering and drug delivery applications. Journal of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine, 8(1), 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri B, Bhadra D, Moroni L, & Pramanik K (2015). Myoblast differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells on graphene oxide and electrospun graphene oxide-polymer composite fibrous meshes: Importance of graphene oxide conductivity and dielectric constant on their biocompatibility. Biofabrication, 7(1), 015009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corona BT, Machingal MA, Criswell T, Vadhavkar M, Dannahower AC, Bergman C, … Christ GJ (2012). Further development of a tissue engineered muscle repair construct in vitro for enhanced functional recovery following implantation in vivo in a murine model of volumetric muscle loss injury. Tissue Engineering. Part A, 18(11-12), 1213–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho DF, Sant S, Shakiba M, Wang B, Gomes ME, Neves NM, … Khademhosseini A (2012). Microfabricated photocrosslinkable polyelectrolyte-complex of chitosan and methacrylated gellan gum. Journal of Materials Chemistry, 22(33), 17262–17271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho DF, Sant SV, Shin H, Oliveira JT, Gomes ME, Neves NM, … Reis RL (2010). Modified gellan gum hydrogels with tunable physical and mechanical properties. Biomaterials, 31(29), 7494–7502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong R, Zhao X, Guo B, & Ma PX (2017). Biocompatible elastic conductive films significantly enhanced myogenic differentiation of myoblast for skeletal muscle regeneration. Biomacromolecules, 18(9), 2808–2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte ARC, Correlo VM, Oliveira JM, & Reis RL (2016). Recent developments on chitosan applications in regenerative medicine, Biomaterials from nature for advanced devices and therapies (221–243). John Wiley & Sons Inc [Google Scholar]

- Edwards FC, Di Y, & Dye JF (2007). In vitro assessment of the cytotoxicity and inflammatory potential of glutaraldehyde as a crosslinking agent for protein scaffolds. Tissue Engineering, 13(7), 1711–1712. [Google Scholar]

- Eslami M, Vrana NE, Zorlutuna P, Sant S, Jung S, Masoumi N, … Khademhosseini A (2014). Fiber-reinforced hydrogel scaffolds for heart valve tissue engineering. Journal of Biomaterials Applications, 29 (3), 399–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng C, Xu Y-M, Fu Q, Zhu W-D, Cui L, & Chen J (2010). Evaluation of the biocompatibility and mechanical properties of naturally derived and synthetic scaffolds for urethral reconstruction. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. Part A, 94A(1), 317–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford AC, Gramling H, Li SC, Sov JV, Srinivasan A, & Pruitt LA (2018). Micromechanisms of fatigue crack growth in polycarbonate polyurethane: Time dependent and hydration effects. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials, 79, 324–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuoco C, Petrilli LL, Cannata S, & Gargioli C (2016). Matrix scaffolding for stem cell guidance toward skeletal muscle tissue engineering. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research, 11(1), 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goenka S, Sant V, & Sant S (2014). Graphene-based nanomaterials for drug delivery and tissue engineering. Journal of Controlled Release, 173, 75–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guven S, Chen P, Inci F, Tasoglu S, Erkmen B, & Demirci U (2015). Multiscale assembly for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Trends in Biotechnology, 33(5), 269–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidari M, Bahrami H, & Ranjbar-Mohammadi M (2017). Fabrication, optimization and characterization of electrospun poly(caprolactone)/gelatin/graphene nanofibrous mats. Materials Science and Engineering: C, 78, 218–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo H, Sim M, Kim S, Yang S, Yoo Y, Park J-H, … Lee JY (2017). Electrically conductive graphene/polyacrylamide hydrogels produced by mild chemical reduction for enhanced myoblast growth and differentiation. Acta Biomaterialia, 48(Suppl. C), 100–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun I, Jeong S, & Shin H (2009). The stimulation of myoblast differentiation by electrically conductive sub-micron fibers. Biomaterials, 30(11), 2038–2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerativitayanan P, Carrow JK, & Gaharwar AK (2015). Nanomaterials for engineering stem cell responses. Advanced Healthcare Materials, 4(11), 1600–1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwee BJ, & Mooney DJ (2017). Biomaterials for skeletal muscle tissue engineering. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 47, 16–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L, Marchant RE, Zhu J, & Kottke-Marchant K (2014). Extracellular matrix-mimetic poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels engineered to regulate smooth muscle cell proliferation in 3-D. Acta Biomaterialia, 10 (12), 5106–5115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meregalli M, Farini A, Parolini D, Maciotta S, & Torrente Y (2010). Stem cell therapies to treat muscular dystrophy progress to date. BioDrugs, 24(4), 237–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montesano S, Lizundia E, D’Angelo F, Fortunati E, Mattioli S, Morena F, … Martino S (2013). Nanocomposites based on PLLA and multi walled carbon nanotubes support the myogenic differentiation of murine myoblast cell line. ISRN Tissue Engineering, 2013, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow DA, Haut Donahue TL, Odegard GM, & Kaufman KR (2010). Transversely isotropic tensile material properties of skeletal muscle tissue. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials, 3(1), 124–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukundan S, Sant V, Goenka S, Franks J, Rohan LC, & Sant S (2015). Nanofibrous composite scaffolds of poly(ester amides) with tunable physicochemical and degradation properties. European Poly- mer Journal, 68, 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Naderi-Meshkin H, Andreas K, Matin MM, Sittinger M, Bidkhori HR, Ahmadiankia N, … Ringe J (2014). Chitosan-based injectable hydrogel as a promising in situ forming scaffold for cartilage tissue engineering. Cell Biology International, 38(1), 72–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novoselov KS, Geim AK, Morozov SV, Jiang D, Zhang Y, Dubonos SV, … Firsov AA (2004). Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science, 306(5696), 666–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuttelman CR, Mortisen DJ, Henry SM, & Anseth KS (2001). Attachment of fibronectin to poly(vinyl alcohol) hydrogels promotes NIH3T3 cell adhesion, proliferation, and migration. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research, 57(2), 217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olde Damink LHH, Dijkstra PJ, Van Luyn MJA, Van Wachem PB, Nieuwenhuis P, & Feijen J (1995). Glutaraldehyde as a crosslinking agent for collagen-based biomaterials. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine, 6(8), 460–472. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrovidov S, Hosseini V, Ahadian S, Fujie T, Parthiban SP, Ramalingam M, … Khademhosseini A (2014). Skeletal muscle tissue engineering: methods to form skeletal myotubes and their applications. Tissue Engineering Part B—Reviews, 20(5), 403–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel A, Mukundan S, Wang W, Karumuri A, Sant V, Mukhopadhyay SM, & Sant S (2016). Carbon-based hierarchical scaffolds for myoblast differentiation: Synergy between nano-functionalization and alignment. Acta Biomaterialia, 32, 77–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel A, Xue Y, Mukundan S, Rohan LC, Sant V, Stolz DB, & Sant S (2016). Cell-instructive graphene-containing nanocomposites induce multinucleated myotube formation. Annals of Biomedical Engineering, 44(6), 2036–2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porzionato A, Sfriso M, Pontini A, Macchi V, Petrelli L, Pavan P, … De Caro R (2015). Decellularized human skeletal muscle as biologic scaffold for reconstructive surgery. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 16(7), 14808–14831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu L, Liu D, Wang Y, Cheng C, Zhou K, Ding J, … Li D (2014). Mechanically robust, electrically conductive and stimuli-responsive binary network hydrogels enabled by superelastic graphene aerogels. Advanced Materials, 26(20), 3333–3337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabanel J-M, Bertrand N, Sant S, Louati S, & Hildgen P (2006). Polysaccharide hydrogels for the preparation of immunoisolated cell delivery systems In Marchessault RH, Ravenelle F, & Zhu XX (Eds.), Polysaccharides for drug delivery and pharmaceutical applications (pp. 305–339). Washington, DC: ACS Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi R, Bearzi C, Mauretti A, Bernardini S, Cannata S, & Gargioli C (2012). Tissue engineering for skeletal muscle regeneration. Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal, 2(3), 230–234. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozario T, & DeSimone DW (2010). The extracellular matrix in development and morphogenesis: A dynamic view. Developmental Biology, 341(1), 126–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sant S, Coutinho DF, Gaharwar AK, Neves NM, Reis RL, Gomes ME, & Khademhosseini A (2017). Self-assembled hydrogel fiber bundles from oppositely charged polyelectrolytes mimic micro-/nanoscale hierarchy of collagen. Advanced Functional Materials, 27(36), 1606273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sant S, Hancock MJ, Donnelly JP, Iyer D, & Khademhosseini A (2010). Biomimetic gradient hydrogels for tissue engineering. Cana- dian Journal of Chemical Engineering, 88(6), 899–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sant V, Goenka S, & Sant S (2015). Emerging applications of graphene in drug and gene delivery, Nanoparticles for biotherapeutic delivery (104–116). Future Science Ltd [Google Scholar]

- Schultz E, Jaryszak DL, & Valliere CR (1985). Response of satellite cells to focal skeletal muscle injury. Muscle and Nerve, 8(3), 217–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin YC, Lee JH, Jin L, Kim MJ, Kim YJ, Hyun JK, … Han DW (2015). Stimulated myoblast differentiation on graphene oxide-impregnated PLGA-collagen hybrid fibre matrices. Journal of Nanobio- technology, 13, 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter BV, Khurshid SS, Fisher OZ, Khademhosseini A, & Peppas NA (2009). Hydrogels in regenerative medicine. Advanced Materials, 21(32–33), 3307–3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens LR, Gilmore KJ, Wallace GG, & in het Panhuis M (2016). Tissue engineering with gellan gum. Biomaterials Science, 4(9), 1276–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamada Y, & Ikada Y (1993). Effect of preadsorbed proteins on cell adhesion to polymer surfaces. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 155(2), 334–339. [Google Scholar]

- Vilquin JT (2005). Myoblast transplantation: Clinical trials and perspectives. Mini-review. Acta Myologica, 24(2), 119–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan S, Peng J, Li Y, Hu H, Jiang L, & Cheng Q (2015). Use of synergistic interactions to fabricate strong, tough, and conductive artificial nacre based on graphene oxide and chitosan. ACS Nano, 9 (10), 9830–9836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Liu Z, Chen C, Shi K, Zhang L, Ju X-J, … Chu L-Y (2017). Reduced graphene oxide-containing smart hydrogels with excellent electro-response and mechanical properties for soft actuators. ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces, 9(18), 15758–15767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeong WY, Yu H, Lim KP, Ng KLG, Boey YCF, Subbu VS, & Tan LP (2010). Multiscale topological guidance for cell alignment via direct laser writing on biodegradable polymer. Tissue Engineering Part C–Methods, 16(5), 1011–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YS, & Khademhosseini A (2017). Advances in engineering hydrogels. Science, 356(6337), eaaf3627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]