Abstract

We ran a simulation comparing 3 methods to calculate case-fatality risk for coronavirus disease using parameters described in previous studies. Case-fatality risk calculated from these methods all are biased at the early stage of the epidemic. When comparing real-time case-fatality risk, the current trajectory of the epidemic should be considered.

Keywords: respiratory infections, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, SARS-CoV-2, SARS, COVID-19, 2019 novel coronavirus disease, coronavirus disease, zoonoses, viruses, coronavirus

We read with interest the research letter on estimating case-fatality risk for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) by Wilson, et al. (1). In their analyses, the authors estimated the case-fatality risk adjusted to a fixed lag time to death. They acknowledged that the calculated adjusted case-fatality risk (aCFR) might be influenced by residual uncertainties from undiagnosed mild COVID-19 cases and a shortage of medical resources. However, we believe the time-varying number of cumulative cases and deaths also should be considered in the epidemic profile.

Because of the exponential growth curve of the COVID-19 outbreak, the numbers of cumulative cases and cumulative deaths have been relatively close to each other in the early stages of the outbreak, leading to a much higher aCFR. As the outbreak progresses, the ratio of the cumulative cases and deaths declines, which reduces the aCFR. Thus, a higher aCFR does not necessarily indicate increased disease severity.

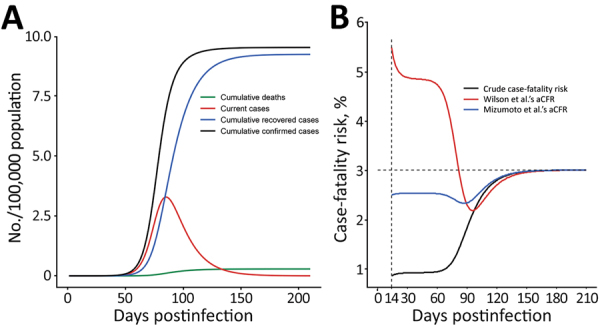

To test our hypothesis, we performed a simulation study by using a susceptible-infectious-recovered–death model and parameters set according to prior studies. We set the infectious period as 10 days (2); case-fatality risk as 3% (3); basic reproductive ratio (R0) as 2.5 (4); recovery rate as 1/13 day (5), that is, 13 days from illness onset to recovery; and the population size as 1 million. We compared crude case-fatality risk, aCFR per Wilson et al.’s method, and aCFR per Mizumoto et al.’s method (6). Although the case-fatality risk calculated from these methods all are biased at the early stage of the epidemic, case-fatality risk calculated from Mizumoto et al.’s method was closer to the true case-fatality risk of 3% (Figure).

Figure.

Progression of coronavirus disease outbreak and changes in the case-fatality risk by crude and adjusted rates. Crude case-fatality risk is the cumulative number of deaths on a given day divided by the cumulative number of cases on the same day. We set the infectious period as 10 days (2); case-fatality risk as 3% (3); basic reproductive ratio (R0) as 2.5 (4); recovery rate as 1/13 day (5), that is, 13 days from illness onset to recovery; and the population size as 1 million. A) Changes in the number of subpopulations over time after the first infection. B) Changes in crude case-fatality risk after 13th day of exposure and aCFR calculated by using Wilson et al.’s method (1) and by using Mizumoto et al.’s method (6). aCFR, adjusted case-fatality risk.

In conclusion, we recommend the Mizumoto et al. method (6) to calculate aCFR in real time. When comparing real-time estimation of the case-fatality risk across countries and regions, our results indicate that the current trajectory of the epidemic should be considered, particularly if the epidemic is still in its early growth phase.

Biography

Mr. Ge is a PhD candidate in the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, USA. His research interests include infectious disease modeling and vaccine design.

Dr. Sun is a research scientist at the Boston University School of Public Health. His research focuses on estimating the impact of air pollution and climate change on human health.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Ge Y, Sun S. Estimation of coronavirus disease case-fatality risk in real time. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020 Aug [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2608.201096

References

- 1.Wilson N, Kvalsvig A, Barnard LT, Baker MG. Case-fatality risk estimates for COVID-19 calculated by using a lag time for fatality. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26: Epub ahead of print. 10.3201/eid2606.200320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guan W-J, Ni Z-Y, Hu Y, Liang W-H, Ou C-Q, He J-X, et al. ; China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid-19. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;NEJMoa2002032; Epub ahead of print. 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team. [The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China] [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:145–51.32064853 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1199–207; Epub ahead of print. 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). 2020. Feb 24 [cited 2020 Mar 27]. https://www.who.int/docs/default- source/coronaviruse/who-china-joint- mission-on-covid-19-final-report.pdf

- 6.Mizumoto K, Chowell G. Estimating risk for death from 2019 novel coronavirus disease, China, January–February 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26: Epub ahead of print. 10.3201/eid2606.200233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]