Abstract

The current retrospective multicenter study evaluated the efficacy and safety of nanosomal docetaxel lipid suspension (NDLS; DoceAqualip) based chemotherapy in patients with gastric and gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) adenocarcinoma. The medical charts of patients with gastric and GEJ adenocarcinoma, who were treated with NDLS (50-75 mg/m2; 3 weekly cycles) based chemotherapy and followed-up from April 2014 to September 2018, were analyzed. The study endpoints included overall response rate (ORR) and disease control rate (DCR) in neoadjuvant and metastatic settings. Overall survival (OS) and safety were also evaluated. Of the 43 patients with gastric (n=39) and GEJ (n=4) adenocarcinoma, efficacy evaluation was available in 35 (neoadjuvant, 17/18 patients; metastatic, 18/25 patients). In the neoadjuvant setting, an ORR of 58.82% and a DCR of 94.11% were observed, whereas in the metastatic setting, the ORR was 77.77% and the DCR was 83.33%. In the neoadjuvant setting, at a follow-up ranging from 0.7 to 41.2 months, the median OS was not reached. In the metastatic setting, the median OS was 31.9 months at a follow-up ranging from 0.2 to 50.3 months. At least one adverse event (AE) was reported in 24 patients. Anemia, lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia were the most common hematological AEs, while nausea, vomiting and weakness were the most common non-hematological AEs. NDLS based treatment was well-tolerated without any new safety concerns. Overall, NDLS-based chemotherapy was effective and well-tolerated in the management of gastric and GEJ adenocarcinoma.

Keywords: NDLS, nanosomal docetaxel lipid suspension, gastric adenocarcinoma, gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the fifth most common cancer in the world (1,033,701 new cases; 5.7% of all cancer cases) with the third highest cancer-related mortality (782,685 deaths, 8.2% of all cases) as per GLOBOCAN 2018 data (1). In India, gastric cancer ranks fifth with regards to the number of newly diagnosed cases (57,394 cases [5.52%]), and cancer-related mortality (51,429 deaths [7.2%]) (1). Approximately, 95% cases of gastric cancer are gastric adenocarcinomas (GACs) (2,3) and most adenocarcinomas arise in the distal third of the stomach and gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) (4). The incidence of adenocarcinomas, in the proximal stomach and distal esophagus, has increased over the years (5).

Taxanes (docetaxel or paclitaxel), which disrupt the microtubule function and inhibit the process of cell division, have shown encouraging activity for the treatment of GAC (6,7). Docetaxel based chemotherapy has been shown to be effective and well-tolerated in the neoadjuvant therapy of gastric cancer (8-10). Furthermore, docetaxel in combination with a platinum agent (cisplatin/carboplatin/oxaliplatin) and 5-fluorouracil (FU) (DCF) is a recommended treatment option for advanced gastric cancer (11,12). Docetaxel as a monotherapy (7,13) or in combination with other antineoplastic agents such as cisplatin (14), 5-FU (15), irinotecan (16), carboplatin (17), and capecitabine (18) has demonstrated efficacy in advanced gastric and GEJ adenocarcinoma.

The conventional docetaxel formulation is associated with toxicities such as acute hypersensitivity reactions, cumulative fluid retention, peripheral neuropathy, severe nonimmunologic anaphylactoid reactions, infusion-site reactions, and alcohol intoxication, related to the formulation vehicles, polysorbate 80 and ethanol (19-23). Furthermore, these adverse effects are still observed despite corticosteroid and antihistamine premedications, which are generally used to limit these toxicities (24). A novel lipid-based formulation of docetaxel, nanosomal docetaxel lipid suspension (NDLS, DoceAqualip), which is devoid of polysorbate 80 and ethanol was developed to overcome these toxicity issues. NDLS is approved in India for the treatment of patients with advanced gastric adenocarcinoma, androgen independent (hormone refractory) metastatic prostate cancer (HRPC), locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer (MBC) after failure of prior chemotherapy, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) after failure of prior chemotherapy, and for the induction treatment of locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck (LA SCCHN). NDLS was developed based on the patented ‘NanoAqualip’ technology (patent numbers: Worldwide (WO2008127358), Europe (2076244), Japan (5917789) and Canada (CA2666322) (25) using lipids generally regarded as safe (GRAS) by the US Food and Drug Administration (USFDA). Docetaxel is added to high pressure homogenized soy phosphatidylcholine and sodium cholesteryl sulfate in sodium citrate buffer under continuous high pressure homogenization for the development of NDLS (25). The resultant nanosomal (<100 nm) particles (25) of NDLS may increase the delivery of docetaxel to tumor tissues due to damaged tumor vasculature, resulting in an enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect. This may result in a greater systemic availability of docetaxel (25,26) and thus, improved therapeutic outcomes can be potentially expected (27). In addition, polysorbate 80 and ethanol related toxicity issues can be circumvented as well.

The efficacy and safety of NDLS has been demonstrated in breast, ovarian, cervical, gastric, penile, hormone refractory prostate cancer, non-small cell lung cancer and sarcoma (28-32). We report here a multicenter, retrospective experience in real-life practice evaluating the efficacy and safety of NDLS based chemotherapy in the treatment of gastric and GEJ adenocarcinomas in the neoadjuvant and metastatic settings.

Materials and methods

Study design

In this multicenter, retrospective study, we analyzed the medical charts of adult patients who were treated with NDLS based chemotherapy as part of their routine clinical care for histopathologically proven gastric and GEJ adenocarcinoma. The data is captured from April 2014 to October 2018. The study endpoints were overall response rate [ORR: Proportion of patients achieving complete (CR)+partial response (PR)], disease control rate [DCR: CR+PR+stable disease (SD)] and overall survival (OS was defined as time from treatment to death due to any cause; for patients who were still alive at the time of data analysis or who were lost to follow-up, OS was censored at the last recorded date that the patient was known to be alive). Treatment response was evaluated using the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) 1.1(33). Incidence of adverse events (AEs) documented in the treatment charts were recorded and graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Criteria version 5.0. Similarly, data on deaths and discontinuations were captured from the patients' health records.

Ethics statement

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the OM Ethics Committee, Ahmedabad, India. The study was conducted in accordance with the Ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki, and in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization's Good Clinical Practice guidelines (ICH-GCP), applicable regulatory requirements, and in compliance with the protocol.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and baseline characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics. Categorical variables were summarized with frequency and percentage. Continuous variables were summarized with count, mean, standard deviation, median, minimum and maximum. Response rate was presented as frequency and percentage of patients. Survival analysis was performed to measure lifetime or the amount of time until the occurrence of an event (death in case of overall survival). Survival data was analyzed using a non-parametric procedure performed PROC LIFETEST of SAS (Version 9.4) to measure the duration of time until a specified event occurs. OS was calculated and analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test to estimate the survival function from lifetime data after treatment. The AEs were summarized as frequencies and percentages by type of reactions.

Results

Patients disposition and demographics

Data of 43 patients with gastric (n=39) and GEJ (n=4) adenocarcinomas who were treated with NDLS based chemotherapy regimens was retrospectively analyzed. The baseline characteristics of these patients are summarized in Table I.

Table I.

Patient disposition and baseline characteristics.

| Parameters | All patients (n=43) | Neoadjuvant setting (n=18) | Metastatic setting (n=25) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD, range | 55.14 ±10.7 (34-75) | 54.8±11.4 (34-73) | 55.3±10 (38-75) |

| BSA, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 1.54±0.2 | 1.6±0.2 | 1.54±0.24 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 31 (72.1) | 16 (88.9) | 15 (60) |

| Female | 12 (27.9) | 2 (11.1) | 10 (40) |

| Cancer Stage, n (%) | |||

| II | 6 (14.0) | 6 (33.3) | - |

| III | 10 (23.3) | 10 (55.6) | - |

| IV | 27 (62.8) | 2 (11.1) | 25 (100.0) |

| NDLS dose, n (%) | |||

| 75 mg/m2 | 37 (86.0) | 15 (83.3) | 22 (88.0) |

| 50 mg/m2 | 6 (14.0) | 3 (16.7) | 3 (12.0) |

| Metastasis site, n (%)a | |||

| Lymph node | 10 (23.3) | - | 10 (40.0) |

| Bone | 2 (4.7) | - | 2 (8.0) |

| Liver | 1 (2.3) | 1 (4.0) | |

| Line of therapy, n (%) | |||

| First-line | 38 (88.4) | 18 (100.0) | 20 (80.0) |

| Second-line | 4 (9.3) | - | 4 (16.0) |

| Third-line | 1 (2.3) | - | 1 (4.0) |

| ECOG performance score | |||

| 0 | 3 (7.0) | - | 3 (12.0) |

| 1 | 37 (86.0) | 18 (100.0) | 19 (76.0) |

| 2 | 3 (7.0) | - | 3 (12.0) |

| Comorbid disease, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 13 (30.2) | 2 (11.1) | 11 (44.0) |

| Diabetes | 5 (11.6) | 1 (5.6) | 4 (16.0) |

| Hypothyroidism | 5 (11.6) | 2 (11.1) | 3 (12.0) |

| Others | 3 (7.0) | 3 (16.7) | - |

Of the 43 patients included in this analysis, 39 had gastric cancer and 4 had GEJ. Cancer stage was confirmed by whole body positron emission tomography-computed tomography scan. Other comorbid diseases included asthma, coronary artery disease, thrombophlebitis and dyslipidemia. aMetastasis site was only available for 13 patients. GEJ, gastroesophageal junction; BSA, body surface area; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; NDLS, nanosomal docetaxel lipid suspension; SD, standard deviation.

NDLS was administered as a 1 h infusion in 3 weekly cycles at a dose of 75 mg/m2 (n=37, 86%) and 50 mg/m2 (n=6, 14%). NDLS was used as a first-line therapy in majority (90.7%) of the patients. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (GCSF) was used in majority of the patients (90.7%, 39/43) as primary prophylaxis.

NDLS based treatment regimens.

The most common NDLS based treatment regimen in the neoadjuvant setting was NDLS/oxaliplatin/capecitabine [DOX, 50% (9/18 patients)] followed by NDLS/oxaliplatin/5-FU [DOF, 33.3% (6/18 patients)]. In the metastatic setting, NDLS/cisplatin/5-FU [DCF, 28% (7/25 patients)] followed by DOF (24%, 6/25 patients) were the most commonly used regimens.

Efficacy

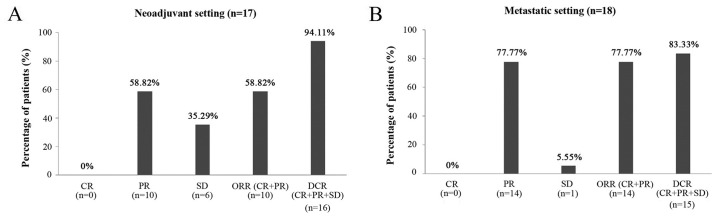

Of 43 patients who received NDLS based chemotherapy for the treatment of gastric and GEJ adenocarcinoma in neoadjuvant and metastatic settings, efficacy evaluation was available for 35 patients (17/18 patients in neoadjuvant and 18/25 patients in metastatic setting). In the neoadjuvant setting, the ORR and DCR were 58.82 and 94.11%, respectively (Fig. 1A) whereas in the metastatic setting, the ORR and DCR were 77.77 and 83.33%, respectively (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Response rate of NDLS based chemotherapy in patients with gastric and gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma in (A) neoadjuvant (n=17) and (B) metastatic (n=18) settings. CR, complete response; DCR, disease control rate; NDLS, nanosomal docetaxel lipid suspension; ORR, overall response rate; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

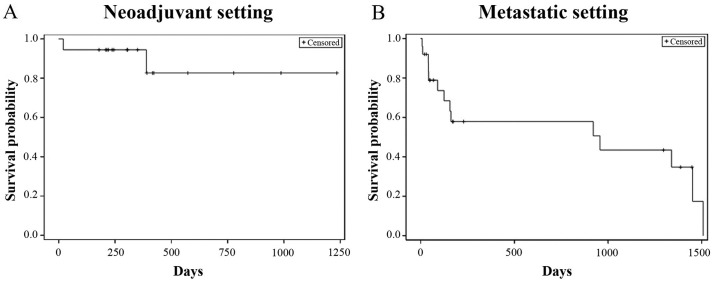

Overall survival

The patient survival data was collected from the date of administration of the first dose of NDLS based therapy till the last follow-up date (September 30, 2018) for alive patients and date of death for patients who died. The proportion of patients who were alive at the last follow-up was 88.9% (16/18) in the neoadjuvant setting and the median OS was not reached (follow-up duration: 0.7-41.2 months) (Fig. 2A). In the metastatic setting, the proportion of patients who were alive at the last follow-up was 56% (14/25) and the median OS was 31.9 months (follow-up duration: 0.2-50.3 months) (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Kaplan Meier estimates of overall survival in patients with gastric and GEJ adenocarcinoma in (A) neoadjuvant (n=18) and (B) metastatic (n=25) settings. GEJ, gastroesophageal junction.

Safety

The data on AEs was available for 33 (76.7%) patients. Of these, at least 1 AE was reported in 72.7% (24/33) patients. Grade 1 AEs were reported in 69.7% (23/33) patients, grade 2 in 30.3% (10/33), grade 3 in 12.1% (4/33) and grade 4 in 9.1% (3/33) patients, respectively. Anemia, lymphopenia thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia were the hematological AEs reported while nausea, vomiting and weakness were the most-common non-hematological AEs reported (Table II).

Table II.

Safety profile of NDLS in patients with gastric and GEJ adenocarcinoma (n=33).

| A, Hematological AEs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse event (>5% patients) | All grades, n (%) | Grade III, n (%) | Grade IV, n (%) |

| Anemia | 18 (54.55) | 1 (1.92) | - |

| Lymphopenia | 7 (21.21) | 2 (3.85) | - |

| Thrombocytopenia | 6 (18.18) | 1 (1.92) | 2 (3.85) |

| Neutropenia | 4 (12.12) | 1 (1.92) | 1 (1.92) |

| B, Non-hematological AEs | |||

| Adverse event (>5% patients) | All grades, n (%) | Grade III, n (%) | Grade IV, n (%) |

| Nausea | 5 (15.15) | - | - |

| Vomiting | 5 (15.15) | - | - |

| Weakness | 5 (15.15) | - | - |

| Hyperglycemia | 4 (12.12) | - | - |

| Anorexia | 3 (9.09) | - | - |

| Diarrhea | 3 (9.09) | - | - |

| Alteration in LFT | 3 (9.09) | 2 (3.85) | - |

| Mouth ulcer | 2 (6.06) | - | - |

| Mucositis | 2 (6.06) | - | - |

| Alopecia | 2 (6.06) | - | - |

AEs in different grades may occur in ≥1 patient; hence, the cumulative number of patients in different grades may exceed the total number of patients with individual AEs. AE, adverse event; GEJ, gastroesophageal; LFT, liver function test; NDLS, nanosomal docetaxel lipid suspension; SD, standard deviation.

Discussion

Addition of docetaxel to the therapeutic armamentarium of gastric and GEJ adenocarcinoma has demonstrated improved treatment outcomes (34). Docetaxel based chemotherapy is recommended as neoadjuvant therapy for gastric cancer. Furthermore, docetaxel as a monotherapy or as combination therapy is recommended for unresectable locally advanced, recurrent or metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma (35). The current study presents the findings of NDLS based chemotherapy in patients with gastric and GEJ cancer in neoadjuvant and metastatic settings.

Neoadjuvant treatment remains the gold standard for the treatment of locally advanced gastric cancer, which aims at ‘downstaging’ the tumor and eliminating the spread of tumor cells or lymph node metastases (36). The available evidence suggests a role for neoadjuvant docetaxel-based chemotherapy in downstaging the cancer, achieving complete surgical resection and probably improving the outcome in patients with locally advanced GAC (37).

An ORR of 44-70% has been reported with docetaxel based regimens in neoadjuvant treatment of gastric cancer (8-10) whereas in our study, NDLS based neoadjuvant chemotherapy demonstrated an ORR of 58.8%. Yahyazadeh-Jabbari et al, evaluated the efficacy and safety of docetaxel/oxaliplatin/capecitabine (DOX) regimen in 49 patients with resectable gastric and GEJ cancers, and reported an ORR of 48.9% (8). Another study by Spigel et al showed an ORR of 61% with DOX regimen in 49 patients with localized carcinoma of the esophagus or gastroesophageal junction (9). In our study, NDLS-based DOX regimen resulted in an ORR of 44.4% (4/9 patients) and a DCR of 88.9% (8/9 patients). The combination of docetaxel/oxaliplatin/5-FU (DOF regimen) as neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the treatment of advanced gastric cancer (n=68) showed an ORR of 70.6% (10). In our study, NDLS based DOF regimen was administered in 6 patients in the neoadjuvant setting and demonstrated an ORR of 66.7% and DCR of 100%. Pathological response and R0 resection are potent surrogate factors for evaluating the efficacy of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (38,39); however, these were not available in the present study, and the results are provided based on RECIST 1.1. In our study, at a follow-up duration ranging from 0.7 to 41.2 months, the median OS was not reached with NDLS based neoadjuvant chemotherapy; and 88.9% patients were alive at the last follow-up.

Docetaxel based regimens have been associated with an ORR of 37-73% in the treatment of metastatic gastric cancer (11,40,41). In our study, NDLS based chemotherapy showed an ORR of 77.77% and a median OS of 31.9 months for patients receiving NDLS based chemotherapy in the metastatic setting. The use of docetaxel for the treatment of metastatic GAC as DCF regimen was approved by the US FDA based on TAX 325 study (n=221), (11) which demonstrated an ORR of 37%, and a median OS of 9.2 months (11). Another study by the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research reported an ORR of 36.6% for DCF regimen in metastatic GAC (median OS: 10.4 months) (40). In our study, patients receiving NDLS based DCF regimen in the metastatic setting reported an ORR of 80% (PR: 80%, 4/5 patients) and a DCR of 100% [PR: 80% (4/5 patients), SD: 20% (1/5 patients)]. In a study by Rosenberg et al, the DOF regimen resulted in an ORR of 73.2% in the treatment of metastatic or unresectable gastric or GEJ adenocarcinoma (median OS: 10.3 months) (41). In our study, NDLS based DOF regimen showed partial response in all 5 patients evaluated in the metastatic setting (ORR: 100%).

Polysorbate 80 and ethanol, which are used as formulation vehicles in the conventional docetaxel formulation, have been implicated in the AEs such as acute hypersensitivity reactions, cumulative fluid retention, peripheral neuropathy (19), severe nonimmunologic anaphylactoid reactions (20), injection-site reactions (21), and alcohol intoxication (22,23). Corticosteroid premedication is generally used with docetaxel based chemotherapy to circumvent the aforementioned AEs, however, these AEs can still be observed despite premedication (24). In our study, AEs like neurotoxicity, fluid retention and acute hypersensitivity reactions were not reported with NDLS based chemotherapy. Anemia, lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia and neutropenia were the hematological AEs whereas nausea, vomiting, weakness and hyperglycemia were the most common (≥10%) non-hematological AEs reported in our study. Anemia (10.2%), nausea (10.2%) and vomiting (6.1%) were the most frequent grade 3/4 AEs with DOX regimen (8). In the study by Spigel et al, the most common (≥5%) grade 3/4 nonhematologic AEs associated with DOX regimen were anorexia (20%), esophagitis (20%), nausea (16%), vomiting (16%), dehydration (16%), pulmonary symptoms (14%), fatigue (12%), dysphagia (10%), diarrhea (8%), hyperglycemia (6%) and sepsis (6%) (9). In the metastatic setting, the grade 3/4 AEs observed with the DCF regimen were: Neutropenia (82%), stomatitis (21%), diarrhea (19%) and lethargy (19%) (11). In a review by Di Cosimo et al, neutropenia was the most common grade 3/4 AE occurring in 50-81% patients with advanced gastric cancer receiving docetaxel based triplet chemotherapy (42). NDLS was mostly used at 75 mg/m2 in our study and was found to be well-tolerated. Severe grade 4 neutropenia and thrombocytopenia were reported in 1.9% and 3.9% patients. The most commonly reported grade 3/4 AEs were lymphopenia (3.9%), anemia, thrombocytopenia and neutropenia (1.9% each).

Corticosteroids premedication is routinely administered in patients receiving conventional docetaxel to mitigate the toxicity issues such as hypersensitivity and fluid retention (43). In a recent study, Obradović et al used transcriptional profiling of tumors and matched metastases in patient-derived xenograft models in mice and suggested the possible role of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) activation resulting in breast cancer progression and metastasis (44). Corticosteroid premedication is not warranted with the NDLS formulation, especially when used as monotherapy, hence, it may potentially help in circumventing the risk of disease progression.

As this is a retrospective data collection study, lack of completeness of data for safety as well as survival data is a major limitation. Also, the details pertaining to tumor size and resectability was not captured in the patient records, hence, could not be presented for patients receiving NDLS in the neoadjuvant setting. The progression-free survival (PFS) could not be captured in this study since, being a real-world study, the data on progression and serial scans were not available for most of the patients at most of the follow-up timepoints.

In conclusion, nanosomal docetaxel lipid suspension (NDLS) based regimens were effective and well-tolerated in managing gastric cancer in neoadjuvant and metastatic settings. This study provides valuable insights into the safety and efficacy of NDLS based chemotherapy in the management of gastric and gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma. A clinical trial is underway to evaluate the safety and efficacy of NDLS based treatment in gastric cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mr. Shreekant Sharma (ISMPP CMPPTM; Intas Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India) for providing writing assistance and Dr Venugopal Madhusudhana (ISMPP CMPPTM; Intas Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India) for additional editorial assistance when developing the manuscript.

Funding

The present study was funded by an unrestricted research grant by Intas Pharmaceuticals Ltd. (Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India), towards statistical analysis and manuscript writing.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

SS, SKDM and GB conducted the research, acquired the data and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. NJ, DB, MAK and IA designed the study, were involved in data interpretation and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors made substantial contributions to this study and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the OM Ethics Committee (Ahmedabad, India). The current study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonization's Good Clinical Practice guidelines and applicable regulatory requirements. Patient consent to review their medical records was not required by the Ethics Committee as NDLS is already approved in India and patient confidentiality was completely maintained. In this retrospective study, no patient identifiers were used and data were anonymized.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Drs. Mujtaba A. Khan, Deepak Bunger and Nisarg Joshi are employees of Intas Pharmaceutical Ltd., India. Dr Imran Ahmad is an employee of Jina Pharmaceutical Inc., USA.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunt N, McHale S. The psychological impact of alopecia. BMJ. 2005;331:951–953. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7522.951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ajani JA, Lee J, Sano T, Janjigian YY, Fan D, Song S. Gastric adenocarcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3(17036) doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lerut T: Carcinoma of the esophagus and gastro-esophageal junction. In: Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem-Oriented. Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA (eds). Zuckschwerdt, Munich, 2001. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK6982/. Accessed March 20, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gee DW, Rattner DW. Management of gastroesophageal tumors. Oncologist. 2007;12:175–185. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-2-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakamoto J, Matsui T, Kodera Y. Paclitaxel chemotherapy for the treatment of gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2009;12:69–78. doi: 10.1007/s10120-009-0505-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bang YJ, Kang WK, Kang YK, Kim HC, Jacques C, Zuber E, Daglish B, Boudraa Y, Kim WS, Heo DS, Kim NK. Docetaxel 75mg/m(2) is active and well tolerated in patients with metastatic or recurrent gastric cancer: A phase II trial. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2002;32:248–254. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyf057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yahyazadeh-Jabbari SH, Malekpour N, Salmanian B, Foodazi H, Salehi M, Noorizadeh F. The phase 2 study of ‘(TOX) preoperative chemotherapy’ response rate and side effects in [Locally Advanced Operable Gastric Adenocarcinoma] patients with docetaxel, oxaliplatin and capcitabine. Iran J Cancer Prev. 2013;6:133–140. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spigel DR, Greco FA, Meluch AA, Lane CM, Farley C, Gray JR, Clark BL, Burris HA III, Hainsworth JD. Phase I/II trial of preoperative oxaliplatin, docetaxel, and capecitabine with concurrent radiation therapy in localized carcinoma of the esophagus or gastroesophageal junction. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2213–2219. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.8773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhen Y, Xu Z, Sun Y, Guo H, Gong W, Chai J, Li Z. DOF as neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the treatment of advanced gastric cancer. Chin J Clin Oncol. 2011;38:564–567. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Cutsem E, Moiseyenko VM, Tjulandin S, Majlis A, Constenla M, Boni C, Rodrigues A, Fodor M, Chao Y, Voznyi E, et al. Phase III study of docetaxel and cisplatin plus fluorouracil compared with cisplatin and fluorouracil as first-line therapy for advanced gastric cancer: A report of the V325 study group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4991–4997. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishiyama M, Wada S. Docetaxel: Its role in current and future treatments for advanced gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2009;12:132–141. doi: 10.1007/s10120-009-0521-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Einzig AI, Neuberg D, Remick SC, Karp DD, O'Dwyer PJ, Stewart JA, Benson AB III. Phase II trial of docetaxel (Taxotere) in patients with adenocarcinoma of the upper gastrointestinal tract previously untreated with cytotoxic chemotherapy: The eastern cooperative oncology group (ECOG) results of protocol E1293. Med Oncol. 1996;13:87–93. doi: 10.1007/BF02993858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ridwelski K, Gebauer T, Fahlke J, Kroning H, Kettner E, Meyer F, Eichelmann K, Lippert H. Combination chemotherapy with docetaxel and cisplatin for locally advanced and metastatic gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:47–51. doi: 10.1023/a:1008328501128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Constenla M, Garcia-Arroyo R, Lorenzo I, Carrete N, Campos B, Palacios P. Docetaxel, 5-fluorouracil, and leucovorin as treatment for advanced gastric cancer: Results of a phase II study. Gastric Cancer. 2002;5:142–147. doi: 10.1007/s101200200025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roy A, Cunningham D, Hawkins R, Sörbye H, Adenis A, Barcelo JR, Lopez-Vivanco G, Adler G, Canon JL, Lofts F, et al. Docetaxel combined with irinotecan or 5-fluorouracil in patients with advanced oesophago-gastric cancer: A randomised phase II study. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:435–441. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurt E, Cubukcu E, Karabulut B, Olmez OF, Kurt M, Avci N, Ozdemir F, Tunali D, Evrensel T, Manavoglu O. A multi-institutional evaluation of carboplatin plus docetaxel regimen in elderly patients with advanced gastric cancer. J BUON. 2013;18:147–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thuss-Patience PC, Kretzschmar A, Dogan Y, Rothmann F, Blau I, Schwaner I, Breithaupt K, Bichev D, Grothoff M, Grieser C, Reichardt P. Docetaxel and capecitabine for advanced gastric cancer: Investigating dose-dependent efficacy in two patient cohorts. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:505–512. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ten Tije AJ, Verweij J, Loos WJ, Sparreboom A. Pharmacological effects of formulation vehicles: Implications for cancer chemotherapy. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42:665–685. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200342070-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coors EA, Seybold H, Merk HF, Mahler V. Polysorbate 80 in medical products and nonimmunologic anaphylactoid reactions. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005;95:593–599. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwartzberg LS, Navari RM. Safety of polysorbate 80 in the oncology setting. Adv Ther. 2018;35:754–767. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0707-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. FDA Drug Safety Communication (2014, June 20). FDA warns that cancer drug docetaxel may cause symptoms of alcohol intoxication after treatment. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm401752.htm. Accessed March 20, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mirza A, Mithal N. Alcohol intoxication with the new formulation of docetaxel. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2011;23:560–561. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho MY, Mackey JR. Presentation and management of docetaxel-related adverse effects in patients with breast cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 2014;6:253–259. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S40601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmad A, Sheikh S, Ali SM, Ahmad MU, Paithankar M, Saptarishi D, Maheshwari K, Kumar K, Singh J, Patel G. Development of aqueous based formulation of docetaxel: Safety and pharmacokinetics in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Nanomed Nanotechnol. 2015;6(1) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis LD, Miller AA, Rosner GL, Dowell JE, Valdivieso M, Relling MV, Egorin MJ, Bies RR, Hollis DR, Levine EG, et al. A comparison of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of docetaxel between African-American and Caucasian cancer patients: CALGB 9871. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3302–3311. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmad A, Sheikh S, Taran R, Srivastav SP, Prasad K, Rajappa SJ, Kumar V, Gopichand M, Paithankar M, Sharma M, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of a novel nanosomal docetaxel lipid suspension compared with taxotere in locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer patients. Clin Breast Cancer. 2014;14:177–181. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ashraf M, Sajjad R, Khan M, Shah M, Bhat Y, Wani Z. 156P Efficacy and safety of a novel nanosomal docetaxel lipid suspension (NDLS) as an anti cancer agent-a retrospective study. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:ix46–ix51. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naik R, Khan MA. Doceaqualip in a patient with prostate cancer who had an allergic reaction to conventional docetaxel: A case report. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;6:341–343. doi: 10.3892/mco.2017.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prasanna R, Bunger D, Khan MA. Efficacy and safety of DoceAqualip in a patient with locally advanced cervical cancer: A case report. Mol Clin Oncol. 2018;8:296–299. doi: 10.3892/mco.2017.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vyas V, Joshi N, Khan M. Novel docetaxel formulation (NDLS) in low cardiac reserve ovarian cancer. Open Access J Cancer Oncol. 2018;2(000122) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gupta S, Pawar SS, Bunger D. Successful downstaging of locally recurrent penile squamous cell carcinoma with neoadjuvant nanosomal docetaxel lipid suspension (NDLS) based regimen followed by curative surgery. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017(bcr2017220686) doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-220686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tetzlaff ED, Cheng JD, Ajani JA. Review of docetaxel in the treatment of gastric cancer. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4:999–1007. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®). Gastric Cancer. Version 1.2019-March 14, 2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/gastric.pdf. July 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Menges M, Hoehler T. Neoadjuvant therapy of gastric cancer: A decisive step forward. Gastrointest Tumors. 2014;1:99–104. doi: 10.1159/000362577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Inno A, Basso M, Cassano A and Barone C: A review of docetaxel: Its use in the treatment of gastric cancer. Clin Med Insights 2: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.4137/CMT.S5191. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pauligk C, Tannapfel A, Meiler J, Luley KB, Kopp HG, Homann N, Hofheinz RD, Schmalenberg H, Probst S, Haag GM, et al. Pathological response to neoadjuvant 5-FU, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel (FLOT) versus epirubicin, cisplatin, and 5-FU (ECF) in patients with locally advanced, resectable gastric/esophagogastric junction (EGJ) cancer: Data from the phase II part of the FLOT4 phase III study of the AIO. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:4016–4016. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu SB, Liu CH, Wang X, Dong YW, Zhao L, Liu HF, Cao Y, Zhong DR, Liu W, Li YL, et al. Pathological evaluation of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2019;17(3) doi: 10.1186/s12957-018-1534-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roth AD, Fazio N, Stupp R, Falk S, Bernhard J, Saletti P, Koberle D, Borner MM, Rufibach K, Maibach R, et al. Docetaxel, cisplatin, and fluorouracil; docetaxel and cisplatin; and epirubicin, cisplatin, and fluorouracil as systemic treatment for advanced gastric carcinoma: A randomized phase II trial of the Swiss group for clinical cancer research. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3217–3223. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenberg AJ, Rademaker A, Hochster HS, Ryan T, Hensing T, Shankaran V, Baddi L, Mahalingam D, Mulcahy MF, Benson AB III. Docetaxel, oxaliplatin, and 5-fluorouracil (DOF) in metastatic and unresectable gastric/gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma: A phase II study with long-term follow-up. Oncologist. 2019;24:1039–e642. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Di Cosimo S, Ferretti G, Fazio N, Silvestris N, Carlini P, Alimonti A, Gelibter A, Felici A, Papaldo P, Cognetti F. Docetaxel in advanced gastric cancer-review of the main clinical trials. Acta Oncol. 2003;42:693–700. doi: 10.1080/02841860310011014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weiss RB, Donehower RC, Wiernik PH, Ohnuma T, Gralla RJ, Trump DL, Baker JR Jr, Van Echo DA, Von Hoff DD, Leyland-Jones B. Hypersensitivity reactions from taxol. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:1263–1268. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.7.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Obradović MMS, Hamelin B, Manevski N, Couto JP, Sethi A, Coissieux MM, Münst S, Okamoto R, Kohler H, Schmidt A, Bentires-Alj M. Glucocorticoids promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2019;567:540–544. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.