Abstract

In this study, a systematic search for structures of carbon crystals under high pressure was performed by using the artificial force induced reaction method including periodic boundary conditions. To perform a search under an arbitrary pressure, an algorithm to take account of the pressure was implemented in the GRRM program. At 100 GPa, the search generated 710 unique structures automatically. These structures were compared with 982 structures obtained by the search under zero pressure. The structures at 100 GPa were much denser than those under zero pressure. Besides, new structures that were denser than diamond were obtained at 100 GPa.

1. Introduction

Properties of crystalline materials depend not only on their compositions but also on their crystal structures. Different crystal structures can be produced by changing their generation conditions. Under high pressure, there are cases where structures that are not very stable under ambient pressure can be formed. Therefore, crystals formed under high pressures can exhibit properties that are not seen in structures formed under ordinary pressures.1,2

For example, graphite is the most stable structure of the carbon crystal at ordinary temperatures and pressures, while diamond, another carbon crystal structure, is formed at the mantle of the earth where the pressure is much higher than that on the surface. In addition to these two, various carbon crystal structures have been discovered either experimentally or theoretically.3,4 Especially, Cco-C8 (or Z-carbon),5,6M-carbon,7 and bc88 have been reported as stable crystal structures under high pressures.

To compute a property of a crystal, one must identify its structure first. Therefore, methods that can predict crystal structures under arbitrary pressures are required. Such a computational method is particularly useful when conditions that are difficult to realize in a laboratory is considered. In this context, the first-principles crystal structure prediction has been one of the active fields. To date, various methods have been developed and successfully applied to various systems.9−14 Recently, we developed the PBC/SC-AFIR method15 by combining the single-component artificial force induced reaction (SC-AFIR) method16−19 and periodic boundary conditions (PBCs). The PBC/SC-AFIR method enables a systematic, unbiased search for stable crystal structures without requiring any previous knowledge.

In this study, a systematic search for crystal structures under high pressure was performed for the C8 unit cell by the PBC/SC-AFIR method. The previous version was able to conduct searches only under zero pressure. In this study, we have newly implemented an algorithm to explore crystal structures under arbitrary pressures. The PBC/SC-AFIR search at 100 GPa generated 710 crystal structures automatically. Furthermore, several structures that exhibited higher density than diamond were discovered as high-lying structures. We also performed a PBC/SC-AFIR search at zero pressure as a reference and compared the two results.

2. Results and Discussion

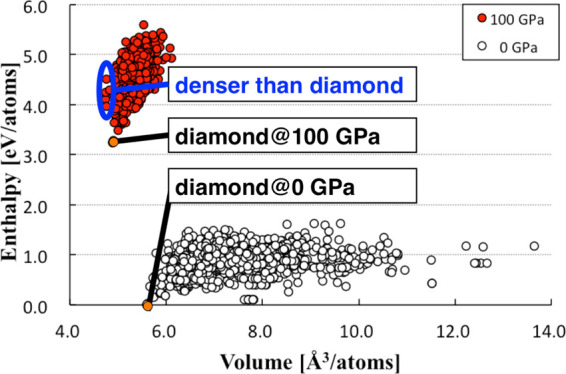

By the PBC/SC-AFIR method, 982 and 710 carbon crystal structures were generated under 0 and 100 GPa, respectively. The enthalpy distribution of the obtained structures with respect to volume is shown in Figure 1. The most stable 10 structures under each pressure are shown in Figures 2 and 3, where the nth lowest crystal structure under p GPa is labeled as MINnpGPa.

Figure 1.

Enthalpy distribution of the obtained structures with respect to volume for 0 (○) and 100 GPa (●).

Figure 2.

Ten most stable carbon crystal structures under 0 GPa. The names of the structures, space groups, relative enthalpies, and volume are shown in the labels. Translation vectors (TVs) are shown as red, green, and blue lines. Atoms in a unit cell are highlighted by the ball model.

Figure 3.

Ten most stable carbon crystal structures under 100 GPa. The names of structures, space groups, relative enthalpies, and volume are shown in the labels. The reference of enthalpy is diamond under 0 GPa. TVs are shown as red, green, and blue lines. Atoms in a unit cell are highlighted by the ball model.

In the case of 0 GPa, the volume of the structures was widely distributed from 5.593 to 13.641 Å3/atoms, as seen in Figure 1. The most stable regions are the diamond region (around 5.593 Å3/atoms) and graphite region (around 7.755 Å3/atoms). In this calculation level, diamond is a little more stable than graphite because of the computational error. The error is small as the energy gap between graphite and diamond is only 0.13 eV/atoms even in more reliable density functional theory (DFT) result.20,21 Taking the small computational error into account, we do not discuss small energy differences among obtained structures. Instead, we discuss variations of structural trends caused by the large pressure change (0–100 GPa).

At 0 GPa, diamond (MIN00GPa, #1 in SACADA4), 12R-diamond22 (MIN10GPa, #209 in SACADA4), and lonsdaleite (MIN20GPa, #37 in SACADA4) were found as structures with low volume. Graphite with different stacking patterns was obtained as MIN30GPa–MIN100GPa with a volume of ∼7.8 Å3/atoms, where these eight can be classified into A–B and A–B–C stacking types but differ slightly to each other probably because of computational errors arisen from differences in representations of cells. Cco-C8 (or Z-carbon)5,6 (MIN110GPa, #141 in SACADA4), oC1623 (MIN120GPa, #210 in SACADA4), M-carbon7 (MIN130GPa, #224 in SACADA4), F-carbon24−30 (MIN140GPa, #225 in SACADA4), and 8-tetra(2,2) tubulane (or bct-C4)31−39 (MIN150GPa, #60 in SACADA4) were also obtained as low energy structures. The results of the search at 0 GPa well correspond to our previous results reported in ref (15). The search generated almost all structures registered in SACADA4 in 2017 that can be represented by C8 unit cells. Furthermore, as reported in ref (15), the search discovered many new crystal structures that were not registered in SACADA in 2017. One exception was 4H-diamond,41,44 and both present and previous searches did not find this structure. This is because our algorithm restricts the search to areas in which the shape of the cell is not very far from cubic. 4H-diamond has an elongated cell that is far from cubic structures and is located at the boundary where the restriction comes effective. In addition, structures that cannot be written in a C8 unit cell, such as T1227,42 and W-carbon,43 were not obtained in the present search.

In the case of 100 GPa, compact structures were obtained as low energy ones. The volume of obtained structures distributed from 4.746 to 6.115 Å3/atoms is shown in Figure 1. Structures with small volumes were relatively stable because of the PV term in the enthalpy. At 100 GPa, two diamond structures described by different unit cells (MIN0100GPa and MIN1100GPa, #1 in SACADA4) were the most stable, where these two are structurally almost identical but differ slightly in energy (∼0.059 eV/unit-cell) probably because of computational errors arisen from differences in representations of cells. 4H-diamond41,44 (MIN2100GPa, #111 in SACADA4), 12R-diamond22 (MIN3100GPa, #209 in SACADA4), and lonsdaleite (MIN4100GPa, #37 in SACADA4) were also obtained. Cco-C8 (or Z-carbon)5,6 (MIN5100GPa, #141 in SACADA4), M-carbon7 (MIN6100GPa, #224 in SACADA4), F-carbon24−30 (MIN7100GPa, #225 in SACADA4), oC1623 (MIN8100GPa, #210 in SACADA4), and C2/m-1640 (MIN9100GPa, #186 in SACADA4) were also found in the lower energy region. Compared to the results of 0 GPa, all structures except for 4H-diamond (MIN2100GPa) and C2/m-16 (MIN9100GPa) are also seen in Figure 2. Although 4H-diamond is one of stable structures at 0 GPa, it was excluded from our search objective because of our computational setting avoiding cells that are elongated toward one direction as discussed above. On the other hand, C2/m-16 was found also in the search at 0 GPa as MIN160GPa.

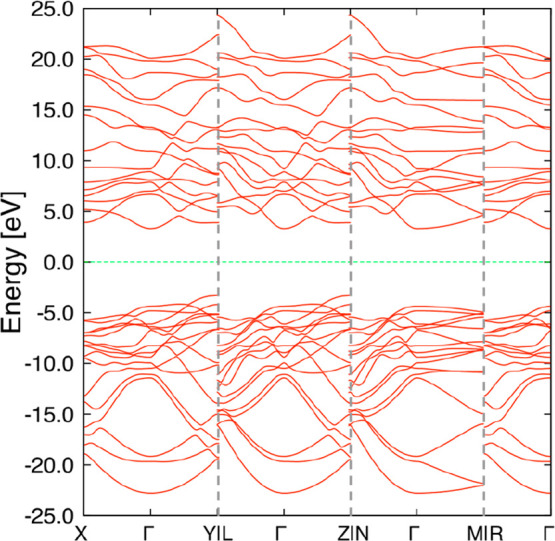

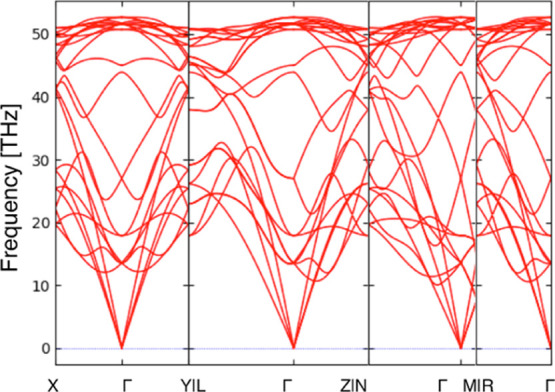

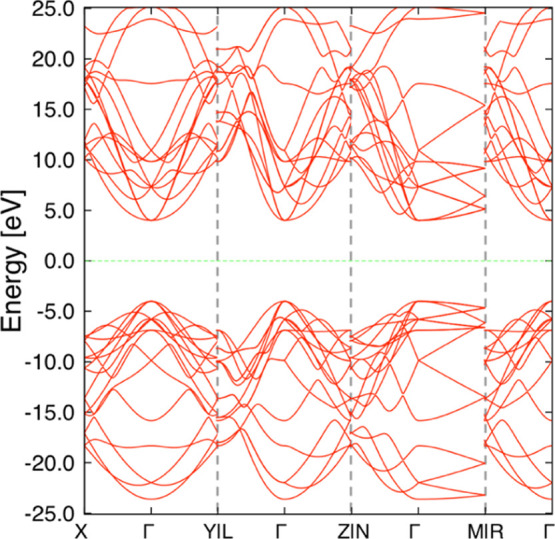

At 0 GPa, diamond showed the smallest volume. In contrast, under 100 GPa, four types of structures exhibited smaller volume than diamond. The volume and enthalpy of these structures are shown in Table 1. Among them, MIN70100GPa is known as r842,45 (#122 in SACADA4), and MIN38100GPa is known as bc88 (#20 in SACADA4), as reported in the literature. To the best of our knowledge, the other structures have not been reported. Their structures are shown in various ways in Figure 4. MIN99100GPa showed the smallest volume among all obtained structures. The phonon dispersion shows that MIN99100GPa is a local minimum structure (Figure 5). The space group of this structure is I212121. This structure is composed only of sp3 carbons and has five-membered rings. The band structure shown in Figure 6 suggests that this structure is an insulator with a band gap of 6.6 eV. Another new structure is MIN227100GPa. The phonon dispersion shows that MIN227100GPa is a local minimum structure (Figure 7). This structure has a little larger volume than bc8 but has a smaller volume than diamond. The space group of this structure is F222. This structure is also composed only of sp3 carbon and has some distorted sp3 carbon; one of the C–C–C angles is 134.0°. The band structure shown in Figure 8 suggests that this structure is also an insulator with a band gap of 8.0 eV. These structures are less stable than diamond at 100 GPa, and MIN99100GPa was found to become more stable than diamond only at a pressure of 2.4 TPa or higher at the present computational level. Interestingly, both of the new structures MIN99100GPa and MIN227100GPa have known topologies, 4,4,4T4715-HZ and 4,4,4,4,4T248559-HZ, respectively, for hypothetical zeolites.46

Table 1. Volume, Enthalpy, and Space Group of Structures of Six Smallest Volumes.

| volume [Å3/atoms] | enthalpy [eV/atoms] | space group | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MIN99100GPa | 4.746 | 4.25 | I212121 |

| MIN70100GPa (r8) | 4.751 | 4.11 | R3̅ |

| MIN38100GPa (bc8) | 4.753 | 3.97 | Ia3 |

| MIN227100GPa | 4.762 | 4.51 | F222 |

| MIN0100GPa (diamond) | 4.896 | 3.24 | Fd3̅m |

Figure 4.

Views along the a axis (a), b axis (b), and c axis (c) and the unit cell (d) of MIN99100GPa and MIN227100GPa. TVs are shown as red, green, and blue lines.

Figure 5.

Phonon dispersion of MIN99100GPa.

Figure 6.

Band structure of MIN99100GPa. The Fermi level is shown by a green line.

Figure 7.

Phonon dispersion of MIN227100GPa.

Figure 8.

Band structure of MIN227100GPa. The Fermi level is shown by a green line.

In this study, we performed a global search in which very high energy structures such as MIN227100GPa were also targeted and demonstrated that the present method can predict unknown structures even for carbon for which numerous precedent studies exist. Such an exhaustive search requires huge computational costs even for small unit cells, and its application to systems of much larger cells is not straightforward. On the other hand, various options are available in the SC-AFIR method: limiting structural patterns, energy ranges, barrier ranges, and so forth.19 By using these options, larger unit cells could be adopted. In the future, such applications will be incorporated to systems for which even low-lying structures are unknown.

3. Conclusions

In this study, the PBC/SC-AFIR method was applied to the enthalpy (E + PV) surface to explore crystal structures under an arbitrary pressure. This approach was applied to the carbon crystal described by the C8 unit cell. The search automatically generated known low-lying structures. Furthermore, many new structures were discovered by the search. Under 100 GPa, four structures that were denser than diamond were obtained. Two among the four corresponded to the previously reported r8 and bc8 structure. The other two were new structures that have never been reported in the literature.

The present results suggest that the PBC/SC-AFIR method is effective for prediction of crystal structures under high pressures. This method would be particularly useful to consider conditions that are not easily reproducible in a laboratory. Hence, further studies on crystal structures of various compositions under high pressures are under progress.

4. Computational Method

A systematic search for crystal structures under high pressure was performed for the cells containing eight carbon atoms in the unit cell (C8 unit cell) by the PBC/SC-AFIR method. The SC-AFIR method systematically defines fragments composed of one or more atoms in a given structure and induces structural deformations by pushing them together or pulling them apart. In addition, the PBC/SC-AFIR method induces deformations in the shape of the unit cell by applying an artificial force to the dummy atom set at the tips of translation vectors (TVs) and the origin. The user can set the value of model collision energy parameter γ, an approximate upper limit of the barrier height which the search overcomes. In this study, γ is set to a very large value, 1000.0 kJ/mol, to find structures in a wide energy range. The structural deformations are applied systematically to local minima (MINs) obtained during the search. Because applying the procedure to all MINs is demanding, MINs to which the procedure is applied are chosen stochastically based on their energy. In this study, to explore a wide variety of structures, the model temperature parameter TR which determines how frequently high-energy MINs are chosen is set to a large value 10,000.0 K. The calculation is terminated when the last N structural deformation procedures do not update the set of lowest M MINs. Here, M and N are set as f and 3f, respectively, where f is the number of internal degrees of freedom. Further details are described in our previous paper.15

At zero pressure, the surface of electronic energy E is explored. In this study, the surfaces of E + PV is considered instead, where P is the constant pressure, V (=det h) is the unit cell volume, and h is the unit cell. The quantity E + PV is often referred as enthalpy because it corresponds to the enthalpy when vibrational, rotational, and translational contributions are neglected, and crystal structures under high pressures have been studied through geometry optimizations based on the E + PV surface.47−49E + PV also corresponds to the negative value of the Lagrangian for constant pressure molecular dynamic simulations50 in the limit of zero kinetic energy. The value and gradient of E are computed by the DFTB+ code,51,52 where the SCC-DFTB method of the DFTB3 model, the pbc-0-3 parameter,53 the D3 dispersion correction,54 the electronic temperature of 100.0 K, and the 4 × 4 × 4 Monkhorst–Pack sampling are adopted. The value and gradient of V are computed analytically using our own script and added to those for E obtained by the DFTB+ code. The automated search based on the enthalpy and its gradient is performed by the PBC/SC-AFIR method implemented in a developer version of the GRRM program.55 Spglib-1.8.3 was used to determine the space group of the obtained crystal structures.56 Phonopy-1.10.8 was used to calculate the phonon dispersion.57,58 The k paths were determined according to the method previously described in the literature.59 The topological type of new crystal structures was determined by using TopCryst.60

Acknowledgments

M.T. was supported by JSPS-DC2, JSPS-PD, and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology through the Program for Leading Graduate Schools (Hokkaido University “Ambitious Leader’s Program”). This work was supported by JST-CREST (no. JPMJCR14L5), JST-ERATO (no. JPMJER1903), and JSPS-WPI.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c01709.

Low-lying structures and structures denser than diamond in the Cartesian format (PDF)

Author Present Address

⊥ Graduate School of Nanobioscience, Yokohama City University, Seto 22-2, Kanazawa-ku, Yokohama, Kanagawa 236-0027, Japan.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Grochala W.; Hoffmann R.; Feng J.; Ashcroft N. W. The Chemical Imagination at Work in Very Tight Places. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 3620–3642. 10.1002/anie.200602485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao H.-K.; Chen X.-J.; Ding Y.; Li B.; Wang L. Solids, liquids, and gases under high pressure. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2018, 90, 015007. 10.1103/revmodphys.90.015007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Georgakilas V.; Perman J. A.; Tucek J.; Zboril R. Broad Family of Carbon Nanoallotropes: Classification, Chemistry, and Applications of Fullerenes, Carbon Dots, Nanotubes, Graphene, Nanodiamonds, and Combined Superstructures. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 4744–4822. 10.1021/cr500304f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann R.; Kabanov A. A.; Golov A. A.; Proserpio D. M. Homo Citans and Carbon Allotropes: For an Ethics of Citation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 10962–10976. 10.1002/anie.201600655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z.; Xu B.; Zhou X.-F.; Wang L.-M.; Wen B.; He J.; Liu Z.; Wang H.-T.; Tian Y. Novel Superhard Carbon: C-Centered Orthorhombic C8. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 215502. 10.1103/physrevlett.107.215502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amsler M.; Flores-Livas J. A.; Lehtovaara L.; Balima F.; Ghasemi S. A.; Machon D.; Pailhes S.; Willand A.; Caliste D.; Botti S.; San Miguel A.; Goedecker S.; Marques M. A. L. Crystal Structure of Cold Compressed Graphite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 065501. 10.1103/physrevlett.108.065501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oganov A. R.; Glass C. W. Crystal structure prediction using ab initio evolutionary techniques: Principles and applications. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 124, 244704. 10.1063/1.2210932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahy S.; Louie S. G. High-pressure structural and electronic properties of carbon. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 1987, 36, 3373–3385. 10.1103/physrevb.36.3373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wales D. J.; Scheraga H. A. Global optimization of clusters, crystals, and biomolecules. Science 1999, 285, 1368–1372. 10.1126/science.285.5432.1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oganov A. R.Modern Methods of Crystal Structure Prediction; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pickard C. J.; Needs R. J. Ab initio random structure searching. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2011, 23, 053201. 10.1088/0953-8984/23/5/053201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson K. Model predicts structure of crystals. Nature 2007, 450, 771. 10.1038/450771a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurek E.; Grochala W. Predicting crystal structures and properties of matter under extreme conditions via quantum mechanics: the pressure is on. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 2917–2934. 10.1039/c4cp04445b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery P.; Wang X.; Oses C.; Gossett E.; Proserpio D. M.; Toher C.; Curtarolo S.; Zurek E. Predicting superhard materials via a machine learning informed evolutionary structure search. npj Comput. Mater. 2019, 5, 89. 10.1038/s41524-019-0226-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi M.; Taketsugu T.; Kino H.; Tateyama Y.; Terakura K.; Maeda S. Global search for low-lying crystal structures using the artificial force induced reaction method: A case study on carbon. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 95, 184110. 10.1103/physrevb.95.184110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda S.; Taketsugu T.; Morokuma K. Exploring Transition State Structures for Intramolecular Pathways by the Artificial Force Induced Reaction Method. J. Comput. Chem. 2014, 35, 166–173. 10.1002/jcc.23481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda S.; Ohno K.; Morokuma K. Systematic exploration of the mechanism of chemical reactions: the global reaction route mapping (GRRM) strategy using the ADDF and AFIR methods. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 3683–3701. 10.1039/c3cp44063j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda S.; Harabuchi Y.; Takagi M.; Taketsugu T.; Morokuma K. Artificial Force Induced Reaction (AFIR) Method for Exploring Quantum Chemical Potential Energy Surfaces. Chem. Rec. 2016, 16, 2232–2248. 10.1002/tcr.201600043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda S.; Harabuchi Y.; Takagi M.; Saita K.; Suzuki K.; Ichino T.; Sumiya Y.; Sugiyama K.; Ono Y. Implementation and performance of the artificial force induced reaction method in the GRRM17 program. J. Comput. Chem. 2018, 39, 233–251. 10.1002/jcc.25106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bučko T.; Hafner J.; Lebègue S.; Ángyán J. G. Improved Description of the Structure of Molecular and Layered Crystals: Ab Initio DFT Calculations with van der Waals Corrections. J. Phys. Chem. A 2010, 114, 11814–11824. 10.1021/jp106469x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grochala W. Diamond: Electronic Ground State of Carbon at Temperatures Approaching 0 K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 3680–3683. 10.1002/anie.201400131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.-T.; Chen C.; Kawazoe Y. Mechanism for direct conversion of graphite to diamond. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2011, 84, 012102. 10.1103/physrevb.84.012102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M.; Ma M.; Zhao Z.; Yu D.; He J. Superhard sp2-sp3 hybrid carbon allotropes with tunable electronic properties. AIP Adv. 2016, 6, 055020. 10.1063/1.4952426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niu H.; Chen X.-Q.; Wang S.; Li D.; Mao W. L.; Li Y.. Families of superhard crystalline carbon allotropes induced via cold-compressed graphite and nanotubes. 2012, arXiv:1203.2998. arXiv preprint. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian F.; Dong X.; Zhao Z.; He J.; Wang H.-T. Superhard F-carbon predicted by ab initio particle-swarm optimization methodology. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2012, 24, 165504. 10.1088/0953-8984/24/16/165504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.-T.; Chen C.; Kawazoe Y. Phase conversion from graphite toward a simple monoclinic sp3-carbon allotrope. J. Chem. Phys. 2012, 137, 024502. 10.1063/1.4732538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z.; Tian F.; Dong X.; Li Q.; Wang Q.; Wang H.; Zhong X.; Xu B.; Yu D.; He J.; Wang H.-T.; Ma Y.; Tian Y. Tetragonal allotrope of group 14 elements. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 12362–12365. 10.1021/ja304380p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou R.; Zeng X. C. Polymorphic phases of sp3-hybridized carbon under cold compression. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 7530–7538. 10.1021/ja301582d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amsler M.; Flores-Livas J. A.; Marques M. A.; Botti S.; Goedecker S. Prediction of a novel monoclinic carbon allotrope. Eur. Phys. J. B 2013, 86, 383. 10.1140/epjb/e2013-40639-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W.-F.; Wang L.-S.; Li Z.-P.; Xia M.-R.; Gao F.-M. Ultra-Hard Bonds in P -Carbon Stronger than Diamond. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2015, 32, 096201. 10.1088/0256-307x/32/9/096201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baughman R. H.; Galvão D. S. Tubulanes: carbon phases based on cross-linked fullerene tubules. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1993, 211, 110–118. 10.1016/0009-2614(93)80059-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baughman R. H.; Liu A. Y.; Cui C.; Schields P. J. A carbon phase that graphitizes at room temperature. Synth. Met. 1997, 86, 2371–2374. 10.1016/s0379-6779(97)81165-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz P. A.; Leung K.; Stechel E. B. Small rings and amorphous tetrahedral carbon. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 1999, 59, 733–741. 10.1103/physrevb.59.733. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Badding J. V.; Scheidemantel T. J. FLAPW investigation of the stability and equation of state of rectangulated carbon. Solid State Commun. 2002, 122, 473–477. 10.1016/s0038-1098(02)00136-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Domingos H. S. Carbon allotropes and strong nanotube bundles. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2004, 16, 9083–9091. 10.1088/0953-8984/16/49/023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strong R. T.; Pickard C. J.; Milman V.; Thimm G.; Winkler B. Systematic prediction of crystal structures: An application to sp3-hybridized carbon polymorphs. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2004, 70, 045101. 10.1103/physrevb.70.045101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umemoto K.; Wentzcovitch R. M.; Saito S.; Miyake T. Body-Centered Tetragonal C4: A Viable sp3 Carbon Allotrope. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 125504. 10.1103/physrevlett.104.125504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X.-F.; Qian G.-R.; Dong X.; Zhang L.; Tian Y.; Wang H.-T. Ab initio study of the formation of transparent carbon under pressure. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2010, 82, 134126. 10.1103/physrevb.82.134126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z.; Xu B.; Wang L.-M.; Zhou X.-F.; He J.; Liu Z.; Wang H.-T.; Tian Y. Three Dimensional Carbon-Nanotube Polymers. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 7226–7234. 10.1021/nn202053t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öhrström L.; O’Keeffe M. Network topology approach to new allotropes of the group 14 elements. Z. Kristallogr.—Cryst. Mater. 2013, 228, 343–346. 10.1524/zkri.2013.1620. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M.; Huang Q.; Zhao Z.; Xu B.; Yu D.; He J. Superhard and high-strength yne-diamond semimetals. Diamond Relat. Mater. 2014, 46, 15–20. 10.1016/j.diamond.2014.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mujica A.; Pickard C. J.; Needs R. J. Low-energy tetrahedral polymorphs of carbon, silicon, and germanium. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2015, 91, 214104. 10.1103/physrevb.91.214104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.-T.; Chen C.; Kawazoe Y. Low-Temperature Phase Transformation from Graphite to sp3 Orthorhombic Carbon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 075501. 10.1103/physrevlett.106.075501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Wang Y.; Lv J.; Zhu C.; Li Q.; Zhang M.; Li Q.; Ma Y. First-principles structural design of superhard materials. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 138, 114101. 10.1063/1.4794424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.-Z.; Wang J.-T.; Xu L.-F.; Chen C. Ab initio prediction of superdense tetragonal and monoclinic polymorphs of carbon. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 94, 174102. 10.1103/physrevb.94.174102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blatov V. A.; Blatova O. A.; Daeyaert F.; Deem M. W. Nanoporous materials with predicted zeolite topologies. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 17760–17767. 10.1039/d0ra01888k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas R.; Martin R. M.; Needs R. J.; Nielsen O. H. Complex tetrahedral structures of silicon and carbon under pressure. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 1984, 30, 3210–3213. 10.1103/physrevb.30.3210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dzyabchenko A. V. Theoretical structures for crystalline benzene. Part 5. Static equilibrium at negative pressures. J. Struct. Chem. 1986, 27, 412–418. 10.1007/bf00751821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teter D. M.; Hemley R. J.; Kresse G.; Hafner J. High pressure polymorphism in silica. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 80, 2145–2148. 10.1103/physrevlett.80.2145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parrinello M.; Rahman A. Crystal structure and pair potentials: A molecular-dynamics study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1980, 45, 1196–1199. 10.1103/physrevlett.45.1196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elstner M.; Porezag D.; Jungnickel G.; Elsner J.; Haugk M.; Frauenheim T.; Suhai S.; Seifert G. Self-consistent-charge density-functional tight-binding method for simulations of complex materials properties. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 1998, 58, 7260–7268. 10.1103/physrevb.58.7260. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aradi B.; Hourahine B.; Frauenheim T. DFTB+, a sparse matrix-based implementation of the DFTB method. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111, 5678–5684. 10.1021/jp070186p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler C.; Frauenheim T. Molecular dynamics simulations of CFx (x=2,3) molecules at Si3N4 and SiO2 surfaces. Surf. Sci. 2006, 600, 453–460. 10.1016/j.susc.2005.10.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 2006, 27, 1787–1799. 10.1002/jcc.20495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda S.; Harabuchi Y.; Sumiya Y.; Takagi M.; Suzuki K.; Sugiyama K.; Ono Y.; Hatanaka M.; Osada Y.; Taketsugu T.; Morokuma K.; Ohno K.. GRRM (A Developmental Version); Hokkaido University, 2019.

- Togo A.Computer code SPGLIB. See https://atztogo.github.io/spglib/ (accessed Jan 12, 2016).

- Togo A.Computer code PHONOPY. See https://atztogo.github.io/phonopy/ (accessed June 16, 2016).

- Togo A.; Oba F.; Tanaka I. First-principles calculations of the ferroelastic transition between rutile-type and CaCl2-type SiO2 at high pressures. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2008, 78, 134106. 10.1103/physrevb.78.134106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Setyawan W.; Curtarolo S. High-throughput electronic band structure calculations: Challenges and tools. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2010, 49, 299–312. 10.1016/j.commatsci.2010.05.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blatov V. A.; Shevchenko A. P.; Proserpio D. M. Applied topological analysis of crystal structures with the program package ToposPro. Cryst. Growth Des. 2014, 14, 3576–3586. 10.1021/cg500498k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.