Abstract

We conducted a molecular study of parasite sequences from a cohort of cutaneous leishmaniasis patients in Himachal Pradesh, India. Results revealed atypical cutaneous disease caused by Leishmania donovani parasites. L. donovani variants causing cutaneous manifestations in this region are different from those causing visceral leishmaniasis in northeastern India.

Keywords: atypical, cutaneous leishmaniasis, Leishmania donovani, parasites, Himachal Pradesh, India

Leishmaniasis is a complex disease with cutaneous, mucocutaneous, or visceral manifestations depending on the parasite species and host immunity. Despite continued elimination efforts, leishmaniasis continues to afflict known and newer endemic regions, where 0.5–0.9 million new cases of visceral leishmaniasis (VL) and 0.6–1.0 million new cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) occur every year (1). An increase in VL and CL cases from newer foci and atypical disease manifestation pose a challenge to leishmaniasis control programs (2–7). Unlike the known species-specific disease phenotype, parasite variants can cause atypical disease, so that Leishmania species generally associated with VL can cause CL and vice versa.

In India, VL caused by L. donovani parasites in the northeastern region and CL caused by L. tropica in the western Thar Desert represent the prevalent forms of the disease (2). Himachal Pradesh is a more recently leishmaniasis-endemic state in northwest where VL and CL coexist; CL incidence is higher than VL incidence and most cases are attributable to L. donovani instead of L. tropica infection (8,9). Sharma et al. conducted limited molecular analysis of a few CL cases and reported preliminary findings (8). For an in-depth study on the involvement of L. donovani parasites in CL cases, we conducted a comprehensive molecular analysis of CL cases in Himachal Pradesh.

The Study

During 2014–2018, an increase in CL cases occurred in Himachal Pradesh; case reports came from different tehsils (i.e., townships) in Kinnaur, Shimla, and Kullu and the previously nonendemic districts of Mandi and Solan (Appendix Table 1, Figure 1). We confirmed 60 CL cases indigenous to the state with detailed patient information, demonstration of the presence of Leishman-Donovan bodies and CL-specific histopathologic changes in skin lesional specimens, and PCR detection of parasitic infection (Appendix).

We conducted PCR and restriction fragment-length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of parasite species–specific internal transcribed spacer 1 (ITS1) sequences by using appropriate standard controls. We detected the expected ≈320-bp product with a HaeIII RFLP pattern specific to L. donovani complex in all patient biopsy specimens, indicating L. donovani, L. infantum, or both as the causative agent of infection (Appendix Figure 4) (10).

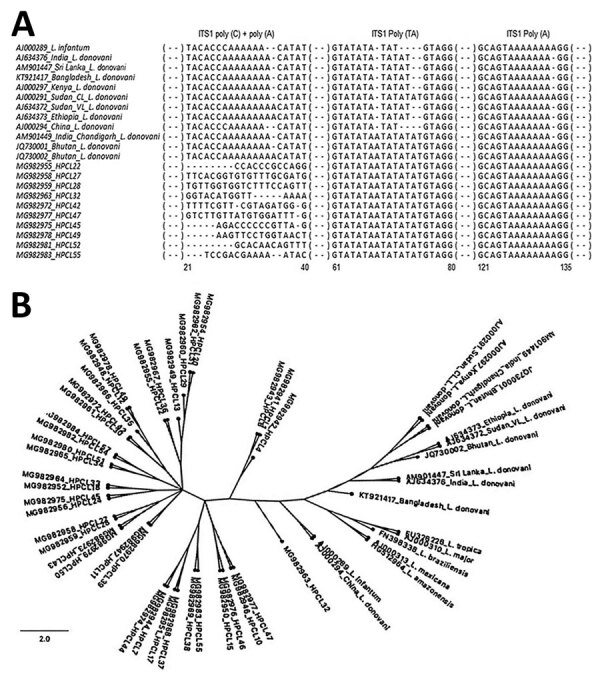

BLAST analysis (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) of 44 ITS1 test sequences showed all the samples to be closest to L. donovani, having maximum identity to L. donovani isolates from Bhutan (GenBank accession nos. JQ730001–2) and possibly L. infantum. None of the CL cases were consistent with L. tropica infection, unlike in a previous report (8). To distinguish whether HP isolates were L. donovani, L. infantum, or both and to infer genetic and geographic relatedness between these isolates and standard reference strains, we performed ITS1 microsatellite repeat analysis and phylogenetic classification (11–13). The 4 ITS1 polymorphic microsatellite repeat analysis indicate HP isolates different from L. infantum and closest to the L. donovani isolates from Bhutan (Table 1; Figure 1, panel A). We detected a polymorphism in the third poly (TA) microsatellite locus with 5 repeats and an atypical insert of TAA and the fourth poly (A) microsatellite tract with 8 repeats; these polymorphisms were identical to the VL-causing L. donovani isolates from Bhutan. An L. donovani Chandigarh isolate originally from HP is reported to be closest to the Bhutan isolates and matched with HP isolates at the third poly (TA) stretch (12). However, Himachal Pradesh isolates were distinct at the first poly C and the second poly A microsatellite tracts and had heterogeneous base sequences. Thus, these isolates represent L. donovani genetic variants; none showed the ITS1 sequence type previously assigned to the referred L. donovani isolates by Kuhls et al. (13). Our phylogenetic analysis of 44 ITS1 test sequences and ITS1 reference sequences placed all the CL-causing L. donovani isolates from Himachal Pradesh into a discrete cluster different from the VL-causing L. donovani from India and elsewhere and the CL-causing L. donovani isolates from Sri Lanka. The Himachal Pradesh CL isolates within the cluster exhibited considerable heterogeneity (Table 1; Figure 1, panel B; Appendix Table 4).

Table 1. Standard Leishmania strains used in ITS1-based microsatellite polymorphism and phylogenetic analysis of cutaneous leishmaniasis isolates, Himachal Pradesh, India, 2014–2018*.

| Standard Leishmania strains (place of origin) | WHO code | Genbank accession no. | Zymodeme | Disease form | Strain type† | ITS1 polymorphic microsatellite stretches (nucleotide position, bp) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poly C (24–39) | Poly A (24–39) | Poly TA (61–76) | Poly A (124–134) | ||||||

| VL- and CL-causing L. infantum and L. donovani parasite strains | |||||||||

| L. infantum (Tunisia) | MHOM/TN/80/IPT1 | AJ000289 | MON-1 | VL | A | 3 | 6 | 4 | 8 |

| L. donovani (India) | MHOM/IN/00/DEVI | AJ634376 | MON-2 | VL | H | 2 | 8 | 5 | 7 |

| L. donovani (Sri Lanka) | MHOM/LK/2002/ L60c | AM901447 | MON-37 | CL | ND | 2 | 8 | 5 | 7 |

| L. donovani (Bangladesh) | ND | KT921417 | ND | VL | ND | 2 | 8 | 5 | 7 |

| L. donovani (Kenya) | MHOM/KE/85/ NLB323 | AJ000297 | MON-37 | VL | G | 2 | 8 | 5 | 7 |

| L. donovani (Sudan) | MHOM/SD/75/ LV139 | AJ000291 | ND | CL | E | 2 | 8 | 6 | 8 |

| MHOM/SD/93/9S | AJ634372 | MON-18 | VL | F | 2 | 9 | 5 | 7 | |

| L. donovani (Ethiopia) | MHOM/ET/67/HU3 | AJ634373 | MON-18 | VL | F | 2 | 9 | 5 | 7 |

| L. donovani (China) | MHOM/CN/00/ Wangjie1 | AJ000294 | MON-35 | VL | C | 3 | 6 | 4 | 7 |

| L. donovani (HP, India) | MHOM/IN/83/ CHANDIGARH | AM901449 | MON-37 | VL | ND | 2 | 8 | 2, TAA, 3 | 7 |

|

L. donovani (Bhutan) |

Trashigang1 | JQ730001 | ND | VL | ND | 2 | 8 | 2, TAA, 3 | 8 |

| Samtse1 |

JQ730002 |

ND |

VL |

ND |

2 |

9 |

2, TAA, 3 |

8 |

|

| CL-causing L. donovani isolates from Himachal Pradesh‡ | |||||||||

| HPCL22 | – | MG982955 | ND | CL | ND | Heterogeneous | 2, TAA, 3 | 8 | |

| HPCL27 | – | MG982958 | ND | CL | ND | Heterogeneous | 2, TAA, 3 | 8 | |

| HPCL28 | – | MG982959 | ND | CL | ND | Heterogeneous | 2, TAA, 3 | 8 | |

| HPCL32 | – | MG982963 | ND | CL | ND | Heterogeneous | 2, TAA, 3 | 8 | |

| HPCL42 | – | MG982972 | ND | CL | ND | Heterogeneous | 2, TAA, 3 | 8 | |

| HPCL45 | – | MG982975 | ND | CL | ND | Heterogeneous | 2, TAA, 3 | 8 | |

| HPCL47 | – | MG982977 | ND | CL | ND | Heterogeneous | 2, TAA, 3 | 8 | |

| HPCL49 | – | MG982978 | ND | CL | ND | Heterogeneous | 2, TAA, 3 | 8 | |

| HPCL52 | – | MG982981 | ND | CL | ND | Heterogeneous | 2, TAA, 3 | 8 | |

| HPCL55 |

– |

MG982983 |

ND |

CL |

ND |

Heterogeneous |

2, TAA, 3 |

8 |

|

| CL-causing standard WHO Leishmania species | |||||||||

| L. major | MHOM/SU/73/ 5ASKH | AJ000310 | MON-4 | CL | ND | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| L. tropica | MHOM/SU/60/OD | EU326226 | LON-7 | CL | ND | 4 | 9 | 1, TTA, 2 | 3,C,4A |

| L. mexicana | MHOM/MX/85/ SOLIS | AJ000313 | MON-152 | CL | ND | 2 | 8 | 1, | 3,C,7A |

| L. braziliensis | MHOM/BR/00/ LTB300 | FN398338 | MON-166 | CL | ND | 2 | 6 | 1 | 5 |

| L. amazonensis | MHOM/BR/73/ M2269 | HG512964 | MON-132 | CL | ND | 2 | 7 | 1 | 3,C,6A |

*CL, cutaneous leishmaniasis; HP, Himachal Pradesh; ITS1, internal transcribed spacer 1; ND, not determined; VL, visceral leishmaniasis; WHO, World Health Organization. †ITS sequences strain type according to Kuhls et al. (13). ‡These species represent 10/44 samples used in polymorphic microsatellite analysis.

Figure 1.

ITS1-based molecular analysis of clinical isolates from cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) patients, Himachal Pradesh, India, 2014–2018. A) Multiple sequence alignment of ITS1 microsatellite repeat sequences of representative parasite isolates from CL patients with those of L. donovani complex reference strains from different geographic regions. Sequences were aligned by using BioEdit sequence alignment program (https://bioedit.software.informer.com/7.2). B) Phylogenetic tree of ITS1 sequences from CL test isolates (designated as HPCL, numbered in order of their collection) and standard Leishmania strains. Tree constructed by using maximum-likelihood method with 5,000 bootstraps in the dnaml program of PHYLIP package (http://evolution.genetics.washington.edu/phylip/doc/main.html). GenBank accession numbers are indicated. Scale bar indicates the nucleotide substitution per site. ITS1, internal transcribed spacer 1; RFLP, restriction fragment length polymorphism.

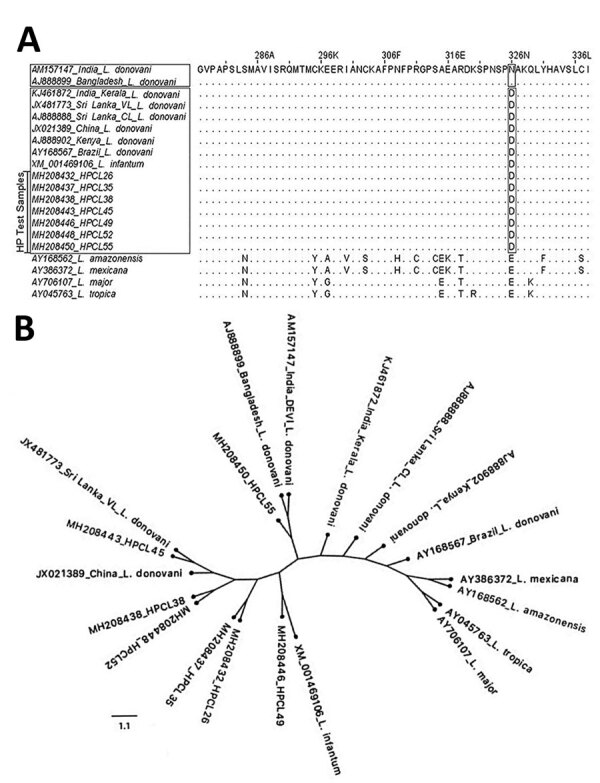

Sequences of the 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase gene (6PGDH) exhibit a high degree of polymorphism and have been used to identify Leishmania species and differentiate region-specific zymodemes (14). We performed multiple sequence alignment of the representative partial 6PGDH amino acid sequences from Himachal Pradesh isolates by using the homologous 6PGDH protein sequences of the reference Leishmania isolates to determine their genetic and geographic relatedness (Table 2; Figure 2, panel A; Appendix Table 4, Figure 5). Himachal Pradesh isolates exhibited a 6PGDH sequence specific to Mon-37 and different from Mon-2 (having aspartic acid in place of asparagine) at position 326 (Figure 2, panel A). Thus, CL-causing L. donovani from Himachal Pradesh were distinct from the most common VL-causing India Mon-2 L. donovani and the Bangladesh L. donovani isolate, whereas they were similar to the CL-causing L. donovani isolate from Kerala and CL- and VL-causing Mon-37 isolates from Sri Lanka and the isolates from Kenya, Brazil, and China.

Table 2. Standard Leishmania strains used in partial 6PGDH amino acid–based phylogenetic analysis of cutaneous leishmaniasis isolates, Himachal Pradesh, India, 2014–2018*.

| Species (place of origin) | WHO code | Zymodeme | GenBank accession no. | Pathology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHO standards | ||||

| L. donovani (India) | MHOM/IN/0000/DEVI | MON-2 | AM157147 | VL |

| L. major (Turkmenistan) | MHOM/TM/1973/5ASKH | ND | AY706107 | CL |

| L. infantum | ND | ND | XM_001469106 | ND |

| L. mexicana | MHOM/BZ/82/BEL21 | ND | AY386372 | CL |

| L. tropica | ND | ND | AY045763 | CL |

|

L. amazonensis

|

ND |

ND |

AY168562 |

CL |

| Regional standards | ||||

| L. donovani (China) | MHOM/CN/90/9044 | ND | JX021389 | VL |

| L. donovani (Kenya) | IMAR/KE/1962/LRC–L57 | MON-37 | AJ888902 | ND |

| L. donovani (Sri Lanka) | MHOM/LK/2010/OVN3 | MON-37 | JX481773 | VL |

| L. donovani (Sri Lanka) | MHOM/LK/2002/L59 | MON-37 | AJ888888 | CL |

| L. donovani (Bangladesh) | MHOM/BD/1997/BG1 | ND | AJ888899 | VL |

| L. donovani (Brazil) | ND | ND | AY168567 | ND |

| L. donovani (Kerala, India) | ND | ND | KJ461872 | CL |

*6PGDH, 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase gene; CL, cutaneous leishmaniasis; ND, not determined; VL, visceral leishmaniasis; WHO, World Health Organization.

Figure 2.

6PGDH-based molecular analysis of clinical isolates from cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) patients, Himachal Pradesh, India, 2014–2018. A) Sequence alignment of partial 6PGDH amino acid of CL isolates exhibit replacement of asparagine (N) with aspartic acid (D) at position 326 analogous to visceral leishmaniasis–causing and CL-causing isolates from Sri Lanka. B) Phylogenetic tree for 6PGDH sequences from CL test isolates (designated as HPCL, numbered in order of their collection) and standard Leishmania strains. Tree constructed by using maximum-likelihood method with 5,000 bootstraps in the dnaml program of PHYLIP package (http://evolution.genetics.washington.edu/phylip/doc/main.html). GenBank accession numbers are indicated. Scale bar indicates the amino acid substitution per site. 6PGDH, 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase gene; HP, Himachal Pradesh.

Phylogenetic analysis of 6PGDH amino acid sequences of CL isolates grouped them into a heterogeneous cluster; variants were closer to a viserotropic L. donovani isolate from Sri Lanka and distinct from the VL-causing L. donovani isolates from India and Bangladesh and CL-causing isolates from Kerala and Sri Lanka (Figure 2, panel B). However, the HPCL55 isolate (GenBank accession no. MH208450) grouped differently. The HPCL49 isolate (GenBank accession no. MH208446) showed relatedness to the standard L. infantum strain, although ITS1 analysis using BLAST and microsatellite repeat sequences showed regions of similarity with L. donovani. ITS1 and 6PGDH sequence analysis suggest that Himachal Pradesh isolates from CL patients consist of heterogenous L. donovani variants and possibly represent hybrid genotypes.

None of the CL patients had VL-specific symptoms or VL history. Ten of 43 patient blood samples tested positive for rK39 antibody, and 37 of 51 samples were positive for the circulating parasite DNA with L. donovani–specific ITS1 (Appendix Figure 6, panel A, B). The result suggests asymptomatic systemic L. donovani infection in a fraction of CL patients.

Conclusions

The presence of leishmaniasis in Himachal Pradesh is not yet well known in India and globally (15). Our epidemiologic study shows newer CL pockets during 2014–2018; thus, the state needs to be recognized as leishmaniasis-endemic by public health authorities (Appendix Figure 1). We conclude that CL cases in Himachal Pradesh are caused by L. donovani variants distinct from the viscerotropic L. donovani strain from northeast India. The CL isolates in Himachal Pradesh exhibit considerable heterogeneity and indicate the possible existence of genetic hybrids. The scenario appears somewhat similar to Sri Lanka and Kerala, where L. donovani parasites cause cutaneous disease, albeit with differences in the region-specific L. donovani variants. In lieu of the coexistence of VL and CL in Himachal Pradesh, parasite isolates from VL patients also need to be characterized. To understand the biology of atypical L. donovani variants with cutaneous manifestations and to genetically differentiate the dermotropic versus viscerotropic potential of L. donovani variants, comparison of CL- and VL-causing isolates in Himachal Pradesh using whole-genome sequence analysis is required.

L. donovani parasites in the blood of some CL patients represent human reservoirs similar to asymptomatic VL carriers, and the parasite variants have the potential to cause full-blown VL manifestations. An elaborate surveillance program dedicated to the Himachal Pradesh region is urgently required for better diagnosis, treatment, prediction of parasite variants in different afflicted pockets, and prevention of transmission of the disease to other regions.

Additional information about Leishmania donovani infection with atypical cutaneous manifestations, Himachal Pradesh, India, 2014–2018.

Acknowledgments

We thank Greg Matlashewski for his helpful suggestions and comments to improve the manuscript, Wen Wei Zhang for technical suggestions, and Rentala Madhubala for generously gifting Leishmania donovani and L. major standard cultures.

Biography

Ms. Thakur is a PhD student in the Department of Zoology at the Central University of Punjab, Bathinda, Punjab, India. Her primary research interests include the epidemiology and pathogenesis of infectious and parasitic diseases.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Thakur L, Singh KK, Kushwaha HR, Sharma SK, Shankar V, Negi A, et al. Leishmania donovani infection with atypical cutaneous manifestations, Himachal Pradesh, India, 2014–2018. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020 Aug [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2608.191761

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Leishmaniasis. 2019. [cited 2019 Sep 1]. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis

- 2.Thakur L, Singh KK, Shanker V, Negi A, Jain A, Matlashewski G, et al. Atypical leishmaniasis: A global perspective with emphasis on the Indian subcontinent. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e0006659. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandhya R, Rakesh P, Dev S. Emergence of visceral leishmaniasis in Kollam District, Kerala, southern India. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2019;6:1350–2. 10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20190639 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar NP, Srinivasan R, Anish TS, Nandakumar G, Jambulingam P. Cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania donovani in the tribal population of the Agasthyamala Biosphere Reserve forest, Western Ghats, Kerala, India. J Med Microbiol. 2015;64:157–63. 10.1099/jmm.0.076695-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siriwardana Y, Zhou G, Deepachandi B, Akarawita J, Wickremarathne C, Warnasuriya W, et al. Trends in recently emerged Leishmania donovani induced cutaneous leishmaniasis, Sri Lanka, for the first 13 Years. BioMed Res Int. 2019;2019:4093603. 10.1155/2019/4093603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma NL, Mahajan VK, Negi AK. Epidemiology of a new focus of localized cutaneous leishmaniasis in Himachal Pradesh. J Commun Dis. 2005;37:275–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumari S, Garg A. Lip leishmaniasis: a new emerging clinical form of cutaneous leishmaniasis from sub-Himalayan Region. Journal of Medical Science and Clinical Research. 2018;06:62–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma NL, Mahajan VK, Kanga A, Sood A, Katoch VM, Mauricio I, et al. Localized cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania donovani and Leishmania tropica: preliminary findings of the study of 161 new cases from a new endemic focus in himachal pradesh, India. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:819–24. 10.4269/ajtmh.2005.72.819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma NL, Sood A, Arora S, Kanga A, Mahajan V, Negi A, et al. Characteristics of Leishmania spp. isolated from a mixed focus of cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis in Himachal Pradesh (India). Internet J Third World Med. 2009;7(8).

- 10.el Tai NO, Osman OF, el Fari M, Presber W, Schönian G. Genetic heterogeneity of ribosomal internal transcribed spacer in clinical samples of Leishmania donovani spotted on filter paper as revealed by single-strand conformation polymorphisms and sequencing. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94:575–9. 10.1016/S0035-9203(00)90093-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dávila AM, Momen H. Internal-transcribed-spacer (ITS) sequences used to explore phylogenetic relationships within Leishmania. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2000;94:651–4. 10.1080/00034983.2000.11813588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yangzom T, Cruz I, Bern C, Argaw D, den Boer M, Vélez ID, et al. Endemic transmission of visceral leishmaniasis in Bhutan. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87:1028–37. 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuhls K, Mauricio IL, Pratlong F, Presber W, Schönian G. Analysis of ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer sequences of the Leishmania donovani complex. Microbes Infect. 2005;7:1224–34. 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ranasinghe S, Zhang W-W, Wickremasinghe R, Abeygunasekera P, Chandrasekharan V, Athauda S, et al. Leishmania donovani zymodeme MON-37 isolated from an autochthonous visceral leishmaniasis patient in Sri Lanka. Pathog Glob Health. 2012;106:421–4. 10.1179/2047773212Y.0000000054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Leishmaniasis country profile–2015, India. 2017. [cited 2019 Sep 1]. https://www.who.int/leishmaniasis/burden/India_2015-hl.pdf?ua=1

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional information about Leishmania donovani infection with atypical cutaneous manifestations, Himachal Pradesh, India, 2014–2018.