Abstract

Background & Aims

Wireless pH monitoring measures esophageal acid exposure time (AET) for up to 96 hrs. We evaluated competing methods of analysis of wireless pH data.

Methods

Adult patients with persisting reflux symptoms despite acid suppression (n=322, 48.5±0.9 y, 61.7% women) from 2 tertiary centers were evaluated using symptom questionnaires and wireless pH monitoring off therapy, from November 2013 through September 2017; 30 healthy adults (controls; 26.9±1.5 y; 60.0% women) were similarly evaluated. Concordance of daily AET (physiologic <4%, borderline 4%–6%, pathologic>6%) for 2 or more days constituted the predominant AET pattern. Each predominant pattern (physiologic, borderline, or pathologic) in relation to data from the first day, and total averaged AET, were compared with other interpretation paradigms (first 2 days, best day, or worst day) and with symptoms.

Results

At least 2 days of AET data were available from 96.9% of patients, 3 days from 90.7%, and 4 days from 72.7%. A higher proportion of patients had a predominant pathologic pattern (31.4%) than controls (11.1%; P=.03). When 3 or more days of data were available, 90.4% of patients had a predominant AET pattern; when 2 days of data were available, 64.1% had a predominant AET pattern (P<.001). Day 1 AET was discordant with the predominant pattern in 22.4% of patients and was less strongly associated with the predominant pattern compared to 48 hour AET (P=.059) or total averaged AET (P=.02). Baseline symptom burden was higher in patients with a predominant pathologic pattern compared to a predominant physiologic pattern (P=.02).

Conclusions

The predominant AET pattern on prolonged wireless pH monitoring can identify patients at risk for reflux symptoms and provides gains over 24 hr and 48 hr recording, especially when results from the first 2 days are discordant or borderline.

Keywords: GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease, diagnostic, prognostic

INTRODUCTION

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) develops when reflux of gastric content causes troublesome symptoms or complications.1 Pragmatic clinical management begins with empiric proton pump inhibitor (PPI) treatment2. Patients with persisting esophageal symptoms despite PPI therapy and no conclusively diagnostic findings on endoscopy (e.g. reflux esophagitis LA grade C-D, long segment Barrett’s esophagus) are evaluated further with ambulatory reflux monitoring to quantify esophageal acid burden.2–4 Standard trans-nasal catheter based pH- or pH-impedance testing is a well-established method to measure acid exposure time (AET), but are not feasible past 24 hours because of instability of pH sensors. Further, manometry is necessary for optimal placement of pH probes5, patient discomfort limits the length of monitoring to 24 hours,4, 6 and day-to-day variation in acid exposure influences performance characteristics when the measured AET is close to accepted normal thresholds7, 8.

Wireless pH technology was developed for extending pH monitoring for at least 48 hours; this is well tolerated and technically feasible, 6, 7 and increases the frequency of detecting pathologic AET, symptom reporting, and symptom associated probability (SAP).7–11 This may have particular value when 24-hour reflux monitoring demonstrates physiologic or borderline acid exposure despite a high suspicion for GERD9, 11. However, even with 48 hour monitoring, reflux burden may be variable despite a high clinical suspicion for GERD,6, 10, 12 especially with atypical presentations, infrequent symptoms, and low numbers of reflux episodes.9, 11, 13 To overcome this limitation, modern wireless pH technology allows up to 96 hours of pH monitoring, which increases the sensitivity of pH testing with modestly improved diagnostic yield8, 11, albeit with potentially lower specificity14. Indeed, the most appropriate method to analyze prolonged pH data remains unclear; while average total AET and ‘worst day’ approaches have been evaluated, impact on management decisions or outcome have not been assessed,11, 12, and comparisons of results from patients and healthy controls are available only in abstract form.11, 15

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate interpretation paradigms (e.g. averaged total AET, and predominant AET pattern) for prolonged pH monitoring beyond 48 hours of recording in patients referred for investigation of typical reflux symptoms poorly responsive to PPI therapy, with comparison to similar data acquired from healthy controls without symptoms. Secondary aims included assessment of the feasibility of prolonged pH monitoring, calculation of the diagnostic yield based on acid exposure metrics beyond 48 hours of monitoring, and prediction of symptom burden.

METHODS

Adult patients were prospectively recruited from two tertiary care academic centers (Northwestern University, Washington University in St. Louis) between November 2013 and September 2017 to undergo 96-hour wireless pH monitoring to investigate reflux symptoms poorly responsive to PPI therapy in this exploratory observational study. Exclusion criteria consisted of inability to place wireless pH capsule, lack of symptom data, unintelligible studies and absence of pH data past 24 hours of recording. This study protocol for data collection and analysis was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) at both institutions. Wireless pH data from patients was compared to that obtained prospectively from a healthy volunteer cohort from Nottingham Digestive Diseases Centre, Nottingham University NHS Trust under a study protocol approved by the NHS National Research Ethics Committee, UK. De-identified data sharing for analysis from both Northwestern University and Nottingham, UK was approved by the primary IRB (Washington University in St. Louis).

Patients

Patients included in this report were recruited from the outpatient offices, endoscopy suites and motility laboratories at Northwestern University, Chicago and Washington University in St. Louis and by two study investigators (JEP, CPG). Patients were included if presentation consisted of esophageal symptoms with incomplete response to acid suppressive therapy, hence requiring further evaluation off therapy. All patients had at least one typical symptom; however, patients with dominant typical and atypical symptoms were eligible. Patient demographics including age and gender, and clinical details including symptom, PPI dose, and frequency were recorded. Presenting symptoms were characterized using self-report symptom questionnaires including gastroesophageal reflux disease questionnaire (GERDQ), obtained off PPI therapy in all patients.16

Controls

Data from study patients were compared to that obtained from healthy asymptomatic volunteers recruited by advertisement at Nottingham University NHS Trust, UK. All healthy volunteers provided informed consent, and had no clinically significant gastrointestinal symptoms on validated questionnaires. Wireless pH studies were performed on the healthy cohort from June 2012- December 2012, data from which has been previously published.17

Wireless pH data

Wireless pH capsules (Medtronic, Duluth, GA) were placed endoscopically 6 cm above the squamo-columnar junction using standard methodology reported elsewhere7, 9. All wireless pH studies were performed after withholding acid suppressive medications including proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for at least 7 days; over the counter antacids were allowed for breakthrough symptoms till the day of the procedure, but not during the recording period5. Distal esophageal pH was monitored up to 4 days, and reported as percentage of time pH was <4% (AET); meals were excluded while calculating AET.7 Total AET was calculated separately for each day of the recording (physiologic <4%, borderline 4–6%, pathologic>6%) using the Lyon consensus thresholds.4, 18 AET was tracked across the duration of the study to determine concordance or discordance between study days. A predominant pattern was defined as ≥2 days with the same AET characterization regardless of study duration. All other patterns were considered discordant, including studies with two equal groupings of two AET classifications.

Statistical Analysis

Data are reported as the mean ± standard error of the mean, unless otherwise stated. Categorical data were compared using the χ-squared test; continuous data were compared using ANOVA or the 2-tailed Student’s t-test, as appropriate. Pearson correlation was used to correlate AET by various analysis paradigms. In all cases, p<0.05 was required for statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics V.25 (Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

A total 322 patients (48.5± 0.9 yrs, 61.7% F) and 30 asymptomatic healthy volunteer controls (26.9 ± 1.5 yrs, 60.0% F) were included in the study. Primary presenting symptoms included heartburn (45.2%), regurgitation (5.1%), chest pain (12.8%), cough (8%), dysphagia (3.4%), globus (4.3%), hoarseness (3.4%), and other (17.8%); however, all patients had at least one typical symptom. Overall, 269 patients completed the GERDQ questionnaire off PPI with a mean score of 7.83±0.3.

Feasibility

pH data were available for at least 2 days in 312/322 (96.9%) patients, 3 days in 292 (90.7%), and for all 4 days in 234 (72.7%). 6 patients had no data for any day of the study and were excluded. Only 30 patients did not have at least 3 days of pH data. Concurrent symptom data were incomplete in 53 patients. No adverse events were noted, and the prolonged studies were well tolerated. In controls, pH data were available in at least 2 days in 30 (100%), 3 days in 28 (93.3%), and for all 4 days in 25 (83.3%) (Table 1 & 2).

Table 1:

Feasibility of Prolonged pH Monitoring

| Patients (n=322) | Controls (n=30) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| At least 1 day data available | 316 (98%) | 30 (100%) | 1 |

| At least 2 day data pH available | 312 (96.9%) | 30 (100%) | 1 |

| At least 3 day data available | 292 (90.7%) | 28 (93.3%) | 1 |

| 4 day data available | 234 (72.7%) | 25 (83.3%) | 0.21 |

Table 2:

Clinical Characteristics of Predominant AET patterns when ≥3 days and a predominant pattern are available

| Predominant physiologic (n=167) | Predominant pathologic (n=83) | Predominant borderline (n=14) | Controls (n=27) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 47.8±1.2 yrs | 49.2±1.6yrs | 48.1±3.8yrs | 26.8±1.5yrs |

| Gender- %Female | 110 (66%) | 45(55%) | 8(57%) | 17(61%) |

| Heartburn | 73(43%) | 51(61%)* | 8(57%) | n/a |

| Typical Symptoms | 86(52%) | 60(72%)* | 9(64%) | n/a |

| GERDQ | 7.5±0.4** | 9.0±0.4* | 5.3±1.2 | n/a |

| Worst day AET >6.0%** | 40 (24%) | 83 (100%)* | 11 (79%) | 8(30%) |

| Best day AET <4.0%** | 167 (100%) | 40 (48%)* | 10 (71%) | 24(89%) |

| Worst Day AET 4%-6% | 31 (18.6%) | 0 | 3 (21%) | 4(15%) |

| Best Day AET 4%-6% | 0 | 12 (14%) | 4 (29%) | 1(4%) |

| Day 1 AET > 6.0% | 15 (9%) | 70 (84%)* | 4 (29%) | 5(19%) |

| Day 1 AET < | 132 (79%) | 7 (8%)* | 4 (29%) | 19(70.3%) |

| 4.0% | ||||

| 48 hour AET > 6.0% | 8 (5%) | 75 (90%)* | 4 (29%) | 4(15%) |

| 48 hour AET < 4.0% | 141 (84%) | 1 (1%)* | 4 (29%) | 17(63%) |

AET: acid exposure time.

p<0.05 compared to predominant physiologic

p<0.01 across all three groups

Total AET and Phenotypes

Proportions with pathologic, borderline and physiologic AET stayed similar when individual days of the study were separately analyzed, and when pH data from individual days were sequentially added (Table 3). When AET was cumulatively averaged across all available days of the study, 52.2% (165/316) of patients had a physiologic total AET (<4%), 17.1% (54/316) had borderline AET (4–6%), and 30.7% (97/316) had a pathologic AET (>6%). In comparison, 70% (21/30) of asymptomatic controls had physiologic AET, 20% (6/30) had borderline AET, and 10% (3/30) had pathologic AET (p=0.02 for proportion pathologic in patients vs controls). Proportions of patients with pathologic acid exposure were higher for all combinations of days when compared to controls.

Table 3.

Distribution of AET patterns across the duration of recording in patients

| 1 day | 2 days | 3 days | 4 days | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Days | ||||

| Physiologic <4% | 53.7% | 60.6% | 57.4% | 61.3% |

| Pathologic >6% | 34.0% | 28.1% | 30.6% | 29.4% |

| Borderline 4–6% | 12.3% | 11.3% | 12.0% | 9.3% |

| Cumulative Days | ||||

| Physiologic <4% | 53.7% | 54.7% | 53.2% | 52.2% |

| Pathologic >6% | 34.0% | 32.9% | 34.5% | 31.0% |

| Borderline 4–6% | 12.3% | 12.4% | 12.3% | 16.8% |

Predominant AET patterns

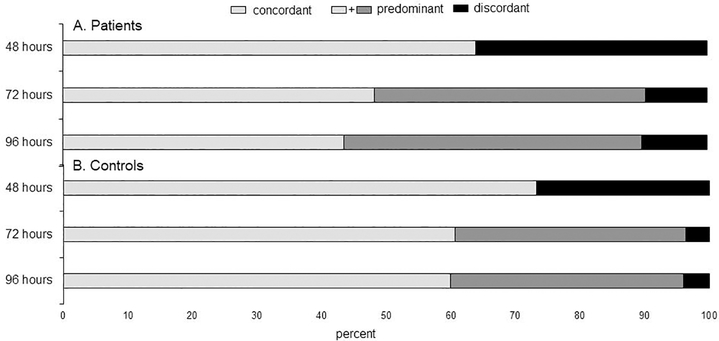

As the number of days of recording increased the number of patients and controls with a predominant AET pattern increased (p<0.01 for overall trend, Figure 1). When at least two days of data were available, AET from first 2 days (comparable to 48-hour wireless pH) was concordant between the 2 days in 64.1% of patients (200/312) and 73% of controls (22/30). In patients, a predominant pattern was identified in 89.7% (210/234) when 4 days of data were available, and in 90.4% (264/292) when ≥3 days available; corresponding numbers for controls were 96.0% (24/25) for 4 day data, and 96.4% (27/28) for ≥3 day data. If there were at least 3 days available, when day 1 and 2 were discordant, the remainder of the study allowed categorization into a predominant pattern in 85% (91/107; 48 physiologic, 31 pathologic, 12 borderline, p<0.05). In controls, when days 1 and 2 were discordant, the remainder of the study allowed categorization in 87.5% (5 physiologic, 1 borderline, and 0 pathologic, p>0.05).

Figure 1.

Frequency of concordant/predominant, and discordant patterns as the number of hours of pH monitoring increased from 48 to 96 hours in patients and controls. Concordant pattern: all days with same AET classification. Predominant pattern: ≥48 hours of the same AET classification. Discordant pattern: all other patterns. p<0.01 for trend of decreasing frequency of discordant patterns compared to concordant predominant pattern across groups, both for patients and controls

When 4 days were available in patients, 102/234 (43.6%) of studies had all 4 days with concordant AET; this occurred more often when physiologic (n=72) than when pathologic (n=29) or borderline (n=1), (p<0.01). Of 26 discordant cases with 3 days of data, fourth day data was available for 19 patients. Of these, with the fourth day data, 7/19 became predominant physiologic, 4/19 became predominant borderline, and 8/19 became pathologic, with none remaining discordant. When 4 days were available in controls, 15/25 (60%) had all 4 days with concordant AET; this occurred more often when physiologic (n=14) than when pathologic (n=1), and never when borderline (p<0.01).

Comparison of other analysis paradigms

24-hour AET

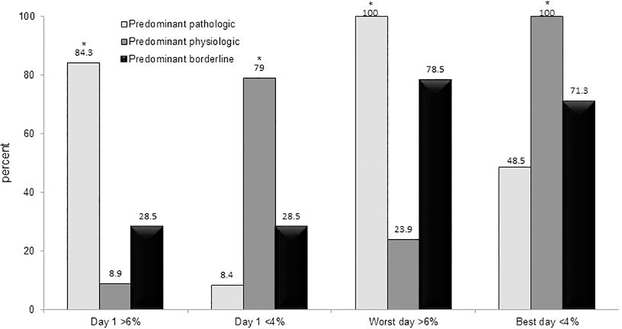

Day 1 AET pattern (comparable to 24-hour catheter based distal AET) was discordant with the predominant pattern in 22.4 % (59/264) of patients, and 14.8% (4/27) of controls (p=0.37 compared to patients). When day 1 was pathologic, 78.6% (70/89) remained pathologic for the remainder of the study (16.9% were predominant physiologic, 4.5% were predominant borderline; p<0.01 for trend) (Figure 2). In patients with a predominant pathologic pattern, 84% (70/83) had a first day AET>6%, while in patients with a predominant physiologic pattern 9% (15/167) had a first day AET >6% (p<0.01) (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Proportion of each predominant pattern with first day AET>6%, first day AET <4%, worst day (AET>6%), and best day (AET<4%).*p<0.05 for predominant pathologic compared to predominant physiologic

48-hour AET

The average AET from the first 48 hours (corresponding to standard wireless pH monitoring) corresponded to the predominant pattern in 84.1% of patients (222/264, p=0.059 compared to day 1 AET performance) and in 85.2% of controls (23/27, p=0.82 compared to patients). When the first 48 hours had a predominant pathologic pattern, 86.2% (75/87) remained pathologic for the remainder of study, while 9.2% (8/87) were physiologic, and 4.6% (4/87) were borderline (p<0.01 for trend). 90% (75/83) of patients with a predominant pathologic pattern had a 48-hour AET >6%, while 5% (8/167) of patients with a predominant physiologic pattern had a 48-hour AET >6% (p<0.05) (Table 2).

Best day AET

The best (lowest) AET corresponded to the predominant pattern in 76.5% of patients (202/264, p=0.76 compared to Day 1 AET, p=0.03 compared to first 48 hours) and in 81.5% of controls (22/27), (p=0.56 compared to patients). However, 48% (40/83) of patients with a predominant pathologic pattern had a best AET <4% on at least one day (Table 2). 76.9% (224/291) of patients with a best day AET <4% had a predominant physiologic pattern for the entire study, compared with 18.6% (54/291) with a predominant pathologic pattern and 4.5% (13/291) with a predominant borderline pattern (p <0.05 for trend) (Figure 2).

Worst day AET

The worst (highest) AET corresponded to the predominant pattern in 68.9% of patients (182/264, p=0.02 compared to day 1 AET; p<0.001 compared to first 48 hours, p=0.051 compared to best AET), and in 68.9% of controls (18/27; p=0.81 compared to patients). However, 24% (40/167) of patients with a predominant pathologic pattern had a worst day AET >6% (Table 2). 61.9% (106/171) of patients with a worst day AET >6% had a predominant pathologic pattern for the entire study, compared with 29.9% (51/171) with a predominant physiologic pattern and 8.2% (14/171) with a predominant borderline pattern (p <0.05 for trend) (Figure 2).

Total average AET

The total average AET corresponded well to the predominant pattern in 85.6% of patients (226/264, p=0.02 compared to day 1 AET, p<0.63 compared to first 48 hours, p=0.007 compared to best AET, p<0.001 compared to worst AET), and in 96.3% (26/27) of controls, (p=0.12 compared to patients).

Symptoms

Compared to a predominant physiologic pattern, patients with a predominant pathologic pattern were more likely to have heartburn as a primary symptom (61.4% (51/83) vs 43.7% (73/167); p<0.01), and typical reflux symptoms (72.3% (60/83) vs 51.5% (86/167); p=0.001). Baseline total GERDQ score was higher in those with a pathologic AET compared to physiologic AET with several analysis paradigms: day 1 AET (8.47±.43 vs 7.19±.42 respectively; p=0.042), worst day AET (8.55±.37 vs 6.46±.50; p=0.01), total average AET (8.73±.45 vs 7.32±.40; p=0.03), and predominant AET pattern (9.01±.43 vs 7.47±.40; p=0.02). Although numerically higher with pathologic AET, the difference in GERDQ scores was not statistically different using 48-hour AET (8.34±.43 vs 7.55±.39; p=0.19), or best day AET (9.03±.68 vs 7.59±.32; p=0.11).

DISCUSSION

In this prospective study, we demonstrate that prolonged (96 hour) wireless pH monitoring is feasible in the majority of individuals. We show significant gains over 24-hour and 48-hour monitoring in demonstrating a predominant AET pattern and establishing (or refuting) GERD diagnosis, particularly when AET was initially borderline, or discordant over the first two days of monitoring. Using a predominant AET pattern, addition of an additional day of recording increased the diagnostic yield from 64.1% from 48-hour to 90.4% with 72-hour data in patients with further gains in resolving discordance if 96-hour data is available. Similar results were observed in controls. Compared to healthy, asymptomatic controls, patients referred for investigation of suspected reflux symptoms were more likely to have pathologic average AET, and patients with predominant pathologic patterns over 3–4 days of testing had higher symptom burden compared to patients with predominant physiologic AET. In contrast, when worst day or best day AET was used to diagnose GERD, approximately 1 in 4 (22.4–30.5%) patients had subsequent day or average AET patterns that were discordant with this classification. Patients with a predominant pathologic AET pattern were more symptomatic, with more frequent typical reflux symptoms, compared to physiologic AET. We therefore conclude that prolonged wireless pH monitoring has value in clinical reflux monitoring, particularly in identifying a predominant reflux pattern, and that the diagnostic approach suggested by the Lyon consensus18 can be applied to prolonged wireless pH interpretation.

Since its introduction almost two decades ago, wireless pH monitoring has become a commonly utilized option for prolonged pH monitoring, with less interference of day-to-day activities and lower adverse events compared to catheter based pH monitoring 6, 19. When 96-hour pH monitoring was first studied, patients were required to bring their pH recorder back to the motility laboratory to exchange batteries, as battery life limited studies to 48 hours at a time. Extending battery life of the wireless pH receiver to 96 hours facilitates prolonged wireless pH monitoring; however, analysis paradigms have been incompletely studied. Averaged AET across the duration of the study, and days with abnormal AET have both been utilized20, 21. A recent study of 212 PPI non-responder patients undergoing prolonged pH monitoring described a novel trajectory model to categorize acid exposure22. In this study, three trajectories of acid exposure were identified (low, mid, and high), and grouping according to trajectory of acid exposure performed better than considering the number of days with abnormal AET22. While a useful and potentially a more precise model, trajectory modeling requires post-hoc statistical analysis and is not available as a real-world clinical tool22.

We present a new analysis model that considers a predominant pattern, using the diagnostic approach and AET thresholds described in the Lyon consensus18. A predominant pattern consists of ≥2 days with the same pattern of AET, be it pathologic (>6%), borderline (4–6%) or physiologic (<4%). We demonstrate that identification of a predominant pattern is facilitated by pH recordings that last ≥3 days, with only 10% or less of studies remaining discordant, and requiring adjunctive GERD evidence from alternate esophageal testing. While 3 day data appears to be adequate to characterize AET in most patients, the fourth day allows reduction of discordant cases at the end of 3 days into one or other of the predominant categories. Although, AET measurements from 48-hour recordings have clinical value, especially when pretest likelihood of GERD diagnosis is high. The added value of prolonged pH monitoring is that it allows conclusive diagnosis in a significantly larger proportion of patients, especially in those with discordant AET from the first two days of the study.

Importantly, the predominant pattern also predicted GERDQ score in subjects with pathologic acid exposure. We acknowledge that the GERDQ score reflects typical symptoms even in patients with atypical presentations; the need for ambulatory pH monitoring was based on symptoms that persisted despite PPI therapy, and it is likely that typical symptoms were exacerbated by withholding of PPI for the study. The higher symptom burden in physiologic acid exposure compared to the borderline group could represent functional heartburn, which can manifest with similar symptoms as proven GERD23. We demonstrate that the predominant AET pattern correlates with symptom information, and higher GERDQ scores were noted when the predominant pattern was pathologic, compared to physiologic patterns. Further, proportions with predominant pathologic acid exposure were higher in patients than in controls, and the converse was true for predominant physiologic acid exposure, as would be expected. Our study could not assess if discordant patients at the end of four days should be considered to have pathologic vs. physiologic acid burden; however, in this situation, the Lyon consensus recommends that adjunctive evidence from other investigations (e.g. endoscopy, manometry, impedance) can be utilized to make this determination18.

The strengths of this study lie in the large number of patients with prolonged wireless pH testing data available for at least 72 hours. Although a sample size was not calculated a priori in this exploratory study, analysis of published data12 indicates that 50 patients provide sufficient power to demonstrate a difference in diagnostic yield between 24 and 48 hour results in comparison to the 96 hour ‘reference’ standard. This exploratory study therefore recruited significantly higher than this number of patients, which allowed for multiple comparisons (pathological, borderline, physiological; individual days vs. total AET; best day vs. worst day data, etc.) and for technical failures. We did not evaluate PPI responders in this study as we could not justify performing endoscopy and pH monitoring in asymptomatic patients on PPI therapy. Symptom association during pH monitoring was not addressed in this study, as this is now deemed a secondary reflux metric to be used to further categorize reflux when AET is borderline24. Strength and dosing of PPIs were not assessed, and patients with atypical symptoms only were not included. Finally, outcome from therapy directed by the prolonged pH study was not part of the study protocol. This will be addressed in future studies. Despite these limitations, we demonstrate that analysis using a predominant AET pattern has value, and associates with symptoms off PPI therapy.

In summary, we demonstrate that prolonged wireless pH monitoring has clinical value, and acid burden from prolonged studies associates with the presence and severity of reflux symptoms off therapy. Using a predominant AET pattern provides clarity regarding acid burden and increases the proportion of patients with a conclusive diagnosis based on pH monitoring, particularly when AET is discordant or borderline in the initial 1–2 days of the recording.

Need to Know.

Background

Wireless pH monitoring provides prolonged evaluation of esophageal reflux burden, including daily variations, in patients with persistent symptoms despite medical therapy.

Findings

Two days or more days of either of pathologic or physiologic AET (predominant AET pattern) can be determined in more than 90% of patients and healthy individuals on prolonged wireless pH monitoring performed off therapy, which correlates with the severity of esophageal symptoms on validated questionnaires.

Implications for patient care

When wireless pH monitoring lasts 3 or more days, a predominant AET pattern from prolonged pH monitoring provides gains over 24 hr and 48 hr pH data in phenotyping patients with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease—especially when results from shorter monitoring durations are borderline or discordant.

Acknowledgments

No conflicts of interest exist. This study was partially funded through NIH/NIDDK (SH:T32DK007130 and P30DK052574; RY: T32DK101363; JEP:R01: DK092217)

Disclosures:

SH, OA, ET, KK: no disclosures

RY: consultant for Medtronic, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, and Diversatek

RS: educational grant support from Medtronic

MF: research and/or educational grant support from Medtronic, Diversatek and Laborie, consultant for Mui Scientific and Reckitt Benckiser

JEP: consultant for Medtronic, Diversatek, Torax, Ironwood, Takeda, and Astra Zeneca, research support from Impleo; stock options with Crospon

CPG: consultant for Medtronic, Diversatek, Torax, Ironwood, Isothrive and Quintiles, speaker for Medtronic and Diversatek

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, et al. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:1900–20; quiz 1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:308–28; quiz 329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Savarino E, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, et al. Expert consensus document: Advances in the physiological assessment and diagnosis of GERD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;14:665–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roman S, Gyawali CP, Savarino E, et al. Ambulatory reflux monitoring for diagnosis of gastro-esophageal reflux disease: Update of the Porto consensus and recommendations from an international consensus group. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2017;29:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roman S, Gyawali CP, Savarino E, et al. Ambulatory reflux monitoring for diagnosis of gastro-esophageal reflux disease: Update of the Porto consensus and recommendations from an international consensus group. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sweis R, Fox M, Anggiansah R, et al. Patient acceptance and clinical impact of Bravo monitoring in patients with previous failed catheter-based studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;29:669–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pandolfino JE, Richter JE, Ours T, et al. Ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring using a wireless system. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:740–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Penagini R, Sweis R, Mauro A, et al. Inconsistency in the Diagnosis of Functional Heartburn: Usefulness of Prolonged Wireless pH Monitoring in Patients With Proton Pump Inhibitor Refractory Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2015;21:265–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prakash C, Clouse RE. Value of extended recording time with wireless pH monitoring in evaluating gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;3:329–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tseng D, Rizvi AZ, Fennerty MB, et al. Forty-eight-hour pH monitoring increases sensitivity in detecting abnormal esophageal acid exposure. J Gastrointest Surg 2005;9:1043–51; discussion 1051–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sweis R, Fox M, Anggiansah A, et al. Prolonged, wireless pH-studies have a high diagnostic yield in patients with reflux symptoms and negative 24-h catheter-based pH-studies. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2011;23:419–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scarpulla G, Camilleri S, Galante P, et al. The impact of prolonged pH measurements on the diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease: 4-day wireless pH studies. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:2642–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prakash C, Clouse RE. Wireless pH monitoring in patients with non-cardiac chest pain. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:446–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Connor J, Richter J. Increasing yield also increases false positives and best serves to exclude GERD. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:460–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fox M, Canavan R, Anggiansah A, et al. What is the optimal duration of oesophageal pH measurement and symptom assessment? a prospective study using 96hr BRAVO recordings. Gastroenterology 2007;132 (supplement 1):A-99 692. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones R, Junghard O, Dent J, et al. Development of the GerdQ, a tool for the diagnosis and management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in primary care. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;30:1030–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tucker E, Sweis R, Anggiansah A, et al. Measurement of esophago-gastric junction cross-sectional area and distensibility by an endolumenal functional lumen imaging probe for the diagnosis of gastro-esophageal reflux disease. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2013;25:904–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gyawali CP, Kahrilas PJ, Savarino E, et al. Modern diagnosis of GERD: the Lyon Consensus. Gut 2018;67:1351–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iluyomade A, Olowoyeye A, Fadahunsi O, et al. Interference with daily activities and major adverse events during esophageal pH monitoring with bravo wireless capsule versus conventional intranasal catheter: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Dis Esophagus 2017;30:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Capovilla G, Salvador R, Spadotto L, et al. Long-term wireless pH monitoring of the distal esophagus: prolonging the test beyond 48 hours is unnecessary and may be misleading. Dis Esophagus 2017;30:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chae S, Richter JE. Wireless 24, 48, and 96 Hour or Impedance or Oropharyngeal Prolonged pH Monitoring: Which Test, When, and Why for GERD? Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2018;20:52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yadlapati R, Ciolino JD, Craft J, et al. Trajectory assessment is useful when day-to-day esophageal acid exposure varies in prolonged wireless pH monitoring. Dis Esophagus 2019;32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weijenborg PW, Smout AJ, Bredenoord AJ. Esophageal acid sensitivity and mucosal integrity in patients with functional heartburn. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2016;28:1649–1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gyawali CP, de Bortoli N, Clarke J, et al. Indications and interpretation of esophageal function testing. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2018;1434:239–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]