Abstract

Clinical trials in oncology are an emergent field in sub-Saharan Africa. There is a long history of clinical trials in high-income countries (HICs), with increasing attempts to develop patient-centric approaches and to evaluate patient-centered outcomes. The challenge remains as to how these trends could be adopted in low-resource settings and adapted to best fit the different health ecosystems that coexist on the African continent. Models that evaluate patient-related outcomes and measures and that are used in HICs must be modified, adopted, and adapted to suit the diverse populations and the low-resource settings in most of the continent. Patient engagement in clinical trials in Africa must be well nuanced, and it demands innovation and application of models that consider established but tailored notions/principles of patient and community engagement and the unique sociocultural aspects of different populations. It also must be linked to strategies that aim to improve patient education, health literacy, and access to services and to encourage and protect patient autonomy.

INTRODUCTION

Clinical trials in oncology are an emergent field in sub-Saharan Africa. There is a long history of clinical trials in high income countries (HICs), with increasing attempts to develop patient-centric approaches and to evaluate patient-centered outcomes. The challenge remains as to how these trends could be adopted in low-resource settings and adapted to best fit the different health ecosystems that coexist on the African continent.

Clinical research is aimed at improvement in health and well-being. Conversely, more than 85% of research investment is perceived as wasted, and its outcome frequently is viewed as of little or no relevance to policymakers, practitioners, and even patients.1,2 Patient engagement in clinical research is regarded now as central to improving the return of investments and research outcomes. Patients bring in their rich experiences throughout the cancer trajectory. The incorporation of these experiences enables researchers to identify priority areas and to align the conception, design, conduction, and analysis of clinical trials to maximize benefit, avoid waste, and achieve real-world impact.

At the core of this rests the fundamental understanding of what truly constitutes patient-centric care. This type of care is defined by the US Institute of Medicine as “Providing care that is …… responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions.”3 Understanding how clinical trials can enhance patient engagement is an undertaking that can be learned from previous experiences in different health ecosystems.

Equally pivotal is the understanding of the role of patients in clinical trials. This is behind the notion that the patients want to know, in addition to wanting to be known. A successful strategy to implementing research would aim to address (1) how to manage fear, thus encouraging recruitment, and (2) how to foster comfort and trust, thus ensuring retention.

PATIENT ENGAGEMENT IN HIGH-RESOURCE COUNTRIES

In developed countries, with a long history of clinical trials, there has been a concerted effort to improve patient input. This effort mainly has centered around health-related quality of life for trial participants/survivors. This effort is part of a bigger shift in patient management that reports patient-reported outcomes.4 Although traditional surgical interventions, for instance, may have clearly demarcated end points like margin status or number of nodes, these end points do not adequately capture the patient’s experience of surgery. Chemotherapeutic end points, like tumor regression or a complete pathologic response, again fail to capture the lived experience of the patient going through these treatment strategies and their potential long-term adverse effects, such as neuropathy, functional impairment, and financial toxicity.5,6

Involving patients in clinical trials empowers them to get involved in their health and helps even out the balance of power. This encourages patients to go beyond the passive role and engage in active dialogues that bring about transformation and improvement in the health care experience. Viewed through this lens, the research process is about conducting a research with the patient rather than about, to, or for the patient.7

Engaging patients would help researchers know the proper questions to ask and what outcomes to assess and would inform good-quality data. After patients have information, they are likely to participate in clinical trials; therefore, recruitment is faster and more patients are retained. The patients also serve as advocates for friends and families to participate in more clinical trials.8,9 Involving patients in clinical trials also improves patient safety and increases risk-reduction efforts.10

The interpretation of patient-centered outcomes, such as PROMIS,6 involves a measurement or evaluation of a number of domains. A frequent ongoing challenge is the determination of what may constitute a minimally important difference that is likely to alter patient care or clinician practice.11,12 One of the oldest established outcomes is the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer outcome scores,13 which have been well validated in different populations and may serve as a potential template through which we can attempt to interpret the opportunities and challenges one might face in adapting to the African context.

CLINICAL TRIALS IN AFRICA

The clinical trial is not a new concept in Africa. Though trials are not conducted as robustly in African as in HICs, the development of clinical trials in Africa traditionally has occurred mainly in the setting of infectious diseases, like HIV and tuberculosis. This is not unexpected, given that the previous public health focus has been on infectious diseases. With the increase of diagnoses of cancers and other noncommunicable diseases, the public health focus is expanding, and critical lessons could be obtained from the experiences obtained in this space. The paucity of clinical trials on the continent has been attributed to the costs, complexity, and legal requirements required to run clinical trials.14 The cost of medications used in trials and the ability of populations to access these drugs have been additional barriers.15 There are little data specifically on patient engagement in these trials, but strategies to enhance retention, including use of technology to send messages, have been used with varying degrees of success.16-18

ONCOLOGY TRIALS IN LOWER- TO MIDDLE-INCOME COUNTRIES: STATUS AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR PATIENT ENGAGEMENT

Clinical trials in oncology in Africa are a fairly nascent concept, but the emerging field of patient-reported outcomes is starting to get traction. A number of studies on the continent have attempted to validate the EORTC outcome scores in their populations; studies out of Morocco and Ethiopia suggest a successful validation of the tool, although the application of it is not widespread.19, 20 There also have been attempts in Kenya to develop clinical trials that address the health-related quality of life after lymphedema for patients with Kaposi sarcoma.20a There has been a drive to consolidate efforts to improve clinical trials in Africa. There has been a considerable improvement in collaborations across multidisciplinary teams of biomedical scientists, leading to increased sharing of resources and infrastructure needed to conduct clinical trials. For instance, the Consortium for Advanced Research Training in Africa is a collaboration comprised of 13 academic institutions and research institutions across Africa aimed at facilitating and enhancing research along priority areas for countries in Africa and at increasing the pipeline of research scientists and their collective output. The Prostate Cancer Transatlantic Consortium of Nigeria has more than 15 institutions and 50 investigators in Nigeria. This group has established regional hubs to help improve access of researchers to funding opportunities, including external extramural funding, such as US National Institutes of Health grants. In southern Africa, the medical research council provides a regional hub for the training of researchers in clinical trials.

Efforts to enhance research capacity and infrastructure are also underway through developing collaborations with multiple stakeholders, including governments, not-for-profit organizations, academic institutions, and pharma. For instance, BIO Ventures for Global Health, a nonprofit global health organization, launched the African Access Initiative, which is a program that brings together oncology companies with governments and hospitals in Africa to foster cancer research and improve access to cancer treatment. Poor access to drugs is a major deterrent to completion of treatment and a cause of catastrophic health expenditure for patients, so these collaborations have helped improve provision of care to patients. In addition, the African Access Initiative has launched the African Consortium for Cancer Clinical Trials to develop cancer clinical trials led by investigators in Africa. This group aims to improve access to clinical trials for African patients and to develop the infrastructure, personnel, laboratories, and more to help support clinical trials. They also are encouraging their pharmaceutical partner companies and biomedical firms to invest in drug research and development in Africa. These efforts, along with other regional efforts, like the Clinton Health Access Initiative, through its partnership with local governments and the American Cancer Society, have increased the access to cancer drugs and treatment.

There are opportunities to broaden the scope of clinical trials and think beyond traditional existing models. There is an expanding role for community-based/participatory research, which could serve to create synergies with the traditional clinical trial model. The researcher must start to think about how to move the clinical trial out of the hospital and into the community, where the people are. As we embrace the increasing shift toward pragmatic trials, this starts to become increasingly relevant in the African context. However, this demands that the researcher adopts a less observational role. It also demands that the researcher start to think creatively and broadly about how clinical trials could serve as potential vehicles to help strengthen health systems. This would involve engaging with multiple stakeholders up front and leveraging preexisting systems; for instance, antenatal clinics could be used as a an entry portal for clinical trials in maternal and child health but also could be explored to see how systems and services in that unit could be improved.

In all efforts, value to the community and to the health system must be demonstrated consistently. Though one might be limited by the scope of funding, one always needs to consider the real-world setting in which the research is engaged. One cannot set up a laboratory that only serves to look at the blood values of patients in the study or only at specific parameters in a patient’s blood and ignore the fact that the patient may require additional evaluation for a coexistent condition. Instances have been reported in which state-of-the-art laboratories have been constructed in hospital units but only serve study patients, while the rest of the patients at the hospital have to travel long distances for laboratory services. The ethics of this continue to be called into question. No one is suggesting that the researcher should take on the role of policy maker and provide universal coverage, but one could certainly explore ways to increase the value of services by engaging with policy makers upfront. Engaging stakeholders and building critical steps that help to actively improve care as a result of one’s research is an imperative that we as clinical researchers should start to engage in actively.

CHALLENGES OR BARRIERS TO PATIENT ENGAGEMENT IN LOWER- TO MIDDLE-INCOME COUNTRIES

A number of challenges or barriers exist in sub-Saharan Africa that could potentially hinder the wholesale importation of models that work in HICs without due consideration for the social cultural nuances that may come into play when engaging with different health ecosystems.

The concept of vulnerability in clinical research is more defined in HICs though still debated.21 However, traditional definitions of vulnerability, such as level of literacy, poverty, and lack of access to medications and services, would place a substantial portion of patients with cancer in lower- to middle-income countries (LMICs) in the categories of vulnerable populations. There currently is no consensus about the definition of vulnerability in LMICs, and many ethical considerations would need to be delineated according to the changing landscape of societies in a state of transition—in addition to the recent considerations related to the problematic and harmful consequences of offshoring of clinical trials in Latin America, Africa, and other developing countries.22,23

The current preexistent patient-centered models demand a different level of health literacy and perhaps numeracy. In one country for instance, more than 40 local dialects may coexist. Patients may not necessarily be well versed with the national languages, which may form an additional hindrance to general literacy about health. Though health literacy is improving slowly, a considerable proportion of patients in many countries may come from rural settings and often may have little or no formal education. These low general literacy levels have a bearing on subsequent health literacy. This then begs the question of how one can design a trial model that is readily comprehensible to populations served and that respects the ethics of patient autonomy and dignity.

Patients frequently must travel long distances to access definitive care; as a result, a significant number of patients are unable to complete or frequently default on their treatment. Therefore, follow-up of patients is particularly challenging in the African setting. In addition, a number of populations are pastoral or migratory, which poses another challenge to patient engagement and retention. For instance, in unpublished data derived from a 5-year prospective breast cancer study conducted in Kenya, an initial recruitment of approximately 500 patients at a tertiary referral hospital showed that the follow-up rate at 2 years accounted for only approximately 60 patients.

Though technology presumably helps address some of these gaps through the development of digital solutions, there may also be certain drawbacks. For instance, with the Kenyan cohort, despite getting the mobile contacts of patients, the next of kin and family friends, patients themselves, and their other contacts frequently changed their numbers and often were untraceable. Even as we propose technologic advances as a potential panacea to address problems of recruitment and retention, we should start to think more profoundly about what other fundamental barriers to retention exist and what policies or innovative strategies could be used to overcome some of these hurdles.

As researchers, we must look inward and reflect on what viewpoints we bring to the table that could potentially increase our retention of patients. Incorporating the lens of health disparities research presents a corollary that could help anticipate challenges and provide a roadmap on how best to interpret the ongoing needs of populations studied in Africa.

As a researcher, a lack of knowledge about target communities generally is the first hurdle that many clinicians face. A lack of understanding of the data or perceptions around a particular community frequently will result in misunderstandings about the nature of research conducted. In addition, a lack of assessment of community needs, be they health literacy as already described or the unique culture of the community, will serve as stumbling blocks to patient engagement. For instance, in a number of societies, the approach to health decision making involves a collectivism approach. This means that health decisions are made as a group rather than by the individual. Engaging in a direct discussion with patients may not necessarily ensure automatic buy in unless discussed at the primary locus of decision making, which could be the immediate family, clan, or broader community. Inability to appreciate these nuances could result in dismal recruitment.

In addition, if one fails to define and attempt to address what the priorities of the patient or community are, it would be difficult to get buy in and engagement from these communities. A study on the adverse effects of chemotherapy, for instance, may be of interest to the researcher, but if the researcher fails to take on board the frequent pharmacy supply shortages leading to a lack of antinausea medication that could decrease compliance, then the recruitment outcome should not be unexpected. In addition, it is important to address the sociocultural barriers, such as stigma, that could act as barriers to care. University graduates in Uganda were reluctant to receive chemotherapy at a national referral center for fear of being identified as having cancer.24 The social fallout from a cancer diagnosis also must be considered. Data from Nigeria show a high correlation of family disintegration after a diagnosis of cancer: a divorce rate of approximately 40% was seen in patients with breast cancer within 3 years.25 Inability to address these fears, whether it is fear of losing a breast, fear of losing hair, or family disintegration, will ensure that recruitment and compliance to treatment are likely to be persistent concerns. Failing to build trust in a community, either through outsourcing of patient activities to nonengaged third parties, insufficient or nonexistent outreach staffing, or minimal commitment to consistent community presence will serve to destroy trust in a community setting.

ROLE OF RESEARCH ADVOCACY

As the clinical research system in Africa develops, research advocacy—loosely defined as patient advocates and their representatives meaningful engaged in the research system—which is a relatively new concept and activity on the continent, is taking root as a significant component in the overall research structure. That is, the current state of development of the research system and the simultaneous rise of patient advocacy are consistent and necessary for the development of strong, active, meaningful research advocacy. In a research system that supports patient advocacy, specifically research advocacy, there are increasing opportunities for patient engagement. In fact, as research advocates become more prepared and competent and as research advocacy becomes more significantly embedded in national and local research systems, there will be corresponding growth in opportunities for both patient engagement in research and influence on research.

Ongoing mechanisms and avenues for preparation are essential such that advocates will be ready to act on/take advantage of the opportunities to engage in research. This is in order for research advocacy to reach its potential to influence and help reshape cancer research, and thus for it to positively affect the cancer survival and survivorship landscape in Africa.

THE UNIQUE PERSPECTIVES OF PATIENT ADVOCATES IN RESEARCH

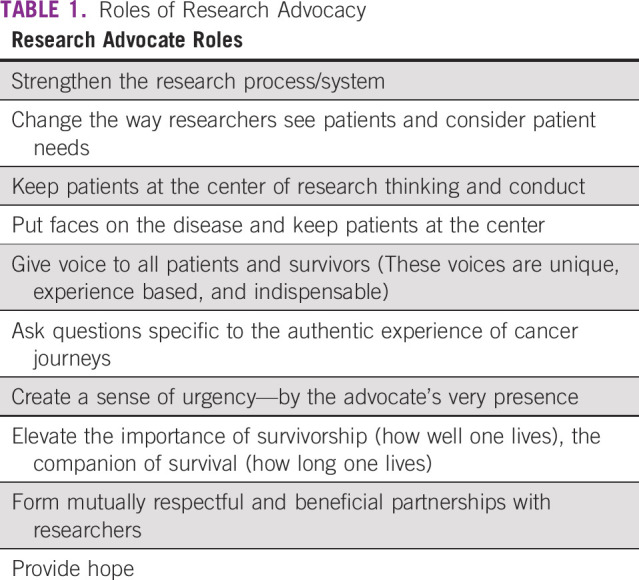

Just as clinicians and researchers bring specific expertise and value to the research process, patients engaged in research bring unique lived expertise and value—essential to development and monitoring of research systems responsive to local and regional patient needs, cultures, and imperatives.25 The role of research advocacy is highlighted in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Roles of Research Advocacy

SPECIFIC ADVOCACY OPPORTUNITIES

The types, routes, and extent of engagement will vary by region, country, culture, and people as well as by maturity of the research system and of patient advocacy. However, by learning from and generously borrowing from research advocacy as it has developed in the United States and other countries, advocates in Africa will engage in research in numerous ways, including the following:

on research grant review panels

on institutional review boards (which are required for research involving humans and must have community membership)

on government health- and cancer-related panels and board

in research studies (as study participants or research team members)

in community-based participatory research26

as community representatives for local research sites

with legislative bodies to affect funding and policy.

Both the actual opportunities to serve and the types of service will be tailored to the region and the population. That is, African advocates will cocreate, with others engaged in their unique research systems, appropriate, meaningful spaces and opportunities to most effectively serve within the context of their own environment, resources, needs, and other imperatives. Research advocacy in Africa is not simply international advocacy with an African face.

In conclusion, patient engagement in clinical trials in Africa must be well-nuanced engagement that demands that we innovate and apply a model that considers established but tailored notions/principles of patient engagement and the unique sociocultural aspects of different populations. It also must be linked to strategies that aim to improve patient education and health literacy and that encourage and protect patient autonomy. There is great anticipation that these patient-centered efforts will inform and engage both the patient and the research communities relative to the educational, psychological, and environmental needs of patients in creating a truly patient-centric imperative that meets the patient’s need to know and to be known in Africa.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Miriam Mutebi, Dicey Scroggins, Naomi Ohene Oti, Nazik Hammad

Collection and assembly of data: Virgil Simons

Provision of study material or patients: Virgil Simons

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/go/site/misc/authors.html.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Virgil Simons

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Tokai Pharmaceuticals

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wolfenden L, Ziersch A, Robinson P, et al. Reducing research waste and improving research impact. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2015;39:303–304. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalmers I, Glasziou P. Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:1341–1345. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c3020d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tzelepis F, Sanson-Fisher RW, Zucca AC, et al. Measuring the quality of patient-centered care: Why patient-reported measures are critical to reliable assessment. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:831–835. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S81975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clauser SB, Ganz PA, Lipscomb J, et al. Patient-reported outcomes assessment in cancer trials: Evaluating and enhancing the payoff to decision making. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5049–5050. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.5888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mooney K, Berry DL, Whisenant M, et al. Improving cancer care through the patient experience: How to use patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2017;37:695–704. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_175418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia SF, Cella D, Clauser SB, et al. Standardizing patient-reported outcomes assessment in cancer clinical trials: A patient-reported outcomes measurement information system initiative. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5106–5112. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thornton H. Patient and public involvement in clinical trials. BMJ. 2008;336:903–904. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39547.586100.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hanley B, Truesdale A, King A, et al: Involving consumers in designing, conducting, and interpreting randomised controlled trials: Questionnaire survey. BMJ 322:519-523, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9. Patient engagement in medical device clinical trials. 2018.

- 10.Alhassan RK, Nketiah-amponsah E, Spieker N, et al. Effect of community engagement interventions on patient safety and risk reduction efforts in primary health facilities: Evidence from Ghana. Plos ONE 10:e0142389, 2015 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Wyrwich KW, Bullinger M, Aaronson N, et al. Estimating clinically significant differences in quality of life outcomes. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:285–295. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-0705-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yost KJ, Eton DT, Garcia SF, et al. Minimally important differences were estimated for six Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System cancer scales in advanced-stage cancer patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:507–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer : XXXX. XXXX.

- 14.Vischer N, Pfeiffer C, Limacher M, et al. “You can save time if…”: A qualitative study on internal factors slowing down clinical trials in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0173796. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okpechi I, Swanepoel C, Venter F. Access to medications and conducting clinical trials in LMICs. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2015.6. Nat Rev Nephrol 11:189-194, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Wynne J, Muwawu R, Mubiru MC , et al: Maximizing participant retention in a phase 2B HIV prevention trial in Kampala, Uganda: The MTN-003 (VOICE) study. HIV Clin Trials 19:165-171, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Hanrahan CF, Schwartz SR, Mudavanhu M, et al. The impact of community- versus clinic-based adherence clubs on loss from care and viral suppression for antiretroviral therapy patients: Findings from a pragmatic randomized controlled trial in South Africa. PLoS Med. 2019;16:e1002808. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willis N, Milanzi A, Mawodzeke M, et al. Effectiveness of community adolescent treatment supporters (CATS) interventions in improving linkage and retention in care, adherence to ART and psychosocial well-being: A randomised trial among adolescents living with HIV in rural Zimbabwe. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:117. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6447-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ayana BA, Negash S, Yusuf L, et al. Reliability and validity of Amharic version of EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire among gynecological cancer patients in Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157359. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mrabti H, Amziren M, ElGhissassi I, et al. Quality of life of early-stage colorectal cancer patients in Morocco. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16:131. doi: 10.1186/s12876-016-0538-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20a. Chang AY, Karwa R, Busakhala N, et al: Randomized controlled trial to evaluate locally sourced two-component compression bandages for HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma leg lymphedema in western Kenya: The Kenyan Improvised Compression for Kaposi Sarcoma (KICKS) study protocol. Contemp Clin Trials Commun 12:116–122, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Bracken-Roche D, Bell E, Macdonald ME, et al. The concept of ‘vulnerability’ in research ethics: An in-depth analysis of policies and guidelines. Health Res Policy Syst. 2017;15:8. doi: 10.1186/s12961-016-0164-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. doi: 10.1007/s11673-014-9596-2. Spielman, B: Nonconsensual clinical trials: A foreseeable risk of offshoring under global corporatism. J Bioeth Inq 12:101-106, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Homedes N, Ugalde A. Health and ethical consequences of outsourcing pivotal clinical trials to Latin America: A cross-sectional, descriptive study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157756. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meacham E, Orem J, Nakigudde G, et al. Exploring stigma as a barrier to cancer service engagement with breast cancer survivors in Kampala, Uganda. Psychooncology. 2016;25:1206–1211. doi: 10.1002/pon.4215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Odigie VI, Tanaka R, Yusufu LM, et al. Psychosocial effects of mastectomy on married African women in Northwestern Nigeria. Psychooncology. 2010;19:893–897. doi: 10.1002/pon.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Odedina F, Asante-Shongwe K, Kandusi E, et al. Research advocacy: Principles and practices, in ” Rebbeck TR (ed): Handbook for Cancer Research in Africa. Brazzaville, Africa, World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa, 2013, pp130-136. [Google Scholar]