Abstract

An integrated batch and continuous flow process has been developed for the gram-scale synthesis of goniothalamin. The synthetic route hinges upon a telescoped continuous flow Grignard addition followed by an acylation reaction capable of delivering a racemic goniothalamin precursor (16) (20.9 g prepared over 3 h), with a productivity of 7 g·h–1. An asymmetric Brown allylation protocol was also evaluated under continuous flow conditions. This approach employing (−)-Ipc2B(allyl) provided an (S)-goniothalamin intermediate in 98% yield and 91.5% enantiomeric excess (ee) with a productivity of 1.8 g·h–1. For the final step, a ring-closing metathesis reaction was explored under several conditions in both batch and flow regimes. In a batch operation, the Grubbs second-generation was shown to be effective and highly selective for the desired ring closure product over those arising from other modes of reactivity, and the reaction was complete in 1.5 h. In a flow operation, reactivity and selectivity were attenuated relative to the batch mode; however, after further optimization, the residence time could be reduced to 16 min with good selectivity and good yield of the target product. A tube-in-tube reactor was investigated for in-situ ethylene removal to favor ring-closing over cross-metathesis, in this context. These results provide further evidence of the utility of flow chemistry for organometallic processing and reaction telescoping. Using the developed integrated batch and flow methods, a total of 7.75 g of goniothalamin (1) was synthesized.

1. Introduction

Chemotherapy plays a pivotal role in cancer treatment, improving the quality of life and increasing patient survival. However, the drug resistance of antineoplastic drugs and their high toxicity are some of the limitations of the current chemotherapy treatments. Due to these reasons, drug discovery programs have made efforts to deliver new candidates with high selectivity and low off-target cytotoxicity for cancer treatment. In most cases, such new candidates are inspired by natural compounds due to their limitless chemical diversity and a broad biological profile.1 To date, more than 50% of all approved small-molecule drugs have been structurally inspired by isolated natural compounds.2 Moreover, ca. 80% of all antitumor agents used in the clinic are derived from natural products.3

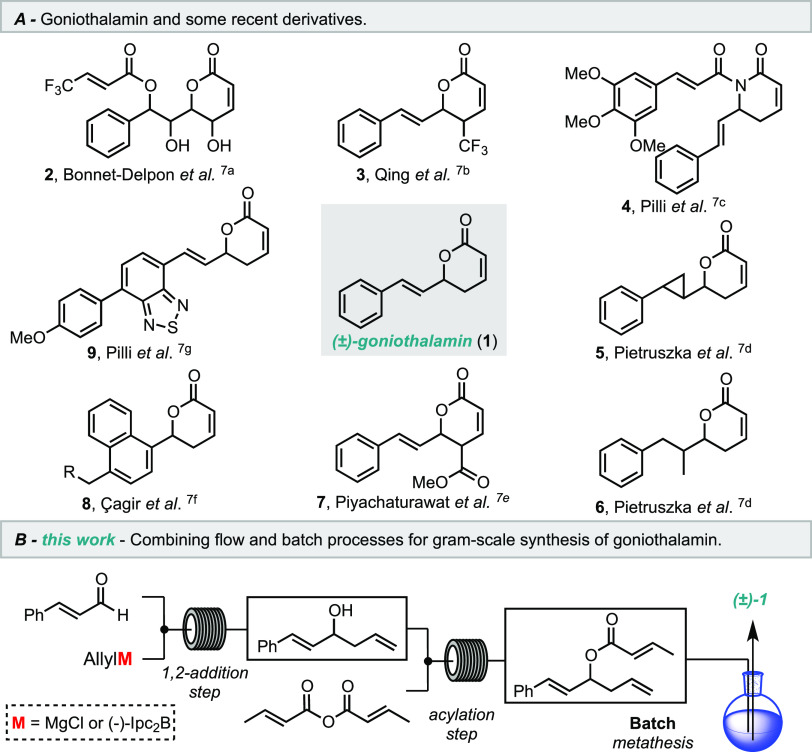

Accordingly, the natural product goniothalamin (1) has been the object of study of various medicinal chemistry programs for several years.4 Goniothalamin is a secondary metabolite obtained from the species of the genus Goniothalamus.5 This styryl lactone exhibits important antiproliferative and cytotoxic effects on several tumor cell types, such as lung, breast, kidney, prostate, liver, and leukemia.6 Due to its wide biological profile, many medicinal studies have explored goniothalamin as a chemical platform to the design of new drug candidates and to understand their in vitro mode of action (Scheme 1A).7

Scheme 1. Goniothalamin and Derivatives (A); the Proposed Study (B).

Using a solid tumor experimental model in vivo assay, our group has demonstrated that both non-natural (R)-1 and natural (S)-1, as well as its racemic-1 form, present antiedematogenic and inhibitory activity against the proliferation of Ehrlich solid tumor cells.8 No evidence for toxic effects was found, and similar activity profiles were observed for racemic-1, (R)-1, and (S)-1 against NCI-ADR/RES, NCI-460, 786-0, and U251 cancer cells.8

Concerning the synthesis of (±)-goniothalamin, we have noted the lack of studies focusing on new strategies for the gram-scale synthesis of 1. In many studies, 1 was used as a starting material for the synthesis of goniothalamin derivatives, or the same reaction sequence was employed for the preparation of new analogues,6b,7 which shows the importance of a robust and scalable method to accumulate 1. In addition, gram quantities of 1 are required for more complete and in-depth in vivo studies regarding the real potential of 1 as a drug candidate for cancer treatment. Bearing this in mind, continuous flow processing offers a great opportunity for the scaling-up of the synthesis of goniothalamin (1).

Flow chemistry has emerged in both academia and industry as a promising enabling technology for organic synthesis, providing several advantages in comparison to traditional batch processes for organic and inorganic synthesis.9 One of the most attractive benefits in a continuous flow approach is the opportunity to integrate several reaction steps (the so-called telescoped synthesis) to rapidly generate focused libraries of bioactive compounds as well as enough material for clinical trials in medicinal chemistry programs.10 Recently, our group has demonstrated the telescoped synthesis of highly substituted 3-thio-1,2,4-triazoles, including their gram-scale preparation and application to the continuous flow synthesis of an API.11 Integration of processing steps through telescoped reactions allows for the expedient preparation of target compounds since there is no need for intermediate isolation, which also leads to reduced waste generation through the reduction in solvent use.11 Indeed, the synthesis of many natural products and biologically active compounds has been the target of multistep flow chemical processes.12

In this context, we demonstrate herein an improved process for the multigram synthesis of (±)-goniothalamin (1) in a continuous flow regime (Scheme 1B). Since the racemic mixture of 1 exhibited a similar in vivo antitumor profile compared to both enantiomers and (S)-goniothalamin (S)-1 showed higher potency in vitro than (R)-1 against kidney cancer cell proliferation (786-0) with IC50 = 4 nM,6b both racemic and asymmetric routes (for the S enantiomer) were explored under continuous flow conditions.

2. Results and Discussion

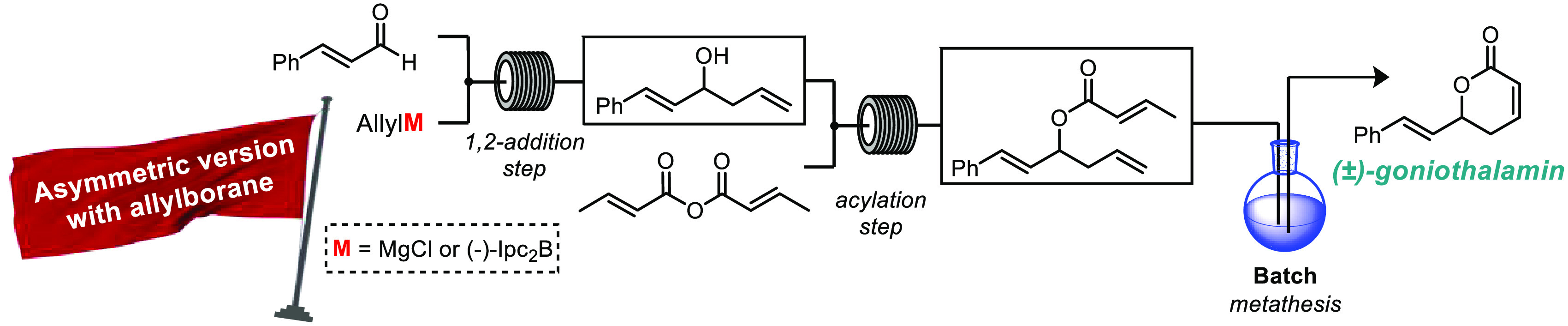

A three-step synthetic route has been used for the total synthesis of goniothalamin in the batch mode in our laboratory (Scheme 2).6a This procedure involves the addition of an ethereal solution of allylmagnesium bromide (11) to trans-cinnamaldehyde (10), followed by esterification of the secondary alcohol 12 with acryloyl chloride (13) in the presence of triethylamine to prepare the corresponding acrylate ester 14. This is followed by a ring-closing metathesis reaction using the Grubbs first-generation catalyst.

Scheme 2. Previous Synthesis of Racemic Goniothalamin (1) in the Batch Mode6a.

Reproduced with permission from Elsevier (permission number: 4858900336289).

To explore the in vivo activity of this family of dihydropyranones, this route was scaled up to provide gram quantities of goniothalamin. Although such methodology was able to secure ca. 25 g of the requisite (racemic) compound, several small-scale batch reactions were required for the ring-closing metathesis step, which did not provide acceptable yields when conducted at a large scale or at an increased concentration.8 On the practical side, manual work including several chromatographic separations and the use of large quantities of solvents were required to accumulate the requisite amount of goniothalamin for in vivo studies.8 Based on this, such a three-step batch procedure could be potentially adapted to flow conditions to afford a more easily scaled approach. Note that the desired process could not only potentially allow the preparation of goniothalamin on a multigram scale but also permit rapid access to analogues by changing the aldehyde and Grignard reagent input starting materials.

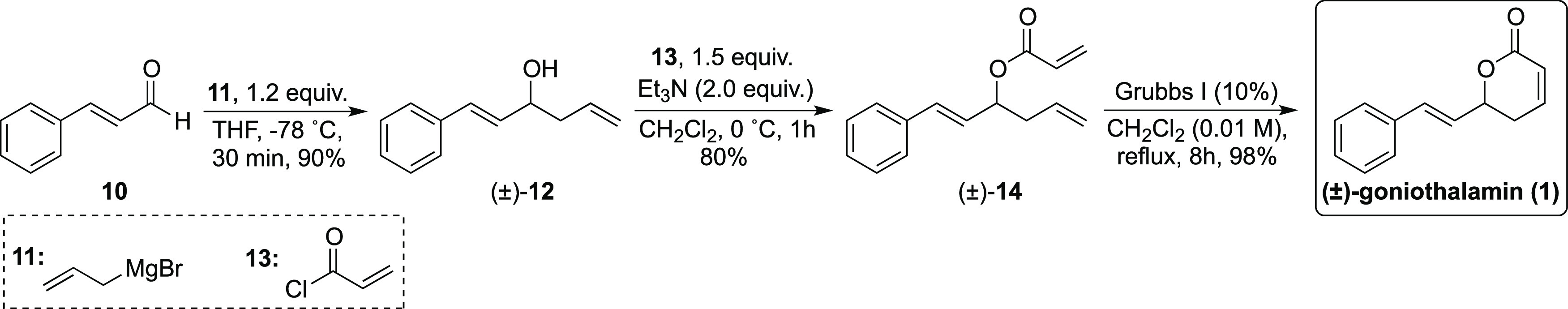

2.1. Racemic Allylation Followed by Acylation Reaction

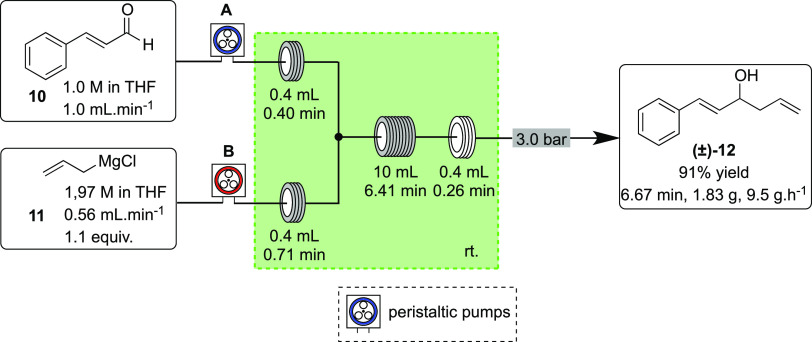

To initiate experiments under continuous flow conditions, the addition of allylmagnesium chloride (11) to trans-cinnamaldehyde (10) was investigated. This step was optimized by careful adjustment of the residence time and stoichiometry toward full conversion to alcohol 12 before the in-line introduction of the acylating agent in the following step. The optimized flow conditions to alcohol (±)-12 are presented in Scheme 3.

Scheme 3. Continuous Flow Addition of Allylmagnesium Chloride (11, Pump B) to trans-Cinnamaldehyde (10, Pump A).

A commercially available THF solution of 11 (1.97 M) and a THF solution of 10 were pumped through the flow reactor via two chemically resistant peristaltic pumps containing fluoropolymer tubes compatible with THF solutions, according to our previous work concerning the processing of organometallic reagents in a continuous flow regime.13 The organometallic reagent solution was pumped from the commercial bottle by inserting argon line through the septum seal, with no requirement for predilution or use of sample loops. Thus, Grignard reagent addition to 10 proceeded quickly at room temperature. In batch, these reactions are typically performed at low temperatures, for example, at 0 °C or below, by dropwise addition, before warming up to room temperature allowing the reaction to go to completion.6a In the continuous flow regime, cryogenic conditions were not necessary and no uncontrollable exothermic reaction was noticed, leading the reaction to achieve completion at reduced residence times and increased material productivity. Notably, while an uncontrollable exothermic process was not observed, a modest temperature increase of 3–4 °C in the reactor was noted when the cooling device of the flow system was not operating, but neither yield nor selectivity were affected when the results from processing in this way were compared with those obtained from the active temperature control (through cooling). Under the conditions shown in Scheme 3, full conversion could be obtained using only 1.1 equiv of the Grignard reagent 11. After reaching steady-state operation, during a period of ca. 11.5 min, a sample was collected and, after aqueous workup and chromatography purification, alcohol 12 was obtained in 91% yield (1.83 g) and 9.5 g h–1 productivity, with a residence time of 6.67 min at the indicated flow rates.

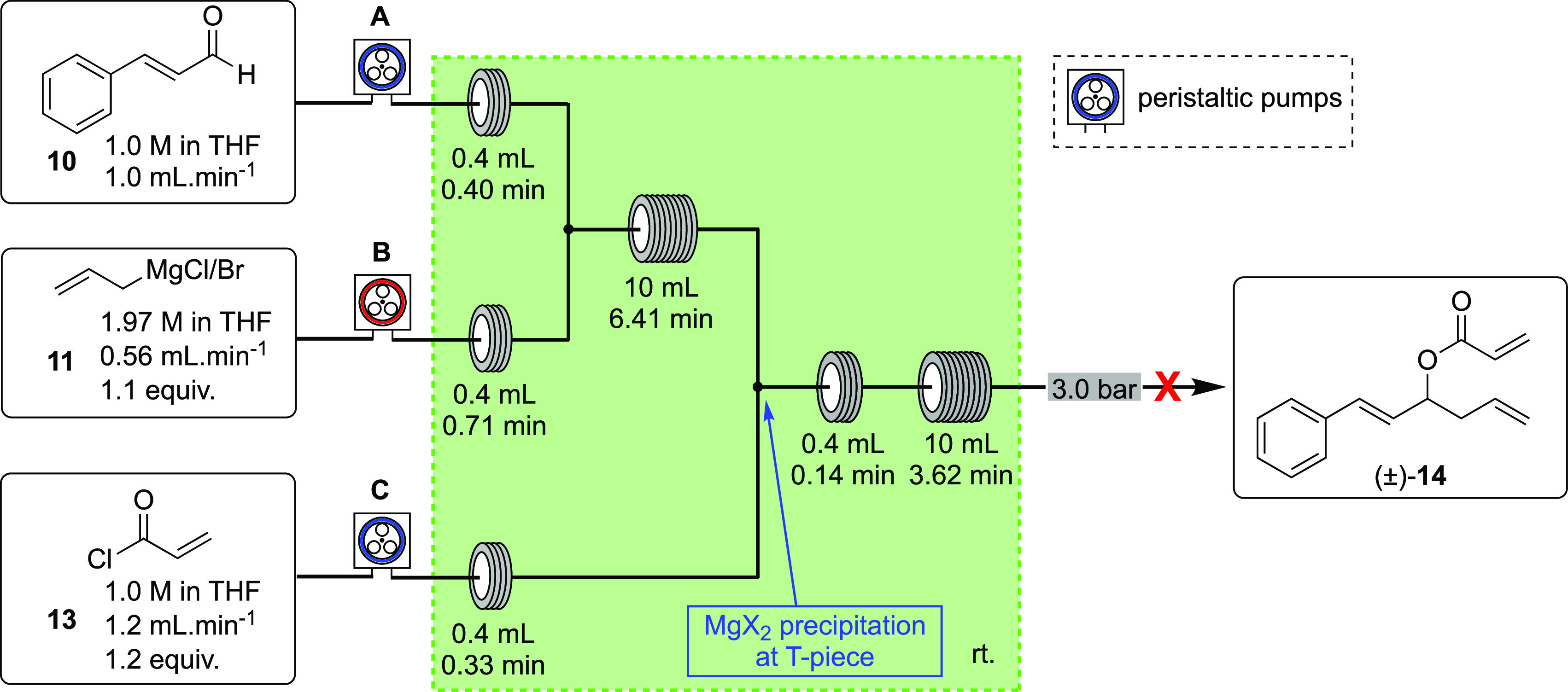

After optimizing the racemic allylation, the acylation reaction was adapted from batch to the continuous flow mode. The reaction of the secondary allylic alcohol 12 with acryloyl chloride (13) is usually conducted in the batch mode with triethylamine as base. However, the alkoxide product of the Grignard addition eliminates the need for an additional base in the acylation reaction. The output stream of the first reactor coil was combined with a THF solution of 13, and the combined stream was directed to an additional 10 mL reactor coil kept at room temperature (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4. Attempt toward Continuous Flow Addition of Allylmagnesium Chloride/Bromide (11, Pump B) to 10 (Pump A) Followed by Acylation of the Alkoxide Intermediate with Acryloyl Chloride (13, Pump C).

Unfortunately, running the reaction under the conditions depicted in Scheme 4 led to blockage of the system at the T-piece where the alkoxide output and acylating reagent mix; we hypothesized that this would be related to the precipitation of magnesium(II) chloride in the reactor coil. The same behavior was observed when allylmagnesium bromide was used instead of the corresponding chloride. Reducing the reaction concentration was explored but still led to the formation of solids at the T-piece on mixing, resulting in blockage and shutdown of the flow system.

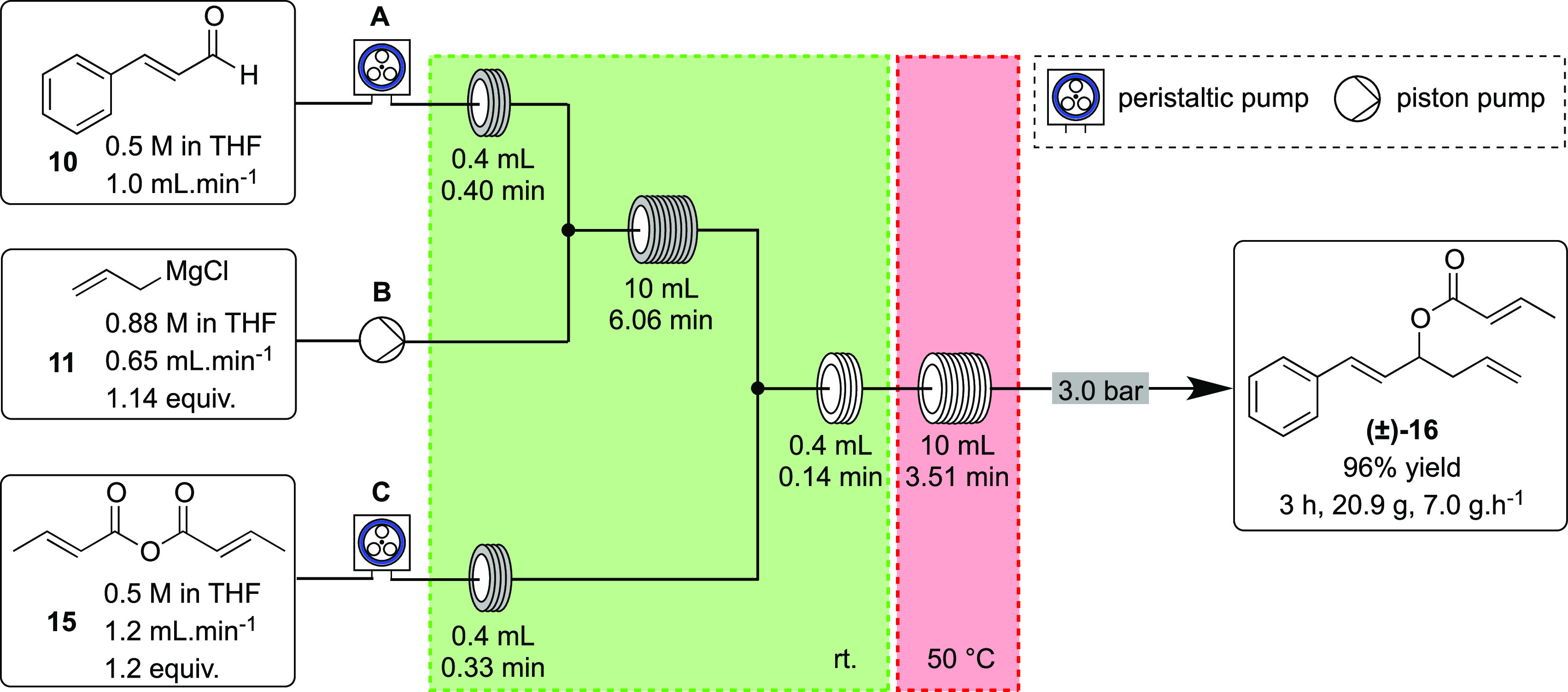

Based on our previous work on the use of organometallic reagents in the flow regime,1313 was replaced by commercially available crotonic anhydride (15) as the acylating agent, leading instead to a more soluble mixed magnesium(II) chloride acetate salt. Indeed, a THF solution of 15 was pumped at 1.2 mL min–1 by the third peristaltic pump and combined with the output stream from the first reactor coil, which contained the alkoxide intermediate. The combined stream was then directed to a second 10 mL reactor coil stabilized at 50 °C and pressurized with an appropriate back-pressure regulator. Ester 16 was obtained in full conversion under these conditions.

Although the reaction conditions were optimized for the telescoped preparation of ester 16, compatibility issues with processing this Grignard reagent solution using peristaltic pumps and supplied tubing led to irreproducible results (see Figure S1 for more details), likely due to the presence of remaining allyl chloride in the allylmagnesium chloride solution.

To overcome this issue, an external piston pump (K-120 Knauer pump) was used to deliver the allylmagnesium chloride solution, as shown in Figure S2. In this experiment, the back of the HPLC-type piston pump was purged and connected to an argon line. This measure avoids the exposure of the Grignard solution to the atmosphere and formation of solids that would result in blocking of the pumping system (see the Experimental Section for more details).

Once the flow equipment and reaction parameters, such as stoichiometry of reagents, residence time, and temperature, were optimized, the multistep process for the preparation of ester 16 was uninterruptedly run for 3 h to yield 20.9 g of the product, which was obtained in full conversion and 96% isolated yield, for 2 steps (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5. Continuous Flow Addition of Allylmagnesium Chloride (11, Pump B) to 10 (Pump A) Followed by Acylation of the Alkoxide Intermediate with Crotonic Anhydride (15, Pump C).

With the racemic synthesis of the goniothalamin intermediate (±)-16 in hand, we investigated the asymmetric allylation to produce the (R)-goniothalamin precursor.

2.2. Asymmetric Allylation Reaction

Several batch strategies have been proposed for the asymmetric synthesis of goniothalamin (1).6a,14 For example, Singh and co-workers employed an auxiliary-controlled asymmetric aldol reaction for the construction of an enantiopure homoallylic alcohol intermediate.14a Asymmetric allylboration was described by Brown and co-workers, achieving homoallylic alcohol intermediate (12) in 92–97% enantiomeric excess (ee).14b Our group has previously employed Ti(Oi-Pr)4/(R)-BINOL-mediated asymmetric allylation, leading to alcohol 12 in 78% yield and 94% ee.6a,14c Enzymatic kinetic resolution of alcohol 12 has also been demonstrated.14d

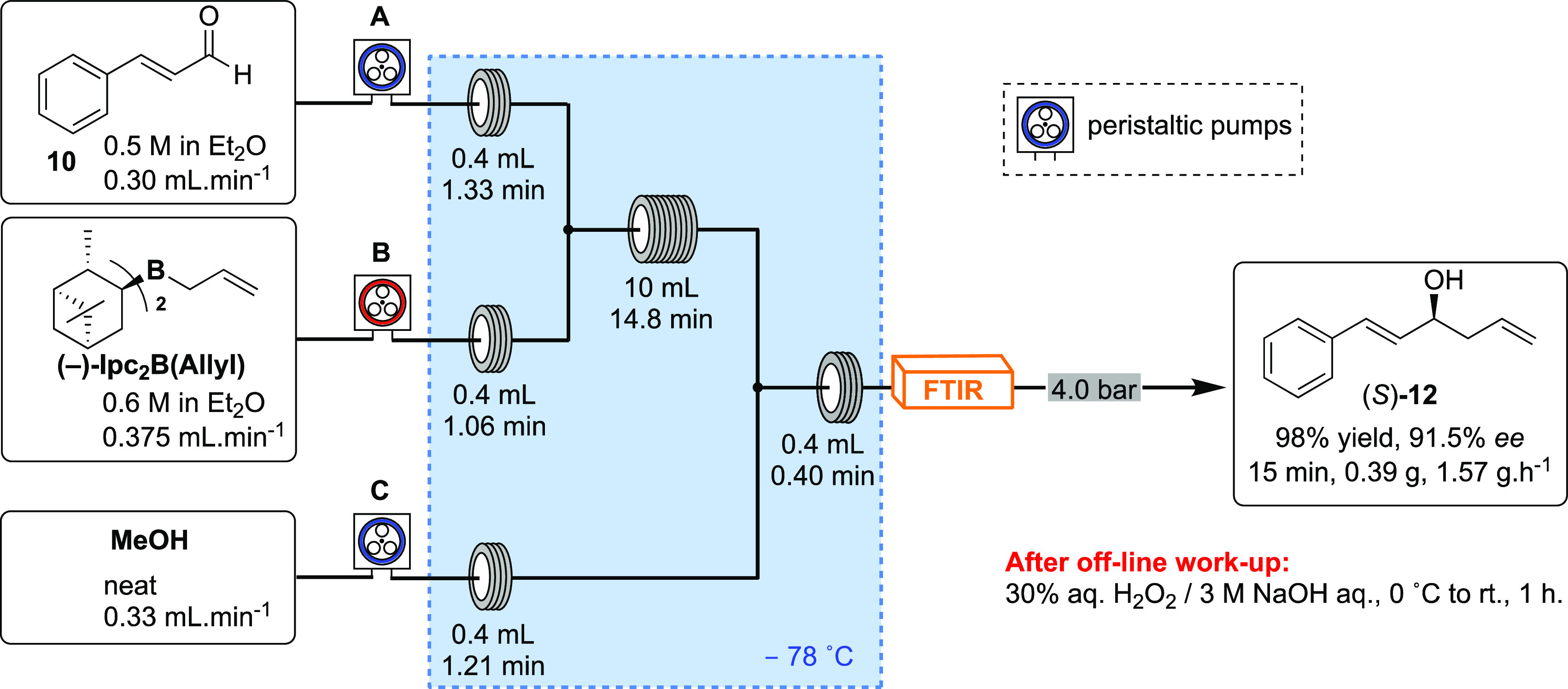

Allylboranes and boronates derived from α-pinene or diisopropyl tartrates as chiral auxiliaries have been utilized for the enantio- and diastereoselective formation of homoallylic alcohols.15 Amongst the many reported methods for asymmetric allylation, we chose to investigate these organoborane compounds in this context, in view of their straightforward preparation employing readily available starting materials and because of our continuing interest in exploring the utility of flow chemistry for organometallic synthesis. Moreover, high enantiomeric excess is usually obtained when performing asymmetric allylation using this approach.15 Based on this, both Brown (allylborane)15c and Roush (allylboronates)15e reagents were prepared and initially evaluated in batch for the asymmetric allylation of trans-cinnamaldehyde (10) (Tables S1 and S2 in the SI). The Roush allylation procedure with (+)- and (−)-diisopropyl-tartrate allyl boronate (((+)- and (−)-DIPT)B(Allyl)) afforded homoallylic alcohols (S)-12 and (R)-12 in 69–98% yield and 70.8–72.4% ee (Table S1). On the other hand, the Brown procedure with (−)-B-allyldiisopinocampheylborane ((−)-Ipc2B(Allyl)) afforded alcohol (S)-12 in 96% yield and 90.8% ee. In light of these results, the Brown approach was taken forward for optimization under continuous flow conditions (Table S3 in the SI). The optimized result is presented in Scheme 6.

Scheme 6. Continuous Flow Asymmetric Allylation of trans-Cinnamaldehyde (10, Pump A) with (−)-Ipc2B(allyl) (Pump B), Followed by In-Line Quenching with MeOH (Pump C).

During optimization, an FTIR spectrometer was placed after the coil reactor in the continuous flow system for the real-time monitoring of the conversion of 10 into (S)-12. Such an approach facilitates the reaction optimization, and (S)-12 was obtained in 98% yield and 91.5 ee with a productivity of 1.57 g·h–1. Gratifyingly, the chemical yield and the enantiomeric excess obtained under continuous flow conditions at reduced reaction times are slightly higher than those obtained in batch. Probably, more efficient mixing of a 1:1 stoichiometric mixture and improved temperature control in view of the high surface-to-volume ratio of the flow reactor could account for this superior outcome, as opposed to dropwise addition of one to the other in batch. Note that compound (S)-12 could be converted to the ester intermediate 14 or 16 and then to (S)-1 in batch using the conditions presented in Scheme 2. The need for off-line work using hydrogen peroxide under basic conditions would require an in-depth study to telescope into the acylation under these conditions, probably making use of the continuous membrane separation technology before integration of the steps.

Finally, in the last step of the synthesis, the ring-closing metathesis reaction to afford the α,β-unsaturated δ-lactone present in the structure of goniothalamin (1) was evaluated.

2.3. Ring-Closing Metathesis Reaction

Numerous immobilized Grubbs–Hoveyda catalysts for the ring-closing metathesis reaction are reported in the literature,16 including their investigation under continuous flow conditions.17 For example, Zedníc and co-workers demonstrated the metathesis of cardanol using Hoveyda–Grubbs type catalysts supported on mesoporous silica in the continuous flow regime.17a In this study, the cumulative TON in flow was significantly improved relative to the maximum TONs in a batch reactor (2500 versus 1600). The product contamination by metal leaching was also verified, and only 1.0–1.5% of ruthenium was detected in the final product. However, cardanol conversion fell over time due to catalyst deactivation. Chmielewski and co-workers showed the immobilization of ruthenium alkylidene complexes by noncovalent interactions within metal–organic frameworks (MOFs).17b Ruthenium leaching was not observed, but much lower TONs were obtained in flow compared to batch procedures (4700 versus 8900). A monolithic metathesis catalyst was prepared by Kirschning and co-workers for further use in a flow microreactor; however, it was affected by partial leaching under continuous flow conditions.17c Other examples include immobilization of Grubbs/Hoveyda catalysts on commercial silica,17d microcapillaries coated with a film of dimethylpolysiloxane soaked with the Grubbs second-generation catalyst,17e and the polystyrene-supported Grubbs second-generation catalyst.17f

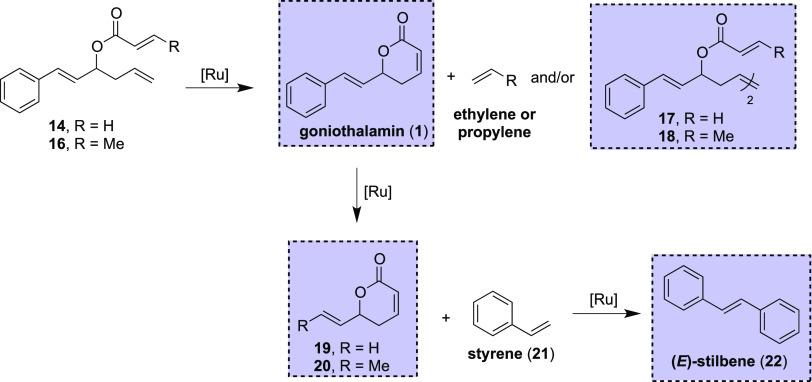

Even though the use of columns with packed immobilized catalysts could be a convenient approach to minimize postreaction manipulations, concerns such as leaching, recycling, and anchoring of immobilized ruthenium catalysts led us to focus our study on homogeneous conditions using Grubbs first- and second-generation as well as Hoveyda–Grubbs second-generation catalysts. Initially, we performed the reactions in batch to evaluate the concentration and catalyst selectivity (Table 1).

Table 1. Evaluation of the Ring-Closing Metathesis in the Batch Mode.

| entry | R | catalyst | loading (mol %) | t (h) | conversion (%)a | 1/17/19 or 1/18/20a | yield (1 + 19 or 1 + 20) (%)b | yield 17 or 18 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H | Grubbs I | 10 | 7.0 | 100 | 100:0:0 | 87 | <5 |

| 2 | H | Grubbs II | 5 | 1.5 | 100 | 97:0:3 | 90 | <5 |

| 3 | H | Hoveyda II | 5 | 1.5 | 100 | 94:0:6 | 95 | <5 |

| 4 | Me | Grubbs I | 10 | 14.0 | 96 | 20:80:0 | 19 | 75 |

| 5 | Me | Grubbs II | 5 | 1.5 | 100 | 90:0:10 | 96 | <5 |

| 6 | Me | Hoveyda II | 5 | 3.0 | 100 | 92:8:0 | 92 | 8a |

Calculated from 1H NMR of the crude.

Isolated yield for the inseparable mixture.

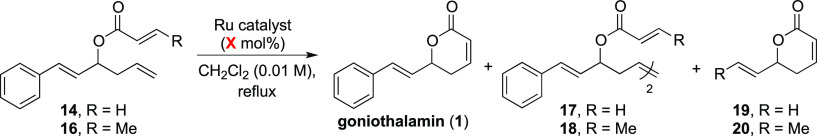

The ring-closing metathesis reaction for acrylate ester 14 is typically performed using the Grubbs first-generation catalyst, in refluxing dichloromethane and at low concentrations to circumvent the formation of dimer 17 in view of the intermolecular metathesis reaction.6a Indeed, under these conditions (Table 1, entry 1), goniothalamin (1) was obtained in good yield and selectivity from ester 14. On the other hand, the use of either Grubbs or Hoveyda–Grubbs second-generation catalysts led to the formation of goniothalamin (1) along with the vinyl lactone 19 (Table 1, entries 2 and 3), resulting from a cross-metathesis between the styryl unit of goniothalamin (1) and ethylene gas, which is generated during the ring-closing metathesis reaction (Scheme 7).

Scheme 7. Possible Reaction Pathways and Products for the Olefin Metathesis Reaction.

Compounds enclosed in the blue dotted box were isolated and characterized; see the SI.

Reactions using crotonate ester 16, with the methyl group at the acrylic unit, proved to be more complex. First, as one could expect, the use of the Grubbs first-generation catalyst gave dimer 18 as the major product with goniothalamin (1) being isolated in only 19% yield (Table 1, entry 4). Note that both goniothalamin (1) and 18 were also formed using the Hoveyda–Grubbs second-generation catalyst; nevertheless, the selectivity was reversed toward the formation of the desired product goniothalamin (1) (entry 6). Finally, the ring-closing metathesis of ester 16 carried out in the presence of the Grubbs second-generation catalyst led to the formation of goniothalamin (1) and lactone 20 in excellent combined yield (96%), obtained as a 90:10 inseparable mixture (entry 5). All additional experiments such as sparging with nitrogen gas to force the removal of ethylene from the reaction mixture, slow addition of the substrate and catalyst solutions (“infinite dilution approach”) to reduce the amount of dimer 17 or 18 formation, reflux in toluene as solvent, higher reaction concentration (up to 0.1 M), and using 1-heptene as a sacrifice olefin (to avoid lactone 19/20 formation by reaction with ethylene/propylene) proved to be unsuccessful (for more details, see Table S4).

The very low concentrations usually employed for the ring-closing metathesis reaction present an acute limitation of material productivity when operating at large/pilot scales.18 In batch, when the reaction with ester 16 was evaluated at higher reaction concentrations (0.05 and 0.1 M), a more complex mixture of dimers was observed.19 Bearing in mind the aforementioned advantages of flow chemistry over batch procedures, we sought to investigate the ring-closing metathesis reaction in a continuous flow regime. Considering that the monomeric α,β-unsaturated δ-lactone should be more thermodynamically favorable than the dimer, pushing the reaction in flow conditions to its limits could potentially convert the observed dimer into goniothalamin (1), which could enable the use of a higher concentration for this transformation. The use of a back-pressure regulator to pressurize the system allows the heating of a solvent above its boiling point, and this fact was advantageously employed in this synthesis.9

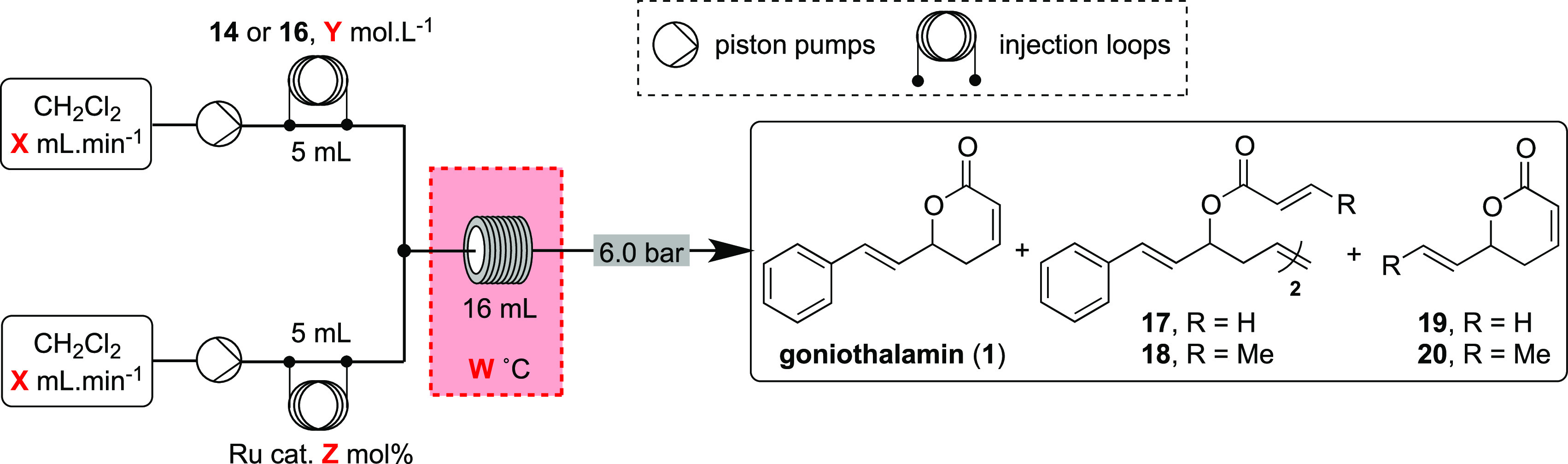

The flow setup used for the preliminary optimization experiments is shown in Figure S3. Initially, the Grubbs first-generation catalyst was evaluated in the reaction with esters 14 and 16 at 100 °C (Table 2, entries 1 and 9). Low conversion was obtained for ester 14 in 16 min of residence time. When the more active and thermally stable Grubbs second-generation catalyst was employed, full conversion was obtained even at 50 °C, but a mixture of goniothalamin (1), dimer 17, and lactone 19 was formed (entry 3). As we anticipated, increasing the temperature led to the consumption of the dimer and a mixture of 1 and lactone 19 was obtained in almost 1:1 ratio (entry 4), being isolated in 78% combined yield. The use of toluene as solvent at 150 °C (results not shown) gave essentially the same results.

Table 2. Evaluation of the Ring-Closing Metathesis toward Goniothalamin (1) under Flow Conditions.

| entry | R | conc. (M) | catalyst | loading (mol %) | T (°C) | t (min) | conv. (%)a | 1/17/19 or 1/18/20a | yield (1 + 19 or 1 + 20) (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H | 0.05 | Grubbs I | 10 | 100 | 16.0 | 23 | 100:0:0 | NDc |

| 2 | H | 0.01 | Grubbs II | 5 | 100 | 16.0 | 90 | 79:0:21 | 90 |

| 3 | H | 0.05 | Grubbs II | 5 | 50 | 16.0 | 100 | 38:44:18 | 55 |

| 4 | H | 0.05 | Grubbs II | 5 | 100 | 16.0 | 100 | 57:0:43 | 78 |

| 5 | H | 0.05 | Grubbs II | 1 | 100 | 16.0 | 55 | 83:0:17 | NDc |

| 6 | H | 0.05 | Grubbs II | 5 | 100 | 8.0 | 97 | 54:0:46 | 79 |

| 7 | H | 0.01 | Hoveyda II | 5 | 100 | 16.0 | 100 | 44:0:56 | 97 |

| 8 | H | 0.05 | Hoveyda II | 5 | 100 | 16.0 | 100 | 41:0:59 | 58 |

| 9 | Me | 0.05 | Grubbs I | 10 | 100 | 16.0 | 0 | ||

| 10 | Me | 0.01 | Grubbs II | 5 | 100 | 16.0 | 80 | 100:0:0 | 75 (1 only) |

| 11 | Me | 0.01 | Grubbs II | 5 | 100 | 32.0 | 75 | 100:0:0 | 65 (1 only) |

| 12 | Me | 0.05 | Grubbs II | 5 | 100 | 16.0 | 100 | 66:0:34 | 94 |

| 13 | Me | 0.01 | Hoveyda II | 5 | 100 | 16.0 | 100 | 83:0:17 | 91 |

| 14 | Me | 0.05 | Hoveyda II | 5 | 100 | 16.0 | 100 | 63:0:37 | 77 |

Calculated from 1H NMR of the crude.

Isolated yield for the inseparable mixture.

ND = not determined.

The formation of lactone by-product 19 in a greater extent in the flow regime is not surprising, considering that the reaction under flow conditions is performed in a closed system, thus keeping the ethylene gas in solution, which favors the olefin cross-metathesis reaction with the desired goniothalamin (1) product (entries 2–5). Hypothesizing that such reaction occurs after the ring-closing reaction, the residence time was halved (entry 6). In this instance, for shorter residence time, we observed a slightly lower conversion and the selectivity remained poor (1:1 ratio of 1 and 19). The selectivity was essentially the same when the Hoveyda–Grubbs second-generation catalyst was investigated in the RCM reaction (entries 7 and 8). Compound 19 could be converted back to goniothalamin (1) using an olefin cross-metathesis reaction with styrene. However, considering that both olefins should present the same reactivity,20 a large excess of 19 or styrene would be required in view of this nonselective cross-metathesis reaction. Indeed, Das et al. performed the synthesis of goniothalamin (1) using this strategy; however, a large excess of 19 (20 equiv) was employed.20

The reaction with ester 16 in the presence of Grubbs and Hoveyda–Grubbs second-generation catalysts yielded better selectivities (entries 10 and 13), which could be explained by the lower reactivity of the propylene by-product in the cross-metathesis reaction. Surprisingly, the reaction carried out under identical conditions, but at a lower molar concentration (entry 10, 0.01 M), afforded goniothalamin (1) as a single product, although in a lower conversion (80%). Such similar results were not observed using ester 14 (entries 2 and 4). The higher dilution combined with the lower reactivity of propylene completely suppressed the intermolecular cross-metathesis reaction. However, this reaction performed under essentially identical conditions but with a longer residence time gave comparable results, indicating that the reaction reached equilibrium.21 Finally, the selectivity was found to decrease at a higher reaction concentration of ester 16 in both Grubbs and Hoveyda–Grubbs second-generation catalysts (entries 12 and 14).

Additional olefin metathesis experiments were performed using a gas–liquid tube-in-tube flow reactor. The tube-in-tube reactor relies on the use of a semipermeable membrane (Teflon AF-2400), which allows the loading of the desired gas into the liquid stream in view of its permeation through the membrane. In the last decade, several reactions have been explored using this membrane technology.22 For example, Knapkiewicz and co-workers demonstrated homo- and heterogeneous olefin metathesis using a tube-in-tube reactor of this type.23 In this configuration, ethylene was continuously removed by connecting the reactor to a vacuum pump, and substantial improvement was perceived for macrocyclization metathesis reactions. Based on this precedent, the same strategy was evaluated for this study (Table S5). However, no improvement was observed using a tube-in-tube reactor (90 cm; 1.25 mL·min–1 flow rate) for ester 14, i.e., the same selectivity and yield compared to entry 4 in Table 2 was found using this reactor. In our case, the cyclization step is likely to be fast, meaning that the catalyst turnover is quick enough to compete with ethylene removal. Conversely, in the macrocyclization reaction, the resting state would likely be substrate bound to catalyst before cyclization, meaning ethylene has more time to be purged.

The use of sacrifice olefin (1-heptene) in the flow regime was also explored but led to no improvements (Table S5). Although all attempts to improve the selectivity of this RCM reaction at higher concentrations failed, it is worth mentioning that continuous flow processing could at least deliver significant conversions in tighter residence times than batch protocols using the same concentration.

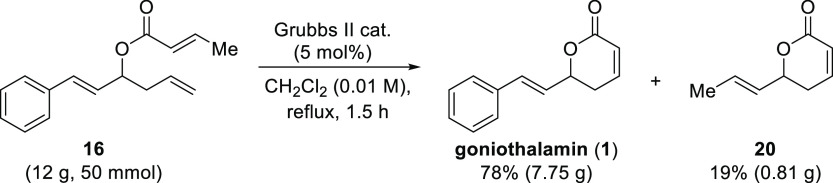

In view of the limitation imposed by the formation of the lactone by-products 19 and 20 and the high dilution issues under different flow strategies, which in turn presents a constraint for throughput and productivity, we decided to perform the final step in the synthesis of goniothalamin (1) on a preparative scale in the batch mode (Scheme 8). For this reaction, a 12 g sample of ester 16 was employed in the ring-closing metathesis reaction using the Grubbs second-generation catalyst. The reaction was performed with sparging of nitrogen gas and heated to reflux in dichloromethane. Full conversion of the substrate was observed after 1.5 h of reaction, and the target product was isolated in 78% yield (7.75 g). However, lactone 20 was also isolated in 19% yield.24 In comparison to the same reaction performed at 1 mmol scale (Table 1, entry 5), the overall chemical yield was similar; however, the selectivity was affected by the less efficient elimination of the propylene gas from the reaction mixture, in view of the poorer surface area-to-volume ratio that occurs in a larger batch vessel (10 L) under conventional magnetic stirring. Although good quantities of the desired compound could be obtained, this result highlights the current limitations of our synthetic approach and equipment capabilities as far as scale-up is concerned.

Scheme 8. Preparative-Scale Synthesis of Goniothalamin (1) in the Batch Mode.

As new reactor technologies emerge, the synthesis and preparation of chemicals of interest should be re-evaluated to look for more streamlined approaches;25 herein, our current best route to goniothalamin (1) consists of two flow steps followed by a batch process.

3. Conclusions

In summary, the synthesis of the styryl lactone goniothalamin (1) was investigated in a continuous flow regime. The 1,2-addition of the Grignard reagent to trans-cinnamaldehyde (10) and the acylation reaction of the resulting allylic alcohol 12 could be combined in a telescoped process leading to the formation of ester 16 in 96% yield, for two steps. Running this sequence by continuously pumping the starting materials over a period of 3 h led to the preparation of 20.9 g of material, giving a productivity of 7 g·h–1. An asymmetric Brown allylation reaction was also demonstrated in a continuous flow, leading to excellent yield (98%) and ee (91.5%) for (S)-12. The ring-closing metathesis reaction was evaluated in batch and flow conditions using three different ruthenium catalysts. In the batch mode, the reaction could be performed with good to excellent selectivities to give goniothalamin (1) in excellent yield (up to 96%). The use of the Grubbs second-generation catalyst proved to be very efficient, and the reaction time decreased from 7 to 1.5 h in comparison to the use of the Grubbs first-generation catalyst, even at lower catalyst loadings.

Even though full conversion could be obtained in a short residence time under continuous flow conditions, selectivity and yield were negatively affected due to the entrapment of ethylene or propylene. In the closed flow system, the evolving gases underwent an olefin cross-metathesis reaction with the styryl moiety of goniothalamin (1) affording lactones 19 or 20, in up to a 1:1 molar ratio. Different flow strategies, including a tube-in-tube reactor for ethylene/propylene removal and sacrifice of olefin, were unsuccessfully employed. On the other hand, good yield and selectivity could be achieved in flow at reduced residence times at the cost of incomplete conversion (16 min, 80% conversion, and 75% yield) using a more dilute solution. In view of the formation of by-products and high dilution issues, which in turn presents a limitation for throughput and productivity, a preparative-scale synthesis of goniothalamin (1) was performed under the optimized batch conditions. In this way, 7.75 g of goniothalamin (1) was obtained in 78% yield. Our work demonstrates that the combination of batch and continuous flow processes is a useful strategy when one or more steps of a target molecule can be maximized in terms of selectivity and yield.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Materials and Methods

Reagents were obtained from commercial sources and used as received unless otherwise stated. All reactions were carried out with anhydrous solvents, oven-dried glassware (200 °C), and manipulated under an argon atmosphere unless otherwise stated. Tetrahydrofuran (THF) was freshly distilled under argon from sodium/benzophenone ketyl prior to use. Allylmagnesium chloride, at a concentration of 2.0 M in THF, was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and titrated before its use. When necessary, dilution was performed by the addition of anhydrous THF. Compounds 1, 12, and 16 were purified by flash column chromatography using a Biotage Isolera system using prepacked silica gel 60 Å cartridges. TLC analysis was performed utilizing 0.25 mm plates precoated with silica gel 60 UV254, with the compounds being visualized by the use of UV light and/or aqueous potassium permanganate dip when appropriate. 1H NMR and 13C NMR data were recorded on a Bruker Avance (400 MHz for 1H and 100 MHz for 13C NMR) spectrometer using the residual solvent peak as the internal reference (CDCl3 = 7.26 ppm for 1H and 77.0 ppm for 13C). The data are reported as follows: chemical shift in ppm (δ), multiplicity (s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, quint = quintet, m = multiplet, br = broad signal, or combinations of thereof), coupling constant (Hz), integration. Enantiomeric excess (% ee) for Roush and Brown allylation reactions was determined by chiral HPLC: 99:01 n-hexanes/i-PrOH, CHIRALPAK AD-H, 0.9 mL·min–1, 46 and 49 min.

Reactors and interconnecting lines were constructed using a PFA polymer tubing of 1.0 mm i.d., the exception being the fluoropolymer peristaltic tubes, which were supplied by Vapourtec. Most of the experiments were carried out using a Vapourtec E-series flow system and the cooled reactor assembly, except for the preparation of compound 16, where an external pump (K-120 Knauer pump) was used to deliver the Grignard Reagent. A Uniqsis FlowSyn System was used in the study of the RCM reaction. Please see the SI for pictures of the flow equipment and setups discussed and used.

For setting up the peristaltic flow system for each experiment and cleaning down afterward, we followed the general protocol reported in our previous study on the pumping of organometallic reagents.13a

4.2. Continuous Flow Synthesis of (E)-1-Phenylhexa-1,5-dien-3-ol (12)

The flow system was set up according to Scheme 3. A 1.0 M solution of trans-cinnamaldehyde (10) in anhydrous THF (100 mL), under argon, was combined at a T-piece with a 1.97 M solution of allylmagnesium chloride (11) in anhydrous THF (100 mL), under the flow rates indicated in Scheme 3. The combined stream was passed through a coil reactor (10 mL) kept at 25 °C with continuous cooling and pressurized by a 75 psi back-pressure regulator. After the steady-state operation, the output stream was collected over 11.5 min into a conical flask containing a saturated aqueous ammonium chloride solution (50 mL) at room temperature under stirring. The collected material was transferred to a separatory funnel, and the aqueous phase was extracted with diethyl ether (3 × 50 mL). The combined organic phase was dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated to dryness. The crude product was subjected to flash column chromatography on silica using the Biotage autocolumn system, eluting in 5–10% ethyl acetate/petroleum ether 40–60 to give alcohol 12 in 91% yield (1.83 g), obtained as a colorless viscous oil.

4.3. Telescoped Synthesis of (E)-((E)-1-Phenylhexa-1,5-dien-3-yl) but-2-enoate (16)

4.3.1. Procedure A: Using the Vapourtec E-Series (Pumps A–C)

The flow system was set up according to Scheme 5. A 0.5 M solution of trans-cinnamaldehyde (10) in anhydrous THF (250 mL), under argon, was combined at a T-piece with a 0.89 M solution of allylmagnesium chloride (11) in anhydrous THF (250 mL). The combined stream was passed through a PFA reactor coil (10 mL) kept at 25 °C with continuous cooling. The output stream was combined in-line at a T-piece with a 0.5 M solution of crotonic anhydride in anhydrous THF (250 mL). The new combined stream was passed through a second PAF reactor coil (10 mL) held at 50 °C, and the whole system was pressurized by a 75 psi back-pressure regulator. The three solutions were pumped at the flow rates indicated in Scheme 5. After the steady-state operation, the output stream was collected over 10 min into a conical flask containing a saturated aqueous ammonium chloride solution (100 mL) at room temperature under stirring. The collected material was transferred to a separatory funnel, and the aqueous phase was extracted with diethyl ether (3 × 30 mL). The combined organic phase was dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated to dryness. The crude product was subjected to flash column chromatography on silica using the Biotage autocolumn system, eluting in 4–30% ethyl acetate/petroleum ether 40–60, to afford ester 16 in 73% yield (0.89 g), obtained as a light-yellow oil.

4.3.2. Procedure B: Using the Vapourtec E-Series (Pumps A and C) and the K-120 Knauer Pump

The flow system was set up according to Scheme 5. A 0.5 M solution of trans-cinnamaldehyde (10) in anhydrous THF (250 mL), under argon, was combined at a T-piece with a 0.88 M solution of allylmagnesium chloride (11) in anhydrous THF (100 mL). The combined stream was passed through a PFA reactor coil (10 mL) kept at 25 °C with continuous cooling. The output stream was combined in-line at a T-piece with a 0.5 M solution of crotonic anhydride in anhydrous THF (250 mL). The new combined stream was passed through a second PAF reactor coil (10 mL) held at 50 °C, and the whole system was pressurized by a 75 psi back-pressure regulator. The three solutions were pumped at the flow rates indicated in Scheme 5. After the steady-state operation, the output stream was collected over 3 h into a conical flask containing a saturated aqueous ammonium chloride solution (400 mL) at room temperature under stirring. The collected material was transferred to a separatory funnel, and the aqueous phase was extracted with diethyl ether (2 × 200 mL). The combined organic phase was dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated to dryness. The crude product was subjected to flash column chromatography on silica using the Biotage autocolumn system, eluting in 1–30% ethyl acetate/petroleum ether 40–60, to afford ester 16 in 96% yield (20.9 g), obtained as a light-yellow oil.

4.4. Procedure for the Continuous Flow Asymmetric Allylborane Addition to trans-Cinnamaldehyde (10)

The flow system was set up according to Scheme 6, and the reactor assembly was kept at −78 °C, due to the exothermic reaction. A 0.5 M solution of trans-cinnamaldehyde (10) in anhydrous Et2O (100 mL), under argon, was combined at a T-piece with a 0.6 M solution of (−)-B-allyldiisopinocamphenylborane in anhydrous Et2O (100 mL). The combined stream was passed through a PFA reactor coil (10 mL) kept at −78 °C with continuous cooling. The output stream of the reactor was combined in-line with neat MeOH (250 mL), and the whole system was pressurized by a 100 psi back-pressure regulator. The three solutions were pumped at the flow rates indicated in Scheme 6. After the steady-state operation, the output stream was collected over 15 min into a round-bottomed flask (50 mL) containing 10 mL of 30% aq H2O2/3 M NaOH aq at 0 °C under stirring. Next, the resulting solution was warmed up to rt over 1 h. The collected material was transferred to a separatory funnel, and the aqueous phase was extracted with diethyl ether (3 × 50 mL). The combined organic phase was dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated to dryness. The crude product was subjected to flash column chromatography on silica using the Biotage autocolumn system, eluting in 5–10% ethyl acetate/petroleum ether 40–60, to afford the alcohol (S)-12 in 98% yield (391.5 mg), obtained as a colorless viscous oil.

4.5. Segmented Continuous Flow Ring-Closing Metathesis Reaction

Procedure for the flow preparation of goniothalamin (1) (exemplified for entry 12, Table 2).

The Uniqsis FlowSyn reactor was fitted with two 5 mL injection loopings and attached to a PFA reactor coil (16 mL, 1.0 mm i.d.), which was placed on a heating block. The system was primed with CH2Cl2 at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min per channel and the temperature was set to 100 °C. A solution of ester 16 in dry CH2Cl2 (0.1 M, 0.5 mmol, 5.0 mL) and a solution of Grubbs second-generation catalyst in dry CH2Cl2 (5 mol %, 0.025 mmol, 5 mL) were loaded into two 5 mL injection loopings (injection loopings A and B, Figure S3). To initiate, injection loopings A and B were simultaneously inserted into the main flow stream via a T-piece connector at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min per channel. The combined stream was then directed through a PFA reactor coil (16 mL, 1.0 mm i.d.), which was maintained at 100 °C, giving a residence time of 16 min. After exiting the system via a BPR (6.0 bar), the output stream was collected during 30 min in a conical flask. The solution was passed through a plug of silica flash, and the volatiles were removed under vacuum. The crude product was subjected to flash column chromatography on silica using the Biotage autocolumn system, eluting in 20–60% ethyl acetate/petroleum ether 40–60, to afford an inseparable mixture of goniothalamin (1) and lactone 20 in 94% combined yield.

4.6. Procedure for the Batch Preparation of Goniothalamin (1)

To a solution of ester 16 (50 mmol) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (5.0 L, 0.01 M) was added the Grubbs second-generation catalyst (5 mol %, 2.5 mmol, 2.1 g). After 1.5 h under reflux, the reaction was allowed to cool down to room temperature, DMSO (50 equiv relative to the catalyst) was added, and the mixture was kept under these conditions overnight. After that, the volatiles were removed under vacuum and the crude product was subjected to flash column chromatography (petroleum ether 40–60/ethyl acetate 3:1, 2:1, and 1:1 v/v) to afford goniothalamin (1) in 78% yield (7.75 g) and lactone 20 in 19% yield (0.81 g).

Acknowledgments

We thank FAPESP (Award no. 2014/26378-2 and 2012/05909-4, J.C.P.; Award no. 2013/07607-8, R.A.P.), Pfizer (P.R.D.M.), the EPSRC (Award no. EP/K009494/1, D.L.B.), CAPES (R.S.G. and G.A.B.), and the BP 1702 Professorship (S.V.L.).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c02390.

1H and 13C NMR spectra, flow setup pictures, and optimization procedures can be found (PDF)

Author Present Address

§ School of Pharmacy, UCL, 29–39 Brunswick Square, London WC1N 1AX, UK. Email: duncan.browne@ucl.ac.uk.

Author Present Address

∥ Department of Chemistry, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey 08544, United States. Email: prmurray@princeton.edu.

Author Contributions

This manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Thomford N. E.; Senthebane D. A.; Rowe A.; Munro D.; Seele P.; Maroyi A.; Dzobo K. Natural Products for Drug Discovery in the 21st Century: Innovations for Novel Drug Discovery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1578–1607. 10.3390/ijms19061578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Newman D. J.; Cragg G. M. Natural Products As Sources of New Drugs over the 30 Years from 1981 to 2010. J. Nat. Prod. 2012, 75, 311–355. 10.1021/np200906s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman D. J.; Cragg G. M. Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs From 1981 to 2014. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 629–661. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b01055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral R. G.; dos Santos S. A.; Andrade L. N.; Severino P.; Carvalho A. A. Natural Products as Treatment against Cancer: A Historical and Current Vision. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 4, 1562–1567. [Google Scholar]

- For a recent review on the isolation, synthesis and biological activities of goniothalamin-related styryl lactones, see:Pilli R. A.; de Toledo I.; Meirelles M. A.; Grigolo T. A. Goniothalamin-Related Styryl Lactones: Isolation, Synthesis, Biological Activity and Mode of Action. Curr. Med. Chem. 2019, 26, 7372–7451. 10.2174/0929867325666181009161439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a For the isolation of the (R)-goniothalamin, see:Hlubucek J. R.; Robertson A. V. (+)-(5S)-δ-Lactone of 5-hydroxy-7-phenylhepta-2,6-dienoic acid, a natural product from Cryptocarya caloneura (Scheff.) Kostermans. Aust. J. Chem. 1967, 20, 2199–2206. 10.1071/CH9672199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b For the isolation of the (S)- goniothalamin, see:Liou J.-R.; Wu T.-Y.; Thang T. D.; Hwang T. L.; Wu C. C.; Cheng Y. B.; Chiang M. Y.; Lan Y. H.; El-Shazly M.; Wu S. L.; Beerhues L.; Yuan S. S.; Hou M. F.; Chen S. L.; Chang F. R.; Wu Y. C. J. Bioactive 6S-Styryllactone Constituents of Polyalthia parviflora. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 2626–2632. 10.1021/np5004577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a de Fátima Â.; Kohn L. K.; Antonio M. A.; de Carvalho J. E.; Pilli R. A. (R)-Goniothalamin: Total Syntheses and Cytotoxic Activity Against Cancer Cell Lines. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005, 13, 2927–2933. 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b de Fátima Â.; Kohn L. K.; de Carvalho J. E.; Pilli R. A. Cytotoxic activity of (S)-goniothalamin and analogues against human cancer cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 622–631. For antiproliferative activities against lung and liver cell lines, see 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Chiu C.-C.; Liu P.-L.; Huang K.-J.; Wang H.-M.; Chang K.-F.; Chou C.-K.; Chang F.-R.; Chong I.-W.; Fang K.; Chen J.-S.; Chang H.-W.; Wu Y.-C. Goniothalamin Inhibits Growth of Human Lung Cancer Cells through DNA Damage, Apoptosis, and Reduced Migration Ability. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 4288–4293. 10.1021/jf200566a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Al-Qubaisi M.; Rozita R.; Yeap S.-K.; Omar A.-R.; Ali A.-M.; Alitheen N. B. Selective Cytotoxicity of Goniothalamin against Hepatoblastoma HepG2 Cells. Molecules 2011, 16, 2944–2959. 10.3390/molecules16042944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Dumitrescu L.; Huong D. T. M.; Hung N. V.; Crousse B.; Bonnet-Delpon D. Synthesis and cytotoxic activity of fluorinated analogues of Goniothalamus lactones. Impact of fluorine on oxidative processes. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 45, 3213–3218. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Chen J-L.; You Z-W.; Qing F-L. Total synthesis of γ-trifluoromethylated analogs of goniothalamin and their derivatives. J. Fluorine Chem. 2013, 155, 143–150. 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2013.07.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Barcelos R. C.; Pelizzaro-Rocha K. J.; Pastre J. C.; Dias M. P.; Ferreira-Halder C. V.; Pilli R. A. A new goniothalamin N-acylated aza-derivative strongly downregulates mediators of signaling transduction associated with pancreatic cancer aggressiveness. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 87, 745–758. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.09.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Weber A.; Döhl K.; Sachs J.; Nordschild A. C. M.; Schröder D.; Kulik A.; Fischer T.; Schmitt L.; Teusch N.; Pietruszka J. Synthesis and cytotoxic activities of goniothalamins and derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2017, 25, 6115–6125. 10.1016/j.bmc.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Boonmuen N.; Thongon N.; Chairoungdua A.; Suksen K.; Pompimon W.; Tuchinda P.; Reutrakul V.; Piyachaturawat P. 5-Acetyl Goniothalamin Suppresses Proliferation of Breast Cancer Cells via Wnt/β-catenin Signaling. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 791, 455–464. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Kanbur T.; Kara M.; Kutluer M.; Sen A.; Delman M.; Alkan A.; Otas H. O.; Akçok I.; Çagır A. CRM1 inhibitory and antiproliferative activities of novel 4′-alkyl substituted klavuzon derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2017, 25, 4444–4451. 10.1016/j.bmc.2017.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Raitz I.; de Souza Filho R. Y.; Andrade L. P.; Correa J. R.; Neto B. A. D.; Pilli R. A. Preferential Mitochondrial Localization of a Goniothalamin Fluorescent Derivative. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 3774–3784. 10.1021/acsomega.7b00416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilli R. A.; de Carvalho J. E.; Vendramini-Costa D.; de Castro I. B. D.; Ruiz A. L. T. G.; Marquissolo C. Effect of Goniothalamin on the Development of Ehrlich Solid Tumor in Mice. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 6742–6747. 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Baxendale I. R.; Deeley J.; Griffiths-Jones C. M.; Ley S. V.; Saaby S.; Tranmer G. K. A flow process for the multi-step synthesis of the alkaloid natural product oxomaritidine: a new paradigm for molecular assembly. Chem. Commun. 2006, 24, 2566–2568. 10.1039/b600382f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wiles C.; Watts P. Continuous flow reactors: a perspective. Green Chem. 2012, 14, 38–54. 10.1039/C1GC16022B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Baraldi P. T.; Hessel V. Micro reactor and flow chemistry for industrial applications in drug discovery and development. Green Process. Synth. 2012, 1, 149–167. 10.1515/gps-2012-0008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Wegner J.; Ceylan S.; Kirschning A. Flow chemistry – a Key Enabling Technology for (Multistep) Organic Synthesis. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012, 354, 17–57. 10.1002/adsc.201100584. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Chinnusamy T.; Yudha S.; Hager S. M.; Kreitmeier P.; Reiser O. Application of Metal-Based Reagents and Catalysts in Microstructured Flow Devices. ChemSusChem 2012, 5, 247–255. 10.1002/cssc.201100444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Elvira K. S.; i Solvas X. C.; Wootton R. C. R.; deMello A. J. The past, present and potential for microfluidic reactor technology in chemical synthesis. Nat Chem. 2013, 5, 905–915. 10.1038/nchem.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Hessel V.; Kralisch D.; Kockmann N.; Nöel T.; Wang Q. Novel Process Windows for Enabling, Accelerating, and Uplifting Flow Chemistry. ChemSusChem 2013, 6, 746–789. 10.1002/cssc.201200766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Baxendale I. R. The integration of flow reactors into synthetic organic chemistry. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2013, 88, 519–552. 10.1002/jctb.4012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; i Mándity I. M.; Ötvös S. B.; Fülöp F. Strategic Application of Residence-Time Control in Continuous-Flow Reactors. ChemistryOpen 2015, 4, 212–223. 10.1002/open.201500018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Reizman B. J.; Jensen K. F. Feedback in Flow for Accelerated Reaction Development. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 1786–1796. 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k Plutschack M. B.; Pieber B.; Gilmore K.; Seeberger P. H. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to Flow Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 11796–11893. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Souza J. M.; Galaverna R.; De Souza A. A. N.; Brocksom T. J.; Pastre J. C.; De Souza R. O. M. A.; De Oliveira K. T. Impact of continuous flow chemistry in the synthesis of natural products and active pharmaceutical ingredientes. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2018, 90, 1131–1174. 10.1590/0001-3765201820170778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Damião M. C. F. C. B.; Galaverna R.; Kozikowski A. P.; Eubanks J.; Pastre J. C. Telescoped continuous flow generation of a library of highly substituted 3-thio-1,2,4-triazoles. React. Chem. Eng. 2017, 2, 896–907. 10.1039/C7RE00125H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Damião M. C. F. C. B.; Marçon H. M.; Pastre J. C. Continuous flow synthesis of the URAT1 inhibitor lesinurad. React. Chem. Eng. 2020, 5, 865–872. 10.1039/C9RE00483A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pastre J. C.; Browne D. L.; Ley S. V. Flow chemistry syntheses of natural products. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 8849–8869. 10.1039/c3cs60246j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Murray P. R. D.; Browne D. L.; Pastre J. C.; Butters C.; Guthrie D.; Ley S. V. Continuous Flow-Processing of Organometallic Reagents Using an Advanced Peristaltic Pumping System and the Telescoped Flow Synthesis of (E/Z)-Tamoxifen. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2013, 17, 1192–1208. 10.1021/op4001548. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Noël T.; Su Y.; Hessel V.. Topics in Organometallic Chemistry, Organometallic Flow Chemistry. Beyond Organometallic Flow Chemistry: The Principles Behind the Use of Continuous-Flow Reactors for Synthesis; Noël T., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: 2015; Vol. 57, pp 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- a Yadav J. S.; Bhunia D. C.; Ganganna B.; Singh V. K. First stereoselective total synthesis of cryptomoscatone E1 and synthesis of (+)-goniothalamin via an asymmetric acetate aldol reaction. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 5254–5260. 10.1039/c3ra23167d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Ramachandran P. V.; Reddy M. V. R.; Brown H. C. Asymmetric synthesis of goniothalamin, hexadecanolide, massoia lactone, and parasorbic acid via sequential allylboration–esterification ring-closing metathesis reactions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 583–586. 10.1016/S0040-4039(99)02130-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Fátima A.; Pilli R. A. Enantioselective approach to the asymmetric synthesis of (6R)-hydroxymethyl-5,6-dihydro-2H-pyran-2-one. A formal synthesis of (R)-argentilactone and total synthesis of (R)-goniothalamin. ARKIVOC 2003, 10, 118–126. [Google Scholar]; d Nahra F.; Riant O. Recruiting the Students To Fight Cancer: Total Synthesis of Goniothalamin. J. Chem. Educ. 2015, 92, 179–182. 10.1021/ed500457d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Sundby E.; Perk L.; Anthonsen T.; Aasen A. J.; Hansen T. V. Synthesis of (+)-goniothalamin and its enantiomer by combination of lipase catalyzed resolution and alkene metathesis. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 521–524. 10.1016/j.tet.2003.10.102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Gruttadauria M.; Lo Meo P.; Noto R. Short and efficient chemoenzymatic synthesis of goniothalamin. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 83–85. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2003.10.115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Kobayashi S.; Endo T.; Schneider U.; Uenoa M. Aldehydeallylation with allylboronates providing α-addition products. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 1260–1262. 10.1039/b924527h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Chandra J. S.; Reddy M. V. R. Stereoselective allylboration using (B)-γ-alkoxyallyldiisopinocampheylboranes: highly selective reactions for organic synthesis. ARKIVOC 2007, 121–144. [Google Scholar]; c Brown H. C.; Jadhav P. K. Asymmetric carbon-carbon bond formation via beta.-allyldiisopinocampheylborane. Simple synthesis of secondary homoallylic alcohols with excellent enantiomeric purities. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105, 2092–2093. 10.1021/ja00345a085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Brown H. C.; Ramachandran P. V. Versatile α-pinene-based borane reagents for asymmetric syntheses. J. Organomet. Chem. 1995, 500, 1–19. 10.1016/0022-328X(95)00509-O. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Roush W. R.; Adam M. A.; Walts A. E.; Harris D. J. Stereochemistry of the reactions of substituted allylboronates with chiral aldehydes. Factors influencing aldehyde diastereofacial selectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 3422–3434. 10.1021/ja00272a043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Suriboot J.; Bazzi H. S.; Bergbreiter D. E. Supported Catalysts Useful in Ring-Closing Metathesis, Cross Metathesis, and Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization. Polymers 2016, 8, 140–163. 10.3390/polym8040140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Xia L.; Peng T.; Wang G.; Wen X.; Zhang S.; Wang L. Grubbs Catalysts Immobilized on Merrifield Resin for Metathesis of Leaf Alcohols by using a Convenient Recycling Approach. ChemistryOpen 2019, 8, 45–48. 10.1002/open.201800188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Werghi B.; Pump E.; Tretiakov M.; Abou-Hamad E.; Gurinov A.; Doggali P.; Anjum D. H.; Cavallo L.; Bendjeriou-Sedjerari A.; Basset J.-M. Exploiting the interactions between the ruthenium Hoveyda–Grubbs catalyst and Al-modified mesoporous silica: the case of SBA15 vs. KCC-1. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 3531–3537. 10.1039/C7SC05200F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Samantaray M. K.; Pump E.; Bendjeriou-Sedjerari A.; D’Elia V.; Pelletier J. D. A.; Guidotti M.; Psaro R.; Basset J.-M. Surface organometallic chemistry in heterogeneous catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 8403–8437. 10.1039/C8CS00356D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Balcar H.; Žilková N.; Kubů M.; Mazur M.; Bastl Z.; Čejka J. Ru complexes of Hoveyda–Grubbs type immobilized on lamellar zeolites: activity in olefin metathesis reactions. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2015, 11, 2087–2096. 10.3762/bjoc.11.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Al-Hashimi M.; Tuba R.; Bazzi H. S.; Grubbs R. H. Synthesis of Polypentenamer and Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) with a Phase-Separable Polyisobutylene-Supported Second-Generation Hoveyda–Grubbs Catalyst. ChemCatChem 2016, 8, 228–233. 10.1002/cctc.201500930. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Balcar H.; Žilková N.; Kubů M.; Polášek M.; Zedník J. Metathesis of cardanol over ammonium tagged Hoveyda-Grubbs type catalyst supported on SBA-15. Catal. Today. 2018, 304, 127–134. 10.1016/j.cattod.2017.09.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Chołuj A.; Zieliński A.; Grela K.; Chmielewski M. J. Metathesis@MOF: Simple and Robust Immobilization of Olefin Metathesis Catalysts inside (Al)MIL-101-NH2. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 6343–6349. 10.1021/acscatal.6b01048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Michrowska A.; Mennecke K.; Kunz U.; Kirschning A.; Grela K. A New Concept for the Noncovalent Binding of a Ruthenium-Based Olefin Metathesis Catalyst to Polymeric Phases: Preparation of a Catalyst on Raschig Rings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 13261–13267. 10.1021/ja063561k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Solodenko W.; Doppiu A.; Frankfurter R.; Vogt C.; Kirschning A. Silica Immobilized Hoveyda Type Pre-Catalysts: Convenient and Reusable Heterogeneous Catalysts for Batch and Flow Olefin Metathesis. Aust. J. Chem. 2013, 66, 183–191. 10.1071/CH12434. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Trapp O.; Weber S. K.; Bauch S.; Hofstadt W. High-Throughput Screening of Catalysts by Combining Reaction and Analysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 7307–7310. 10.1002/anie.200701326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Halbach T. S.; Mix S.; Fischer D.; Maechling S.; Krause J. O.; Sievers C.; Blechert S.; Nuyken O.; Buchmeiser M. R. Novel Ruthenium-Based Metathesis Catalysts Containing Electron-Withdrawing Ligands: Synthesis, Immobilization, and Reactivity. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 4687–4694. 10.1021/jo0477594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Fandrick K. R.; Savoie J.; Jinhua N. Y.; Song J. J.; Senanayake C. H.. Challenges and Opportunities for Scaling the Ring-Closing Metathesis Reaction in the Pharmaceutical Industry. In Olefin Metathesis – Theory and Practice; Grela K., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, 2014; pp 349. [Google Scholar]; b Higman C. S.; Lummiss J. A. M.; Fogg D. E. Olefin Metathesis at the Dawn of Implementation in Pharmaceutical and Specialty-Chemicals Manufacturing. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 3552–3565. 10.1002/anie.201506846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Farina V.; Horvath A.. Ring-Closing Metathesis in the Large-Scale Synthesis of Pharmaceuticals. In Handbook of Metathesis; Grubbs R. H.; Wenzel A. G., Eds.; Wiley VCH: Weinheim, 2015; Vol. 2, pp 633. [Google Scholar]

- Kong J.; Chen C.; Balsells-Padros J.; Cao Y.; Dunn R. F.; Dolman S. J.; Janey J.; Li H.; Zacuto M. J. Synthesis of the HCV Protease Inhibitor Vaniprevir (MK-7009) Using Ring-Closing Metathesis Strategy. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 3820–3828. 10.1021/jo3001595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das B.; Nagendra S.; Reddy C. R. Stereoselective total synthesis of (+)-cryptofolione and (+)-goniothalamin. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2011, 22, 1249–1254. 10.1016/j.tetasy.2011.06.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monfette S.; Fogg D. E. Equilibrium Ring-Closing Metathesis. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 3783–3816. 10.1021/cr800541y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Tanimu A.; Stephan J.; Khalid A. Heterogeneous catalysis in continuous flow microreactors: A review of methods and applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 327, 792–821. 10.1016/j.cej.2017.06.161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Galaverna R.; Fernandes L. P.; Browne D. L.; Pastre J. C. Continuous flow processing as a tool for the generation of terpene-derived monomer libraries. React. Chem. Eng. 2019, 4, 362–367. 10.1039/C8RE00237A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Brzozowski M.; O’Brien M.; Ley S. V.; Polyzos A. Flow Chemistry: Intelligent Processing of Gas–Liquid Transformations Using a Tube-in-Tube Reactor. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 349–362. 10.1021/ar500359m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Pastre J. C.; Browne D. L.; O’Brien M.; Ley S. V. Scaling Up of Continuous Flow Processes with Gases Using a Tube-in-Tube Reactor: Inline Titrations and Fanetizole Synthesis with Ammonia. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2013, 17, 1183–1191. 10.1021/op400152r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skowerski K.; Czarnocki S. J.; Knapkiewicz P. Tube-In-Tube Reactor as a Useful Tool for Homo- and Heterogeneous Olefin Metathesis under Continuous Flow Mode. ChemSusChem 2014, 7, 536–542. 10.1002/cssc.201300829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Although the conversion of 20 back to goniothalamin using an olefin cross-metathesis reaction with styrene was not evaluated, it is likely that this reaction would require a large excess of styrene and longer reaction time due to the methyl group at the exo-double bond of olefin 20.

- a Kirschning A.; Solodenko W.; Mennecke K. Combining Enabling Techniques in Organic Synthesis: Continuous Flow Processes with Heterogenized Catalysts. Chem. Eur. J. 2006, 12, 5972–5990. 10.1002/chem.200600236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Smith C. J.; Iglesias-Sigüenza F. J.; Baxendale I. R.; Ley S. V. Flow and batch mode focused microwave synthesis of 5-amino-4-cyanopyrazoles and their further conversion to 4-aminopyrazolopyrimidines. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007, 5, 2758–2761. 10.1039/b709043a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Brasholz M.; Macdonald J. M.; Saubern S.; Ryan J. H.; Holmes A. B. A Gram-Scale Batch and Flow Total Synthesis of Perhydrohistrionicotoxin. Chem. Eur. J. 2010, 16, 11471–11480. 10.1002/chem.201001435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Newton S.; Carter C. F.; Pearson C. M.; Alves L. C.; Lange H.; Thansandote P.; Ley S. V. Accelerating Spirocyclic Polyketide Synthesis using Flow Chemistry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 4915–4920. 10.1002/anie.201402056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Pellegatti L.; Sedelmeier J. Synthesis of Vildagliptin Utilizing Continuous Flow and Batch Technologies. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2015, 19, 551–554. 10.1021/acs.oprd.5b00058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Fitzpatrick D. E.; Ley S. V. Engineering chemistry: integrating batch and flow reactions on a single, automated reactor platform. React. Chem. Eng. 2016, 1, 629–635. 10.1039/C6RE00160B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Carmona-Vargas C. C.; Alves L. D. C.; Brocksom T. J.; de Oliveira K. T. Combining batch and continuous flow setups in the end-to-end synthesis of naturally occurring curcuminoids. React. Chem. Eng. 2017, 2, 366–374. 10.1039/C6RE00207B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; h Schotten C.; Howard J. L.; Jenkins R. L.; Codina A.; Browne D. L. A continuous flow-batch hybrid reactor for commodity chemical synthesis enabled by inline NMR and temperature monitoring. Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 5503–5509. 10.1016/j.tet.2018.05.070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.