Abstract

The spent fluid catalytic cracking (FCC) catalyst has been loaded with ferric oxide (Fe2O3) and titanium dioxide (TiO2). Fe-Ti/SF composite (loaded with 5 wt% TiO2 and 5 wt% Fe2O3), Fe/SF composite (loaded with10 wt% Fe2O3) and Ti/SF composite (loaded with 10 wt% TiO2) have been fabricated via a modified-impregnation method. The band gaps of the Fe-Ti/SF, Fe/SF and Ti/SF composites (evaluated by the energy versus [F(R∞)hv]n) are 2.23, 1.98 and 3.0 eV, respectively. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy shows that the Fe-Ti/SF has lower electron transfer resistance, it has the small charge transfer resistance and fast charge transfer rate. The interparticle electrons transfer between the Fe2O3 and TiO2, which can improve the separation of the photo-electrons and holes. The holes transfer from valence band of TiO2 to the valence band of Fe2O3, which can provide more active sites around the adsorbed molecules. The methylene blue degradation efficiencies (with the Fe-Ti/SF, Fe/SF and Ti/SF composites) are ~ 94.2%, ~ 22.3% and ~ 54.0% in 120 min, respectively. This work reveals that the spent FCC catalyst as supporter can be loaded with Fe2O3 and TiO2. This composite is highly suitable for degradation of methylene blue, which can provide a potential method to dispose the spent FCC catalyst in industry.

Subject terms: Materials chemistry, Photocatalysis

Introduction

In the oil refinery, the fluid catalytic cracking (FCC) is an important secondary conversion procrss1–4. The crude oil can be converted into the valuable small molecules products, which is an essential process for gasoline production5. In the FCC process, the catalytic activity of FCC catalyst decreases after several cycles. Metals (V, Ni, and Fe) accumulation occurs via deposition and incorporation into the FCC catalyst body6,7. There are about 840,000 t spent FCC catalyst consumed in the world every year and it is anticipated annual increase of 5%8,9. The spent FCC catalyst are mainly treated via landfill10. Some researcher explore the coating of spent FCC catalyst as anticorrosive and antimicrobial material, other researcher uses the spent FCC catalyst to recover the precious metal and rare earth, and use spent FCC catalyst as admixtures in mortar and concrete production11–13. Zeolite Y is the main components of the FCC catalyst14. When the FCC catalyst is deactivated, the pore volume of catalyst is almost intact, which still can be used as a carrier15.

Titanium dioxide (TiO2) has been extensively investigated for photocatalytic reaction due to its chemical stability and lack of toxicity16–19. TiO2 is a wide band gap semiconductor material (3.2 eV)20–23. In photocatalytic reaction, the charge carrier of the TiO2 is fast recombinated, which can be prevented effectively by the heterogeneous structures (with the narrow band gap semiconductor materials)24,25. Fe2O3 with narrow band gap (2.2 eV) tends to have short carrier diffusion lengths. Therefore, Fe2O3 extends the optical absorption edge to visible light region for TiO2. Eskandari et al. and Davari et al. synthesized TiO2/Fe2O3/zeolite composite, which displayed 89% and 80% photocatalytic degradation efficiency26–29.

In this work, spent FCC catalyst loaded with Fe2O3 and TiO2 was fabricated via a modified-impregnation method. The photocatalytic performance the Fe-Ti/SF, Fe/SF and Ti/SF samples are evaluated by the degradation efficiency of the methylene blue. The recycling experiments of the Fe-Ti/SF composite are implemented by the methylene blue degradation, which evaluates the stability of the Fe-Ti/SF composite. The advantage of this work is that it provides a new way to treat spent FCC catalyst. At present, the spent FCC catalyst are mainly treated by landfill. This method caused severe land pollution and polluted groundwater. The novelty of this work is the introduction spent FCC catalyst as supporter. These composites fabricated via this modified-impregnation method can provide an effective route to dispose the spent FCC catalyst in industry.

Materials and methods

Fabrication of the composites

In a typical experimental procedure, the spent FCC catalyst was loaded with titanium dioxide (5 wt% TiO2) and ferric oxide (5 wt% Fe2O3), it was prepared as follows. 0.85 mL tetrabutyl titanate and 0.31 g ammonium ferric oxalate were dissolved into 4 mL of H2O2 solution (~ 30%). Then 4 g spent FCC catalyst was added into this solution. Finally, this mixture was grinded for 2 h and calcined at 800 °C for 4 h. This sample is denoted as Fe-Ti/SF composite. The other two samples, i.e. Fe/SF composite, the spent FCC catalyst was loaded with ferric oxide (10 wt% Fe2O3) and Ti/SF composite, the FCC catalyst was loaded with titanium dioxide (10 wt% TiO2) were obtained in the above experimental procedure.

Characterizations

The structures of the fabricated composites were tested by power XRD (Rigaku RAD-3C, Cu Kα radiation, 10° min−1, 2-Theta range 5°–80°). These composites morphology was analyzed by a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM JEOL S-4800). Fourier transformation infrared (FT-IR) was tested using a spectrometer at a wavenumber covering the range of 400–4,000 cm−1. To measure band gap of these composites, UV–Vis light absorption was recorded on the Diffuse Reflectance spectrophotometer UV–vis. Nitrogen adsorption desorption tests were executed on a Micrometrics (Tristar 3000) instrument. Transmission electron microscope (TEM, JEOL LED JSM-6700F microscope, Japan) was used to investigate microstructure. Electrochemical impedance spectra (EIS) were tested via using a CHI660D workstation at room temperature. The electrochemical performances of the Fe-Ti/SF, Fe/SF and Ti/SF were analyzed. The working electrode were Fe-Ti/SF, Fe/SF and Ti/SF, respectively. The counter electrode was the Pt plate electrode and reference electrode were the calomel electrode. The electrolyte of the EIS measurements was the Na2SO4 aqueous solution (0.2 mol L−1).

Photocatalytic tests

The adsorption and photocatalytic performance of the Fe-Ti/SF, Fe/SF and Ti/SF were tested by photocatalysis degradation of MB. In the experiment, 0.2 g of fabricated composite were added into 200 mL of methylene blue (10 ppm). The photocatalytic tests were driven by irradiation with the 300 W Xenon lamp for 120 min. Before the light irradiation, the reaction system was stirred for 40 min in darkness to ensure the adsorption–desorption equilibrium. The methylene blue was taken at given time interval (20 min). The solutions were centrifuged under 4,000 rpm before analysis.

Results and discussion

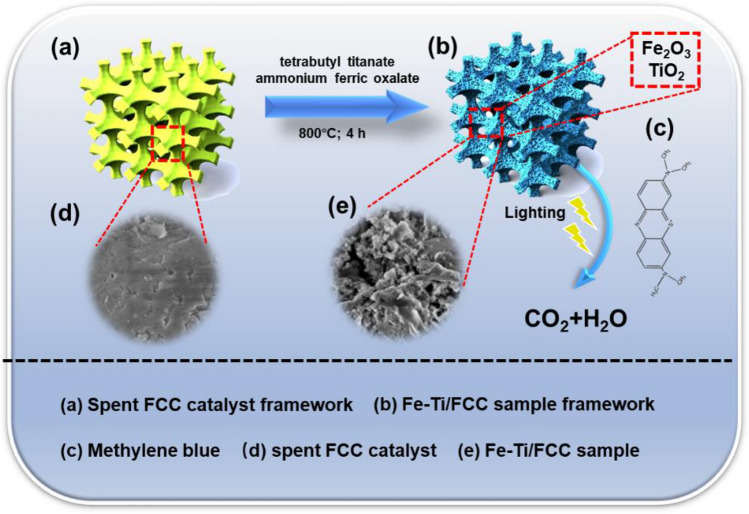

Figure 1 shows schematic illustration of the Fe-Ti/SF composite fabrication process. In a typical experimental procedure, 0.85 mL tetrabutyl titanate and 0.31 g ammonium ferric oxalate were dissolved into 4 mL of H2O2 solution (~ 30%). 0.85 mL tetrabutyl titanate and 0.31 g ammonium ferric oxalate were dissolved into 4 mL of H2O2 solution (~ 30%). Then 4 g spent FCC catalyst was added into this solution. Finally, this mixture was grinded for 2 h and calcined at 800 °C for 4 h. The degradation efficiency of methylene blue can be used to evaluate the photocatalytic performance of Fe-Ti/SF composite. The methylene blue can be degraded into the carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O) at last.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration for the Fe-Ti/SF composites fabricated process. (a) spent FCC catalyst framework, (b) Fe-Ti/SF framework, (c) methylene blue, (d) SEM images of spent FCC catalyst and (e) Fe-Ti/SF.

XRD patterns of the spent FCC catalyst, Fe-Ti/SF, Fe/SF and Ti/SF are shown in Fig. 2 (2-Theta range from 5° to 80°). Figure 2a shows XRD patterns of the spent FCC catalyst. There are four diffraction peaks at 6.3°, 10.3°, 12.1° and 15.9°, which can be indexed to (111), (220), (311) and (331) planes of zeolite Y phase (JCPDS No. 77-1551), respectively. Figure 2b,c show the XRD patterns of the Fe/SF and Fe-Ti/SF composite. The intensity of the peak (111) in zeolite Y phase decreases after being loaded Fe2O3 or TiO2. In the range of 12°–25°, the peak intensity is higher than Fig. 2a. In Fig. 2d, there are three peaks at 26.4°, 35.3° and 40.1°. These peaks are corresponded to the (101), (004) and (200) planes of the TiO2 phase (JCPDS card No. 73-1764), respectively. The size of the loaded TiO2 is small, which causes the low diffraction peak. Compared with the zeolite Y (111), the diffraction peaks intensity of Fe2O3 is lower. Therefore, there no obvious diffraction peaks of Fe2O3.

Figure 2.

XRD patterns of these samples. (a) spent FCC catalyst, (b) Fe/SF, (c) Fe-Ti/SF and (d) Ti/SF.

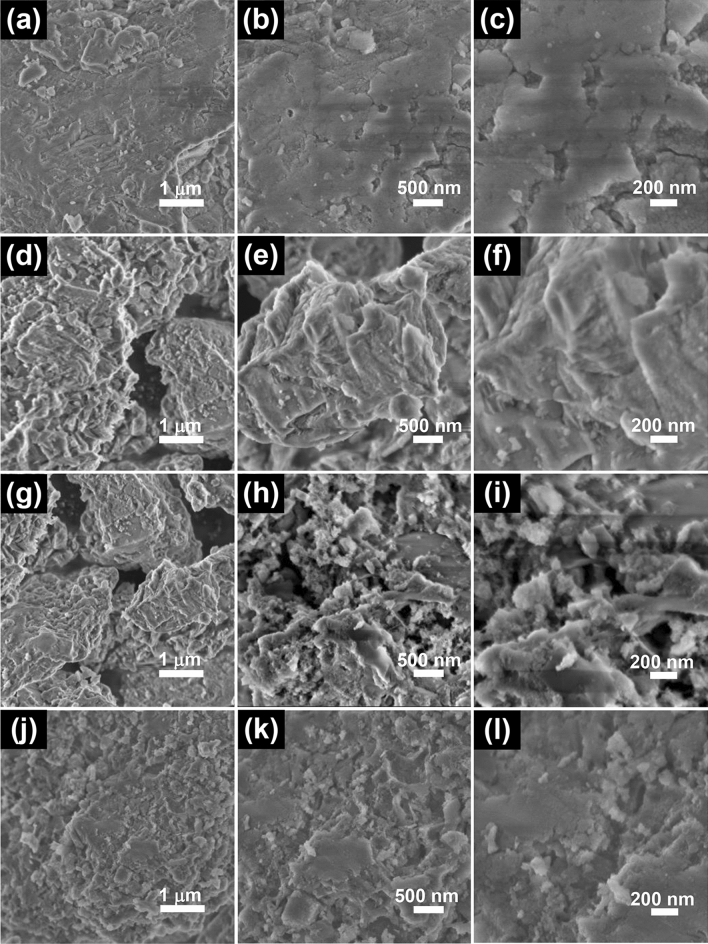

Figure 3 presents scanning electron microcopy (SEM) images of the spent FCC catalyst, Fe/SF, Fe-Ti/SF and Ti/SF samples. In Fig. 3a–c, there are some cracks on the surface. In Fig. 3d, the surface of this composite is covered with Fe2O3. In Fig. 3e–f, the peripheral surface of the Fe/SF is coarse. Figure 3g–i show the Fe-Ti/SF composite, this composite is covered with Fe2O3 and TiO2. In Fig. 3i, because the TiO2 deposits in clusters of irregular shapes, the surface of Fe-Ti/SF composite is rough and jagged. Figure 3j–l show the morphologies of the Ti/SF composite. The TiO2 particles are loaded on the surface of supporter. As shown in Fig. 3l, the TiO2 particles with diameter raging from 50 to 200 nm. There is an aggregation phenomenon between TiO2. EDS mappings of the Fe-Ti/SF composite are shown in Supplementary Figure S1. It shows the corresponding mappings of Fe-Ti/SF composite, which clearly indicate the homogeneous of Si, O, Al, Fe and Ti elements. The ingredient of zeolite Y are Al2O3 and SiO2. The Al, Si and O elements originate from zeolite Y, the Fe and Ti are loaded on the zeolite Y.

Figure 3.

SEM images of the spent FCC catalyst, Fe-Ti/SF, Fe/SF and Ti/SF samples with different morphologies. (a–c) spent FCC, (d–f) Fe-Ti/SF, (g–i) Fe/SF, (j–l) Ti/SF.

XPS spectra are used to identify the valence states of the elements of the Fe-Ti/SF composite. Supplementary Figure S2 shows the XPS survey spectrum, which suggests the presence of Fe, Ti, Al, Si and O. In Supplementary Figure S2a, the peaks of Fe 2p3/2 and Fe 2p1/2 are overlap, the three binding energy peaks at 712.0, 721.6 and 725.7 eV. In Supplementary Figure S2b, two banding energy peaks at 458.7 and 464.3 eV correspond to the characteristic of the Ti 2p3/2 and Ti 2p1/2. In Supplementary Figure S2c, the peak of Al 2p is overlap, the banding energy peak at 74.6 eV. In Supplementary Figure S2d, the peak of Si 2p is overlap, the banding energy peak at 102.9 eV. In Supplementary Figure S2e, the binding energy peak at 531.8 eV correspond to the characteristic of the O 1 s.

Figure 4 shows the TEM images of the Fe-Ti/SF composite. In Fig. 4a–c, the Fe2O3 and TiO2 particles are attached to the surface of the spent FCC catalyst. The crystallography of the Fe-Ti/SF composite is investigated with high-resolution TEM (HRTEM). In the Fig. 4d, the nanostructured heterojunction is formed between Fe2O3 and TiO2. The intimately contacted interface is important for accelerating the separation of the electrons and holes. The HRTEM image in Fig. 4d shows two kinds of lattice fringes, the interplanar crystal spacing of 0.352 and 0.252 nm are corresponded TiO2 (101) and Fe2O3 (110), respectively. More TEM images of the Fe-Ti/SF composite are shown in Supplementary Figure S3a–c. The dark color regions under TEM indicate thickness of the zeolite Y. The TEM images further show that Fe2O3 and TiO2 are loaded on the surface of supporter.

Figure 4.

(a–c) TEM images of the Fe-Ti/SF, (d) HRTEM images of the Fe-Ti/SF.

In Fig. 5, the macropores properties of the spent FCC catalyst, Fe/SF, Fe-Ti/SF and Ti/SF are analyzed. These insets show the pore diameter of these samples. All the samples show the type-II isotherms, which are corresponded of macropores materials (IUPAC classification). The isotherms of these samples exhibit H3 hysteresis loops associated with the presence of macropores. The pore diameter of the spent FCC catalyst, Fe/SF, Fe-Ti/SF and Ti/SF are 5.6, 5.8, 5.9 and 5.8 nm, respectively. It shows that these samples are macroporous. The surface areas of these composites (spent FCC catalyst, Fe/SF, Fe-Ti/SF and Ti/SF) are calculated to be 226.3, 253.7, 264.5 and 235.2 m2 g−1, respectively. Due to the large surface area, these samples can absorb more methylene blue.

Figure 5.

Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) nitrogen adsorption and desorption isotherms of (a) spent FCC catalyst, (b) Fe/SF, (c) Fe-Ti/SF and (d) Ti/SF. The corresponding pore size distribution curves are illustrated in the inset.

As shown in Supplementary Figure S4, the UV–Vis absorbance spectra of the Fe-Ti/SF, Fe/SF and Ti/SF composites were evaluated. The adsorption edges of the Fe-Ti/SF, Fe/SF and Ti/SF composites are 510, 540 and 400 nm, respectively. The Kubelka–Munk function is applied to determine the band gaps of Fe-Ti/SF, Fe/SF and Ti/SF composites. As shown in inset of the Supplementary Figure S2, the band gaps of the Fe-Ti/SF, Fe/SF and Ti/SF composites from the energy versus [F(R∞)hv]n can be estimated. R∞ and F(R∞) are the limiting reflectance and Kubelka–Munk function, respectively. The slope of the Tauc plot fit well at n = 1/2, which indicated an indirect transition. The band gaps of the Fe-Ti/SF, Fe/SF and Ti/SF composites are 2.23, 1.98 and 3.0 eV, respectively30,31. The partial absorption in the visible range is determined by the band gap energy value, which shows that these samples have potential photocatalytic activity.

The schematic diagram of the band position of Fe-Ti/SF is shown in Fig. 6. The interparticle electrons intensity of Fe-Ti/SF is higher than the single component Fe2O3 or TiO2, which can promote the separation of electrons and holes. The Fermi levels of the Fe2O3 and TiO2 are lower than their conduction band (CB). In the heterostructure, the Fermi levels of Fe2O3 and TiO2 reach a new equalization state. There is a new electric field between the Fe2O3 and TiO2. The interparticle electrons rapidly transfer in the heterostructure between the Fe2O3 and TiO2. The electrons of a higher CB transfer to the lower one, the holes move in the opposite way. The electrons of Fe2O3 (CB) transfer to TiO2 (CB). The holes of TiO2 (VB) transfer to Fe2O3 (VB). The electrons are trapped by O2 (dissolved in the methylene blue) to form ⋅O2, the ⋅O2 oxidized the methylene blue. Finally, the methylene blue is degraded in CO2 and H2O.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of the band position of Fe-Ti/SF.

The electron transfer efficiency can be measured by the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). As shown in Fig. 7, the radius (Nyquist plot) of the Fe-Ti/SF is much smaller than those of Fe/SF and Ti/SF, which shows that Fe-Ti/SF has lower electron transfer resistance. The heterostructure of the Fe2O3 and TiO2 enhances the separation of the electrons and holes.

Figure 7.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) analysis of Fe-Ti/SF, Fe/SF and Ti/SF.

In Fig. 8, the Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) spectra of the spent FCC catalyst, Fe/SF, Fe-Ti/SF and Ti/SF are measured. The peak at 3,425 cm−1 corresponds to the absorption the stretching vibration of O‒H group stretching. The peak at 1645 cm−1 corresponds to the bending vibration absorption of the O‒H32. In Fig. 8a–d, the peak at 1,082 cm−1, 848 cm−1 and 456 cm−1 correspond to the stretching or bending vibration of the Si–O–Si33,34. In the samples of the (b) Fe/SF and (c) Fe-Ti/SF, the absorption peaks at 560, 610, 1,100, and 3,500 cm−1 correspond to the stretching vibration of Fe–O. In Fig. 8d, the peaks at 910 cm−1 to 960 cm−1 corresponds to the stretching vibration of the Ti‒O‒Si.

Figure 8.

FT-IR spectra of (a) spent FCC catalyst, (b) Fe/SF, (c) Fe-Ti/SF and (d) Ti/SF, respectively.

In Fig. 9, the photocatalytic performance of the Fe-Ti/SF is evaluated by the methylene blue degradation experiment. With increase of the reaction time, the methylene blue characteristic peak is gradually declined, which indicates concentration of methylene blue is gradually declined. The photocatalytic degradation efficiency of the methylene blue is ~ 94.2%. The inset of Fig. 9 shows the color change of the methylene blue. Figure. S5 shows the degradation of methylene blue with the Fe-Ti/SF, Fe/SF and Ti/SF composites. The methylene blue degradation efficiencies (with Fe-Ti/SF, Fe/SF and Ti/SF composites) are ~ 94.2%, ~ 22.3% and ~ 54.0% in 120 min, respectively. The results show that the Fe-Ti/SF composite has the highest photocatalytic activity. Supplementary Figure S6 shows the photocatalytic degradation efficiency of methylene blue with Fe-Ti/SF, Fe2O3-TiO2, Fe2O3 and TiO2.

Figure 9.

UV–Vis adsorption spectra of degradation of methylene blue with Fe-Ti/SF composite. Inset shows the photographs of methylene blue solution. The inset shows the photographs of methylene blue solution: the 0 min, 20 min, 40 min, 60 min, 80 min, 100 min and 120 min, which corresponds with (a–g), respectively.

As shown in Fig. 10, the recycling experiments of the Fe-Ti/SF composite are implemented by the methylene blue degradation, which evaluates the stability of this Fe-Ti/SF composite. After the fourth cycle reaction, the photocatalytic activity of the Fe-Ti/SF composite is not significant loss. The degradation efficiency of the methylene blue with Fe-Ti/SF composite decreases to 84.0% from the pristine degradation efficiency (94.2%). These results indicate that the Fe-Ti/SF exhibit a relatively stable photocatalytic performance.

Figure 10.

Recycling experiments of photocatalytic reduction of methylene blue with Fe-Ti/SF.

Conclusion

In summary, the Fe-Ti/SF, Fe/SF and Ti/SF composites have been successfully fabricated via a modified-impregnation method. The adsorption and degradation tests were carried out for 120 min to evaluate Fe-Ti/SF, Fe/SF and Ti/SF photocatalytic performance, the methylene blue degradation efficiencies are ~ 94.2%, ~ 22.3% and ~ 54.0%, respectively. The interparticle electrons rapidly transfer in the heterostructure between the Fe2O3 and TiO2. The radius (Nyquist plot) of the Fe-Ti/SF is much smaller than those of Fe/SF and Ti/SF, which shows Fe-Ti/SF has lower electron transfer resistance and fast charge transfer rate. After the fourth cycle reaction, the photocatalytic activity of the Fe-Ti/SF composite reduces 10.2% (the photocatalytic degradation efficiency of methylene blue is from 94.2 to 84.0%). The spent FCC catalyst loaded with Fe2O3 and TiO2 has stable photocatalytic performance. This modified-impregnation method, the spent FCC catalyst is used as the photocatalyst supports, which provides a potential method to dispose the spent FCC catalyst in the areas of environment protection.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Talent Scientific Research Fund of LSHU (#2020XJJL-001) and the National Key R&D Program of China (#2018YFF0215200).

Author contributions

J.X. conceived the idea and designed the experiments. T.Z. collected and analyzed the data and wrote the main manuscript. J.Z. contributed substantially to revisions and supervised paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-69643-2.

References

- 1.Shi J, et al. Nitrogen chemistry and coke transformation of FCC coked catalyst during the regeneration process. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:27309. doi: 10.1038/srep27309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferella F, et al. Synthesis of zeolites from spent fluid catalytic cracking catalyst. J. Clean. Prod. 2019;230:910–926. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.05.175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vogt ETC, Weckhuysen BM. Fluid catalytic cracking: Recent developments on the grand old lady of zeolite catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:7342–7370. doi: 10.1039/C5CS00376H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yuan L, et al. Adsorption and mechanistic study for phosphate removal by magnetic Fe3O4-doped spent FCC catalysts adsorbent. Chemosphere. 2019;219:183–190. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.11.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen X, et al. Synthesis, characterization and activity performance of nickel-loaded spent FCC catalyst for pine gum hydrogenation. RSC Adv. 2019;9:6515–6525. doi: 10.1039/C8RA07943A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Le T, Wang Q, Ravindra AV, Li X, Ju S. Microwave intensified synthesis of zeolite-Y from spent FCC catalyst after acid activation. J. Alloys Compd. 2019;776:437–446. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.10.316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu L, Khalil F, Smith GM, Yilmaz B, McGuire R. Effect of solvent on the impregnation of contaminant nickel for laboratory deactivation of FCC catalysts. Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 2015;207:195–199. doi: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2014.12.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen CM, Yu J, Yoza BA, Li QX, Wang G. A novel “wastes-treat-wastes” technology: Role and potential of spent fluid catalytic cracking catalyst assisted ozonation of petrochemical wastewater. J. Environ. Manag. 2015;152:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akcil A, Vegliò F, Ferella F, Okudan MD, Tuncuk A. A review of metal recovery from spent petroleum catalysts and ash. Waste Manag. 2015;45:420–433. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Su B, Shi L, Liu N, Wang X, Meng X. Removal of sulfur compounds from LPG by heteropoly acid-modified spent FCC catalyst. Appl. Organomet. Chen. 2019;33:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trivedi PA, Solanki NM, Butani N, Parikh PA. Investigation on corrosion control of mild steel buried in soil by spent FCC catalyst coating. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2014;20:2264–2271. doi: 10.1016/j.jiec.2013.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le-Phuc N, et al. Towards efficient extraction of La(III) from spent FCC catalysts by alkaline pre-treatment. Miner. Eng. 2018;127:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.mineng.2018.07.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neves R, Vicente C, Castela A, Montemor MF. Durability performance of concrete incorporating spent fluid cracking catalyst. Cement. Concret. Comp. 2015;55:308–314. doi: 10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2014.09.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scherzer J. Octane-enhancing, zeolitic FCC catalysts: Scientific and technical aspects. Catal. Rev. 1989;31:215–354. doi: 10.1080/01614948909349934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trivedi PA, Parmar PR, Parikh PA. Spent FCC catalyst: Potential anti-corrosive and anti-biofouling material. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2014;20:1388–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.jiec.2013.07.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang T, et al. Preparation of ordered TiO2 nanofibers/nanotubes by magnetic field assisted electrospinning and the study of their photocatalytic properties. Ceram. Int. 2019;45:14404–14410. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.04.158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohammadi M, Rezaee Roknabadi M, Behdani M, Kompany A. Enhancement of visible and UV light photocatalytic activity of rGO-TiO2 nanocomposites: The effect of TiO2/graphene oxide weight ratio. Ceram. Int. 2019;45:12625–12634. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.02.129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao Y, et al. Tuning oxygen vacancies in ultrathin TiO2 nanosheets to boost photocatalytic nitrogen fixation up to 700 nm. Adv. Mater. 2019;31:1–9. doi: 10.1002/adma.201806482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li X, Qian JH, Xu JS, Xing JJET. Synthesis, characterization and electrical properties of TiO2 modified with SiO2 and antimony-doped tin oxide. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2018;29:12100–12108. doi: 10.1007/s10854-018-9316-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang W, et al. Edge-enriched ultrathin MoS2 embedded yolk-shell TiO2 with boosted charge transfer for superior photocatalytic H2 evolution. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019;29:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Low J, Dai B, Tong T, Jiang C, Yu J. In situ irradiated X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy investigation on a direct Z-scheme TiO2/CdS composite film photocatalyst. Adv. Mater. 2019;31:1–5. doi: 10.1002/adma.201807920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shirai K, et al. Water-assisted hole trapping at the highly curved surface of nano-TiO2 photocatalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:1415–1422. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b11061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Q, Zhou M, Zhang ZM, Tang T, Wang T. Preparation of TiO2 nanotubes/reduced graphene oxide binary nanocomposites enhanced photocatalytic properties. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2017;28:9416–9422. doi: 10.1007/s10854-017-6683-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perveen S, Farrukh MA. Influence of lanthanum precursors on the heterogeneous La/ SnO2–TiO2 nanocatalyst with enhanced catalytic activity under visible light. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2017;28:10806–10818. doi: 10.1007/s10854-017-6858-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ilkhechi NN, Ghobadi N, Akbarpour MR. Enhanced optical and photo catalytic properties of V and La co doped TiO2 nanoparticles. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2017;28:6426–6434. doi: 10.1007/s10854-016-6328-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Krafft KE, Wang C, Lin W. Metal-organic framework templated synthesis of Fe2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite for hydrogen production. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012;24:2014–2018. doi: 10.1002/adma.201200330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silvestri S, Foletto EL. Preparation and characterization of Fe2O3/TiO2/clay plates and their use as photocatalysts. Ceram. Int. 2017;43:14057–14062. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.07.140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davari N, Farhadian M, Nazar ARS, Homayoonfal M. Degradation of diphenhydramine by the photocatalysts of ZnO/Fe2O3 and TiO2/Fe2O3 based on clinoptilolite: Structural and operational comparison. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017;5:5707–5720. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2017.10.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eskandari P, Farhadian M, Solaimany Nazar AR, Jeon B-H. Adsorption and photodegradation efficiency of TiO2/Fe2O3/PAC and TiO2/Fe2O3/zeolite nanophotocatalysts for the removal of cyanide. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019;58:2099–2112. doi: 10.1021/acs.iecr.8b05073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu JS, Pan CS, Takata T, Domen K. Photocatalytic overall water splitting on the perovskite-type transition metal oxynitride CaTaO2N under visible light irradiation. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:7191–7194. doi: 10.1039/C5CC01728A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang HD, et al. Microwave-assisted synthesis of Cu2O microcrystals with systematic shape evolution from octahedral to cubic and their comparative photocatalytic activities. RSC Adv. 2014;4:38059–38063. doi: 10.1039/C4RA05015K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yosefi L, Haghighi M. Fabrication of nanostructured flowerlike p-BiOI/p-NiO heterostructure and its efficient photocatalytic performance in water treatment under visible-light irradiation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018;220:367–378. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.08.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Król M, Minkiewicz J, Mozgawa W. IR spectroscopy studies of zeolites in geopolymeric materials derived from kaolinite. J. Mol. Struct. 2016;1126:200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2016.02.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang R, Chen T, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Wang G. Core-shell TiO2@SiO2 catalyst for transesterification of dimethyl carbonate and phenol to diphenyl carbonate. Chin. J. Catal. 2014;35:457–461. doi: 10.1016/S1872-2067(14)60059-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.