Abstract

Background

Enhancing health equity has now achieved international political importance with endorsement from the World Health Assembly in 2009. The failure of systematic reviews to consider effects on health equity is cited by decision‐makers as a limitation to their ability to inform policy and program decisions.

Objectives

To systematically review methods to assess effects on health equity in systematic reviews of effectiveness.

Search methods

We searched the following databases up to July 2 2010: MEDLINE, PsychINFO, the Cochrane Methodology Register, CINAHL, Education Resources Information Center, Education Abstracts, Criminal Justice Abstracts, Index to Legal Periodicals, PAIS International, Social Services Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts, Digital Dissertations and the Health Technology Assessment Database. We searched SCOPUS to identify articles that cited any of the included studies on October 7 2010.

Selection criteria

We included empirical studies of cohorts of systematic reviews that assessed methods for measuring effects on health inequalities.

Data collection and analysis

Data were extracted using a pre‐tested form by two independent reviewers. Risk of bias was appraised for included studies according to the potential for bias in selection and detection of systematic reviews.

Main results

Thirty‐four methodological studies were included. The methods used by these included studies were: 1) Targeted approaches (n=22); 2) gap approaches (n=12) and gradient approach (n=1). Gender or sex was assessed in eight out of 34 studies, socioeconomic status in ten studies, race/ethnicity in seven studies, age in seven studies, low and middle income countries in 14 studies, and two studies assessed multiple factors across health inequity may exist.

Only three studies provided a definition of health equity. Four methodological approaches to assessing effects on health equity were identified: 1) descriptive assessment of reporting and analysis in systematic reviews (all 34 studies used a type of descriptive method); 2) descriptive assessment of reporting and analysis in original trials (12/34 studies); 3) analytic approaches (10/34 studies); and 4) applicability assessment (11/34 studies). Both analytic and applicability approaches were not reported transparently nor in sufficient detail to judge their credibility.

Authors' conclusions

There is a need for improvement in conceptual clarity about the definition of health equity, describing sufficient detail about analytic approaches (including subgroup analyses) and transparent reporting of judgments required for applicability assessments in order to assess and report effects on health equity in systematic reviews.

Plain language summary

How effects on health equity are assessed in systematic reviews of effectiveness

Health in all countries of the world is unevenly and, to some extent, unfairly distributed according to socioeconomic position. Health and longevity are highest for the richest, and decrease steadily with decreasing socioeconomic status. Avoidable and unfair inequalities have been termed health inequities. Enhancing health equity has now achieved international political importance with endorsement from the World Health Assembly in 2009. The failure of systematic reviews to consider effects on health equity is cited by decision‐makers as a limitation. Hence, there is a need for guidance on the advantages and disadvantages of how to assess effects on health equity in systematic reviews.

This review identified thirty‐four methodological studies in which collections of systematic reviews were examined. We identified four methodological approaches to assess the effects on health equity, a descriptive assessment in the reviews, a descriptive assessment of the trials included in the reviews, analytic approaches, and applicability assessment. However, the most appropriate way to address any of these approaches is unclear. There is a need for methodological guidance on how to assess effects on health equity in systematic reviews. Analysis of particular groups of populations need to be justified and reported in sufficient detail to allow their credibility to be assessed. There is a need for improved transparency of judgments about applicability and relevance to disadvantaged populations.

Background

Description of the problem or issue

Health differences between groups may be due to inequalities in factors such as socioeconomic characteristics. Health inequalities that are unfair and avoidable are classed as health inequities. Health inequities persist, and are worsening, across almost all health problems, both within and between countries. For example, people living in the poorest countries have a life expectancy that is at least 40 years shorter than for people living in the richest countries. Within a single city (Nairobi, Kenya), the mortality rate of children younger than 5 years is 15 per 1000 in high‐income areas and 254 per 1000 in the slums (World Health Report 2008). In an update on global trends on child mortality, inequality in under‐five mortality across sex and socioeconomic status is increasing in more countries than it is decreasing (You 2010).

The World Health Organization convened the Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) in 2006 and released its final report in 2008 to assess the evidence on taking action on reducing health inequity (Marmot 2008). The CSDH defined health inequity as "the poor health of poor people" both within countries and between countries as due to an "unequal distribution of power, income, goods, and services, globally and nationally, the consequent unfairness in the immediate, visible circumstances of people’s lives—their access to health care and education, their conditions of work and leisure, their homes, communities, towns, or cities—and their chances of leading a flourishing life" (Marmot 2008).

Such health inequalities need to be addressed, not only for moral and ethical reasons, but also for economic reasons (Sachs 2001). There is an increasing evidence‐base on the effectiveness of interventions for reducing health inequities, both within and between countries. For example, a recent systematic review, which assessed the effects of tobacco control interventions on the socioeconomic gradient in smoking, identified macro‐level policies that may reduce socioeconomic differences in smoking (Thomas 2008).

There is increasing acceptance that systematic reviews of the best available evidence are the foremost source of information on which to base evidence‐informed policy and practice (Lavis 2009). Indeed, this view has been endorsed by a World Health Assembly resolution, which was based on the Mexico Ministerial Statement on Health Research (58th World Health Assembly Resolution). A similar recommendation emerged during the Role of Science in the Information Society health conference (European Organization for Nuclear Research 2003) that was held as part of the World Summit of the Information Society in December 2003. The recommendation stressed the need for reliable evidence delivered in a timely manner and in the right format. Systematic reviews are a useful basis for decision making because they reduce the chance of being misled, increase confidence in results, and are an efficient use of time (Lavis 2006).

A recent study of policy maker perceptions found that policy makers increasingly consider systematic reviews as a useful source of knowledge to support decision making (Pope 2006). However, decision makers are interested not only in what works, but also in the costs and resources involved in implementation and ensuring continuity, the potential risks or adverse effects, and the distribution of benefit across sociodemographic factors (Lavis 2005). The lack of evidence on the distribution of effects and impact on health equity has been highlighted by policy makers as a major barrier to the use of systematic reviews as a basis for decision making (Petticrew 2004). Unequal benefits or harms across different socioeconomic or demographic population groups could contribute to worsening health equity (Tugwell 2006). In the context of reducing health inequities, decision‐makers from diverse organizations may be interested in evidence of effects of interventions on reducing health inequity such as non‐governmental organizations and human rights organizations, as well as government decision‐makers in ministries of health and other departments (e.g. financial and agricultural) (Marmot 2008).

Health inequities are defined by Margaret Whitehead as “differences in health which are not only unnecessary and avoidable but, in addition, are considered unfair and unjust” (Whitehead 1992). Assessing the effects of interventions on health equity is difficult because it requires a subjective judgment about both the avoidability and the fairness of the distribution of effects (Kawachi 1999). Hence, assessments of the distribution of effects of interventions across groups of people who may experience health inequities in both clinical trials and systematic reviews focus on differences in health effects that can be measured (Arblaster 1996; Gepkens 1996).

The Campbell and Cochrane Equity Methods Group has adopted the acronym PROGRESS‐Plus to identify dimensions across which health inequities may exist: Place of residence (urban/rural), Race/ethnicity, Occupation, Gender, Religion, Education, Socioeconomic status, and Social capital (Tugwell 2006; Evans 2003). The "Plus" in PROGRESS‐Plus refers to any additional factors across which health inequalities may exist such as age, disability, and sexual orientation (Kavanagh 2008). The "Plus" could also include factors such as the experience of sexual or physical abuse as a child, which may shape the experience of health inequity later in life.

Despite the demand for equity assessment by policy makers, these assessments are rare in systematic reviews. Only 1 out of 95 randomly sampled Cochrane Reviews assessed differences in effects across PROGRESS factors (Tsikata 2003). This was due to a lack of information in the included trials (only 10% reported differences across PROGRESS factors), as well as a lack of assessment by the review authors (Tsikata 2003).

Description of the methods being investigated

The different methods used to describe and assess effects on health inequalities in systematic reviews were investigated. Because health equity requires a subjective judgment about whether differences in health outcomes are unfair, this review focused on the assessment of health inequalities across PROGRESS‐Plus factors. We chose PROGRESS‐Plus as an organizing framework to assess dimensions across which health inequities exist since it is endorsed by the Campbell and Cochrane Equity Methods Group and also encompasses the factors suggested by the World Health Organization Commission on Social Determinants of Health (Tugwell 2010). We also assessed whether the authors of the included studies described inequalities in health outcomes as unfair and unjust.

There are a number of ways to measure health inequalities. For example, health inequalities can be expressed as the difference between the most and least advantaged groups in relative or absolute terms (Keppel 2005), or they can be expressed using more complicated indices such as the Gini index, concentration index (Koolman 2004), or benefit‐incidence estimate (Wagstaff 2005). The choice of method and comparator or reference group influences both the magnitude of the result and its interpretation (Keppel 2005). See Table 1 for selected methods of assessing effects on health inequalities.

1. Selected methods of assessing effects on health inequalities.

| Method | Calculation |

| Targeted approach | Evaluation of effect size in the disadvantaged population only (e.g. Cochrane Review on community animal health services for improving household wealth and health status of low income farmers by Curran 2006). |

| Relative difference (gap approach) | (advantaged ‐ disadvantaged)/advantaged |

| Absolute difference (gap approach) | advantaged ‐ disadvantaged |

| Gradient‐approach regression | Regression‐based index of relative effect across incremental categories of disadvantage. |

| Gradient‐concentration index | Twice the area between the concentration curve and the line of equality (45 degrees line), defined with reference to the concentration curve, which graphs health status on the y‐axis against categories of disadvantage on the x‐axis (World Bank). |

| Gradient or gap‐benefit incidence | Computes the distribution of public expenditure across different PROGRESS‐Plus groups according to actual utilization of services. |

| Gradient approach ‐ Gini index | Measure of inequality of income distribution, defined as the area between the line of equality and the Lorenz curve, with categories of PROGRESS on the x‐axis and percentage of total income on the y‐axis (Gastwirth 1972). |

PROGRESS‐Plus: Place of residence (urban/rural), Race/ethnicity, Occupation, Gender, Religion, Education, Socioeconomic status, and Social capital. "Plus" includes any other factors that are associated with decreased opportunities for good health such as age, disability, disease status or sexual preference.

How these methods might work

Relative or absolute differences for health inequalities measured over time can demonstrate either an increase or decrease in health inequalities for the same data, because relative measures are affected by the underlying rate of the reference group. A detailed example of this can be found in Table C of Keppel 2005. Economic measures of health inequalities, such as the Gini index, concentration index, and the benefit‐incidence ratio, may be too complex to interpret and require too many data points to be useful in the context of systematic reviews (Tugwell 2006). This methodology review sought to assess whether these methods have been used to assess health inequalities in empirical studies analyzing systematic reviews, and to explore the advantages and disadvantages of each method.

Why it is important to do this review

Despite the demand for health equity assessment in systematic reviews by policy makers and practitioners, there remains little empirical evidence on which of the different methods available for assessing health inequalities are have been used in the context of systematic reviews of effectiveness, and their advantages and disadvantages.

Objectives

We aimed to describe and assess the effects of using different methods to assess health inequalities in empirical research studies of systematic reviews of the effectiveness of interventions. Thus, we aimed to assess whether the authors of the systematic reviews included in the methodology studies presented results on the effects of the interventions for groups of people who could be classified as suffering from health inequity, across one or more of the sociodemographic factors of PROGRESS‐Plus.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included empirical studies of a cohort (more than one) of systematic reviews of health or non‐health interventions that assess effects on health across one or more socioeconomic and demographic factors defined by PROGRESS‐Plus. The empirical studies needed to assess whether authors of the included systematic review presented or discussed results on the effects of interventions for groups of people who could be classified as suffering from health inequity, across one or more of the sociodemographic factors of PROGRESS‐Plus. Empirical studies using qualitative or quantitative approaches were eligible.

Empirical studies could assess the effects of interventions that aim to decrease the category health inequity experienced by a group of people, such as interventions which aim to improve education opportunities or reduce poverty, if they measured effects on health outcomes of these interventions (Gakidou 2010). An example of an eligible study is an empirical study which assessed the the effects of community‐based tobacco control interventions for groups of people who could be defined as experiencing health inequity across sex, race/ethnicity or socioeconomic status in six Cochrane reviews (Ogilvie 2004).

We excluded individual systematic reviews assessing health inequalities as we aimed to assess methods for comparing health inequalities across different systematic reviews, rather than within an individual systematic review. Furthermore, including individual systematic reviews might introduce bias because they are less likely to report health inequalities analyses when no substantive differences are found (Chan 2004).

Overviews of systematic reviews synthesize evidence from multiple systematic reviews of interventions into one document (Cochrane Handbook 2009). Overviews of systematic reviews were eligible if they assessed effects of interventions for groups of people who could be classified as suffering from health inequity.

Types of data

We assessed data from published or unpublished empirical studies of a cohort of systematic reviews on the advantages, disadvantages and feasibility of methods used to assess effects of interventions in groups of people who could be defined as experiencing health inequity. We extracted data on the advantages and disadvantages (or strengths and limitations) of each of the methods as described by the authors of the empirical studies. We used PROGRESS‐Plus to categorize groups of people who might experience health inequity. The place of residence of high‐income country compared to low and middle income country was also considered as a factor across which health inequity may exist. We used the classification of the World Bank for high, middle and low income countries. Since the political climate of a country interacts with the income level of the country in relation to the existence of health inequities, we considered differences in political stability and climate in the "Plus" factor of PROGRESS‐Plus. For example, although Saudi Arabia is a high‐income country, the experience of health inequity by religious groups and women is different than in a Western industrialized country.

For the health inequalities to be judged inequitable, unfairness and avoidability (or remediability) need to be assessed. Therefore, we assessed whether the empirical studies of cohorts of systematic reviews included a judgment about the fairness and avoidability of health differences. If the studies made no judgment about health equity, we used the Whitehead criteria of avoidability and unfairness to make a judgment about whether health differences across these factors for the particular intervention and setting could be considered health inequities (Whitehead 1992). Judgments made using these criteria were documented, including whether sufficient information was available to make such a decision. For example, sex differences that are due to unavoidable underlying differences in biology would not meet the criteria for a health inequity, such as differences in rates of breast cancer across sex, or manifestations of haemophilia in males (Whitehead 1992). We expected substantial heterogeneity in definitions of equity. Therefore, we documented the variety of existing definitions to help inform the development of universally accepted definitions.

Empirical studies of cohorts of systematic reviews were included if they focused on the following:

Targeted approaches: evaluating effects (benefits or harms) in disadvantaged populations only (i.e. populations who suffer from health inequity due to their characteristics across one or more of PROGRESS‐Plus factors).

Gap approaches: evaluating differences in effects (benefits or harms) between the most and least advantaged groups (see Table 1).

Gradient approaches: evaluating effects (benefits or harms) on the gradient from the most disadvantaged to the least disadvantaged groups (Table 1).

Types of methods

We compared different methods used by the empirical studies for assessing effects on health inequalities in terms of: the expertise required to implement the strategy at the level of the overview/empirical study; the availability of data from the systematic reviews as assessed by the authors of the empirical study; their advantages and disadvantages; and whether and how judgments about health equity are made (e.g. judgments about fairness and avoidability of differences in benefits or harms).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Advantages and disadvantages of the methods used for assessing health inequalities, based on descriptions of the authors of the empirical studies and a judgment by the data extractors assessed from the perspective of a user of the empirical study. This judgment was made by asking the data extractors to consider a decision‐maker's perspective. These judgments were compared and agreed to. We also discussed these judgments with other authors who were not responsible for the data extraction.

Whether the analyses of effects on health inequalities across PROGRESS‐Plus factors met the following criteria for credible subgroup analyses, as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook (Oxman 1992, Cochrane Handbook 2009).

Clinically important difference.

Statistically significant difference.

A priori hypothesis.

Subgroup analysis is one of a small number of hypotheses tested.

Difference suggested by comparisons within primary studies of meta‐analyses.

Difference consistent across primary studies of meta‐analyses.

Indirect evidence that supports hypothesized difference.

Four additional criteria have been proposed since this protocol was written for assessing the credibility of subgroup analyses: 1) consideration of baseline characteristics; 2) independence of the subgroup effect (i.e. the subgroup effect is not confounded by association with another factor); 3) a priori specification of the direction of effect; and 4) consistency across related outcomes (Sun 2010). These four criteria have not been assessed. They will be included in the first update of this review.

Secondary outcomes

Whether and how health inequity was defined and measured (e.g. whether proxy measures, such as nutritional status, are used).

Information on the availability of data from primary trials or meta‐analyses to conduct analyses across PROGRESS‐Plus factors.

What factors are associated with health inequalities (e.g. the types of primary studies included in the systematic reviews and implementation factors, such as the degree to which flexibility was allowed in the implementation).

Implications for practice, policy, and research based on analysis of effects on health inequalities.

Search methods for identification of studies

The search strategy was developed by one author (VW) using a systematic scoping exercise to assess the effects of different MeSH terms and the use of limits on publication type (i.e. limited to meta‐analyses or systematic reviews) and type of studies (i.e. intervention studies). The terms developed for equity were based on the elements of PROGRESS‐Plus, and testing that our group has done on the use of filters for health equity (McGowan 2003). We tested the inclusion of a term related to geographic disparities (including terms such as resource‐poor settings and low and middle income countries) because the search was very broad without using restrictions. We tested this strategy to ensure that known relevant studies were retrieved, including one study of the assessment of low and middle income country concerns in systematic reviews (Nasser 2007). The final search strategy does not include limitations on publication type as these were found to be too restrictive. An information scientist (JM) reviewed the search strategy, as recommended by the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) guidelines (Sampson 2008).

The search strategy was not limited by publication type or study design as there is no indexing term for studies that assess cohorts of systematic reviews. We included published and unpublished articles, as well as abstracts.

Electronic searches

We searched:

the Cochrane Methodology Register (to July 2, 2010);

MEDLINE (January 1950 to July 2, 2010) using the Ovid interface;

EMBASE (1980 to July 2, 2010) using the OVID interface;

PsycINFO (1806 to July 2, 2010) using the OVID interface

CINAHL (1998 to July 2, 2010).

See Appendix 1 for the MEDLINE search strategy.This search strategy was adapted for the other electronic databases (Appendix 2).

To identify systematic reviews of social, legal, and educational interventions, we searched non‐health literature databases using the Scholars Portal interface including the Education Resources Information Center (ERIC, 1965 to July 2, 2010), Education Abstracts (1983 to July 2, 2010), Criminal Justice Abstracts (1968 to July 2, 2010), Index to Legal Periodicals (1994 to July 2, 2010), PAIS International (public affairs, public and social policies, international relations ‐ 1972 to July 2, 2010), Social Services Abstracts (1979 to July 2, 2010), Sociological Abstracts (1952 to July 2, 2010), and Digital Dissertations (1997 to July 2, 2010). We also searched the reports of national health technology assessment organizations using the Health Technology Assessment Database (available on the Cochrane Library) to July 2, 2010.

Searching other resources

We also handsearched abstracts from recent Cochrane and Campbell Collaboration Colloquia (2007 to 2010).

We used SCOPUS to identify citations of potentially included studies. SCOPUS is a citation tracking database of over 18,000 titles across scientific, technical, medical and social sciences fields as well as arts and humanities. We conducted a search of SCOPUS for all included studies on October 7 2010. This identified any articles which had cited one of the included studies.

We searched the reference lists of included studies for other potentially relevant studies, and we contacted the authors of included studies to ask if they knew of similar studies.

We also asked the editorial board members of the Cochrane and Campbell Equity Methods Group whether they were aware of other potentially relevant studies.

Unpublished studies and abstracts were identified through the methods above of contacting experts, authors and searching conference proceedings of the Cochrane and Campbell Colloquia.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (chosen from EU, JdM, MB, BD and VW) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all references retrieved by the search strategy to exclude those that were obviously irrelevant. They were not blinded to the authorship of the titles and abstracts because this is difficult to achieve and may not affect the screening process (Berlin 1997).

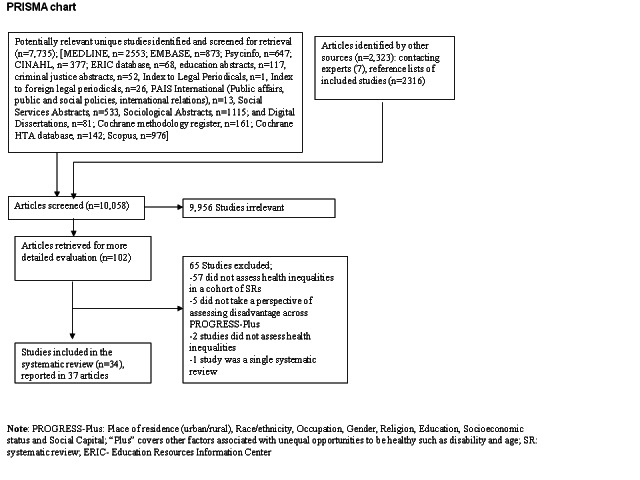

Potentially relevant articles were retrieved and screened independently by two review authors (chosen from EU, JdM, BD, MB, and VW) using an eligibility checklist. Disagreements were resolved by consensus in consultation with another author (MP or PT). We documented all reasons for exclusion at both stages of screening for entry into a PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta‐Analyses) flowchart (Moher 2009).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (chosen from EU, JdM, MB, and VW) extracted data independently from the included empirical studies using a pre‐tested data extraction form designed in an Excel spreadsheet (see Appendix 3), which was used to manage and summarize data. For consistency, VW extracted data from each study. The assignment of articles to the other data extractors was based on their time available to contribute. We compared the data extracted by both review authors for each study. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Another author (MP or PT) mediated when consensus could not be reached.

We extracted data on:

how the sample of systematic reviews was selected;

the characteristics of the systematic reviews (population, intervention, comparison, outcomes, study designs included, quality assessment, year of publication);

characteristics of the interventions being studied (e.g. pharmacologic, implementation, health services);

the method used to assess effects on health equity (how and whether equity is defined; which elements of PROGRESS‐Plus were compared; whether other factors, such as the study design of primary studies, setting, or context, were assessed that might explain differences in effects across PROGRESS‐Plus factors);

how effects were compared (e.g. relative or absolute differences, or gradient approaches such as the Gini coefficient);

the size of the difference in effects across different populations defined by PROGRESS‐Plus.

We also assessed whether data on PROGRESS‐Plus was available from the systematic reviews, as reported by the authors of the empirical studies.. We did not verify this data availability by consulting the systematic reviews.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two of the four possible reasons for systematic error or bias were addressed: selection bias and detection bias (Higgins 2008). For each of these possible sources of bias, we assessed the transparency of the methods described by the authors and the potential for bias in the methods used to select and analyze the systematic reviews included in the cohort. We did not assess performance bias as this is related to exposure to the intervention in randomized controlled trials and does not apply to empirical studies of cohorts of systematic reviews. In the context of empirical studies designed to assess health inequalities in cohorts of systematic reviews, selection and detection bias were defined as follows.

Selection bias: potential for bias in the selection of the systematic reviews to be included or excluded. We extracted details on the inclusion and exclusion criteria used to select systematic reviews.

Detection bias: potential for bias in the assessment of analytic methods and outcomes in cohorts of systematic reviews. We extracted information on how the details of the analysis of effects on health equity were extracted from the systematic reviews.

We did not assess attrition bias because in the context of this review, attrition bias (defined as systematic differences between groups in withdrawals) refers to the same concept as selection bias.

Measures of the effect of the methods

We conducted a comparative analysis of the methods used to assess effects on health inequalities by comparing the advantages and disadvantages of each of the methods, as judged by the data extractors, based on the description by the authors of the empirical studies and considering the perspective of the reader or user of the empirical study.

We extracted details reported by the authors of the empirical studies on the availability of data from the systematic reviews and their included primary studies, as well as on the methods used to compare differences in disadvantaged populations to the overall pooled effect.

We also compared any subgroup analyses against the seven criteria for credible subgroup analyses and four additional criteria (Oxman 1992, Sun 2010). Additional criteria for subgroup analyses for clinical trials and meta‐analyses were also considered for this comparison (Rothwell 2005; Thompson 2005).

Dealing with missing data

We planned to contact authors of the included studies if insufficient information was available regarding sample generation, methods, and outcomes. We only contacted one author for additional information, to request the criteria used to assess applicability and equity (Althabe 2008). These authors provided their checklists.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Results were not pooled. Results for each outcome (e.g. data availability, advantages, disadvantages, and credibility of subgroup analyses) were presented across each factor of PROGRESS‐Plus for each included study.

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting bias occurs when dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results (Higgins 2008). Positive studies, in the context of this review, include studies that are able to show statistically significant and substantive differences in effects across one or more PROGRESS‐Plus categories. We attempted to minimize the identification of only studies with positive results by using a comprehensive search strategy in diverse electronic databases, assessing relevant conference proceedings, reviewing citations, and contacting both the authors of eligible empirical studies and other experts.

Data synthesis

Results were synthesized in tables. Where data were available on subgroup analyses, we summarized the methods used to compare effects in different populations across PROGRESS‐Plus categories. For subgroup analyses, we assessed the first criteria of clinical importance of the difference in effects by assessing whether the authors of the empirical study described the clinical importance. If the authors did not judge the clinical importance, we compared the pooled effect size to the effect size reported in the different subgroups, either using mean differences or risk ratios and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

As this is a descriptive methodology review, the results were not pooled and subgroup analyses was not conducted.

Sensitivity analysis

As this is a descriptive methodology review, the results were not pooled and sensitivity analyses were not conducted.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

10,058 potential articles were screened for inclusion (Figure 1). Of these, 102 potentially eligible studies were retrieved in full text.

1.

Figure 2: PRISMA Chart

Included studies

Thirty‐four empirical studies (described in 37 articles) of cohorts of systematic reviews were included which assessed effects on health inequalities across one or more PROGRESS‐Plus factor. These included studies were identified by electronic databases (n=25), searching SCOPUS for references to included studies (n=5) (Barros 2010; Doull 2010; Bhutta 2008; Chopra 2008; Ball 2002), handsearching reference lists (n=2) (Shea 2009, Jones 2003) and contact with experts (n=2)(Bambra 2010; Odierna 2009). One ongoing doctoral thesis study assessing equity aspects in health technology assessment reports was identified (Panteli 2009). Four studies were identified as abstracts (Odierna 2009, Nasser 2007, Tsikata 2003, Doull 2010). Two studies remained unpublished except as abstracts, as of publication of this review (Nasser 2007, Tsikata 2003).

The methods used by these included studies were: 1) Targeted approaches (n=22); 2) gap approaches (n=12) and gradient approach (n=1). One study was classified as both a gap approach and a targeted approach (Sherr 2009), since it assessed differences in effects across sex (gap approach), as well as effects of interventions aimed only at women (targeted approach). Gender or sex was assessed in eight out of 34 studies, socioeconomic status in 10 studies, race/ethnicity in seven studies, age in seven studies, LMIC in 14 studies, and two studies assessed all PROGRESS‐Plus factors. The rationale for assessing effects on health inequalities in these studies was to better understand the mechanism of action of the intervention in five studies, to improve understanding of what works to reduce health inequalities in ten studies, to assess direct evidence on effectiveness in particular populations in nine studies, and to assess applicability or relevance of evidence for disadvantaged populations or settings in ten studies. The number of meta‐analyses or systematic reviews included in these studies ranged from 5 to 420 systematic reviews. Six out of 34 of these studies assessed cohorts of exclusively Cochrane reviews.

We included nine overviews of effectiveness of interventions to improve maternal, neonatal and child health with a focus on LMIC. These overviews are the studies from the Global report on preventing preterm birth and stillbirth (Barros 2010), the Lancet child survival series (Jones 2003), the Lancet series on Alma‐Ata rebirth and revision (Bhutta 2008), the Lancet neonatal survival series (Darmstadt 2005), the Lancet maternal and child undernutrition series (Bhutta 2008), and the Biomed Central series on reducing stillbirths (Bhutta 2009, Haws 2009, Menezes 2009, Yakoob 2009). These overviews of effectiveness were based on a combination of systematic reviews, randomized trials and observational studies, with particular emphasis on effectiveness and relevance in LMIC. The systematic reviews cited for these series drew heavily on Cochrane reviews since they were considered high quality and reliable systematic reviews by the authors of these series (for example, 81/102 systematic reviews cited in the 2009 Biomed Central reducing stillbirths series were Cochrane reviews).

Excluded studies

65 studies that were retrieved in full text were excluded. 57 studies were excluded since they clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria because they were not cohorts of systematic reviews (n=38) or because they did not assess health inequalities across one or more PROGRESS‐Plus factor (n=19). Eight studies which appeared to meet both of these inclusion criteria, but on closer examination failed, are described in the Table of Excluded Studies.

Five studies were excluded since they did not describe a focus on health equity (Gulmezoglu 1997; Barlow 2004; Espinosa‐Aguilar 2007; Craig 2003; Gaes 1999) (See Table of Excluded Studies). These studies assessed health effects of interventions in specific populations that could be classified as vulnerable across one or more PROGRESS‐Plus factor (e.g. sexual offenders, elderly, children with chronic disease), but the authors of the study did not describe a focus on vulnerability or disadvantage. Two studies of cohorts of systematic reviews were excluded since they did not assess health inequalities (Ahmad 2010, AHRQ 2010). One study that assessed health inequalities was excluded since it was a single systematic review of multiple interventions, not a cohort of systematic reviews (Thomas 2008).

Risk of bias in included studies

From the reporting of each cohort, we assessed the risk of selection bias to be low for 27 out of 34 included studies (Figure 2). These 27 empirical studies of a cohort of systematic reviews reported using an explicit search method, and screening titles for inclusion using prespecified criteria to identify relevant systematic reviews. Detection bias was low for 11 out of 34 of the included studies which reported explicit methods of data extraction, using forms and data verification. The other 23 studies did not fully report methods for data extraction and verification, and may be subject to a higher risk of bias due to missing relevant information.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Across studies, there is a low risk of selection bias since all of these empirical studies of cohorts of systematic reviews used a systematic search to identify studies that met predetermined criteria. Six out of 34 of these studies assessed solely cohorts of Cochrane systematic reviews which may be least likely to assess effects on health inequalities since they are most likely to assess efficacy questions where differences in effectiveness across PROGRESS‐Plus factors are least likely to occur (Tugwell 2008).

Effect of methods

Definition of health equity

Equity was defined in three studies, as unfair and avoidable inequalities in health across socioeconomic strata (Tugwell 2008; Tsikata 2003; Odierna 2009). None of the studies described making a judgment about the fairness of differences in health. Twelve studies describe higher burden of disease in disadvantaged populations as avoidable or preventable, without making a statement about fairness or justice. One study described using an “equity lens” (Main 2008) to assess whether systematic reviews could be used to answer questions about reducing health inequalities across SES, ethnicity or education. Three studies used the “SUPPORT equity checklist” (Lewin 2008; Althabe 2008; Chopra 2008) which assesses access to health care across LMIC, gender, age, ethnicity or SES (Appendix 4). Three studies focused on assessing differences across gender or sex by conducting a gender analysis (Johnson 2003, Sherr 2009) or gender and sex based analysis (Doull 2010). In one study, the rationale for conducting a gender analysis was due to differences in biological susceptibility HIV/AIDS as well as the social susceptibility through gender roles and discrimination (Sherr 2009). Nine studies focused on assessing relevance of systematic reviews for decisions about health care in low and middle income countries (LMIC)(Nasser 2007; Tugwell 2008; Tsikata 2003; Chopra 2008; Menezes 2009; Bhutta 2009; Haws 2009; Darmstadt 2009; Yakoob 2009). Two of these studies described differences in access to health care across geography and socioeconomic status in LMIC as inequitable (Lewin 2008; Chopra 2008).

Methods identified to assess consideration of effects on health inequalities or health inequities

We identified four categories of methods used to assess whether systematic reviews considered effects of interventions on health equity: 1) descriptive assessment of systematic reviews; 2) descriptive assessment of primary studies included in the systematic reviews; 3) analytic approaches and 4) judgment of applicability to disadvantaged populations or settings. See Table 2.

2. Methods used to assess whether health equity was considered in systematic reviews.

| Methods used to assess health equity effects | Which studies used this method | Data availability | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| 1a. Descriptive‐ SRs mention PROGRESS‐Plus | Doull 2010, Nasser 2007, Lewin 2008; Sherr 2009 | Gender/sex (15/44 SRs), LMIC (6/20 SRs) | Indicates whether authors of systematic reviews have considered health equity | Does not assess effects on health equity or health inequalities |

| 1b. Descriptive‐ SRs describe population across PROGRESS‐Plus factor(s) | Nasser 2007, Doull 2010, Tugwell 2008, Ogilvie 2004, Tsikata 2003, Lewin 2008; Sherr 2009; Yakoob 2009; Haws 2009; Darmstadt 2009; Bhutta 2009; Menezes 2009 | 2 studies did not report data availability (Nasser 2007; Ogilvie 2004); For the other 3 studies, PROGRESS‐Plus data was available for: Place of residence (5/95 SRs); race/ethnicity (7/95 SRs); occupation (1/95 SRs); gender/sex (90/153 SRs); religion (1/95 SRs); education (0/95 SRs); SES (4/95 SRs); social capital (0/95 SRs), LMIC (13/58 SRs reported >1 study in LMIC) | Provides direct data on whether different populations included in SRs which is useful for judging applicability | Does not analyze influence of population characteristics or setting on effects on health inequalities Data available for gender in 57% of SRs, others are available in less than 25% of SRs |

| 1c. Descriptive‐ SR describes if intervention is given only to disadvantaged populations across PROGRESS‐Plus | Nasser 2007, Ogilvie 2004, Tsikata 2003; Main 2008, Adamek 2008, Stewart 2006, D'Souza 2004, Ball 2002, Browne 2004; Tugwell 2008; Bartels 2003, Bhutta 2008, Shea 2009, Jones 2003, Darmstadt 2005, Vergidis 2009, Bhutta 2009, Darmstadt 2009, Haws 2009, Menezes 2009, Sherr 2009, Yakoob 2009 | Data not reported for 2 studies (Ogilvie 2004), (Nasser 2007); 17/114 SRs described interventions aimed at people defined by race/ethnicity, gender/sex, low SES or age (Tsikata 2003; Main 2008); seven methodology studies selected only SRs that focused on disadvantaged groups across PROGRESS; 100/217 SRs included studies conducted in LMICs. Three overviews described that some systematic reviews were conducted in LMIC, but did not report details for all SRs |

Assesses if interventions have been tested in specific disadvantaged populations | Does not assess effects of intervention Can be misleading since SRs with no studies conducted in disadvantaged populations may still be relevant and applicable |

| 1d. Descriptive‐ Outcomes of SR related to equity of access | Tsikata 2003, Nasser 2007, Althabe 2008, Lewin 2008, Bambra 2010, Chopra 2008, Jepson 2010 | Equity of access measured in 18/173 SRs. Data not reported by one study (Nasser 2007). One overview reported that no SRs had details about equity of access (Jepson 2010) | Provides data on access to health care, a determinant of health inequalities | Data on access to care does not measure effects on health inequalities Measuring access to health care is dependent on the question and availability of data depends on selection criteria of methodology review |

| 1e. Descriptive‐ describe if SRs conduct or plan subgroup analyses across PROGRESS‐Plus | Tugwell 2008; Ogilvie 2004; Johnson 2003; Tsikata 2003, Viswanathan 2008, Main 2008, Lewin 2008, Odierna 2009, Bambra 2010; Sherr 2009 | Analysis by PROGRESS‐Plus subgroup in 22/198 SRs; Place of residence; 0; Race/ethnicity (12/262); Occupation (0); Gender 19/204; Religion (0); Education (0); SES (1/198); 6/49 SRs assess differences across SES, gender or race. |

Subgroup analysis provides direct data needed to answer whether the intervention works the same or differently in populations of interest | Lack of data: data available by PROGRESS‐Plus subgroups of interest in 10% of SRs (28/247 had data) |

| 2a. Descriptive‐ assess if primary studies describe population across PROGRESS‐Plus | Tugwell 2008; Tsikata 2003, Johnson 2003, Ogilvie 2004 for 1 SR; Sherr 2009, Vergidis 2009, Bhutta 2009, Darmstadt 2009, Haws 2009, Menezes 2009, Yakoob 2009 | Place of residence (26/263), race/ethnicity (42/263), occupation (24/250), gender/sex (260/350), religion (0), education (42/263), SES (25/263), Social capital (24/250). 227/836 RCTs conducted in LMIC |

Provides evidence on whether sufficient evidence is available from primary studies to conduct subgroup analyses in SRs |

Data may not be available stratified by PROGRESS‐Plus factors in the primary studies |

| 2b. Descriptive‐ assess if primary studies stratified analyses by PROGRESS‐Plus | Tugwell 2008; Ogilvie 2004, Johnson 2003, Tsikata 2003; Sherr 2009, Jepson 2010 | 11 of 147 primary studies stratified by one or more PROGRESS‐Plus (Tugwell 2008); 96/366 assessed gender/sex (Johnson 2003; Sherr 2009); 10/76 and 5/14 stratified by sex (Ogilvie 2004); 7/103 stratified by education, sex or SES (Tsikata 2003). In Sherr 2009; SRs were classified according to whether there was positive, negative or no effect of gender [32/108 RCTs analyzed effects by gender (sic)] In Jepson 2010, 2/103 SRs were described as assessing "effect modifiers" such as sex, age, ethnicity and socioeconomic status |

Identifies whether subgroup analyses across PROGRESS‐Plus are available in primary studies and the direction and magnitude of effects in different populations | Time‐consuming to assess all primary studies of included SRs Does not rule out the possibility of spurious statistical significance |

| 3a. Analytic: association | Morrison 2004, Sherr 2009 | Age in 8/12 SRs; Sex in 7/12 SRs; SES in 5/12 SRs. In one overview, gender analysis was conducted and the effect of gender was assessed as positive, negative or no effect on results (Sherr 2009) |

Indicates whether PROGRESS‐Plus factors are associated with different relative effects Could be used to assess gradients of effect modification according to different levels of PROGRESS‐Plus (e.g. poverty) |

Data unavailable for 33% of SRs (4/12) |

| 3b. Analytic: relative comparison of effect size in two groups using an odds ratio | None | |||

| 3c. Analytic: assess effects in a disadvantaged population | Adamek 2008, Stewart 2006, D'Souza 2004, Ball 2002, Browne 2004; Bartels 2003, Vergidis 2009, Jepson 2010 | Identified median of 11 SRs with targeted evidence (range 5‐23); three studies reported medium to large effect sizes of interventions targeted at depression in older adults (Adamek 2008), youth with disabilities (D'Souza 2004) and mental health promotion in children (Browne 2004). One study reported effect sizes for specific populations: minority populations, men who have sex with men, injection drug users and people with HIV, and reported a synthesized effect size of 1.34 (95% confidence interval of 1.13 to 1.64) (Vergidis 2009). Three studies did not report effect sizes | Directly applicable for decisions about interventions in these specific disadvantaged populations Identifies evidence gaps |

Lack of data in some disadvantaged populations limits the use of this approach for other populations and settings Low methodological quality of SRs may limit applicability Lack of data on process of implementation |

| 4a. Applicability: assess likely impact on disadvantaged populations using checklists for applicability and equity | Althabe 2008, Lewin 2008, Chopra 2008, Barros 2010, Darmstadt 2005, Jones 2003, Bhutta 2009, Darmstadt 2009, Haws 2009, Menezes 2009, Yakoob 2009 | 8/20 SRs were considered most transferable to LMIC setting (Lewin 2008), 1 study only included SRs if they were deemed applicable in LMIC settings (Althabe 2008), 1 study assessed applicability to LMIC settings using the SUPPORT checklist. GRADE was used to assessed quality of evidence which includes an assessment of directness to the population of interest (LMIC in these studies) in three studies (Barros 2010, Bhutta 2008, Lewin 2008). Two studies used criteria of biological plausibility, impact and feasibility in LMIC (see Appendix 7) (Jones 2003, Darmstadt 2005) Five studies used the SIGN tools which assess directness, and also considered the feasibility and potential impact of these interventions in resource poor settings (Bhutta 2009, Darmstadt 2009, Haws 2009, Menezes 2009, Yakoob 2009) |

Useful summary for policy‐makers about likely relevance in LMIC settings Standardized format makes judgments explicit and transparent Does not require replication of studies in different populations and settings Not subject to statistical power issues of subgroup analyses |

Does not assess the magnitude of effect in different populations Requires content and methodological expertise to make equity and applicability judgments Low availability of data to make judgments (Althabe 2008), (Lewin 2008), (Chopra 2008) |

SES: Socioeconomic status; PROGRESS: PROGRESS: Place of residence (urban/rural), Race/ethnicity, Occupation, Gender, Religion, Education, Socioeconomic status and Social Capital

1) Descriptive assessment of systematic reviews

All 34 studies used at least one of the five descriptive approaches described below to assess whether their sample of SRs had considered effects of interventions on health equity.

1a) Mention of PROGRESS‐Plus in introduction, objectives, discussion, implications

Only three methodological studies included in their objectives the assessment of explicit mention of PROGRESS‐Plus in the introduction, objectives or discussion. This strategy provides information about whether SRs consider health equity in a broad sense, but provides no evidence on effects on health equity.

1b) Methods study assessed whether SRs describe populations in the primary studies across PROGRESS‐Plus factors

For the twelve empirical studies which used this method, details on the populations included in the trials were available for 0% to 57% of SRs across PROGRESS‐Plus factors. Sex distribution of the population was the most well‐reported PROGRESS‐Plus factor (90/153 SRs). The advantage of this approach is that information about the diversity of populations increases confidence in applying results across different populations and settings. The disadvantages are lack of data, and that description of populations does not assess differences in effects across these populations.

1c) Methods study assesses whether SR describes primary research as targeted at disadvantaged populations across PROGRESS‐Plus

Twenty‐two methodology studies assessed whether systematic reviews described interventions as being evaluated in specific disadvantaged populations. Of these, seven methodology studies selected SRs which focused only on disadvantaged populations (targeted). The disadvantaged populations targeted in these seven methodology studies were elderly with mental health problems (Adamek 2008; Bartels 2003), youth with disabilities (Stewart 2006), socially disadvantaged mothers (D'Souza 2004), people in low and middle income countries (Nasser 2007), women at risk for low birth weight children (Ball 2002), and minority populations, injection drug users and people with HIV (Vergidis 2009). These methodology studies described these populations as disadvantaged because of avoidable and unfair poorer health outcomes than other people due to lack of evidence, lack of guidelines or lack of resources to access and use preventive and curative interventions.

Ten methodology studies reported assessing whether the SRs described at least one study conducted in a disadvantaged population. While this descriptive method identifies whether interventions have been evaluated in disadvantaged populations, it does not assess the effects on health inequalities. Furthermore, it can be misleading since SRs with no studies in disadvantaged populations may still be relevant and applicable to disadvantaged populations.

1d) Methodology study assessed whether SRs have outcomes related to equity of access

Seven methodology studies described whether SRs reported outcomes related to access to care or coverage of health services. Access to health care across disadvantaged groups (e.g. rural, low SES, LMIC, ethnicity) was reported in 18/173 SRs in these methodology studies. Access to health care is a determinant of both health and health inequalities. This strategy does not measure effects on health equity. Evidence on access to care may be affected by the eligibility criteria of the methodology studies. For example, one methodology study required that SRs contain information about access to care in LMICs by the focus of the review (Lewin 2008).

1e) Methodology study assesses whether SRs planned or conducted subgroup analyses across one or more PROGRESS‐Plus factors

Ten methodology studies assessed whether subgroup analysis was conducted in groups of SRs. Outcomes were analyzed using subgroup analysis across one or more PROGRESS‐Plus factor in only 22 out of 262 SRs assessed in these methodology studies (8%). For those that reported details of these subgroup analyses, subgroup differences were assessed across gender/sex (n=15), race/ethnicity (n=12) and socioeconomic status (n=1). Differences in effects across other factors of PROGRESS‐Plus were not reported at the level of the SR in these methodology studies (LMIC, place of residence, occupation, religion, social capital). The advantage of this strategy is that subgroup analysis summarizes the data available in specific populations. However, these subgroup analyses are limited in their ability to detect differences due to statistical issues (e.g. post‐hoc analyses, probability of finding a false association, lack of data in the primary studies, or lack of reporting stratified data in primary studies) (Bambra 2010). Furthermore, subgroup analyses that were conducted were poorly reported (Table 3).

3. Subgroup analyses: assessment against credibility criteria.

| Johnson 2003 | Tsikata 2003 |

Ogilvie 2004 |

Odierna 2009 | Lewin 2008 | Tugwell 2008 | Viswanathan 2008 | Main 2008 | Bambra 2010 | Sherr 2009 | Jepson 2010 | |

| Clinically important difference | Not described | Not described | Not described | Not described | Yes, differences in effect that could affect health equity in 4/20 SRs | No SRs (0/14) conducted subgroup analyses | No SRs (0/64) conducted subgroup analysis across race | Can’t tell‐ 3/19 SRs assessed effects on health inequalities | Can’t tell‐ 8/30 SRs assessed effects on health inequalities | not described | Not described |

| Statistically significant difference | Not described, state “potential difference” in 3 out of 31 systematic reviews | Yes, in 1/95SRs | Not described | Yes, 5/16 SRs reported statistically significant difference in effects across gender or race | Not described | No data |

No data |

Not described | Not described | Not described | Not described |

| A priori hypothesis | Not described | Yes | Yes | Not described | Not described | No data |

No data |

yes | yes | Not described | Not described |

| One of a small number of hypotheses tested | Not described | Yes | Not described | Not described | Not described | No data |

No data |

Not described | Not described | y | Not described |

| Differences suggested by within study comparisons | Not described | Yes | Not described | Not described | Not described | No data |

No data |

Not described | Not described | Not described | Not described |

| Difference consistent across studies | Not described | NA‐ only 1 study | Not described | Not described | Not described | No data |

No data |

Not described | Not described | Not described | Not described |

| Indirect evidence to support hypothesis | Yes, evidence that cardiovascular risk factors, presentation, treatment and treatment outcomes vary between men and women | yes‐ economic rationale why transport incentives would work better for poorer people | Yes, smoking is associated with social disadvantage | Not described | Not described | No data |

No data |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Statistical subgroup by treatment interaction | Not described | Not described | Not described | Not described | Not described | No data |

No data |

Not described | Not described | Not described | Not described |

| Primary studies stratified randomization by subgroup of interest | Not described | Not described | Not described | Not described | Not described | No data |

No data |

Not described | Not described | Not described | Not described |

2) Descriptive assessment of primary studies included in the systematic reviews

2a) Methodology study assesses whether populations in primary studies are described according to PROGRESS‐Plus:

Eleven methodology studies retrieved and evaluated primary studies of included SRs to assess whether data was available from primary studies to conduct subgroup analyses in SRs. Population characteristics were reported in primary studies for sex most frequently (209/250 trials), followed by race, education, place of residence, socioeconomic status, occupation and social capital. This strategy has the advantage of assessing whether data is available in primary studies, thus assessing whether there is a risk of bias that PROGRESS‐Plus characteristics are under‐reported in systematic reviews (Bambra 2010; Tugwell 2008). However, this strategy does not assess effects on health inequalities, and data may not be available from the primary studies stratified by PROGRESS‐Plus characteristics.

2b) Methodology study assesses whether subgroup analyses conducted in primary studies:

Six of the methodology studies of systematic reviews assessed whether data was available from the primary studies on population characteristics across PROGRESS‐Plus and whether outcomes were analyzed using subgroup analysis in the primary studies (Tsikata 2003). In the included primary studies, outcomes were reported separately for sex most commonly (from 13‐36% of clinical trials), followed by SES (4 out of 103 trials in one study). Advantages of this approach are that more details are available regarding the methods of subgroup analyses by assessing information in the primary studies than in systematic reviews. Disadvantages of this approach are that it is time‐consuming to locate and assess all primary studies (Bambra 2010; Ogilvie 2004b).

3) Analytic approaches

3a) Methodology study to assess association of PROGRESS‐Plus factors with size of effect

Regression analysis was used by one methodology study of SRs on interventions to improve adherence (Morrison 2004). Data was available for age (8 out of 12 SRs), sex (7 out of 12 SRs) and socioeconomic status (5 out of 12 SRs). One study categorized the effect of gender on outcomes as positive effect, negative effect or no effect (Sherr 2009).

Advantages of assessing association of PROGRESS‐Plus factors with size of effect are that it could be used to assess which PROGRESS‐Plus factors are associated with effects on health equity and the dose‐response of their effect. The disadvantage of this approach is that data may be unavailable (e.g. in Morrison 2004, one third of SRs lacked data to conduct this analysis).

3b) Methodology study compares effect size using an odds ratio, relative risk or risk difference between two groups across PROGRESS‐Plus (e.g. men vs. women)

None of the 34 methodology studies reported a quantitative comparison of the difference between advantaged and disadvantaged populations or settings.

3c) Methodology studies assessed effects of interventions targeted at a specific population which is disadvantaged (e.g. older people with depression, youth with disabilities).

Seven methodology studies searched for systematic reviews of the effects of interventions targeted at populations which were described by the authors as disadvantaged by unequal opportunities for optimal health or high quality health care. One study (Vergidis 2009) assessed effects of interventions to reduce high‐risk behaviours in specific populations that are widely acknowledged as disadvantaged (i.e. minority populations, injection drug users, men who have sex with men and people with HIV), but did not make any judgment or statement about vulnerability of these populations. These methodological studies identified a median of 11 SRs (range 5‐23), and four studies reported clinically important and statistically significant effect sizes in these populations.

The advantage of this approach is that evidence on effectiveness can be directly used to inform decisions about interventions aimed at specific disadvantaged populations (e.g. older people with depression) (Adamek 2008) and to identify gaps in the evidence‐base. However, this approach may not be possible for some disadvantaged groups where systematic reviews or primary trials have not been conducted. Furthermore, this approach is limited by the methodological quality of the SRs and whether sufficient details about the process of implementation are reported to replicate the interventions. Also, the gap or gradient between these disadvantaged populations and others is not assessed, so the extent to which interventions generate health inequalities is not assessable (Adams 2005).

4) Judgment of applicability to disadvantaged populations or settings

4a) Methodology studies assess applicability to different populations across PROGRESS‐Plus

Eleven methodology studies assessed the applicability and relevance of systematic reviews to improve health of people in LMIC (Althabe 2008; Lewin 2008; Chopra 2008). Three methodology studies all used the SUPPORT Collaboration checklists for equity, applicability and scaling up to make judgments about whether the results from systematic reviews could be transferred to LMIC settings and could be expected to confer health benefits (details of SUPPORT checklists available in Appendix 4, and at: http://www.support‐collaboration.org/summaries/methods.htm).

Five studies used the SIGN tools to assess quality and strength of the evidence, including the directness of evidence to LMIC settings (see Appendix 5 and Appendix 6 for details about how applicability and generalizability are assessed using considered judgment).

Three studies used the GRADE tools to assess quality of evidence for each outcome. The GRADE assessment also includes an assessment of directness of evidence to the population of interest, which was people in LMIC in these studies (Lewin 2008, Bhutta 2008, Barros 2010). These three studies do not report how this judgment was made, or when the difference between people in the trials included in the systematic reviews would be large enough to downgrade the quality of evidence for indirectness.

Two studies used criteria of biological plausibility and feasibility of implementation in LMIC to select interventions. These criteria were judged by a panel of experts using Delphi consensus methods (Jones 2003, Darmstadt 2005). These authors do not report how these judgments were made, nor whether there was discrepancy in opinion in making these judgments.

Studies which assessed applicability described difficulty in making judgments about applicability of interventions in different settings than the settings where the primary studies were conducted (for example, Althabe 2008 describes difficulty in assessing applicability because the context and setting is different in Argentina than in other low and middle income countries). For judging the relevance and applicability to LMIC, there was limited evidence on real‐world effectiveness in LMIC, thus the authors relied on efficacy data from systematic reviews as well as expert opinion (Darmstadt 2005). For example, some interventions require access to highly skilled professionals, equipment or emergency transportation which may not be available in LMIC (Darmstadt 2009). For example, smoking cessation trials have almost all been conducted in high‐income countries, and their applicability to low and middle income country settings is questioned because risk factors may be different for women in low and middle income countries (Yakoob 2009).

Advantages of judging applicability to disadvantaged populations and/or settings are that it makes use of the best available evidence to make judgments that can be used to inform policies. Disadvantages are that the judgment of applicability and equity are extremely challenging and requires content expertise, knowledge of LMIC settings and methodological knowledge (Althabe 2008). Furthermore, assessing applicability does not assess the likely magnitude of effects and, since LMIC settings are extremely heterogeneous, the judgments required for these checklists need to be framed for specific settings.

Comparison against the “seven rules of when to believe a subgroup analysis”

For the eleven methodology studies which reported subgroup analyses in SRs across a PROGRESS‐Plus factor, we assessed whether these analyses met the Oxman and Guyatt seven credibility criteria of when to believe a subgroup analysis (Table 3) (Oxman 1992). We also assessed two additional criteria suggested by Rothwell that subgroup analyses should be tested with a subgroup by treatment interaction and that randomization of trials should be stratified across the intended subgroup analyses (Rothwell 2005). The eleven methodology studies provided insufficient data to assess seven out of nine criteria. Five studies provided a rationale to support the subgroup analyses, four studies described an a priori hypothesis, three studies reported statistical or clinically important differences, without details on the type of statistical test. None of these methodological studies described whether the differences assessed by subgroup analyses were due to differences in absolute effects (e.g. because of higher baseline risk in disadvantaged groups) or relative effects (e.g. because of different mechanisms of action).

Factors associated with differences in effects

None of the methodological studies described factors that might plausibly be associated with differences in effects across PROGRESS‐Plus.

Discussion

Systematic reviews represent an opportunity for increasing the ability to detect subgroup differences because they include studies conducted in diverse settings and populations(Glasziou 2002). These systematic reviews can increase the confidence in their subgroup analyses by reporting the rationale and methods in sufficient detail (Oxman 1992; Rothwell 2005). Measurement of effects on health inequalities is an active field of research, with over half of the included studies published in the last two years.

We identified four methods to assess effects on health equity in cohorts of systematic reviews: 1) describe populations in SRs; 2) describe populations in primary studies (e.g. randomized controlled trials or cohort studies); 3) analysis of different effects (benefit or harm); and 4) applicability assessment. However, the poor availability of data, both in primary studies and systematic reviews, for all of these approaches limits their usefulness.

The descriptive and analytic methods used in these methodology studies (described above) require data on outcomes stratified for specific populations across PROGRESS‐Plus to assess effects in these populations. However, a lack of population‐specific stratified outcome data does not mean that an intervention will not be effective in other populations (e.g. because primary studies have not been conducted in these populations or data has not been reported in the primary studies or the systematic reviews). For example, vaccination is expected to be effective in diverse populations, across a range of baseline risk and settings. For interventions tested in relatively advantaged populations, clinical epidemiology principles suggest that the relative risk reduction will remain the same across differences in baseline risk (Anderson 2005). Thus, the absolute risk reduction is expected to be larger for populations with a higher baseline risk. For example, therapeutic drug monitoring was shown to be effective at improving adherence to antiretrovirals in clinical trials conducted exclusively in high‐income countries. If the relative risk of 1.49 can be applied to low and middle income countries with higher HIV endemicity, a greater absolute effect may be achieved on population health (Kredo 2009).

None of these 34 empirical studies assessed what factors are associated with differences in effects on health equity. Identifying characteristics of interventions, population, comparison, setting, study design which are associated with effects on health equity could be used to inform a priori decisions to assess effects on health equity in systematic reviews and primary studies.

Descriptive and analytic approaches used by these methodology studies have the advantage of assessing whether an intervention has been tested in a specific disadvantaged population, which is appealing to practitioners and decision‐makers deciding whether to implement an intervention in a specific population and setting. Analytic approaches have the advantage of providing an estimate of the magnitude of effect in either advantaged or disadvantaged populations, or both. However, we found few systematic reviews which conducted subgroup analyses, and none of them described the analyses in sufficient detail to assess the credibility of the findings, since they failed to report details on the seven Oxman and Guyatt credibility criteria (Oxman 1992). Updated guidelines on subgroup analyses suggest also assessing four more items: 1) consideration of baseline characteristics; 2) independence of the subgroup effect (i.e. the subgroup effect is not confounded by association with another factor); 3) a priori specification of the direction of effect; and 4) consistency across related outcomes (Sun 2010). We did not assess these four additional factors.

None of the systematic reviews which reported effects on health inequalities described whether these different effects were due to differences in absolute or relative effects. Differences in absolute effects are expected in groups with a higher baseline risk of the outcome. For example, women from low and middle income countries have a higher rate of maternal mortality, and might achieve a larger benefit in absolute terms from interventions such as having a skilled attendant at the birth than women in high‐income countries with a very low maternal mortality. Differences in relative effects suggest that the mechanism of action of an intervention is different. For example, the relative effect of increases in tobacco price is greater in low income populations (Thomas 2008).

Judgment of applicability of evidence to disadvantaged populations and settings makes use of available evidence to inform decisions. Judging applicability or generalizability is used for making decisions about populations, interventions, comparisons, outcomes or settings beyond those studies in the systematic review and included trials. These methods have the potential to reduce needless replication of studies in different populations. Internationally recognized tools such as SIGN (SIGN 2008) and GRADE (Guyatt 2008, Guyatt 2008a) have the potential to increase the credibility of these judgments about directness of evidence to specific populations, if the judgments about directness are reported transparently. However, there is limited guidance provided by these tools on when evidence is sufficiently indirect to warrant downgrading quality. Applying these checklists is challenging and requires significant content, methodological and setting‐specific expertise to judge whether: 1) the observed differences is a true differences or random error; 2) are there differences in absolute effects due to different prevalence of the condition,or 3) are there differences in relative effects due to differences in how the intervention is delivered or received. For example, lack of follow‐up in settings with barriers to accessing regular care could lead to more serious adverse events if early signs of toxicity are missed. Applying these checklists is also challenging due to lack of data from settings of interest, and lack of data on the differences between settings in the primary studies and the setting to which the results will be applied. For example, the overviews of interventions to reduce stillbirths reported a lack of data from LMIC for most interventions, and raised questions about the differences in LMIC settings such as provider skill, availability of emergency transportation and access to clean delivery sites (Darmstadt 2009, Haws 2009, Yakoob 2009, Menezes 2009, Bhutta 2009). The reporting of how these judgments were made was inconsistent.

There is a lack of conceptual clarity regarding the definition of health equity. Only three out of 34 studies defined health equity explicitly. Use of the terms gender and sex in these studies conflicted with internationally accepted definitions, i.e. that sex refers to biological differences and gender refers to cultural and socially determined roles of males and females (Spitzer 2008).

Six out of 34 studies involved collaboration of the Cochrane Equity Methods Group. These studies analyzed cohorts of Cochrane reviews, which may be limited in their ability to detect subgroup differences since Cochrane reviews tend to contain fewer trials (median 8 studies) than other systematic reviews (Moher 2007). Furthermore, Cochrane reviews tend to assess efficacy questions where the effect size might be less likely to vary in different populations than for implementation questions which are more likely to be assessed by pragmatic trials (Thorpe 2009). None of the methodology studies assessed systematic reviews which focus on educational, legal and educational interventions; such as those from the Campbell Collaboration.

We identified six studies which assessed inequalities in health behaviours or determinants of health such as tobacco cessation and uptake of childhood vaccination (Jepson 2010, Bambra 2010, Main 2008, Ogilvie 2004, Shea 2009, Vergidis 2009). It is well known that inequalities in health behaviours do not fully explain inequalities in health status (Marmot 2008). Because the methodological challenges of assessing differences in health behaviours and health outcomes are similar, we included these studies in this review.

We used a rigorous and transparent process to identify and describe methods for assessing effects on health equity in systematic reviews, following up to date guidelines from the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook (Cochrane Handbook 2009). We used a structured approach to extracting and assessing factors across which health inequity may exist: the acronym PROGRESS‐Plus, accepted by the Campbell and Cochrane Equity methods group. We used a team of five people to extract data, and each study was assessed by at least two review authors. We used the PRISMA reporting guidelines to facilitate replicability (Moher 2009). There is a risk that we have missed some relevant studies since methodological studies of cohorts of systematic reviews are not well‐indexed and also since we decided to apply a geographic filter (Grobler 2008). We addressed this by using a comprehensive search strategy of both health and non‐health databases, that imposed no limits on study design based on pilot‐testing of the search strategy and review by a librarian scientist (JM) (Sampson 2008). We also searched reference lists and used SCOPUS to identify citations of included studies. Three out of 20 of the included studies were published as abstracts (Tsikata 2003; Nasser 2007) or reports (Ball 2002) and one included study was identified by contact with experts (Bambra 2010). Furthermore, one ongoing study and one excluded study were identified by contacting authors of included studies.

A limitation of this systematic review is that we did not include individual systematic reviews. We decided a priori that their inclusion could lead to bias since they may be less likely to report analyses of effects on health equity if none were found.

Another limitation of this review is that systematic reviews are dependent on the availability of data in primary studies. This systematic review did not assess whether data was available in primary studies nor the different biases which determine the representation and reporting of different populations and stratified analyses in primary research. Some of the authors of this review team are authors on empirical studies included in this review (PT, MP, EK, EU, VW, JM, GW). We sought to minimize the possible bias of analysis and synthesis of these studies by having those studies extracted by a review author who was not a co‐author (JdM or MB).

Authors' conclusions

Implication for methodological research.