Abstract

Reports of widespread thromboses and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) in patients with coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) have been rapidly increasing in number. Key features of this disorder include a lack of bleeding risk, only mildly low platelet counts, elevated plasma fibrinogen levels, and detection of both severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and complement components in regions of thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA). This disorder is not typical DIC. Rather, it might be more similar to complement-mediated TMA syndromes, which are well known to rheumatologists who care for patients with severe systemic lupus erythematosus or catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome. This perspective has critical implications for treatment. Anticoagulation and antiviral agents are standard treatments for DIC but are gravely insufficient for any of the TMA disorders that involve disorders of complement. Mediators of TMA syndromes overlap with those released in cytokine storm, suggesting close connections between ineffective immune responses to SARS-CoV-2, severe pneumonia and life-threatening microangiopathy.

Subject terms: Immunopathogenesis, Inflammation

A subset of patients with coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) develop a thrombotic disorder that resembles a virally induced, complement-mediated thrombotic microangiopathy. Here, the authors present the theory and evidence for this disease model and discuss important considerations for treatment.

Introduction

Infection of humans with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) forms a confusing picture of variable clinical features and degrees of severity across populations, ranging from mild influenza-like symptoms to life-threatening respiratory distress and multiple organ failure1–5. As this frightening pandemic has spread rapidly throughout the world, the sometimes contradictory reports of its manifestations should be understood in the context of the heterogeneous populations that have been infected, and the immense spectrum of genetic predispositions, coexisting risk factors and pre-existing medications that can hinder cohesive understanding. One picture is coming into better focus, however, which suggests that an immune-triggered, complement-mediated thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) is surprisingly common in patients with coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19). Like the better known TMA syndromes, this COVID-19-related syndrome is characterized by organ failure caused by widespread microclots in capillaries and other small vessels. In this Perspective article, we review the theory and evidence for a disease model of complement-mediated TMA and important implications for treatment.

Response to a new virus

The human immune system derives an extraordinary diversity from the process of reproduction, whereby random reassortment of countless genetic variables forms infinite numbers of unique host defence formulations. This heterogeneity is what protects us from the plethora of rapidly mutating microorganisms that relentlessly bombard us. When a new virus arises for which no immunological memory has developed, the complex and sophisticated process of adaptive immunity can take some time to mature. If, then, such a pathogen eludes early control by innate immune responses, a variety of ‘plan B’ immunological strategies could emerge and dominate6–11. These mechanisms might include what has been referred to as a ‘second wave’ of secreted IL-6 and other cytokines, with further activation of local immune cells6. Unfortunately, a broadened and lengthened immune response can become destructive to the host, triggering concomitant tissue damage and incitement of coagulation. The disturbance is exacerbated by persistence of the infecting agent or by the pathogen directly disrupting immune responses11–14, something that SARS-CoV-2 is already suspected to be capable of15. With the combined insults of immune dysregulation by a virus and overly prolonged but ineffective host immune resistance, widespread inflammation can develop, inducing symptoms more suggestive of autoreactivity than infection13–17. The net effect of each person’s singular mosaic of inherited immune variables upon encountering a novel virus might depend, at least in part, on unique features of the pathogen, its infecting dose or its tenacity9,18.

Poor outcomes following any infection are associated with older age, comorbid conditions or concomitant medications that have direct or indirect effects on immunity. These variables can put host defence checkpoints in disarray even prior to encountering a pathogen15. More rarely, sudden, cataclysmic responses can also occur in people who have no known risk factors for a poor outcome. In such cases, the peculiar properties of a certain virus might turn out to be harmful only to the minority of people who have inherited imbalances of specific, circumstantially relevant immune-modulating factors. This model is consistent with findings connecting Epstein–Barr virus exposure and its serological reactivation with onset and disease flares of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)13,14,16,17, establishing a precedent for rapid onset of autoimmunity at the time of exposure (or re-exposure) to a pathogen.

Disproportionate thrombotic risk

Common clinical features reported early in the COVID-19 pandemic included fever, upper respiratory tract symptoms, headache, fatigue, diarrhoea, shortness of breath and pneumonitis1–3,5,19,20, consistent with many other respiratory viral infections. Ground-glass opacities were often detected on chest CT in patients with early COVID-19, even when respiratory symptoms remained absent or moderate; it was observed that in patients with these opacities the disease might progress over a short time to a more obvious pneumonia4,20,21 with respiratory failure and features of classic acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Lymphopenia was widely reported1–3,22–24 at a greater frequency than observed for other viral infections25 and was associated with an adverse prognosis, defined in one study as admission to an intensive care unit (ICU), ventilation requirement or death2.

In a case series of 416 Chinese patients published in late March 2020, ~20% of the patients had evidence of ischaemic heart injury on the basis of elevated concentrations of cardiac enzymes, and this finding was coupled to more severe pulmonary disease and death26. The implications of this observation were initially unclear because older age and the presence of other comorbidities are associated with more severe COVID-19 (ref.27), consistent with risk factors for thrombosis in any ICU population28. In one review of 1,026 patients with a diagnosis of COVID-19 (ref.27), ~40% had a history of comorbid conditions consistent with a high likelihood of thrombosis. However, even compared with the expected rate of thrombosis in patients in ICUs28, reports began to emerge around the world confirming a disproportionate prevalence of abnormal coagulation tests and thrombotic events in patients with COVID-19, even in those who were not in ICUs5,29–31. The characteristic laboratory findings in these patients included elevated concentrations of D-dimer, high concentrations of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), fibrin degeneration products and fibrinogen, ubiquitously elevated concentrations of C-reactive protein and modestly low platelet counts. The predominant lung involvement in patients with COVID-19 had been recognized from the beginning of the pandemic to be accompanied by disorders of the liver, kidney and gastrointestinal system3,19,20,32. As case series began to be published from around the world, it became more clear that many of these organ impairments were thrombotic in nature. Furthermore, some of the patients who experienced severe thrombotic events were young people without known risk factors30.

Patients who had laboratory results consistent with thrombotic risk were more likely to be admitted to ICUs, to require mechanical ventilation and to die of complications, including venous thromboembolism. A study of 184 patients with COVID-19 in ICUs31 found a cumulative incidence of arterial or venous thrombosis over a 2-week period of 49%, with most thrombotic events (65 of 75; 87%) described as a pulmonary embolism, although their frequent location in segmental or other proximal (large) artery locations could suggest local immunothrombosis. These thrombotic events occurred despite the patients receiving standard-dose thromboprophylaxis. Comparing this study with previous studies of general patients in ICUs is difficult as the patient populations and treatments tend to vary. However, as a relatively comparable example, one study found that the incidence of thrombosis in patients in ICUs at high risk of deep vein thrombosis who were receiving thromboprophylaxis was 12%28. Additional evidence suggests that COVID-19-associated thrombosis is clinically important, as it has been directly associated with a higher risk of death (HR 5.4, 95% CI 2.4–12)31. In a different study, involving 191 patients with COVID-19 of differing severity, of whom 54 died, markedly elevated concentrations of D-dimer were observed in 81% of those who died as compared with 24% of survivors5. Concentrations of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I, serum ferritin, LDH and IL-6 were also higher in non-survivors than in survivors and were found to increase as disease worsened, consistent with an immune-mediated hypercoagulable state5.

In a retrospective study of 183 consecutive patients with confirmed COVID-19 in China29, non-survivors (11.5% of the patients) had, on admission to hospital, significantly higher concentrations of D‐dimer and fibrin degradation products, longer prothrombin time and longer activated partial thromboplastin time compared with survivors. These findings are consistent with classic disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) — and indeed 71% of non‐survivors but only 0.6% of survivors in the study met the criteria for DIC — but only if the focus is limited to these features and not to the relatively modest thrombocytopenia and inconsistently high fibrinogen levels reported29. In a different study, a decline in serum LDH concentration was associated with viral clearance in recovering patients with COVID-19 (ref.33). These findings, also supported by others32, demonstrate an untoward prevalence of markers for some kind of microangiopathy, which are associated with the persistence of virus and with poor outcomes, including death.

A subset of patients with COVID-19, including some young patients without obvious predisposition to thrombosis, seemed to develop severe gas exchange abnormalities when all or most of their lungs remained well-aerated21,34. This profile would, of course, be more suggestive of pulmonary vascular impairment than the classic severe ARDS that was thought to be responsible for most of the pulmonary failure.

Over a brief span of time, multiple formal and informal communications confirmed the frequency of abnormal coagulation markers and high rates of large-vessel and small-vessel thromboses in patients with COVID-19 (refs34–52). The pervasiveness of life-threatening thrombotic events was so striking to medical professionals that they began to report them via numerous news outlets34–38. Although thrombosis in young people with COVID-19 remained less common than in older patients, it was occurring far too often to be dismissed as an anomaly30,39. The term ‘silent hypoxia’ was applied to describe observations of markedly low oxygenation in the absence of any, let alone severe, lung involvement38. This state of low blood oxygen was associated with oedema in the interstitial and alveolar spaces of the lung, coupled with a ventilation–perfusion mismatch39. That is, oxygen enters the lungs but cannot diffuse across the pulmonary vascular bed in a clinical setting where multiple thromboses are being reported. This finding is not rare in patients with COVID-19, but it is otherwise consistent with a severe and widespread TMA.

There are numerous reports of high rates of coagulation abnormalities in patients with COVID-19, and it is widely considered that these abnormalities are DIC arising in the setting of SARS-CoV-2-induced sepsis29,32,33. This interpretation is based on the frequent finding of low platelet counts, widespread thrombosis, metabolic acidosis and significantly elevated concentrations of LDH and D-dimer5,19,29,32,33,45–51. However, observations of additional features that are more consistent with complement-mediated microangiopathy are also frequent in the literature, sometimes in papers that are discussing DIC. Unlike in patients with DIC, in patients with COVID-19, fibrinogen levels are often high and platelets are rarely more than slightly reduced. Despite a few reports of prolonged prothrombin or partial thromboplastin times29,52, these measures have been found to be markedly abnormal in other studies41,43,44, and clinically apparent bleeding episodes have not been observed. Furthermore, microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia has not been reported in patients with COVID-19. Elevations in concentrations of the complement-modulating acute phase reactant C-reactive protein (which can be seen in patients with DIC owing to its association with sepsis) seem to be ubiquitous in patients with COVID-19 and are associated with a poor prognosis3,24,51,53–55. Direct measurements of complement activity or complement components are only rarely reported in laboratory reviews of patients with COVID-19, but one commentary published in early April 2020 remarked on a verbal report by Chinese cardiologists of diffuse small-vessel occlusions in an autopsy review of patients with COVID-19 who did not survive and suggested, despite limited confirmatory data from other studies at the time, that the pattern of pathological findings was suggestive of a complement-mediated TMA56.

The concept of viral sepsis57 has been used to describe some patients presenting with symptoms resembling septic shock, with cold limbs and weak peripheral pulses but lacking hypotension. Given the assumption that viral sepsis is the cause of COVID-19-associated microangiopathy, as well as prior descriptions of DIC associated with other coronavirus infections58, DIC has continued to be prominent in the interpretation of the COVID-19-associated thrombotic diathesis29,40,41,45,46. However, the website of the American Society of Hematology has been updated several times, keeping abreast of emerging reports that there are elements of this microangiopathic syndrome that are not the same as DIC46.

As of late April 2020, both the American Society of Hematology and the American College of Cardiology recommended that all hospitalized patients with COVID-19 receive thromboprophylaxis unless they have a substantial risk of bleeding41,46 (a hallmark of DIC despite not being reported in COVID-19 populations). In theory, heparin could be useful in both thrombosis and sepsis, given its anti-inflammatory properties, including inhibitory interactions with multiple chemokines and complement59. A meta-analysis confirmed decreased mortality when low-molecular-weight heparin was used in patients with non-COVID-19 ARDS60. One study suggested that heparin might possess specific anti-viral properties by acting on the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, inducing a conformational change to prevent viral attachment61. Although the clinical relevance of this latter observation is unknown, the theoretical case for using heparin in patients with COVID-19 is strong.

Defining the thrombotic pathology

Whether multi-organ involvement is an ancillary condition in patients with COVID-19 who have multiple comorbidities or is caused by an autoreactive thrombotic disorder is a question that can be partially addressed by review of the published autopsy results that have become available. Both of these possibilities may be correct as anecdotal reports and the findings of small published series indicate a range from diffuse to minor microangiopathy or no evidence of it, despite multi-organ involvement56,62–64. Unsurprisingly, when microangiopathic changes were not seen in the organs examined, this finding was associated with evidence of comorbid conditions in those organs56,64. However, microangiopathic changes have also been seen in association with evidence of comorbidity or additional risk factors for thrombosis such as sepsis and ARDS64. One study found diffuse platelet microthrombi and megakaryocytes in multiple organs in a series of seven autopsies, suggesting frequent occurrence of a TMA syndrome, but concluded that a TMA syndrome was unlikely since kidney glomeruli were only involved in one of the autopsies63.

In a series of ten autopsies in Brazil65, diffuse exudative alveolar damage with only minor lymphocytic infiltration was seen in lung tissue. The frequency of small fibrinous microthrombi was high both in areas of damaged lung and in regions that appeared to be preserved. Fibrinous thrombi were rarely observed in the renal glomeruli and the vasculature of the skin. Another autopsy study from China66 included kidney samples from 26 patients with COVID-19 who had died of respiratory failure. Complex types of kidney damage were found, as would be expected in a population with concomitant diabetes mellitus, hypertension and superinfections. SARS-CoV-2 was identified in tubules and podocytes and was associated with extensive acute kidney injury. Neutrophil blockage of small vessels and endothelial damage was also observed. This autopsy series did not support a single conclusive model for pathology in the kidney, but microangiopathic vessel occlusions were nevertheless found. Hypoxia, proteinuria and multi-organ failure were also reported frequently in the histories of these patients66.

Magro et al.67 examined skin and lung tissues from five patients from the USA with COVID-19 associated with respiratory failure, three of whom had purpuric skin rash. The lungs were described as minimally inflammatory with fibrin deposits in the septal capillaries and neutrophil infiltration into inter-alveolar septa. There was diffuse alveolar damage with inflammation, and pneumocyte hyperplasia, but these features were not thought to be characteristic of typical ARDS. Additionally, deposits of terminal complement components C5b-9 (membrane attack complex), C4d and mannose-binding lectin-associated serine protease were identified in the microvasculature of the lung; these deposits were interpreted as demonstrating systemic activation of both the alternative and lectin-based complement pathways. Meanwhile, the purpuric skin lesions showed a minimally inflammatory thrombogenic vasculopathy, and deposition of C5b-9 and C4d was found in both affected and unaffected skin. In samples from two patients, COVID-19 spike glycoproteins were found, along with C4d and C5b-9, in the inter-alveolar septa and the cutaneous microvasculature. The authors concluded that this manifestation of tissue damage, found in all five of these patients, was consistent with a “catastrophic microvascular injury syndrome mediated by activation of complement pathways”67.

Widespread complement activation in post-mortem lung biopsies has also been reported in a non-peer-reviewed, pre-print publication from China62. In this study, staining with 20 antibodies detected multiple complement components in lung tissue from patients with COVID-19, and serum concentrations of C5a were increased in patients with COVID-19 while alive, with more prominent increases in those with severe disease.

In a comparison68 of post-mortem lung tissue from seven patients with COVID-19, seven patients who died from pneumonia during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic and ten non-infected donors, samples from patients with COVID-19 and samples from patients with H1N1 influenza had diffuse alveolar damage; however, in the samples from patients with COVID-19 capillary microthrombi were nine times as prevalent as in those from patients with H1N1 influenza. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors were identified on endothelial cells of these samples from patients with COVID-19, associated with viral invasion and endothelial damage.

In an autopsy series of ten African American patients from New Orleans, USA, with COVID-19, including some with evident ARDS, thrombosis of small lung vessels was identified in all ten patients with prominent evidence of microangiopathy64; on the basis of test results obtained while they were still living, this microangiopathy was not DIC as the patients did not have severe thrombocytopenia or prolonged coagulation times.

Taking into consideration these emerging autopsy reports from a diverse range of patients, it seems that TMA associated with COVID-19 is not rare. The small-vessel pathology of COVID-19 has several important differences from DIC that are prominent, both in these reports and in patterns of coagulation-related blood abnormalities, and suggest a condition closer to complement-mediated TMA syndromes, as was suggested even prior to some of the most recent evidence56. If COVID-19 is inducing a complement-mediated TMA that is more common and/or extensive than expected even in severe viral pulmonary conditions, this has critical implications for treatment.

TMA syndromes: a spectrum

Table 1 summarizes the similarities and differences between COVID-19-associated coagulopathy, DIC and other TMAs, including catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS), haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS), atypical HUS (aHUS) and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP)33,40–51,58,68–78. However, these differences are not absolute. Overlapping features among all of these syndromes are known to occur, and differentiating between these TMAs can be difficult at times.

Table 1.

Comparison of COVID-19 coagulopathy and other TMA syndromes

| Feature | COVID-19 | CAPS | HUSa | Atypical HUSb | TTP or autoimmune (SLE) TTP | DIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microthromboses | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Multi-organ involvement | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Complement activation | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Low platelet counts | Mild | Mild | Low | Low | Very Low | Very Low |

| Schistocytes | No | Rare | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Neurological involvement | Yes | Yes | Rare | Rare | More common | Yes |

| Renal involvement | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Rare |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Rare |

| Cardiac involvement | Yes | Yes | Rare | Rare | Yes | Rare |

| High LDH | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Prolonged coagulation time | Sometimes | Sometimesc | No | No | No | Yes |

| High concentrations of D-dimer | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lupus anticoagulant or aPL | Preliminary reportsd | Yes | Rare | Rare | Yes | Rare |

| Fibrinogen concentration | High | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Low |

| Bleeding | No | No | No | No | Rare | Yes |

| Association with known infection | Yes | Sometimes | Yes | Sometimes | Rare | Yes |

| Response to plasmapheresis or plasma exchange | Preliminary reportsd | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not used |

| Treatments | Anticoagulation, resolution of underlying cause if possible, targeted complement inhibition, steroids, other immune suppression, plasma exchange, IVIG | Anticoagulation plus resolution of the underlying cause | ||||

COVID-19-associated thrombosis and thrombotic manifestations include characteristics more similar to those for some of the complement-mediated TMAs than those for DIC33,40–52,58,68–78. aPL, antiphospholipid antibodies; CAPS, catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 19; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; HUS: haemolytic uraemic syndrome; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; TMA, thrombotic microangiopathy; TTP, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. aInduced by Shiga toxin. bInduced by genetic variants of complement components. cIn CAPS, prolonged coagulation time is an artefact of lupus anticoagulant, usually involving antibodies to prothrombin. dPreliminary reports of high incidence of aPL and responsiveness to plasma exchange in patients with COVID-19 remain to be confirmed.

DIC typically involves disorders at multiple levels of the coagulation and fibrinolytic systems, which lead to a consumptive coagulopathy that is characterized by both excessive thrombotic activity and low levels of fibrinolytic and anticoagulant factors59. Activation and consumption of platelets can lead to concomitant thrombosis and bleeding, which is not a major feature of other TMAs although it can be seen in TTP and SLE. Conversely, activated complement and platelet thrombi are central to the pathogenesis of most of the non-DIC TMAs68,71,73,77, suggesting that complement is an important integrative factor in these thrombotic diatheses. As reviewed here, COVID-19 pathology, like the non-DIC TMAs, seems to involve complement and platelet activation without the extent of platelet consumption observed in DIC.

Certain TMAs are worth discussing in the context of SARS-CoV-2 infection: CAPS71,72, which is sometimes preceded by infection; HUS74,75, which is incited by the bacteria-related Shiga toxin74,75; and aHUS, which involves inherited complement variants75. In patients with COVID-19, the complement pathology, the lack of reports of haemolytic anaemia or bleeding, and the rapidly progressive multi-organ decompensation with both large-vessel and small-vessel thromboses is strongly suggestive of a CAPS-like or aHUS-like disorder71,72,74,75. There are also preliminary reports that patients with COVID-19 exhibit the autoantibodies associated with CAPS, including lupus anticoagulant, anti-β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI) antibodies and anticardiolipin (aCL) or other antiphospholipid (aPL) antibodies52,79,80. However, in patients tested for lupus anticoagulant, background anticoagulation therapy was either not reported or was common52,79, although some of the test protocols included heparinase which would have decreased the rate of false-positive tests in patients taking heparin. The titres and isotypes of the aCL and anti-β2GPI antibodies were not known80, nor was the autoantibody status of the patients prior to COVID-19. aPL antibodies could be pathogenic or innocent bystanders in thrombophilic conditions, and in viral infections concentrations of aPL antibodies are frequently transiently elevated81. Moreover, lupus anticoagulant is common in patients admitted to ICUs82, as these antibodies can be associated with sepsis and/or catecholamine treatment. At present, the clinical relevance of these antibodies is unknown, and further research in this area might be valuable.

The finding of SARS-CoV-2 in specific regions where microangiopathy was observed67,68 suggests that this virus might be directly participating in the thrombotic diathesis, similar to the well-established pathology of Shiga toxin-mediated HUS74,75. Additionally, certain other TMA syndromes are sometimes associated with infections or infection-associated immune responses. Distinguishing the different TMA syndromes is often difficult as the differential diagnosis is based on whether they arise from genetic predisposition, infection or autoimmunity, which may be difficult to sort out, while the clinical and pathophysiological features overlap greatly. This enigma is illustrated by the recent identification of variants in complement regulatory genes (a hallmark of aHUS) that are associated with the autoimmune syndrome CAPS83. Distinguishing aHUS from SLE or aPL-related microangiopathic disorders is generally difficult because complement activation and overlapping pathologies are important features of all of these disorders70,71,83. This might be best considered a spectrum disorder rather than a list of independent diseases.

COVID-19 TMA pathogenic model

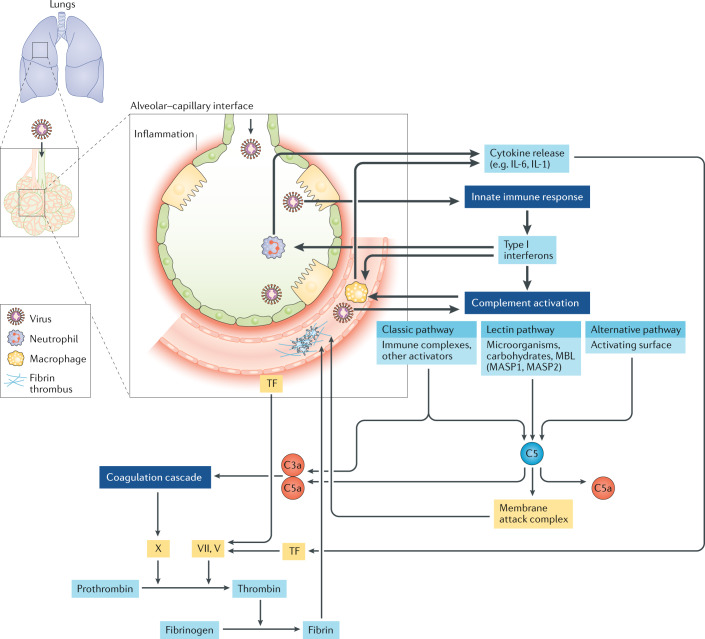

Figure 1 illustrates a suggested disease model that begins with damage to pneumocytes and the adjacent small-vessel endothelial cells of the lung by invasion of SARS-CoV-2 and ensuing innate immune activation, which leads to release of tissue factor6. This stage of disease could be similar to the inciting events in DIC58. However, SARS-CoV-2 could be instigating a much stronger inflammatory response than is typical in DIC, including induction of a wider variety of cytokines (such as IL-6), and with pro-coagulant effects and complement activation and/or deposition suggestive of the CAPS–HUS spectrum of TMAs. A virus can establish itself by impairing the host immune response through various mechanisms12, and this destabilization of immunity might help trigger or perpetuate a bidirectional immune–coagulation axis.

Fig. 1. A model of COVID-19 microangiopathy pathogenesis.

On the basis of emerging literature on the coagulation disorders and blood vessel pathology in patients with coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19)6,12,18,22–24,32,47,55–57,62–68,84,86,87, we hypothesize a unique thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) syndrome that is non-identical to other TMAs but shares key features with complement-mediated TMA conditions that involve infection-induced, organ transplant-related, autoimmune-mediated or inherited disorders of the complement system71,72,74,75. The SARS-CoV-2 virus probably enters alveolar pneumocytes through the respiratory tract and can also infect adjacent endothelial cells that supply the lungs and other organs that express angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, the receptor for this pathogen. As would be expected, this invasion triggers a rapid innate immune response by neutrophils and macrophages, activated in large part by type I interferons. If this process is inefficient, or if the adaptive immune response is delayed (owing in part to SARS-CoV-2 being a new infectious agent for which immunological memory has not been established), substantial damage might occur in capillaries or other small vessels surrounding the alveolar spaces, activating a pro-coagulant state. With further persistence of virus, complement-initiated damage to vessels intensifies, and inflammatory cells induce a wider and stronger burst of cytokines, including IL-6, which supports a bidirectional promotion of the immune–coagulation axis. This process might or might not develop into a viral sepsis with full-blown cytokine storm and pneumonia, but often does. A life-threatening coagulopathy is not rare in this COVID-19-associated thrombotic syndrome26,27,29–31,34, characterized by microthrombi in small vessels and/or rapidly progressive thromboses in both large and small vessels in multiple organs. MASP, mannan-binding lectin serine protease; MBL; mannose-binding lectin; TF, tissue factor.

Viral invasion into lung epithelial cells will attract monocytes and neutrophils at an early stage of SARS-CoV-2 infection, accompanied by activation of type I interferons as part of the innate immune response, which in turn contribute to a hypercoagulant state6. The ACE2 receptor is the major portal of entry of SARS-CoV-2 into cells and, in addition to being located on lung and endothelial cells, this receptor is known to be expressed in the liver, in kidney proximal tubules and throughout the gastrointestinal tract84. The fact that these organs are the same ones impaired by microthrombi during COVID-19 does not prove that SARS-CoV-2 directly induces organ damage or microangiopathy in every case of organ dysfunction. However, circumstantial evidence from a series of patients with COVID-19 located the virus in the small blood vessels that feed these same organs84. This coincidence could involve opportunity meeting a prepared dysfunctional organ that happens to contain the requisite ACE2 receptors, helping to trap the virus (or to be entrapped).

As monocytes also express ACE2 receptors, the virus could enter these cells by that route or via more generalized phagocytosis, potentially impairing macrophage function, as has been described for other coronaviruses12. T cells then arrive to interact with antigen-presenting cells, initiating the adaptive immune response85, although this process cannot be as efficient as it would have been if immunological memory had been established following previous exposure to SARS-CoV-2 or a sufficiently similar pathogen. Disordered T cell subsets or decreased T cell efficiency can lead to more severe disease, viral persistence and enhancement of the circular inflammation–thrombotic synergy. In the setting of a less-than-effective immune response, increasing inflammation contributes to a worse and more widespread coagulopathy within the blood vessels that are serving an infected organ.

Complement activation is a crucial part of the type I interferon-driven innate immune response to viruses and provides a common denominator between the pathogenesis of the COVID-19-associated microangiopathy, other TMA syndromes and the likelihood of progression to ARDS in patients with COVID-19 (refs86,87). Additionally, in a pre-publication summary available online62, it has been reported that the nucleocapsid protein on several related coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2, can bind directly to an important protease in the lectin complement pathway. If confirmed, this finding could explain complement activation in patients with or without a propensity for abnormal complement responses3,24,51,53–55,62,67, but remains to be confirmed.

The sequence, degree and rate by which an initial innate immune response proves ineffective and SARS-CoV-2 infection progresses along a continuum to microangiopathy, cytokine storm and/or ARDS differs from patient to patient6–11 and might depend on both the viral dose and the unique features of an individual’s immune response. This variance could explain why some patients can develop lung perfusion abnormalities in the absence of a ventilation defect whereas others progress directly to a more classic pneumonitis. Regardless of how these events play out in an individual patient, both the TMA of COVID-19 and other events that may occur early in an innate immune response, such as the activation of immune cells, IL-6 and IL-1, are immune factors that are also associated with ARDS in some patients with very severe disease6. All of these factors are likely to be contributing synergistically to the risk of macrothrombosis and microthrombosis in both early and late disease.

Implications for treatment

Owing to concerns about the effects of immune suppression in patients with ARS-CoV-2 infection and many comorbidities at high risk of severe disease, the use of potent, targeted immune modulators or globally immunosuppressive treatments have largely been considered only for patients with advanced disease88. However, given that the standard of care for patients with non-DIC TMA syndromes includes strategies to modulate the immune–coagulation axis (such as plasma exchange and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG)) and frank immunosuppressive strategies (for example, treatment with steroids, rituximab or complement inhibitors)69,71–74, earlier treatment with similar strategies might be appropriate in a subset of patients with COVID-19-associated TMA. In these patients, waiting for respiratory compromise or cytokine storm to develop might be too late.

Treatment options for COVID-19 are currently drawn from a confusing jumble of ongoing randomized trials superimposed on a much larger minefield of published anecdotes, small uncontrolled case series and studies with control groups that are historical, non-blinded or non-randomized. Although steroids were found to be ineffective in earlier studies, moderate-dose dexamethasone has been found to modestly lower the risk of death in patients receiving oxygen or mechanical ventilation and is now in wide favour in clinical pratice20,89,90.

The theories supporting the use of targeted immunomodulatory treatments are sound, but the evidence for this approach is weak and the pitfalls are unknown. For example, it is unclear if the IL-6 antagonist sarilumab, which failed in a recent trial91, is ever likely to have a substantial effect on a multifaceted cytokine storm or a TMA syndrome without the addition of other agents, despite the likelihood that IL-6 has a key role in both15. Selection of appropriate patients and choosing the best timing could also be important when considering immunosuppression. Whether giving biological agents early in the disease is too risky is unknown, although a small case series from New York suggests that the rate of hospitalization among patients with rheumatic disease and COVID-19 taking biological agents was not higher than has been reported in the general population92. Given the extreme urgency of a TMA, however, the better choice might be to start patients with features of TMA on the broad-spectrum strategies that are already known to work for TMA syndromes and that would, at least in theory, have a more comprehensive impact on cytokine storm than biological agents that target individual cytokines.

Evidence for using inflammation-related TMA syndromes as a model for treating any subset of patients with COVID-19 is scant. However, there is quite a lot of evidence that treating the SARS-CoV-2 coagulopathy as DIC is not sufficient. Anticoagulants are generally acknowledged to be helpful40–42,46,78 but the incidence of thrombosis and death remains high28,78. It has been suggested that in patients with severe disease and pre-existing deposits of fibrin in the lungs, inducing local fibrinolysis might be wise93. Two anecdotal reports suggest that tissue plasminogen activator seems to be clinically helpful as a treatment for COVID-19-associated ARDS34,94. Currently available antiviral treatments have also demonstrated modest efficacy. In an uncontrolled case series of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 who had hypoxia, clinical improvement was documented in 36 of 53 patients treated with remdesivir95. As reported in a press release, an NIAID trial of remdesivir met its primary efficacy end point, but the benefits were limited to the achievement of faster recovery time without affecting the rate of death96. Whether the modest efficacy of remdesivir is attributable to constraints on this agent as an anti-SARS-CoV-2 treatment, suboptimal timing or dosing or the possibility that established disease requires more than an antiviral approach is unknown.

A few reports of agents with some evidence base in complement-mediated TMAs have been published in the COVID-19 literature. Complement inhibition is currently in favour for the treatment of most of the non-DIC TMA syndromes following a number of uncontrolled case reports or patient series showing dramatic responses that would not have been obtained with anticoagulation alone97–100. These reports are consistent with results in another complement-mediated disorder, paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria101. Several preliminary anecdotal reports suggest good outcomes in patients with COVID-19 after use of the C5 inhibitor eculizumab, the C3 inhibitor AMY-101 or an anti-C5a antibody102–104, but these early observations must not be over-interpreted at this time. One interesting commentary, which made a persuasive case for a complement-mediated pathogenesis of COVID-19 based on evidence from murine models, suggested the therapeutic possibilities of combining complement inhibition with an anti-IL-6 approach87. The use of IVIG for the treatment of COVID-19 has also been reported anecdotally, and several patients have been reported to have recovered promptly after receiving IVIG during a stage of rapid deterioration105. Another patient with COVID-19 recovered after receiving plasma exchange followed by IVIG106. Plasma exchange is a safe and effective treatment for a compromised population and is standard of care in those with complement-mediated TMA syndromes69,107. A paper from China has provided anecdotal evidence of the beneficial effects of plasma exchange in patients with severe COVID-19 (ref.108). No conclusions can yet be drawn from these early, uncontrolled observations.

The purpose of plasma exchange is to remove thrombogenic and anti-fibrinolytic molecules and cytokines associated with a TMA condition. Replacing the removed volume of plasma with normal plasma might also replenish any deficiency of natural anticoagulant or pro-fibrinolytic molecules that are depleted in DIC-like consumptive coagulopathy. However, plasma exchange has not become standard practice for the treatment of DIC and seems to generally be considered unnecessary in that condition. In one study of patients with TMA, plasma exchange was associated with faster resolution of organ failure and improved survival compared with plasmapheresis69, suggesting that the replacement of plasma might be an important aspect of the treatment, unlike plasmapheresis, which simply removes pathogenic elements from a patient’s own plasma which is then put back into the patient. Plasma exchange can also specifically reduce IL-6 and IL-1β in patients with septic shock109–112. This could make it a feasible and safe supplement or even alternative to global immune suppression for a range of patients with COVID-19 and hypoxia due to microangiopathy and/or full blown ARDS. Furthermore, plasmapheresis membranes could activate complement and platelets, making it potentially less desirable as a vehicle for removing unwanted blood factors113. Plasma exchange might provide a particularly attractive vehicle for a multi-therapeutic approach by using plasma from convalescent patients with COVID-19 as the replacement source.

Conclusions

A substantial subset of patients with COVID-19 are dying with a severe TMA, arising in association with viral invasion of endothelial cells and triggering a robust innate immune response with widespread activation of immune cells, cytokines and complement activation. The range of clinical, laboratory and pathological findings reviewed here confirms a diffuse, small-vessel microangiopathy similar to complement-associated TMA syndromes. This COVID-19-associated TMA can be accompanied by full-blown viral sepsis, cytokine storm and/or advanced inflammation in the lungs, which would probably synergistically increase the risk of thrombosis. The COVID-19-associated thrombotic syndrome is a novel condition, which might be described as SARS-CoV-2-incited, complement-mediated TMA with or without cytokine storm. However, patients with this syndrome rarely receive interventions that are known to be effective for dangerous TMA conditions.

Of course, there is little direct evidence that treatments for TMA are effective for the COVID-19-associated thrombotic syndrome. However, any other patient with a complement-mediated TMA would be recognized as being in imminent peril, requiring prompt institution of multiple decisive interventions. These interventions would include anticoagulation and antiviral treatment (as would be used for DIC), as well as complement inhibition or more broad-spectrum immune suppression, plasma exchange and/or IVIG. Whether one or all of these approaches should be considered for all patients with COVID-19 and clinical laboratory evidence of TMA before severe hypoxia develops or progression to a cytokine storm is unknown; however, to ignore these options could be unwise.

An opinion piece published on 27 April 2020 in the New England Journal of Medicine114 appropriately cautions clinicians not to over-interpret newly acquired, anecdotal or uncontrolled data. However, most recommendations for the treatment of COVID-19 issued by medical associations are evolving and are based on the best evidence available at any given time, the limitations of which are fully acknowledged41,42,46. Just as feverishly embracing results of imperfectly conducted studies is ill-advised, attention must be paid to the burgeoning literature on this new virus, and all emerging information should be considered, albeit with a critical eye. Meanwhile, much of the treatment given today to hospitalized patients with COVID-19 is far more empirical than the suggestion to use standard of care for TMA for patients who show signs of this life-threatening condition.

Acknowledgements

The work of J.T.M. and J.J. is supported by NIH grants U54GM104938, P30AR073750 and UM1AI44292.

Author contributions

The authors contributed equally to all aspects of preparing the manuscript.

Competing interests

J.T.M. declares that she has received consulting fees from Alexion Pharmaceuticals. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Rheumatology thanks E. Gavriilaki, B. Hunt and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Guan W, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan L, et al. Lymphopenia predicts disease severity of COVID-19: a descriptive and predictive study. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020;5:33. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0148-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zheng R, et al. Clinical characteristics of 161 cases of corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Changsha. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020;24:3404–3410. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202003_20711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yin S, Huang M, Li D, Tang N. Difference of coagulation features between severe pneumonia induced by SARS-CoV2 and non-SARS-CoV2. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02105-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou F, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGonagle D, O’Donnell JS, Sharif K, Emery P, Bridgewood C. Immune mechanisms of pulmonary intravascular coagulopathy in COVID-19 pneumonia. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2:e437–e445. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30121-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chisari FV, Ferrari C. Hepatitis B virus immunopathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1995;13:29–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ascherio A, Munger KL. EBV and autoimmunity. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2015;390:365–385. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-22822-8_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin GL, McGinley JP, Drysdale SB, Pollard AJ. Epidemiology and immune pathogenesis of viral sepsis. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:2147. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ling GS, et al. C1q restrains autoimmunity and viral infection by regulating CD8+ T-cell metabolism. Science. 2018;360:558–563. doi: 10.1126/science.aao4555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Moorman JP, Yao ZQ, Jia ZS. Viral (hepatitis C virus, hepatitis B virus, HIV) persistence and immune homeostasis. Immunology. 2014;143:319–330. doi: 10.1111/imm.12349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Volk A, et al. Coronavirus endoribonuclease and deubiquitinating interferon antagonists differentially modulate the host response during replication in macrophages. J. Virol. 2020;94:e00178-20. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00178-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James JA, Robertson JM. Lupus and Epstein-Barr. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2012;24:383–388. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283535801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang I, et al. Defective control of latent Epstein-Barr virus infection in systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Immunol. 2004;172:1287–1294. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cao W, Li T. COVID-19: towards understanding of pathogenesis. Cell Res. 2020;30:367–369. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0327-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jog NR, et al. Association of Epstein-Barr virus serological reactivation with transitioning to systemic lupus erythematosus in at-risk individuals. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2019;78:1235–1241. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.James JA, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in adults is associated with previous Epstein-Barr virus exposure. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1122–1126. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200105)44:5<1122::AID-ANR193>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Channappanavar R, Perlman S. Evaluation of activation and inflammatory activity of myeloid cells during pathogenic human coronavirus infection. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020;2099:195–204. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-0211-9_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wan Y, et al. Enteric involvement in hospitalised patients with COVID-19 outside Wuhan. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020;5:534–535. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30118-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu L, et al. Clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus cases in tertiary hospitals in Hubei Province. Chin. Med. J. 2020;133:1025–1031. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berhnheim A, et al. Chest CT findings in coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19): relationship to duration of infection. Radiology. 2020;295:200463. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gattinoni L, et al. COVID-19 does not lead to a “typical” acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care Med. 2020;201:1299–1300. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0817LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu W, et al. Analysis of factors associated with disease outcomes in hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus disease. Chin. Med. J. 2020;133:1032–1038. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cao X. COVID-19: immunopathology and its implications for therapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020;20:269–270. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0308-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herbinger KH, et al. Lymphocytosis and lymphopenia induced by imported infectious diseases: a controlled cross-sectional study of 17,229 diseased German travelers returning from the tropics and subtropics. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2015;94:1385–1391. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi S, et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:802–810. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang T, et al. Attention should be paid to venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in the management of COVID-19. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7:e362–e363. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30109-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marik PE, Andrews L, Maini B. The incidence of deep venous thrombosis in ICU patients. Chest. 1997;111:661–664. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.3.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang N, Li D, Wan X, Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020;18:844–847. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oxley TJ, et al. Large-vessel stroke as a presenting feature of Covid-19 in the young. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:e60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klok FA, et al. Confirmation of the high cumulative incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19: an updated analysis. Thromb. Res. 2020;191:148–150. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang F, Hou H, Luo Y, Tang G, Wu S. The laboratory tests and host immunity of COVID-19 patients with different severity of illness. JCI Insight. 2020;23:137799. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.137799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yuan J, et al. The correlation between viral clearance and biochemical outcomes of 94 COVID-19 infected discharged patients. Inflamm. Res. 2020;69:599–606. doi: 10.1007/s00011-020-01342-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mount Sinai. Mount Sinai study COVID-19 may be driven by pulmonary thrombi and pulmonary endothelial dysfunction. https://www.mountsinai.org/about/newsroom/2020/mount-sinai-study-finds-covid19-may-be-driven-by-pulmonary-thrombi-and-pulmonary-endothelial-dysfunction-pr (2020).

- 35.Cha, A. E. A mysterious blood-clotting complication is killing coronavirus patients. Washington Posthttps://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2020/04/22/coronavirus-blood-clots/ (2020).

- 36.Fox, M. COVID-19 causing blood clots, sudden strokes in young adults, doctors say. CTV Newshttps://www.ctvnews.ca/health/coronavirus/covid-19-causing-blood-clots-sudden-strokes-in-young-adults-doctors-say-1.4910674 (2020).

- 37.Cha, A. E. Young and middle-aged people, barely sick with covid-19, are dying of strokes. Washington Posthttps://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2020/04/24/strokes-coronavirus-young-patients (2020).

- 38.Pappas, S. ‘Silent hypoxia’ may be killing COVID-19 patients. But there’s hope. Live Sciencehttps://www.livescience.com/silent-hypoxia-killing-covid-19-coronavirus-patients.html (2020).

- 39.Luks A, et al. COVID-19 lung injury is not high altitude pulmonary edema. High Alt. Med. Biol. 2020;21:192–193. doi: 10.1089/ham.2020.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lillicrap D. Disseminated intravascular coagulation in patients with 2019-nCoV pneumonia. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020;18:786–787. doi: 10.1111/jth.14781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.American College of Cardiology. Feature: Thrombosis and COVID-19: FAQs for current practice. https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2020/04/17/14/42/thrombosis-and-coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-faqs-for-current-practice (2020).

- 42.Song. JC, et al. Chinese expert consensus on diagnosis and treatment of coagulation dysfunction in COVID-19. Mil. Med. Res. 2020;7:19. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-00247-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao Y, et al. Diagnostic utility of clinical laboratory data determinations for patients with the severe COVID-19. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92:791–796. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yuki K, Fujiogi M, Koutsogiannaki S. COVID-19 pathophysiology: a review. Clin. Immunol. 2020;215:108427. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang N, et al. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020;18:1094–1099. doi: 10.1111/jth.14817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.American Society of Hematology. Covid-19 and coagulopathy: frequently asked questions. https://hematology.org/covid-19/covid-19-and-coagulopathy (2020).

- 47.Lippi G, Favaloro EJ. D-dimer is associated with severity of coronavirus disease 2019: a pooled analysis. Thromb. Haemost. 2020;120:876–878. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1709650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lippi G, Plebani M, Henry BM. Thrombocytopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: a meta-analysis. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2020;506:145–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bikdeli B, et al. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up: JACC state-of-the-art review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020;75:2950–2973. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Panigada M, et al. Hypercoagulability of COVID-19 patients in intensive care unit: a report of thromboelastography findings and other parameters of hemostasis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020;18:1738–1742. doi: 10.1111/jth.14850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fogarty H, et al. COVID-19 coagulopathy in Caucasian patients. Br. J. Haematol. 2020;189:1044–1049. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bowles L, et al. Lupus anticoagulant and abnormal coagulation tests in patients with Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383:288–290. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2013656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang L. C-reactive protein levels in the early stage of COVID-19. Med. Mal. Infect. 2020;50:332–334. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun Y, et al. Characteristics and prognostic factors of disease severity in patients with COVID-19: the Beijing experience. J. Autoimmun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tan C, et al. C-reactive protein correlates with computed tomographic findings and predicts severe COVID-19 early. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92:856–862. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Campbell CM, Kahwash R. Will complement inhibition be the new target in treating COVID-19 related systemic thrombosis? Circulation. 2020;141:1739–1741. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li H, et al. SARS-CoV-2 and viral sepsis: observations and hypotheses. Lancet. 2020;395:1517–1520. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30920-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mulloy B, Hogwood J, Gray E, Lever R, Page CP. Pharmacology of heparin and related drugs. Pharmacol. Rev. 2016;68:76–141. doi: 10.1124/pr.115.011247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wada H, et al. Differences and similarities between disseminated intravascular coagulation and thrombotic microangiopathy. Thrombosis J. 2018;16:14. doi: 10.1186/s12959-018-0168-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li J, Li Y, Yang B, Wang H, Li L. Low-molecular-weight heparin treatment for acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2018;11:414–422. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mycroft-West CJ, et al. The 2019 coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) surface protein (Spike) S1 receptor binding domain undergoes conformational change upon heparin binding. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.02.29.971093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gao T, et al. Highly pathogenic coronavirus N protein aggravates lung injury by MASP-2-mediated complement over-activation. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.29.20041962. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rapkiewicz AV, et al. Megakaryocytes and platelet-fibrin thrombi characterize multi-organ thrombosis at autopsy in COVID-19: a case series. EClinicalMedicine. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fox SE, et al. Pulmonary and cardiac pathology in African American patients with COVID-19: an autopsy series from New Orleans. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;8:681–686. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30243-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dolhnikoff M, et al. Pathological evidence of pulmonary thrombotic phenomena in severe COVID-19. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020;18:1517–1519. doi: 10.1111/jth.14844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Su H, et al. Renal histopathological analysis of 26 postmortem findings of patients with COVID-19 in China. Kidney Int. 2020;98:219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Magro C, et al. Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: a report of five cases. Transl Res. 2020;220:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2020.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ackermann M, et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383:120–128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rock GA, et al. Comparison of plasma exchange with plasma infusion in the treatment of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Canadian Apheresis Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991;325:393–397. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108083250604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chaturvedi S, Brodsky RA, McCrae KR. Complement in the pathophysiology of the antiphospholipid syndrome. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:449. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Erkan D, Salmon JE. The role of complement inhibition in thrombotic angiopathies and antiphospholipid syndrome. Turk. J. Haematol. 2016;33:1–7. doi: 10.4274/tjh.2015.0197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Asherson RA, et al. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: international consensus statement on classification criteria and treatment guidelines. Lupus. 2003;12:530–534. doi: 10.1191/0961203303lu394oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nesher G, Hanna VE, Moore TL, Hersh M, Osborn TG. Thrombotic microangiographic hemolytic anemia in systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;24:165–172. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(94)90072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Joseph A, Cointe A, Kurkjian PM, Rafat C, Hertig A. Shiga toxin-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome: a narrative review. Toxins. 2020;12:67. doi: 10.3390/toxins12020067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jokiranta TS. HUS and atypical HUS. Blood. 2017;129:2847–2856. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-11-709865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Emmi G, Silvestri E, Squatrito D, Ciucciarelli L. An approach to differential diagnosis of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome and related conditions. Sci. World J. 2014;2014:341342. doi: 10.1155/2014/341342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Manook M, et al. Innate networking: thrombotic microangiopathy, the activation of coagulation and complement in the sensitized kidney transplant recipient. Transplant. Rev. 2018;32:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Paranjpe I, et al. Association of treatment dose anticoagulation with in-hospital survival among hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020;76:122–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Harzallah I, Debliquis A, Drenou B. Lupus anticoagulant is frequent in patients with COVID-19. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jth.14867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang Y, et al. Coagulopathy and antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:e38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Uthman IW, Gharavi AE. Viral infections and antiphospholipid antibodies. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;31:256–263. doi: 10.1053/sarh.2002.28303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vassalo J, Spector N, Meis E, Soares M, Salluh J. Antiphospholipid antibodies in critically ill patients. Rev. Bras. Ter. Intensiva. 2014;26:176–182. doi: 10.5935/0103-507X.20140026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chaturvedi S, et al. Complement activity and complement regulatory gene mutations are associated with thrombosis in APS and CAPS. Blood. 2020;135:239–251. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019003863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Varga Z, et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395:1417–1418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ganji A, Farahani I, Khansarinejad B, Ghazavi A, Mosayebi G. Increased expression of CD8 marker on T-cells in COVID-19 patients. Blood Cell Mol. Dis. 2020;83:102437. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2020.102437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lupu F, Keshari RS, Lambris JD, Coggeshall KM. Crosstalk between the coagulation and complement systems in sepsis. Thromb. Res. 2014;133:S28–S31. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2014.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Risitano AM, et al. Complement as a target in COVID-19? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020;20:343–344. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0320-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kalil AC. Treating COVID-19–off-label drug use, compassionate use, and randomized clinical trials during pandemics. JAMA. 2020;323:1897–1898. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mehta P, et al. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395:1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Horby P, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19 — preliminary report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kolata, G. Arthritis drug did not help seriously ill Covid patients, early data shows. New York Timeshttps://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/27/health/coronavirus-drug-sarilumab.html?referringSource=articleShare (2020),

- 92.Haberman R, et al. Covid-19 in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases — case series from New York. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383:85–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Whyte CS, Morrow GB, Mitchell JL, Chowdary P, Mutch NJ. Fibrinolytic abnormalities in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and versatility of thrombolytic drugs to treat COVID-19. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020;18:1548–1555. doi: 10.1111/jth.14872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wang J, et al. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) treatment for COVID-19 associated acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): a case series. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020;18:1752–1755. doi: 10.1111/jth.14828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Grein J, Ohmagari N, Shin D, Diaz G. Compassionate use of remdesivir for patients with severe Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:2327–2336. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mcginley, L. & Rowland, C. Gilead’s remdesivir improves recovery time of coronavirus patients in NIH trial. Washington Posthttps://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/04/29/gilead-says-positive-results-coronavirus-drug-remdesivir-will-be-released-by-nih (2020).

- 97.Jodele S, Dandoy C, Lane A, Laskin BL. Complement blockade for TA-TMA: lessons learned from a large pediatric cohort treated with eculizumab. Blood. 2020;135:1049–1057. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019004218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Menne J, et al. Eculizumab prevents thrombotic microangiopathy in patients with atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome in a long-term observational study. Clin. Kidney J. 2019;12:196–205. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfy035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pape L, Hartmann H, Bange FC. Eculizumab in typical hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) with neurological involvement. Medicine. 2015;94:e1000. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Buillot M, et al. Eculizumab for catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome — a case report and literature review. Rheumatology. 2018;57:2055–2057. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gavriilake E, Brodsky RA. Complementopathies and precision medicine. J. Clin. Invest. 2020;130:2152–2163. doi: 10.1172/JCI136094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Numis DF, et al. Eculizumab treatment in patients with COVID-19: preliminary results from real life ASL Napoli 2 Nord experience. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020;24:4040–4047. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202004_20875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pitts, T. C. A preliminary update to the Soliris to stop immune mediated death in Covid-19 (SOLID-C19) compassionate use study. Hudson Medicalhttps://hudsonmedical.com/articles/soliris-stop-death-covid-19/ (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 104.Mastaglio S, et al. The first case of COVID-19 treated with the complement C3 inhibitor AMY-101. Clin. Immunol. 2020;215:108450. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cao W, Liu X, Bai T, Fan H, Hong K. High-dose intravenous immunoglobulin as a therapeutic option for deteriorating patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2020;7:ofaa102. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Shi H, et al. Successful treatment of plasma exchange followed by intravenous immunogloblin in a critically ill patient with 2019 novel coronavirus infection. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Darmon M, et al. Time course of organ dysfunction in thrombotic microangiopathy patients receiving either plasma perfusion or plasma exchange. Crit. Care Med. 2006;34:2127–2133. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000227659.14644.3E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yang XH, Sun RH, Zhao Y, Chen EZ. Expert recommendations on blood purification treatment protocol for patients with severe COVID-19: recommendation and consensus. Chronic Dis. Transl Med. 2020;6:106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.cdtm.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zhang Y, et al. A promising anti-cytokine-storm targeted therapy for COVID-19: the artificial-liver blood-purification system. Engineering. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.eng.2020.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hodgson A, et al. Plasma exchange as a source of protein C for acute onset protein C pathway failure. Br. J. Haematol. 2002;116:905–908. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1048.2002.03353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Burnouf T. Modern plasma fractionation. Transfus. Med. Rev. 2007;21:101–117. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Knaup H, Stahl K, Schmidt B, Idowu T. Early therapeutic plasma exchange in septic shock: a prospective open-label nonrandomized pilot study focusing on safety, hemodynamics, vascular barrier function, and biologic markers. Crit. Care. 2018;22:285. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-2220-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Vrielink H, Karssing W, de Korte D, Koopman R. Plasmapheresis and clotting activation. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2013;48:157. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zagury-Orly I, Schwartzstein RM. COVID-19 — a reminder to reason. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383:e12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2009405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]