Abstract

Both HIV disease and frailty syndrome are risk factors for neurocognitive impairment. Longitudinal research among individuals of the general population suggests that frailty predicts future cognitive decline; however, there is limited evidence for these longitudinal relationships among people living with HIV (PLWH). The current study evaluated and compared rates of cognitive decline over two years among HIV serostatus and frailty status groups. Participants included 50 PLWH and 60 HIV-uninfected (HIV-) participants who were evaluated at baseline and two-year follow-up visits. Baseline frailty status (non-frail, pre-frail, and frail) was determined using Fried frailty phenotype criteria. Neurocognitive functioning was measured using practice-effect corrected scaled scores derived from a comprehensive neuropsychological battery covering seven cognitive domains. Repeated measures analysis was used to estimate rates of global and domain-specific cognitive change from baseline to two-year follow-up among each of six HIV/Frailty status groups. Among PLWH, the pre-frail group demonstrated consistent declines in global cognitive functioning (B=−0.029, p=0.034), processing speed (B=−0.047, p=0.031), and motor functioning (B=−0.048, p=0.038). Among HIV-participants, pre-frail individuals also declined in global cognitive functioning and processing speed (ps≤0.05). HIV- non-frail participants also declined in the cognitive domains of learning, delayed recall, and motor functioning; however, these declines appeared to be driven by relatively higher baseline scores among this group. Notably, 38% of PLWH changed in frailty status from baseline to follow-up, and those with stable pre-frailty demonstrated higher likelihood for cognitive decline; change in depressive symptoms did not relate to change in frailty status. Current findings highlight pre-frailty as an important clinical syndrome that may be predictive of cognitive decline among PLWH. Interventions to prevent or reduce frailty among vulnerable PLWH are needed to maintain optimal cognitive health.

Keywords: frailty, aging, neuropsychology, cognition, longitudinal study, depression

INTRODUCTION

Individuals aged 65 and older are estimated to compose 20% of the U.S. population in the next decade (Bureau, 2018). Within this same period, due to significant advancement in treatment success, it is estimated that 3 out of 4 people living with HIV (PLWH) will be 50 and older (Smit et al., 2015). As the demographic of both the general population and PLWH ages, preservation of independence and improving overall quality of life in this rapidly aging population is becoming an essential focus of research.

Despite complete viral load suppression and immune recovery among PLWH, this population remains more vulnerable to adverse aging-related health conditions compared to individuals without HIV (Deeks, 2011, Guaraldi et al., 2001, Greene et al., 2015). In particular, PLWH appear to exhibit greater severity of frailty syndrome than uninfected individuals, and frailty also contributes to worsened health outcomes among PLWH (Brothers et al., 2014). Frailty is most widely accepted as a common physiological syndrome characterized by decreased reserve and diminished resistance to stressors, resulting in a cumulative decline across multiple physiological systems and causes vulnerability to adverse outcomes (Ferrucci et al., 2004). Frailty has increased prevalence with advanced age and carries an increased risk for adverse health outcomes, including depression, decreased ability to self-care, poorer quality of life, and mortality (Fried et al., 2001, Vaughan et al., 2015, Slaets, 2006, Rizzoli et al., 2013, Erlandson et al., 2014). Frailty is also independently associated with HIV (Kooij et al., 2016), and may be present in up to half of older adults living with HIV (Onen et al., 2010). Together, the combined effect of HIV and frailty may amplify and compound HIV disease burden and subsequently decrease the ability to remain independent in later life.

Furthermore, both frailty and HIV are independently linked to cognitive impairment, a robust contributor to decreased independence and poorer quality of life among those with and without HIV (Heaton et al., 2004a, Oppenheim et al., 2018). Current understandings of frailty and cognition suggest that their relationship is bidirectional. For instance, longitudinal studies among the general population of older adults suggest that frailty status predicts cognitive decline (Godin et al., 2017, Auyeung et al., 2011, Mitnitski et al., 2011, Lee et al., 2018, Brigola et al., 2017) and incident dementia (Boyle et al., 2010a, Gray et al., 2013, Buchman et al., 2007), and also that cognitive decline is predictive of the development of frailty syndrome (Raji et al., 2010, Gale et al., 2017). A large body of research suggests several multi-system, physiologic processes underlie the pathogenesis of frailty syndrome and may explain its contribution to cognitive impairment. For instance, it has been suggested that chronic inflammation and immune activation contribute to frailty via intermediary systems, including through decreased musculoskeletal endocrine and cardiovascular hematologic functioning (Chen et al., 2014). In turn, physiologic dysregulation contributes to systematic decline (including declines to brain functioning) that is thought to be manifested through decreased muscle mass, strength, and power, and through slowed motor performance (Puts et al., 2005).

HIV, along with immune response to HIV disease, also has direct effects on cognitive impairment, particularly towards the later stages of the illness. In 2016, 35% of American PLWH aged 50 years and older had Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) (Prevention, 2018), and despite decreased incidence of more severe forms of cognitive impairment (particularly HIV-associated dementia) in the cART era (Heaton et al., 2010), HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) (McArthur et al., 2004) as well as microglial activation or neuroinflammation generated by the HIV virus (Harezlak et al., 2011) continue to persist. Among PLWH, it is estimated that 30% of individuals with asymptomatic HIV disease and 50% with diagnoses of AIDS experience symptoms of mild neurocognitive impairment (Heaton et al., 2011). Similar to frailty syndrome, HAND has been linked to inflammatory and immune dysfunction, which in part explain cognitive impairment in this population (Cysique and Brew, 2009).

Recently, frailty’s effect on disease manifestation has been reported in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Through a cross-sectional study, Wallace et al. (2019) found that frailty moderated the relationship between AD disease pathology and expression of AD dementia, such that low frailty resulted in the absence of disease presentation even in people who already exhibited disease pathology. While frailty’s impact has provided new insights in prevention and treatment within AD, its effect on cognitive impairment among PLWH has been relatively unexplored. To date, we know that cross-sectionally, among PLWH, low frailty status is associated with the absence of cognitive impairment in older adults (Wallace et al., 2017) and that high frailty is associated with worse global neurocognitive functioning, verbal fluency, executive functioning, processing speed, and motor skills (Oppenheim et al., 2018).

While these inter-individual correlations have been demonstrated, the interaction of HIV and frailty on neurocognition within the individual over time remains unknown. Understanding cognitive vulnerabilities in the context of both HIV and frailty may direct us towards possible neurobiological processes of these combined conditions and ultimately inform prevention and treatment. The present study seeks to (1) examine the longitudinal change in neurocognitive functioning by HIV serostatus and frailty status over a period of two years, and to (2) explore cognitive domains most associated with decline in the context of HIV and frailty. We hypothesized that PLWH who were also frail would show the most neurocognitive decline from baseline to two-year follow-up when compared to other groups.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were 50 PLWH and 60 HIV-uninfected (HIV-) individuals enrolled in the Multi-Dimensional Successful Aging among HIV-Infected Adults study conducted at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) (Moore et al., 2018, Rooney et al., 2019). All participants were aged 35 to 65 at baseline, consistent with study recruitment goals. The current study is a secondary analysis on available longitudinal frailty and neurocognitive data. Parent study exclusion criteria were: 1) presence of a neurological condition known to impact neurocognitive functioning (e.g., stroke, non-HIV neurological disorder); 2) history of head injury with loss of consciousness or seizure disorder; 3) diagnosis of a psychotic disorder or severe learning disorder (e.g., WRAT-4 Reading score <70); and 4) positive urine toxicology for illicit substances (excluding marijuana) on the day of testing. Inclusion criteria for the current study were having available frailty data at baseline and neurocognitive data at baseline and at the 2-year follow-up visit. All study procedures were approved by the UCSD Institutional Review Board. All participants were English-speaking and provided written, informed consent.

Participants were categorized into six groups based on HIV status and baseline frailty status: HIV+/Non- frail (n=18); HIV-/Non-frail (n=39); HIV+/Pre-frail (n=25); HIV-/Pre-frail (n=20); HIV+/Frail (n=7); and HIV-/Frail (n=1). Because only one HIV- participant met criteria for frailty at baseline, the HIV-/Frail group was not included in any statistical analyses.

Measures

Frailty Status

The Fried Frailty Phenotype was used to determine physical frailty status for each participant (Fried et al., 2001). Consistent with the Fried Frailty Phenotype, five domains of physical functioning were assessed, and deficits were determined as follows: 1) unintentional weight loss (self-reported ≥10 pounds lost in the past year); 2) weakness (<20th percentile of normative sample for grip strength, stratified by sex and body mass index); 3) exhaustion (self-reported via elevations on items 7 and 9 of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression [CES-D] scale) (Lewinsohn et al., 1997); 4) slow walking speed (<20th percentile of normative sample for total seconds to walk 15 feet, stratified by sex and height); and 5) low physical activity (<383 kcal/week for men, <270 kcal/week for women; self-reported via the International Physical Activity Questionnaire) (Hallal and Victora, 2004). Three frailty phenotypes were identified by the number of symptoms met: Frail (3 to 5 symptoms); Pre-Frail (1–2 symptoms); Non-frail (0 symptoms). All participants completed this frailty assessment at baseline, and most (n=96; 87%) completed it at the two-year follow-up visit.

Neurocognitive Functioning

All participants completed a standardized, comprehensive battery of neuropsychological tests at baseline and at two-year follow-up. This battery covered seven domains of neurocognitive functioning: verbal fluency, executive functioning, processing speed, learning, delayed recall, working memory, and motor skills. Details about this battery have been published previously (Carey et al., 2004). Raw test scores were converted to practice-effect-corrected scaled scores (M=10, SD=3 in normative samples) (Heaton et al., 2004b, Norman et al., 2011). Scaled scores were not corrected for demographics, as neurocognitive change is best evaluated using neuropsychological test scores that do not remove reliable sources of variance in change over time (e.g., age). Scaled scores were averaged within each neurocognitive domain to create domain-specific scaled scores and were averaged across all tests to create a global scaled score.

Everyday Functioning and Quality of Life

Declines in instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) were self-reported via a modified version of the Lawton and Brody ADL questionnaire covering 11 IADL tasks (Heaton et al., 2004a). Participants were asked to rate their current ability to perform each task compared to their highest ability level (i.e., when they were functioning “at their best”). For each item, a decline was identified if participants reported being less able to complete the activity independently (i.e., needing more help) compared to their highest ability. The number of reported declines were summed to obtain a total number of IADL declines, with a possible range of 0 (no decline) to 11 (decline on all IADL items). Self-reported physical- and mental health-related quality of life were assessed via the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form Health Survey (MOS SF-36). Physical and mental health composite scores were calculated via validated summary score formulas derived from an obliquely rotated factor solution (Farivar et al., 2007). Higher scores on these composites represent better health-related quality of life.

Psychiatric and Neuromedical Diagnoses

The Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI, v2.1)(World Health Organization, 1998) is a structured, computer-assisted interview that was administered to determine the presence of current and lifetime major depressive disorder (MDD) based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – 4th Edition (DSM-IV) criteria. Participants also completed a comprehensive medical history evaluation assessing for presence of four cardiovascular conditions (i.e., hypertension, hyperlipidemia, congestive heart failure, and myocardial infarction) known to be highly prevalent in frailty syndrome (Afilalo et al., 2009, Newman et al., 2001). These conditions were determined based on a combination of self-report (e.g., known diagnosis, taking medication for condition) and laboratory measurements (i.e., blood pressure, blood panel), and the number of cardiovascular conditions per participant was summed. All participants were screened for HIV infection using a fingerstick test (Medmira, Nova Scotia, Canada) and confirmed with an Abbott RealTime HIV-1 test (Abbott Laboratories, Illinois, USA) or by submitting specimens to a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified laboratory (ARUP Laboratories, Utah, USA) for HIV-1 viral load quantitation. For participants with confirmed HIV infection, specific HIV disease characteristics were evaluated (i.e., AIDS status, plasma viral load, current and nadir CD4+ T-cell counts, estimated duration of HIV disease, and current antiretroviral therapy regimen).

Statistical Analyses

First, frequency of each frailty symptom was characterized in each HIV serostatus group. Next, to compare demographic and clinical characteristics between the six HIV/Frailty groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or chi-squared analysis was used for continuous or dichotomous variables, respectively. Nonparametric Wilcoxon tests were used for non-normally distributed continuous variables (i.e., current and nadir CD4 counts). Pairwise comparisons were made using Tukey’s H.S.D. (α = 0.05) for continuous outcomes or Bonferroni-adjustments (α = 0.05/6 = .008) for dichotomous outcomes. Next, change in neurocognitive functioning over time was examined separately by HIV status by the regression of global scaled score on time in multigroup repeated measures models, with frailty status (i.e., non-frail, pre-frail, or frail) as a grouping variable. That is, frailty status group-specific parameters were estimated for change in neurocognitive functioning over time among PLWH and among HIV-uninfected individuals. These analyses were repeated for each of the seven neurocognitive domain scaled score outcomes. This method provides an estimation of the unstandardized beta (representing the change in neurocognitive scaled score by unit of time [months]) for each HIV/frailty status group, allowing us to examine whether there was significant change in each group (i.e., significantly different from zero). In order to account for the non-independence of data due to repeated assessment, computation of standard errors was carried out using a sandwich estimator. For any HIV/Frailty status group that exhibited a statistically significant decline in global or domain scaled scores, three follow up analyses were conducted: 1) Wald χ2-tests were used to explore whether the observed decline was significantly different from that of other frailty groups within HIV serostatus; 2) the effect of individual frailty symptoms (measured at baseline) on cognitive change was explored using additional repeated measures models; and 3) the effect of baseline cognitive score on cognitive change score (i.e., follow-up score minus baseline score) was examined within HIV serostatus for cognitive domains with significant findings using Pearson r correlation. Last, we examined whether there were changes in frailty status from baseline to follow-up visit and if these were related to changes in depressive symptoms among PLWH, as this was relevant for our interpretation of observed changes in neurocognition. Using one-way ANOVA, PLWH who had stable frailty status were compared to those who either improved (i.e., became less frail) or declined (i.e., became more frail) by CES-D change score (i.e., follow-up CES-D minus baseline CES-D; positive values indicate worsening depression). All descriptive analyses were conducted using JMP Pro 12.0.1 (JMP Pro Version 12.0.1, 1989–2007), and all longitudinal analyses were conducted using Mplus, version 7.4 (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2012).

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Among PLWH, exhaustion was the most common frailty symptom (66%), followed by low activity (53%), weight loss (38%), slowness (19%), and weakness (16%). Among HIV- participants, weakness was the most common frailty symptom (52%), followed by low activity (28%), exhaustion (24%), weight loss (14%), and slowness (10%). Demographic and clinical characteristics of frailty status by HIV serostatus are presented in Table 1. Education differed among groups, with the HIV-/Non-frail and HIV-/Pre-frail having more years of education than the HIV+/Non-frail group (p <.04). No significant differences in age, sex, race/ethnicity, or WRAT-4 Reading scores were noted among groups. Regarding neuropsychiatric characteristics, there were no differences in self-reported current depression symptoms (CES-D total score) or current DSM diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) among groups; however, there were significant differences in lifetime DSM diagnosis of MDD (LT MDD). Regardless of frailty status, PLWH had higher incidences of LT DSM MDD compared to HIV- counterparts (p <.001). No difference in the number of comorbid cardiovascular conditions were observed among groups. Among PLWH, HIV disease characteristics did not differ by frailty status.

Table 1.

Participant demographic and disease characteristics at baseline by frailty and HIV status

| Non-frail | Pre-frail | Frail | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV+ (n=18) | HIV- (n=39) | HIV+ (n=25) | HIV- (n=20) | HIV+ (n=7) | HIV- (n=1) | p-value | Pairwise* | |

| a | b | c | d | e | f | |||

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age (yrs) | 52.7 (8.5) | 50.4 (8.2) | 50.3 (8.0) | 52.0 (7.8) | 50.7 (9.6) | 52 | .76 | -- |

| Sex (male) | 11 (92) | 32 (82) | 21 (84) | 15 (75) | 7 (100) | 0 (0) | .18 | -- |

| Race/Ethnicity (White) | 8 (44%) | 29 (74%) | 10 (40%) | 10 (50%) | 3 (43%) | 0 (0%) | .02 | -- |

| Education (yrs) | 13.1 (2.3) | 15.1 (2.4) | 14.5 (2.1) | 15.0 (2.0) | 13.6 (3.2) | 15 | .04 | b > a; d > a |

| WRAT-4 Reading | 101.2 (12.6) | 106.3 (12.1) | 104.2 (12.1) | 102.3 (10.5) | 99.9 (7.7) | 96 | .36 | -- |

| Psychiatric characteristics | ||||||||

| CES-D | 7 [4–13] | 5 [2–12] | 15 [10–23] | 4 [1–7] | 27 [14–31] | 3 | .93 | -- |

| Current MDD | 1 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | .36 | -- |

| Lifetime MDD | 11 (61%) | 9 (23%) | 14 (56%) | 2 (10%) | 4 (57%) | 0 (0%) | <.001 | a, c > b, d; e > d |

| Number of comorbid cardiovascular conditions | .83 (.70) | .26 (.55) | 1.04 (.91) | .47 (.70) | 1.43 (.79) | 2 | .68 | -- |

| HIV Characteristics | ||||||||

| Historical AIDS diagnosis | 5 (27%) | -- | 11 (44%) | -- | 4 (57%) | -- | .14 | -- |

| Detectable viral load | 2 (11%) | -- | 2 (8%) | -- | 1 (14%) | -- | .94 | -- |

| Current CD4 count (cells/mm3) | 659 [318–926] | -- | 644 [453–954] | -- | 706 [628–901] | -- | .47 | -- |

| Nadir CD4 (cells/mm3) | 134 [37–209] | -- | 250 [31–456] | -- | 269 [45–710] | -- | .06 | -- |

| Est. duration living with HIV (yrs) | 17.8 (8.9) | -- | 17.3 (8.2) | -- | 16.0 (8.6) | -- | .67 | -- |

| On HAART | 17 (94%) | -- | 21 (84%) | -- | 6 (86%) | -- | .25 | -- |

Values are presented in mean (SD), N (%), or median [IQR];

WRAT-4 Reading = Wide Range Achievement Test-Fourth Edition, Reading subtest;

CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale;

MDD = Major Depressive Disorder;

Number of comorbid cardiovascular conditions include hypertension, hyperlipidemia, congestive heart failure, and myocardial infarction;

Pairwise comparisons were examined using Tukey’s H.S.D (α = 0.05) for continuous outcomes or Bonferroni-adjustments (α = 0.05/6 = .008) for dichotomous outcomes. HIV-/Frail group (f) was not used in comparisons.

Neurocognitive, everyday functioning, and self-reported health problems among HIV/Frailty groups at baseline

Neurocognitive and everyday functioning data at baseline are presented in Table 2. Generally, the HIV-/Non-frail group performed better on global, learning, recall, and motor domains compared to the other groups. Specifically, the HIV-/Non-frail group had higher global functioning scores than the HIV+/Non-frail and HIV+/Frail groups (p = .005), exhibited better learning scores compared to all HIV+ groups (p < .001), and better recall scores compared to HIV+/Non-frail and HIV+/Frail groups (p < .001). Similarly, motor functioning was worse among HIV+/Pre-frail and HIV+/Frail groups compared to the HIV-/Non-frail group (p = .003). Regarding reported problems with instrumental activity of daily living (IADL), the HIV+/Frail group endorsed declines in significantly more domains than all groups (p <.001). These results were consistent with participant reported physical health quality of life (SF36 Physical Composite), where the HIV+/Frail group reported significantly worse physical health quality of life than all other groups (p <.001). With regard to self-report of mental health quality of life (SF36 Mental Health Composite), the HIV+/Pre-frail group reported worse mental health than all other groups except for the HIV+/Frail group (p <.001). Tukey’s HSD pairwise comparisons also revealed that the difference in mental health quality of life between the HIV+/Frail group and the HIV-/Non- frail group approached statistical significance (p=0.067).

Table 2.

Neurocognitive functioning, perceived health, and everyday functioning at baseline

| Non-frail | Pre-frail | Frail | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV+ (n=18) | HIV- (n=39) | HIV+ (n=25) | HIV- (n=20) | HIV+ (n=7) | HIV- (n=1) | p-value | Pairwise* | |

| a | b | c | d | e | f | |||

| Cognitive Functioning at baseline | ||||||||

| Global | 9.0 (1.8) | 10.4 (1.6) | 9.5 (2.0) | 9.8 (1.6) | 8.1 (1.0) | 7.6 | .005 | b > a, e |

| Verbal Fluency | 10.3 (2.2) | 10.9 (1.9) | 10.4 (2.8) | 10.2 (1.8) | 9.6 (2.0) | 10.3 | .55 | -- |

| Executive Functioning | 8.8 (2.7) | 10.6 (2.4) | 9.6 (1.9) | 10.2 (2.4) | 8.2 (2.1) | 8.3 | .03 | -- |

| Processing Speed | 10.1 (1.7) | 10.6 (2.6) | 10.6 (2.7) | 10.8 (2.4) | 8.9 (1.3) | 9 | .22 | -- |

| Learning | 6.8 (2.5) | 9.2 (2.3) | 7.3 (2.8) | 7.6 (2.1) | 5.9 (1.7) | 5 | <.001 | b > a, c, e |

| Delayed Recall | 6.4 (2.4) | 9.2 (2.1) | 8.3 (2.8) | 8.1 (2.3) | 6.1 (2.1) | 4 | <.001 | b > a, e |

| Working Memory | 10.0 (2.9) | 9.9 (2.5) | 9.6 (3.0) | 10.6 (2.6) | 9.3 (1.4) | 9.5 | .75 | -- |

| Motor Skills | 9.0 (2.9) | 10.8 (2.5) | 8.7 (2.5) | 9.3 (2.1) | 7.4 (3.6) | 3.5 | .003 | b > c, e |

| Health and Everyday functioning | ||||||||

| IADL declines | 0.24 (0.44) | 0.10 (0.31) | 0.21 (0.42) | 0.10 (0.31) | 0.86 (0.38) | 0 | <.001 | e > a, b, c, d |

| SF36 Physical Composite | 52.2 (8.0) | 54.7 (7.4) | 44.3 (10.5) | 51.8 (11.2) | 24.4 (10.5) | 33.1 | <.001 | e < a, b, c, d; c < b |

| SF36 Mental Health Composite | 53.7 (6.6) | 54.2 (8.5) | 43.1 (14.9) | 54.6 (8.5) | 42.6 (17.0) | 59.8 | <.001 | c < a, b, d |

Cognitive domain scores are presented as scaled scores, M(SD);

IADL = Instrumental Activities of Daily Living;

SF36 = Physical and Mental Health subcomponents of the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form Health Survey (MOS SF-36), composite scores were calculated via summary scores from obliquely rotated factor solution (Farivar et al., 2007), higher scores represent better health-related quality of life;

Pairwise comparisons were examined using Tukey’s H.S.D (α = 0.05) for continuous outcomes or Bonferroni-adjustments (α = 0.05/6 = .008) for dichotomous outcomes. HIV-/Frail group (f) was not used in comparisons.

Change in neurocognitive functioning from baseline to two-year follow-up

Within persons longitudinal analyses were completed to compare cognitive outcomes by domain within HIV and Frailty subgroups from baseline to two-year follow-up (see Table 3). Within HIV+ groups, we found that individuals with pre-frail status at baseline demonstrated significant global cognitive decline at follow-up (B= −.029, SE=.014, p= .034), exhibiting an estimated 0.7 unit decrease in global scaled score over the entire two year period. This observed decline among HIV+/Pre-frail participants was marginally different from the cognitive change observed among HIV+/Non-frail participants (Wald χ2=3.75, df=1, p=0.053), and not statistically different from that of HIV+/Frail participants (Wald χ2 =1.24, df=1, p=0.265). None of the individual baseline frailty criteria on their own were significant predictors of global cognitive change over time (ps>0.05). In order to determine whether the observed decline among HIV+/Pre-frail participants was possibly confounded by their relatively higher baseline cognitive scores compared to other HIV+ groups, the relationship between baseline global cognitive score and global change score was examined among all PLWH in our sample. Baseline global score was not significantly correlated with global change score among PLWH (r=−0.08, p=0.63).

Table 3.

Change in cognitive functioning (per month) from baseline to year 2 follow-up in people living with and without HIV by frailty status

| HIV+ (N=50) | HIV- (N=60) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global | n | B | SE | p | n | B | SE | p |

| Non-frail | 18 | 0.005 | 0.011 | 0.651 | 39 | −0.009 | 0.006 | 0.122 |

| Pre-frail | 25 | −0.029 | 0.014 | 0.034 | 20 | −0.013 | 0.006 | 0.050 |

| Frail | 7 | −0.002 | 0.020 | 0.934 | 1 | -- | -- | -- |

| Verbal Fluency | ||||||||

| Non-frail | 18 | 0.018 | 0.016 | 0.268 | 39 | 0.014 | 0.009 | 0.117 |

| Pre-frail | 25 | −0.016 | 0.018 | 0.374 | 20 | 0.000 | 0.014 | 0.988 |

| Frail | 7 | 0.003 | 0.023 | 0.882 | 1 | -- | -- | -- |

| Executive Functioning | ||||||||

| Non-frail | 18 | 0.014 | 0.017 | 0.423 | 39 | −0.001 | 0.010 | 0.902 |

| Pre-frail | 25 | −0.026 | 0.021 | 0.215 | 20 | −0.001 | 0.017 | 0.959 |

| Frail | 7 | −0.025 | 0.018 | 0.178 | 1 | -- | -- | -- |

| Processing Speed | ||||||||

| Non-frail | 18 | 0.010 | 0.014 | 0.471 | 39 | 0.000 | 0.010 | 0.996 |

| Pre-frail | 25 | −0.047 | 0.022 | 0.031 | 20 | −0.027 | 0.011 | 0.011 |

| Frail | 7 | 0.006 | 0.025 | 0.809 | 1 | -- | -- | -- |

| Learning | ||||||||

| Non-frail | 18 | −0.013 | 0.023 | 0.573 | 39 | −0.033 | 0.016 | 0.045 |

| Pre-frail | 25 | −0.012 | 0.018 | 0.525 | 20 | −0.024 | 0.018 | 0.180 |

| Frail | 7 | 0.023 | 0.043 | 0.588 | 1 | -- | -- | -- |

| Delayed Recall | ||||||||

| Non-frail | 18 | 0.006 | 0.024 | 0.792 | 39 | −0.032 | 0.015 | 0.029 |

| Pre-frail | 25 | −0.043 | 0.022 | 0.054 | 20 | −0.028 | 0.024 | 0.240 |

| Frail | 7 | −0.009 | 0.033 | 0.778 | 1 | -- | -- | -- |

| Working Memory | ||||||||

| Non-frail | 18 | −0.007 | 0.016 | 0.683 | 39 | 0.007 | 0.016 | 0.656 |

| Pre-frail | 25 | −0.002 | 0.021 | 0.926 | 20 | 0.007 | 0.016 | 0.683 |

| Frail | 7 | −0.060 | 0.051 | 0.243 | 1 | -- | -- | -- |

| Motor Skills | ||||||||

| Non-frail | 18 | −0.008 | 0.028 | 0.784 | 39 | −0.033 | 0.013 | 0.012 |

| Pre-frail | 25 | −0.048 | 0.023 | 0.038 | 20 | −0.013 | 0.018 | 0.457 |

| Frail | 7 | 0.056 | 0.046 | 0.223 | 1 | -- | -- | -- |

Note. Model estimates (B) reflect the change in cognitive scaled score per month over the two-year study period.

Examination of domain-specific cognitive changes revealed that the HIV+/Prefrail group exhibited significant declines in processing speed (B= −.047, SE=.022, p= .031) and motor functioning (B= −.048, SE=.023, p= .038), and a decline in delayed recall that approached statistical significance (B= −.043, SE=.022, p= .054). The observed decline in processing speed among the HIV+/Pre-frail group was significantly different from change among the HIV+/Non-frail group (Wald χ2=4.87, df=1, p=0.027), but not the HIV+/Frail group (p>0.05). The observed decline in motor functioning among the HIV+/Pre-frail group was significantly different from that among the HIV+/Frail group (Wald χ2=4.11, df=1, p=0.043), but not from change among the HIV+/Non-frail group (p>0.05). The marginal decline in delayed recall among the HIV+/Pre-frail group was not significantly different from change among the HIV+/Non-frail or HIV+/Frail groups (ps>0.05). Additionally, none of the individual baseline frailty criteria on their own were significant predictors of decline in processing speed or motor functioning (ps>0.05); however, baseline exhaustion predicted a decline in delayed recall among PLWH (B= −.048, SE=.023, p= .041). Last, baseline processing speed score and baseline motor score were not correlated with processing speed change score (r=−0.05, p=0.79) or motor change score (r=−0.18, p=0.28), respectively, among PLWH.

Among HIV- participants, the HIV-/Pre-frail group also seemed to decline in global function (B= −.013, SE=.006, p= .050) and processing speed (B= −.027, SE=.011, p= .011). The observed decline in processing speed among the HIV-/Pre-frail group when compared to the HIV-/Non-frail group approached statistical significance (Wald χ2=3.32, df=1, p=0.069). Among all HIV- participants, baseline processing speed score was not significantly correlated with processing speed change score (r=−0.17, p=0.22). Notably, a different pattern of decline emerged for other cognitive domains among seronegative individuals. Specifically, the HIV-/Non- frail individuals also appeared to decline in cognitive domains of learning (B= −.033, SE=.016, p= .045), delayed recall (B= −.032, SE=.015, p= .029), and motor functioning (B= −.033, SE=.013, p= .012). Wald χ2 tests revealed that none of these observed declines among the HIV-/Non-frail group were significantly different than those of the HIV-/Pre-frail group (ps>0.05). Among all HIV- individuals, however, baseline scores in domains of learning, delayed recall, and motor functioning were each significantly related to respective change scores (learning: r=−0.55, p<0.01; delayed recall: r=−0.48, p<0.01; motor: r=−0.37, p<0.01), indicating that participants with higher baseline scores were more likely to show decline (i.e., a negative change score) at follow up.

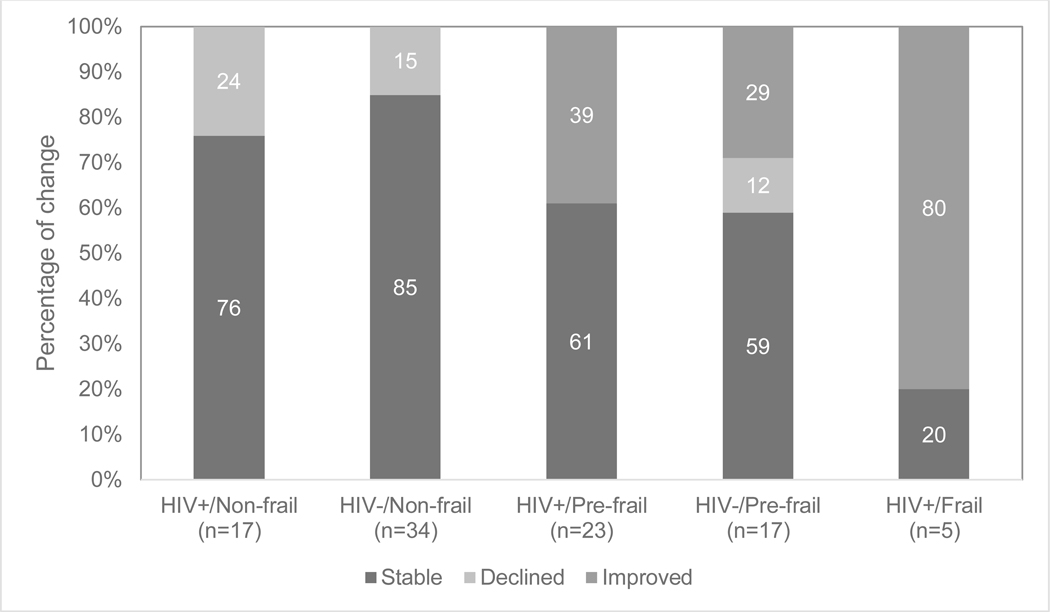

It should also be noted that frailty status in some participants changed from baseline assessment to two-year follow-up. Out of all 96 participants with frailty status data at baseline and follow-up, 70% (n=67) had no change in frailty status over the 2-year period, with 11% (n=11) becoming more frail and 19% (n=18) becoming less frail. When examining changes in frailty by HIV/Frailty group, different patterns emerge (Figure 1). The HIV- and HIV+ non-frail groups showed similar patterns such that 85% and 76%, respectively, had no change in frailty status, and 15% and 24%, respectively, declined from non-frail to pre-frail. Among the pre-frail groups, 59% of HIV- and 61% of HIV+ persons had no change in frailty status, 12% of HIV- and 0% of HIV+ persons declined from pre-frail to frail, and 29% of HIV- and 39% of HIV+ improved from pre-frail to non-frail. Last, out of only five HIV+/Frail participants with follow-up frailty data, one person (20%) had no change in frailty status while three (60%) improved to pre-frail and one (20%) improved to non-frail. Among the 45 PLWH who had frailty status characterized at both visits, CES-D change score (i.e., follow-up CES-D minus baseline CES-D; positive values indicate worsening depression) did not differ significantly by frailty stability (stable: M = −2.1, SD = 15.6; improvers: M = 1.1, SD = 10.0; decliners: M = 4, SD = 14.3; p = 0.64).

Figure 1.

Percentage of change in frailty status from baseline to two-year follow-up by HIV/Frailty groups

Given the fluctuation in frailty status from baseline to follow up among PLWH identified as pre-frail at baseline (i.e., the group that showed the most consistent cognitive declines), we examined likelihood of global cognitive decline (i.e., a negative global change score) among HIV+/Pre-frail participants by frailty stability. That is we compared PLWH who were stably pre-frail [n=14] vs. PLWH who improved from pre-frail to non-frail [n=9]). Logistic regression showed a marginally statistically significant higher likelihood for the stable pre-frail group to show global cognitive decline compared to the group whose frailty status improved (OR = 12.0; 95%CI = 0.96–150.7; p = 0.054).

DISCUSSION

This study uniquely examined within-person neurocognitive change over two years by HIV and frailty status. We found that PLWH who were pre-frail at baseline showed the most consistent neurocognitive decline in global neurocognitive functioning, processing speed, and motor skills, with a trend toward declining delayed recall. Contrary to our hypotheses, our HIV+/Frail group did not demonstrate consistent declines in any neurocognitive domain; however, this group was also not stable in frailty state over time. Additionally, results showed no significant differences in HIV characteristics among HIV+ groups at baseline. We also interestingly found that the HIV-/Non-frail group showed significant declines in learning, delayed recall, and motor skills; however, the decline observed among this group are likely driven by their high baseline scores, making them more likely to decline towards overall means (i.e., regression towards the mean) (Nesselroade et al., 1980). Overall, the current findings highlight the importance of examining pre-frailty as a clinical syndrome among PLWH regardless of HIV disease severity, and emphasize the need for further longitudinal and intervention work to uncover possible mechanisms for declines (or stability) found among each HIV/Frailty group.

Our findings suggest that pre-frailty may be an important marker of risk for neurocognitive decline among PLWH. This is further supported by additional analyses showing no association between baseline cognitive scores and cognitive change scores among PLWH, suggesting that any observed decline among the HIV+/Pre-frail group was not simply due to relatively higher baseline cognitive performance and regression toward the mean. The observed declines among pre-frail PLWH are somewhat inconsistent with findings among several cross-sectional and longitudinal studies in the general population of older adults that show higher rates of cognitive impairment and incident cognitive decline among individuals with higher levels of frailty (Robertson et al., 2014, Robertson et al., 2013). There may be several reasons for our unique finding. First, HIV may exhibit a different relationship to frailty than other disease processes present in more general, community-dwelling older adults without HIV, with different subsequent effects on cognition. This is partly supported by the different frequencies of frailty symptoms found between HIV serostatus groups in our sample. Furthermore, HAND is known to be relatively more stable compared to other age-associated neurodegenerative disorders (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease [AD]) (Rubin et al., 2019). That is, while HIV disease confers risk for developing mild cognitive impairment, having a diagnosis of a mild form of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder does not predict progression to dementia (Clifford and Ances, 2013). It may be that among PLWH, the intermediary pre-frail state is a marker of susceptibility to cognitive decline, and that once this group ultimately reaches frail status, the rate of cognitive decline flattens; however, longitudinal data with more than two time points would be needed to support this hypothesis. Individuals in the HIV+/Frail group also qualitatively demonstrated the lowest baseline neurocognitive scaled scores overall, possibly restricting their ability to decline consistently as a group. Additionally, many of the PLWH identified as frail at baseline improved to pre-frail or non-frail status at the two-year follow-up visit. Although reasons for this reduction in frailty are unclear from our available data, their improved physiological state was likely protective against cognitive decline (Dufour et al., 2013). These changes in frailty status may also suggest that frailty is more of a transitory state among PLWH who are of the ages included in our sample (35 to 65 years). Last, we cannot rule out the possibility that our lack of significant cognitive change findings among the HIV+/Frail group may be lost due to our small sample size (n=7); thus, our findings in this group should be considered preliminary until confirmed with a larger sample size.

The neurocognitive domains showing significant decline among the HIV+/Pre-frail group (i.e., processing speed and motor skills) are consistent with domains commonly affected in HIV (Heaton et al., 2011). The neurobiological mechanisms proposed to contribute to such neurocognitive deficits in the context of HIV include a cascade of neuroinflammatory events that lead to synaptodendritic injury and neuronal apoptosis particularly in subcortical structures (e.g., striatum) (Cody and Vance, 2016, Moore et al., 2006). Furthermore, these HIV-related central nervous system injuries are hypothesized to be exacerbated by health conditions also associated with increased levels of frailty (e.g., vascular co-pathology, aging-related immunological senescence, poor nutrition) (Robertson et al., 2013, Valcour et al., 2004), suggesting possible overlapping factors underlying the link between frailty and cognition among PLWH. Notably, the observed declines in processing speed and motor skills among pre-frail PLWH are inconsistent with literature describing community-dwelling populations without HIV, where memory has been demonstrated to be most associated with frailty syndrome (Brigola et al., 2015). Among non-HIV populations, recent research suggests AD pathology as a potential mechanism linking frailty and cognition (Buchman et al., 2007, Wallace et al., 2019), which initially targets the neuroanatomical networks of memory. Our discrepant findings provide additional evidence that the relationship between frailty and cognition among PLWH may be driven by different neurobiologic mechanisms than those mechanisms found among other clinical populations such as individuals with AD.

Similar to the pattern noted above, the HIV-/Pre-frail group also demonstrated a significant decline in processing speed, with a trending decline in global functioning. Although it is possible that HIV-/Frail individuals may also have declines within these domains, we were unable to address this as we had only one individual that met our inclusion criteria for this group. Interestingly, we found the HIV-/Non-frail group demonstrated significant declines in learning, delayed recall, and motor skills. Whereas declines within memory subtypes (learning and delayed recall) are expected as HIV- persons age, we certainly did not expect these findings for only the non-frail group due to the known research about the relationship between higher levels of frailty and risk for cognitive decline in HIV- older adult populations (Boyle et al., 2010b, Buchman et al., 2007). The post-hoc analysis examining the association between baseline scores and change scores among HIV-participants, however, revealed that higher baseline scores related to greater declines at follow up, which is consistent with the statistical concept of regression toward the mean (Nesselroade et al., 1980). Given that the HIV-/Non-frail group had the highest baseline scores in domains of learning, delayed recall, and motor skills, they may have simply been statistically more likely to show declines at the follow-up visit. Still, we certainly cannot rule out possible underlying biological or physiological processes (e.g., neuroinflammation, neuropathology indicative of neurodegeneration) occurring in this group that are not captured by frailty status and our other available data (i.e., demographics, psychiatric factors, comorbid cardiovascular conditions).

Importantly, the comparisons of baseline neurocognitive scores by HIV/Frailty group show that global functioning, learning, delayed recall, and motor skills are worst among those who are frail, consistent with much of the current cross-sectional research on frailty and cognition among individuals with and without HIV (Oppenheim et al., 2018, Robertson et al., 2014). This also highlights an important distinction between cross-sectional and longitudinal findings. That is, although a cross-sectional analysis of baseline neurocognitive functioning by group suggested that frail PLWH were most vulnerable to neurocognitive deficits, our longitudinal analyses showed that our frail PLWH were not stably frail and were therefore not as high risk for cognitive decline as initially thought. In contrast, our longitudinal analyses identified pre-frail PLWH (especially stably pre-frail PLWH) as most vulnerable to neurocognitive decline. While inter-individual variability is often assumed to apply to within-individual risk for change over time, our findings violate this assumption and highlight a significant study design strength.

In considering mechanisms that may underlie the link between frailty status and cognitive decline among PLWH, one hypothesis might consider the role of HIV disease characteristics, as certain markers (e.g., nadir CD4, viral load detectability) are known to be related to HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment (Heaton et al., 2010). In our sample, however, HIV disease characteristics did not differ between frailty status groups, decreasing the likelihood that these markers of HIV disease were mediating factors. Current depressive symptoms have also repeatedly demonstrated to be independently worse in PLWH and frailty syndrome (Rabkin, 2008, Soysal et al., 2017). Although we did not observe differences in current MDD diagnoses or self-reported symptoms of depression (CES-D), we did see that PLWH reported significantly higher rates of lifetime MDD. Additional analyses showing that changes in frailty were not associated with changes in CES-D score, however, suggest that depressive symptomology did not significantly impact frailty status among PLWH.

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to examine longitudinal change in neurocognitive functioning by HIV and frailty status. Thus, a discussion of our limitations is necessary for future work to build upon the current report. First, our sample size was limited, especially within frail groups. This can be explained by the nature of our study, which required participants to be physically able to travel and sit-through extensive evaluations. While we had enough HIV+/Frail participants for statistical model estimation, we were not able to estimate cognitive change in the HIV-/Frail group. Our small sample size also limited our ability to adjust for covariates in the model and thus we do not know whether certain participant characteristics may explain the relationship between frailty and cognition; however, our results are supported by the fact that there were no differences in demographic/clinical characteristics within each serostatus group by frailty status. Additionally, most HIV+ participants who were identified as frail at baseline improved frailty status by follow-up, limiting our ability to examine only individuals who were stably frail. Although this may be related to the relatively young age of some individuals in our sample, previous work has shown that it is relevant to include younger PLWH in frailty work (Oppenheim et al., 2018). Future studies would benefit from specifically recruiting for individuals in each HIV/Frailty group. Next, although identifying frailty using the Fried criteria is clinically relevant, it is possible that other, more comprehensive operationalizations of frailty (e.g., deficit accumulation index) (Rockwood and Mitnitski, 2007) may increase sensitivity in detecting vulnerability to cognitive change among PLWH. Last, longer-term follow up will be necessary to further understand trajectories of decline (linear or non-linear) or markers of stability in HIV/frailty groups.

In summary, our findings suggest that pre-frail PLWH (especially those who are stably pre-frail) are vulnerable to global neurocognitive decline, and decline in the specific cognitive domains of processing speed, motor skills, and possibly delayed recall. Interventions to reduce and prevent frailty syndromes among PLWH could help improve and maintain optimal neurocognitive function in this at-risk population. Specifically, interventions that include a group physical activity component seem to be the most effective in reducing frailty among community-dwelling older adults (Puts et al., 2017, Montoya et al., 2019). Additionally, improving positive psychosocial factors may be another viable frailty prevention method among PLWH (Rubtsova et al., 2018); however, at this time efficacy of such frailty interventions among PLWH is unknown. Further understanding biopsychosocial risk factors associated with frailty and neurocognitive decline among PLWH are needed in order to develop appropriate and effective interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The San Diego HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center [HNRC] group is affiliated with the University of California, San Diego, the Naval Hospital, San Diego, and the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System, and includes: Director: Robert K. Heaton, Ph.D., Co-Director: Igor Grant, M.D.; Associate Directors: J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D., Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D., and Scott Letendre, M.D.; Center Manager: Thomas D. Marcotte, Ph.D.; Jennifer Marquie-Beck, M.P.H.; Melanie Sherman; Neuromedical Component: Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D. (P.I.), Scott Letendre, M.D., J. Allen McCutchan, M.D., Brookie Best, Pharm.D., Rachel Schrier, Ph.D., Debra Rosario, M.P.H.; Neurobehavioral Component: Robert K. Heaton, Ph.D. (P.I.), J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D., Steven Paul Woods, Psy.D., Thomas D. Marcotte, Ph.D., Mariana Cherner, Ph.D., David J. Moore, Ph.D., Matthew Dawson; Neuroimaging Component: Christine Fennema-Notestine, Ph.D. (P.I.), Monte S. Buchsbaum, M.D., John Hesselink, M.D., Sarah L. Archibald, M.A., Gregory Brown, Ph.D., Richard Buxton, Ph.D., Anders Dale, Ph.D., Thomas Liu, Ph.D.; Neurobiology Component: Eliezer Masliah, M.D. (P.I.), Cristian Achim, M.D., Ph.D.; Neurovirology Component: David M. Smith, M.D. (P.I.), Douglas Richman, M.D.; International Component: J. Allen McCutchan, M.D., (P.I.), Mariana Cherner, Ph.D.; Developmental Component: Cristian Achim, M.D., Ph.D.; (P.I.), Stuart Lipton, M.D., Ph.D.; Participant Accrual and Retention Unit: J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D. (P.I.), Jennifer Marquie-Beck, M.P.H.; Data Management and Information Systems Unit: Anthony C. Gamst, Ph.D. (P.I.), Clint Cushman; Statistics Unit: Ian Abramson, Ph.D. (P.I.), Florin Vaida, Ph.D. (Co-PI), Anya Umlauf, M.S., Bin Tang, Ph.D.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the United States Government.

FUNDING / SUPPORT

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (grant numbers R01MH099987, P30MH062512, R25MH081482 (stipend support to ECP)), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (grant number F31 AA027198 (stipend support to EWP)), and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (grant number T32 DA031098 (stipend support to NSS)).

REFERENCES

- AFILALO J, KARUNANANTHAN S, EISENBERG MJ, ALEXANDER KP & BERGMAN H 2009. Role of frailty in patients with cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol, 103, 1616–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AUYEUNG TW, LEE JSW, KWOK T & WOO J 2011. Physical Frailty Predicts Future Cognitive Decline - a Four-Year Prospective Study in 2737 Cognitively Normal Older Adults. Journal of Nutrition Health & Aging, 15, 690–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOYLE PA, BUCHMAN AS, BARNES LL & BENNETT DA 2010a. Effect of a Purpose in Life on Risk of Incident Alzheimer Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment in Community-Dwelling Older Persons. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67, 304–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOYLE PA, BUCHMAN AS, WILSON RS, LEURGANS SE & BENNETT DA 2010b. Physical frailty is associated with incident mild cognitive impairment in community-based older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc, 58, 248–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRIGOLA AG, LUCHESI BM, ALEXANDRE TDS, INOUYE K, MIOSHI E & PAVARINI SCI 2017. High burden and frailty: association with poor cognitive performance in older caregivers living in rural areas. Trends Psychiatry Psychother, 39, 257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRIGOLA AG, ROSSETTI ES, DOS SANTOS BR, NERI AL, ZAZZETTA MS, INOUYE K & PAVARINI SCI 2015. Relationship between cognition and frailty in elderly: A systematic review. Dement Neuropsychol, 9, 110–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROTHERS TD, KIRKLAND S, GUARALDI G, FALUTZ J, THEOU O, JOHNSTON BL & ROCKWOOD K 2014. Frailty in people aging with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. J Infect Dis, 210, 1170–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUCHMAN AS, BOYLE PA, WILSON RS, TANG Y & BENNETT DA 2007. Frailty is associated with incident Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline in the elderly. Psychosom Med, 69, 483–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUREAU, U. S. C. 2018. Older People Projected to Outnumber Children [Online]. US Census Bureau; Available: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2018/cb18-41-population-projections.html [Accessed February 26 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- CAREY CL, WOODS SP, GONZALEZ R, CONOVER E, MARCOTTE TD, GRANT I, HEATON RK & GROUP H 2004. Predictive validity of global deficit scores in detecting neuropsychological impairment in HIV infection. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol, 26, 307–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN XJ, MAO GX & LENG SX 2014. Frailty syndrome: an overview. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 9, 433–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLIFFORD DB & ANCES BM 2013. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder. Lancet Infect Dis, 13, 976–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CODY SL & VANCE DE 2016. The neurobiology of HIV and its impact on cognitive reserve: A review of cognitive interventions for an aging population. Neurobiol Dis, 92, 144–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CYSIQUE LA & BREW BJ 2009. HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment in the context undetectable plasma viral load. Journal of Neurovirology, 15, 19–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEEKS SG 2011. HIV infection, inflammation, immunosenescence, and aging. Annu Rev Med, 62, 141–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUFOUR CA, MARQUINE MJ, FAZELI PL, HENRY BL, ELLIS RJ, GRANT I, MOORE DJ & GROUP, H. 2013. Physical exercise is associated with less neurocognitive impairment among HIV-infected adults. J Neurovirol, 19, 410–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERLANDSON KM, SCHRACK JA, JANKOWSKI CM, BROWN TT & CAMPBELL TB 2014Functional impairment, disability, and frailty in adults aging with HIV-infection. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep, 11, 279–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FARIVAR SS, CUNNINGHAM WE & HAYS RD 2007. Correlated physical and mental health summary scores for the SF-36 and SF-12 Health Survey, V.I. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 5, 54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FERRUCCI L, GURALNIK JM, STUDENSKI S, FRIED LP, CUTLER GB JR., WALSTON JD & INTERVENTIONS ON FRAILTY WORKING, G. 2004. Designing randomized, controlled trials aimed at preventing or delaying functional decline and disability in frail, older persons: a consensus report. J Am Geriatr Soc, 52, 625–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRIED LP, TANGEN CM, WALSTON J, NEWMAN AB, HIRSCH C, GOTTDIENER J, SEEMAN T, TRACY R, KOP WJ, BURKE G, MCBURNIE MA & CARDIOVASCULAR HEALTH STUDY COLLABORATIVE RESEARCH, G. 2001. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 56, M146–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GALE CR, RITCHIE SJ, COOPER C, STARR JM & DEARY IJ 2017. Cognitive Ability in Late Life and Onset of Physical Frailty: The Lothian Birth Cohort 1936. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65, 1289–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GODIN J, ARMSTRONG JJ, ROCKWOOD K & ANDREW MK 2017. Dynamics of Frailty and Cognition After Age 50: Why It Matters that Cognitive Decline is Mostly Seen in Old Age. Journal of Alzheimers Disease, 58, 231–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRAY SL, ANDERSON ML, HUBBARD RA, LACROIX A, CRANE PK, MCCORMICK W, BOWEN JD, MCCURRY SM & LARSON EB 2013. Frailty and Incident Dementia. Journals of Gerontology Series a-Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 68, 1083–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREENE M, COVINSKY KE, VALCOUR V, MIAO Y, MADAMBA J, LAMPIRIS H, CENZER IS, MARTIN J & DEEKS SG 2015. Geriatric Syndromes in Older HIV-Infected Adults. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 69, 161–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUARALDI G, VENTURA P, ALBUZZA M, ORLANDO G, BEDINI A, AMORICO G & ESPOSITO R 2001. Pathological fractures in AIDS patients with osteopenia and osteoporosis induced by antiretroviral therapy. AIDS, 15, 137–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALLAL PC & VICTORA CG 2004. Reliability and validity of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). Med Sci Sports Exerc, 36, 556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAREZLAK J, BUCHTHAL S, TAYLOR M, SCHIFITTO G, ZHONG JH, DAAR E, ALGER J, SINGER E, CAMPBELL T, YIANNOUTSOS C, COHEN R, NAVIA B & CONSORTIUM HN 2011. Persistence of HIV-associated cognitive impairment, inflammation, and neuronal injury in era of highly active antiretroviral treatment. Aids, 25, 625–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEATON RK, CLIFFORD DB, FRANKLIN DR JR., WOODS SP, AKE C, VAIDA F, ELLIS RJ, LETENDRE SL, MARCOTTE TD, ATKINSON JH, RIVERA-MINDT M, VIGIL OR, TAYLOR MJ, COLLIER AC, MARRA CM, GELMAN BB, MCARTHUR JC, MORGELLO S, SIMPSON DM, MCCUTCHAN JA, ABRAMSON I, GAMST A, FENNEMA-NOTESTINE C, JERNIGAN TL, WONG J, GRANT I & GROUP C 2010. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology, 75, 2087–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEATON RK, FRANKLIN DR, ELLIS RJ, MCCUTCHAN JA, LETENDRE SL, LEBLANC S, CORKRAN SH, DUARTE NA, CLIFFORD DB, WOODS SP, COLLIER AC, MARRA CM, MORGELLO S, MINDT MR, TAYLOR MJ, MARCOTTE TD, ATKINSON JH, WOLFSON T, GELMAN BB, MCARTHUR JC, SIMPSON DM, ABRAMSON I, GAMST A, FENNEMA-NOTESTINE C, JERNIGAN TL, WONG J, GRANT I & GRP CH 2011. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders before and during the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: differences in rates, nature, and predictors. Journal of Neurovirology, 17, 3–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEATON RK, MARCOTTE TD, MINDT MR, SADEK J, MOORE DJ, BENTLEY H, MCCUTCHAN JA, REICKS C, GRANT I & GROUP H 2004a. The impact of HIV-associated neuropsychological impairment on everyday functioning. J Int Neuropsychol Soc, 10, 317–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEATON RK, MILLER SW, TAYLOR MJ & GRANT I 2004b. Revised comprehensive norms for an expanded Halstead-Reitan Battery: Demographically adjusted neuropsychological norms for African American and Caucasian adults, Lutz, FL, Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- JMP PRO VERSION 12.0.1 1989–2007. SAS Institute Inc; Cary, NC. [Google Scholar]

- KOOIJ KW, WIT FWNM, SCHOUTEN J, VAN DER VALK M, GODFRIED MH, STOLTE IG, PRINS M, FALUTZ J, REISS P & GRP ACS 2016. HIV infection is independently associated with frailty in middle-aged HIV type 1-infected individuals compared with similar but uninfected controls. Aids, 30, 241–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEE Y, KIM J, CHON D, LEE KE, KIM JH, MYEONG S & KIM S 2018. The effects of frailty and cognitive impairment on 3-year mortality in older adults. Maturitas, 107, 50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCARTHUR JC, MCDERMOTT MP, MCCLERNON D, ST HILLAIRE C, CONANT K, MARDER K, SCHIFITTO G, SELNES OA, SACKTOR N, STERN Y, ALBERT SM, KIEBURTZ K, DEMARCAIDA JA, COHEN B & EPSTEIN LG 2004. Attenuated central nervous system infection in advanced HIV/AIDS with combination antiretroviral therapy. Archives of Neurology, 61, 1687–1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MITNITSKI A, FALLAH N, ROCKWOOD MRH & ROCKWOOD K 2011. Transitions in cognitive status in relation to frailty in older adults: A Comparison of three frailty measures. Journal of Nutrition Health & Aging, 15, 863–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONTOYA JL, JANKOWSKI CM, O’BRIEN KK, WEBEL AR, OURSLER KK, HENRY BL, MOORE DJ & ERLANDSON KM 2019. Evidence-informed practical recommendations for increasing physical activity among persons living with HIV. AIDS, 33, 931–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOORE DJ, MASLIAH E, RIPPETH JD, GONZALEZ R, CAREY CL, CHERNER M, ELLIS RJ, ACHIM CL, MARCOTTE TD, HEATON RK & GRANT I 2006. Cortical and subcortical neurodegeneration is associated with HIV neurocognitive impairment. Aids, 20, 879–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOORE RC, HUSSAIN MA, WATSON CW, FAZELI PL, MARQUINE MJ, YARNS BC, JESTE DV & MOORE DJ 2018. Grit and Ambition are Associated with Better Neurocognitive and Everyday Functioning Among Adults Living with HIV. AIDS Behav, 22, 3214–3225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MUTHÉN LK & MUTHÉN BO 1998-2012. Mplus User’s Guide, Los Angeles, CA, Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- NESSELROADE J, STIGLER S & BALTES P 1980. Regression toward the mean and the study of change. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 622. [Google Scholar]

- NEWMAN AB, GOTTDIENER JS, MCBURNIE MA, HIRSCH CH, KOP WJ, TRACY R, WALSTON JD, FRIED LP & CARDIOVASCULAR HEALTH STUDY RESEARCH, G. 2001. Associations of subclinical cardiovascular disease with frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 56, M158–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NORMAN MA, MOORE DJ, TAYLOR M, FRANKLIN D JR., CYSIQUE L, AKE C, LAZARRETTO D, VAIDA F, HEATON RK & GROUP H 2011. Demographically corrected norms for African Americans and Caucasians on the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised, Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised, Stroop Color and Word Test, and Wisconsin Card Sorting Test 64-Card Version. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol, 33, 793–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ONEN NF, OVERTON ET, SEYFRIED W, STUMM ER, SNELL M, MONDY K & TEBAS P 2010. Aging and HIV Infection: A Comparison Between Older HIV-Infected Persons and the General Population. Hiv Clinical Trials, 11, 100–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OPPENHEIM H, PAOLILLO EW, MOORE RC, ELLIS RJ, LETENDRE SL, JESTE DV, GRANT I, MOORE DJ & HIV NEUROBEHAVIORAL RESEARCH PROGRAM 2018. Neurocognitive functioning predicts frailty index in HIV. Neurology, 91, e162–e170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PREVENTION, C. F. D. C. A. 2018. HIV Among People Aged 50 and Older [Online]. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/age/olderamericans/index.html [Accessed].

- PUTS MTE, TOUBASI S, ANDREW MK, ASHE MC, PLOEG J, ATKINSON E, AYALA AP, ROY A, RODRIGUEZ MONFORTE M, BERGMAN H & MCGILTON K 2017. Interventions to prevent or reduce the level of frailty in community-dwelling older adults: a scoping review of the literature and international policies. Age Ageing, 46, 383–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PUTS MTE, VISSER M, TWISK JWR, DEEG DJH & LIPS P 2005. Endocrine and inflammatory markers as predictors of frailty. Clinical Endocrinology, 63, 403–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RABKIN JG 2008. HIV and depression: 2008 review and update. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep, 5, 163–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAJI MA, AL SNIH S, OSTIR GV, MARKIDES KS & OTTENBACHER KJ 2010. Cognitive Status and Future Risk of Frailty in Older Mexican Americans. Journals of Gerontology Series a-Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 65, 1228–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RIZZOLI R, REGINSTER JY, ARNAL JF, BAUTMANS I, BEAUDART C, BISCHOFF-FERRARI H, BIVER E, BOONEN S, BRANDI ML, CHINES A, COOPER C, EPSTEIN S, FIELDING RA, GOODPASTER B, KANIS JA, KAUFMAN JM, LASLOP A, MALAFARINA V, MANAS LR, MITLAK BH, OREFFO RO, PETERMANS J, REID K, ROLLAND Y, SAYER AA, TSOUDEROS Y, VISSER M & BRUYERE O 2013. Quality of life in sarcopenia and frailty. Calcif Tissue Int, 93, 101–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROBERTSON DA, SAVVA GM, COEN RF & KENNY RA 2014. Cognitive function in the prefrailty and frailty syndrome. J Am Geriatr Soc, 62, 2118–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROBERTSON DA, SAVVA GM & KENNY RA 2013. Frailty and cognitive impairment--a review of the evidence and causal mechanisms. Ageing Res Rev, 12, 840–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROCKWOOD K & MITNITSKI A 2007. Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 62, 722–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROONEY AS, MOORE RC, PAOLILLO EW, GOUAUX B, UMLAUF A, LETENDRE SL, JESTE DV, MOORE DJ & PROGRAM HIVNR 2019. Depression and aging with HIV: Associations with health-related quality of life and positive psychological factors. J Affect Disord, 251, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUBIN LH, SUNDERMANN EE & MOORE DJ 2019. The current understanding of overlap between characteristics of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders and Alzheimer’s disease. LID - 10.1007/s13365-018-0702-9 [doi]. Journal of Neurovirology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUBTSOVA AA, MARQUINE MJ, DEPP C, HOLSTAD M, ELLIS RJ, LETENDRE S, JESTE DV & MOORE DJ 2018. Psychosocial Correlates of Frailty Among HIV-Infected and HIV-Uninfected Adults. Behav Med, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SLAETS JP 2006. Vulnerability in the elderly: frailty. Med Clin North Am, 90, 593–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMIT M, BRINKMAN K, GEERLINGS S, SMIT C, THYAGARAJAN K, SIGHEM A, DE WOLF F, HALLETT TB & COHORT AO 2015. Future challenges for clinical care of an ageing population infected with HIV: a modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis, 15, 810–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOYSAL P, VERONESE N, THOMPSON T, KAHL KG, FERNANDES BS, PRINA AM, SOLMI M, SCHOFIELD P, KOYANAGI A, TSENG PT, LIN PY, CHU CS, COSCO TD, CESARI M, CARVALHO AF & STUBBS B 2017. Relationship between depression and frailty in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev, 36, 78–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VALCOUR V, SHIKUMA C, SHIRAMIZU B, WATTERS M, POFF P, SELNES O, HOLCK P, GROVE J & SACKTOR N 2004. Higher frequency of dementia in older HIV-1 individuals: the Hawaii Aging with HIV-1 Cohort. Neurology, 63, 822–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAUGHAN L, CORBIN AL & GOVEAS JS 2015. Depression and frailty in later life: a systematic review. Clin Interv Aging, 10, 1947–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALLACE LMK, FERRARA M, BROTHERS TD, GARLASSI S, KIRKLAND SA, THEOU O, ZONA S, MUSSINI C, MOORE D, ROCKWOOD K & GUARALDI G 2017. Lower Frailty Is Associated with Successful Cognitive Aging Among Older Adults with HIV. Aids Research and Human Retroviruses, 33, 157–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALLACE LMK, THEOU O, GODIN J, ANDREW MK, BENNETT DA & ROCKWOOD K 2019. Investigation of frailty as a moderator of the relationship between neuropathology and dementia in Alzheimer’s disease: a cross-sectional analysis of data from the Rush Memory and Aging Project. Lancet Neurol, 18, 177–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION 1998. Composite Diagnositic International Interview (CIDI, version 2.1), Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]