Abstract

Background

Use of family planning (FP) saves the lives of mothers and children, and contributes to better economic outcomes for households and empowerment for women. In Tanzania, the overall unmet need for FP is high. This study aimed: (1) to use focus group data to construct a theoretical framework to understand the multidimensional factors impacting the decision to use FP in rural Tanzania; (2) to design and pilot-test an educational seminar, informed by this framework, to promote uptake of FP; and (3) to assess acceptability and further refine the educational seminar based on focus group data collected 3 months after the education was provided.

Methods

We performed a thematic analysis of 10 focus group discussions about social and religious aspects of FP from predominantly Protestant church attenders prior to any intervention, and afterwards from six groups of church leaders who had attended the educational seminar.

Results

Key interpersonal influences included lack of support from husband/partner, family members, neighbours and church communities. Major intrapersonal factors impeding FP use were lack of medical knowledge and information, misconceptions, and perceived incompatibility of FP and Christian faith. Post-seminar, leaders reported renewed intrapersonal perspectives on FP and reported teaching these perspectives to community members.

Conclusions

Addressing intrapersonal barriers to FP use for leaders led them to subsequently address both intrapersonal and interpersonal barriers in their church communities. This occurred primarily by increasing knowledge and support for FP in men, family members, neighbours and church communities.

Keywords: education and training, family planning service provision, ethnic minority and cultural issues, qualitative research

Key messages.

In Tanzania, the overall unmet need for family planning (FP) is high, with greater unmet need in poorer, more rural and less educated women.

Factors influencing FP use include perceived incompatibility of FP and Christian faith, and lack of support from husbands, family and church communities.

Educating religious leaders about FP affected multiple factors that influence its uptake in Tanzania.

Introduction

Use of family planning (FP) saves lives of mothers and children by preventing high-risk pregnancies and spacing births. Interpregnancy intervals shorter than 18 months are associated with increased maternal morbidity and mortality, adverse fetal and infant outcomes, and preterm births.1 Use of FP also contributes to better economic outcomes for households and women’s empowerment.2 Unmet need for FP, defined as not using modern contraception despite wanting to delay or prevent pregnancy, was 12% worldwide and 22% in sub-Saharan Africa in 2017.2 In Tanzania, the overall unmet need for FP is 21.7%,2 with greater unmet need among poorer, more rural and less educated women.3 In the Mwanza region where we work, women’s unmet need for FP is 34%.4

Previously, we demonstrated that educating religious leaders in Mwanza on religious and medical aspects of male circumcision significantly increased uptake of male circumcision.5 We sought to use this established methodology to increase uptake of FP. In focus group discussions with Protestant church attenders, many men and women were unsure whether planning their families was compatible with their faith.6 Further, we reported that gender dynamics strongly impact a person’s uptake of FP and that despite misgivings about FP, focus group participants often noted its economic and maternal/child health benefits.6

Our study had three key goals. First, we further analysed prior data from focus group discussions6 with predominantly Protestant church attenders to construct a theoretical framework for understanding the multidimensional factors impacting the decision to use FP. Second, based on identified interpersonal and intrapersonal barriers to FP, we designed an educational seminar for church leaders. Given the distinct position of the Roman Catholic church on FP, we targeted the seminar towards Protestant church leaders. Finally, we collected follow-up focus group data 3 months post-seminar to assess its acceptability and make further refinements.

Methods

Theoretical framework

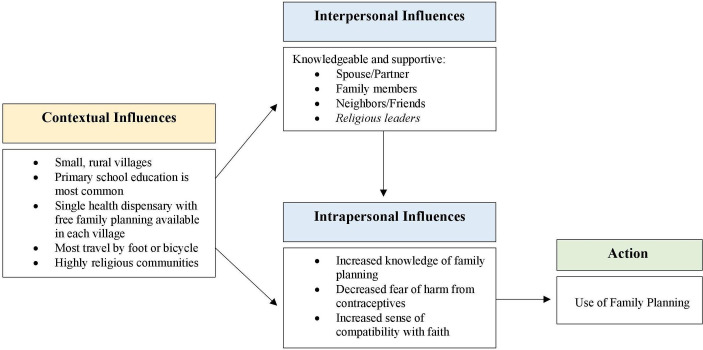

We used social action theory to understand and analyse influences that may contribute to poor uptake of FP by rural women (figure 1). This framework is most applicable because it considers multiple influences on the decision-making process, with the ultimate goal of strategising to promote action.7 Utilisation of this multidimensional approach to promote healthy behaviour has been effective for a variety of behavioural health outcomes.8–11

Figure 1.

Social action theory identifying influences that affect uptake of family planning in rural Tanzania.

Focus group data

To construct the framework, we analysed data from 10 focus group discussions among Christian church attenders collected in 2016.6 Participants, from rural villages in northwest Tanzania, included 52 women and 48 men with a median age of 35 (IQR 26–46) years. Our team invited Protestant participants of all denominations, and two Roman Catholic parishioners participated. Discussions in Kiswahili were led by two trained facilitators of the same gender as the participants and explored participants’ knowledge and attitudes towards FP, including its relation to their faith. Audio recordings were transcribed and translated to English by a professional translation service. All participants provided written informed consent. Ethical approval was obtained from the Tanzanian National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR/HQ/R.8a/Vol.IX/2284) and Weill Cornell Medicine (IRB#1603017171).

The 1-day educational seminar for church leaders was offered in three villages between September 2018 and February 2019. Post-intervention focus group discussions with leaders who had attended the seminar occurred 3 months later. In each village, we arranged one focus group for men and one for women, yielding six post-intervention discussions with 23 men and 23 women. Six Catholic leaders who had attended seminars also participated in post-intervention discussions.

We performed a thematic analysis in which two study team members (CA, JD) independently read and coded transcripts using NVivo Version 12 (Doncaster, Australia) to identify and agree on key factors associated with poor uptake of FP. Some factors were prespecified and additional factors were identified during coding. Factors were organised into components of the framework, and illustrative quotations selected. Study team members reviewed the final text for accuracy and clarity.

Public involvement

The development of the research question, theoretical framework, and educational seminar were informed by focus group data on the experiences and preferences of community members. The resulting seminar was provided to church leaders during this study and continues more widely in an ongoing project. Knowledge imparted to church leaders is further disseminated as they share it with their communities.

Results

Contextual influences

Social action theory begins by considering contextual influences (figure 1). In the rural villages in which this study was conducted – which characterise much of life in Tanzania – most people have completed seven or less years of education.12 13 Villages typically have a single health dispensary where contraceptives are provided free of charge by the Ministry of Health. Although nurses offer education about FP, approximately one-quarter of adults report not having been exposed to information about FP in the previous 6 months.14 Most adults are married,12 with an average of 6.314 children. Religious institutions are pervasive and influential throughout Tanzania; Christianity and Islam are the dominant faiths.15

The second section of the framework considers external interpersonal and internal intrapersonal influences that contribute to health behaviour.

Interpersonal influences

Partner/spouse

For a variety of reasons, men did not support their wives’ use of FP. Many stated that a wife’s duty was bearing many children, summarised in one woman’s affirmation that “if you stop giving birth, your [marriage] is over”.

Others perceived use of FP as causing sexual dissatisfaction for husbands. Men were concerned that their wives’ libidos would decrease, while women feared that their husbands would seek other sexual partners if they used the calendar method:

"Maybe some women fail to use FP due to the fact that when she uses the calendar the man gets another woman, he marries, she has a child, now the woman can’t do anything, she decides to continue giving birth." [Female church attender]

Male disapproval of FP strongly impeded its uptake. Both genders reported that men are considered heads of households and hold decision-making authority:

"Their husbands are usually very harsh. They don’t want them to use FP, they just want … well, a child. Now if the woman goes for FP, it brings isolation in the marriage."[Female church attender]

Family

Women are often pressured to bear children by both their own and their husband’s families:

"She cannot use FP, she says, ‘My mother did not use FP so how can I?’" [Female church attender]

"Maybe she was forbidden by her husband or his relatives. She should not use FP." [Female church attender]

Neighbours/friends

Neighbours and friends were a major source of information and misinformation about FP, generating fear among women and men:

"In my community, some say that FP has side effects … you find the child, you can give birth to it with an implant in the eye … others are saying that when they use FP, they get cancer of the uterus, you bleed for even a whole month! That is why they are scared of FP." [Female church attender]

Religious community

Participants consistently affirmed the strong influence of religious leaders, explaining that “many communities believe the pastor a lot and the pastor has a great influence in the community-- therefore when they… explain a matter like [FP] it is easy to be understood” [Male church attender]. Yet most had never heard their church leaders discuss FP, and reported struggling to discern whether FP accords with their faith:

"I don’t know if the Bible says it but as I recognise even God said he allows us to go and multiply. I don’t know if there is another passage which says you should give birth according to [FP]." [Female church attender]

In addition, many participants’ statements mingled traditional cultural teachings with beliefs about God’s plans. This led men and women to refer to woman’s eggs as “unborn children” given by God, implicitly requiring her to procreate:

"There is no using FP because I want [to give birth] until the eggs that God planned [have been used up]." [Female church attender]

Intrapersonal influences

Lack of knowledge

Participants reiterated knowledge gaps as barriers to FP use:

"The reasons that cause some not to use FP is lack of education. If you were given education as to what FP means, some would know that it cannot harm you if you use it the healthy way." [Female church attender]

Participants agreed that education for men was key:

"[The man] has no such education [about FP] … the main decision maker is the man, he should have education of knowing FP." [Male church attender]

Fear of harm from contraceptives

Perceived health concerns deterred contraceptive use. Some feared side effects like excess bleeding:

"The reason which causes a woman not to use FP is because she is afraid [it] is dangerous, and at times there is excessive bleeding during her days." [Male church attender]

Others believed that contraceptives caused cancer and birth defects:

"If you use these [contraceptive] pills, [babies] can be born without intelligence." [Male church attender]

Uncertainty about compatibility with faith

Uncertainty about whether FP is compatible with religious beliefs has been described in detail.6 In the absence of clear teaching, a range of conclusions emerged during focus group discussions, from a belief that FP is “murder”, to seeing FP as a moral responsibility to enable parents to provide for their children. This spectrum of views highlights the potential – and urgent need – for guidance and clarification by religious leaders as people gain knowledge and make decisions about FP use.

Design of educational intervention

Based on these two potentially modifiable aspects of the framework (interpersonal and intrapersonal influences), we designed an educational intervention that targeted these influences at multiple levels (figure 1).

During this 1-day seminar, we aimed to increase knowledge about FP, address misconceptions and fears, and provide a forum for discussion in the context of religious beliefs (box 1).

Box 1. Sessions included in educational intervention.

I. Presentation of major themes from focus group discussions

Perceived benefits of family planning (FP)

Perceived harms/fears about FP

Roles of men and women in decision about FP use

Perceptions about religion and FP (including desire for information by many)

II. Discussion of historical and biblical traditions about FP

Historical positions of various denominations on FP

Biblical teaching/lack of teaching specifically on FP

-

Biblical principles guiding use of FP:

Decision-making about topics on which scripture is silent

God’s care for the poor

Mutuality in marital decisions about sex (1 Corinthians 7:1–6)

III. Medical teaching about menstrual cycle and various FP techniques (mechanism, efficacy, side effects)

Health benefits of spacing pregnancies

Review of female reproductive system and menstrual cycle (including discussion of lifetime number of eggs a woman has)

FP options: calendar method, lactational amenorrhea, withdrawal, condoms, oral contraceptive pills, injectables, implants, intrauterine devices, permanent sterilisation

Our hypothesis was that improving church leaders’ knowledge would equip them to teach their congregations. This in turn would address intrapersonal influences for church attendees, and would also affect interpersonal influences including intra-marriage, intra-family and intra-community discussion and support of FP.

We invited each Protestant church in the village to send one male and one female church leader to attend the seminar. Protestant denominations represented included the Africa Inland Church, Pentecostal Assemblies of God, Tanzania Assemblies of God, Baptist and Lutheran congregations, and Seventh Day Adventists; moreover, several interested Roman Catholics also attended.

Post-intervention focus group discussions

The seminar addressed multiple spheres of both intrapersonal and interpersonal interactions for church leaders (table 1), reaching a wide range of churches and communities. Most attendees were grateful for the opportunity to discuss this topic in the context of their churches:

Table 1.

Barriers to uptake of family planning that may be addressed by educational seminar

| Barrier identified in focus group data | Relevant studies from other regions in Africa | Goals for educational seminar | Post-seminar results |

| Intrapersonal influences | |||

| Poor medical understanding about FP limits its uptake, particularly for men | In Uganda, limited knowledge about FP is a key determinant of men’s negative perception of and lack of engagement in FP21 |

|

“We were just giving birth to children using local FP methods. Some were inserted with some sticks and some drunk mixed ashes after having sex, we thought can prevent pregnancy, some continued to get pregnant even after using those local methods … However, after that seminar I realised that the best method is to use modern contraceptives … such as pills, loop and so on … I realised that it is better to plan the family using modern methods.” [Female church leader] |

| Myths and fears about side effects and harms are prevalent | In Uganda and Tanzania, misconceptions and fears about FP are major obstacles to its use for both women and men22–24 |

|

|

| Many people perceive that FP is incompatible with religious beliefs |

|

“The Bible hasn’t kept quiet: it says that a person who doesn’t take care of his family is doing something bad, so you are supposed to have the power of taking care of those children you have so that they can have their basic needs.” [Male church leader] |

|

| Interpersonal influences | |||

| Men are major decision-makers but lack knowledge about FP | Several studies suggest that increasing male knowledge of FP could increase spousal communication on FP, elevating odds of a couple using FP22 25 26 |

|

“When we heard about FP taught in church, me and my husband went back home and we shared it very well… [using FP] is going well in the family.” [Female church leader] |

| Family members prioritise having many children and may perceive FP as taboo |

|

|

|

| Friends and neighbours spread false information about FP |

|

|

|

| Religious leaders are highly influential and many are not equipped to discuss FP | In a survey in Malawi, use of modern contraception was significantly lower in congregations whose religious leader did not approve its use27 |

|

|

FP, family planning.

"We appreciate this seminar because it is going even in churches. That means it isn’t bad, even in churches they talk about [having children] according to the [economic] situation and we would suggest that this education continue to be provided." [Female church leader]

Seminar attendees reported feeling empowered about using FP and sharing their new knowledge and perspective:

"I feel encouraged because after the training, we feel strong and we continue to encourage some other people and tell them, even our neighbours: join family planning." [Female church leader]

However not everyone was receptive. Seminar attendees attributed this to lack of knowledge and adherence to traditional cultural beliefs, urging additional teaching:

"For the Sukuma, FP is a problem, for them to understand, there is need of more education." [Male church leader]

Several attendees also suggested separating men and women for portions of the seminar:

"You should start by having at least ten or twenty minutes with men and women differently, we are feeling shame to speak in front of men … or a man says, we can’t speak this in front of women, we are feeling shame … But if we are in different groups, it is easy to speak out. Even what we have said here would be impossible in front of men." [Female church leader]

Based on these suggestions, we refined our curriculum: men and women now participate together in initial teaching sessions, but are separated for group discussions led by a nurse and pastor of the same sex.

Discussion

Our focus group data and conceptual framework illustrate that low uptake of FP by women not desiring pregnancy is a multifaceted issue, and that a single-day educational seminar for Protestant church leaders holds promise for change. Our seminar was well-received and has been further refined based on community feedback. With these promising preliminary findings, we are now testing the seminar’s effectiveness as an intervention to promote uptake of FP on a larger scale.

A major strength of our intervention is its empowerment of respected church leaders to discuss FP with their communities. This informed outreach can overcome tenacious barriers to uptake of FP, including opposition by male partners/husbands and uncertainty of compatibility with religious faith. An additional strength is the contextual flexibility of our intervention. Leaders who attended the seminar subsequently reported providing targeted messages about FP to their communities in ways they perceived to be most effective and appropriate. This suggests that the seminar can be offered to leaders from a variety of denominations and, with some adaptation, from other religious traditions as well, further expanding the impact of this innovative intervention.

Our data demonstrate that post-intervention men and women church leaders experienced greater self-efficacy. They expressed confidence and desire to promote this same self-efficacy among community members. Higher self-efficacy, defined as one’s confidence in overcoming challenges to attain a goal,16 has been associated with increased use of oral contraceptives in many populations including among unmarried sexually active women in Mwanza.17–20 The study in Mwanza quantified a woman’s self-efficacy based on how able she felt to: (1) start a conversation with her partner about contraception; (2) obtain information on contraception; (3) obtain contraception if desired and (4) use FP even without partner approval. This suggests that increased self-efficacy can strongly affect interpersonal influences on use of FP.

This study has limitations. First, although we collected the original focus group data in both Christians and Muslim communities,6 the data revealed that an intervention with Muslims would need to be structured differently. We are now designing a curriculum to discuss Islamic teachings related to FP. Also, some of the positive post-seminar comments may be attributable to social desirability bias. Moreover, our pre-intervention focus group participants were church attendees while post-intervention participants were leaders who had attended the seminar. A comparison of pre- and post-intervention data from similar groups would strengthen our conclusions.

In summary, a framework based on the social action theory summarises multiple influences contributing to the decision to use FP. Many appear to have been strongly impacted by the 1-day educational seminar for Protestant church leaders. Post-intervention, church leaders reported revolutionised views on FP and described major changes in interpersonal interactions between couples, extended families, neighbours and church communities. Further, leaders reported persistently and impassionedly teaching about FP to their communities. We conclude that we have described a powerful, effective framework for increasing the uptake of FP in Tanzania and possibly in other similar contexts. Additional studies to determine the effectiveness of this intervention in decreasing unmet need for FP are warranted.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Veronica Selestine for the careful transcription and translation work. They also thank the focus group participants for their generosity with their time and for their honesty and courage in discussing potentially sensitive topics.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was made possible by the support of grants from the Weill Cornell Dean’s Diversity and Healthcare Disparity Research Award and the John Templeton Foundation.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the John Templeton Foundation. The funders had no role in the study design, analysis, manuscript writing, or decision to publish.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request. De-identified qualitative data are available to qualified researchers for defined research projects. Please submit requests to Christine Aristide (ORCID number 0000-0001-9109-0117).

References

- 1. Schummers L, Hutcheon JA, Hernandez-Diaz S, et al. Association of short interpregnancy interval with pregnancy outcomes according to maternal age. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:1661–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division World Family Planning 2017 - Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/414), 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cahill N, Sonneveldt E, Stover J, et al. Modern contraceptive use, unmet need, and demand satisfied among women of reproductive age who are married or in a union in the focus countries of the Family Planning 2020 initiative: a systematic analysis using the Family Planning Estimation Tool. Lancet 2018;391:870–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ministry of Health Community Development Gender Elderly and Children (MoHCDGEC); National Bureau of Statistics; Office of the Chief Government Statistician; and ICF Tanzania demographic and health survey 2015-2016. Rockville, MD, 2016. Available: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR321/FR321.pdf

- 5. Downs JA, Mwakisole A, Chandika AB, et al. Educating religious leaders to promote uptake of male circumcision in Tanzania: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet 2017;389:1124–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sundararajan R, Yoder M, Kihunrwa A, et al. How gender and religion impact uptake of family planning: results from a qualitative study in northwest Tanzania. BMC Womens Health 2019;19:99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ewart CK. Social action theory for a public health psychology. Am Psychol 1991;46:931–46. 10.1037/0003-066X.46.9.931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Weintraub A, Mellins CA, Warne P, et al. Patterns and correlates of serostatus disclosure to sexual partners by perinatally-infected adolescents and young adults. AIDS Behav 2017;21:129–40. 10.1007/s10461-016-1337-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ashton E, Vosvick M, Chesney M, et al. Social support and maladaptive coping as predictors of the change in physical health symptoms among persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2005;19:587–98. 10.1089/apc.2005.19.587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen E, Matthews KA, Salomon K, et al. Cardiovascular reactivity during social and nonsocial stressors: do children's personal goals and expressive skills matter? Health Psychol 2002;21:16–24. 10.1037/0278-6133.21.1.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lightfoot M, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Milburn NG, et al. Prevention for HIV-seropositive persons: successive approximation toward a new identity. Behav Modif 2005;29:227–55. 10.1177/0145445504272599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Downs JA, Dupnik KM, van Dam GJ, et al. Effects of schistosomiasis on susceptibility to HIV-1 infection and HIV-1 viral load at HIV-1 seroconversion: a nested case-control study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017;11:e0005968 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Downs JA, de Dood CJ, Dee HE, et al. Schistosomiasis and human immunodeficiency virus in men in Tanzania. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2017;96:16-0897–62. 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tanzania 2010: results from the Demographic and Health Survey. Stud Fam Plann 2012;43.1:69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pew Research Center Tolerance & tension: Islam and Christianity in Sub-Saharan Africa, 2010. Available: https://www.pewforum.org/2010/04/15/executive-summary-islam-and-christianity-in-sub-saharan-africa/

- 16. Richardson E, Allison K, Gesink D, et al. Barriers to accessing and using contraception in highland Guatemala: the development of a family planning self-efficacy scale. Open Access J Contracept 2016;7:77–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Heinrich LB. Contraceptive self-efficacy in college women. J Adolesc Health 1993;14:269–76. 10.1016/1054-139X(93)90173-M [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tomaszewski D, Aronson BD, Kading M, et al. Relationship between self-efficacy and patient knowledge on adherence to oral contraceptives using the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8). Reprod Health 2017;14:110 10.1186/s12978-017-0374-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Peyman N, Hidarnia A, Ghofranipour F, et al. Self-efficacy: does it predict the effectiveness of contraceptive use in Iranian women? East Mediterr Health J 2009;15:1254–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nsanya MK, Atchison CJ, Bottomley C, et al. Modern contraceptive use among sexually active women aged 15-19 years in north-western Tanzania: results from the adolescent 360 (A360) baseline survey. BMJ Open 2019;9:e030485 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kaida A, Kipp W, Hessel P, et al. Male participation in family planning: results from a qualitative study in Mpigi district, Uganda. J Biosoc Sci 2005;37:269–86. 10.1017/S0021932004007035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mosha I, Ruben R, Kakoko D. Family planning decisions, perceptions and gender dynamics among couples in Mwanza, Tanzania: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2013;13:523 10.1186/1471-2458-13-523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nalwadda G, Mirembe F, Byamugisha J, et al. Persistent high fertility in Uganda: young people recount obstacles and enabling factors to use of contraceptives. BMC Public Health 2010;10:530 10.1186/1471-2458-10-530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thummalachetty N, Mathur S, Mullinax M, et al. Contraceptive knowledge, perceptions, and concerns among men in Uganda. BMC Public Health 2017;17:792 10.1186/s12889-017-4815-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hartmann M, Gilles K, Shattuck D, et al. Changes in couples' communication as a result of a male-involvement family planning intervention. J Health Commun 2012;17:802–19. 10.1080/10810730.2011.650825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sharan M, Valente TW. Spousal communication and family planning adoption: effects of a radio drama serial in Nepal. Int Fam Plan Perspect 2002;28:16 10.2307/3088271 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yeatman S, Trinitapoli J. Beyond denomination: the relationship between religion and family planning in rural Malawi. Demogr Res 2008;19:1851–82. 10.4054/DemRes.2008.19.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]