Abstract

Background

Dementia is a major health concern and prevention and treatment strategies remain elusive. Lowering high blood pressure (BP) by repurposing specific anti-hypertensive medications (AHM) may reduce the burden of disease.

Methods

This is a meta-analysis of 6 prospective community-based studies (n= 31,090 well-phenotyped dementia-free adults older than 55 years) with median cohort follow-up of 7 to 22 years. We examined the association of incident dementia (n=3728) and clinical Alzheimer’s disease (AD; n=1741) to use of five AHM classes, within strata of baseline high (SBP≥140 mmHg or DBP≥90 mmHg; n=15537) and normal (SBP<140 mmHg and DBP<90 mmHg; n=15553) BP. We used a propensity score to control for confounding factors related to the probability of receiving AHM. Study-specific effect estimates were pooled using random-effects meta-analyses.

Results

In the high BP strata, compared to those not using AHM, those using any AHM, had a significantly reduced risk for developing dementia (hazard ratio [HR] 0.88, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.79 to 0.98) and AD (HR 0.84; 95% CI 0.73 to 0.97). There were no statistically significant comparisons of one drug class vs. all other drug class users. In the normal BP strata, there were no significant differences by use of any AHM, or by use of a specific AHM.

Interpretation

Over a long period of observation, there was no evidence that a specific AHM drug class was more effective than others in lowering risk of dementia. Among persons with hypertensive levels of BP, use of any AHM with efficacy to lower BP may effectively reduce the risk for dementia.

Funding

Funding for the Meta-Analysis was supported by The Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, “Targeting older adults for blood pressure interventions” grant number 20150703, and in part by the NIA Intramural Research Program.

Keywords: blood pressure, anti-hypertension medications, dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, cohort study, meta-analysis

Introduction

The benefits of blood pressure (BP) lowering treatment on prevention of cardiovascular disease and stroke have been firmly established.1 In contrast, debate continues about the important clinic and public health question of whether treating elevated BP, or taking a specific anti-hypertensive drug class (AHM), could reduce the risk of dementia.2

Observational studies suggest the association between high BP and late-life dementia is strongest when BP levels are measured in mid-life. There are mixed findings from observational studies about the benefit of lowering BP in late-life to reduce the risk of dementia.2 However, most recently, the SPRINT MIND trial targeting level of BP in high-risk persons 50 years and older has shown reducing blood pressure to <120 mmHg compared to <140 mmHg significantly reduced the risk for a combined Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) and dementia outcome.3

Based on experimental data suggesting several commonly used AHM drugs may have direct neuroprotective properties,4 the effect on dementia risk of specific AHM has been studied, with mixed results. Extant observational single cohort studies report different medication classes as the strongest candidate for prevention.5, 6 However, these studies differ in source populations, prevalence of confounding factors, study design and analytical methods, making results difficult to compare. Most of the clinical trials testing the efficacy of a specific drug on cognition-related brain outcomes have done this as a secondary or tertiary aim, so were generally not optimally designed to detect differences in the cognitive/dementia endpoints.2

Evidence from community-based cohorts with long follow-up of large numbers of well-phenotyped people using harmonized methods and analytical approaches can help address the limitations of previous research. We conducted a collaborative meta-analysis of six community-based cohorts of older persons to examine the associations of using any AHM to incident dementia and clinical Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and to investigate whether one AHM drug class was superior to others in reducing the risks for these outcomes. We also investigated whether the association of AHM to dementia risk differed by age and Apolipoprotein E allele.

Methods

Data are from the following six community-based cohorts previously described in detail elsewhere: Age Gene/Environment-Reykjavik (AGES-RS),79 Atherosclerosis Risk in the Community (ARIC),8 the Framingham Heart Study (FHS),9 Honolulu Asia Aging Study (HAAS),10 the Rotterdam Study (RS),11 and the 3-City Study.12 Criteria for including studies are detailed in the Search Strategy. Baseline data for these studies were collected between 1987 and 2008 in the United States, Iceland, the Netherlands, and France. All participating studies have previously worked collaboratively to address issues related to phenotype harmonization, covariate selection, and implementing standard analytic plans for within-study and pooled analyses.13,14 Informed consent was obtained from all study participants and all studies had local institutional review board approval over multiple exam cycles.

Anti-hypertensive medications

Drug exposures were assessed by medication containers presented to an interviewer at a clinical visit or during a home interview, or by audit of medical or pharmacy prescription records. Studies classified individual drugs according to the WHO Anatomical Therapy Classification (ATC) system (https://www.who.int/medicines/regulation/medicines-safety/toolkit_atc/en/), except for the HAAS study, where the drugs were classified by a study clinician according to mechanism of action. We examined the following five major AHM drug classes: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin II receptor antagonist (ARBs), beta blockers, calcium channel blockers (CCBs; including long- and short-acting preparations), and diuretics. Other individual drug classes not falling into these five drug categories (e.g., vasodilators, aldosterone blockers, alpha blockers and peripherally acting antiadrenergic) were rarely prescribed and not included in the estimates of anti-hypertensive drug effect.

Confounding factors

Confounding by indication occurs when people taking drug are different than those not on drug for reasons that are related to the outcome. As this is an important threat to the validity of pharmacoepidemiologic studies, we chose a priori baseline covariates associated with AHM prescription use and dementia risk, and therefore may contribute to confounding by indication. These included measured diastolic and systolic blood pressure; education; smoking status; depressive symptomatology; estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate; BMI; prevalent Type 2 diabetes; history of coronary disease, or stroke, or atrial fibrillation; and number of drugs used other than AHM. Details of coding are found in Supplemental materials. We did not include a variable for physical activity because the definition varied across studies. Since the APOE ε4 genotype is the strongest genetic risk factor for late-onset AD and could interact with BP level on the occurrence of dementia, we also included as a covariate ε4 allele presence vs. ε4 allele absence.15

Case ascertainment of dementia

Contributing studies identified dementia cases based on cognitive and functional measures derived from several sources including direct testing of participants, a clinical assessment and an informant interview. Across all studies, dementia was adjudicated by an expert-panel applying internationally accepted criteria given in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third, Fourth or Fifth Editions (https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596). Five cohorts applied National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) criteria to identify clinical AD cases.16 Three studies9,11,17 identified cases at in-person exams and by continuous monitoring and review of medical and mortality records; two cohorts assessed dementia at the 2 to 3 year interval exams; 10,12 one adjudicated dementia and estimated onset of dementia based on in-person exams, review of cognitive and health status data collected over the 25 years prior to the dementia baseline exam, and surveillance through administrative records.8

Study design

To investigate whether there were differences in specific medication effects, we a priori stratified participants based on baseline BP values. This stratification served several purposes: it allowed us to examine the association of AHM to dementia in a sub-group with normal BP, where the signal for a specific drug effect may be stronger. It allowed us to compare the effect of AHM to a group that did need AHM following evidence18 that the effect of treatment may only be present in people with the condition being treated. The stratification also allowed us to reduce the confounding that may be introduced by widely different BP levels. Previous studies on the relationship of anti-hypertensive medication to risk for dementia have compared AHM-users vs. -non-users. This approach makes it difficult to separate the effect on dementia risk of the medication from the effect of the level of BP: the importance of BP level is obscured because the AHM-user strata includes people with normal levels of BP, achieved through medication, as well as people with high BP levels. On the other hand, the non-HTM users also include persons with a range of BP from low to high.

Following the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure,19 participants were grouped into a high (SBP≥140 mmHg or DBP≥90 mmHg) or normal/pre-hypertension [hereafter globally labeled ‘normal’] BP (SBP<140 mmHg and DBP<90 mmHg), irrespective of anti-hypertensive medication,. Thus, the ‘normal’ group included both those with normal/pre-hypertension BP and no AHM use, and those who had normal/pre-hypertension BPs and used AHM. This latter group most likely includes people with well-controlled hypertension. Any further stratification by blood pressure, despite the total sample size, would result in very small sample sizes for the drug classes used less often.

Exposure to anti-hypertensive medication was defined as follows (example is given for ACEI): participants were classified as ‘ACEI users’ if they took ACEI medications in a single or combination preparation, with or without other anti-hypertensive drugs. Those taking ACEI as a monotherapy were classified as ‘ACEI only users’. ‘No use’ was defined as no baseline record of using any AHM. Three sets of analyses were performed by baseline BP strata: any AHM use vs. no use, to test the effect on incident outcomes of any AHM; one specific AHM class vs no use; and among AHM users, one class of drug vs all other classes to test whether there is any difference among drugs in their associations with dementia.

The analytical sample included all cohort members [ARIC included only the Caucasian participants] except those lacking data on BP measurements or AHM use; persons with prevalent dementia at baseline; age younger than 55 years at baseline; or those with a new onset of dementia before the age of 60 years, as these cases are likely to be more genetically determined, the numbers are low, and there are no studies suggesting an association between AHM intervention and a reduced risk for early onset cases. All studies applied a standardized definition of an incident cohort to include all persons at risk for dementia, meaning MCI cases were included in the cohort. Because MCI was defined differentially across cohorts, excluding them would create cohorts with different distributions of baseline cognition.

Statistical analyses

Control for confounding.

To account for confounding by indication and to avoid over-fitting of statistical models, a logistic regression model was used to calculate the propensity score for the conditional probability of using any AHM.20,21 The score included age, sex and all the aforementioned confounding variables, including baseline SBP and DBP. When data on a variable were missing [across all studies, 4% to 19% of participants had at least one variable with missing data], values were imputed using the fully conditional specification method that imputes on a variable-by-variable basis and does not assume normality and/or linearity of data.22

Analytical approach.

We followed a two-stage analytical approach. In the first stage, individual-participant level data analyses were conducted separately by a designated analyst at each study site, according to a common analytical plan. Specifically, at the individual study level, sample and variable definitions were harmonized, and BP strata-specific propensity scores were calculated. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals for the association of AHM use to risk of dementia and AD, were estimated with BP strata-specific Cox proportional hazards regression with age as the time-scale. Each participant was followed up from the date of AHM exposure assessment to the first record of dementia diagnosis, death, loss to follow-up, or the administrative censoring date. To ensure a balanced distribution of confounding variables in the AHM comparisons, within and across studies, propensity scores were categorized into deciles (except in the FHS, propensity scores were grouped into tertiles because some AHM cells had no dementia cases), and entered into the Cox models (model 1); the fully adjusted model 2 also included APOE ԑ4 carriership.

In the second stage, study BP strata-specific HRs were pooled at the Coordinating Center (NIA) and analyzed using inverse-variance-weighted random effects meta-analysis.23 Association tests were performed using the Wald χ2 statistic. The extent of heterogeneity across studies was evaluated using I2 statistic, which measures the proportion of variation in estimated HRs on the log scale that is attributable to between-studies variation as opposed to sampling variation.24

We conducted secondary and sensitivity analyses. We conducted pre-specified subgroup analyses by APOE ԑ4 carriership based on previous studies showing differential effects of a risk factor by carriership.15 We also stratified the analysis by baseline age (<75 years vs. ≥75 years), within BP strata, because at older ages, the effect of BP level on risk for dementia may be overwhelmed by other comorbidities. As a sensitivity analysis to account for the competing risk of death and interval censoring (i.e., death as a competing event and the probability of developing dementia between last dementia-free visit and death or last report of vital status), we used the semiparametric multi-state illness-death model.25 Briefly, the model incorporates the pathway of three transition states: from initial dementia-free (baseline) state to death, from initial dementia-free (baseline) state to dementia as an intermediate state, and from dementia state to death. By incorporating the three transition intensities, the HR for incident dementia in users of any AHM accounts for the associations with death in dementia-free and in demented individuals. More details on the statistical models are provided in the supplementary material.

SAS (version 9.3/9.4) was used to analyze study-specific data, STATA SE 12 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas) to compute the meta-analysis in the second stage, and the R package (SmoothHazard) to construct the illness-death model.

Role of the funding source

The funder of the meta-analysis had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the meta-analyzed data and the final responsibility to submit for publication.

Results

The six participating studies, predominantly white populations except for the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study (Japanese Americans) included participants with a mean cohort age ranging from 59 to 77 years. There were 31090 participants without prevalent dementia including 15553 participants in the normal BP strata and 15537 in the high BP strata. Across studies, the mean (SD) baseline SBP ranged from 123 (18) mmHg to 150 (22) mmHg and 72(10) mmHg to 82(11) mmHg for DBP. The proportion of participants on AHM varied from 33% to 62%, likely reflecting the large age range observed across studies. Of the AHM users, the proportion of participants taking multiple drugs (≥2) ranged from 28% to 58%; the use of beta blockers drug class alone or in combination with other drugs was most common (44%), followed by diuretics (40%), ACEIs (37%), CCBs (26%) and ARBs (11%) in mono- or combination regimens (Table 1).

Table 1:

Description of participants in 6 prospective cohort studies for meta-analysis of anti-hypertension medications and incident dementia

| Cohort Studies | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | AGES-Reykjavik | ARIC | FHS | HAAS | RS | 3C |

| Sample size, No. | 4163 | 5603 | 2379 | 2646 | 7240 | 8236 |

| Women (n,%) | 2467(59.3) | 2762 (49) | 1275(53.6) | 0 | 4166 (57.5) | 5052 (61.3) |

| Race/ethnicity (n,%) | ||||||

| White | 4163 | 5603 | 1961(99.7) | 0 | 7240 (99.7) | NA |

| Black | 0 | 0 | 6(0.3) | 0 | 25 (0.3) | NA |

| Japanese/Asian | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2646 | 0 | NA |

| Education (n,%) | ||||||

| Primary | 866(21.7) | 1283 (23) | 132(5.7) | 1330(50.2) | 849 (11.9) | 2046 (24.8) |

| Secondary | 2005(50.3) | 2437 (44) | 1445(62.6) | 769(29.1) | 3100 (43.3) | 2959 (35.9) |

| College | 649(16.3) | 1460 (26) | 731(31.7) | 278(10.5) | 2047 (28.6) | 1655 (20.1) |

| University | 469(11.8) | 419 (7) | N/A | 269(10.2) | 1165 (16.3) | 1576 (19.1) |

| Age mean (SD),y | 76.2(5.5) | 59.42 (2.90) | 65.8(7.1) | 76.9(4.1) | 68.9 (8.7) | 74.0 (5.4) |

| Age group, y (n,%) | ||||||

| 55–64 | NA | 5531 (99) | 1173(49.3) | NA | 2790 (38.5) | NA |

| 65–74 | 1780(42.8) | 72 (1) | 914(38.4) | 905(34.2) | 2565 (35.4) | 4724 (57.4) |

| 75–84 | 2076(49.9) | NA | 283(11.9) | 1572(59.4) | 1593 (22.0) | 3123 (37.9) |

| ≥85 | 307(7.4) | NA | 9(0.4) | 169(6.4) | 292 (4.0) | 389 (4.7) |

| Depressive symptoms (n,%) | 273(6.9) | 198(8.5) | 231(8.7) | 661(9.5) | 1077 (13.1) | |

| SBP mean (SD), mmHg | 142.2(20.4) | 122.63 (17.68) | 130.2(19.1) | 149.5(22.0) | 145.6 (21.8) | 146.5 (21.7) |

| DBP mean (SD), +C13:I25mmHg | 73.9 (9.6) | 71.49 (10.13) | 73.5(9.9) | 80.6(10.7) | 80.7 (11.1) | 82.3 (11.3) |

| BP group (n,%) | ||||||

| Normal BP | 2026 (48.7) | 4648 (83) | 1686(70.9) | 898 (33.9) | 2870 (39.6) | 3125 (37.9 |

| High BP | 2137 (51.3) | 955 (17) | 693(29.1) | 1748 (66.1) | 4370 (60.4) | 5111 (62.1) |

| Antihypertensive med use (n,%) | 2585(62.2) | 1821 (33) | 958(40.3) | 1092 (41.3) | 3061 (42.3) | 4138 (50.2) |

| ACEI w/wo others | 531 (12.8) | 212 (4) | 388(16.3) | 227 (8.6) | 2638 (20.1) | 1136 (13.8) |

| ARBs w/wo others | 504(14.5) | 0 (0) | 77(3.2) | 0 | NA | 987 (12.0) |

| BBs w/wo others | 1426(34.3) | 774 (14) | 411(17.3) | 306 (11.6) | 1638 (22.6) | 1387 (16.8) |

| CCBs w/wo others | 658(15.8) | 252 (4) | 292(12.3) | 498 (18.8) | 697 (9.6) | 1090 (13.2) |

| Diuretics w/wo others | 1554(37.3) | 1011 (18) | 349(14.7) | 368 (13.9) | 1036 (14.3) | 506 (6.1) |

| Use of ≥2 AHM | 1504(36.1) | 505 (9) | 469(19.7) | 364 (13.8) | 1353 (18.7) | 1502 (18.2) |

| ApoEε4 (n,%) | 1158(27.9) | 1491 (28) | 524(22.5) | 462 (17.6) | 1857 (27.4) | 1577 (19.1) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 27.1(4.3) | 27.08 (4.65) | 28.2(5.2) | 23.7(3.0) | 27.7 (4.2) | 25.7 (4.0) |

| Diabetes (n,%) | 487(11.7) | 651 (12) | 343(15.4) | 592(22.4) | 874 (12.1) | 638 (7.7) |

| eGFR, mean (SD) | 69.0(16.9) | 94.93 (12.36) | 79.5(15.8) | NA | 78.4 (14.6) | 117.2 (41.3) |

| Smoking (n,%) | ||||||

| Never | 1853(45.3) | 2171 (39) | 807(33.9) | 899(35.2) | 2117 (29.6) | 5070 (61.6) |

| Former | 1782(43.4) | 2158 (39) | 1312(55.2) | 1495(58.5) | 3762 (52.0) | 2721 (33.0) |

| Current | 456(11.2) | 1272 (23) | 260(10.9) | 161(6.3) | 1278 (17.7) | 445 (5.4) |

| Cardiovascular disease (n,%) | 854(20.7) | 428 (8) | 391(16.4) | 454(17.2) | 609 (8.4) | 518 (6.3) |

| Stroke (n,%) | 200(4.8) | NA | 57(2.4) | 84(3.2) | 226 (3.1) | 179 (2.2) |

| Atrial fibrillation (n,%) | 353(8.6) | 22 (0.4) | 114(4.8) | 73(2.8) | 382 (5.7) | 162 (2.0) |

| Year of baseline data collection | 2002–2006 | 1987–1989 | 1998–2001 | 1991–1994 | 2002–2008 | 1999–2001 |

| Year of last dementia follow-up | 2015 | 2013 | 2016 | 1999–2000 | 2015 | 2010 |

Median duration of follow-up across the studies ranged from 7 to 22 years, with half of the studies having more than ten years of follow-up. Overall, 3728 new-onset dementia, including 1741 clinical AD cases, occurred during 302,490 person-years of follow-up. The incidence rates of dementia and AD varied as a function of mean age in each study (Supplemental Table 1).

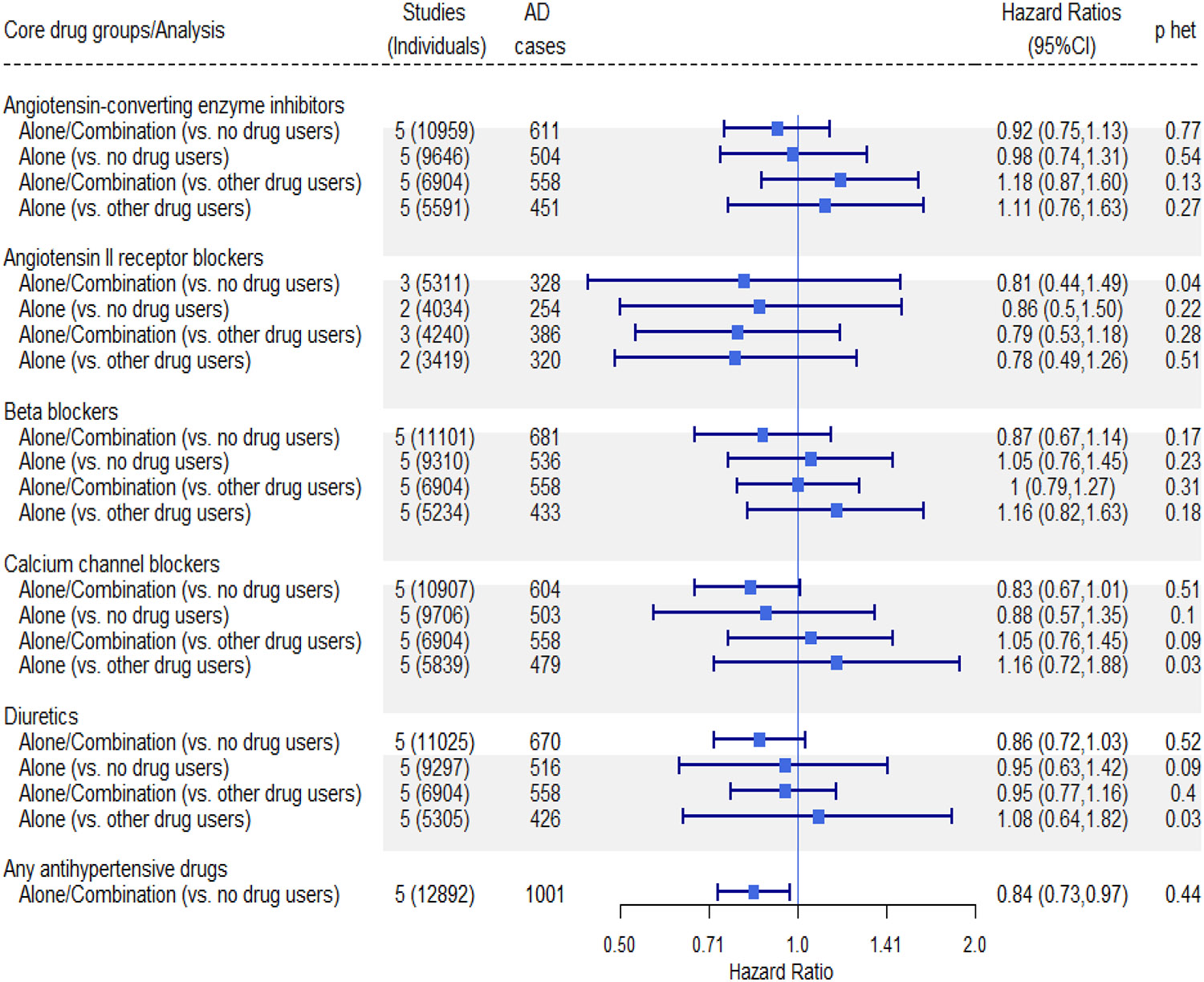

In the fully adjusted models in the high BP strata, compared to those not using any AHM, those using any AHM had a reduced risk for developing dementia (HR 0.88, 95%confidence interval [CI] 0.79–0.98, p=0.02; Figure 1 full model, Supplemental Figure 1 mode1) and AD (0.84, 95%CI 0.73–0.97, p=0.02; Figure 2 full model, Supplemental Figure 2 for model 1). For both dementia and AD, HRs were of variable effect size, with Beta Blockers and Diuretics showing a significant protective effect for dementia when compared to no drug use. No significant associations were observed in comparisons of each drug class vs. all other drug class users. There was no evidence for heterogeneity in the study-specific HRs for any anti-hypertensive drug use (dementia (Figure 1), χ2 =3.35, df=5, p=0.65, I2 =0.0% and AD (Figure 2), χ2 =3.73, df=4, p=0.44, I2 =0.0%).

Figure 1.

Forest plot and tabulated data for multiple reference groups of associations of antihypertensive medication use to incident dementia, High BP Strata, Model 2

P het: p value for heterogeneity

Figure 2.

Forest plot and tabulated data for multiple reference groups of associations of antihypertensive medication use to incident Alzheimer’s disease, High BP Strata, Model 2

P het: p value for heterogeneity

In the normal BP strata, risks for incident dementia (Figure 3, Supplemental Figure 3 for model 1) and for AD (Figure 4, Supplemental Figure 4 for model 1) were similar in those using any AHM compared to those not using AHM. There was no one drug class that differed in its association with the outcomes, with HR hovering around 1.0. Statistical tests suggested there was no significant heterogeneity of results across the studies, with exception of a few comparisons with very wide confidence intervals.

Figure 3.

Forest plot and tabulated data for multiple reference groups of associations of antihypertensive medication use to incident dementia, Normal BP Strata, Model 2

P het: p value for heterogeneity

Figure 4.

Forest plot and tabulated data for multiple reference groups of associations of antihypertensive medication use to incident Alzheimer’s disease, Normal BP Strata, Model 2

P het: p value for heterogeneity

Among those in the high BP strata, compared to no users, APOE- ԑ4 carriers who used any AHM had a significantly decreased risk of incident dementia (0.77, 95%CI 0.64 to 0.93, p=0.006; Supplemental Figure 5) and a non-significant but lower risk for AD (0.82, 95%CI 0.51 to 1.06; Supplemental Figure 6). This again reflected the similar associations with all five drug classes used alone or in combination when compared to no AHM users. For example, risks for incident dementia were as follows (Supplemental Figure 5): ACEIs (0.75, 95%CI 0.57–0.98), ARBs (0.68, 95%CI 0.40–1.14), BBs (0.74, 95%CI 0.53–1.02), CCBs (0.80, 95%CI 0.61–1.04) and diuretics (0.75, 95%CI 0.60–0.95). There were no differences in AHM associations among APOE- ԑ4 non-carriers in the high BP strata (Dementia, Supplemental figure 7 and AD, Supplementary Figure 8). Among those in the normal BP strata, there were generally no differences by APOE ԑ4 carrier status in AHM associations with dementia or AD [Supplementary Figures 9–12].

In participants in the high BP strata, the risk associated with any AHM use (Dementia, Supplementary Figures 13 and 14) and AD (Supplementary Figures 15 and 16) was lower in younger compared to older participants. For example, those younger than <75 years had an HR for dementia of 0.79 (95%CI 0.62–1.0) and those 75 years and older, had a HR of 0.91 (95%CI 0.77–1.06). In participants in the normal BP strata, the HRs for dementia (Supplementary Figures 17 and 18) and AD (Supplementary Figures 19 and 20) were generally similar in younger and older age groups, although the differences between younger and older participants were larger for AD (Supplemental Figures 19 and 20). The effect of any anti-hypertensive drug use on death was small and similar in dementia-free (1.07, 95%CI 1.00–1.16) and demented (0.98, 95%CI 0.87–1.10) participants. In the illness-death model, the HR for incident dementia in the high BP strata (0.91, 95%CI 0.81–1.02) was similar to the fully adjusted model of risk for anti-hypertensive drugs relative to no drug use (Supplementary Fig.21).

Discussion

Our results show that in the high BP (SBP≥140 mmHg or DBP≥90 mmHg) strata, compared to those who did not use AHM, those who did had a significantly 12% and 16% lower risk of dementia and AD respectively. These effects were similar across specific anti-hypertensive medication classes, when compared to non-users or to users of one vs other AHM. Of note, among those in the normal BP strata (SBP<140 mmHg and DBP<90 mmHg), whether taking AHM or not, there was no association of AHM use to incident dementia or AD. Further, no drug classes were differentially associated with the outcomes suggesting the importance of BP level in moderating the effect of AHM use on dementia risk.

SPRINT MIND3 found an effect on a cognitive outcome of lowering level of BP, but efficacy of individual drug classes was not examined. To date, results from previous published observational studies based on single cohorts show contradictory findings about which drug class is most highly associated with a lower occurrence of dementia5,6. Our pooled result of no single class of anti-hypertensive drug being superior for lowering dementia risk, reflects this inconsistency and addresses methodologic issues that may have confounded the comparisons.

Strengths and limitations of this meta-analysis

In this analysis we pooled large, well-phenotyped community-based cohorts across four countries; used harmonized individual participant-level data that was uniformly analyzed, enabling a consistent approach to adjustment for confounding by indication; and assessed and controlled for competing risk of mortality. Secondarily, our data provides suggestive evidence needing further confirmation, that AHM treatment may be more beneficial to younger participants or APOE e4 carriers.

We found similar effect sizes between the outcomes of total dementia and AD dementia. The distinction between sub-types of dementia due to a specific pathology is clinically challenging. Several community-based autopsy studies have shown a decedent has multiple lesions, with the combination of vascular plus other pathology being very frequent.26 In the population-based studies, having cardiovascular (sub) clinical disease does not preclude a diagnosis of AD, when clinical symptoms are typical of those described in AD diagnostic guidelines.

The merits of using observational cohorts to address our question should also be noted. We were able to study the effects of specific medications in a group of people who did not have elevated BP levels, which has not been investigated in previous clinical trials. Also, not possible in a trial, we had long-term follow-up data on the participants, which given the time it takes to develop clinical dementia, is essential to understanding prevention of the condition. Finally, the individuals in these cohorts have multiple co-morbidities and their characteristics better reflect the typical person seen in general medical practices.

However, despite the large sample, some cells were small or contained low number of cases, such as the ARBs users in the high BP strata, making it difficult to estimate reliable associations. In addition, we had little power to investigate specific drugs within a class, which may differ in properties such as those related to crossing the blood brain barrier. Further, we were not able to study the effect of change (i.e. lowering) in BP levels and risk for dementia. Indeed, our analyses suggest that even a relative decline within a hypertensive range of BP level, can benefit individuals with high BP. This issue requires further research.

Differential survival between users of AHM and non-users, may also affect our results. Although our sensitivity analysis suggested these groups did not differ substantially in risk for death, after accounting for confounding factors. However, accounting for the competitive risk for death attenuated the HR for incident dementia and AHM use in the high BP strata. It is also possible that within studies there was some misclassification of cases. This would likely occur in the ‘gray zone’ between MCI and mild dementia, where people could be classified as demented or as non-demented. Overall the lack of heterogeneity across studies in the effect estimates suggest this misclassification did not differentially affect any one cohort.

Finally, we cannot exclude residual confounding. Although we used as large number of detailed variables to construct the score predicting propensity to receive AHM, there may be unmeasured factors influencing exposure to AHMs and risk for dementia, such as adherence to BP treatment,27 physiologic differences in response to an AHM, or the extent to which the associations we report are related to lifestyle factors such as levels of physical activity. Together, the direction of the confounding is mixed: for some variables, such as physical activity, residual confounding could lead to an overestimate of effect, and others, such as non-adherence to medication protocol, could lead to an underestimation of effect.

Potential explanation of findings

There are many molecular, tissue, organ and system pathways affected by, and affecting BP,2,4,28 but the specific pathways related to the cerebral vasculature, neuronal health, and intracerebral connectivity remain to be elucidated.

We were not able to investigate other aspects of medication exposure, such as duration of hypertension and of exposure to a particular drug; time-varying changes in medication initiation or cessation such as changes in type, dosage or compliance; or the effects of a new disease event that could lead to a change in medication and behaviors.27 Research on these time-related events may best be investigated in electronic medical record-based studies that have more detailed records of treatment decisions and their consequences. Studies in more diverse samples, and periodic updates to this analysis to allow for changes in medical practice and drug formularies will be needed; for example, the use of ARBs was low in these cohorts. Optimally, a randomized trial for a head to head comparison of different drug classes is desirable, but at a minimum this would require a large sample of persons eligible to be randomized to any of the 5 drug classes, and a reasonably long follow-up to capture dementia events. In the absence of a trial, different scientific approaches, such as this meta-analysis, are needed to triangulate medication/pathway specific effects on the risk for dementia.

Taken together with data from the SPRINT MIND trial,3 these data suggest that anti-hypertensive treatment may be beneficial in reducing risk of dementia. However, given the current trends in demographic aging and the high percentage of untreated or poorly controlled treated hypertension30 optimizing BP management strategies to reduce dementia should be prioritized.

Supplementary Material

Search strategy and selection criteria.

For this pooled analysis of individual participant data, we searched PubMed for observational studies published in English between Jan 1,1980 and Jan 1, 2019 using common text words combined with text words and Medical Subject Headings for the terms: antihypertensive agents (e.g. antihypertensive agents[tw] or antihypertensive agents[tiab] or antihypertensive drug*[tiab] or antihypertensive medication*[tiab]), calcium channel blockers, diuretics, beta blockers, angiotensin II receptor antagonist, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, hypertension, blood pressure, dementia, alzheimer disease, cognitive dysfunction, cognitive decline and cognitive impairment, which were included in search string (Supplemental File 1). Review of reference lists and scientific meeting abstracts, and correspondence with experts was conducted to identify additional published and unpublished studies.

Cohorts were eligible for inclusion if they prospectively recruited participants from community-dwelling adults; included more than 2000 participants; collected data on dementia events over at least 5 years follow-up; had measured blood pressure and verified use of anti-hypertensive medications; and conducted in-person exams, supplemented with other data to capture events to detect dementia cases; and had followed cases for mortality.

Secondary inclusion criteria included a well described set of variables that may confound the association of anti-hypertensive medication use to dementia.

Research in Context,

As some anti-hypertensive medications may have direct effects on brain physiology, their repurposing may be an efficacious means to reduce the burden of dementing disease. Single cohort studies report different medication classes as the strongest candidate for prevention. However, these studies differ in source populations, prevalence of confounding factors, study design and analytical methods, making results difficult to compare. Most of the clinical trials testing the efficacy of a specific drug on cognition-related brain outcomes have done this as a secondary or tertiary aim, so were generally not optimally designed to detect differences in the cognitive/dementia endpoints. Most recently, the SPRINT MIND therapeutic strategy trial showed reducing blood pressure to <120 mmHg compared to <140 mmHg significantly reduced the risk for a combined MCI and dementia outcome, but the trial was not designed to look at specific medications.

Added value

To address this problematic interpretation of existing observational data we conducted a meta-analysis of individual-level data from six large community-based cohorts with long follow-ups of large numbers of well-phenotyped participants using harmonized methods and analytical approaches. Our meta-analyses also extend findings from trials, because follow-up is longer, tests of drug-specific efficacy could be examined in persons with normal blood pressure levels, and participants have multiple age-related conditions, similar to patients that are seen in general practice.

Implications

We found in older persons with high blood pressure using any anti-hypertensive medication, reduced the risk for developing dementia with no significant differences by use of a specific drug class. Risk for dementia in individuals with normal range BP was the same in those who used, compared to those who didn’t use anti-hypertensive medication. This suggests treating levels of high BP should be an immediately accessible primary strategy to reduce dementia and use of specific anti-hypertension medications should follow current guidelines.

Acknowledgements

3CS: The Three-City Study was performed as part of a collaboration between the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (Inserm), the Victor Segalen Bordeaux II University and Sanofi-Synthélabo. The Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale funded the preparation and initiation of the study. The 3C Study was also funded by the Caisse Nationale Maladie des Travailleurs Salariés, Direction Générale de la Santé, MGEN, Institut de la Longévité, Agence Française de Sécurité Sanitaire des Produits de Santé, the Aquitaine and Bourgogne Regional Councils, Fondation de France and the joint French Ministry of Research/INSERM ‘Cohortes et collections de données biologiques’ program. Lille Génopôle received an unconditional grant from Eisai.

AGES: Aging Gene-Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik Study: The research has been funded by NIA Contract N01-AG-12100 with contributions from NEI, NIDCD and NHLBI, the NIA Intramural Research Program, Hjartavernd (the Icelandic Heart Association) and the Althingi (the Icelandic Parliament).

ARIC: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Contracts (HHSN268201100005C, HHSN268201100006C, HHSN268201100007C, HHSN268201100008C, HHSN268201100009C, HHSN268201100010C, HHSN268201100011C and HHSN268201100012C), R01HL70825, R01HL087641, R01HL59367 and R01HL086694; National Human Genome Research Institute Contract U01HG004402; and National Institutes of Health Contract HHSN268200625226C. We thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions. Infrastructure was partly supported by Grant Number UL1RR025005, a component of the National Institutes of Health and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research.

FHS: The Framingham Heart Study (FHS) is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (contract no. N01-HC-25195 and no. HHSN268201500001I). Dementia, Brain MRI and Cognitive ascertainment were supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG0059421, R01 AG054076, R01 AG049607, R01 AG058589, R01 AG059421, U01 AG049505, U01 AG052409) and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NS017950 and UH2 NS100605). Dr. Pase was supported by a Future Leader Fellowship (ID: 102052) from the National Heart Foundation of Australia.

HAAS. The Honolulu Asia Aging Study is supported by NIH grants U01 AG046871 and R03 AG046614; the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging, ALZ Assn ZEN-12-239028; the Chia-Ling Chang Fund of the Hawaii Community Foundation; the Office of Research and Development, Department of Veterans Affairs Pacific Islands Health Care System; and the Nancy and Buster Alvord Endowment.

RS. The Rotterdam Study is funded by Erasmus Medical Center and Erasmus University, Rotterdam, Netherlands Organization for the Health Research and Development (ZonMw), the Research Institute for Diseases in the Elderly (RIDE), the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, the Ministry for Health, Welfare and Sports, the European Commission (DG XII), and the Municipality of Rotterdam. Further support was obtained from the Netherlands Consortium for Healthy Ageing and the Dutch Heart Foundation (2012T008) and the Dutch Cancer Society (NKI-20157737). The authors are grateful to the study participants, the staff from the Rotterdam Study and the participating general practitioners and pharmacists. Dr Ikram was supported by a ZonMW Veni Grant: 916.13.054.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

Authors have no conflicts to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brunstrom M, Carlberg B. Association of Blood Pressure Lowering With Mortality and Cardiovascular Disease Across Blood Pressure Levels: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2018; 178(1): 28–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iadecola C, Yaffe K, Biller J, et al. Impact of Hypertension on Cognitive Function: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Hypertension 2016; 68(6): e67–e94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.SPRINT MIND Investigators for the SPRINT Research Group, Williamson JD, Pajewski NM, et al. Effect of Intensive vs Standard Blood Pressure Control on Probable Dementia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2019; 321(6): 553–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hernandorena I, Duron E, Vidal JS, Hanon O. Treatment options and considerations for hypertensive patients to prevent dementia. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2017; 18(10): 989–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li NC, Lee A, Whitmer RA, et al. Use of angiotensin receptor blockers and risk of dementia in a predominantly male population: prospective cohort analysis. BMJ 2010; 340: b5465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khachaturian AS, Zandi PP, Lyketsos CG, et al. Antihypertensive medication use and incident Alzheimer disease: the Cache County Study. Arch Neurol 2006; 63(5): 686–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris TB, Launer LJ, Eiriksdottir G, et al. Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik Study: multidisciplinary applied phenomics. Am J Epidemiol 2007; 165(9): 1076–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gottesman RF, Albert MS, Alonso A, et al. Associations Between Midlife Vascular Risk Factors and 25-Year Incident Dementia in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Cohort. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(10):1246–1254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seshadri S, Wolf PA, Beiser A, et al. Lifetime risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. The impact of mortality on risk estimates in the Framingham Study. Neurology 1997; 49(6): 1498–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White L, Petrovitch H, Ross GW, et al. Prevalence of dementia in older Japanese-American men in Hawaii: The Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. JAMA 1996; 276(12): 955–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikram MA, Brusselle GGO, Murad SD, et al. The Rotterdam Study: 2018 update on objectives, design and main results. Eur J Epidemiol 2017; 32(9): 807–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Group CS. Vascular factors and risk of dementia: design of the Three-City Study and baseline characteristics of the study population. Neuroepidemiology 2003; 22(6): 316–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seshadri S, Fitzpatrick AL, Ikram MA, et al. Genome-wide analysis of genetic loci associated with Alzheimer disease. JAMA 2010; 303(18): 1832–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bis JC, Sitlani C, Irvin R, et al. Drug-Gene Interactions of Antihypertensive Medications and Risk of Incident Cardiovascular Disease: A Pharmacogenomics Study from the CHARGE Consortium. PLoS One 2015; 10(10): e0140496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rajan KB, Barnes LL, Wilson RS, Weuve J, McAninch EA, Evans DA. Blood pressure and risk of incident Alzheimer’s disease dementia by antihypertensive medications and APOE epsilon4 allele. Ann Neurol 2018; 83(5): 935–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 1984; 34(7): 939–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qiu C, Cotch MF, Sigurdsson S, et al. Cerebral microbleeds, retinopathy, and dementia: the AGES-Reykjavik Study. Neurology 2010; 75(24): 2221–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lonn EM1, Bosch J, López-Jaramillo P, et al. Blood-Pressure Lowering in Intermediate-Risk Persons without Cardiovascular Disease. N Engl J Med. 2016. May 26;374(21):2009–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003; 289(19): 2560–72.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qu Y, Lipkovich I. Propensity score estimation with missing values using a multiple imputation missingness pattern (MIMP) approach. Stat Med 2009; 28(9): 1402–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elze MC, Gregson J, Baber U, et al. Comparison of Propensity Score Methods and Covariate Adjustment: Evaluation in 4 Cardiovascular Studies. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(3): 345–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Buuren S Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Stat Methods Med Res 2007; 16(3): 219–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986; 7(3): 177–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002; 21(11): 1539–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leffondre K, Touraine C, Helmer C, Joly P. Interval-censored time-to-event and competing risk with death: is the illness-death model more accurate than the Cox model? Int J Epidemiol 2013; 42(4): 1177–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boyle PA, Yu L, Leurgans SE, et al. Attributable risk of Alzheimer’s dementia attributed to age-related neuropathologies. Ann Neurol 2019; 85(1): 114–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kyriacou DN, Lewis RJ. Confounding by Indication in Clinical Research. JAMA 2016; 316(17): 1818–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Warren HR, Evangelou E, Cabrera CP, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies novel blood pressure loci and offers biological insights into cardiovascular risk. Nat Genet 2017; 49(3): 403–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emdin CA, Rothwell PM, Salimi-Khorshidi G, et al. Blood Pressure and Risk of Vascular Dementia: Evidence From a Primary Care Registry and a Cohort Study of Transient Ischemic Attack and Stroke. Stroke 2016; 47(6): 1429–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoon SS, Gu Q, Nwankwo T, Wright JD, Hong Y, Burt V. Trends in blood pressure among adults with hypertension: United States, 2003 to 2012. Hypertension 2015; 65(1): 54–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.