Abstract

Background

Medical student education in the era of the COVID-19 outbreak is vastly different than the standard education we have become accustomed to. Medical student assessment is an important aspect of adjusting curriculums in the era of increased virtual learning.

Methods

Students took our previously validated free response clinical skills exam (CSE) at the end of the scheduled clerkship as an open-book exam to eliminate any concern for breaches in the honor code and then grades were adjusted based on historic norms. The National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) shelf exam was taken with a virtual proctor. Students whose clerkship was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic were compared to the students from a similarly timed surgery block the previous 3 years. Primary outcomes included CSE and NBME exam scores. Secondary outcomes included clinical evaluations and the percentage of students who received grades of Honors, High Pass, and Pass. After the surgery clerkship was completed, we surveyed all students who participated in the surgery clerkship during the COVID-19 crisis.

Results

There were 19 students during the COVID-interrupted clerkship and 61 students in similarly timed clerkships between 2017 and 2019. Prior to adjustment and compared to historic scores, the COVID-interrupted clerkship group scored higher on the CSE, NBME exam, and performance evaluations (median, CSE:75.2 vs 68.7, shelf:68.0 vs 64.0, performance evaluation mean: 2.96 vs 2.78). The percentage of students with an honors was marginally higher in the group affected by COVID (42% vs 32%). Out of 19 students surveyed, 9 students responded. Seven students stated they would have preferred a closed-book CSE, citing a few drawbacks of the open-book format such as modifying their exam preparation, being discouraged from thinking prior to searching online during the test, and second guessing their answers.

Conclusions

During the initial outbreak of COVID-19, we found that an open book exam and a virtually proctored shelf exam was a reasonable option. However, to avoid adjustments and student dissatisfaction, we would recommend virtual proctoring if available.

Key Words: Medical student exams, Medical student grading, NBME shelf, Proctored exams, COVID-19 medical education

COMPETENCIES: Professionalism, Practice-Based Learning and Improvement, Systems-Based Practice

Background

Medical student education in the era of the COVID-19 outbreak is vastly different than the standard education we have become accustomed to.1 Some have addressed the concerns surrounding medical student education and how they relate to risk mitigation, workforce and resource utilization, and the transition from in-person clerkships to online curriculums.1 We would like to add to these concerns the issue of medical student grading.

On March 15, 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic spread rapidly throughout New York City, all clinical clerkships at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons were suspended.2 As part of their major clinical year, 19 students were actively on their surgical clerkship at this time. Twelve of them at New York Presbyterian-Columbia and 7 students at alternate clinical sites. All students were told not to report to their clinical sites and in the ensuing days were advised to leave campus and New York City if possible. These 19 students had completed 3 weeks out of their 5-week surgical clerkship and had 2 exams scheduled for the end of their clerkship. Over the course of the remaining 2 weeks, the students were quickly transitioned to an online curriculum consisting of video conference lectures and assigned prerecorded lectures and readings and our exam policy was forced to change as well. Here, we present our experience as a surgical clerkship in the epicenter of the COVID-19 outbreak within the United States with regard to exams and grading.

Methods

Exam Structure and Administration

One of our exams is a previously validated written examination developed at Columbia to assess the surgical knowledge, clinical decision making, communication skills, and professionalism of medical students on the surgery clerkship called the clinical skills exam (CSE).3 This exam, which consists entirely of free-response questions, has been found to predict clerkship ratings of clinical reasoning and fund of knowledge as well as USMLE Step 2 Clinical Knowledge scores. The other was the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) shelf exam. The CSE accounts for 30% of the student's overall grade and the NBME shelf exam accounts for 10%. Clinical evaluations comprise the remaining 60%. We needed to decide if, when, and how the students would take these exams and how their grades would be adjusted. The CSE is classically a closed book proctored exam, but concerns were raised regarding the honor code for an exam comprising 30% of their grade in a competitive clerkship if taken online at home. The decision was made to have students take the CSE at the end of the scheduled clerkship as an open book exam to eliminate any concern for breaches in the honor code.

The NBME offered options for virtual proctoring as an alternative to in-person proctored exams 2 weeks after our scheduled shelf exam.4 This method was used for our medical students for the NBME exam 2 weeks after the CSE. Students were not enrolled in a new clerkship during these 2 weeks though some decided to participate in pandemic-related volunteer activities. Honors, High Pass, and Pass grade cut-offs remained the same.

Grading Adjustments

Initially, we planned to adjust the CSE scores by percentile to historic norms to account for the expected higher scores with an open book exam and additional study time. To do this, we aggregated the previous three years scores for the CSE, matched them with the corresponding percentile from the affected block, and awarded that student the historic grade for their given percentile. However, when adjusted, this method disproportionately affected some students over others. With this system, students in the lowest percentiles would have been deducted more points than higher percentiles to match their historic counterparts. Instead, we deducted the difference in the median score between the current block of students and the historic norms. The mean was not used given the concern that outliers would bias the measure. Students were informed of the planned grading adjustments before taking the exam. They were also told this would be reevaluated after the exam to ensure fairness. After the exam, they were informed of the change to the adjustments.

Comparison and Feedback

Once grades were finalized, we approached the student data in a case-control methodology. We compared the students whose clerkship was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic to the students from a similarly timed surgery blocks from the previous 3 years. Each year, there are roughly 20 students who complete their surgery clerkship during the medical school's second clerkship block over March-April. Primary outcomes included CSE and NBME exam scores. Secondary outcomes included the percentage of students who received grades of Honors, High Pass, and Pass.

After the surgery clerkship was completed, we surveyed all students who participated in the surgery clerkship during the COVID-19 crisis.

This study was approved by the Columbia University Institutional Review Board.

Results

There were 19 students during the COVID-interrupted clerkship and 61 students in similarly timed clerkships between 2017 and 2019. The following results are summarized in Table 1 .

TABLE 1.

Differences Between COVID-Interrupted and Historic Clerkship Grades

| COVID-Interrupted clerkship (n = 19) | Historic Group (n = 61) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Columbia CSE score (Mean ± SD) |

75.6 ± 5.2 (unadjusted score) |

67.4 ± 8.1 | <0.001 |

| Columbia CSE score with adjustment (Mean ± SD) |

69.1 ± 5.2 | 67.4 ± 8.1 | 0.44 |

| NBME shelf exam score (Mean ± SD) |

64.7 ± 9.4 | 63.8 ± 11.1 | 0.52 |

| Percent with Honors as a final grade* | 42.1 | 32.0 | 0.356 |

| Performance evaluations† | |||

| Overall | 2.96 | 2.78 | 0.025 |

| Learning efforts | 3.11 | 2.85 | 0.099 |

| Teamwork and work ethic | 3.26 | 3.17 | 0.586 |

| Professionalism and communication | 3.26 | 3.10 | 0.250 |

| Exam, presentation, write up skills | 2.84 | 2.41 | 0.005 |

| Fund of knowledge, clinical | 2.32 | 2.34 | 0.889 |

| Reasoning and application |

SD = standard deviation; NBME = National Board of Medical Examiners

Final grades are reported as Honors, High Pass, Pass, and Fail.

This includes 2018-2020.

Scores and Grades

CSE Scores

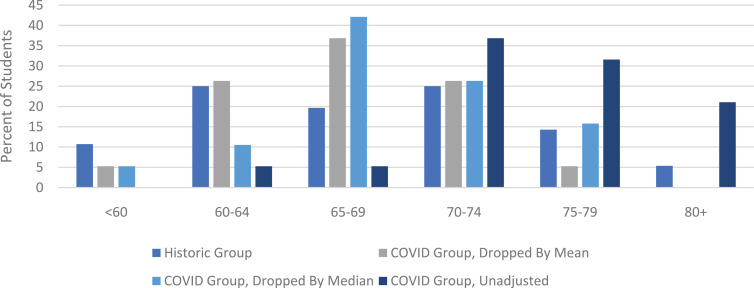

Prior to adjustment and compared to historic scores, the COVID-interrupted clerkship group had a higher mean (75.6 vs 67.4) and median (75.2 vs 68.7) CSE score. The COVID-interrupted group also had a smaller standard deviation (5.2 vs 8.1) and range (64.6-85.8 vs 46.6-82.2). In addition, the distribution of scores was markedly different between the COVID and historic groups (Fig. 1 ). Unadjusted scores from the interrupted clerkship had a left skew while the historic grades were more evenly spread. Adjustment by the historic mean or median diminished the leftward shift. In a sub analysis of students who completed their clerkships at sites other than the main campus, there was no significant difference between the COVID group and historic group (mean 71 vs 64, p = 0.165).

FIGURE 1.

Columbia clinical skills exam scores.

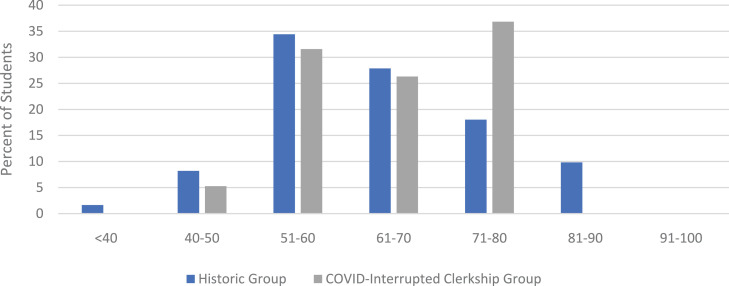

NBME Shelf Exam Scores

Compared to historic scores, shelf scores from the COVID-interrupted clerkship had a similar mean (64.7 vs 63.8), a higher median (68.0 vs 64.0), a smaller standard deviation (9.4 vs 11.1), and smaller range (40-75 vs 38-85). The distributions also differed between the 2 groups: historic scores had a right skew while scores of the COVID-interrupted clerkship were more evenly spread (Fig. 2 ). In a subanalysis of students who completed their clerkships at sites other than the main campus, there was no significant difference between the COVID group and historic group (mean 63 vs 61, p = 0.665).

FIGURE 2.

NBME shelf exam scores.

Student Performance Evaluations

Our students are evaluated by clinical educators in five categories on a scale of 1 to 5 within each category: Learning Efforts, Teamwork and Work Ethic, Professionalism and Communication, Exam, Presentation, and Write Up Skills, and Fund of Knowledge, Clinical Reasoning and Application. Overall, the COVID group scored higher in the performance evaluations particularly in the “Exam, Presentation, and Write Up Skills” section. The subjective comments from educators were equal in quality from previous blocks of students and years.

Grades

The percentage of students with an Honors was higher in the group affected by COVID when compared to historic norms throughout the year (42% vs 32%).

Student Survey

Out of 19 students surveyed, 9 students responded. Seven students stated they would have preferred a closed-book exam, citing a few drawbacks of the open-book format for the CSE such as modifying their exam preparation, being discouraged from thinking prior to searching online during the test, and second guessing their answers. However, despite these drawbacks, 5 students noted the exam was fair or well-designed. For example, one stated, “Thanks for working to make sure the exam accommodations were fair and reasonable for all – much appreciated.”

No students commented on the shelf exam.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has created many new challenges for educators. Exam policies and grading are one of these challenges. As we have navigated this new terrain, we were forced to change test-taking methods and adjust affected student scores.

The COVID pandemic affected student scores on the CSE and NBME shelf exams differently. Scores were significantly higher on the CSE exam compared to historic group, but similar between groups on the shelf exam. The COVID-interrupted clerkship CSE scores also had a skewed distribution with a preponderance of higher scores compared to historic scores. This is likely due to 2 factors. The first is the added time students had to study for these tests, as students did not have clinical responsibilities, which meant more time for exam studying. The second is the open book nature of the CSE.

There was a larger effect on the CSE than the shelf. The open book policy on the CSE is very likely to have caused this. However, there are other factors that likely contributed. The CSE accounts for 30% of the final grade and the shelf only 10%, students are likely to prioritize studying for the CSE over the shelf. In addition, students are more likely to prioritize competing interests such as pandemic-related volunteering or commitments external to medical school over the shelf. This difference in prioritization may have led some students to study less for the shelf, minimizing the effect of extra study time. This is further exacerbated by the 2-week delay in the shelf exam, while the CSE was taken at the scheduled time. In fact, inspection of the distribution of scores shows a large proportion of students did much better than historic groups, possibly representing students who prioritized the shelf. Another, smaller proportion of the COVID-interrupted clerkship had lower scores and may represent students who prioritized this test less.

With the difference in clerkship and exam conditions as well as the importance of the CSE to final grade, we had to adjust the CSE grading. Deduction of each student's grade by the difference in median was considered the best solution given the circumstances. Deduction by the difference in median equally affected each student within the clerkship and captured the overall discrepancy in study and exam experience between COVID-19 group and historic ones.

The student feedback regarding the CSE was encouraging, but overall suggests a dissatisfaction with an open-book exam adjustment.

Student exposure to their clinical evaluators was limited because of the truncated clerkship. However, we found that clinical evaluations were similar in quality to previous years. We suspect this is due to a decrease in case volume during the last week and faculty were able to devote more time to teaching and student feedback. It is also possible that clinical evaluations were affected by empathy bias.

This study has a few important limitations. First, the sample size of the COVID-interrupted group was small and the study examines a single clerkship at a single institution. Second, the interruption of the clerkship likely affected students differently. Though some students may have been able to use the bulk of their time to study, others may have been more affected by difficult study environments, poor internet connectivity, own or family illness. The effects of the students’ backgrounds and pressures external to medical school are important for those designing grading systems to keep in mind, but cannot be addressed with our current data. Notably, the only request received around exams was to extend the exam window to allow more reliable computer access for one student. Third, regarding the feedback on the CSE, it possible that students who commented that they would have preferred a closed book exam differed from the student who did not answer the survey. Since the survey was anonymous to encourage honesty, differences cannot be evaluated. Finally, it remains important to note that, though making the exam open-book circumvented the testing-security problems of remote testing and adjustment of scores mitigated the effect of the difference in examination format, the open book format likely decreased the CSE's ability to determine student clinical reasoning and fund of knowledge.

However, this study also has several strengths. This is the first study to investigate grading affected by the pandemic. In addition, we show results of the effects of the pandemic on different assessment tools: on free-response and multiple-choice exams as well as on open-book without proctoring and closed-book with virtual proctoring. In addition, we provide a sample of student feedback. Together, this study can help inform future decisions on grading in disrupted teaching.

Conclusions

During the initial outbreak of COVID-19, we were forced to adjust our normal exam and grading policies. Given the limited experience and knowledge about this situation, we opted for an open-book exam and a virtually proctored shelf exam. With grade adjustments, this is a reasonable option. However, to avoid adjustments and student dissatisfaction, we would recommend virtual proctoring through a video-conferencing application, if available.

References

- 1.Rose S. Medical Student Education in the Time of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amiel J., Kang Y., Forese L.COVID-19 updates: medical student teaching in healthcare settings suspended. Email sent to Columbia University College of Physicains and Surgeons staff and students. March 15, 2020.

- 3.Reinert A., Berlin A., Swan-Sein A., Nowygrod R., Fingeret A. Validity and reliability of a novel written examination to assess knowledge and clinical decision making skills of medical students on the surgery clerkship. Am J Surg. 2014;207:236–242. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butler A.Web-conferencing coming for test administrations. 2020.