Abstract

Objectives:

The present study examined the associations between immigration-related factors and objective and subjective cognitive status with older Korean Americans’ concern about developing Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). It was hypothesized that (1) AD concern would be associated with immigration-related factors and (2) self-rated cognitive status would mediate the relationship between cognitive performance (Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores) and concern about AD.

Method:

Using data from the Study of Older Korean Americans (n = 2,061, mean age = 73.2; 66.8% female), the direct and indirect effect models were tested.

Results:

Korean American immigrants with a higher level of acculturation had better cognitive performance, more positive self-ratings of cognitive status, and a lower level of concern about AD. Both poor cognitive performance and negative self-ratings of cognitive status were associated with increased concern about AD. Supporting the mediation hypothesis, the indirect effect of cognitive performance on AD concern through self-rated cognitive status was significant (bias corrected 95% confidence interval for the indirect effect = −.012, −.003).

Conclusion:

The mediation model not only helps us better understand the psychological mechanisms that underlie the link between cognitive status and AD concern but also highlights the potential importance of subjective perceptions about cognitive status as an avenue for interventions.

Keywords: cognitive health, concerns about Alzheimer’s disease, older Korean Americans

Introduction

An estimated 5.8 million Americans currently live with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), with this number projected to reach 14 million by 2050 (Alzheimer’s Association, 2019). After cancer, AD is the most feared disease among Americans (Harris Interactive, 2011). Nearly one in three Americans fear getting AD, and three in five have some level of concern regarding the provision of care for a loved one with AD. This high level of concern may be partly attributed to government initiatives to promote AD awareness and media coverage of AD. It is also suggested that public awareness of a lack of effective treatments available to cease, reverse, or delay the progression of AD precipitates concerns about AD (James & Bennett, 2019).

Often identified with anticipatory dementia and perceived threat (e.g., Cutler & Hodgson, 1996; Norman et al., 2018; Suhr & Kinkela, 2007; Sun, Gao, & Coon, 2013; Werner & Davidson, 2004), concern about developing AD may elicit negative emotions such as anxiety and fear. One factor that may underlie a person’s concern about AD is his or her own cognitive status. Studies have demonstrated that older individuals who are experiencing problems with memory and concentration are likely to worry about getting AD (Cutler & Hodgson, 1996; Cutler, 2015; Suhr & Kinkela, 2007). Kessler and colleagues (2012), however, suggest that AD concern is a specific category of health worry that reflects an individual’s emotional response to the perceived threat of developing AD rather than actual cognitive impairment. In other words, subjective appraisals of cognitive status might be more influential than the mere presence of cognitive impairment.

The importance of subjective appraisals of health is indeed generally recognized. As noted in the Health Belief Model (HBM; Rosenstock, 1974; see also Jones et al., 2015), subjective perceptions of disease susceptibility are an important social-cognitive factor that determines individuals’ health and health-related outcomes. However, the associations between objective and subjective cognitive status and their impact on AD-related concerns have rarely been explored. While concerns about AD may trigger negative emotions, there is evidence that positive behavioral outcomes can result from AD concerns (e.g., Cutler, 2015; Sayegh & Knight, 2013; Tang et al., 2017). For example, Tang and colleagues (2017) found that older individuals who worried about AD were more willing to be screened for AD than those without worry. Overall, previous findings in this area call attention to a better understanding of AD concern as a potential avenue for early detection and efficient management of AD.

Older Asian Americans are one of the fastest growing segments of the U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). However, information on their AD-related issues is scarce (Jang, Yoon, Park, Rhee, & Chiriboga, 2018). Because a majority of older Asian Americans are foreign-born immigrants with limited English proficiency, they are often underrepresented in national surveys, and what is known about their AD-related issues is based on small community- based samples of Asian subgroups (e.g., Casado, Hong, & Lee, 2017; Jang, Kim, & Chiriboga, 2010; Sun et al., 2013). Although the latter studies may not generalize to all Asian Americans, their use of culturally and linguistically sensitive approaches not only show that underrepresented groups can be reached but also demonstrate the importance of considering cultural beliefs and attitudes toward AD.

In a recent study with six ethnic groups of Asian Americans aged 18 years and older, about 18% of the entire sample reported a concern for developing AD, ranging from 8.7% among Asian Indians to 29% among Koreans (Jang et al., 2018). Given the ethnic diversities among Asian Americans, the notable vulnerability to AD concerns among Korean Americans, and the particular relevance of the issue to the older population, the present study focused on exploring factors associated with AD-related concerns among older Korean Americans. We defined Korean Americans as individuals who immigrated to the U.S. from Korea regardless of their current citizenship status.

The conceptualization of immigration-related factors in the present study was guided by the Sociocultural Health Belief Model (SHBM; Sayegh & Knight, 2013). As a variation of the general HBM (Rosenstock, 1974), this model provides an appropriate theoretical framework to examine perceptions of health in ethnic minorities. According to the SHBM, cultural factors, including values, beliefs, and acculturation, influence how individuals interpret the meaning of health and how they perceive their susceptibility to disease. Previous research (e.g., Lee, Lee, & Diwan, 2010; Jang et al., 2010) found that a lower level of acculturation among Korean Americans was related to poorer knowledge about AD. Sun and colleagues (2013) found that older Chinese Americans who held more traditional cultural beliefs about AD were more likely to have a greater perceived threat of AD. Therefore, we hypothesized that immigration-related factors (e.g., length of stay in the U.S. and the level of acculturation) would influence AD concern in older Korean Americans. Specifically, we predicted that those with longer residence in the U.S. and higher levels of acculturation would have a lower level of AD concern.

To explore the associations between objective and subjective cognitive status and AD concern, we included self-rated cognitive status as a potential mediator of the relationship between cognitive performance and concern about AD. Self-rated cognitive status refers to one’s perception and evaluation of his/her cognitive health status (Flavell, 1975). Self-rated cognitive status has been shown to be an important indicator of objective cognitive status in diverse populations (e.g., Bruce et al., 2008; Fastame & Penna, 2014; Lai, Wagner, Jacobsen, & Cella, 2014), including older Korean Americans (e.g., Jang et al., 2019). We hypothesized that the effect of cognitive performance on concern about AD would be mediated by self-rated cognitive status. Specifically, poor cognitive performance would be associated with more negative self-ratings of cognitive status, which will, in turn, lead to a greater level of concern about AD. This mediating role is also aligned with the HBM and SHBM (Rosenstock, 1974; Sayegh & Knight, 2013) and related health literature demonstrating the importance of subjective health appraisals over objective health conditions (Jang, Chiriboga, Borenstein, Small, & Mortimer, 2009; Jones et al., 2015; Kahana et al., 1995).

To place the key variables in context, we also considered demographic characteristics (age, gender, marital status, and education), prior exposure to AD (having a family member or friend affected by AD), and general health (chronic medical conditions and functional disability) as control variables. The variable selection was based on literature on cognitive status and AD-related issues in older adults, in general (e.g., Cutler & Hodgson, 1996; Cutler, 2015; Suhr & & Kinkela, 2007), and ethnic immigrants, in particular (e.g., Casado et al., 2017; Jang et al., 2010, 2018; Sun et al., 2013). The mediating role of self-rated cognitive status was expected to shed light on how personal concerns about AD are linked to both objective and subjective measures of cognitive status and provide practical implications.

Method

Sample

Data were drawn from the Study of Older Korean Americans (SOKA), a multi-state survey of Korean immigrants living in the United States, aged 60 years or older. To increase eneralizability of findings, the SOKA drew data from states with differing proportions of Korean immigrants: California, New York, Texas, Hawaii, and Florida. Their respective proportions included 29.3%, 8.0%, 5.2%, 2.7%, and 2.2% of the total Korean population in the U.S. (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). In each state, a primary metropolitan area with a representative proportion of Korean Americans was selected as a study site: Los Angeles, New York City, Austin, Honolulu, and Tampa. Combined, these sites present a continuum of Korean population densities.

The community-based samples were recruited by a team of investigators who shared the language and culture of the target population. The project began by compiling a database of orean-oriented resources, services, and amenities at each of the five study sites. This database not only facilitated the research team’s community engagement but also guided the selection of specific locations for data collection. In the development and use of these ethnic resource databases at each site, local community advisor input was actively solicited. At each of the five sites, surveys took place at multiple locations and events (e.g., churches, temples, grocery stores, small group meetings, and cultural events) from April 2017 to February 2018. Data collection ontinued until the targeted sample size at each site was met. Sample size targets were based on the Korean population density at each site (ranging from 300 to 600). The 12-page questionnairewas in Korean, developed through a back-translation and reconciliation method.

The survey was designed to be self-administered, but trained interviewers were onsite for anyone who needed assistance. Participants were each paid US $20 for participation. The project was approved by a University’s Institutional Review Board. All participants were informed of the study purposes and procedures before signing a consent form. A total of 2,176 individuals participated in the survey. After removal of those who had more than 10% of data missing from he study variables (n = 111) or whose cognitive performance indicated severe impairment (Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score <10; n = 4), the final sample consisted of 2,061 participants. No imputation on missing data was conducted.

Measures

Concern about AD

The single question used to assess level of concern about AD (“How concerned are you that you may have Alzheimer’s disease someday?”) was taken from the MetLife Foundation Alzheimer’s survey (Harris Interactive, 2011). The responses were coded on a four-point scale: not at all (1), not very much (2), somewhat (3), and very much (4).

Cognitive performance

Upon completion of the self-report survey, trained research personnel assessed each participant for cognitive function using the MMSE (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975). The MMSE includes items on time and place orientation, memory recall, attention and computation capabilities, language ability, three-stage command, pentagon drawing, judgment, and comprehension. Responses for each item were scored 1 for a correct answer or 0 for an incorrect answer, and the individual item scores were summated. The total score ranged from 0 to 30, with a higher score indicating better cognitive performance. The psychometric properties of the Korean version of the MMSE have been validated with samples of Koreans and Korean Americans (e.g., Kim et al., 2010). Internal consistency in the present sample was satisfactory (α = .73).

Self-rated cognitive status

Perceived cognitive health status was measured with a single question: How would you rate your cognitive health? Responses were rated on a five-point scale: poor (1), fair (2), good (3), very good (4), or excellent (5).

Immigration-related variables

To assess immigration-related factors, participants were asked how many years they had lived in the U.S. and level of acculturation was assessed with a 12-item inventory (Jang, Kim, Chiriboga, & King-Kallimanis, 2007). Acculturation questions addressed English proficiency, media consumption, food consumption, social relationships, sense of belonging, and familiarity with culture and custom. Each item was coded from 0 to 3, and total scores could range from 0 to 36, with a higher score indicating a greater level of acculturation to mainstream American culture. Internal consistency in the present sample was high (α = .91).

Background variables

Demographic characteristics assessed were age (in years), gender (0 = male, 1 = female), marital status (0 = married, 1 = not married), and education (0 = ≤ high school graduation, 1 = > high school graduation). Prior exposure to AD was measured by asking participants if they had a family member or friend affected by AD (0 = no, 1 = yes).

General health variables included chronic medical conditions (a total count from a list of 10 chronic diseases and conditions such as heart disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer, and arthritis). Functional disability was indexed by a composite measure of basic and instrumental activities of daily living (Fillenbaum, 1988). Participants were shown a list of 16 activities (e.g., eating, dressing, traveling, and managing medication) and asked whether they could perform each activity without help (0), with some help (1), or unable to do so (2). Total scores could range from 0 (no disability) to 32 (severe disability), and internal consistency was high in the present sample (α = .89).

Analytic strategy

After reviewing descriptive characteristics of the sample, bivariate correlations were assessed to understand the underlying relationships among the variables and to ensure the absence of collinearity. Multivariate linear regressions were performed with concern about AD as the outcome variable. All other variables were entered in the following sequence: background variables, immigration-related variables, cognitive performance, and self-rated cognitive status. The hypothesis that the effect of cognitive performance on concern about AD would be mediated by self-rated cognitive status was tested using the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2009, 2013). The 95% confidence intervals for the indirect effects were estimated using 10,000 bootstrap samples. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

Descriptive characteristics of the sample

Table 1 describes the overall characteristics of the sample and study variables. The mean age of the sample was 73.2 years (SD = 7.93). Participants tended to be female and married, with high school graduation or lower education. Participants had lived in the U.S. for an average of 31.4 years (SD = 12.1), but acculturation scores were relatively low. Over one third of the sample rated their cognitive status as either fair or poor, and over half reported that they were either somewhat or very much concerned that they might have Alzheimer’s disease someday. The distribution of scores for concern about AD was close to normal, with skewness of −0.08 (SE = 0.05) and kurtosis of −0.86 (SE = 0.10).

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of the Sample (n = 2,061)

| % | M ± SD (actual range) |

|---|---|

| Age | 73.2 ± 7.93 (60–100) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 33.2 |

| Female | 66.8 |

| Marital status | |

| Not married | 39.2 |

| Married | 60.8 |

| Education | |

| ≤High school graduation | 60.3 |

| >High school graduation | 39.7 |

| Prior exposure to AD | 18.9 |

| Chronic medical conditions | 1.57 ± 1.40 (0–10) |

| Functional disability | 1.67 ± 3.42 (0–32) |

| Length of stay in the U.S. | 31.4 ± 12.1 (0.17–80) |

| Acculturation | 12.2 ± 7.06 (0–35) |

| Cognitive performance (MMSE score) | 26.7 ± 2.91 (10–30) |

| Self-rated cognitive status | 3.15 ± 1.13 (1–5) |

| Poor | 6.4 |

| Fair | 26.8 |

| Good | 24.0 |

| Very good | 31.3 |

| Excellent | 11.5 |

| Concern about Alzheimer’s disease | 2.49 ± 0.93 (1–4) |

| Not at all | 6.9 |

| Not very much | 31.1 |

| Somewhat | 38.1 |

| Very much | 14.0 |

Bivariate correlations among study variables

At a bivariate level, the variables were correlated in the expected direction, and no signs of collinearity were detected (Table 2). The highest correlation coefficient was a positive relationship between the length of stay in the U.S. and acculturation (r = .42, p < .001). The significant correlates of cognitive performance and self-rated cognitive status were similar. Both better performance on the MMSE and higher perceived cognitive status were associated with younger age, male gender, married status, higher educational attainment, fewer chronic medical conditions, lower levels of functional disability, longer residence in the U.S., and greater levels of acculturation. The correlation between MMSE scores and self-rated cognitive status was significant but modest (r = .25, p < .001). Greater concern about AD was associated with female gender, unmarried status, lower education, prior exposure to AD, more chronic medical conditions, greater levels of functional disability, and lower acculturation. AD concern had the strongest correlation with self-rated cognitive status (r = −.29, p < .001) while its association with cognitive performance was significant but comparatively weak (r = −.09, p < .001).

Table 2.

Correlations among Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | ||||||||||||

| 2. Female | −.12*** | |||||||||||

| 3. Married | −.23*** | −.25*** | ||||||||||

| 4. >High school graduation | −.07** | −.29*** | .16*** | |||||||||

| 5. Prior exposure to AD | .01 | .07** | .01 | .05* | ||||||||

| 6. Chronic medical conditions | .27*** | .11*** | −.16*** | −.17*** | .06** | |||||||

| 7. Functional disability | .33*** | .11*** | −.19*** | −.16*** | .02 | .32*** | ||||||

| 8. Length of stay in the U.S. | .17*** | −.00 | −.02 | .13*** | .06** | .10 | −.04 | |||||

| 9. Acculturation | −.21*** | −.10*** | .21*** | .36*** | .07** | −.25*** | −.26*** | .42*** | ||||

| 10. Cognitive performance | −.37*** | −.13*** | .24*** | .29*** | .04 | −.21*** | −.29*** | .05* | .30*** | |||

| 11. Self-rated cognitive status | −.16*** | −.10*** | .15*** | .26*** | −.01 | −.24*** | −.24*** | .13*** | .37*** | .25*** | ||

| 12. Concern about AD | −.03 | .16*** | −.06** | −.07** | .13*** | .17*** | .12*** | −.03 | −.14*** | −.09*** | −.29*** | |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001

Regression models of concern about AD

Table 3 presents the results of the regression models for concern about AD. In the initial model, a set of background variables accounted for 6% of the variance in AD concern. Younger age, female gender, prior exposure to AD, more chronic medical conditions, and greater levels of functional disability were predictive of a high level of AD concern. The subsequent model with immigration-related factors explained an additional 2% of the variance, with acculturation emerging as a significant predictor. Lower levels of acculturation were associated with higher concern about AD. The entry of cognitive performance added a significant but small amount of variance (1%) to the model; better cognitive performance was associated with a lower level of AD concern. In the final model, the single measure of self-rated cognitive status accounted for an additional 5% of the variance. Positive self-ratings of cognitive status were associated with a lower level of concern about AD. The effect of cognitive performance became non-significant with the entry of self-rated cognitive status, suggesting that self-rated cognitive status potentially mediates the relationship cognitive performance and AD concern. The total amount of variance explained in the direct effect model was 14%.

Table 3.

Regression Models of Concern about Alzheimer’s Disease

| B (SE) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Background variables | ||||

| Age | −.01*** (.00) | −.01*** (.00) | −.01*** (.00) | −.01*** (.00) |

| Female | .23*** (.04) | .22*** (.05) | .22*** (.05) | .21*** (.05) |

| Married | −.03(.04) | −.01(.04) | −.00(.05) | .00 (.04) |

| >High school graduation | .02 (.04) | .04 (.04) | .06 (.05) | .11* (.05) |

| Prior exposure to AD | .27*** (.05) | .29*** (.05) | .30*** (.05) | .28*** (.05) |

| Chronic medical conditions | .09*** (.01) | .08****** (.02) | .08*** (.01) | .06*** (.01) |

| Functional disability | .02*** (.01) | .02** (.01) | .02** (.01) | .01 (.01) |

| Immigration-related variables | ||||

| Length of stay in the U.S. | .00 (.00) | .00 (.00) | .00 (.00) | |

| Acculturation | −.02*** (.00) | −.02*** (.00) | −.01** (.00) | |

| Objective cognitive status | ||||

| Cognitive performance | −.02* (.01) | −.01 (.01) | ||

| Subjective cognitive status | ||||

| Self-rated cognitive status | −.21*** (.02) | |||

| ΔR2 | .06*** | .02*** | .01* | .05*** |

| Overall R2 | .06*** | .08*** | .09*** | .14*** |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001

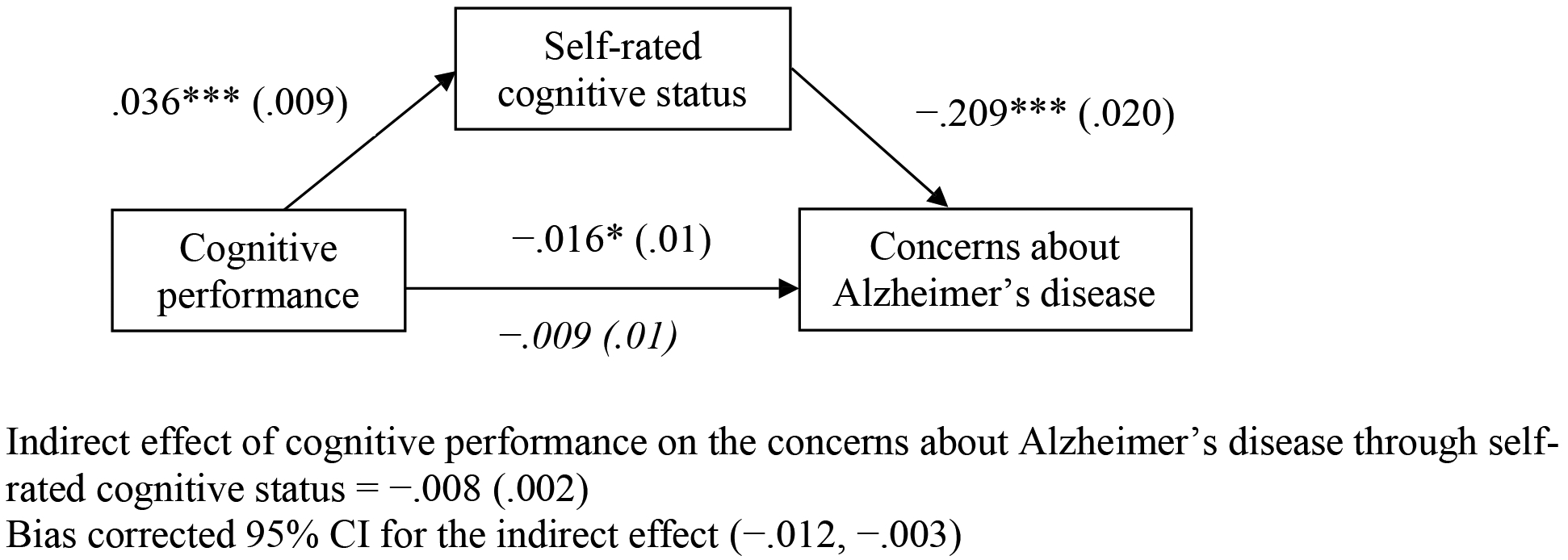

Mediating effect of self-rated cognitive status

The mediation model of self-rated cognitive status was further explored, and findings are summarized in Figure 1. All direct paths among the independent variable (cognitive performance), presumed mediator (self-rated cognitive status), and dependent variable (concern about AD) were significant. The indirect effect of cognitive performance on concern about AD hrough self-rated cognitive status was significant (B [SE] = −.008 [.002]), as evidenced by the 95% bootstrap confidence interval for the indirect effect not containing zero (−.012, −.003). The finding suggests that subjective evaluations of cognitive status intervene in the effect of cognitive performance on AD concern. Poor cognitive performance was associated with negative self-rated cognitive status, which in turn, predicted a higher level of concern about AD.

Figure 1.

Mediating effect of self-rated cognitive status

Note. Numbers indicate unstandardized regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. Analyses were conducted after controlling age, gender, marital status, education, prior exposure to AD, chronic medical conditions, functional disability, length of stay in the U.S., and acculturation.

* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001

Discussion

Responding to the growing imperative to address cognitive health and AD-related issues in older ethnic minorities (Alzheimer’s Association, 2019; Casado et al., 2017; Jang et al., 2010, 2018; Sun et al., 2013), the present study examined the associations between immigration-related factors, cognitive performance, self-rated cognitive status, and concern about AD among older Korean Americans. Based on the HBM and SHBM (Rosenstock, 1974; Sayegh & Knight, 2013) and literature on heath assessment (e.g., Jang et al., 2009; Kahana et al., 1995), we hypothesized that (1) AD concern would be associated with immigration-related factors and (2) self-rated cognitive status would serve as a mediator in the relationship between cognitive performance and concern about AD. Our analyses found supportive evidence for the both of our proposed hypotheses.

Over half (52.1%) of the sample of older Korean Americans reported that they were either somewhat or very much concerned that they might develop AD someday. This rate is considerably higher than the 30.2% observed in the U.S. national sample of adults aged 50 or older in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS; Cutler, 2015). It is also higher than the 13% of adults aged 18 years or over expressing concern in a national online survey (Tang et al., 2017) and the 18% of Asian Americans aged 18 years or over in the Asian American Quality of Life Survey (Jang et al., 2018). Given the differences in age range and measures employed across several studies, comparative findings should be interpreted with caution. On the other hand, the proportion (33.2%) rating their overall cognitive status as either fair or poor was quite similar to the 27.1% observed in the HRS (Cutler, 2015).

Both objective and subjective measures of cognitive status were positively associated with personal resources (e.g., higher cognitive status was associated with higher socioeconomic status and physical health). It is notable that prior exposure to AD was significantly linked with AD concern in both bivariate and multivariate models. As shown in other studies (e.g., Cutler, 2015; Jang et al., 2018), individuals tend to respond to the personal experience of having a family member or friend affected by AD with more worries and concerns about developing AD themselves.

With regard to immigration-related factors, AD concern was significantly associated with acculturation but not with the length of residence in the U.S. One explanation for this finding is that length of stay is less likely to capture the extent to which an older immigrant adapts to the host culture (Miglietta & Tartaglia, 2009). In contrast, our measure of acculturation covered multi-dimensional aspects of cultural adaption. As suggested in previous research (Lee et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2013), successful adaption to mainstream society may facilitate acquisition of accurate knowledge and a more positive attitude toward AD.

As anticipated, cognitive performance measured by the MMSE and self-rated cognitive status showed a significant but modest correlation (r = .25, p < .001). This finding is in accordance with other studies demonstrating low to moderate associations between objective and subjective measures of cognitive function (Jungwirth et al., 2004; Mulligan, Smart, Segalowitz, & MacDonald, 2018), which suggests the different nature and function of objective and subjective measures. By considering both objective and subjective measures of cognitive status as contributing factors to AD concern, the present study showed that the predictability of objective cognitive performance was comparatively lower than that of self-rated cognitive status.

Results confirmed the mediating role of self-rated cognitive status in the relationship between cognitive performance and AD concern. Consistent with the HBM and SHBM (Rosenstock, 1974; Sayegh & Knight, 2013), as applied to AD-related issues (e.g., Jang et al., 2018; Kessler et al., 2012), perceived threat (i.e., AD concern) of the condition was influenced by subjective appraisals of the risk (i.e., self-rated cognitive status), which mediated the effect of the potential risk (i.e., cognitive performance on MMSE). In other words, the presence of cognitive decline primes older individuals to harbor negative perceptions of their own cognitive status, which leads to higher AD concern. The mediation model not only helps us better understand the psychological mechanisms by which AD concern is linked with objective and subjective measures of cognitive status, but also suggests perceived cognitive status as an avenue for interventions. If early cognitive impairment is accurately translated into legitimate concerns, it may function as a prompt to seek professional help. The overall findings not only call attention to the importance of promoting accurate assessments of, and positive attitudes toward, personal cognitive health in older adults but also help guide efforts to address public concerns about AD and promote communication strategies.

Some limitations to the present study should be recognized. Given its cross-sectional design and the non-probability sampling strategies, we cannot generalize the findings to the national level or draw causal inferences. It should also be noted that the present study focused on community-dwelling and cognitively intact older adults. Given the nature of the sample, the findings are only suggestive and await further investigation. Future studies should also include more representative samples, diverse racial/ethnic groups, other sources of cognitive assessment (e.g., informant report and neurological testing), and longitudinal follow-ups to advance the scope of the assessment. A wider range of confounding variables (e.g., knowledge about AD treatment, genetic susceptibility, and self-efficacy) should also be considered in the model. Furthermore, the advantages and disadvantages of the use of a single self-report item on subjective cognitive status and AD concern warrant further investigation.

Despite the limitations, the present study contributes to the literature on cognitive health and AD-related concerns in older ethnic minorities. Building upon the HBM and SHBM, this study highlights the significance of both subjective cognitive status and acculturation in shaping older adults’ concerns about AD. Our findings suggest that cognitive performance might not be directly translated into fear of developing AD. Rather, subjective appraisals of such impairment are imperative to connect objective cognitive performance with AD concern.

Finally, the brief cognitive measures employed in the study have potential value as a screening tool for older adults in primary care and community health settings, enabling health professionals to help older clients develop a more accurate assessment of their own cognitive health status. In addition, education and training that addresses older adults’ potential concerns about AD and available AD-related resources may help them to properly respond not only to signs of cognitive decline but also to AD-related concerns and anxieties. Our findings also suggest that the programs and services need to address cultural misconceptions or stigmas about AD and prioritize older immigrants who are not familiar with the U.S. culture and healthcare systems.

Acknowledgment:

Data collection was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (R01AG047106, PI: Yuri Jang, Ph.D.). The authors thank Drs. Kunsook Bernstein, Soonhee Roh, Soyeon Cho, Sanggon Nam, and Seunghye Hong and community advisors for help with data collection. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2019). Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Retrieved from https://www.alz.org/media/Documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures-2019-r.pdf

- Bruce JM, Bhalla R, Westervelt HJ, Davis J, Williams V, & Tremont G (2008). Neuropsychological correlates of self-reported depression and self-reported cognition among patients with mild cognitive impairment. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 21(1), 34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casado BL, Hong M, & Lee SE (2017). Attitudes toward Alzheimer’s care-seeking among Korean Americans: Effects of knowledge, stigma, and subjective norm. The Gerontologist, 58(2), e25–e34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler SJ (2015). Worries about getting Alzheimer’s: Who’s concerned?. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias®, 30(6), 591–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler SJ, & Hodgson LG (1996). Anticipatory dementia: A link between memory appraisals and concerns about developing Alzheimer’s disease. The Gerontologist, 36(5), 657–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fastame MC, & Penna MP (2014). Psychological well-being and metacognition in the fourth age: An explorative study in an Italian oldest old sample. Aging & Mental Health, 18(5), 648–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillenbaum G (1988). Multidimensional functional assessment: The Duke older Americans resources and services procedure. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, & McHugh PR (1975). Mini-mental state. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatry Research, 12(3),189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flavell JH (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive– developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906–911. [Google Scholar]

- Interactive Harris. (2011). What America thinks: MetLife Foundation Alzheimer’s survey. Retrieved from https://www.metlife.com/content/dam/microsites/about/corporate-profile/alzheimers-2011.pdf

- Hayes AF (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76(4), 408–420. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- James BD, & Bennett DA (2019). Causes and patterns of dementia: An update in the era of redefining Alzheimer’s disease. Annual Review of Public Health, 40, 65–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang Y, Chiriboga DA, Borenstein A, Small BJ, & Mortimer JA (2009). Health-related quality of life in community-dwelling older Whites and African Americans. Journal of Aging and Health, 21(2), 336–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang Y, Kim G, & Chiriboga DA (2010). Knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease, feelings of shame, and awareness of services among Korean American elders. Journal of Aging and Health, 22(4), 419–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang Y, Kim G, Chiriboga DA, & King-Kallimanis B (2007). A bidimensional model of acculturation for Korean American older adults. Journal of Aging Studies, 21(3), 267–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang Y, Yoon H, Park NS, Rhee MK, & Chiriboga DA (2018). Asian Americans’ concerns and plans about Alzheimer’s disease: The role of exposure, literacy and cultural beliefs. Health & Social Care in the Community, 26(2), 199–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang Y, Choi E, Rhee MK, Park NS, Chiriboga DA, Kim MT (2019). Determinants of self-rated cognitive health in older Korean Americans. The Gerontologist. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CL, Jensen JD, Scherr CL, Brown NR, Christy K, & Weaver J (2015). The Health Belief Model as an explanatory framework in communication research: Exploring parallel, serial, and moderated mediation. Health Communication, 30 (6), 566–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungwirth S, Fischer P, Weissgram S, Kirchmeyr W, Bauer P, & Tragl KH (2004). Subjective memory complaints and objective memory impairment in the Vienna‐ Transdanube aging community. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 52(2), 263–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahana E, Resmond C, Hill G, Kercher K, Kahana B, Johnson J, et al. (1995). The effects of stress, vulnerability, and appraisal on the psychological well-being of the elderly. Research on Aging, 17(4), 459–489. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler EM, Bowen CE, Baer M, Froelich L, & Wahl HW (2012). Dementia worry: A psychological examination of an unexplored phenomenon. European Journal of Ageing, 9(4), 275–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TH, Jhoo JH, Park JH, Kim JL, Ryu SH, Moon SW, … & Lee SB (2010). Korean version of mini mental status examination for dementia screening and its’ short form. Psychiatry Investigation, 7(2), 102–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Lai JS, Wagner LI, Jacobsen PB, & Cella D (2014). Self‐reported cognitive concerns and abilities: Two sides of one coin?. Psycho‐Oncology, 23(10), 1133–1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SE, Lee HY, & Diwan S (2010). What do Korean American immigrants know about Alzheimer’s disease (AD)? The impact of acculturation and exposure to the disease on AD knowledge. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(1), 66–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miglietta A, & Tartaglia S (2009). The influence of length of stay, linguistic competence, and media exposure in immigrants’ adaptation. Cross-Cultural Research, 43(1), 46–61. [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan BP, Smart CM, Segalowitz SJ, & MacDonald SW (2018). Characteristics of healthy older adults that influence self-rated cognitive function. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 24(1), 57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman AL, Woodard JL, Calamari JE, Gross EZ, Pontarelli N, Socha J, … & Armstrong K (2018). The fear of Alzheimer’s disease: mediating effects of anxiety on subjective memory complaints. Aging & Mental Health, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock IM (1974). Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Education Monographs, 2(4), 328–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayegh P & Knight BG (2013). Cross-cultural differences in dementia: The sociocultural health belief model. International Psychogeriatrics, 25(4), 517–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suhr JA, & Kinkela JH (2007). Perceived threat of Alzheimer disease (AD): The role of personal experience with AD. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders, 21(3), 225–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun F, Gao X, & Coon DW (2013). Perceived threat of Alzheimer’s disease among Chinese American older adults: The role of Alzheimer’s disease literacy. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70(2), 245–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W, Kannaley K, Friedman DB, Edwards VJ, Wilcox S, Levkoff SE, … & Belza B (2017). Concern about developing Alzheimer’s disease or dementia and intention to be screened: An analysis of national survey data. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 71, 43–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). American Fact Finder 2010. Retrieved from http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=DEC_10_SF1_PCT5&prodType=table. [Google Scholar]

- Werner P, & Davidson M (2004). Emotional reactions of lay persons to someone with Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 19(4), 391–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]