Abstract

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a serious postoperative complication that occurs following laparoscopic surgery. However, its association with robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP), the gold standard surgery for prostate cancer, is controversial. The current cohort included 257 patients with prostate cancer who underwent either RARP (n=187) or open radical prostatectomy (ORP; n=70). Patient serum creatinine concentration was measured at the following six time points: Prior to surgery, on postoperative day 0 (immediately after surgery), on postoperative day 1, 3 months after surgery, 1 year after surgery and 2 years after surgery. AKI was diagnosed according to the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria. A total of 25 RARP and 0 ORP patients met the KDIGO criteria on postoperative day 0. On postoperative day 1, 3 RARP and 2 ORP patients met the criteria, suggesting that AKI after RARP was a transient phenomenon. At 1 and 2 years after surgery, 5 of 257 patients exhibited a significant increase in serum creatinine concentrations from baseline results. Clinicians should be aware of transient AKI occurring after RARP, rather than ORP, to ensure better perioperative management in patients undergoing radical prostatectomy.

Keywords: acute kidney injury, complication, prostate cancer, renal function, robot-assisted radical prostatectomy

Introduction

Robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP) is currently the gold standard surgical procedure for localized prostate cancer (PC). Although RARP is reportedly associated with safer surgery and better oncological outcomes than conventional open radical prostatectomy (ORP) (1), RARP has risks of specific complications due to the use of carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum and a steep Trendelenburg position (2,3). Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a serious postoperative complication especially after laparoscopic surgery; however, the link between RARP and AKI is controversial (2-6). A previous study reported that the postoperative serum creatinine (sCre) concentration increased in patients who underwent RARP but decreased in those who underwent ORP (2). To the contrary, another study reported that the incidence of AKI after RARP was significantly lower than that after ORP (5). Yet other studies reported that postoperative renal function was unaltered in patients who underwent RARP (3,6). Therefore, there is currently no consensus regarding the risk of AKI after RARP. Furthermore, long-term follow-up data on changes in renal function after RARP are also lacking. The present study aimed to compare the incidences of postoperative AKI between RARP and ORP, as well as long-term changes in postoperative renal function between them.

Patients and methods

Patients and surgical techniques

We retrospectively reviewed 257 patients with PC who underwent either RARP (n=187) or ORP (n=70) at our institution from 2011 to 2014. Since RARP started to be covered by Japanese public health insurance in 2012, most patents underwent ORP between 2011 and the first half of 2012, while majority of patients received RARP after the second half of 2012. We performed RARP using the peritoneal approach as previously described (1) and ORP using the conventional retroperitoneal approach, respectively. Patients who underwent RARP were placed in the Trendelenburg position at an angle of 25̊ from the horizontal plane. Lymph node dissection was performed in RARP patients who were predicted to have ≥5% lymph node metastasis according to the Japan PC nomogram (7) and in all ORP patients. Cavernous nerve preservation was carried out on the cancer-negative lobe in RARP patients; bilateral preservation was limited only when the patient's cancer was located at the transitional zone. In ORP patients, cavernous nerve preservation was performed in a limited number of patients. All patients underwent pretreatment evaluations, including blood tests, chest x-rays, computed tomography, and bone scintigraphy. Posttreatment monitoring was generally performed with routine blood tests including prostate-specific antigen (PSA) every 1-6 months.

The present study was approved by the Internal Institutional Review Board of Graduate School of Medicine and Faculty of Medicine, University of Tokyo (approval no. 3124). Written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to surgery. Patients were given the opportunity to decline participation in the study through the opt-out form on our website.

Evaluation protocol of postoperative renal function and definition of AKI

The sCre concentration was measured at the following six time points: Prior to surgery, immediately after surgery (postoperative day 0 [POD0]), on POD1, 3 months after surgery, 1 year after surgery, and 2 years after surgery. Postoperative AKI on POD0 and POD1 was diagnosed according to the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria (8,9): An increase in sCre by ≥0.3 mg/dl within 48 h, an increase in sCre to ≥1.5 times baseline within the previous 7 days, or a urine output rate of ≤0.5 ml/kg/h for 6 h (note that the last criterion was not applicable in this study because of inaccurate urine output measurement due to possible urine leakage after prostatectomy).

Statistical analysis

Differences in clinical variables between the RARP and ORP groups were evaluated using the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables. Correlations between clinicopathological variables and AKI on POD0 were assessed by the χ2 test for univariate analysis. Continuous variables were dichotomized by their median values. All significant variables in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis using logistic regression. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro version 14.2.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics and postoperative AKI

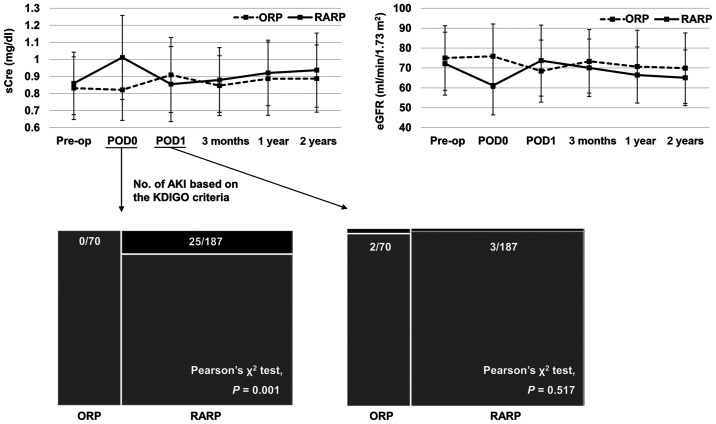

The patients' baseline characteristics are summarized in Table I. As shown in Fig. 1, 25 of 187 (13.4%) patients who underwent RARP met the KDIGO's AKI criteria on POD0, while none of the patients who underwent ORP met the criteria (Pearson's χ2 test, P=0.001). On POD1, 3 of 187 (1.6%) patients who underwent RARP and 2 of 70 (2.9%) patients who underwent ORP met the criteria (P=0.517).

Table I.

Patient baseline characteristics.

| Variables | Total (257) | ORP (70) | RARP (187) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 67 (63-71) | 67 (61-71) | 66 (63-70) | 0.898a |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 24.0 (22.1-25.5) | 23.8 (21.6-25.8) | 24.1 (22.0-25.2) | 0.791a |

| Initial PSA, ng/ml, median (IQR) | 7.6 (5.8-10.9) | 8.1 (6.0-11.8) | 7.4 (5.5-10.6) | 0.131a |

| Preoperative sCre, mg/dl, median (IQR) | 0.82 (0.73-0.95) | 0.81 (0.70-0.90) | 0.83 (0.73-0.96) | 0.154a |

| Prostate volume, ml, median (IQR) | 29.9 (22.4-40.3) | 32.0 (21.4-41.9) | 29.4 (22.5-40.0) | 0.581a |

| Pathological T stage, n (%) | 0.306b | |||

| ≤pT2 | 198 (77.0) | 57 (81.4) | 141 (75.4) | |

| ≥pT3 | 59 (23.0) | 13 (18.6) | 46 (24.6) | |

| Pathological N stage, n (%) | 0.001b,c | |||

| pN0/x | 253 (98.4) | 66 (94.3) | 187(100) | |

| pN1 | 4 (1.6) | 4 (5.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Pathological Gleason score, n (%) | 0.081b | |||

| ≤7 | 199 (77.4) | 49 (70.0) | 150 (80.2) | |

| ≥8 | 58 (22.6) | 21 (30.0) | 37 (19.8) | |

| Surgical time, min, median (IQR) | 231 (199-265) | 209 (190-243) | 237 (204-271) | 0.001a,c |

| Blood loss, ml, median (IQR) | 450 (150-865) | 1075 (728-1753) | 300 (100-500) | <0.001a,c |

| Fluid infusion, ml, median (IQR) | 2100 (1800-2750) | 2975 (2600-3713) | 2000 (1700-2350) | <0.001a,c |

Data were analyzed using

aMann-Whitney U and

bPearson's χ2 tests.

cStatistically significant data. ORP, open radical prostatectomy; RARP, robot-assisted radical prostatectomy; IQR, interquartile range; BMI, body mass index; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; sCre, serum creatinine.

Figure 1.

sCre levels in patients undergoing RARP or ORP at the six allocated time points: Prior to surgery, immediately after surgery (POD0), POD1, 3 months after surgery, 1 year after surgery and 2 years after surgery. The number of patients with postoperative AKI on POD0 and POD1, based on the KDIGO criteria, are presented. None of 70 (0%) patients with ORP and 25 of the 187 (13.4%) patients with RARP met the KDIGO's AKI criteria on POD0 (Pearson's χ2 test; P=0.001). Additionally, 2 of the 70 (2.9%) patients with ORP and 3 of the 187 (1.6%) patients with RARP met the same criteria (P=0.517) on POD1. For reference, changes in eGFR are also presented in the upper right corner. data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. sCre, serum creatinine; RARP, robot-assisted radical prostatectomy; ORP, open radical prostatectomy; POD, postoperative day; AKI, acute kidney injury; KDIGO, Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Long-term follow-up data of postoperative renal function

Three months after surgery, none of the 28 patients who met the KDIGO criteria on either POD0 or POD1 had a prolonged significant increase in sCre, whereas 2 of 257 (0.8%) patients (both in the RARP group) had a new increase in sCre from baseline. One year after surgery, 5 of 257 (1.9%) patients (4 in the RARP group and 1 in the ORP group) had a significant increase in sCre from baseline, whereas 5 (1.9%) patients (all in the RARP group) had a significant increase 2 years after surgery.

Correlations between clinicopathological variables and AKI on POD0

In the univariate analysis, the procedure type (ORP vs. RARP), initial PSA concentration (<7.55 vs. ≥7.55 ng/ml), preoperative sCre (<0.82 vs. ≥0.82 mg/dl), pathological T stage (≤pT2 vs. ≥pT3), and surgical time (<231 vs. ≥231 min) were significantly associated with AKI on POD0 (Table II). The multivariate analysis incorporating these five variables showed that performance of RARP and a surgical time of ≥231 min were independent predictors of AKI on POD0. However, the odds ratio for the procedure type was not convergent because there was no event in the ORP group. Therefore, these results might be used for reference purposes only.

Table II.

Univariate and multivariate analyses assessing associations between clinicopathological variables and acute kidney injury on postoperative day 0.

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | P-value | Likelihood ratio P-value | Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | Odds ratio P-value |

| Procedure type (ORP vs. RARP) | 0.001b | <0.001b | Not convergent | 0.988 |

| Age (<67 vs. ≥67 yearsa) | 0.067 | |||

| BMI (<24 vs. ≥24 kg/m2a) | 0.061 | |||

| Initial PSA (<7.55 vs. ≥7.55 ng/mla) | 0.022b | 0.091 | 0.44 (0.16 to 1.17) | 0.099 |

| Preoperative sCre (<0.82 vs. ≥0.82 mg/dla) | 0.044b | 0.138 | 0.48 (0.18 to 1.29) | 0.147 |

| Prostate volume (<29.9 vs. ≥29.9 mla) | 0.541 | |||

| Pathological T stage (≤pT2 vs. ≥pT3) | 0.033b | 0.193 | 0.52 (0.19 to 1.38) | 0.187 |

| Pathological N stage (0/x vs. 1) | 0.508 | |||

| Pathological Gleason score (≤7 vs. ≥8) | 0.494 | |||

| Surgical time (<231 vs. ≥231 mina) | <0.001b | 0.002b | 0.20 (0.07 to 0.64) | 0.006b |

| Blood loss (<450 vs. ≥450 mla) | 0.115 | |||

| Fluid infusion (<2100 vs. ≥2100 mla) | 0.745 | |||

aMedian data.

bStatistically significant data. ORP, open radical prostatectomy; RARP, robot-assisted radical prostatectomy; BMI, body mass index; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; sCre, serum creatinine.

Discussion

In the present study, a large number of patients who underwent RARP met the KDIGO's AKI criteria immediately after surgery (POD0), whereas patients who underwent ORP (control group) did not. Nevertheless, on POD1, only a few patients in both treatment groups met the criteria, suggesting that AKI after RARP was just a transient phenomenon. Furthermore, the long-term follow-up data demonstrated that only a few patients developed a decline in renal function after surgery regardless of the procedure type. Therefore, the transient AKI phenomenon immediately after RARP might have little clinical significance.

The association between RARP and AKI is controversial (2-6). One study showed results similar to ours in that the postoperative sCre concentration increased in patients who underwent RARP but decreased in those who underwent ORP (2). However, another study showed a completely opposite result; i.e., the incidence of AKI after RARP was significantly lower than that after ORP (5). In yet other studies, postoperative renal function was unaltered in patients who underwent RARP (3,6). These inconsistencies might be attributable to the diagnostic time of AKI or the timing of blood sampling, given that fewer patients who underwent RARP than ORP in our study met the AKI criteria on POD1 (<24 h after surgery).

Impairment of renal function after laparoscopic surgery has been widely reported, and the common underlying mechanisms include increased intra-abdominal pressure and carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum (4,5,10). Under conditions of pneumoperitoneum, direct compression of the intra-abdominal vessels and renal parenchyma can decrease cardiac output, renal blood flow, and urine output (10). These physiologic changes stimulate the renin-angiotensin system and further decrease renal blood flow, eventually resulting in impairment of renal function (4,5). Additionally, the steep Trendelenburg position required for RARP could be an additional cause of renal impairment, although the mechanism has not been well documented (2,3). Other possible mechanisms include pseudo-renal failure due to intraperitoneal urine leakage during prostatectomy; however, this may depend on the amount of leaked urine (11). We consider that in general, the amount of leaked urine during prostatectomy is not large enough to cause pseudo-renal failure and that the risk of pseudo-renal failure is likely similar between RARP and ORP (Note: No patient receiving ORP developed AKI immediately after surgery, although there should exist a certain amount of urine leakage). Finally, prerenal AKI can be suspected because of decreased fluid replacement during surgery; notably, however, fluid infusion was not associated with AKI on POD0 in the present study, even in the univariate analysis.

In conclusion, this retrospective single-center study revealed transient AKI immediately after RARP, but not after ORP. However, this finding might be of little clinical significance given the long-term follow-up data of postoperative renal function. Nevertheless, this transient AKI phenomenon immediately after RARP should be recognized to provide better perioperative management of patients undergoing radical prostatectomy.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

AN and ST conceived and designed the present study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. MS conceived, designed and supervised the study. TK, KU and TF acquired data including patients' baseline characteristics, perioperative factors and laboratory data. TK, KU and TF also revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. HF and HK supervised the study, acquired patient pre-operative data, drafted the manuscript and were involved in revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was approved by the Internal Institutional Review Board of Graduate School of Medicine and Faculty of Medicine, University of Tokyo (approval no. 3124). Written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to surgery. Patients were given the opportunity to decline participation in the study through the opt-out form on our website.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Fujimura T, Fukuhara H, Taguchi S, Yamada Y, Sugihara T, Nakagawa T, Niimi A, Kume H, Igawa Y, Homma Y. Robot-assisted radical prostatectomy significantly reduced biochemical recurrence compared to retro pubic radical prostatectomy. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(454) doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3439-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D'Alonzo RC, Gan TJ, Moul JW, Albala DM, Polascik TJ, Robertson CN, Sun L, Dahm P, Habib AS. A retrospective comparison of anesthetic management of robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy versus radical retropubic prostatectomy. J Clin Anesth. 2009;21:322–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saito J, Noguchi S, Matsumoto A, Jinushi K, Kasai T, Kudo T, Sawada M, Kimura F, Kushikata T, Hirota K. Impact of robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy on the management of general anesthesia: Efficacy of blood withdrawal during a steep Trendelenburg position. J Anesth. 2015;29:487–491. doi: 10.1007/s00540-015-1989-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li JR, Cheng CL, Weng WC, Hung SW, Yang CR. Acute renal failure after prolonged pneumoperitoneum in robot-assisted prostatectomy: A rare complication report. J Robot Surg. 2008;1:313–314. doi: 10.1007/s11701-007-0060-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joo EY, Moon YJ, Yoon SH, Chin JH, Hwang JH, Kim YK. Comparison of acute kidney injury after robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy versus retropubic radical prostatectomy: A propensity score matching analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(e2650) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahn JH, Lim CH, Chung HI, Choi SU, Youn SZ, Lim HJ. Postoperative renal function in patients is unaltered after robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2011;60:192–197. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2011.60.3.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naito S, Kuroiwav K, Kinukawav N, Goto K, Kogav H, Ogawa O, Murai M, Shiraishi T. Validation of Partin tables and development of a preoperative nomogram for Japanese patients with clinically localized prostate cancer using 2005 International Society of Urological Pathology consensus on Gleason grading: Data from the clinicopathological research group for localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 2008;180:904–909. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.05.047. Clinicopathological Research Group For Localized Prostate Cancer Investigators. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kellum JA, Lameire N, Aspelin P, Barsoum RS, Burdmann EA, Goldstein SL, Herzog CA, Joannidis M, Kribben A, Levey AS, et al. Kidney disease: Improving global outcomes (KDIGO) acute kidney injury work group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2012;(Suppl 2):1–138. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doi K, Nishida O, Shigematsuv T, Sadahirov T, Itami N, Iseki K, Yuzawa Y, Okada H, Koya D, Kiyomoto H, et al. Japanese clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury 2016 committee: The Japanese clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury 2016. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2018;22:985–1045. doi: 10.1007/s10157-018-1600-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wever KE, Bruintjes MH, Warlé MC, Hooijmans CR. Renal perfusion and function during pneumoperitoneum: A systematic review and meta-analysis of animal studies. PLoS One. 2016;11(e0163419) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kruger PS, Whiteside RS. Pseudo-renal failure following the delayed diagnosis of bladder perforation after diagnostic laparoscopy. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2003;31:211–213. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0303100214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.